- Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research (ZMT), Bremen, Germany

Ocean tourism is a primary source of income for many small-island and coastal communities. Participatory processes have been advocated to develop and implement community-based management plans to address various problems induced from tourism development and achieve the desired and sustainable futures. One debate over such processes is the under-representation of children. Using drawing workshops with children, this paper aims to explore children's representations and temporal orientations toward the future of the marine environment of a tourist destination – Gili Trawangan in Indonesia. A total of 91 children participated in four drawing workshops in January 2023. They were asked to make two drawings based on the following broad questions: (1) What do you see/do at the sea and coast now? and (2) What do you want to see/do at the sea and coast 5 years later? They also attended a short interview to describe and explain what they had drawn. The children have represented uses of the sea and coast by themselves, other users as well as the marine animals. They have also expressed various temporal orientations through their drawings and interview, including anticipation, hope, expectation, concern, anxiety and despair. These temporal orientations offer a very strong set of information to be included in decision-making workshops and policy recommendations. This paper has reiterated that children do have a stake in such decision-making processes for their sustainable futures and thus their voices need to be heard. This paper is one of the attempts to provide opportunities for children to actively engage in research and have their voices heard through innovative methodologies. It is also the first attempt to explore children's orientations toward the marine futures with the intent to include such information in the subsequent decision-making process. It adds to the existing literature by engaging children's voices to promote inter-generational justice, and calls for increased efforts in the realization of such component in sustainable development.

1 Introduction

1.1 Under-representation of children in participatory processes for sustainable futures

Tourism is a primary source of income for many small-island and coastal communities, and ocean tourism is projected to be the largest part of ocean economy by 2030 (OECD, 2016). It is also an important social practice and plays a key role in the socialization process of local community. When a local community has become a tourist destination, the use of resources is negotiated within the host-guest exchange process (Uysal et al., 2016). The increased population and activities cause various negative environmental impacts. It is thus essential to take into account the impacts on different community groups. Participatory processes have been advocated for decision-making to develop and implement community-based management plans to achieve the desired and sustainable futures. One of the debates regarding participatory approaches is the representation of all stakeholders and subsequently the knowledge produced and used in devising solutions for and with the local communities.

However, children have mostly been under-represented in such participatory processes toward sustainable tourism (Schill et al., 2020; Seraphin and Yallop, 2020) and environmental management (O'Neill, 2001; Lidskog and Elander, 2007) despite children's high relevance to both the near and distant futures of such issues. Due to the geographical characteristics of these islands, children's everyday life is bounded to the island frequented with tourism activities. In other words, children share their leisure space with tourists visiting their island. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) has stipulated that children should have the rights to express their views freely in all matters affecting them and be provided the opportunity to be heard (United Nations, 1989). They are also key players in meeting related global conservation goals, such as United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals 14 Life under water, 15 Life on land, 16 Peace, justice and strong institutions as well as 17 Partnerships for the goals in this context. Environmental stewardship helps to meet these goals through motivations, a sense of responsibility and actions to care for, protect, and responsibly use the environmental resources around the island (Bennett et al., 2018; Strand et al., 2022). Children and future generations are believed to play a critical role in supporting ocean stewardship through maintaining reciprocal relationships between the island community and the more-than-human marine environment, and acknowledging rights, interests and values of customary stewards including children themselves (Fache et al., 2022a; Strand et al., 2022).

In order to achieve sustainable futures and inter-generational equity, it is essential to seek the perspective of children who are the future actors in tourism and stewards of the natural resources in their homelands. A gap, nonetheless, still exists in the inter-generational collaboration in global environmental governance (Zurba et al., 2020), despite the long-standing acknowledged importance of considering the “needs of the present without compromising the ability of the future generations to meet their own needs” (United Nations, 1987). The importance of intergenerational collaboration is reinforced by the report of the UN Secretary-General (2013) on “Intergenerational solidarity and the needs of future generations” to achieve inter-generational equity and justice in environmental management and stewardship. Compared to “children,” “youth” in governance and related issues such as learning, exchange, and decision-making has been more theoretically and empirically studied and practically achieved partly because “youth” entails a larger age range and it is less challenging to involve them in such processes. Thus, inter-generational participation in substantive decision-making is still not fulfilled (Zurba et al., 2020).

This under-representation of children could also be partly attributed to the prevalent assumption that children do not possess the cognitive capabilities and emotional competence required to make decisions or articulate their thoughts to be represented by others in decision-making. Their status in society excludes them from the decision-making processes, although they are likely affected by the decisions made by adults (Dowse et al., 2018; Seraphin and Green, 2019). They have been unjustly framed as “immature, vulnerable, incompetent, and hence in need of being gate-kept out of research” (Canosa and Graham, 2016, p. 219). It has been suggested that social research should focus more on children as they are less visible groups in society but as worthy research subject as any other social groups (Canosa et al., 2019b).

Compared to other disciplines, children's participation in tourism research is lagging behind (Canosa and Graham, 2016). However, a child-centered scholarship is gradually emerging in tourism research, as recent studies have recognized the agentive role of children and their right to participate in research about them (Schänzel and Carr, 2016; Canosa et al., 2019b). Children and young people are researched due to their increasingly recognized role in family travel decision-making process (e.g., Gram, 2007; Therkelsen, 2010; Yung and Khoo-Lattimore, 2018), tourism and hospitality entrepreneurship (e.g., Bakas, 2018; Canosa and Schänzel, 2021), and international volunteering or volunteer tourism in their later teenage stage (see the expansive body of literature). Earlier studies on children and childhood in tourism tended to focus on the family as one entire unit, or parents representing children's perceptions and experiences with or without the presence of their children (Schänzel, 2010; Carr, 2011; Schänzel and Smith, 2014; Khoo-Lattimore, 2015). It is, however, important to gauge their perceptions independent of the “grown-ups,” as they may influence what the children should think or say. Previous studies have also focused more on children as the guests but less on children being part of the host communities (Buzinde and Manuel-Navarrete, 2013; Canosa et al., 2019b), with a few exceptions (see Canosa et al., 2018, 2019a, 2020; Yang et al., 2020).

Increasing attentions to the voices of children themselves have been noticed. For instance, Rhoden et al. (2016) have captured children's opinions on their holiday experiences in the UK. Koščak et al. (2023) have used a post-test only experimental design to directly investigate children's perception of tourism development in six European countries. They explored children's attitudes toward tourism and hospitality businesses, and to what extent children are involved in the decision-making process for tourism planning and development. They found that children were not invited even though they are willing to express their opinions, and they generally have a negative attitude toward tourism because of the perceived negative social impacts (Koščak et al., 2023). While their research has contributed to the literature by exploring how much children are involved in the decision-making process, it is even more important to provide them the opportunity for their voices to be heard.

Canosa and Graham (2016) have posited that a coherent theoretical framework or paradigmatic stance to guide tourism research involving children and young people is still lacking. One key principle to such framework or paradigm is to acknowledge and activate their agency, competence and right to have their voices heard in matters affecting them (Canosa and Graham, 2016; Canosa et al., 2019b). Creative participatory methods are deemed effective to actively engage them in the research process, and resolve some of the methodological challenges that emerge while eliciting their opinions.

1.2 Children engagement and creative methodologies

Many creative and participatory methods have been used to engage children and youth in expressing their views, among which drawing is commonly used and proven effective. Drawing allows researchers to explore and understand children's perceptions and opinions in a relaxing environment in which they establish a closer relationship with the fieldworkers so that they are more willing to participate and share in the process (Barraza, 1999; Özsoy and Ahi, 2014). It is also easier for them to describe their inner feelings (Coates, 2002) or articulate imaginations by putting different aspects of their daily life within one single drawing than expressing verbally in interviews.

Drawing has been used in various studies eliciting children's perceptions and opinions. In the context of tourism, Koščak et al. (2018) used drawing as a surveying tool to explore children's perception of tourism development plans and discuss if they were given the opportunity to participate in decision-making. Seraphin and Green (2019) have looked at children's view of Winchester in the future through drawing and found that their visions of Winchester as a tourist destination offer some implications to its smart management and product and service design.

Some studies have used drawing to look at children's perceptions of or relationships with the environment. Alerby (2000) has studied how children think about the current environment and the meaning of their thoughts in relation to four themes, namely the good world, the bad world, the dialectics between the good and the bad world, and actions protecting the environment. She found that about 50% and 16% of the drawings represented the “good world” and “bad world” respectively. Some children in their study also represented different forms of actions through symbolic expressions such as recycling stations and eco-labeled products. Fache et al. (2022a) have explored how children in Fiji and New Caledonia perceive their relationship with the marine environment. The children in their study represented the sea beyond a land-sea compartment where both exploitation and conservation take place, and the sea as an intersection of human and more-than-human realms (Fache et al., 2022a).

Barraza (1999) is one of the first studies using drawing method to visualize children's perceptions of the current and future state of the environment in Mexico and the UK. The study showed that around 43% of the children did not represent any problem in the current state of the environment while 36.7% depicted at least one problem. It also showed that 54% of the children were not optimistic about the state of the earth after 50 years, revealing a deep concern for problems such as pollution, trash, loss of species and global warming, whereas 22% of children were still hopeful for a better state. However, the children made the drawings by pretending to be aliens coming to the planet Earth rather than perceiving the environment as a local resident. Fleer (2002) conducted a similar study with 486 children aged 5–12 in Australia to ask them to anticipate how the environment would look like when they were grandparents through drawing or writing. She found that a majority of children showed negative images of the future and the negativity increased with age. Children in her study featured a high level of pollution, health issues as well as a technological world with inventions. Özsoy and Ahi (2014) explored such perceptions in Turkey by analyzing drawings made by 828 elementary students. They found that 28.5% of the children perceived a clean environment in 50 years' time while 40.3% had a perception of a polluted environment. All these studies looked at a comparison of the current and a very distant future state the environment, which could be difficult for children to imagine and project the changes of the environment.

Pellier et al. (2014) also employed drawing methods to understand children's perceptions toward the present and future conditions of forests and wildlife in 22 villages in Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo. Their study has shown children's awareness of environmental changes and a perceived deterioration of forest conditions over 15 years. Children in each village were divided into two groups, one group drew about the present condition while the other group drew about the expected conditions in 15 years' time, and each group made only one drawing collectively. The study focused on the relationships between the current land covers extracted from secondary datasets and the art elements of children's drawings. Undeniably, these previous studies looking at the perceived present and future environmental conditions through children's drawings have strong implications; however, this body of literature is still limited. There is also a lack of studies specifically exploring the affective dimension of their perceptions and using such perceptions for subsequent decision-making processes.

1.3 Children's orientations toward future

Emotions about the future, such as hope and anxiety, may be triggered by perceived environmental problems. This is evidenced by an expansive body of literature on eco-anxiety and environmental education. Studies have discussed anxiety specifically using the concepts of eco-anxiety or climate anxiety given that climate change is a critical and heated topic globally (Ojala, 2018; Pihkala, 2018; Clayton, 2020; Hickman et al., 2021; Crandon et al., 2022; Léger-Goodes et al., 2022), or hope toward global crisis and its importance in environmental education (Ojala, 2015, 2017; Buchanan et al., 2021). Various studies have unveiled a common trend that young people are anxious or helpless about global sustainability issues (e.g., Tucci et al., 2007; Threadgold, 2012; Nordensvard, 2014; Hickman et al., 2021), and manifested a wide range of anxiety from mild to very strong (e.g., Pihkala, 2020a,b; Ogunbode et al., 2021).

Anxiety and hope are two key concepts used in these studies, however, there is no one common definition for them. Anxiety involves negative emotionality or feelings of tension and worried thoughts (Clayton and Karazsia, 2020; Sangervo et al., 2022). Hope is an emotion that could be understood as a cognitive state of believing in the possibility of reaching a desirable goal (Lazarus, 1991) or an emotional negation of the negative (see Ojala, 2017 for more critical distinction of hope). Despite varied definitions, one common characteristic of these concepts is future-oriented. They can help people anticipate threats, and lead to adaptive preparations and take actions to achieve future goals; but they can also lead to passivity or escape from the reality or problem (Ojala, 2017; Kurth, 2018). In the context of anxiety or hope of young people, anticipatory thinking is deemed to be one competence to be promoted through ESD (Barth et al., 2007; Wiek et al., 2011). Ojala (2017) has stressed that future dimensions are firmly embedded in the concept of education for sustainable development (ESD) under the UN definition of sustainable development, but studies indicate that future dimensions are not always included in ESD and that many young people are pessimistic concerning the global future. Anticipation “assumes an active and critically reflective interaction with futures that are unknowable” (Amsler and Facer, 2017, p. 1). Anticipatory thinking in ESD enables young people to analyze and acknowledge uncertainties or changes of the future related to global problems and sustainability (Wiek et al., 2011; Wals and Schwarzin, 2012).

Lee et al. (2020) have conducted a synthesis review of perceptions and understandings of climate change of children and adolescents (aged 8 to 19), but they did not highlight a trend of examining emotions or future orientations of this age group. Previous studies on ecological emotions of young people tend to focus on the positive-negative binary of emotions, the impacts of such anticipatory emotions on the wellbeing and/or subsequent responses of children, or one particular type of emotion (largely hope and anxiety). These studies are also predominately about climate change or global environmental challenges as a whole. There is a need to broaden the discussion to marine tourism given its growing importance. An open approach, rather than focusing on one specific type of emotions, would help to unveil various future dimensions of perceptions the children possess.

There has been increased recognition that affective engagements play an important role in increasing attention and motivation, as well as shaping decision-making and collective action (Schneider et al., 2021). Future dimensions of the perceptions are not limited to emotions such as anxiety or hope; they could be analyzed as temporal orientations to the future (Bryant and Knight, 2019), representing “different ways in which the future may orient our present” and help us to better understand the quotidian (Bryant and Knight, 2019, p. 2). Bryant and Knight (2019) have explored, among various, six temporal orientations toward the future against the past and present, namely anticipation, expectation, speculation, potentiality, hope and destiny. Such orientations encompass affective dimensions toward the future, and multiple orientations can be present at the same time. Imaginaries of the future in various affective ways guide people to see the other side of the frontier—a magical vision that does not exist yet (Tsing, 2004; Battaglia, 2017; as cited in Bryant and Knight, 2019). In other words, these orientations can interact and help to inform decision-making (Knight and Stewart, 2016; Bryant and Knight, 2019), and allow people to live the future in the present life through planning, practice and actions. Temporal orientations offer a useful lens to support decision-making for sustainable development by situating children's oriented future in the present. Looking into these orientations gives a “thickness” to the voices of the young stakeholders.

Fache et al. (2022a) have posited, children's views of sustainable futures should be considered although they do not have a stake in the decision-making processes. As discussed earlier, there is limited evidence of including such information in the actual decision-making processes for these issues. In addition, there is a paucity of focus on the affective future dimensions of children's perceptions of the environment or tourism development in the existing literature. In light of this research gap, this paper aims to explore children's representations and temporal orientations of the marine environment of a tourist destination using drawing workshops with school children. It then aims to use their voices as one type of information for the subsequent decision-making processes for tourism and marine futures of the island. To my knowledge, this is the first study using such approach to understand and engage children's voices in marine environmental and tourism management.

This study is focused on Gili Trawangan, a popular tourist destination in Indonesia (more details about Gili Trawangan in the next section). As the largest archipelagic country and second longest coastline in the world, Indonesia is endowed with diverse and rich marine ecosystems offering various ecosystem services, and is a hotspot for marine tourism. Nonetheless, studies on young people's perceptions of the future of the natural environment or tourism development are limited. Sulistyawati et al. (2018) employed a questionnaire survey to explore high school students' knowledge of climate change and its impacts on health in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Pellier et al. (2014) used creative methods to examine children's perceptions of environmental changes in forests in Kalimantan while Plush et al. (2020) discussed the value of using participatory media as a collaborative storytelling process for promoting meaningful youth participation in environmental governance. Nusantari (2008) has explored children's knowledge and values of marine ecosystems in two coastal villages in Lombok, Indonesia. She found that the children valued the local marine ecosystems because they understand their importance in food provision and their parents teach them to respect the marine environment. The author also highlighted the difference in children's values and attitudes. While they acknowledged the negative impacts of some human behaviors such as dumping waste into the sea, children from fishing families were less opposed to using the sea as a toilet due to traditional practices (Nusantari, 2008). This line of enquiry, however, is still limited, especially a lack of recent studies on young people's perceptions of the sustainable futures in relation to marine environment and tourism development. This study thus aims to respond to this research gap by using creative methods to explore children's orientations toward the marine futures on Gili Trawangan for subsequent decision-making processes.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study site

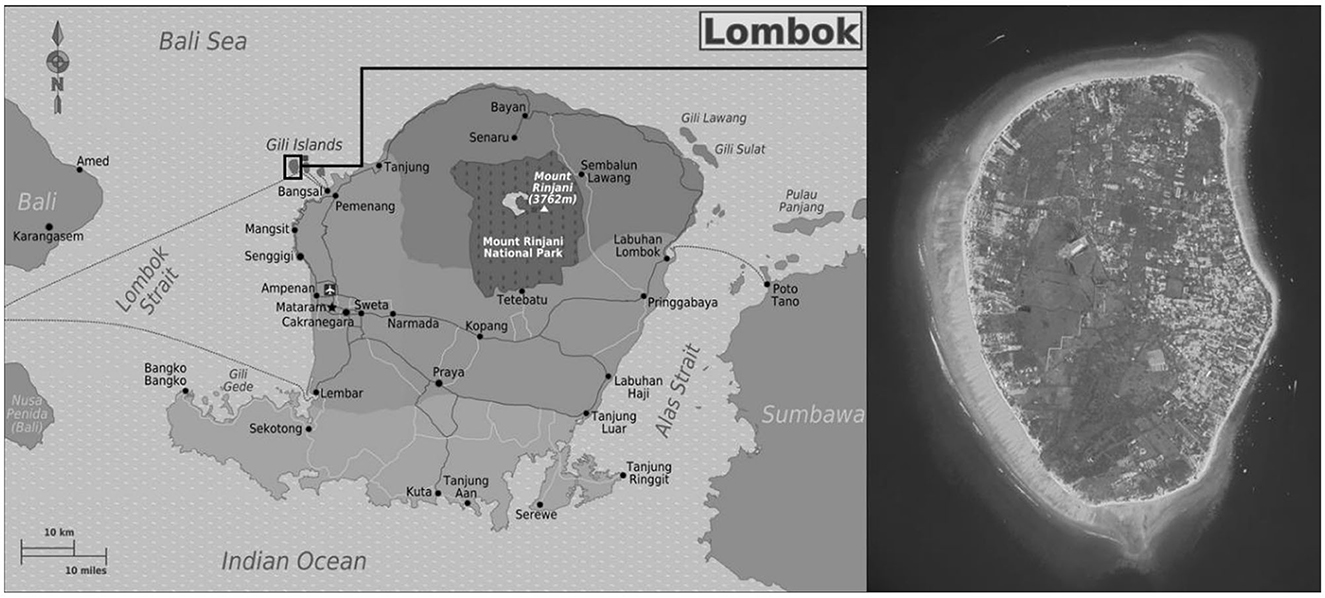

Gili Trawangan is one of the three field sites of the larger research project TransTourism, and drawing workshops with children was one of the methods conducted within this project framework. TransTourism aims to work together with small coastal communities and support decision-making processes which aim to promote sustainable tourism development and management of tourism-generated wastewater. Gili Trawangan is part of the archipelago off the coast of North Lombok, West Nusa Tenggara Province, Indonesia (Figure 1), with an area of 6 km2 and a population of 2,500 people (Partelow and Manlosa, 2023). It is easily accessible from Bali with fast boat in about three hours and Lombok with public boat in 25 min. Together with Gili Air and Gili Meno, the three Gilis were designated as the Gili Matra Marine Protected Area in 2001. International tourism has gradually replaced agriculture and fishing as its primary economic activity since the 1980s (Hampton and Hampton, 2009; Hampton and Jeyacheya, 2015). The island has had steady development from diving and tourism since the 1990s, with increased infrastructure and large resorts and hotels. The island then has evolved from a backpacking and diving destination in the 1990s to a sun, sand, sea, and nightlife one (Graci, 2013; Partelow and Manlosa, 2023). It attracts around one million tourists per year before the Covid-19 pandemic. While tourism has supported thousands of local livelihoods, it has also caused environmental degradation due to the large volume of solid waste and sewage generated, as well as the stress on marine ecosystems (Dodds et al., 2010). Tourism is found to be a major stressor on coastal and marine ecosystems of Gili Matra (Kurniawan et al., 2016), causing reduced seawater quality and increased vulnerability (Kurniawan et al., 2023). Facing increased amounts of pollution and environmental degradation, local NGOs have been taking a key role in waste collection and recycling, coral restoration, promoting tourism awareness and animal welfares (Partelow, 2021; Partelow et al., 2023).

Figure 1. Location of Gili Trawangan, Indonesia. Left: map showing Gili Trawangan's close proximity to Bali. Right: map of Gili Trawangan showing its building density in the east and west of the island. Source: https://de.m.wikivoyage.org/wiki/Datei:Lombok_Regions_map.png (available for use by other projects).

There are three schools on Gili Trawangan, namely SDN 2 Gili Indah, Bumblebee Montessori, and Chili House. SDN 2 Gili Indah is the local elementary school with children aged up to 13 years old and the number of classes and children are fixed. Bumblebee Montessori receives dominantly children of foreigners living on the island up to 8 years old but the number of children attending fluctuates over time. Chili House provides free schooling and extra-curriculum activities to all children on the island after their formal education in the morning but the number of children attending also varies daily depending on preferences of and arrangements by their parents. SDN 2 Gili Indah was thus chosen for conducting the drawing workshops based on the age and stable source of participants.

2.2 Drawing workshops

Research ethical clearance for all field activities in Indonesia within the TransTourism framework was conducted and approved both by the Ombudsperson in Leibniz Center for Tropical Marine Research (ZMT) in Germany to which I am affiliated and the National Research and Innovation Agency in Indonesia. Collaboration with local partners and research ethical clearance are pre-requisites for applying for an Indonesian research permit. Advice was given by local partners on the proposal and design of the drawing workshop method. I also explained the method in details and steps to minimize negative impacts on children in the ethical clearance form. Steps included discussions with local university and practice partners, school principal and teachers, as well as local field assistants. Although our local counterparts have long-standing partnerships with TransTourism and various projects in ZMT for over 13 years, they have had limited experiences of conducting research with children. Thus, discussions with school principal, teachers and field assistants, and exchange with other researchers with such experiences helped to address some limitations.

Prior to the drawing workshops, local field assistants and I contacted the school principal to invite participation and agree on a date and time for the activity. We then discussed the design of the activity. In the beginning of the TransTourism research fieldwork on Gili Trawangan, I also talked to the founder and principal of Chili House (which provides free schooling to children) and volunteered alongside their teachers and helpers, from which I learnt about the challenges of teaching and best ways to interact with children on the island. This also provided me with some background knowledge for planning and conducting the drawing workshops.

Written informed consent from parents or guardian for their children's participation was first asked through the school principal and class teachers. The purpose of the activity was explained to the children by the principal and teachers prior to the activity. At the introduction of each drawing workshop, the children were briefed about the activity and asked if they wanted to participate. They were also asked to inform us individually if they did not want to participate at any point of the activity while the field assistants were made fully aware of children's rights to withdraw (Ahmed, 2021; Ethical Research Involving Children, n.d.). Some children did not seem motivated at the beginning of the workshop mainly because they did not know what to draw instead of not wanting to participate. The field assistants encouraged them by telling them that there was no right or wrong answer and we were interested in their thoughts and experiences.

Short interviews with teachers were planned in the first meeting in the school to understand the curriculum and school/class activities related to environmental protection. However, it has often been the challenge for this school that the teachers are not able to travel from Lombok to Gili Trawangan every school day. Thus, the short interviews with class teachers were conducted after the drawing workshops.

Drawing workshops were carried out in four classes on 12-17 January 2023. All drawing workshops were conducted inside their classrooms. Each workshop lasted for two and half to three hours including drawing and interviews with the children. A total of 91 children participated, of which 39 were female and 52 were male, with an age of eight to 13.

The drawing workshop series in Indonesia was developed based on my previous experience and an interview guide adapted from Fache et al. (2022b) (see below). Each child received two pieces of paper, one pack of 12 color pencils and one sharpener. They were asked to make two drawings based on the following broad questions:

1) What do you see/do at the sea and coast now?

2) What do you want to see/do at the sea and coast 5 years later?

The questions were intended to be broad enough to allow them to draw their perceptions and uses of the coastal areas for different purposes. The 5-year timeframe was chosen to correspond with a scenario of having a wastewater treatment programme in 5 years' time in a focus group workshop with other tourism stakeholders within the TransTourism framework. As I do not speak Bahasa Indonesia or Sasak (a local dialect), the introduction was interpreted simultaneously by the field assistant. During the workshops, four to five field assistants helped answering questions from the children, encouraging them to make the drawings, and conducting the short structured interviews using the interview guide. Training was given to the field assistants before the workshop on how to guide the children and conduct the interview. We also debriefed after each drawing workshop to reflect on the process and suggest ways to improve the subsequent workshops. Two of the field assistants were more experienced in conducting interviews due to their long involvement with the TransTourism project, the other three were less experienced in social research. Therefore, a standard interview guide was used. The drawing interview guide (Table 1) was adapted for the Indonesian workshop series from the timely research by Fache et al. (2022b) in Fiji and New Caledonia. The six questions related to the drawings were mainly to record all the items on the drawings and the activities of animals and/or people, and to understand why the children drew in such ways in response to the questions. All interviews were audio-recorded while the field assistants jotted down answers on the printed interview guide. All drawings were kept by the project team for analysis and documentation. Class photos and a photobook compiling all drawings were made for the school as a souvenir.

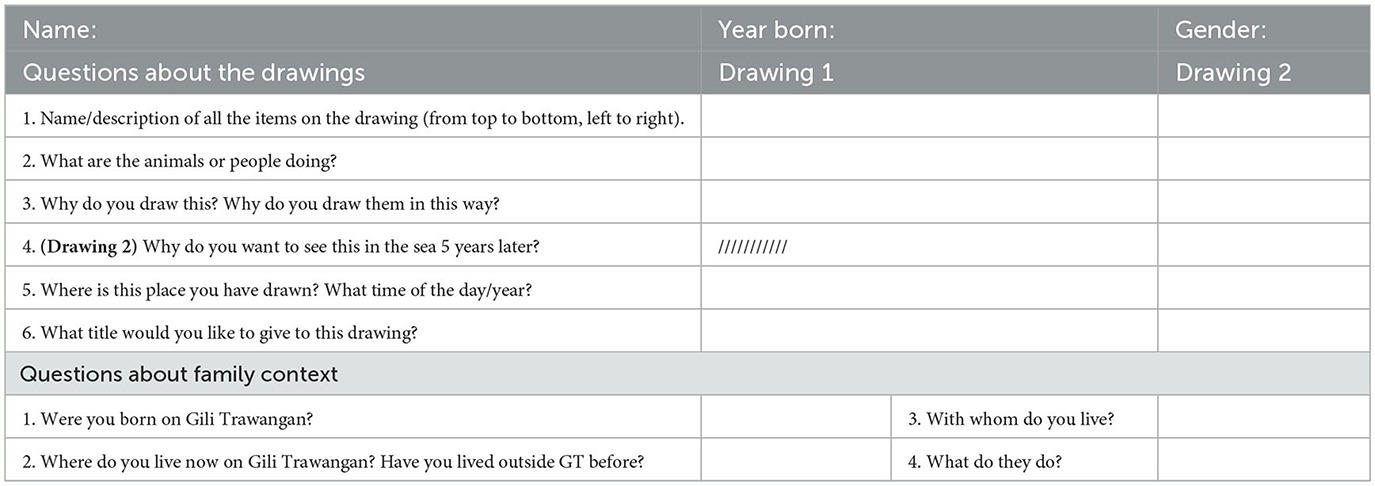

Table 1. Structured interview guide for short interview with children (originally in Bahasa Indonesia).

The structured interview was kept around 10–15 min per child by considering various factors, including the total length of the workshop allocated by the school principal, amount of time for the children to finish the drawings, and children's short attention span in an interview setting. Similar to Fache et al. (2022a), the depth of the interview information was restricted by the short and structured interviews in addition to my language barrier. The short answers to the interview questions could also be attributed to the fact that the children were not very expressive during interview and this may be due to their cultural background. Despite our efforts to keep the interviewees from the rest of the children, some children still came close to the child being interviewed. The interviewees became shyer and did not want other children to hear their responses. Another consideration was that the topic question for the drawing activity was quite broad and open, and the children may have been reticent to share sensitive information regarding (illegal) practices of other community members (see also Fache et al. (2022a). In addition, children finished their drawings at a different speed. In order to finish one drawing workshop before their lunchtime and not to interrupt their afternoon schedule in Chili House, we conducted the interview with the children once they completed the drawings. It is argued that interviewing children one-on-one may heighten the adult-child power relations as the interviewer may privilege particular interests and make inferences about children's responses (Mahon et al., 1996; Danby et al., 2011). However, by considering all the factors mentioned above, including cultures, sensitivity of information and practicality, individual interview was deemed more suitable and feasible than group interview in this case.

2.3 Data analysis

The drawings and interview data were analyzed using MS Excel and MaxQDA. Each child was assigned an ID for anonymity in all documentation. Demographic information of the children and their interview answers were compiled into an excel spreadsheet, with both original data in Bahasa Indonesian and the English translation in adjacent columns. Their answers were inputted verbatim without editing grammar. Drawings were analyzed in MaxQDA by coding the items shown on the drawings and activities of the people and animals. Activities of people and animals as well as the reasons for the representations of the items and activities were both coded in the spreadsheet and MaxQDA for quantitative and qualitative analysis. Themes emerged from such (re)coding and de-coding. Children's perceptions were also analyzed with reference to participant observation and participatory mapping interviews with other tourism stakeholders during my 8-month ethnography on Gili Trawangan and Lombok between October 2022 and May 2023. Through community mapping accompanied by local field assistants, informal conversations with locals and tourists as well as taking part in various activities organized by local NGOs such as beach clean-ups, coral restoration and tree planting, I have learnt about the socio-cultural-political dynamics of the island, and changes to the marine and coastal ecosystems over time. Participatory mapping interviews consisted of structured interviews to explore tourism stakeholders' perceptions of marine ecosystems, tourism development, sea water quality, and wastewater management on the island. Due to the aims of this paper, the interview data is not analyzed and discussed here but rather used as my knowledge of the island to supplement analysis and interpretation of the data collected from drawing workshops. From data entry to analysis, I consistently communicated with the field assistants to clarify interview data, to understand some topics and issues such as the types of fish commonly known to children on Gili Trawangan. Ongoing collaboration with our local university and practice partners throughout the larger project on data analysis has allowed me to develop a better understanding of data collected from these drawing workshops.

3 Children's perceptions of the sea and coast

From analysis of the drawings and children's sharing in the short interview, the children have represented how the sea and the coast is being used by humans and non-humans, and their orientations toward its future conditions.

3.1 Current uses of the sea and the coast

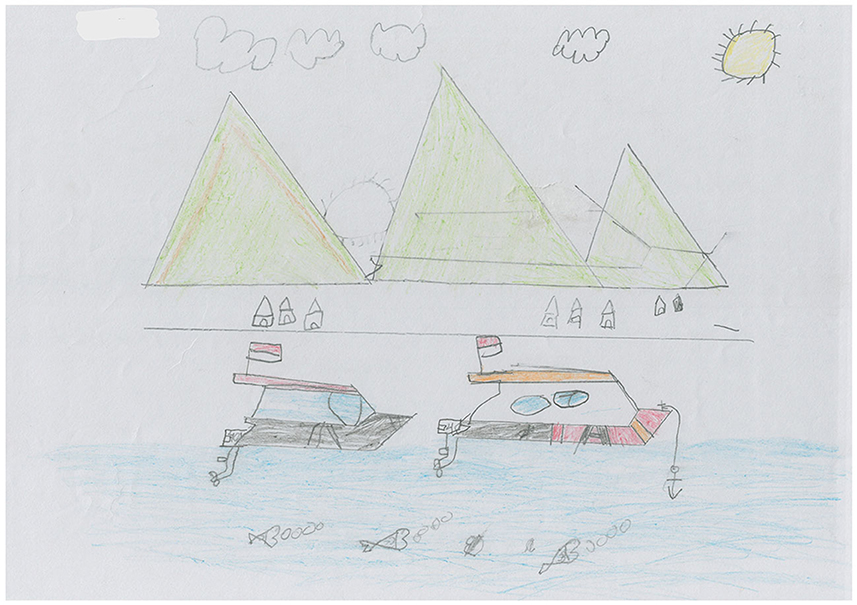

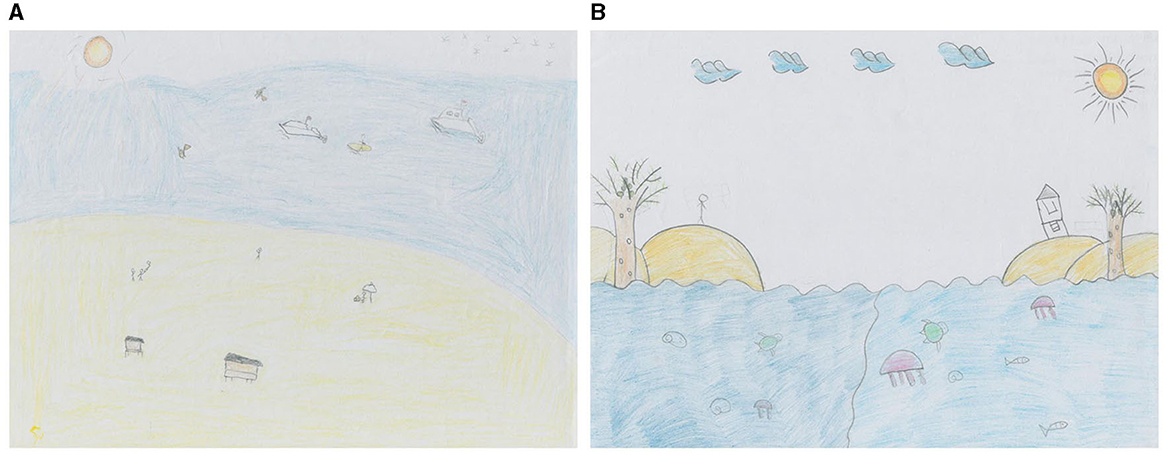

The children showed various uses of the marine and coastal environment for themselves, other groups of people, and animals in the sea in their first drawing. Out of the 91 drawings, only three children (GD45, GD58, and GD67) focused on their own uses and themselves as the sole users of the sea and coast (Figures 2, 3). These uses include enjoying the scenery, relaxing, and having fun with family or friends at the beach. In one of these drawings, the child GD45 situated his home by the sea among some other buildings which connects him to other activities in the sea (Figure 3).

Figure 2. (A) “Have Fun on the Beach” (GD58, 10-year-old boy, first drawing). (B) “Looking at the Scenery” (GD67, 11-year-old girl, first drawing).

In most drawings, the children referred to “some people” or specific groups of people such as fishers and boat passengers as the users of the sea and coast. They captured the importance of the sea or coast in various ways that they have seen before, many of which occur very often in their everyday life. A total of 14 drawings depicted the uses of the marine and coastal space for leisure, including water sports (swimming, snorkeling, and surfing) and relaxation and socialization at the beach (e.g., relaxing, enjoying scenery, playing, taking photos, partying, doing exercise, and camping).

A total of 43 children mentioned boats of all kinds (including boat, ship and sampan), with or without related human activities. Among these drawings, 25 children drew about the sea as the passage between islands, and the boat as the mode of transportation. Specifically, 10 of them depicted boats traveling between Gili Trawangan and Lombok, four depicted big boats or fast boats bringing passengers to Bali, and 11 depicted big boats or speed boats carrying passengers in general.

Twelve drawings mentioned fishing as one of the activities by “other people.” Six children specifically described that fishing boats are looking for fish for food; five only said “someone is fishing,” and one drew about fishing as work for the people among other activities at the harbor area (Figure 4). In Figure 4, this child GD6 also drew about other occupations at the sea or coast, including escorting the guests and driving the boat as boat captain. These drawings show that the children see the importance of the sea as a place for food provision and work.

Figure 4. A 9-year-old boy depicted various types of occupations in the coastal area in his drawing titled “Work at Sea” (GD6, first drawing).

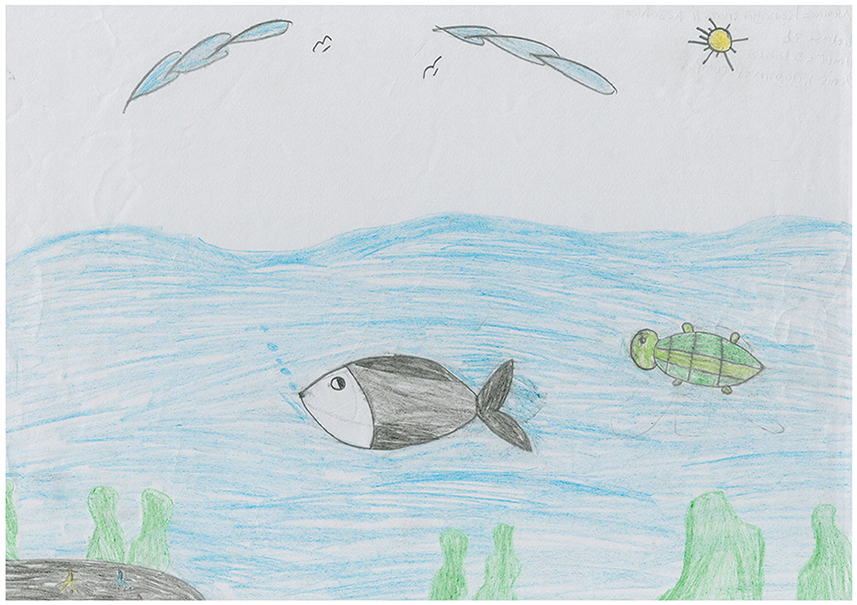

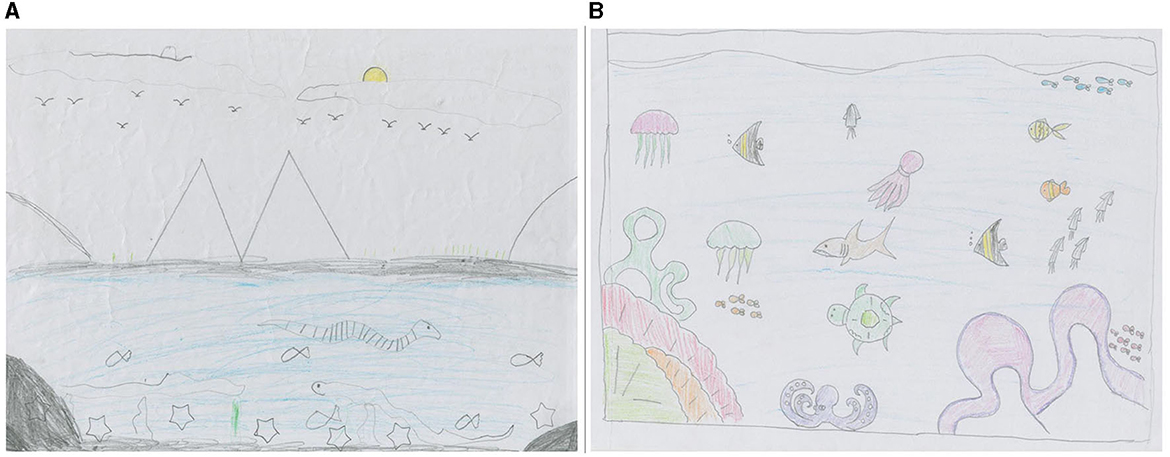

In addition to the human activities, children also represented the importance of the sea for both the survival of marine life and the leisure, as evidenced by the presence of marine animals in 76 drawings. A total of 27 drawings showed marine animals in search of food, sleeping, breathing and looking for shelter, with one example shown in Figure 5. These survival activities represent the presence of marine ecosystems, including 17 species of fish and 15 other types of animals and vegetation. Two drawings denoted that reef is a dynamic ecosystem in which different things support one another (Figure 6). The sea is also believed to be a space for leisure activities, as shown in 39 drawings. These recreational activities include playing, relaxing, looking for friends, having fun and swimming (not specifically swimming for survival needs).

Figure 5. A drawing titled “Squid” showing a squid hiding, a squid swimming and a hermit crab playing in the water (GD38, 10-year-old girl, first drawing).

Figure 6. (A) “Beautiful” (GD28, 9-year-old boy, first drawing). (B) “Various Animals in the Sea” (GD62, 10-year-old girl, first drawing).

3.2 Orientations toward the marine futures

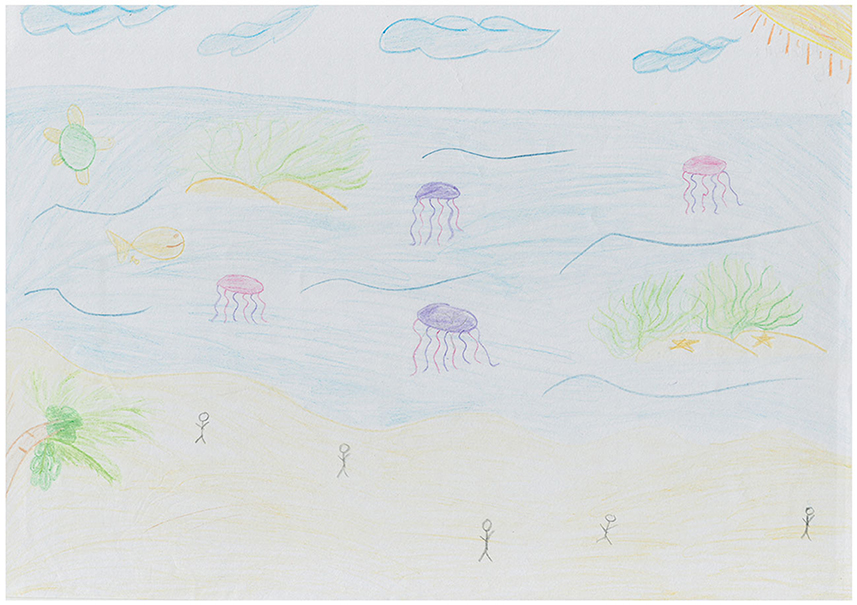

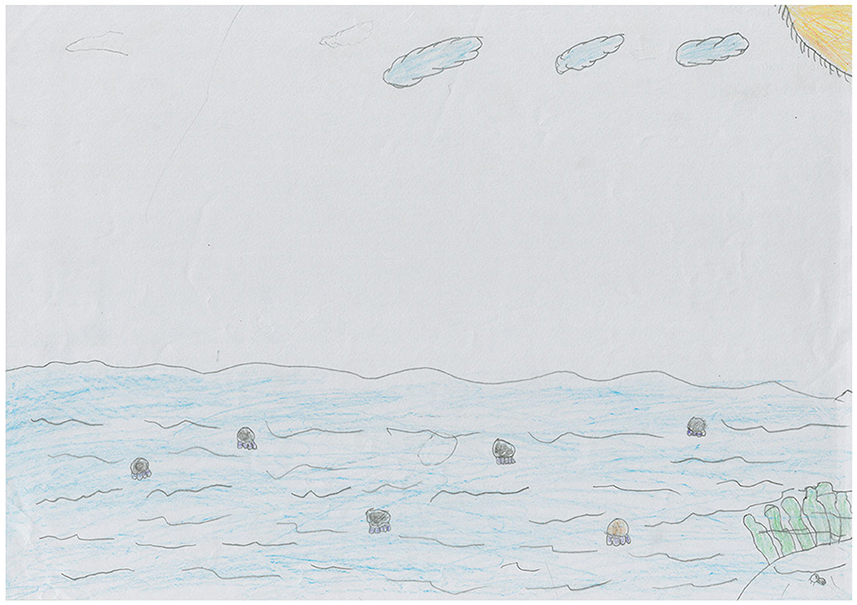

Among the second drawings, 40 children stated that they made the drawing simply because the view is nice, good or beautiful, and they wanted to see it 5 years later. In the breakdown, 55% included animals only, 20% were depicted without animals or people, 15% with both animals and people, and the remaining 10% with people only. They anticipated that things will remain in a good condition as they are.

Some children depicted the future marine environment with specific orientations. One child (GD86) wanted to see the sea remain the same as what he has seen, the way it should look like. As he described,

a bird flying freely in the fresh air, a squid going for a walk with its young, a man fishing and the fish looking for food, a snail looking for seaweed to eat. (“Ocean,” Figure 7)

Another child (GD29) said, “because later when you grow up you want to see things like this again.” According to him, “things like this” include:

a flying bird wants to go for a walk in the ocean, a fish goes for a walk in search of food, and a turtle swims in search of friends but does not meet and a starfish is playing hide and seek. (“A Sea of Fish,” Figure 8)

These two abovementioned drawings depicted a calm sea with animals inhabiting peacefully, or even having a fun time as the humans do, and a functioning ecosystem. This hope is also related to children's uses of the marine environment, so that they can still do the things they want to. One girl (GD84) imagined a clean sea full of animals and hoped that she “can swim further out,” while another girl (GD67) hoped she could still have fun with her friends as she swims with them in the sea now.

Their temporal orientations have also unveiled pollution problems in the sea and coast. A total of 15 drawings represented issues related to cleanliness of the sea and coast. Three children (GD63, GD71, and GD82) said they wanted to see a clean and nice sea and beach even in their first drawing about the current state of the sea. They featured their concerns of the current pollution problems. One of them described that:

with nothing to do the beach was deserted. The trees were cut down, and the ocean was littered with rubbish. I often see rubbish in the sea, so I drew this. It was dirty and there was a lot of rubbish. (“Dirty Environment,” Figure 9)

Another one said,

because I wanted the Trawangan sea to be clean, that's why I put a rubbish bin on the picture. (“Gili Trawangan Island,” Figure 10)

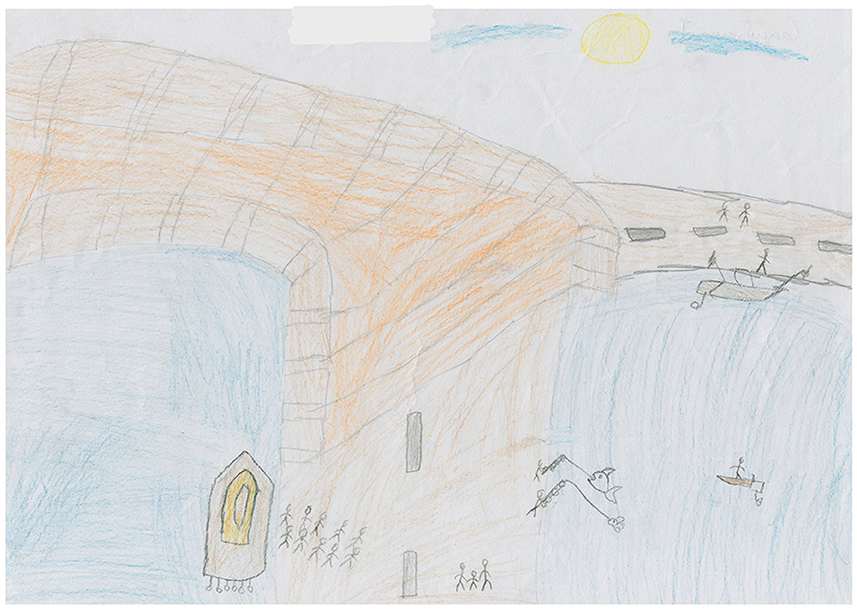

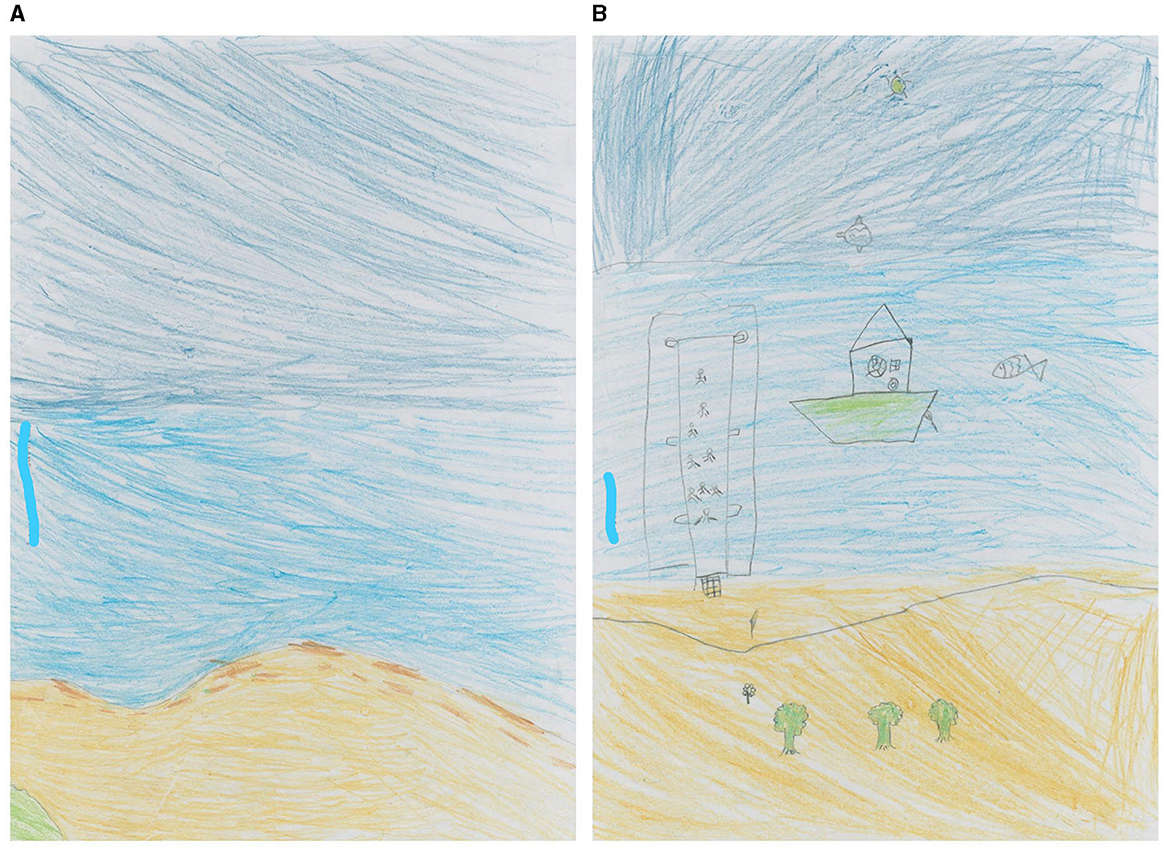

In the second drawing, seven children wanted to see the sea or beach “free from trash” in 5 years' time. Two children (GD34 and GD70) highlighted the connection between the behavior of the people in the present and the impacts on the environment in the future. GD34 showed a mix of despair and hope for the future (Figure 11). She put down shades of color without any items at the beach in the harbor area on the first drawing, as she explained,

there are no fish or people because the beach is full of rubbish… Now I could only see rubbish and a lot of dead fish.

Figure 11. (A) “Harbor in Gili Trawangan”. (B) “A Clean Beach” (GD34, 9-year- old girl, her first drawing on the left and her second drawing on the right).

Her second drawing represented her hope for a positive change of the condition. She drew specific items as she wanted to see a clearer view of the sea—people are traveling, fish are looking for food, and turtles are swimming. These represent a functioning marine ecosystem and normal human activities.

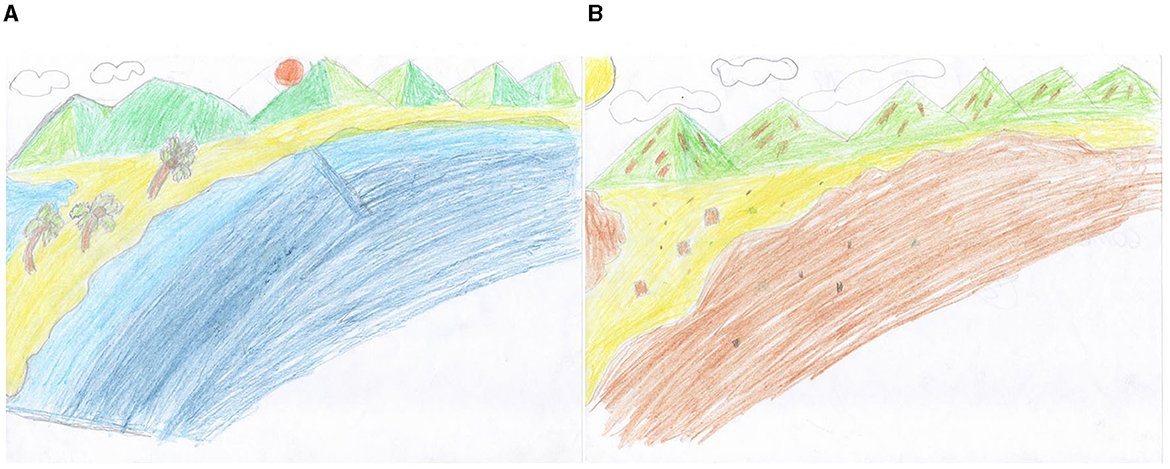

The other child GD70 showed relatively negative expectations with a sense of anxiety (Figure 12). He believed that currently the beach of Gili Trawangan still looks beautiful so he represented the nice scenery of the beach with blue sea water in the first drawing. As he has seen people littering at the beach, he “imagine[d] in the future the beach would look like that.” This expected future state includes trash in the sea and the beach, trees being cut down (brown patches on the mountains), and brown sea water. It shows his anxious expectations as he foresaw the result from current human behaviors in the future if these particular circumstances remain unchanged.

Figure 12. A negative expectation of the future compared to the present condition. (A) “Gili Trawangan with Twin Mountains”. (B) “Gili Trawangan Should Be Cleaned Up” (GD70, 11-year-old boy, his first drawing on the left and his second drawing on the right).

A few children showed their temporal orientation from indicators of functioning of the marine ecosystems. In their explanation, they have shown their concerns about the health and functions of the marine ecosystems. For example, one child (GD17) asserted that he did not want to see the sea green and full of rubbish, and hoped to see efforts to clean up the sea. A few children hoped for a safe and healthy marine ecosystem that supports the growth of marine life with indicative phrases including “big fish,” “no dead fish,” and “more animals.” Many children showed co-habitation of humans and marine animals by including both human and non-human activities in the sea without indicative conflicts. One girl (GD89) explicitly highlighted that such co-habitation represents the beauty of the nature which she hoped the tourists are able to see. She explained in the interview,

turtles are foraging, jellyfish are mating and fish are foraging while starfish are just relaxing. A picture of humans relaxing and some snorkeling… Because it sees the beauty of nature, humans swim and jellyfish stings, so that the sea is not lonely and there are many animals… for tourists to see the beauty of the ocean. (“Largest Island,” Figure 13)

4 Discussion and conclusion

Through the drawings, the children have captured the most common uses of the sea and the coast for local community and tourists on Gili Trawangan. Tourism is the primary economic activity, and the sea is an important asset for the sector to provide nature-based tourism activities especially snorkeling, diving, swimming and sunbathing. Enjoying sunset and chilling at the beach are also popular among locals and tourists. Due to its proximity to Bali and the availability of fast boat service, the harbor area is frequented with boats and tourists arriving and departing. Public and fast boats also run between Gili Trawangan and the other two Gili islands and Lombok. With the increased tourist arrivals and population of workers from Lombok and Bali, 80% of the island's land was developed for tourism by the mid-2010s (Bakti et al., 2021). More resorts and tourism-related businesses were being built in the less developed west side of the island during my ethnographic fieldwork. The increased population and human activities on the island and in the sea have caused various impacts, of which solid waste and destruction of coral reefs are two pressing issues facing the local community and being tackled by different initiatives by local NGOs and community groups. While some businesses have been trying to reduce the use of single use plastic, glass bottles are another major source of solid waste due to the high level of alcohol consumption by tourists.

From the drawings, the children in this study did not express explicitly a negative attitude toward tourists or tourism development, which is different from the finding of Koščak et al. (2023). One girl even had a positive hope for showing tourists the natural beauty of the island. It also embodies the potentiality of the sea as an asset for tourism. Although the children did not show a direct connection between tourism and environmental impacts, the impacts of unsustainable practices of “some people” can be seen from their representations, both explicitly and implicitly. Trash is one of the children's concerns both in the present and the future, in the sea and on the land, similar to the findings of previous studies (Barraza, 1999; Fleer, 2002; Özsoy and Ahi, 2014; Fache et al., 2022a). This is different from findings by Nusantari (2008) in terms of children's attitude toward dumping trash in the sea. This could be explained by the clean-up programme and class activities at the school. Students are encouraged to do clean-ups at the beach when trash is brought to the coast by wind or rain, and to use plastic bottles to make decorations in their classrooms and fences for small gardens in the school (Short interview with school teacher, 7 February, 2023). This could also be partly linked to the joint efforts of two local NGOs—Gili Eco Trust and FMPL (Front Masyarakat Peduli Lingkungan, local community environmental awareness group and solid waste management cooperative)—in trash collection and weekly beach clean-ups. The representation of dead fish and green and brown sea water, or the hope of seeing more and bigger marine animals could be associated with impacts from overfishing, unsustainable practices of human activities (e.g., diving, snorkeling and use of anchors), or excessive nutrients due to sewage discharge. Trees being cut down could imply clearance of land for new developments.

Due to the relatively short answers in the interviews, these connections or associations could not be verified. Despite these limitations, one should acknowledge the meanings and significance of these drawings, and the temporal orientations expressed through them. From the analysis, various orientations have been identified, including anticipation, hope, expectation, concern, anxiety and despair. A large amount of drawings showed their hope for a good view of the sea and coast by saying “want to.” Some others expressed their hope for a better future state of the sea and coast which is in-between the current state and the “not-yet.” Hope is stimulated by their visions that things or people's behavior in the present needs to be changed, or can be changed through actions, to achieve a potential future which is “not-yet” (Ojala, 2017; Bryant and Knight, 2019). This hope could also be interpreted as children's way of coping with the current negative circumstances (Lazarus, 1991). For example, the explicit call for more efforts to clean up or place a rubbish bin on the beach in one of the drawings could be interpreted as a symbol of hope that the litter problem could be resolved in the future by taking actions, similar to findings of Alerby (2000), but the “free from trash” hope is still a “not-yet” circumstance awaiting a solution.

Compared to hope, children's anticipation, negative expectation, or anxiety and despair may require more attention. This could imply that the younger generation has been impacted by current development or environmental changes to a certain extent, in terms of their access to the leisure space in the marine and coastal space or their wellbeing. They have also shown their awareness of impacts of human activities on the marine ecosystems, or anticipation of the changes of the environment if human behaviors are not altered. Their expected deterioration of the marine environment also urges us to reflect on the current efforts to resolve such problems by various stakeholders and decision-makers. It is also an implicit but strong call for management strategies and plans.

While the two guiding questions for making the drawing were set to be broad, there was no particular mention or concern about wastewater or tourism development. However, the drawings and short interviews have unveiled children's perceptions of the current conditions of the marine environment and tourism development on the island through their everyday experiences and observations. Their perceptions are similar to that of other tourism stakeholders revealed from other qualitative methods and participant observations within the same project framework. The other stakeholders shared a low level of awareness of wastewater as a problem. They reported similar indicators of the water quality such as color of sea water, amount of litter, and abundance and size of sea animals. These results showed that the children possess the cognitive capabilities to observe and link current human behaviors with subsequent environmental deterioration. They cannot compare the past with the present like the adult stakeholders do, but their orientations toward the future are critical and offer one dimension that helps to raise awareness and hopefully find solutions to the environmental challenges for a sustainable and desirable future. These drawings help to situate the future in the present through their affective orientations and acknowledge some concerning ways in which the marine environment is degrading. Thus, they should not be kept from participating in decision-making processes as they have both cognitive capabilities and emotional competence to play a key role as ocean stewards for a sustainable future (Canosa and Graham, 2016, p. 219).

Tourism-induced problems such as wastewater and the deterioration of the environment could be exacerbated by other factors such as low awareness, lack of management strategies and lack of collective action or commitments. In resolving such wicked problems, it is essential to include all stakeholders' voices in the decision-making processes in order to consider their perceived impacts and desired futures, both for the human and more-than-human worlds. This paper has reiterated that children do have a stake in such decision-making processes for their sustainable futures and thus their voices need to be heard. This paper aimed to create “opportunities for children to actively and ethically engage in research through innovative methodologies that facilitate their meaningful involvement,” as suggested by Canosa et al. (2019b, p. 97). Furthermore, to my knowledge, this is the first attempt to explore children's orientations toward the marine futures with the intent to include such information in decision-making processes. All their temporal orientations, such as anticipation, expectation, hope or anxiety, would have strong implications for the current management strategies, and bear certain weight in informing decisions. It indeed offers a very strong set of information to be included and presented to stakeholders and decision-makers and to develop policy recommendations. Translating hope into action would require goals, pathways and agency as suggested by Snyder (2000); similarly, a change to the pessimistic expectations or anxiety would require altered practices and collective response (Bryant and Knight, 2019). A sense of shared responsibility and collective action has been promoted through the idea of Gotong Royong (meaning collective action in Bahasa Indonesia) in textbook and the clean-up programme at the school, as well as the outreach projects of Gili Eco Trust (Short interview with school teacher, 7 February, 2023). The question of how to actualise these intents in a broader sense for the island would remain until decisions are to be made in the subsequent decision-making workshops. Compared to studies looking at the perceived state of the environment in a more distant future, situating the perceptions and temporal orientations in the 5-year timeframe would help develop short- and medium-term plans for tourism and environmental management. This paper also adds to the existing literature by engaging children's voices to promote inter-generational justice, and calls for increased efforts in the realization of such intents in sustainable development. This also supports what Fache et al. (2022b) have asserted that “children's drawings therefore represent an unconventional but promising way for more inter- and transdisciplinary approaches to marine social-ecological studies” (p. 758). It is hoped that this paper draws attention to the importance of including children's voices and their participations in initiatives and efforts to achieve a sustainable marine future at the local level.

A follow-up on this paper is to evaluate how children's voices are perceived and used in decision-making. It also calls for future research to explore and discuss how the knowledge and perceptions of younger generation are taken up by other adult stakeholders and decision-makers in various contexts. More research with the intention of including the young generation in the design phase of projects related to futures and sustainable development is also needed.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data will be used in decision-making workshops. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to YK, Y29ubmllLmt3b25nQGxlaWVibml6LXptdC5kZQ==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research (ZMT) and National Research and Innovation Agency in Indonesia. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

YK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This paper is part of the research project TransTourism (grant No. 01UU1905) funded by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) in the Programme for Social-Ecological Research.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the principal and teachers of SDN 2 Gili Indah for the realization of this drawing activity and all the children who participated for their invaluable creativity and sharing. Gratitude goes to Dr. Nurliah Buhari and colleagues of the University of Mataram as well as colleagues of Gili Eco Trust for their tremendous support throughout the whole TransTourism project. I am also grateful to Linda, Matla'ah, Rahman, Susi, Vini, and Yani for their field assistance. I would also like to thank the two reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmed, I. (2021). “Ethical research with children children: reflections from fieldwork fieldwork in Dhaka, Bangladesh Bangladesh,” in Navigating the Field: Postgraduate Experiences in Social Research, eds. M. O. Ajebon, Y. M. C. Kwong, and D. A. de Ita (Cham: Springer), 67–76. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-68113-5_6

Alerby, E. (2000). A way of visualising children's and young people's thoughts about the environment: a study of drawings. Environ. Educ. Res. 6, 205–222. doi: 10.1080/13504620050076713

Amsler, S., and Facer, K. (2017). Introduction to “learning the future otherwise: emerging approaches to critical anticipation in education.” Futures 94, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2017.09.004

Bakas, F. E. (2018). The political economy of tourism: Children's neglected role. Tour. Analy. 23, 215–225. doi: 10.3727/108354218X15210313504562

Bakti, L. A. A., Marjono, C., iptadi, G., and Putra, F. (2021). Resilience thinking approach to protect marine biodiversity in small islands: a case of Gili Trawangan, Indonesia. Earth Environ. Sci. 933, 012012. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/933/1/012012

Barraza, L. (1999). Children's drawings about the environment. Environ. Educ. Res. 5, 49–66. doi: 10.1080/1350462990050103

Barth, M., Godemann, J., Rieckmann, M., and Stoltenberg, U. (2007). Developing key competencies for sustainable development in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 8, 416–430. doi: 10.1108/14676370710823582

Bennett, N. J., Whitty, T. S., Finkbeiner, E., Pittman, J., Bassett, H., Gelcich, S., et al. (2018). Environmental stewardship: a conceptual review and analytical framework. Environ. Manage. 61, 597–614. doi: 10.1007/s00267-017-0993-2

Bryant, R., and Knight, D. M. (2019). The Anthropology of the Future. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108378277

Buchanan, J., Pressick-Kilborn, K., and Fergusson, J. (2021). Naturally enough? Children, climate anxiety and the importance of hope. Soc. Educ. 39, 17–31. doi: 10.3316/informit.352027058417490

Buzinde, C. N., and Manuel-Navarrete, D. (2013). The social production of space in tourism enclaves: Mayan children's perceptions of tourism boundaries. Ann. Tour. Res. 43, 482–505. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2013.06.003

Canosa, A., and Graham, A. (2016). Ethical tourism research involving children. Ann. Tour. Res. 61, 219–221. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2016.07.006

Canosa, A., Graham, A., and Wilson, E. (2018). Growing up in a tourist destination: negotiating space, identity and belonging. Childr. Geogr. 16, 156–168. doi: 10.1080/14733285.2017.1334115

Canosa, A., Graham, A., and Wilson, E. (2019a). “My overloved town: the challenges of growing up in a small coastal tourist destination (Byron Bay, Australia),” in Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism, eds. C. Milano, J. M. Cheer, and M. Novelli (Wallingford, UK: CAB International), 190–204. doi: 10.1079/9781786399823.0190

Canosa, A., Graham, A., and Wilson, E. (2019b). Progressing a child-centred research agenda in tourism studies. Tour. Analy. 24, 95–100. doi: 10.3727/108354219X15458295632007

Canosa, A., Graham, A., and Wilson, E. (2020). Growing up in a tourist destination: developing an environmental sensitivity. Environ. Educ. Res. 26, 1027–1042. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2020.1768224

Canosa, A., and Schänzel, H. A. (2021). The role of children in tourism and hospitality family entrepreneurship. Sustainability 13, 12801. doi: 10.3390/su132212801

Carr, N. (2011). Children's and Families' Holiday Experience (Vol. 22). London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203832615

Clayton, S. (2020). Climate anxiety: psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disor. 74, 102263. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102263

Clayton, S., and Karazsia, B. T. (2020). Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 69, 101434. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101434

Coates, E. (2002). “I Forgot the Sky!” Children's stories contained within their drawings. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 10, 21–35. doi: 10.1080/09669760220114827

Crandon, T. J., Scott, J. G., Charlson, F. J., and Thomas, H. J. (2022). A social–ecological perspective on climate anxiety in children and adolescents. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 123–131. doi: 10.1038/s41558-021-01251-y

Danby, S., Ewing, L., and Thorpe, K. (2011). The novice researcher: interviewing young children. Qualit. Inquiry 17, 74–84. doi: 10.1177/1077800410389754

Dodds, R., Graci, S. R., and Holmes, M. (2010). Does the tourist care? A comparison of tourists in Koh Phi Phi, Thailand and Gili Trawangan, Indonesia. J. Sustain. Tour. 18, 207–222. doi: 10.1080/09669580903215162

Dowse, S., Powell, S., and Weed, M. (2018). Mega-sporting events and children's rights and interests - towards a better future. Leisure Stud. 37, 97–108. doi: 10.1080/02614367.2017.1347698

Ethical Research Involving Children (n.d.). Informed Consent. Available online at: https://childethics.com/informed-consent/ (accessed November 8, 2023)..

Fache, E., Piovano, S., Soderberg, A., Tuiono, M., Riera, L., David, G., et al. (2022a). “Draw the sea…”: Children's representations of ocean connectivity in Fiji and New Caledonia. Ambio 51, 2445–2458. doi: 10.1007/s13280-022-01777-1

Fache, E., Sabinot, C., Pauwels, S., Riera, L., Breckwoldt, A., David, G., et al. (2022b). Encouraging drawing in research with children on marine environments: methodological and epistemological considerations. Hum. Ecol. 50, 739–760. doi: 10.1007/s10745-022-00332-6

Fleer, M. (2002). Curriculum compartmentalisation? A futures perspective on environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 8, 137–154. doi: 10.1080/13504620220128211

Graci, S. (2013). Collaboration and partnership development for sustainable tourism. Tour. Geograph. 15, 25–42. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2012.675513

Gram, M. (2007). Children as co-decision makers in the family? The case of family holidays. Young Consum. 8, 19–28. doi: 10.1108/17473610710733749

Hampton, M., and Hampton, J. (2009). “Is the beach party over? Tourism and the environment in small islands: a case study of Gili Trawangan, Lombok, Indonesia,” in Tourism in Southeast Asia: Challenges and New Directions, eds. M. Hitchcock, V. T. King, and M. Parnwell (Denmark: NIAS Press), 286–308.

Hampton, M., and Jeyacheya, J. (2015). Power, ownership and tourism in small islands: evidence from Indonesia. World Dev. 70, 481–495. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.12.007

Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, R. E., Mayall, E. E., et al. (2021). Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. Lancet Planet. Health 5, e863–e873. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3

Khoo-Lattimore, C. (2015). Kids on board: methodological challenges, concerns and clarifications when including young children's voices in tourism research. Curr. Issues Tour. 18, 845–858. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1049129

Knight, D. M., and Stewart, C. (2016). Ethnographies of austerity: temporality, crisis and affect in Southern Europe. Hist. Anthropol. 27, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/02757206.2015.1114480

Koščak, M., Colarič-Jakše, L.-M., Fabjan, D., Kukulj, S., ZaloŽnik, S., KneŽević, M., et al. (2018). No one asks the children, right? Tourism. 66, 396–410.

Koščak, M., Knežević, M., Binder, D., Pelaez-Verdet, A., Işik, C., Mićić, V., et al. (2023). Exploring the neglected voices of children in sustainable tourism development: a comparative study in six European tourist destinations. J. Sustain. Tour. 31, 561–580. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2021.1898623

Kurniawan, F., Adrianto, L., Bengen, D. G., and Prasetyo, L. B. (2016). Vulnerability assessment of small islands to tourism: the case of the Marine Tourism Park of the Gili Matra Islands, Indonesia. Global Ecol. Conserv. 6, 308–326. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2016.04.001

Kurniawan, F., Adrianto, L., Bengen, D. G., and Prasetyo, L. B. (2023). Hypothetical effects assessment of tourism on coastal water quality in the Marine Tourism Park of the Gili Matra Islands, Indonesia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 25, 7959–7985. doi: 10.1007/s10668-022-02382-8

Kurth, C. (2018). The Anxious Mind: An Investigation into the Varieties and Virtues of Anxiety. New York, NY: The MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/11168.001.0001

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and Adaptation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780195069945.001.0001

Lee, K., Gjersoe, N., O'Neill, S., and Barnett, J. (2020). Youth perceptions of climate change: a narrative synthesis. Wiley Interdisc. Rev. Clim. Change 11, 24. doi: 10.1002/wcc.641

Léger-Goodes, T., Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C., Mastine, T., Généreux, M., Paradis, P.-O., and Camden, C. (2022). Eco-anxiety in children: a scoping review of the mental health impacts of the awareness of climate change. Front. Psychol. 13, 872544. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.872544

Lidskog, R., and Elander, I. (2007). Representation, participation or deliberation? Democratic responses to the environmental challenge. Space Polity 11, 75–94. doi: 10.1080/13562570701406634

Mahon, A., Glendinning, C., Clarke, K., and Craig, G. (1996). Researching children: methods and ethics. Childr. Soc. 10, 145–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1099-0860.1996.tb00464.x

Nordensvard, J. (2014). Dystopia and disutopia: hope and hopelessness in German pupils' future narratives. J. Educ. Change 15, 443–465. doi: 10.1007/s10833-014-9237-x

Nusantari, H. (2008). Understanding of Marine Environments and Sustainability by Primary School Children in Lombok, Indonesia. (Master of Education). The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand.

OECD (2016). The Ocean Economy in 2030. Available online at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/9789264251724-en

Ogunbode, C. A., Pallesen, S., Böhm, G., Doran, R., Bhullar, N., Aquino, S., et al. (2021). Negative emotions about climate change are related to insomnia symptoms and mental health: cross-sectional evidence from 25 countries. Curr. Psychol. 42, 845–854. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01385-4

Ojala, M. (2015). Hope in the face of climate change: Associations with environmental engagement and student perceptions of teachers' emotion communication style and future orientation. J. Environ. Educ. 46, 133–148. doi: 10.1080/00958964.2015.1021662

Ojala, M. (2017). Hope and anticipation in education for a sustainable future. Futures 94, 76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2016.10.004

O'Neill, J. (2001). Representing people, representing nature, representing the world. Environ. Plan. C Govern. Policy 19, 483–500. doi: 10.1068/c12s

Özsoy, S., and Ahi, B. (2014). Elementary school students' perceptions of the future environment through artwork. Educ. Sci. 14, 1570–1582. doi: 10.12738/estp.2014.4.1706

Partelow, S. (2021). Social capital and community disaster resilience: post-earthquake tourism recovery on Gili Trawangan, Indonesia. Sustain. Sci. 16, 203–220. doi: 10.1007/s11625-020-00854-2

Partelow, S., Fujitani, M., Williams, S., Robbe, D., and Saputra, R. A. (2023). Disaster impacts, resilience, and sustainability opportunities for Gili Trawangan, Indonesia: transdisciplinary reflections following COVID-19. Disasters 47, 499–518. doi: 10.1111/disa.12554

Partelow, S., and Manlosa, A. O. (2023). Commoning the governance: a review of literature and the integration of power. Sustain. Sci. 18, 265–283. doi: 10.1007/s11625-022-01191-2

Pellier, A.-S., Wells, J. A., Abram, N. K., Gaveau, D., and Meijaard, E. (2014). Through the eyes of children: Perceptions of environmental change in tropical forests. PLoS ONE 9, e103005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103005

Pihkala, P. (2018). Eco-anxiety, tragedy, and hope: psychological and spiritual dimensions of climate change. Zygon® 53, 545–569. doi: 10.1111/zygo.12407

Pihkala, P. (2020a). Anxiety and the ecological crisis: an analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability 12, 7836. doi: 10.3390/su12197836

Pihkala, P. (2020b). Eco-anxiety and environmental education. Sustainability 12, 38. doi: 10.3390/su122310149

Plush, T., Wecker, R., and Ti, S. (2020). “Youth voices from the frontlines: facilitating meaningful youth voice participation on climate, disasters, and environment in Indonesia,” in Handbook of Communication for Development and Social Change, ed. J. Servaes (Singapore: Springer Singapore), 833–845. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-2014-3_134

Rhoden, S., Hunter-Jones, P., and Miller, A. (2016). Tourism experiences through the eyes of a child. Ann. Leisure Res. 19, 424–443. doi: 10.1080/11745398.2015.1134337

Sangervo, J., Jylhä, K. M., and Pihkala, P. (2022). Climate anxiety: conceptual considerations, and connections with climate hope and action. Global Environ. Change-Hum. Policy Dimens. 76, 11. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102569

Schänzel, H. A. (2010). Whole-family research: towards a methodology in tourism for encompassing generation, gender, and group dynamic perspectives. Tour. Analy. 15, 555–569. doi: 10.3727/108354210X12889831783314

Schänzel, H. A., and Carr, N. (2016). Introduction: special issue on children, families and leisure – part three. Ann. Leisure Res. 19, 381–385. doi: 10.1080/11745398.2016.1201241

Schänzel, H. A., and Smith, K. A. (2014). The socialization of families away from home: group dynamics and family functioning on holiday. Leisure Sci. 36, 126–143. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2013.857624

Schill, M., Godefroit-Winkel, D., and Hogg, M. K. (2020). Young children's consumer agency: the case of French children and recycling. J. Business Res. 110, 292–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.030

Schneider, C. R., Zaval, L., and Markowitz, E. M. (2021). Positive emotions and climate change. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 42, 114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.04.009

Seraphin, H., and Green, S. (2019). The significance of the contribution of children to conceptualising the destination of the future. Int. J. Tourism Cities 5, 544–559. doi: 10.1108/IJTC-12-2018-0097

Seraphin, H., and Yallop, A. (2020). An analysis of children's play in resort mini-clubs: potential strategic implications for the hospitality and tourism industry. World Leisure J. 62, 114–131. doi: 10.1080/16078055.2019.1669216

Snyder, C. R. (2000). Handbook of Hope: Theory, Measures, and Applications. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

Strand, M., Rivers, N., and Snow, B. (2022). Reimagining ocean stewardship: arts-based methods to “hear” and “see” Indigenous and local knowledge in ocean management. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 886632. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.886632

Sulistyawati, S., Mulasari, S. A., and Sukesi, T. W. (2018). Assessment of knowledge regarding climate change and health among adolescents in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. J. Environ. Public Health 7, 831. doi: 10.1155/2018/9716831

Therkelsen, A. (2010). Deciding on family holidays—role distribution and strategies in use. J. Travel Tour. Market. 27, 765–779. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2010.526895

Threadgold, S. (2012). “I reckon my life will be easy, but my kids will be buggered”: ambivalence in young people's positive perceptions of individual futures and their visions of environmental collapse. J. Youth Stud. 15, 17–32. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2011.618490

Tucci, J., Mitchell, J., and Goddard, C. (2007). Children's Fears, Hopes and Heroes: Modern Childhood in Australia. Abbotsford, VIC: Australian Childhood Foundation.

UN Secretary-General (2013). Intergenerational solidarity and the needs of future generations: report of the Secretary-General. Available online at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/756820 (accessed August 31, 2023).

United Nations (1987). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development - Our common future. Available online at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/133790?ln=en (accessed August 31, 2023).

United Nations (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child (accessed August 31, 2023).

Uysal, M., Sirgy, M. J., Woo, E., and Kim, H. (2016). Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 53, 244–261. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.013

Wals, A. E., and Schwarzin, L. (2012). Fostering organizational sustainability through dialogic interaction. Learning Organiz. 19, 11–27. doi: 10.1108/09696471211190338

Wiek, A., Withycombe, L., and Redman, C. L. (2011). Key competencies in sustainability: a reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 6, 203–218. doi: 10.1007/s11625-011-0132-6

Yang, M. J. H., Yang, E. C. L., and Khoo-Lattimore, C. (2020). Host-children of tourism destinations: Systematic quantitative literature review. Tour. Recr. Res. 45, 231–246. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2019.1662213

Yung, R., and Khoo-Lattimore, C. (2018). “Same, same, but different: the influence of children in asian family travel,” in Asian Cultures and Contemporary Tourism, eds. E. C. L. Yang and C. Khoo-Lattimore (Singapore: Springer Singapore), 61–78. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-7980-1_4

Zurba, M., Stucker, D., Mwaura, G., Burlando, C., Rastogi, A., Dhyani, S., et al. (2020). Intergenerational dialogue, collaboration, learning, and decision-making in global environmental governance: the case of the IUCN intergenerational partnership for sustainability. Sustainability 12, 498. doi: 10.3390/su12020498

Keywords: children, drawing, decision-making, futures, temporal orientations, island tourism, Indonesia

Citation: Kwong YMC (2024) Engaging children's voices for tourism and marine futures through drawing in Gili Trawangan, Indonesia. Front. Sustain. Tour. 2:1291142. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2023.1291142

Received: 08 September 2023; Accepted: 11 December 2023;

Published: 08 January 2024.

Edited by:

Elaine Chiao Ling Yang, Griffith University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Roxane De Waegh, Auckland University of Technology, New ZealandAntonia Canosa, Southern Cross University, Australia

Copyright © 2024 Kwong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yim Ming Connie Kwong, Y29ubmllLmt3b25nQGxlaWJuaXotem10LmRl

Yim Ming Connie Kwong

Yim Ming Connie Kwong