- 1Faculty of Business, Economics and Management Information Systems, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany

- 2Department of Logistics and Supply Chain Management, Ho Technical University Business School, Ho Technical University, Ho, Ghana

- 3Faculty of Computer Science, Rosenheim Technical University of Applied Science, Rosenheim, Germany

This research examines the potential outputs, outcomes, and impacts of the German Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains (LkSG) on the smallholder cocoa farmers in West Africa. The study primarily relies on a literature review and an impact pathway to conduct a systematic analysis to identify the potential effects of the LkSG on smallholder cocoa farmers. The findings indicate that some, but not all of the risks addressed by the LkSG align with those faced by smallholder cocoa farmers and their families. Additionally, the research also reveals weaknesses, particularly in managing environmental risks, which the LkSG does not adequately cover. Our findings show that in the short- and medium-term, the LkSG has no potential effects on smallholder cocoa farmers. Furthermore, the potential positive impacts of the law on smallholder cocoa farmers will take a long time to realize, as the LkSG considers primarily tier-1 suppliers. Companies in Germany might reassess their supply chains to strive for an LkSG-risk-free supply chain, which could in the long term have sustained impacts on smallholder cocoa farmers. However, we recommend a comprehensive risk analysis of the cocoa supply chain to enhance the human rights of cocoa farmers.

1 Introduction

Many countries have enacted regulations regarding human rights due diligence (HRDD) or are planning to introduce them (United Kingdom Government, 2015; République Francaise, 2017; Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken, 2019; Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021; European Commission, 2022b). The regulations aim to improve the safeguarding of human rights and target employees in companies with a primary focus on developing countries, where there is inadequate protection and a prevalence of human rights and environmental risks and violations (United Nations, 2011; Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021). The question then arises as to what extent these HRDD regulations impact developing countries. To answer this question, this paper aims to analyze the newly enacted Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz (LkSG), in English: Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains, for companies in Germany from the perspective of smallholder cocoa farmers in West Africa and potential effects on them.

Retailers and chocolate manufacturers in Germany are part of the global cocoa supply chain, with smallholder cocoa farmers in West Africa saving as key upstream participants (Fountain and Huetz-Adams, 2015) by producing more than 65% of the world's cocoa beans (International Cocoa Organization, 2020a). Therefore, as part of the global cocoa supply chain, smallholder cocoa farmers may feel some spillover effects from the implementation of the LkSG. In addition, the primary aim of the LkSG is to improve fundamental human rights and environmental protection in global supply chains (Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung, 2021).

Therefore, the research question is:

What are the potential effects of the LkSG on smallholder cocoa farmers in West Africa?

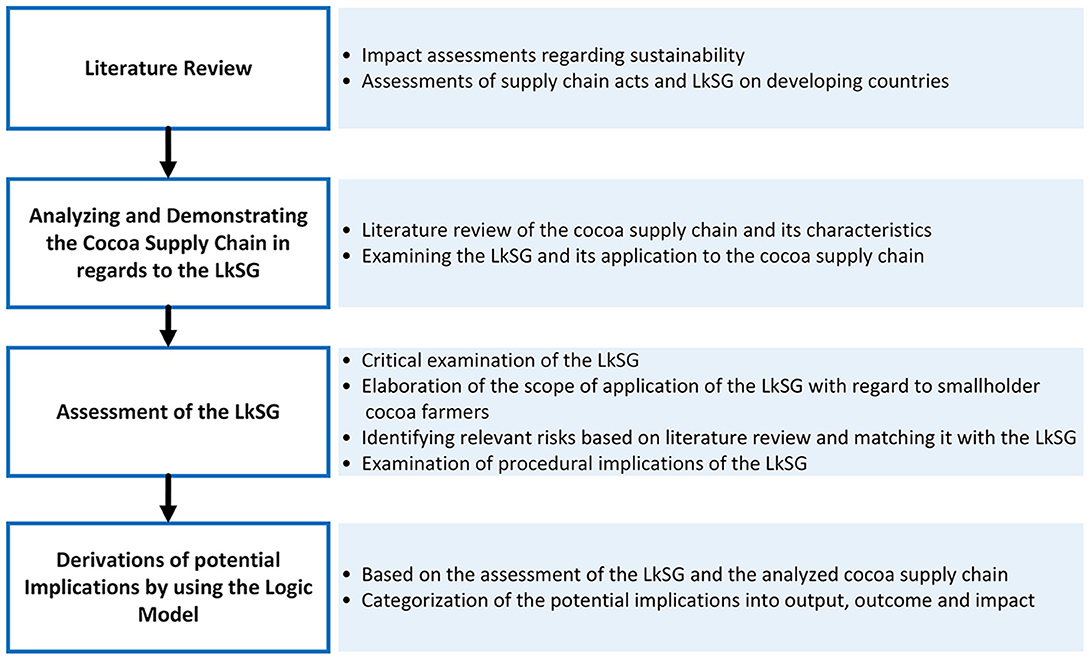

To answer our research question, we used a methodology encompassing both a literature review and a logic model. This approach facilitated a systematic and in-depth analysis to identify the potential effects of the LkSG on smallholder cocoa farmers. Due to the rather recent enactment of the LkSG in Germany in 2023, there is a lack of available data and identifiable effects, particularly in developing countries. Furthermore, since the affected chocolate manufacturers and retailers are required by the LkSG to release their reports for 2023 by April 2024, these data are unavailable for our study. For this reason, we conducted a critical examination of the legal text of the LkSG in light of existing literature, emphasizing logical interdependencies. To capture the perspective of smallholder cocoa farmers in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire, a comprehensive review of the cocoa supply chain with a focus on smallholder cocoa farmers was carried out. This aimed to identify the circumstances surrounding smallholder cocoa farmers and delve into their socio-cultural norms and values for the analysis of the LkSG from their perspective. Our findings were then organized through a logic model. The logic model has been proven to be an appropriate method in various studies (Springer-Heinze et al., 2003; Stewart et al., 2004; Wagner et al., 2019; Barnett et al., 2020; Truong et al., 2021; Lovell et al., 2023), especially for assessing different kinds of new programs to identify potential effects (Stewart et al., 2004; Ebrahim and Rangan, 2014; Barnett et al., 2020; Truong et al., 2021; Lovell et al., 2023). Subsequently, we discussed the potential outputs, outcomes, and impacts of the LkSG on smallholder cocoa farmers in West Africa. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first examination of the LkSG and its effects on smallholder cocoa farmers, providing valuable insights into their perspective. Moreover, the study assesses the real-world implications of the LkSG by determining whether it can effectively enhance due diligence practices and promote supply chain sustainability in the global cocoa supply chain, with a specific focus on its first link, the smallholder cocoa farmers.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the fundamentals on impact assessments and HRDD regulations as well as the current state of research regarding the effects of the LkSG on developing countries. Section 3 outlines the LkSG and provides an overview of insights and challenges within the cocoa supply chain. Section 4 analyzes the LkSG from the perspective of the smallholder cocoa farmers, examining the extent to which the LkSG addresses their identified risks. Additionally, this section explores the scope and procedural implications of the LkSG as well as the role of NGOs and the media. Furthermore, potential outputs, outcomes, and impacts of the LkSG on smallholder cocoa farmers are discussed. The final Section 5 then outlines the research findings and points out limitations and recommendations for further research.

Our study advances the scholarly discourse on supply chain legislation. The theoretical contribution of this study lies in the extension of theoretical frameworks for impact assessments, especially in the realm of supply chain legislation using the example of the LkSG. Our analysis of the LkSG within this theoretical context provides a deeper understanding of its implications, particularly considering the perspective of smallholder cocoa farmers in West Africa. Furthermore, the study yields practical insights relevant to policymakers, chocolate manufacturers, and retailers affected by the LkSG. Particularly, our analysis illuminates the risks pertinent to smallholder cocoa farmers' socio-cultural norms and values, and the potential effects of the LkSG on their livelihoods.

2 Literature review

This study adopts a literature review to assess existing knowledge on the subject. The increased pace, fragmentation, and interdisciplinary knowledge in business research, present challenges for staying current and comprehensively evaluating cutting-edge research, underscoring the critical role of the literature review as a research method in navigating this complex landscape. This emphasizes the importance of literature review as a research method and its subsequent wide adoption for scientific investigations (Snyder, 2019). A literature review not only offers an overview of disparate and interdisciplinary research areas but also serves as a crucial tool for synthesizing evidence on a meta-level, revealing gaps that require further research—integral to the development of theoretical frameworks and conceptual models (Snyder, 2019; Bai et al., 2021; Lage, 2022).

In conducting our literature review for this academic paper, we systematically employed keyword searches across electronic databases, notably Google Scholar, in both German and English languages to identify pertinent materials aligned with our research inquiry. In elucidating our analysis, particularly concerning the perspectives of smallholder cocoa farmers, their risks, and the exploration of their cultural norms and values, we confined our examination exclusively to scholarly literature from reputable journals and reports to ensure academic integrity and credibility. While our core analysis was firmly rooted in academic literature, we acknowledged the necessity of incorporating industrial literature for specific information about retailers or chocolate manufacturers. This included reports and official websites, which, although not part of our central analysis, provided valuable insights into the cocoa industry. For the LkSG, our resources included the legal text and scientific articles from recognized journals and publishers. Given the limited number of articles published on LkSG, we found it beneficial to incorporate literature from both academic and practical sources, thereby ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter. This approach allowed us to enrich our analysis by leveraging insights from diverse perspectives, enhancing our literature review's robustness and depth.

2.1 Fundamentals on impact assessments

In literature, various types of impact assessment with distinct origins and applications exist (Annandale, 2001; Harrison, 2011; Adebayo et al., 2016; Islam and van Staden, 2022; Ngan et al., 2022). Impact assessment is defined as a process aimed at identifying the effects of policies, projects, or programs (Sadler, 1996; Harrison, 2011; European Commission, 2023). It can be applied to both ex-post and ex-ante activities (Harrison, 2011; Carini et al., 2018). Furthermore, some studies narrow down this applied impact assessment to what is referred to as a human rights impact assessment. However, within the literature, a uniform understanding of the definition and implementation process is lacking (Harrison, 2011; European Commission, 2022a; Schwarz et al., 2022). Additionally, some studies (Springer-Heinze et al., 2003; Stewart et al., 2004; Wagner et al., 2019; Barnett et al., 2020; Truong et al., 2021; Lovell et al., 2023) employ a framework in the form of an impact pathway, also known as a logic model, to systematically analyze the potential effects of new programs. Thereby, the identified implications are distinguished within a temporal dimension (Ebrahim and Rangan, 2014; Nelson et al., 2014). However, the term impact assessment is often inconsistently defined and used for various purposes (Ebrahim and Rangan, 2014; Adebayo et al., 2016; European Commission, 2016; Wongrak et al., 2021). In this study, we distinguish between the three key concepts: output, outcome, and impact, constituting the concept of the impact pathway. Outputs in this vein mean immediate results, while outcomes are defined as medium- and long-term results of activities. Impacts are characterized as long-term effects, implying a sustained change. For instance, an output may be training farmers. Outcomes, in turn, represent sustained changes such as enhanced farming practices or increased income. Impacts, exemplified in the farmer training example, encompass broader societal benefits, such as sustained reduction of poverty and improved social well-being (Stannard-Stockton, 2010; Ebrahim and Rangan, 2014; Nelson et al., 2014). Nonetheless, outputs do not always lead to outcomes, and outcomes do not automatically result in impact (Ebrahim and Rangan, 2014; Nelson et al., 2014).

2.2 Assessments of the LkSG on developing countries

The LkSG is a new and highly debated law in Germany, passed in July 2022, and came into force on January 1, 2023 (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021). Few scientific publications have engaged with the LkSG since it is relatively recent (Dovbischuk, 2021; Gehling et al., 2021; Bäumler, 2022; Koos, 2022). However, publications have steadily increased since the introduction of the LkSG.

The literature focuses primarily on discussing legal perspectives and examining the effects of the LkSG on companies in Germany rather than on developing countries (Gehling et al., 2021; Berger, 2022; Koos, 2022; Johann et al., 2023; Lorenz and Krülls, 2023). Few scientific studies mention the potential negative implications of the LkSG on developing countries without a comprehensive assessment (Felbermayr et al., 2022; Kolev and Neligan, 2022). However, some studies align partly with our research question. For example, the scientific study by Komba et al. (2023) on the effects of the upcoming European Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) on the garment industry in Ethiopia and the coffee industry in Tanzania draw conclusions based on their findings from their literature review. Besides their methodology, their findings may be of limited relevance to this study, as they primarily suggest that companies and smallholder farmers in Ethiopia and Tanzania adapt to the CSDDD to maintain their appeal to European markets (Komba et al., 2023).

The study by Müller et al. (2022) explores how public-private cooperation can strengthen supply chain laws and increase sustainability in the case of the South African mining sector. The authors did not especially analyze the effects of the LkSG but comment in their report that the LkSG would have no implications on mines in South Africa. Müller et al. (2022) reason that there are no major German mining companies on-site that could exert influence on the enforcement of the LkSG. They suggest that Germany should advocate for a risk-based approach in the planned CSDDD to minimize social and environmental risks. The authors argue that such an approach would cause the private sectors to exceed the minimum legal standards and effectively address the shortcomings of the LkSG (Müller et al., 2022). The conclusion drawn by Müller et al. (2022) is in line with the main criticism of the LkSG, asserting that companies in Germany subject to the LkSG should primarily focus on their direct suppliers, rather than encompassing all suppliers along their supply chain including developing countries (Initiative Lieferkettengesetz, 2021; Ruggie, 2021). The study by Kolev and Neligan (2022) primarily focuses on the expected effects of the LkSG on affected companies in Germany. However, the authors draw conclusions for developing countries based on their survey results: Developing countries with poor governance must expect potential employment losses and negative development effects in connection with foreign investment (Kolev and Neligan, 2022). Furthermore, risk profiles of every cocoa-producing country are available based on a Western perspective, which is provided in the context of a guideline for cocoa-producing companies affected by the LkSG (Hütz-Adams, 2021). This is a starting point for a critical analysis of the addressed risks in the LkSG from the smallholder cocoa farmer's perspective.

At present, there are only a few publications about the LkSG, that consider the perspective of developing countries. In addition, broad assessments of the potential effects of the LkSG in developing countries are lacking. Hence, our study differs from the above literature by analyzing the newly implemented LkSG and its human rights due diligence implications on smallholder cocoa farmers in West Africa. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first comprehensive analysis and discussion of the LkSG and its effects in developing countries with a special focus on smallholder cocoa farmers.

3 Comprehending the LkSG and the cocoa supply chain

This section provides an overview of the LkSG to enhance understanding its due diligence framework. Furthermore, we demonstrate the cocoa supply chain while exploring the issues smallholder cocoa farmers face in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire to seek deeper insights into their situation. This contextual information proves crucial for our subsequent analysis of the LkSG in Section 4. Figure 1 presents a flowchart outlining our research methodology, improving clarity, and understanding of our investigative process.

3.1 German Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains (LkSG)

The LkSG was passed in July 2021 and became effective in January 2023. The law applies to companies in Germany with more than 3,000 employees and, from 2024, with more than 1,000 employees within Germany, wherein employees of affiliated companies in Germany shall also be considered and deployed employees. The LkSG aims to prevent or minimize human and environmental-related risks or to end the violation of human rights or environmental-related obligations. The appropriate cause of action by companies depends on the nature and scope of their business activities and their level of influence (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021). Furthermore, the LkSG primarily focuses on the company's own business unit and its direct (tier-1) suppliers; indirect (tier-n) suppliers only need to be considered when substantial knowledge is available. Substantial knowledge in the vein of the LkSG, means that a company has an actual indication of a human rights or environmental-related violation within its supply chain (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021). Furthermore, the actions taken by companies are also influenced by the expected severity or probability of the violation. The LkSG imposes a duty to make an effort but does not guarantee an obligation and does not entail civil liability in case of violations (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021). This means that affected companies must not guarantee that their supply chains are free of human rights and environmental-related risks. They instead need to prove that they comply with the due diligence regarding the LkSG within reason (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021; Deutscher Bundestag, 2021).

In 2024, the LkSG is expected to apply directly to about 2,900 companies in Germany (Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2021). Among the sweet industry companies in Germany, only 18 have over 500 employees (Bundesverband der Deutschen Süßwarenindustrie e.V., 2021). Considering the employee threshold, only a few companies in the chocolate sector might have to implement due diligence, according to LkSG. However, even small and medium enterprises, falling below the employee threshold, are indirectly impacted. Although they are not under the LkSG, they must comply with certain due diligence requirements passed on by the companies concerned with their suppliers (Konrads and Walter, 2022).

3.2 The cocoa supply chain in light of the LkSG

The cocoa supply chain starting in West Africa, particularly in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire, involves numerous actors and is lengthy and complex (Kraft and Kellner, 2022). Moreover, cocoa plays a crucial role in the region's economy and is a significant source of income for numerous smallholder families involved in cocoa farming (Mujica Mota et al., 2019; European Commission, 2021). The smallholder cocoa farmers in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire, about 1,650,000 farmers and families (International Labour Organization, 2021; COCOBOD, 2023) living at the subsistence level, struggle against economic, social, and environmental issues (International Labour Organization, 2021; Fountain and Huetz-Adams, 2022). Such as low income, lack of access to electricity and clean water, and inadequate road infrastructure (Fountain and Huetz-Adams, 2022).

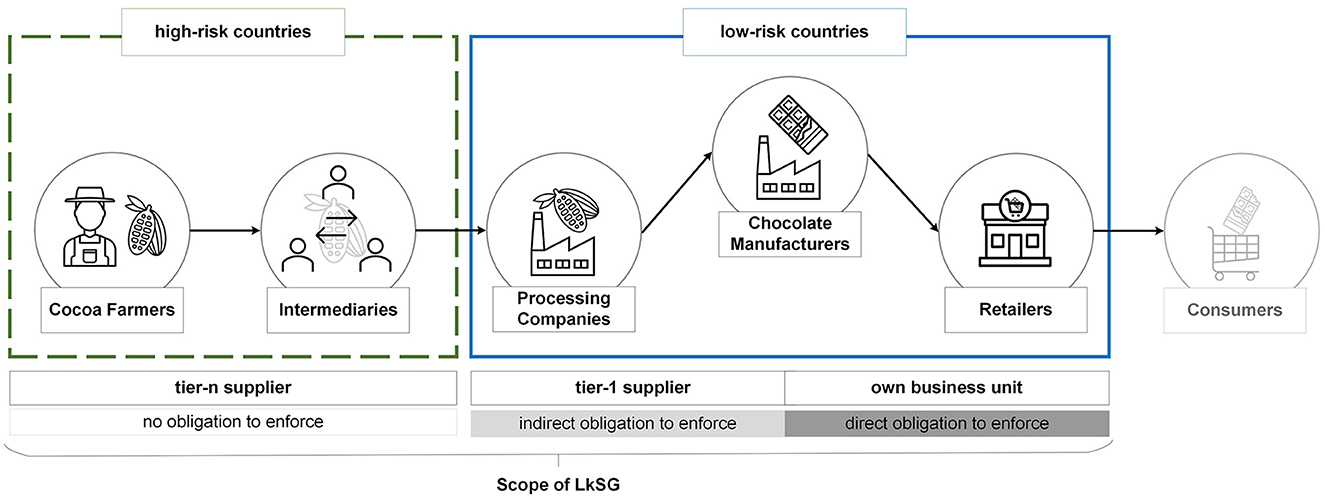

Figure 2 represents the cocoa supply chain, starting with the smallholder cocoa farmers based in a high-risk country in view of the LkSG. The scope of the LkSG varies along the cocoa supply chain, determining which actors are responsible for enforcing the LkSG. Based on the LkSG, the primary focus is on the affected companies' own business units and their tier-1 suppliers. While retailers and chocolate manufacturers in Germany are directly affected by the law, the chocolate manufacturers can be considered both as their own business unit and as tier-1 suppliers to the retailers.

Figure 2. Generalized cocoa supply chain from the perspective of the LkSG. (In)directly affected entities by the LkSG are displayed by square, while those unaffected are displayed by square outlined with dashed lines.

Retailers like Aldi, EDEKA, or REWE, who are also obliged to apply the LkSG, have their tier-1 suppliers (chocolate manufacturers) mainly in Europe. Looking at chocolate manufacturers in Germany, such as Ferrero, Mars, or Alfred Ritter,1 their tier-1 suppliers for cocoa products are usually processing companies like Barry Callebaut, headquartered in Switzerland, or Cargill, headquartered in the USA, both of which have sites in Germany (see Figure 2) (Cargill Incorporated, 2022; Kraft and Kellner, 2022; Bary Callebaut AG, 2023). Though 80% of the world's cocoa beans are produced in West Africa, only about one-third of them are processed there (International Cocoa Organization, 2020b,c,d). This indicates that the tier-1 suppliers of chocolate manufacturers in Germany, mainly processing companies, are primarily located in low-risk countries. The cocoa farmers and intermediaries operate in high-risk countries and serve as tier-n suppliers to German retailers and chocolate manufacturers that are consequently not affected by the LkSG (see Figure 2).

The governmental institutions, the Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD) and the Conseil du Café-Cacao (CCC) in Côte d'Ivoire both regulate the cocoa market and prices in their respective countries (Mujica Mota et al., 2019; COCOBOD, 2022). The cocoa farmers in Ghana are not mandated to sell their beans to any entity apart from the Licensed Buying Company (LBC) (Cocoa Marketing Company (GH) LTD, 2022; COCOBOD, 2022), the cocoa farmers in Côte d'Ivoire can sell their beans directly to private buyers (pisteurs), cooperatives, exporters, or processing companies (Mujica Mota et al., 2019). Despite the combined efforts by the Ivorian (CCC) and Ghanaian (COCOBOD) institutions to introduce the Living Income Differential (LID) in 2019 to raise the global cocoa market price (Cote D'Ivoire-Ghana Cocoa Initiative, 2021), many smallholder cocoa farmers continue to receive low incomes (Fountain and Huetz-Adams, 2022; Boysen et al., 2023). This is primarily due to the low farm gate prices for cocoa beans (Fountain and Huetz-Adams, 2022; Boysen et al., 2023).

4 Assessment of the LkSG from the perspective of smallholder cocoa farmers

As described in Section 3.1, the LkSG aims to safeguard human rights and the environment. Given that human rights abuses and environmental challenges tend to be more prevalent in developing countries, as opposed to Europe or, Germany, it is important to analyze whether the LkSG has potentially positive implications for developing countries. Hence, this section examines the LkSG from the standpoint of smallholder cocoa farmers in West Africa, specifically in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire.

4.1 Scope of the LkSG with regard to smallholder cocoa farmers

The LkSG applies only to companies with at least 1,000 employees in Germany and encompasses its business unit and tier-1 suppliers. It is important to note that the company's business operations may include subsidiaries in Germany and abroad, provided that the parent company exercises significant influence over them (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021). Thus, affected processing companies and chocolate manufacturers based in Germany are only obligated to consider due diligence within their business units and tier-1 suppliers. As demonstrated in Figure 2, smallholder cocoa farmers are not tier-1 suppliers of retailers or chocolate manufacturers in Germany, but rather tier-5 and tier-4 suppliers. Consequently, the smallholder cocoa farmers are not directly captured in the scope of the LkSG and must only be considered when the retailers or chocolate manufacturers receive an actual indication of human rights or environmental violations covered by the LkSG (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021). Such information may be received through the complaints procedure the companies have to establish under the LkSG.

In contrast to the LkSG, the planned CSDDD encompasses the entire supply chain. Consequently, smallholder cocoa farmers in Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana would need to be considered, rather than in individual cases only, as currently practised within the LkSG (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021; European Commission, 2022b). Therefore, the LkSG might have a limited effect on smallholder cocoa farmers. However, it is also possible that the procedural implications resulting from the LkSG may already show initial improvements in the challenges of smallholder cocoa farmers.

4.2 Relevant risks for the smallholder cocoa farmers addressed in the LkSG

The LkSG addresses human rights risks and environmental-related risks, which are further defined within the LkSG (§ 2 para. 2 and para. 3 LkSG). The subsequent section aims to identify the relevant risks that the LkSG addresses concerning smallholder cocoa farmers in West Africa and to evaluate whether these risks can mitigate the challenges faced by these farmers and improve their well-being. According to § 2 para. 2 of the LkSG, 20 definitions are stated under human rights and environmental risks (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021). Out of the 20 definitions, we identified five aspects that might be relevant and partly challenging for smallholder cocoa farmers. The five relevant risks were identified based on a review of the literature on human rights and environmental risks associated with smallholder cocoa farmers in West Africa (Babo, 2014; Buhr and Gordon, 2018; Hütz-Adams, 2021; LeBaron, 2021). Following that, we compared these identified risks with those addressed in the LkSG. In the following subsection, we point out and discuss these aspects.

4.2.1 Child labor under 15 years (§ 2 para. 2 no. 1 LkSG)

From the developed world's perspective, the work activities of children under the age of 15 violate human rights and are a relevant main risk for smallholder cocoa farmers addressed in the LkSG. Even though the Ivorian and Ghanaian governments have agreed to the Harkin and Engel protocol as well as to the Convention on Child Labor by the International Labour Organization (ILO), we need to understand that the concept and definition of child labor in these countries are seen as Western-centered international standards (International Labour Organization, 2011, 2023a; Babo, 2014, 2019; Abdullah et al., 2022). Therefore, it is important to consider the Ghanaian and Ivorian socio-cultural norms and values, which are highly similar due to their shared history. Their norms and values make it difficult to fully align with international child rights standards (Babo, 2014; European Commission, 2021). From the smallholder cocoa farmers' perspective, involving their children in farm work is perceived as educational, not child labor, and farming is valued more than formal education (Babo, 2014; Krauss, 2016). This arises from the belief that farming, unlike formal education, ensures a future for their children. The decision to involve children in farm work is based on capability, not age, to provide practical skills and experiences. This process is viewed as socialization, preparing children for independent adulthood and future family responsibility (Babo, 2014; Krauss, 2016; Adonteng-Kissi, 2021). In line with socio-cultural norms, Ghanaian and Ivorian children bear family responsibilities from birth, supporting their parents in farming to enhance family income to meet essential needs, as hiring additional labor is often financially unfeasible for smallholder cocoa farmers. Most Ghanaians and Ivorians view child labor as culturally acceptable since it has been in practice for decades. They rather see child labor and children's rights as a foreign concept inconsistent with their social norms and values (Babo, 2014, 2019; Krauss, 2016; Adonteng-Kissi, 2021). The study by Krauss (2016) indicates that the socio-cultural norms and values are sustained within farming communities and by politicians, as shown by a statement made by a Ghanaian Minister of Education during his research.

To summarize, child labor by smallholder cocoa farmers is perceived as a human rights violation primarily by Western countries rather than by the smallholder cocoa farmers themselves. For these farmers, their children working alongside them on the farm is seen as a form of support and education, aligning with their socio-cultural norms. However, both Ghanaian and Ivorian governments being signatories to the ILO convention to reduce child labor, view the international standard as problematic (International Labour Organization, 2023d). Despite, these agreements about 60% of all children in all agricultural households are still involved in cocoa farming, posing a risk for smallholder cocoa farmers (International Cocoa Initiative, 2019; Sadhu et al., 2020). Smallholder cocoa farmers disagree with the Western-centered concept of child labor and have no intention to alter their way of life and farming practices, considering their socio-cultural norms and values. Nevertheless, given the objectives and risks associated with the LkSG, it can be seen as cultural imperialism as it interferes with the farmers' way of life and their socio-cultural norms and values, without asking them. The smallholder cocoa farmers are unwilling to accept this Westernization in their socio-cultural norms and values.

4.2.2 Worst form of child labor (§ 2 para. 2 no. 2 LkSG)

§ 2 para. 2 LkSG classifies the Worst Form of Child Labor (WFCL) risk into four categories: Category (a) encompasses forced labor, (b) includes prostitution and pornography, (c) covers illicit activities such as related to drugs, while category (d) involves work that harms the health, safety, or morals of children. The first category (a) and the last category (d) are particularly relevant risks for farmers, especially for their children (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021).

In a prominent case in 2005, six former child laborers filed individual lawsuits against Nestlé and Cargill under the Alien Tort Claims Act, because they were enticed from Mali and coerced to work on cocoa farms in Côte d'Ivoire under dire conditions (Collingsworth, 2020; BBC, 2021). Since that case, more than two decades have passed. However, there are still instances of children being subjected to forced labor on cocoa farms, albeit on a more localized and limited scale (Buhr and Gordon, 2018; Perkiss et al., 2021). According to the study conducted by Buhr and Gordon (2018), they estimated that the percentage of children in forced labor in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire is < 0.20%.

As described in Section 4.2.1, the socio-cultural norms and values are crucial. Smallholder cocoa farmers prioritize their children's well-being and future, with no intention of causing harm to them (Adonteng-Kissi, 2018; Babo, 2019). The study by Babo (2019) indicates parents' awareness of farm activities posing risks to children, restricting their involvement in hazardous tasks like using cutlasses until the parents consider that they can use them without hurting themselves. During this period, children observe and learn from the elders on the cocoa farm (Babo, 2019).

According to the Ghanaian and Ivorian governments, hazardous work for children under 18 is, e.g., spraying insecticides, breaking cocoa pods with a cutlass, or carrying heavy loads (Ministère de la Fonction publique et de l'Emploi, Côte d'Ivoire, 2005; Republic of Ghana Ministry of Manpower Youth and Employment, 2018). Furthermore, both governments have agreed to the Harkin-Engel Protocol and the ILO Convention No. 182 to eliminate WFCL (International Labour Organization, 2011, 2023a,d). This indicates that the governments recognize WFCL in their countries and aim to eliminate it (Ministère de la Fonction publique et de l'Emploi, Côte d'Ivoire, 2005; Republic of Ghana Ministry of Manpower Youth and Employment, 2018). However, according to the study by Sadhu et al. (2020), about 55 and 47% of children in agricultural households in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire, respectively, are affected by hazardous work on cocoa farms (Sadhu et al., 2020). Despite parents' awareness of hazardous child labor, many children are engaged in such activities, making it a significant risk. The authors identified that injuries sustained by children involved in hazardous work on cocoa farms in both countries primarily occur in the form of wounds/cuts (35%) and skin scratches/itching (8%) (Sadhu et al., 2020). Nonetheless, there is a lack of research that quantifies the actual number of children sustaining accidents or injuries due to hazardous labor.

Similar to Child Labor under 15 Years the LkSG acts as cultural imperialism by seeking to impose the Western perspective on WFCL among smallholder cocoa farmers. Except for the extreme case in Côte d'Ivoire, WFCL mainly involves hazardous tasks performed by physically capable children under parental supervision on cocoa farms. While farmers perceive no issues, the LkSG seeks to intervene by addressing and eliminating this risk.

4.2.3 Employment in forced labor (§ 2 para. 2 no. 3 LkSG)

In this section, we focus solely on adults in forced labor, as the issues of children in forced labor fall under the category of WFCL, as discussed in the previous section.

Forced labor is categorized as work performed involuntarily and under the threat of penalties. It includes situations where individuals are compelled to work through violence, intimidation, or coercive tactics (International Labour Organization, 2024). In Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana, there are existing cases of forced labor among adults on cocoa farms (Feasley, 2016; Buhr and Gordon, 2018). This issue affects not only local people but also migrants from neighboring countries. However, the risk is particularly high in Cote d'Ivoire, where migrants from neighboring countries such as Burkina Faso or Mali are coerced and forced to work on cocoa farms (Buhr and Gordon, 2018; Hütz-Adams, 2021). Despite this, both countries have ratified the ILO forced labor convention (International Labour Organization, 2024). According to the study by Buhr and Gordon (2018), an estimated 0.33% of adult workers in Ghana and 0.42% of adult workers in Côte d'Ivoire were subjected to forced labor between 2013 and 2017. The study focused on medium- and high-production areas, excluding low-production areas and illegal farms (Buhr and Gordon, 2018). These findings align with Lebaron's research (LeBaron, 2021), emphasizing the difficulty of isolating forced labor as workers often shift between forced labor and less severe forms of abuse within short periods (LeBaron, 2021). With regard to the LkSG, it is crucial to acknowledge that this problem poses a human rights risk in both countries, even though measuring its extent remains challenging (Buhr and Gordon, 2018).

4.2.4 Occupational safety and health obligations (§ 2 para. 2 no. 5 LkSG)

Cocoa farming poses health risks through the use of sharp tools, carrying heavy loads, spraying agrochemicals, or working in extreme weather conditions, as well as the possibility of being bitten by poisonous animals (Bosompem and Mensah, 2012; Muilerman, 2013; Olaleye, 2017). The study of Bosompem and Mensah (2012) indicates that injuries primarily from cutlasses, stump/thorn, and ant bites, are common. Furthermore, smallholder cocoa farmers suffer from back and waist pains during the harvest season or headaches from agrochemical inhalation (Bosompem and Mensah, 2012). Injuries can take up to 15 days a year when the farmer cannot work, leading to a yearly monetary loss (medical treatment and absent days) of about 17% of their annual revenue (Bosompem and Mensah, 2012; Muilerman, 2013).

Smallholder cocoa farmers, though willing to protect themselves, face challenges. Essential personal protection equipment like Wellington boots, overalls, or gloves is often unaffordable due to financial lack. Additionally, the unavailability of such equipment in local areas necessitates long-distance travel for purchase. Some farmers also encounter issues with size availability, leading to discomfort, such as wearing incorrectly sized Wellington boots or overalls for long distances in the sun (Muilerman, 2013; Osei-Owusu and Owusu-Achiaw, 2020).

Occupational safety and health obligations for smallholder cocoa farmers in both countries are currently lacking. However, it is worth noting that Ghana has ratified the ILO Safety and Health in Agriculture Convention, indicating some recognition of the importance of safety and health in agricultural practices (International Labour Organization, 2023c). Despite the significance of safety and health for smallholder cocoa farmers, financial constraints prevent most from affording personal protection equipment that could help mitigate these risks and injuries (Bosompem and Mensah, 2012; Muilerman, 2013; Osei-Owusu and Owusu-Achiaw, 2020). This risk addressed in the LkSG benefits cocoa farmers and can significantly contribute to improving occupational safety in cocoa farmers' working lives.

4.2.5 Withholding an adequate living wage (§ 2 para. 2 no. 8 LkSG)

This aspect of the LkSG aims to ensure that employees are paid remuneration to have a decent living for themselves and their families (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021; Johann and Gabriel, 2023). The LkSG states that fair payment is at least the applicable minimum wage (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021). However, a minimum wage does not always lead to a decent living, so fair remuneration can also be above the minimum wage to enable an adequate living (Johann and Gabriel, 2023). Widespread poverty persists among smallholder cocoa families, as their very low income prevents them from achieving a decent standard of living (Busquet et al., 2021; van Vliet et al., 2021; Fountain and Huetz-Adams, 2022).

The majority of smallholder cocoa farmers in Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana work as self-employed individuals, implying that they do not receive any form of remuneration. The farmer's remuneration is essentially the profit from selling cocoa sacks to middlemen at government-fixed prices. Few smallholder cocoa farmers can afford occasional labor assistance, typically for specific tasks, and no formal contracts exist. Working conditions for employed individuals are non-transparent, relying on oral agreements without considerations like a minimum wage, making tracking of working conditions difficult (Meemken et al., 2019; Amfo et al., 2021; Fountain and Huetz-Adams, 2022). It is crucial to highlight that Côte d'Ivoire has signed the ILO convention for a minimum wage in agriculture, whereas Ghana has not signed it (International Labour Organization, 2023b). In Ghana, the minimum wage is about 1.16 Euros per day per person, and that in Côte d'Ivoire is about 3.81 Euros a day per person (WageIndicator Foundation, 2023a,b). A smallholder cocoa family receives a total average annual revenue of about 600 Euros. Considering the additional expenses such as those from purchasing fertilizers and other farming equipment, the farmers in both countries earn below their local minimum wage. Thus, smallholder cocoa farmers can only meet the country's minimum wage and obtain a so-called living income or decent living, if the cocoa price is raised significantly (Fountain and Huetz-Adams, 2019, 2022; van Vliet et al., 2021). Overall, this risk is a daily challenge for smallholder cocoa farmers, even though they are self-employed they can only depend on the cocoa price set by their governments.

4.2.6 Remarks on the relevant risks from the perspective of smallholder cocoa farmers

About 15% of the addressed risks in the LkSG are significant issues for smallholder cocoa farmers and have a major effect on their well-being. The identified risks, which are existing issues for cocoa farmers are the following: (1) forced labor, (2) withholding adequate living wage, and (3) occupational safety and health obligations. Child labor and WFCL are omitted, as they are not perceived as issues from the perspective of the smallholder cocoa farmers due to their socio-cultural norms and values. In this regard, the LkSG would also interfere with the farmer's socio-cultural norms and values for some of the addressed risks in the LkSG, thereby enforcing cultural imperialism. Therefore, we emphasize considering the socio-cultural norms of Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire when analyzing human rights, avoiding a solely Western perspective, and refraining from imposing European standards. Smallholder cocoa farmers and their families generally do not face major or common issues related to the other specific definitions of human rights risks in the LkSG, such as forms of slavery, violation of freedom of association, and use of private or public security forces to protect enterprise projects. Although the environmental risks addressed in the LkSG have no relevance to smallholder cocoa farmers, two significant environmental risks are entirely not covered by the law. The first is deforestation. Ghana has lost about 65% of its forest area and Côte d'Ivoire about 90% in the last 30 years, where cocoa production is the primary driver (The World Bank, 2020; European Commission, 2021; Ashiagbor et al., 2022). The second risk is the high usage of agrochemicals and pesticides in cocoa production (Fountain and Huetz-Adams, 2022). However, as a result, when considering only the identified relevant addressed risks, the LkSG can have positive impacts, especially in terms of occupational safety and health obligations, adequate living wages, and forced labor.

4.3 Procedural implications of the LkSG for affected companies in Germany

In this section, we aim to shed light on the procedural effects of the LkSG on the companies from the perspective of smallholder cocoa farmers. Therefore, we systematically assess the entire due diligence process, that the LkSG requires from the affected companies.

4.3.1 Risk management and risk analysis

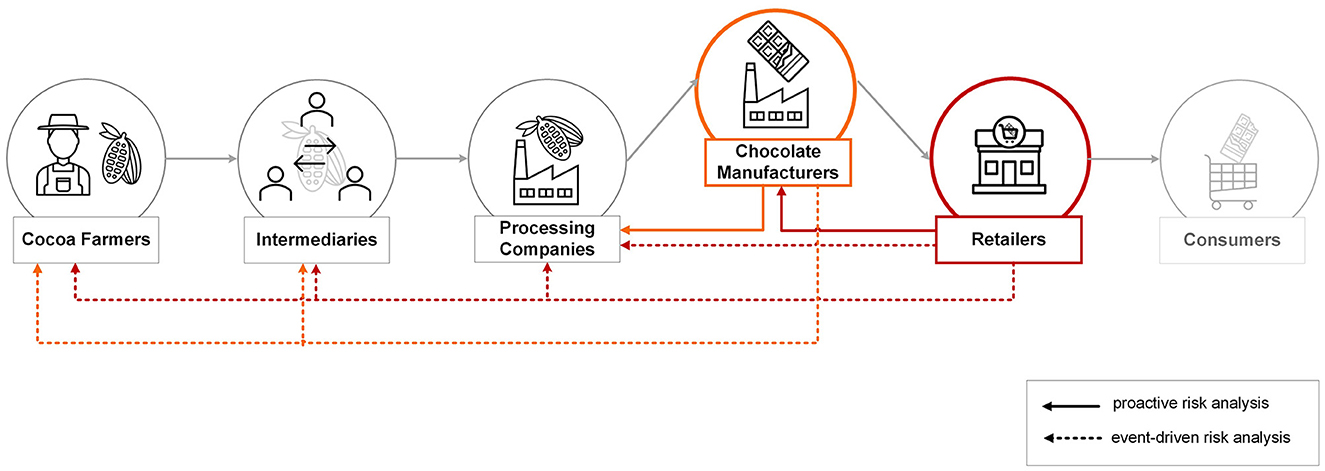

All chocolate manufacturers and retailers in Germany that are required to comply with the LkSG must primarily implement risk management for their business unit and its tier-1 suppliers to comply with the due diligence obligations (see Figure 3). The risk management must be effective and appropriate and needs to be monitored by a human rights officer of the company (§ 4 LkSG).

Figure 3. Proactive and event-driven analysis based on the own business unit of retailers and chocolate manufacturers along the generalized supply chain. Proactive risk analysis, denoted by a solid arrow, is mandatory and must be conducted at least once a year for the own business unit and tier-1 suppliers, while event-driven risk analysis of tier-n suppliers, indicated by a dashed arrow, needs to be conducted by substantiated knowledge only.

As part of risk management, it is necessary to carry out an adequate risk analysis to identify human rights and environmental-related risks within the company's business unit and its tier-1 suppliers (§ 5 LkSG). The risk analysis must be performed annually and occasionally, such as a change in the risk landscape within the supply chain (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021). However, the LkSG does not provide a specific method for conducting the risk analysis, leaving it up to the company to choose an appropriate approach (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021; Lorenz and Krülls, 2023). Initially, the annual risk analysis does not significantly affect cocoa farmers, as only the company's own business unit and tier-1 suppliers need to be considered (see Figure 3).

Looking at the supply chain of chocolate manufacturers in Germany (see Figure 3), they procure their processed cocoa, such as cocoa butter or liquor, from processing companies primarily located in Europe as pointed out in Section 3.2. Likewise, the chocolate manufacturers of retailers are based in Europe. Smallholder cocoa farmers, who are tier-n suppliers for companies in Germany are not covered by the LkSG because affected companies are not required to conduct a proactive risk analysis of them. A risk analysis must only be carried out for cocoa farmers if the company has substantiated knowledge (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021). Affected chocolate manufacturers in Germany can obtain substantiated knowledge about risks or violations of human rights in cocoa production through, e.g., the complaints procedure, media reports, or NGOs (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021; Andersen et al., 2022; Fountain and Huetz-Adams, 2022). Consequently, an event-driven risk analysis must be conducted. As a result, this leads to implementing preventive measures and actions to mitigate or eliminate the identified risks in cocoa production (see Section 4.3.2). However, this reveals a weakness of the LkSG—the exclusion of tier-2 and beyond suppliers. Excluding tier-n suppliers from proactive risk analysis is a main criticism of the LkSG. Former UN Secretary-General John G. Ruggie, in an open letter to the German Government, highlighted this omission and expressed concerns about the timing of substantiated knowledge, as conducting a risk analysis after a violation may be too late (Ruggie, 2021). For smallholder cocoa farmers, who are tier-n suppliers for affected companies in Germany, a risk analysis is only required if the retailer or chocolate manufacturer in Germany has substantiated knowledge of impending or existing harm (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021).

4.3.2 Preventive and corrective measures

Appropriate preventive measures must be taken if a company identifies risks within its annual or event-driven risk analysis (§ 6, § 9 LkSG). If identified risks have occurred or are imminent, the company must implement corrective actions immediately to prevent, cease, or minimize violations (§ 7 LkSG). The LkSG distinguishes between ending the violation within the company's business unit and tier-1 supplier. In the business unit, the prevention measure must effectively end the violation. For tier-1 suppliers, if the violation cannot be stopped immediately, the company must develop and implement a concept with a schedule to minimize or end the violation (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021). In case of substantiated knowledge regarding tier-n suppliers, besides the event-driven risk analysis, retailers or chocolate manufacturers need to implement prevention measures (§ 9 LkSG), which can be classified as an output. Furthermore, those companies must develop and implement a concept to prevent, end, or minimize the identified risks or violations. This can significantly affect smallholder cocoa farmers' well-being since the retailers and chocolate manufacturers are legally obligated to implement the respective preventive and remedial measures and review and document them accordingly. However, it should be noted that the LkSG establishes an obligation to make an effort but does not guarantee success or assume liability. It means that companies must demonstrate that they have implemented the due diligence requirements under the LkSG. Thus, they are not obliged to ensure they are entirely free from human rights violations or environmental issues (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021; Deutscher Bundestag, 2021; Bundesamt für Wirtschaft und Ausfuhrkontrolle, 2022; Walden, 2022). Moreover, the LkSG states that the action taken by a company depends on its potential influence on the direct cause of the risk or violation. The LkSG provides examples such as the size of the company, order volumes, or proximity to the risk (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021; Deutscher Bundestag, 2021; Walden, 2022). Falder et al. (2022) argue that undefined legal terms could be problematic, as it is unclear which action should be taken. They highlight this problem by clarifying that the size of a company or the order volume should not determine the actions to be taken in case of grave human rights violations (Falder et al., 2022).

As a part of the preventive measures, retailers and chocolate manufacturers must also provide a policy statement based on their risk analysis (§ 6 LkSG). However, this policy statement does not immediately affect smallholder cocoa farmers. In the long term, it could affect smallholder cocoa farmers, as those companies need to define their human rights strategy and set expectations for their business partners along their supply chain. Whether this policy statement is more of a formal matter or has positive effects is questionable, but in any case, it may raise awareness. Therefore, it is required that companies establish agreements regarding appropriate contractual control mechanisms to ensure that the immediate supplier complies with the human rights strategy (§ 6 LkSG).

4.3.3 Complaints procedure

In addition to risk analysis, companies must establish a complaints procedure (§ 8 LkSG), accessible to all individuals involved in the entire supply chain (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021; Kämpf, 2023). In principle, this is a simple but only possibility to enable smallholder cocoa farmers to file complaints to retailers and chocolate manufacturers in Germany with regard to their issues and risks identified in Section 4. Additionally, when a company receives an indication, it must investigate all reports and examine the reported issue. This can lead to an event-driven risk analysis of issues about smallholder cocoa farmers, eventually leading to a betterment of their situation. However, as most farmers are uneducated and have poor technology access (Kraft and Kellner, 2022), it becomes challenging for them to learn about a German company's complaints procedure. Submitting complaints, whether through phone calls (which may incur costs for the farmers), voice messages, or websites that might be in English rather than their local language, becomes challenging. Although the complaints procedure must be implemented without any access barriers, it might still be a barrier to smallholder cocoa farmers, raising the question of whether they are even interested in utilizing it. Therefore, the smallholder cocoa farmers would also need information regarding the supply chain to contact the relevant manufacturer or retailer in Germany.

4.3.4 Annual report

The affected companies must document all their actions regarding the required due diligence and publish annually a report regarding their fulfillment of the due diligence (§ 10 LkSG), which will be reviewed by the German authority (Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control). In a broader sense, this due diligence will not directly affect smallholder cocoa farmers. Nevertheless, documentation and monitoring will show effects, leading companies to take seriously their due diligence obligations according to the LkSG.

4.3.5 Remarks on the procedural implications

The procedural implication of the LkSG can have a positive impact on smallholder cocoa farmers. Particularly, the complaint procedure and the event-driven analysis associated with it could have a positive effect on smallholder cocoa farmers, as companies are legally required to address the issues and initiate preventive measures (output), annually reviewed by the German authority. However, these effects may not be immediately noticeable to smallholder cocoa farmers, as the LkSG emphasizes the obligation to make an effort but not guarantee results. At the same time, they could justify their limited actions based on their influence over smallholder cocoa farmers as defined by the LkSG (§ 3 LkSG). The question then arises: suppose the big players in the chocolate industry such as Mars Wrigley, Ferrero Group, and Mondelez International, with greater influence to implement proactive and corrective measures, would fulfill their due diligence obligations, will it lead to an improvement for smallholder cocoa farmers? The answer to this question can only be provided in the future after several years of the LkSG implementation have passed. At the latest, when the CSDDD comes into force, the due diligence obligations for companies will become more extensive (European Commission, 2022b).

4.4 The role of NGOs

In light of the challenges faced by smallholder cocoa farmers in lodging complaints, NGOs can play two major roles for them concerning the LkSG. Firstly, they can contribute substantial knowledge by reporting violations or risks through the complaint system of the respective chocolate manufacturer or retailer or directly to the German Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control. Alternatively, they can generate reports or studies regarding human rights violations or risks faced by smallholder cocoa farmers. As explained in the previous section (Section 4.3), substantiated knowledge triggers an event-driven risk analysis of the cocoa supply chain, which in turn guides corrective measures to be taken by the respective manufacturer or retailer under the LkSG.

Secondly, according to §11 LkSG, a special litigation status is possible in that the person concerned along the supply chain, in this case, the cocoa farmer, can authorize an NGO or trade union for legal action. This special legal standing applies exclusively to NGOs and trade unions based in Germany that are not commercially active and are not only temporarily committed to human rights (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021). This implies that a German NGO, for instance, can uphold the rights of smallholder cocoa farmers, potentially resulting in significant legal expenses and harm to the reputation of the chocolate manufacturer or retailer involved. Nevertheless, the violation of an overriding importance of the concerned smallholder cocoa farmer's protected legal position under § 2 para. 1 of the LkSG must be asserted; the concrete requirements for such assertion remain indeterminate even according to the legislative rationale (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021).

4.5 The role of media

Media is a powerful instrument and can have effects on the implications of the LkSG in two ways. Firstly, the media is crucial in creating awareness about human rights and environmental risks within supply chains for cocoa-containing products, particularly in Germany. Additionally, negative publicity regarding LkSG issues can adversely affect a company's reputation. This heightened awareness due to media can potentially influence the consumers' purchasing decisions. Consumer pressure is a main driver to push companies to more sustainable practices within their supply chains (Zhu and Sarkis, 2007; Sajjad et al., 2020; Hartmann, 2021). The consumers' awareness and pressure regarding human rights and environmental-related risks in the cocoa supply chain may shape the sourcing strategy of companies. Moreover, this might drive companies to initialize more LkSG-risk-free cocoa supply chains in the future, which will assist smallholder cocoa farmers in improving their situation in the long term.

Secondly, the media can play an important role in providing retailers and chocolate manufacturers in Germany with actual indicators of violations and risks within their cocoa supply chain, especially on cocoa farms. If this leads to a substantiated knowledge of those companies, they must conduct an event-driven risk analysis regarding smallholder cocoa farmers, as examined in Section 4.3 (Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2021; Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, 2023). In this regard, media attention could help smallholder cocoa farmers by potentially initiating a risk analysis for the retailer and chocolate manufacturers. Subsequently, preventive and corrective measures would need to be established depending on the identified risks to address existing violations and risks on cocoa farms. Therefore, the media can support smallholder cocoa farmers by generating awareness about their issues among consumers, retailers, and chocolate companies.

4.6 Remarks on the effects of the LkSG on smallholder cocoa farmers

The LkSG has the potential to incentivize chocolate manufacturers and retailers under the LkSG to reassess their cocoa supply chain, mitigating risks through supplier selection and development. This could instigate implications not only for German companies themselves but also for suppliers throughout the global supply chain. In addition to adjusting the sourcing strategy, worldwide suppliers may experience increased administrative requirements, as companies under the LkSG seek to ensure that their suppliers adhere to human rights compliance and pass this requirement down to their suppliers.

The LkSG's influence on awareness (outcome), driven by media attention and reputational concerns, can positively shape the entire company's cocoa supply chain in the long term. This influence can lead to increased vertical integration of chocolate manufacturers and retailers, addressing social and environmental risks, enhancing transparency, and striving for an LkSG-risk-free supply chain. Transparency, defined as a shared comprehension and accessibility to relevant information such as product information, transactions, or labor conditions, becomes crucial in achieving these goals. Achieving transparency requires providing complete, accurate, and relevant data based on the specific information needs of supply chain actors, ultimately allowing for a clear understanding of who delivered what to whom (Hofstede, 2003).

The trend toward vertical integration, already noticeable for social and environmental reasons, may intensify with the LkSG and forthcoming regulations (Orsdemir et al., 2019; Ritter Sport, 2020; Murcia et al., 2021). However, challenges may arise due to the special cocoa market structure and governmental regulation, especially in Ghana due to COCOBOD, limiting the benefits for smallholder cocoa farmers. In Côte d'Ivoire, potential advantages through vertical integration exist, since cocoa sacks can be directly purchased from smallholder cocoa farmers. Despite this, the LkSG's efficacy might encounter limitations.

German companies, aiming for an LkSG-risk-free supply chain, may drive demand for socially and environmentally responsible cocoa, impacting sustainable farming practices. This impact may be realized through outputs such as farmer training, better resource access, and fostering social and environment-friendly farming. Simultaneously, as an output, these requirements may raise national governments' awareness of human rights and labor practices, potentially leading to long-term (national) legislative changes worldwide (impact).

Despite potential effects, emerging negative outcomes include companies contemplating withdrawing from high-risk countries or changing their purchasing strategy by prioritizing only countries with very low human rights and environmental risks (Kolev and Neligan, 2022). The potential withdrawal of German companies from the African market as a response to LkSG, aiming to avoid serious consequences, may have adverse effects on nations characterized by elevated human rights and environmental risks. This scenario could be exacerbated by the entry of companies from countries with low human rights and environmental standards (Creutzburg and Schäfers, 2021; Schaefer, 2022; Vinke et al., 2023). The LkSG, despite challenges, represents a step in the right direction. Companies in Germany, sensitized to ethical concerns, are preparing for upcoming regulations, offering potential advantages for the entire cocoa supply chain.

This study presents some limitations which provide opportunities for future research. Our literature review, though extensive, was limited to the literature that was accessible. Given that the LkSG is relatively new, forthcoming literature is anticipated to offer more pertinent insights. While our review was conducted from a desktop perspective, it provides a solid foundation for future field studies that could offer a more current representation of the situation on the ground. Based on these limitations, we recommend that future works should consider an empirical study to analyze the implications of LkSG on smallholder cocoa farmers' human rights. Additionally, future research could investigate how the LKSG influences upstream and downstream actors in the global cocoa supply chain.

5 Conclusion and recommendation

A critical look at the cocoa supply chain in this study has revealed that human rights violations and environmental damages are not rampant in Europe, but rather at the beginning of the cocoa supply chain, specifically in Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana, where most of the world's cocoa is produced (Sadhu et al., 2020; Hütz-Adams, 2021).

The LkSG, a new law in Germany, has attracted considerable research attention, which tends to be argued from the perspective of Germany or Europe (Gehling et al., 2021; Berger, 2022; Koos, 2022; Johann et al., 2023; Lorenz and Krülls, 2023). Given that the purpose of the LkSG is to improve the protection of human rights and the environment, it is also crucial to examine the LkSG from the perspective of individuals and countries where human rights and environmental risks persist. Few studies show the potential effects of the LkSG in developing countries, without thorough analysis (Felbermayr et al., 2022; Kolev and Neligan, 2022). In addressing this gap in the literature, our contribution lies in analyzing the LkSG from the perspective of the cocoa smallholder farmers in West Africa and the potential implications the LkSG could have on them. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first thorough analysis and marks an initial investigation in this research area.

Due to its limitations, the LkSG may not lead to remarkable improvements for smallholder cocoa farmers and their families in the short and mid-term. This limitation arises because the LkSG primarily focuses on the affected retailers, chocolate manufacturers' business units, and tier-1 suppliers, which are mainly located in Europe. Since smallholder cocoa farmers are typically not considered tier-1 suppliers to either chocolate manufacturers or retailers in Germany due to their upstream position within a multi-echelon supply chain, they are not included in their proactive risk management, which must be conducted yearly. However, in the long term, the LkSG could positively impact smallholder cocoa farmers, as it may lead to increased awareness (outcome). This, in turn, is likely to affect the supply chain strategy of manufacturers and retailers in Germany, which might result in a positive impact on smallholder cocoa farmers. The results of this study, the effects of the LkSG on smallholder cocoa farmers may to some extent, apply to other farmers or workers in developing countries engaged in raw material production or extraction. This is because, given the complexity of supply chains, the first actors typically do not operate as tier-1 suppliers to companies in Germany and therefore are not the primary focus of the LkSG.

Overall the LkSG fails to achieve its goal of improving human rights and environmental protection by not directly including actors such as the cocoa farmers in high-risk countries, as these are usually not tier-1 suppliers to affected companies in Germany. However, the upcoming CSDDD is designed to be more stringent. For example, due diligence obligations not only apply to the company's own business unit and the tier-1 suppliers but also to the upstream and downstream value chain. Consequently, affected chocolate manufacturers and retailers in Europe would need to consider cocoa farmers, e.g., in their risk analysis which would lead to positive implications. Furthermore, affected companies could be held liable under civil law with the possibility of claims for damages being pursued, for instance (European Commission, 2022b). All in all, we recommend German companies to develop suppliers in Africa through training and provision of necessary resources. This way, African suppliers can align with the requirements of German or European companies which are affected by the LkSG and in the future of the CSDDD.

This paper solely analyzed the perspective of smallholder cocoa farmers, neglecting other viewpoints like those of intermediaries in West Africa, chocolate manufacturers, or retailers. We recommend further research to explore these other perspectives, specifically focusing on how the LkSG influences companies' sourcing strategies and the challenges they encounter in ensuring due diligence according to the LkSG. Cocoa is one example of numerous commodities cultivated in environments plagued by human rights abuses or environmental hazards. Other commodities like Mica in India and Cobalt in the Republic of Congo, also carry substantial risks in their supply chains (Franke, 2022; Hynes, 2022; Mayer, 2022). Therefore, we suggest additional surveys into the supply chains of other commodities, to gain a deeper understanding of the scope and effects of the LkSG and to determine whether its limited effect is influenced by the unique structural characteristics of the cocoa market in West Africa or if it can be generalized. Furthermore, our research does not consider the possible implications on the economy in West Africa resulting from the withdrawal of operations due to the LkSG implementation. Therefore, we recommend further analysis in this regard. Additionally, investigating any changes in companies' strategies and the extent to which vertical integration has increased to establish secure LkSG-risk-free supply chains would be valuable. Moreover, we highlight conducted studies in possible technology solutions, such as blockchain technology, where all the LkSG risks can be tracked to enhance full transparency in the cocoa supply chain.

In summary, while the LkSG is designed to enhance human rights and environmental conditions throughout supply chains, our research does not indicate any significant short- to mid-term positive implications for smallholder cocoa farmers. However, the law potentially leads to beneficial impacts for these farmers in the long run. Furthermore, our study suggests that the heightened awareness brought about by the law could ultimately shape supply chain strategies to the advantage of smallholder cocoa farmers in West Africa.

Author contributions

SK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MQ: Writing – review & editing. FK: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

CCC, Conseil du Café-Cacao; COCOBOD, Ghana Cocoa Board; CSDDD, Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive; HRDD, Human Rights Due Diligence; ILO, International Labour Organization; LBC, Licensed Buying Company; LID, Living Income Differential; LkSG, Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz; NGO, Non-Governmental Organisation; WFCL, Worst Form of Child Labor.

Footnotes

1. ^In terms of their employee numbers in Germany, Ferrero will be subject to the LkSG from 2023, and Mars from 2024 (Ferrero Deutschland GmbH, 2023; Mars Incorporated, 2023). The number of employees within Germany at Alfred Ritter is unclear, as only the worldwide number of employees is known (Alfred Ritter GmbH & Co. KG, 2021).

References

Abdullah, A., Huynh, I., Emery, C. R., and Jordan, L. P. (2022). Social norms and family child labor: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:4082. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19074082

Adebayo, O., Olagunju, K. O., and Ogundipe, A. A. (2016). Impact of agricultural innovation on improved livelihood and productivity outcomes among smallholder farmers in rural nigeria. SSRN Electron. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2847537

Adonteng-Kissi, O. (2018). Causes of child labour: perceptions of rural and urban parents in ghana. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 91, 55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.05.034

Adonteng-Kissi, O. (2021). Child labour versus realising children's right to provision, protection, and participation in ghana. Aust. Soc. Work 74, 464–479. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2020.1742363

Alfred Ritter GmbH & Co. KG (2021). Ritter Sport auf einem Blick: Die wichtigsten Daten des Familienunternehmens. Available online at: https://www.ritter-sport.com/auf-einen-blick (accessed July 18, 2023).

Amfo, B., Aidoo, R., and Osei Mensah, J. (2021). Food coping strategies among migrant labourers on cocoa farms in southern ghana. Food Sec. 13, 875–894. doi: 10.1007/s12571-021-01186-4

Andersen, L. E., Medinaceli, A., Gonzales, A., Anker, R., and Anker, M. (2022). Living Wage Update Report Peri-Urban Lower Volta Region. Global Living Wage Coalition.

Annandale, D. (2001). Developing and evaluating environmental impact assessment systems for small developing countries. Impact Assess. Project Appr. 19, 187–193. doi: 10.3152/147154601781766998

Ashiagbor, G., Asante, W. A., Forkuo, E. K., Acheampong, E., and Foli, E. (2022). Monitoring cocoa-driven deforestation: the contexts of encroachment and land use policy implications for deforestation free cocoa supply chains in ghana. Appl. Geograp. 147:102788. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2022.102788

Babo, A. (2014). Child labor in cocoa-growing communities in cote d'ivoire: Ways to implement internatinal standards in local communities. UC Davis J. Int. Law Policy 21, 23–41.

Babo, A. (2019). “Eliminating child labour in rural areas: limits of community-based approaches in south-western côte d'ivoire,” in Child Exploitation in the Global South, eds J. Ballet, and A. Bhukuth (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 65–90.

Bai, C., Quayson, M., and Sarkis, J. (2021). Covid-19 pandemic digitization lessons for sustainable development of micro-and small- enterprises. Sustain. Prod. Consumpt. 27, 1989–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2021.04.035

Barnett, M. L., Henriques, I., and Husted, B. W. (2020). Beyond good intentions: designing csr initiatives for greater social impact. J. Manage. 46, 937–964. doi: 10.1177/0149206319900539

Bary Callebaut, A. G. (2023). Barry Callebaut auf einem Blick. Available online at: https://www.barry-callebaut.com/en/group/about-us/barry-callebaut-glance-german (accessed June 8, 2023).

Bäumler, J. (2022). Germany's supply chain due diligence act: Is it compatible with wto obligations? Zeitschrift Europarechtliche Stud. 25, 265–286. doi: 10.5771/1435-439X-2022-2-265

BBC (2021). US Supreme Court Blocks Child Slavery Lawsuit Against Chocolate Firms. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-57522186 (accessed July 14, 2023).

Berger, L. (2022). Lieferkettenverantwortung aus Unternehmens- und Beratersicht: Notwendigkeit oder Überforderung? Zeitschrift Unternehmens Gesellschaftsrecht 51, 607–622. doi: 10.1515/zgr-2022-0026

Bosompem, M., and Mensah, E. (2012). Occupational hazards among cocoa farmers in the Birim South District in the Eastern Region of Ghana. ARPN J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 7, 1055–1061.

Boysen, O., Ferrari, E., Nechifor, V., and Tillie, P. (2023). Earn a living? What the côte d'ivoire-ghana cocoa living income differential might deliver on its promise. Food Policy 114:102389. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102389

Buhr, E., and Gordon, E. (2018). Bitter Sweets: Prevalence of Forced Labour & Child Labour in the Cocoa Sectors of côte d'ivoire & Ghana. Available online at: https://www.cocoainitiative.org/sites/default/files/resources/Cocoa-Report_181004_V15-FNL_digital_0.pdf (accessed July 13, 2023).

Bundesamt für Wirtschaft und Ausfuhrkontrolle (2022). Angemessenheit: Handreichung zum Prinzip der Angemessenheit nach den Vorgaben des Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetzes. Available online at: https://www.bafa.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Lieferketten/handreichung_angemessenheit.html;jsessionid=0104B23287701BBD2BA0A0594601347E.internet281?nn=1469820 (accessed June 5, 2023).

Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales (2023). Fragen und Antworten zum Lieferkettengesetz. Available online at: https://www.csr-in-deutschland.de/DE/Wirtschaft-Menschenrechte/Gesetz-ueber-die-unternehmerischen-Sorgfaltspflichten-in-Lieferketten/FAQ/faq.htm (accessed September 16, 2023).

Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (2021). Das Lieferkettengesetz. Available online at: https://www.bmz.de/de/themen/lieferkettengesetz (accessed October 27, 2022).

Bundesrepublik Deutschland (2021). Gesetz über die unternehmerischen Sorgfaltspflichten in Lieferketten. Berlin: LkSG.

Bundesverband der Deutschen Süßwarenindustrie e.V. (2021). Wie wichtig ist Ihnen beim Kauf von Süßwaren Nachhaltigkeit? Available online at: https://www.bdsi.de/fileadmin/redaktion/Grafik___Statistik/BDSI_Nachhaltigkeit_300dpi.jpg(accessed May 29, 2023).

Busquet, M., Bosma, N., and Hummels, H. (2021). A multidimensional perspective on child labor in the value chain: the case of the cocoa value chain in west africa. World Dev. 146:105601. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105601

Cargill Incorporated (2022). What Matters Most: 2022 Annual Report. Available online at: https://www.cargill.com/doc/1432215917376/2022-cargill-annual-report.pdf (accessed June 8, 2023).

Carini, C., Rocca, L., Veneziani, M., and Teodori, C. (2018). Ex-ante impact assessment of sustainability information-the directive 2014/95. Sustainability 10:560. doi: 10.3390/su10020560

Cocoa Marketing Company (GH) LTD (2022). Core Operations. Available online at: https://www.cocoamarketing.com.gh/cmcgh/about/core_operations (accessed December 29, 2022).

COCOBOD (2022). Cocoa Marketing Company. Available online at: https://cocobod.gh/subsidiaries-and-divisions/cocoa-marketing-company (accessed December 29, 2022).

COCOBOD (2023). Cocoa. Available online at: https://cocobod.gh/pages/cocoa (accessed July 11, 2023).

Collingsworth, T. (2020). Nestlé & cargill v. Doe Series: Meet the “john does”-the Children Enslaved in Nestlé & Cargill's Supply Chain—Just Security. Available online at: https://www.justsecurity.org/73959/nestle-cargill-v-doe-series-meet-the-john-does-the-children-enslaved-in-nestle-cargills-supply-chain/ (accessed July 14, 2023).

Cote D'Ivoire-Ghana Cocoa Initiative (2021). Who We Are. Available online at: https://www.cighci.org/about-us/ (accessed December 29, 2022).

Creutzburg, D., and Schäfers, M. (2021). Millionenbußen drohen. Frankfurt am Main: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 16.

Deutscher Bundestag (2021). Gesetzentwurf der Bundesregierung. Entwurf eines Gesetzes über die unternehmerischen Sorgfaltspflichten in Lieferketten. Berlin.

Dovbischuk, I. (2021). Investigating the interplays between supplier relationship management and the german supply chain act for better sustainability in global value chains. Int. J. Manag. Appl. Sci. 7, 28–32.

Ebrahim, A., and Rangan, V. K. (2014). What impact? A framework for measuring the scale and scope of social performance. Calif. Manag. Rev. 56, 118–141. doi: 10.1525/cmr.2014.56.3.118

European Commission (2016). Handbook for Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment: 2nd Edn. Available online at: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/8b3a2b37-1028-11e6-ba9a-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed September 22, 2023).

European Commission (2021). Ending Child Labour and prOmoting Sustainable Cocoa Production in Cote D'ivoire and Ghana: Final Report. Available online at: https://www.kakaoforum.de/fileadmin/Redaktion/Studien/Ending_child_labour_and_promoting_sustainable_cocoa_production_in_Co__te_dIvoire_and_Ghana_Report_FINAL.pdf (accessed January 5, 2023).

European Commission (2022a). Guidelines on the Analysis of Human Rights Impacts in Impact Assessments for Trade-Related Policy Initiatives. Available online at: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/7fc51410-46a1-4871-8979-20cce8df0896/library/991d8e1d-dbaa-49d6-8582-bb3aab2cab48/details (accessed September 22, 2023).

European Commission (2022b). Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence and Amending Directive (eu) 2019/1937. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022PC0071 (accessed May 2, 2023).

European Commission (2023). Better Regulation: Toolbox. Available online at: https://commission.europa.eu/law/law-making-process/planning-and-proposing-law/better-regulation/better-regulation-guidelines-and-toolbox_en (accessed October 4, 2023).

Falder, R., Frank-Fahle, C., and Poleacov, P, . (eds). (2022). Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

Feasley, A. (2016). Eliminating corporate exploitation: examining accountability regimes as means to eradicate forced labor from supply chains. J. Hum. Traff. 2, 15–31. doi: 10.1080/23322705.2016.1137194

Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (2021). More Fairness in Global Supply Chains-Germany Leads The Way. Available online at: https://www.bmz.de/en/issues/supply-chains (accessed June 15, 2023).

Felbermayr, G., Herrmann, C., Langhammer, R. J., Sandkamp, A.-N., and Trapp, P. (2022). Ökonomische Bewertung eines Lieferkettengesetzes, volume Nr. 42 (Juli 2022) of Kieler Beiträge zur Wirtschaftspolitik. Kiel: Kiel Institut für Weltwirtschaft—Leibniz Zentrum zur Erforschung globaler ökonomischer Herausforderungen.

Ferrero Deutschland GmbH (2023). Menschen bei ferrero: Verantwortung gegenüber Mitarbeitern und Partnern. Available online at: https://www.ferrero.de/mitarbeiter (accessed July 18, 2023).

Fountain, A. C., and Huetz-Adams, F. (2015). Kakao-Barometer 2015. Available online at: https://suedwind-institut.de/files/Suedwind/Publikationen/2015/2015-16%20Kakaobarometer%202015_Deutsch.pdf (accessed March 14, 2023).

Fountain, A. C., and Huetz-Adams, F. (2019). Necessary Farm Gate Prices for a Living Income. Available online at: https://voicenetwork.cc/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/200113-Necessary-Farm-Gate-Prices-for-a-Living-Income-Definitive.pdf (accessed March 30, 2023).

Fountain, A. C., and Huetz-Adams, F. (2022). Cocoa barometer 2022. Available online at: https://cocoabarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Cocoa-Barometer-2022.pdf (accessed December 29, 2022).

Franke, M. (2022). Kobalt aus Kongo: Die dunkle Seite der Verkehrswende. Frankfurt am Main: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.