- Department of Geography and Rural Planning, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran

Background: This study examines the participation of the rural poor in tourism activities without external support in selected Iranian villages, addressing the research gap on their direct involvement in formal and informal tourism businesses.

Methodology: A qualitative approach was employed, utilizing face-to-face semi-structured interviews with 65 participants from three villages near Turan National Park in Shahrud, Iran. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Findings: Results indicate that the rural poor actively engage in tourism. This participation encompasses seeking formal employment in tourism facilities, engaging in informal activities, and acquiring relevant knowledge and skills. The study highlights the significant potential of informal tourism businesses in increasing opportunities for low-income individuals, despite challenges such as lack of capital and legal protection.

Conclusion: The findings demonstrate that even without external assistance, the rural poor find ways to participate in and benefit from tourism activities. Both formal and informal tourism activities play important roles in poverty alleviation efforts. The study emphasizes the need for targeted interventions to support the rural poor's participation in the tourism sector and harness tourism's potential for poverty reduction in rural areas.

1 Introduction

Tourism is crucial in driving economic growth globally by offering opportunities for job creation, infrastructure development, and foreign exchange earnings (Anderson, 2015; Blake et al., 2008). However, the distribution of tourism benefits is often inequitable, with the affluent reaping a larger share of the rewards while people experiencing poverty are left behind (Akyeampong, 2011; Wang and Dong, 2022; Li et al., 2022). To address this issue, there is a growing interest in exploring how tourism can be leveraged to reduce poverty and promote sustainable development, with a particular emphasis on the participation of the poor in tourism activities (Torabi et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022). Despite this interest, there is a dearth of empirical research on how people experiencing poverty participate in tourism activities, the pathways they take to access the tourism sector, the benefits they accrue, and the challenges they confront in this domain (Butler et al., 2013; Scheyvens, 2012; Monterrubio, 2022).

Previous studies have identified various factors that prevent people experiencing poverty from participating in tourism activities, including lack of skills, education, capital, and access to markets and information (Akyeampong, 2011; Harrison and Pratt, 2019; Harrison and Schipani, 2007b; Holden et al., 2011; Mitchell and Ashley, 2009). Studies also show that poor individuals prefer informal tourism activities, such as handicrafts, informal guidance, and homestays, over formal tourism activities like hotels and restaurants (Hall, 2007; Harrison, 2008; Torabi et al., 2019). However, informal tourism activities pose several challenges, including limited access to formal markets, lack of legal protection, and low-income potential (Truong, 2018; Winter and Kim, 2021).

Scholars have emphasized encouraging informal sector participation in tourism to enhance poverty reduction and wealth redistribution (Winter and Kim, 2021; Mwesiumo et al., 2021; Monterrubio, 2022). Despite recognizing this importance, limited research comprehensively examines the impact of poor participation in formal and informal tourism markets on poverty reduction in developing countries (Saayman et al., 2020). Poor individuals are often marginalized from formal economic and tourism policy and planning due to their dependence on the illegal informal sector outside the scope of government policies and regulations (Winter and Kim, 2021; Harrison, 2008). As a result, their potential contribution to poverty reduction through tourism is often overlooked (Monterrubio, 2022). Therefore, more research is necessary to explore the informal tourism market's impact on poverty reduction in developing countries and recognize its potential as a vital contributor to the tourism industry and wider economy (Saayman et al., 2020). Such research can inform policies and initiatives that promote inclusive growth, empowering poor and marginalized communities to participate in the tourism industry (Truong, 2018; Nyahunzvi, 2015).

This research addresses two critical gaps in the existing literature on tourism and poverty reduction. First, it seeks to investigate how the rural poor participate in tourism activities without external assistance from government or non-governmental organizations. While previous studies have highlighted the importance of external support in facilitating the participation of people experiencing poverty in tourism (Akyeampong, 2011; Holden et al., 2011). Limited research exists on how people experiencing poverty engage in tourism activities without such support. By examining the experiences of the rural poor in selected villages in Shahrud, Iran, this study provides valuable insights into the strategies employed by the poor to overcome barriers and participate in tourism activities. These findings can inform the development of more effective policies and interventions to enhance poverty reduction through tourism.

Second, this research examines the impact of poor participation in formal and informal tourism markets on reducing poverty. Existing literature has predominantly focused on the role of formal tourism activities in poverty alleviation (Harrison and Schipani, 2007b; Spenceley and Meyer, 2012), with limited attention given to the contribution of informal tourism activities. However, the informal sector plays a significant role in the economies of developing countries, particularly in rural areas (Saayman et al., 2020; Truong, 2018). By investigating the participation of people experiencing poverty in both formal and informal tourism markets, this study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of how tourism can be used as a tool for poverty reduction and promoting inclusive growth. The findings of this research can help policymakers and practitioners develop more targeted interventions that recognize the importance of formal and informal tourism activities in alleviating poverty and promoting sustainable development in rural areas.

2 Literature

For tourism to fully realize its potential for poverty reduction and sustainable development, it must be developed sustainably and responsibly (Dossou et al., 2023; Liu and Yu, 2022). This requires adopting policies and practices that promote sustainable tourism, such as ecotourism, cultural tourism, and community-based tourism (Torabi et al., 2021; Maingi, 2021). Local communities must also be involved in the planning, development, and management of tourism activities to ensure that the benefits of tourism are shared equitably (Zeng, 2018; Medina-Muñoz et al., 2016). Tourism can play a significant role in reducing poverty and achieving the SDGs (Maingi, 2021). However, achieving this will require a concerted effort from all stakeholders to promote sustainable tourism policies and practices that benefit local communities and ensure the sustainable use of natural resources.

The literature review suggests that tourism has the potential to alleviate poverty in developing countries through the implementation of pro-poor tourism initiatives (Kimaro and Saarinen, 2019). These initiatives include strategies such as micro-enterprise creation, community-based tourism, education, and responsible tourism practices (Harrison and Schipani, 2007b; Moli, 2011). By increasing the participation of people experiencing poverty in tourism activities, these strategies can create job opportunities and promote social and economic benefits for local communities (Chettiparamb and Kokkranikal, 2012; Spenceley and Meyer, 2012; Torres et al., 2011). Micro-enterprises can effectively engage people experiencing poverty in tourism activities by providing goods and services to tourists (Chettiparamb and Kokkranikal, 2012; Moli, 2011; Mudzengi et al., 2018). However, a lack of access to capital and financial services can hinder the creation and sustainability of micro-enterprises (Ma et al., 2020; Goodwin, 2007). Therefore, efforts should be made to provide access to credit, savings, and insurance to enable people experiencing poverty to benefit from these schemes (Adiyia and Vanneste, 2018; Ashley and Roe, 2002; Azqueta and Montoya, 2011).

Community-based tourism involves the participation of local communities in developing and managing tourism activities (Chettiparamb and Kokkranikal, 2012; Harrison and Schipani, 2007a; Poyya Moli, 2013). This approach can promote the sustainable development of tourism, preserve local culture and environment, and provide economic and social benefits to the local community (Medina-Muñoz et al., 2016). However, the lack of infrastructure and basic services in many tourism destinations can limit the participation of people experiencing poverty in community-based tourism initiatives (Adie, 2019; Akyeampong, 2011; Azqueta and Montoya, 2011; Babalola and Ajekigbe, 2007). Training programs can provide people experiencing poverty with the necessary skills and knowledge to participate in tourism activities, increase their employability, and improve their income-generating capacity (Adie, 2019; Truong et al., 2016; Folarin and Adeniyi, 2020).

Responsible tourism practices can promote sustainable tourism development, increase tourism's social and economic benefits for people experiencing poverty, and minimize negative impacts on the environment and local communities (Adie, 2019; Zhao and Brent Ritchie, 2007; Zhu et al., 2022). Overall, pro-poor tourism initiatives have the potential to contribute significantly to poverty reduction and sustainable development (Marquardt, 2018). However, these initiatives require careful planning, community involvement, and stakeholder engagement to succeed (Adie, 2019; Zeng, 2018; Zeng and Ryan, 2012). Successful pro-poor tourism initiatives, such as the Community-Based Tourism Project in Thailand, demonstrate the potential of tourism as a tool for poverty reduction and sustainable development (Sudsawasd et al., 2022; Theerapappisit, 2009). Finally, if tourism is developed and managed sustainably and equitably, it can be a powerful driver of poverty reduction. Pro-poor tourism initiatives prioritizing local communities' needs and aspirations can help ensure that tourism benefits people experiencing poverty and promotes sustainable development (Zeng, 2018; Peeters, 2012). However, there is a need for more research to determine the most effective way to design and implement pro-poor tourism projects in different contexts and to address the challenges that can hinder their success (Torabi et al., 2019). Although the statement in the original text about rural communities struggling to engage in tourism-related activities is true, it does not necessarily contradict the information presented in the literature review (Li et al., 2022; Schilcher, 2007). The lack of targeted interventions and support may be the reason for their struggle, which emphasizes the importance of implementing pro-poor tourism initiatives (Adie, 2019; Chok et al., 2007; Croes, 2014).

2.1 Ways of participation of the poor in tourism activities

Tourism is often considered a catalyst for economic development and poverty reduction in developing countries (Toerien, 2020). However, its impact on people with low incomes is not straightforward, and it depends on how the benefits and costs of tourism are distributed (Saito et al., 2018; Torabi et al., 2019). The literature on pro-poor tourism suggests that tourism can be pro-poor if it creates opportunities for people experiencing poverty to participate in tourism activities and if the benefits of tourism are distributed in a way that benefits people experiencing poverty (Sudsawasd et al., 2022). In this literature review, we examine the experiences of people experiencing poverty in participating in tourism activities, focusing on the three main channels through which the benefits or costs of tourism can be transferred to people experiencing poverty (Vanegas Sr et al., 2015; Soliman, 2015).

Direct impacts of tourism on people experiencing poverty include income from work and other forms of income from the tourism sector, such as jobs in hotels and restaurants or taxi companies (Saito et al., 2018; Medina-Muñoz et al., 2016; Spenceley and Goodwin, 2007). Several studies have shown that tourism can create employment opportunities for people experiencing poverty, especially in the informal sector (Akyeampong, 2011; Scheyvens and Russell, 2012). For example, in Nepal, the tourism sector has provided income-generating opportunities for people experiencing poverty by establishing homestays and community-based tourism initiatives (Pillay and Rogerson, 2013; Sanches-Pereira et al., 2017; Rogerson, 2014b). Similarly, in South Africa, the tourism sector has created employment opportunities for people experiencing poverty by establishing small businesses such as tour guides, craft markets, and catering services (Rogerson, 2006, 2002).

Non-work income includes community income from things like rentals. For example, in Jamaica, tourism has provided income-generating opportunities for people experiencing poverty by renting tourist rooms, villas, and apartments (Pillay and Rogerson, 2013; Rogerson, 2012, 2014a). However, the literature also highlights some challenges associated with the direct impacts of tourism on people experiencing poverty. For example, in some cases, the jobs created by the tourism sector may be low-paying, low-skilled, and seasonal, which may limit their impact on poverty reduction (Torabi et al., 2021; Ashley and Mitchell, 2009). Additionally, some studies suggest that the jobs created by the tourism sector may be concentrated in urban areas, which may limit their impact on rural poverty reduction (Nsanzya and Saarinen, 2022).

Secondary effects of tourism on people experiencing poverty come from non-tourism sectors that originate from the activity of tourists, such as industrialists, construction workers, and farmers (Manwa and Manwa, 2014). Positive effects arise when employees in the tourism sector spend their income locally, creating additional income for poor households (Torabi et al., 2021). For example, in Kenya, the tourism sector has created employment opportunities for farmers by supplying food to hotels and restaurants (Kimaro and Saarinen, 2019; Maingi, 2021). Similarly, in Mexico, the tourism sector has created employment opportunities for construction workers through the construction of hotels and other tourist facilities (Monterrubio, 2022).

However, the literature also suggests that the secondary effects of tourism on people experiencing poverty may not always be positive (Manwa and Manwa, 2014). For example, in some cases, the tourism sector may drive up the cost of living, making it difficult for poor households to access essential goods and services (Liu and Yu, 2022; Zeng, 2018; Torabi et al., 2021). Additionally, the tourism sector may compete with other sectors for resources such as water and land, which may have negative consequences for poor households that rely on these resources for their livelihoods (Saayman et al., 2020; Rogerson, 2002).

Dynamic effects include long-term changes in the economy and growth patterns, as well as environmental effects such as the erosion of natural resources resulting from the development and expansion of tourism (Ashley and Mitchell, 2009). For example, in Thailand, the expansion of the tourism sector has led to environmental degradation, which has had negative consequences for the livelihoods of poor households that rely on natural resources for their livelihoods (Intapan et al., 2021; Sudsawasd et al., 2022; Theerapappisit, 2009). Similarly, in the Maldives, the expansion of the tourism sector has led to the displacement of poor households from their land, negatively affecting their livelihood (Scheyvens, 2012; Ashley and Mitchell, 2009).

2.2 The formal and informal market for the poor

The informal economy encompasses economic activities outside the purview of state regulation (Monterrubio, 2022). This concept was first identified in the early 1940's when rural-urban migration created a surplus of labor and left migrants excluded from the modern urban economy, a phenomenon referred to as “marginality.” Hart (1973) study of migrants' economic activities in Accra, Ghana, led to the introduction of the term “informal economy” to describe their activities in contrast to the “formal” economy of salaried employment and organized business. Since then, scholars have extensively researched informal work, exploring its dynamics and relationship with the formal sector (Truong et al., 2020). Portes and Sassen-Koob (1987) suggest that higher incomes in the informal sector led to a voluntary shift from the formal sector. Teltscher (1994) observes that small vendors' wellbeing depends on national and international networks, from mere survival to enterprise ownership. De León (1996) challenges the ILO-PREALC's exclusion of the informal sector from the formal sector and highlights the informal sector's cultural dimensions and internal dynamics. The author acknowledges the critical role of some informal enterprises in the development process while recognizing the existence of a vicious circle of poverty and informal work (Monterrubio, 2022).

Regarding the tourism industry, Rakowski (1994) argues that the relationship between informality and poverty is complex and not all informal workers are poor. Beccaria and Groisman (2008) suggest that poverty is not limited to families engaged in informal work, and Nazier and Ramadan (2015) claim that informal work may be a choice rather than a result of poverty. In contrast, Devicienti et al. (2010) Argue that income difficulties force household heads to accept informal work. Amuedo-Dorantes (2004) finds that holding an informal job increases the likelihood of becoming poor, and low-income families are more likely to have members working in the informal sector.

Further research has highlighted the importance of informal work in income generation in Latin America (Croes, 2014). Truong et al. (2022) argue that the informal sector is not a residual activity but an integral part of the economy. De Soto (1989) it stresses the crucial role of property rights in the informal sector's development, which leads to formalization and more significant economic growth. Schneider and Enste (2000) emphasize the importance of reducing the regulatory burden on the informal sector to increase its efficiency and productivity, ultimately leading to economic growth. Therefore, policymakers and researchers interested in promoting inclusive economic growth and poverty reduction must understand the dynamics of informal work and its relationship with the formal sector in the tourism industry.

3 Selected villages

This study focuses on three villages near Turan National Park: Abr, Qaleh-ye Bala, and Reza Abad. These villages were deliberately chosen because they have become increasingly popular tourist destinations over the past 8 years (Figure 1).

Turan National Park, the world's second most significant biosphere reserve, is a treasure trove of unique natural attractions. Its rich variety of plant and animal life, with over 250 species of mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians, is a sight to behold. The park's wildlife, including the Asiatic cheetah and Persian zebra, have sparked the growth of tourism-related businesses in the surrounding rural areas. This growth is evident in the increased sales of local crafts and agricultural products, and the establishment of eco-lodges and tour guide services. The study, focusing on these villages, aims to delve into the impact of tourism development on the livelihoods of the rural poor and their involvement in tourism activities. The decision to conduct research in Abr, Qaleh-ye Bala, and Reza Abad villages is further strengthened by their location within Shahrud County, a region known for its diverse climatic conditions. This county, positioned 390 kilometers from the capital city and at 1,400 m, is nicknamed the “land of five climatic conditions” due to its distinct climate zones, ranging from hot and humid in the north to hot and dry in the south and center. The county's population, according to the 2016 census, is 218,665, with 45,000 people residing in rural areas (Torabi et al., 2021). The villages in Shahrud County have become tourist destinations in rural Iran, attracting many visitors annually.

Furthermore, Shahrud's strategic location on the international Tehran-Mashhad corridor allows it to host an annual population of 20 million tourists traveling to Mashhad (Ghaderi et al., 2018). This influx of tourists has prompted authorities to develop the villages and accommodate more visitors in rural areas. By focusing on these villages, the study aims to capture the dynamics of tourism development in a region experiencing rapid growth and transformation and to examine how the rural poor navigate and participate in this evolving landscape.

4 Methodology

This study employed a qualitative approach. Data were collected through face-to-face semi-structured interviews with participants in selected villages. This method allowed researchers to understand participants' experiences and perspectives regarding their involvement in tourism activities. The collected data were then analyzed using thematic analysis based on the method proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006). This analytical approach enabled researchers to identify key patterns and themes in the data, providing a comprehensive understanding of how poor individuals participate in tourism activities and the impact of this participation on poverty reduction.

4.1 Sampling and participants

To achieve the research objectives of investigating how people experiencing poverty participate in tourism activities without external assistance and examining the impact of their participation in both formal and informal tourism markets on poverty reduction, a qualitative approach was adopted for data collection and sampling. Purposive sampling was employed to select participants who could provide rich and relevant information based on their direct or indirect involvement in tourism-related activities in the selected villages of Abr, Qale-ye Bala, and Reza Abad. This non-probability sampling technique allows for intentionally selecting participants with specific characteristics or experiences that align with the research objectives. By targeting individuals who had been engaged in tourism-related jobs for 2–8 years prior to the study, the researchers ensured that the participants had sufficient knowledge and experience to offer valuable insights into the participation of people with low incomes in tourism activities.

To further enhance the depth and breadth of the data, snowball sampling was used in conjunction with purposive sampling. Snowball sampling involves asking initial participants to recommend others who meet the study's selection criteria. This technique is beneficial when investigating hard-to-reach or marginalized populations, such as the poor in rural areas. By leveraging the participants' social networks, the researchers were able to identify and recruit additional participants who could provide diverse perspectives on the topic.

Semi-structured individual interviews were conducted as the primary method of data collection. These interviews allowed for a balance between structure and flexibility, enabling the researchers to explore predetermined topics while also providing opportunities for participants to share their unique experiences and insights (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The interviews were guided by a set of open-ended questions that focused on the participants' involvement in tourism-related activities, the challenges and opportunities they encountered, and their perceptions of tourism's impact on poverty alleviation. The semi-structured nature of the interviews facilitated the emergence of rich, detailed narratives that could be analyzed to uncover patterns and themes relevant to the research objectives.

The sample size for the study was determined based on the principles of theoretical saturation and information usefulness threshold. Theoretical saturation refers to the point at which no new themes or insights emerge from the data, indicating that further data collection is unlikely to yield additional theoretical developments (Ghaderi et al., 2023). The information usefulness threshold, on the other hand, is the point at which the collected data is deemed sufficient to address the research objectives and provide meaningful insights.

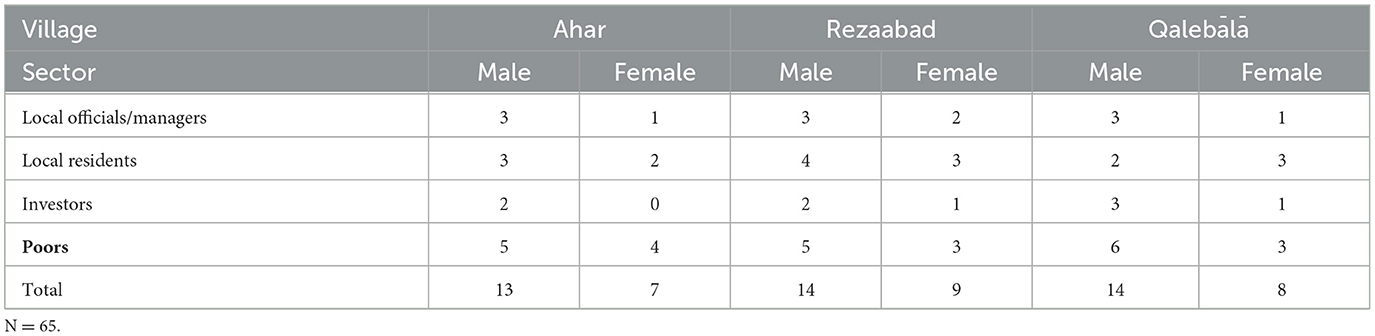

By continuously assessing the data during the collection and analysis process, the researchers could identify when saturation and information usefulness had been achieved, ensuring that the sample size was adequate to support the study's conclusions and recommendations. Table 1 presents the profile of the participants, categorized by village, sector, and gender. Sixty-five participants were interviewed, with a balanced representation across the three selected villages (Abr, Qale-ye Bala, and Reza Abad). The sample included participants from various sectors, including local officials/managers, residents, investors, and the poor. Including both male and female participants, they ensured that gender-specific experiences and perspectives were captured in the study.

4.2 Data analysis

Thematic analysis, a widely used qualitative data analysis method, was employed to systematically examine the interview data and identify patterns and themes relevant to the research objectives. The data analysis process began with the verbatim transcription of the recorded interviews and a thorough review of the interview notes to ensure accuracy, reliability, and familiarization with the content. The researchers then employed the immersion technique, actively searching for and noting initial ideas and considering the relationships between different aspects of the data. The software program MAXQDA was used to facilitate the development of the thematic framework, allowing for efficient organization and management of the data. Logical and intuitive thinking, guided by the research questions, was used to judge the importance of issues, the meaning of participants' experiences, and the implicit connections between ideas. Open coding was used to break the data into discrete parts, assigning codes to segments that captured the essence of the participants' experiences and perspectives. Charting was employed to visualize the data and explore relationships between codes, while semantic and conceptual relationships were used to group codes into broader categories or themes.

To ensure the validity of the research, transcribed interviews were sent back to participants for review (member checking), allowing participants to verify the accurate representation of their experiences and perspectives. However, only one-third of the participants provided additional feedback, which was considered during the analysis. The emergent thematic structure and codes used during the analysis were carefully designed to capture the social distribution of the issues raised and to reflect the subjectivities of the experiences shared by the participants, ensuring that the analysis remained grounded in the participants' lived experiences and that the findings were representative of the diverse perspectives and experiences of people experiencing poverty about their participation in tourism activities. By following this systematic and rigorous approach to data analysis, the researchers were able to identify key themes and patterns that shed light on how people experiencing poverty participate in tourism activities without external assistance, the challenges and opportunities they face, and the impact of their participation on poverty reduction, ultimately informing the development of recommendations for policy and practice aimed at supporting the participation of the poor in tourism and maximizing the potential of tourism as a tool for poverty alleviation.

5 Results

5.1 Learning and skill improvement among the rural poor

This study reveals that poor individuals in selected villages have made direct efforts to improve their skills in tourism-related activities without the aid of specific government or non-governmental organizations. These efforts can be classified into two categories: those seeking training to enhance their job opportunities and those who learn on the job and eventually integrate into tourism businesses. Despite educational challenges, the poor in the study area have sought to increase their skills through various means, including participating in classes organized by the Organization of Cultural Heritage and Natural Resources and non-governmental organizations. These classes cover diverse aspects of tourism, such as eco-lodge establishment and handicraft preparation, and have been received positively, with applicants still coming after 7 years. Both genders are encouraged to participate, and the rural poor face no discrimination. Although attending training courses held in provincial or city centers may prove difficult for some, those who are determined to find ways to participate and improve their skills. Despite high costs, the rural poor are still committed to attending these classes. Our findings demonstrate that even without special attention from tourism organizations and institutions for education, the rural poor have taken it upon themselves to increase their knowledge.

Moreover, the study reveals that some individuals work in activities where they lack skills but attempt to improve their situation by learning from their surroundings. For instance, a worker at an eco-lodge started as a cleaner and cook's assistant but now serves as the lodge's caretaker and guides tourists on village tours. However, people working in informal jobs have fewer training opportunities than formal ones. Although their financial and employment situation may have improved, they encountered difficulties in improving their skills in matters related to the Kurdish nature. This disparity underscores the need to offer equal opportunities for learning and training to both formal and informal job holders. Comparing the findings of this study to the existing literature on learning and skill improvement, it is evident that investment in education and training can assist poor people in enhancing their economic status (Dada et al., 2022; Karim et al., 2020; Folarin and Adeniyi, 2020; Torabi et al., 2019). Other studies have indicated that access to education and training can lead to higher income, better job prospects, and improved health outcomes (Dossou et al., 2023; Qin et al., 2022; Gohori et al., 2022). For instance, a study in rural India found that individuals with vocational training were more likely to be employed and earn higher wages (Biswas, 2014; Chettiparamb and Kokkranikal, 2012).

Furthermore, the literature documents the significance of training in the tourism industry, which is labor-intensive and necessitates a diverse set of skills, including language skills, cultural awareness, and customer service (Dossou et al., 2023; Toerien, 2020; Zeng and Wang, 2019; Truong, 2018). A study conducted in Egypt revealed that training tourism industry employees leads to greater job satisfaction, enhanced service quality, and improved financial performance for tourism businesses (Soliman, 2015; Nazier and Ramadan, 2015).

Therefore, the results of this study demonstrate that providing educational opportunities is essential in empowering people to enhance their economic status, particularly in tourism-related activities. These findings align with existing literature, which emphasizes the importance of education and training in improving economic outcomes, particularly in the tourism industry (Dossou et al., 2023; Nguyen, 2019; Truong, 2018; Saayman and Giampiccoli, 2016). However, the study's results contrast with existing literature, indicating that rural poor individuals can strive to improve their skills even without support from empowerment and tourism programs and can seize opportunities that arise to increase their income. Although many of them may not achieve their objectives, the study's results demonstrate that many have been able to enhance their skills despite numerous challenges and minimal government support and engage in tourism-related activities.

5.2 Participation of people experiencing poverty in the formal sector of tourism

The findings of this research indicate that poor rural communities are actively trying to participate in formal tourism-related businesses and take advantage of the economic opportunities this industry offers. This is consistent with previous studies on the impact of tourism on rural communities, which have shown that tourism can generate income and employment opportunities, especially for disadvantaged groups such as people experiencing poverty (Dada et al., 2022; Qin et al., 2022; Gohori et al., 2022). One of the strategies used by the rural poor in this research to benefit from tourism was the creation of a toll station, which generated income for the villagers and created jobs for nine people. The village head emphasized that the work was legal and was done with the cooperation of the city's natural resources department. This finding is consistent with previous studies highlighting the importance of partnership and collaboration between different stakeholders in the tourism industry to ensure sustainable tourism development (Buckley, 2012; Hall, 2008). In fact, by increasing their skills, they can find work for themselves in public organizations such as rural municipalities. In response to how he was able to work in these organizations, one of the people answered: “In order to get hired, we had to acquire minimal skills related to collecting fees, and I tried to learn these skills to make myself qualified for employment. Now, I can collect entry fees from any car that wants to enter the forest and register it in a book.” The growth of ecotourism lodges was another strategy used by the rural poor in this study to benefit from tourism. Many residents, including people experiencing poverty, worked as eco-lodge operators, local guides, and producers, while others could indirectly benefit from the growth of eco-lodges. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have emphasized the potential of ecotourism to create employment opportunities and generate income for local communities (Adiyia and Vanneste, 2018; Ashley and Roe, 2002; Babalola and Ajekigbe, 2007).

The participation of low-income people in tourism-related activities was another significant finding from this research. Some people with low incomes could increase the added value of their products by creating shops and selling rural products to tourists. This is consistent with previous studies highlighting the importance of involving local communities in tourism activities and providing opportunities for participation in the tourism value chain (Sharpley and Telfer, 2014; Babalola and Ajekigbe, 2007). Overall, the findings of this study show that tourism can provide economic opportunities to poor rural communities and that these communities are actively trying to participate in formal jobs related to the industry. However, it is essential to note that the benefits of tourism are not always equally distributed, and there is often an imbalance of power between different stakeholders in the industry (Buckley, 2012). Therefore, ensuring that tourism development is sustainable and equitable and that local communities can participate in decision-making processes and benefit from the industry fairly and inclusively is essential. For example, tourism can change local culture and social dynamics, environmental degradation, and biodiversity loss (Ceballos-Lascurain, 1996). Therefore, it is essential to implement responsible tourism practices that minimize negative impacts and promote sustainable tourism development (Torabi et al., 2021). However, our findings show that without planning, tourism can employ people experiencing poverty through formal businesses.

Consequently, this study provides valuable insights into the direct ways in which poor rural communities in Iran are benefiting from tourism. The findings demonstrate that tourism offers economic opportunities for disadvantaged groups even without the support of organizations and NGOs. Local communities actively participate in formal businesses related to the industry. However, to ensure sustainable and fair tourism development, it is necessary to implement programs that enable local communities to participate in decision-making processes and benefit from the industry in an inclusive manner (Truong et al., 2020). It is important to note that participating in informal business may not be a viable solution for long-term economic growth.

5.3 Participation of people experiencing poverty in the informal sector of tourism

This study proves that despite facing financial constraints, people experiencing poverty in selected villages express interest in tourism development to improve their economic status. Due to their inability to invest in formal businesses or acquire specific skills, informal activities such as selling agricultural and livestock products to tourists are common. Although not accepted by the organization, Hawking has emerged as a popular option. In response to the question of how much these peddlers have been able to help improve the livelihoods of poor people, one rural manager answered: “Peddling does not require much capital and has been able to employ several poor people. As government representatives, we have supported these individuals and also attempted to organize these activities in appropriate places.”

One tourism activist from the poor class found a unique way to offer tours by using his donkey to navigate the village's narrow streets. He generated enough income to support his family and even convert his home into housing in the future by charging tourists for each tour. Handicraft production, particularly for women who could work from home, was another informal activity that allowed people experiencing poverty to profit. Residents also rented out their homes or rooms to tourists, especially when ecotourism lodges were at total capacity. “In this regard, one of the poor individuals interviewed explained their experience of accommodating tourists, stating,” “At first, we did not like to give our room to tourists. However, I saw that some people started doing this, and their income increased. So, we also started renting out our houses to tourists. This is a very good job. If we have a guest, we can earn 200,000–300,000 tomans daily.”

These findings align with the literature on the role of informal activities in supporting the livelihoods of people experiencing poverty in developing countries, serving as an essential source of income in rural areas with limited formal employment opportunities (Monterrubio, 2022; Truong, 2018; Truong et al., 2020). Additionally, the study highlights the potential of tourism development to support the livelihoods of people experiencing poverty in rural areas (Saayman et al., 2020). Formal tourism activities, such as ecotourism lodges, can create job opportunities for people experiencing poverty, but their capacity may not be sufficient to accommodate all tourists in some seasons. Therefore, residents and people experiencing poverty capitalize on this opportunity by renting out their homes or rooms to tourists.

Overall, the study demonstrates that the informal sector is the primary source of employment for people experiencing poverty who wish to engage in tourism activities (Monterrubio, 2022). Despite the expectation that people experiencing poverty would work in the formal sector, they lack training and support from government and non-governmental organizations, leading them to pursue informal jobs (Rogerson and Visser, 2014). Without specific support from such agencies, people experiencing poverty will continue to work in informal jobs (Truong, 2018; Rogerson, 2014b).

6 Conclusion

This study aimed to investigate the rural poor's involvement in tourism activities without external governmental or non-governmental assistance and to examine the impact of their participation in both formal and informal tourism markets on poverty reduction. The findings reveal that despite the limited support from outside the village, including ecotourism programs, community-based tourism, and tourism for the poor initiatives, the rural poor have actively sought to participate in tourism by establishing businesses, engaging in informal activities, and acquiring relevant skills and knowledge. However, the study also highlights the significant challenges faced by the rural poor in their efforts to participate in tourism, such as inadequate education, skills, capital, market access, information, and legal protection. These barriers hinder their ability to fully engage in official tourism activities and benefit from the potential economic opportunities provided by the industry.

Despite these challenges, the study suggests that tourism has the potential to foster the participation of the rural poor in rural areas. The absence of large-scale tourism developments, such as big hotels, and the limited influence and investment by affluent groups create a more significant opportunity for the local community, particularly people experiencing poverty, to engage in tourism activities. This finding aligns with the existing literature on tourism and poverty reduction, emphasizing tourism's potential to alleviate poverty by providing income generation, employment, and skill development opportunities for the rural poor. Moreover, the study highlights the importance of informal tourism activities in providing opportunities for the rural poor to participate in and benefit from tourism. While informal activities may not offer the same level of stability and protection as formal tourism businesses, they nevertheless play a crucial role in supporting the livelihoods of the poor and contributing to poverty reduction.

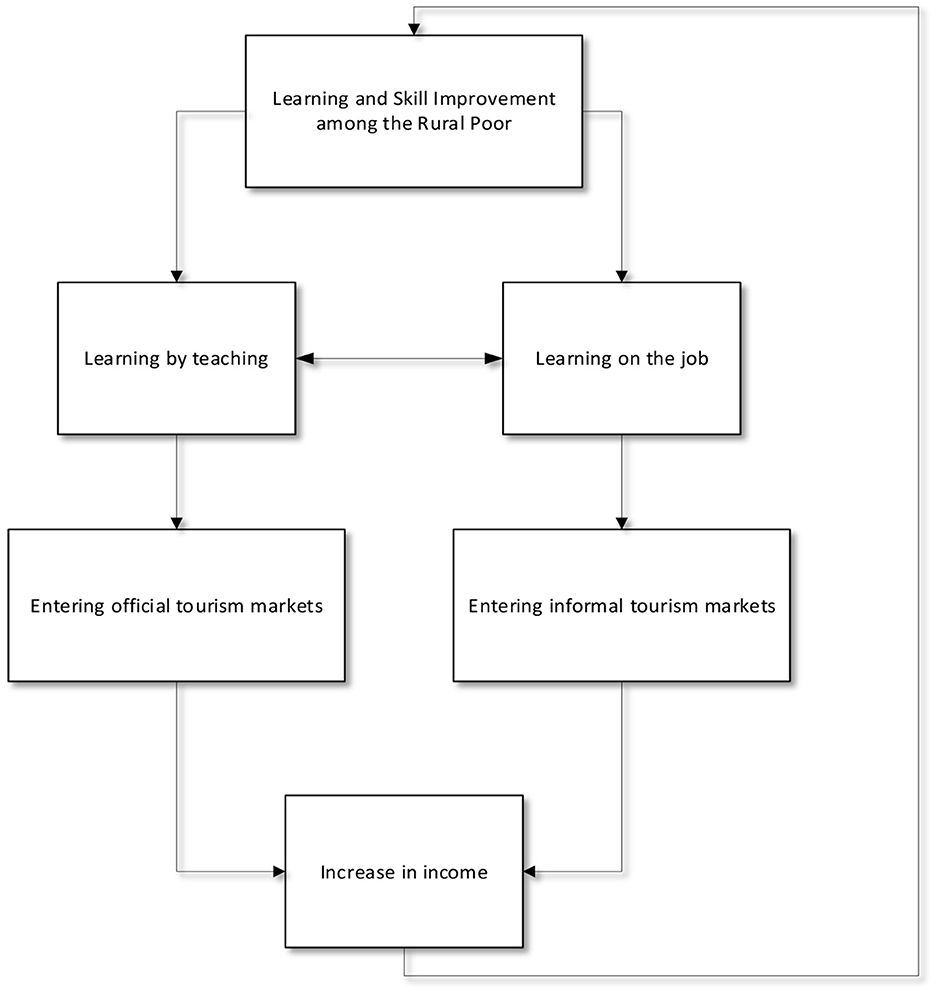

The participation of people experiencing poverty in tourism businesses, as illustrated in Figure 2, demonstrates the various pathways through which the rural poor engage in tourism activities, including establishing businesses, participating in informal activities, and acquiring relevant skills and knowledge. This process highlights the agency and resilience of the rural poor in navigating the challenges and opportunities presented by the tourism industry.

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on tourism and poverty reduction by providing empirical evidence on how the rural poor participate in tourism activities without external assistance and the impact of their participation on poverty reduction. It highlights the potential of tourism to foster the participation of people experiencing poverty in rural areas while also identifying the challenges that need to be addressed to realize this potential fully. The findings of this study have important implications for policy and practice and can inform the development of more effective and inclusive strategies for harnessing the power of tourism as a tool for poverty reduction in rural areas.

6.1 Theoretical implications

This study makes several significant contributions to the theoretical understanding of tourism and poverty reduction, particularly in rural areas in developing countries. By providing empirical evidence on the participation of the rural poor in tourism activities without external support from governmental or non-governmental organizations, the findings of this study extend the existing knowledge base on the potential of tourism to reduce poverty and stimulate economic development in rural areas.

One of the key theoretical implications of this study is the importance of informal tourism activities in facilitating the participation of the rural poor in the tourism industry. While previous research has acknowledged the role of the informal sector in providing income and employment opportunities for people experiencing poverty (Saayman et al., 2020; Dossou et al., 2023; Wang and Dong, 2022), this study provides a more nuanced understanding of how informal tourism activities specifically contribute to poverty reduction in rural areas. The findings suggest that informal tourism activities, such as small-scale businesses, informal employment, and self-employment, play a crucial role in enabling the rural poor to engage in and benefit from tourism, even without formal support and resources.

This study also contributes to the theoretical understanding of the barriers and challenges that hinder the participation of the rural poor in formal tourism activities. The findings highlight the significance of factors such as lack of education, skills, capital, market access, information, and legal protection in limiting the rural poor's ability to fully engage in and benefit from formal tourism activities. This is consistent with previous research identifying these factors as key barriers to inclusive tourism development (Scheyvens, 2012; Wang and Dong, 2022; Liu and Yu, 2022; Dada et al., 2022). However, this study extends this understanding by providing empirical evidence on how these barriers specifically affect the rural poor in the context of tourism development in rural areas.

Furthermore, this study contributes to the theoretical debate on the role of tourism in poverty reduction and economic development in rural areas. While previous research has highlighted the potential of tourism to alleviate poverty and stimulate economic growth in rural areas (Anderson, 2015; Blake et al., 2008). Limited empirical evidence exists on the specific ways in which the rural poor participate in and benefit from tourism activities. This study addresses this gap by providing a detailed analysis of the strategies and pathways through which the rural poor engage in tourism and the impact of their participation on poverty reduction and economic development in rural areas.

The findings of this study also have important implications for theories of sustainable tourism development and inclusive growth. By highlighting the importance of informal tourism activities and the challenges faced by the rural poor in participating in formal tourism activities, this study suggests that a more holistic and inclusive approach to tourism development is needed. This approach should recognize the value of informal tourism activities in supporting the livelihoods of the poor and contributing to poverty reduction while also addressing the barriers and challenges that hinder the participation of the poor in formal tourism activities.

6.2 Practical and policy implications

The findings of this study have significant practical and policy implications for promoting sustainable tourism development and poverty reduction in rural areas. By providing empirical evidence on the participation of the rural poor in tourism activities and the challenges they face, this study offers valuable insights for policymakers and practitioners seeking to harness the power of tourism as a tool for poverty alleviation and inclusive growth.

One of the key practical implications of this study is the need for policymakers to recognize and support the role of informal tourism activities in reducing rural poverty. The findings suggest that informal tourism activities, such as small-scale businesses, informal employment, and self-employment, play a crucial role in enabling the rural poor to engage in and benefit from tourism, even without formal support and resources. Therefore, policymakers should develop and implement policies and programs that provide incentives and support for informal tourism activities, such as training and capacity building, access to credit and financial services, and market linkages (Saayman et al., 2020; Truong et al., 2022).

Another important practical implication of this study is the need for policymakers to invest in education and skills development programs to enable the rural poor to participate in formal tourism activities. The findings highlight the significance of factors such as lack of education, skills, and knowledge in limiting the ability of the rural poor to engage in and benefit from formal tourism activities fully. Therefore, policymakers should prioritize investments in education and training programs that provide the rural poor with the necessary skills and knowledge to participate in formal tourism activities, such as hospitality and tourism management, language skills, and cultural awareness (Akyeampong, 2011; Torabi et al., 2019).

Furthermore, policymakers must prioritize providing better market access and information to overcome the barriers that limit the rural poor's participation in formal tourism activities. The findings suggest that lack of access to markets and information is a significant barrier to the participation of the rural poor in formal tourism activities. Therefore, policymakers should develop and implement policies and programs that provide the rural poor with better access to markets and information, such as marketing and promotional support, trade fairs and exhibitions, and online platforms and networks.

Policies and regulations should also protect small-scale entrepreneurs in the tourism sector from exploitation and unfair competition and provide access to legal services to enforce their rights. The findings suggest that the rural poor often face challenges such as exploitation, unfair competition, and lack of legal protection when participating in tourism activities. Therefore, policymakers should develop and implement policies and regulations that protect the rights and interests of small-scale entrepreneurs in the tourism sector, such as minimum wage laws, social protection schemes, and access to legal services.

Investing in rural infrastructure, such as roads, transportation, communication, and electricity, can also facilitate sustainable tourism development in rural areas. The findings suggest that lack of infrastructure and basic services in rural areas is a significant barrier to the participation of the rural poor in tourism activities. Therefore, policymakers should prioritize investments in rural infrastructure and basic services to create an enabling environment for sustainable tourism development and poverty reduction in rural areas (Akyeampong, 2011; Holden et al., 2011).

Finally, policymakers should engage the private sector in tourism development projects and encourage them to invest in rural tourism activities. The findings suggest that the absence of large-scale tourism developments and the limited influence and investment by affluent groups create a more significant opportunity for the local community, particularly the poor, to engage in tourism activities. Therefore, policymakers should develop and implement policies and programs encouraging private sector investment in rural tourism activities, such as tax incentives, subsidies, and public-private partnerships (Ashley and Mitchell, 2009; Mitchell and Ashley, 2009).

6.3 Limitations and suggestions for further research

Despite providing valuable insights into the participation of the rural poor in tourism activities and the impact of this participation on poverty reduction, this study has limitations that must be acknowledged. One of the main limitations of this study is its small sample size. The research was conducted in selected villages in Shahrud County, Iran, and its findings may not be generalizable to other rural areas with different socio-cultural, economic, and geographical characteristics. Therefore, further research is necessary to confirm the study's results and examine the extent to which the findings are applicable to other rural contexts. To address this limitation and obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the participation of the rural poor in tourism activities, future studies should employ larger samples and more diverse methodological approaches. Quantitative or mixed-methods research designs could provide a stronger and more generalizable understanding of the relationships between tourism, poverty reduction, and the participation of the rural poor.

Another important limitation of this study is its focus on a specific geographical context. The socio-cultural, economic, and geographical characteristics of the selected villages in Shahrud County, Iran, may differ significantly from those of other rural areas, both within Iran and in other countries. Therefore, the findings of this study may not be directly applicable to other rural contexts. Furthermore, this study primarily focuses on the perspectives and experiences of the rural poor and those of local officials, managers, and tourism business owners, which may not capture the full range of factors that influence the success and sustainability of tourism-based poverty reduction strategies. Finally, this study provides a snapshot of the participation of the rural poor in tourism activities at a specific time while the tourism industry is dynamic and evolving, and the factors influencing the participation of the rural poor in tourism activities may change over time. Therefore, future studies should examine a broader range of geographical areas and stakeholders and investigate the long-term impacts of tourism on poverty reduction and the participation of the rural poor in tourism activities to contribute to developing more effective and sustainable tourism-based poverty reduction strategies in rural areas.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Z-AT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adie, B. A. (2019). “Urban renewal, cultural tourism, and community development: 213Sharia principles in a non-islamic state,” in The Routledge Handbook of Halal Hospitality and Islamic Tourism (Routledge: Taylor and Francis), 213–223.

Adiyia, B., and Vanneste, D. (2018). Local tourism value chain linkages as pro-poor tools for regional development in western Uganda. Dev. South. Africa 35, 210–224. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2018.1428529

Akyeampong, O. A. (2011). Pro-poor tourism: residents' expectations, experiences and perceptions in the Kakum National Park area of Ghana. J. Sustain. Tour. 19, 197–213. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2010.509508

Amuedo-Dorantes, C. (2004). Determinants and poverty implications of informal sector work in Chile. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 52, 347–368. doi: 10.1086/380926

Anderson, W. (2015). Cultural tourism and poverty alleviation in rural Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. J. Tour. Cult. Change 13, 208–224. doi: 10.1080/14766825.2014.935387

Ashley, C., and Mitchell, J. (2009). Tourism and Poverty Reduction: Pathways to Prosperity. London: Taylor & Francis.

Ashley, C., and Roe, D. (2002). Making tourism work for the poor: strategies and challenges in southern Africa. Dev. South. Africa 19, 61–82. doi: 10.1080/03768350220123855

Azqueta, D., and Montoya, A. (2011). Water access in the fight against poverty: tourism or multiple use of water services? Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. 2, 44–54. doi: 10.4018/jsesd.2011100104

Babalola, A. B., and Ajekigbe, P. G. (2007). Poverty alleviation in Nigeria: need for the development of archaeo-tourism. Anatolia 18, 223–242. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2007.9687203

Beccaria, L., and Groisman, F. (2008). Informalidad y pobreza en Argentina. Investigación económica 67, 135–169.

Biswas, S. N. (2014). Pro-poor Development Through Tourism in Economically Backward Tribal Region of Odisha, India. Hospitality, Travel, and Tourism: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications. Pennsylvania, PA: IGI Global.

Blake, A., Arbache, J. S., Sinclair, M. T., and Teles, V. (2008). Tourism and poverty relief. Ann. Tour. Res. 35, 107–126. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2007.06.013

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Buckley, R. (2012). Sustainable tourism: research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 39, 528–546. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2012.02.003

Butler, R., Curran, R., and O'Gorman, K. D. (2013). Pro-poor tourism in a first world urban setting: case study of glasgow govan. Int. J. Tour. Res. 15, 443–457. doi: 10.1002/jtr.1888

Ceballos-Lascurain, H. (1996). Tourism, Ecotourism, and Protected Areas: the State of Nature-Based Tourism Around the World and Guidelines for Its Development. Gland: IUCN.

Chettiparamb, A., and Kokkranikal, J. (2012). Responsible tourism and sustainability: the case of Kumarakom in Kerala, India. J. Pol. Res. Tour. Leisur. Events 4, 302–326. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2012.711088

Chok, S., Macbeth, J., and Warren, C. (2007). Tourism as a tool for poverty alleviation: a critical analysis of 'pro-poor tourism' and implications for sustainability. Curr. Iss. Tour. 10, 144–165. doi: 10.2167/cit303

Croes, R. (2014). Tourism and poverty reduction in Latin America: where does the region stand? Worldw. Hospital. Tour. Themes 6, 293–300. doi: 10.1108/WHATT-03-2014-0010

Dada, Z. A., Najar, A. H., and Gupta, S. K. (2022). Pro-poor tourism as an antecedent of poverty alleviation: an assessment of the local community perception. Int. J. Hospital. Tour. Syst. 15, 37–46.

De León, O. (1996). Economía informal y desarrollo: Teorías y análisis del caso peruano. Madrid: Instituto Universitario de Desarrollo y Cooperación.

Devicienti, F., Groisman, F., and Poggi, A. (2010). “Chapter 4 Are informality and poverty dynamically interrelated? Evidence from Argentina,” in Studies in Applied Welfare Analysis: Papers from the Third ECINEQ Meeting (Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 79–106.

Dossou, T. A. M., Ndomandji Kambaye, E., Bekun, F. V., and Eoulam, A. O. (2023). Exploring the linkage between tourism, governance quality, and poverty reduction in Latin America. Tour. Econ. 29, 210–234. doi: 10.1177/13548166211043974

Folarin, O., and Adeniyi, O. (2020). Does tourism reduce poverty in sub-saharan African countries? J. Travel Res. 59, 140–155. doi: 10.1177/0047287518821736

Ghaderi, Z., Abooali, G., and Henderson, J. (2018). Community capacity building for tourism in a heritage village: the case of Hawraman Takht in Iran. J. Sustain. Tour. 26, 537–550. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2017.1361429

Ghaderi, Z., Esfehani, M. H., Fennell, D., and Shahabi, E. (2023). Community participation towards conservation of Touran National Park (TNP): an application of reciprocal altruism theory. J. Ecotour. 22, 281–295. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2021.1991934

Gohori, O., Van Der Merwe, P., and Saayman, A. (2022). Promotion of Pro-poor Tourism in Southern Africa: Conservation and Development Critical Issues. Protected Areas and Tourism in Southern Africa: Conservation Goals and Community Livelihoods. London: Taylor and Francis.

Goodwin, H. (2007). Indigenous Tourism and Poverty Reduction. Tourism and Indigenous Peoples: Issues and Implications. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Hall, C. M. (2007). Pro-poor tourism: do “tourism exchanges benefit primarily the countries of the south”? Curr. Iss. Tour. 10, 111–118. doi: 10.1080/13683500708668426

Hall, C. M. (2008). Tourism Planning: Policies, Processes and Relationships. London: Pearson Education.

Harrison, D. (2008). Pro-poor tourism: a critique. Third World Quart. 29, 851–868. doi: 10.1080/01436590802105983

Harrison, D., and Pratt, S. (2019). Tourism and Poverty. A Research Agenda for Tourism and Development. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Harrison, D., and Schipani, S. (2007a). “Lao tourism and poverty alleviation: community-based tourism and the private sector,” in Pro-poor Tourism: Who Benefits?: Perspectives on Tourism and Poverty Reduction (Bristol: Channel View Publications).

Harrison, D., and Schipani, S. (2007b). Lao tourism and poverty alleviation: community-based tourism and the private sector. Curr. Iss. Tour. 10, 194–230. doi: 10.2167/cit310.0

Hart, K. (1973). Informal income opportunities and urban employment in Ghana. J. Mod. Afri. Stud. 11, 61–89. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X00008089

Holden, A., Sonne, J., and Novelli, M. (2011). Tourism and poverty reduction: an interpretation by the poor of Elmina, Ghana. Tour. Plan. Dev. 8, 317–334. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2011.591160

Intapan, C., Chaiboonsri, C., and Piboonrungroj, P. (2021). Sustainable Tourism and Poverty Reduction in Selected ASEAN Member Countries. Economics, Law, and Institutions in Asia Pacific. Tokyo: Springer Japan.

Karim, R., Muhammad, F., Serafino, L., Latip, N. A., and Marzuki, A. (2020). Integration of pro-poor tourism activities in community-based development initiatives: a case study in high mountain areas of Pakistan. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 9, 848–852.

Kimaro, M. E., and Saarinen, J. (2019). Tourism and Poverty Alleviation in the Global South: Emerging Corporate Social Responsibility in the Namibian nature-Based Tourism Industry. Natural Resources, Tourism and Community Livelihoods in Southern Africa: Challenges of Sustainable Development. London: Taylor and Francis.

Li, S., Saayman, A., Stienmetz, J., and Tussyadiah, I. (2022). Framing effects of messages and images on the willingness to pay for pro-poor tourism products. J. Travel Res. 61, 1791–1807. doi: 10.1177/00472875211042672

Liu, Y., and Yu, J. (2022). Path dependence in pro-poor tourism. Environ. Dev. Sustainabil. 24, 973–993. doi: 10.1007/s10668-021-01478-x

Ma, Y., Ma, F., and Zheng, S. (2020). “The measure of poverty alleviation efficiency of tourism and spatiotemporal differentiation in Southwest China according to DEA-malmquist approach,” in Journal of Physics Conference Series (Bristol: IOP Publishing Ltd).

Maingi, S. W. (2021). Safari tourism and its role in sustainable poverty eradication in East Africa: the case of Kenya. Worldw. Hospital. Tour. Themes 13, 81–94. doi: 10.1108/WHATT-08-2020-0084

Manwa, H., and Manwa, F. (2014). Poverty alleviation through pro-poor tourism: the role of Botswana Forest Reserves. Sustainability 6, 5697–5713. doi: 10.3390/su6095697

Marquardt, D. (2018). Tourism Development Cooperation in a Changing Economic Environment—Impacts and Challenges in Lao P. D. R. Geographies of Tourism and Global Change. Berlin: Springer Nature.

Medina-Muñoz, D. R., Medina-Muñoz, R. D., and Gutierrez-Perez, F. J. (2016). The impacts of tourism on poverty alleviation: an integrated research framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 24, 270–298. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2015.1049611

Mitchell, J., and Ashley, C. (2009). Tourism and Poverty reduction: Pathways to Prosperity. London: Earthscan.

Moli, G. P. (2011). Community based eco cultural heritage tourism for sustainable development in the Asian region: a conceptual framework. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. 2, 66–80. doi: 10.4018/jsesd.2011040106

Monterrubio, C. (2022). The informal tourism economy, COVID-19 and socioeconomic vulnerability in Mexico. J. Pol. Res. Tour. Leisur. Events 14, 20–34. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2021.2017726

Mudzengi, B. K., Chapungu, L., and Chiutsi, S. (2018). Challenges and opportunities for “little brothers” in the tourism sector matrix: the case of local communities around Great Zimbabwe National Monument. Afri. J. Hospital. Tour. Leisur. 7, 1–12.

Mwesiumo, D., Juma Abdalla, M. D., Özturen, A., and Kilic, H. (2021). Effect of a perceived threat of informal actors on the business performance of formal actors: inbound tour operators' perspective. J. Travel Tour. Market. 38, 527–540. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2021.1952146

Nazier, H., and Ramadan, R. (2015). Informality and poverty: a causality dilemma with application to Egypt. Adv. Manag. Appl. Econ. 5, 31–60.

Nguyen, V. H. (2019). Tourism and poverty: perspectives and experiences of local residents in Cu Lao Cham MPA, Vietnam. Tour. Mar. Environ. 14, 179–197. doi: 10.3727/154427319X15631036242632

Nsanzya, B. M. K., and Saarinen, J. (2022). Tourism-Led Inclusive Growth Paradigm: Opportunities and Challenges in the Agricultural Food Supply Chain in Livingstone, Zambia. Geographies of Tourism and Global Change. Berlin: Springer Nature.

Nyahunzvi, D. K. (2015). Negotiating livelihoods among Chivi curio traders in a depressed Zimbabwe tourism trading environment. Anatolia 26, 397–407. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2014.974065

Peeters, P. (2012). Pro-Poor Tourism, Climate Change and Sustainable Development. Critical Debates in Tourism. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

Pillay, M., and Rogerson, C. M. (2013). Agriculture-tourism linkages and pro-poor impacts: the accommodation sector of urban coastal KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Appl. Geogr. 36, 49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.06.005

Portes, A., and Sassen-Koob, S. (1987). Making it underground: comparative material on the informal sector in Western market economies. Am. J. Sociol. 93, 30–61. doi: 10.1086/228705

Poyya Moli, G. (2013). Community Based Eco Cultural Heritage Tourism for Sustainable Development in the Asian Region: a Conceptual Framework. Creating a Sustainable Ecology Using Technology-Driven Solutions. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Qin, X., Wang, Y., Liu, L., Yuan, W., and Li, J. (2022). Research on the development potential of China's pro-poor tourism industry based on geographical nature evaluation. Sustainability 2022:14. doi: 10.3390/su142215069

Rakowski, C. A. (1994). Contrapunto: the Informal Sector Debate in Latin America. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Rogerson, C. (2014a). Viewpoint: how pro-poor is business tourism in the global South? Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 36, v–xiv. doi: 10.3828/idpr.2014.29

Rogerson, C. M. (2002). Tourism and local economic development: the case of the Highlands Meander. Dev. South. Africa 19, 143–167. doi: 10.1080/03768350220123918

Rogerson, C. M. (2006). Pro-poor local economic development in South Africa: the role of pro-poor tourism. Local Environ. 11, 37–60. doi: 10.1080/13549830500396149

Rogerson, C. M. (2012). Tourism-agriculture linkages in rural South Africa: evidence from the accommodation sector. J. Sustain. Tour. 20, 477–495. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.617825

Rogerson, C. M. (2014b). Informal sector business tourism and pro-poor tourism: Africa's migrant entrepreneurs. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 5, 153–161. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n16p153

Rogerson, C. M., and Visser, G. (2014). A decade of progress in african urban tourism scholarship. Urb. For. 25, 407–417. doi: 10.1007/s12132-014-9238-0

Saayman, A., Li, S., Scholtz, M., and Fourie, A. (2020). Altruism, price judgement by tourists and livelihoods of informal crafts traders. J. Sustain. Tour. 28, 1988–2007. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1781872

Saayman, M., and Giampiccoli, A. (2016). Community-based and pro-poor tourism: initial assessment of their relation to community development. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 12, 145–190. doi: 10.54055/ejtr.v12i.218

Saito, N., Ruhanen, L., Noakes, S., and Axelsen, M. (2018). Community engagement in pro-poor tourism initiatives: fact or fallacy? Insights from the inside. Tour. Recreat. Res. 43, 175–185. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2017.1406566

Sanches-Pereira, A., Onguglo, B., Pacini, H., Gómez, M. F., Coelho, S. T., and Muwanga, M. K. (2017). Fostering local sustainable development in Tanzania by enhancing linkages between tourism and small-scale agriculture. J. Clean. Prod. 162, 1567–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.164

Scheyvens, R., and Russell, M. (2012). Tourism and poverty alleviation in Fiji: comparing the impacts of small- and large-scale tourism enterprises. J. Sustain. Tour. 20, 417–436. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.629049

Schilcher, D. (2007). Growth Versus Equity: the Continuum of Pro-Poor Tourism and Neoliberal Governance. Pro-poor Tourism: Who Benefits? Perspectives on Tourism and Poverty Reduction. Channel View Publications.

Schneider, F., and Enste, D. H. (2000). Shadow economies: size, causes, and consequences. J. Econ. Literat. 38, 77–114. doi: 10.1257/jel.38.1.77

Sharpley, R., and Telfer, D. J., (eds.). (2014). Tourism and development: Concepts and issues. Multilingual Matters.

Soliman, M. S. A. (2015). Pro-poor tourism in protected areas—opportunities and challenges: “The case of Fayoum, Egypt”. Anatolia 26, 61–72. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2014.906353

Spenceley, A., and Goodwin, H. (2007). Nature-Based Tourism and Poverty Alleviation: Impacts of Private Sector and Parastatal Enterprises In and Around Kruger National Park, South Africa. Pro-poor Tourism: Who Benefits? Perspectives on Tourism and Poverty Reduction. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

Spenceley, A., and Meyer, D. (2012). Tourism and poverty reduction: theory and practice in less economically developed countries. J. Sustain. Tour. 20, 297–317. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2012.668909

Sudsawasd, S., Charoensedtasin, T., Laksanapanyakul, N., and Pholphirul, P. (2022). Pro-poor tourism and income distribution in the second-tier provinces in Thailand. Area Dev. Pol. 7, 404–426. doi: 10.1080/23792949.2022.2032227

Teltscher, S. (1994). Small trade and the world economy: informal vendors in Quito, Ecuador. Econ. Geogr. 70, 167–187. doi: 10.2307/143653

Theerapappisit, P. (2009). Pro-poor ethnic tourism in the Mekong: a study of three approaches in Northern Thailand. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 14, 201–221. doi: 10.1080/10941660902847245

Toerien, D. (2020). Tourism and poverty in rural South Africa: a revisit. South Afric. J. Sci. 2020:116. doi: 10.17159/sajs.2020/6506

Torabi, Z.-A., Rezvani, M. R., and Badri, S. A. (2021). Tourism, poverty reduction and rentier state in Iran: a perspective from rural areas of Turan National Park. J. Pol. Res. Tour. Leisur. Events 13, 188–203. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2020.1759081

Torabi, Z. A., Rezvani, M. R., and Badri, S. A. (2019). Pro-poor tourism in Iran: the case of three selected villages in Shahrud. Anatolia 30, 368–378. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2019.1595689

Torres, R. M., Skillicorn, P., and Nelson, V. (2011). Community corporate joint ventures: an alternative model for pro-poor tourism development. Tour. Plan. Dev. 8, 297–316. doi: 10.1080/21568316.2011.591158

Truong, S. E. A. V. D., Slabbert, E., and Nguyen, V. M. (2016). “Poverty in tourist paradise? A review of pro-poor tourism in South and South-East Asia,” in The Routledge Handbook of Tourism in Asia, 121–138.

Truong, V. D. (2018). Tourism, poverty alleviation, and the informal economy: the street vendors of Hanoi, Vietnam. Tour. Recreat. Res. 43, 52–67. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2017.1370568

Truong, V. D., Knight, D. W., Pham, Q., Nguyen, T. T., Nguyen, T. D., and Saunders, S. G. (2022). Fieldwork in Pro-poor Tourism: a Reflexive Account. Tourism Recreation Research. Taylor and Francis Ltd, United Kingdom.

Truong, V. D., Liu, X., and Pham, Q. (2020). To be or not to be formal? Rickshaw drivers' perspectives on tourism and poverty. J. Sustain. Tour. 28, 33–50. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2019.1665056

Vanegas Sr, M., Gartner, W., and Senauer, B. (2015). Tourism and poverty reduction: an economic sector analysis for Costa Rica and Nicaragua. Tour. Econ. 21, 159–182. doi: 10.5367/te.2014.0442

Wang, Q., Liao, Y., and Gao, J. (2022). Rural residents' intention to participate in pro-poor tourism in southern xinjiang: a theory of planned behavior perspective. Sustainability 2022:14. doi: 10.3390/su14148653

Wang, Z., and Dong, F. (2022). Experience of pro-poor tourism (PPT) in China: a sustainable livelihood perspective. Sustainability 2022:14. doi: 10.3390/su142114399

Winter, T., and Kim, S. (2021). Exploring the relationship between tourism and poverty using the capability approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 29, 1655–1673. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1865385

Zeng, B. (2018). How can social enterprises contribute to sustainable pro-poor tourism development? Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 16, 159–170. doi: 10.1080/10042857.2018.1466955

Zeng, B., and Ryan, C. (2012). Assisting the poor in China through tourism development: a review of research. Tour. Manag. 33, 239–248. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.08.014

Zeng, B., and Wang, C. (2019). Research progress in corporate social responsibility in the context of ‘tourism-assisting the poor' in China. J. China Tour. Res. 15, 379–401. doi: 10.1080/19388160.2019.1610131

Zhao, W., and Brent Ritchie, J. R. (2007). Tourism and Poverty Alleviation: An Integrative Research Framework. Pro-poor Tourism: Who Benefits? Perspectives on Tourism and Poverty Reduction. Bristol: Channel View Publications.

Keywords: rural poor, tourism and poverty reduction, formal and informal businesses, selected villages, Iran

Citation: Torabi Z-A (2024) Breaking barriers: how the rural poor engage in tourism activities without external support in selected Iranian villages. Front. Sustain. Tour. 3:1404013. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2024.1404013

Received: 20 March 2024; Accepted: 19 August 2024;

Published: 18 September 2024.

Edited by:

Balvinder Kler, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Paulin Wong, Quest International University Perak, MalaysiaSiao Fui Wong, Nanjing Tech University Pujiang Institute, China

Norzaris bin Abdul, Tawau Sabah Polytechnic, Malaysia, in collaboration with reviewer SW

Copyright © 2024 Torabi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zabih-Allah Torabi, emFiaWgudG9yYWJpQG1vZGFyZXMuYWMuaXI=

Zabih-Allah Torabi

Zabih-Allah Torabi