- 1Department of Education, Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

- 2Helsinki Institute of Sustainability Science, Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

- 3Department of Economics and Management, Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

Food packaging has an essential function in the contemporary food supply chain, but it is also a key source of municipal solid waste. The ability to package foods has changed eating habits as takeaway coffees, bottled water, and fast food have become more commonplace. Although the task of recycling packaging materials falls on the consumer who is guided to sort the waste and ensure it is taken to a recycling bin, the consumer perspectives of the mutually constitutive market device–consumer relationship are not yet well-known. This paper studies how food shoppers are constructing their relationship with packaging in their everyday lives, and especially how their moral considerations construct the relationship with sustainability and materiality of packaging. Based on the analysis of consumer interviews, the study argues that consumers' perspective on packaging use is renegotiated during their continuous relationship with packaging. Food packaging acts as a political market device that evokes morally charged consumer perspectives throughout different stages of consumption processes beyond the supermarket. In the first stage, the consumer is mainly focused on finding the products that have already become a part of their daily routine and the materiality of packaging oftentimes remains unseen. Tensions arise as packaging is both a source of frustration, and a necessary element of managing food consumption. After eating the food product, the packaging turns into waste and the consumer “becomes aware” of the packaging materials and several negative interpretations arise. Finally, packaging waste becomes morally charged: it invites consumers to partake in recycling work and evokes environmental anxieties. The results indicate that consumers often have an uneasy, cyclical relationship with packaging use.

1. Introduction

Single-use food packaging has become a ubiquitous part of modern life, and as a consequence, more and more packaging waste is produced, and thrown out (e.g., Müller and Süßbauer, 2022). Thus, food packaging is consumed more and more and a large part of it ends up in the bin after one use (e.g., Müller and Süßbauer, 2022). The increasing use of single-use plastic products in packaging consequences is seen in the accumulation of marine litter in oceans, rivers and beaches around the world (Sattlegger et al., 2020). Until the mid-1900's, products were mostly packaged in glass or metal. After the invention of thermoplastics, plastics became widely applied for food packaging as well (Hawkins, 2018). Innovations in plastic coatings and types allowed for new routines from takeaway coffees to plastic-wrapped ready-meals at the supermarket. Therefore, the social norms of eating were, and continue to be, altered by the wide adoption of plastics in the food and beverage industry (Hawkins, 2012). The increased use of single-use packaging been driven by changes in mobility, the COVID-19 pandemic and demographic change (Simoens et al., 2022, p. 15).

Hawkins (2012) argues that packaging serves as a market device, which creates and facilitates economic activity. Hawkins (2011) uses the plastic water bottle as an example—the emergence of packaged water created new modes of branding and inflated the importance of supermarket design and product placement. However, the consumer perspectives of the mutually constitutive market device–consumer relationship (Fuentes and Samsioe, 2021) are not yet well-known. In the self-service supermarket, a package serves a key function: it helps the consumer make sense of the store and its selection. It can make a product stand out from a shelf. Moreover, packaging helps in navigating choice: to distinguish perceived low- and high-quality products (Cochoy and Grandclément-Chaffy, 2005). Packaging, according to Sattlegger (2021) conveys notions of freshness and fullness to the consumer, helping to constitute the supermarket as a venue.

As scholars in consumption studies have argued, processes of consumption are more continuous than the act of buying alone (e.g., Warde, 2005; Evans, 2019). In the consumption of food, packaging travels with the consumer across the phases of purchasing, “using-up” (De Solier, 2013, p. 10) and disposal. Here, disposal refers to getting rid of things as a part of a consuming cycle, it is both a temporal and spatial category (e.g., Hetherington, 2004; Gregson et al., 2007; Evans, 2019). Indeed, Müller and Süßbauer (2022) have analyzed how disposable food packaging circulates through food consumption practices, including shopping, eating and disposing as well as planning, storing, preparing and transporting. However, oftentimes the point of selling is emphasized as the key moment of consumption (e.g., Korczynski, 2005). Packaging does reach consumers at ‘critical moments' of decision-making, which inflates its importance in marketing especially (Chandon, 2013; Kauppinen-Räisänen et al., 2020). Packaging claims are an example of this phenomenon, as environmental labels have been found to influence consumers (Ketelsen et al., 2020). Consumers do have considerations beyond this, however. Consumers may consider their personal moral or ethical views (Monnot et al., 2019). For example, what is considered waste, is a social ordering process and disposal is an ethical activity (Hetherington, 2004). This is one way to conceptualize waste (Moore, 2012). As De Solier (2013) argues, it is important to study the ways in which people consider the moral aspects of their consumption.

With the use of single-use packaging is increasing amounts of municipal solid waste. In her work, Hawkins (2012) argues that the growing amounts of waste changed the meaning of recycling. Recycling became a means to manage the stream of consumer waste, instead of a way of reusing scarce resources. Consumers are aware of the notion of circular economy and material recycling especially regarding plastic (Rhein and Schmid, 2020; Otto et al., 2021). This recognition on the part of the consumer is crucial—consumer engagement with consumption work is an essential part of a circular economy, and the flow of materials in the circular system (Wheeler and Glucksmann, 2015; Hobson et al., 2021). Consumers adopt an identity of a “recycler,” letting their actions at home be shaped by the responsibility over the end-of-life of materials (Hawkins, 2012). Acting as a recycler is not always simple, however. As Nemat et al. (2019) have noted, confusion regarding recycling have reduced adherence to sorting waste. Thus, consumers are expected to be able to perform recycling work in a correct way to enhance the circular economy but are not necessarily given enough information to act on.

This study draws from the idea of packaging as a market device (Cochoy and Grandclément-Chaffy, 2005; Hawkins, 2011, 2012; Fuentes and Fuentes, 2017; Fuentes and Samsioe, 2021). As Hawkins (2012) argues food packaging acts as a device that shapes the economic processes that surround it, whether it be changed habits around food consumption or new modes of product branding. The literature suggests that market devices could give consumers more capacity to act and shape their practices. This could then be used to accelerate sustainability transformations (Cochoy and Mallard, 2018; Fuentes and Samsioe, 2021, p. 493). Similarly, Moore (2012) points out that conceptualizations of waste define the political possibilities that it carries. We focus on changing consumer perspectives with a special interest in the moral considerations of consumption (De Solier, 2013). Thus, in this study, we examine how the consumer perceives the relationship between their packaging use and everyday sustainability from their routines of shopping to their duties as recyclers or waste-makers. We aim to understand how consumers negotiate the contentious relationships between their consumption and waste-creation throughout the processes of purchasing, using-up, and disposing. Food packaging provides an interesting medium for a study such as this, as it acts as an interface between the product and the consumer at the store and beyond.

2. The tension of consuming food and acting as a food package recycler

As Wilk (2014) observes, consumption is rarely driven by immediate practical goals or objectives, but rather practices that define a person's social and individual identity and their position as a moral person. Consuming is pictured as hedonistic “modernism” with its values of instant gratification and pleasure (Sulkunen, 2009; De Solier, 2013). Thus, Wilk (2014) argues that one characteristic of consumer cultures is the desire for the moral balancing of virtue and excess (also frugality and indulgence). Thus, for example, acting as a shopper has allowed for enjoying the pleasures of consumption and the aesthetic pleasures of eating (De Solier, 2013). However, today, being a responsible consumer (e.g., striving toward sustainable consumption) is seen as an intrinsic part of household management and environmental citizenship (Moisander, 2007; Huttunen and Autio, 2010). Acting as responsible recycler of waste is one example of this. Consequently, consuming activities are affected by diverse norms and values and consumers negotiate their relationships within these values as shoppers at the supermarket and at home, work or on the go as users of a product and as recyclers of waste. It is notable that food is a distinctive material object and differs from other objects—food is “used up” rather instantly (De Solier, 2013). Thus, packaging waste is generated on a daily basis as a result of everyday food consumption (Müller and Süßbauer, 2022).

Although food consumption is characterized by rigid routines, the current social norms around eating have developed over time and food packaging has played an important part in the process. As Hawkins (2012) points out, packaging as a political market device is more than a singular package itself—it is a system of multiple material actors that has developed historically over time, especially after World War II (see also Muniesa et al., 2007; Fuentes and Samsioe, 2021). Analysis of food packaging as market devices has revealed how they facilitate the emergence of various economic practices, such as branding, pricing, and supermarket placement (Hawkins, 2011, 2012). Cochoy and Grandclément-Chaffy (2005, p. 647) use oatmeal as an example of food as a branded product with additional meanings and performances attributed to it; the creation of a quality oatmeal is dependent on the ability to communicate product differences to consumers. Indeed, packaging assigns qualities to food, e.g., convenience, hygiene or freshness (Hawkins, 2018; Evans and Mylan, 2019).

However, Cochoy (2007, p. 120–121) argues that although consumers think they are going to the store to buy food, “the shopper” never reaches the product in the modern supermarket. Consumers buy brands and images, not products. Furthermore, Cochoy and Grandclément-Chaffy (2005, p. 646) noticed that packaging is often the material that “we see but don't see,” which makes packaging a controversial object. As Muniesa et al. (2007) have noted, the shopping cart is a material device, but it is also a “market device” which redefines what shopping is about, what shoppers are, and what they can do. Through acting as a shopper in the store or the supermarket and by consuming food and consequently food packaging we take care of ourselves and our close ones (e.g., Miller, 1998, p. 11)—thus acting as virtuous consumers.

Another major task of packaging as a political market device, according to Hawkins (2012), is the making of “the recycler:” a waste management system together with the performative role of packaging has created “the recycler” identity position for consumers (Hawkins, 2012, p. 78). Along with packaging, political action enters mundane everyday settings. Consumer encounters with packaging waste are influenced by moral and political capacities as they are given a lot of value-laden information about what is the “right thing to do” (Hawkins, 2012, p. 79). However, to embrace the new subjectivity of a virtuous recycling citizen who requalifies empty food packaging as resource, requires a significant amount of work (and/or care) in household waste management (Hawkins, 2012; Fuentes and Samsioe, 2021). According to Wheeler and Glucksmann (2015, p. 556) recycling tends to be portrayed as a “conscious green act” and it is linked into domestic routines. Thus, food packaging has become a political device by engaging households in wider networks where they have ethical concerns for the environment and the afterlife of packaging (Hawkins, 2012, p. 80).

It seems that for consumers recycling practices are guided by hierarchies of packaging materials. According to Steenis et al. (2017) paper-based packaging is valued as the most sustainable choice of packaging material due to its recyclability (i.e., biodegradability). In addition, glass and bioplastics were also perceived as sustainable compared to plastic and metal, which were considered less environmentally friendly (see also Lindh et al., 2016). What is more, De Feo et al. (2022) showcased consumers to perceive glass bottles as sustainable. In contrast, plastics were thought of as less environmentally friendly. Plastic consumption has been linked to severe environmental issues (e.g., Sattlegger et al., 2020). As Hawkins (2018) argues, plastic is a ubiquitous material that has paved the way for multiple new food packages and food products (Fuentes et al., 2019). People appreciate and routinely use plastic despite awareness of the associated problems (Heidbreder et al., 2019). For example, consumers have questioned overpackaging. Elgaaïed-Gambier (2016) study showcases that consumers think excessive material use is generating bigger amounts of household waste, which is perceived as an environmentally unfriendly practice (i.e., wasting of natural resources). The notion of overpackaging is not straightforward, however, as at the same time consumers tend to associate “overpackaging” with better quality and higher-end products.

As Hawkins (2012, p. 80) argues, the empty package has become a morally charged object capable of slowing things down and posing questions to the consumer: where will this end up? Thus, as Hawkins (2012, p. 68) continues with her argument, food packaging is a crucial participant in constituting new forms of environmental citizenship. However, acting as responsible consumer is a challenging position that requires meeting conflicting expectations (e.g., Moisander, 2007). Wilk (2001) uses food as an example of how the pleasures of consumption are associated with pain and sacrifice, and he refers to Nichter and Nichter (1991) suggesting that the cycle of sin and guilt forms the basic rhythm of consumer culture. De Solier (2013, p. 11) also claims that consumption is a game between pleasure and anxiety, spending and thrift.

When consumers are buying, using and disposing of food packaging they are taking stands and revealing the prevailing moral considerations that guide routinized consumption. These moral considerations and juxtaposed decisions create tensions around how to act or do the right thing amidst the global waste crisis. As Wheeler (2019) has suggested, by listening to consumers' everyday reflections on the handling of their waste, we can understand how the moral demands of recycling are negotiated with other everyday demands and life experiences related to perceptions of what practices should be valued. In this study, we use empirical data to analyse the use of food packaging in the context of sustainability.

3. Methods and materials

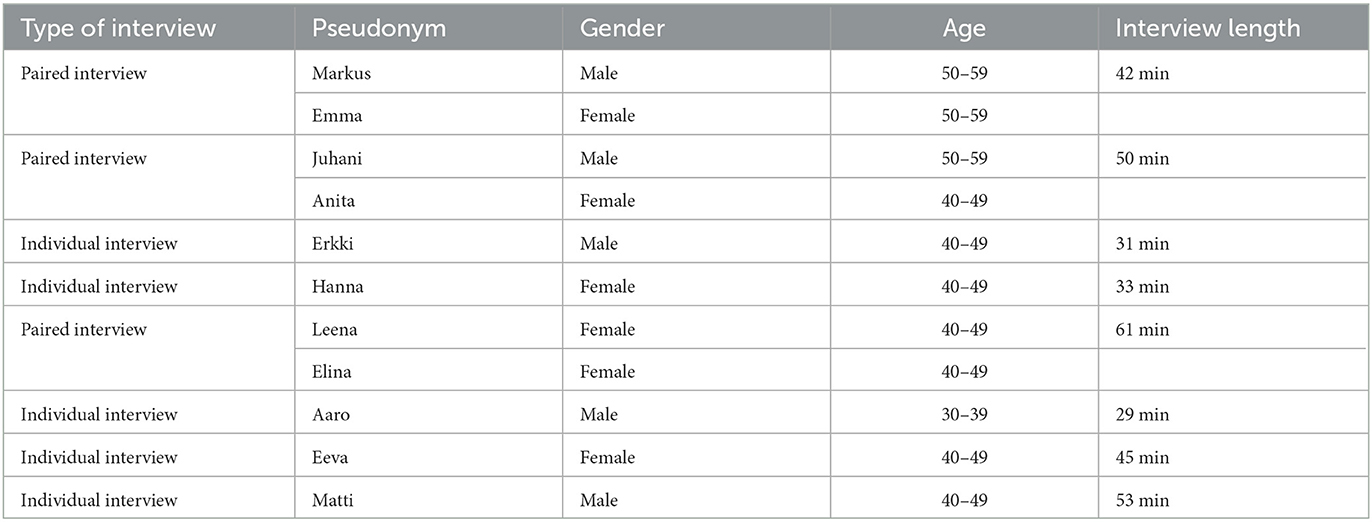

In order to study consumers' moral considerations regarding food packaging, we collected qualitative data, through which we analyse consumers' views on food and food packaging as part of their consumer agency. The data utilized in this study is a part of a larger interview data set (n = 51). These interviews aimed to map out consumer views on food packaging, cosmetics packaging and clothing, with a focus on the meanings attributed to materials and related notions of sustainability. Thus, the interview structure included discussion on packaging materials and everyday routines consumers have around packaging use. For this study, we first chose the sample of interviews that includes the interviews with discussion on food packaging (n = 23) including the small group interviews (n = 12), the paired interviews (n = 6) and the individual interviews (n = 5). We focus on food packages because those produce waste more rapidly than (e.g., De Solier, 2013), for example, in cosmetics packaging.

In the initial round of analysis to the food packaging related views of the interviewees were organized under categories of purchase, use and recycling of packaging. At this point in the analysis, the three-pronged notion of the consumer as a shopper, an eater, and a recycler emerged. In the next phase of analysis, we focused on these positions and cyclical relationships (purchase, use, disposal) for the use of packaging. At that point we realized that the paired interviews differentiated from group interviews in some extent because of the couples shared experiences concerning grocery shopping and recycling of packaging waste. The individual interviews were similar, focusing more on personal experiences than the group interviews. Therefore, for the close reading of the data, we narrowed down our focus to couple and individual interviews, where the purchase and use of food and the recycling of waste were positioned at the household level.

The final data set under in-depth analysis consists of three paired interviews (n = 6) and individual interviews (n = 5; see Table 1). As argued above paired interview participants share similar experience, same event or phenomenon, in interview they can confirm, clarify, correct or argue these experiences which adds richness to data (Dale et al., 2021). In this study the participants in paired interviews were family members. The interviewees were Finnish consumers aged 35–58 years. Half of the interviewees were male, half female. Due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in 2020, the interviews were conducted remotely using the video conferencing software Zoom. Interviews took between 30 to 80 min, and they were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participation was voluntary and interviewees were given the opportunity to withdraw at any time (Creswell, 2013). Interviewees were made aware of the overall purpose of the study. The anonymity of the participants has been ensured throughout the study. Names in Table 1 are invented pseudonyms.

Participants were recruited through snowball sampling (Geddes et al., 2018). This method of sampling is dependent on the social networks of the researcher and the participant (Noy, 2008). Data collection began by author X's recruiting of participants. Due to the pandemic, recruiting participants proved challenging. Therefore, the social networks of the authors were utilized. This limits the sample, as network-based convenience sampling can affect the data based on, for example, gender or occupational status (Noy, 2008).

The interviews followed a semi-structured guide. Semi-structured interviews allow for probing questions and focusing on emergent themes during the interview (Krueger and Casey, 2014). The leading theme of discussion on food packaging was consumer interactions with packaging in different contexts (e.g., at home, or in the supermarket). Additional topics included packaging function and sustainability. The discussions on packaging proved challenging at times, as shopping for food and handling food packaging are mundane everyday activities consumers pay little attention to.

The limited sample size affects the generalizability of the results of this study. However, due to challenges caused by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, made the recruitment of participants more challenging. However, our aim was to use the method of interviewing as a means to produce cultural knowledge (Moisander and Valtonen, 2006) and describe the related phenomena of food packaging, sustainability, moralities and waste. Rather than collecting information, our aim was to examine how these phenomena appear in how people talk and make sense of their everyday lives (Moisander and Valtonen, 2006).

The analysis aims at understanding the moral considerations of consumers that they make sense of the tensions in interacting with food packaging. After the first thematization of the data, in the iterative and interpretive analysis (Moisander and Valtonen, 2006), we recognized the cyclically changing consumer perspectives each carrying own morally charged views in relationship with packaging. The data was organized accordingly (see Figure 1). Figure 1 illustrates our approach: here, consumer identity changes from a shopper, to an eater and finally to the identity of a recycler. As a political market device, food packaging co-constitutes these consumer positions.

Figure 1. Changing consumer perspectives relationship with packaging and examples of moral considerations.

4. Results and discussion

This chapter is organized as follows: Section 4.1 focuses on consumers as shoppers and eaters. Transitioning between these identities is smooth, as packaging serves the product, marketing aims, or the user. The materiality of packaging oftentimes remains unseen. Tensions arise as packaging is both a source of frustration, and a necessary element of managing food consumption—an element you can oftentimes forgive for the frustration it caused. Consumers fall into roughly one of two camps—some do not pay any attention to the packaging materials as they are focused on what the packaging contains. In contrast, some are tuned into packaging to the point that any changes to, for example, packaging design, can disrupt their daily routines.

In Section 4.2 we zoom in on the transition from an eater to a recycler and the moment when packaging, essentially, becomes waste. We discuss how interviewees make sense of packaging materials after they have used up or disposed of the food the packaging once contained. With this moment, several negative interpretations arise. Even though these moments are quite mundane, the becoming of waste seems to catch interviewees by surprise.

Finally, in Section 4.3, we analyze the responsibilities that packaging places on the consumer. Here, the consumer steps into the role of the recycler. Packaging becomes morally charged (as described by Hawkins, 2012), and consumers are invited to take part in the work of recycling. These consumer-recyclers feel the anxieties of suboptimal recycling solutions or become frustrated when fellow consumer-recyclers are not engaging in the task of recycling as well.

4.1. The tension of seeing and not seeing food packaging

Packaging is claimed to be an effective tool that interacts with the consumer in the retail environment at the point of purchase (Kauppinen-Räisänen et al., 2020). Cochoy and Grandclément-Chaffy (2005, p. 649) point out that unpackaged products may even bother some consumers because they are not used to handling them. In addition to packaging, social norms and practices guide consumers' actions in the store even though shoppers themselves might think that consumption is oriented by practical objectives, such as buying bread or vegetables. The shoppers buy brands and images (Cochoy, 2007). For the interviewed consumer-shoppers packaging remains either a secondary concern as exemplified in the following quote: “the looks of the packaging aren't that important when you're looking for a product” (Erkki, M, 48) or they pay attention to packaging while shopping, using packaging to guide their appreciation of food they would like to eat and what they value in packaging:

“... and there's some, like take a milk carton for example, it might tell you about the ethics of the product or the treatment of the animals or where the animals live, also like with egg cartons and such” (Matti, M, 40).

“... if I really think about it, I probably choose, like, things that have cardboard that has like a printed text instead of like a see-through plastic container” (Hanna, F, 48).

As these quotes exemplify, Matti and Hanna discuss how packaging helps them in realizing a moral objective of their consumption, whether it be animal welfare or using less plastic. Erkki, however, considers packaging to be less important than the product he is looking for. Here, not seeing the packaging itself does not present an ethical or moral question to him. However, through ethical and aesthetic values consumers negotiate what forms of consuming are good or bad, and how they should live and act (Moisander and Valtonen, 2006). Thus, the food package can act as moral a market device; for Hanna, packaging reminds her of goals related to reducing plastic use, and for Matti, packaging evokes considerations of animal welfare.

Cochoy and Grandclément-Chaffy (2005) claim that packaging is the “material we see but don't see” (p. 646) making packaging “invisible” for consumers. As Hetherington (2004) argues, especially at disposal visibility is connected to the simultaneous categories of presence/absence. Our interviewees pay attention to materials and signs of packaging, and it is done through a frame of finding a product that has been integrated into their consumption routines:

“Yes it does matter that the packaging looks like it is nice to buy from an ethical standpoint, like it looks eco-friendly” (Matti, M, 40).

The routinized nature of food consumption (Fuentes and Samsioe, 2021) become visible when interviewees appear to have established routines of food consumption with products they stick with:

“Then when we've found a product for us, then that's it (–) no matter the packaging happens to look like” (Emma, F, 43).

“I tend to buy a lot of the stuff I bought last week as well.” (Matti, M, 40).

Consumers have bypassed the phase of examining and paying attention to the packaging itself and they rely on their shopping routines. When packaging disrupts routines, it become a source of frustration:

“Nothing is as enraging as when there's like a milk carton or something, and the producer has wanted to gain a bigger market share and change the design and then the product's difficult to find from the store.” (Juhani, M, 55).

This suggests that packaging, if integrated into everyday eating habits, is not a major concern to consumers. In these occasions, food packaging acquires the function of “finding what I came to buy” (Elina, F, 43). Here packaging helps consumers make out differences between products in the supermarket (Cochoy and Grandclément-Chaffy, 2005). The product remains the priority, as illustrated by the following quote:

“As long as the product works and is tasty, then the packaging, you can forgive a lot about it” (Juhani, M, 55).

In this quote, Juhani describes a hierarchy between the product and the packaging. Juhani is able to ignore the issues he may see in the packaging, if his primary need of eating is satisfied by the product. The forgiving resonates also with the observations of Cochoy (2007, p. 120–121) as he argues that in the market the shopper never reaches the product, because on an “impassable paper, a glass or a plastic barrier,” but has to act in these given circumstances. In other words, even if the consumer thinks she/he is buying food, i.e., the contents of the package—this happens via the package.

Consumers do not necessarily pay attention to the packaging and sustainability aspects when purchasing items, and thus the negotiation of sustainability and acting as a recycler takes place when the product turns into “waste” after using it. In the following, we analyze the transformation of food packaging into waste.

4.2. Realization of food packaging as waste: efficient simple packaging vs. wasteful overpackaging

In a grocery store the consumer negotiates and takes a moral stand on whether or not to make a purchase. After eating matters change: food packaging becomes waste. Then moral considerations change from eating to waste. In the following quote, Markus describes how he is moving on from shopping practices to thinking about waste. Here, the realization of the quantity of packaging waste occurs gradually:

“...you get like, a pre-prepped portion of sushi or something where everything is in its own plastic container. But it's not like you think about it while buying it, you think about it at home.” (Markus, age 49).

After eating, one has to deal with packaging waste (Hawkins, 2012). In spite of moral considerations of plastic and packaging waste, consumer-eaters are likely to end up with both as a side effect of food consumption. The leftover packaging materials invite consumers to dispose of them. Even though disposal is an ordinary routine, consumers may not think of packaging as waste until they are at home:

“Sometimes you just think when you open something at home that it probably could've done with less plastic.” (Markus, M, 49).

This morally charged view of wastefulness emerges most clearly in the context of ready-meals, takeaway restaurant meals, or pre-prepared salads:

“I did notice, now that I have been ordering takeout because of COVID-19 that I got a bunch of single-use containers. So like, no one had considered the ecological aspects of takeout food.” (Anita, F, 49).

These types of foods are often categorized as convenient, and they have higher amounts of packaging material compared to, for example, dry staple ingredients. The interviewees often consider packaging through a juxtaposition of efficient simple packaging and wasteful overpackaging. This clear moral framing between the “good” kind of packaging, and the wasteful suggest a moral framing to the matter. The interviewees seem to link packaging waste in with Wilk's (2014) notion of virtue and excess. Here, the interviewee describes the aftermath of a prepared salad:

“As someone whose eaten a lot of ready-made salads, when you finish one you get quite a large pile of plastic (–) how could it be made more efficiently, so that you could have the salad without creating a bunch of plastic” (Aaro, M, 35).

The interviewees often felt the need to make sense of waste, and referred to the concept of “overpackaging” several times. Here, overpackaging was often mentioned in the context of a perceived overuse of plastic or the inclusion of several types of materials:

“If I accidentally buy something that's way overpackaged well at least I won't buy it again if that package has like bunch of plastic wrappers inside of it” (Leena, F, 49).

“it is a bit upsetting, if a packaging kind of includes one container after another, so they're way overpackaged” (Hanna, F, 48).

As a solution to wastefulness, consumers mentioned circular economy:

“I might actually buy more packaged meats of fish because packaging isn't just waste, those materials can be utilized again” (Erkki, M, 48).

Here the interviewee places the product above the looks and design packaging but does have morally charged considerations of waste upon the packaging. The choice to purchase prepackaged meat or fish is justified with the chance to re-use the packaging materials in the circular economy. A well-designed packaging, for the interviewees, would “be as simple as possible, and produce as little waste as possible” (Anita, F, 49) as an interviewee described when asked about how they would describe well-designed food packaging. Realization of sustainability (i.e., non-sustainability) aspects of food packaging means awakening to either problematizing the amount of packing materials, use of plastic or using less material in packaging.

4.3. Morally charged food packaging as waste: recycler's anxiety, work, and frustration

As has been previously discussed above, the rationales behind why we recycle have changed from the notion of resource-wise consumption to being an active solution in the modern waste crisis (Hawkins, 2012). According to Hawkins (2012), packaging has created new norms around cultural and economic routines. As one finishes a ready-made salad, they are encountering a “morally charged object” (p. 80) and are directed toward sorting and recycling the material rather than throwing it out with the mixed waste (2012). Similar notions emerged in discussions with the interviewees. The materials that were mentioned under this theme were of a wider variety.

Interviewees described how they managed the packaging waste they produced in their everyday lives. This included things such as the separating and sorting of materials in multi-material packaging, and going out of their way to make sure the sorted waste gets to a recycling bin. Interviewee described how he walks to a recycling point even though it was not close to his home:

“You kind of surprisingly want to take the recycling if you've gone through the trouble to collect and sort them. All of that work goes to waste if you throw everything in the same bin.” (Matti, M, 40).

Interestingly, the interviewee describes recycling as work that can be wasted if the sorted waste is not taken to recycling. Here the interviewee recognizes his participation in consumption work that is essential in the circular economy, which has been noted by Wheeler and Glucksmann (2015), for example.

In her work, Hawkins (2012, p. 78) describes the emergence of a “recycler” in connection with the increased use of food packaging. The accumulation of packaging waste requires consumers to change their domestic routines in order to accommodate the growing amounts of discarded material. In the following interviewee described challenges with multi-material packaging in particular when asked about their views on sustainable food packaging:

“[Sustainable packaging] should be easy to recycle. I don't know if... And it should be easy to recycle, not like when you have to rip everything into three parts and figure out where to put each bit” (Emma F 43).

During the interview, her partner Markus mentioned also that sorting is occasionally tricky due to a lack of information:

“...one type of plastic wasn't allowed in the recycling bin. And it's unclear why they couldn't just write in bright color if you cannot put it in with recycling.” (Markus, M, 49).

Recycling is often inconvenient for those who were interviewed. For some, it is the distance between their home and recycling bin:

“you have to travel three kilometers to recycle plastics (–). Carton recycling is another thing, it's the same three kilometers to recycle that” (Aaro, M, 35).

The same interviewee mentioned the space recycling required in their home:

“a plastics bin takes a whole drawer in the kitchen if you actually want to sort it, it takes quite a bit of space.” (Aaro, M, 35).

Another interviewee recycled everything very thoroughly, as they had communal recycling bins in their apartment building:

“We sort the materials we have the opportunity sort at our building” (Markus, M, 49).

These quotes illustrate the multiple ways in which a consumer may deal with the “morally charged objects” Hawkins (2012, p. 80) talks about.

The interviewee hinted at perceived areal differences between recycling habits:

“When I visit my friends in [neighboring town] I'm always stunned because they don't, my friends don't recycle. Nobody [in that town] recycles. They have like, one rubbish bin where they put everything. I feel like they've never even heard of recycling. (—) And for me, I feel horrible if I put food waste in the same bin as mixed waste” (Hanna, F, 48).

Here, the interviewee also mentions significant negative feelings if food waste is not composted. In a sense, this quote illustrates how consumers negotiate their position as recyclers. While food consumption is fairly routinized, the work of recycling may cause painful tension between of one's own actions and frustration with others' lack of action, consequently leading into moralizing others. The grappling consumers do in order to manage their recycling work could also in a sense, explain how patterns of non-participation emerge. One could, potentially, simply function based on the routine of not partaking in the work of recycling.

Interviewees also mentioned that their habits with the consumption of packaged foods had become laxer with the improvements in recycling:

“Especially now that recycling has become easier, and you know you can recycle plastics at home and metals too and whatever you want to recycle, it's not that big of a deal [to buy packaged food] anymore because you know the materials circular and you know they'll be utilized for something” (Hanna, F, 48).

In the above quote, it appears that the consumer has a strong sense of righteousness about the circular economy, and it is used as a reasoning behind consumption choices. Something that used to be unecological can now be done as material reuse is a perceived possibility.

The interviewees here describe both the challenges and the burdens of recycling packaging materials. At the same time, however, this opportunity to recycle even drove their consumption of packaged goods. While consumers act differently in the store, as they have different reactions to packaging, many still go to lengths to recycle the packaging they have. While the aftermath of eating—packaging waste—does not necessarily direct them at the store, it certainly affects their everyday lives and the efforts they make to foster sustainable habits.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we focus on consumers' relationships with food packaging, and the tensions that emerge when thinking about food packaging, food consumption, everyday routines and sustainability. Although there has been scholarly interest in how consumers view the sustainability of different packaging materials (e.g., Lindh et al., 2016; Steenis et al., 2017; De Feo et al., 2022), the relationships consumers construct with packaging in their everyday lives has gained less attention (Müller and Süßbauer, 2022) - especially how they are renegotiating their relationships with the sustainability and materiality of packaging through a moral lens.

We found that consumers have an uneasy, cyclical relationship with packaging use (see Figure 1). On one hand, packaging is essential in everyday food consumption as packaged products are integrated into daily routines. The routinized, mundane side of packaging highlights how packaging is both visible and invisible at the same time (Cochoy and Grandclément-Chaffy, 2005). From the perspective of a routinized food shopper the packaging may remain unseen or issues such as overpackaging may be forgiven easily. Morally, the shopper is conducting the virtuous act of consumption, interacting mainly with the references instead of actual materials of packaging (Miller, 1998; Cochoy, 2007). Whereas, on the other hand, especially as recyclers (Hawkins, 2012) consumers feel frustrated and anxious about packaging use and disposal (Hetherington, 2004). Packaging turns to mean waste and work for consumers—the political aspects arise (Moore, 2012). Consumers are recruited to work for a circular economy at home (Wheeler and Glucksmann, 2015) which in the case of our interviewees meant time spent sorting waste at home, and taking time to visit a recycling point to dispose of packaging waste. From this perspective, the morally charged object of food packaging as waste induces negatively loaded meanings. Thus, large amounts of packaging waste, plastics in particular, appear as “sinful” (Wilk, 2001) compared to simple packaging solutions.

The study showcases how the daily routine of food shopping initiates a cyclical process in which as shoppers, eaters and recyclers they negotiate and re-negotiate their relationship with the materiality and sustainability of (food) packaging. With routinized food consumption, consumers know how to act according to existing moral considerations, that is: doing “the right thing” (Hawkins, 2012). However, in the process of less routinized recycling, moral conflicts arise, and environmental anxieties emerge. After eating the food, only the leftovers of packaging waste remain and thus, consumers must act as recyclers until the cycle of food consumption is re-activated, and consumers are seeking enjoyment and gratification again (e.g., Sulkunen, 2009; De Solier, 2013) and so on. However, this cyclical relationship with packaging use suggests that consumers also consider sustainability aspects of food packaging while acting as shoppers (Figure 1). Responsible buying and recycling are therefore not only a conscious green act (e.g., Wheeler and Glucksmann, 2015) but can also guide consumers to participate in the recycling work of the circular economy.

There are limitations to this study. The context and sample—Finnish consumers—are both very specific. Therefore, the generalizability of these results is limited and requires further research. It is also important to remember that packaging in and of itself has been an element of reshaping eating patterns and domestic habits. Thus, there are multiple possible beneficial avenues of future research to continue to develop the role of packaging in people's everyday lives. For example, research approaches that focus on the act of recycling could identify recycler types and analyze the related processes of disposal and divestment (Evans, 2019). Moreover, critical approaches on how packaging has participated in creating current food consumption routines would require in-depth case studies with socio-historical analysis and cultural comparison.

As the collection of data was implemented amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the recruitment of interviewees was affected. Some potential participants were unable to join the study at the early stages of the pandemic, as their possibilities to utilize new technologies such as video calling software were limited. The participants lived mainly in the Helsinki metropolitan area, which was another consequence of the convenience sampling and many interviewees recommended their neighbors and friends as potential participants. Therefore, the sample is narrow.

In the future, it would be beneficial to examine the potential impacts of gender, age, and geographical location in connection with packaging use and recycling behavior. The aim of this study was to elucidate how consumers make sense of food packaging and packaging waste, rather than to provide cross-cutting evidence on consumer actions which is why these factors are not controlled for in the sample.

This study contributes to the literature of seeing consumption as a continuous process (Warde, 2005; Evans, 2019) where consumers are either taking or are guided to take multiple positions during the process of consuming food and negotiate emerging tensions with food packaging. Thus, this study has shown that consumers have multiple moral considerations while they interact with packaging and construct relationships with it. The meanings associated with packaging are morally charged, which requires work and constant negotiation from the consumer when acting in the position of a shopper, an eater, a waste-maker and a recycler. Packaging as a morally charged object asks the consumer to engage in recycling work. Furthermore, despite how food consumption is fairly routinized, it seems that recycling work at home is still more challenging fitting into the routines of the recycling system. Since it is likely that food packaging is here to stay, it is important to understand the growing requirements placed on consumers and their participation in the circular economy. Due to the task of recycling and being held responsible for making sure waste can be made valuable again, consumers are assigned a morally charged task. Thus, we developed consumer understanding related to packaging and packaging waste management issues.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

LR, EK, and MA: study conceptualization. SS: data collection. LR: analysis and writing the first draft. All authors participated in writing, revising, and editing the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This article was written as a part of the Biocolour (Bio-based Dyes and Pigments for Colour Palette) research project (grant number 327178). The project was funded by the Strategic Research Council.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Chandon, P. (2013). How package design and packaged-based marketing claims lead to overeating. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Pol. 35, 7–31. doi: 10.1093/aepp/pps028

Cochoy, F. (2007). A sociology of market-things: on tending the garden of choices in mass retailing. Sociol. Rev. 55(2_suppl), 109–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2007.00732.x

Cochoy, F., and Grandclément-Chaffy, C. (2005). “Publicizing goldilocks' choice at the supermarket: the political work of shopping packs, carts and talk,” in Making Things Public, eds B. Latour and P. Weibel (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 646–657.

Cochoy, F., and Mallard, A. (2018). “Another consumer culture theory. An ANT look at consumption or how ‘market things' help ‘cultivate' consumers,” in The SAGE Handbook of Consumer Culture, eds O. Kravets, A. Venkatesh, S. Miles, and P. Maclaran (London: SAGE), 384–403.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing From Five Approaches. London: SAGE.

Dale, N. F., Johns, R., and Walsh, M. J. (2021). “That's not true!” paired interviews as a method for contemporaneous moderation of self-reporting on a shared service experience. J. Hospital. Tour. Manag. 49, 580–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.11.010

De Feo, G., Ferrara, C., and Minichini, F. (2022). Comparison between the perceived and actual environmental sustainability of beverage packagings in glass, plastic, and aluminium. J. Clean. Product. 333, 130158. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.130158

De Solier, I. (2013). Making the self in a material world: food and moralities of consumption. Cult. Stud. Rev. 19, 9–27. doi: 10.5130/csr.v19i1.3079

Elgaaïed-Gambier, L. (2016). Who buys overpackaged grocery products and why? Understanding consumers' reactions to overpackaging in the food sector. J. Bus. Ethics 135, 683–698. doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2491-2

Evans, D. M. (2019). What is consumption, where has it been going, and does it still matter? Sociol. Rev. 67, 499–517. doi: 10.1177/0038026118764028

Evans, D. M., and Mylan, J. (2019). Market coordination and the making of conventions: qualities, consumption and sustainability in the agro-food industry. Econ. Soc. 48, 426–449. doi: 10.1080/03085147.2019.1620026

Fuentes, C., Enarsson, P., and Kristoffersson, L. (2019). Unpacking package free shopping: alternative retailing and the reinvention of the practice of shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 50, 258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.05.016

Fuentes, C., and Fuentes, M. (2017). Making a market for alternatives: marketing devices and the qualification of a vegan milk substitute. J. Market. Manag. 33, 529–555. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2017.1328456

Fuentes, C., and Samsioe, E. (2021). Devising food consumption: complex households and the socio-material work of meal box schemes. Consumpt. Markets Cult. 24, 492–511. doi: 10.1080/10253866.2020.1810027

Geddes, A., Parker, C., and Scott, S. (2018). When the snowball fails to roll and the use of ‘horizontal' networking in qualitative social research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 21, 347–358. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2017.1406219

Gregson, N., Metcalfe, A., and Crewe, L. (2007). Identity, mobility, and the throwaway society. Environ. Plan D 25, 682–700. doi: 10.1068/d418t

Hawkins, G. (2011). Packaging water: plastic bottles as market and public devices. Econ. Soc. 40, 534–552. doi: 10.1080/03085147.2011.602295

Hawkins, G. (2012). The performativity of food packaging: market devices, waste crisis and recycling. Sociol. Rev. 60, 66–83. doi: 10.1111/1467-954X.12038

Hawkins, G. (2018). The skin of commerce: governing through plastic food packaging. J. Cult. Econ. 11, 386–403. doi: 10.1080/17530350.2018.1463864

Heidbreder, L. M., Bablok, I., Drews, S., and Menzel, C. (2019). Tackling the plastic problem: a review on perceptions, behaviors, and interventions. Sci. Tot. Environ. 668, 1077–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.437

Hetherington, K. (2004). Secondhandedness: consumption, disposal, and absent presence. Environ. Plan. D 22, 157–173. doi: 10.1068/d315t

Hobson, K., Holmes, H., Welch, D., Wheeler, K., and Wieser, H. (2021). Consumption Work in the circular economy: a research agenda. J. Clean. Product. 321, 128969. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128969

Huttunen, K., and Autio, M. (2010). Consumer ethoses in Finnish consumer life stories—agrarianism, economism and green consumerism. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 34, 146–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-6431.2009.00835.x

Kauppinen-Räisänen H. van der Merwe D. Bosman M. (2020). Global OTC pharmaceutical packaging with a local touch. Int. J. Retail Distribut. Manag. 48, 727–748. doi: 10.1108/IJRDM-05-2019-0164

Ketelsen, M., Janssen, M., and Hamm, U. (2020). Consumers' response to environmentally-friendly food packaging—a systematic review. J. Clean. Product. 254, 120123. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120123

Korczynski, M. (2005). The point of selling: capitalism, consumption and contradictions. Organization 12, 69–88. doi: 10.1177/1350508405048577

Krueger, R. A., and Casey, M. A. (2014). Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. London: SAGE Publications.

Lindh, H., Olsson, A., and Williams, H. (2016). Consumer perceptions of food packaging: contributing to or counteracting environmentally sustainable development? Packaging Technol. Sci. 29, 3–23. doi: 10.1002/pts.2184

Moisander, J. (2007). Motivational complexity of green consumerism. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 31, 404–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-6431.2007.00586.x

Moisander, J., and Valtonen, A. (2006). Qualitative Marketing Research: A Cultural Perspective. London: SAGE Publications.

Monnot, E., Reniou, F., Parguel, B., and Elgaaied-Gambier, L. (2019). “Thinking outside the packaging box”: should brands consider store shelf context when eliminating overpackaging? J. Bus. Ethics 154, 355–370. doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3439-0

Moore, S. A. (2012). Garbage matters: Concepts in new geographies of waste. Prog. Hum. Geograph. 36, 780–799. doi: 10.1177/0309132512437077

Müller, A., and Süßbauer, E. (2022). Disposable but indispensable: The role of packaging in everyday food consumption. Euro. J. Cult. Polit. Sociol. 9, 299–325 doi: 10.1080/23254823.2022.2107158

Muniesa, F., Millo, Y., and Callon, M. (2007). An introduction to market devices. Sociol. Rev. 55, 1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2007.00727.x

Nemat, B., Razzaghi, M., Bolton, K., and Rousta, K. (2019). The role of food packaging design in consumer recycling behavior—a literature review. Sustainability 11, 4350. doi: 10.3390/su11164350

Nichter, M., and Nichter, M. (1991). Hype and weight. Medical Anthropol. 13, 249–284. doi: 10.1080/01459740.1991.9966051

Noy, C. (2008). Sampling knowledge: the hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 11, 327–344. doi: 10.1080/13645570701401305

Otto, S., Strenger, M., Maier-Nöth, A., and Schmid, M. (2021). Food packaging and sustainability—consumer perception vs. correlated scientific facts: a review. J. Clean. Product. 298, 126733. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126733

Rhein, S., and Schmid, M. (2020). Consumers' awareness of plastic packaging: more than just environmental concerns. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 162, 105063. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105063

Sattlegger, L. (2021). Making food manageable – packaging as a code of practice for work practices at the supermarket. J. Contempor. Ethnogr. 50, 341–367. doi: 10.1177/0891241620977635

Sattlegger, L., Stieß, I., Raschewski, L., and Reindl, K. (2020). Plastic packaging, food supply, and everyday life: adopting a social practice perspective in social-ecological research. Nat. Cult. 15, 146–172. doi: 10.3167/nc.2020.150203

Simoens, M. C., Leipold, S., and Fuenfschilling, L. (2022). Locked in unsustainability: Understanding lock-ins and their interactions using the case of food packaging. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 45, 14–29. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2022.08.005

Steenis, N. D., Van Herpen, E., Van der Lans, I. A., Ligthart, T. N., and Van Trijp, H. C. (2017). Consumer response to packaging design: the role of packaging materials and graphics in sustainability perceptions and product evaluations. J. Clean. Product. 162, 286–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.036

Sulkunen, P. (2009). The Saturated Society: Governing Risk and Lifestyles in Consumer Culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Warde, A. (2005). Consumption and theories of practice. J. Consum. Cult. 5, 131–153. doi: 10.1177/1469540505053090

Wheeler, K. (2019). Moral economies of consumption. J. Consum. Cult. 19, 271–288. doi: 10.1177/1469540517729007

Wheeler, K., and Glucksmann, M. (2015). ‘It's kind of saving them a job isn't it?' The consumption work of household recycling. Sociol. Rev. 63, 551–569. doi: 10.1111/1467-954X.12199

Keywords: waste, recycling, morality, market device, sustainability, food packaging, plastic, sustainable food consumption

Citation: Ruippo L, Kylkilahti E, Sekki S and Autio M (2023) “It probably could've done with less plastic” - Consumers' cyclical and uneasy relationship with food packaging. Front. Sustain. 4:1176559. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2023.1176559

Received: 28 February 2023; Accepted: 12 June 2023;

Published: 04 July 2023.

Edited by:

Maria Alzira Pimenta Dinis, Fernando Pessoa University, PortugalReviewed by:

Elisabeth Süßbauer, Technical University of Berlin, GermanyJennifer D. Russell, Virginia Tech, United States

Copyright © 2023 Ruippo, Kylkilahti, Sekki and Autio. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lotta Ruippo, bG90dGEucnVpcHBvJiN4MDAwNDA7aGVsc2lua2kuZmk=

Lotta Ruippo

Lotta Ruippo Eliisa Kylkilahti

Eliisa Kylkilahti Sanna Sekki

Sanna Sekki Minna Autio

Minna Autio