95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

METHODS article

Front. Sustain. Tour. , 27 June 2023

Sec. Social Impact of Tourism

Volume 2 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsut.2023.1172034

This article is part of the Research Topic Children in Tourism View all 7 articles

A correction has been applied to this article in:

Corrigendum: Online photovoice to engage indigenous Cook Islands youth in the exploration of social and ecological wellbeing amidst a global disruption

Photovoice is a participatory action research method that aims to include the voices of groups by enabling people to record and reflect on their knowledge of issues they consider important. Drawing from critical pedagogy, feminist theory, and community-based approaches to document research, photovoice involves participants as collaborators by using photographs that participants take themselves. Engaging the participants in conversations regarding their photographs facilitates agency in the research process and provides valuable insights into the views, experiences, and knowledge of participants. Originating in the public sector as a method for assessing health needs, the use of photovoice has since gained popularity as a tool for examining perceptions regarding changes in the social and natural environment, and for exploring human-environment interactions. This paper reviews the use of photovoice as a research method to engage indigenous youth in the small island community of Rarotonga, Cook Islands for the exploration of ecological and social wellbeing during disaster times. Amidst the global disruption ensued by the COVID-19 pandemic, indigenous youth participants explored the responses and adaptations of their community to changes in the social and ecological environment of their island home. Given the associated lockdown measures and travel restrictions, photovoice interviews were conducted via Zoom, an online videoconferencing platform. By integrating the photovoice method with advanced online communication systems, the research team based in Auckland, New Zealand was able to collect data remotely while facilitating meaningful engagement with indigenous youth participants across geographic and cultural borders. The use of online photovoice via Zoom was shown to be an empowering and inclusive method for the engagement of indigenous youth and the promotion of collaborative, cross-cultural research partnerships for the exploration of social and ecological wellbeing during a global disruption.

Indigenous people are defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “populations or communities that live within, or are attached to, geographically distinct traditional habitats or ancestral territories, and who define themselves as being part of a distinct cultural group, descended from group present in the area before modern states were created and current borders defined. They generally maintain cultural and social identities, and social, economic, cultural, and political institutions, separate from the mainstream or dominant society or culture” (World Health Organization, 2007). Since the late 18th century, indigenous peoples in Pacific Island Countries (PICs) have been challenged through various encounters with early explorers, missionaries, traders, and other more recent agents of colonialism, development, and capitalism (Jolly, 2007). Foreign knowledge of the Pacific has been used to create imaginaries of vulnerability in terms of what they lack; not only the absence of development, civilization, or growth, but also in the perceived deficiencies of scale, isolation, and dependency (Kothari and Arnall, 2017). For example, in a study that explored how the rise of neoliberal growth strategies in the 1980s and 1990s impacted various Pacific Islands societies, Hooper (1993) observed that traditional systems of rights to land and kinship networks were judged as irrational commitments to family which limited the potential for useful development. A similar study points out that the export-growth strategies and neoliberal development discourses portray subsistence economies as “primitive,” “backwards,” and “stagnant,” and should therefore be replaced with modern techniques for the sake of economic growth (Fry, 2019). Gegeo (2001) further noted that cultural events, which depend on traditional agricultural practices, were regarded as wasteful exchanges of valuables resources.

While some scholars consider that the Eurocentric lens, which perceives peoples and places in terms of their economic development potential, enabled the growth and success of small island economies in the Pacific (Croes et al., 2020), others claim that it also led to a series of unforeseen consequences and negative impacts to the social and ecological wellbeing of Pacific Islands people (Diedrich and Aswani, 2016). For instance, studies demonstrate how neoliberal growth strategies contributed to the erosion of robust social networks that enabled the exchange of foods and agroecological knowledge (Newsom and Wing, 2004; Temudo and Abrantes, 2013). In terms of the adverse impacts of tourism as an economic development strategy in PICs, research reveals how the growth of international tourism sectors resulted in environmental change, commodification of nature and culture, food insecurities, and conflict with local people possessing different values, interests and priorities (Kothari and Arnall, 2017). Studies further demonstrate how neoliberal development strategies led to biodiversity loss (Campbell, 2014) and the deterioration of soil health and land productivity (Gould et al., 2015), which further led to an increasing dependence on non-nutritious imported food (Marrero and Mattei, 2022). Evidently, PICs were encouraged by colonial administrators and Christian missionaries to transform their subsistence-based communities to monetized societies in order to participate in a globalized economy and stimulate economic growth and development (Connell, 2010).

The influence of foreign policies in PICs, however, is not limited to development literature. Environmentalists and conservationists appropriated the island imagery of primitive societies in need of modernization and economic development by adding a new layer of perceived environmental vulnerabilities to meet their sustainable development agenda (Scheyvens and Momsen, 2008). Indeed, there is a great wealth of research that recognizes the role of physical characteristics and climatic processes in determining the vulnerability of Pacific Islands societies to exogenous disruptions (Veron et al., 2019; Filho, 2020; De Scally and Doberstein, 2022). In the Pacific region, some of the large-scale impacts of climate change include increased variability in rainfall events (McGree et al., 2014), stronger and more frequent tropical cyclones (McMichael et al., 2019), rising sea-level (Kulp and Strauss, 2019), increase in air and sea surface temperatures (De Scally and Doberstein, 2022), and changes in regional climatic systems, particularly the South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ) and El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) (Cai and Marks, 2021). Climate scientists, sociologists, economists, marine biologists, agronomists, ecologists and political scientists have all recognized that these large-scale changes are expected to have significant implications for nearly every sector in PICs, including tourism, fisheries, agriculture, human settlements, freshwater resources, and health (De Scally and Doberstein, 2022).

However, by over-emphasizing the physical features of small islands, the concept of vulnerability is merely understood as the result of an island's exposure to hazards. Consequentially, limited attention is given to the social and cultural characteristics of Pacific Islands people in determining their resilience and adaptive capacity to external disruptions (Rivas, 2019). Scholars argue that focusing on the physical source of a disruption leads to the implementation of externally designed technocratic solutions, which are removed from the everyday lives, needs and concerns of island people (Nunn et al., 2020). Furthermore, many of these environmental conservation, sustainable development, and climate change policies have been proposed and implemented from a predominantly scientific worldview, in which climate change is seen as a science-informed issue, rather than a faith-based challenge (Luetz and Nunn, 2020). Considering the overwhelming prominence of Christianity in PICs, it has been argued that such secular interventions fail to acknowledge the powerful influence of spirituality (Nunn et al., 2016; Scott-Parker et al., 2017; Weir et al., 2017). Nevertheless, as a result of the dominant foreign representation of Pacific Islands societies as socially, economically and environmental vulnerable, today PICs are regarded as the most vulnerable societies to exogenous threats and disruptions (Uitto and Shaw, 2016).

Scholars argue that the continuous emphasis on the agency of environmental and socio-economic threats found within disaster studies in the context PICs, rather than a focus on the human agency of Pacific islands people, works to re-enforce the victimhood narrative by representing islanders as passive in the face of disruptive change (Biggs et al., 2011; DeLoughrey, 2019). On a similar note, literature on social-ecological change in indigenous and marginalized communities demonstrate that indigenous peoples and their knowledge are often excluded from debates and decision-making processes that concern the social and ecological wellbeing of their communities (Agrawal and Chhatre, 2006; Adger et al., 2011; Biggs et al., 2011). From this position, scholars argue that externally born representations of PICs have limited explanatory power because they arise from a western understanding of success and wellbeing, which often does not neatly translate to local cultural constructs of wellbeing (Scheyvens et al., 2020). Furthermore, these ahistorical and reductionist framings of PICs as inherently vulnerable to exogenous change fail to represent how island societies make meaningful lives for themselves through their own perceptions of social and ecological wellbeing (Barnett and Waters, 2016). As the concept of wellbeing becomes a deeper focus of social-ecological systems research, conservation, socio-economic development, ecosystems-based management, and disaster studies (Summers et al., 2012; Milner-Gulland et al., 2014; Breslow et al., 2016; DeLoughrey, 2019; Scheyvens et al., 2020), the need for in-depth qualitative studies that enable a deeper understanding of indigenous framings of wellbeing are becoming increasingly vital (Daw et al., 2011; Cruz-Garcia et al., 2017; Masterson et al., 2018). Furthermore, as noted by influential Tongan anthropologist, Epeli Hau'ofa, it is imperative to consider different representations of Pacific Islands societies not just because of their geopolitical and discursive hegemony but because island people have, in part, come to see themselves through the lens of outsiders (Hau'ofa, 1994).

In addition to the socio-economic and environmental impacts of colonial interventions and the promulgation of neoliberal development policies, studies demonstrate how colonization and Christianisation negatively impacted the traditional ways of learning and education systems of Pacific Islands people (Taufe'ulungaki, 2004; Thaman, 2008; Johansson-Fua, 2016; Taumoefolau, 2019). For instance, Thomas (1993) points out that mission activities are responsible not only for the expansion of Christianity in the region, but also for the introduction of formal schooling and the forced application of the English language. The fear of losing one's language is a common theme across the Pacific region (Maia et al., 2018; Glasgow, 2019). According to McCaffery and McFall-McCaffery (2010), the maintenance of language is critical for Pacific communities, especially for those whose languages have been classified as endangered, such as Cook Islands Māori and its dialects which have been replaced with the increasing use of the English language. Furthermore, language has been recognized as one of the most important practices through which cultural production takes place (Corson, 1998; Pacini-Ketchabaw and Armstrong de Almeida, 2006; Grace and Ku'ulei Serna, 2013). From this position, both indigenous and non-indigenous scholars argue that the introduction of literacy and the forced application of English transformed the oral traditions of Pacific Islands societies, thereby marking one of the most significant cultural and social changes in the region to date (Smith Tuhiwai, 1999; Hau'ofa, 2008; Thaman, 2008; Vaka'uta, 2011; Lange, 2017). In addition to the practice of language, the provision of education has been regarded as having an important role to play in the preservation of local customs and traditions and in the development of a national identity (Kennedy, 2019).

In observing the impacts of loss of language and the ways of learning across the Pacific, the Tangata Whenua (Indigenous people of Ateaora New Zealand) developed a programme commonly known as the “the language nest,” which aims to revitalize the Māori language in early-childhood education (Benton, 1989; Chambers and Saddleman, 2020). The language nest programme, which originated in the 1980s, was then accelerated by women in the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau, Tonga and Samoa who recognized the consequences of the loss of their language and culture, and thus took action to ensure that not only their languages would be passed on to their children, but also key social-cultural values that promote indigenous ways of learning (Glasgow, 2019). Despite the efforts of Pacific communities, and Pacific women in particular, the languages of the Cook Islands, Niue and Tokelua continue to decline rapidly. In 2013, these languages were declared inter-generationally extinct in Aotearoa New Zealand, where the majority of the respective populations reside (McFall-McCaffery and Cook, 2016).

Today, indigenous youth across various Pacific Islands societies are constantly reminded of their colonial past in the classroom, on social media, on television, through persisting stereotypes, and through the continued pressures of modernization and globalization (Armstrong et al., 2021). For example, history classes in the Cook Islands continue to be taught through the perspective of European domination, thereby perpetuating the long-standing patterns of power that emerged during the colonial administration (Glasgow, 2019). This in turn influences the self- image and aspirations of indigenous peoples through a process known as the sociality of coloniality (Maldonado-Torres, 2013). In recognizing the impacts of coloniality on indigenous youth in Rarotonga, Cook Islands, a local non-governmental organization by the name of Korero o te‘Orau seeks to improve the wellbeing of its indigenous peoples and their environment through the revitalisation of traditional knowledge and holistic education for indigenous youth (Cook Islands Government, 2020).

Since 2017, Korero o te‘Orau's youth development programs tui'anga ki te Tango1 have offered local youth opportunities to reconnect with their culture while learning about environmental science. This study collaborated with Korero o te‘Orau to engage indigenous youth participants in the exploration of social and ecological wellbeing during the global disruption of COVID-19. The objective is to foster a deeper and holistic understanding of complex human-nature relationships in indigenous Pacific societies, and how these interactions translate into vulnerabilities or opportunities that can enhance the resilience of PICs to exogenous disruptions. Given the international travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to the social hierarchies found across various Polynesian societies which perpetuate the exclusion of marginalized groups such as the youth, this study developed an innovative and culturally responsive method to engage indigenous youth and collect qualitative data remotely by modifying the photovoice technique for online usage.

The paper begins by critically discussing indigenous Pacific understanding of wellbeing to demonstrate the lack of representation of indigenous youth perspectives within this body of literature. The article then provides an explanation as to why indigenous youth are typically excluded from research due to social and cultural values entrenched in traditional Pacific societies. It then builds on and contributes to the burgeoning literature on photovoice as a youth-friendly, empowering participatory research tool that emphasizes social inclusion and social justice by including the voices and perspectives of marginalized groups in decision-making. This is followed by a discussion on the adaptation of photovoice for online use to conduct remote qualitative data collection amidst the global disruption of COVID-19. The methods section includes a descriptive account of the research setting, the development of local research partnerships, the recruitment process, and data collection. A brief summary of the results is threaded through the photovoice stages of photograph production and discussion, highlighting the trade-offs, challenges and potentials of online photovoice. The article concludes by evaluating the potential of photovoice as an online participatory visual method for the engagement of indigenous youth in the exploration of social and ecological wellbeing during disaster times.

Over the last two decades, a growing number of indigenous Pacific scholars have challenged Oceanic researchers to consider how western educational legacies, their philosophies, ideologies, and pedagogies have neglected the way Pacific peoples communicate, think, and learn for over 200 years (Smith Tuhiwai, 1999; Thaman, 2003; Taufe'ulungaki, 2004; Hau'ofa, 2008; Le Fanu, 2013; Johansson-Fua, 2016; Toumu'a et al., 2016; Taumoefolau, 2019). Within this body of knowledge, commonly referred to as “decolonization of Pacific studies and mind,” indigenous scholars critically reflect on the processes whereby colonial ideologies sought to replace the values and belief systems that underpin the indigenous ways of knowing, their views of who they are, and mainly, what they consider important to teach and learn (Thaman, 2003). By drawing from studies that explore notions of wellbeing through the lens of indigenous Pacific Islands people, this section aims to develop a deeper understanding of the multifaceted and relational concept of wellbeing.

In contrast to the European philosophy where the self is positioned in opposition to the other, and where private ownership is prioritized over communal living, Pacific islanders are deeply relational people, where their identity and being are defined from the collective (Thaman, 2008). This multidimensional understanding of wellbeing in Pacific Islands societies is centered on notions of reciprocity that refer to individuals, communities, the environment and the relationships that binds them together (Taufe'ulungaki, 2004; Te Ava and Page, 2020; Tu'itahi et al., 2021). For example, one of the most common words used in many Pacific cultures is the word fonua in Tongan, or vanua in Fijian, which refers to both the land and the people (Taumoefolau, 2019). This understanding of wellbeing from a communal point of view focuses on social responsibilities and upholding duties of care to the community and the land (Fletcher et al., 2021). From this point of view, land is understood to play an important cultural and spiritual role for many Pacific Islands societies.

Both indigenous and non-indigenous Pacific scholars have recognized the importance of land because it is indicative of prestige, wealth, heritage, security, food, and identity; it represents people's birthplaces and places of origin (Crocombe, 1973; Bonnemaison, 1985; Tabe, 2011; Campbell, 2014). To Pacific islanders, their “small remote islands” which are commonly perceived as vulnerable to exogenous shocks through the lens of foreign scholars, are considered to be complex heritage sites that are comprised of ancestorial resources and cultural knowledge, and represent a continuity with the past (Steiner, 2015). Hence, for Pacific Islands societies, and many marginalized indigenous peoples around the world, the act of being displaced from their physical environment is inherently linked to the sense of loss of traditional knowledge and practices, language, culture, and ultimately, identity (Klepp and Herbeck, 2016).

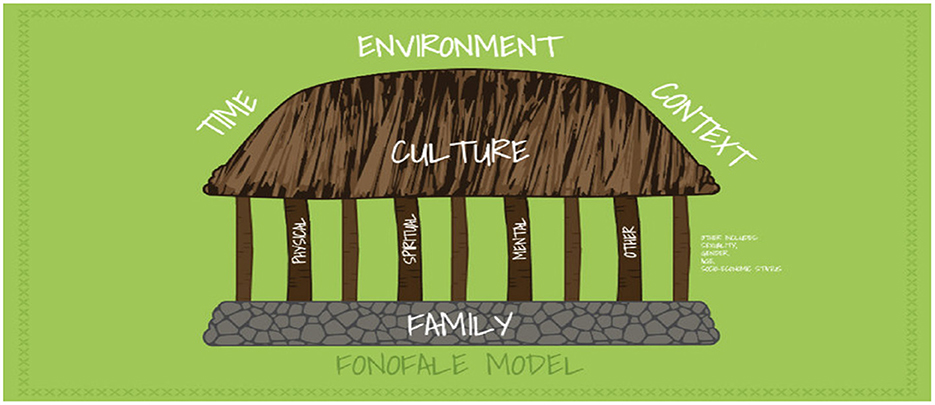

In addition to emphasizing the relationship between land and people, Pacific models of wellbeing are comprised of multiple individual elements from many small island nations, including Samoa, Tonga, the Cook Islands, and Niue (Pulotu-Endemann and Tu'itahi, 2009). For instance, the fonofale model of health (Figure 1) represents five key dimensions of wellbeing. The roof represents one's culture, beliefs and value systems which provides protection and shelter. The floor represents the family, including relatives and extended family members. The roof and foundation are then supported by four pillars, which represent the spiritual, mental, and other aspects of wellbeing such as sexuality, socio-economic status, and gender (Pulotu-Endemann, 2001). Finally, the fale (house) is surrounded by a cocoon or boundary that situates the five dimensions of wellbeing within its own physical environment, time and context (Pulotu-Endemann, 2001). In this way, the fonofale model demonstrates the importance and influence of external factors in shaping the multifaceted concept of wellbeing. More importantly, by acknowledging that wellbeing exists within a physical, social and temporal context, the fonofale model recognizes that wellbeing is both dynamic and subjective.

Figure 1. The Fonofale model of health (Pulotu-Endemann, 2001).

In the Cook Islands, the five notions of wellbeing have been described by Pacific scholars as the following: kopapa—physical wellbeing; tu manako—mental and emotional wellbeing; vaerua—spiritual wellbeing; kopu tangata—social wellbeing; aorangi—total environment, that is, how society influences you and the way individuals are shaped by their environment (Aldinger and Whitman, 2009; Futter-Puati and Maua-Hodges, 2019). To help elucidate how the five dimensions of wellbeing are interconnected, indigenous Cook Islander researchers have applied the tivaevae model (Figure 2). The tivaevae is a large handmade quilt decorated with an array of different cloths, colors, and designs that represent the Cook Islands environment—flowers, leaves, emblems, landscapes, ocean and sky (Te Ava and Page, 2020). The crafting of the tivaevae is a collaborative effort between a group of people, typically women, who aim to create a picture that tells a story. This picture often represents a traditional family-held pattern (Maua-Hodges, 2000).

Figure 2. The five Cook Islands values in Maua-Hodges' tivaevae model (Hunter et al., 2018).

According to Rongokea (2001), the tivaevae patterns illustrate the social, cultural, historical, spiritual and religious, economic and political representations of the Cook Islands' culture. The making of the tivaevae also represents the teaching and learning of Cook Islanders' papa'anga (genealogy) and te mārama (the knowledge) which have been passed down from generation to generation (Te Ava and Page, 2020).

Evidently, there is a large body of knowledge within the existing literature on indigenous Pacific framings of wellbeing which helps to elucidate the inter-relationships and multifaceted understandings of wellbeing in PICs. However, there are limited studies that explore how indigenous youth in the Pacific perceive the social and ecological wellbeing of their small island community (Armstrong et al., 2021). Furthermore, no literature was found to date that investigates how indigenous Pacific youth perceive social and ecological change in their community during a global disruption.

The term “youth” as defined by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) is as a group of people aged between 15 to 24 years old (United Nations Children's Foundation, 2017). In the context of Polynesian societies, however, scholars suggest that indigenous youth groups can extend up to 34 years old (Larmour, 2009; Poppelwell and Overton, 2022). Regardless of the numerical difference in age, studies that explore the concept of wellbeing from an indigenous lens have found that the perspectives and voices of indigenous youth are often underrepresented in both quantitative survey methods, such as questionnaires, and qualitative research, such as in-depth interviews (Jennings and Lowe, 2013; Paris and Winn, 2013). For example, Paris and Winn (2013) demonstrate that indigenous youth in Canada under the age of 18 are often excluded from traditional health survey methods. Pawlowski et al. (2022) suggest that while culture and language are considered critical components of wellbeing for elders in indigenous communities, little is known about how these determinants compare to the world of video games, social media and memes, which uniquely characterize the life of young people. On a similar note, Ramey et al. (2019) argue that the images and words indigenous youth use to communicate and understand health and wellbeing are rarely explored and documented. Hence, while there appears to be a growing understanding of how indigenous populations perceive wellbeing as a deeply relational and multifaceted concept, the perspective of indigenous youth is largely absent from these local traditional representations. From this position, scholars argue that in order to obtain a holistic picture of the various dimensions of wellbeing in indigenous communities, there needs to be more research that explores wellbeing from the lens of indigenous youth (Jennings and Lowe, 2013; Paris and Winn, 2013; Ramey et al., 2019; Wexler et al., 2019; Pawlowski et al., 2022).

In the context of small island communities in the Pacific, indigenous scholars indicate that the lack of representation from youth participants in research can be linked to cultural barriers and traditional social hierarchies which impede indigenous youth from engaging in meaningful roles, such as decision-making processes for issues they consider important (Taumoefolau, 2019; Siisiialafia-Mau, 2021). Contrary to the popular discourse found within western framings of PICs, in which Pacific Islands societies are represented as homogenous and “romantically traditional” (Cote and Nightingale, 2012), PICs tend to be highly stratified due to traditional social hierarchies (Fotu et al., 2011). To help elucidate the social stratification found within traditional small island societies in the Pacific, scholars have referred to the notion of relationality. Relationality demonstrates the positionality of social relationships which dictates these hierarchal societies (Larmour, 2009; Taumoefolau, 2019). For instance, positionality is based on relationships, so one's positionality is determined by the relationship to others; that is, by how one is viewed by others, not by a code of rights or a process of privatization (Taumoefolau, 2019). The hierarchal relationships within traditional Polynesian societies, such as Tonga, the Cook Islands, and Samoa, place relationships between different social groups and the obligations and responsibilities that follow from these at the center of their socially stratified society (James, 2003). From this point of view, academics argue that traditional social hierarchies in various Polynesian societies dictate the boundaries of social experiences by determining a person's status. And it is these social hierarches that often perpetuate the exclusion of marginalized groups, including indigenous youth (Good, 2012; Lee, 2019).

According to a recent study that explores the lived experiences of indigenous youth in Tonga, Taumoefolau (2019) found that the expressed desire to live in an egalitarian society, where everyone's voice is heard and included in decision making matters, stems from the youths' subjective experiences of living in a highly stratified traditional society. In the Cook Islands, studies found that social hierarchies and nepotistic relationships are contributing to the increasing rates of youth of unemployment, which in turn further stimulates outward migration to New Zealand as indigenous youth hope to escape the social constraints of their small island communities (Dickson et al., 2018). This is particularly the case for indigenous youth in the outer islands that have no rights to land and/or that are born in families that are not well connected (Tiraa, 2006; Pascht, 2011; Marsters, 2016). However, due to the importance of cultural values across PICs, social issues linked to nepotism or exclusionary social hierarchies are challenging to confront (Larmour, 2009). For example, in the Cook Islands, Samoa and Tonga, a predisposition to obey superiors and elders is inherent in both cultures, which was observed in the reluctance of youth to criticize elders (Larmour, 2009; Poppelwell and Overton, 2022).

In summary, cultural values such as reciprocity and family ties appear to present a paradox for the wellbeing of indigenous communities in PICs. On the one hand, social networks and kinship ties are essential for the wellbeing of Pacific Islands people. On the other hand, the obligation to help one's kin and respect traditional values is so deep that these cultural norms are tolerated, even when they perpetuate the exclusion of marginalized groups (Crocombe, 1973; Wickberg, 2013). However, as the president of the Pacific Youth Council in Samoa reminds foreign and indigenous scholars, while there are many studies that discuss the adverse impacts of cultural barriers for the inclusion of youth in meaningful engagement in traditional Pacific societies, youth are still valued and considered important in Pacific Islands communities (Siisiialafia-Mau, 2021). From this standpoint, Siisiialafia-Mau (2021) argues that rather than trying to change certain socio-cultural aspects, indigenous youth need to develop and build their own cultural competency to best navigate around cultural barriers, thereby still respecting their cultural identity while enhancing their agency to increase their empowerment. From this position, the research presented in this article addresses the gap within the existing literature by including the voices of indigenous youth and applying a culturally appropriate technique that respects the traditional values of Pacific Islands societies.

Originally developed to engage Chinese women in health research (Wang and Burris, 1997), photovoice is a participatory research method that is based on the fairly simple principle of using one or more images (or any other type of visual representation, including videos and paintings) during an interview and asking the participants to discuss the images (Catalani and Minkler, 2010). According to Abma et al. (2022), photovoice is considered a youth-friendly method because it is less verbally focused than other qualitative research methods. It offers youth participants an opportunity to take photographs of what they perceive to be important issues, which are then used as a prompt to further a dialogue and articulate their stories (Cook and Hess, 2007). The photographs taken and selected by youth participants represent their interests and enhances their potential to express their opinions on matters they consider important (Sarti et al., 2018) rather than on issues selected by their guardians, elders, or the lead investigator of the respective study. In this light, photovoice can be considered an empowering research method because instead of being the subject of the study, youth participants are in control of the research by holding the camera, taking the photographs, deciding what is captured and seen (and not captured and unseen), and what topics are worth discussing in further detail (Bottrell et al., 2014).

In addition to providing a youth-friendly research method, photovoice has been increasingly recognized as a research technique that emphasizes social inclusion and social justice, and aims to honor participants' rights to express their voices and include their perspectives in decision-making processes (Wang and Burris, 1997; Clark, 2010; Sarti et al., 2018; Abma et al., 2022). For instance, Freire, 1970 demonstrates how photovoice allows participants with limited resources (i.e., money, power, or social status) to document and share their lived experiences, and voice what changes are necessary to improve health and wellbeing in their community as they see them. In feminist theory, which claims that power is conferred to those who have a voice, decide language, influence history, and partake in decision-making (Smith Tuhiwai, 1999; Mitchell et al., 2020), Wang and Redwood-Jones (2001) found that photovoice seeks to explore feminist theoretical perspectives by bringing seldom-heard ideas, voices, and images into the public forum. From this position, feminist theory informs photovoice by enabling participants to take photographs and connect their narratives to these images in ways that best reflects their experiences and increases their voices to drive change, influence decisions, and generate awareness on issues they perceive to be important to their health and wellbeing (Wang and Pies, 2004). With regards to community-based approaches to document research, scholars have applied photovoice as a community-based participatory research (CBPR) tool to demonstrate its effectiveness for the co-production of knowledge by encouraging participants to take photos that illustrate key issues relevant to their lives, and empowering people to articulate stories through photography or other visual media (Castleden and Garvin, 2008; Vansteenkiste et al., 2021).

However, research on visual social and ecological change revealed an increasing tendency toward the decontextualization of images, which obscured the desires and concerns as to what is important to visualize from the perspective of different actors (Spiegel et al., 2020). From this point of view, Coats (2014) argues that photography can be a weapon that stigmatizes or victimizes, as well as a tool that empowers. Scholars refer to the former as “crises of representation” (Harper, 2012), in which visuals can replicate colonialist traditions whereby photos from the colonies were brought back to the imperialist homes to spread a certain desired representation of foreign lands and peoples for exploitation (Mitchell et al., 2020). Seeking to reverse these imperial traditions, critical feminist theory informs photovoice in order to situate visual representations within anti-colonial epistemologies and counteract the power relations between researchers and participants (De Leeuw and Hawkins, 2017). For example, Bennett and Dearden (2013) applied photovoice in an innovative way to explore how indigenous communities in Thailand respond to and interact with ecosystem dynamics in order to deepen the understanding of how a community's perception of change can influence their adaptive capacity to changes. They found that while photovoice was a powerful method for examining social and environmental change, a more holistic picture could have been formed by combining photovoice with other methods to explore traditional ways of addressing unwanted changes.

Other studies used photovoice to help elucidate traditional ecological knowledge about conservation and human-wildlife conflict option (Beh et al., 2013), in addition to exploring ecosystem services with indigenous communities to elicit local knowledge about land management actions (Kong et al., 2015), environmental change (Baldwin and Chandler, 2010), and sense of place (Briggs et al., 2014). Finally, an emerging area of focus is the use photovoice in disaster studies, particularly within the field of disaster management and climate change (Russo et al., 2021). For example, two recent studies have applied photovoice to engage the voices of rural and indigenous community members recovering from natural disasters in Ontario, Canada (Russo et al., 2021), and to investigate the role of social capital in disaster settings to support community resilience in the Philippines (Cai, 2017).

Notwithstanding the growing body of literature that applies photovoice to explore social and ecological changes from the perspective of indigenous communities (Baldwin and Chandler, 2010; Berbés-Blázquez, 2012; Beh et al., 2013; Bennett and Dearden, 2013; Briggs et al., 2014; Kong et al., 2015; Masterson et al., 2018), there is scant research exploring how indigenous youth perceive the wellbeing of their social and ecological environment in the context of a global disruption. In one study that investigates indigenous youths' perspectives on water and health in First Nations communities in Canada, Bradford et al. (2017) found that while youth enjoyed the opportunity to be engaged in research, further development of the relationship between youth participants and the research team was necessary. This was due to the challenges imposed by protocols for accessing, working with, and gaining ethics approval for projects with First Nation youth, which created complications for direct collaboration between external researchers and indigenous youth participants. The research presented in this article avoided the challenges Bradford et al. (2017) encountered by implementing a culturally responsive manner of conducting photovoice interviews with indigenous youth through the development of local research partnerships. In this way, the article aims to fill the gap empirically and conceptually by applying a modified photovoice technique that can capture both the perspectives and experiences of indigenous youth, as well as their traditional knowledge and understanding of social and ecological change during the global disruption of COVID-19.

The next section contextualizes the photovoice project with a brief discussion on why photovoice and visual research tools need to be linked with traditional understandings of wellbeing to develop a culturally appropriate way of including indigenous youth in the exploration of social and ecological wellbeing during disaster times. The section thereafter discusses the modifications made to the study methods to enable remote data collection, designed to support the objective of providing a venue for indigenous youth to voice their experiences and ideas regarding concerns, issues, desires and values connected to the social and ecological wellbeing of their small island community in Rarotonga, Cook Islands.

Modified versions of photovoice have become common within the existing literature as scholars seek to meet the realities and needs of communities (Castleden and Garvin, 2008; Badowski et al., 2011; Bennett and Dearden, 2013; Mitchell, 2017). As LaVeaux and Christopher (2009) note, the flexibility of photovoice is a particularly important aspect of its applicability where cultural considerations such as indigenous ways of knowing and learning, sovereignty, and extended timelines are essential to the research process. According to Wang and Burris (1997), photovoice can be “creatively and flexibly adapted to the needs of its users” (p. 383). In other words, photovoice is an adaptable method that is modifiable to fit a particular community's needs and preferences. This study modified the photovoice technique to develop a culturally appropriate method to include the voices of indigenous youth while still honoring the traditional values found in the tivaevae model of wellbeing in the Cook Islands.

In addition to illustrating the multifaceted concept of wellbeing, the tivaevae model is also considered a significant social phenomenon in the Cook Islands that represents the cultural process of sharing and transferring traditional knowledge and practices in research (Rongokea, 2001). Teremoana Maua-Hodges, a renowned leader in Pasifika education, adopted the tivaevae metaphor to underpin education and research in culturally responsive ways (Maua-Hodges, 2000). The application of tivaevae as a theoretical model for culturally responsive education and research comprises five key values: taokotai (collaboration), tu akangateitei (respect), uriuri kite (reciprocity), tu inangaro (relationships), and akairi kite (shared vision). These values are considered to shape the ways of knowing and being in the Cook Islands. For instance, during the making of the tivaevae, the concept of akairi kite (shared vision) holds great importance among Cook Islands women constructing the tapestry. Prior to making the tivaevae, women share stories and collectively decide on a shared vision of how the tivaevae is going to turn out (Te Ava et al., 2011). According to Rongokea (2001), the value of having a shared vision is culturally responsive because it recognizes the principles of tu akangateitei (respect), tu akakoromaki (patience), and tu kauraro (humility).

The reciprocal practices between teachers and students, researchers and participants, families and communities, are also represented in the making of the tivaevae as women develop uriuri kite (reciprocity) to produce akairi kite (shared vision). Finally, the process of developing tu inangaro (relationships) and the practice of taokotai (collaboration) is represented in the making of the tivaevae. Within the cultural metaphor, relationships start with family and expand out to the community, which is a process that is grounded in papa'anga (genealogy) and occurs over a period of time (Maua-Hodges, 2000). In summary, the tivaevae is a collaborative process of developing relationships over time, whereby the weaving of the tivaevae symbolizes the cultural values of a society that are considered essential to creating and sustaining a healthy community (Merriam and Mohamad, 2000). This study modified the photovoice technique to fit the traditional ways of knowing and conducting research in the Cook Islands by developing partnerships with local research partners and non-governmental organizations, and creating a shared vision of the research project in order to respectfully engage indigenous youth in the exploration of social and ecological wellbeing during the global disruption of COVID-19.

From January 2021 to April 2021, the research team in Auckland engaged in a series of Zoom meetings and email conversations with various local environmental and education NGOs in Rarotonga to discuss the potential of engaging indigenous youth in the exploration of social and environmental change. Dr Rerekura Teaurere, the second author of this paper, was instrumental during these consultation meetings. As a native Cook Islander from the outer island of Tongareva, Dr Rerekura Teaurere introduced the research team to Korero o te‘Orau. Given their extensive experience with environmental education programs for local youth, and their passion for protecting the culture, environment and natural resources of the Cook Islands, the research team was eager to collaborate with Korero o te‘Orau for the design and implementation of the photovoice research project. In turn, the NGO was interested in collaborating with the research team in hopes of increasing the visibility of their education programs and raise awareness on the need to develop environmental education courses that integrate traditional knowledge with modern science to improve natural resource management and conservation in the Cook Islands. Thus, it was agreed that both parties could benefit from collaborating on the photovoice research project.

It is critical to recognize, however, that the partnership between the research team in Auckland and Korero o te‘Orau would not have been possible without the cultural knowledge and support offered by Dr Rerekura Teaurere. Throughout the photovoice research project, Dr Rerekura Teaurere reminded the research team to uphold the Cook Islands cultural values of relationships, respect, and reciprocity while developing and nurturing partnerships with local stakeholders and indigenous youth participants. It is because of Dr Rerekura Teaurere's familiarity of the local social-cultural context, and her willingness to share her key contacts from her local network, that this photovoice project was able to be implemented. In summary, the relationships that developed between the research team in Auckland and the local environmental NGO in Rarotonga were an invaluable contribution to this study. This partnership ensured a culturally adequate engagement of indigenous youth in the exploration of social and environmental change across geographic and cultural borders during the disruption of COVID-19.

The digital implementations of qualitative methods such as online interviews and focus group discussion have burgeoned since 2010 parallel to the advancements in information and communication technologies (Brüggen and Willems, 2009; Tuttas, 2015; Woodyatt et al., 2016; Lovrić et al., 2020; Howlett, 2022). In contrast to online interviews, however, the use of online photovoice has only recently emerged as an alternative modality (Lichty et al., 2019; Tanhan and Strack, 2020). According to scholars, there are a couple reasons that may have contributed to this. Chen (2022) argues that photovoice relies on the constant interactions between researchers and participants throughout the entire photovoice process, which could present challenges for online modifications. On a similar note, Liebenberg (2018) emphasizes the importance of building rapport between participants and facilitators for conscious building and developing trust, particularly with photovoice studies that involve marginalized, rural, or vulnerable communities who may not be able to afford and/or have access to internet technology. Despite these perceived constraints, the literature indicates that the use of online photovoice research has grown in recent years due to an increasing impetus to reach a broader audience by eliminating geographic constraints (Lichty et al., 2019; Chen, 2022).

In contrast to the traditional format of in-person photovoice research, which tends to focus on a small group of people within marginalized rural communities (Baldwin and Chandler, 2010; Berbés-Blázquez, 2012; Bennett and Dearden, 2013; Briggs et al., 2014), the use of online photovoice (OPV) has predominantly been used by researchers who seek to reach and engage with a larger group of participants across various geographic and cultural boundaries (Chen, 2022). For example, Lichty et al. (2019) were able to reach 120 youths across various states in the United States through the use of online blogs where the youths could share and reflect on their photographs while participating in online group discussions. Tanhan and Strack (2020) were the first to operationalise the OPV technique by designing the five-step process. The OPV five step process requires participants to first (1) individually identify a key topical issue, (2) submit photograph(s) with captions via an online questionnaire, (3) select one photograph, (4) identify themes from it, and (5) attend a photo exhibition at the end (Tanhan and Strack, 2020). Within the existing literature, a flurry of articles were found to use this five step process, which enabled researchers to easily reach over 100 participants (Tümkaya et al., 2021; Chen, 2022; Tanhan et al., 2023). The online photovoice technique used in this study, however, differs from the aforementioned OPV studies that aim to scale up participation to a larger, geographically dispersed audience. Rather than using blogs or websites to facilitate photo sharing and discussions with a large group of participants (Lichty et al., 2019; Call-Cummings and Hauber-Özer, 2021), the research presented in this article maintained the traditional format of in-person photovoice research in the sense that it focused on a small group of participants. The reason for applying online videoconferencing communication technologies was to facilitate real-time interaction between indigenous youth and researches despite the geographic limitations imposed by the travel restrictions of COVID-19. As the results indicate, the use of videoconferencing and advanced communication technologies enabled the research team to engage in a meaningful way with indigenous youth to develop a deeper understanding on how they perceive the wellbeing of their social and ecological environment.

Scholars have recognized the significant potential of online communication technologies, also known as Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP), to support qualitative data collection (Deakin and Wakefield, 2014; Braun et al., 2017; Archibald et al., 2019). Within the existing literature, VoIP technologies (e.g., Skype, Facetime, and Zoom), are often considered jointly with other asynchronous internet communication technologies, such as instant messaging, online focus groups, and email (Archibald et al., 2019). However, VoIP technologies differ significantly from asynchronous methods. While asynchronous online interviewing methods enable communication that occurs at different times, VoIP allows for real-time interaction involving sound, video, and written text (Sullivan, 2012). Thus, VoIP has the ability to transmit and respond to verbal and nonverbal cues, thereby replicating and possibly improving upon traditional methods such as face-to-face interviews (Braun et al., 2017).

Compared to in-person interviews or focus groups, communication technologies may be more attractive for researchers and research participants due to convenience, efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and flexibility (Carter et al., 2012; Horrell et al., 2015). In studies that compared face-to-face interviews vs. online communication technologies, researchers found that online participants were more open and expressive (Cabaroglu et al., 2010), and that the quality of interviews did not differ from face-to-face interviews (Mabragana et al., 2013). Video conferencing has also been used to gain access to larger and more diverse populations (Deakin and Wakefield, 2014), conduct research with participants over a large geographical spread (Archibald et al., 2019), interview more participants in a shorter amount of time by eliminating travel (Winiarska, 2017), and reduce unpredictable circumstances, such as poor weather conditions that would deter participants from meeting face-to-face (Sedgwick and Spiers, 2009).

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, advances in online communication technologies and video conferencing offered opportunities for both quantitative (Casagrande et al., 2020; Ko et al., 2020) and qualitative researchers (Bender et al., 2021; Fawaz and Samaha, 2021) to adapt established methodologies in order to continue their research studies. For example, in a qualitative research study exploring youth alcohol consumption and family communication, Dodds and Hess (2020) had to shift their face-to-face interviews to online interviews. Their findings revealed that online platforms in qualitative research provided a safer and more comfortable environment by enabling youth participants to feel more relaxed and less intimated than in face-to-face contexts (Dodds and Hess, 2020). While there is a large body of knowledge that demonstrates the use of VoIP for various forms of qualitative research studies, literature on the use VoIP for online photovoice is limited (Chen, 2022). With the exception of a few studies that used online photovoice through the use of VoIP to explore the emotional impacts of COVID-19 on health care practitioners (Dare et al., 2021; Rania et al., 2021; Boamah et al., 2022; Osman and Singaram, 2022) no studies were found to use this modified technique to engage indigenous youth for the exploration of social and ecological wellbeing during a global disruption. This paper contributes to the emerging online photovoice literature by exploring the potential of VoIP technologies in facilitating culturally responsive research and meaningful engagement with indigenous youth participants for the exploration of social and ecological wellbeing during a global disruption.

In deciding which VoIP platform to use, a researcher needs to consider which program best fits their research needs. While there are many VoIP platforms for researchers to choose from, including Skype, Teams, Zoom, Zoho Meeting, Google Meet, GoToMeeting, Eyeson, and Microsoft Team (Gray et al., 2020), the majority of the existing research focuses on Skype (Deakin and Wakefield, 2014; Nehls et al., 2015; Braun et al., 2017). In a recent study on the use of VoIP programs for qualitative research, Gray et al. (2020) found no peer-reviewed published studies examining other VoIP platforms, such as Zoom. Given the limited existing literature, the lead investigator of this study selected a VoIP platform based on budget, user ease, administrative options, and personal level of comfort with the platform. After comparing various VoIP platforms, Zoom was chosen as the designated research tool to conduct photovoice interviews with indigenous youth participants in Rarotonga, Cook Islands.

Zoom is a collaborative, cloud-based videoconferencing service offering features including online meetings, group messaging services, and secure recording sessions (Zoom Video Communications Inc., 2016). Similar to other VoIPs, Zoom offers the opportunity for individuals in geographically dispersed areas to communicate with each other in real time via computer, tablets, or mobile devices (Zoom Video Communications Inc., 2016). Zoom does not require participants to have an account or download the software (Skype Technologies, 2018). Instead, participants can easily join the online meeting by simply clicking on a live link generated by Zoom. In this way, participants who are not familiar with advanced technologies that require complicated downloading procedures are less likely to be deterred by Zoom. Furthermore, downloading software in contexts that do not offer free access to internet may require participants to use their mobile data, which can be quite costly and may deter potential participants to partake in this study. Therefore, the ability to join a Zoom meeting by simply clicking on a live link offers a cost effective and convenient method for conducting online photovoice interviews.

Another advantage offered by Zoom is the screen-sharing ability for both the researchers and participants, which can be used to display information including the participant information sheet, the consent form, and the photographs taken by participants. Furthermore, Zoom includes password protection for confidentiality and recording capacity to either the host's computer or Zoom's cloud storage (Gray et al., 2020). This feature automatically saves the interview into two files, audio only and a combined audio video file, which maintains the in-person connection between the researcher and the participant while respecting the participant's choice about being recorded with audio and video or audio only.

The research team offered to provide funding for the purchase of disposable cameras. However, all youth participants had access to a camera, either via their own personal mobile phone camera, or a camera provided by the local environmental NGO. Youth participants used their own personal computers and/or mobile phones to participate in an online semi-structured interview. With regards to the videoconferencing platform Zoom, the software was free of charge for participants. The lead investigator purchased a monthly license fee of US $ 14.99, which enabled up to 30 h per meeting (compared to the 40 min limit offered in the free version). Participants did not need to purchase or download the software to join in a meeting.

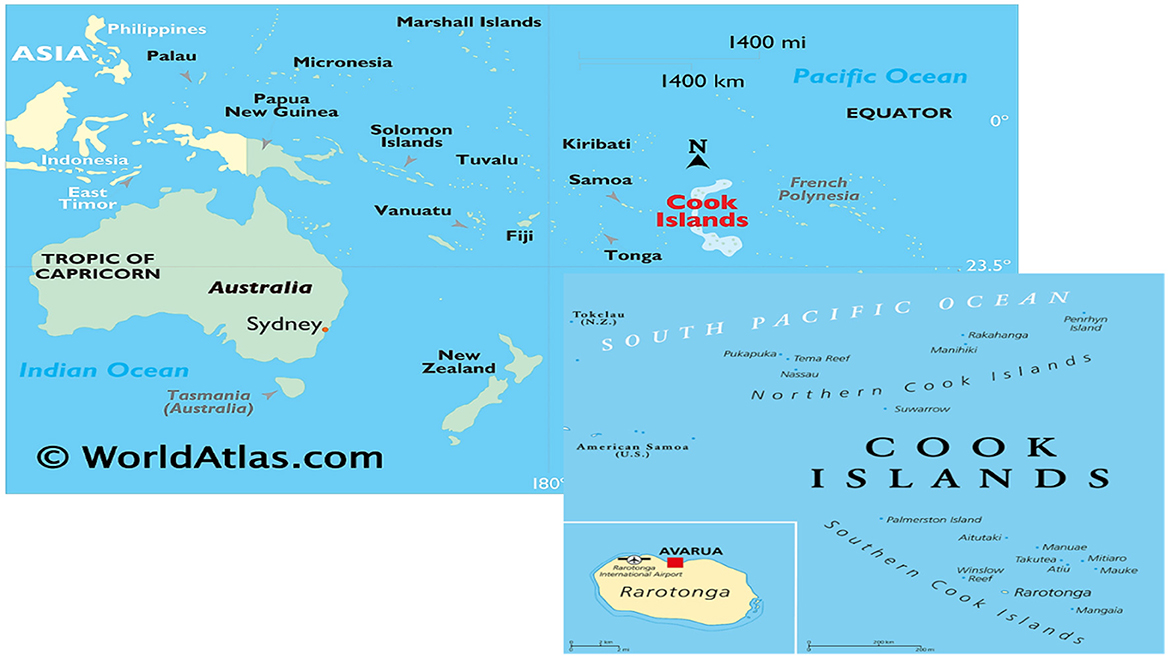

The Cook Islands are self-governing small islands nation in free association with New Zealand, located in the South Pacific between Tahiti and American Samoa (Figure 3). The 15 atolls and islands that make up the Cook Islands are spread over ~2 million km2 (Cooke et al., 2021). Nearly 75% of the resident population of about 14,800 lives on the main island of Rarotonga (Cook Islands Statistics Office, 2018). The Cook Islands' economy has been described as “a small, open economy, dependent on imports, and whose economic growth is heavily reliant on the export sector dominated by tourism services accounting for about 70% of economic output” (Cooke et al., 2021, p. 260).

Figure 3. Map of the Cook Islands (World Atlas, 2021).

Prior to the global disruption of COVID-19, the Cook Islands reached a record high of nearly 167,000 international tourist arrivals in 2018/2019 (Cook Islands Government, 2020). Despite experiencing steady economic growth from the booming tourism sector, estimates of the Cook Islands output gap in 2019 indicated that the economy was operating above its capacity, with constraints in the form of labor, skills, and housing shortages (Cook Islands Government, 2019). Furthermore, recent studies demonstrate the negative environmental impacts associated with increasing tourism developments, including coastal erosion, increased pollution, and progressively degraded lagoons (Durbin, 2018; Prinz et al., 2020). In addition to the increasing anthropogenic pressures, the Cook Islands face the adverse effects of climate change and natural disasters, including rising sea levels, more intense tropical cyclones, heavy precipitation and flooding. The oceans and marine life, particularly coral reef ecosystems, are also severely threatened by ocean acidification, which is another result of the progressing climate change impacts (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2018).

Much of the literature that explores the double exposure presented by the climate change-tourism nexus in the Cook Islands and other PICs have a tendency to focus on the economic impacts of a storm, rather than the social and/or ecological impacts (Adger et al., 2011; Hallegatte, 2016; Fankhauser, 2017). Furthermore, limited (if any) studies focus on the perspectives and lived experiences of indigenous youth in the face of environmental and/or socio-economic disruptions. For these reasons, the heavily tourism-dependent island of Rarotonga, Cook Islands was selected as the setting to engage indigenous youth in the exploration of social and ecological wellbeing during the global disruption of COVID-19.

Prior to recruiting youth participants, an ethics application was submitted and approved by the Auckland University of Technology Human Ethics Committee (AUTEC) on 19 April 2021. In this application, it was decided that a local staff member from Korero o te‘Orau, who did not hold any conflict of interest, would be responsible for the recruitment of high school students. In order to raise awareness on the environmental education programs offered by Korero o te‘Orau, it was imperative that the prospective youth participants were either currently enrolled or had previously participated in the NGO's programs. Since the 'tui'anga ki te Tango programme had only been in operation since 2017, there were limited available students that would be eligible to participate. Nevertheless, we were able to receive the voluntary consent of four young adolescent females, in addition to the consent of their parents. All details for the recruitment procedure of students can be found in the AUTEC application upon request.

Once the successful voluntary recruitment of indigenous youth participants was completed, the lead investigator of the research project emailed each student and their respective parent/guardian an information sheet which described the photovoice interview process. The email also included a consent and release form, parent/guardian consent form, and an ascent form. The students had 2 weeks to decide if they wanted to participate in the photovoice project. Prior to deciding, the local staff member encouraged all students and their parents/guardians to contact the lead investigator and Dr Rerekura Teaurere with any questions they may have pertaining to the research. After all participants and their respective guardians had an opportunity to ask questions, all four high school students emailed the lead investigator stating that they were willing to voluntarily participate in the photovoice research project.

Given the cultural context of the Cook Islands, the importance of building a relationship based on trust and friendship with participants was a critical component prior to commencing data collection. Thus, a Facebook group chat was created to build a relationship with the youth participants. All four youth participants, their respective guardians, and the local staff member of the NGO were invited in the Facebook messenger chat. Given the students' familiarity and comfort with the use of social media, the Facebook group chat proved to be an effective means of building rapport with the youth participants and maintaining communication throughout the entire photovoice project. Once again, the role of Dr Rerekura Teaurere was instrumental in bridging the cultural gap between the lead investigator and the youth participants. For example, even though the lead investigator was the designated key contact person in the Facebook group chat, all youth participants and NGO staff members directed their questions, comments, and concerns to Dr Rerekura Teaurere. It was only after a few weeks of open and honest communication that youth participants felt comfortable directly approaching the lead investigator. This again proves the importance of having a team member that is genuinely familiar and knowledgeable with the local context when conducting cross-cultural qualitative research.

The four indigenous youth participants were asked to take two to three photos of something they perceived as important and valuable for the wellbeing of their natural environment, and two to three photos of something they considered was important for the wellbeing of their community. Participants were initially given 2 weeks to complete the photographic component of the assignment. However, due to unforeseen circumstances and busy school schedules, participants completed the assignment in ~2 months. Such a delay would have presented various challenges if the research team was in-situ and were constrained by limited time and funding. However, this was not perceived as a challenge due to the remote nature of the research and the flexibility offered by the modified online photovoice technique.

After each participant had successfully taken their photos, they sent their photographs either via the Facebook group or by email. Once all photos had been documented and safely stored, the primary researcher and Dr Rerekura Teaurere invited each youth participant to participate in an online semi-structured interview via Zoom. During the online Zoom interviews, youth participants were asked to explain why they took each photograph, and what each photograph meant to them. They were reminded that there are no right or wrong answers. Dr Rerekura Teaurere was present during all four semi-structured Zoom interviews with youth participants to provide familiarity, and to help the primary researcher understand critical socio-cultural values and meanings as the youth shared their stories for each photograph they took. The online semi-structured interviews lasted between 45 min to 1 h each.

The aim of semi-structured interviews is to explore the subjective responses of participants regarding a particular phenomenon they have experienced, and the meanings they attribute to these experiences (Bartholomew et al., 2000). They offer a highly flexible approach to the interview process by using open-ended questions that define the area to be explored, from which the researcher and participants may diverge from to pursue an idea in more detail (Rakić and Chambers, 2012). Researchers are required to have a list of questions and topics pre-prepared when using semi-structured interviews, yet these questions can be asked in different ways with different participants (Schmidt, 2004). The flexibility of semi-structured interviews increases the responsiveness of the interview by allowing the researcher to ask probing questions and permitting participants to change the order of questions depending on their interest and willingness to elaborate on certain topics (Longhurst, 2003).

According to Galletta (2013), one of the main advantages of semi-structured interviews is that it has been found to be successful in enabling reciprocity between the researcher and participant by developing open-ended questions. In turn, open-ended questions enable the researcher to ask follow-up questions based on the participant's responses, and allows space for participants to elaborate on a particular subject of interest (Kallio et al., 2016). In this way, youth participants were free to respond to the open-ended questions as they wish, and the researchers probed these responses by asking follow-up questions to obtain additional information and gain a better understanding of the participants' viewpoint (Adams et al., 2010). Furthermore, the use of open-ended questions provoked a more thoughtful and reflexive approach to the photovoice method (Plunkett et al., 2013). From this position, this study combined the photovoice technique with open-ended questions to guide semi-structured interviews with indigenous youth participants.

The aim of this article is to illustrate the potential of online photovoice through the use of Zoom as a qualitative research tool to enable remote data collection while maintaining meaningful engagement with youth participants in the exploration of social and ecological wellbeing during the disruption of COVID-19. This section offers a summary of the key learnings. Selected findings are used to illustrate these key learnings.

The lead investigator analyzed the findings from the interview transcripts pertaining to each photograph. Data included photographs taken by youth participants and transcripts from the online semi-structured interviews conducted with each participant. The primary researcher transcribed all the interviews. While the process of transcribing deepened the lead investigator's understanding of the youth participants' lived experiences and perspectives of social and ecological change (Lester et al., 2020), it also revealed how the primary researcher's own initial reaction may have prematurely shut down an avenue of exploration. Thus, it was critical for Dr Rerekura Teaurere to read over the transcripts and discuss the cultural significance of the primary data with the lead investigator prior to engaging in further analysis. After the transcripts were revised by Dr Rerekura Teaurere and the lead investigator, they collectively explored the social and cultural value of the data. Then, the lead investigator coded the data independently.

A constant comparison method was applied to analyse the qualitative data in an iterative process (Charmaz, 2006). The lead investigator coded the data using the analysis process of constructive grounded theory, which consists of three coding stages: initial coding, focused coding and theoretical coding (Charmaz, 2006). During the initial coding stage, codes were created by inductively generating as many ideas as possible from the data. The codes assigned in the initial phase are often descriptive and reflect a relatively low level of inference (Lester et al., 2020). In the second stage of coding, referred to as focused coding, the lead investigator returned to passages in the data where codes were assigned during the initial coding phase, and began connecting statements, experiences, and reflections offered by youth participants to create codes at a higher level of inference (Anfara Jr et al., 2002).

As focused coding progressed, and codes (inter) related and contrasted with one another, categories began to emerge, which were grouped into themes. The development of categories represents an important intermediate step in the process of thematic analysis. The process of creating themes that are inclusive of all the underlying categories is known as theoretical coding. Theoretical coding involves recognizing similarities, differences, and relationships across categories, as well as being descriptive of their content and the relationships between them (Birks and Mills, 2015). Since themes are generally aligned with the conceptual or analytic goals of the study, the lead investigator grouped themes by questioning how the categories (inter) relate with each other in response to the study's primary question. The themes that emerged from the data were discussed with all members of the research team. Dr Rerekura Teaurere had a leading role in these cultural discussions, given her socio-cultural knowledge of the context and her invaluable contribution throughout the project.

The four final themes that evolved from the data analysis were traditional knowledge, the land, the sea, and the climate. Indigenous youth participants took photographs of the land, the sea, and impacts of climate change to describe how these elements influence the social and ecological wellbeing of their island home. For example, one participant took a picture of the vaka (a traditional seagoing vessel) as she reflected on the importance of learning about traditional knowledge to understand her ancestry, which allowed her to feel more connected to the ocean (Figure 4).

“Before we started learning about the vaka, I didn't really feel a connection towards it. It was kind of just there on the harbour. But now that we did the overnight sailing trip, I felt really connected to the ocean and to my ancestors and I realised that this is how they traveled, and why this is really important for us. We are voyagers, this is our history, it's our culture. So now when I see the vaka, I see my heritage right there! And its still going from centuries! We are still carrying it on!”

Figure 4. Photograph of the traditional seagoing canoe taken by an indigenous youth participant in Rarotonga, Cook Islands.

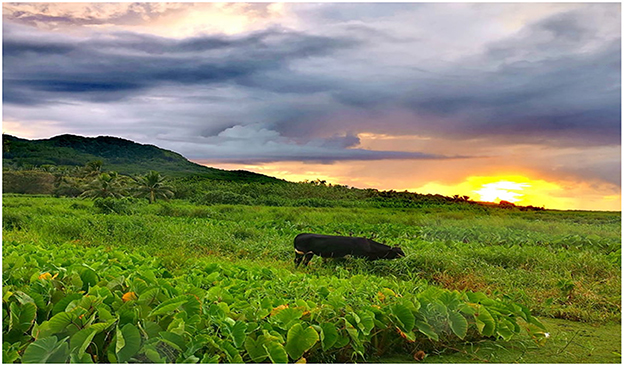

Photographs of culturally significant locations, native root crops, and traditional agricultural practices were also taken to illustrate the importance of traditional knowledge for the social and ecological wellbeing of the youths' small island community (Figure 5).

“Taro is very important to our culture because we survived on it for years, for generations. Taro plantations are a large part of our culture and agriculture. And its passed down from generations… This is really important for us to know, so when COVID-19 happens, or when similar issues like that happen, we have something we can come back to—a source of food that we can come back to. If we take care of the land it will take care of us.”

Figure 5. Photograph of a taro plantation in Rarotonga, Cook Islands taken by an indigenous youth participant.

Participants further discussed the changes they observed in their social and ecological environment during the global disruption of COVID-19 in terms of trade-offs. For example, one youth participant created a collage of her favorite places to reflect on the ways that tourism has impacted the social and ecological wellbeing of her community (Figure 6). In addition to observing the social and ecological changes during the COVID-19 disruption, all youth participants also discussed the economic hardships resulting from the sudden crash of the tourism sector, including the rising unemployment rates and the significant outward migration of Cook Islanders leaving to New Zealand in search of economic opportunities. In conclusion, the youth recognized that while the ecological and social environment benefitted in various ways during the global disruption of COVID-19, the financial crisis ensued by the crash of the tourism industry also contributed negative socio-economic impacts for the wellbeing of their community.

“I do see a positive change from COVID-19, it allowed our people to realise that we need to avoid becoming a mono-economy and relying only on tourism. With COVID-19, I realised that we are slowly shifting back into agricultural production and planting—I really do see a lot of families going back into planting taro as their food security, and they realised that with covid and everything going on around it, we might not get the chance to have a lot of supply of food and so we do realise that and we need to shift back into our agricultural practices.”

Figure 6. A collage of various different landscapes in Rarotonga, Cook Islands photographed by an indigenous youth participant.

As evidenced from the brief examples above, the combination of semi-structured interviews, open-ended questions, photovoice, and Zoom as qualitative research tools to engage indigenous youth in the exploration of social and ecological change proved to be empowering and inclusive methods that contributed many benefits to this study. To further support the former, youth participants were asked to reflect on their experience participating in this photovoice project. In their response, one participant stated the following:

“Personally, it was a really great experience using photos to help discuss the social and environmental issues in our home island. It helped me to look further through images to try find a deeper meaning or issues within it. I didn't realize how much you could get out of simple images. This opportunity helped me to have more awareness of social and environmental issues going on around me.”

Since the youth participants had only ever participated in one photovoice project, they were not able to compare their online photovoice experience with a face-to-face photovoice project. However, Dr Rerekura Teaurere, who has extensive research experience in Rarotonga provided her feedback on the use of VoIP for online photovoice:

“I noticed that participants were more than willing to go above and beyond contributing to the study with frequent communication compared to face-to-face interviews. Online interviewing means time in country is no longer a barrier to implementing respect, reciprocity, and building and maintaining relationships. Everyone involved in the online research gained something from it, and this strengthened research partnerships and made future research in the small communities of the Cook Islands more accessible.”

Evidently, the modified photovoice method applied in this study to engage indigenous youth in the exploration of social and ecological wellbeing during a global disruption contributed various benefits to both the researchers and participants in this study. As a gesture of reciprocity and appreciation for having participated in this project, a photovoice book was created and gifted to all youth participants, their respective guardians, and the local NGO. The research funds that were initially meant to cover travel costs were allocated to provide a salary for a local artist in Rarotonga, Cook Islands. The local artist designed a book with the photographs and subjective narratives derived from the youths' photovoice interviews. The research funds also covered the costs of professionally printing and binding 15 copies of the photovoice book in Auckland, New Zealand. The local NGO Korero o te‘Orau was able to use the photovoice book to disseminate the findings from the project to current and prospective donor partners to demonstrate the success of their programs, which may lead to more funding in the near future.

The application of Zoom as a videoconference online communication platform to facilitate photovoice interviews provided a way to engage and include the perspectives and lived experiences of indigenous youth for the exploration of social and ecological wellbeing during a global disruption. The inclusion of youths' perspectives on the social-ecological wellbeing of a small island community in the Pacific contributed to a unique holistic understanding of indigenous wellbeing that is rarely documented within the existing literature due to the cultural barriers that enforce social hierarchies in traditional Polynesian societies (Larmour, 2009; Taumoefolau, 2019; Poppelwell and Overton, 2022). This in turn enhanced the quality and credibility of the project's research findings.

The findings suggest that youth participants benefited from using the photovoice technique as it shares similar oral and visually oriented practices found in the application of the tivaevae model of wellbeing for culturally responsive research in the Cook Islands. For instance, the use of photography and subsequent semi-structured interviews enabled youth participants to document and discuss social and ecological changes during the disruption of COVID-19. As such, the application of a culturally responsive research technique enabled indigenous youth participants to grasp complex inter-sectoral impacts ensued by the global disruption of COVID-19. Furthermore, by respecting the Cook Islands cultural values of reciprocity, shared vision, and relationships, the modified photovoice technique enabled the research team to collectively create a shared vision of the research project by developing partnerships with local researchers, NGOs, and indigenous youth prior to conducting research. In terms of reciprocity, all local stakeholders involved in the project considered that the photovoice book was a generous and much appreciated gesture.

In personal communication with the lead investigator and Dr Rerekura Teaurere, youth participants described other benefits, including an increased awareness about the impacts of tourism on the wellbeing of their community and natural environment. Youth participants also claimed that by engaging in this photovoice project, they gained a deeper understanding on pre-existing issues, such as the challenges of depending on imported goods, or over-relying on the tourism sector to support the economy. They were thrilled to have the opportunity of participating in an international research project, where they could develop their analytical thinking skills through the use of photography and share their traditional knowledge and passion for environmental conservation. One participant even asked the principal investigator for a letter of recommendation as part of her application to a university in New Zealand to study environmental science. The findings further indicated the success of the environmental education programs offered by Korero o te‘Orau, particularly in their ability to teach indigenous youth how to integrate traditional knowledge with modern environmental science in practical ways that relate to contemporary issues.