- INRS-EMT, University of Québec, Montréal, QC, Canada

Virtual reality (VR)-mediated rehabilitation is emerging as a useful tool for stroke survivors to recover motor function. Recent studies are showing that VR coupled with physiological computing (i.e., real-time measurement and analysis of different behavioral and psychophysiological signals) and feedback can lead to 1) more engaged and motivated patients, 2) reproducible treatments that can be performed at the comfort of the patient’s home, and 3) development of new proxies of intervention outcomes and success. While such systems have shown great potential for stroke rehabilitation, an extensive review of the literature is still lacking. Here, we aim to fill this gap and conduct a systematic review of the twelve studies that passed the inclusion criteria. A detailed analysis of the papers was conducted along with a quality assessment/risk of bias evaluation of each study. It was found that the quality of the majority of the studies ranked as either good or fair. Study outcomes also showed that VR-based rehabilitation protocols coupled with physiological computing can enhance patient adherence, improve motivation, overall experience, and ultimately, rehabilitation effectiveness and faster recovery times. Limitations of the examined studies are discussed, such as small sample sizes and unbalanced male/female participant ratios, which could limit the generalizability of the obtained findings. Finally, some recommendations for future studies are given.

1 Introduction

Recent statistics have shown that one in every four people over the age of 25 will suffer from stroke in their lifespan, with 60% occurring in people under the age of 70 (GBD Stroke Expert Group, 2018). With over 13 million new cases being reported annually worldwide, stroke is known to cause long-term cognitive and physical disabilities, thus affecting the quality-of-life of stroke survivors (Lindsay et al., 2019). Physical impairments can range from mild (hemiparesis) to severe (hemiplegia) and commonly affect the left or right side of the body, while cognitive impairments can range from memory, language, and attention dysfunction to neuropsychiatric consequences such as post-stroke depression (Blöchl et al., 2019). To assist with improvements in performing activities of daily life, physical rehabilitation is recommended right away or within 6 months after the onset of stroke to maximize the chances of success (Lee et al., 2015). Overall, based on principles of motor learning theory, neural plasticity can be modulated greater if the training method is purposefully repeated with sufficient repetition (Kleim and Jones, 2008). In fact, the frequency of the rehabilitation sessions and their intensity have been shown to be the key factors in recovery (Tollár et al., 2021).

In many places around the world, however, access to rehabilitation professionals multiple times within the week is not possible due to either high cost, personnel availability, or insurance coverage purposes, to name a few factors. As such, routine rehabilitation sessions are seldom achieved (Carvalho et al., 2017). To overcome this limitation, forms of in-home rehabilitation tools have been explored by exploiting technology-mediated interventions. Virtual reality (VR) has emerged as a low-cost, engaging, interactive, and effective option shown to enhance functional outcomes and decrease depression levels (Szczepańska-Gieracha et al., 2020). Recently, VR combined with an exoskeleton or with physiological computing tools has been proposed to improve upper/lower limb rehabilitation, balance control, walking, and gait performance (Frisoli et al., 2011; Cikajlo et al., 2013; Comani et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; Sheng et al., 2016; Berger and d’Avella, 2017; Zeiaee et al., 2017; Mubin et al., 2019). Here, physiological computing refers to the use of (multimodal) physiological data to monitor a user’s psycho-physiological state. Inferred states can then be used as feedback to the user or to the machine in an adaptive manner (Jacucci et al., 2015). Dynamic and customized virtual environments can then be easily updated to accommodate user-specific interventions, can be tailored to a patient’s specific rehabilitation plan, and allow for automated tracking of the patient’s progression and adjusting the task accordingly. Commonly, cost-effective data acquisition devices to monitor electroencephalography (EEG), electromyography (EMG), and electrooculography (EOG) have been explored in novel interventions.

VR-based interventions have relied on the patient interacting with virtual objects through either active hand movements or imagined movements detected via a brain-computer interface (BCI) (Mizuguchi et al., 2013; Eaves et al., 2016; Ruffino et al., 2017) or via biofeedback (Levin et al., 2012). Recent research has shown that modulating neuroplasticity through VR can improve the motor function and muscle strength of stroke survivors (Ekechukwu et al., 2021). In fact, in Corbetta et al. (2015), VR was shown to be a suitable substitute for conventional rehabilitation to improve walking speed, balance, and mobility in stroke patients. With VR systems, the sense of realism and perceived immersion play key roles in stroke rehabilitation (Suzuki et al., 2017; Kritikos et al., 2020). Realistic environments can provide more engaging content and motivate stroke survivors to use the systems more frequently, with reported improvements in their quality-of-life (You et al., 2005). Moreover, virtual experiences can influence the patient’s sense of ownership and agency over a virtual limb, i.e., embodiment (Perez-Marcos, 2018).

In order to provide the users with real-time feedback and a sense of control and involvement, physiological signal acquisition and processing is needed. Such signals may also be used to adjust the virtual environment autonomously, thus improving their sense of presence, especially for VR experiences based on head-mounted displays (HMDs) Sherman and Craig, (2003). Multimodal (bio)feedback, has in fact, been shown to improve rehabilitation outcomes; successful applications have been reported with motor control in children with dystonia (Casellato et al., 2012), chronic pain management (Gromala et al., 2015), and anxiety reduction (Bossenbroek et al., 2020), to name a few. The interested reader is referred to Kılıç et al. (2021) and Hao et al. (2021) for reviews on use of VR and physiological computing for fear and neural plasticity research, respectively.

Having this said, the use of HMD-based VR and physiological computing for stroke rehabilitation is also on the rise. However, no reviews summarizing the literature exist. To fill this gap, we conducted a systematic review of the existing literature to collect information about technological aspects of HMD systems, biosignal applications, and wearables (e.g., exoskeleton) that have been used for rehabilitation purposes. In particular, this study aimed to address the following questions:

(1) What physiological computing systems have been used with HMD-based VR and how effective have they been?;

(2) What equipment have been used and what advantages do certain psycho-physiological modalities offer over another?; and

(3) What clinical and non-clinical outcomes have been observed from these multimodal feedback based virtual reality interventions?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 contains the methodology used in this systematic review. Results are presented and discussed in Section 3, where limitations and recommendations for future studies are also described. Conclusion are finally presented in Section 4.

2 Methodology

This systematic review was conducted according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009).

2.1 Search Strategy

A search over English language peer-reviewed journal papers was conducted across five databases, including Scopus, IEEE, Web of Science, PubMed, and Science Direct, between the years January 2015 to December 2021. The following keywords were used: (electro* OR respiration OR “galvanic skin”) AND “stroke rehabilitation” AND “virtual reality.” The keywords were searched in the title or abstract of the articles. Mendeley reference manager was used to remove duplicate citations across yielded results. The term “physiological computing” was not used as a keyword as it is a very specialized term that few researchers in the VR space utilize at the moment. By including all possible modalities that begin with “electro” (e.g., electrocardiogram, electroencephalogram, electromyogram, electrooculogram, electrodermal activity) we are bound to encompass all studies that utilized physiological computing systems without referring to this terminology directly.

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria included articles that 1) used HMD-based VR experiences, 2) included at least one feedback modality to improve the VR experience, 3) included a valid clinical measure or questionnaire to gauge the effectiveness of the intervention, and 4) developed a rehabilitation tool but tested on healthy subjects. Exclusion criteria included: 1) review papers, 2) studies not relying on HMD-based VR, and 3) studies not focusing on stroke rehabilitation applications. Eligibility criteria according to population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study design (PICOS) has been tabulated in Supplementary Table S1 and made available in the supplementary material section. We note that studies with healthy people have only been included if the goal of study was aligned with providing interventions to the population of interest (as described in Supplementary Table S1).

2.3 Screening and Data Extraction

After searching the abovementioned databases and merging the duplicated results, the authors screened titles and abstracts to exclude unrelated articles. The full-text screening was then performed on the remaining papers and aligned articles were included in this systematic review. To collect detailed information from each study, a data extraction spreadsheet was developed encompassing details across three domains: 1) study design and demographics (targeted stroke group, number of subjects, control group, gender distribution, target problem, session description, trial design), 2) technological aspects (HMD device, VR engine used, physiological modality, type of feedback, equipment, and electrode placement), and 3) outcomes (clinical/non-clinical scales, clinical results, availability of baseline information, pre- and post-intervention comparisons, and follow-up findings).

2.4 Quality Assessment

To assess the risk of bias (ROB) in the included studies, we utilized the National Institutes of Health—National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH-NHLBI) quality assessment tool (National Institutes of Health, 2022), as well as the checklist for quasi-experimental studies based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tool Tufanaru et al. (2017). For the former, articles are evaluated based on the type of the study and overall quality is judged based on “good,” “fair,” or “poor” categories. Categories are chosen based on replies to a number of questions, where answers can take the form of yes, no, cannot determine, not reported, or not applicable. Both NIH-NHLBI and JBI tools examine studies across three aspects, including objectives, methodology, and report of outcomes.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Included Studies

From the 218 identified articles, 46 were from PubMed, 16 from ScienceDirect, 59 from IEEEXplore, 38 from Web of Science, and 59 from Scopus. Figure 1 depicts a flow chart of the study selection process. After eliminating duplicates, 182 studies were left to be screened based on title and abstract. From this first pass, 130 papers were eliminated as they did not meet the inclusion criteria, resulting in 52 articles included for full-length analysis. In the end, 12 articles focusing on HMD-VR, multimodal physiological computing, and stroke motor rehabilitation were included in this review.

3.2 Study Design

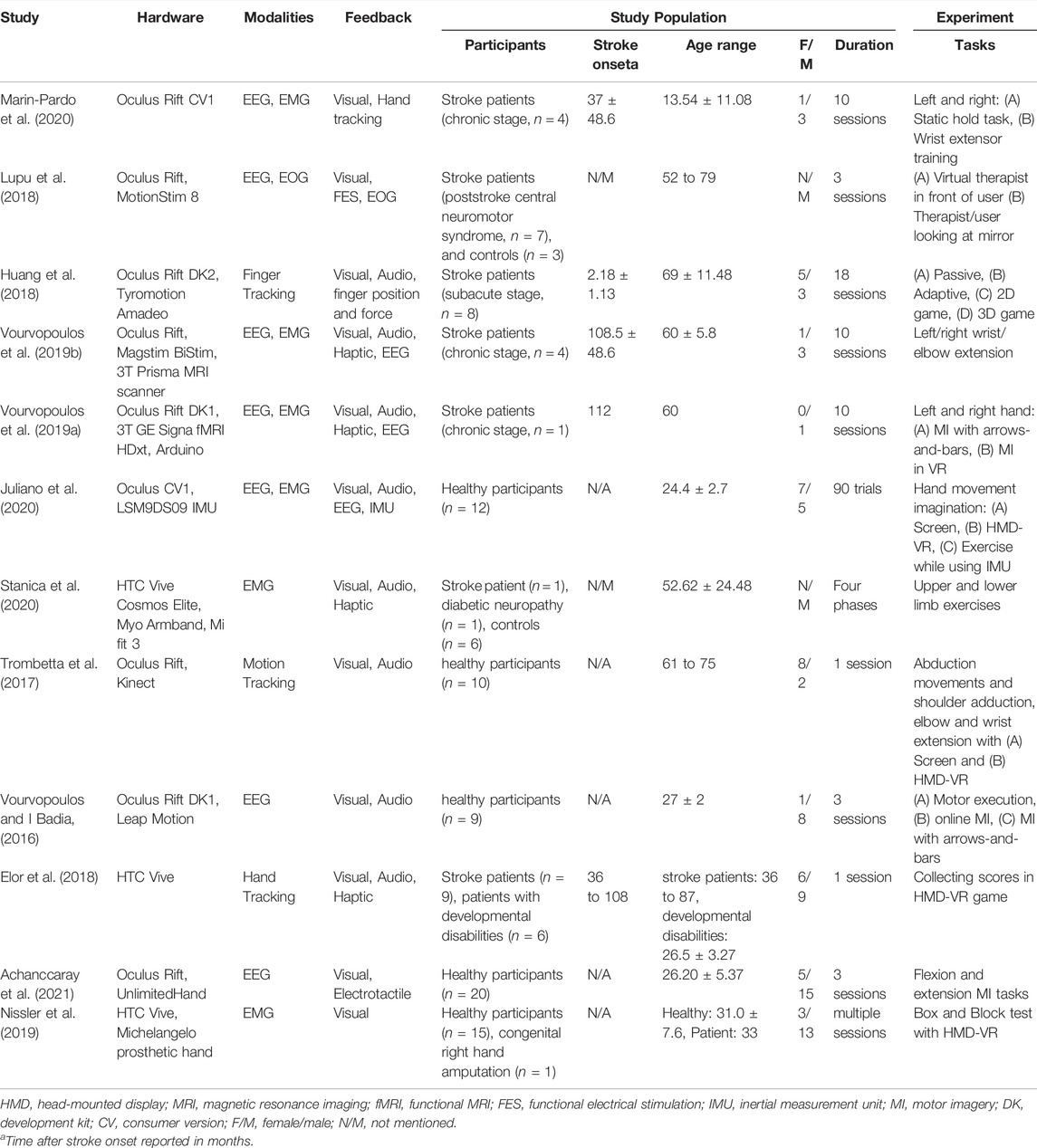

Detailed information about the configuration, modalities used, study type, experiment duration, and demographics of the participants are available in Table 1. Detailed description of hardware used to acquire the physiological signals are described in Table 2.

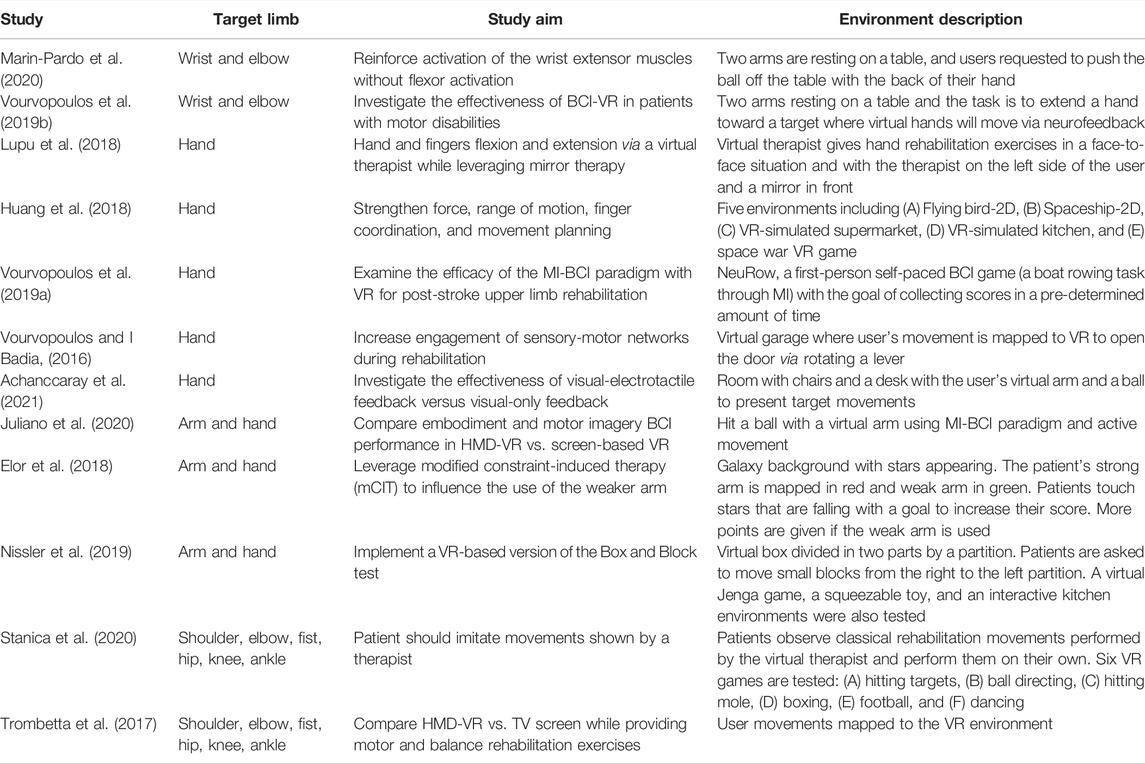

All of the included papers followed a “pre/post study design,” which refers to measuring specific metrics prior to the experiment and comparing them with recorded measures after the intervention (Thiese, 2014). As can be seen, among the included articles, four studies recruited only healthy subjects (Vourvopoulos and I Badia, 2016; Trombetta et al., 2017; Juliano et al., 2020; Achanccaray et al., 2021), three relied on patients who were in chronic stage of stroke (Vourvopoulos et al., 2019a; Vourvopoulos et al., 2019b; Marin-Pardo et al., 2020), three studies used a mixture of healthy and stroke patients (Lupu et al., 2018; Nissler et al., 2019; Stanica et al., 2020), one study used a stroke patient in sub-acute stage (Huang et al., 2018), and one study used a mixture of stroke patients in the chronic stage and patients with developmental disabilities (Elor et al., 2018). The reported numbers in Table 1 are for participants who have completed all the sessions and satisfied all experimental protocols. Overall, 64.1% of participants were healthy subjects, and only 40% of all participants were females.

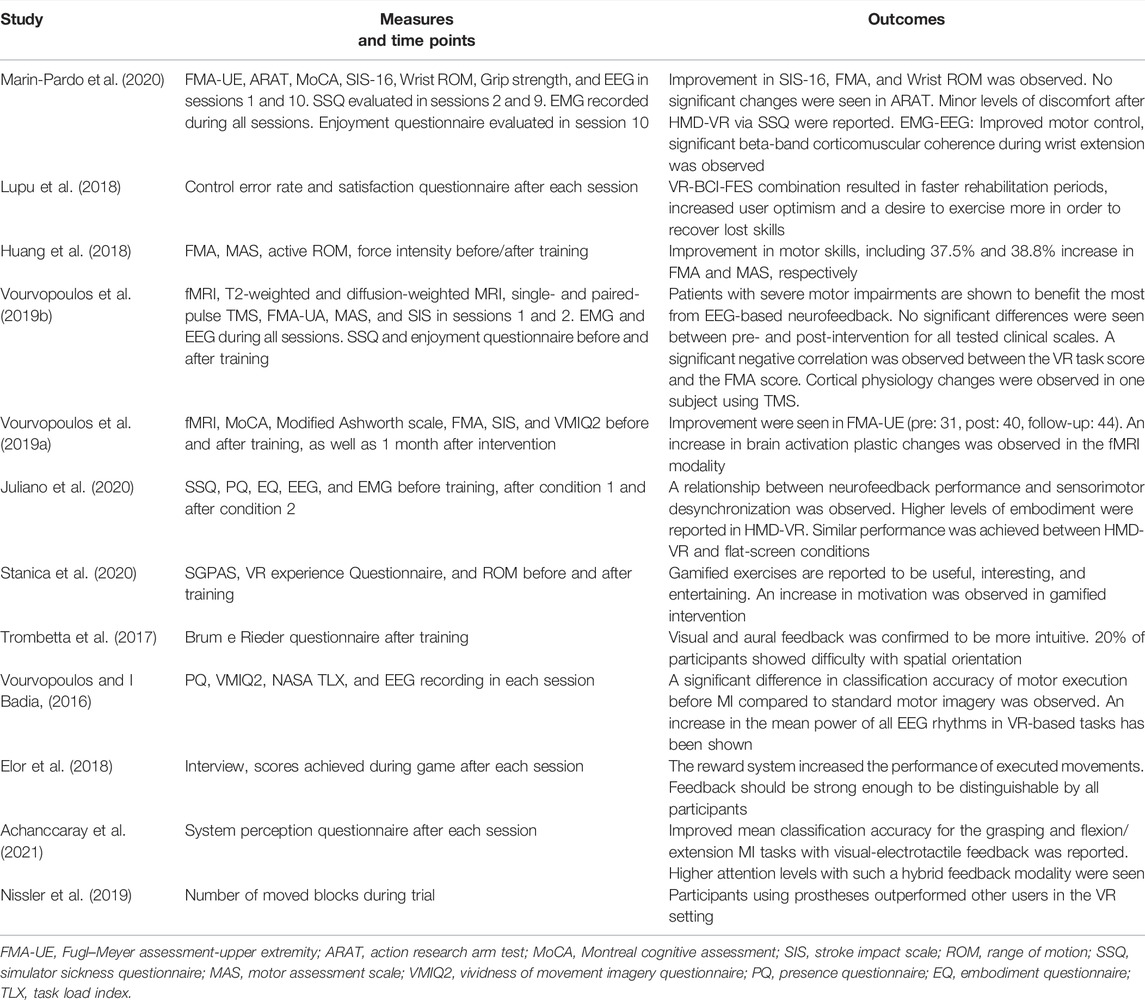

The reviewed studies relied on virtual environments to deliver rehabilitation exercises by means of gamified interventions. Ten articles focused on upper limb rehabilitation, while the remaining two studies focused on both upper and lower limbs (Juliano et al., 2020; Stanica et al., 2020). Table 3 details the characteristics of the study (i.e., the aim of the study, target limb, and virtual environment description). As can be seen, among the included articles, only three studies used more than two different virtual environments (Huang et al., 2018; Nissler et al., 2019; Stanica et al., 2020).

TABLE 3. Characteristic of reviewed studies, including target limbs, study aim, and virtual environment description.

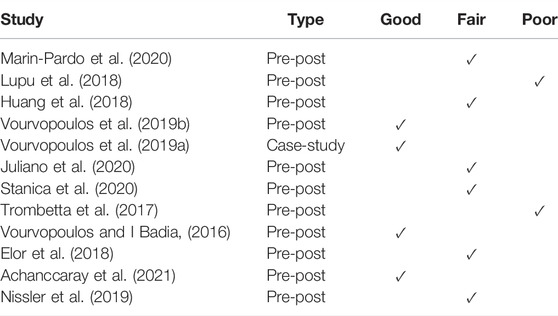

3.3 Quality Assessment

As one of the reviewed papers was a case report, the NIH-NHLBI quality assessment tool for case series studies and the JBI checklist for case reports was used. For the remainder of the studies, the NIH-NHLBI quality assessment tool for before-after (pre-post) studies with no control group and the JBI checklist for quasi-experimental studies was utilized. The detailed responses obtained by both of the assessment tools are presented in Supplementary Tables S2, S3, respectively, both available in the supplementary materials section. Table 4, in turn, presents the results of the quality evaluation using the NIH-NHLBI tool.

As can be seen, from the NIH-NHLBI analysis, the majority of the pre-post studies (n = 11) were rated as fair, while four studies were rated as good, and two as poor. The fair-rated studies showed clear objectives, eligibility criteria, selection of participants, targeting populations of interest, description of intervention, description of outcome measures, and multiple outcome measures, they reflected issues in terms of sample size, blinding of outcome assessors, and follow-up rate. Poor-rated studies, in turn, had issues concerning multiple outcome measures, statistical analysis, and group-level interventions. The case study, on the other hand, was rated good quality due to clarity of objectives, detailed description of population and intervention, valid and reliable outcome measurement, and well-described statistical method and results. In terms of JBI criteria, the issues flagged concerned lack of control group, receiving a similar treatment (except exposure to HMD-VR), and lack of follow-up plan. None of the articles showed issues with clarity of cause and effects of their study, similarity of participants, multiple measurement points of the outcome, or similar outcome measurements. Three articles, however, had issues with reliability of outcome measurements due to not using appropriate statistical analysis methods. For the case study, the JBI tool reflected “yes” responses to all of the checklist questions, thus corroborating its quality.

3.4 Technological Aspects

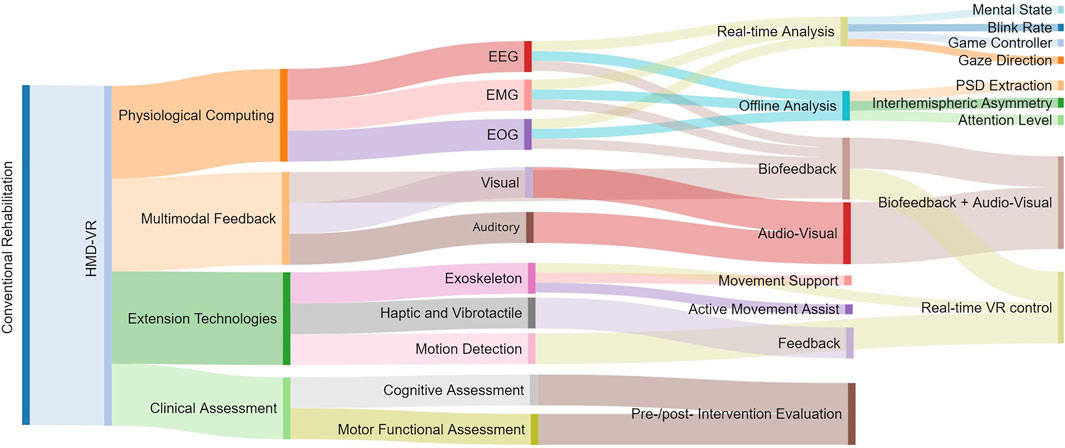

Overall, the included articles employed different types of technologies. Figure 2 demonstrates an alluvial diagram of the methods, their combinations, and target aim. As evidenced, different physiological modalities and technologies have been utilized in VR-based stroke rehabilitation interventions. The following subsections highlight these methods in detail.

FIGURE 2. Alluvial diagram illustrating mediated approaches and their combinations to shape significant usage within the framework of HMD-VR for rehabilitation.

3.4.1 Virtual Environment

The Unity3D game engine was reported as being the most common for virtual environments design, feedback control, and integration of external devices (e.g., biosignal acquisition systems) into the game flow. Wearable HMDs, which provide stereoscopic close-to-reality experience and increased perception of depth and immersion, were widely used. In particular, three studies used the HTC Vive HMD (Valve Washington, WA, United States), (Elor et al., 2018; Nissler et al., 2019; Stanica et al., 2020), while the remaining utilized an Oculus HMD (Oculus VR, Irvine, CA, United States), likely due to its accessibility to SDKs and lower price. In the studies, varying display refresh rates from 60 to 90 Hz were reported.

To deliver targeted rehabilitation-oriented content, custom environments were typically developed, though two studies relied on pre-developed games (Huang et al., 2018; Vourvopoulos et al., 2019a). For example, two studies implemented a virtual therapist to present exercises in a virtual environment (Lupu et al., 2018; Stanica et al., 2020). Nevertheless, only one study provided detailed information about the virtual environment design process, including the properties of different objects and the adjustment of feedback intensity (Elor et al., 2018). The other reviewed articles failed to provide comprehensive information about concepts of human-centered design, including signifiers, affordances, mapping, and conceptual models (Norman, 2013).

Lastly, a first-person point of view (POV) was shown to be very popular in the reviewed articles, where nine studies had a first-person perspective (patient performs from character’s POV), two studies exploited third-person playing mode (patient controls a virtual avatar) (Trombetta et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2018), and one study had both settings (Lupu et al., 2018). It is known that the first-person perspective increases the sense of embodiment (limb ownership and self-location) while the third-person perspective provides space awareness (Gorisse et al., 2017).

3.4.2 Physiological Computing

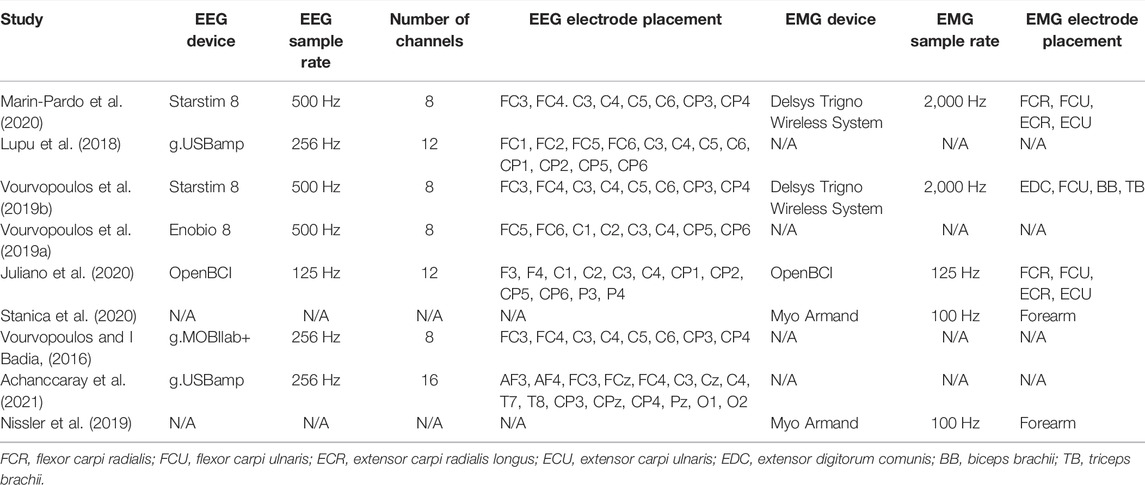

Physiological computing has emerged as a powerful tool in human-computer interaction, allowing real-time physiological signal analysis and behavioral information to enhance the interaction by conveying user cognitive/mental/affective state information to the machine, as well as real-time information about patient movement, thus improving the sense of embodiment. Moreover, physiological/behavioral data can provide insights into both conscious and unconscious processes and thus may also convey information about the user’s motivational and intentional states. More recently, as wearable devices burgeon, physiological computing has started to gain traction for at-home uses. This, coupled with HMD advances and a drop in costs, has resulted in the development of new in-home VR-based rehabilitation systems. Table 2 presents technical information about the EEG and EMG wearable devices used in the reviewed papers, including a description of the devices themselves, their sample rates, and electrode placement details. Inertial measurement units (IMUs) have also been utilized for motion/behavioral tracking and EOG signals to assess if the tests were performed correctly (Lupu et al., 2018). More details about these modalities are provided below.

3.4.2.1 EEG

As seen in Table 2, seven articles have relied on EEG-based physiological computing methods in their VR rehabilitation studies. Since the main aim of the studies concerns motor improvement, most studies acquired EEG signals from electrodes over the motor cortex, corresponding to positions FC3, FC4, C3, C4, C5, C6, CP3, and CP4 electrodes in the 10–20 international positioning system. In terms of BCI paradigms, six studies relied on motor imagery (MI) (Vourvopoulos and I Badia, 2016; Lupu et al., 2018; Vourvopoulos et al., 2019a; Vourvopoulos et al., 2019b; Juliano et al., 2020; Achanccaray et al., 2021). The underlying hypothesis with MI is that illusions of movement and a strong feeling of embodiment could improve the neural plasticity needed for rehabilitation, with physiological computing and real-time feedback contributing to an improved embodiment. Sub-acute stroke patients, for example, who used MI-based paradigms could then improve functional outcomes (Carrasco and Aboitiz Cantalapiedra, 2016). Stronger desynchronization in the alpha (7–13 Hz) and beta (13–30 Hz) EEG bands of the ipsilesional hemisphere, for example, has been shown (Pichiorri et al., 2015). Additionally, increased hemispheric asymmetry has been shown in MI sessions with feedback, suggesting enhancement in fine motor task performance and modifying motor learning (Neuper et al., 1999; Garry et al., 2004). In fact, differences in interhemispheric asymmetry in stroke patients have been reported relative to a control group Berenguer-Rocha et al. (2020), thus suggesting that physiological computing could be used not only to customize the environment, but to also track intervention progress and success (Cicinelli et al., 2003). The impact of HMD-based rehabilitation has also been quantified by means of post-hoc comparisons based on event-related synchronization/desynchronization (ERS/ERD) (Vourvopoulos et al., 2019b), corticomuscular coherence (i.e., synchronization between EEG and EMG signals) (Marin-Pardo et al., 2020), resting-state alpha rhythm (Vourvopoulos et al., 2019a), and EEG rhythm power spectral analyses (Vourvopoulos and I Badia, 2016; Juliano et al., 2020; Achanccaray et al., 2021).

3.4.2.2 EMG

EMG provides information about the electrical activity of the muscles. The location of electrodes is typically determined based on the aim of the study, i.e., to improve the function of the upper or lower limb. Upper limb studies can include muscles of the hand, wrist, elbow, and rear-/fore-arm, whereas lower limbs can include the foot, ankle, knee, thigh, and hip. As shown in Table 2, only five of the twelve relied on EMG signals, two of which used a Delsys Trigno Wireless System (Delsys Incorporated, Natick, MA, United States) (Vourvopoulos et al., 2019b; Marin-Pardo et al., 2020), two used Myo armbands (Thalmic Labs) (Nissler et al., 2019), and one used an OpenBCI bioamplifier (Juliano et al., 2020). These systems operated at sample rates of 2,000, 100, and 125 Hz, respectively. In addition to post-hoc EMG analyses to monitor the physical improvement due to rehabilitation (e.g., EMG amplitude, rest/active state detection), three studies relied on EMG signals to map the patient’s arm/hand into the VR environment to improve the sense of embodiment (Nissler et al., 2019; Marin-Pardo et al., 2020; Stanica et al., 2020).

3.4.2.3 Motion Tracking

While EMG can provide information about limb motion, it lacks details about e.g., arm/hand orientation. To this end, inertial measurement unit (IMUs) have been used as a real-time tool to map arm/hand direction onto the virtual environment. For example, Juliano et al. (2020) relied on IMUs to match the virtual arm/hand movements with the user’s actual arm/hand movements. Similarly, the controllers used by VR systems can be used as a motion-tracking tool, in addition to delivering haptic feedback (Elor et al., 2018; Nissler et al., 2019). Lastly, optical tracking tools, such as a Leap Motion (Leap Motion, Inc., San Francisco, CA, United States) tracking device Vourvopoulos and I Badia, (2016) have been used to map hand orientation and finger movements into the virtual environment.

3.4.3 Feedback Modality

Feedback is known to improve the sense of embodiment and to also foster plasticity (Kumru et al., 2016; Alimardani et al., 2018), thus is widely used in neuro-rehabilitation. Visual and audio-based feedback modalities are the most classic form of feedback, but more recent studies have been exploring the use of haptic (e.g., by the controllers, as mentioned above) feedback to improve the sense of immersion and presence. Feedback needs to be easily distinguishable, especially by the patient population (Trombetta et al., 2017; Elor et al., 2018), thus the volume of audio cues, the shape and color of visual cues, and the intensity of haptic cues are of indispensable importance. In certain conditions, voluntary movement is still not possible by the patient, thus an exoskeleton is used to provide the intended feedback. Additionally, more recent methods have relied on the use of functional electrical stimulation (FES) Lupu et al. (2018) as a form of feedback, where subtle electrical charges are applied to certain muscles in order to contract them upon detection of motor activation signals from EEG, for example. In the sections below, more details are provided on exoskeleton and haptics-based feedback modalities.

3.4.3.1 Exoskeleton-Based Feedback

Exoskeleton-based rehabilitation relies on robotic or non-robotic assistive devices which help the patients perform exercises correctly, safely, and in a sustained manner with or without predefined force intensities (Mubin et al., 2019). The exoskeleton can be set in active, passive, or assistive modes (Morone et al., 2020). In the reviewed articles, only one paper relied on exoskeletons. In particular, Huang et al. (2018) used a 5-degree-of-freedom Amadeo (Tyromotion GmbH, Graz, Austria) along with audio-visual feedback. The device provided patients with control over finger movements, force, and velocity.

3.4.3.2 Haptics-Based Feedback

Haptic feedback adds the sense of touch to the virtual experience and increases the sense of immersion (Kim et al., 2017). Gloves, controllers, armbands, or even exoskeletons can be used to provide haptic feedback (Rose et al., 2018). As seen from Table 1, five studies relied on haptic feedback, where three used the VR system controllers to provide vibration feedback (Elor et al., 2018; Vourvopoulos et al., 2019b; Stanica et al., 2020), one proposed a custom device based on vibrating motors (Vourvopoulos et al., 2019a), one used the UnlimitedHand (H2L Inc., Tokyo, Japan) device to supply electrotactile stimulation feedback (Achanccaray et al., 2021). Haptic feedback was used primarily in these studies to inform the subject when a task was finalized and/or in response to an interaction with a specific object in the virtual environment.

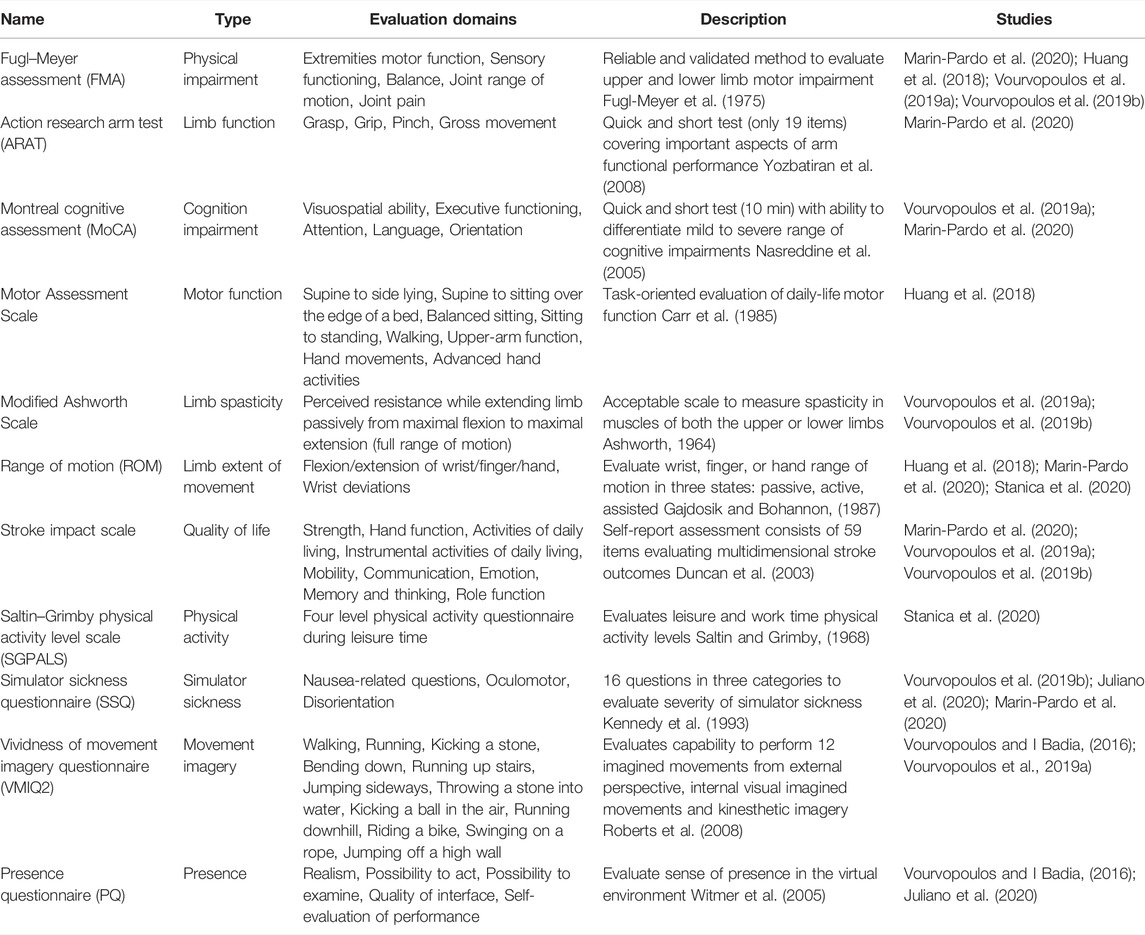

3.5 Clinical/Non-Clinical Reported Outcomes

The reviewed papers relied on multiple approaches to measure the efficacy of their proposed methods. For example, several different questionnaires, physiological signal analyses, and clinical measures were explored. Table 5, presents a description and evaluation domains of the most-utilized clinical/non-clinical scales reported in the papers. As interventions may have outcomes across numerous domains, it is common for studies to use more than one assessment method. As seen from the Table, seven clinical scales have been used most often, including the Fugl–Meyer assessment (FMA), action research arm test (ARAT), Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA), motor assessment scale, modified Ashworth scale, range of motion (ROM), and stroke impact scale (SIS). Studies typically compared these metrics pre- and post-intervention to gauge the benefits of the VR therapy. Further, to assess detailed alterations in the brain and plasticity improvements, two studies relied on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and functional MRI (fMRI) (Vourvopoulos et al., 2019b,a). Table 6 includes the significant final outcomes observed by the studies, as well as the time points in which clinical/non-clinical measures were taken for comparisons.

In terms of clinical measures, various metrics are observational, meaning that a clinician (or a physiotherapist) determines a score after the patient performs a specific task. Five studies relied on a certified occupational therapist or rehabilitation specialist to carry out these observational clinical measures (Huang et al., 2018; Vourvopoulos et al., 2019a; Vourvopoulos et al., 2019b; Marin-Pardo et al., 2020; Stanica et al., 2020). FMA and SIS can be seen to be the most widely used measures. However, FMA has been shown to be subject to ceiling effects (Lin et al., 2004), whereas SIS potentially has ceiling effects in hand function, memory and thinking, communication, mobility and activities of daily living (ADL), and instrumental ADL domains (Richardson et al., 2016).

In terms of non-clinical measures, post-hoc physiological computing tools have been leveraged to extract changes in the measured biosignals. For example, Vourvopoulos and I Badia, (2016) reported differences in EEG activity of motor imagery in virtual environments relative to regular imagery. In fact, the ANOVA test with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction and pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed a statistically significant result in the alpha band (F(2.524,20.191) = 4.800,

To this end, Vourvopoulos and I Badia, (2016) found a relationship between the ability to perform kinesthetic imagery and alpha-beta band modulation (ρ = 0.50, p

VR-based solutions typically rely on their improved sense of realism (Read et al., 2021), immersion and presence (Slater, 2009), and sense of embodiment (Riva et al., 2019) to boost rehabilitation performance (Lin et al., 2001). To achieve these goals, Vourvopoulos et al. (2019b), for example, customized hand models in the virtual environment to match the patient’s skin tone and gender and Stanica et al. (2020) provided close-to-reality animations of outdoor exercises. Juliano et al. (2020), in turn, leveraged linear regression to examine the relationship between neurofeedback performance and overall embodiment and reported a significant relationship in the HMD-VR experimental condition (F(1,10) = 8.293, p = 0.016, R2 = 0.399).

The gamification potential of VR-based solutions can also allow for reward mechanisms to be put in place to improve outcomes. For example, the reward has been shown to improve motor learning (Nikooyan and Ahmed, 2015; Chen et al., 2018) and rehabilitation outcomes (Quattrocchi et al., 2017; Widmer et al., 2017). Reinforcement feedback also induces motivation (Vassiliadis et al., 2021). This is important, as lack of motivation has been said to be one of the major barriers in conventional rehabilitation (Damush et al., 2007). As such, reward-based VR interventions improve outcomes (Abe et al., 2011), result in higher rates of satisfaction, and have increased adherence (Trombetta et al., 2017; Elor et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2018; Stanica et al., 2020). For example, Elor et al. (2018) encouraged patients to use their affected weaker limb by giving them higher scores when an action was carried out with such affected limb. Overall, only four of the reviewed articles relied on reward feedback as part of their intervention (Trombetta et al., 2017; Elor et al., 2018; Nissler et al., 2019; Stanica et al., 2020).

Notwithstanding, VR-based solutions relying on HMDs are also known to elicit in certain individuals discomfort and nausea (known as cybersickness). Trombetta et al. (2017), for example, reported a subtle improvement in the sense of comfort when screen-based tasks were given to the participants, relative to those given via an HMD. Other studies, in turn, utilized the simulator sickness questionnaire, and only very minor degrees of discomfort were reported when using HMD-VR (Vourvopoulos et al., 2019b; Marin-Pardo et al., 2020). More recently, cybersickness has been associated with activity in delta (1–4 Hz), theta, and alpha EEG frequency bands (Krokos and Varshney, 2021). Future studies could also explore the use of collected EEG signals to measure cybersickness levels; this was not performed in any of the evaluated papers. Moreover, it is known that stroke can result in a range of cognitive impairments, thus it is necessary to investigate the perception and interaction skills of patients (Sun et al., 2014) in virtual environments. To this end, Nissler et al. (2019) implemented a clinical assessment method called Box and Block test in a virtual environment to measure gross manual dexterity and compared the performance of the patients in both conventional and VR-based settings. The results showed better control of a virtual prosthesis by a patient compared to the healthy control group.

Lastly, one additional advantage of a VR-based intervention with physiological computing is that it enables automated, repeatable, and reliable interventions. Such factors are crucial for treatment fidelity, which has been directly linked with intervention quality (Hildebrand et al., 2012). For example, Resnick et al. (2011) proposed a treatment fidelity plan based on design, training, delivery, receipt, and enactment for stroke exercise interventions. In non-VR-based interventions, there is a great chance of inconsistency in delivering the treatment by a physiotherapist. VR-based treatments, in turn, are programmed, thus system functionality could be used as a proxy for treatment fidelity (Coons et al., 2011). While the study by Stanica et al. (2020) utilized a specific order for all of the participants to assure consistency in the treatment, none of the reviewed articles used a fidelity checklist explicitly.

3.6 Limitations and Future Study Recommendations

The included articles show the potential of VR-based interventions, coupled with physiological computing, for improved rehabilitation outcomes for stroke survivors. Notwithstanding, none of the articles followed a “randomized control trial” study design, which is preferred to investigate clinical results. Moreover, studies frequently reported a small sample size as a limitation, and only two articles reported a gender-balanced participant pool, thus making generalization of the results difficult (Miller et al., 1993; Butler et al., 2009). Moreover, several studies investigated the efficacy of an HMD-based intervention received in parallel with conventional therapy, thus making it difficult to truly gauge the benefits of the VR intervention per se. Overall, nonetheless, the results suggest that an additional VR-based intervention (in addition to the conventional treatment) is better than having two conventional treatments. Moreover, patient involvement is crucial for successful rehabilitation outcomes (Kristensen et al., 2016). As the majority of stroke patients will be older in age, they may be strangers to burgeoning VR and physiological computing (e.g., wearables) tools. Future studies should assure that sufficient training sessions and/or tutorials are provided and that the tasks can be achieved even by those with cognitive impairments resultant from the stroke. Incorporating some principles from iterative designing (Nielsen and Molich, 1990) and gamer user experience into the virtual environment could be beneficial (Tondello et al., 2016; Rajanen and Rajanen, 2018). Integrating many of the physiological computing tools directly into the VR headset could also alleviate some of these issues; such instrumented HMDs are already emerging (Cassani et al., 2018; Cassani et al., 2020a; Moinnereau et al., 2020).

Moreover, the examined studies measured intervention efficacy pre and post-intervention, thus providing limited insights on the long-term effects of VR-based rehabilitation. Future studies should focus on the long-term effects of these interventions. Moreover, the reviewed articles relied on “passive” physiological computing tools, in the sense that signals were measured and used to either change the virtual environment or to gauge intervention outcomes. More “active” tools, such as non-invasive brain stimulation (e.g., transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation, tDCS), have recently emerged and shown to provide some success in rehabilitation when coupled with VR (Cassani et al., 2020b). Future studies could couple passive and active physiological computing (e.g., via an EEG-tDCS headset) and explore the benefits that such hybrid architectures could bring. As observed herein, the majority of the studies utilized EEG sensors to measure neural responses and plasticity. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) is also emerging as a useful tool for plasticity monitoring (Balconi, 2016) and hybrid fNIRS-EEG headsets are already available in the market. As such, future studies could explore the advantages of integrating the improved spatial resolution advantages of fNIRS with the improved temporal resolution of EEG for stroke rehabilitation. Alternate feature representations, beyond simple ERD/ERS and EEG frequency subband powers, could also be explored as proxies of brain plasticity and intervention outcomes (Papadopoulos et al., 2021).

Regarding the effects of feedback type, studies herein showed that as more senses were stimulated, improved outcomes and attention could be observed. Recently, olfactory feedback has emerged as an additional feedback modality, as tools such as the OVR ION (OVR Tech, Burlington, VT, United States) have appeared in the market. Integrating olfactory feedback may further boost attention, sense of embodiment, and presence, which could show improvements in outcomes, as was the case in other allied domains (Gim et al., 2015; Longobardi et al., 2020). Additionally, none of the studies used glove-based haptic feedback systems. Such systems could provide finger tracking capabilities and individual finger and full hand vibrations, thus potentially also benefiting interventions of the upper limbs (Caeiro-Rodríguez et al., 2021; Gast et al., 2021). Lastly, the reviewed studies did not report experiments with patients suffering from post-stroke visual impairment/disturbances. Such patients may be incapable of benefiting completely from audio-visual VR-based interventions, thus multisensory experiences should be explored. The work of Wedoff et al. (2019) and Real and Araujo (2020), for example, leveraged the use of auditory and haptic stimuli to make VR experiences more accessible to those with visual impairments. In fact, VR interventions could potentially be used soon after the stroke to identify the risk of visual after-effects (Besic et al., 2019).

4 Conclusion

This paper systematically reviewed the recent literature on HMD-based VR stroke rehabilitation treatments, which leveraged the use of physiological computing. We described and discussed the technological aspects of existing solutions, study design, and intervention outcomes, as reported in the reviewed papers. Limitations of existing solutions are also described, and recommendations for future studies are provided. Ultimately, VR-based interventions coupled with physiological computing have been shown to improve patient attention and engagement, improve the sense of embodiment, allow for rewards to be given, thus increasing motivation, and allow for repeatable and consistent treatment. Combined, these factors could lead to improved rehabilitation outcomes.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council (NSERC) of Canada (RGPIN-2021-03246).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lucas R. Trambaiolli, Dr. Raymundo Cassani and Belmir de Jesus Junior for useful insights, comments, and discussions.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frvir.2022.889271/full#supplementary-material

References

Abe, M., Schambra, H., Wassermann, E. M., Luckenbaugh, D., Schweighofer, N., and Cohen, L. G. (2011). Reward Improves Long-Term Retention of a Motor Memory Through Induction of Offline Memory Gains. Curr. Biol. 21, 557–562. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.02.030

Achanccaray, D., Izumi, S.-I., and Hayashibe, M. (2021). Visual-electrotactile Stimulation Feedback to Improve Immersive Brain-Computer Interface Based on Hand Motor Imagery. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021, 13. doi:10.1155/2021/8832686

Alimardani, M., Nishio, S., and Ishiguro, H. (2018). Brain-Computer Interface and Motor Imagery Training: The Role of Visual Feedback and Embodiment. Evol. BCI Therapy-Engaging Brain State. Dyn. 2, 64. doi:10.5772/intechopen.78695

Ashworth, B. (1964). Preliminary Trial of Carisoprodol in Multiple Sclerosis. Practitioner 192, 540–542.

Balconi, M. (2016). Brain Plasticity and Rehabilitation by Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Neuropsychol. Trends 19, 71–82. doi:10.7358/neur-2016-019-balc

Berenguer-Rocha, M., Baltar, A., Rocha, S., Shirahige, L., Brito, R., and Monte-Silva, K. (2020). Interhemispheric Asymmetry of the Motor Cortex Excitability in Stroke: Relationship with Sensory-Motor Impairment and Injury Chronicity. Neurol. Sci. 41, 2591–2598. doi:10.1007/s10072-020-04350-4

Berger, D. J., and d’Avella, A. (2017). “Towards a Myoelectrically Controlled Virtual Reality Interface for Synergy-Based Stroke Rehabilitation,” in Converging Clinical and Engineering Research on Neurorehabilitation II (Springer), 965–969. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46669-9_156

Besic, I., Avdagic, Z., and Hodzic, K. (2019). “Virtual Reality Test Setup for Visual Impairment Studies,” in 2019 IEEE 15th International Scientific Conference on Informatics (IEEE). doi:10.1109/informatics47936.2019.9119323

Blöchl, M., Meissner, S., and Nestler, S. (2019). Does Depression after Stroke Negatively Influence Physical Disability? a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. J. Affect. Disord. 247, 45–56. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.082

Bossenbroek, R., Wols, A., Weerdmeester, J., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., Granic, I., and van Rooij, M. M. J. W. (2020). Efficacy of a Virtual Reality Biofeedback Game (DEEP) to Reduce Anxiety and Disruptive Classroom Behavior: Single-Case Study. JMIR Ment. Health 7, e16066. doi:10.2196/16066

Brett, C. E., Sykes, C., and Pires-Yfantouda, R. (2017). Interventions to Increase Engagement with Rehabilitation in Adults with Acquired Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 27, 959–982. doi:10.1080/09602011.2015.1090459

Butler, A. A., Menant, J. C., Tiedemann, A. C., and Lord, S. R. (2009). Age and Gender Differences in Seven Tests of Functional Mobility. J. Neuroeng Rehabil. 6, 31–39. doi:10.1186/1743-0003-6-31

Caeiro-Rodríguez, M., Otero-González, I., Mikic-Fonte, F. A., and Llamas-Nistal, M. (2021). A Systematic Review of Commercial Smart Gloves: Current Status and Applications. Sensors 21, 2667. doi:10.3390/s21082667

Carr, J. H., Shepherd, R. B., Nordholm, L., and Lynne, D. (1985). Investigation of a New Motor Assessment Scale for Stroke Patients. Phys. Ther. 65, 175–180. doi:10.1093/ptj/65.2.175

Carvalho, E., Bettger, J. P., and Goode, A. P. (2017). Insurance Coverage, Costs, and Barriers to Care for Outpatient Musculoskeletal Therapy and Rehabilitation Services. N. C. Med. J. 78, 312–314. doi:10.18043/ncm.78.5.312

Casellato, C., Pedrocchi, A., Zorzi, G., Vernisse, L., Ferrigno, G., and Nardocci, N. (2012). EMG-Based Visual-Haptic Biofeedback: a Tool to Improve Motor Control in Children with Primary Dystonia. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 21, 474–480. doi:10.1109/TNSRE.2012.2222445

Cassani, R., Moinnereau, M.-A., Ivanescu, L., Rosanne, O., and Falk, T. H. (2020a). Neural Interface Instrumented Virtual Reality Headsets: Toward Next-Generation Immersive Applications. IEEE Syst. Man. Cybern. Mag. 6, 20–28. doi:10.1109/msmc.2019.2953627

Cassani, R., Novak, G. S., Falk, T. H., and Oliveira, A. A. (2020b). Virtual Reality and Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation for Rehabilitation Applications: a Systematic Review. J. Neuroeng Rehabil. 17, 147–216. doi:10.1186/s12984-020-00780-5

Cassani, R., Moinnereau, M.-A., and Falk, T. H. (2018). “A Neurophysiological Sensor-Equipped Head-Mounted Display for Instrumental QOE Assessment of Immersive Multimedia,” in 2018 Tenth International Conference on Quality of Multimedia Experience (QoMEX) (IEEE), 1–6. doi:10.1109/qomex.2018.8463422

Carrasco, D. G., and Aboitiz Cantalapiedra, J. (2016). Effectiveness of Motor Imagery or Mental Practice in Functional Recovery after Stroke: a Systematic Review. Neurol. Engl. Ed. 31, 43–52. doi:10.1016/j.nrleng.2013.02.008

Chen, X., Holland, P., and Galea, J. M. (2018). The Effects of Reward and Punishment on Motor Skill Learning. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 20, 83–88. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.11.011

Cicinelli, P., Pasqualetti, P., Zaccagnini, M., Traversa, R., Oliveri, M., and Rossini, P. M. (2003). Interhemispheric Asymmetries of Motor Cortex Excitability in the Postacute Stroke Stage. Stroke 34, 2653–2658. doi:10.1161/01.str.0000092122.96722.72

Cikajlo, I., Krpič, A., and Gorišek-Humar, M. (2013). “Changes in EMG Latencies during Balance Therapy Using Enhanced Virtual Reality with Haptic Floor,” in 2013 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) (IEEE), 4129–4132. doi:10.1109/embc.2013.6610454

Comani, S., Velluto, L., Schinaia, L., Cerroni, G., Serio, A., Buzzelli, S., et al. (2015). Monitoring Neuro-Motor Recovery from Stroke with High-Resolution EEG, Robotics and Virtual Reality: a Proof of Concept. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 23, 1106–1116. doi:10.1109/tnsre.2015.2425474

Coons, M. J., Roehrig, M., and Spring, B. (2011). The Potential of Virtual Reality Technologies to Improve Adherence to Weight Loss Behaviors. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 5, 340–344. doi:10.1177/193229681100500221

Corbetta, D., Imeri, F., and Gatti, R. (2015). Rehabilitation that Incorporates Virtual Reality Is More Effective Than Standard Rehabilitation for Improving Walking Speed, Balance and Mobility After Stroke: a Systematic Review. J. Physiother. 61, 117–124. doi:10.1016/j.jphys.2015.05.017

Damush, T. M., Plue, L., Bakas, T., Schmid, A., and Williams, L. S. (2007). Barriers and Facilitators to Exercise Among Stroke Survivors. Rehabil. Nurs. 32, 253–260. doi:10.1002/j.2048-7940.2007.tb00183.x

Danzl, M. M., Etter, N. M., Andreatta, R. D., and Kitzman, P. H. (2012). Facilitating Neurorehabilitation Through Principles of Engagement. J. Allied Health 41, 35–41.

Duncan, P. W., Lai, S. M., Bode, R. K., Perera, S., DeRosa, J., Investigators, G. A., et al. (2003). Stroke Impact Scale-16: A Brief Assessment of Physical Function. Neurology 60, 291–296. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000041493.65665.d6

Eaves, D. L., Riach, M., Holmes, P. S., and Wright, D. J. (2016). Motor Imagery During Action Observation: a Brief Review of Evidence, Theory and Future Research Opportunities. Front. Neurosci. 10, 514. doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00514

Ekechukwu, E. N. D., Nzeakuba, I. C., Dada, O. O., Nwankwo, K. O., Olowoyo, P., Utti, V. A., et al. (2021). “Virtual Reality, a Neuroergonomic and Neurorehabilitation Tool for Promoting Neuroplasticity in Stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis,” in Congress of the International Ergonomics Association (Springer), 495–508. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-74614-8_64

Elor, A., Teodorescu, M., and Kurniawan, S. (2018). Project Star Catcher. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 11, 1–25. doi:10.1145/3265755

Frisoli, A., Sotgiu, E., Procopio, C., Bergamasco, M., Rossi, B., and Chisari, C. (2011). “Design and Implementation of a Training Strategy in Chronic Stroke with an Arm Robotic Exoskeleton,” in 2011 IEEE Int Conf Rehabil Robot, 5975512. doi:10.1109/ICORR.2011.5975512

Fugl-Meyer, A. R., Jääskö, L., Leyman, I., Olsson, S., and Steglind, S. (1975). The Post-Stroke Hemiplegic Patient. 1. A Method for Evaluation of Physical Performance. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 7, 13–31.

Gajdosik, R. L., and Bohannon, R. W. (1987). Clinical Measurement of Range of Motion. Phys. Ther. 67, 1867–1872. doi:10.1093/ptj/67.12.1867

Garry, M. I., Kamen, G., and Nordstrom, M. A. (2004). Hemispheric Differences in the Relationship between Corticomotor Excitability Changes Following a Fine-Motor Task and Motor Learning. J. Neurophysiology 91, 1570–1578. doi:10.1152/jn.00595.2003

Gast, O., Makhkamova, A., Werth, D., and Funk, M. (2021). “Haptic Interaction for VR: Use-Cases for Learning and UX, Using the Example of the BMBF Project SmartHands,” in International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (Springer), 562–577. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-77750-0_36

GBD Stroke Expert Group (2018). Global, Regional, and Country-specific Lifetime Risks of Stroke, 1990 and 2016. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 2429–2437. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1804492

Gim, M.-N., Lee, S.-b., Yoo, K.-T., Bae, J.-Y., Kim, M.-K., and Choi, J.-H. (2015). The Effect of Olfactory Stimuli on the Balance Ability of Stroke Patients. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 27, 109–113. doi:10.1589/jpts.27.109

Gorisse, G., Christmann, O., Amato, E. A., and Richir, S. (2017). First- and Third-Person Perspectives in Immersive Virtual Environments: Presence and Performance Analysis of Embodied Users. Front. Robot. AI 4, 33. doi:10.3389/frobt.2017.00033

Gromala, D., Tong, X., Choo, A., Karamnejad, M., and Shaw, C. D. (2015). “The Virtual Meditative Walk: Virtual Reality Therapy for Chronic Pain Management,” in Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 521–524.

Hao, J., Xie, H., Harp, K., Chen, Z., and Siu, K.-C. (2021). Effects of Virtual Reality Intervention on Neural Plasticity in Stroke Rehabilitation: a Systematic Review. Archives Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 103, 523–541. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2021.06.024

Hildebrand, M. W., Host, H. H., Binder, E. F., Carpenter, B., Freedland, K. E., Morrow-Howell, N., et al. (2012). Measuring Treatment Fidelity in a Rehabilitation Intervention Study. Am. J. Phys. Med. rehabilitation/Association Acad. Physiatrists 91, 715–724. doi:10.1097/phm.0b013e31824ad462

Hochstenbach, J., Mulder, T., van Limbeek, J., Donders, R., and Schoonderwaldt, H. (1998). Cognitive Decline Following Stroke: A Comprehensive Study of Cognitive Decline Following Stroke*. J. Clin. Exp. neuropsychology 20, 503–517. doi:10.1076/jcen.20.4.503.1471

Huang, X., Naghdy, F., Du, H., Naghdy, G., and Murray, G. (2018). Design of Adaptive Control and Virtual Reality-Based Fine Hand Motion Rehabilitation System and its Effects in Subacute Stroke Patients. Comput. Methods Biomechanics Biomed. Eng. Imaging & Vis. 6, 678–686. doi:10.1080/21681163.2017.1343687

Jacucci, G., Fairclough, S., and Solovey, E. T. (2015). Physiological Computing. Computer 48, 12–16. doi:10.1109/mc.2015.291

Juliano, J. M., Spicer, R. P., Vourvopoulos, A., Lefebvre, S., Jann, K., Ard, T., et al. (2020). Embodiment is Related to Better Performance on an Immersive Brain Computer Interface in Head-Mounted Virtual Reality: A Pilot Study. Sensors 20, 1204. doi:10.3390/s20041204

Jurewicz, K., Paluch, K., Kublik, E., Rogala, J., Mikicin, M., and Wróbel, A. (2018). Eeg-Neurofeedback Training of Beta Band (12–22 Hz) Affects Alpha and Beta Frequencies – A Controlled Study of A Healthy Population. Neuropsychologia 108, 13–24. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.11.021

Kamiński, J., Brzezicka, A., Gola, M., and Wróbel, A. (2012). β Band Oscillations Engagement in Human Alertness Process. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 85, 125–128. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.11.006

Kennedy, R. S., Lane, N. E., Berbaum, K. S., and Lilienthal, M. G. (1993). Simulator Sickness Questionnaire: An Enhanced Method for Quantifying Simulator Sickness. Int. J. Aviat. Psychol. 3, 203–220. doi:10.1207/s15327108ijap0303_3

Khanna, P., and Carmena, J. M. (2015). Neural Oscillations: Beta Band Activity across Motor Networks. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 32, 60–67. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2014.11.010

Kılıç, A., Brown, A., Aras, I., Hui, R., Hare, J., Hughes, L. D., et al. (2021). Using Virtual Technology for Fear of Medical Procedures: a Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Virtual Reality-Based Interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 55, 1062–1079. doi:10.1093/abm/kaab016

Kim, M., Jeon, C., and Kim, J. (2017). A Study on Immersion and Presence of a Portable Hand Haptic System for Immersive Virtual Reality. Sensors 17, 1141. doi:10.3390/s17051141

Kleim, J. A., and Jones, T. A. (2008). Principles of Experience-dependent Neural Plasticity: Implications for Rehabilitation after Brain Damage. J Speech Lang Hear Res. New York, NY: American Speech‐Language‐Hearing Association (ASHA).

Kristensen, H. K., Tistad, M., Koch, L. v., and Ytterberg, C. (2016). The Importance of Patient Involvement in Stroke Rehabilitation. Plos one 11, e0157149. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157149

Kritikos, J., Zoitaki, C., Tzannetos, G., Mehmeti, A., Douloudi, M., Nikolaou, G., et al. (2020). Comparison between Full Body Motion Recognition Camera Interaction and Hand Controllers Interaction Used in Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for Acrophobia. Sensors 20, 1244. doi:10.3390/s20051244

Krokos, E., and Varshney, A. (2021). Quantifying VR Cybersickness Using EEG. Virtual Real. 26, 77–89. doi:10.1007/s10055-021-00517-2

Kumru, H., Albu, S., Pelayo, R., Rothwell, J., Opisso, E., Leon, D., et al. (2016). Motor Cortex Plasticity during Unilateral Finger Movement with Mirror Visual Feedback. Neural Plast. 2016, 8. doi:10.1155/2016/6087896

Lee, K. B., Lim, S. H., Kim, K. H., Kim, K. J., Kim, Y. R., Chang, W. N., et al. (2015). Six-Month Functional Recovery of Stroke Patients. Int. J. rehabilitation Res. Zeitschrift fur Rehabilitationsforschung. Revue Int. de recherches de readaptation 38, 173–180. doi:10.1097/mrr.0000000000000108

Levin, M. F., Snir, O., Liebermann, D. G., Weingarden, H., and Weiss, P. L. (2012). Virtual Reality versus Conventional Treatment of Reaching Ability in Chronic Stroke: Clinical Feasibility Study. Neurol. Ther. 1, 3–15. doi:10.1007/s40120-012-0003-9

Li, M., Chen, J., He, G., Cui, L., Chen, C., Secco, E. L., et al. (2021). Attention Enhancement for Exoskeleton-Assisted Hand Rehabilitation Using Fingertip Haptic Stimulation. Front. Robotics AI 8, 144. doi:10.3389/frobt.2021.602091

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., et al. (2009). The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies that Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 62, e1–e34. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006

Lin, C.-T., Albertson, G. A., Schilling, L. M., Cyran, E. M., Anderson, S. N., Ware, L., et al. (2001). Is Patients' Perception of Time Spent With the Physician a Determinant of Ambulatory Patient Satisfaction? Arch. Intern Med. 161, 1437–1442. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.11.1437

Lin, J.-H., Hsueh, I.-P., Sheu, C.-F., and Hsieh, C.-L. (2004). Psychometric Properties of the Sensory Scale of the Fugl-Meyer Assessment in Stroke Patients. Clin. Rehabil. 18, 391–397. doi:10.1191/0269215504cr737oa

Lindsay, M. P., Norrving, B., Sacco, R. L., Brainin, M., Hacke, W., Martins, S., et al. (2019). World Stroke Organization (WSO): Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2019. Tech. Rep. London, England: SAGE Publications Sage UK.

Longobardi, Y., Parrilla, C., Di Cintio, G., De Corso, E., Marenda, M. E., Mari, G., et al. (2020). Olfactory Perception Rehabilitation after Total Laryngectomy (OPRAT): Proposal of a New Protocol Based on Training of Sensory Perception Skills. Berlin, Germany: European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 1–11.

Lupu, R. G., Irimia, D. C., Ungureanu, F., Poboroniuc, M. S., and Moldoveanu, A. (2018). BCI and FES Based Therapy for Stroke Rehabilitation Using VR Facilities. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput 2018, 8. doi:10.1155/2018/4798359

Magosso, E., De Crescenzio, F., Ricci, G., Piastra, S., and Ursino, M. (2019). EEG Alpha Power Is Modulated by Attentional Changes during Cognitive Tasks and Virtual Reality Immersion. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2019, 18. doi:10.1155/2019/7051079

Marin-Pardo, O., Laine, C. M., Rennie, M., Ito, K. L., Finley, J., and Liew, S.-L. (2020). Virtual Reality Muscle–Computer Interface for Neurorehabilitation in Chronic Stroke: A Pilot Study. Sensors 20, 3754. doi:10.3390/s20133754

Miller, A. E. J., MacDougall, J. D., Tarnopolsky, M. A., and Sale, D. G. (1993). Gender Differences in Strength and Muscle Fiber Characteristics. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 66, 254–262. doi:10.1007/bf00235103

Mizuguchi, N., Nakata, H., Hayashi, T., Sakamoto, M., Muraoka, T., Uchida, Y., et al. (2013). Brain Activity during Motor Imagery of an Action with an Object: a Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Neurosci. Res. 76, 150–155. doi:10.1016/j.neures.2013.03.012

Moinnereau, M.-A., Oliveira, A., and Falk, T. H. (2020). “Saccadic Eye Movement Classification Using ExG Sensors Embedded into a Virtual Reality Headset,” in 2020 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC) (IEEE), 3494–3498. doi:10.1109/smc42975.2020.9283019

Morone, G., Cocchi, I., Paolucci, S., and Iosa, M. (2020). Robot-assisted Therapy for Arm Recovery for Stroke Patients: State of the Art and Clinical Implication. Expert Rev. Med. devices 17, 223–233. doi:10.1080/17434440.2020.1733408

Mubin, O., Alnajjar, F., Jishtu, N., Alsinglawi, B., and Al Mahmud, A. (2019). Exoskeletons With Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, and Gamification for Stroke Patients' Rehabilitation: Systematic Review. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 6, e12010. doi:10.2196/12010

Nasreddine, Z. S., Phillips, N. A., Bã©dirian, V. r., Charbonneau, S., Whitehead, V., Collin, I., et al. (2005). The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a Brief Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatrics Soc. 53, 695–699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

National Institutes of Health (2022). Study Quality Assessment Tools: Quality Assessment Tool. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (Accessed April).

Neuper, C., Schlögl, A., and Pfurtscheller, G. (1999). Enhancement of Left-Right Sensorimotor EEG Differences during Feedback-Regulated Motor Imagery. J. Clin. Neurophysiology 16, 373–382. doi:10.1097/00004691-199907000-00010

Nielsen, J., and Molich, R. (1990). “Heuristic Evaluation of User Interfaces,” in Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems, 249–256. doi:10.1145/97243.97281

Nikooyan, A. A., and Ahmed, A. A. (2015). Reward Feedback Accelerates Motor Learning. J. neurophysiology 113, 633–646. doi:10.1152/jn.00032.2014

Nissler, C., Nowak, M., Connan, M., Büttner, S., Vogel, J., Kossyk, I., et al. (2019). VITA-an Everyday Virtual Reality Setup for Prosthetics and Upper-Limb Rehabilitation. J. Neural Eng. 16, 026039. doi:10.1088/1741-2552/aaf35f

Norman, D. (2013). The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and. expanded edition. New York City, NY: Basic Books.

Papadopoulos, S., Bonaiuto, J., and Mattout, J. (2021). An Impending Paradigm Shift in Motor Imagery Based Brain-Computer Interfaces. Front. Neurosci. 15, 824759. doi:10.3389/fnins.2021.824759

Perez-Marcos, D. (2018). Virtual Reality Experiences, Embodiment, Videogames and Their Dimensions in Neurorehabilitation. J. Neuroeng Rehabil. 15, 113–118. doi:10.1186/s12984-018-0461-0

Pichiorri, F., Morone, G., Petti, M., Toppi, J., Pisotta, I., Molinari, M., et al. (2015). Brain-Computer Interface Boosts Motor Imagery Practice during Stroke Recovery. Ann. Neurol. 77, 851–865. doi:10.1002/ana.24390

Quattrocchi, G., Greenwood, R., Rothwell, J. C., Galea, J. M., and Bestmann, S. (2017). Reward and Punishment Enhance Motor Adaptation in Stroke. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 88, 730–736. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2016-314728

Rajanen, M., and Rajanen, D. (2018). “Heuristic Evaluation in Game and Gamification Development,” in Proceedings of the 2nd International GamiFIN Conference (Pori, Finland: GamiFIN 2018).

Read, T., Sanchez, C. A., and De Amicis, R. (2021). “Engagement and Time Perception in Virtual Reality,” in Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting (Los Angeles, CA): SAGE Publications Sage CA), 913–918. doi:10.1177/107118132165133765

Real, S., and Araujo, A. (2020). Ves: A Mixed-Reality System to Assist Multisensory Spatial Perception and Cognition for Blind and Visually Impaired People. Appl. Sci. 10, 523. doi:10.3390/app10020523

Resnick, B., Michael, K., Shaughnessy, M., Shim Nahm, E., Sorkin, J. D., and Macko, R. (2011). Exercise Intervention Research in Stroke: Optimizing Outcomes through Treatment Fidelity. Top. stroke rehabilitation 18, 611–619. doi:10.1310/tsr18s01-611

Richardson, M., Campbell, N., Allen, L., Meyer, M., and Teasell, R. (2016). The Stroke Impact Scale: Performance as a Quality of Life Measure in a Community-Based Stroke Rehabilitation Setting. Disabil. rehabilitation 38, 1425–1430. doi:10.3109/09638288.2015.1102337

Riva, G., Wiederhold, B. K., and Mantovani, F. (2019). Neuroscience of Virtual Reality: from Virtual Exposure to Embodied Medicine. Cyberpsychology, Behav. Soc. Netw. 22, 82–96. doi:10.1089/cyber.2017.29099.gri

Roberts, R., Callow, N., Hardy, L., Markland, D., and Bringer, J. (2008). Movement Imagery Ability: Development and Assessment of a Revised Version of the Vividness of Movement Imagery Questionnaire. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 30, 200–221. doi:10.1123/jsep.30.2.200

Rose, T., Nam, C. S., and Chen, K. B. (2018). Immersion of Virtual Reality for Rehabilitation - Review. Appl. Ergon. 69, 153–161. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2018.01.009

Ruffino, C., Papaxanthis, C., and Lebon, F. (2017). Neural Plasticity during Motor Learning with Motor Imagery Practice: Review and Perspectives. Neuroscience 341, 61–78. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.11.023

Saltin, B., and Grimby, G. (1968). Physiological Analysis of Middle-Aged and Old Former Athletes. Circulation 38, 1104–1115. doi:10.1161/01.cir.38.6.1104

Sheng, B., Zhang, Y., Meng, W., Deng, C., and Xie, S. (2016). Bilateral Robots for Upper-Limb Stroke Rehabilitation: State of the Art and Future Prospects. Med. Eng. Phys. 38, 587–606. doi:10.1016/j.medengphy.2016.04.004

Sherman, W. R., and Craig, A. B. (2003). Understanding Virtual Reality. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kauffman.

Slater, M. (2009). Place Illusion and Plausibility Can Lead to Realistic Behaviour in Immersive Virtual Environments. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 3549–3557. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0138

Stanica, I.-C., Moldoveanu, F., Portelli, G.-P., Dascalu, M.-I., Moldoveanu, A., and Ristea, M. G. (2020). Flexible Virtual Reality System for Neurorehabilitation and Quality of Life Improvement. Sensors 20, 6045. doi:10.3390/s20216045

Sun, J. H., Tan, L., and Yu, J. T. (2014). Post-stroke Cognitive Impairment: Epidemiology, Mechanisms and Management. Ann. Transl. Med. 2, 80. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.08.05

Suzuki, K., Nakamura, F., Otsuka, J., Masai, K., Itoh, Y., Sugiura, Y., et al. (2017). “Recognition and Mapping of Facial Expressions to Avatar by Embedded Photo Reflective Sensors in Head Mounted Display,” in 2017 IEEE Virtual Reality (VR) (IEEE), 177–185. doi:10.1109/vr.2017.7892245

Szczepańska-Gieracha, J., Cieślik, B., Rutkowski, S., Kiper, P., and Turolla, A. (2020). What Can Virtual Reality Offer to Stroke Patients? a Narrative Review of the Literature. NeuroRehabilitation 40, 1–12. doi:10.3233/NRE-203209

Thiele, A., and Bellgrove, M. A. (2018). Neuromodulation of Attention. Neuron 97, 769–785. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.008

Thiese, M. S. (2014). Observational and Interventional Study Design Types; an Overview. Biochem. Med. 24, 199–210. doi:10.11613/bm.2014.022

Tollár, J., Nagy, F., Csutorás, B., Prontvai, N., Nagy, Z., Török, K., et al. (2021). High Frequency and Intensity Rehabilitation in 641 Subacute Ischemic Stroke Patients. Archives Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 102, 9–18. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2020.07.012

Tondello, G. F., Kappen, D. L., Mekler, E. D., Ganaba, M., and Nacke, L. E. (2016). “Heuristic Evaluation for Gameful Design,” in Proceedings of the 2016 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play Companion Extended Abstracts, 315–323. doi:10.1145/2968120.2987729

Trombetta, M., Bazzanello Henrique, P. P., Brum, M. R., Colussi, E. L., De Marchi, A. C. B., and Rieder, R. (2017). Motion Rehab Ave 3D: A VR-Based Exergame for Post-stroke Rehabilitation. Comput. methods programs Biomed. 151, 15–20. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2017.08.008

Tufanaru, C., Munn, Z., Aromataris, E., Campbell, J., and Hopp, L. (2017). Systematic Reviews of Effectiveness. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute.

Vassiliadis, P., Derosiere, G., Dubuc, C., Lete, A., Crevecoeur, F., Hummel, F. C., et al. (2021). Reward Boosts Reinforcement-Based Motor Learning. bioRxiv 24, 16. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.102821

Vourvopoulos, A., and I Badia, S. B. (2016). Motor Priming in Virtual Reality Can Augment Motor-Imagery Training Efficacy in Restorative Brain-Computer Interaction: a Within-Subject Analysis. J. Neuroeng Rehabil. 13, 69–14. doi:10.1186/s12984-016-0173-2

Vourvopoulos, A., Jorge, C., Abreu, R., Figueiredo, P., Fernandes, J.-C., and Bermúdez i Badia, S. (2019a). Efficacy and Brain Imaging Correlates of an Immersive Motor Imagery BCI-Driven VR System for Upper Limb Motor Rehabilitation: A Clinical Case Report. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 13, 244. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2019.00244

Vourvopoulos, A., Pardo, O. M., Lefebvre, S., Neureither, M., Saldana, D., Jahng, E., et al. (2019b). Effects of a Brain-Computer Interface with Virtual Reality (VR) Neurofeedback: A Pilot Study in Chronic Stroke Patients. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 13, 210. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2019.00210

Wedoff, R., Ball, L., Wang, A., Khoo, Y. X., Lieberman, L., and Rector, K. (2019). “Virtual Showdown: An Accessible Virtual Reality Game with Scaffolds for Youth with Visual Impairments,” in Proceedings of the 2019 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 1–15.

Widmer, M., Held, J. P., Wittmann, F., Lambercy, O., Lutz, K., and Luft, A. R. (2017). Does Motivation Matter in Upper-Limb Rehabilitation after Stroke? ArmeoSenso-Reward: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 18, 580–589. doi:10.1186/s13063-017-2328-2

Witmer, B. G., Jerome, C. J., and Singer, M. J. (2005). The Factor Structure of the Presence Questionnaire. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 14, 298–312. doi:10.1162/105474605323384654

You, S. H., Jang, S. H., Kim, Y.-H., Hallett, M., Ahn, S. H., Kwon, Y.-H., et al. (2005). Virtual Reality–Induced Cortical Reorganization and Associated Locomotor Recovery in Chronic Stroke. Stroke 36, 1166–1171. doi:10.1161/01.str.0000162715.43417.91

Yozbatiran, N., Der-Yeghiaian, L., and Cramer, S. C. (2008). A Standardized Approach to Performing the Action Research Arm Test. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 22, 78–90. doi:10.1177/1545968307305353

Zeiaee, A., Soltani-Zarrin, R., Langari, R., and Tafreshi, R. (2017). “Design and Kinematic Analysis of a Novel Upper Limb Exoskeleton for Rehabilitation of Stroke Patients,” in 2017 IEEE Int Conf Rehabil Robot, 2017 (IEEE), 759–764. doi:10.1109/ICORR.2017.8009339

Zhang, X., Xu, G., Xie, J., Li, M., Pei, W., and Zhang, J. (2015). “An EEG-Driven Lower Limb Rehabilitation Training System for Active and Passive Co-Stimulation,” in 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) (IEEE), 4582–4585. doi:10.1109/embc.2015.7319414

Keywords: stroke rehabilitation, head-mounted display (HMD), immersive virtual reality, physiological computing, feedback

Citation: Amini Gougeh R and Falk TH (2022) Head-Mounted Display-Based Virtual Reality and Physiological Computing for Stroke Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. Front. Virtual Real. 3:889271. doi: 10.3389/frvir.2022.889271

Received: 04 March 2022; Accepted: 15 April 2022;

Published: 03 May 2022.

Edited by:

Benjamin J. Li, Nanyang Technological University, SingaporeReviewed by:

Xu Xuanhui, University College Dublin, IrelandAngelica G. Thompson Butel, Australian Catholic University, Australia

Nadinne Roman, Transilvania University of Brașov, Romania

Copyright © 2022 Amini Gougeh and Falk. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Reza Amini Gougeh, YW1pbmkuZ291Z2VoLnJlemFAaW5ycy5jYQ==

Reza Amini Gougeh

Reza Amini Gougeh Tiago H. Falk

Tiago H. Falk