- 1Consuelo Foundation, Honolulu, HI, United States

- 2Department of Political Science, College of Social Sciences, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI, United States

- 3Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Management, College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI, United States

- 4Department of Economics, College of Social Sciences, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI, United States

- 5University of Hawai‘i Sea Grant College Program, Honolulu, HI, United States

- 6After Oceanic Built Environments Lab, Honolulu, HI, United States

This article examines the growth of Indigenous grassroots community groups across Hawaiʻi, whose efforts are pivotal to place-based climate change resilience and community well-being. Instead of focusing on specific ecosystem resilience actions, it highlights the people and places that make this movement of community organizations resilient, leveraging both social and cultural strengths to adapt to climate impacts. For many Indigenous peoples, climate change is not new; adaptation has already been integral to relationships between environment and culture. These changes require culturally responsive approaches, not short-term engineering solutions such as coastal hardening or stream channelization. A collaboration between a grassroots artist mapping initiative (‘ĀINAVIS) and a university’s community-based research project (‘ĀINA KUPU), this study utilizes a novel data index compiled using publicly available information to inform a series of in-depth student interviews with community groups across Hawai‘i whose mission, vision, and work are dedicated to caring for ‘āina. We find that these “ʻĀina Organizations” articulate climate resilience in multi-faceted and culturally grounded ways, maintaining reciprocal and mutual relationships with ʻāina, the Hawaiian term for land meaning “that which feeds.” Facing various challenges and needing different systems of support, our work maps the dynamic adaptability of ‘āina expressed through community networks of collaborative care with emphasis on the importance of intergenerational knowledge and genealogical connection to place shared and passed onto future generations. The article concludes by emphasizing the importance of working on ‘āina as an exercise of Indigenous sovereignty, expanding climate resilience with cultural practice and social justice as both outcome and process of climate change adaptation.

1 Introduction

Dear Reader, before you begin, we invite you to an Aloha Circle, a way to open a gathering in Hawai‘i. In an Aloha Circle, we introduce ourselves to the collective by acknowledging the lands that shape us and the genealogy of beloved ones that have made us who we are. As you imagine us standing together, dear Reader, we invite you to share three names: your name, the name of a place you love, and the name of one person—an ancestor, a family member, or a mentor, whom you bring with you today. In this circle, every name is valued equally, our names and the names of beloved people and of the land, with humility and gratitude. Imagine we are all together as the sun warms our faces, and a gentle wind blows. Can you feel how the circle grows larger with each name shared? In speaking our names out loud in the circle we acknowledge that we are accountable and belong to these people and places that we love, and who love us in return. We belong (Hoʻoulu ʻĀina).4

Now that we are acquainted, dear Reader, let us see the provisions we have for our journey together. This article serves as an ipu, a gourd, a vessel brimming with stories of beloved lands and waters carried by the communities that care for them. Like a sturdy gourd carrying life-giving waters, this article holds stories of growth, hardship, opportunity, and lessons learned. As we share from this ipu together, may we honor the wisdom of those who came before us and tread lightly upon the earth. As you continue on, remember that you are not alone, that you come with your names and all of the names spoken in the circle. Welcome home.

“Move like ‘āina (land), slow like mud, but with purpose like wai (water).” (Community Participant, November 9, 2022).

In ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language) the word ʻāina refers to “that which feeds” and includes people, land, sea, and sky. ʻĀina embodies the relationship with “the place that feeds your family, not only physically but spiritually, emotionally, and intellectually” (Vaughan, 2018, p.4; Andrade, 2008). Across the Hawaiian Islands, efforts are underway to restore relationships between people, ʻāina, and ancestral wisdom. In the act of restoring ʻāina, individuals and communities restore themselves, their self-determination, and well-being (Corntassel, 2012; Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua, 2013; Diver et al., 2024). Such holistic and pluralistic understanding of ʻāina restoration is tightly connected to a Native Hawaiian, henceforth Kānaka Maoli, concept of “ea.” Translated as “life,” “breath,” and “sovereignty,” in literature on Kānaka Maoli politics, ea. is critical because it “make[s] land primary over government, while not dismissing the importance of autonomous governing structures to a people’s health and well-being” (Goodyear-Kaʻōpua et al., 2014, p.3). ʻĀina restoration work has direct impacts on the well-being of the Kānaka Maoli nation, or the lāhui. Many Kānaka Maoli, locals (Hall, 2005; Okamura, 2014), and settler allies (Fujikane, 2016) are dedicated to reinvigorating care of ʻāina, along with Kānaka Maoli language and cultural practices rooted in ʻāina. In the face of climate change, this relationship and reinvigoration are especially vital.

Hawai‘i is an ecologically and culturally unique place on the planet where the diversity of communities mirrors the diversity of the landscape and its unique ecosystems (Vaughan and Vitousek, 2013; Winter et al., 2021). As the most isolated islands in the world, living in kinship with nature was critical to the survival and thriving of the population before colonization (Winter et al., 2021; Poepoe et al., 2007; Vaughan, 2018; Montgomery and Vaughan, 2020). Rapid change after European contact in 1778, and the illegal overthrow and annexation of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States in 1898, drastically altered the Native population and the physical environment of the archipelago (Connelly, 2022; Gonschor and Beamer, 2014). Today, Kānaka Maoli are an Indigenous people displaced in their own homelands due to the high cost of living, gentrification, and other factors (Vaughan, 2018). In spite of displacement and other challenging social determinants, Kānaka Maoli communities, their friends and allies are dedicated to maintaining places amidst rapid change.

In ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi, the word kīpuka describes “patches of forest that remain standing after a lava flow” (Vaughan, 2018). The word kīpuka is also used to refer to “places where Native Hawaiian culture [has] survived dynamic forces of political and economic change throughout the twentieth century” (McGregor, 2007). In many ways, the ʻĀina Organizations’ day-to-day physical labor on dedicated space reclaims a substantial land base of kīpuka aloha ʻāina (Peralto, 2018) and embodies practices of self-determination and sovereignty. This paper thus connects the restoration of the environment and political sovereignty to understand both the ecological and political potential of ʻĀina Organizations engaged in cultural and ecosystem restoration.

Indigenous lifeways, their ecological knowledge, and culture are foundational to work at the forefront of climate change resilience (Grossman and Parker, 2012; Baldy, 2013; Kenney and Phibbs, 2015; McMillen et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2020; Williams, 2021). Climate change is not new, and adapting to live in balance with place has always been a part of the culture of the Hawaiian Islands along with other archipelagos across the Pacific. Pacific Island communities are already being affected by climate change, with many communities facing flooding and sea-level rise (Gerhardt, 2020; Harangody et al., 2023). Lessons from communities living and adapting at the frontline of climate change can help to guide other communities worldwide (Raygorodetsky, 2017; Johnson and Wilkinson, 2020).

Situating people and places together and exploring their interrelationships becomes more vital in the face of climate change induced threats, because people and the land heal each other. In Hawai‘i, there is no ʻāina without kānaka (people). To commemorate Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea, or Hawaiʻi Sovereignty Restoration Day, in 1871, a Hawaiian leader named David Kahalemaile gave a speech about the importance of ea. “as something vital that we cannot live without,” (Kuwada, 2015) he said, “Ke ea o honua, he kanaka,” translated as “The ea of the earth is the person.” (Kahalemaile, 1871, quoted in Kuwada, 2015). That is, the earth cannot live without people. People and land are intertwined (Mahi, 2017). The stories shared in this research, illuminate the biocultural restoration of Indigenous places and people in Hawai‘i, while demonstrating the inherent mutuality between the two.

However, many discussions of sustainability and climate change are unable to consider the role of people in place. While in Kānaka Maoli culture, people and land are inextricably linked, and the role of land, is ʻāina, that which feeds, in the political vernacular and practice of modern-day Hawai‘i, as in many places impacted by settler colonialism (Pizzini, 2006; Gómez-Barris, 2017; Haas, 2022), land is a commodity or an extractable resource from which to derive profit (Vaughan, 2018). The detrimental effects of this perspective are abundantly evident in small island ecosystems like Hawai‘i, where land is so limited, and populations once sustained exclusively from local resources rely upon imported food (85–90%; Loke and Leung, 2013; Office of Planning, 2012; Aloha Challenge, n.d.) and material goods. Ancestral approaches which managed biocultural relationships and ensured relative perpetual sustainability provide guidance for modern practitioners. However, these traditional ways have long existed on the margins, unacknowledged by a society focused on ownership and transaction.

The collaborative efforts represented within this project center communities of practitioners protecting and perpetuating sustainable practices. Their work, which includes sharing community stories and technical support, amplifies the voices of those directly (and indirectly) mitigating climate change and addressing social determinants of health and well-being. Our research brings together community leaders, artists, University students and teachers, nonprofit and philanthropic staff, and cultural practitioners, all committed to the well-being and resilience of Hawaiʻi’s lands and people. This collaboration combines data with narrative to draw a comprehensive picture that reaches back into history and forward into the future, highlighting the critical nature of this movement for Hawai‘i and the world.

This article contributes to efforts at restoring cultural practice and community resilience. It explores and uplifts the deep connection between land and people, and how the mutual relationship between the two contributes to biocultural sustainability at the crossroads of ancient wisdom, changing ecologies, and the perils and potential of changing climate.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Overview

‘ĀINAVIS is a place-based community engagement approach centering artist-driven mapping concepts that aim to highlight how peoples, place, and time are connected. It shows how problems originate beyond the bounds of the history and space where Indigenous people are working to solve them, and acknowledges the regional scale of not only challenges, but also solutions. This concept emphasizes the importance of well-being of ‘āina across the Hawaiian Islands amid contemporary issues like climate resilience. Short for ‘āina vision, ‘ĀINAVIS was created by Dr. Sean Connelly and Dawn Mahi to engage conversations that integrate existing and novel datasets using Geographic Information Systems (GIS), 3D architectural modeling software, and Google Earth to provide comprehensive views of Hawai‘i’s cultural, ecological, social, and political landscapes (Connelly, 2010).

In 2022, ‘ĀINAVIS collaborated with an academic research initiative at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa called ‘ĀINA KUPU, created and led by Dr. Mehana Vaughan and students in the Natural Resources and Environmental Management Department (NREM) to advance community-based research and hands-on volunteerism focused around ‘āina within the broader context of a dataset provided produced by ʻĀINAVIS, that the NREM students also helped to refine. The synergy that emerged between the arts and humanities focus of ʻĀINAVIS, and the academic and science-based focus of ‘ĀINA KUPU supported a holistic understanding of the significant role that ‘āina plays within the context of climate change resilience emerging across the Hawai‘i Islands today.

2.2 ʻĀINAVIS Index

A key component of ʻĀINAVIS is the ʻĀINAVIS Index, a dynamic dataset listing nonprofit groups across Hawai‘i whose mission, vision, and work are dedicated to ‘āina. Created by over a dozen contributors, the Index enhances the visibility and understanding of community groups in Hawaiʻi doing work around ‘āina, referred to in our research as ʻĀina Organizations.1 The ʻĀINAVIS Index archives publicly available information about organizations, such as founding year, location, and program type to address existing gaps in other publicly available datasets that do not contain such information. The intent is to better portray the vital work of these groups and organizations across Hawaiʻi dedicated to ʻāina. The index is not an active directory but an illustrative tool to explore the relationships between people, place, and ‘āina, aiming to enhance climate resilience, cultural resurgence, and community well-being through the integration of geospatial data and community insights.

2.3 ʻĀINAVIS data collection and charrettes

The ʻĀINAVIS approach employs a “data to dialogue” methodology, where artists, cultural leaders, and practitioners gather together into groups called “charrettes” and explore spatialized GIS datasets while sharing stories, knowledge, and connections to various locations in Hawai‘i, guided by themes that center the concept and practice of ‘āina. These charrettes provide a culturally responsive platform for exploring geospatial data with the added information of shared personal experiences that connect information about ‘āina with ‘āina experiences. Stories range from personal and ancestral connections, such as the importance of protecting burials and sacred sites, to cultural issues like ecosystems restoration, to political and environmental issues like climate change. ‘ĀINAVIS therefore maps the connections between culture and climate change in Hawai‘i. Examples of stories shared during charrettes include:

• A community participant shares a story of a small beach under restoration to protect native limu (seaweed) that has experienced decline, where the participant shares primary knowledge grounded in a genealogical connection to that place.

• A longtime caretaker of a cultural site located in a valley with a history of military training activity learns of a potential hazardous waste site on the land that is still largely unknown to the public.

• A young woman reconnects with her family’s kuleana (responsibility) as she recounts an encounter with a special fish of an ancestral place.

2.4 Origins and development

‘ĀINAVIS originated from the personal and professional experiences of its founders, who sought to understand how communities across Hawai‘i restore, access, and promote ‘āina as a source of healing and restoration, while also understanding what either supports or threatens this for individuals, families and communities. In 2016, a local project explored enablers and inhibitors to quality ‘āina-based education across Hawai‘i resulting in a systems map that was robust however without geographic references. ‘ĀINAVIS was created to situate these stories and themes in place, using mapping to leverage dialog and technology.

2.5 Cross-institutional collaboration

Since 2019 ‘ĀINAVIS has evolved as an ad hoc effort initiated in collaboration between After Oceanic Build Environments Lab and Consuelo Foundation, in conversation with other community partners committed to transform the wellbeing of Hawai‘i by enhancing understanding of the importance of the commitment to ‘āina. Learning from grassroots community efforts and Indigenous knowledge has also influenced higher education learning in Hawaiʻi. Between 2013 and 2015, Kānaka Maoli scholars were hired at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa to integrate scholarship and community engagement in promotion of the concept Aloha ‘Āina, meaning “love of the land.” Over 500 students have participated in project-based courses supporting community efforts to care for lands and waters.

2.6 ‘ĀINA KUPU initiative

‘ĀINA KUPU brought ʻĀINAVIS into the university setting, combining direct, hands-on volunteerism of students empowered with the broader mapping perspective provided by the ‘ĀINAVIS Index. Over 1 year, 35 NREM graduate students2 from various departments including Political Science, Urban Studies, and Hawaiian Studies volunteered with 12 ʻĀina Organizations on Oʻahu included in the ‘ĀINAVIS Index. Students helped to identify partner organizations based on the organizationsʻ needs, interest in collaborating, and sometimes on existing relationships which made it possible for individual students to lead the work. Then, groups of 3–4 students, worked with their partner organizations over the course of the semester, engaging in “learning by doing” through hana (work) dedicated to caring for ‘āina. Student groups supported their partner organizations in various hands-on tasks, such as harvesting vegetables, planting kalo (taro), hosting educational groups and conducting water sampling. Students also “learned by listening,” conducting interviews with founders and staff at their partner ‘Āina Organizations toward the end of their semesters volunteering. While the people we talk to in social science research are usually referred to as interviewees, we want to emphasize that they are partners who our team members build intentional relationships with. The stories and knowledge offered in this paper would not exist if they had not chosen to host and teach our students, collaborate and share learning side by side. The 12 partner organizations we collaborated with in this research are: ʻEwa Limu Project, Hoʻoulu ʻĀina at KKV, Kauluakalana, Kuhiawaho, Livable Hawaiʻi Kai Hui, Mālama Loko Ea, Mālama Mākua, Makaʻalamihi Gardens, Nā Wai ʻEkolu, Protect & Preserve Hawaiʻi, Waiakeakua, Waialeʻe Lako Pono.

2.7 ‘ĀINAVIS Index expansion and verification with ‘ĀINA KUPU

Students also undertook the task of refining, expanding and confirming the ʻĀINAVIS Index. They cross-checked publicly available sources, including websites, social media platforms, and books to confirm accuracy of the dataset. Students also added additional organizations based on network lists shared by community partners. The index was then filtered using an internal rubric developed by the ‘ĀINAVIS and ‘ĀINA KUPU research teams.3 The process further guided student dialogues exploring the role ‘āina plays in securing community well-being, and was informed by the students’ volunteering and interviews with their partner organizations.In total, students interviewed 12 ‘Āina Organizations and conducted interviews with 30 individuals across the island of Oʻahu. Interviews were semi-structured and focused on understanding the origin, visions, challenges, and sources of support for each organization. Some of these flexible “talk story” sessions were with individuals, while others occurred in groups. The questions, co-developed with partner organizations, included:

• When and how did your hui (group) begin?

• What is your future vision?

• What challenges do you encounter?

• What sources of support sustain your organization?

• Which ‘āina hui (group) do you see as your older and younger siblings and successors?

2.8 Analysis and synthesis, ‘ĀINA KUPU x ‘ĀINAVIS

All student interviews were transcribed, shared back with partners and analyzed for common themes presented below. From January to March of 2023, a subset of students analyzed interview transcripts, highlighting quotes representing the most substantive parts of an ʻāina organization’s experience shared, that were then, consolidated to identify descriptive themes that summarize the overall understanding of the experience of ‘Āina Organizations, shared in the following results which are also bolstered by ‘ĀINAVIS data charrettes held from 2020 to 2024.

3 Results

The research resulting from the ‘ĀINAVIS Index and ‘ĀINA KUPU Interviews emphasizes the significant role of ʻāina in addressing place-based climate change through cultural and community-based approaches. Findings highlight the significance of ʻĀina Organizations, who care for a wide range of historic places such as loʻi kalo (wetland taro), loko ʻia (fishponds), and māla (gardens), found across various ecosystems from montane forests to coastal areas, to entire watersheds. By addressing these findings, this research contributes to a deeper understanding of how ʻĀina Organizations can foster resilience and sustainability in the face of climate change.

3.1 Summary of findings

We summarize the results of the ‘ĀINAVIS Index and ‘ĀINA KUPU Interviews into the following findings:

1. ‘Āina Organizations continue to grow each decade

2. ʻĀina Organizations are engaged in multifaceted and culturally grounded efforts for climate resilience

3. ʻĀina nourishes their work

4. There is no ʻĀina without people

5. ʻĀina Organizations face generational challenges

6. ʻĀina Organizations are sustained by supportive genealogies and community networks of collaborative care

7. ʻĀina education nurtures the next generation of leaders

3.2 ‘Āina Organizations continue to grow each decade

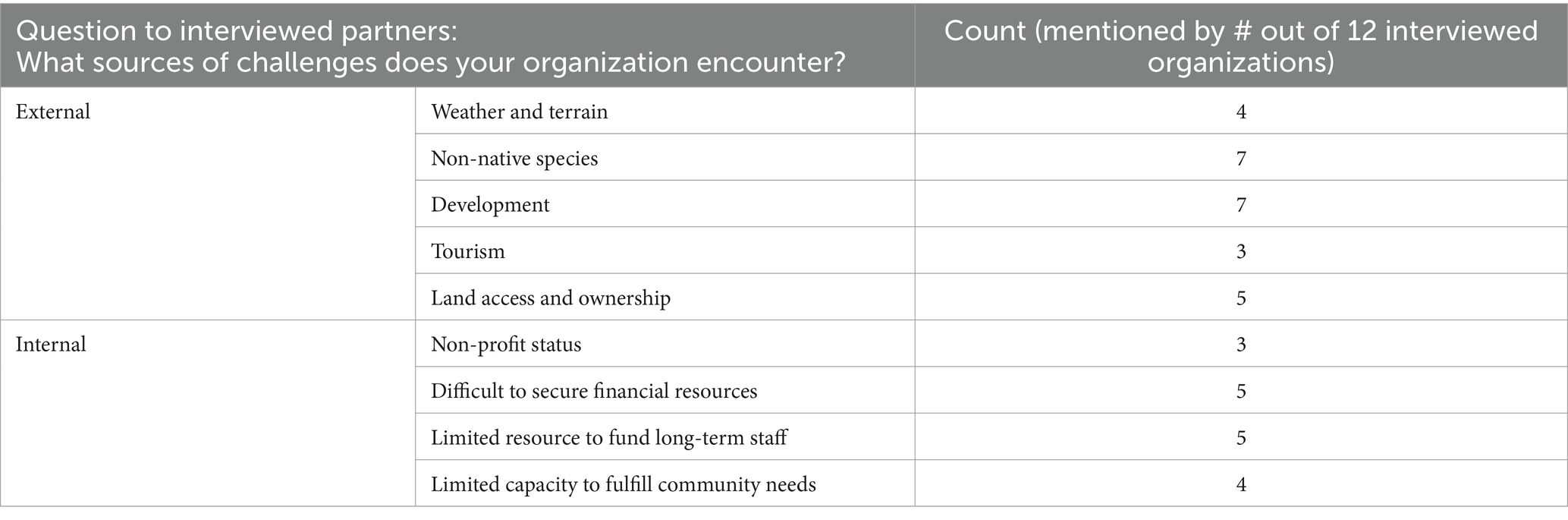

The analysis of the founding year data for ‘Āina Organizations reveals a significant and continuous growth trend over time (Figure 1). With founding years ranging from 1950 to 2022, the index highlights the enduring commitment to community and environmental stewardship explored in our results. Notably, while there were less than 90 organizations up to 1990, another 90 organizations have been founded each decade since, from 1990 to 2000, 2000 to 2010, and 2010 to 2020 (Figure 2). The most common founding year since 2000 is 2014, while the most common founding year since 1950 is 1995. These mark a period when the number of new organizations surged, reflecting broader cultural shifts that encouraged the establishment of many new entities, such as increased popularity in the Hawaiian Sovereignty movement following the 1993 centennial of the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and the founding of the Protect Mauna Kea movement in 2014. The accelerated increase of the founding of ‘Āina Organizations over the past 50 years indicates a growing movement and heightened awareness of the role of culture in addressing community and environmental needs. The trend of continual growth underscores the importance of these organizations and their critical contributions to society.

Figure 1. ʻĀina Organization Index (1950–2022) across Hawaiʻi. This figure depicts the spatial distribution of ʻĀina Organizations active between 1950 and 2022, highlighting the resurgence of land stewardship across the Hawaiian Islands. Each red triangle marks the location of an organization dedicated to ʻāina, reflecting the growing network of community efforts toward environmental and cultural restoration (Courtesy of After Oceanic Built Environments Lab).

Figure 2. ʻĀINAVIS Index showing the growth of ʻĀina Organizations across the Hawaiian Islands (1950–2022). This figure displays the number of new ʻĀina Organizations founded each year, the average age of these organizations, their active/inactive status (with 96% still active), and the distribution by county, including Kauaʻi, Oʻahu, Maui, and Hawaiʻi Island. The data indicates a notable increase in the establishment of ʻĀina Organizations over the past few decades, particularly in Honolulu County (Courtesy of After Oceanic Built Environments Lab).

3.3 ʻĀina involves multifaceted and culturally grounded efforts

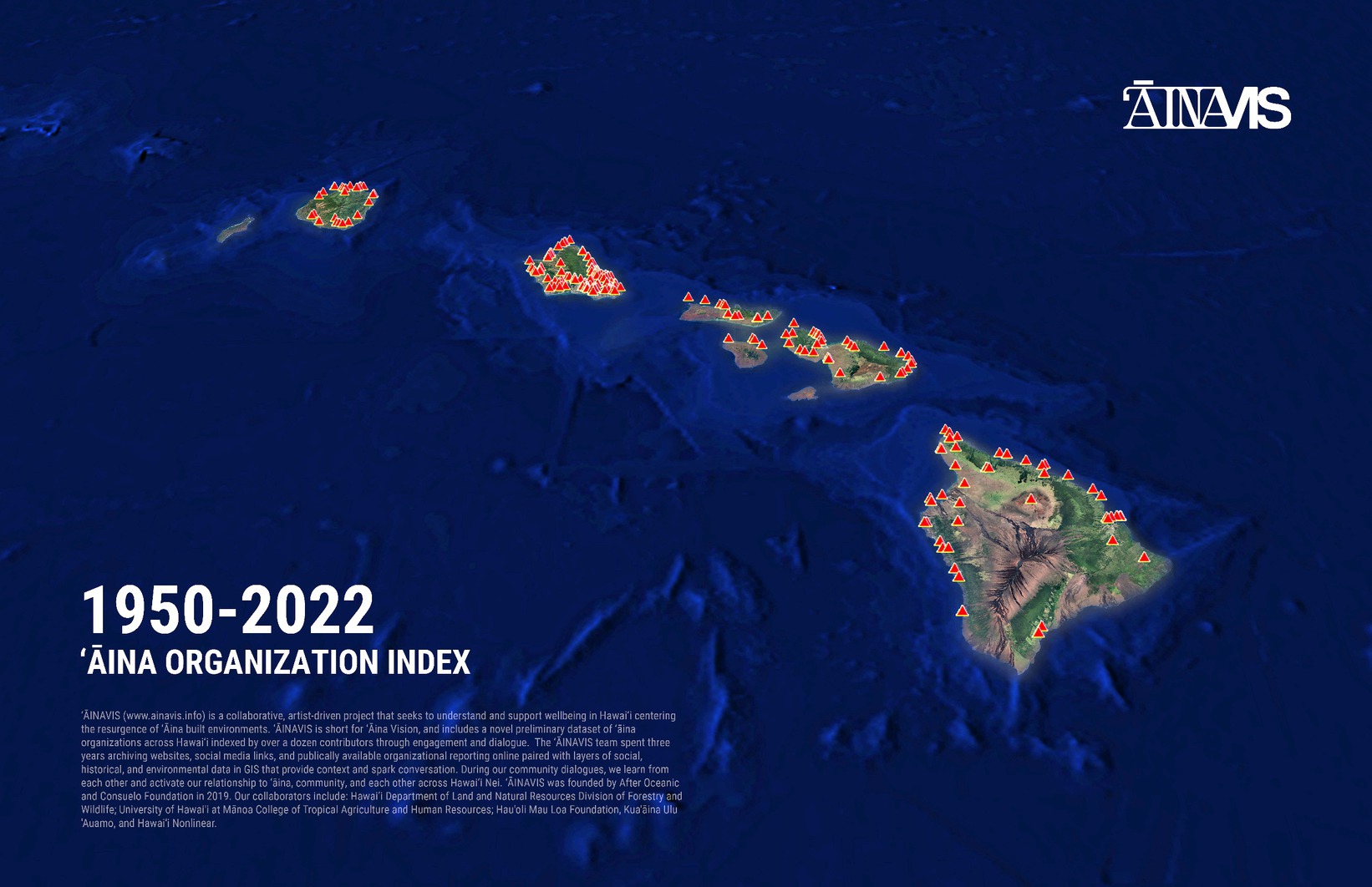

The multifaceted nature of ‘āina work is evident through the words most frequently mentioned in the mission and vision statements of ʻĀina Organizations in Hawaiʻi: “community,” “Hawaiian,” “cultural,” “native,” and “education” (Figure 3). These highlight the centrality of Indigenous culture to resource management and environmental protection, and the need to protect ʻāina propelled by the understanding that in Hawai‘i, what threatens the land also threatens the community. The ‘ĀINAVIS Index also showcases the diversity of work by ‘Āina Organizations. Many organizations work across multiple identified categories: education (81%), ecosystems restoration (80%), cultural heritage conservation (45%), advocacy (41%), food sovereignty (34%), social justice (32%), sovereignty (23%), Indigenous science (16%), health (9%), arts (6%), repatriation (3%), and demilitarization (2%).

Figure 3. Word cloud created using mission and vision statements from ʻĀina Organizations across Hawaiʻi. This visualization was generated by analyzing the key themes and terms that recur in the mission and vision statements of ʻĀina Organizations, emphasizing the centrality of “community,” “Hawaiian,” “cultural,” and “natural resources.” The analysis was conducted by students in NREM 620 (Fall 2022) at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa (Courtesy of University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa NREM 620).

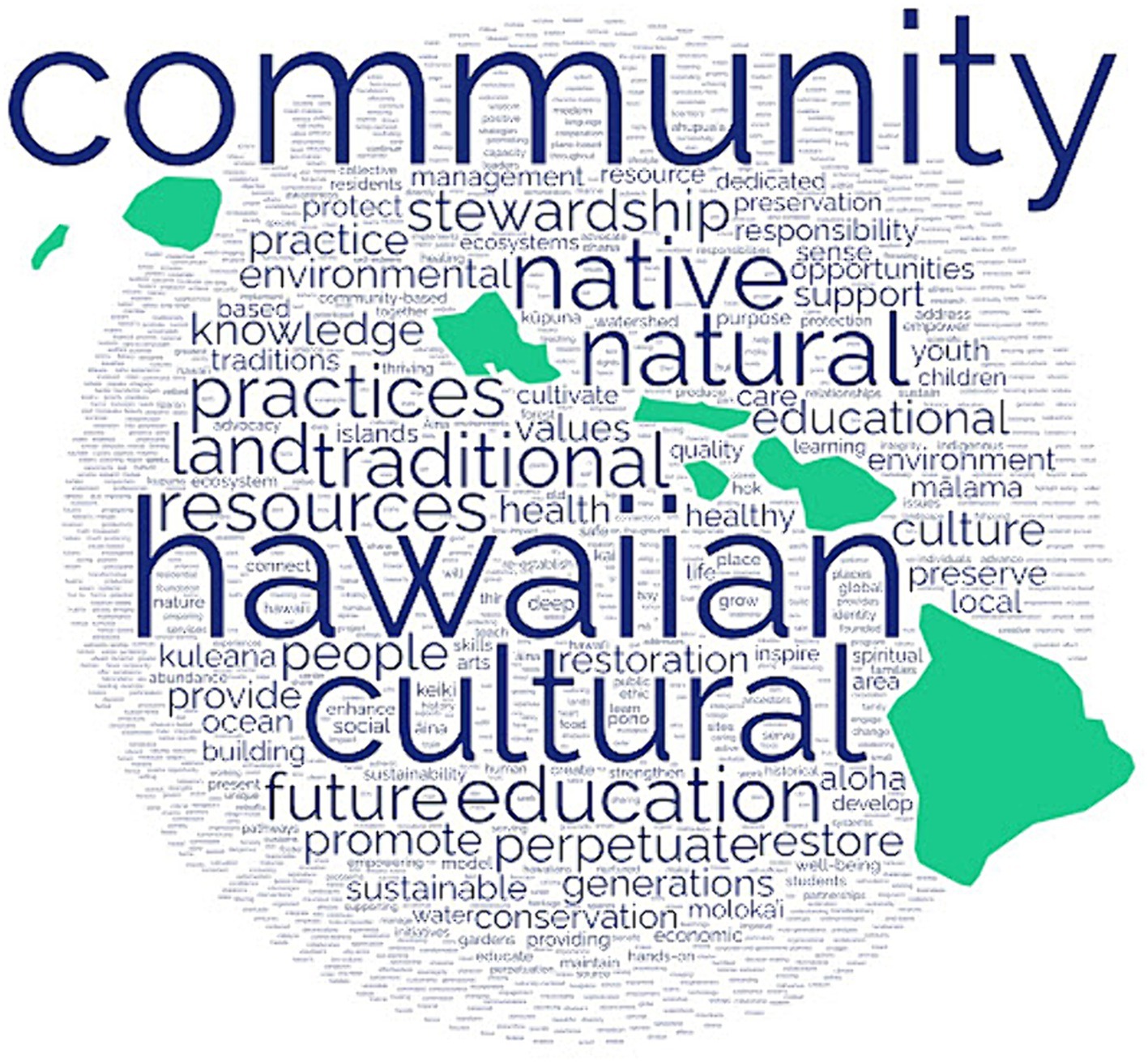

Though few groups explicitly refer to climate change in their vision and mission statements, nearly every organization interviewed described multiple linked ways their work addresses climate resilience. Examples shared in interviews include restoring historic wetland loʻi kalo (taro field) systems that filter, capture, and disperse floodwaters; enhancing coral reef health as ocean temperatures warm by managing and even planting macroalgae; rebuilding fish pond walls to buffer coastlines against sea-level rise; and creating community gardens to provide locally sourced food, reducing fossil fuel usage to withstand shocks in global food supply changes. This level of diversity highlighted in the interviews resonates with the different types of resources, ecosystems, and community spaces tended by ‘Āina Organizations in the ‘ĀINAVIS Index (Figure 4). Close to one-third of organizations have multiple sites and quite a few organizations take care of more than one type of resources. We find that groups also see their work as interconnected across ecosystems; for instance, the restoration of coastal seaweed depends on the restoration of freshwater flows from springs and upland forests. This interconnection is expressed in the cultural saying “from ma uka to ma kai,” “from mountain to ocean.”

Figure 4. ʻĀina Index by site characteristics. This figure provides an overview of the geographic and physical features of ʻĀina stewardship sites across Hawaiʻi, categorized into “On-Site” locations such as kalo (taro) fields, loko iʻa (fishponds), gardens, sacred sites, and forests, and “Off-Site” locations like community centers and mailing addresses. The figure highlights the diversity of stewardship areas, with 60% of the sites being “On-Site” and 40% being “Off-Site,” as well as whether sites represent single or multiple stewardship locations (Courtesy of After Oceanic Built Environments Lab).

One notable example of the multifaceted and holistic nature of work for climate resilience comes from the ‘Āina Organization Kauluakalana. Though their group is located in Kailua on the island of O‘ahu, one of the highest income and most gentrified towns in Hawai‘i, Kauluakalana founders and staff we interviewed expressed dedication to restoring a vision of their place for Native people. They describe not beachfront mansions, tourists and foreign residents, but abundance, community accountability, and thriving Indigenous heritage. At the storied site Ulupō, one of Hawaiʻiʻs largest heiau or temple sites, Kauluakalana works to restore productive loʻi (taro patches) adjacent to a flowing spring. They also work to restore Kawainui Fishpond, the second largest fishpond in Hawai‘i, often classified as a wetland. Kauluakalana engages the community in their work and programs through sharing the guiding ancestral mo‘olelo (stories) of these places, which emphasize the important role that humans play in mutual relationship with the environment, and what happens when they stray from their role. This counters the Western concept of humans as separate from nature, where a wetland is not meant to be touched by humans but conserved. Another central program at Kauluakalana teaches ʻohana (families) to create a stone pounder and wooden board, to pound kalo, (taro, ancestor of Hawaiian people), into poi and practice together, thus ensuring families have both tools and knowledge to feed themselves from the restored ecosystem in community. Kauluakalana’s work demonstrates that community coupled with cultural practice can help to mitigate climate change and foster biocultural resilience. Their ancestral moʻolelo remind us that Kailua is a deeply Hawaiian place, and help to demystify the functions of a once storied, interconnected, and sustainable ecosystem through restored, collective practice within ʻohana and community.

3.4 ‘Āina nourishes the work

For the communities we worked with and interviewed, ecosystem restoration and climate resilience is guided by the land itself. This guidance occurs through careful observation of ecosystems and how they are changing, in order to tailor responses, but also through ceremony, prayer and the many ways that less tangible responses from ʻāina reinforce and bless caretaking. For most of the organizations in our study, ʻāina is foundational, providing physical space, and cross-generational connection that both calls people to action, and provides a source of ongoing support. Interviewed partners from six of twelve organizations shared that ʻāina provides favorable conditions for growth and harvesting, as well as direct communication with its stewards, that ‘āina responds to both physical, spiritual needs and prayers. For example, at Hoʻoulu ʻĀina, the staff expressed they feel supported by the elements of rain and wind, which are crucial for their work: “We get rain here pretty [much] daily. The work would be so different here without the rain... Mahalo (thank you) to the rain. And the wind that helps us dry things here. We are supported by everything.” The work on ʻāina generates positive reverent experiences, keeping stewards engaged and hopeful.

Connection to ʻāina and sense of fulfillment from working to care for ʻāina, extends beyond native Hawaiians to the many core members and founders of ʻĀina Organizations. Three non-Hawaiian staff and volunteers we interviewed expressed how working with ʻāina changed their sense of responsibility to place. As expressed in one interview with a founder of the organization Protect and Preserve Hawai‘i: “...it was just about the feeling of giving back and doing something good for the community, but then as I made connections and started to learn about the plants, it turned into something more than that…I’m not Native Hawaiian but I’m living here, I’m taking up space and resources, and this is one way that I can give back.” Overall, ʻāina work is rewarding and transformative, inspiring both Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians to connect with and care for the land.

3.5 No ʻāina without people

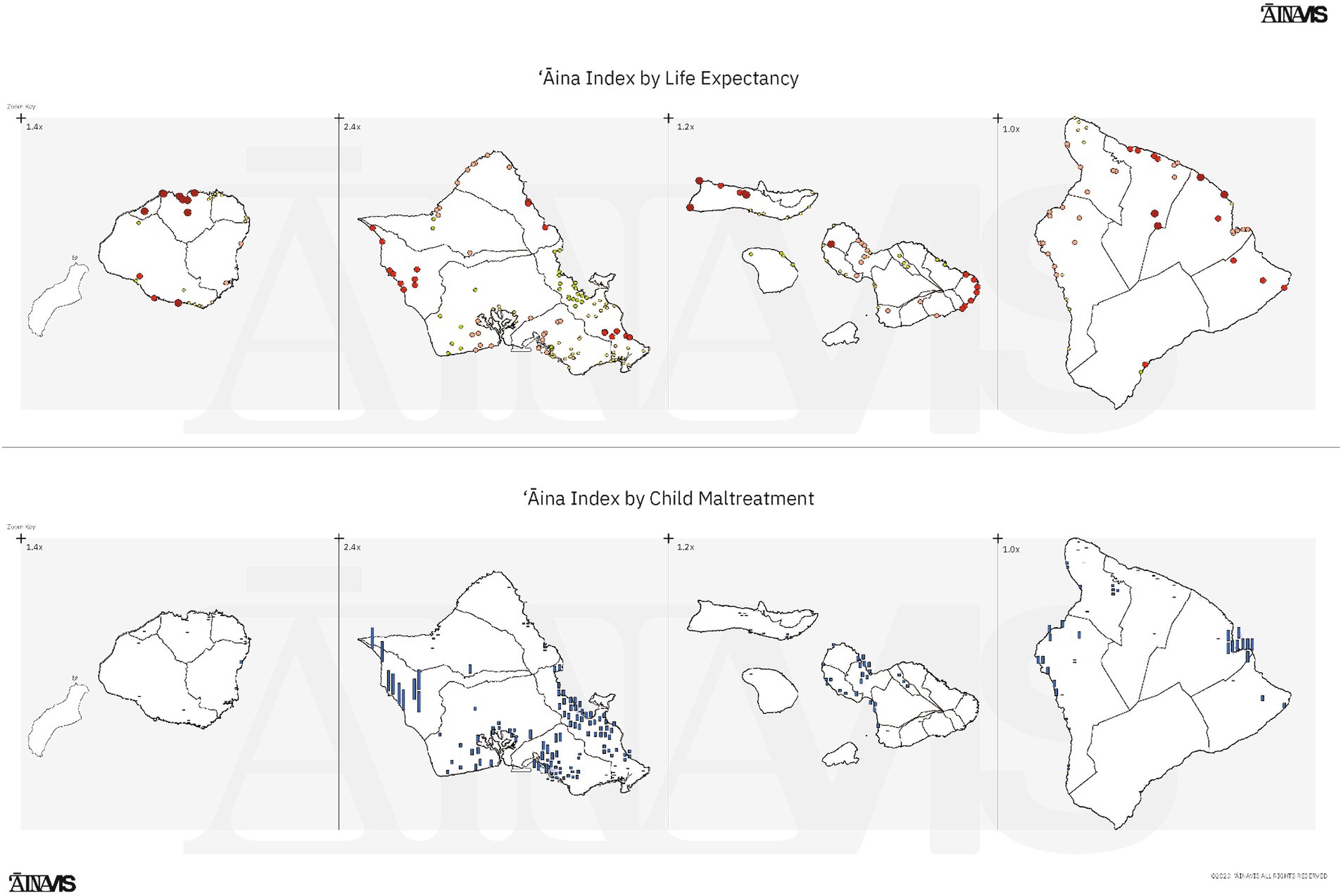

Interviewed partners emphasized the need to protect ʻāina, understanding that the health of the land directly impacts community health. This interconnectedness is evident in a focus on health and food sovereignty expressed across interviews. For instance, Hoʻoulu ʻĀina Nature Preserve, a program of Kōkua Kalihi Valley Comprehensive Family Services (KKV), is part of a federally qualified community health center located in the most diverse and densely populated neighborhood in urban Honolulu, where not only Kānaka Maoli, but immigrants from across the Pacific––such as Micronesians, Samoans, Filipinos call home. As our partners expressed, “the breath of the land is the life of the people.” Volunteers help to restore 99 acres of forest by removing invasive species and engaging in food cultivation, traditional plant medicine and healing, and more, all while building cross-cultural relationships. Hoʻoulu ʻĀina works to restore the watershed, all while engaging in education, such as teaching youth to repurpose invasive trees like albizia into canoes that they carve and sail themselves. An outgrowth of this successful program includes a garden in public housing and a food hub and mobile market to provide fresh, local, and traditional food across the community. Hoʻoulu ʻĀina/KKV observed that participants feel healthier on ‘āina than at the clinic, especially for those coming from crowded public housing and whose home islands are deeply impacted by U.S. militarization and climate change. Similar sentiments are echoed by Waialeʻe Lako Pono, who emphasized using the land to cultivate taro for healthier food sources for schools and families. The map figure below (Figure 5) illustrates the potential of more in-depth analysis regarding whether ‘Āina Organizations’ distribution have direct impact on community health, using publicly available indexes such as life expectancy and child maltreatment.

Figure 5. ʻĀina Index by life expectancy (top) and ʻĀina Index by child maltreatment (bottom). The top panel shows the distribution of ʻĀina organizations overlaid on areas with varying life expectancy across Hawaiʻi. Red dots represent regions with lower life expectancy, while green dots signify areas with higher life expectancy. The bottom panel illustrates the ʻĀina Organizations in relation to child maltreatment reports, where larger bars indicate more reporting of maltreatment. It is important to note that higher reporting does not necessarily equate to more incidents of abuse but could suggest more successful outreach and prevention efforts in those areas (Courtesy of After Oceanic Built Environments Lab).

Community well-being relies on ʻāina, and ʻāina’s well-being depends on dedicated stewards, particularly kūpuna (elders). Interviewed partners from nine of twelve groups emphasized the invaluable role of kūpuna in founding or guiding their work. Kūpuna teach valuable skills and share knowledge and stories about place, countering dominant narratives and providing a tangible picture of what areas were and can be. Founding members often draw strength from kūpuna knowledge and dedication, feeling a sense of accountability and support in their work. Even without guiding elders, generational relationships with place remain crucial. Where elders are not part of an organization, founders were often inspired by kūpuna within their own families, and also often bring their entire family, across generations to the work. Families connected to a place, perpetuate ancestral wisdom and maintain the ongoing pīlina (relationship) of kānaka (people) with ʻāina amidst colonial displacement. These relationships can also be passed up from younger generations. For example, one family transformed their home into a community garden during COVID-19 to honor their son’s vision and love of Hawaiian crops. One of the founders notes: “When [our son] passed…. one way we managed our grief was to carry on his vision... He did not have a chance to really get that far into it. But he shared his vision. And we have expanded on it.” This demonstrates how generational dedication to a place can continue to thrive.

Access to land is essential for sustaining connections to ʻāina, yet our partners expressed that access is continually threatened by development, urbanization, tourism, and military presence. Some organizations noted they were birthed when community members observed neglected or threatened ʻāina. For instance, Mālama Loko Ea Foundation located in Hale‘iwa on O ‘ahu, formed in response to a local school’s call to restore a fallow fishpond. The founders of Mālama Mākua were active when the self-organized villages at Mākua Beach, Waiʻanae, faced threats of eviction in the 1990s. The manufactured “crisis of homelessness” is contrasted with the Mākua Valley fenced off by the U.S. Army for training that burns and bombs ‘āina (Cruz et al., 2022; Mālama Mākua, n.d.). Fighting for peace and community access to the valley against military occupation, Mālama Mākua now facilitates bi-monthly cultural access and hosts ceremonies at sacred sites in Mākua Valley, which has not had life fire training since 2004. Multiple groups we partnered with emerged in response to threats which galvanized community and drove urgent responses that have since generated enduring work.

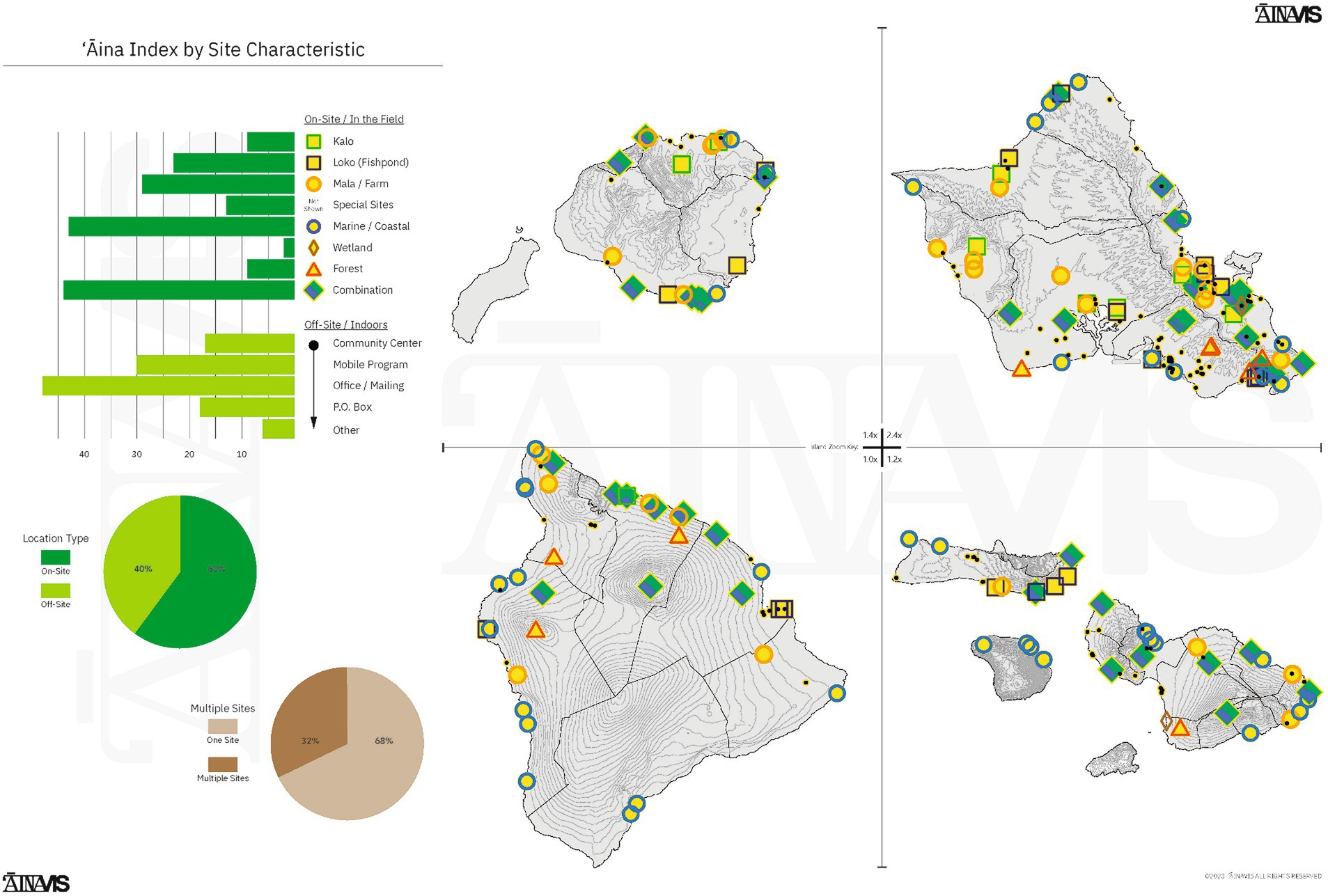

3.6 ʻĀina Organizations face generational challenges

As in other settings, the work of the groups described in this study, was neither linear, nor premeditated. This work is often described as a calling, with people feeling led to it, and we saw multiple ways that the work changed and evolved over time. As a result, ʻĀina Organizations experience seasons and cycles of change, facing numerous challenges to their sustainability over time (Table 1). Established organizations, dating back over a decade, face different challenges from newer organizations. While emerging organizations struggle with funding due to the lack of a track record, established ones need to focus on training new leaders. As a kūpuna (elder) member of the ‘Ewa Limu Project, a volunteer group that aims to restore and educate people about limu (seaweeds) in Hawaiʻi, expressed, “...the challenge for us is we are all getting old. This is basic. We are all getting to death… We’re at a place like in our lives that, you know, time is not our friend, so we need to do everything we can now to train the next generation if they are interested.”

External challenges include conflicts with market and tourist-based economies, degraded ecosystems, climate change, and the encroachment of non-native species. Partners frequently mentioned fluctuating weather patterns and rugged terrain. Social and political challenges, such as development, tourism, and limited land access, also directly impact ʻāina and the community. A community leader and student mentor from Waiakeakua, a community group taking care of the Waiakeakua Forest in Mānoa and planting food to feed the houseless, noted that understanding these changing natural cycles requires time and intimate relationships with the land.

Internal challenges encompass lack of structure, nonprofit funding, and personnel issues. Managing nonprofits, securing financial resources, and balancing community needs are difficult with limited time and energy. Funders often hesitate to support new organizations without proof of effective financial management, as highlighted by Livable Hawaiʻi Kai Hui, a community group protecting sites against development in East Honolulu. As organizations mature, the challenge shifts to sustaining funding, and finding time to pause, reflect and plan, ensuring their work remains purposeful. These pauses help prevent their efforts from becoming mere tasks and maintain their sense of kuleana (responsibility). Despite these challenges, ʻĀina Organizations continue to flourish, adapting and persisting through cycles and seasons of change.

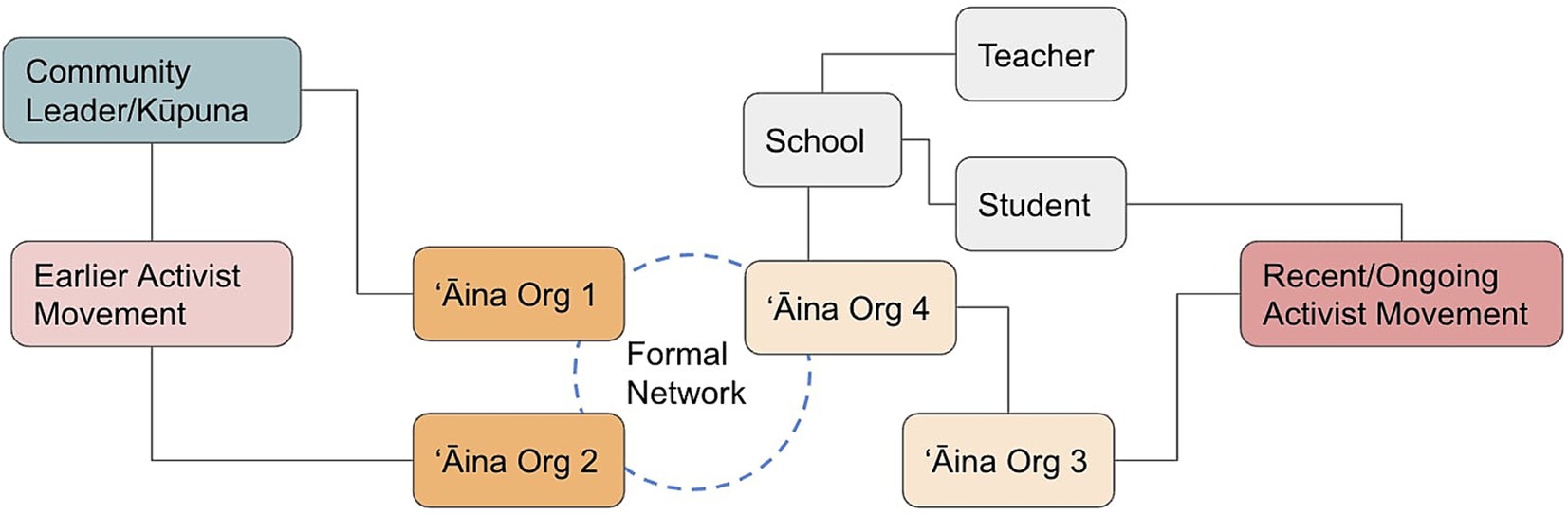

3.7 ʻĀina Organizations are sustained by supportive genealogies and community networks of collaborative care

Genealogies of practice and peer networks sustain ʻĀina Organizations and often stem from social movements. These movements involve many actors, including individuals, kūpuna, groups, state entities, and other non-profits. Organizations share resources, knowledge, and skills with a shared commitment to support each other. Parent and umbrella organizations lessen administrative burdens through fiscal sponsorship, offering financial management, grant writing, shared facilities, policy and advocacy support, and more. Formal networks unite groups, providing platforms for sharing experiences and fostering unity across the islands. Effective networks emerge spontaneously, often founded by practitioners gathering around shared practices (such as rock wall building, and fish pond restoration), experiences and knowledge.

In keeping with the concept of genealogy, many of the partners we talked to, emphasized the central role of kūpuna or elders in founding and nurturing ʻĀīna Organizations. Over half the groups we worked with, were founded by elders, many of whom remain involved. The presence of these founding kūpuna, helped partners we talked to, to feel accountable and supported, drawing strength from kūpuna’s knowledge and dedication. Kūpuna share crucial long term knowledge and cross-generational stories of place, also supported by sources like moʻolelo (stories) and mele (songs) within Hawaiian language newspapers and online databases. Some kūpuna are directly responsible for multiple organizations, while others trained or mentored cohorts of leaders who branched off and created their own peer organizations across Hawai‘i.

Some partners directly traced how one organization’s work inspired the establishment of another organization, referring to these groups as “elder and younger siblings.” Nearly half of the partner organizations we work with, said they emerged from or are supported by parent umbrella organizations. Kauluakalana provides an interesting example of a younger organization called to steward important sites which were taken care of by more established organizations since the 1970s. Established in 2019, Kauluakalana thus joins the genealogy of rich stories and struggles of multiple kūpuna champions and community stewards over generations (Kauluakalana, n.d.). In some cases, ‘Āina Organizations were fiscally or formally sponsored, or evolved from the phasing out of another organization. In others, they simply learned from earlier groups and efforts in the same community. Ho‘oulu ʻĀina, for example, as a program under KKV, can lean on a commitment to advance community health that started in 1972, providing Hoʻoulu ʻĀina with foundational capacity such as HR and grant writing, which many ‘Āina Organizations lack. Protect and Preserve Hawaiʻi, a young group who uses social media to mobilize hundreds of volunteers for an average work day, discussed building connections between other groups and volunteers as one of their future visions. They mobilize volunteers, not just for their own work days, but for other less social media savvy organizations as well. Elder siblings or parents, help younger groups to get started, while younger siblings, contribute new ideas, energy, and labor to their elder organizations whenever needed. These are informal genealogies of support.

Formal networks that unite groups, often established by entities like non-profits, foundation funders, or schools, are also important. Kuaʻāina Ulu ʻAuamo (KUA) was established by a peer group of ‘Āina Organizations that wanted to create a backbone organization to provide support to the movement. KUA acts as a convener, technical service provider, fundraiser, and advocate for its members. Participants include community groups like the ʻEwa Limu Project, which is a founding member of KUA’s Limu Hui, connecting limu(seaweed) practitioners across the islands. Partners highlighted networks of (peer) organizations as key sources of support. More than half said they were supported by grassroots, community-based, or, sometimes, institutional “formal” networks.

Organizations form networks or coalitions when they care for similar resources, reside in the same region, or have similar programming to share experiences and knowledge. Sharing, generosity, and collectivity are key to maintaining these dynamic network relationships. Some mentioned it can feel lonely doing ‘āina work when rewards are not often immediate, and impacts can take decades to see. However, understanding one’s organization and work as part of a collective movement, can be uplifting and inspiring.

Viewing ʻĀina Organizations as part of a larger family, and as elder and younger siblings, often reveals dynamics of intergenerational support and knowledge transfer, capturing the passage of wisdom, skills, and stories across groups and generations. Diverse ʻĀina Organizations inspire and support each other, reducing challenges of isolation through exchange of grassroots resources and experiences. Collective commitment strengthens networks as groups envision a shared future for Hawaiʻi. Genealogies and networks of many groups across Hawaiʻi grow into larger ʻāina movements.

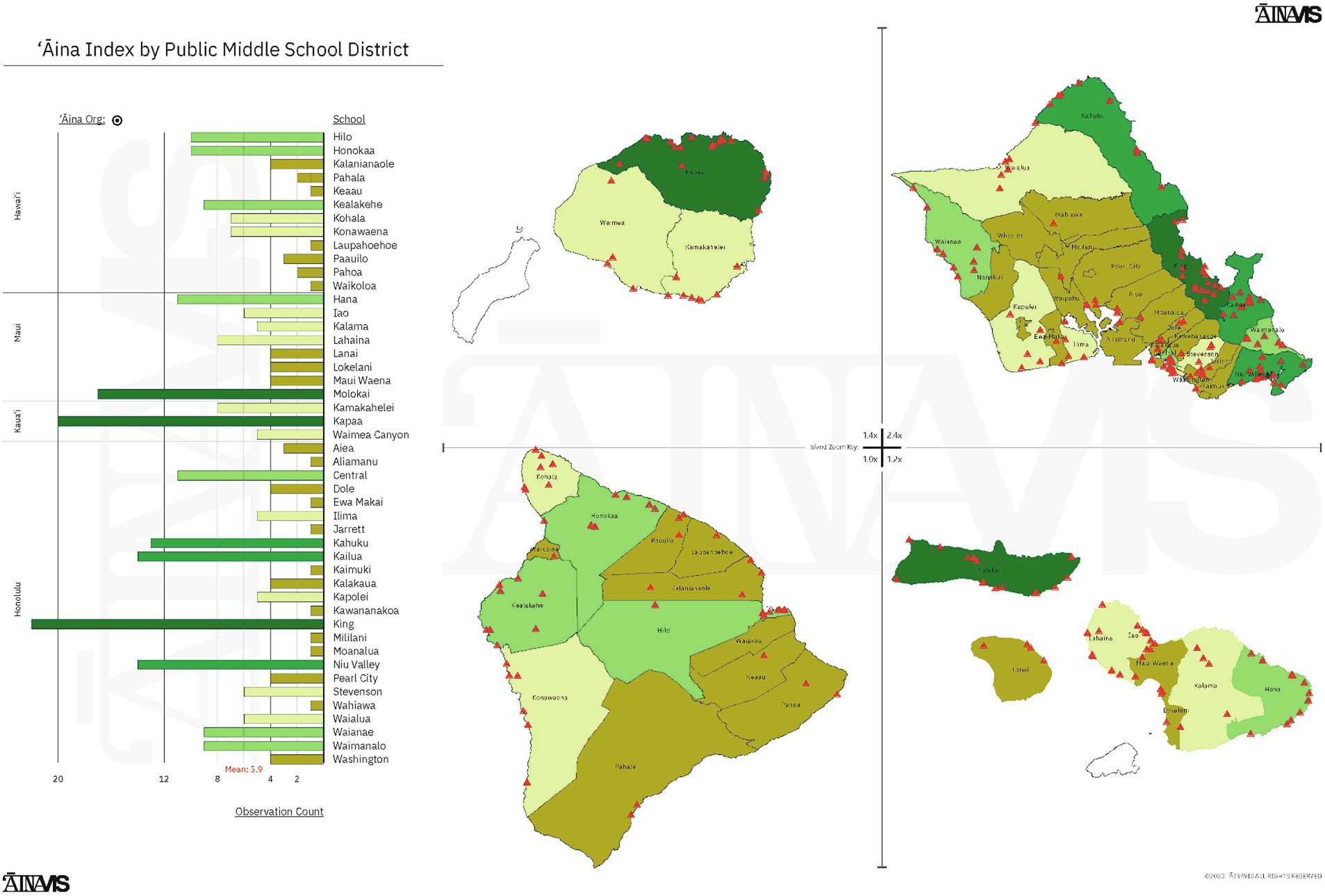

3.8 ʻĀina education nurtures the next generation of leaders

Education is a central theme in connecting the vision of ʻāina work to the future. In our interviews, eight out of twelve organizations prioritize educating youth and the community through field trips, workshops, and collaboration with schools and teachers. Schools and educators serve as bridges, connecting students to ʻāina, from preschools, through elementary, middle and high schools. Many core members and founders of ʻĀina Organizations also have ties to the undergraduate and graduate programs at the University of Hawaiʻi. Educational programs and courses at all levels nurture the next generation of ʻāina champions, and preparing learners to become future leaders, stewards, activists and founders of ʻĀina Organizations.

In turn, the involvement of schools, educators, and the younger generation nourishes the continuation of social movements and the formation of new hui (groups). In both the interviews and the ʻĀINAVIS Index, education emerges as a central theme when ʻĀina Organizations describe their work. Both school-related institutions (as funders, landowners, and networks) and school personnel (individual administrators and teachers) are integral to ʻĀina Organizations’ community networks. For instance, Kamehameha Schools, a funder, one of Hawaiʻiʻs largest landowners, and one of the United States largest educational trusts, is responsible for the establishment of several ʻĀina Organizations, leases land to around 15 different ʻāina hui, and convenes a network of over 30 different community partner groups connected to their lands. By considering connections of ʻāina networks to education, we see many such examples of collective lāhui effort to sustain and nurture ʻāina work.

The ‘Āina KUPU research team’s affiliation with the University of Hawaiʻi (UH) reveals how UH students and faculty are also part of this network. Among the interviewed partner organizations, half have core members and/or founders with some UH affiliation. Classes and projects like those featured in this article connect students to existing ʻĀina Organizations while also preparing them to found new ones, providing training in hands-on resource management, Indigenous stewardship, policy, community outreach and organizing. One of the groups we worked with, Waialeʻe Lako Pono operates on UH land, through a community stewardship agreement to restore a loʻi and fishpond at an former agricultural research station, suggesting one avenue for UH to return its land base to community care. The organization was founded in 2019 by a UH student from the area surrounding the site, who developed the work of Waialeʻe Lako Pono, and collaboration with multiple UH colleges, through his Master’s thesis. Upon graduating from UH, this individual created a job running the organization, a position now partially funded by the University. While some interviewed partners expressed frustration with UH’s presence and authority, a member from Waiakekua, who is also a UH faculty member, expressed dedication to healing and rehumanizing the university as an institution and addressing legacies of harm and inhumane treatment in part through learning from and supporting ʻĀina Organizations. One of the most fulfilling aspects of ʻāina work is education, and many ʻĀina Organizations prioritize it as a key program. Our partners highlighted education’s significance in their work, organizing field trips and workshops, with half of those organizations expressing the joy of teaching. As Kauluakalana expressed, “The kalo teaches, the wai teaches. Seeing [the youth] learn these things is really inspiring and helps me build a connection to this place. Hopefully, we see that not only with them but with more people that come our way. Actually working with our community.” Meanwhile, school districts’ proximity to ‘āina site reveals the potential for ‘āina education where educators engage with ‘Āina Organizations (Figure 6).

Figure 6. ʻĀina Index by public middle school district. This figure illustrates the distribution of ʻĀina Organizations across public middle school districts in Hawaiʻi, highlighting the varying levels of community engagement by school district. The bar chart on the left provides the observation count of ʻĀina Organizations by district, while the map on the right shows the geographic coverage of these districts. This data underscores the role of schools as critical partners in ʻĀina stewardship and community engagement (Courtesy of After Oceanic Built Environments Lab).

Adding schools and education into the ecosystem of Āina Organizations, Figure 7 illustrates relationships ofʻāina networks to outside institutions and broader sustaining movements (Figure 7). Community leaders often initiate action to tackle social issues like development, urbanization, and militarization. Some of these initiatives evolve into grassroots groups or non-profit organizations, sustaining efforts and motivating more people to get involved. The darker orange boxes in Figure 7 represent elder siblings, while the lighter ones symbolize the younger ones. These connections can be formal networks or informal relationships based on shared experiences, knowledge, and resources. Schools and educators dedicated to ʻāina work and education bring students to organizations or bring ʻāina work into classrooms. With this younger generation of stewards and activists, new groups and ongoing social movements form, and so the circles continue to grow.

Figure 7. Conceptual flowchart visualizing the layers of relationships and generational networks among multiple ʻĀina actors. The chart highlights connections between community leaders (kūpuna), earlier activist movements, ʻĀina Organizations, schools, teachers, students, and recent/ongoing activist movements. It illustrates how formal and informal networks foster collaboration and knowledge transfer across generations, reinforcing the shared responsibility for ʻĀina stewardship and resilience (Courtesy of University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa NREM 620).

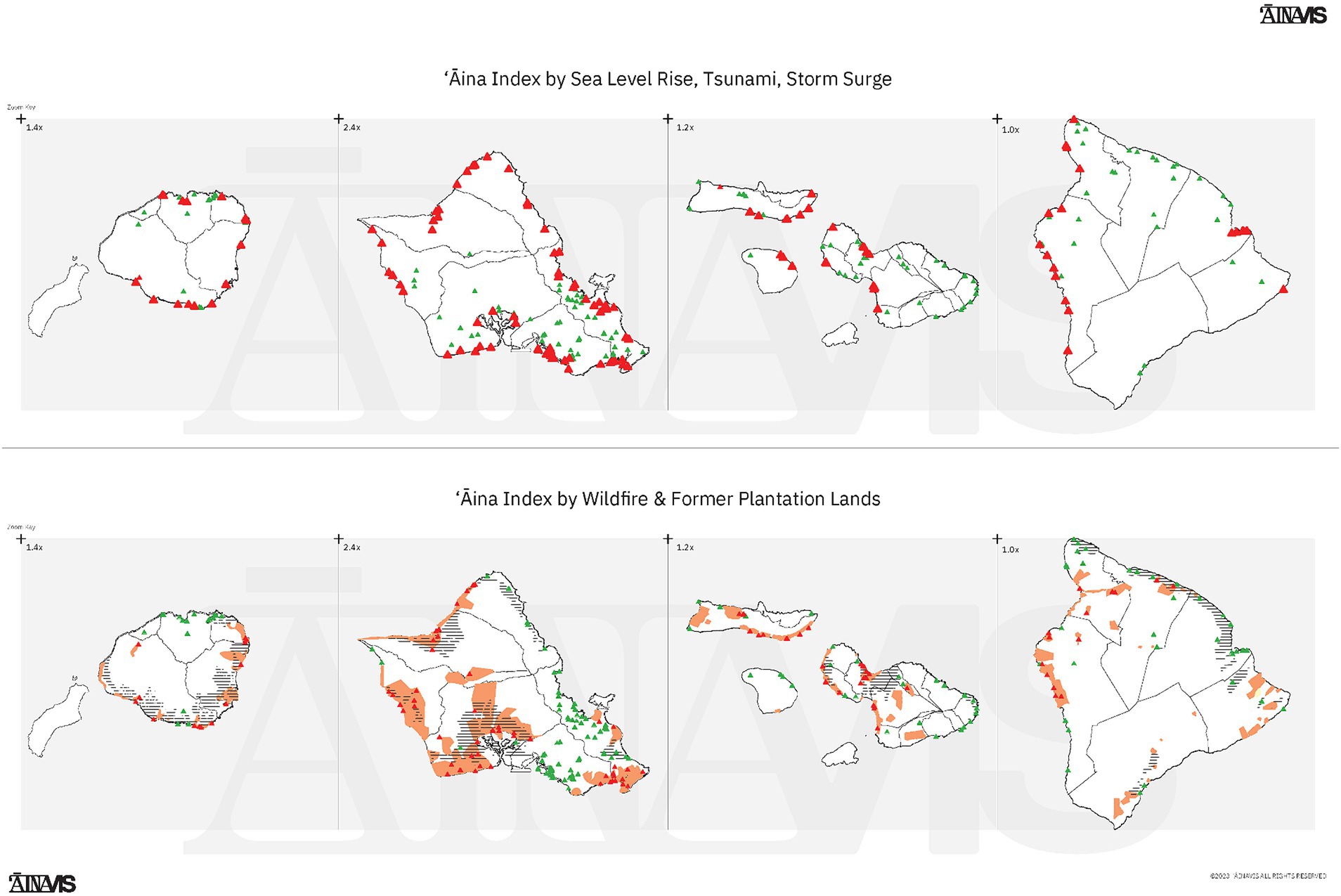

3.9 Potential of ʻĀina Organizations for building resilience to climate change

We close with a final map from the ʻĀINAVIS Index, highlighting the potential of ʻĀina Organizations to build resilience to climate change (Figure 8). The top section of this figure shows the distribution of organizations (the red-outlined triangles) in areas vulnerable to sea level rise and climate induced storm surges. The lower section of the figure shows distribution of organizations in areas prone to wildfire, many of which are former sugar lands, left fallow as plantation agriculture gives way to land banking for resorts and luxury home developments. The devastating 2023 Lāhaina wildfires highlighted the vulnerability of many Hawaiʻi communities located near these fallow weedy lands (Lum, 2024). These wildfires started when storm winds toppled power lines, sparking fires fueled by invasive species on fallow agricultural lands, then raged through Lahaina town, taking over 100 lives. In the aftermath of the fires, ʻĀina Organizations in and surrounding Lāhaina went into action as food and clothing distribution centers, hosting meetings with government officials and disseminating aid and information. These organizations also helped to envision more sustainable land uses, food and water supplies, and futures for Lāhaina, including restoration of its former waterways, taro fields, fishponds, and wetlands. These maps highlight vulnerable areas where ʻĀina Organizations are already planning for disaster response and recovery, as well as working to restore land uses that protect communities against climate change. They also show large areas (such as the Puna district on the East side of the island of Hawaiʻi), that are vulnerable to multiple climate induced threats, yet currently have no ʻĀina Organizations.

Figure 8. ʻĀina Index by sea level rise, tsunami, storm surge (top) and ʻĀina Index by wildfire & former sugar lands (bottom). The top panel maps ʻĀina Organizations in relation to areas at risk of sea level rise, tsunamis, and storm surges, with red triangles representing organizations located within those high-risk zones. The bottom panel illustrates wildfire risk areas (in orange) and former plantation lands (hatch), with red triangles showing the locations of ʻĀina Organizations that fall within these zones (Courtesy of After Oceanic Built Environments Lab).

4 Discussion

This research underscores the importance of culturally and community grounded approaches to climate change resilience. ʻĀina Organizations in Hawaiʻi illustrate the interconnectedness of people and place, highlighting the vital role of community, culture, and education in environmental stewardship and well-being. Supporting these multifaceted community efforts enhances human and ecological health, while also building climate resilience. Our collaborative research highlights the growth of organizations caring for Hawai‘i’s lands and waters, demonstrating how their work contributes to climate change adaptation and resilience for both communities and ecosystems, while informing adaptation strategies for Indigenous and local communities worldwide.

This research yielded the following lessons, which weave together key takeaways from our results and connect them to broader movements and settings:

1. Efforts around climate change and resilience made by ʻĀina Organizations’ are multifaceted and culturally grounded in people‘s active pilina (relationship) with ‘āina and its restoration. The significance of ʻāina extends beyond being just land; it also encompasses addressing climate change through food sovereignty and the health and wellbeing of both Native Hawaiian and settler communities who embrace Indigenous cultural values.

2. Indigenous and community led efforts for climate resilience depend upon restoration of cross generational relationships of people with land. The role of kūpuna, or elders, is vital in understanding climate change emphasizing resilience achieved through multi-generational commitments transferred into education of future generations. Work for climate resilience is guided and supported by ʻāina itself, rooted in connection to and knowledge of place, and in Native ways of life dependent on land and waters.

3. Community organizations building resilience and adaptation to climate change face many challenges, but can be supported by longstanding familial, community, peer and institutional networks.

4. Access to land is crucial for Indigenous and community led climate resilience, but is consistently threatened by development, urbanization, tourism, and military presence, making culturally and community grounded restoration work a political effort which relies upon restoration of sovereignty.

4.1 Significance of ʻāina and relationships of people and place in holistic and culturally grounded climate resilience

ʻĀina is a holistic concept encompassing the complex relationship between land and people. Engaging ‘āina encompasses a multiplicity of issues including climate change, food sovereignty, community health, and more (Winter et al., 2021). Efforts by ʻĀina Organizations are multifaceted and culturally grounded, rooted in active relationships with community needs and restoration (Vaughan, 2018).

Hawaiian culture provides a framework for resilience deeply connected to land and community (Harangody et al., 2023). The values, practices, and knowledge embedded in Hawaiian culture support ‘Āina Organizations and enhance their ability to adapt amid environmental and social changes (Vaughan, 2018; Barger et al., 2024). ʻĀina work also supports community members’ healing and well-being, helping them process trauma and find spiritual connection and positive relationships through ‘āina.

Climate resilience requires restoring mutually beneficial relationships between people and their environment (Maldonado and Peterson, 2018). Resilience is guided and supported by land as source instead of resource, emphasizing connections deeply rooted in cultural practices, knowledge and Native ways of life (Vaughan, 2018). The diversity of ʻĀina Organizations and their holistic approach to climate change adaptation– encompassing health, food sovereignty, and political sovereignty–highlight the importance of addressing interconnected impacts of community care and governance. This holistic approach addresses environmental, social, and cultural dimensions of resilience (Maldonado and Peterson, 2018).

A culturally grounded approach also speaks to the limitations of technocratic, and engineered solution-oriented “climate change” resilience frameworks (Harangody et al., 2023). In Hawaiʻi, one way to describe climate induced sea level rise and flooding, is in terms of the akua (gods) those changes embody. As one ocean practitioner and native scholar, Noelani Puniwai asks, “Kane (fresh water) and Kanaloa (the ocean) are coming, how do we make them welcome?” (Puniwai, 2019) Imagine the creative potential embodied in adaptation rooted in relationship, embracing perpetual cycles of change, and guided by lands and waters themselves (Johnson et al., 2022). This project, along with other work which has inspired us, speaks to the need for new words–other than adaptation, resilience, mitigation, etc.— which inspire creativity, fluidity, connectedness and generativity across generations.

4.2 Mapping and interconnectedness create realities

Mapping helps us understand interconnectedness and regional components of ʻāina work, illustrating how problems and solutions extend beyond the immediate space and time in which individual groups operate. In this research, mapping makes visible the often overlooked work of ʻĀina Organizations, connects their efforts to visualizations of climate change vulnerability and resilience, and offers potential to mobilize support and resources for this significant work. Mapping as an exercise is essentially political, as maps create realities (Fujikane, 2021; Connelly, 2022), helping to support new collective visions for the future. Much of the data that exists on Indigenous communities focuses on disparities and negative outcomes. However, mapping provides opportunities for communities to present strength-based, visual depictions of efforts that often go unrecognized (Gilmore and Young, 2012; Brown, 2020). This project demonstrates how mapping can illuminate the evolution and ongoing adaptation of ʻāina work across space and time. By showing how individual groups are part of a larger movement, mapping helps illuminate the growth and interrelationships of efforts and the socio-economic shifts that impact them.

4.3 Long-term work, genealogies of supportive networks and the importance of education

ʻĀina Organizations are supported by long-standing familial, community, peer and institutional networks that connect kīpuka across the Hawaiian islands. Supporting other research showing how social networks sustain community resource management and climate resilience (Bodin and Crona, 2009; Dacks et al., 2020), these networks in Hawaiʻi are crucial for the sustainability and effectiveness of ʻāina work. Networks facilitate support by peer organizations, mentoring by elders, and training of future generations (Berkes, 2021). These networks often form from existing community partnerships or grassroots efforts, bringing groups and practitioners together and providing a pool of resources. The genealogical ties between ʻĀina Organizations can be described using the language of “elder/younger sibling,” reflecting intergenerational support and knowledge transfer.

Education is a central theme in ʻāina work, with many organizations prioritizing ʻāina education and collaboration with schools and educators. Through educating, ʻĀina Organizations prepare future leaders, stewards and advocates. This approach nurtures the next generation of ʻāina champions, ensuring the continuation of social movements and the formation of new groups (Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua, 2013).

Universities can serve as key allies in the work of education. However, the power a university holds, its relation to the state, and the resources it can bring or withhold can be cause for distrust (Shultz, 2013; McGregor et al., 2016; Mayorga et al., 2019; Bell and Lewis, 2023). Claiming to be a “Native Hawaiian Place of learning,” UH has been complicit in, and at times actively contributed to military research and land desecration, which directly jeopardize community well-being (Kauai and Balutski, 2024). Understanding a University’s problems, bureaucracy and colonial legacy also points to the potential of creating change from within (Gelmon et al., 2013; Gordon Da Cruz, 2017; Manzo et al., 2020). This article highlights ways in which Indigenous and allied faculty can engage students in decolonizing projects and partnerships, through coursework which contributes to the work of community groups, to broader understanding of the significance of that work and to Land Back (Barger et al., 2024).

4.4 Building resilience through self-determination

Will we still have ‘āina in Hawai‘i if Native Hawaiians have been displaced due to economic and social pressures? Hawaiian scholars teach that there is no ʻāina without people (Kamakau, 1992; Winter et al., 2021). The concept of ‘āina and its relationship to people does not refer to just anyone living in a place but to those who have resided there for generations, understanding how to live in concert with their surroundings in sustainable ways that make landscapes more climate resilient (Berkes, 2021). Maintaining access to land and keeping communities living in and connected to their places is vital for ecological health, along with community identity and well-being (Greenwood et al., 2018; Jubinville et al., 2022). The relationship between kānaka and ʻāina emphasizes reciprocity, recognizing that people are the land (Baldy, 2013; Mahi, 2017; Louis and Kahele, 2017; Vaughan, 2018). Indigenous genealogical, ancestral, and familial ties to ecosystemsare essential for the success of ecosystem stewardship highlighting the threats that prevent Indigenous communities from fulfilling cross-generational responsibilities to place (Berkes, 2021).

Climate change resilience is intertwined with the need to restore justice, decision-making authority, and the ability of Indigenous and care-taking communities to remain connected to their land (Johnson et al., 2022). As in other parts of the world, such as Puerto Rico, many groups in this study first started to oppose threats such as occupation and militarization by the U.S, or to prevent specific development projects (Pizzini, 2006; Lutz, 2009; Cabán, 2023). The determination to resist was then followed by excitement to build. ‘Āina Organizations thus embody self-determination daily, as they work to protect lands and waters, while building educational, health, and social justice systems offering alternatives to the mainstream settler-colonial American society.

The restoration of land and lifeways is not just ecological or cultural, but essentially political, as reflected in the political concept of ea. (life, breath, sovereignty) (Kuwada, 2015; Vaughan, 2018). Community organizations engaged in restoration embody self determination daily (Corntassel, 2012). Contesting the neoliberal framework of environmental protection (i.e., greenwashing) and cultural resurgence, ʻĀina Organizations can be seen as Land Back projects that ultimately contribute to the political resurgence of Kānaka Maoli people (Simpson, 2017; Thompson, 2022; NDN, 2022). The separation of the ecological and the cultural from the political serves settlers’ sense of comfort while necessarily undermining Indigenous self-determination (Tuck and Yang, 2012).

Native Hawaiian independence movement artist, activist, and scholar, Haunani-Kay Trask, argued that culture–which can be easily commodified, especially under Hawaiʻi’s mass tourist industry–is not enough to achieve Hawaiian sovereignty; rather, only physical control of the land base can move a people past symbolic repatriation (Trask, 1999). Relatedly, aloha ʻāina, an important Hawaiian political concept, has been reduced to “nationalism” or “patriotism” by English scholars since the nineteenth century (Silva, 2004). Emphasizing the love and appreciation of the land rather than an empty political ideology, some Kānaka scholars highlight the necessity to build pilina, relationship, with the land to achieve political sovereignty (Osorio, 2021). Regional transformations of the built environment at the ecosystem level are crucial for biocultural recovery and sovereignty (Connelly, 2020). Grassroots, Indigenous-led and community-based projects focused on the resurgence of relationships and health of land and people, such as the ʻĀina Organizations discussed in this paper, build climate resilience within larger movements of transformation.

5 Conclusion

The ʻĀINAVIS Index and ʻĀINA KUPU Initiative are by no means a comprehensive account on Hawaiʻi’s ‘Āina Organizations and movements, but preliminary efforts made to understand the inspiring growth of ʻĀina Organizations in the past few decades. For example, using publicly available GIS datasets, combined with the ʻĀINAVIS Index, future research could analyze the growth of ʻAina Organizations in relation to land tenure arrangements, land use zoning, educational outcomes, employment opportunities, and levels of biodiversity. More qualitative research and interviews could help to understand the evolution of ʻĀina Organizations, and how they stop existing or endure over time. What conditions support long term growth and thriving of ʻĀina Organizations, and their expansion and connection to one another? How do movements, like the movement for Hawaiian Sovereignty, sustain and expand the reach of organizations, and vice versa? By further understanding and illuminating ‘āina efforts, we can enhance climate resilience and guide adaptation strategies, while simultaneously restoring independent community led decision making that honors the deep connections between people and place.

This study underscores the critical role of ʻĀina Organizations in promoting place-based climate resilience through culturally and community-grounded approaches. The growth of these organizations reflects a broader commitment to sustaining and nurturing Hawaiʻi’s land and waters. The multifaceted efforts of these groups highlight the interconnectedness of cultural heritage, environmental stewardship, and community health, demonstrating that the well-being of ʻāina and the people are deeply intertwined. The collaborative efforts of ʻĀina Organizations in Hawaiʻi provide a powerful model for building climate resilience that is holistic, culturally grounded, and community-driven. This research highlights the critical role of ʻĀina Organizations in addressing climate change, promoting social justice, and fostering community well-being. Their work offers valuable lessons for Indigenous and local communities worldwide, emphasizing the importance of cultural resilience, supportive networks, and the centrality of land and people in climate adaptation efforts.

As we conclude this article, dear reader, we want to send our mahalo to you. Thank you for joining us on our journey through the lands and life ways of Hawai‘i as we explore what it means to be part of a community, and the many facets of resilience that are critical to our collective well-being. As we close our time together, we hope this circle and ipu filled with stories, people, places and practice can nourish you and support your work as well. We often close our circles in gratitude, with each participant sharing something they are grateful for. The collective gratitude, voiced in turn, provides an important closing and a springboard to future potential. As we invite you to share, we start with our own…

Mahalo to the kūpuna, the elders and ancestors who taught us that to know the future, we must look behind us.

Mahalo to the parents raising children who remind us to think of their future, of the children yet unborn, the lands they’ll live upon and the ancestors they’ll become.

Mahalo to the communities that teach and inspire and root us.

Mahalo to the lands and waters that nourish us all.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the dataset is restricted to participants whose informed consent was obtained in the research process. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to ZG1haGlAY29uc3VlbG8ub3Jn and/or c2VhbkBhZnRlcm9jZWFuaWMuY29t.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Hawaiʻi Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because the survey and interviews present minimal risk to participants.

Author contributions

DM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Methodology. KS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. RS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Data curation. EK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization. MV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision. SC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding for ‘Āina KUPU is provided by the USDA Integrated Hatch Project, and ʻĀINAVIS via Consuelo Foundation, After Oceanic Built Environments Lab, and The Akaka Foundation for Tropical Forests.

Acknowledgments

The ʻĀINAVIS Hui on the behalf of Consuelo Foundation and After Oceanic gives extra special acknowledgement to the people and organizations who have been supportive of the humble project since it first began in 2019, especially, Heather McMillen (2020), Rachel Dacks (2020), Sanoe Burgess (2020), Brant Chillingworth (2019), Andrew Menor (2019), and Alex Connelly (2021); Division of Forestry and Wildlife, Hau’oli Mau Loa Foundation, Kua‘āina Ulu ‘Auamo, Hawai‘i Futures, Aunty Puanani Burgess, and all those who have encouraged and contributed to the conversation. The ʻĀina KUPU project would not be possible without the generosity of the following partnering organizations, for sharing their moʻolelo and wisdom with the project team and for teaching us: ‘Ewa Limu Project, Hoʻoulu ʻĀina at KKV, Kauluakalana, Kuhiawaho, Livable Hawaiʻi Kai Hui, Mālama Loko Ea, Mālama Mākua, Makaʻalamihi Gardens, Nā Wai ʻEkolu, Protect & Preserve Hawaiʻi, Waiakeakua, Waialeʻe Lako Pono. Alyssandra Rousseve, Destiny Apilado, Breanne Fong, Leigh Engel, Jolie Wanger, Isaiah Wagenman contributed greatly to the project reviewing and coding interview transcripts. The students’ active engagement in NREM 625 (spring 2022) and NREM 620 (Fall 2022) at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa made the scale of this work possible. We also want to thank Miwa Tamanaha and Debbie Gowensmith, humble thought leaders and founders of Kua ʻĀina Ulu ʻAuamo. We honor Puni Jackson, Casey Jackson and Kanoa OʻConnor of HoʻuluʻĀina, who hosted two classes mentioned in this project and many others before at their kīpuka in the back of Kālihi Valley. Their insights and example have helped to inspire and guide this work, including circles of opening and closing over the past 10 years together.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

4. ^This opening paragraph is inspired by and adapted from the "Aloha Circle" Ho'oulu 'Āina holds when opening up community gatherings and inviting folks into the valley of Kalihilihiolaumiha.

1. ^Echoing a community member’s warning against creating exclusive categories, ‘ĀINAVIS and ‘Āina KUPU do not intend to create an authoritative definition of “‘Āina Organizations.” However, for the purpose of data analysis and having a consistent dataset, along with graduate students, the team created a “decision rubric” to revisit and refine the list of organizations. For more information, please see https://www.ainavis.info/.

2. ^‘Āina Kupu engaged students from the Social Science Field Methods for Environmental Research course held in spring 2022 (NREM 625) and the Collaborative Care and Management of Natural Resources graduate seminar held in fall 2022 (NREM 620). Funding for ‘Āina KUPU is provided by the USDA Integrated Hatch Project, and ʻĀINAVIS via Consuelo Foundation, After Oceanic Built Environments Lab, and The Akaka Foundation for Tropical Forests.

3. ^A detailed methodology of the refinement process can be found at https://www.ainavis.info/Index-Process-Methodology

References

Aloha Challenge. (n.d.) Local Food Production & Consumption: 05. Available at: https://alohachallenge.hawaii.gov/pages/lfp-05-consumption (Accessed September 10, 2024).

Andrade, C. (2008). Hā‘ena: Through the eyes of the ancestors. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Baldy, C. R. (2013). Why we gather: traditional gathering in native Northwest California and the future of bio-cultural sovereignty. Ecol Process 2:17. doi: 10.1186/2192-1709-2-17

Barger, S., Vaughan, M., Aiu, C., Akutagawa, M. K. H., Beall, E. C., Luck, J., et al. (2024). Kīpuka Kuleana: restoring relationships to place and strengthening climate adaptation through a community-based land trust. Front. Sustain. 5:1461787. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2024.1461787

Bell, M., and Lewis, N. (2023). Universities claim to value community-engaged scholarship: so why do they discourage it? Public Underst. Sci. 32, 304–321. doi: 10.1177/09636625221118779

Berkes, F. (2021). Advanced introduction to community-based conservation. Cheltenham, UK Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing (Elgar Advanced Introductions).

Bodin, Ö., and Crona, B. I. (2009). The role of social networks in natural resource governance: what relational patterns make a difference? Glob. Environ. Chang. 19, 366–374. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.05.002

Brown, M. (2020). Diversity and adaptation in local Forest governance in Yunnan, China. Hum Ecology 48, 253–265. doi: 10.1007/s10745-020-00149-1

Cabán, P. (2023). “Gringo Go Home, Puerto Rico is Not for Sale.” in The American Prospect. Availabe at: https://prospect.org/power/2023-08-21-gringo-go-home-puerto-rico-not-for-sale/ (Accessed August 21, 2023).

Connelly, S. (2010). Hawai‘i-Futures: interventions for island urbanism. Available at: https://hawaii-futures.com/

Connelly, S. (2020). “Our City as Ahupuaa” in Value of Hawaii 3. eds. N. Goodyear-Kaopua, C. Howes, J. K. K. Osorio, and A. Yamashiro (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press), 231–236.

Connelly, S. (2022). ʻUkoʻa Loko Ea fishpond: digital mapping and spatial analysis of O'ahu and American infrastructure projects since 1898. Hawaii. J. Hist. 56, 79–111. doi: 10.1353/hjh.2022.a907633

Corntassel, J. (2012). Re-envisioning resurgence: indigenous pathways to decolonization and sustainable self-determination. Decolon. Indigen. Educ. Soc. 1, 86–101.

Cruz, L., Rodrigues, S., and Cataldo, K. (2022). Mālama Mākua: Piko of Peace. Hawaiʻi rising [podcast]. PodBean. Available at: https://hawaiipf.podbean.com/e/17-malama-makua-piko-of-peace/

Dacks, R., Ticktin, T., Jupiter, S. D., and Friedlander, A. M. (2020). Investigating the role of fish and fishing in sharing networks to build resilience in coral reef social-ecological systems. Coast. Manag. 48, 165–187. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2020.1747911

Diver, S., Vaughan, M. B., and Baker-Medard, M. (2024). Collaborative care in environmental governance: restoring reciprocal relations and community self-determination. Ecol. Soc. 29:7. doi: 10.5751/ES-14488-290107

Fujikane, C. (2016). Mapping wonder in the Māui Mo‘olelo on the Mo‘o‘āina: growing Aloha ‘Āina through indigenous and settler affinity activism. Marvels Tales 30, 45–69. doi: 10.13110/marvelstales.30.1.0045

Fujikane, C. (2021). Mapping abundance for a planetary future: Kanaka Maoli and critical settler cartographies in Hawai’i. Durham: Duke University Press.

Gelmon, S. B., Jordan, C., and Seifer, S. D. (2013). Community-engaged scholarship in the academy: an action agenda. Magazine High. Learn. 45, 58–66. doi: 10.1080/00091383.2013.806202

Gerhardt, C. (2020). “Sea level rise, Marshall Islands and environmental justice” in Climate justice and community renewal: Resistance and grassroots solutions. eds. B. Tokar and T. Gilbertson (London: Routledge), 70–81.