95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. , 10 November 2023

Sec. Sustainable Consumption

Volume 4 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2023.1036666

This article is part of the Research Topic Sustainable Consumption and Care View all 10 articles

Caring for human wellbeing has the potential of offering a powerful narrative for change toward sustainability. A broad body of research confirms that a narrative linking the ideas of a good life (human wellbeing) and of solidarity and justice actually exists, and that this narrative could, if supported and reinforced by convincing concepts, relevant material structures, and coherent action, serve as a societal source of power for sustainability. With a view to providing a theory of human wellbeing that focuses on the responsibility of the community and conceptualizes achieving a good life as a public good and not as a purely individual matter, we developed the Theory of Protected Needs (PN). The Theory of PN is a theory of good life that frames quality of life for individuals as a societal responsibility (but without affecting individual freedom), thus linking the individual and the societal perspective with a view of ensuring life satisfaction of present and future generations. The Theory of PN has been subjected to a representative survey in Switzerland. In the paper, we explore whether the Theory of PN can be empirically confirmed, that is, to what extent the nine needs the theory consists of deserve the status of being protected needs. We present the theory, the empirical criteria that the nine needs have to meet in order to qualify for being protected needs, and the results of the data analysis. These results sum up to an aggregated argument in favor of using the Theory of PN as a fundament to conceptualize sustainability as ‘caring for human wellbeing'. The paper concludes with outlaying further steps both in research and in societal practice. In the Appendix A, the German and French versions of the Theory of PN are first published.

On a fundamental level, sustainability can be approached from two perspectives: by putting environmental protection at the center or by putting the protection of human wellbeing at the center. Research has shown that the second approach is far more promising than the first approach. There is a considerable and diverse body of empirical research backing this statement. Scholars have shown that environmental topics and climate change do not translate into powerful societal narratives because they are not sufficiently linked to people's everyday experiences and concerns about quality of life and justice (e.g., Harich, 2010; Lakoff, 2010; Lejano et al., 2013; Feola, 2014; Gearty et al., 2015; Espinosa et al., 2017; Veland et al., 2018; Han and Ahn, 2020). Other research has pointed out that when no geopolitical crisis is jeopardizing the energy supply, people care less about energy because energy (and other natural resources) is not a category that people normally think with (e.g., Owens and Driffill, 2008; Kaufmann-Hayoz et al., 2012; Bornemann et al., 2018; Sahakian and Bertho, 2018). Still other research has uncovered that people refer to human wellbeing and justice in their dual roles as consumers and citizens in considering, discussing, and assessing sustainability policies (e.g., De Vries and Petersen, 2009; Defila et al., 2018; Di Giulio et al., 2019). And, to give a last example, research investigating the criteria informing the decision making of schools committed to sustainability indicates that a good life (in terms of quality of life) is one of four values that are part of what could turn out to be a “culture of sustainability” (Ruesch Schweizer and Di Giulio, 2016).

There is, in other words, enough and diverse evidence pointing in the same direction: caring for human wellbeing has the potential to offer a powerful narrative for change toward sustainability. This is in line with how the United Nations defines sustainable development: as development that aims at ensuring quality of life for human beings in the present and in the future (e.g., Manstetten, 1996; Di Giulio, 2004; Rauschmayer et al., 2011). This leads to the question of what theory of human wellbeing to adopt (see, e.g., O'Mahony, 2022).

This is the starting point of this paper. We have developed a theory of wellbeing—the Theory of Protected Needs (Di Giulio and Defila, 2020)—that we suggest using in the context of sustainability. The goal of the paper is to explore whether the Theory of Protected Needs can be empirically confirmed, that is, to what extent the nine needs in the theory deserve the status of being protected needs. In the subsequent sections, we will first outline the requirements that a theory of human wellbeing (or quality of life: we use these terms synonymously) should meet to serve as a robust foundation for sustainable development (Section 2). Based on this, we will provide a short introduction to the Theory of Protected Needs, and we will present the empirical criteria that posited needs must meet to qualify as protected needs (Section 3). In Section 4, we will explain the empirical approach we applied to determine whether the nine needs of our theory meet these criteria, and in Section 5, we will report the empirical results. Based on the empirical results, we will discuss the potential of using the Theory of Protected Needs as a foundation for conceptualizing sustainability as ‘caring for human wellbeing' (Section 6). Finally, we will draw some conclusions with a view to further steps both in research and in societal practice (Section 7).

Taking human wellbeing as the goal of sustainable development leads, as stated above, to the subsequent question of how to approach the notion of human wellbeing. Here again there are, on a fundamental level, two options: an approach focusing on the individual and an approach focusing on the community and society. According to the first approach, how quality of life is defined is completely dependent on the individual, that is, on their preferences and values, and how quality of life is achieved also depends on the individual. This approach follows the logic that “everyone is the architect of their own fortune” and leads, if taken to its logical conclusion, to an egoistic approach based on competition. Although the second approach acknowledges that individuals have different conceptions about what exactly wellbeing means to them, it assumes (a) that it is possible to define some constituents of quality of life that are equally important to all human beings, regardless of their personal preferences and values (so-called universals) and (b) that achieving quality of life for individuals is a responsibility shared by society. This approach adopts an ethics of solidarity and is based on collaboration.

Sustainability is not an individual goal but a collective goal, so in contrast to a universalistic approach to defining human wellbeing, an individualistic approach cannot be coherently linked with the idea of sustainable development or with the concomitant notion of collective responsibility. In the context of sustainability, caring for human wellbeing is not primarily an individual duty to perform care work but a societal duty to provide the conditions for people to achieve quality of life. This line of reasoning is backed by empirical evidence. Research shows that when people refer to human wellbeing in considering, discussing, and assessing sustainability policies, they are not primarily thinking of their own lives. Rather, they are linking quality of life to issues such as social justice and solidarity, that is, they are perceiving human wellbeing as a societal responsibility (e.g., Kallbekken and Sælen, 2011; Defila et al., 2018). Thus, for the context of sustainability, a universalistic approach to quality of life should be adopted, an approach that is complemented by an ethics of solidarity and justice (Di Giulio et al., 2012; Fischer et al., 2012; Gough, 2017; emphasized also by O'Mahony, 2022).

Caring for people's wellbeing does not stop at preventing their deaths or at avoiding or eliminating conditions and factors that impair their wellbeing or make it impossible for them to achieve wellbeing. Caring for people's wellbeing rather means providing conditions that make it possible for human beings to achieve quality of life according to their own preferences and values. A theory of human wellbeing suitable for the context of sustainability must therefore provide a salutogenic approach to wellbeing1, safeguard individual freedom, and justify limiting this freedom when individuals' actions are detrimental to the wellbeing of others (in the present or in the future).

In order to answer the question of how to approach the notion of human wellbeing, the last point that needs to be clarified is what is decisive in a salutogenic and universalistic sense with a view to defining quality of life. It goes without saying that quality of life cannot be reduced to single elements such as social relations or personal development but necessitates a comprehensive approach that integrates all the constituents important for human wellbeing. It also goes without saying that a comprehensive and universalistic approach to defining quality of life must be limited with regard to its scope in terms of content and sensitive with regard to changing cultural and historical contexts. For this purpose, it is important to distinguish means and ends in themselves. In a universalistic approach, the constituents of quality of life are ends in themselves that are independent of individuals' age, gender, education, value systems, life situations, and religious, cultural, or national contexts. Means in turn are what people do and make use of in achieving these constituents. From this perspective, resources (such as economic resources or natural resources), services (such as education or health services), infrastructures (such as road systems or systems of provisioning), and societal institutions (such as legal systems or social insurance but also churches) are not constituents of quality of life but means, because they are not ends in themselves. Furthermore, many such means are not universal but linked to specific life situations (e.g., being sick, being unemployed, being a single parent), phases of life (e.g., being a child, being a parent, working), or beliefs, values, and life plans [e.g., being a member of a church, being a member of a party, (not) wanting children]. In other words, for the context of sustainability, quality of life must be defined by naming ends in themselves and not by naming means.

Looking for a salutogenic approach to wellbeing that proceeds from universals and does not focus on means but on constituents of wellbeing leads to a needs approach, because needs approaches are universalistic and salutogenic, and they stress the difference between needs as constituents of quality of life and satisfiers as means to achieving quality of life (e.g., Max-Neef et al., 1991; Jackson et al., 2004; Soper, 2006). There are a considerable number of needs approaches [see, e.g., the compilations provided in Alkire (2007, 2010)]. To qualify for the context of sustainability, a needs approach must meet three criteria (Di Giulio, 2008; Di Giulio et al., 2010, 2012; Di Giulio and Defila, 2020). First, it must be comprehensive and thus not focus, for example, on psychological wellbeing (such as Ryff, 1989; Ryan and Deci, 2000, 2001). Second, it must provide what Soper calls a “thick” theory to be relevant to policy (Soper, 2006, p. 361), so approaches that only provide a short list of undefined needs (e.g., Doyal and Gough, 1991) are less suitable. Finally, it must focus only on needs that a community can be made responsible for, which discards approaches such as the capability approach that focus primarily on the individual, its possibilities, and its freedom (e.g., Nussbaum, 2006; Sen, 2009).

To sum up, viewed through the lens of care, sustainability can be defined as societally acknowledging a comprehensive set of thickly described universal human needs and societally assuming the responsibility to ensure that all human beings are provided with the satisfiers necessary to meet those needs.

Proceeding from what has been said above on the level of the scholarly discourse leads to the question of what human needs should be used in implementing this definition of ‘sustainability as caring for human wellbeing' on a societal level. The quality requirements can be summarized as follows: the set of needs must be universal, salutogenic, and comprehensive; it must provide thick descriptions but not mention specific satisfiers (and not narrow down the needs to specific ways of living); it must be suitable for grounding a societal responsibility in a way that at the same time preserves individual freedom; and it must allow for individual, socio-cultural, and historical adaptation. These are quality dimensions that have to be observed in developing and formulating the needs.

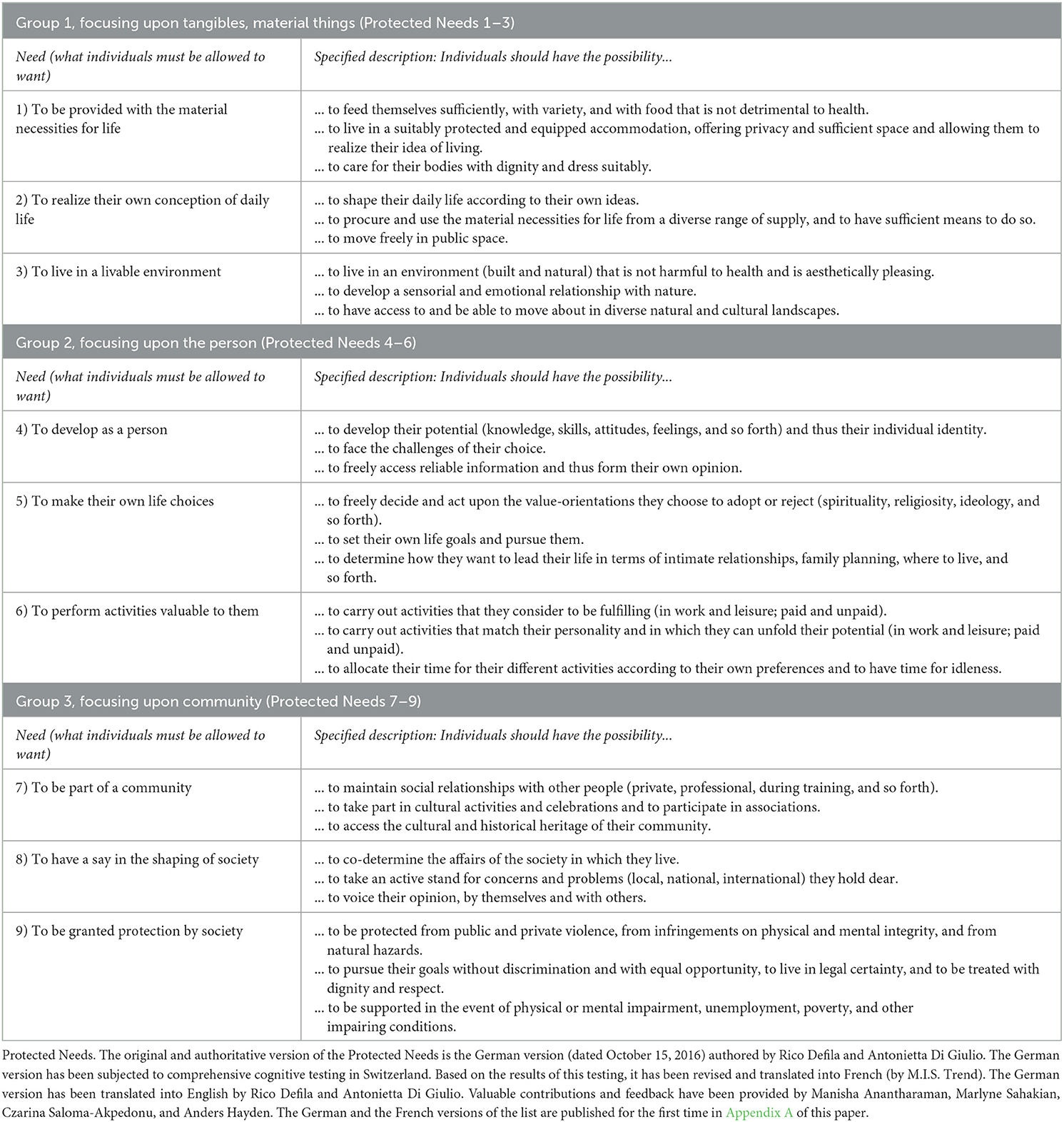

Based on an interdisciplinary literature review2 and in collaboration with an interdisciplinary advisory board3, we developed the Theory of Protected Needs (PN). This theory is informed by the requirements mentioned above and provides a list of needs for use in the context of sustainability (Di Giulio and Defila, 2020). We call them “Protected Needs” because the needs we suggest to use claim to be needs that (1) deserve special protection within and across societies since they are crucial to human wellbeing, and they claim to be, at the same time, (2) needs for which special societal protection is possible, since they are needs that a government or community can reasonably be made responsible for. The Theory of PN provides both universal needs and a thick description of each need. The list of needs in the Theory of PN consists of nine universal needs that are arranged in three groups (Table 1, left column) and are specified by thick descriptions (Table 1, right column). The needs denote what individuals must be allowed to want (left column), and the thick descriptions describe the possibilities individuals should be provided with (right column).4 Concurring with a needs approach, the nine needs on the list of Protected Needs are ends in themselves, that is, they cannot be further reduced (needs “cannot be added up and summarized in a single unit of account”, Gough, 2017) and they are non-substitutable (“one domain of need-satisfaction or objective wellbeing cannot be traded off against another”, Gough, 2017). The nine Protected Needs (PN 1–9) are context sensitive despite being universal: the thick descriptions that have been developed for the Swiss-German context serve as a starting point for the cultural and historical adaptation of the nine needs.

Table 1. The nine needs in the Theory of Protected Needs (Di Giulio and Defila, 2020).

Needs are satiable but through what means they are satisfied and how they translate into actions differs among individuals. In order to allow for individual freedom, the definition of each of the nine needs must allow for a diversity of means (activities, infrastructures, services, products, etc.) that people can draw on in satisfying it. We have empirical evidence that allows us to make indicative conclusions with regard to this requirement of ‘individual freedom and diversity'. The list of Protected Needs has been used in a qualitative investigation in four Asian cities (Chennai, Metro Manila, Shanghai, Singapore) to explore how green public spaces act as satisfiers with regard to these needs. The results show that each of the nine needs allows for a diversity of means that people draw on in satisfying it and that people link a broad diversity of means to one and the same need. The respondents were asked to link their activities in the park to the nine needs, and data analysis showed that a broad diversity of activities serve the same need (Di Giulio et al., 2022). We thus conclude that we have strong empirical indications that all nine needs on the list of Protected Needs allow for individual freedom and diversity in how they are satisfied.

The Theory of PN claims to provide a comprehensive and salutogenic definition of quality of life that is both sound and useful for fleshing out quality of life for the context of sustainability and with a view to grounding responsibilities for individuals, communities, and governments on the subnational, national, international, and global levels. But the Theory of PN claims to provide a definition of quality of life that does not only meet the quality requirements above but can also be practically used in sustainability governance. The Theory of PN must therefore also resonate with people, that is, each of the nine needs must cumulatively meet a set of empirical criteria (hereafter referred to as ‘empirical criteria'):

• Criterion 1—The need is actually experienced by people, and it is a crucial constituent of quality of life: The need is not a theoretical construct, that is, it is possible to identify a “construct of wanting” that corresponds with how the need is defined, and not having the possibility to satisfy the need affects individuals' wellbeing.

• Criterion 2—The need is supra-individual: Experiencing the need is not tied to a specific segment of people. Rather, it is experienced by a diversity of people (this does not imply that all human beings must experience the need or that the need has the same importance for all human beings).

• Criterion 3—The need is perceived as a need that is non-negotiable: The need is perceived to be a crucial, universal, and incontestable constituent of the wellbeing of all humans; that is, the need is not up for negotiation.

• Criterion 4—The need grounds a societal responsibility: The need grounds a sense of ethical obligation to contribute to the possibility of human beings to satisfy this need, and the recipients of this responsibility are present and future generations.

We subjected the list of Protected Needs to a representative survey in Switzerland. The survey served two purposes: we wanted to find out how people react to the nine needs with a view to different dimensions, and we wanted to determine to what extent the nine needs, which were developed by means of a literature analysis and by an interdisciplinary discussion among experts3, can be empirically confirmed with regard to these four criteria.

The guiding question of this paper is to what extent the nine needs on the list of Protected Needs (PN 1–9) can be empirically confirmed with regard to the empirical criteria 1–4 presented in Section 3. In the following, we will first present the questionnaire that we used in our survey (Section 4.1) and the sample of our survey (Section 4.2). After that, we will present how we operationalized the single empirical criteria for data analysis and how we combined them into an aggregated analysis (Section 4.3).

The questionnaire consisted of twenty questions in total (Q1–Q20).

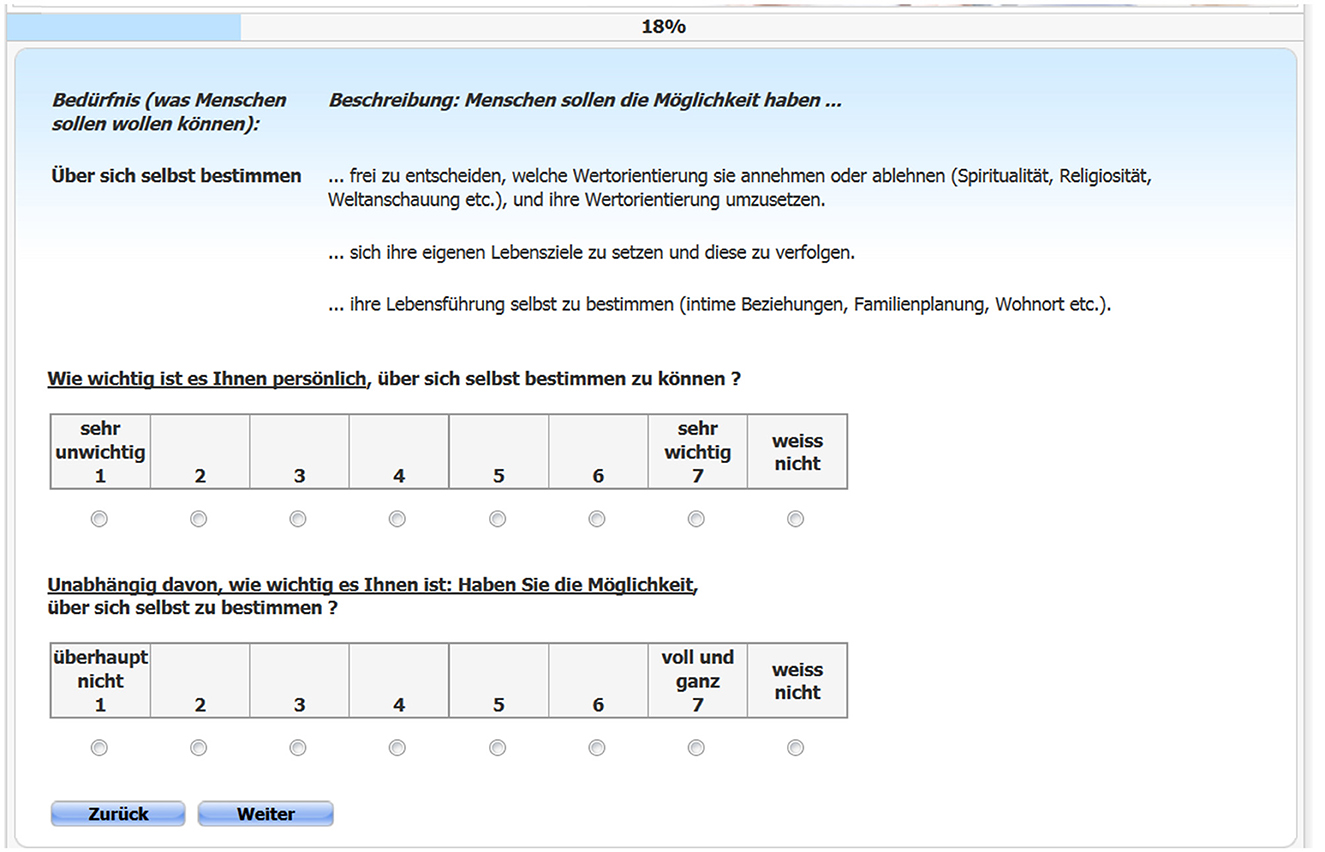

Q5–Q10 were devoted to the Theory of PN. Before being presented with Q5, respondents were introduced to these questions with the following text: “The following is about nine needs that could be important for quality of life. We will ask you different questions on the matter. First, we will ask you to indicate for each need how important it is for you personally, for your own quality of life. In addition, we will ask you to indicate for each of these needs to what extent it is possible for you to do what is described in the need (regardless of how important it is for you).” Respondents were asked about the individual (subjective) importance of each of the nine Protected Needs to them (Q5) and about whether they have the possibility to satisfy each of these nine needs regardless of the importance they attach to them individually (Q6). The thick descriptions of the single needs (Table 1, right column) were introduced in Q5/Q6 (see Figure 1 for how this was done) and were provided as pop-ups in Q7–Q10. Respondents were asked how important they think each of the nine Protected Needs to be with a view to human wellbeing in general (Q7) and whether they think it to be blatantly unjust if circumstances make it impossible for different groups of people to satisfy the need (Q8). For each of the nine Protected Needs, respondents were asked to what extent they feel obliged as an individual to contribute to the possibility of other people to satisfy this need (Q9, perceived responsibility of individual) and how much they think Swiss society is obliged as a community to contribute to the possibility of people to satisfy this need (Q10, perceived responsibility of community).

Figure 1. The screenshot shows how respondents were presented questions 5 and 6 (Q5, Q6) of the questionnaire and the thick descriptions of the single Protected Needs (German version of questionnaire). The example shows Q5 and Q6 for Protected Need 5: “To make their own life choices”.

One question (Q11) was devoted to the concept of consumption corridors, which refers to a way to achieve sustainability in consumption (see, e.g., Blättel-Mink et al., 2013; Di Giulio and Fuchs, 2014). In order to find out how this concept is received in society, we inquired into the openness of the respondents to endorsing the concept. For the rationale of Q11 and the results, see Defila and Di Giulio (2020).

The other questions concerned age (Q1), gender (Q2), residence (canton only; the canton question was positioned after Q2), general life satisfaction (Q3; accompanied by an open Q4 asking what respondents deemed crucial to quality of life), political attitude (Q12), altruism (Q13; for the altruism scale, see Appendix B), current activity (Q14), education (Q15), income (Q16), number of persons living in the same household (Q17), and nationality (Q18, Q19). Q20 was an open question asking for comments.

In order to ensure its quality, the questionnaire was subjected to comprehensive qualitative cognitive testing conducted by M.I.S. Trend, a Swiss institute providing services for qualitative and quantitative surveys. We administered the questionnaire as an online survey (using computer-assisted web interviewing, CAWI). It was fielded in October 2016 and took respondents approximately 25 min in total to complete. The sequence in which the respondents were asked about the nine Protected Needs was randomized as follows: the order in which the needs were asked was random, but only per respondent; that is, the order changed from respondent to respondent but then remained the same within the questionnaire in all questions for one and the same respondent. For all questions, respondents were provided with the option “I don't know”.

The respondents (N = 1,059) were recruited via an online-access panel. The process was managed by M.I.S. Trend. To build a representative sample for Switzerland, we applied quota sampling (crossed quota) using the combined criteria of age, gender, and linguistic region (limited to the German-speaking and French-speaking parts of Switzerland, which cover 25 out of the 26 cantons that are the member states of the Swiss Confederation). The quota used to build the sample matched the distributions in the Swiss population (aged 18 and older; not covering the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland, that is, one of the 26 Swiss cantons; see Appendix B, Table B1). Because respondents from the French-speaking part of Switzerland were slightly overrepresented in the sample relative to the overall Swiss population, the answers were weighted in the data analysis.

The sample consisted of 50.9% women and 49.1% men. The average age of the respondents was 47 with an age distribution as follows: 2.1% of the respondents were aged 18–19, 34.2% were aged 20–39, 47% were aged 40–64, and 16.7% were 65 or older (with a distribution ranging from 18 to 84).

The sample was representative also beyond the applied sampling criteria: the sample showed a distribution by citizenship status that was relatively similar to the distribution in the Swiss population [86.1% Swiss citizens (including dual citizenship) and 13.9% non-citizens; the Swiss population in 2015 was comprised of 76.1% Swiss citizens (including dual citizenship) and 23.9% non-citizens]. The sample was fairly comparable to the Swiss population also in terms of household size (most respondents, 66.6%, living in single-member or two-person households; Appendix B, Table B2), political attitude (a plurality of respondents, 43.8%, adopting neither a pronounced left-wing attitude nor a pronounced right-wing attitude; Appendix B, Table B3), and diversity with regard to education (Appendix B, Table B4) and income (Appendix B, Table B5).

The collected data should answer two questions: (a) How do people react to the nine Protected Needs with a view to the different dimensions covered in the survey? (b) To what extent can the nine Protected Needs be confirmed with regard to the empirical criteria presented in Section 3, that is, to what extent do they empirically qualify for the status of being protected needs? Question (b) is the question informing this paper.

The empirical criteria each need has to meet to qualify as protected are cumulative; that is, single criteria cannot be compensated. Confirming the criteria thus requires an analysis of the data that combines the criteria into an aggregated analysis. In this section, we will present how we operationalized the single criteria for data analysis (Sections 4.3.1–4.3.3), that is, which question(s) of the questionnaire we drew on and what we determined to be decisive for whether a criterion is met (+) or not (–) and for how it fed correspondingly into the aggregated analysis that combined the criteria per need. For the aggregated analysis of the data, the criteria were translated into possible response patterns. These response patterns are presented in Section 4.3.4.

For the analysis of the data, we used SPSS. No answer and “I don't know” were both coded as missing.

In operationalizing the empirical criteria, criterion 1 and criterion 2 were combined. Criterion 1 consists of two elements: (a) the need is not a theoretical construct, that is, it is possible to identify a “construct of wanting” that corresponds with how the need is defined; and (b) not having the possibility to satisfy the need affects individuals' wellbeing. Criterion 2 in turn is subordinate or an extension of criterion 1(a) since it requires that experiencing the need is not tied to a specific segment of people.

The data relevant for criterion 1 and criterion 2 are provided by Q5 and Q6 and by relating the answers to these questions to the answers to Q3 (general life satisfaction).

Respondents were asked about the individual (subjective) importance of each of the nine needs for their own life (Q5) and about whether they have the possibility to satisfy each of these nine needs regardless of the importance they attach to them individually (Q6). This was done by asking them for each of the nine needs how important it is to them personally to... [here, the need was named] (Q5; 7-point scale: 1 = not important at all, 7 = very important, 2–6 not labeled). Before proceeding from one need to the next, they were asked whether they have, regardless of how important it is to them, the possibility to... [here the need was named again] (Q6; 7-point scale: 1 = not at all, 7 = fully and completely, 2–6 not labeled). Figure 1 shows a screenshot of how respondents were presented Q5/Q6. Asking about both the importance of each need and the possibility to satisfy each need is also in line with Costanza et al. (2007, p. 272), who suggest inquiring into both dimensions, because “overall QOL [quality of life] at any point in time is a function of (a) the degree to which each identified human need is met, which we will call ‘fulfilment' and (b) the importance of the need to the respondent or to the group in terms of its relative contribution to their subjective wellbeing.” We adapted this to the purpose of our survey insofar as we did not ask about the actual satisfaction of the single needs but about the possibility to satisfy the single needs.

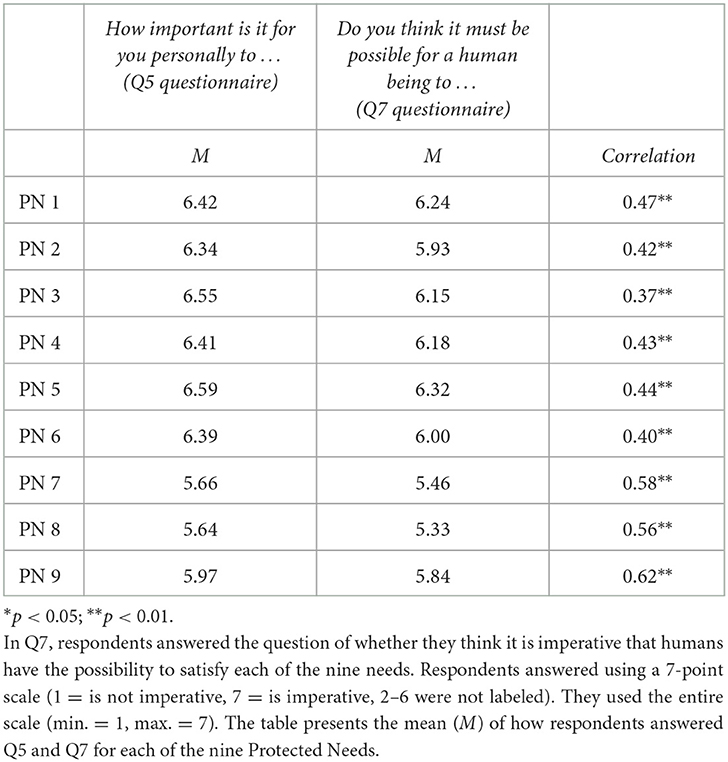

With regard to whether criterion 1 is met (+) or not (–), we decided, first, to focus on the data provided by Q5. The answers to Q5 show the explicit ascriptions of importance to the different needs by the respondents. For a need to qualify as protected in a society, it must be explicitly qualified as important. This line of argument is supported by the results from correlating the respondents' answers to Q5 and their answers to Q7, the question in which they were asked for each of the nine needs whether they think it is imperative that people can, with a view to quality of life, satisfy this need or whether they think people can reconcile themselves to not being able to satisfy this need (Table 2). The attribution of general importance to a need with a view to quality of life strongly and significantly correlates with the explicit subjective importance attributed to the need.

Table 2. The extent to which the individual importance assigned to each of the nine Protected Needs (PN 1–9) (Q5) correlates with the general importance for human wellbeing attributed to each of the nine Protected Needs (Q7).

Second, we decided that the criterion is met when respondents chose a value above 2 (= values 3–7) in answering Q5 and that it is not met when respondents chose value 1 or 2. According to the questionnaire, a need is ascribed some importance at a value of 2. But because this has to be considered an extremely weak importance, we decided that not only value 1 but also value 2 expresses that respondents do not ascribe a subjective importance to the need.

Third, we decided that only criterion 1(a) (the need is not a theoretical construct, that is, it is possible to identify a “construct of wanting” that corresponds with how the need is defined) should feed into the aggregated data analysis. The extent to which criterion 1(b) (not having the possibility to satisfy the need affects individuals' wellbeing) is met, is revealed by the results of relating Q6 and Q3 because this uncovers the actual relevance of each need to quality of life, regardless of whether the need is deemed to be important or not. Using only Q6 instead would not be suitable, because Q6 shows how respondents judge whether they have the possibility to satisfy the different needs and not whether this is crucial for quality of life or not (furthermore, Q6 does not indicate whether respondents' judgments concerning whether they have the possibility to satisfy a need is accurate, nor does it reveal anything about their expectation with regard to when a need is satisfied). That is, criterion 1(b) can best be judged by drawing directly on the correlation of Q6 and Q3 and by comparing this correlation with the correlation of Q5 and Q3.

Criterion 2 is, as stated above, an extension of criterion 1(a) since it requires that experiencing the need is not tied to a specific segment of people. This translates into the requirement that the group of respondents for which criterion 1 is not met must be empirically negligible.

To conclude, criterion 1(a) feeds into the syntax used for the aggregated analysis of the data as follows (for each of the nine Protected Needs):

Criterion 1(b) (crucial/not crucial for QoL) and criterion 2 [= extension of criterion 1(a)] do not feed into the aggregated analysis of the data. Criterion 1(b) has to be judged by drawing on the results of correlating Q6 and Q3 (and by comparing this with the correlation of Q5 and Q3). Whether criterion 2 is met depends on how the respondents distribute among the two groups + and –.

Criterion 3 encompasses three elements: (a) the need is perceived to be a crucial constituent of the wellbeing of humans; (b) it is perceived to be a universal human need; and (c) it is perceived as not being up for negotiation.

The data relevant for criterion 3 are provided by combining Q7 and Q8. We wanted to know whether respondents concede the nine needs to others and to what extent they perceive them to be contestable [Q7 and Q8; for their rationale, see Defila and Di Giulio (2021)]. This was addressed for each of the nine needs by asking respondents whether they think it is imperative that people can, with a view to quality of life, satisfy this need or whether they think people can reconcile themselves to not being able to satisfy this need (Q7; 7-point scale: 1 = is not imperative, 7 = is imperative, 2–6 not labeled). In Q8, for each of the nine needs, respondents were asked whether they think it is blatantly unjust if circumstances (such as a lack of money, prohibition by family or religion, a non-supportive environment, not being allowed by law) make it impossible for different groups of people to satisfy this need (Q8; scale was five groups of people that were presented as an increasing scope of persons). That is, respondents answered by indicating whether they felt being unable to satisfy the need was blatantly unjust for no one (coded 1 in data analysis), only for Swiss citizens (coded 2 in data analysis), also for foreigners living in Switzerland (coded 3 in data analysis), also for refugees and undocumented migrants living in Switzerland (coded 4 in data analysis), or for people living all over the world (coded 5 in data analysis). It was technically possible to give incorrect answers. For the analysis of the data, incorrect answers were coded as missing.

For how respondents answered Q7 and Q8 in detail, see Defila and Di Giulio (2021). The results show that in answering Q8, some respondents for whom the needs were not up for negotiation adopted a national perspective (unjust only for Swiss citizens), others a territorial perspective (unjust for all people living in Switzerland, that is, Swiss citizens, foreigners living in Switzerland, refugees, and undocumented migrants living in Switzerland), and still others a global perspective (unjust for all people regardless of where they live in the world) (Defila and Di Giulio, 2021, Table 13.4).

We decided to take up this nuanced picture about the incontestability of the nine needs and to apply a two-step procedure in the aggregated analysis of the data by distinguishing in a first step only according to whether respondents perceived a need not to be up for negotiation no matter where they drew the line or whether they rejected the very idea of a need to be incontestable. That is, the first step covers criteria 3(a) and 3(c). In a second step, the data analysis should reveal to what extent the need was perceived to be universally incontestable. That is, criterion 3(b) was added in a second step (and only for respondents, of course, that perceived the need to be incontestable).

Accordingly, criterion 3 feeds into the syntax used for the aggregated analysis of the data as follows (for each of the nine Protected Needs):

Criterion 4 consists of two elements that each cover more than one dimension: element (a) relates to who has the ethical obligation to contribute to the possibility of human beings to satisfy this need (dimensions: the individual, the community); element (b) relates to the recipients of this responsibility (dimensions: present generations, future generations, in one's own country, all over the world).

The data relevant for criterion 4 are provided by Q9 and Q10. We wanted to find out to what extent the nine needs ground a sense of ethical obligation to contribute to the possibility of human beings to satisfy these needs [Q9 and Q10; for their rationale, see Defila and Di Giulio (2021)]. Respondents were asked, for each of the nine needs, to what extent they feel obliged as an individual to contribute to the possibility of other people to satisfy this need (dimensions of recipients they had to consider: present generations in their own country, present generations all over the world) (Q9; 7-point scale: 1 = not obliged at all, 7 = strongly obliged, 2–6 not labeled). Respondents were asked, for each of the nine needs, how much they think Swiss society is obliged as a community to contribute to the possibility of people to satisfy this need (dimensions of recipients they had to consider: present generations in their own country, present generations all over the world, future generations in their own country, future generations all over the world) (Q10; 7-point scale: 1 = not obliged at all, 7 = strongly obliged, 2–6 not labeled). For how respondents answered Q9 and Q10 in detail, see Defila and Di Giulio (2021).

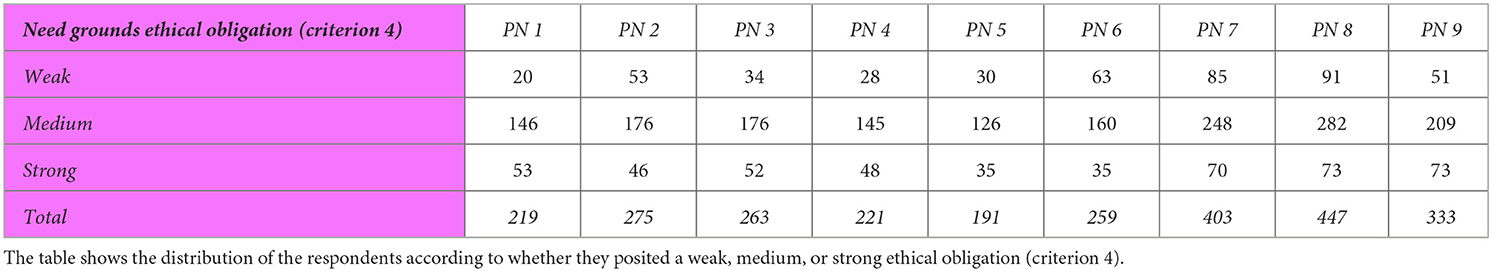

For a need to be protected in a society, a responsibility must be assumed by both the individual and the community. And for this protection to be in line with the idea of sustainability, the recipients of this responsibility must not be limited to present generations or to the people in one's own country. That is, an aggregated analysis of the data must integrate all the dimensions contained in criterion 4. At the same time, responsibility is not a binary concept. Rather, people can feel more or less obliged; some actors can be assigned a higher and others a lower responsibility, depending on their agency and on their power in society. In order to account for the complexity of this criterion while keeping the analysis of the data manageable, we decided to apply a two-step procedure in the aggregated analysis of the data for this criterion as well. In a first step, we distinguished only according to whether respondents judged a need to ground an ethical obligation or not, independent of how strong the obligation was judged to be. In a second step, we differentiated according to whether the need grounds a weak, medium, or strong obligation.

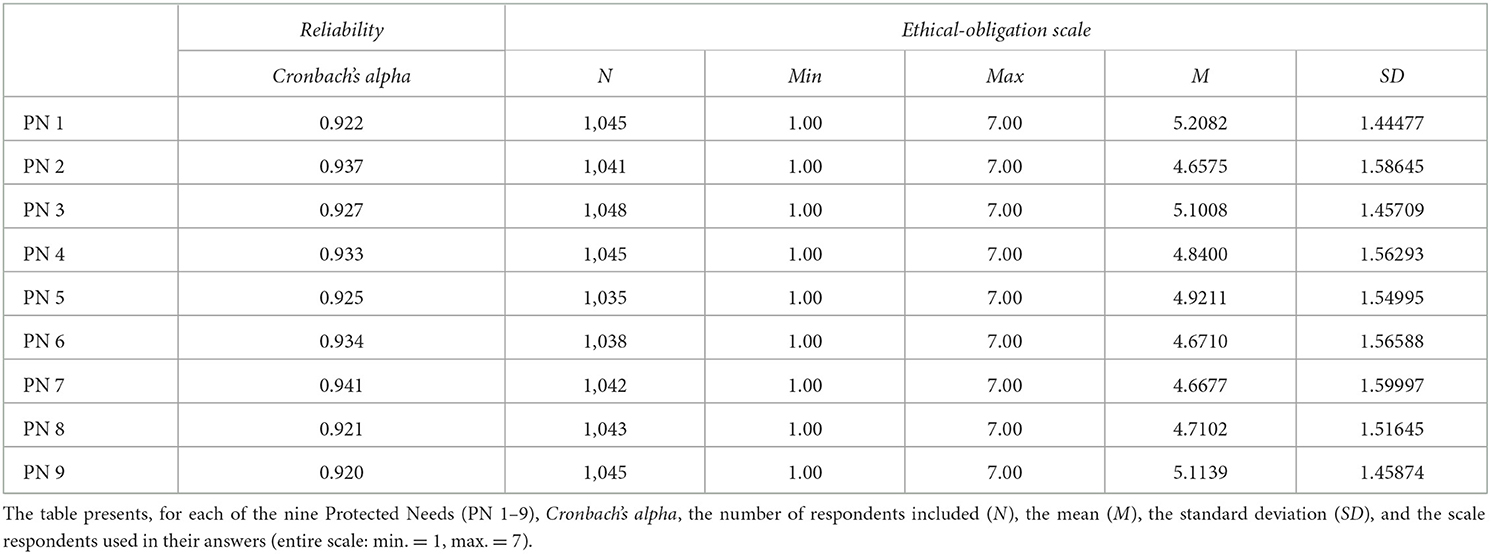

In order to integrate all the dimensions contained in criterion 4, we built a new scale that integrates Q9 and Q10, the “ethical-obligation scale”. The internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha, for this scale is above 0.92 for all nine needs, indicating that the reliability of the scale is highly satisfying (Table 3).

Table 3. The reliability of the ethical-obligation scale built by combining data for Q9 (2 items) and Q10 (4 items).

In the questionnaire, respondents were offered the possibility that a need does not ground an ethical obligation (value 1 = not obliged at all). That is, as of value 2, an ethical obligation is perceived. But because this has to be considered an extremely weak obligation, we decided that not only value 1 but also value 2 expresses that respondents do not feel that the need grounds an ethical obligation.

Accordingly, criterion 4 feeds into the syntax used for the aggregated analysis of the data as follows (for each of the nine Protected Needs):

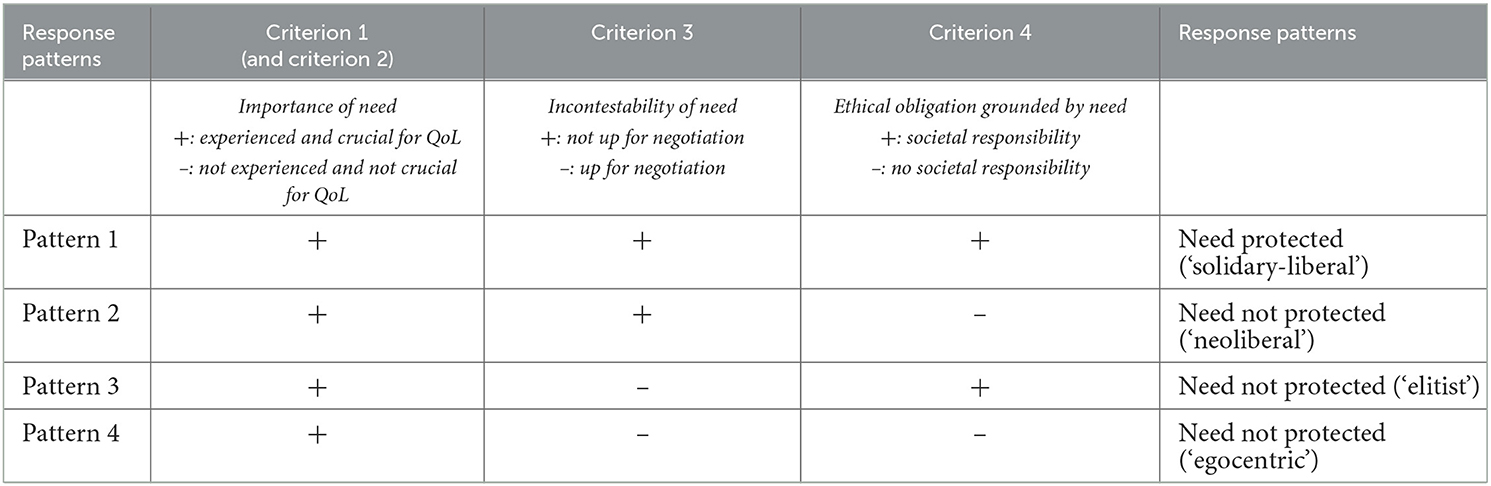

As noted above, determining whether a need on the list of Protected Needs can be empirically confirmed as protected requires an aggregated analysis of the data that combines the empirical criteria because these criteria are cumulative. This leads to eight possible response patterns (Table 4). These possible response patterns built the rationale for data analysis.

In this section, we present the results of the data analysis. The data analysis was carried out according to the operationalization of the empirical criteria that the nine needs in the Theory of Protected Needs must meet to qualify as protected needs (Sections 3 and 4). Not all the data that must be considered in judging to what extent the nine needs meet these criteria fed into the syntax used for the aggregated analysis. This applies to some of the data of relevance for criterion 1 (see Section 4.3.1). In Section 5.1, we report the results of the data analysis that are relevant to criterion 1 but did not feed into the aggregated data analysis. In Section 5.2, we present the results of the aggregated data analysis.

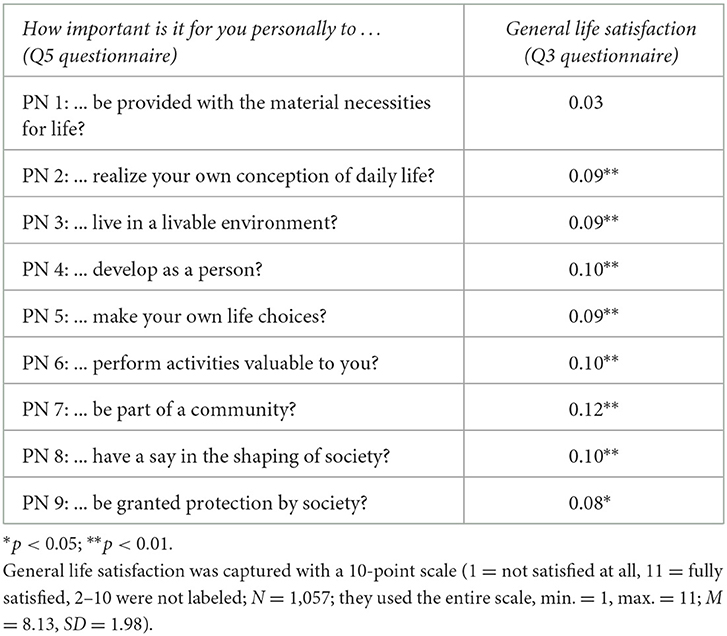

Table 5 shows the importance respondents attributed to the nine needs for themselves (individual/subjective importance, Q5). The results show that overall, all nine needs are attributed a high importance (M is between 6 and 7 for PN 1–6 and between 5 and 6 for PN 7–9), although the importance differs individually. Table 6 shows to what extent the individual importance of the different needs correlates with overall life satisfaction. The results show that the individual importance of the nine needs and general life satisfaction correlate but that the effects are weak.

Table 6. The extent to which the individual (subjective) importance attributed to the nine Protected Needs (PN 1–9) correlates with general life satisfaction.

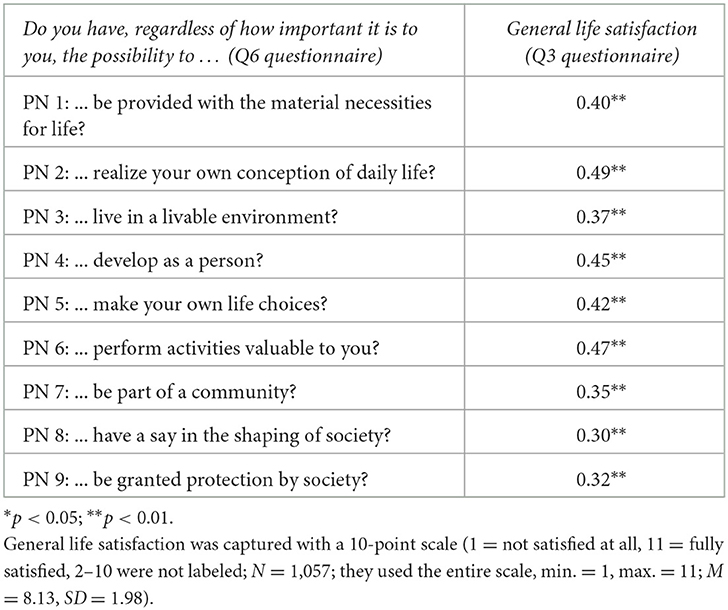

Table 7 shows how respondents judged whether they have the possibility to satisfy each of the nine needs, regardless of the importance they attach to them individually (perceived possibility, Q6). The results show that respondents actually had, according to them, the possibility to satisfy all nine needs and that this possibility was roughly the same for all nine needs with the exception of need 8, which they judged themselves to a have a lower possibility to satisfy in comparison to the other needs. Table 8 shows to what extent the possibility to satisfy the different needs correlates with overall life satisfaction. The results show that in contrast to the weak correlation between general life satisfaction and the individual importance of the needs, the possibility to satisfy the nine needs and general life satisfaction correlate with an effect that is statistically significant and fairly strong for all nine needs (comparison of Tables 6, 8).

Table 8. The extent to which the possibility to satisfy the nine Protected Needs (PN 1–9) correlates with general life satisfaction.

As written above, combining empirical criteria 1–4 leads to eight possible response patterns (Table 4). These response patterns informed the aggregated analysis of the data. This section presents the results of this aggregated analysis. According to the differentiations made for criteria 3 and 4, we first present the results of step 1 of the aggregated analysis of the data and then the results of step 2 (see Sections 4.3.2, 4.3.3).

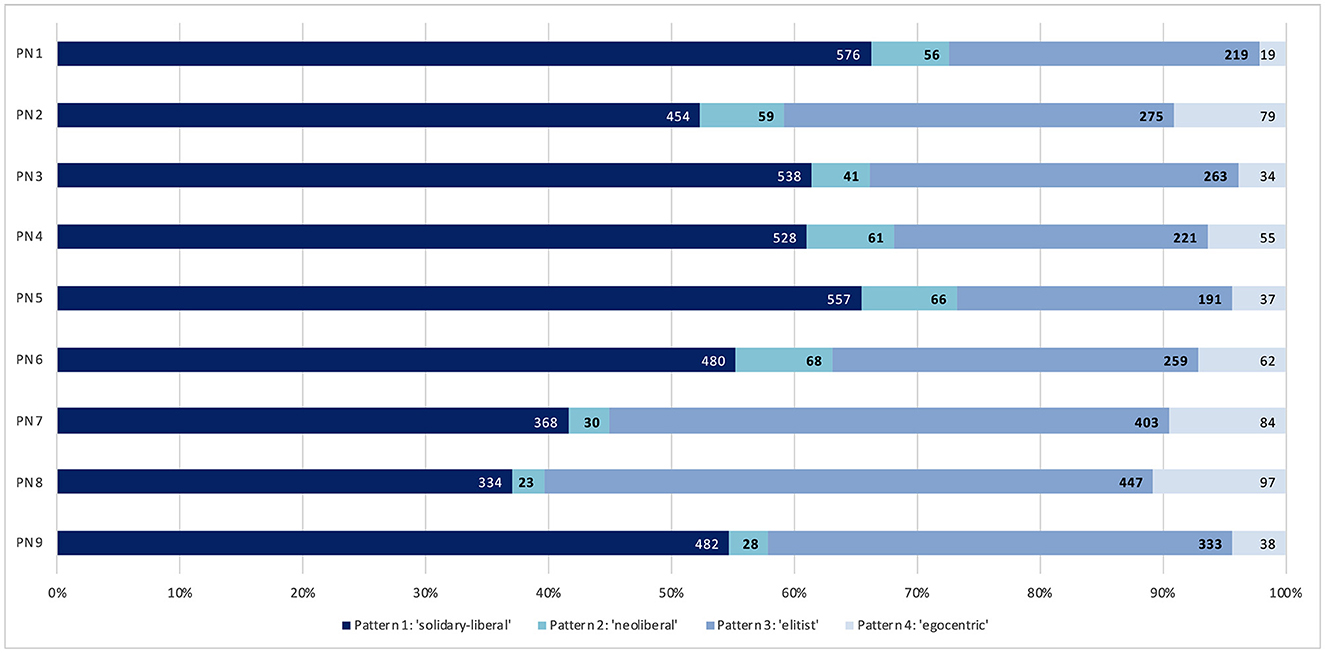

Table 9 shows which response patterns were chosen by how many respondents for each of the nine needs. The table shows that the most common patterns of how respondents answered the questions are patterns 1 and 3, while only a few respondents followed patterns 5–8; this applies both per need and in total. Patterns 2 and 4 apply to a minority of respondents, and the number of respondents following patterns 2 and 4 are not far apart. For seven of the Protected Needs, pattern 1 is prevalent; for two of them (PN 7 and PN 8), the prevalent pattern is pattern 3. For PN 7, patterns 1 and 3 are exhibited by an almost equal number of respondents. For all nine needs, the number of respondents exhibiting one of patterns 5–8, is negligible. Patterns 1–4 have in common that in all of them criterion 1 is met (+), while patterns 5–8 have in common that in all of them criterion 1 is not met (–).

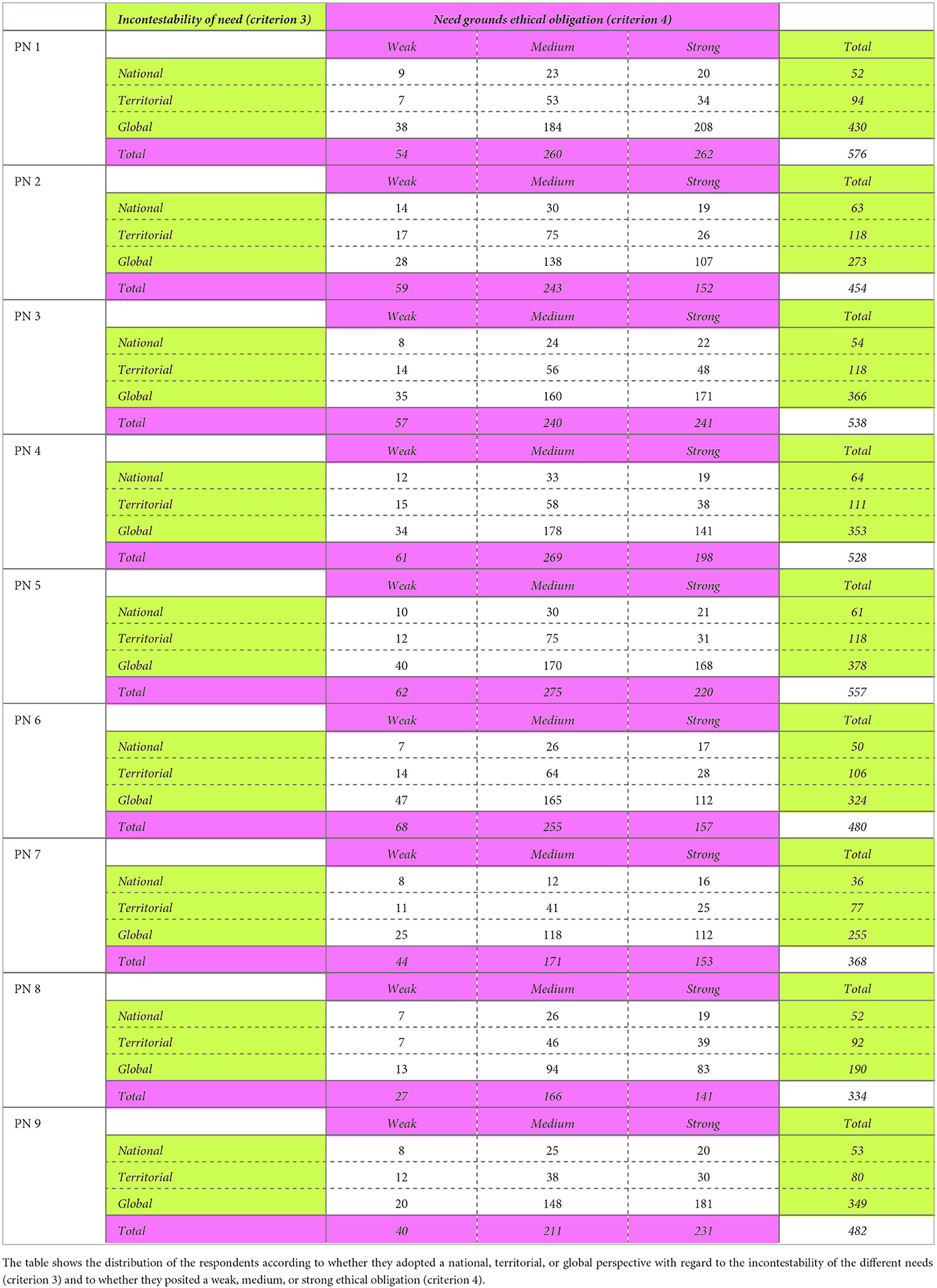

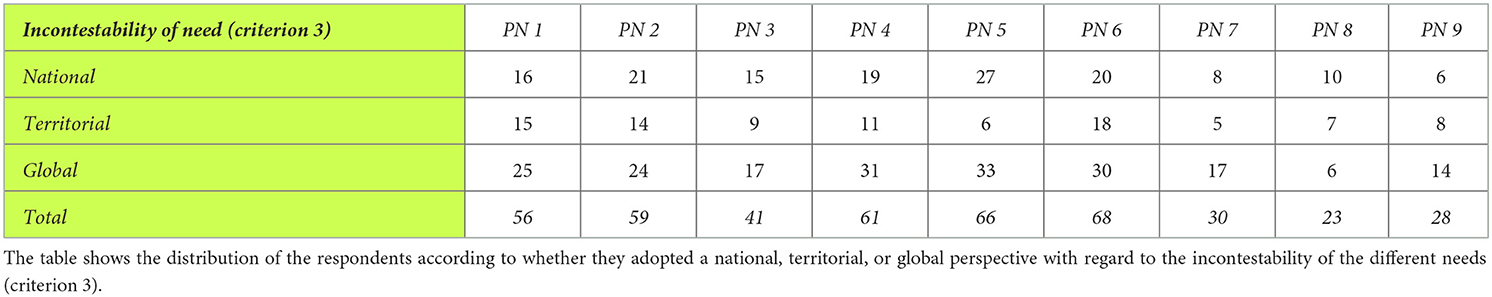

The results of step 2 of the data analysis, the differentiations for criteria 3 (“incontestability of need”) and 4 (“need grounds ethical obligation”), are presented for response patterns 1, 2, and 3. In response pattern 4, criteria 3 and 4 are not met (–), and the occurrences of response patterns 5–8 are negligible in terms of the numbers of respondents to which they apply.

Table 10 shows the differentiated results for response pattern 1 (covering both criterion 3 and criterion 4), Table 11 shows the differentiated results for response pattern 2 (covering criterion 3), and Table 12 shows the differentiated results for response pattern 3 (covering criterion 4). Table 10 reveals that the respondents who exhibit response pattern 1 also show a clear tendency toward combining a global perspective with regard to the incontestability of the nine needs and a medium or strong sensed ethical obligation, while only a minority of those that exhibit response pattern 1 also adopt a national perspective with regard to the incontestability of the nine needs and/or posit a weak ethical obligation. Compared to this picture, it is salient that the group of respondents that shows response pattern 3 displays a clear tendency toward a medium ethical obligation for all nine needs and that the number of respondents positing a weak ethical obligation and the number of those positing a strong ethical obligation do not differ considerably (Table 12). The number of respondents showing response pattern 2, in turn, is rather small, and there is not a clearly discernible tendency for their perspective regarding the incontestability of the nine needs (Table 11).

Table 10. The results of step 2 of the aggregated data analysis for pattern 1 for each of the Protected Needs (PN 1–9).

Table 11. The results of step 2 of the aggregated data analysis for pattern 2 for each of the Protected Needs (PN 1–9).

Table 12. The results of step 2 of the aggregated data analysis for pattern 3 for each of the Protected Needs (PN 1–9).

The guiding question for this paper is to what extent the nine Protected Needs empirically qualify for the status of being protected needs. We determined four empirical criteria that needs have to meet to qualify for this status (Section 3). In the following, we will discuss the empirical results first with a view to each criterion. Then we will discuss the results of the aggregated analysis in which the criteria were combined into response patterns. The results of the data analysis justify discussing the nine needs as a set of needs instead of discussing each one separately.

Criterion 1: The nine needs are actually experienced by people and they are crucial constituents of quality of life. The results show that this criterion is confirmed for all nine needs on the list of Protected Needs. All nine needs are actually mirrored in respondents' “constructs of wanting”. In answering the survey, basically all respondents exhibited one of the four response patterns in which criterion 1(a) is met, according to how we operationalized this criterion (patterns 1–4, Table 9). This is also confirmed by the small SD in how respondents answered Q5 of the survey (Table 5). Criterion 1(b), the possibility to satisfy the need is crucial for quality of life, did not feed into the aggregated analysis of the data but has to be judged by drawing on data resulting from correlating Q6 and Q3 (Table 8). The results reported in Table 8 show that with regard to all nine needs, there is a fairly considerable correlation between respondents' perceived possibility to satisfy the need and their general life satisfaction, in contrast to the results reported in Table 6, which show at most a weak correlation between the individual importance of the nine needs and life satisfaction. This indicates that life satisfaction does not depend on which of these needs are important to an individual but on which of these needs an individual can satisfy according to their own perception. In this respect, the results show that all nine needs have a comparable effect on life satisfaction. That means that all nine needs meet criterion 1(b). We thus conclude that all nine needs on the list of Protected Needs are actually experienced by people and are crucial constituents of quality of life.

Criterion 2: The nine needs are supra-individual. This criterion did not feed into the aggregated analysis of the data. This criterion is an extension of criterion 1 since it demands that experiencing the nine needs on the list of Protected Needs is not tied to a specific segment of people; that is, it demands that each need can be experienced by a diversity of people. Accordingly, this criterion translates into the requirement that the group of respondents for whom criterion 1 is not met must be empirically negligible. Table 9 shows that this is the case for all nine needs: the number of respondents that exhibited one of the response patterns in which criterion 1 is not met (–) is, in sum, <7 respondents for PN 1–6, <20 for PN 8 and PN 9, and only 27 for PN 7. This indicates that experiencing the single needs is not tied to a specific segment of people. Hence, we conclude that we have strong reasons to assume that all nine needs on the list of Protected Needs are supra-individual.

Criterion 3: The nine needs are perceived as needs that are not negotiable. The results show that this is the criterion that is the most polarizing. If we only consider the response pattern adopted by the majority of respondents (Table 9), then the criterion is confirmed for seven of the nine needs (PN 1–6, PN 9) by a majority of respondents, and it is confirmed by a smaller group of respondents for PN 7 (to be part of a community) and for PN 8 (to have a say in the shaping of society). But a closer look at the distribution of respondents across the response patterns (Table 9) reveals more than this. It is salient that the two response patterns that apply to the vast majority of respondents, patterns 1 and 3, differ with regard to whether criterion 3 is met (pattern 1) or not met (pattern 3) according to how we operationalized it. And it is also salient that with regard to whether the needs are negotiable or not, there is a clear divide: PN 1–6 and PN 9 are less polarizing in this respect than PN 7 and PN 8. The differentiated analysis of the perspectives adopted within response pattern 1 (Table 10) shows that the global perspective is prevalent, that is, there is a discernible distinct tendency to perceive all nine needs as universals. This tendency is also recognizable in response pattern 2 for PN 1–7 and PN 9 (Table 11), but it is not as clear. Hence, we conclude, first, that while seven of the needs on the list of Protected Needs are perceived as being universal needs that are not negotiable (PN 1–6, PN 9) by a majority of the respondents, this is not the case for two of them (PN 7, PN 8). Second, we conclude that there is a tendency to conceptualize constituents of quality of life as something that unites humankind across cultures and nations. And we conclude, third, that the criterion that human needs are not negotiable is polarizing.

Criterion 4: The nine needs ground a societal responsibility. The results show that this criterion is confirmed for all nine needs on the list of Protected Needs. The two response patterns in which both the importance of a need and the ethical obligation grounded by a need are met (+) according to how we operationalized these criteria apply to the vast majority of respondents (patterns 1 and 3), while the response patterns in which the importance of a need is met (+) but the ethical obligation grounded by a need is not met (–) only apply to a minority of respondents (patterns 2 and 4) (Table 9). The differentiated analysis of the perspectives adopted in response pattern 1 (Table 10) shows that there is a distinct tendency to posit a medium or strong ethical obligation with regard to all nine needs, while in response pattern 3 there is a tendency to posit a medium ethical obligation (Table 12). Hence, we conclude that all nine needs on the list of Protected Needs ground a societal responsibility.

Based on our operationalization of empirical criteria 1–4, we identified eight possible response patterns (Table 4). To qualify for the status of being protected, the nine needs on the list of Protected Needs must meet all these criteria cumulatively (see Sections 3, 4.3.4). The data analysis shows that of the eight possible response patterns, four are empirically negligible (patterns 5–8) and four are empirically relevant (patterns 1–4), although not all of them are equally important with regard to how many respondents exhibit them (response patterns 1 and 3 are prevalent).

Response patterns 1–4 can be characterized as follows (Table 13): In pattern 1, all the empirical criteria are met. This pattern corresponds to endorsing the notion of a need being protected in all dimensions. This pattern reflects an attitude of high attention for human wellbeing as a societal task; a term that captures its characteristics could be ‘solidary-liberal'. In pattern 2, a need does not ground an ethical obligation. According to this pattern, although a need is perceived to be important and incontestable, there is no societal responsibility with a view to the corresponding need. This pattern reflects what are often labeled ‘neoliberal' beliefs in current debates: society does not have a responsibility with regard to humans achieving crucial constituents of human wellbeing. In pattern 3, a need is up for negotiation, even though its importance is attested as is the ethical obligation with regard to the need. This pattern reflects an attitude that is best referred to as ‘elitist': humans are not by default entitled to crucial constituents of human wellbeing. In pattern 4, nothing can be inferred for society from the importance of a need. This pattern reflects an attitude of disregard for human wellbeing as a societal issue that can, we think, be called ‘egocentric'.

Table 13. The empirical criteria that the nine needs on the list of Protected Needs must meet to qualify as protected were translated into eight possible response patterns (Table 4); four of those patterns were empirically manifested.

Figure 2 visualizes a profile of response patterns 1–4 for each of the nine needs on the list of Protected Needs. In response pattern 1 (‘solidary-liberal'), all four empirical criteria for qualifying as a protected need are met. The prevalent response pattern for seven of the nine needs is pattern 1. That is, these seven needs qualify for the status of being protected for a majority of respondents (at least in Switzerland where our survey was fielded), while two needs on the list of Protected Needs qualify for the status of being protected for a smaller group of respondents. Considering the results of the data analysis allows a more nuanced answer: all nine needs on the list of Protected Needs qualify to a considerable extent for the status of being protected by society. All nine needs are confirmed to be crucial constituents of quality of life, and they are confirmed to ground a societal obligation for individuals and the community. What polarizes is the question of whether they are universal and incontestable.

Figure 2. The figure visualizes the relative distribution of the four empirically relevant response patterns for each of the nine Protected Needs. These are response pattern 1 (‘solidary-liberal'), response pattern 2 (‘neoliberal'), response pattern 3 (‘elitist'), and response pattern 4 (‘egocentric'). For each response pattern, the number of respondents who exhibit this response pattern is given. Response pattern 1 is the one in which all the empirical criteria that needs must meet to qualify for being protected by society are met.

That PN 7, to be part of a community, was not perceived as universal and incontestable by a majority of respondents stands in stark contrast to knowledge about the importance of social relationships in citizen definitions of happiness and in other empirical investigations of human wellbeing [see, e.g., the review of the literature by O'Mahony (2022), with regard to the importance of “social and relational factors”]. The interesting question is whether something has changed in how this need is perceived due to the experiences of isolation many people had during the COVID-19 pandemic. That PN 8, to have a say in the shaping of society, was not perceived to be universal and incontestable by a majority of respondents is particularly noticeable considering the political setting of Switzerland, the country in which the survey was fielded, because in Switzerland, having the possibility to participate in societal decisions is held in high esteem. But it might not be so surprising since there is also an ongoing societal and political debate in Switzerland about what political rights people who do not have Swiss citizenship should have and about what age people should reach before they are allowed to vote. That is, the enactment of this need is formalized in structural procedures that exclude a considerable number of people.

Regarding the polarizing effect of the incontestability of needs, it might also be interesting to mention a previous data analysis (Defila and Di Giulio, 2021) that found that how respondents answered the question on the universality of the nine needs (Q8) depends on their political attitude, in contrast to the questions on perceived ethical obligation (Q9 and Q10). That is, political attitude is a predictor for whether needs are perceived to be universal or not, although the effect is not strong (for perceived ethical obligation, altruism was a much stronger predictor than political attitude, while the variables age, gender, education, and income had no significant effect on how respondents answered Q8, Q9, and Q10; Defila and Di Giulio, 2021). From this, we might conclude that the Theory of Protected Needs has a high potential for being used as a foundation for conceptualizing sustainability as ‘caring for human wellbeing', but in order also to use it practically, the debate about human wellbeing should be decoupled from political attitudes and framed as a societal deliberation about what humans deserve simply because they are humans. This in turn requires supporting people's competences and willingness to engage in societal deliberations in their role as citizens.

A society that is caring for human wellbeing is made up of three ingredients, and in all three ingredients, the perspective is neither limited to the life span of present generations nor to the members of that particular society:

• It engages in debates about what needs are crucial to wellbeing, and in doing so it adopts a salutogenic and comprehensive approach.

• It perceives human needs to be incontestable; that is, it holds it to be self-evident that people are entitled to satisfy crucial human needs, that they have a right to be equipped with the satisfiers necessary to meet such needs simply because they are human.

• Its guiding principle for decision-making and policy-making is that people and institutions must contribute to guaranteeing the conditions necessary for satisfying crucial human needs for other people living in the present and in the future.

In sum, all individuals have the right to have society take care of the conditions necessary for them to be able to satisfy the needs that are crucial for their wellbeing. To this end, individual freedom is warranted but limited by justice and solidarity.

Our research shows that the Theory of Protected Needs with its nine needs has a high potential to be used as a conceptual foundation of human wellbeing for such a society. What is polarizing and thus calls for societal debate is the question of whether needs are universal and incontestable. There is no silver bullet for such a debate. In addition to supporting people's ability and willingness to engage in societal deliberations as citizens (and not as members of a specific party or as followers of a specific party program), it is necessary to fight narratives that devalue the role of the community and glorify the principle of “everyone is the architect of their own fortune” and to feed narratives of a good life, solidarity, and justice instead. This would be worthwhile because we have some empirical evidence that people who endorse the idea of universal human needs are also inclined to endorse the idea of limiting consumption for the sake of others having the possibility to satisfy their needs (Di Giulio and Defila, 2021).

Our research was conducted in Switzerland. What remains to be done is to explore how the Theory of Protected Needs is received in other countries. We have indications that it also resonates in other cultural contexts. For example, as mentioned above in Section 3, an investigation used the list of Protected Needs to explore how green public spaces act as satisfiers in Chennai, Metro Manila, Shanghai, and Singapore. This research shows that this list of needs also resonates outside the cultural context in which it has been developed (Sahakian et al., 2020; Di Giulio et al., 2022).

Research could also investigate whether the perception of the needs on the list of Protected Needs has changed due to the crises that have been swamping the world since 2020. From a practical perspective, it would be promising to explore whether and how the list of Protected Needs can be translated into actual decision-making and policy-making. For campaigns to put the notion of caring center stage in the sustainability debate, our research is promising because it shows that the fundament of supporting and promoting a narrative of care that is not abstract but related to concrete needs does exist. This fundament could be used to conceptualize sustainability as ‘caring for human wellbeing' not only theoretically but also in practice.

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: The dataset is not yet completely analyzed and will be made available once the analysis has been completed and the data has been anonymized. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to ADG, YW50b25pZXR0YS5kaWdpdWxpb0B1bmliYXMuY2g=.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Conceptualization and methodology of research and empirical investigation: RD and ADG. Analysis of data: CRS. Interpretation of data, review, and editing: ADG, CRS, and RD. Draft of paper: ADG. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was funded by the Mercator Foundation Switzerland. Publication has been funded by the Publication Fund of the University of Basel for Open Access.

We want to thank the more than 1,000 respondents who answered our questionnaire. A special thanks goes to Peter Bartelheimer, Mathias Binswanger, Birgit Blättel-Mink, Doris Fuchs, Konrad Götz, Gerd Michelsen, Martina Schäfer, Gerd Scholl, Michael Stauffacher, Roland Stulz, and Stefan Zundel. They were willing to give us their time, their thoughts, and their creativity. The discussions with them were both challenging and productive. We have to thank M.I.S. Trend in Lausanne, and especially Christoph Müller, who accompanied the development of our questionnaire, conducted the cognitive testing for us, and implemented the questionnaire. Their commitment to helping improve the quality of the questionnaire, and so also the data, was extremely valuable. Furthermore, we thank Ruth Kaufmann-Hayoz and Lisa Lauper for an inspiring collaboration—without them we would not have achieved anything. We have to thank also our reviewers Soumyajit Bhar and Lina Isabel Brand Correa for their valuable and in-depth suggestions for improving the paper. Last but not least we thank Anthony Mahler for his highly appreciated support in editing the paper.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article, Appendix A (German and French Version of Protected Needs) and Appendix B (sample of the Swiss survey), can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2023.1036666/full#supplementary-material.

1. ^Salutogenic approaches are based on “a positive perspective on human life” and aim to investigate the origins of health rather than those of disease and risk (Mittelmark and Bauer, 2017).

2. ^The Theory of Protected Needs builds on the huge and important body of research on quality of life in general and in the context of sustainability, but it is beyond the scope of this paper to engage with that literature. We therefore refer to previous publications in which we have situated this theory in the context of the scholarly literature (e.g., Di Giulio, 2008; Di Giulio et al., 2010, 2012).

3. ^The members of the interdisciplinary advisory board were Peter Bartelheimer, Mathias Binswanger, Birgit Blättel-Mink, Doris Fuchs, Konrad Götz, Gerd Michelsen, Martina Schäfer, Gerd Scholl, Michael Stauffacher, Roland Stulz, and Stefan Zundel. The project team was Rico Defila, Antonietta Di Giulio, Ruth Kaufmann-Hayoz, and Lisa Lauper.

4. ^We use “what individuals must be allowed to want” (Table 1, left column) in order “to emphasise that this list of needs does not entail that individuals must develop a corresponding construct of wanting but that they have to be allowed to do so; and if they do, they are entitled to satisfy it” (Di Giulio and Defila, 2020, p. 108). We use “individual constructs of wanting” (Di Giulio et al., 2012) to emphasize both that needs are always subjectively experienced by individuals (see also Soper, 2006) and that needs depend, in terms of how they are individually delineated and weighted, on social and cultural contexts and are thus also socially constructed.

Alkire, S. (2007). Choosing Dimensions: The Capability Approach and Multidimensional Poverty. Chronic Poverty Research Centre Working Paper No. 88. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1646411

Alkire, S. (2010). Human Development: Definitions, Critiques, and Related Concepts. Background paper for the 2010 Human Development Report. Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative Working Paper 36. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1815263

Blättel-Mink, B., Brohmann, B., Defila, R., Di Giulio, A., Fischer, D., Fuchs, D., et al. (2013). Konsum-Botschaften. Was Forschende für die gesellschaftliche Gestaltung nachhaltigen Konsums empfehlen. Stuttgart: Hirzel. doi: 10.48350/49106

Bornemann, B., Sohre, A., and Burger, P. (2018). Future governance of individual energy consumption behavior change—A framework for reflexive designs. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 35, 140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2017.10.040

Costanza, R., Fisher, B., Ali, S., Beer, C., Bond, L., Boumans, R., et al. (2007). Quality of life: An approach integrating opportunities, human needs, and subjective well-being. Ecol. Econ. 61, 267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.02.023

De Vries, B. J. M., and Petersen, A. C. (2009). Conceptualizing sustainable development: An assessment methodology connecting values, knowledge, worldviews and scenarios. Ecol. Econ. 68, 1006–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.11.015

Defila, R., and Di Giulio, A. (2020). The concept of “consumption corridors” meets society: how an idea for fundamental changes in consumption is received. J. Consum. Policy 43, 315–344. doi: 10.1007/s10603-019-09437-w

Defila, R., and Di Giulio, A. (2021). “Protecting quality of life: Protected Needs as a point of reference for perceived ethical obligation,” in Handbook of Quality of Life and Sustainability, eds. J. Martinez, C. A. Mikkelsen, and R. Phillips (Switzerland: Springer) 253–280. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-50540-0_13

Defila, R., Di Giulio, A., and Ruesch Schweizer, C. (2018). Two souls are dwelling in my breast: Uncovering how individuals in their dual role as consumer-citizen perceive future energy policies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 35, 152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2017.10.021

Di Giulio, A. (2004). Die Idee der Nachhaltigkeit im Verständnis der Vereinten Nationen – Anspruch, Bedeutung und Schwierigkeiten. LIT. Available online at: https://biblio.unibe.ch/download/eldiss/04digiulio_a.pdf

Di Giulio, A. (2008). Ressourcenverbrauch als Bedürfnis? Annäherung an die Bestimmung von Lebensqualität im Kontext einer nachhaltigen Entwicklung. Wissenschaft Umwelt INTERDISZIPLINÄR. 2008, 228–237. Available online at: https://files.fwu.at/Wissenschaft_Umwelt/11_2008/2008_11_energiezukunft.pdf

Di Giulio, A., Brohmann, B., Clausen, J., Defila, R., Fuchs, D., Kaufmann-Hayoz, R., and Koch, A. (2012). “Needs and consumption – a conceptual system and its meaning in the context of sustainability,” in The Nature of Sustainable Consumption and How to Achieve it. Results from the Focal Topic “From Knowledge to Action – New Paths towards Sustainable Consumption” eds. R. Defila, A. Di Giulio, and R. Kaufmann-Hayoz (München: Oekom) 45–66. doi: 10.14512/9783865815330

Di Giulio, A., and Defila, R. (2020). “The ‘good life' and Protected Needs,” in Routledge Handbook of Global Sustainability Governance eds. K. Agni, F. Doris, and H. Anders (London: Routledge) 100–114. doi: 10.4324/9781315170237-9

Di Giulio, A., and Defila, R. (2021). Building the bridge between Protected Needs and consumption corridors. Sustainability 17, 117–134. doi: 10.1080/15487733.2021.1907056

Di Giulio, A., Defila, R., and Kaufmann-Hayoz, R. (2010). Gutes Leben, Bedürfnisse und nachhaltiger Konsum. Umweltpsychologie 14, 10–29. Available online at: https://umps.de/php/artikeldetails.php?id=418

Di Giulio, A., and Fuchs, D. (2014). Sustainable consumption corridors: concept, objections, and responses. GAIA – Ecol. Persp. Sci. Soc. 23, 184–192. doi: 10.14512/gaia.23.S1.6

Di Giulio, A., Ruesch Schweizer, C., Defila, R., Hirsch, P., and Burkhardt-Holm, P. (2019). “These grandmas drove me mad. It was brilliant!” – promising starting points to support citizen competence for sustainable consumption in adults. Sustainability 11, 681. doi: 10.3390/su11030681

Di Giulio, A., Sahakian, M., Anantharaman, M., Saloma, C., Khanna, R., Narasimalu, S., et al. (2022). How the consumption of green public spaces contributes to quality of life: Evidence from four Asian cities. Consumpt. Soc. 1, 375–397. doi: 10.1332/SMTK9540

Doyal, L., and Gough, I. (1991). A theory of human need. Crit. Soc. Policy. 4, 6–38. doi: 10.1177/026101838400401002

Espinosa, C., Pregernig, M., and Fischer, C. (2017). Narrative und Diskurse in der Umweltpolitik: Möglichkeiten und Grenzen ihrer strategischen Nutzung. Zwischenbericht. Umweltbundesamt. Available online at: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/narrative-diskurse-in-der-umweltpolitik (accessed June 26, 2023).

Feola, G. (2014). Narratives of grassroots innovations: A comparison of voluntary simplicity and the transition movement in Italy. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Develop. 8, 250–269. doi: 10.1504/IJISD.2014.066612

Fischer, D., Michelsen, G., Blättel-Mink, B., and Di Giulio, A. (2012). “Sustainable consumption: How to evaluate sustainability in consumption acts,” in The Nature of Sustainable Consumption and How to Achieve it. Results from the Focal Topic “From Knowledge to Action – New Paths towards Sustainable Consumption” eds. R. Defila, A. Di Giulio, and R. Kaufmann-Hayoz (München: Oekom) 67–80. doi: 10.14512/9783865815330

Gearty, M. R., Bradbury-Huang, H., and Reason, P. (2015). Learning history in an open system: Creating histories for sustainable futures. Manag. Learn. 46, 44–66. doi: 10.1177/1350507613501735

Gough, I. (2017). Recomposing consumption: defining necessities for sustainable and equitable well-being. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 375, 20160379. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2016.0379

Han, H., and Ahn, S. W. (2020). Youth mobilization to stop global climate change: Narratives and impact. Sustainability. 12, 4127. doi: 10.3390/su12104127

Harich, J. (2010). Change resistance as the crux of the environmental sustainability problem. Syst. Dynam. Rev. 26, 35–72. doi: 10.1002/sdr.431

Jackson, P., Jager, W., and Stagl, S. (2004). “Beyond insatiability – needs theory, consumption and sustainability,” in The ecological economics of consumption, eds. L. Reisch and I. Røpke (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar) 79–110. doi: 10.4337/9781845423568.00013

Kallbekken, S., and Sælen, H. (2011). Public acceptance for environmental taxes: Self-interest, environmental and distributional concerns. Energy Policy 39, 2966–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2011.03.006

Kaufmann-Hayoz, R., Bamberg, S., Defila, R., Dehmel, C., Di Giulio, A., Jaeger-Erben, M., Matthies, E., Sunderer, G., and Zundel, S. (2012). “Theoretical perspectives on consumer behavior: attempt at establishing an order to the theories,” in The Nature of Sustainable Consumption and How to Achieve It. Results from the focal topic “From Knowledge to Action – New Paths towards Sustainable Consumption” R. Defila, A. Di Giulio, and R. Kaufmann-Hayoz (München: Oekom) 81–112. doi: 10.14512/9783865815330

Lakoff, G. (2010). Why it matters how we frame the environment. Environ. Commun. 4, 70–81. doi: 10.1080/17524030903529749

Lejano, R. P., Tavares-Reager, J., and Berkes, F. (2013). Climate and narrative: Environmental knowledge in everyday life. Environ. Sci. Policy 31, 61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2013.02.009

Manstetten, R. (1996). Zukunftsfähigkeit und Zukunftswürdigkeit – Philosophische Bemerkungen zum Konzept der nachhaltigen Entwicklung. GAIA – Ecol. Persp. Sci. Soc. 5, 291–298. doi: 10.14512/gaia.5.6.5

Max-Neef, M. A., Elizalde, A., and Hopenhayn, M. (1991). “Development and human needs,” in Human scale development: Conception, application and further reflections eds. M. A. Max-Neef (New York, NY, USA: The Apex Press) 13–54.

Mittelmark, M. B., and Bauer, G. F. (2017). “The meanings of salutogenesis,” in The Handbook of Salutogenesis eds. M. B. Mittelmark, S. Sagy, M. Eriksson, G. F. Bauer, J. M. Pelikan, B. Lindström, et al. (Switzerland: Springer) 7–13. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-04600-6_2

Nussbaum, M. (2006). Frontiers of Justice. Disability, Nationality, Species Membership. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1c7zftw

O'Mahony, T. (2022). Toward sustainable wellbeing: advances in contemporary concepts. Front. Sustain. 3, 807984. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2022.807984

Owens, S., and Driffill, L. (2008). How to change attitudes and behaviours in the context of energy. Energy Policy 36, 4412–4418. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2008.09.031

Rauschmayer, F., Omann, I., and Frühmann, J. (2011). “Needs, capabilities and quality of life. Refocusing sustainable development,” in Sustainable development. Capabilities, needs, and well-being, eds. F. Rauschmayer, I. Omann, and J. Frühmann (London: Routledge) 1–24. doi: 10.4324/9780203839744

Ruesch Schweizer, C., and Di Giulio, A. (2016). Nachhaltigkeitswerte: Eine Kultur der Nachhaltigkeit? Sekundäranalyse der Daten aus der StabeNE-Erhebung 2008. Soc. J. Sci. Soc. Interf. 1, 91–104. Available online at: https://openjournals.wu.ac.at/ojs/index.php/socience/index

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 52, 141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 57, 1069–1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Sahakian, M., Anantharaman, M., Di Giulio, A., Saloma, C., Zhang, D., Khanna, R., Narasimalu, S., Favis, A. M., Alfiler, C. A., Narayanan, S., Gao, X., and Li, C. (2020). Green public spaces in the cities of South and Southeast Asia: Protecting needs towards sustainable wellbeing. J. Public Space 5, 89–110. doi: 10.32891/jps.v5i2.1286

Sahakian, M., and Bertho, B. (2018). Exploring emotions and norms around Swiss household energy usage: When methods inform understandings of the social. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 45, 81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2018.06.017

Soper, K. (2006). Conceptualizing needs in the context of consumer politics. J. Consumer Policy 29, 335–372. doi: 10.1007/s10603-006-9017-y

Veland, S., Scoville-Simonds, M., Gram-Hanssen, I., Schorre, A. K., El Khoury, A., Nordbø, M. J., Lynch, A. H., Hochachka, G., and Bjørkan, M. (2018). Narrative matters for sustainability: the transformative role of storytelling in realizing 1.5°C futures. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 31, 41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2017.12.005

Keywords: universal human needs, wellbeing, quality of life, Protected Needs, sustainable wellbeing, ethical obligation, solidarity, narrative

Citation: Di Giulio A, Defila R and Ruesch Schweizer C (2023) Using the Theory of Protected Needs to conceptualize sustainability as ‘caring for human wellbeing': an empirical confirmation of the theory's potential. Front. Sustain. 4:1036666. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2023.1036666

Received: 04 September 2022; Accepted: 20 February 2023;

Published: 10 November 2023.

Edited by:

Laurence Godin, Laval University, CanadaReviewed by:

Lina Isabel Brand Correa, York University, CanadaCopyright © 2023 Di Giulio, Defila and Ruesch Schweizer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Antonietta Di Giulio, YW50b25pZXR0YS5kaWdpdWxpb0B1bmliYXMuY2g=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡ORCID: Antonietta Di Giulio orcid.org/0009-0004-2870-1471

Rico Defila orcid.org/0000-0002-6890-7317

Corinne Ruesch Schweizer orcid.org/0000-0001-7168-4225

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.