- 1Faculty of Economics, Energy and Management Science, Makerere University Business School, Kampala, Uganda

- 2Faculty of Environmental Sciences and Natural Resource Management, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Ås, Norway

- 3School of Economics, College of Business and Management Studies, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

- 4Faculty of Entrepreneurship and Business Administration, Makerere University Business School, Kampala, Uganda

Introduction: The role of gender and gender role differentiation has been of long standing interest and has remained a concern regarding the access and use of energy fuels for cooking in households. Although there seems to be a thin line between gender. However, studies on gender role differentiation in household fuel transition have framed gender as the biological construction of male and female rather than social roles.

Methods: This study used A multinomial probit regression model (MNP) to analyze the effect of gender role differentiation on household transition decisions from high to low-polluting fuels and their implications on education and training in Uganda. The study used the National Household Survey data collected by Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

Findings and discussion: The findings revealed that the gender role differentiation significantly affected household fuel transition decisions. The study concludes by highlighting the implications of such gender role differentiation on education and training in Uganda.

1. Introduction

The role gender and gender differences play in accessing and using energy fuels for cooking in households has been of long-standing interest to both researchers and policymakers (Adjakloe et al., 2021a,b). Although there seems to be a thin line between gender differences and gender, the latter refers to the socially constructed roles of women and men rather than biologically determined differences (Fathallah and Pyakurel, 2020; Jagoe et al., 2020). In regards to household energy fuels, several studies (Choudhuri and Desai, 2020; Shrestha et al., 2020; Adjakloe et al., 2021b) have confirmed the existence of gender differences in household consumption practices, choices, and shifts in energy fuels for cooking. However, these studies have only conceptualized gender to refer to male and or female rather than the social constructions and the differences attached to them.

This study uses structural functionalism theory to explain household fuel transition decision-making. Consistent with Lindsey (2020), this study uses structural functionalism to argue that, in subsistence economies, households are made up of interdependent parts with differing roles which have crucial functions in meeting the basic social needs of the household members in predictable ways. Values surrounding gender roles contribute to the overall social stability, balance, and equilibrium of households in developing economies (Lindsey, 2020, p. 8). Value consensus at the household level is proposed to be a major ingredient in explaining household fuel transition decision-making, since a shift in values can easily threaten social stability. The functionalist model assumes that household wellbeing is deeply rooted in its culture, that is, its values, norms, and beliefs. This means that the welfare, survival, and maintenance of a household at a certain level, largely depends on satisfying certain functional requirements.

Traditionally, in most parts of the developing world and among households that depend on biomass as a main fuel source for cooking, cooking remains primarily a role for women. The responsibility of biomass fuel collection rests heavily on women and girls (Choudhuri and Desai, 2020). In sub-Saharan Africa and Uganda in particular, where 94% of the fuel used for cooking is biomass, the burden of collecting and using this fuel rests largely on women and girls. This seemingly taken-for-granted responsibility significantly narrows the opportunities and time for women to engage in other activities that would support household transition to modern energy fuels (Kyayesimira and Florence, 2021).

Unlike men who, by way of social gender constructions, have more time to engage in income-generating activities like formal employment, few women in the developing world have the opportunity to engage in formal employment and other income-generating activities. Young girls spend time collecting firewood (Nyambane et al., 2014); the time that could have been used in class for studying and learning is now spent in the field trying to access wood fuel while their counterparts, male children, are attending school. Beyond the missed education opportunities for girls and significantly limited opportunities for better income-generating activities, women also rarely have ownership of household and family properties, nor financial resources due to the nature of socially constructed gender differences (Rothblum, 2017). Furthermore, due to the risks they face while collecting and using firewood, women often favor using modern energy fuels, although the lack of ownership over household property (income, land, business), a lack of education, and limited engagement in formal employment significantly limit their say on the nature of the fuel used in the household (Muravyev et al., 2009; World Bank, 2010). Gender differences therefore are seen to manifest more in the areas of education, employment, and the headship of households (Muravyev et al., 2009).

With such differences brought to the fore, it is of paramount importance to separate gender as a social construction from the biological construction of being male or female. Studies on household fuel choices and transition (Fathallah and Pyakurel, 2020; Jagoe et al., 2020) seem to have taken the biological path, ignoring the thinking that gender is about socially constructed roles and the responsibilities and differences that come with them. These social constructions, which change from society to society, may have implications for education and training, which we explore in this study. It appears that in Uganda, there have been no studies that have considered the influence of gender role differentiations on household fuel transition, a gap that this study seeks to close. Therefore, this study seeks to analyze the effect of gender role differentiation on household transition decisions from high- to low-polluting fuels and the implications for education and training in Uganda. The rest of this paper is structured as follows: section two covers methods and materials, section three presents the findings and the discussion, while section four presents the concluding remarks and the implications of the findings for education and training in Uganda.

2. Review of related literature

2.1. Transition toward pro-environmental devices and practices

There is evidence that the use of polluting fuels and conversion technologies has a negative impact on the environment (Kyaw et al., 2020; Cimini and Moresi, 2022). This necessitates transitioning toward pro-environmental devices and practices. However, this requires pointing out the environmental benefits associated with pro-environmental devices and practices, since they impact the attitudes of the households. Cimini and Moresi (2022) pointed out that environmental and warm-glow benefits had a significant positive effect on consumer attitudes toward efficient energy appliances. Earlier empirical work by Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez (2012) recognized the fact that environmental benefits and warm-glow benefits positively enhanced consumer confidence in green energy products. Consistent with Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez (2012), Kopaei et al. (2021) noted that attitude and intentions impacted consumer intentions to adopt home compositing appliances. Similarly, Ertz et al. (2017) in earlier studies explored the importance of attitude when it came to transition. In their investigation, they concluded that attitude was a significantly strong predictor of intentions. Bhutto et al. (2022) investigated the role of self-identity and its effect on consumption values and intentions to adopt green vehicles among Generation Z. They found that functional value (quality) significantly influenced consumer intentions to adopt green vehicles. They emphasized the need to improve consumer values and ethical self-identity as these eventually contributed to the adoption of green vehicles. The study concluded that functional benefits, such as reliability, comfort, and usability among others would influence the intentions of the consumers to adopt green vehicles.

2.2. Review of literature on energy/fuel transition

Looking at household energy transition, Shari et al. (2022), in their study “Modern cooking energy transition in Nigeria: policy implications for developing countries,” noted that without significant policy interventions, not all households would switch to modern cooking. Therefore, to accelerate the diffusion and adoption of modern cooking fuels in developing countries, potent policies supporting adoption should be emphasized. Earlier studies (Sehjpal et al., 2014) argued that while macro-policies provided important guidelines and necessary frameworks, implementation strategies should also be designed at local levels through a participatory approach that made energy an integral part of the developing paradigm. Similarly, after investigating cooking gas adoption and the impact of India's Ujjwala programme in rural Karnataka, Kar et al. (2019) concluded that in order to encourage full transition to more modern fuels (LPG), mid-course revision of policies should be encouraged to allow regular-use LPG for all consumers.

Other than significant policy interventions Edomah and Ndulue (2020) and Shari et al. (2022), further emphasized that governments and communities must re-evaluate the policy levers used in directing, managing, and shaping changes in energy systems to allow a more permanent transition in energy consumption patterns. Coelho et al. (2018) reviewed energy transition history of fuel wood replacement for LPG in Brazilian households and its impacts in the country between 1920 and 2016 with the aim of identifying key policy implications. They recommended local governments developed and implemented new policies that provided more equitable access to LPG for low-income groups. They further concluded that there was need to go beyond the prevailing government fuel and social policies by introducing subsidies or other forms of financial support to fully replace fuel wood with LPG for cooking.

2.3. Review of literature on gender role differentiation

Gender refers to the socially constructed differences among individuals regarding their attitudes, behaviors, and social identities. In general, gender encompasses the set of norms and relations that determine how individuals are expected to behave and what they can and cannot do. These social differences are learnt in different circumstances and conditions and are influenced by historical, religious, economic, and cultural realities (Verena et al., 2022).

Gender differences are rooted in socialization and responsibility, and yet the headship of most households in rural low-income countries are headed by men. This implies that decisions are made by men who own and have a say in family assets and wealth ownership. Gender accounts for crucial roles from a social aspect and energy-saving process analysis because men and women have different needs. Existing gender norms, including the power relations between them, are likely to focus less on the benefits of women in most countries where socially and culturally defined gender norms have created barriers to energy-related activities (Shrestha et al., 2021). The pre-defined norms that are not in favor of women engaging in energy-related activities that would improve women's welfare exacerbate poverty among women (ENERGIA, 2019).

Remarkably, in their study “Review on the importance gender perspective in household energy saving and energy transition for sustainability,” Shrestha et al. (2021) concluded that reviewing household energy-saving behavior while keeping gender roles in consideration led to gender-sensitive energy policies that had a remarkable role in changing people's mindset and perceptions to increase motivation, gender participation, and change habits. Ultimately, gender energy-saving behavior has the strength to achieve SDG goal 7, in terms of energy security, accessibility, and affordability for all, thus having a positive impact and reducing energy poverty.

Nguyen and Su (2021) noted that there is a link between energy poverty and caregivers, and these people are mostly represented by women. They further argued that energy poverty in these population groups is not always related to education but to the impossibility of redressing domestic labors; there are gender differences in subjective wellbeing due to the construction of women's identity being coupled to household needs. Heredia et al. (2022), through analyzing interview responses, noted that the feminization of energy poverty is just another example of gender inequality. In most economies, women are involved highly in energy activities in households chores but have less gender participation in gender decisions (Shrestha et al., 2021).

Interestingly, Robinson et al. (2019) investigated the partialities of gender and energy poverty in England. Five dimensions of gendered energy-poverty vulnerabilities were analyzed, including: exclusion from the economy; time-consuming and unpaid reproductive, caring, or domestic roles; exposure to physiological and mental health impacts; a lack of social protection during life course; and coping and helping others to cope. The findings suggested that gendered vulnerabilities appear to increase energy poverty in England. Access to modern energy can have significant benefits in improving the quality of life of women but these benefits may only be realized if energy projects are designed and targeted after careful attention is given to local energy availability and household decision-making processes (Köhlin et al., 2011; Clancy et al., 2012). In most economies, women are highly involved in energy activities in households chores but have less gender participation in gender decisions (Shrestha et al., 2021; Heredia et al., 2022). In most countries, socially and culturally defined gender norms have created barriers to energy-related activities (Shrestha et al., 2021). Matinga et al. (2018) attested to this notion and asserted that a lack of understanding of gender from a relational perspective focusing on both women and men impedes conclusions on empowerment in terms of whether increased access to modern energy in the formal food sector contributes to closing the gender gap.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Data sources and collection procedures

The data used in the study was collected by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBoS). The Uganda Bureau of Statistics is mandated by an Act of Parliament (Act. 1998) to develop and maintain a National Statistical System to ensure collection, analysis, and publication of integrated, relevant, reliable, and timely statistical information. The study used the most recent cross-section national household survey data (2019/2020). These data are rich and contain the variables relevant for this study.

3.2. Study variables

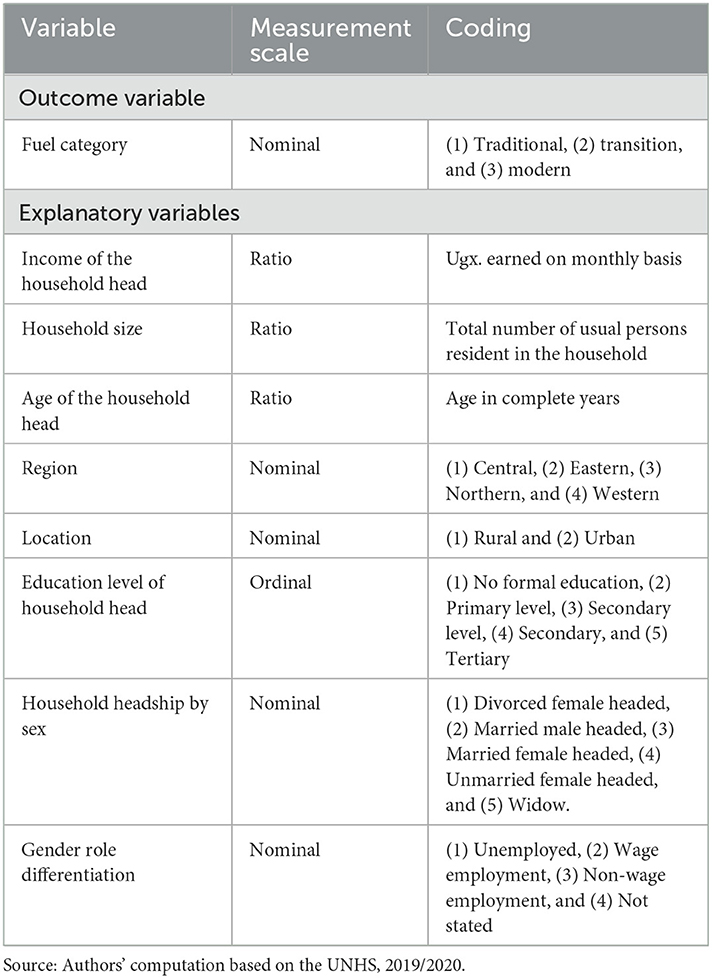

Table 1 shows the variables included in this study and how they were measured and coded. The outcome variables were categorical in nature and classified as traditional, transition, and modern fuels. This classification was derived following the energy ladder hypothesis, i.e., modern fuels (e.g., electricity and LPG), transition fuels (e.g., kerosene and efficient methods of burning wood fuel) and traditional fuels (e.g., charcoal, firewood, dung, and plant wastes) (Leach, 1992; Karimu, 2015; Choumert-Nkolo et al., 2019). Traditional fuels are those that release carbondioxide and other harmful pollutants into the air (Islam et al., 2022). Transition fuels are those that provide some health benefits due to substantial reductions in emissions. Modern fuels, on the other hand, are fuels with very low levels of polluting emissions when burned. Fuels are classified as modern if they meet the emission rate targets in the World Health Organization guidelines (World Health Organization, 2014). The explanatory variables include: household income, age of the household head, household size, level of education of the household head, headship, role differentiation, region, and location, as shown in Table 1.

Data analysis was done using the STATA statistical package, version 15.0. A multinomial probit regression model (MNP) was used to estimate the effect of gender differences on household fuel transition decision-making. Unlike the multinomial logit model, multinomial probit regression was preferred because it does not assume independence of irrelevant alternatives, i.e., the relative probability of a household choosing between two options is independent. This shows that the multinomial probit model provides more accurate results (Kropko, 2008). Furthermore, multinomial probit regression does not only effectively predict probabilities for multiple choices but is also suitable for unordered data (Njong and Johannes, 2011). This approach was also used by several other scholars (Al-Farsi et al., 2007) because of its practicability in predicting probability for multiple choices.

3.3. Theoretical model

The theoretical model for household demand for cooking fuels was derived from the household utility maximization principle (Amacher et al., 1999), where utility is maximized subject to a set of both economic and non-economic constraints, as presented in Equation 1. Economic constraints include fuel price and budget (household income), while non-economic constraints include household characteristics and social factors. Assuming that a household consumes a variety of goods with different quantities and prices, the functional equation for the study takes the form:

where U*(Pw, PA, Y, Ω) is the maximum attainable utility, Qw is the units of fuel purchased, Pw is the per-unit price of energy fuel purchased, PA is the unit price of other alternatives, Y is household income, Ω is the set of social factors, and QA indicates the units of alternatives purchased. In this study, the social factors considered include: household size, household age, education level, gender roles, and headship, while the economic factors include household income, since in this study cooking fuel is conceptualized as a consumption good. To complete the functional equation above, a demand theory was adopted to explain the factors that influence the consumption of a particular good. The demand theory stresses that the demand for a good is generally driven by two factors: utility and the ability to pay for such a good. In this case, the utility takes the form of the Cobb-Douglas utility function (with two goods: X1 and other goods X2), where X1 and X2 represent energy fuel and other goods, respectively, as shown below:

The two goods have price tags, such that P1 and P2 are the prices of good one and good two, respectively. Note that a household is endowed with wealth M, hence the constraint. Thus, a household spend on the goods is subject to constraint, as in Equation 3:

where P1 and P2 are the prices for goods and respectively.

The maximization problem for the household is therefore formulated as follows:

The Lagrangian function was set up as in Equation 5 and used to solve the optimization problem results to MRS (marginal rate of substitution).

The constraint m was used to solve for X1 yields:

Equation 6 is the Marshallian demand function, which represents the household demand for cooking fuel (X1).

3.4. Econometric model

Whereas, cooking fuel was conceptualized as a consumption good in this study, it only enters the utility function indirectly through food consumption. Suppose that household í faces j alternatives of cooking fuel (where j = 1, 2, and 3), the indirect utility derived from each of the j alternatives is defined by the term víj. The indirect utility function is then divided into , where xí is the vector of all variables in the model. Thus, the indirect utility for alternative j for household í is presented as:

where unobservable εij is assumed to have a normal distribution with V ~N[0, Σ], and βj is the vector of the unknown parameters. x is the vector of the explanatory variables characterizing both the alternative j and the household i. εij is the normally distributed random error term of mean zero assumed to be correlated with errors associated with the other alternatives j, j = 1, …j, j ≠ i.

We assumed that there are m categories of fuel and that household i chooses fuel alternative j if Víj is highest for j as expressed in Equation 8:

The probability that household i selects a particular fuel is expressed as:

where = - and = - . For the case of Pi2 and Pi3, similar expressions can be obtained. εij was assumed to be a joint normal density function which is defined as f (εij) = f (εi1, εi2, εi3). Let yij denote a discrete choice outcome variable that takes a value of 1 if household i chooses fuel j and 0 otherwise. The cumulative probability for the choice of the first alternative fuel by household i is expressed in Equation 10:

The terms = ) and = are specific to the first fuel category and the choice proability of household i choosing fuel alternative j is given by Píj = Pr[yi = j] =. But takes a similar expression, as in Equation 11. Finally, the log likelihood function for a sample of N independent households with j alternatives can then be expressed as:

pij is estimated in a similar way to Equation 12, using simulation methods and substituted into a log likelihood function which is maximized to obtain the parametric estimates for the β's.

3.5. Specification of the model

Following Equation (7), the empirical model to be estimated was specified as:

where β's are the coefficients of the equation and ε is the error term. lnincome = household income, hhsize = household size, hage = age of the household head, roledif = role differentiation, and FC = fuel category.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Descriptive statistics

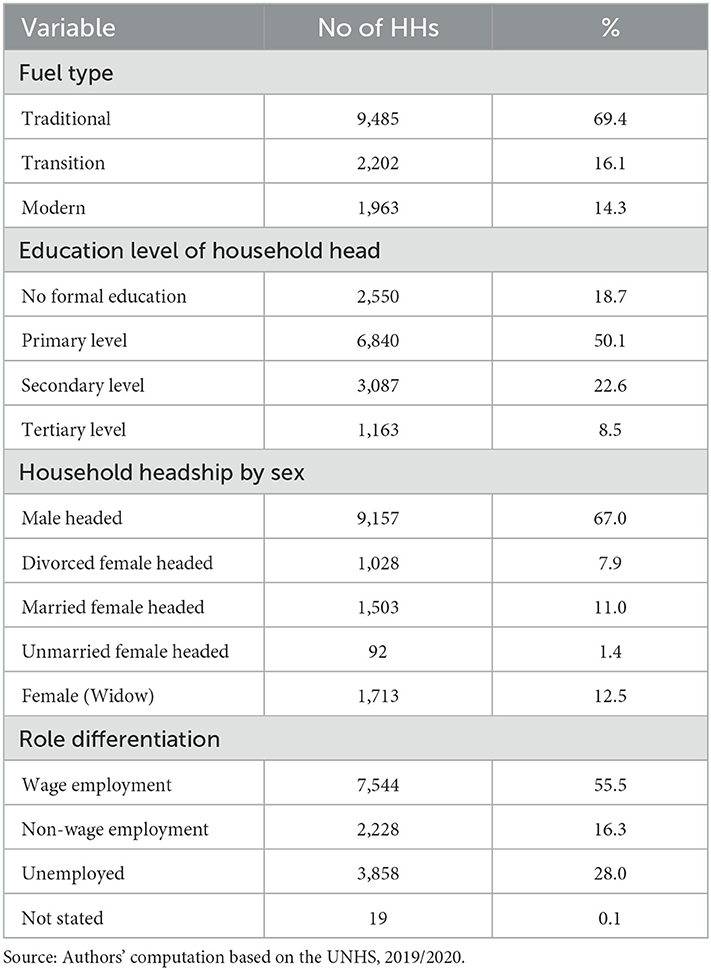

Table 2 shows that, of the 13,649 households, only 14.3% used modern fuels for cooking while the majority (69.4%) relied on traditional fuels for cooking.

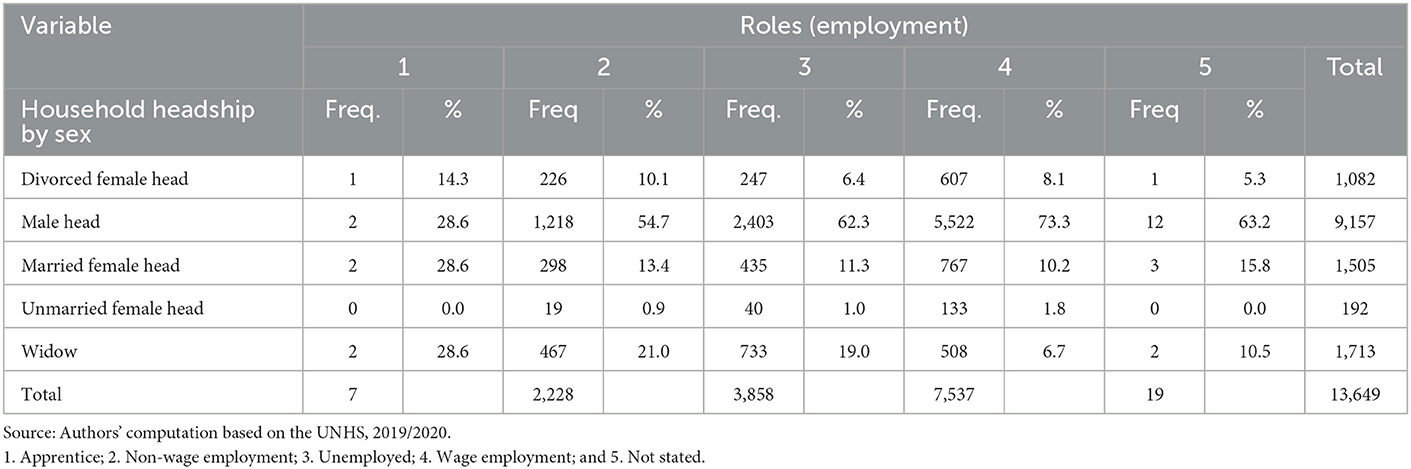

Households headed by married males, married females, unmarried females, and widowed females were 67.0, 11.0, 1.4, and 12.5%, respectively. In terms of the education level of the household head, about 18.7% of household heads had no formal education. However, the majority of the household heads (50.1%) had attained a formal education to primary level. Household heads that had attained a secondary education and those that attained a tertiary education were 22.6 and 8.5%, respectively. This shows that the majority of household heads had attained formal education to at least primary level.

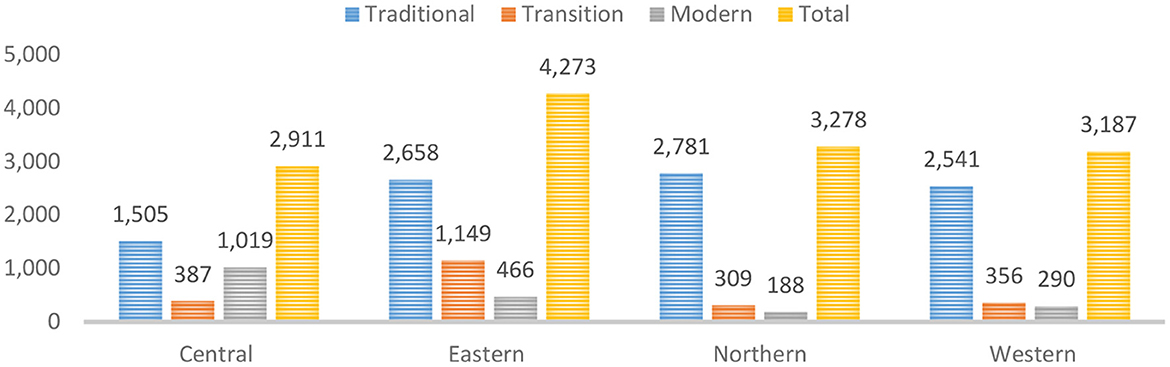

Furthermore, in terms of employment (role differentiation), about 55.5% of the household heads were involved in wage employment, while 16% were in non-wage employment. The household heads who were unemployed were 28%, and those who did not disclose their employment status were 0.1%. The households included in the survey were spread across four regions in Uganda. About 21.3% were from the Central region, while 31.3% were from the Eastern region. Similarly, 24 and 23.3% of the households were from Northern and Western regions, respectively.

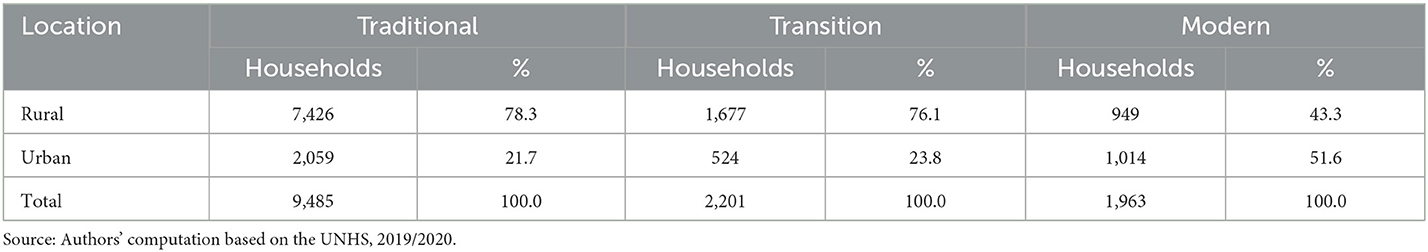

Figure 1 shows a large percentage of the households that have transitioned to using modern fuel for cooking were from the Central region, while the Northern region presented the least number of households using modern fuels for cooking. Similarly, the largest number of households depending on traditional fuels for cooking were from the Northern region, followed by the Eastern region. From Table 3, we noted that over 78% of the 10,052 households in rural areas largely depended on traditional fuel for cooking. Furthermore, out of the 10,052 households in rural areas, only about 9.4% used modern fuels for cooking. Similarly, of the 3,597 households in urban areas, 21.7, 23.8, and 51.6% used traditional, transition, and modern fuels for cooking, respectively. While there was an improved number of households using modern fuels for cooking, we noted that there was also a significant number of households using traditional fuel despite the presence of modern options like electricity and LPG in urban areas.

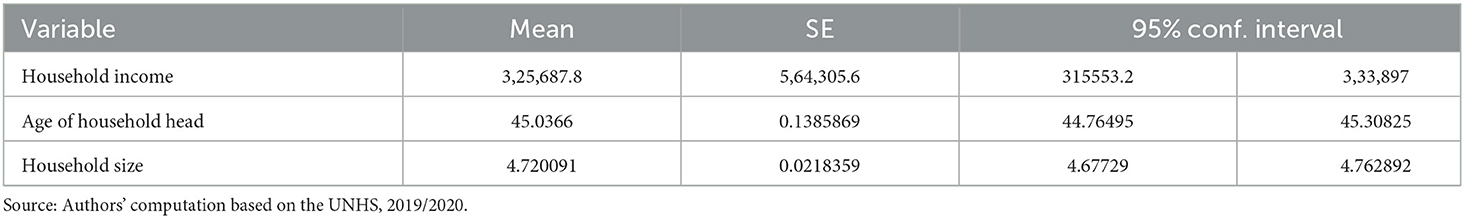

4.2. Mean estimation of income, size, and age of household head

From data analysis (see Table 4), the average age of the household head was 45 years and the average household size was 4.72 persons per household.

The average monthly household income was UGX 325687.8. This amount is ~$2.8, which is below the international poverty threshold of $3.2. This explains why nearly three-quarters of Ugandans are categorized as poor.

4.3. Differences arising from social constructions

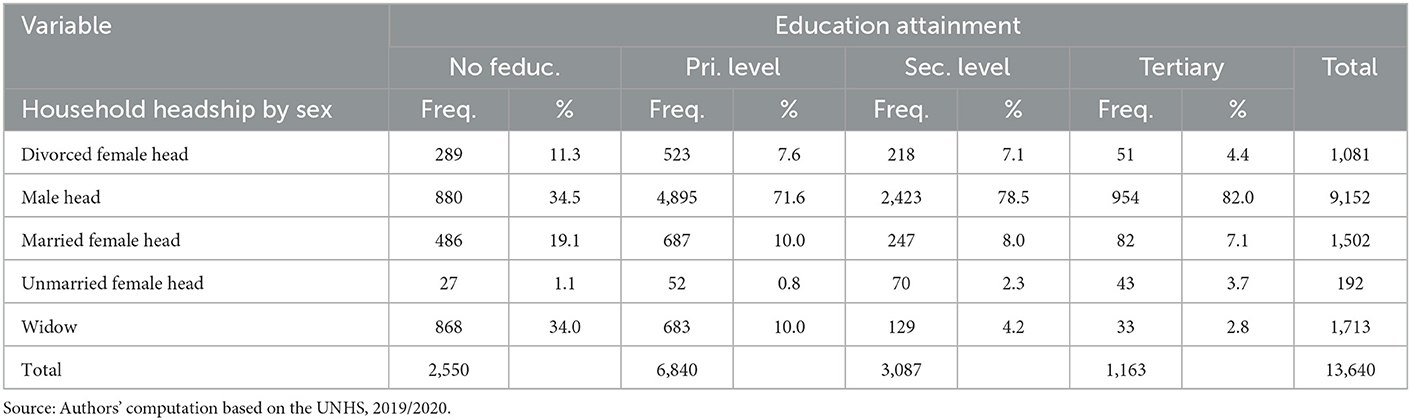

Viewing gender as a social construction, this study focused on differences in the context of education and gender-role differentiation. In terms of gender and education, we focused on the differences in education outcomes, particularly in education attainment: that is, how far young men and women go within the education system. The findings in Table 5 show that more male (71.6%) than female (28.4%) household heads had attained a primary school level of education.

The findings further revealed that more male (78.5%) than female (21.5%) household heads had attained a secondary education level. Similarly, more male (82.0%) than female household heads had attained a tertiary education. These findings suggest that more males had the opportunity to attain a formal education compared to females. These results conformed to the societal construction of gender roles and responsibilities assigned to males and females. Society frames girls as responsible for household chores, such as cooking and housekeeping-related activities, thus denying them the opportunity to attend school (Choudhuri and Desai, 2020). There is a persistent viewpoint among most rural communities that education is not meant for girls but only for boys (Mitra et al., 2022). This exacerbates the problem of gender inequality in education outcomes. Most parents prefer their sons to attain education rather than their daughters. They argue that, in the end, the sons will provide financial help to them in the future, as opposed to daughters, who will get married and instead may not be available to offer help in the future (Akabayashi et al., 2020).

This could explain why there are large numbers of educated male headed households compared to female headed households. Our findings complement other scholarly work that report gender differences in terms of education attainment. The study by Evans et al. (2021) on “Gender gaps in education: the long view” reported that women had less educational attainment than men as a result of gender role differentiation in more than two-thirds of countries globally.

Regarding gender and gender role differentiation on employment, the findings in Table 5 show a significant level of differences between male and female household heads. More male (73.3%) household heads than female (26.7%) house heads had wage roles leading to wage remuneration. Formal employment is closely linked with formal education. In addition, the findings indicated that more males attained formal education than females. This could explain why more male household heads (see Table 5) are in roles leading to formal wage remuneration than female heads. These findings agreed with existing scholarly work. For example, Humpert and Pfeifer (2013) reported that women in all age groups had low employment rates compared to men. Although there could be other factors contributing to the low employment of women, low education levels as a result of social construction of gender is one of them (Mitra et al., 2022). Mascherini et al. (2016) also reported that women's participation in the labor market is still low despite the effort to create gender equality in employment.

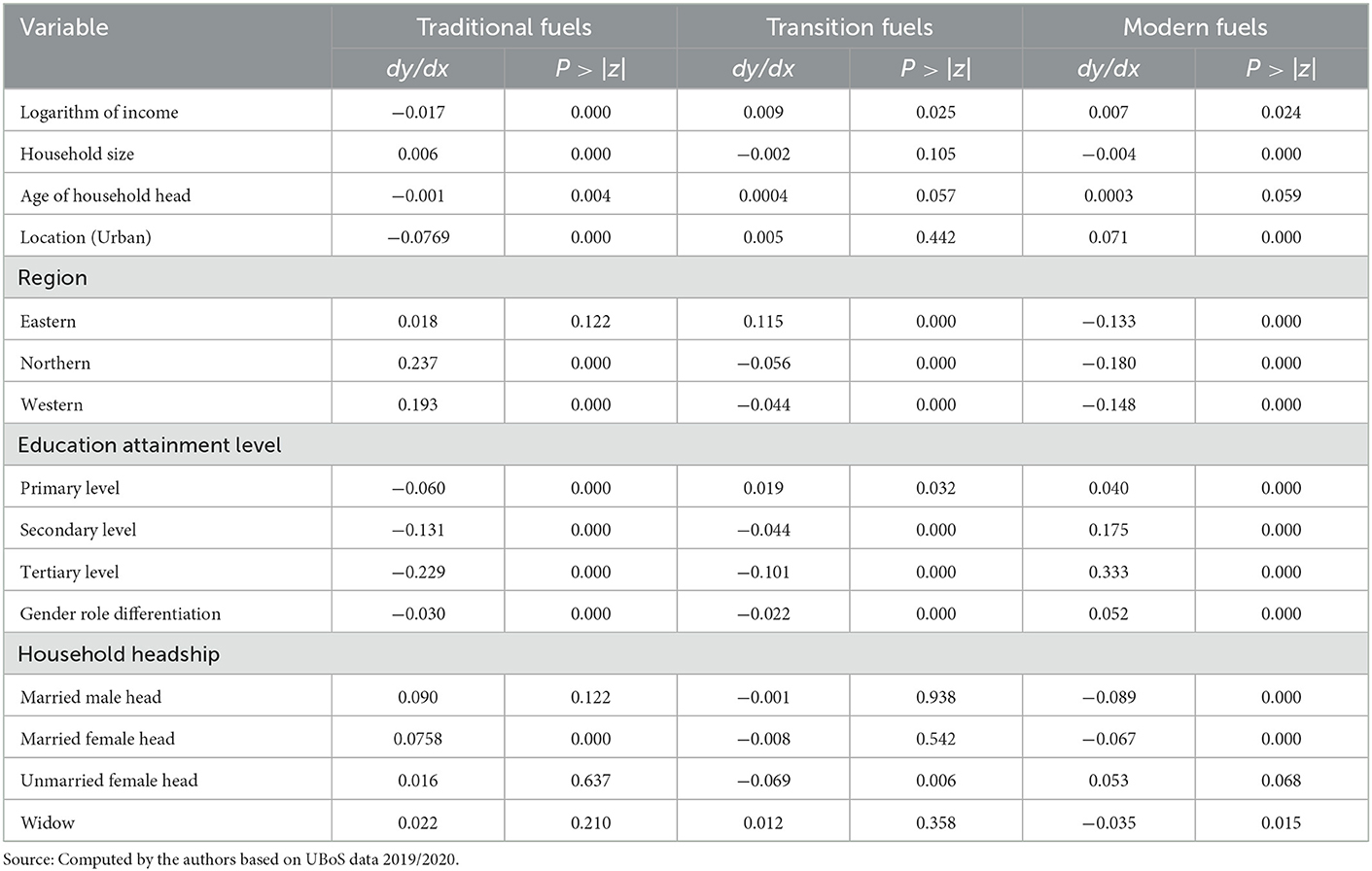

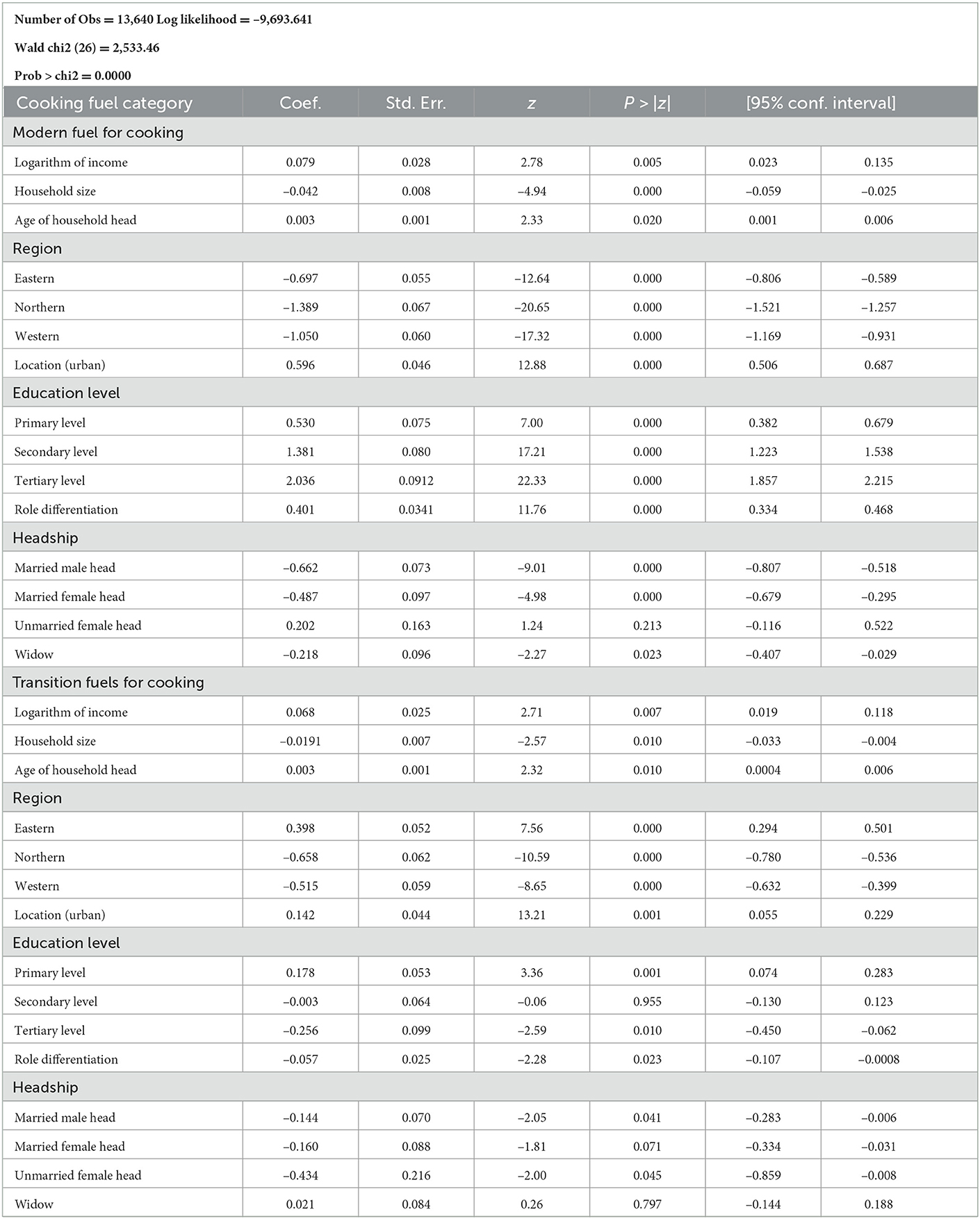

4.4. Marginal effect coefficients and predicted probabilities

The estimated marginal effects coefficients and predicted probabilities of the multinomial probit regression are presented in Table 6 and Table A1. The results showed that income was a significant factor in determining the probability of choosing a particular category of cooking fuel. The results showed that an increase in households income by one percent reduced the probability of the household choosing traditional fuels for cooking by −1.7% but increased the probability of choosing transition fuels and modern fuels by 0.9 and 0.7%, respectively. The implication of this result is that higher the household income, the more likely that the household can transit to using modern fuels and transition fuels in relation to traditional fuels. These findings are in line with the energy ladder hypothesis (Leach, 1992) which states that, as household income increases, households shift from traditional to modern fuels for cooking.

The study findings further revealed that household size had a negative effect on the choice probability for modern fuels but positive effect for traditional and transition fuels. The implication here was that an increase of the household size by one member reduced the likelihood of the household transiting to modern and transition fuels by −0.4 and −0.2%, respectively, but increased the likelihood of the household using traditional fuel by 0.6%. Household size plays a key role in household fuel transition decisions (Muller and Yan, 2016). Meikle and Bannister (2005) reported that household size along with other household socioeconomic factors, such as income and the age of the household head, determined the type and consumption levels of particular fuels. Fethi and Rahuma (2019) agreed with this position when they noted that household size affected the household preferences for modern fuels. Joshi and Bohara (2017) reported that, as household size increased, households became skeptical toward switching to modern fuels. While the effect of household size on fuel switching still remains ambiguous (Muller and Yan, 2016), several studies (Rao and Reddy, 2007; Pandey and Chaubal, 2011; Özcan et al., 2013) have reported that larger households have always preferred traditional fuels over modern fuels. One possible argument is that households with bigger number of occupants are normally poorer and therefore cannot afford modern fuels. Our study concurred with this finding that additional members in the household increased the expenditure of the household and, as a result, households resorted to cheaper (traditional) fuels to meet their fuel needs.

The results further showed that age was a significant factor in determining the probability of choosing a particular category of cooking fuel. The results showed that an increase in age by 1 year increased the probability of the household using traditional, transition, and modern fuels by 0.01, 0.1, and 0.06%, respectively. Furthermore, the study revealed that the location of the household had a significant impact on household energy transition. The probability of choosing modern fuels by households living in urban areas increased by 0.8%. On the other hand, the probability of urban households choosing traditional fuels for cooking reduced by 7.2%. Similarly, households in the Eastern, Northern, and Western regions of Uganda had their choice probability of transiting to modern fuels reduced by −1.3, −1.8, and −1.4%, respectively.

The study findings revealed that the education level (see Table 5) of the household head was statistically significant in influencing household fuel transition decisions. These findings agreed with those of Riahi et al. (2017), who noted that the education level of the household head had an impact on household transition decisions. Attainment of a primary level of education reduced the likelihood of a household continuing to use traditional fuels by −6%, and increased the probability of moving to transition and modern fuels by 1.9 and 4%, respectively. Attainment of a secondary education level reduced the probability of households using traditional and transition fuels by −13.1 and −4.4%, and increased the probability of households moving to modern fuel by 17.5%. Findings further showed that the attainment of a tertiary level of education by the household head reduced the probability of using traditional fuels and transition fuels by −22.9 and −10.1%, and increased the probability of transiting to modern fuel by 33.3%. These findings confirmed the results obtained by Mahmood (2020). Gould et al. (2020) noted the attainment of a primary education reduced the probability of households choosing to use traditional fuels, whereas Mahmood (2020) further noted that the attainment of a secondary education increased the probability of households choosing modern fuels. On the contrary, our findings indicated that the attainment of a secondary education rather increased the probability of using transition fuels but reduced the probability of using modern fuels. This could be attributed to the fact that a secondary level of education remains rather low and the income of such secondary graduates may still be too low to influence the adoption of modern fuels.

The study findings revealed that gender role differentiation significantly affected household fuel transition decision-making. The findings indicated a negative but statistically significant relationship between gender role differentiation and traditional fuels. This means that increased gender role differentiation reduced the probability of households using traditional fuels by 3%. One possible explanation lies in the widespread sociocultural upbringing practices in most parts of Uganda, which draws a distinction between male and female roles. Gender socialization provides messages and customs that must be followed by females or a males in society (Steinbacher and Holmes, 1987). The findings further showed a negative relationship between gender role differentiation and transition fuels. An increase in gender role differentiation reduced the probability of households choosing transition fuels by −2.2%. This means that an increase in gender role differentiation reduced the probability of households choosing transition fuels. On the other hand, the findings indicated that increased differentiation of gender roles increased the probability of households using modern fuels by 5.2%. One possible explanation for this is linked to the societal expectations for men to provide and for women to take the lion's share of child rearing and household tasks. In the event that men do not provide for their household, households may opt for cheaper traditional fuel choices (Oláh, 2001).

The results also showed that household headship by sex was a significant determinant of household energy transition decision-making (see Table 7). The estimated marginal effects on married headed households, married female headed, and widow-headed households reduced the choice probability for modern cooking fuels by −8.9, −6.7, and −3.5% respectively. A household headed by unmarried female heads increased the choice probability for modern fuels by 5.3%. These findings were in agreement with the literature that the headship of the household had an impact on household fuel choices and use decisions (Ali, 2020). In his study “Household Energy Use Among Female-Headed Households in Urban Ethiopia: Key Issues for the Uplift of Women,” Ali noted that most female-headed households were unable to use modern cooking fuels (modern fuels) because of limited access to modern end-use technologies. The findings regarding households being headed by married females had no effect on the likelihood of a household choosing to use modern fuels. Furthermore, households headed by unmarried females and widows had no effect on the probability of households' fuel transition decisions.

5. The implications of socially constructed gender differences on education and training

The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of gender difference on household fuel transition decisions and subsequently state the implications of the findings on education and training. As mentioned earlier, gender is defined as a system of socially defined roles, privileges, attributes, and relationships (Clancy and Feenstra, 2019). These attributes, relationships, and roles are learned but not biologically defined (Clancy and Feenstra, 2019). It is important to note that gender differences manifest glaringly in the aspects of education, household headship, and ownership of household assets, among other socioeconomic and political contexts.

5.1. Theoretical implications

The findings from our study confirmed that structural functionalism theory provides an explanation of the role of gender differences on household energy transition decision-making. This is because the theory argues that households are made up of interdependent parts with differing roles which have crucial functions in meeting the basic social needs of the household members. The long lasting roles that the society assigns to different members of a household are differentiated based on gender. Women are highly involved in energy activities concerning household-chore roles, but have less gender participation in gender decisions (Shrestha et al., 2021; Heredia et al., 2022). This has implications in household decision-making, since in most cases men are charged with the household decision-making responsibility. In most countries, socially and culturally defined gender norms have created barriers to energy-related activities (Shrestha et al., 2021). For fuel transition decision-making, value consensus is a critical ingredient since a shift in values can easily threaten social stability. The absence of social stability in the households affects household decisions regarding energy transition.

5.2. Implications for education and training in Uganda

Education influences the decisions of the household to adopt modern energy fuels through the raising of awareness of the dangers of using traditional cooking fuels. This increases the opportunity cost of the collection of traditional fuels for educated household heads (Aryal et al., 2019; Rahut et al., 2019, 2020; Jaiswal and Meshram, 2021; Wall et al., 2021; Mothala et al., 2022). Our study findings were in agreement with the notion above. Our findings revealed a significant relationship between education and household energy transition decision-making. This implies that an inclusive education should be encouraged to allow all children to attain at least some level of education so as to appreciate the importance of using modern fuels as opposed to traditional fuels to meet household fuel needs. Therefore, from the findings, it is critical to ensure and promote the attainment of primary, secondary, and tertiary education for all citizens. The government's efforts to provide free universal primary and secondary education should be strengthened to allow all citizens to attain some level of formal education. In this way, every household would recognize the danger of using traditional fuels and turn to using modern fuels.

6. Conclusion

6.1. Concluding remarks

This study sought to establish the effect of gender differences on household fuel transition decisions. The study highlighted the importance of household headship and education level of the household head in household fuel transitions. Our findings indeed confirmed that gender differences in terms of social constructions manifest in areas of education and household headship and this affects household fuel transition decisions. The study further concurred with the existing literature that household income, age of the household head, and household size affected household fuel transition decisions. We conclude by recommending that the already existing government interventions to provide free universal primary and secondary education should be strengthened to ensure that household members understand the importance of modern fuels for cooking and lighting. The authors also hope that policymakers and other responsible stakeholders review, revise, and or formulate policies that empower women so that they are able to move to a position from where they can afford to use modern fuels in their households.

6.2. Limitations of the study and direction for future research

This study used cross-section survey data from the Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Similar studies can be done using panel survey data to understand the behavior of households over time. Our study was quantitative in nature. Other scholars may consider carrying out similar studies using qualitative techniques. This will help discover more insights from respondents on how gender role differentiations influence household energy transition decisions.

Author's note

In the study of household energy transition, the existing studies have framed gender in the context of biological construction of being male or female. In our study we argue that gender goes beyond just being male and female construction but rather includes the social roles construction where the society has provided different roles to men and women (gender role differentiation). This gender role differentiation has an impact on the decisions taken in as far as household fuel transition is concerned. Our study intended to determine the effect of gender role differentiation on household fuel transitions and as well indicate the implications it has on education and training in Uganda.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adjakloe, Y. D. A., Boateng, E. N. K., Osei, S. A., and Agyapong, F. (2021a). Gender and households' choice of clean energy: a case of the Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana. Soc. Sci. Hum. Open 4, 100227. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100227

Adjakloe, Y. D. A., Osei, S. A., Boateng, E. N. K., Agyapong, F., Koranteng, C., and Baidoo, A. N. A. (2021b). Household's awareness and willingness to use renewable energy: a study of Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 40, 430–447. doi: 10.1080/14786451.2020.1807551

Akabayashi, H., Nozaki, K., Yukawa, S., and Li, W. (2020). Gender differences in educational outcomes and the effect of family background: a comparative perspective from East Asia. Chin. J. Sociol. 6, 315–335. doi: 10.1177/2057150X20912581

Al-Farsi, M., Alasalvar, C., Al-Abid, M., Al-Shoaily, K., Al-Amry, M., and Al-Rawahy, F. (2007). Compositional and functional characteristics of dates, syrups, and their by-products. Food Chem. 104, 943–947. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.12.051

Ali, A. M. (2020). Household energy use among female-headed households in urban ethiopia: key issues for the uplift of women. Indian J. Hum. Dev. 14, 460–480. doi: 10.1177/0973703020967897

Amacher, G. S., Hyde, W. F., and Kanel, K. R. (1999). Nepali fuelwood production and consumption: Regional and household distinctions, substitution and successful intervention. J. Develop. Stud. 35, 138–163.

Aryal, J. P., Rahut, D. B., Mottaleb, K. A., and Ali, A. (2019). Gender and household energy choice using exogenous switching treatment regression: evidence from Bhutan. Environ. Dev. 30, 61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2019.04.003

Bhutto, M. Y., Khan, M. A., Ertz, M., and Sun, H. (2022). Investigating the role of ethical self-identity and its effect on consumption values and intentions to adopt green vehicles among generation Z. Sustainability 14, 15. doi: 10.3390/su14053015

Choudhuri, P., and Desai, S. (2020). Gender inequalities and household fuel choice in India. J. Clean. Prod. 265, 121487. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121487

Choumert-Nkolo, J., Combes Motel, P., and Le Roux, L. (2019). Stacking up the ladder: a panel data analysis of Tanzanian household energy choices. World Dev. 115, 222–235. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.11.016

Cimini, A., and Moresi, M. (2022). Environmental impact of the main household cooking systems: a survey. Ital. J. Food Sci. 34, 86–113. doi: 10.15586/ijfs.v34i1.2170

Clancy, J., and Feenstra, M. (2019). Women, Gender Equality and the Energy Transition in the EU. Available online at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/supporting-analyses

Clancy, J., Winther, T., Matinga, M., and Oparaocha, S. (2012). “Gender Equity in Access to and Benefits from Modern Energy and Improved Energy Technologies,” in World Development Report: Gender Equality and Development, January.

Coelho, S. T., Sanches-Pereira, A., Tudeschini, L. G., and Goldemberg, J. (2018). The energy transition history of fuelwood replacement for liquefied petroleum gas in Brazilian households from 1920 to 2016. Energy Policy 123, 41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2018.08.041

Edomah, N., and Ndulue, G. (2020). Energy transition in a lockdown: an analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on changes in electricity demand in Lagos Nigeria. Global Trans. 2, 127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.glt.2020.07.002

ENERGIA (2019). Gender in the Transition to Sustainable Energy for All: From Evidence to Inclusive Policies. Herndon: ENERGIA, 1–105. Available online at: https://www.energia.org/cm2/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Gender-in-the-transition-to-sustainable-energy-for-all-From-evidence-to-inclusive-policies_FINAL.pdf

Ertz, M., Huang, R., Jo, M. S., Karakas, F., and Sarigöllü, E. (2017). From single-use to multi-use: study of consumers' behavior toward consumption of reusable containers. J. Environ. Manag. 193, 334–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.01.060

Evans, D. K., Akmal, M., and Jakiela, P. (2021). Gender gaps in education: the long view. IZA J. Dev. Migrat. 12, 1. doi: 10.2478/izajodm-2021-0001

Fathallah, J., and Pyakurel, P. (2020). Addressing gender in energy studies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 65, 101461. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101461

Fethi, S., and Rahuma, A. (2019). The role of eco-innovation on CO2 emission reduction in an extended version of the environmental Kuznets curve: evidence from the top 20 refined oil exporting countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 30145–30153.

Gould, C. F., Urpelainen, J., and Hopkins, S. A. I. S. J. (2020). The role of education and attitudes in cooking fuel choice: evidence from two states in India. Energy Sustain. Dev. 54, 36–50. doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2019.09.003

Hartmann, P., and Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. (2012). Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: the roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. J. Bus. Res. 65, 1254–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.11.001

Heredia, M. G., Sánchez, C. S. G., Peiró, M. N., Fernández, A. S., López-Bueno, J. A., and Muñoz, G. G. (2022). Mainstreaming a gender perspective into the study of energy poverty in the city of Madrid. Energy Sustain. Dev. 70, 290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2022.08.007

Humpert, S., and Pfeifer, C. (2013). Explaining age and gender differences in employment rates: a labor supply-side perspective. J. Labour Market Res. 46, 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s12651-012-0108-8

Islam, S., Upadhyay, A. K., Mohanty, S. K., Pedgaonkar, S. P., Maurer, J., and O'Donnell, O. (2022). Use of unclean cooking fuels and visual impairment of older adults in India: a nationally representative population-based study. Environ. Int. 165, 107302. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2022.107302

Jagoe, K., Rossanese, M., Charron, D., Rouse, J., Waweru, F., Waruguru, M. A., et al. (2020). Sharing the burden: shifts in family time use, agency and gender dynamics after introduction of new cookstoves in rural Kenya. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 64, 101413. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2019.101413

Jaiswal, V. B., and Meshram, P. U. (2021). Behavioral change in determinants of the choice of fuels amongst rural households after the introduction of clean fuel program: a district-level case study. Global Chall. 5, 2000004. doi: 10.1002/gch2.202000004

Joshi, J., and Bohara, A. K. (2017). Household preferences for cooking fuels and inter-fuel substitutions: Unlocking the modern fuels in the Nepalese household. Energ. Policy. 107, 507–523. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2017.05.031

Kar, A., Pachauri, S., Bailis, R., and Zerriffi, H. (2019). Using sales data to assess cooking gas adoption and the impact of India's Ujjwala programme in rural Karnataka. Nat. Energy 4, 806–814. doi: 10.1038/s41560-019-0429-8

Karimu, A. (2015). Cooking fuel preferences among Ghanaian Households: an empirical analysis. Energy Sustain. Dev. 27, 10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2015.04.003

Köhlin, G., Sills, E. O., Pattanayak, S. K., and Wilfong, C. (2011). Energy, gender and development. What are the linkages? Where is the evidence? World Bank Policy Res. Work. Paper 125, 1–63. doi: 10.1596/1813-9450-5800

Kopaei, H. R., Nooripoor, M., Karami, A., and Ertz, M. (2021). Modeling consumer home composting intentions for sustainable municipal organic waste management in iran. AIMS Environ. Sci. 8, 1–17. doi: 10.3934/environsci.2021001

Kropko, J. (2008). “Choosing between multinomial logit and multinomial probit models for analysis of unordered choice data,” in Working Paper, 1–46.

Kyaw, K. T. W., Ota, T., and Mizoue, N. (2020). Forest degradation impacts firewood consumption patterns: a case study in the buffer zone of Inlay Lake Biosphere Reserve, Myanmar. Global Ecol. Conser. 24, e01340. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01340

Kyayesimira, J., and Florence, M. (2021). Health concerns and use of biomass energy in households: voices of women from rural communities in Western Uganda. Energy Sustain. Soc. 11, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13705-021-00316-2

Leach, G. (1992). The energy transition. Energy Policy 20, 116–123. doi: 10.1016/0301-4215(92)90105-B

Lindsey, L. L. (2020). Gender: Sociological Perspectives, 7th Edn. Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315102023

Mahmood, H. (2020). Level of Education and Renewable Energy Consumption Nexus in Saudi Arabia. doi: 10.18510/hssr.2020.859

Mascherini, M., Bisello, M., and Rioboo Leston, I. (2016). The Gender Employment Gap: Challenges and Solutions. doi: 10.2806/75749

Matinga, M. N., Mohlakoana, N., de Groot, J., Knox, A., and Bressers, H. (2018). Energy use in informal food enterprises: a gender perspective. J. Energy South. Afr. 29, 1–9. doi: 10.17159/2413-3051/2018/v29i3a4357

Meikle, S, and Bannister, A. (2005). Focus on the significance of energy for poor urban livelihoods: Its contribution to poverty reduction. Development Planning Unit, University College London, London, United Kingdom. Available online at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/development/sites/bartlett/files/migrated-files/44_0.pdf

Mitra, S., Mishra, S. K., and Abhay, R. K. (2022). Out-of-school girls in India: a study of socioeconomic-spatial disparities. GeoJournal 7, 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10708-022-10579-7

Mothala, M., Thamae, R., and Mpholo, M. (2022). Determinants of household energy fuel choice in Lesotho. J. Energy South. Afr. 33, 24–34. doi: 10.17159/2413-3051/2022/v33i2a13190

Muller, C., and Yan, H. (2016). Household Fuel Use in Developing Countries: Review of Theory and Evidence Working Papers/Documents de travail Household Fuel Use in Developing Countries: Review of Theory and Evidence. 13, 51.

Muravyev, A., Talavera, O., and Schäfer, D. (2009). WITHDRAWN: Erratum to ‘Entrepreneurs' gender and financial constraints: Evidence from international data. J. Comparat. Econom. 37, 270–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jce.2009.08.005

Nguyen, C. P., and Su, T. D. (2021). Does energy poverty matter for gender inequality? Global evidence. Energy Sustain. Dev. 64, 35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2021.07.003

Njong, A. M., and Johannes, T. A. (2011). Analysis of domestic cooking energy choices in Cameroon. Euro. J. Soc. Sci. 20, 336–347.

Nyambane, A., Njenga, M., Oballa, P., Mugo, P., Ochieng, C., Johnson, O., and Iiyama, M. (2014). Sustainable Firewood Access and Utilization: Achieving Cross-Sectoral Integration in Kenya. World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and SEI Brief. Available online at: https://www.sei.org/publications/sustainable-firewood-access-and-utilization-achieving-cross-sectoral-integration-in-kenya/ (accessed January 25, 2023).

Oláh, L. S. (2001). “Gender and family stability,” in Demographic Research. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2001.4.2

Özcan, K. M., Gulay, E., and Ucdogruk, S. (2013). Economic and demographic determinants of household energy use in Turkey. Energy. 60, 550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2013.05.046

Pandey, V. L., and Chaubal, A. (2011). Comprehending household cooking energy choice in rural India. Biomass. Bioenerg. 35, 4724–4731.

Rahut, D. B., Ali, A., Abdul Mottaleb, K., and Prakash Aryal, J. (2020). Understanding households' choice of cooking fuels: evidence from urban households in Pakistan. Asian Dev. Rev. 37, 185–212. doi: 10.1162/adev_a_00146

Rahut, D. B., Ali, A., Mottaleb, K. A., and Aryal, J. P. (2019). Wealth, education and cooking-fuel choices among rural households in Pakistan. Energy Strat. Rev. 24, 236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.esr.2019.03.005

Rao, M. N., and Reddy, B. S. (2007). Variations in energy use by Indian households: An analysis of micro level data. Energy. 32, 143–153.

Riahi, K., van Vuuren, D. P., Kriegler, E., Edmonds, J., O'Neill, B. C., Fujimori, S., et al. (2017). The shared socioeconomic pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: an overview. Global Environ. Change 42, 153–168. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.05.009

Robinson, C., Lindley, S., and Bouzarovski, S. (2019). The spatially varying components of vulnerability to energy poverty. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 109, 1188–1207. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2018.1562872

Rothblum, E. D. (2017). “Division of workforce and domestic labor among same-sex couples,” in Gender and Time Use in a Global Context, eds R. Connelly and E. Kongar (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan).

Sehjpal, R., Ramji, A., Soni, A., and Kumar, A. (2014). Going beyond incomes: dimensions of cooking energy transitions in rural India. Energy 68, 470–477. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2014.01.071

Shari, B. E., Dioha, M. O., Abraham-Dukuma, M. C., Sobanke, V. O., and Emodi, N. V. (2022). Clean cooking energy transition in Nigeria: policy implications for developing countries. J. Policy Model. 44, 319–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jpolmod.2022.03.004

Shrestha, B., Bajracharya, S. B., Keitsch, M. M., and Tiwari, S. R. (2020). Gender differences in household energy decision-making and impacts in energy saving to achieve sustainability: a case of Kathmandu. Sustain. Dev. 28, 1049–1062. doi: 10.1002/sd.2055

Shrestha, B., Tiwari, S. R., Bajracharya, S. B., Keitsch, M. M., and Rijal, H. B. (2021). Review on the importance of gender perspective in household energy-saving behavior and energy transition for sustainability. Energies 14, 571. doi: 10.3390/en14227571

Steinbacher, R., and Holmes, H. B. (1987). “Sex choice: Survival and sisterhood,” in Man-Made Women: How New Reproductive Technologies Affect Women, eds G. Corea, R. Duelli Klein, J. Hanmer, H. B. Holmes, B. Hoskins, M. Kishwar, J. Raymond, R. Rowland, and R. Steinbacher (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press), 52–63.

Verena, D., Katharina Habersbrunner, A., and Ireland Agnes Mirembe, M. N. O. (2022). Women's Empowerment in the Manual with Concepts, Ideas, Projects and Accountability.

Wall, W. P., Khalid, B., Urbański, M., and Kot, M. (2021). Factors influencing consumer's adoption of renewable energy. Energies 14, 5420. doi: 10.3390/en14175420

World Bank. (2010). Gender and Environment. Washington, DC: World Bank.Available online at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/12490

World Health Organization. (2014). World Health Statistics 2014. World Health Organization.Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/112738

Appendix A

Keywords: gender, social construction, household headship, transition, fuel, role differentiation

Citation: Elasu J, Ntayi JM, Adaramola MS, Buyinza F, Ngoma M and Atukunda R (2023) Gender role differentiation in household fuel transition decision-making: Implications for education and training in Uganda. Front. Sustain. 4:1034589. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2023.1034589

Received: 01 September 2022; Accepted: 13 January 2023;

Published: 22 February 2023.

Edited by:

Myriam Ertz, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi, CanadaReviewed by:

Urvashi Tandon, Chitkara University, IndiaShouheng Sun, University of Science and Technology Beijing, China

Copyright © 2023 Elasu, Ntayi, Adaramola, Buyinza, Ngoma and Atukunda. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joseph Elasu,  ZWxhc3Uuam9zZXBoQG11YnMuYWMudWc=

ZWxhc3Uuam9zZXBoQG11YnMuYWMudWc=

Joseph Elasu

Joseph Elasu Joseph Mpeera Ntayi

Joseph Mpeera Ntayi Muyiwa S. Adaramola

Muyiwa S. Adaramola Faisal Buyinza

Faisal Buyinza Muhammad Ngoma4

Muhammad Ngoma4