- 1Leiden University College, Faculty of Governance and Global Affairs, Leiden University, The Hague, Netherlands

- 2Faculty of Humanities, Institute for Area Studies, Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands

Transformation opens possibilities to imagine and learn other forms of being and living together; it implies change, and often exchange. This paper visibilises the infrastructural stories involved in the transformation of food waste into edible food. Conceptually, we assume there is no univocal definition of food waste. Methodologically, we resist the practice of extracting and appropriating the life (hi)stories of the people involved in these transformative initiatives who are often described as vulnerable “others.” Instead, the project highlights the stories of the infrastructures underpinning these transformative experiences. The objective is to unsettle the frontier of what counts as food waste by paying attention to the objects involved in the process of transforming it into edible food. The paper starts by positioning ourselves in the literature regarding food waste governance and infrastructural labor as transformative possibilities that support the development of personal sustainability strategies and grassroots food governance. In the second section we explain our methodological considerations to focus on the infrastructures that mediate the transformation of disposed food into edible food in The Hague. The third section presents the results and discusses the stories of two objects, a cargo bike (bakfiets) and a fridge (koelkast). We suggest these objects serve to unsettle governance practices and narratives related to food waste in the city. Paying attention to these objects’ stories is an important turn in personal sustainability research because it enables us to see that the individual is never alone, always acting with the support of often invisible objects that in this study make possible the reduction and transformation of wasted food. This serves as inspiration to imagine alternative paths for food waste governance and foster forms of collective engagement, urgently needed given the increasing precariousness of food systems and relations.

Introduction

In the social sciences and the humanities, food waste has been explored by studying the practices, rituals, structures, politics, policies, relations, and institutions that underline it. The plurality of disciplinary perspectives involved in food waste studies illuminates the multiplicity and variety of actors involved in the prosaic practice of disposing food. The interest and visibility of food waste studies intensified in the 21st century as the result of the global food crisis in 2007, policy shifts in the EU and US, activist politics in academia as well as technological and environmental changes (Evans et al., 2013).

As an often-invisible companion to individual daily routines, food waste is also an important part of a massive global sustainability problem: globally about one third of all food produced is wasted if one adds the wasted food at harvest and retail (14% according to FAO, 2019) and at retail and consumer levels (17% according to UNEP, 2021). At the same time, across the world societies are experiencing increasing food prices, and more and more people are affected by food insecurity. In the Netherlands, Dutch households have been steadily reducing their food waste in the last decade, but the problem is far from being a minor one. In 2019 consumers were responsible for about 42% of the total food waste in the country, a total of 5 million kilograms worth an estimated 13 million euros (Sheldon, 2021). Simultaneously, about 25% of residents in low-income neighborhoods in the Netherlands are food insecure (Janssen et al., 2022). Abiding to the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals), the government of the Netherlands plans to cut food waste in half by 2030 (compared to the 2015 situation, Stichting Samen Tegen Voedselverspilling, 2023) and end hunger. While consumption practices can lead to food waste, Stuart argues that food waste is a matter of law and governance, as it is to a large degree created by existing rules and policies regarding food access and provisioning, and a lack of responsible policies in relation to waste (Stuart, 2009). In this context, critically exploring the elusive governance of food waste becomes highly relevant, especially when paired with addressing food insecurity. This paper makes visible the stories of two objects, a cargo bike (bakfiets) and a fridge (koelkast), and how they connect to debates about food waste management, and collective action to tackle food insecurity in the city. We suggest that paying attention to these objects, and all the others that support food relations, can offer new ways of thinking about food waste governance, unsettling the frontiers of what counts as waste, what counts as food, and the mutual entanglements between both.

Literature review

In recent years the literature is recognizing the dynamic qualities of waste and the extent to which its impact (economic, social, and environmental) depends on its spatio-temporal context (Evans et al., 2013). Work by scholars such as Gay Hawkins (2006) and Gille (2010) have contributed to this paradigm shift. While Hawkins (2006) work centers on recognizing the cultural elements embedded in waste practices, Gille (2010) explores the formation of “waste regimes,” that is when institutions and social conventions shape the value of what counts as waste, which in turn defines, manages, and politicizes waste governance policies. The concept of “waste regime” allows us to understand “the economic, social, and cultural origins of specific wastes as well as the logic of their generation” Gille (2010, p. 1,056). Other relevant approaches are what Moore (2012) describes as waste geographies, namely how waste flows and moves between people and places. This makes visible what Gidwani (2015) describes as the associated role of invisible labor involved in managing and dealing with waste.

In waste studies, food waste belongs to the category of avoidable waste. According to Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), disposed food still has value and is very often fit for consumption. Food waste is food that is spilled, spoiled, bruised, or wilted; it may include whole or unopened packages or individual items of food which are not eaten at all (FAO, 2019). It is foreseeable that in the coming years, food waste will continue to grow, which makes it a salient environmental and socio-economic problem. For the EU, waste prevention has become a priority of the Farm to Fork Strategy.1 However, they have not managed to align member states to adopt legally binding targets to reduce food waste by 2030 (Abou-Cleih, 2022). Hence, the process of dealing with food waste is not straightforward.

Alternative solutions to prevent or reduce food waste that are well discussed in the literature are connected to donations and redistribution, taxes, and subsidies to model and optimize people’s food and drink choices, and as a result households’ waste management. In this line of thought, taking an approach based on new-materialism and critical infrastructure studies, we propose to think about food waste as a set of relations mediated by objects and the infrastructural labor that supports them. Here, objects are a form of infrastructures, and are understood not as inert materials, but as crucial support systems of social relations (Graham and McFarlane, 2015). Infrastructural labor refers to the labor that, within and through objects (Gidwani, 2015; Stokes and Lawhon, 2023), facilitates alternative forms of waste governance.

Alternative forms of food waste governance

There are various alternatives to formal food waste governance. For example, anti-food waste initiatives can be divided according to four goals: those that reduce, redistribute, reuse, or create awareness about wasting food (Principato, 2018). Anti-waste organizations are mostly oriented toward food waste reduction objectives, this means local communities resist dominant and mainstream rules of production and consumption by choosing food that has been negated and is discarded by the system. Through dumpster diving practices and the running of non-profit, voluntarily community kitchens, food waste governance becomes a grassroot political strategy rather than only a tool for survival (Capponi, 2020).

In reaction to the limited effectiveness of governmental and local policies regarding food waste, there are also initiatives that counter food waste through charity organizations (Barba and Diaz-Ruiz, 2015; Vlaholias et al., 2015). These organizations deal with surplus food, vegetable esthetics and redistribute disposed food to people in need. Turner (2019, p. 200) refers to this precarious handling of food as the “attunement and responsiveness to the very materialities of food.” In her activist work, she discusses wasting practices at home and food rescue organizations. The latter are “characterised by being not-for-profit groups that collect surplus food, cooked and fresh, from a range of venues such as supermarkets, farmers’ markets and residential halls and, on a more ad-hoc basis, from sites where events such as conferences and weddings are held” (Turner, 2019, p. 208). Turner discusses these organizations considering their success in comparison to the failing of governmental initiatives to reduce waste, but she is also cautious about the risk of romanticizing these organizations, which in turn serves to reproduce neoliberal governance models that rest on the sole action of individuals and their responsive engagement without inducing any structural change; for instance, these organizations receive little governmental support in terms of sustainable funding. This hampers the financial possibilities of these initiatives, and makes waste a civic, rather than civil, responsibility.

The edibility of wasted food is a relational process engaging a variety of actors, human and non-human (Davies and Evans, 2019). Consequently, these initiatives do not rest solely on the engagement between voluntary activists, they also depend on a network of objects and infrastructural labors to make it happen (Gidwani, 2015; Stokes and Lawhon, 2023). Examples of objects that support grassroot food waste governance are maps for those engaged in dumpster diving activities (Capponi, 2020). These maps detail routines people develop and favorite spots to find food. Trash bins, another object, are not end points but rather points of flow for the movement of food—from what is to become wasted to what recovered and repurposed through laborious and often expensive recycling processes (Moore, 2012). Finally, in the last couple of years there has been an increase in the number of apps that help consumers acquire cheaper food before it is disposed by its providers (de Almeida Oroski, 2020).

Rather than focusing on how human and non-human alliances redefine and renegotiate the temporalities of food waste (Mattila et al., 2019), we explore the ways in which such alliances pause and stretch public spaces in the city. While most research approach objects involved in the renegotiation and redefinition of food waste domestically (for example, see Waitt and Phillips, 2016; Salonen, 2022), this article discusses objects engaged in renegotiating food edibility in the public space to contribute to the unsettling of unjust food relations. In what follows we describe two objects that support anti-food waste initiatives in The Hague, to advance how they can unsettle dominant governance practices and narratives related to food waste in the city. The everyday relations these two objects facilitate the unsettling of public spaces and the governance of food waste.

Methodological considerations

This paper is the result of a project carried out between 2021 and 2022 to identify the ways in which local communities in The Hague deal with the double problem of food waste and food insecurity. Supported by a seed grant for inter-faculty collaboration by the Global Transformation and Governance Challenges (GTGC) program of Leiden University, a group of researchers at different stages of their academic careers engaged in participatory action fieldwork with two initiatives in the city:2 Conscious Kitchen and Vers & Vrij. Following an interpretivist, community-based and participatory methodological approach, the researchers joined the initiatives as volunteers. This allowed us to not only observe but also experience relations derived from practices of food waste governance in everyday life (Lehtokunnas et al., 2022).

The stories we include in this paper are generalized and anonymized excerpts quilted by the authors of this article in collaboration with student assistants and the design team of The Hague University of Applied Sciences. As an embodied practice of knowledge production,3 that challenges the artificial binary separating knowledge from bodies, our team engaged in a practice of listening and telling stories derived from the interactions associated to grassroots food waste governance. Such co-creation practices emanate from an entanglement of experiences, ideas, and reflective moments, discussed throughout the research process. At a point during the research, it became apparent that these stories were not only the stories of the people involved in these initiatives, but also of the objects that enabled these entanglements. Hence, we decided to focus on the stories of the objects that facilitated and mobilized interactions, and the management and transformation of food waste. The contexts, colors, shapes and narratives of these stories challenge de-contextualized, invasive research methods and extractive practices of knowledge production, and, at the same time, they forefront the everyday aspects of today’s food waste relations. In this paper, we focus on two objects, each playing a key role in structuring the voluntary engagement of these initiatives. In what follows we present the stories of a cargo bike and a fridge.

Results and discussion

Conscious Kitchen (CK) and Ver & Vrij (V&V) are two initiatives that help reduce the problem of food waste by collecting disposed foods from the Haagse Markt and use it to prepare edible meals: the former does it with the help of a cargo bike (represented above in dark blue), the latter with the help of a fridge (represented above in pink). The two objects reveal the networks of exchanges between different people, locations, disposed foods. Furthermore, these are everyday domestic objects which are transformed into brokers that unsettle food relations: redefining food waste and the very notion of food waste governance. These anti-food waste initiatives, and the objects that support them, highlight the need to approach food scarcity, insecurity and wasting as symptoms of much broader social inequalities. These objects make visible how some people find use in what others discard and waste, reflecting what Sarah Ahmed describes as “queer use” (Ahmed, 2019). These objects change the form of food, from discarded to edible. In doing so, they trans/from and queer what counts as waste and how food waste governance takes place in the city. These are their stories:

The cargo bike

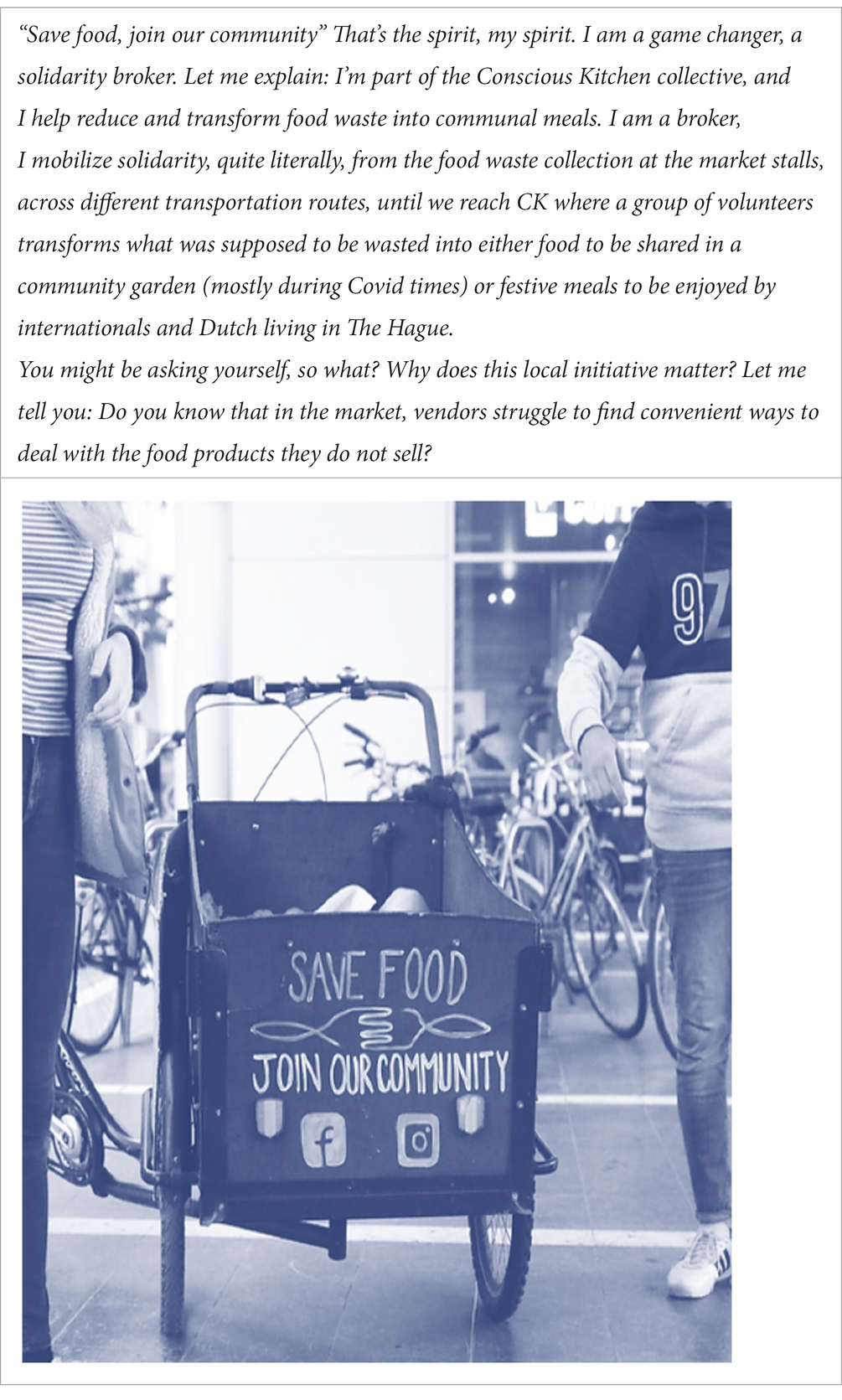

CK is an organization created in 2016 by international students to reduce food waste and organize weekly community meals prepared with food disposed by vendors at the Haagse Markt. In many other cities in the Netherlands, there are initiatives similar to CK operating under the same principle of reducing food waste and promoting food for solidarity and communal meals. CK volunteers ride a cargo bike to collect the wasted food from the market. This is their story:

The public fridge

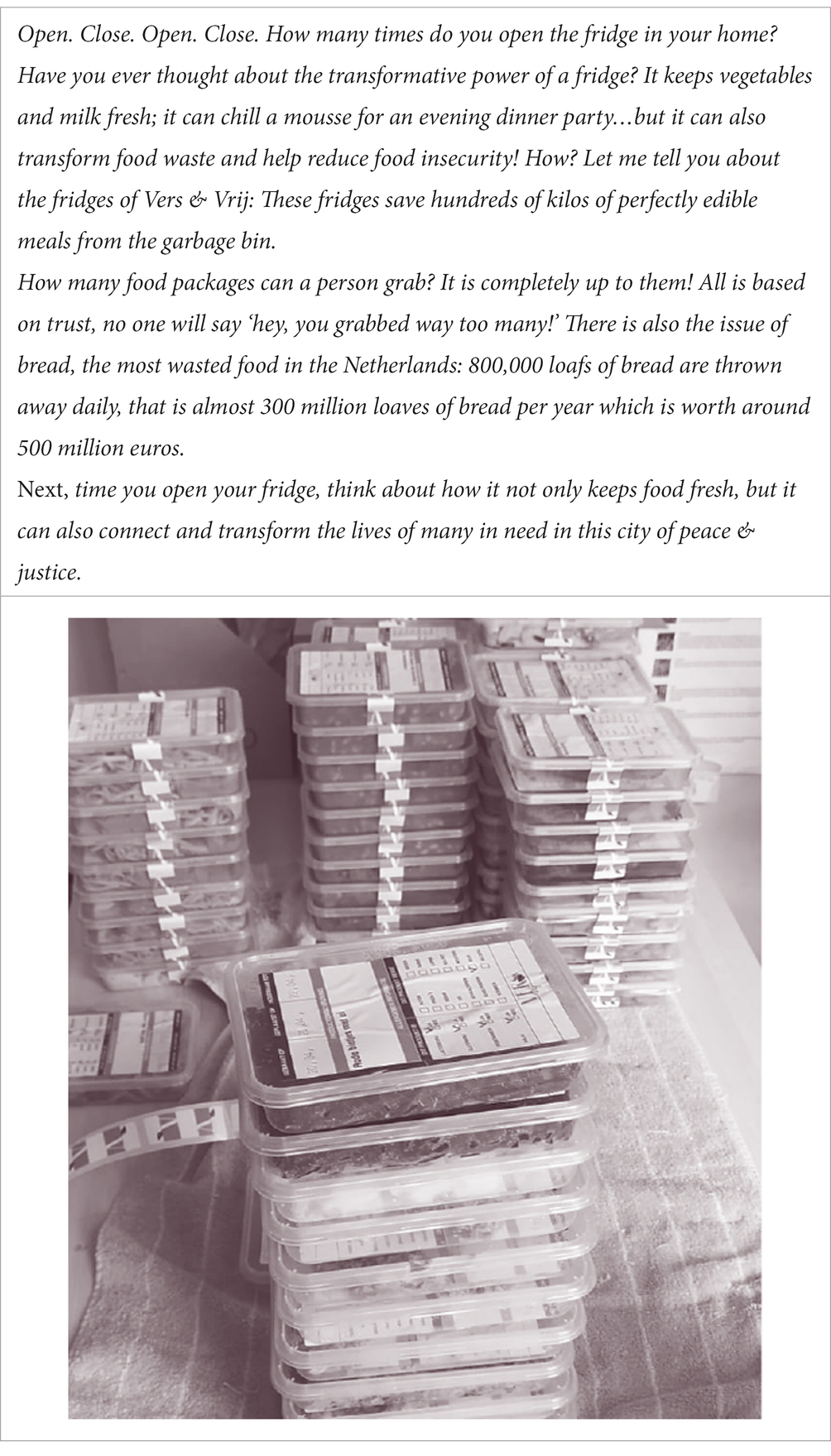

V&V is an organization operating in The Hague since 2019. Their aim is to reduce food waste and food poverty in the city by collecting leftovers from local restaurants and, in collaboration with a network of volunteers, work to pre-pack individual meals to be stored in one of the 26 public fridges distributed throughout the city. Anyone who is struggling financially can take this food from any of the fridges, installed in churches, community centers, mosques, or second-hand stores. The distribution works under principles of trust and solidarity for those in need of food. Each fridge helps feed approximately 250 people per month. All food packages undergo a quality check, have ‘due dates and allergy information, to ensure the safety and hygiene of the distributed food (food packages have a unique V&V sticker which breaks if the package has been opened). Those hosting the fridges also serve as information points, connecting financially insecure households to other relevant resources at the municipality, for example language courses. The use of these fridges unsettle public spaces, confronting us with food surplus and food scarcity in the city. This is their story:

The cargo bike and fridge are crucial objects to mobilize the trans/formation of disposed food into perfectly edible meals. In fact, the efforts of CK and V&V illustrate examples of alternative food waste governance initiatives we discussed above in the literature review. Both are non-profit organizations, relying in the exercise of local and urban forms of civic engagement to push the frontiers of food waste governance in the city. These are ordinary objects that, through their “queer use” (Ahmed, 2019), placement in and movement through public spaces, connect the city while trans/forming wasted food. By collectively preparing and collecting food deemed for disposal, V&V and CK operate as alternative food waste governance regimes, that unsettle not only what counts as food (i.e., what is disposed is not wasted) and also establish relations through food waste across the city.

Conclusion

Waste is not a fixed category representing what is left over or disposed; it is also connected to what is consumed and what is discarded. Thus, there is no clear binary predefining when something becomes waste. Instead, the idea of waste is fluid and contextual. Speaking of disposed food centers, a journey where different actors (human and non-human) engage in deciding what is wasted, when and how. The above examples show the stories of objects involved in the reduction of food waste and its trans/formation into edible food. These objects transverse and transcend private and public spaces, materialities of the human and the non-human, enabling a network of collaborations, where food waste is transformed physically and ontologically. Thus, queering the very notion of food waste, these more-than-human relations transform public spaces in the city through grassroot food waste governance. They also show how, to unsettle conventional understandings of (food) waste, it is necessary to renegotiate social relations and search for spaces of collective solidarity in cities like The Hague. The infrastructural labor associated to the cargo bike and the fridge, trans/forms what is wasted into a source of sociability and connection, a network of weak ties that has the strength to tackle both the problem of food waste and food scarcity. The stories of these objects illustrate the patchwork behind processes of waste production and recycling: who does it when, where, how, for what purposes and, at the same time, these stories offer a window into alternative regenerative directions through food waste flow and entanglements.

This project has made visible forms of exchange, collaborations and transformations derived from interactions between objects, food waste and civic action that are often hidden from the public eye. By concentrating on the stories of ordinary objects such as a cargo bike and a fridge, our intention has been not only to unsettle the ways in which we think about food waste, but also to identify alternative ways to relate to it and to one another These objects have served the purpose of displacing the question from the experiences of vulnerability associated to food scarcity and waste, to other stories that speak of trans/formations through disposed food exchange. These ordinary objects reflect extraordinary forms of sociability that promote sustainable behavior and the necessary rethinking of the work and infrastructures necessary to connect a more effective food waste governance.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation upon request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Faculty of Humanities Research Ethics Committee, Leiden University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

DVM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision. JT: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EBM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research in this project was supported by a seed grant by the Global Transformation and Governance Challenges (GTGC) programme of Leiden University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The Farm to Fork strategy is part of the larger EU Green New Deal. Available at: https://food.ec.europa.eu/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en.

2. ^The project was much larger and involved research also in Leiden and other organizations not included in this paper. The team of researchers included six students’ assistants enrolled in undergraduate (Adam Emara, Sim Hoekstra, Rosi-Selam Reusing) MA (Sarah Murray, Luca Bruls) and PhD (Daan var. den Laan) programs; as well as three academics from the Faculties of Humanities and Governance and Global Affairs of Leiden University. We also had an inter-university collaboration with a team of designers from THUAS, The Hague University of Applied Science. For more information about the seed grant project see Stories of Solidarity during Covid-19.

3. ^The project also attempted an alternative way to disseminate the findings of the research by organizing an exhibition based on these objects’ stories at the atrium of The Hague municipality in June 2022. For more information check here details of the exhibition.

References

Abou-Cleih, S. “Revealed: The countries championing and blocking EU food waste action”. European Environmental Bureau. Available at: https://eeb.org/revealed-the-countries-championing-and-blocking-eu-food-waste-action/ (2022).

Barba, M., and Diaz-Ruiz, R. (2015). “Switching imperfect and ugly products to beautiful opportunities” in Envisioning a future without food waste and food poverty. eds. L. E. San-Epifanio and M. D. R. Scheifler (Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers)

Capponi, G. (2020). The taste of waste: reclaiming and sharing rotten food among squatters in London. Food Cult Soc 23, 489–505. doi: 10.1080/15528014.2020.1773691

Davies, A., and Evans, D. (2019). Urban food sharing: emerging geographies of production, consumption and exchange. Geoforum 99, 154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.11.015

de Almeida Oroski, F. (2020). “Exploring food waste reducing apps—a business model Lens” in Food waste management. Solving the wicked problem. eds. E. Närvänen, N. Mesiranta, M. Mattila, and A. Heikkinen (Palgrave Macmillan: Switzerland)

Evans, D., Campbell, H., and Murcott, A. (2013). A brief pre-history of food waste and the social sciences. Sociol. Rev. 60, 5–26. doi: 10.1111/1467-954X.12035

FAO The state of food and agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. UN – Rome: FAO. (2019).

Gidwani, V. (2015). The work of waste: inside India's infra-economy. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 40, 575–595. doi: 10.1111/tran.12094

Gille, Z. (2010). Reassembling the macrosocial: modes of production, actor networks and waste regimes. Environ. Plan. A. 42, 1049–1064. doi: 10.1068/a42122

Graham, S., and McFarlane, C. Infrastructural lives: Urban infrastructure in context. Oxon and New York: Routledge. (2015).

Hawkins, G. The ethics of waste. How we relate to rubbish. Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, (2006).

Janssen, J., van der Velde, L., and Kiefte-de Jong, J. (2022). Food insecurity in Dutch disadvantaged neighbourhoods: a socio-ecological approach. J Nutr Sci 11:e52. doi: 10.1017/jns.2022.48

Lehtokunnas, T., Mattila, M., Närvänen, E., and Mesiranta, N. (2022). Towards a circular economy in food consumption: food waste reduction practices as ethical work. J. Consum. Cult. 22, 227–245. doi: 10.1177/1469540520926252

Mattila, M., Mesiranta, N., Närvänen, E., Koskinen, O., and Sutinen, U. M. (2019). Dances with potential food waste: organising temporality in food waste reduction practices. Time Soc. 28, 1619–1644. doi: 10.1177/0961463X18784123

Moore, S. (2012). Garbage matters: concepts in new geographies of waste. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 36, 780–799. doi: 10.1177/0309132512437077

Principato, L. Food waste at consumer level: A comprehensive literature review. Cham: SpringerBeliefs, (2018).

Salonen, A. S. (2022). Ordinary overflow: food waste and the ethics of the refrigerator. Food Foodways 30, 145–164. doi: 10.1080/07409710.2022.2089828

Stichting Samen Tegen Voedselverspilling. Samen Tegen Voedselverspilling campaign. Available at: https://samentegenvoedselverspilling.nl/home/de-stichting/ (2023).

Sheldon, M. Netherlands cuts down on food waste with public awareness campaign. Available at: https://www.nycfoodpolicy.org/food-policy-snapshot-netherlands-food-waste-public-awareness-campaign/ (2021).

Stokes, K., and Lawhon, M. (2023). What counts as infrastructural labour? Community action as waste work in South Africa. Area Dev Policy 2023, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/23792949.2022.2145321

Turner, B. (2019). “Taste, waste and the new materiality of food” in Critical food studies. ed. M. Goodman (New York: Routledge)

UNEP Planetary action. Making peace with nature report, Available at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/37946/UNEP_AR2021.pdf (2021).

Vlaholias, E. G., Thompson, K., Every, D., and Dawson, D. (2015). “Reducing food waste through charity: exploring the giving and receiving of redistributed food” in Envisioning a future without food waste and food poverty. eds. L. E. San-Epifanio and M. D. R. Scheifler (Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers)

Keywords: food waste, infrastructures, governance, stories/storytelling, infrastructural labor, invisible actors

Citation: Vicherat Mattar D, Thrivikraman J and Burgos Martínez E (2023) Un-settling the frontiers of food waste in the Netherlands: infrastructural stories of food waste transformation in the Hague. Front. Sustain. 4:1259793. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2023.1259793

Edited by:

Ann Trevenen-Jones, Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Alessia Tropea, University of Messina, ItalyNina Mesiranta, Tampere University, Finland

Copyright © 2023 Vicherat Mattar, Thrivikraman and Burgos Martínez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniela Vicherat Mattar, ZC5hLnZpY2hlcmF0Lm1hdHRhckBsdWMubGVpZGVudW5pdi5ubA==; Jyothi Thrivikraman, ai5rLnRocml2aWtyYW1hbkBsdWMubGVpZGVudW5pdi5ubA==; Elena Burgos Martínez, ZS5lLmJ1cmdvcy5tYXJ0aW5lekBodW0ubGVpZGVudW5pdi5ubA==

Daniela Vicherat Mattar

Daniela Vicherat Mattar Jyothi Thrivikraman

Jyothi Thrivikraman Elena Burgos Martínez

Elena Burgos Martínez