- 1Department of Business Administration, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

- 2KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

- 3BI Norwegian Business School, Oslo, Norway

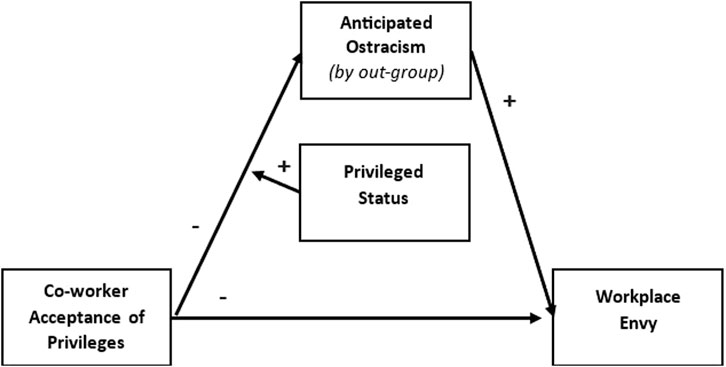

In many workplaces, managers provide some employees with unique privileges that support their professional development and stimulate productivity and creativity. Yet with some employees more deserving of a privileged status than others, co-workers feeling left out of the inner circle may begin to exhibit feelings of envy. With workplace envy and intergroup conflicts going hand in hand, the question arises whether co-worker acceptance of employee privileges—where conflict can be constrained through an affirmative re-evaluation of co-workers’ privileged status—may lower the envy experienced by employees. Using virtual reality technology, 112 employees participated in a virtual employee meeting at a virtual organization where they were exposed to a new workforce differentiation practice. We show through our experiment that co-worker acceptance of employee privileges negatively influences workplace envy, which was partially mediated by the anticipated ostracism of employees. Moreover, we show that this effect is only found for employees with privileges, who worry more about being ostracized than their non-privileged co-workers. We anticipate that our findings will enable managers to conscientiously differentiate between their employees, using virtual reality simulations to steer employees’ thoughts and feelings in a direction that benefits both employees and organizations.

Introduction

Envy is a common occurrence in the workplace and is linked to a plethora of negative outcomes (Greenberg et al., 2007), both for organizations and their workers. Envy relates to diminished productivity and employee wellbeing (Reh et al., 2018), increased counter-productive work behavior (Cohen-Charash and Mueller, 2007), as well as employee absenteeism and turnover (Tussing et al., 2022). While it is arguably better to be envied than to envy (Exline and Lobel, 1999), those that are envied by their co-workers may also find it to be a disconcerting experience (Vecchio, 2005). Yet despite managers best attempts to limit envy in the workplace (Bedeian, 1995; Dogan and Vecchio, 2001), many of their organizational practices that favor some employees over others inevitably seem to go hand in hand with employee envy (Duffy et al., 2008).

When organizations commit to differentiate between their employees, they are essentially creating two opposing groups within the organization (Nijs et al., 2022)–the “haves” versus the “have-nots”. These differentiations can range from a wide number of (in)tangible benefits and privileges granted to employees such as promotions, bonuses, salary increases, praise (Schaubroeck and Lam, 2004), recognition (e.g., employees given a “high-potential”, “talent” or “star” label; Nijs et al., 2022), or even just additional time off from work (Marescaux et al., 2021). The privileged status that some employees enjoy has not only been linked with envy (Veiga et al., 2014), but also with workplace ostracism (Robinson et al., 2013)—which occurs when a group of employees are being socially excluded by another group (Williams, 2007).

Employees who feel ostracized at work are said to suffer worse outcomes than those who face other intergroup conflicts such as harassment (O’Reilly et al., 2015) or bullying (Ferris et al., 2008), particularly because ostracism in the workplace is exceptionally difficult to solve (Robinson et al., 2013), and the experience has been linked with physical pain (Eisenberger et al., 2003). While workplace ostracism has on occasion been considered a mediator to employee envy (Breidenthal et al., 2020) and being envied (Liu et al., 2019), the anticipation of being ostracized may as well predict workplace envy. That is because ostracism is also characterized by a form of social anxiety (Buss, 1990), causing individuals to worry about how their perceived relative status will influence their social interactions with peers (O’Donnell et al., 2019).

In the present context, employees who are concerned about how their privileged status—e.g., their newfound publicized recognition by their manager—could affect their standing with their co-workers, may anticipate being ostracized by those without the same privileged status and interpret this as an expression of envy. Conversely, under-privileged employees may anticipate being socially excluded from the “inner circle” by their privileged co-workers and begin to envy them for their newfound status. Thus, workplace envy is often rooted in a sense of belonging–or not belonging–to a group at work, and the anticipation of ostracism is therefore likely to enhance feelings of envy.

Given that social inclusion is a basic human need (Baumeister and Leary, 1995) and that managers will continue to differentiate between their employees, the question becomes what steps they can undertake so that those with an under-privileged status do not become envious of their privileged co-workers, and vice versa. Researchers have established that a positive and cooperative environment will reduce intergroup conflict and envy in the workplace (Wu et al., 2016), while simultaneously emphasizing the similarities between both groups (Krueger and DiDonato, 2008) such that privileged co-workers can be perceived as role-models by those “below” them (Lockwood and Kunda, 1997). Other studies have similarly found that a competitive environment—where employees are fighting over individual privileges—will bolster workplace envy (Bedeian, 1995; Murtza and Rasheed, 2022).

In the present study we expand the understanding of workplace envy by suggesting that the majority group—typically those without special privileges (Bonneton et al., 2020)—is less likely to feel ostracized as they can rely on each other for social acceptance (Nadler et al., 2008) to fulfill their need to belong (Baumeister and Leary, 1995). Following that logic, the privileged employees benefit most from their co-workers’ acceptance of their privileges—where they are being acknowledged as valued members of the organization by their co-workers—thereby limiting the extent to which they anticipate being ostracized and their subsequent feelings of being envied. We propose a theoretical model—see Figure 1—in which workplace envy is predicted by whether employees accept that a select few co-workers receive privileges, mediated by employees’ anticipated ostracism by out-group co-workers. Furthermore, this relationship will be moderated by the privileged status given to employees by management, such that only those employees with a privileged status anticipate to be ostracized by their non-privileged co-workers.

For this study we employ virtual reality (VR) technology so that we can recreate a life-like organizational setting to study employee reactions in, without having to actually randomly distribute privileges to employees which may raise ethical concerns (e.g., researchers may not deceitfully provide employees with a promotion). While wearing a head-mounted display (HMD) the employees participating in the experiment are fully engrossed within the virtual environment as the most important human senses—sight and hearing—are stimulated exclusively by the VR experience (Slater and Usoh, 1993). It is then expected that the participant will respond to events happening during the VR experience in a more naturalistic manner, resembling behavior and feelings that are akin to how they would be in the real world (Aguinis and Bradley, 2014). Participants also typically embody a body or “avatar” during the VR experience, adding to the belief that they are present within the virtual environment (Slater, 2009).

Methods

Experimental design

A 2 × 2 between-groups experimental design was employed using immersive 360-degree VR videos. The scenes were recorded at a boardroom of our local university campus, with university staff with acting experience playing out the individual roles of employees (see Supplementary Figure S1 for the full script). The 360-camera was positioned on top of an inanimate body, providing participants the illusion that they embodied a person present at the meeting. We manipulated whether the participant was given a privileged status within the virtual organization (i.e., as a so-called ‘high-potential’ employee), providing them with access to professional development resources that were not available to all employees, which we refer to as ‘privileged’ and ‘under-privileged’. Furthermore, we manipulated the co-worker acceptance of employee privileges within the organization, labelled as ‘accepted’ and ‘unaccepted’. In the accepted condition the privileged employees were acknowledged by their virtual co-workers and admired as role models, whereas in the unaccepted condition these same employees were not regarded as valued and contributing members of the organization—thereby signaling ostracism (Spoor and Williams, 2007). Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four groups.

Participants

112 employees (full or part-time employed) working in Belgium participated in our study and were included in our analyses. The average participant was 35.4 years old (SD = 11.4), and precisely half were male. The largest groups of participants were employed in the telecom industry (17.9%), human resources (13.4%), and education (13.4%). 22 participants (19.6%) held a management position within their organization, whereas 76 participants (67.9%) were white-collar workers. Of the original sample of 117, three participants were removed from our final sample due to malfunctioning VR equipment, and two for failing a manipulation check.

The VR study was approved by the Social and Societal Ethics Committee of the KU Leuven (G-2020-2513) and carried out in accordance with ethical and preventive COVID-19 procedures. Participants gave written and informed consent.

Materials

The VR headset used by participants was a Meta Quest 2 HMD that displays a 3D scene in stereo with a field of view of 110°. Each individual display per eye has a resolution of 1,832 × 1,920. Participants also wore noise-cancelling headphones to prevent outside noises from disturbing and distracting the participants from the VR experience. The VR experience was prepared for each participant, and the physical area mapped, by the researchers and their assistants so that participants only had to put on the equipment to begin the study.

Procedure

Employees were recruited to participate in the VR study through both purposive and convenience sampling. First, flyers were handed out at VR events and professional workshops in the vicinity of the university and invited employees to visit the university’s research lab for the study. Second, employees were contacted through our social networks to invite them to our lab or to visit them on location—at their organization if possible—for the study. Third, private rooms or offices were provided by organizations allowing their employees to participate in the study if they wanted to. The VR experience did not require the headset to be tethered to a computer, allowing for more flexibility in the location of data collection outside of the university’s lab. We demanded, however, that the location for data collection was quiet and private so that employees would not get distracted or feel observed by their co-workers. A VR headset of the same make was raffled off to participants to incentivize participation.

Before putting on the VR headset and headphones, participants were informed that they would temporarily join a virtual organization and partake in one of their employee meetings. When participants donned the headset they would find themselves embodied as a virtual employee named Robin. A gender-neutral name was specifically chosen to prevent gender limiting participants’ immersion. The VR experience began with a brief embodiment phase of 30 s to allow participants to acclimatize to their new virtual surrounding and body, as well as the headset itself. Following this phase, four events were presented to participants. First, participants were informed of the organizations’ background and its plans to differentiate between its workforce. Second, participants learned whether Robin—i.e., they themselves—would stand to benefit from the differentiation practices introduced, along with some of the other virtual co-workers. Third, participants were exposed to either a situation with a notable lack of acceptance of employee privileges—where co-workers rejected the privileges some employees received—or a situation with ample acceptance of employee privileges—characterized by admiration and respect for the employees with a privileged status. Finally, participants were given the opportunity to provide ‘feedback’ to their virtual HR manager about what they just experienced, thereby initiating the data collection process. Participants spent roughly 7 min in total in the VR simulation. Participants were debriefed once the data collection was complete, and the headset was removed.

Response variables

This study utilized two instruments to measure participants’ responses (first, anticipated ostracism, and later, envy), as detailed below; we also collected demographic information as well as information pertaining to participants’ more technical experience while in the VR simulation. For VR studies like ours, it is imperative that participants do not suffer from cybersickness and are adequately immersed in the VR experience—characterized by a strong sense of presence, realism, and embodiment--to guarantee the study’s external and ecological validity (Aguinis and Bradley, 2014).

Immersion. The first and foremost reason to conduct VR research is to enhance the realism of the experience presented to employees as well as their levels of immersion—with VR providing considerably greater benefits than traditional text-based vignette studies (Aguinis and Bradley, 2014). Immersion is a loosely defined construct in the literature however, often used intermittently with—or as a phenomenon encompassing—presence, experienced realism, embodiment, and agency. To measure participants’ levels of immersion as broadly as possible we used the Slater-Usoh-Steed presence questionnaire (Slater and Usoh, 1993) and general items that have been frequently used the last few decades to measure participants’ experienced realism and embodiment during VR studies (Witmer and Singer, 1994; Schubert, 2003) (α = .84). We list the specific items used, and their factor loadings, in the online Supplementary Table S1.

Workplace envy. Participants’ feelings of envy towards privileged co-workers (in the under-privileged condition), or feelings of being envied by under-privileged co-workers (in the privileged condition), were measured using the scales developed by Vecchio (2005) (α = .82). Participants responded to these items on a scale from 1 = very unlikely to 5 = very likely.

Anticipated ostracism. We asked participants to what extent they expected to be continuously ostracized by their co-workers if they kept working at the fictional organization using the Workplace Ostracism Scale (O’Reilly et al., 2015) (α = .94). Participants responded to these items on a scale from 1 = never to 7 = all the time. The individual items for both scales can be found in the online Supplementary Table S2.

Statistical methods

Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 28, and the moderated mediation model tested using the PROCESS macro, model 7 (Hayes, 2017). Indirect effects were tested using bias-corrected bootstrapping (n = 5000) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Participants’ level of immersion was controlled for in our model, as those who were more strongly engaged with the VR simulation may have reacted more strongly to the events they were exposed to within and adjusted their responses accordingly (Aguinis and Bradley, 2014; Slater, 2009; Adão et al., 2018). In addition, we controlled for age and gender as studies have shown that older employees and women may experience envy differently due to differing thoughts about their career (Festing and Schäfer, 2014; Zhang, 2020). The outcomes of the below analyses do not significantly differ if the control variables were to be excluded from the model.

We found no indication of common method bias using Harman’s single factor score as the average variance extracted was 34.94%, well below the 50% cut-off point (Kock, 2020).

Results

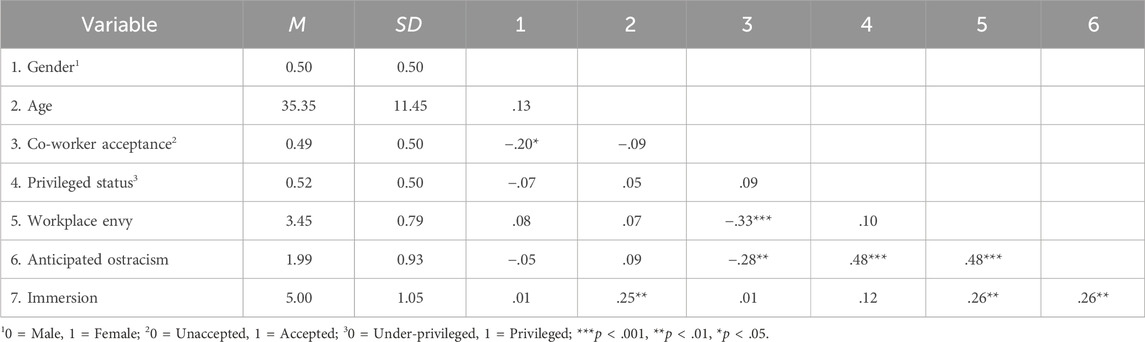

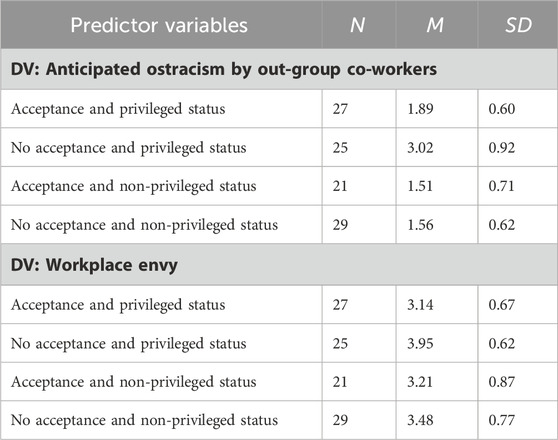

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for all variables can be found in Table 1, with the means and standard deviations for all experimental conditions summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Two-way ANOVA means comparisons of the anticipated ostracism by out-group co-workers and workplace envy for each experimental condition (co-worker acceptance of privileges and privileged status).

User experience with the virtual environment

For the experiment to be a success it was necessary that employees were able to adequately immerse themselves in the role of Robin as an employee of a fictional organization, rather than feel like an objective observer that was not actively participating as a member of said organization. Supplementary Table S1 shows that there was overall little incidence of cybersickness and that participants perceived the organizational setting as realistic, while being fully comfortable stepping into the shoes of Robin. Moreover, we found that were no significant differences in participants’ experience of immersion between the four experimental conditions (F (3, 108) = 0.71, p = .546).

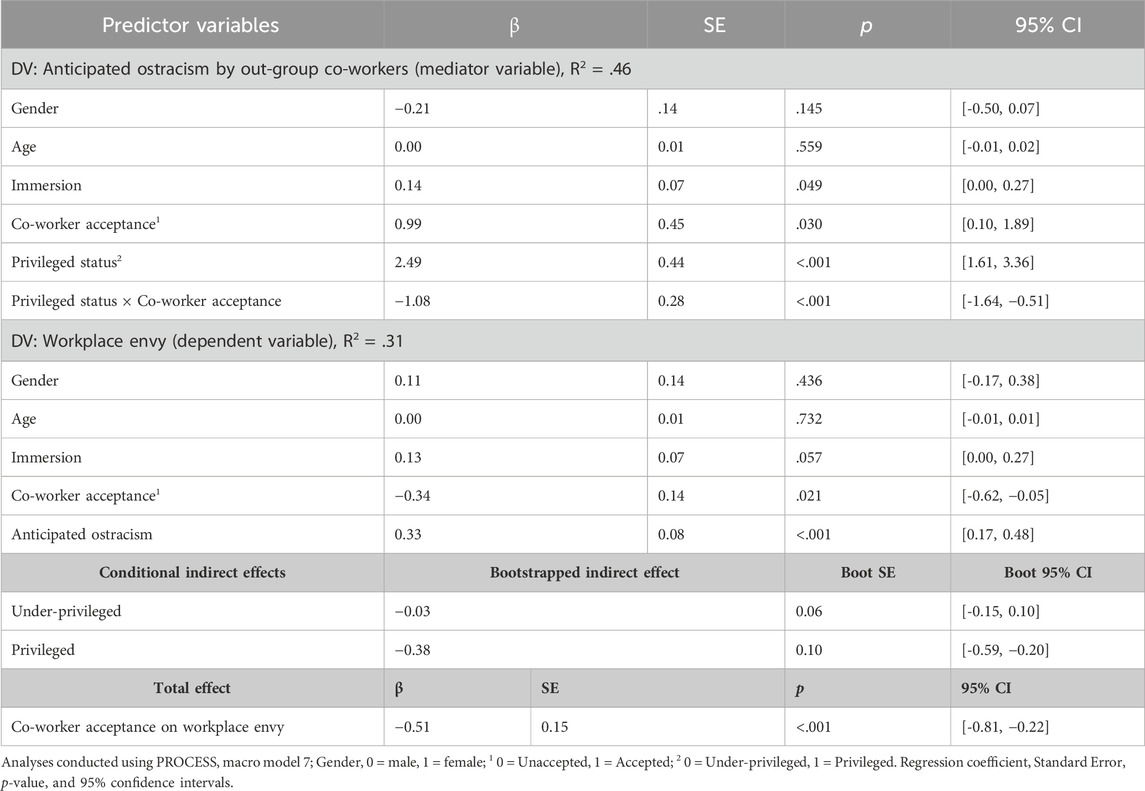

The immersion experienced by participants significantly influenced our theoretical model. Those that felt that they were more present within the virtual organization, perceived it to be realistic, and adequately took on Robin’s role, were more likely to anticipate being ostracized (β = 0.14, SE = 0.07, p = .049). Their immersion did not predict their feelings of envy or being envied however (β = 0.13, SE = 0.07, p = .057).

Employee experience of envy and ostracism in the workplace

The outcomes for the moderated mediation model of our 2 × 2 experimental design are summarized in Table 3. First of all, we found a significant effect of co-worker acceptance (F (1,98) = 16.95, p < .001) and privileged status (F (1,98) = 40.95, p < .001) on anticipated ostracism. Significant effects were also found of co-worker acceptance (F (1,98) = 13.48, p < .001) on workplace envy, but—as expected—not for privileged status (F (1,98) = 1.83, p = .179). For our hypothesized model, the results show a strong total effect of co-worker acceptance of employee privileges on envy in the workplace (β = −0.51, SE = 0.15, p < .001). Participants in the accepted condition were less likely to feel envy or envied (M = 3.17, SD = 0.76), than those in the unaccepted condition (M = 3.69, SD = 0.74). The acceptance of employee privileges also directly influenced the anticipated ostracism of participants (β = 0.99, SE = 0.45, p = .030), and anticipated ostracism related to envy in the workplace (β = 0.33, SE = 0.08, p < .001). Overall, participants in the accepted condition expected to be ostracized less (M = 2.24, SD = 1.06) than those in the unaccepted condition (M = 1.72, SD = 0.67), increasing their likelihood to feel envy or envied. We found that anticipated ostracism partially mediated the relationship between co-worker acceptance of employee privileges and workplace envy (indirect effect = −0.18, Boot SE = 0.07, Boot 95% CI = [-0.32, −0.06]), thereby supporting our hypothesized theoretical model.

Table 3. Testing the moderated mediation effect of co-worker acceptance of employee privileges on workplace envy through anticipated ostracism, moderated by employees’ privileged status.

Moderating role of privileged status

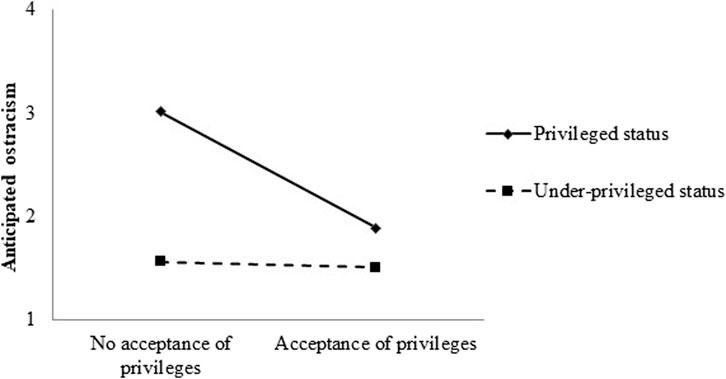

We found, in line with our expectations, that the privileged status to employees significantly predicts their anticipated ostracism (β = 2.49, SE = 0.44, p < .001), and moderates the relationship between co-worker acceptance of employee privileges and anticipated ostracism (β = −1.08, SE = 0.28, p < .001). The privileged status also moderated the mediation (Index = −0.35, Boot SE = 0.11, Boot 95% CI = [-0.60, −0.16]. More concretely, we found that there was no indirect effect on workplace envy through anticipated ostracism in the under-privileged condition (indirect effect = −0.03, Boot SE = 0.06, Boot 95% CI = [-0.15, 0.10]), while there was in the privileged condition (indirect effect = −0.38, Boot SE = 0.10, Boot 95% CI = [-0.59, −0.20]). As is shown in Figure 2, participants in the privileged condition tend to anticipate being more ostracized when there is no co-worker acceptance (M = 3.02, SD = 0.92), than when there is co-worker acceptance (M = 1.89, SD = 0.60), leading them to feel more envied as a result.

Figure 2. Anticipated ostracism as a function of co-worker acceptance of employee privileges and privileged status of employees (means plot).

Discussion

The present study measured the psychology of employee behaviors and feelings (i.e., no student sample) in a virtual yet life-like organizational setting using VR technology. Based on our measurements of general user experience, we can conclude that employees are capable to immerse themselves into the role of another employee at a (fictional) virtual organization, based on their high scores on perceived realness, presence, and embodiment.

The findings generally support our theoretical model (Figure 1). We found that a lack of co-worker acceptance of employee privileges—where the privileges of some employees were not acknowledged by their co-workers—contributes to workplace envy, which was partially mediated by employees’ anticipation of being ostracized by their co-workers. This effect is only apparent for the employees with privileges who anticipate considerably more ostracism when they are not valued by their co-workers—while the same cannot be said for those without privileges. This can be explained by the fact that the employees without privileges comprise a majority group, leading to an estimate that the total social impact of being ostracized by them would be relatively minor in comparison to the extent of social acceptance they can receive from their co-workers who also lack privileges (Nadler et al., 2008).

The results show a partially mediated relationship of anticipated ostracism between co-worker acceptance of employee privileges and workplace envy. This means that efforts to address employees’ anticipated ostracism—such as effectuating co-worker acceptance of employee privileges by instilling a positive work climate and collaborative atmosphere (Wu et al., 2016)—helps to reduce workplace envy, yet additional measures need to be undertaken if managers want to further eliminate envy on the work floor. Further steps, for instance, may include altering the publicization of privileges to employees, as well as modifying the nature and contents of the privileges granted to employees (Tussing et al., 2022).

Implications

The findings of this study present useful implications for both managers and the academic community. Beginning with the former, while some previous studies have demonstrated their applicability in addressing the emotional wellbeing of individuals from various walks of life such as those with disabilities (Mills et al., 2023), senior citizens (Lee et al., 2019), and the chronically ill (Chirico et al., 2016), the present study provides managers with a potential tool to address employees’ emotional wellbeing in the face of intergroup conflicts at work. With VR applications and simulations being exceptionally well suited to induce highly specific emotions amongst users (Somarathna et al., 2022), these VR experiences may be just what managers could use to elicit beneficial emotions for workers—e.g., interest, enthusiasm, inspiration, admiration, hope, optimism (Smith, 2000)—and to inhibit the drawbacks associated with workforce differentiation practices (Marescaux et al., 2021). While this kind of exposure therapy is notably niche in the field of employee psychology (cf. clinical VR research started well over 2 decades ago; Rothbaum et al., 1997), a recent study (Leung and Huang, 2023) from 2023 showed that daily VR interventions were able to alleviate employee emotional functioning greatly in work environments lacking in social support. Thus, by exposing employees first to the differentiation practice virtually, managers could steer the general dispositions employees hold of co-workers with a privileged status, regardless of whether they stand to benefit themselves or not.

Through this study we also demonstrate to scholars that hyper-realistic VR experiences can effectively be used to enhance the generalizability of measured employee behaviors (Aguinis and Bradley, 2014), with greater effect sizes the more immersed participants are within the VR experience. Moreover, we show that a privileged status can be linked to negative anticipatory employee behaviors—supplementing the state-of-the-art literature on social comparisons at the workplace (Greenberg et al., 2007; Reh et al., 2018). Few studies have investigated the impact workforce differentiation has on those excluded (Bonneton et al., 2020), with most studies focusing instead on the behavior-enhancing effects of privileges or the strategic advantages taken for granted by organizations (Huselid and Becker, 2011).

Limitations

A common critique of experimental studies in employee psychology is their lack of ecological validity, with critics questioning the replicability of study findings within organizations. Nevertheless, experimental VR studies allow us to surpass the limitations of traditional vignette studies by providing participants with an experience that is not perceivably different from the real world (Aguinis and Bradley, 2014). Indeed, in our study, 102 (91%) of participants reported at the end that they would prefer to participate in a VR study again in the future, whereas only 6 (5%) would prefer to watch a video recording on their desktop and 1 (1%) would rather read a traditional text-based vignette—which is presently the ubiquitous norm in experimental employee psychology (Aguinis and Bradley, 2014).

Regardless of the type of methodology used however, the variables measured reflect intentional behaviors to the scenario presented by researchers. Participants indicated that they would feel envious of their co-workers if the scenario happened to them in reality, and these intentions are a strong predictor of actual behavior (Dalton et al., 1999). Employees were able to feel or act a certain way during our study without it having repercussions for their position within their organization, their relationship with co-workers, or their career success. By comparison, field studies within organizations demand researchers to take into account a plethora of confounds (e.g., organizational culture, supervisor relationship, employee commitment; Martinko et al., 2014), making it difficult to make valid conclusions without access to big data. Moreover, in the context of privileges it would be cumbersome as employees are not always privy to the knowledge which privileges are granted uniquely to them and are not available to their co-workers (Sumelius et al., 2020).

Future directions

We encourage scholars to continue research into workplace envy, particularly using customized research designs that nuance our current findings. Future investigations may, for instance, utilize interactive VR simulations that give participants agency to actively engage and react to their virtual co-workers’ actions in real time. Such an approach not only enhances the immersive experience further, it also allows researchers to readily manipulate the organizational environment and its people, allowing them to assess the generalizability of study findings to different organizational settings (Hubbard and Aguinis, 2023).

Alternative research designs that study the role of organizational context may also yield valuable insights on workplace ostracism. Prior research has established that cooperative tasks and frequent employee interactions (Wu et al., 2016), as well as an inclusive work climate (Nikandrou and Tsachouridi, 2015), may limit employee ostracism. While a traditional field study on this topic would introduce several confounds—differences between organizations that may affect employee reactions (e.g., firm size, sector, leader-follower relationships)—a systematic approach where these contextual and individual differences are controlled for in a series of experiments will enable a more thorough understanding of the studied workplace dynamics.

Finally, given the dearth of VR studies in industrial and organizational psychology and in management research more broadly, we hope that the present research inspires more scholars concerned with employee behaviors and feelings to adopt VR technology for their investigations. Particularly with sensitive topics, such as intergroup conflicts, the present study demonstrates a way to reliably manipulate relevant constructs without relying on a laboratory setting or field experiment—provided that the VR study puts sufficient emphasis on the socio-emotional elements required to convey these organizational phenomena to employees (Williams, 2007).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Social and Societal Ethics Committee of the KU Leuven. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AvZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. ND: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing–review and editing. JM: Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by an Aspirant fellowship grant (1113919N) and a project grant (G074418N) from the FWO-Research Foundation Flanders, and by an Internal Funds C1 grant from the KU Leuven (C14/17/014).

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Dr. Diana Sanchez for her support in developing the VR experience and Simon Heleven, Anouk Leen, and Sofie Cerstelotte for their assistance at the VR laboratory.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frvir.2024.1260910/full#supplementary-material

References

Adão, T., Pádua, L., Fonseca, M., Agrellos, L., Sousa, J. J., Magalhães, L., et al. (2018). A rapid prototyping tool to produce 360° video-based immersive experiences enhanced with virtual/multimedia elements. Procedia Comput. Sci. 138, 441–453. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2018.10.062

Aguinis, H., and Bradley, K. J. (2014). Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organ. Res. Methods 17 (4), 351–371. doi:10.1177/1094428114547952

Baumeister, R. F., and Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117 (3), 497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Bonneton, D., Festing, M., and Muratbekova-Touron, M. (2020). Exclusive talent management: unveiling the mechanisms of the construction of an elite community. Eur. Manag. Rev. 17 (4), 993–1013. doi:10.1111/emre.12413

Breidenthal, A. P., Liu, D., Bai, Y., and Mao, Y. (2020). The dark side of creativity: coworker envy and ostracism as a response to employee creativity. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 161, 242–254. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.08.001

Buss, D. M. (1990). The evolution of anxiety and social exclusion. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 9 (2), 196–201. doi:10.1521/jscp.1990.9.2.196

Chirico, A., Lucidi, F., De Laurentiis, M., Milanese, C., Napoli, A., and Giordano, A. (2016). Virtual reality in health system: beyond entertainment. a mini-review on the efficacy of VR during cancer treatment. J. Cell. Physiology 231 (2), 275–287. doi:10.1002/jcp.25117

Cohen-Charash, Y., and Mueller, J. S. (2007). Does perceived unfairness exacerbate or mitigate interpersonal counterproductive work behaviors related to envy? J. Appl. Psychol. 92 (3), 666–680. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.666

Dalton, D. R., Johnson, J. L., and Daily, C. M. (1999). On the use of" intent to." variables in organizational research: an empirical and cautionary assessment. Hum. Relat. 52 (10), 1337–1350. doi:10.1177/001872679905201006

Dogan, K., and Vecchio, R. P. (2001). Managing envy and jealousy in the workplace. Compens. Benefits Rev. 33 (2), 57–64. doi:10.1177/08863680122098298

Duffy, M. K., Shaw, J. D., and Schaubroeck, J. M. (2008). Envy in organizational life. Envy Theory Res. 2, 167–189.

Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., and Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science 302 (5643), 290–292. doi:10.1126/science.1089134

Exline, J. J., and Lobel, M. (1999). The perils of outperformance: sensitivity about being the target of a threatening upward comparison. Psychol. Bull. 125 (3), 307–337. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.125.3.307

Ferris, D. L., Brown, D. J., Berry, J. W., and Lian, H. (2008). The development and validation of the workplace ostracism scale. J. Appl. Psychol. 93 (6), 1348–1366. doi:10.1037/a0012743

Festing, M., and Schäfer, L. (2014). Generational challenges to talent management: a framework for talent retention based on the psychological-contract perspective. J. World Bus. 49 (2), 262–271. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2013.11.010

Greenberg, J., Ashton-James, C. E., and Ashkanasy, N. M. (2007). Social comparison processes in organizations. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 102 (1), 22–41. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.006

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Hubbard, T. D., and Aguinis, H. (2023). Conducting phenomenon-driven research using virtual reality and the metaverse. Acad. Manag. Discov. 9 (3), 408–415. doi:10.5465/amd.2023.0031

Huselid, M. A., and Becker, B. E. (2011). Bridging micro and macro domains: workforce differentiation and strategic human resource management. J. Manag. 37 (2), 421–428. doi:10.1177/0149206310373400

Kock, N. (2020). Harman’s single factor test in PLS-SEM: checking for common method bias. Data Analysis Perspect. J. 2 (2), 1–6.

Krueger, J. I., and DiDonato, T. E. (2008). Social categorization and the perception of groups and group differences. Soc. Personality Psychol. Compass 2 (2), 733–750. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00083.x

Lee, L. N., Kim, M. J., and Hwang, W. J. (2019). Potential of augmented reality and virtual reality technologies to promote wellbeing in older adults. Appl. Sci. 9 (17), 3556. doi:10.3390/app9173556

Leung, X. Y., and Huang, X. (2023). How virtual reality moderates daily negative mood spillover among hotel frontline employees: a within-person field experiment. Tour. Manag. 95, 104680. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104680

Liu, F., Liu, D., Zhang, J., and Ma, J. (2019). The relationship between being envied and workplace ostracism: the moderating role of neuroticism and the need to belong. Personality Individ. Differ. 147, 223–228. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.040

Lockwood, P., and Kunda, Z. (1997). Superstars and me: predicting the impact of role models on the self. J. Personality Soc. Psychol. 73 (1), 91–103. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.73.1.91

Marescaux, E., De Winne, S., and Rofcanin, Y. (2021). Co-worker reactions to i-deals through the lens of social comparison: the role of fairness and emotions. Hum. Relat. 74 (3), 329–353. doi:10.1177/0018726719884103

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., and Mackey, J. D. (2014). Conceptual and empirical confounds in the organizational sciences: an explication and discussion. J. Organ. Behav. 35 (8), 1052–1063. doi:10.1002/job.1961

Mills, C. J., Tracey, D., Kiddle, R., and Gorkin, R. (2023). Evaluating a virtual reality sensory room for adults with disabilities. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 495. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-26100-6

Murtza, M. H., and Rasheed, M. I. (2022). The dark side of competitive psychological climate: exploring the role of workplace envy. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022. (ahead-of-print). doi:10.5465/ambpp.2022.14219abstract

Nadler, A., Malloy, T., and Fisher, J. D. (2008). in Social psychology of intergroup reconciliation: from violent conflict to peaceful co-existence (Oxford University Press).

Nijs, S., Dries, N., Van Vlasselaer, V., and Sels, L. (2022). Reframing talent identification as a status-organising process: examining talent hierarchies through data mining. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 32 (1), 169–193. doi:10.1111/1748-8583.12401

Nikandrou, I., and Tsachouridi, I. (2015). Towards a better understanding of the “buffering effects” of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions on employee outcomes. Manag. Decis. 53 (8), 1823–1842. doi:10.1108/md-06-2015-0251

O'Donnell, A. W., Neumann, D. L., Duffy, A. L., and Paolini, S. (2019). Learning to fear outgroups: an associative learning explanation for the development and reduction of intergroup anxiety. Soc. Personality Psychol. Compass 13 (3), e12442. doi:10.1111/spc3.12442

O'Reilly, J., Robinson, S. L., Berdahl, J. L., and Banki, S. (2015). Is negative attention better than no attention? The comparative effects of ostracism and harassment at work. Organ. Sci. 26 (3), 774–793. doi:10.1287/orsc.2014.0900

Reh, S., Tröster, C., and Van Quaquebeke, N. (2018). Keeping (future) rivals down: temporal social comparison predicts coworker social undermining via future status threat and envy. J. Appl. Psychol. 103 (4), 399–415. doi:10.1037/apl0000281

Robinson, S. L., O’Reilly, J., and Wang, W. (2013). Invisible at work: an integrated model of workplace ostracism. J. Manag. 39 (1), 203–231. doi:10.1177/0149206312466141

Rothbaum, B. O., Hodges, L., and Kooper, R. (1997). Virtual reality exposure therapy. J. Psychotherapy Pract. Res. 6, 219–226.

Schaubroeck, J., and Lam, S. S. (2004). Comparing lots before and after: promotion rejectees' invidious reactions to promotees. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 94 (1), 33–47. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2004.01.001

Schubert, T. W. (2003). The sense of presence in virtual environments: a three-component scale measuring spatial presence, involvement, and realness. Z. für Medien. 15 (2), 69–71. doi:10.1026//1617-6383.15.2.69

Slater, M. (2009). Place illusion and plausibility can lead to realistic behaviour in immersive virtual environments. Philosophical Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 364 (1535), 3549–3557. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0138

Slater, M., and Usoh, M. (1993). Representations systems, perceptual position, and presence in immersive virtual environments. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2 (3), 221–233. doi:10.1162/pres.1993.2.3.221

Smith, R. H. (2000). “Assimilative and contrastive emotional reactions to upward and downward social comparisons,” in Handbook of social comparison: theory and research, 173–200.

Somarathna, R., Bednarz, T., and Mohammadi, G. (2022). Virtual reality for emotion elicitation–a review. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 14, 2626–2645. doi:10.1109/taffc.2022.3181053

Spoor, J. R., and Williams, K. D. (2007). “The evolution of an ostracism detection system,” in Evolution and the social mind: evolutionary psychology and social cognition. Editors J. P. Forgas, M. G. Haselton, and W. von Hippel (New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor and Francis), 279–292.

Sumelius, J., Smale, A., and Yamao, S. (2020). Mixed signals: employee reactions to talent status communication amidst strategic ambiguity. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 31 (4), 511–538. doi:10.1080/09585192.2018.1500388

Tussing, D. V., Wihler, A., Astandu, T. V., and Menges, J. I. (2022). Should I stay or should I go? The role of individual strivings in shaping the relationship between envy and avoidance behaviors at work. J. Organ. Behav. 43 (4), 567–583. doi:10.1002/job.2593

Vecchio, R. P. (2005). Explorations in employee envy: feeling envious and feeling envied. Cognition Emot. 19 (1), 69–81. doi:10.1080/02699930441000148

Veiga, J. F., Baldridge, D. C., and Markóczy, L. (2014). Toward greater understanding of the pernicious effects of workplace envy. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 25 (17), 2364–2381. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.877057

Williams, K. D. (2007). Ostracism. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 58, 425–452. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085641

Witmer, B. G., and Singer, M. J. (1994). Measuring immersion in virtual environments. ARI Technical Report 1014. Alexandria, VA: US Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences.

Wu, C. H., Liu, J., Kwan, H. K., and Lee, C. (2016). Why and when workplace ostracism inhibits organizational citizenship behaviors: an organizational identification perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 101 (3), 362–378. doi:10.1037/apl0000063

Keywords: virtual reality, envy, workforce differentiation, inclusion, ostracism

Citation: van Zelderen APA, Dries N and Menges J (2024) The curse of employee privilege: harnessing virtual reality technology to inhibit workplace envy. Front. Virtual Real. 5:1260910. doi: 10.3389/frvir.2024.1260910

Received: 18 July 2023; Accepted: 14 March 2024;

Published: 28 March 2024.

Edited by:

Albert Jolink, École de Commerce Skema, FranceReviewed by:

Alessandro Innocenti, University of Siena, ItalyValerio Incerti, Université Côte d’Azur (GREDEG), France

Yvonne Van Everdingen, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Netherlands

Copyright © 2024 van Zelderen, Dries and Menges. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anand Prema Aschwin van Zelderen, YW5hbmQudmFuemVsZGVyZW5AYnVzaW5lc3MudXpoLmNo

Anand Prema Aschwin van Zelderen

Anand Prema Aschwin van Zelderen Nicky Dries2,3

Nicky Dries2,3