95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

METHODS article

Front. Sustain. , 05 February 2025

Sec. Sustainable Consumption

Volume 6 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2025.1507708

This article is part of the Research Topic Global Excellence in Sustainability: Europe View all 7 articles

This paper presents a novel methodological approach that integrates strategic foresight with sustainability transitions frameworks to explore how different forms of agency shape transition pathways. The research methodology employed include the development of foresight scenarios addressing sustainability, the X-curve framework for mapping possible transition pathways for a sustainable EU 2050, and agency analysis to identify strategic areas of interventions and understanding systemic policy mixes over time. This work was performed in the context of the preparation of the European Commission’s Annual Strategic Foresight Report 2023. Additionally, through empirical application across three distinct contexts, this paper demonstrates how strategic foresight can generate actionable knowledge for sustainability transitions while maintaining methodological rigor. The study advances the theoretical understanding of agency in sustainability transitions by showing how different actors can be strategically engaged through interventions aimed at shaping, navigating, and orchestrating transition pathways over time. Our findings reveal that successful transitions require balancing the agency of established institutional actors with emerging stakeholders who may lack formal authority but bring crucial perspectives and capabilities. The study emphasizes the importance of agency of multiple actors in sustainability transitions, highlighting their capacity to act and collaborate in shaping a sustainable future. The conclusions and recommendations stress the need for strong government leadership, multilevel coordination, the roll out of systemic policy mixes and a new social contract underpinned by democratic governance. The flexibility of the methodological approach allows adaptation to different institutional contexts through co-creation while maintaining coherence in how agency dealt with. This research contributes to both theoretical development and practical policy implementation by providing a structured yet adaptable strategic foresight approach to investigate how different forms of agency can effectively be combined to drive sustainability transitions.

This paper presents a novel methodological approach, based on foresight, to foster the emergence of a deeper understanding of sustainability transitions for policymaking at EU level. It illustrates how foresight, by implementing structured and inclusive collective intelligence processes, can contribute to producing actionable knowledge for policymaking. This can take various forms, such as the construction of collective narratives of possible alternative transition pathways, each addressing different triggers and leverage points for transformative change. The study focuses on the design and implementation of a foresight process for the preparation of the EU Strategic Foresight Report 2023. Its scope was ‘Sustainability at the heart of the EU’s open strategic autonomy: what strategic decisions need to be made to ensure a socially and economically sustainable Europe with a stronger role in the world in the coming decades?’

The starting point was the creation of a set of four foresight scenarios describing various versions of how the EU could be sustainable by 2050. Climate-neutrality was set as the central normative condition for all scenarios. A sustainability assessment framework was then applied to these scenarios to identify the structural economic and social changes that would have to take place to create future sustainable societies. The inclusive, participatory foresight process combined several methods and engaged in a simultaneous analysis, assessment and interpretation of the evolving results.

To create actionable knowledge that would be useful for policymakers to discuss sustainability transitions, the foresight process generated various interrelated outputs that can be further developed and applied by others in a wide range of settings, including to accommodate a regional or sectoral focus.

The novel approach designed for this project demonstrated the usefulness of incorporating concepts from sustainability transitions into a foresight process that took a systemic and long-term perspective. This paper draws on the knowledge collected in the JRC report (Matti et al., 2023) and additional insights gathered by the team when applying the approach to various policy requests.

The research design follows a systematic analytical progression to explore how strategic foresight can generate actionable knowledge for sustainability transitions through three complementary analytical levels: (1) the methodological aspects of the strategic foresight process in sustainability transitions by incorporating a sustainability assessment framework for scenario development and the X-curve framework for transition pathway mapping, (2) analysis of agency in sustainability transitions to understand systemic policy mixes over time, and (3) the comparative analysis of the use of the methodological framework in three different contexts.

The methodology explicitly examines agency – defined as the ability of actors to shape, navigate, and orchestrate change processes – both as an analytical lens within the foresight process and as an empirical object of study in different strategic intervention areas. This dual approach makes it possible to study how different actors’ capacities to act evolve through transition processes, while maintaining methodological rigour through structured foresight tools. In this context, this study makes significant contributions to the literature on strategic foresight and sustainability transitions. First, it builds a bridge between these fields by developing an integrated foresight framework that combines foresight’s ability to explore alternative futures with transition theory’s understanding of systemic change dynamics. Second, it advances the discussion on agency in sustainability transitions by demonstrating how different actors can be strategically engaged through different type of interventions across transition pathways and policy mixes overtime.

The research also demonstrates the successful application of the framework across diverse contexts - from global environmental policy (UNEP) to EU sectoral policy (Single Market) to complex systemic challenges (food systems). This versatility enables identification and assessment of key contextual factors and critical intervention areas through collective intelligence processes. The framework’s adaptability while maintaining methodological rigour makes it a valuable tool for developing actionable knowledge for sustainability transitions across governance levels. Over the next sections, the paper first presents a collection of definitions from the sustainability transitions framework that serve as lenses for the foresight process. It then describes the overall process and the combinations of methods that facilitated the interplay between foresight and the sustainability transitions framework. This is followed by a presentation of the lessons learned and the description of three additional examples where the framework was applied before drawing conclusions. Two appendices provide a detailed description of the overall protocol including the tools that were used.

Sustainability is defined in this study as the capacity to meet the needs of the present while ensuring that future generations can meet their own needs. It comprises three dimensions: Economic, Environmental and Social. To achieve sustainable development, policies in these three areas must work together and support each other (European Commission, 2023).

Sustainability transitions are defined as an umbrella term for a range of changes that involve a radical shift toward a sustainable society in response to the existential challenges facing contemporary societies (Grin et al., 2011). They are transformation processes in which different actors jointly decide on the goals of a transition and play a role in bringing about gradual structural changes. They do this by identifying the totality of changes needed through long-term thinking, reflection and management of multiple policies that need to work together as part of a systemic policy mix, and the role and linkages between actors (society, government, business) at different levels through multi-level governance models (Bulkeley, 2005; Rotmans et al., 2001).

Systemic policy mixes are combinations of measures designed to trigger systemic change. They mobilize actors and set in motion processes of change that unfold through a complex web of interactions between interventions, actors and processes and over long periods. These interactions can be defined as horizontal between different types of instruments, policies or governments - and vertical - between different levels of objectives, policies and levels of government and across sectors (Howlett and del Rio, 2015).

A policy mix that is highly supportive of sustainability is a systemic policy mix that supports change, responds to a clear vision and addresses multiple dimensions of sustainability simultaneously. A policy mix employs a range of reinforcing policy instruments that increase effectiveness in achieving overarching goals. Systemic policy mixes have a top-down orientation due to a broader policy strategy such as the European Green Deal and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They also have bottom-up implementation challenges related to actors agency to steer change by experimenting and developing a systemic perspective on policy making to situate these priorities in a local context and build local commitment and shared ownership of the strategies (Joint Research Centre, 2021).

To support this systemic perspective, one must recognize that agency (capacity to act) varies from actor to actor and depends on context. A key to managing the transition to sustainability is understanding the capacity of actors to address these strategic areas together in complex and uncertain circumstances (Contesse et al., 2021). This understanding of actors’ capacity to act can help develop comprehensive strategies and actions for the coming decades (Jørgensen, 2012). Societies can make sustainability transitions happen by harnessing the specificity of its capacity to act in different processes of change (Pesch, 2015). The development of actors’ capacity to shape, navigate and orchestrate the change process over time will determine the scope and scale of possible interventions.

In this sense, and with a view to economic geography and innovation research, Grillitsch and Sotarauta (2020) have emphasized the diversity of contexts in which actors can steer transformative change by creating “opportunity spaces” by taking into account the time perspective, place-based systemic conditions and the capacity of different actors to act. These spaces are dynamic, shaped by systemic and contextual factors that enable or constrain pathways for change. Timing sets the boundaries of what is possible at any given moment, influenced by global knowledge, institutional readiness, and resource availability.

The ‘capacity to act’ could be shaped by past, present and future perspectives (Steen, 2016) mobilized through foresight processes to build capacity, shared vision and learning. It also aligns with political cycles, guiding the design and implementation of strategies like Smart Specialization or climate adaptation. Strategic timing enables actors to leverage critical junctures in governance and policy processes to maximize impact. Place-based conditions highlight the importance of context. Local resources, stakeholder engagement, and learning opportunities define what is feasible within a specific geographic and economic space. Finally, actors’ capacity to act determines the range of possibilities within an opportunity space. Effective agency requires mobilizing resources, fostering collaboration, and navigating governance structures to influence decision-making (Grillitsch et al., 2024).

Together, these elements create opportunity spaces where systemic, temporal, and spatial dimensions converge, enabling actors to steer transformative change in sustainability transitions. Co-creation processes integrating forward-looking perspective can facilitate dialog and make these spaces compatible with the design of interventions addressing strategic issues through multi-level governance processes. The participatory nature of strategic foresight enables rethinking governance models in terms of establishing flexible roles and mechanisms of cooperation across European, national, regional, and local levels where regions and cities emerge as pivotal actors, building communities, fostering cross-actor cooperation, and enhancing the EU’s capacity to act (Matti and Bontoux, 2024).

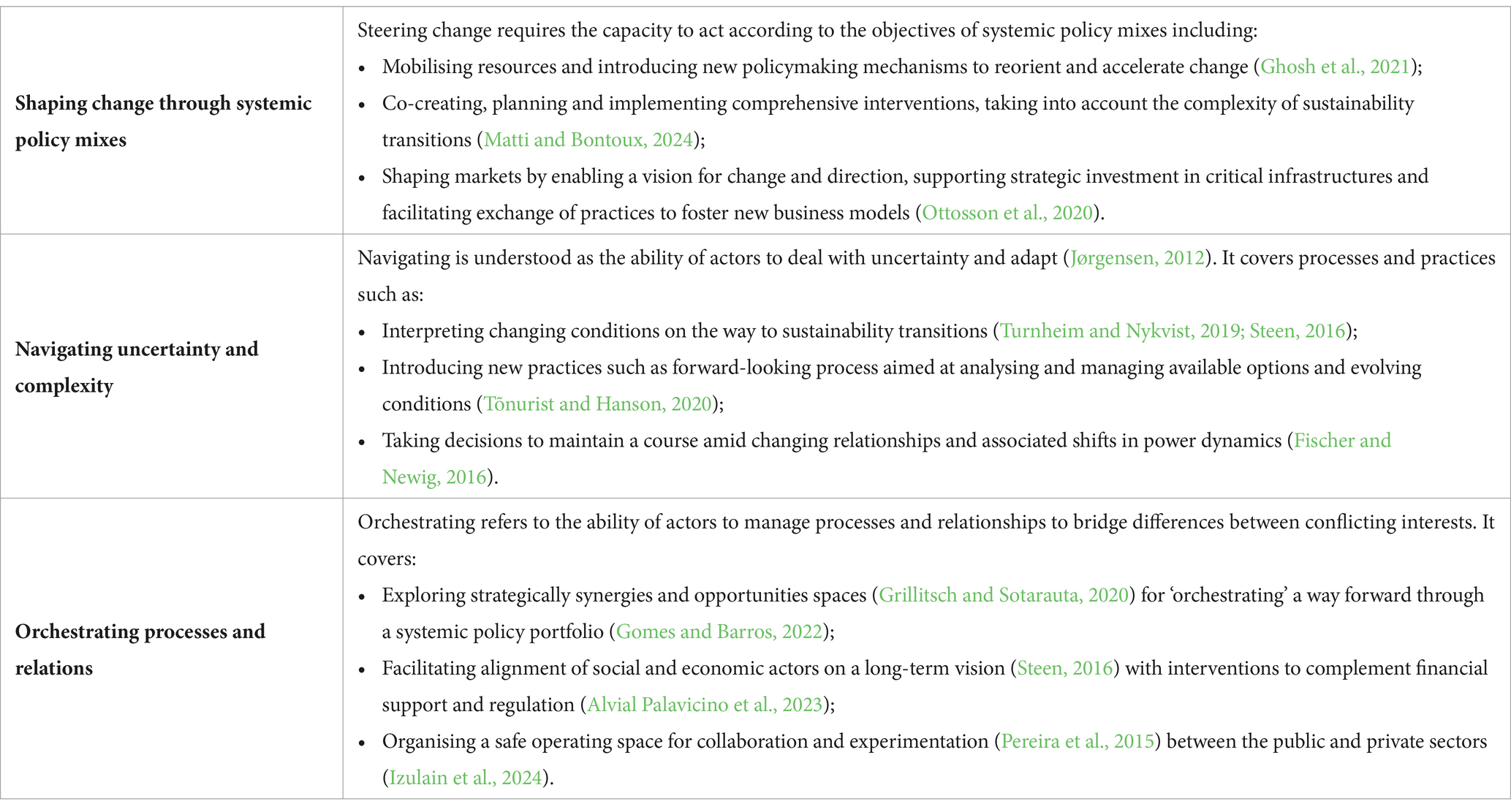

Furthermore, the development of anticipatory capacities enables the orchestration of systemic relationships in research and development, industrial transformations and cross-sector linkages, while fostering new public-private configurations to enable the shaping of conditions through the efficient use of public resources, the alignment of place-based innovation strategies with industrial and regional ecosystems, and thus the design of interventions to accelerate the reconfiguration of sectors within value chains (Izulain et al., 2024). In this way, the development of anticipatory capacity through co-creation process by integrating sustainability transitions and system change elements foster innovation and disruptive change, supports cross-sectoral policy reformulation (Tõnurist and Hanson, 2020; Matti and Bontoux, 2024) and strengthens the capacity of actors to reshape economic structures. Table 1 below summarises the different types of interventions for shaping, navigating and orchestrating change processes in sustainability transitions, by putting emphasis on the evolving development of actors’ capacity to act.

Table 1. Three types of interventions to shape, navigate and orchestrate change processes in sustainability transitions.

Table 1 Three types of interventions to shape, navigate and orchestrate change in sustainability transitions. The ‘shaping, navigating and orchestrating’ interventions not only reinforce each other but also enable building new agency between the various actors. Simultaneity, reinforcement and feedback of the systemic intervention portfolio are key in understanding how agency might evolve over time in terms of its nature and distribution between actors and across governance levels. These three types of interventions have been addressed separately in several publications dealing with policy mixes for sustainability transitions from the perspective of innovation policy (Kern et al., 2019), transformative change (Ghosh et al., 2021) and system dynamics (Grubb et al., 2017; Alkemade and de Coninck, 2021). In this context, Weber and Rohracher (2012) have addressed the challenge of developing a policy mix for transformative change, highlighting the failure of transformational systems, including failure in addressing directionality, demand articulation, policy coordination and reflexivity. In this sense, the present study aims to contribute to the discussion on disentangling policy mixes in sustainability transitions by showing how to coordinate interventions aimed at shaping, navigating and orchestrating system transformation. To that end, the study, provides a space and time for reflection and deliberation on the evolving agency of actors through a novel use of strategic foresight for the co-creation of systemic policy mixes that consider the agency of diverse actors in sustainability transitions.

The process underpinning this study was designed to be inclusive and participatory to build meaningful collective intelligence, in line with good foresight practice. Concepts from academic research on sustainability transitions were applied in the design of the foresight process and the analysis of the results to develop a good understanding of the many simultaneous transformation processes required to achieve sustainability. This combination of foresight and sustainability transitions concepts resulted in a robust collective intelligence that helped the analysis and interpretation of the results to be relevant for European policy. To this end, the team explored the relationships between the findings using additional evidence from multiple sources.

For optimal results, the original foresight study combined two parallel and interlinked processes:

1. An open participatory process including two in-person workshops and exchanges with experts. While the in-person workshops provided a broader perspective from a variety of participants from policy, academia and society, the exchange with experts provided specific insights on the different dimensions on sustainability addressed in the foresight process.

2. In-house analysis, assessment and interpretation activities involving secondary research and expert reviews.

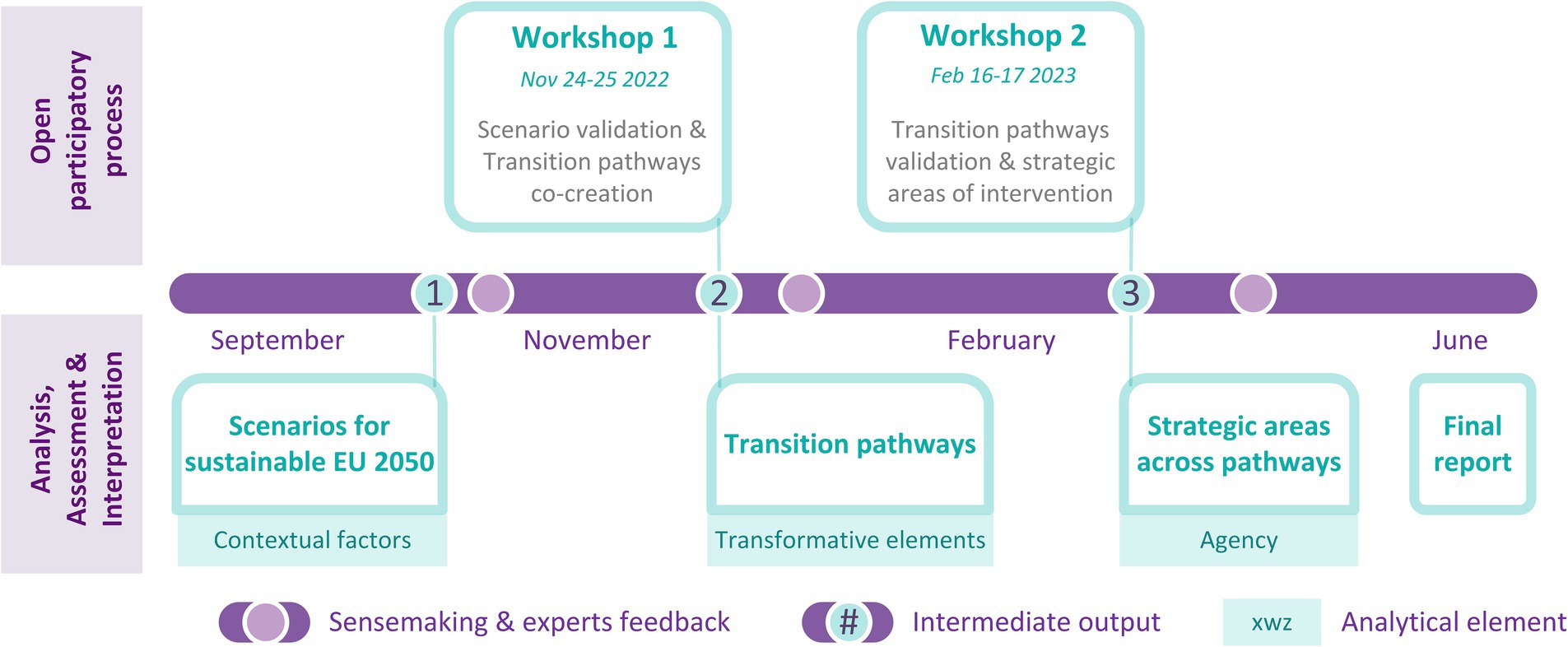

Figure 1 shows the chronological sequence of the foresight process with the intermediate outputs and related analytical element that characterized each step: scenarios (contextual factors), transition pathways (transformative elements) and strategic areas of intervention (agency).

Figure 1. The foresight process and related timeline. Source: Matti et al. (2023).

The process followed several steps and feedback loops to explore possible future changes. The work started in autumn 2022 with the creation of a set of four normative foresight scenarios1 describing different variants of how the EU could achieve sustainability by 2050. The scenarios were validated in a workshop and through exchanges with experts1.. One transition pathway per scenario were then co-created in workshops and validated with experts. Areas for intervention were jointly identified by comparing the pathways in an open participatory process. These areas were further elaborated and analyzed with the help of new experts and secondary research. This process facilitated a reflection on possible EU action to manage social and economic change as part of the transition to sustainability.

The process delivered a coherent sequence of outputs:

1. A set of four foresight scenarios for a sustainable EU 2050

2. A set of four corresponding transitions pathways

3. A set of four clusters of strategic areas of interventions addressing the necessary changes on the way toward sustainability across all pathways

The following sections describe the process by which these outputs has been developed, with a focus on gathering lessons from the use of foresight to develop new actionable knowledge for policy-making on sustainability transitions. It explores the different methods and practises that can help operationalize concepts and methods for innovation in policy making.

The steps of the foresight process applied different methods articulated into a coherent logical sequence. This section describes these individual methods in more detail.

The selected foresight approach required a set of foresight scenarios as a starting point to examine social and economic changes in possible, sustainable futures. To this end, the team took a deductive approach, setting climate-neutrality as the normative condition. The scenarios drew substantially on two sets of existing foresight scenarios that were developed with a focus on sustainability, namely those of a 2015 JRC study on the sustainable economy (Joint Research Centre, 2015) and the European Environment Agency’s (EEA) ‘imaginaries’ for a sustainable Europe in 2050 (European Environment Agency, 2022). Building on this work, two key dimensions were used to structure the scenarios in this study (see Figure 2). These were whether society would become more collaborative/collectivist or individualistic/competitive (vertical axis), and whether or not a broad policy mix would emerge to generate economic signals supporting a transformative shift toward sustainability (horizontal axis).

This scenario-building work used recent methodological developments in a sustainability assessment framework for scenarios SAFS (Arushanyan et al., 2017). The application of the SAFS framework enables the assessment of social, economic and environmental aspects through an inventory of data and assumptions on sustainability in future scenarios compared to the current situation based on the STEEP model (social, technological, environmental, economic, political including additional geopolitical aspects). This generates an inventory of contextual factors that provide a qualitative description of the economic and social risks and opportunities in a future society compared to today (see Supplementary Table A1).

In order to explore a wide range of social and economic changes and interactions, the scenarios were elaborated with the normative condition that the EU would achieve its headline goal of climate neutrality in 2050. As a result, each scenario reveals different trade-offs and synergies in the social and economic dimensions of sustainability.

The overall narrative of each scenario was then compiled by describing the new state of the various relevant contextual factors through a collection of situations resulting from a trigger for change, a specific course of action by a key actor and the associated impacts on the different dimensions of sustainability (social, economic, environmental) structured through the categories of the STEEP model. The foresight process can strengthen the analysis of the combination of interventions in different policy areas and in this way help to illustrate the systemic aspect of policy mixes that pave the way to a sustainable future along very different possible pathways (Bontoux and Bengtsson, 2016).

During the participatory scenario validation process, participants challenged and/or reinforced these narratives by introducing new inputs and additional causal effects in a structured way through three simple elements: (1) WHAT - Action/verb, (2) WHO - Actor and (3) HOW - Variable/Result (see Supplementary Table A2). The collective analysis of these elements allowed for new relationships and clustering of new themes that facilitated the subsequent identification of the changes in the transition pathways.

Identifying key areas of strategic policy intervention to spur a desired transition toward sustainability required understanding a range of possible transition dynamics. Such dynamics could be identified by building transition pathways for all the available scenarios. This is a classic exercise in foresight, performed by backcasting from the scenarios in a participatory process. In this context, a sustainability transitions pathway is defined following the application of the strategic foresight process and core concepts from the literature on sustainability transitions (Turnheim et al., 2015). It is considered as a narrative that integrates socio-technical analyses to project future scenarios, set explicit policy goals and assess pathways from the present to these goals. It emphasises synergies and trade-offs, emerging initiatives, system transformations and the scaling of experiments to enable transformative change and successful implementation.

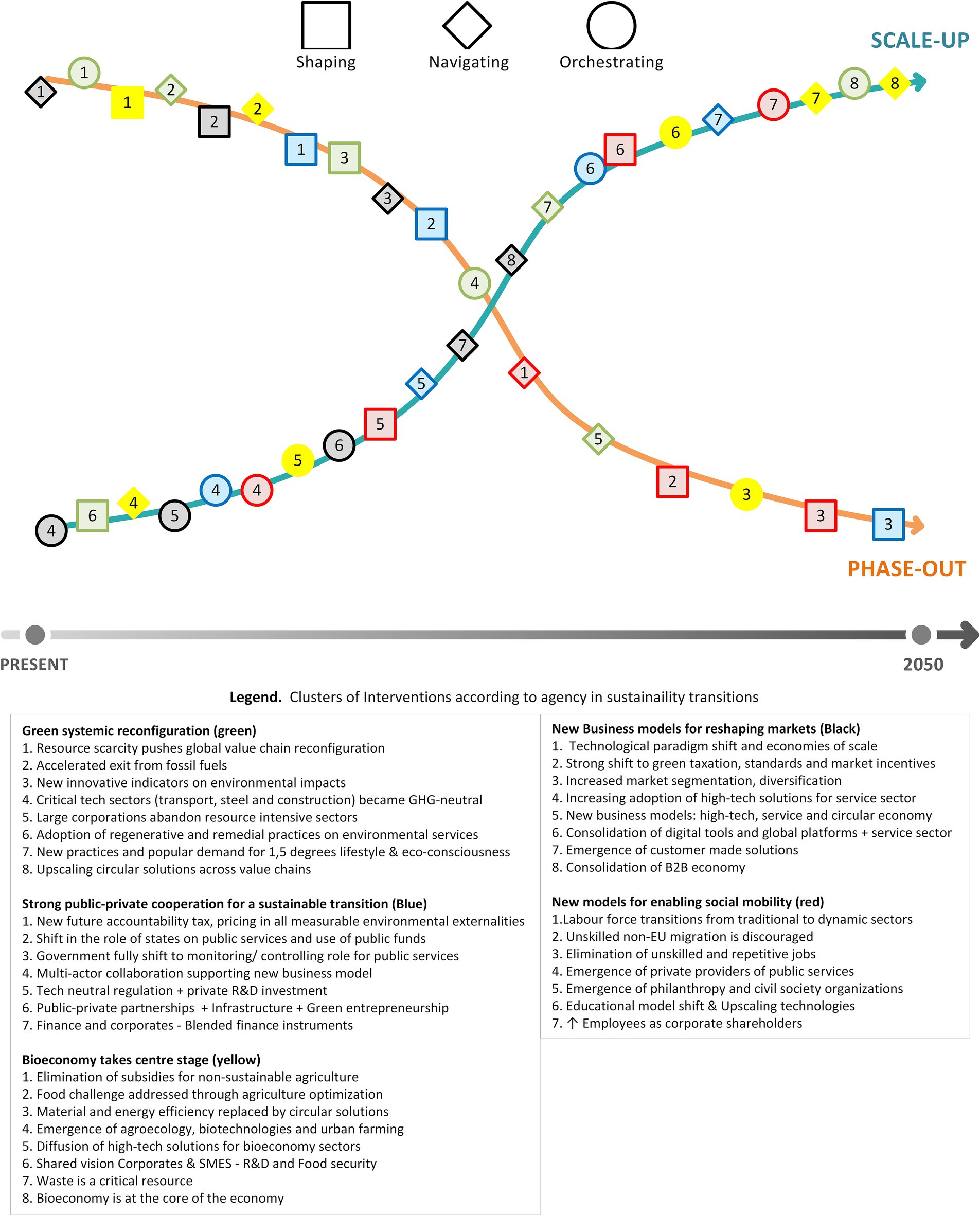

To facilitate the analysis in a sustainability transition perspective, this was done using the X-curve, a sense-making tool that enables the co-creation of collective narratives about system change (Hebinck et al., 2022; Silvestri et al., 2022). This approach had the advantage of combining concepts from academic work on sustainability transitions with foresight as it connects closely to the 3-horizons framework (Wahl, 2017). The 3-horizons framework is an effective method for revealing the dynamics of transformation and exploring the diverging trends of the current system and the challenges to its sustainability into the future (IFF, 2023). It consists in considering a first, short-term time horizon that enables an observation of established and emergent processes and structures and their drivers. A second time horizon, in a medium-term future allows to consider a transition phase, during which some established patterns from the present progressively fade out and previously emerging processes develop. The third, long-term time horizon looks at the establishment of the new situation resulting from the dynamics considered in the previous horizons. The application of the X-curve in this study helped participants visualize the phase out and build up dynamics taking place over the three horizons separately. The first, phase out, describes the patterns of change for destabilising and phasing out practices that are characteristic of the present. The second, build up, describes the patterns of change in terms of the acceleration, emergence and, finally, scaling of new practices that bear witness to the establishment of the new world (see Figure 3). In the context of this study the build-up pattern of change was renamed scale-up to facilitate the understanding of the concept by a broad set of participants over the foresight process.

A transition pathway was developed for each scenario by describing what specific changes would have to happen at different time steps between today and 2050 (explaining causes and consequences for each contextual factor) to reach the corresponding scenario. This produced a specific pattern of change for each scenario.

During the open participatory process, the co-creation of transition pathways started with the extraction of key topics from the analysis of the scenarios. This helped participants understand what had to change, and, as insights were getting deeper, explore synergies and trade-offs over the transition. This exploration was organized in two steps. The first step focused on identifying the activities and practices of the current system that should stop or be changed (phase-out) and which ones should emerge or develop (scale-up). The second step focused on spotting new actions (or interventions) to support, promote or enable the proposed changes (see Supplementary Table A2).

To facilitate understanding and analysis, the process engaged in a concomitant clustering of elements to obtain clear narratives describing patterns of change as well as a set of key transformative elements such as trade-offs, synergies and systemic relations to facilitate the analysis of transition dynamics.

Thanks to the broad scope of the four scenarios and corresponding transition pathways, looking across them made it possible to identify topic areas in which critical change had to happen on the road toward sustainability, even if the specific changes could vary across pathways as part of a broader systemic policy mix. This was instrumental to shed light on what it would take from a policymaking perspective to engage in successful sustainability transitions toward 2050 depending on the selected course toward the future. These areas were first identified collectively during the open participatory process (See Supplementary Table A3).

First, the transformative elements of each pathway were highlighted so that the experts could analyze and compare them from a systemic point of view. The identified areas were then ranked according to which would be most critical for policy action across all pathways to move sustainability transitions forward. The experts were then asked to address the emerging systemic policy mixes by highlighting synergies, tradeoffs and emerging processes that could activate change and provide direction for the transition.

The experts were then asked to propose interventions in each cross-cutting area that would facilitate sustainability transitions. To make these proposals concrete, they were asked to describe (1) WHAT - Action/verb, (2) WHO - Actor and (3) HOW - Variable/Result. They were guided by a template identifying different aspects3 of potential interventions. Emphasis was put on understanding the synergies between the actions in terms of the pattern of change (i.e., Scale-up/Phase out).

The different elements describing these strategic areas for intervention were then documented and analyzed using current data and trends. The areas of intervention were then grouped into four systemic clusters to facilitate understanding. This made it possible to discuss the agency of EU actors in managing the changes needed to promote sustainability transitions and, by doing so, improve the understanding of the evolution of the capacity of actors to shape, navigate and orchestrate the change process overtime could determine the scope and scale of the mix of interventions that can be implemented.

As mentioned earlier, an essential goal of the project was to generate actionable knowledge, i.e., information and understanding that would help policymakers concretely in their capacity to develop the systemic policy mixes that are needed to put the EU on a path toward a fair and sustainable future. The foresight process delivered on this objective in two main ways: by shedding light on the nature of changes needed to engage successfully in the transition toward sustainability and by identifying who could or should do what to that end.

Transitioning successfully toward requires speed and scale in a range of critical changes that need to take place in a coordinated fashion. The urgency of climate change, environmental degradation and resource depletion requires rapid activation of systemic change processes, particularly in scaling up sustainable initiatives and phasing out unsustainable practices. This not only requires enhancing existing policies for sustainability, but also rethinking their interactions across different timescales, sectors and levels of government. When comparing the four transition pathways, we can immediately see what different approaches to systemic change lead to, particularly in terms of scaling up and phasing out efforts. These pathways illustrate the implications that different strategies for addressing sustainability transitions have for the agency of various actors and for multi-level governance.

Scaling up sustainable practices is essential. This includes expanding renewable energy sources, promoting frugality in addition to energy and material efficiency and investing in infrastructures for sustainability. Such initiatives need to be supported by coherent policy frameworks that incentivize innovation and collaboration between different stakeholders. The different foresight scenarios illustrate various types of scaling-up and what they lead to. In the pathway toward the ‘Eco-states’ scenario, for example, the focus is on expanding government intervention, and changing government behavior coupled with investing in green technologies. For the ‘Green business boom’ scenario, the pathway shows an expansion of market-driven solutions and private sector innovation. In contrast, the ‘Glocal Eco-world’ pathway scales up grassroots initiatives and local solutions.

However, phasing out unsustainable practices—such as dependence on fossil fuels, wasteful consumption and harmful agricultural practices—is equally important. This requires a systematic dismantling of existing structures that perpetuate environmental degradation, which can only be achieved through the coordinated efforts of governments, businesses and civil society. The efforts to phase out unsustainable agricultural practices, for example, vary in intensity and approaches between the scenarios. The ‘Eco-states’ pathway shows the most aggressive path toward reform, with governments explicitly discouraging unsustainable practices through regulation and taxation. The ‘Greening through crisis’ scenario demonstrates a more reactive exit approach driven by external pressures and constraints. The ‘Green business boom’ pathway relies on market forces to phase out unsustainable practices. The ‘Glocal eco-world’ pathway can appear on the surface as engaging in a more organic exit, with communities shifting toward sufficiency and local resilience, but in all likelihood, it would be in a post-apocalyptic world in which previous systems would have been profoundly disrupted.

While all pathways show both scale-up and phase-out processes, the emphasis on phase-out efforts is very different. The ‘Eco-States’ and ‘Glocal Eco-World’ pathways show the most comprehensive phase-out strategies, albeit through different mechanisms: it results from a visionary and voluntary approach in the former and from a post-trauma survival strategy in the latter. This comparison underscores the richness of considering multiple possibilities for achieving sustainability transitions to be able to reflect on the possible roles of different actors and levels of government in promoting systemic change.

Developing transition pathways for the four scenarios and looking across them led to the identification of critical domains in which the type of change that would happen would have an outsize influence on the transition path. These critical domains were called “strategic areas of intervention” because they should be the focus of policy intervention when actively choosing a specific path toward sustainability. Considering them simultaneously also offers a tool to increase the policy coherence essential to engaging successfully in systemic change. These strategic areas of intervention, e.g., New Social Contract for Sustainability, Governance for Sustainability, People and Economy for Sustainability and Global Perspective on Sustainability, also provide a crucial window on the possible agency of the key actors in sustainability transitions. This concept makes it possible to look at the collective capacity of different actors to drive transformative change.

The roles of the multiple actors that must be mobilized and their interactions are critical to promoting a systemic approach to sustainability that reflects the interconnectedness of social, economic, and environmental systems. In the “Green Business Boom Transition Pathways” (see Figure 4), for example, the different aspects for addressing agency in sustainability transitions (shaping, navigating and orchestrating) take the form of a series of intervention clusters that correspond to a systemic policy mix in which each actor plays a different role to scale-up new practises and phase out unsustainable ones over time. More specifically, the interventions in the area of ‘Strong public-private collaboration for a sustainable transition (blue)’ show that the role of the government is shifting in terms of the use of public funds and more relevant monitoring activities, with the private sector playing a more important role in financing and providing public services.

Figure 4. Green business boom transition pathways - patterns of change according to agency type in sustainability transitions.

In this sense, the government’s measures under the ‘Bioecenomy takes centre stage (yellow)’ area aim to shape the sector by removing market-distorting subsidies, while a shared vision of corporations and SMEs serves as a strategic measure to navigate the changes in the new sector. Finally, the ‘New models for enabling social mobility (red)’ cluster emphasises shaping and orchestration with new roles for the private sector, philanthropy and civil society organizations in public services, while illustrating a new relationship between companies and employees, who are increasingly becoming shareholders in the company.

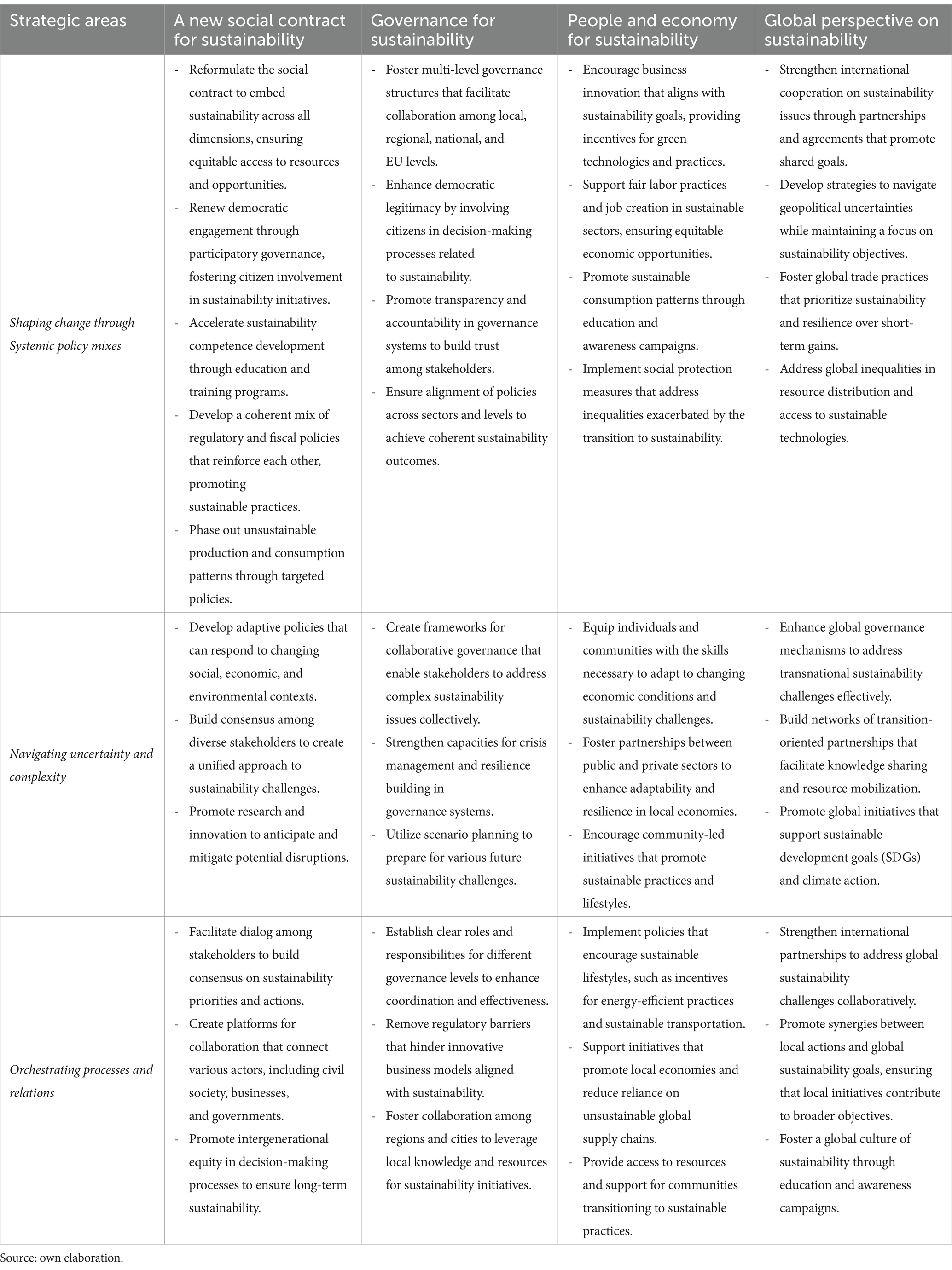

From a broader perspective across the different scenarios, Table 2 provides a comparative analysis of the strategic areas of intervention identified in this study, highlighting the diversity of interventions proposed through the three types of interventions in sustainability transitions defined in this paper: (1) Shaping change through Systemic Policy Mixes, (2) Navigating Uncertainty and Complexity and (3) Orchestrating Processes and Relations. Applying this approach across pathways, helps put in evidence the need for a multi-stakeholder approach in each strategic area of intervention. Not only does this type of analysis show that effective change requires the collaboration of different stakeholders, including governments, businesses, civil society and citizens, but it also helps to see that collective agency is essential for shaping change, managing uncertainty, dealing with complexity, and governing processes and relationships.

Table 2. Strategic areas of Interventions distributed across the three types of interventions in sustainability transitions.

For example, this work brought to the fore that shaping the change necessary for sustainability transitions requires systemic policy mixes which themselves require a collaborative approach in which governments, civil society and the private sector work together to develop and implement policies that promote sustainable practices. This can ensure that stakeholders develop a good understanding and a sense of ownership of sustainability goals. Improving the sustainability literacy of citizens and businesses is crucial to enable them to actively participate in change. Moving away from unsustainable production and consumption patterns depends on a coherent mix of regulatory and fiscal measures that not only incentivises sustainable behavior but also removes existing barriers to change. This foresight work shows that this could require the formulation of a new social contract.

Navigating the uncertainty and complexity of the transition to sustainability requires a robust framework for collective action by different stakeholders. Building new capacities for action through consensus-based partnerships enables stakeholders to manage uncertainty effectively. This collaborative approach fosters resilience and enables communities and organizations to adapt to disruption and align change with long-term sustainability goals. By fostering transition-oriented partnerships, stakeholders can share knowledge and resources, enhancing their ability to respond to emerging challenges. Strategic foresight tools such as scenario planning can help consider a range of potential disruptions and inform decision-making processes. A key element identified in the cross-cutting analysis is the capacity of actors, in particular governments and private sector actors, to navigate uncertainty by maintaining an overall course toward sustainability to the extent that crisis events and shocks can be used to contribute to the reorientation toward sustainability, rather than resorting to unsustainable practices.

Orchestrating processes and relationships is critical to fostering effective multi-level governance models that facilitate the transition to sustainability. The role of different actors—governments, businesses, civil society and local communities — plays a critical role in creating synergies and enhancing collaboration across different levels and sectors. By enabling portfolios of systemic interventions, actors can address the various sustainability challenges in a coherent way. This includes removing barriers to innovative business models and creating an environment conducive to collaboration in which new ideas and practises can flourish. Strengthening the role of regions and cities is crucial, as they are often at the forefront of implementing sustainability initiatives and can utilize local knowledge and resources.

In shaping change, the emphasis on a new social contract underscores the importance of inclusivity and democratic engagement, ensuring that all voices are heard in the sustainability discourse. Navigating uncertainty necessitates adaptive governance that can respond to the complexities of modern challenges, fostering resilience through collective action and innovative partnerships. Orchestrating processes and relations is vital for creating synergies between local and global efforts, reinforcing the notion that sustainability is a shared responsibility. The overall comparative results illustrate that agency for sustainability transitions is not just about individual actions but about the collective capacity to act in concert toward a common goal, requiring a systemic policy mix that transcends traditional silos and fosters holistic approaches to sustainability.

The foresight process and its use of academic concepts from sustainability transitions studies led to rich discussions on the multiple changes that sustainability transitions would entail and on what it would take to make these changes happen. This generated new knowledge among the participants that could be captured in the study report and inform policymaking.

Figure 5 summarize how the different outputs of the foresight process contributed to generate useful insights on change processes through a sustainability transitions lens. In this context, three important lessons were learned on critical aspects of implementing a foresight process addressing sustainability transitions.

The foresight process facilitated the interplay between futures thinking and sustainability transitions in several ways. First, using the Sustainability Assessment Scenario Framework and its inventory of contextual factors structured through the STEEP model, made it possible to build a future oriented narrative by combining trigger elements, actions and actors with a continuous analysis of systemic relations between the different STEEP categories.

Second, using the X-curve and its ‘creation/destruction’ duality for developing transition pathways through backcasting facilitated the identification of critical changes, synergies and trade-offs. In both cases, the foresight process facilitated a straightforward operationalization of the discussion on change through simple guiding questions and three instrumental, granular elements that were applied throughout the process: (1) WHAT - Action/verb, (2) WHO - Actor and (3) HOW - Variable/Result. This approach facilitated a systems perspective on possible, future change processes.

The new insights into how change can happen show how actions taken today determine our ability to act tomorrow. In this sense, the foresight process has strengthened the analysis of the combination of interventions in different policy areas. This helped to illustrate the systemic effects of policy mixes along very different possible pathways, especially, it has enabled a discussion on the scale, complexity and speed of change. This future perspective on dynamic policy coherence shows that systemic consequences are often unpredictable and require regular adjustments. The challenges are large, but the results of this study show that the EU can use the available knowledge and tools, mechanisms and instruments to steer its own course in sustainability transitions.

Moreover, the described strategic foresight framework enabled a detailed discussion on the composition and interrelation of potential interventions through instrumental exercises that contribute to a more operational discussion on change process through simple WHO, WHAT HOW questions, while improving the understanding of how policy mixes generate synergies between actors with different capacity to act. The clustering and analysis contributed to illustrate examples of how policies to enable sustainability transitions should target different levels of society in a coordinated way.

The Sustainability Transition Framework provided a conceptual grid for considering agency while the foresight process facilitated the necessary discussion on the capacities and resources of different actors (e.g., policy makers at all levels of government, civil society, business leaders, etc.) to engage in transformative change. This interplay between sustainability transitions and foresight has delivered important lessons on the agency of EU actors in sustainability transitions. First, the agency of EU actors can evolve over time. Second, the evolving distribution of agency among EU actors can support society to take new actions in an uncertain situation. Finally, the insights on the strategic areas of intervention show that this raises the question of which agency the EU wishes to promote, depending on the long-term vision adopted ultimately. In answering this question and shaping the portfolio of systemic interventions, it is crucial to consider that the different types of interventions within Shaping, Navigating and Orchestrating are mutually reinforcing and enable the building of new agency between different actors.

The insights presented in this paper has provided new evidence for the use of foresight to develop new actionable knowledge for policymaking on sustainability transitions. It has shown that combined methods can be used to operationalize concepts at a different level of complexity. The range of concepts that can be used in the foresight process to generate actionable knowledge ranges from the basic notion of systemic relationships and the change process to more sophisticated ideas that require deeper analysis, such as the systemic policy mix and agency of different actors to act in sustainability transitions. In this sense, this paper presented the implementation of an analytical loop that starts with the conceptualization of change through the lens of sustainability transition, which is later operationalized during the foresight process using tools complemented by simple questions such as (1) WHAT - action/verb, (2) WHO - actor and (3) HOW - variable/result to build the narrative for the transition pathways. Ultimately, the clustering and analysis of elements in the different areas of intervention enabled the re-conceptualization of the results in terms of the different agency of actors (i.e., shaping, navigating, orchestrating), which provided new insights for informing policy.

The application of these combined methods can facilitate innovation in the policy-making process to improve understanding of transformative change and, simultaneously, promote the discussion and exploration of strategic areas of intervention. The added value of combining these approaches lies, in particular in strengthening the ability to untangle complex and wide-ranging change processes. Applying foresight methods improved the ability to capture complexity and a wide range of possible changes. Embedding them in change management concepts for sustainability transitions enabled the project to generate systemic knowledge that can be applied strategically for policy (Matti et al., 2023).

The previous sections describe the clear strengths of this strategic foresight framework and Section 6 demonstrates its ‘portability’ through a brief description and comparative analysis of early applications in three very different contexts. However, in view of the complexity of the issues that this approach addresses, some limitations can be highlighted.

First, to ensure a sufficiently high quality of output, the process must engage with a sufficiently large and broad set of participants with a high level of relevant knowledge, representing all the key stakeholders and with the necessary diversity of perspectives. This is best foreseen (mapped) in the very early stages of project scoping and design. This was achieved in this case thanks to the reach of the European Commission across Europe and to the availability of significant internal expertise.

Second, maximising the use of good quality information and data in the process while maintaining a continuous knowledge management task over the entire process increases the quality of output (Matti et al., 2022). However, this requires time and resources that are not always available. In our case, this was achieved through several weeks of desk research by the various members of the study team with support from experts from the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC). However, no attempt was made to engage in quantitative modeling work as time and resources were not available.

Third, running this process successfully also requires not only clear definitions and explanations of the concepts that are applied but also expertise in running participatory foresight processes to ensure that all participants can fully engage with a solid shared understanding of what is being discussed. The strong conceptual basis for this work both from academic work on sustainability transitions and on the long-established foresight practice ensured a solid basis for the first aspect. Regarding the expertise in running the process, we had the privilege of being able to count on the solid experience of the staff from the EU Policy lab at the JRC.

All these requirements are clearly explained in the foresight process description and the JRC team can provide material and support to people who are interested in running this process elsewhere.

After the successful completion of the original process, several requests for strategic foresight support were received by the EU Policy Lab. This offered the opportunity to test the concept further and streamline it to apply it to other complex issues through the design of tailored made strategic foresight exercise enabled by co-creation processes (Matti et al., 2022; Matti and Bontoux, 2024). The three examples described below provide a first validation of the relevance and robustness of this novel strategic foresight framework.

Over the period 2023–2024, UNEP engaged into an in-depth strategic foresight exercise to inform its long-term strategic reflection (UNEP and ISC, 2024). This process included horizon scanning and the development of foresight scenarios on human wellbeing and planetary health with a global perspective. To be able to take into consideration the diversity of situations around the world while preserving a certain coherence of input into the foresight process, the application of SAFS through the co-creation of an inventory of contextual factors addressing multiple sustainability dimension (Arushanyan et al., 2017) from these global scenarios was used to create a common basis for the design and implementation of regional workshops. The regional workshops made it possible to cater for very diverse sociocultural contexts as well as important differences in perception, knowledge acquisition, institutional capacity, motivation and resources around the world.

These workshops were performed with expert participants from the six UNEP world regions: Europe, Africa, North America, West Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean and Asia-Pacific. This was important to put global findings in perspective and uncover dynamics, issues, risks, and opportunities specific to each region.

To adapt to UNEP’s needs and constraints, the original process was transformed into a 1.5 day workshop to be repeated across world regions and rolled-out in three main steps:

1. Review, understand and contextualize the four UNEP scenarios. Participants were invited to familiarize themselves with the four scenarios, to validate them, and to translate them into how they would play out in the context of their world region.

2. Determine what sequence of changes could lead us from the present to each of the four global scenarios. The purpose of this exercise was to uncover the potential for disruption to the state of the environment, planetary health and human well-being depending on the trajectory being considered.

3. Identify possible key interventions that would be required to address the main threats to human wellbeing and planetary health identified in each scenario for the region being considered. This step first made use of the strategic reflection of the participants to identify how each of the main changes emerging in the trajectories toward each scenario could affect sustainable development in the region. Then participants were asked to propose specific policy interventions to address the changes perceived as affecting sustainable development negatively.

UNEP rolled out this process across all six world regions and extracted the knowledge thus generated to inform its general assembly.

Shortly after the completion of the original process, the European Commission’s Directorate General for the Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs (DG GROW) contacted the EU Policy Lab to reflect on the future of the EU Single Market and industrial policy. The main objectives were to:

1. Identify the most likely and/or most impactful aspects of the possible futures for the work of DG GROW;

2. Discuss future directions for policies that would allow DG GROW to take advantage of the possible evolution of events.

The request came with a tight time-frame for delivery, few resources, and a requirement to engage with the whole management of the organization (over 80 people) at once. The EU Policy Lab decided to transform the SFR23 foresight process into a one-day programme and to use the reference scenarios for the EU Global Standing in 2040 (Vesnic Alujevic et al., 2023) developed previously by the JRC as they were better suited to discussing the chosen topic.

To tailor the workshop to the needs and constraints of DG GROW, the original process was adapted and rolled-out in four steps:

1. Explore and understand the 4 reference foresight scenarios, to grasp their respective implications for the Single Market and industrial policy. For doing so, by following the SAFS approach, the scenarios were unpacked and simplified through an inventory of contextual factors following 8 dimensions agreed with DG GROW.

2. Imagine how the EU Single Market and industrial policy would look like under each scenario, in sufficient detail.

3. Determine the pathways that could lead from the present to each of the alternative scenarios on the EU Single Market and Industrial Policy using the “X-curve.”

4. Look across all pathways to identify the key strategic domains of policy intervention, the corresponding drivers of change and the policy leverage points.

All steps were supported by relevant templates.

Over 80 GROW colleagues attended including both DDGs and several directors and contributed very actively to the discussions. This large number required to run the participatory process in two parallel tracks with periodic reconciliation of results. Overall, and despite some initial scepticism, the participants engaged fully and completed all steps successfully. At the end of the day, the objectives of the exercise had been met and the feedback from the participants was overwhelmingly positive. The key domains for policy intervention that were proposed by the participants could be grouped around 8 areas: institutional, financial, sectorial, competition policy, external relations, administrative burden, sustainability, skills, and fairness/cohesion.

While the discussion brought many classic topics of discussion to the fore, it put them into different contexts, put them in a systemic perspective, made trade-offs clear and led to deeper strategic reflections with clear policy and political relevance. It also broadened the reflection to consider coherence with action in other policy areas.

The results of the foresight exercise were then presented to all interested staff of DG who did not take part in the workshop.

During 2024, the European Topic Centre on Sustainability transitions implemented a project to explore multiple pathways and policy mixes for transforming European food systems. The project demonstrated how strategic foresight can effectively address complex systemic challenges through structured stakeholder engagement. The process combined three complementary methodological approaches to explore future pathways and identify strategic intervention areas for food system transformation (Lorenz et al., in press).

In the first phase, the Future Wheel method was employed during an initial workshop with the EIONET Food Systems Group, EEA officials, and selected experts. The Future Wheel facilitated systematic examination of scenario sustainability and completeness, with particular attention to environmental and social dimensions, including key contextual factors such as justice, equity, food safety, and food security. This brainstorming structured by contextual factors (i.e., SAFS) helped participants explore direct and indirect consequences of potential changes in the food system. The use of the Future Wheel as a visual mapping artefact enabled participants to move beyond linear thinking and identify complex interdependencies within the food system.

The second phase utilized the X-curve framework to analyze transition pathways, explicitly considering the interplay between building up sustainable practices while phasing out unsustainable elements of the current food system. Workshop participants identified key elements requiring change, new activities for scaling up, and existing practices to phase out. The framework highlighted the temporal sequence of policy actions needed across different transition phases - emergence, acceleration, and stabilization. This analysis revealed the importance of developing effective phase-out strategies alongside innovation support, particularly regarding agricultural subsidies and supply chain transformations.

The final phase employed morphological analysis to explore policy combinations systematically across ten key dimensions of food system governance. The analysis framework emerged through a bottom-up approach informed by the X-curve workshop outcomes. Policy options were evaluated through pairwise consistency assessments using a three-point scoring system, leading to the identification of four distinct yet coherent policy pathways: Nature First, High Tech, Top-down, and Mixed Approaches. A second workshop with the EIONET Food Systems Group validated these pathways and assessed policy options for feasibility and desirability.

The three examples demonstrate the adaptability of the strategic foresight framework to different applications and its transferability to other practitioners while maintaining core methodological elements. The UNEP case emphasized regional adaptation of global scenarios through structured workshops, enabling consideration of diverse sociocultural contexts and institutional capacities as well as to ability of others to lean the process and run it autonomously. The EU Single Market application focused on rapid engagement with large management groups, using reference scenarios to facilitate strategic discussion under time constraints. The application to the food system showcased a more comprehensive approach, combining detailed stakeholder engagement with systematic policy analysis.

Common elements across cases include the use of participatory methods to build shared understanding such as the use of an inventory of contextual factors (i.e., SAFS) to unpack the scenarios, structured frameworks to explore transition pathways, and systematic approaches to identifying strategic interventions. However, they differ largely in scope (global vs. European vs. sectoral), timeframe (from one-day workshops to multiple-month engagements), and depth of policy analysis (from strategic directions to detailed policy mixes). Table 3 provides a comparative analysis of how the strategic foresight framework was adapted to different contexts. While all cases maintain core methodological elements, they demonstrate distinct approaches to scenario development, pathway creation, and strategic intervention identification, reflecting varying institutional settings, timeframes, and stakeholder configurations. The comparison illustrates the framework’s flexibility while maintaining methodological rigor.

The three cases demonstrate distinct patterns of agency mobilization in sustainability transitions. In the UNEP case, agency was distributed across multiple regional bodies, with international organizations acting as coordinators while empowering regional stakeholders to contextualize global scenarios. This multi-level agency approach enabled adaptation to diverse institutional capacities and cultural contexts.

The EU Single Market case showcased institutional agency at the European level, with DG GROW mobilizing over 80 management-level actors to shape strategic directions. This demonstrated how concentrated institutional agency could be effectively deployed even under tight time constraints, while still maintaining inclusivity in the process.

The food system case revealed a more complex interplay of agency, involving scientific institutions (EEA, EIONET), policy actors, and diverse stakeholders across the food value chain. This distributed agency model enabled a broader perspective on system transformation by engaging actors with different capacities and roles - from primary producers to consumers, and from local to EU-level institutions.

The novel foresight framework described in this paper emerged from a study that focused on understanding the key role the social and economic dimensions have in the transition of the EU toward sustainability. Its objective was to make these dimensions salient within the inherently complex, entangled and multi-layered changes that will unavoidably take place in the sustainability transitions. This framework was implemented through a holistic approach that showed the dynamics and interconnectedness of the social, economic and environmental systems as applied to the EU. By revealing how the concurrent scaling up and phasing out of individual phenomena could lead to the radical transformation of the EU toward different forms of sustainability, the application of the foresight framework enabled the study team to generate strategic insights that provided the future-oriented backbone for the preparation of the European Commission’s 2023 Annual Strategic Foresight Report.

The application of the original foresight framework delivered actionable knowledge through several outputs: a set of four scenarios for a climate-neutral, sustainable EU in 2050 structured through and inventory of contextual factors following the SAFS approach; a set of four corresponding transitions pathways; and a systemic policy mix conformed by a set of strategic areas of intervention covering a new social contract, governance, people and the economy, and the global perspective. The analysis of the strategic areas of intervention in the perspective of the various scenarios and transition pathways, has enabled the generation of new actionable knowledge to better understand the agency of the various actors in the sustainability transitions.

The step-by-step development of the scenarios and transition pathways, helped by the application of the X-Curve, made it possible to reach the required depth of analysis. This way of separating phase-out and emergence dynamics by combining transition thinking with the 3 Horizons framework often used in foresight helped participants through a difficult reflection exercise. This way of addressing transition dynamics facilitated the analysis of trade-offs, bottlenecks and blind spots along transition pathways, delivering strategic insights for policymaking in a very complex domain. It also demonstrated not only the importance of systemic policy mixes for a successful transition, but also provided tools to generate the required systemic understanding to know what to put into these policy mixes.

The successful implementation of this foresight framework across global and thematic contexts validates its methodological robustness and demonstrates its versatility. The framework has proven effective in helping stakeholders develop systemic understanding and engage in transformative change, promoting both immediate action and long-term resilience. Its successful application across diverse settings - from the EU Single Market to food systems to UNEP’s global perspective - demonstrates its adaptability while maintaining methodological integrity. The process has proven particularly valuable in enabling organizations to engage with complex sustainability challenges through structured yet flexible approaches to scenario development and policy recommendation formulation.

The framework reveals specific challenges in mobilizing and coordinating different forms of agency for sustainability transitions. A key challenge is balancing the agency of established institutional actors with emerging stakeholders who may lack formal authority but bring crucial perspectives and capabilities. In view of the difficulty encountered by governments around the world to engage in sustainability transitions, help with in-depth reflection on the issue should be broadly welcome. Indeed, as there is no one-size-fits-all way forward, this type of methods provides both the structure and the flexibility to generate original reflections adapted to any geographical and political context.

The framework also presents unique opportunities to enable systematic incorporation of diverse stakeholder perspectives while maintaining analytical rigor through the interplay of multiple entry points for stakeholder engagement (i.e., scenarios, transition pathways, interventions and policy), desk research and knowledge co-creation to ensure systematic policy development. Furthermore, main aspects of the framework’s flexibility such as the use of contextual factors to structure scenarios (i.e., SAFS) and the use of X-Curve for co-creating narratives on pathways from multiple angles allows adaptation to different contexts while maintaining methodological coherence, as demonstrated across the three cases.

In view of the complexity of the issues that this approach addresses, some limitations can be highlighted. First, to ensure a sufficiently high quality of output, the process must engage with enough participants with a high level of relevant knowledge, representing all the key stakeholders and with the necessary diversity of perspectives. This is best foreseen (mapped) in the very early stages of project scoping and design. Second, maximising the use of good quality information and data in the process increases the quality of output. However, this requires time and resources that are not always available. Third, running this process successfully also requires clear definitions and explanations of the concepts that are applied to ensure that all participants can fully engage on the basis of a solid shared understanding of what is being discussed. The study identifies a space for further development of future-oriented co-creation processes by exploring the interplay between foresight methods and the Sustainability Transitions Framework. It also highlights the potential for using transition pathways to inform and structure a discussion over the long-term change needed, the systemic policy mixes required and the agency of different actors on the way toward sustainability. Finally, the methodology’s flexibility allows for adaptation to different institutional contexts while maintaining coherence in how agency is mobilized and coordinated. The cases demonstrate how the framework can help overcome traditional limitations in policy planning where different forms of agency can be effectively combined to drive sustainability transitions. This is particularly relevant for EU-level coordination, where success depends on mobilizing complementary forms of agency across governance levels.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

CM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. KJ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors would like to thank Petra Goran, Alberto Pistocchi and our regretted colleague Maurizio Salvi for their significant contribution in realising the key findings of the European Strategic Foresight Report 2023. We would also like to acknowledge the leadership of Anne-Katrin Bock and Thomas Hemmelgarn, who advised us on the institutional and technical aspects of the process to develop the scientific basis for policy development.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2025.1507708/full#supplementary-material

1. ^Normative (or prescriptive) scenarios describe a prespecified future, presenting “a picture of the world achievable (or avoidable) only through certain actions. The scenario itself becomes an argument for taking those actions” (Ogilvy, 2002).

2. ^The JRC, in close collaboration with the Commission’s Secretariat-General, involved a broad range of expertise in the open participatory process with:1. Two face-to-face workshops with a broad range of experts from the European Commission, EU agencies, academia, think tanks, foresight professionals, social partners and civil society on 24–25 November 2022 (from scenarios to pathways) and 16–17 February 2023 (from pathways to cross-cutting areas),2. Online workshops with experts from across the JRC covering relevant fields and3. Consultations in the context of European Commission’s networks on strategic foresight including representatives of Member States and Commission services, bilateral meetings on specific topics with experts from across the Commission, EU agencies, think tanks and other organizations.

3. ^Different aspects used for exploring potential interventions: (1) Constants, Parameter and numbers, (2) Infrastructures (digital/physical), (3) information flows, (4) Rules, (5) Governance, (6) Goals and (7) Paradigm (Scale-up vs. Phase-out). See Supplementary Table A5.

Alkemade, F., and de Coninck, H. (2021). Policy mixes for sustainability transitions must embrace system dynamics. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 41, 24–26. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2021.10.014

Alvial Palavicino, C., Matti, C., and Brodnik, C. (2023). Co-creation for transformative innovation policy: an implementation case for projects structured as portfolio of knowledge services. Evidence Policy 19, 323–339. doi: 10.1332/174426421X16711051078462

Arushanyan, Y., Ekener, E., and Moberg, Å. (2017). Sustainability assessment framework for scenarios – SAFS. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 63, 23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2016.11.001

Bontoux, L., and Bengtsson, D. (2016). Using scenarios to assess policy mixes for resource efficiency and eco-innovation in different fiscal policy frameworks. Sustain. For. 8:309. doi: 10.3390/su8040309

Bulkeley, H. (2005). Reconfiguring environmental governance: towards a politics of scales and networks. Polit. Geogr. 24, 875–902. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2005.07.002

Contesse, M., Duncan, J., Legun, K., and Klerkx, L. (2021). Unravelling non-human agency in sustainability transitions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 166:120634. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120634

European Commission (2023). Sustain. Dev. Available at: https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/development-and-sustainability/sustainable-development_en (Accessed January 21, 2025).

European Environment Agency. (2022). The ‘scenarios for a sustainable Europe in 2050’ project. Publications Office. Available at: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/scenarios-for-a-sustainable-europe-2050/the-scenarios (Accessed January 21, 2025).

Fischer, L.-B., and Newig, J. (2016). Importance of actors and Agency in Sustainability Transitions: a systematic exploration of the literature. Sustain. For. 8:476. doi: 10.3390/su8050476

Ghosh, B., Kivimaa, P., Ramirez, M., Schot, J., and Torrens, J. (2021). Transformative outcomes: assessing and reorienting experimentation with transformative innovation policy. SSRN Electron. J., 48:739–756. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scab045

Gomes, L. A. D. V., and Barros, L. S. D. S. (2022). The role of governments in uncertainty orchestration in market formation for sustainability transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 43, 127–145. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2022.03.006

Grillitsch, M., Rekers, J., Asheim, B., Fitjar, R. D., Haus-Reve, S., Kolehmainen, J., et al. (2024). Patterns of opportunity spaces and agency across regional contexts: conditions and drivers for change. Environ Plan A 0. doi: 10.1177/0308518X241303636

Grillitsch, M., and Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 44, 704–723. doi: 10.1177/0309132519853870

Grin, J., Rotmans, J., Schot, J., Geels, F. W., and Loorbach, D. (2011). Transitions to sustainable development: New directions in the study of long term transformative change (first issued in paperback) : Routledge.

Grubb, M., McDowall, W., and Drummond, P. (2017). On order and complexity in innovations systems: conceptual frameworks for policy mixes in sustainability transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 33, 21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2017.09.016

Hebinck, A., Diercks, G., von Wirth, T., Beers, P. J., Barsties, L., Buchel, S., et al. (2022). An actionable understanding of societal transitions: the X-curve framework. Sustain. Sci. 17, 1009–1021. doi: 10.1007/s11625-021-01084-w

Howlett, M., and del Rio, P. (2015). The parameters of policy portfolios: verticality and horizontality in design spaces and their consequences for policy mix formulation. Environment Plan C 33, 1233–1245. doi: 10.1177/0263774X15610059

IFF. (2023). Three horizons. International Futures Forum. Available at: https://www.iffpraxis.com/3h-approach

Izulain, A., Aranguren, M. J., and Wilson, J. R. (2024). Place-leadership and power in the futures domain: the case of Euskadi 2040. Eur. Plan. Stud. 32, 2124–2141. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2024.2339927

Joint Research Centre. (2015). 2035: Paths towards a sustainable EU economy: Sustainable transitions and the potential of eco innovation for jobs and economic development in EU eco industries 2035. Luxembourg: Publications Office. Available at: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/372089

Joint Research Centre. (2021). Addressing sustainability challenges and sustainable development goals via smart specialisation: Towards a theoretical and conceptual framework. Luxembourg: Publications Office. Available at: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/410983

Jørgensen, U. (2012). Mapping and navigating transitions—the multi-level perspective compared with arenas of development. Res. Policy 41, 996–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.03.001

Kern, F., Rogge, K. S., and Howlett, M. (2019). Policy mixes for sustainability transitions: new approaches and insights through bridging innovation and policy studies. Res. Policy 48:103832. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2019.103832

Matti, C., and Bontoux, L. (2024). Foresight as a catalyst for systemic change and co-creation in public policy. European Public Mosaic, Issue 24. Public Administration School of Catalonia

Matti, C., Jensen, K., Bontoux, L., Goran, P., Pistocchi, A., and Salvi, M. (2023). Towards a fair and sustainable Europe 2050: Social and economic choices in sustainability transitions publications. Luxembourg: Office of the European Union.

Matti, C., Rissola, G., Martinez, P., Bontoux, L., Joval, J., Spalazzi, A., et al. (2022) in Co-creation for policy: Participatory methodologies to structure multi-stakeholder policymaking processes. eds. C. Matti and G. Rissola (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union).

Ogilvy, J. (2002). “Futures studies and the human sciences: the case for normative scenarios” in New thinking for a new millennium (Routledge), 40–97.

Ottosson, M., Magnusson, T., and Andersson, H. (2020). Shaping sustainable markets—a conceptual framework illustrated by the case of biogas in Sweden. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 36, 303–320. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2019.10.008

Pereira, L., Karpouzoglou, T., Doshi, S., and Frantzeskaki, N. (2015). Organising a safe space for navigating social-ecological transformations to sustainability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12, 6027–6044. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120606027

Pesch, U. (2015). Tracing discursive space: agency and change in sustainability transitions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 90, 379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2014.05.009

Rotmans, J., Kemp, R., and van Asselt, M. (2001). More evolution than revolution: transition management in public policy. Foresight 3, 15–31. doi: 10.1108/14636680110803003

Silvestri, G., Diercks, G., and Matti, C. (2022). X-curve: a sense-making tool to foster collective narratives on system change (transitions hub series). DRIFT and EIT Climate-KIC Transitions Hub. Available at: https://drift.eur.nl/nl/publicaties/x-curve-a-sense-making-tool-to-foster-collective-narratives-on-system-change/

Steen, M. (2016). Reconsidering path creation in economic geography: aspects of agency, temporality and methods. Eur. Plan. Stud. 24, 1605–1622. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1204427

Tõnurist, P., and Hanson, A. (2020), “Anticipatory innovation governance: Shaping the future through proactive policy making”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 44. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Turnheim, B., Berkhout, F., Geels, F. W., Hof, A., McMeekin, A., Nykvist, B., et al. (2015). Evaluating sustainability transitions pathways: bridging analytical approaches to address governance challenges. Glob. Environ. Chang. 35, 239–253. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.08.010

Turnheim, B., and Nykvist, B. (2019). Opening up the feasibility of sustainability transitions pathways (STPs): representations, potentials, and conditions. Res. Policy 48, 775–788. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2018.12.002

UNEP and ISC (2024). Navigating new horizons: a global foresight report on planetary health and human wellbeing. Available at: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/45890

Vesnic Alujevic, L., Muench, S., and Stoermer, E. (2023). Reference foresight scenarios: scenarios on the global standing of the EU in 2040. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.