- Centre for Consumer Society Research, Faculty of Social Science, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

The demonstrated urgency of the climate crisis would require mobilization by a larger and more diverse set of participants than those usually recognized as environmental activists. Hence this article asks: (1) What conditions enable unlikely participants (such as men working in manual occupations) to engage in and identify with a climate movement? And (2) what is it about the relationship between participants’ biographies, the practices of the climate movement and the interaction between them that allows – or affords – such identification to occur? I draw on an approach to identity formation as situated practice, i.e., as occurring in situations where social relations are enacted while drawing on the individual experience and shared understandings that participants bring to the situation. Based on fieldwork in Finnish municipalities that have committed to climate neutrality, I find that the conditions for engagement depend on socio-cultural affordances for engaging in climate action, which (1) accept and welcome participants’ life histories and lifestyles (2) build on and respect participants’ competences and multiple forms of expertise, (3) engage participants in practices that are familiar enough not to produce anxiety but stimulating enough to be fun, and (4) produce small but visible achievements that are acknowledged as such by both participants and onlookers. The current study contributes to previous research arguing for a more populist approach to climate policy by emphasizing existing competences and embodied practices as an avenue for engagement in climate action.

1 Introduction

As climate change has been widely recognized as an existential threat to humankind, it has gained centrality in politics of all kinds: global, national, cultural and local (Bulkeley et al., 2016; McCright et al., 2016). These different forms of politics are intertwined in many ways. While current forms of climate governance present themselves as a political (Swyngedouw, 2013), in everyday life, climate policy influences material conditions, subjectivities and forms of advocacy or resistance that can be viewed as political (Bulkeley et al., 2016). This entails that the climate transition, i.e., a systematic shift toward energy and other resource practices that mitigate climate change, has political implications for everyday life practices, such as homes, mobility and energy use, and these are different for different individuals and groups.

Current research suggests that only some groups in society are actively engaged in combating climate change (McCright et al., 2016; Brulle and Norgaard, 2019). However, the urgency of the climate crisis would require mobilization by a larger and more diverse set of participants than those usually recognized as environmental activists. Instead, recent years have seen the emergence of populist movements opposing (some forms of) climate policy. Often, such counter-movements are depicted as consisting of a disproportionate share of men in manual occupations, whose economic survival, dignity and self-esteem are tied to a fossil-fuel based system of production (Erkamo, 2019; Lucas and Davison, 2019; Lübke, 2022; Patterson, 2022). Yet such structural perspectives neglect the social construction of interests vis-à-vis climate policy, as well as the kinds of identities available for citizens when participating in climate action (Middlemiss, 2010; Hobson, 2013; Patterson, 2022). In view of the need to engage a wide and diverse citizenship in the movement to combat climate change, authors have called for reframing climate action in more inclusive ways (Meyer, 2008; Anderson, 2010; Anantharaman, 2018; Lucas and Davison, 2019; Steele et al., 2021) and widening the discourse on what constitutes environmentalism (Harper et al., 2009).

Emerging research includes examples of climate engagement by groups like farmers, indigenous people and working-class people (Jalas et al., 2014; Evans and Phelan, 2016; Flemsæter et al., 2018; Davidson et al., 2019). In parallel, other authors have studied the inclusiveness or exclusiveness of ongoing energy transitions (Moss et al., 2015; MacArthur and Matthewman, 2018). Yet there is a lack of consistent evidence on how and why climate movements succeed or fail to engage diverse groups of people. The impetus for this article is the observation that the climate movement has attracted several kinds of people: academics, students, teenagers, green activists, celebrities and business managers (Doyle et al., 2017; Chatterji and Toffel, 2019; Boucher et al., 2021; Gardner et al., 2021; Noth and Tonzer, 2022). Yet, among the ranks of climate activists, men working in manual occupations and living in peripheral areas are relatively invisible (Erkamo, 2019; Lucas and Davison, 2019; Lübke, 2022), and this is potentially linked to their identities (Patterson, 2022). Hence this article asks: (1) What conditions enable unlikely participants (such as men working in manual occupations) to engage in and identify with a climate movement? And (2) what is it about the relationship between these participants’ biographies, the practices of the climate movement and the interaction between them that allows – or affords – such identification to occur?

For this endeavor, I build on an approach to identity formation and social movement (or group) identification as social and situated practice. From this perspective, situated practices are the sites of the political-economic, social, historical and cultural structuring of social existence (Holland and Lave, 2001). Situated practice thus refers to particular situations where social relations are enacted, while acknowledging that these situations involve historical structures and ‘rules’ brought in by participants (“history in person”), as well as through the history of collectively recognized discourses, practices, policies and artifacts (Holland, 2003). Drawing on the perspective of identification as social and situated practice, I explore my research questions through the case study of a carbon-neutral municipalities movement in Finland and the ways in which three men working in the construction industry engage with it. Through this in-depth analysis, I explore the “cultural affordances” (Ramstead et al., 2016; Kaaronen, 2017) of this particular local climate movement (i.e., the kind of space it creates for participation), as well as the ways in which identification with this movement evolves through social practice. While not aiming at generalization, this illustrative analysis aims to tease out propositions about cultural affordances that allow for more inclusive identification with climate movements. Through this, I aim to contribute to critical studies of inclusion and exclusion in transitions (Moss et al., 2015), including arguments for more populist approaches to climate policy (Meyer, 2008; MacArthur and Matthewman, 2018).

2 Previous research, analytical framework and research gap

2.1 The political struggle over energy and climate transitions

Recent years have seen a lively discussion emerge on how inclusive energy transitions are. Such transitions are closely related to climate change mitigation and the development of a more sustainable economy (Kanger and Schot, 2019). While most of the research on resistance to transitions has focused on resistance by incumbent powers such as energy companies (e.g., Kungl, 2015), recent work has started to address the inclusivity of such transitions for different kinds of citizens. For example, Moss et al. (2015) investigated how the uptake of the German Energiewende (i.e., energy transition) has led to various contestations, resulting for example in debates about re-municipalization of power production. Concerning the same Energiewende, Bosch and Schmidt (2020) show how existing power asymmetries and the resulting injustices are also part of renewable energy landscapes, resulting in local resistance to renewable energy installations. In a very different context, MacArthur and Matthewman (2018) discuss populist resistance and alternative transitions among the indigenous Māori people in New Zealand, where local resistance to “development” is seen to reflect unease over a neoliberal economic model, while Māori people’s activism in community-owned renewable energy projects is easily overlooked in the mainstream policy discussions.

What we can take from this literature is that popular social movements can emerge to promote renewable energy (e.g., Seyfang et al., 2013), but some of the resistance to renewable energy developments arises from equally popular movements of people who feel their life-world is being colonized by outside interests. While these divisions can easily be seen as contestations between “the locals” and non-local colonizers (e.g., foreign investors), Batel and Devine-Wright (2017) suggest that the issue is more complex and needs to be analyzed in the context of broader intergroup and identity processes within ongoing socio-historical and political struggles between central and peripheral regions. This suggests that the inclusiveness of a transition is not only about how well local interests are represented in concrete terms vis-à-vis outsiders, but also about how various identities are evoked in debates about the transition. Indeed, this is what is seen when rising right-wing populism politics gain a foothold of local resistance to energy development, and serve to amplify such movements to a broader, national and party-political scale (Fraune and Knodt, 2018).

While most of the work on environmental contestations draws on local case studies, questions of identity and movement practices suggest that there are deep-seated forces at work when transitions unfold in the everyday lives of ordinary people (Fraune and Knodt, 2018). This suggests a need to go beneath and beyond what is happening in overt environmental conflicts or controversies to ask when and why people come to identify with certain movements, and what kinds of practices are afforded in those movements. A polarization of the debate over the climate transition can serve to bring to light genuine grievances (MacArthur and Matthewman, 2018), but it can equally pit people on two sides of a divide that revolves more around identities than specific issues (see, e.g., Lucas and Warman, 2018). Hence, Lucas and Warman (2018) emphasize the importance of sub-politics, i.e., associations between groups that cut across conventional political divides, in the resolution of environmental controversies.

2.2 Identity as shaped in situated practice and enduring struggles

Identity politics is usually presented as a term with negative connotations, referring to political mobilization around the grievances of particular groups and their demands for recognition, as well as a sharp division between insiders and out-groups (Fukuyama, 2018). Yet there are other ways to explore the relationship between identity and politics in order to see how identities are shaped in encounters and struggles. I draw here on work by Holland (2003, 2010), Holland and Lave (2001) and Holland and Lachicotte (2007) as a framework for how political identities develop in dialogical, situated practice. Their work draws on ethnographic work on how identities are formed in the context of “figured worlds,” i.e., socially and culturally constructed contexts of interaction (such as Alcoholics Anonymous groups) where particular roles and characters are recognized (Holland and Lachicotte, 2007).

In this perspective, identities constitute an organized complex system of thoughts, feelings, memories and experience accrued through personal history, which is available for that person as a platform for action and response in different situations (Holland and Lachicotte, 2007). Identities evolve historically in social practice, through dialogic encounters with the available cultural resources and historically shaped struggles (Holland and Lave, 2001), meaning that individuals develop their identities throughout their lives, and especially when required to defend their way of life. Social practice, i.e., various sites of social encounters and social action, are sites where individuals and groups continually reform themselves as individuals and groups through cultural materials drawn from their own past and experience and that of others (Holland et al., 1998). Different situations provide different affordances for such processes, but each encounter creates the conditions for a reshaping of both individual and collective identities (Holland, 2003).

When approaching identity from a practice perspective, the goal is thus not to understand identity as an entity, but identity as manifest in practice (Wieland, 2010; Patterson, 2022). From this perspective, identity politics are understood more in the sense that Mouffe (1995) refers to them, i.e., as an inevitable part of politics in which group identities are created along with differences to outgroups, and where a multiplicity of identities becomes important for personhood. A practice perspective to identity does not consider multiple identities as a problem in themselves, but instead focuses on how dilemmas of multiple identification become problematic in practice (Holland, 2003). Moreover, this perspective places emphasis on how individuals, alone or together, improvise solutions to identity dilemmas (Holland, 2003).

As an example, Holland (2003) has investigated social movement identities in environmental movements in the USA. One study investigated encounters between a local environmental organization (Blue Ridge Gamelands Group, BRGG) in the Appalachians and other environmental NGOs in a controversy surrounding the designation of the locals’ home area as a national park. BRGG opposed this designation, since it would result in a ban on hunting in the area, which the BRGG members considered a historical entitlement and an important traditional practice of self-provisioning. The controversy created a site for a dialogic process where the BRGG members were required to reconsider their identities as environmentalists vis-à-vis mainstream (more educated, city-dwelling) environmentalists, and consider how they can justify themselves as environmentalist, when they felt that the others considered them “hillbillies.” The difficulties of being both a hunter and an environmentalist resulted in experiences of social distance and disrespect from mainstream environmentalist groups by BRGG members, potentially with far-reaching consequences. As Holland (2003), 47 notes: “Where such groups are alienated, their pro-environmental sentiments are likely to go unorganized and their movement sentiments serve as a force that can be more easily mobilized against, rather than for, subsequent projects of environmental protection.”

2.3 Cultural affordances of climate movements

When applying the perspective of situated practice to identity politics in the climate transition, attention is directed to how different people and groups accommodate their personal histories and previous affiliations and attachments to a new situation and the new kinds of practices that it gives rise to. If we think of the previously described controversy between BRGG and mainstream environmental movements (Holland, 2003), then (at least) two sets of identities are at stake: those of the BRGG members and those of the mainstream environmental groups. We can also ask the question differently: what kinds of identities does being a climate activist afford, i.e., what kinds of identities are available and accessible?

Recent research has started to address the exclusiveness of various sustainability movements and projects. For example, frequently propagated individual actions to protect the environment appear to be directed at – and more easily taken up by – citizens with a middle-class lifestyle. In particular, criticism has been directed toward the exclusiveness of initiatives for sustainable consumption, i.e., campaigns that target individuals in order to promote more sustainable consumption patterns, such as vehicle or food choices. These are by nature more easily adopted by the more well-to-do citizens and resonate with a middle-class ideal of personal control (Hobson, 2013). For example, in qualitative research conducted in Washington State, USA, Kennedy and Givens (2019) show that less well-off people described a deep sense of powerlessness to engage in what are often considered “everyday climate actions” (such as driving an electric vehicle), whereas high-status participants felt capable to do so and believed their actions made a difference.

The practices of community-based environmental movements may also be inadvertently exclusionary of working-class identities. Anantharaman et al. (2019) show that such exclusionary practices can be found in Canada and the UK in community-based sustainable consumption projects, such as the provision of energy advice or the promotion of recycling or organic, local food. In keeping with the middle-class sensibilities and tastes of their founders, such community movements tend to favor apolitical and behavioral --rather than community wide-- solutions to environmental problems. These practices were found to create feedback cycles which influenced who participated in the movements, hence reinforcing middle-class bias.

Meyer (2008) has discussed the implications for promoting popular climate action of two different discourses of environmentalism: paternalism and populism. The paternalist discourse relies on metropolitan organizations drawing on expert scientific knowledge to communicate the abstract, technical and global problem of climate change to “the uninitiated masses,” thus reinforcing perceptions of elitism. Yet such communications, while successful in raising awareness and concern about climate change, have failed to increase their salience in the popular consciousness. Meyer (2008) evokes the alterative discourse of populism, grounded in agrarian and common-pool movements, arguing that it could dramatically expand the constituencies for which climate action is salient. This would imply seeking to transcend the confines of climate change as an ‘environmental issue’ to be seen as part of localized, everyday material concerns for community reinvestment, sustainable jobs, energy independence, more convenient transportation, reduced utility bills, or more comfortable homes. Wilk (2022) adds a further ingredient to a more popular (or populist) view on sustainability by calling for more research on “fun” in the context of sustainable consumption.

Following these lines of thought, I would like to suggest that different kinds of climate movements or programs have different kind of affordances for engagement by people in different kinds of circumstances and with different kinds of personal histories. The concept of affordances has mostly been used to denote material, technical aspects of artifacts that influence how they are easiest to use (e.g., Norman, 2013), and later, the scope for social action created by information and communication technologies, including social media platforms (e.g., Ostertag and Ortiz, 2017). Here, affordances refer to what you can easily do with an object like a door or a medium like Instagram (and what actions, conversely, are more difficult or impossible). Kaaronen (2017) understands affordances as the dynamic systems relations between human actors and their physical and socio-cultural environment, and suggests that the notion of affordances could be expanded from the most common concept of object-level affordances (i.e., what kinds of uses an artifact affords), to include also household affordances (e.g., how household energy systems are designed), urban affordances (e.g., locally sensitive design of transport systems) and socio-cultural affordances. This last category remains somewhat abstract, but I would like to apply it to the features of climate movements or programs aiming to involve people who do not usually identify as movement activists. In this context, socio-cultural affordances could be tentatively defined as the perceived possibilities for people with different backgrounds to identify with and engage in climate movements or programs, which depend on the kinds of practices in which participants can engage. The ability to engage depends on feeling capable of acting within the explicit or implicit expectations, norms, conventions, and social practices present in a particular situation (Ramstead et al., 2016). I will elaborate on this concept through an empirical analysis of a particular climate action program and some of its participants, and the situated practices though which some of these “unusual suspects” came to identify with that movement.

3 Research design and methods

3.1 Research context

This research draws on the context of a particular kind of climate program: the Finnish Carbon Neutral Communities (HINKUHINKU) program (Carbon Neutral Finland, 2023). HINKU was set up in the autumn of 2008 and originally aimed to engage small municipalities outside the metropolitan area as “change laboratories” for new solutions to climate change. The original initiative arose from co-operation between a small (since then defunct) business leaders’ social responsibility initiative and the Finnish Environment Institute. Based on personal ties to particular localities, they selected five municipalities to partner with. The municipalities joining the project pledged to decrease greenhouse gas emissions generated within their territory from the 2007 level by 80 per cent by 2030.

HINKU is in no ways unique in Europe or in the world. Hundreds of cities and municipalities worldwide have made climate pledges and engaged in climate action in many ways, also in collaboration with each other (Neij and Heiskanen, 2021). Some of these entail using the local context as a testbed for technological development by external interests (Evans and Karvonen, 2014), while others emerge more from the bottom up, from situated concerns (Hodson et al., 2016). While HINKU emerged from the non-local interests of businesspeople with tenuous roots in the communities, as well as climate concern in the Finnish Environment Institute, it is different from many pseudo-movements of mega-cities (Hodson and Marvin, 2007) as it originally and explicitly aimed to engage ‘ordinary’ municipalities, i.e., small places that are not known for being particularly avant-garde or vibrant (cf. Seyfang et al., 2013). In particular, in the early days, there was no agenda or even plan for promoting particular technologies or commercial interests. Instead, it was expected that gaining the commitment of the municipalities would stimulate experimentation by local people in search of solutions for reaching the climate targets (Heiskanen et al., 2015).

Whether or not HINKU is really a social movement is open for contestation. The question is even more relevant since the program has become very popular and by the end of 2020 more than 70 municipalities (including some larger cities) have joined in. It is not a social movement in the sense of being conceived by citizens, but in the early days and in many ways still today it is very open-ended in terms of what activities are included, and how municipal civil servants, elected local politicians, local businesses or citizens are expected to participate. Hence, alongside more formal actions by municipalities, various kinds of civic activities have emerged under its auspices, including, e.g., “energy evenings,” “open homes walks” and a “climate fast” among local congregations. While the entire populations are not involved – even in the pioneering five municipalities – in these small original locations there has been significant overlap with various civic activities, partly because active participants also have central roles in local associations [reference removed for review].

A final note on context concerns popular perceptions of climate change mitigation in Finland. In 2019, the social democrat-led coalition government’s program included the aim to make the country carbon neutral by 2035, which is one of the most ambitious targets in the world. This was preceded by a tough and very close election campaign in which climate ambitions came to take an important position (Chen et al., 2021), with the right-wing populist anti-immigration party amassing popular support by voicing concerns about a purported ban on internal combustion engines, energy policies that would undermine the country’s economic competitiveness and put jobs at risk, and rising fuel and energy taxes. Vestiges of this campaign are perhaps visible in later opinion polls, where opinions were polarized, with 80% of the (mainly urban, educated) supporters of the Greens party agreeing that Finland should be a forerunner in climate policy, whereas 50% of the rural dominated Center Party and as many as 75% of the (also rural-dominated) populist, right-wing Finns Party disagreeing with this claim (HS, 2019). In the 2023 general elections, the Finns Party gained more seats than the social democrats, winning seats especially in rural areas, with one of their campaign platforms having been to delay the carbon neutrality target year.

On the other hand, climate campaigning has been heavily focused on the promotion of individual climate-friendly lifestyles often associated with young urbanites, such as cycling and veganism. In another poll (Lehtonen et al., 2020), almost two-thirds of respondents considered the public discussion on climate change as putting the blame on ordinary people, with men (68%), rural (71%) and populist conservative (90%) respondents particularly inclined to think this way. Since climate seems to be an issue that divides Finns along an urban–rural axis as well as along the lines of cultural capital, it is interesting to investigate the affordances of a program that explicitly seeks to engage rural people.

3.2 Research design

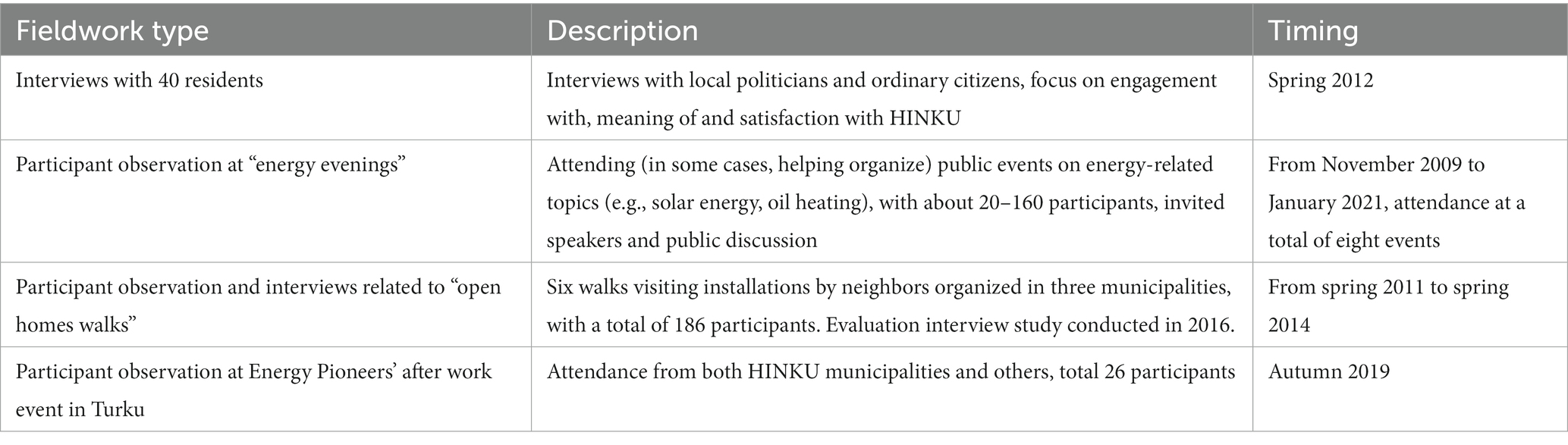

Exploration of the socio-cultural affordances of the HINKU program draws on participant observation of this program (as an outsider, in a research and minor support role) since its inception in 2008. Fieldwork has been conducted at multiple sites since 2009 (Table 1). Among others, I attended 14 local events (“energy evenings,” “open homes walks”) in 2009–2021 and had several informal talks with city council members and participating citizens. In spring 2012 [references removed for peer review], together with colleagues, we interviewed 40 locals on their expectations, understandings and practices of engaging with HINKU. In particular, we explored how people with various backgrounds (men, women, entrepreneurs, workers, unemployed and retirees, as well as municipal council members) engaged in various practices such as “energy evenings,” debates over local energy provision choices, and personal actions such as recycling or heating system renovations. In order to keep track of how HINKU practices have continued to evolve since those early days, I assembled a database of local newspaper articles, events announced on the municipality’s website, as well as discussions on the local Facebook site. A list these document sources is provided in Annex 1.

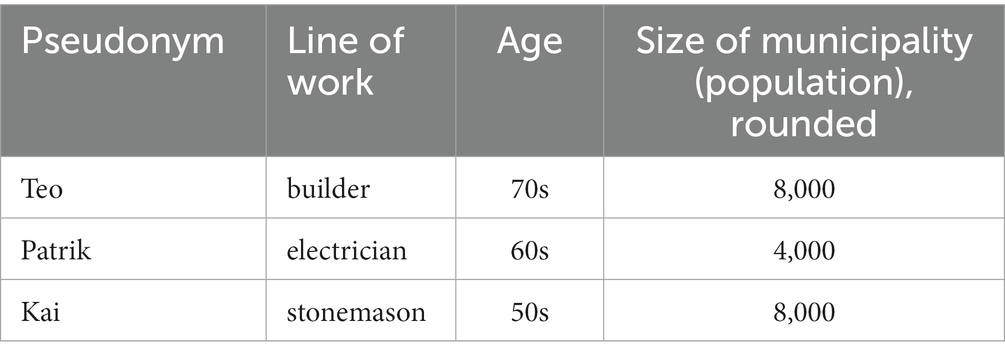

To complement this fieldwork and gain a more personal perspective on identification as social practice, I have selected three individuals to interview in detail, as representatives of groups who usually express disengagement with climate action, and tend to be more likely to be skeptical of climate policies in survey studies (Lehtonen et al., 2020; Lübke, 2022). They were all men, all working in the construction sector, all live in rural and declining areas in HINKU municipalities, and were all middle-aged or older (Table 2) but representing different party political views. In order to secure their anonymity, they are all referred to with pseudonyms.

The interviews were conducted in the spring of 2021. They varied in length, and one of them is more comprehensive than the others. This most comprehensive interview data consists of two biographical interviews, lasting about 1 hour each, as well as a similar interview (1.5 h) from 2012. The interview focused on putting together a biography of the person, along with details of his involvement in HINKU and other associations where he was active, and the kinds of practices in which he was involved. It then focused on exploring struggles and contentious practices encountered in HINKU and other climate-related contexts, as well as exploring when and how the interviewee felt he was welcome, necessary and at ease in HINKU and other association practices. We also discussed whether he had friends or acquaintances who were more skeptical about climate activism or particular practices associated with it. The other two interviews were shorter, about 30 min, covering the same topics as the first one but less in depth. I recognize that this data is not generalizable, and merely serves to illustrate and elaborate the framework developed above.

4 Results: practices of local engagement with climate policy

I will first discuss the study participants’ views on climate change and climate action, with a focus on identifying practices through which they feel included or excluded from being active participants in climate change mitigation. I then turn to outlining the affordances of HINKU for engaging this type of participants, in contrast to non-localized climate policy.

4.1 Participants’ views on climate change and ways of engaging with local climate action

None of the interviewees contested climate change as a physical reality. However, there were different views on Finnish climate policy and the level of responsibility that Finland should shoulder in terms of climate change mitigation. The person referred to with the pseudonym Patrik, while noting that climate change is a genuine concern, proffered a view that often circulates in the Finnish climate debate:

Well, to say something, then well, [I understood that HINKU is about the notion] that small streams build up to a large flow. Since definitely, Finland’s actions are rather small [on a global scale] and so are our opportunities [to make a difference] but at least our own environment gets better.

On further questioning, Patrik explained that Finland is very small, in a very large world, so we could not influence climate change whatever we did, but that the actions promoted in climate policy, such as the use of renewable energy, could improve the local environment and modernize the local building stock. He does not want to discuss local views on climate action, but admits that his acquaintances do discuss what Finland is expected to do compared with what, on the other hand, is happening for example in China (i.e., small countries like Finland cannot, perhaps ought not, do so much, given that large polluters like China are seemingly doing so little).

Patrik has been involved in local climate action via his work, electrical installations, and he says that these include installation of solar panels. He had been installing off-grid solar panels in summer cottages for 30 years, but gained a new business around 2015, when on-grid systems started to proliferate (thanks partly to HINKU activities, see Matschoss and Heiskanen, 2017), and he could put his competencies to new use. Instead of his own business, he wants to highlight that he has installed panels on his own roof and installed a ground-source heat pump, and actually gets more interested when discussing the details of how one can utilize the entire production of the solar panel system oneself (even though he says this does not save money, but is cost-neutral). Since has been an early adopter of advanced solutions, he is able to provide advice to others.

Kai (pseudonym), on the other hand, considers that action needs to be taken to combat climate change, even though it does raise controversial discussions locally. He feels this is because the benefits of certain technologies presented as climate solutions, like electric vehicles, are not uncontested. Such debates are aired on social media, but he prefers to “stay positive.” He has not really noticed a lot of HINKU activity in his own community, but would be willing to engage if the activity concerns his own area of expertise, buildings, or “some kind of practical solutions” for his and neighbors’ everyday life, like ridesharing.

Teo (pseudonym) represents a more active approach to climate: he is seriously concerned about climate change and believes that everyone should contribute as much as they can. He had been concerned even before the launch of HINKU in 2008, saying this is perhaps because he has always tended to think about the big picture. The fact that the municipality engaged has provided him: “a vision of better world, even after my times.” He feels that it is every person’s responsibility to engage:

Even though it seems like many people are saying no, others are not participating, and large countries are not participating, but no, it isn’t necessary that way: everyone participates and needs to participate…. Thinking about someone who isn’t doing their bit right now doesn’t lead you anywhere. Yes, it is worth doing, and in Finland we have understood a lot and in many ways, and other countries will start doing more and more of it, and [international?] agreements will be more binding and broader.

HINKU has helped Teo find other people who are similarly concerned. It has also provided concrete ways for engagement. Among many other activities, he has been active in the local homeowners’ association for years. HINKU turned out to be a fruitful way to boost the activities of the homeowners’ association, while providing a venue for people to find out about HINKU and get engaged with it. The association (like many others) had been slowly declining, given that younger people “are not so eager to get involved and sit at meetings.” HINKU had served as a way to provide new content and get new, younger people involved.

Teo found it quite natural to get involved in HINKU since he had been a builder, mainly involved in building single-family homes:

We always pored over those energy issues when building those houses, with the homeowners, we pored over heating systems, and what kinds of walls we should make and what kinds of roofs. Of course, there are building codes to follow, but there is also scope for making one’s own decisions. So, I have been involved in energy issues since the 1980s and 1990s.

After his home municipality joined HINKU, Teo was involved in several activities and the homeowners’ association became a central organizer of various events. These included “open homes walks” visiting homes that had installed renewable energy solutions. When asked about actions that have been particularly rewarding, Teo fondly remembers an event that attracted over 100 people and showcased some original solutions, such as an air-water heat pump designed by the homeowner and a pellet heating system at a local school, and which was also featured in a large regional newspaper. The best event, however, was for joint procurement of solar panels (i.e., a campaign for building a buyer group, and collectively tendering for larger numbers of customers at once):

That really made a splash, the joint procurement thing, which was organized at the old crafts school, and where there were 160 people present, and a local expert from Lappeenranta [a town at the other side of Finland] was explaining how you do it.

In addition to the practical focus of the event, and the impressive number of participants, this event was also important in Teo’s view because it led to a record number of solar panels being installed in the municipality, and it was later followed by another joint procurement event. Teo feels this was particularly rewarding since local people have continued to invest in solar panels for several years, and they have started to become a visible feature in the townscape.

Teo has also been involved in other activities that are not building-related, such as a low-carbon lifestyle experimentation workshop series, where he started trying out vegan food options, among others. Yet the activities that engage a wide membership from the community and contribute to a feeling of joint progress (such as collective events attracting large numbers of participants, the visibility of solar panels, and visibility in the regional press) were mentioned by Teo as the most rewarding, and as things that people like to discuss in a positive tone, when running into him in town. Even though Teo concedes that there are different views on climate policy in the municipality, he says that people always speak to him positively and encouragingly when meeting face-to-face.

4.2 Affordances of HINKU in contrast to non-localized climate policy

It was difficult to discuss local opposition to climate policy with the participants, irrespective of what their own views were. It is possible that participants were concerned that it would project a “backward” image if some of the locals were to be revealed as climate skeptics. Even though other research (Nousiainen et al., 2022) suggests that there are controversies over climate action within the HINKU municipalities, the interviewees were very circumspect about the topic. They did admit that people might have different opinions, but that they “had not really noticed this so much” in their own municipality. This approach to avoiding polarization, and even downplaying any polarizing remarks, is also visible for example in the local Facebook group of the Mynämäki municipality, which is carefully moderated to avoid the polarization visible on many other social media sites (e.g., Chen et al., 2021). This phenomenon is open to many kinds of interpretations, but our previous observation [reference omitted for review] suggests one mechanism: in a small locality, everyone is dependent on the support of other locals, and hence avoids voicing views that might antagonize others. This can have both positive and negative impacts on the debate, but the positive side is that people tend to avoid openly criticizing the efforts of others.

The interviews indicated that participants appreciate improvements to the local building stock and infrastructure that have resulted from local climate action (and this is corroborated by our previous, wider set of interviews [reference removed for review]). These investments serve to modernize small communities that would otherwise be peripheral or declining, as well as provide cost savings. Some comments suggest that participants tend to compare their own locality with other, larger ones, and are happy to notice if their own locality is “keeping abreast” or even getting ahead. One of the interviewees, Teo, was particularly proud of the fact that his own municipality was well ahead of the rest of the country in installing solar panels. Indeed, municipal officials in the HINKU network have emphasized the importance of climate action for place branding, i.e., providing the municipality a positive reputation (Nousiainen et al., 2022). Nousiainen et al. (2022) also note that the HINKU municipalities’ communication style tended to emphasize positivity, focusing more on the availability of local mitigation solutions rather than on amplifying the risks of climate change.

HINKU activities in the small participating municipalities have focused on embodied practices and competence, rather than abstract scientific knowledge and general political debate (Jalas et al., 2017). Participating in HINKU has thus been about doing things and learning new skills, rather than worrying about environmental catastrophes. Exemplars have been found close by, such as neighbors presenting their heating systems investments to each other at “open homes walks.” This also means that some locals have been able to help and advise each other, and thus feel they are competent actors in a climate action context.

Energy retrofits and renewable energy installations also provide an “opening” for people with a background in the construction sector to engage in climate action with their own expertise and experience. Whereas national climate policy advice for citizens tends to focus on actions like “give up your car,” “move into a smaller dwelling” and “try being a vegan for a year” (Sitra, 2021), local activities have focused on modernizing the building stock via “energy evenings” focusing on energy renovations and renewable energy installations. Similarly, local newspapers have highlighted improvements made in local buildings (e.g., heat pump installations, solar collectors, solar panels and the use of local waste heat), as well as featured local residents and installers engaged in this work. Through small-scale, step-by-step experimentation, some participants have even developed an interest in other kinds of action (such as the example of Teo experimenting with vegan food).

A vignette from a local event serves to highlight how HINKU activities can involve people based on their competencies and interests, rather than a shared view on climate policy. As part of our participant observation, colleagues and I were attending an energy event in 2014 at one of the municipalities, and had suggested that solar collector self-building courses might be a nice activity. A teacher from a local vocational school had been recruited to provide these courses, and in preparation, had attended a course himself. He gave a speech at the event to advertise the course, and I was a bit worried that he did not explain what solar collectors were, but rather emphasized the process of constructing a solar collector, and especially the kinds of new welding materials use in the process. My concerns were unfounded, however, since 20 people immediately lined up to fill all available spaces in the course, happily talking and joking while queuing. While anecdotal, this incident suggests that this local vocational teacher understood the participants’ interests much better than I, the outside observer, did: participants were not so concerned about renewable energy, but instead, interested in applying (and perhaps improving) a familiar skill, welding, in a group of likeminded people.

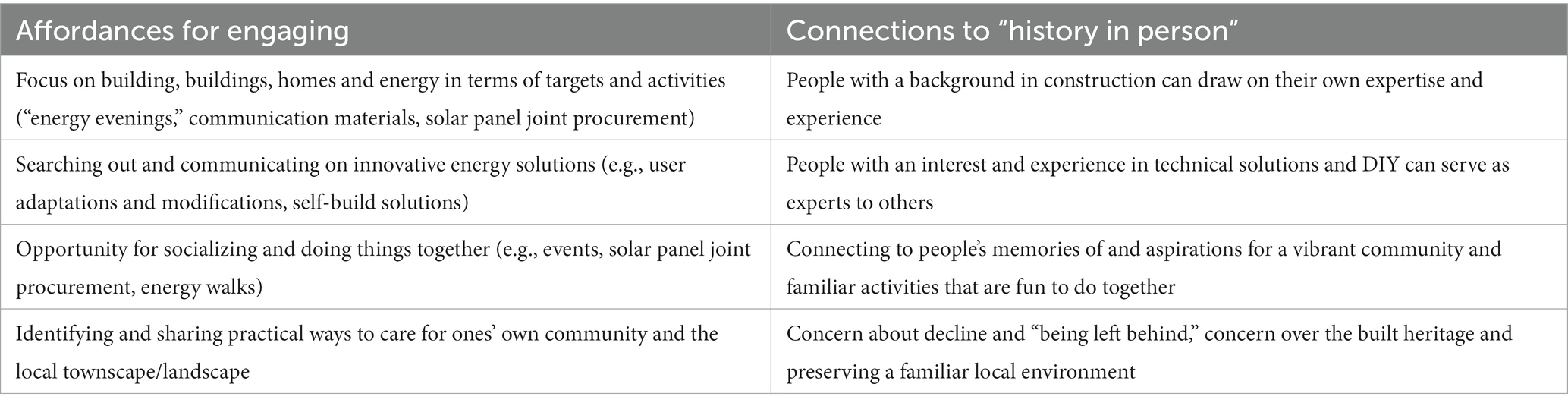

Based on the interviews, as well as extensive fieldwork and a review of the local press and other media, certain affordances can be identified in HINKU which connect with the life histories of people who are not the “usual suspects” in climate activism (Table 3). They are not the core focus of the program, which is more targeted at municipal administrations, but alongside municipal buildings, HINKU has evolved to encourage and support energy actions in the home (Kopsakangas-Savolainen and Juutinen, 2013). In this way, it has also managed to engage people with a background in the construction sector. This can, of course, lead to new employment and business opportunities, but that aspect was not highlighted as the main one in the interviews. The main aspect was the opportunity to be an expert, and contribute from one’s own experience and competences, to join other similar people in activities that are fun, and to take care of one’s own community, in particular, the local townscape, which is at risk of decline (e.g., empty shopfronts) due to a lack of investment.

Table 3. Affordances in HINKU for engaging with climate change mitigation and their connections to participants’ life histories.

5 Discussion and conclusions

5.1 Summary and contribution of the findings

Creation of a climate identity occurs in socially and culturally constructed contexts of interaction, where particular roles and characters are recognized. For the men with a background in construction work, HINKU’s focus on building retrofit created a “figured world” where their occupational competence gave them a respected role in local climate mitigation, for example, one where they could be turned to for advice. It has also created a set of social arenas (e.g., “energy evenings”) where people with similar backgrounds and upbringings and similar everyday valuations (even though political leanings can vary) come together to discuss concrete solutions for climate mitigation. This allowed at least one of the participants to develop a strong identity as a person working to combat climate change. For others, it served as a way to develop “sensible” arguments for engaging (i.e., improving the local environment, technological modernization), even while they were not quite convinced about the possibilities or best means to mitigate climate change via local action. This perspective suggests that while we need to accept that a negotiation of identities is always involved in politics (Mouffe, 1995), a broadening of the constituency working for the climate transition requires a flexible approach to identity, and an understanding that we are individuals exactly because we can host multiple identities. Some of these identities can help to find common cause in practical solutions.

Following Holland (2003), HINKU can be seen as a site where individuals – alone and together – improvise solutions to identity dilemmas. Climate action entails such dilemmas, since rural people tend to perceive climate communications as placing the blame on “ordinary people” (Lehtonen et al., 2020). Yet the interview data illustrates how HINKU provides sites for “improvisations” (Holland et al., 1998; Holland, 2003), where participants reform themselves as individuals and collectives drawing on cultural resources from their own past and that of their communities. Local associations are one such resource: they have existing aims, memberships and operating cultures. Climate policy can either connect with such cultures, or remain foreign or even antagonistic to them. Work identities are another cultural resource that helps build connections to climate mitigation. In particular, the construction work that the interviewees engage in (or have engaged in) serves as a practice where they can make a positive contribution by introducing and disseminating new solutions or technologies on the basis of their existing occupational knowledge, skill and experience.

The present study contributes one small empirical example to the emerging literature that searches for alternatives to a “top-down” and paternalist way of communicating about the urgency of climate change (e.g., Patterson, 2022). Unlike Holland (2003) environmental controversy about hunting, the present study illustrates a context and “social world” where rural people can get involved in climate action (even if they do disagree about hunting, based on the opinion pieces in the local press). Meyer (2008) called for a “populist” take on climate change mitigation, and the small practical improvements accomplished in the studied HINKU municipalities serve as one take on what such “populism” might entail: engaging people on the basis of their experience, finding ways in which they can work together in an enjoyable atmosphere, and producing concrete results that give pride and serve to preserve and even modernize the community, thus holding merit even in the eyes of people who are not convinced about the need for ambitious local climate policy. In this way, “unlikely” participants in climate action can gain respect from their peers for their contributions, on their own terms. This is in the line of MacArthur and Matthewman (2018) understanding of populist resistance, even though the “alternatives” in this case are self-built or local modifications and combinations of existing technologies. Moreover, the present study emphasizes the engaging nature of embodied practices, such as that of construction and the making of things, as a way for new participants to engage in climate action through competent, socially acceptable forms of participation. And it integrates the notion of “fun” by Wilk (2022), while acknowledging that fun can mean different things to different people depending on their backgrounds and interests.

Lucas and Warman (2018) emphasize the importance of sub-politics, i.e., associations between groups that cut across conventional political divides, in the resolution of environmental controversies. The results of the present study show one way in which such sub-politics can emerge: around construction work and the different but complementary competencies of people skilled in such work. People working on a construction site can very well have different political views, but they share (largely) similar views on the project they are working on. People with very different political views can share a concern about rural decline, and even if they might disagree on the solutions to such decline, they may well agree on concrete achievements like local investments and improvements in the townscape. Hence, the present study suggests that sub-politics that support climate action can be found on a very small, personal and practical scale, for example, in shared or complementary occupational interests and competencies, or shared concerns for a small section of the landscape.

What then are socio-cultural affordances (Kaaronen, 2017) for engaging in climate action? They are, of course, different for different people and in different situations. Abstracting from the particularities of my case, one could say that affordances: (1) accept and welcome participants’ own characteristic life histories and lifestyles, (2) build on and respect participants’ experience and embodied competence and give them room to appear as experts, (3) engage people in practices that are familiar enough not to produce anxiety but stimulating enough to be “fun,” (4) produce small but visible achievements that are acknowledged as such by both participants and onlookers. These are perhaps not so surprising in the context of promoting local climate action (e.g., Middlemiss, 2010; Steele et al., 2021), but have not been previously discussed in the context of “identity wars” related to climate policies. Socio-cultural affordances for climate action can be “populist” in Meyer (2008) usage of the term, and “sub-political” (Lucas and Warman, 2018) by focusing on solutions to climate change that build on characteristic material conditions, embodied competences and everyday material concerns that are shared within the community.

5.2 Limitations and further research

The present study has several limitations. It builds on limited and somewhat fragmented data. There are certainly people living in the HINKU carbon-neutral municipalities who have a different view on climate policy, on the HINKU program and its implications. There are most likely also middle-aged and elderly men working in construction who have different views, and it would be important to interview a larger sample of the relevant target group. However, the results of this study can use used to develop an interview scheme that captures different aspects of the program than have been studied until now. There is also more work to do to tease out and further operationalize the concepts related to identification as social practice. I have also focused more on the positive side of identification with climate action; further work might highlight more cases than that described by Holland (2003) where the lack of possibilities to build a positive identity can lead to sentiments that are mobilized against climate protection. The central contribution is an application of Holland and Lave (2001) way of investigating identities in terms of sites and practices where identities are improvised, i.e., where individuals encounter practices that help them either revise or solidify certain aspects of their identities.

Moreover, many different groups of people might feel marginalized from climate mitigation actions. In a global context, middle-aged men in rural Finland could even be seen as privileged in economic, political and gender terms. Less privileged groups can include people with a working-class background (and not only men) (Anantharaman et al., 2019), communities of color (Graff et al., 2018), low-income earners (Anantharaman, 2018), indigenous peoples (MacArthur and Matthewman, 2018) and many others. The present study has not focused on economic injustices, or even procedural injustices in climate action and energy transitions, even though there are many examples of these kinds of injustices (Schlosberg and Collins, 2014). Instead, I have focused on identification as a social practice, and on ways in which people might feel included and thus gain a foothold in climate action. Given the number of different kinds of other groups who can be excluded from climate action, this study merely scratches the surface of the problem. Other groups most likely have different ways of being included or excluded, but the perspective of identification as social practice can provide a way to explore other cases as well.

5.3 Conclusion

Efforts to engage new and different individuals and communities in combatting climate change might draw implications from the perspective of identification as social practice and the notion of cultural affordances. The argument is that people negotiate identities, and opportunities for positive identification with climate action arise when people can draw on embodied experiences of being able to engage competently in practices that are socially acceptable in their communities. In this context, cultural affordances are the opportunities that particular forms of climate communication or action offer for such engagement.

It is obvious that such opportunities for engagement are different for different individuals and communities. Yet, in general terms, culturally affording forms of climate action would be characterized as ones that (1) welcome and accept participants’ life histories, appearances and lifestyles; (2) build on and respect participants’ experience and allow them to appear as competent experts; (3) engage people in practices that are familiar but stimulating for them; and (4) produce small but visible achievements that are acknowledged as such by both participants and onlookers, thus providing active participants with positive feedback from their peers. This seeming simplicity, however, masks a serious challenge since it requires significant face-to-face interaction, engagement in people’s everyday contexts and concerns with a respectful orientation and willingness to learn, and a long-term commitment to improve people’s circumstances while mitigating climate change. Such engagement helps to pay attention to the kinds of “figured worlds” that climate mitigation policy creates, and to how accessible they are to different groups and people.

Such an approach is probably insufficient for reaching the deep and urgent cuts that we need in greenhouse gas emissions. Steep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions are probably not reachable simply through actions that are fun and engaging. However, in democracies that are dependent on popular support, culturally affording first steps are likely to offer a better path toward mitigating climate change than does antagonizing people who do not fit expectations of what an environmentalist should be like.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the [patients/ participants OR patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin] was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This study was completed with financial support by the Academy of Finland, grant number 333556.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2023.1197885/full#supplementary-material

References

Anantharaman, M. (2018). Critical sustainable consumption: a research agenda. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 8, 553–561. doi: 10.1007/s13412-018-0487-4

Anantharaman, M., Kennedy, E. H., Middlemiss, L., and Bradbury, S. (2019). “Who participates in community-based sustainable consumption projects and why does it matter? A constructively critical approach” in Power and politics in sustainable consumption research and practice. eds. C. Isenhour and M. Martiskainen (London and New York: Routledge)

Anderson, J. (2010). From ‘zombies’ to ‘coyotes’: environmentalism where we are. Env. Polit. 19, 973–991. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2010.518684

Batel, S., and Devine-Wright, P. (2017). Energy colonialism and the role of the global in local responses to new energy infrastructures in the UK: a critical and exploratory empirical analysis. Antipode 49, 3–22. doi: 10.1111/anti.12261

Bosch, S., and Schmidt, M. (2020). Wonderland of technology? How energy landscapes reveal inequalities and injustices of the German Energiewende. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 70:101733. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101733

Boucher, J. L., Kwan, G. T., Ottoboni, G. R., and McCaffrey, M. S. (2021). From the suites to the streets: examining the range of behaviors and attitudes of international climate activists. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 72:101866. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101866

Brulle, R. J., and Norgaard, K. M. (2019). Avoiding cultural trauma: climate change and social inertia. Env. Polit. 28, 886–908. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2018.1562138

Bulkeley, H., Paterson, M., and Stripple, J. (Eds.). (2016). Towards a cultural politics of climate change: devices, desires and dissent. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Carbon Neutral Finland (2023) Hinku network - towards carbon neutral municipalities. Available at:https://www.hiilineutraalisuomi.fi/en-US/Hinku.

Chatterji, A. K., and Toffel, M. W. (2019). Assessing the impact of CEO activism. Organ. Environ. 32, 159–185. doi: 10.1177/1086026619848144

Chen, T. H. Y., Salloum, A., Gronow, A., Ylä-Anttila, T., and Kivelä, M. (2021). Polarization of climate politics results from partisan sorting: evidence from Finnish Twittersphere. Glob. Environ. Chang. 71:102348. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102348

Davidson, D. J., Rollins, C., Lefsrud, L., Anders, S., and Hamann, A. (2019). Just don’t call it climate change: climate-skeptic farmer adoption of climate-mitigative practices. Environ. Res. Lett. 14:034015. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aafa30

Doyle, J., Farrell, N., and Goodman, M. K. (2017). Celebrities and climate change. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Erkamo, S. (2019). Ilmastomuutosdenialismi ja Antirefleksiivisyys: vertaileva analyysi ilmastonmuutoskeskustelusta Euroopassa. Turku: Turun yliopisto

Evans, J., and Karvonen, A. (2014). ‘Give me a laboratory and I will lower your carbon footprint!’—urban laboratories and the governance of low-carbon futures. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 38, 413–430. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12077

Evans, G., and Phelan, L. (2016). Transition to a post-carbon society: linking environmental justice and just transition discourses. Energy Policy 99, 329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2016.05.003

Flemsæter, F., Bjørkhaug, H., and Brobakk, J. (2018). Farmers as climate citizens. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 61, 2050–2066. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2017.1381075

Fraune, C., and Knodt, M. (2018). Sustainable energy transformations in an age of populism, post-truth politics, and local resistance. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 43, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2018.05.029

Fukuyama, F. (2018). Identity: The demand for dignity and the politics of resentment. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Gardner, C. J., Thierry, A., Rowlandson, W., and Steinberger, J. K. (2021). From publications to public actions: the role of universities in facilitating academic advocacy and activism in the climate and ecological emergency. Front. sustain. 2:42. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.679019

Graff, M., Carley, S., and Konisky, D. M. (2018). Stakeholder perceptions of the United States energy transition: local-level dynamics and community responses to national politics and policy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 43, 144–157. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2018.05.017

Harper, K., Steger, T., and Filčák, R. (2009). Environmental justice and Roma communities in central and Eastern Europe. Environ. Policy Gov. 19, 251–268. doi: 10.1002/eet.511

Heiskanen, E., Jalas, M., Rinkinen, J., and Tainio, P. (2015). The local community as a “low-carbon lab”: promises and perils. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 14, 149–164. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2014.08.001

Hobson, K. (2013). On the making of the environmental citizen. Env. Polit. 22, 56–72. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2013.755388

Hodson, M., Burrai, E., and Barlow, C. (2016). Remaking the material fabric of the city: ‘alternative’low carbon spaces of transformation or continuity? Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 18, 128–146. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2015.06.001

Hodson, M., and Marvin, S. (2007). Understanding the role of the national exemplar in constructing ‘strategic glurbanization’. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 31, 303–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2007.00733.x

Holland, D. (2003). Multiple identities in practice: on the dilemmas of being a hunter and an environmentalist in the USA. Eur. J. Archaeol. 42, 31–49.

Holland, D. (2010). “Symbolic worlds in time/spaces of practice” in Symbolic transformation: The mind in movement through culture and society. ed. B. Wagoner (London and New York: Routledge), 269–283.

Holland, D., and Lachicotte, W. (2007). “Vygotsky, Mead, and the new sociocultural studies of identity” in The Cambridge companion to Vygotsky. eds. H. Daniels, M. Cole, and J. V. Wertsch (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 101–135.

Holland, D., and Lave, J. (2001). History in person: Enduring struggles, contentious practice, intimate identities, pp. 3–33. SAR Press. Oxford

Holland, D., Lachicotte, W., Jr, Skinner, D., and Cain, C. (1998). Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

HS (2019) HS:n kysely: Lähes puolet suomalaisista epäilee ilmastopuheita (opinion poll of the leading national daily newspaper Helsingin Sanomat: almost half of Finns doubtful about climate arguments). Available at:https://www.hs.fi/politiikka/art-2000006249808.html

Jalas, M., Hyysalo, S., Heiskanen, E., Lovio, R., Nissinen, A., Mattinen, M., et al. (2017). Everyday experimentation in energy transition: a practice-theoretical view. J. Clean. Prod. 169, 77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.03.034

Jalas, M., Kuusi, H., and Heiskanen, E. (2014). Self-building courses of solar heat collectors as sources of consumer empowerment and local embedding of sustainable energy technology. Sci. Technol. Stud. 27, 76–96. doi: 10.23987/sts.55335

Kaaronen, R. O. (2017). Affording sustainability: adopting a theory of affordances as a guiding heuristic for environmental policy. Front. Psychol. 8:1974. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01974

Kanger, L., and Schot, J. (2019). Deep transitions: theorizing the long-term patterns of socio-technical change. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 32, 7–21. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2018.07.006

Kennedy, E. H., and Givens, J. E. (2019). Eco-habitus or eco-powerlessness? Examining environmental concern across social class. Sociol. Perspect. 62, 646–667. doi: 10.1177/0731121419836966

Kopsakangas-Savolainen, M., and Juutinen, A. (2013). Energy consumption and savings: a survey-based study of Finnish households. J. Environ. Econ. Policy 2, 71–92. doi: 10.1080/21606544.2012.755758

Kungl, G. (2015). Stewards or sticklers for change? Incumbent energy providers and the politics of the German energy transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 8, 13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2015.04.009

Lehtonen, T., Niemi, MK., Perälä, A., Pitkänen, V., and Westinen, J. (2020). Ilmassa ristivetoa: Löytyykö yhteinen ymmärräys. Loppuraportti. Available at:https://www.univaasa.fi/fi/tutkimus/hankkeet/ilmassa-ristivetoa-loytyyko-yhteinen-ymmarrys

Lübke, C. (2022). Socioeconomic roots of climate change denial and uncertainty among the European population. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 38, 153–168. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcab035

Lucas, C. H., and Davison, A. (2019). Not ‘getting on the bandwagon’: when climate change is a matter of unconcern. Environ. Plan. E: Nat. Space 2, 129–149. doi: 10.1177/2514848618818763

Lucas, C., and Warman, R. (2018). Disrupting polarized discourses: can we get out of the ruts of environmental conflicts? Environ. Plan. C: Polit. Space 36, 987–1005. doi: 10.1177/2399654418772843

MacArthur, J., and Matthewman, S. (2018). Populist resistance and alternative transitions: indigenous ownership of energy infrastructure in Aotearoa New Zealand. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 43, 16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2018.05.009

Matschoss, K., and Heiskanen, E. (2017). Making it experimental in several ways: the work of intermediaries in raising the ambition level in local climate initiatives. J. Clean. Prod. 169, 85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.03.037

McCright, A. M., Dunlap, R. E., and Marquart-Pyatt, S. T. (2016). Political ideology and views about climate change in the European Union. Env. Polit. 25, 338–358. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2015.1090371

Meyer, J. M. (2008). Populism, paternalism and the state of environmentalism in the US. Env. Polit. 17, 219–236. doi: 10.1080/09644010801936149

Middlemiss, L. (2010). Reframing individual responsibility for sustainable consumption: lessons from environmental justice and ecological citizenship. Environ. Values 19, 147–167. doi: 10.3197/096327110X12699420220518

Moss, T., Becker, S., and Naumann, M. (2015). Whose energy transition is it, anyway? Organisation and ownership of the Energiewende in villages, cities and regions. Local Environ. 20, 1547–1563. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2014.915799

Mouffe, C. (1995). Post-Marxism: democracy and identity. Environ. Plan. D: Soc. Space 13, 259–265. doi: 10.1068/d130259

Neij, L., and Heiskanen, E. (2021). Municipal climate mitigation policy and policy learning-a review. J. Clean. Prod. 317:128348. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128348

Noth, F., and Tonzer, L. (2022). Understanding climate activism: who participates in climate marches such as “Fridays for future” and what can we learn from it? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 84:102360. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2021.102360

Nousiainen, N., Riekkinen, V., and Meriläinen, T. (2022). Municipal climate communication as a tool in amplifying local climate action and developing a place brand. Environ. Res. Commun. 4:125003. doi: 10.1088/2515-7620/aca1fe

Ostertag, S. F., and Ortiz, D. G. (2017). Can social media use produce enduring social ties? Affordances and the case of Katrina bloggers. Qual. Sociol. 40, 59–82. doi: 10.1007/s11133-016-9346-3

Patterson, J. J. (2022). Culture and identity in climate policy. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 13:e765. doi: 10.1002/wcc.765

Ramstead, M. J., Veissière, S. P., and Kirmayer, L. J. (2016). Cultural affordances: scaffolding local worlds through shared intentionality and regimes of attention. Front. Psychol. 7:1090. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01090

Schlosberg, D., and Collins, L. B. (2014). From environmental to climate justice: climate change and the discourse of environmental justice. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 5, 359–374. doi: 10.1002/wcc.275

Seyfang, G., Hielscher, S., Hargreaves, T., Martiskainen, M., and Smith, A. (2013) A grassroots sustainable energy niche? Reflections on community energy case studies. Norwich: Science, Society and Sustainability Research Group.

Sitra (2021). Catalyse action: lifestyle test. Available at:https://www.sitra.fi/en/cases/carbon-footprint-calculator/

Steele, W., Hillier, J., MacCallum, D., Byrne, J., and Houston, D. (2021). “Bringing missing actors to the Table” in Quiet activism (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 43–63.

Wieland, S. M. (2010). Ideal selves as resources for the situated practice of identity. Manag. Commun. Q. 24, 503–528. doi: 10.1177/0893318910374938

Keywords: climate policy, local climate action, rural, identity, situated social practice

Citation: Heiskanen E (2023) Engaging “unusual suspects” in climate action: cultural affordances for diverse competences and improvised identities. Front. Sustain. 4:1197885. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2023.1197885

Edited by:

Benno Werlen, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, GermanyReviewed by:

Anders Rhiger Hansen, Aalborg University Copenhagen, DenmarkEerika Albrecht, University of Eastern Finland, Finland

Miriam R. Aczel, University of California, Berkeley, United States

Copyright © 2023 Heiskanen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eva Heiskanen, ZXZhLmhlaXNrYW5lbkBoZWxzaW5raS5maQ==

Eva Heiskanen

Eva Heiskanen