- 1Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, Chengdu, China

- 2Geography and Tourism Studies, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada

- 3Department of Human Dimensions of Natural Resources, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, United States

Despite lacking clear historical significance, the appeal pandas have to the people of China has played an integral role in the emergence of the country's cultural identity and ideals. Few studies have explored the giant panda due to the ongoing dialogue between the West and China, which, according to Edward Said, is permeated with imperialist, colonial, and orientalist flavors. In 1869, the French missionary Armand David encountered a dead specimen of a giant panda in Baoxing, Sichuan, which sparked the beginning of this dialogue. David shipped the skin to Paris, where the animal was named and aesthetically recreated for the first time for Western audiences. In this paper, we approach the giant panda as a dark tourism attraction embodying a process of making and remaking Chinese national identities over the past two centuries. Using “virtual curating” to study the Giant Panda Museum located at the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, we demonstrate that the giant panda, which has achieved iconic status in China, represents a national history that is dark, backward, and based on suffering and death. We argue that understanding the giant panda's history as a dark tourism attraction provides an ethical vantage point from which to perceive tourist-panda relationships.

1 Introduction

In his 12-year stay in China, the French missionary and naturalist, Armond David (1826–1900), stationed at the Dengchi Valley Cathedral in the mountains northwest of Chengdu in Sichuan, first encountered the skin of a giant panda on March 11, 1869. Wishing to see a giant panda specimen, hired hunters brought the body of a young panda bear to David, which they killed for easier transport. A well-trained scientist, David recognized the value of the giant panda, and sent the skin back to Paris, where the giant panda, a female, was presented for the first time in Europe at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris (Nicholls, 2014). On 13 April 1929, Theodore and Kermit Roosevelt were the first foreigners to shoot a panda, being the catalyst for several giant panda trophy hunts sponsored by American museums (World Wildlife Fund, 2020).

Over 140 years later, when Henry Nicholls was collecting information for his book, The Way of the Panda: The Curious History of China's Political Animal (Nicholls, 2010), the U.K. writer paid a visit to Dengchi Valley Cathedral. Staying in the same room occupied by David, Nicholls fantasized over a table in the room in which David “carried the cold, stiff body [of the panda] into the room that the resident priest, Father Dugrité, had put at his disposal. He laid it gently on his worktable, picked up his scalpel and quickly set to work” (p. 11), referring to it as “a most excellent black-and-white bear” (p. 9). For Nicholls, the moment symbolized a significant moment for the exchange between the West and China, as the missionary explored the local culture and inaugurated a scientific discovery. Following these events, Nicholls turned to the panda skin's journey to the West and Scientific world, narrating in detail how David packed up the panda's skin and shipped it to France once dissected. Nicholls noted that David wrote a letter to Alphonse Milne-Edwards, his zoological contact at the museum, urging him to publish a brief description of the panda to establish his priority in the discovery of the animal. The letter proposed the Latin name for the animal (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) and described its unique markings. As the name was eventually adopted, David's specimen joined the remains of millions of dead animals in a subterranean vault beneath the Paris Museum.

Through David's scientific gaze, the giant panda was a rare and beautiful species that needed to be discovered (David continued to make scientific discoveries in China, including Père David's deer, Elaphurus davidianus). In contrast, the contemporary writer Nicholls was drawn to the history of the giant panda and how it has emerged as a political and cultural icon. Missing in these accounts, however, is the story of how the iconic flagship species for wildlife conservation came to be intertwined with the contemporary human civilization through its death. How could the death of the protagonist, the giant panda, become only a secondary feature to the primary narratives based on scientific discovery, history, and later celebration of this species?

This paper is not an attempt to address the untold stories behind the first giant panda's death and its recognition by the West. Scholars have already inquired about the history and practice of animal taxidermy and remains and placed the practice as an inevitable moment of encounter between culture and nature (Milgrom, 2010; Poliquin, 2012; Aloi, 2018; Bezan and McKay, 2021). Instead, we address the panda's death and its representation in the local Chinese community and ask how the panda and its past has become an embodiment of interactions between the West and East where science, colonial expansion, and the construction of national identities are intricately intertwined. We show that giant panda tourism has been a process through which a history of being colonized, exploited, and cultured is materialized and aestheticized as tourist spectacles to be consumed in China. It is through these processes that we will learn how China's cultural gravitation toward the giant panda can be tied to dark tourism, defined as “visitations to places where tragedies or historically noteworthy death has occurred and that continue to impact our lives” (Tarlow, 2005, p. 48) or “a quest to experience a disaster from a safe place” (Martini and Buda, 2020, p. 684). We show that, from an unknown beast in the forest of Sichuan to a nation's treasure, the rise of giant panda tourism should also be described as a nation's inevitable reconciliation with a history of dark memory.

2 Giant panda as dark attraction

2.1 Giant panda and dark tourism

As a curious intersection between tourism and death, dark tourism is steeped in symbolism, performed by tourists to reinterpret death or visit representations associated with death. What is believed to be dark can serve to educate visitors (Cohen, 2011; Stone, 2013; Biran and Poria, 2014), seek thrill or curiosity (Seaton, 1996; Yan et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2018; Kunwar and Karki, 2019), find meaning (Collins-Kreiner, 2016; Lennon, 2017; Isaac and Platenkamp, 2018), and bridge cultural gaps (Stone, 2005, 2006; Ashworth and Isaac, 2015). In their exploration of the curious relationship between tourism and death, Stone and Sharpley (2008) took a sociological approach, showing that dark tourism can provide a means of confronting death in modern societies. For these scholars, dark tourism provides order to the often meaningless event of death through commodification and visitor experience, reinforcing death's validity and inevitability through spectacle and the gaze.

In the story of the first panda, we observe three distinctive moments transforming her death. The first was justified by science when David's discovery of the first giant panda was embedded in Europe's colonial expansion and dominance of scientific knowledge. Second, Nicholls' further inquiry of an authentic story about the panda motivated the writer to follow the trace of David as a marker of a dark tourism experience. Third, the first panda's sudden death, permanent exile, and the Chinese community's loss of an animal, however, remained largely untold in this meaning-making process of dark tourism. This paper engages with the third journey—we ask whether this death, for both the animal and the Chinese, can become meaningful through the process of dark tourism.

We argue that the death of the first giant panda became a trigger point for interest among the Western public. In the following decades, Western hunters traveled to Sichuan in search of a mysterious giant panda and many of these journeys led to the death of countless giant pandas. In the 1920s, Roosevelt Jr, whose journey was funded by the Chicago field museum, became the first Westerner to shoot a giant panda. Giant pandas were soon to experience death in many unexpected ways. In 1937, Su-Lin, the panda cub captured by the New York fashion designer Ruth Harkness, made the species' debut live show in Brookfield Zoo and attracted millions of visitors. Su-Lin died of pneumonia in the zoo in the following year while Harkness brought another panda cub, Mei-Mei, to be a companion for Su-Lin. In the following two decades, the image of the giant panda flourished in Western zoos and created superstars such as Chi-Chi—the inspiration for World Wildlife Fund's logo. Chi-Chi left China when she was 3 and lived in Europe for another 15 years until her death. Although giant pandas were becoming star attractions in captive settings in the West, the first captive display of giant pandas in China did not occur until 1955.

2.2 Cuteness and darkness

In her extensive study of China's environmental history and conservation, the American historian Songster (2018) concluded that amid other cute symbolic animals, the giant panda can “command as much diplomatic sway and political force” (p. 4). The historian further argued that the giant panda emerged as a national icon because the animal co-evolved with, and contributed to, Chinese identity. Songster's focus on conservation in China marginalized consumerism, despite the fact that consumerism, as we argue, has been critical in the dark story of the giant panda. In this paper, we suggest that the appeal of cuteness provides a path along which the giant pandas and their darkness are aestheticized in the marketplace.

The giant panda, a celebrity species famous for its unique charm is a spokesperson for cuteness—characterized as adorable, lovable, and attractive (Guo and Fennell, 2023). According to Songster (2018), the giant panda's cuteness was, and is, instrumental in saving the species from extinction. The number of people visiting the Panda Base, as noted above, are a testament to how popular this iconic species is for Chinese nationals as well as international tourists. Consumption of the panda in person, i.e., at the Panda Base, is accompanied by several million people worldwide who consume the panda virtually. The channel has now more than 53 million follows around the world (Ji, 2023).

According to the German philosopher Konrad Lorenz, the attraction to cuteness originates from the human species' appreciation of infantile faces where big eyes, broad foreheads, and chubby cheeks are frequently observed (Dale, 2016). Furthermore, the aesthetic experience of cuteness is closely associated with the celebration of adorable youthful and infantile features and the instinct of nurturance of human beings (Genosko, 2005; Ngai, 2005; Dale, 2017). In the early studies on cuteness, scholars (Hildebrandt and Fitzgerald, 1979, 1983; Lobmaier et al., 2010; Asano-Cavanagh, 2012; Lukacs, 2015) linked the attraction of cuteness to feminine qualities such as warmth, kindness, helplessness, and vulnerability.

More recent studies have shown that the core of cuteness is not merely infantile sweetness. May (2019), for example, suggests that the spirit of cute “can be darker, more uncertain, and more ambiguous” (p. 11) and “often seen through a glass darkly” (p., 49). Harris (2000) and Genosko (2005) believed that, in a consumer society, the aesthetic of cuteness is sadistic, meaning that the cute arouses the instinct to dominate, control, and nurture the other. Nenkov and Scott (2014), in a study on the priming effects of cute products, suggest that cuteness has a whimsical side that can induce consumers' more aggressive behaviors, such as indulgent consumption. In her study of the marketing of the Japanese symbol of cute, Pokémon, into the U.S. market, Allison (2003, p. 386) notes that ambiguity, “in the sense of a murkiness that blurs borders rather than gets contained by them (good/bad, real/fantasy, and animal/human),” is the central theme of cuteness. For Dale (2016), this border-crossing appeal of cuteness helped create the iconic image of man and baby, while the baby snuggled up in a masculine man's arms affectively. From both philosophical and empirical points of view, researchers in different disciplines have confirmed the experience of cuteness as ambiguous and boundary-crossing (Allison, 2003; Ngai, 2005; Borgi et al., 2014).

Rather than appearing to be innocent and sweet on its surface, the darker aspect of cuteness implies control, aggressiveness, and domination. This reflection of the dark side of being cute suggests that the giant panda is not merely an adorable bear that Chinese visitors consume and encounter in zoos or enclosures. Instead, the image of the cute giant panda bear prevailed in the Chinese market precisely because the cuteness, a creation of the consumer market in the mid-nineteenth century of the West (Ngai, 2005), provides an aesthetic process to consume a dark past of a species and a nation. Although the investigation of this aestheticization deserves the space of another lengthy discussion, here we propose a short explanation based on May's theory of cuteness and the concept of dark tourism.

May's (2019) study of the progressive juvenilization of images of Mickey Mouse after the outbreak of the Second World War indicates that the transformation is a result of the fear of the “ever-present threat of violence” (p. 58) in nations' rivalry. The image of the cute Mickey Mouse invokes the awareness of “valiant little survivors” (May, 2019, p. 151) within the hostile and disordered world in which an individual is living. May's discussion suggests that the cute images are aesthetic encounters with disorders and conflicts between the West and East. As the embodiment of cuteness, the giant panda provides a meeting point between the two natures and artfully transforms the experience of imperial dominance and expansion into a shared yearning for maternal care. Once aestheticized, the panda and its cuteness can be readily consumed as commodities in various forms. The tourism industry offers one of the major venues where pandas can be consumed not only as a cute product, but also through its dark history. The popularity of the giant panda in Western zoos in the middle of the twenteeth century is a story of successful commodification of giant panda through its cuteness. We note that China, despite the nation's late response to capitalism and commodification, has come to embrace cuteness as a defining aesthetic category for the giant panda on its market.

In a recent paper, Fennell et al. (2021) suggest that dark tourism, together with several well-established definitions and empirical studies, has a single focus on the human context, despite the fact that animals are consistently entangled and active agents in the tourism experience (see also Panko and George, 2018; López-López and Quintero Venegas, 2021). The Fennell et al. (2021) study shows that because of an entrenched anthropocentric tradition, animals' as active agents in tourism, are suppressed or forgotten in these historical or contemporary experiences. The giant panda is no exception. As tourists “ooo” and “aww” at pandas, what is packaged with these experiences is a form of human domination and control that is framed by pleasure and profit. In the following section, we present data from a virtual curating at the Giant Panda Museum at the Panda Base to further understand how Chinese visitors consume the colonized history and scientific invasion of the giant panda. The image of the cute giant panda, now an icon of Chinese national identity and modernity, allows the Chinese to reconcile with a dark past.

3 Methods

In his investigation of the art of tourism, Tribe (2008) suggests “virtual curating” as an innovative research method to study tourism and its representation of tourists. According to Tribe (2008), virtual curating provides explanations and interpretations to display a collection of carefully grouped and juxtaposed artworks. These methods can help researchers explore “emerging themes of interest which include inter alia idealization, motivation, gender, experience, gaze, surveillance, representation, truth, situatedness and memory” (Tribe, 2008, p. 925). When conducting virtual curating, researchers often assume the role of an art museum curator assembling an art exhibition. Outputs emerge in the form of galleries displaying works in thoughtful arrangements, supported by supplementary material aiding conceptual understanding. Disparate pieces of the exhibit were woven into a unified experience guided by a binding theme. Meaning emerged from interplay between artifacts, where a narrative sequence designed to engage the viewer. We found Tribe's method useful in understanding questions that this paper has raised. The Giant Panda Museum (Figure 1), a place where a collection of scientific education and exhibits is displayed, is itself an artwork addressing the giant panda's past, now, and future. In this light, we consider the Giant Panda Museum a rich site of ideas unfolding the process of aestheticizing the giant panda and its image. Therefore, we virtually studied the museum in the role of curators to answer the main research questions of this paper.

We conducted the virtual curating in two steps. The first step mapped the use of animal skeletons and skins as apparent dark attractions of the museum, based on the Fennell et al. (2021) prototype. The Giant Panda Museum provides several panda specimens to enrich the visitor experience, and the prototype enables an understanding of how and where these specimens have been displayed. The second step considered the making and remaking of a national identity, a key in the museum's interpretation of the integration between the lives of the animal and the Chinese. For both steps, photographs and extensive field notes were taken.

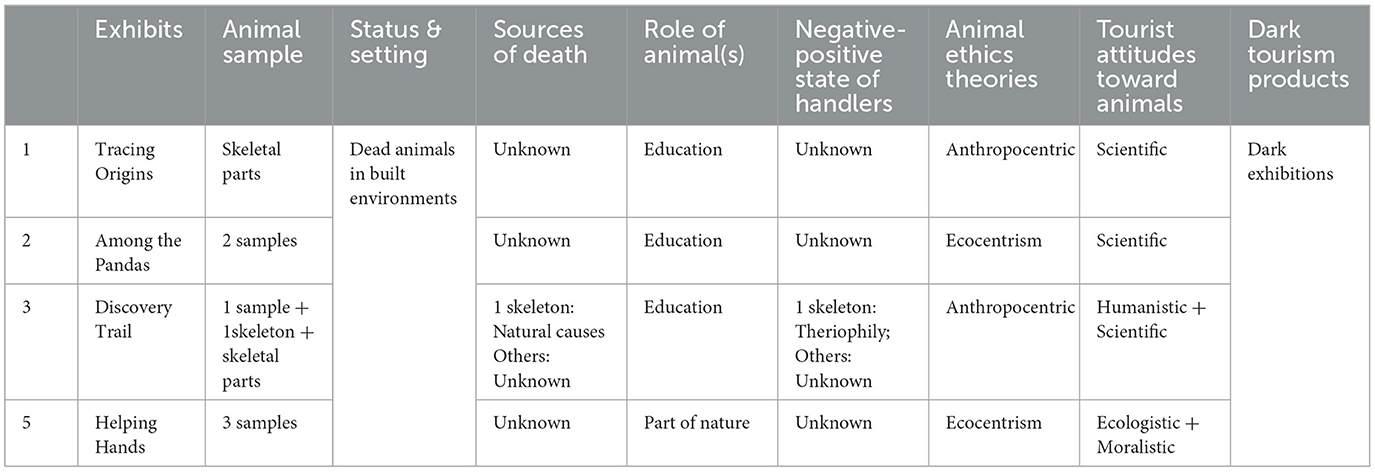

Opened to the public on 3 March 2021, the Giant Panda Museum is the first giant panda-themed museum to provide interactive experiences to visitors. The museum focuses on human-giant panda harmony through immersive exhibitions and virtual interactions. In addition, the museum aspires to cultivate conservation awareness and scientific appreciation among the public. The museum has seven exhibits (Table 1) open to the public, providing a rich collection of unstructured raw data. One of the researchers conducted her one-week fieldwork at the Giant Panda Museum in April 2023, during which notes, photographs and videos were taken. These photos were imported into a computer where three main themes on the giant panda as a dark attraction started to surface.

4 Results

4.1 Skin and skeleton

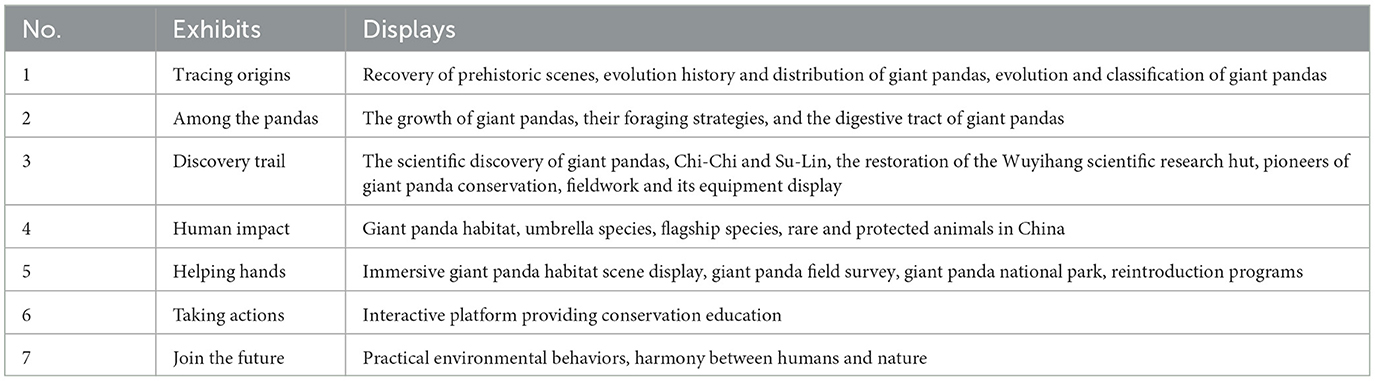

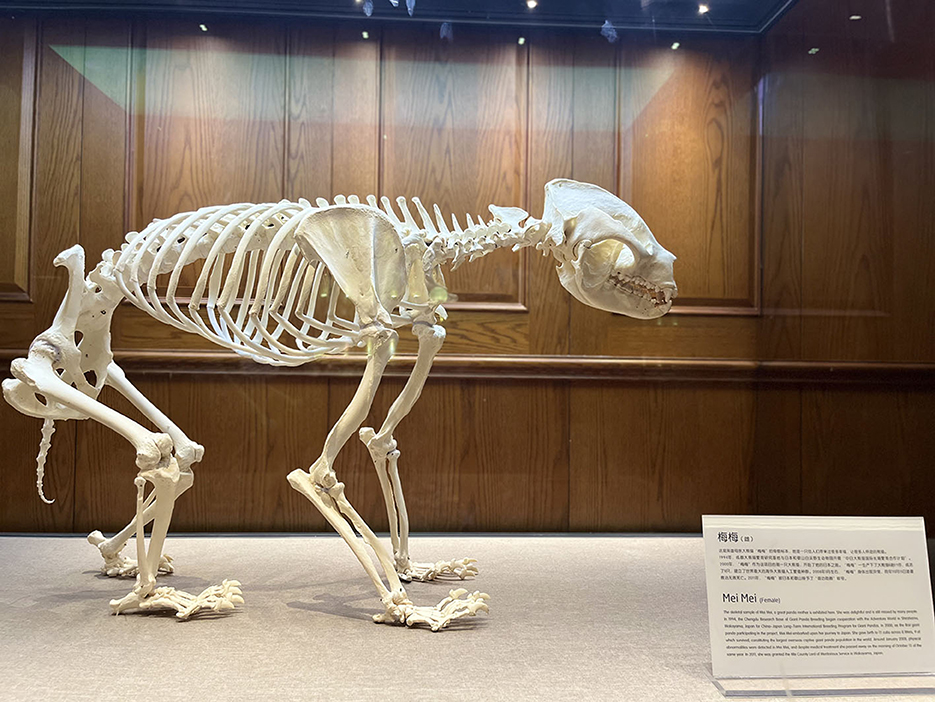

Table 2 summarizes giant panda samples and parts used in the Giant Panda Museum based on the Fennell et al. (2021) prototype. Five samples, one skeleton, and a few skeletal parts are found in different exhibits in the museum. The table demonstrates that giant pandas, as dark attractions at the museum, are contributing to the goal of science education predominately. All panda samples are dark exhibitions aiming at arousing scientific understanding among tourists. The life stories behind the panda samples were not mentioned, with the only exception being the skeleton of panda Mei-Mei found in the Discovery Trail (Figure 2). Notably, several animal samples other than the giant panda are displayed in the museum. These samples serve to attract tourists' attention (e.g., the sample of turtle and pterosaur in Discovery Trail), and are deemed to be naturalistic (e.g., samples of red pandas, leopard, and Chinese bamboo rats in Among the Pandas), and moralistic (e.g., samples of wild ducks and monkeys in Helping Hands) following from the Fennell et al. (2021) prototype.

4.2 Science and history

Exhibit 3, Discovery Trail, is where poster walls display the history of the giant panda. Three stories—David's discovery of the first panda (Figure 3), Harkness' hunting of Su-Lin (Figure 4), and star panda Chi-Chi in London Zoo (Figure 5)—bring the panda's past back to the first wall of the exhibition. The abundance of Western figures and cultures on the first wall show that the West has played a critical role in contributing to the giant panda's discovery and history. In contrast, China held only peripheral roles in all these panda origin narratives, Orientalized as an exotic land harboring hidden treasures and mysteries awaiting Western explorer discovery. In essence, the Chinese remained voiceless in these stories while panda mania consumed the West.

Adjacent to the first wall is an additional exhibit named the “Scientific Discovery Center,” a room decorated by Victorian-style furniture (Figure 6). At first glance, the center brings visitors back to the West, where science is a central theme. English books and animal specimens filled a tall oak shelf. Opposite the furnace is a writing table where a world map unfolds and a feather quill stands. Animal bodies drenched in formalin are found in lines in cupboards next to the furnace. Samples of a turtle and pterosaur hang from the ceiling. The room illuminated how Western science indelibly shaped early giant panda research and narratives according to its own cultural frames and scientific traditions. The scientific research on giant panda did not emerge in an ideological vacuum—questions, experiments, and publications alike reinforced Western scientific authority over the animal.

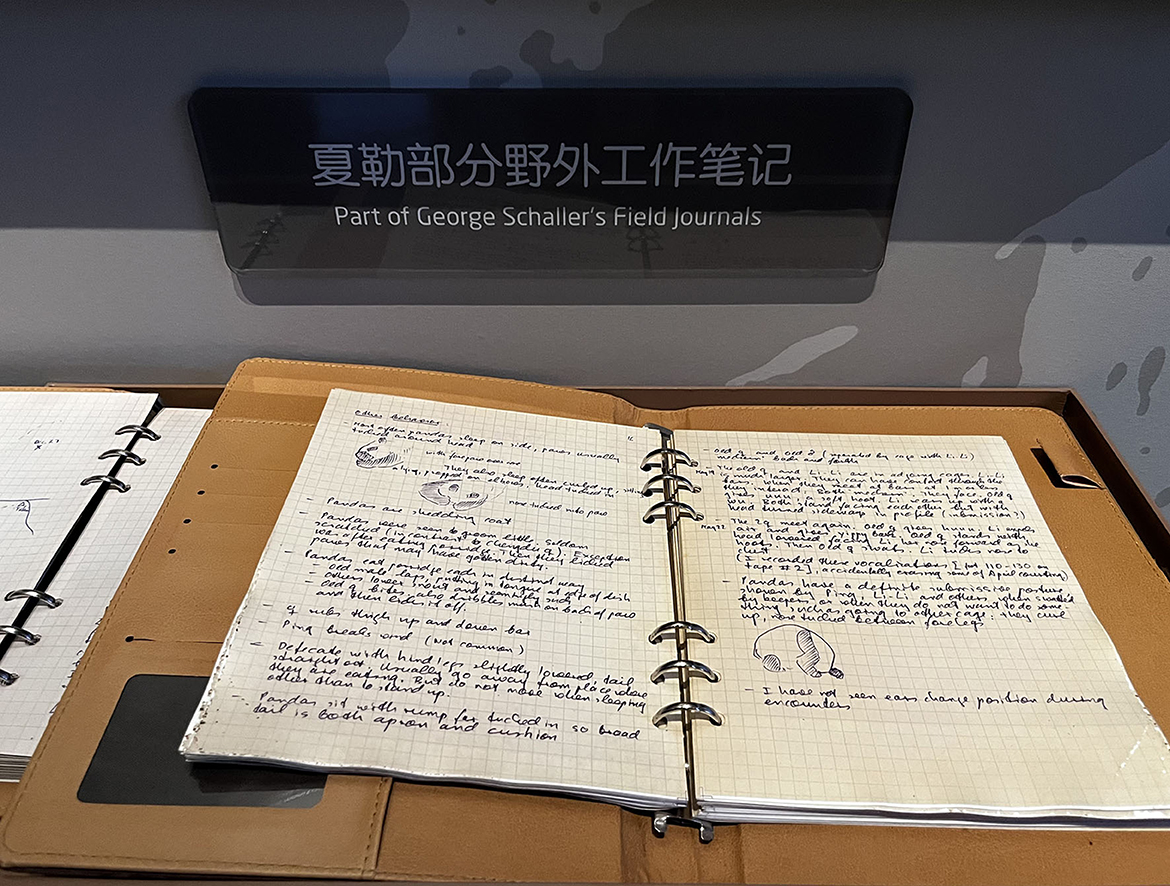

The second wall of the exhibit begins with the first generation of Chinese researchers of giant pandas (Figure 7). According to Kleiman and Seidensticker (1985), a detailed field study of the giant panda's wild habitat was only available in the 1960s when China initiated surveys and a census to study the species. The first giant panda field research station was a simple pitched tent, where researchers faced great hardship and limited resources in their pioneering efforts to study the bears within their natural habitat. In a landmark moment for international panda research, the Chinese government partnered with WWF in 1980, enabling renowned biologist George Schaller to collaborate with leading Chinese scientist Jinchu Hu and his team. At the center of the exhibition, on the second wall, are two copies of George Schaller's field journals (Figure 8).

The third wall illuminates the scientific findings of Hu, his team, and China's early giant panda studies. Fieldwork equipment donated by Hu (Figure 9) is testament to the hardship and harsh conditions endured by the first-generation giant panda scientists. Two photograph galleries provided windows into the extensive fieldwork conducted within the giant panda habitats by both foreign and Chinese researchers, as well as ensuing conservation efforts enacted at ex-situ and in-situ sites. This period signified a major shift from giant panda research dominated by Western scientific traditions to an emerging field where Chinese scientists progressively established their own presence despite the hardship they encountered.

Whereas, exhibit 3 chronicles the giant panda's early scientific discovery by the West and fledgling Chinese research under constrained resources, Exhibit 6 conveys science's maturation into a robust field within China itself. Mimicking facilities at Sichuan's Wildlife Conservation Key Laboratory at the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, Exhibit 6 displays advanced technological equipment and facilities (Figure 10), signifying the important progress achieved. Here the scientific project transformed Chinese citizens into followers of its institutional authority and knowledge power. In contrast to pioneer days of scarcity, here science stands as an image of abundance—its advanced instruments evincing great capacity to unveil panda mysteries.

This narration of giant panda science's development complements the nation's broader quest for identity and shared values. Just as sites of revolutionary struggle now inspire the public, panda research symbolizes conquering past oppression to claim modern Chinese influence. Where Western paradigms once reigned, now stand Chinese scientists wielding global influence. By depicting hardship overcome, the panda story fosters national identity, recasting painful history as progress. As Songster (2018) observes, the panda's iconic status stems from efforts to define China amidst postwar turmoil, its recognizable image speaking to desires for national unity. In transforming panda research from directed expatriation under Western science to self-directed mastery, the nation transcended the shadows of its former oppression.

4.3 Gift shop: where it all ends

At the Panda Museum's end, a gift shop with hundreds of stuffed panda toys and novelties lined up for tourists to take home as further evidence of the commodification of the species. Not unlike captive animal sites around the world, we see the emergence of commodity fetishism, where imperial progress is consumed at a glance through the commodity spectacle (McClintock, 2013). Cute pandas in the gift shop silently mask many darker threads — early panda deaths, Sino-Western clashes, scientific exploitation, and cultural appropriation driven by Western imperialism's backward arrangement of history and events (Chow, 2003). Today, looking at the lined-up panda toys in the gift shop, there is immersed in this display a history of exploitation, colonization, and suffering masked in consumption, which the Chinese now dutifully participate in.

Songster (2018) aligns the giant panda's prominence in contemporary China with the larger story of the rise of the People's Republic of China. The American historian is observant in suggesting that the giant panda also speaks to the “nuanced complexities of its (Chinese) nationhood” (p. 2) and helps to “reintegrate China with the world” (p. 2). We reinforce this observation by arguing that Chinese love for the giant panda emerges through an adoption of Western global industrial and scientific priorities. The Giant Panda Museum showcases this process of transformation and adoption, through the construction of scientific knowledge and its networks and the promotion of commodity culture. The history of the panda—its struggles and sufferings—is not a feature of prominence at the museum.

When one of the researchers was conversing with a Japanese-American scholar at the Panda Base, she, as a Chinese, suggested that Chinese people's enthusiasm toward the panda had always been nationalistic and very often patriotic. When queried about this enthusiasm that had eluded the foreign scholar, the Chinese researcher experienced a sense of bewilderment—the giant panda has long been intricately linked to the nation, making it difficult to fathom how anyone could be unaware of this association. The Chinese researcher experienced a significant moment of realization regarding the varying levels of affection toward the giant panda among individuals who are not of Chinese origin. The panda, despite its adorable and cute appearance, possesses a national history of adversity that may remain unfamiliar to individuals outside of the Chinese cultural context.

While the giant panda's global popularity stems partly from its endearing cuteness, this study problematizes such facile aesthetics. Beyond the soft and cuddly, “darker” complexities underlie panda cuteness for the Chinese—histories of exploitation and colonization readily are readily consumed because tourism industry transformed them into commodity spectacles. We demonstrate how cuteness aesthetically transforms darkness through capitalist consumption, rendering pandas “dark attractions” for Chinese identity-making. Of course, this neither glorifies nor vilifies these as the nation's significant achievements. Rather, with limited alternatives, China embraced Westernization, science, and commodification as survival strategies amidst imperialism and globalization.

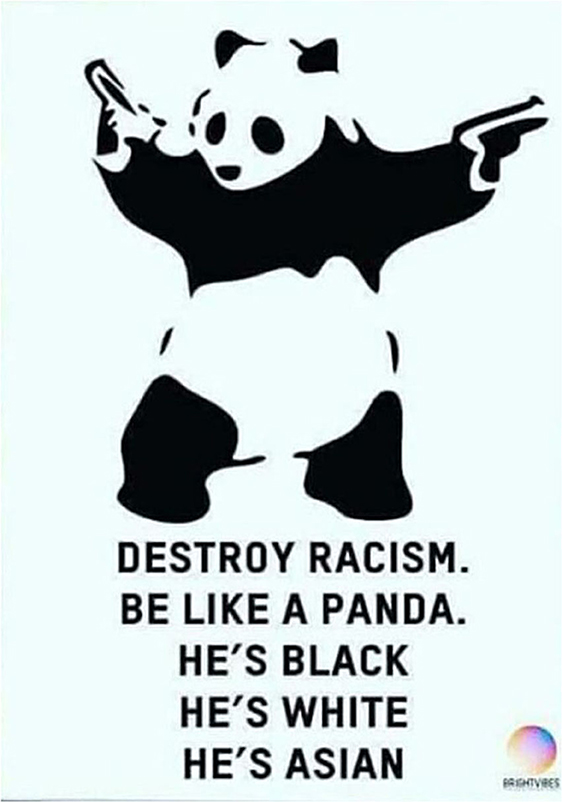

5 Discussion: be like a panda

One of the trending internet memes is an artful interpretation of the giant panda (Figure 11). While the giant panda with two guns in his forelimbs stands at the center of the meme, the text reads: “Destroy racism. Be like a panda. He is black. He is white. He is Asian.” Despite the meme's aim to promote anti-racism and applaud an integration between ethnicities, we note that different ethnicities would have consumed/encountered the giant panda in utterly different ways. In this study, the Chinese have learned to evolve with the image of the giant panda as capitalism, imperialism, and science continue to aestheticize the giant panda. Today, the consumption of a cute giant panda, for the Chinese, means the possibility of witnessing a dark history and reconciling with suffering, oppression, and difficulties that this past bears. In the same way that Western nations conducted scientific investigations and engaged in commodity fetishism, the Chinese have reached a point of confidence to look back at the giant panda with a constructed national identity.

Nevertheless, like the largely untold story of the first giant panda David dissected in Sichuan, the meme “Be like a panda” says little about the experience of the animal itself. In fact, despite the image of the giant panda that can sufficiently embody the difference and integration of all human ethnicities, this animal body does not say a thing about the animal. Nevertheless, this removal of the giant panda from the experience of simply being an animal itself has been the symbolic importance that the animal has received since its discovery. Nicholls (2014) questions in the Epilog of his book whether the giant panda is real or virtual. By virtual, the author means that the giant panda people perceive today has been more or less “tainted” by the “absolutely immense presence of the giant panda in our global culture” (Epilog, para. 4). Songster (2018) shows her understanding of Yaussy's “Endangered Ugly Things” list for promoting awareness of endangered unnoticed, ugly, and obscure species when the giant panda is included because the animal's excessive attention and celebrity status have effectively removed the species from the animal world. In this study, we show that the giant panda has gained a prosperous “afterlife” in scientific investigation and the consumer market, but the animal remains in darkness because of human domination and an uncertain future.

As Girard (1979) observed, violence against others often takes place on many levels. If the object that catalyzed violence is out of reach, the perpetrator will seek out others often found to be vulnerable and in proximity, i.e., “violence seeks and always finds a surrogate victim” (p. 2). Girard continues by suggesting that it is not just humans that are the source and target of this violence but also non-human others. Animals were chosen as “sacrificial lambs” because they displayed human-like characteristics, or because they played a role in the day-to-day activities of human society. As observed by De Maistre (1890), these animals in the latter sense were “the gentlest, most innocent creatures, whose habits and instincts brought them most closely into harmony with man…” (as cited in Girard, 1979, p. 2).

Dolgert's (2012) views on the sacrifice of animals in ancient Greek society is germane to this discussion. He argued that the manner and propensity to sacrifice non-human animals was a matter of politics and community harmony. Even though democracies pretend that they have a commitment to those who are voiceless and sentient, they consume them in all manner of ways in what he referred to as a sacrificial economy. People can use animals in any manner they choose, Dolgert (2012) argued, because they are unable to avenge what he referred to as a criminal death in the sacrificial practices of Greek society. Their non-human status means that they could be sacrificed without guilt and because they were unable to speak and act for themselves. Another relevant theme in Dolgert's work was the concept of pathei mathos. The sacrifice of sentient animals that had physical characteristics similar to humans was seen as a necessary stage in Greek society as a vital source of political knowledge. Dolgert argues that animal suffering played an important civic role in society because the practice of ritually sacrificing animals which acted as a pressure release for a society that often was subject to pent-up aggression, i.e., the community was held in a state of stasis thus preventing civil conflict and unrest. As Fennell (2021) observed in reference to pathei mathos, the animal “scapegoat dies so the community might thrive” (p. 256) under these conditions.

Dolgert (2012) concludes by suggesting that the moral fabric/boundaries of our communities can often be dictated by the political subconscious of its citizens and leaders. By forgetting or anesthetizing the pain and suffering of animals, humans can rationalize or legitimize the many practices that define these communities. As Fennell (2021) argues, the taken-for-granted work that animals do for us in tourism—how we dominate and control animals for purposes of pleasure and profit—become normalized even though animals must endure costs in the process. We argue that the sacrifice of giant pandas, not exactly in the sense described by Dolgert, but in the use of pandas for pleasure, profit, and politics is immersed in a dark tourism narrative. Although the disastrous nature of the giant panda's dark past is to a sufficient degree hidden from the public (and thus covered up by the animal's cultural appeal), the tremendous impact that the giant panda has on both tourists and locals—in different ways of course—can indeed be attributed to the dark nature of the giant panda's cultural emergence in China.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, we follow Spivak (2003) who cautioned that the reclamation of cultural identity for the historically oppressed further re-inscribes the subaltern's subordinate position in society. This study shows how the Chinese and the giant panda, as two species struggling to survive in modern society, have encountered their own dark histories. The Chinese reconfigure a national identity through which the history of oppression and suffering is materialized in scientific achievements and the consumer market. In contrast, although the giant pandas are now living in the spotlight of celebrity and stardom, their own animal identity has experienced a double removal with the human experience remaining as central. This double removal began with the scientific and exploitative approach toward the giant pandas roaming in the forests of Sichuan. The story unfolds through the persistent human/animal boundary that shapes contemporary beings' experiences. In this study, we show that since its discovery in 1869, the giant panda has been an utterly human construction that underlines several critical historical moments rather than an animal with its own inherent quality. In the words of Birke et al. (2004), the giant panda is a process of becoming and doing through the consistent interactions between humans and the natural world rather than a product of the inherent traits of the animal itself.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YG carried out the fieldwork virtual curating. YG and SF wrote the manuscript with support from DF and developed the theoretical formalism. YG conceived the original idea and performed the analysis. DF supervised the project. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allison, A. (2003). Portable monsters and commodity cuteness: Poke' mon as Japan's new global power. Postcol. Stu. 6, 381–395. doi: 10.1080/1368879032000162220

Aloi, G. (2018). Speculative Taxidermy: Natural History, Animal Surfaces, and Art in the Anthropocene. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Asano-Cavanagh, Y. (2012). Expression of“ Kawaii”(“Cute”): Gender Reinforcement of Young Japanese Female School Children. Melbourne, NJ: Australian Association for Research in Education.

Ashworth, G. J., and Isaac, R. K. (2015). Have we illuminated the dark? Shifting perspectives on ‘dark'tourism. Tourism Rec. Res. 40, 316–325. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2015.1075726

Birke, L., Bryld, M., and Lykke, N. (2004). Animal performances: an exploration of intersections between feminist science studies and studies of human/animal relationships. Feminist Theor. 5, 167–183. doi: 10.1177/1464700104045406

Borgi, M., Cogliati-Dezza, I., Brelsford, V., Meints, K., and Cirulli, F. (2014). Baby schema in human and animal faces induces cuteness perception and gaze allocation in children. Front. Psychol. 5, 411. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00411

Chow, R. (2003). Woman and Chinese Modernity: The Politics of Reading Between West and East, Vol. 75. Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Cohen, E. H. (2011). Educational dark tourism at an in populo site: the Holocaust museum in Jerusalem. Annal. Tour. Res. 38, 193–209. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2010.08.003

Collins-Kreiner, N. (2016). Dark tourism as/is pilgrimage. Curr. Issues Tourism 19, 1185–1189. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1078299

Dale, J. P. (2016). Cute studies: an emerging field. East Asian J. Pop. Culture 2, 5–13. doi: 10.1386/eapc.2.1.5_2

Dale, J. P. (2017). “The appeal of the cute object,” in The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness, eds J. P. Dale, J. Goggin, J. Leyda, A. P. McIntyre, and D. Negra (London: Routledge), 35–55.

De Maistre, J. (1890). Eclaircissement sure les sacrifices. Les Soirées de Saint-Pétersbourg 2, 341–42.

Dolgert, S. (2012). Sacrificing justice: suffering animals, the Oresteia, and the masks of consent. Polit. Theor. 40, 263–289. doi: 10.1177/0090591712439302

Fennell, D., Thomsen, B., and Fennell, S. (2021). Animals as Dark Tourism Attractions: A Prototype. EuropeNow. Available online at: https://www.europenowjournal.org/2021/11/07/animals-as-dark-tourism-attractions-a-prototype/ (accessed November 7, 2021).

Fennell, D. A. (2021). “Afterword: on tourism, animals and suffering: lessons from Aeschylus' Oresteia,” in Exploring Non-Human Work in Tourism: From Beasts of Burden to Animal Ambassadors, eds J. Rickly and C. Kline (Berlin: De Gruyter), 253–260.

Genosko, G. (2005). Natures and cultures of cuteness. Visible Cult. Electr. J. Visual Cult. 7, 1–14. doi: 10.47761/494a02f6.b4abc93a

Girard, R. (1979). Violence and the Sacred (trans. P. Gregory). Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Guo, Y., and Fennell, D. A. (2023). What makes the giant panda a celebrity? Celeb. Stu. 14, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/19392397.2023.2223731

Harris, D. (2000). Cute, Quaint, Hungry, and Romantic: The Aesthetics of Consumerism, Vol. 10. New York, NY: Basic Books New York.

Hildebrandt, K. A., and Fitzgerald, H. E. (1979). Adults' perceptions of infant sex and cuteness. Sex Roles 5, 471–481. doi: 10.1007/BF00287322

Hildebrandt, K. A., and Fitzgerald, H. E. (1983). The infant's physical attractiveness: its effect on bonding and attachment. Infant Mental Health J. 4, 1–12. doi: 10.1002/1097-0355(198321)4:1andlt;1::AID-IMHJ2280040102andgt;3.0.CO;2-2

Isaac, R. K., and Platenkamp, V. (2018). Dionysus versus apollo: an uncertain search for identity through dark tourism—palestine as a case study. The Palg. Handb. Dark Tour. Stu. 14, 211–225. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-47566-4_9

Ji, A. (2023). Where are the Boundaries of Panda “Rice Circle”? Xiongmao “Fanquanhua” Bianjia Zainali? Available online at: https://www.163.com/dy/article/I681UGV20514BE2Q.html (accessed June 16, 2023).

Kleiman, D. G., and Seidensticker, J. (1985). Pandas in the wild: the giant pandas of wolong. Science 228, 875–876. doi: 10.1126/science.228.4701.875

Kunwar, R. R., and Karki, N. (2019). Dark tourism: understanding the concept and recognizing the values. J. APF Command Staff Coll. 2, 42–59. doi: 10.3126/japfcsc.v2i1.26731

Lobmaier, J. S., Sprengelmeyer, R., Wiffen, B., and Perrett, D. I. (2010). Female and male responses to cuteness, age and emotion in infant faces. Evol. Hum. Behav. 31, 16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2009.05.004

López-López, Á., and Quintero Venegas, G. J. (2021). “Animal dark tourism in Mexico: Bulls performing their own slaughter,” in Exploring Non-Human Work in Tourism: From Beasts of Burden to Animal Ambassadors, eds J. M. Rickly, and C. Kline (Berlin: De Gruyter), 69–82.

Lukacs, G. (2015). The labor of cute: net idols, cute culture, and the digital economy in contemporary Japan. Posit. Asia Critiq. 23, 487–513. doi: 10.1215/10679847-3125863

Martini, A., and Buda, D. M. (2020). Dark tourism and affect: framing places of death and disaster. Curr. Issues Tour. 23, 679–692.

McClintock, A. (2013). Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203699546

Nenkov, G. Y., and Scott, M. L. (2014). “So cute I could eat it up”: priming effects of cute products on indulgent consumption. J. Consum. Res. 41, 326–341. doi: 10.1086/676581

Nicholls, H. (2010). The Way of the Panda: The Curious History of China's Political Animal. London: Profile Books.

Nicholls, H. (2014). The ‘First' Giant Panda and How it Ended up in Paris. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/science/animal-magic/2014/jan/06/the-first-giant-panda-and-how-it-ended-up-in-paris (accessed January 6, 2014).

Panko, T. R., and George, B. P. (2018). “Animal sexual abuse and the darkness of touristic immortality,” in Virtual Traumascapes and Exploring the Roots of Dark Tourism, eds M. Korstanje and B. George (London: IGI Global), 175–189.

Poliquin, R. (2012). The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing. State College, PN: Penn State University Press.

Seaton, A. (1996). Guided by the dark: from thanatopsis to thanatourism. Int. J. Heritage Stu. 2, 234–244. doi: 10.1080/13527259608722178

Songster, E. E. (2018). Panda Nation: The Construction and Conservation of China's Modern Icon. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Spivak, G. C. (2003). Can the subaltern speak? Die Philos. 14, 42–58. doi: 10.5840/philosophin200314275

Stone, P. (2006). A dark tourism spectrum: towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibitions. Tour. Int. Interdis. J. 54, 145–160.

Stone, P. (2013). Dark tourism scholarship: a critical review. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hospit. Res. 7, 307–318. doi: 10.1108/IJCTHR-06-2013-0039

Stone, P., and Sharpley, R. (2008). Consuming dark tourism: a thanatological perspective. Annal. Tour. Res. 35, 574–595. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2008.02.003

Tarlow, S. (2005). Death and commemoration. Indust. Archaeol. Rev. 27, 163–169. doi: 10.1179/030907205X44457

Tribe, J. (2008). The art of tourism. Annal. Tour. Res. 35, 924–944. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2008.07.003

World Wildlife Fund (2020). Wanted Alive: Giant Pandas in the Wild. Available online at: https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?84980/Wanted-Alive-Giant-Pandas-in-the-Wild

Yan, B. J., Zhang, J., Zhang, H. L., Lu, S. J., and Guo, Y. R. (2016). Investigating the motivation–experience relationship in a dark tourism space: a case study of the Beichuan earthquake relics, China. Tour. Manage. 53, 108–121. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.09.014

Keywords: giant panda, animals as dark tourism attractions, national identities, iconic species, Chinese visitors

Citation: Guo Y, Fennell D and Fennell S (2023) Be like a panda: reconstructing national identities through China's iconic species. Front. Sustain. Tour. 2:1247407. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2023.1247407

Received: 26 June 2023; Accepted: 02 October 2023;

Published: 15 November 2023.

Edited by:

Julia N. Albrecht, University of Otago, New ZealandReviewed by:

Dallen J. Timothy, Arizona State University, United StatesDaniel Olsen, Brigham Young University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Guo, Fennell and Fennell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yulei Guo, eXVsZWkuZ3VvQHBhbmRhLm9yZy5jbg==

Yulei Guo

Yulei Guo David Fennell

David Fennell Sam Fennell

Sam Fennell