- 1Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

- 2Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

- 3School of Commerce, Meiji University, Tokyo, Japan

The concept of business model has been around in scientific discussions for over half a century, but the adoption of business model for sustainability is much more recent. What constitutes a business model for sustainability is far from clear, and what drives the business model for sustainability to success needs further elaboration. The current paper adopts a conceptual approach to clarify the components of the business model for sustainability, focusing on the discussion of value addressed in its concept, and the interplay between the business model for sustainability and the internal performance management system. Furthermore, we connect our discussion to occupational health and safety because employee health and safety, one of the important elements of human capital, have been regarded as critical to the sustainable development of companies and society. We argue that OHS should be a fundamental cornerstone in doing business and should not be viewed as an afterthought of production and financial concerns. Therefore, OHS and employee relations should be addressed within the business model. The more important issue is the alignment of the value propositions, value creation, and value capture that underpin both the business model for sustainability and the internal performance management system. If the performance management system is decoupled from the business model, the long-term and short-term occupational health and safety advantages and the sustainable value propositions to stakeholders will not be realized.

Introduction

It appears that a consensus has evolved among many sustainability researchers and practitioners that sustainable development at the societal level is not likely achievable without the sustainable development of organizations. The growing complexity of business has led to additional stakeholders (e.g., suppliers, employees, business-to-business customers, NGOs, etc.) being involved in business activities. The business model is the arena where the value propositions that the organization wants to offer meet different stakeholders' demands. A comprehensive description of a sustainable business model is still lacking. To analyze business models from a sustainability perspective, there are two viewpoints. The first is the business case of sustainability which commonly restricts and considers sustainability performance only if it maximizes profits for only one group of stakeholders, i.e., financiers (in many company's shareholders) (Schaltegger and Burritt, 2018). This obviously implies a separation of economic performance and sustainability performance.

In contrast to the “business case of sustainability,” others propose a different approach by emphasizing a business case for sustainability by searching for solutions to social and or environmental problems, which then, in a second step, are further developed in a way also to create economic value (e.g., Perceva, 2003; Schaltegger et al., 2012; Schaltegger and Burritt, 2018). This approach can be described as a pragmatic process of gradually developing a set of different kinds of value captured or uncaptured in the cooperation and support of various stakeholder relations (e.g., employees, financiers, as well as environmental interest groups) in contributing to sustainable development. Additionally, using this perspective also concerns nonfinancial forms of economic value creation to measure environmental and social performance, including carbon emissions, toxic releases, spending on environmental protection, the number of environmental lawsuits, human rights, health, and so on (King and Lenox, 2001; Konar and Cohen, 2001; Busch and Hoffmann, 2011) besides the traditional shareholder value, and profit-oriented financial performance figures.

The business case for sustainability implies that the different stakeholders, if possible, should be treated equally. This means that very different kinds of values must be addressed and considered. A stakeholder perspective that is based on a view of an equal and trustful relationship also opens for long and sustainable cooperation between stakeholders and organizations (Beckmann et al., 2006). However, the business model literature requires more elaboration concerning the value proposition concept.

Employee health and safety, one of the critical elements of human capital, have been regarded as critical to the sustainable development of companies and society. As a sustainability objective, occupational health and safety are included in SDGs and evaluation criteria of ESG rating. Investments in OHS contribute value through reduced costs associated with the prevention of ill health, improved productivity, and a range of intangible benefits to an organization. This paper applies the discussion of the business model for sustainability to OHS. It discusses the value proposition of occupational health and safety beyond financial return on investment. The latter refers primarily to the interest of the employer and the owners of a company. However, from an employee perspective, other kinds of value, i.e., the persons own wellbeing, are the important issue. Therefore, problematizing the value concept is essential.

Another area that needs further discussion is performance management (PM) which provides information for companies to help in the short and long-term management, controlling, planning, and performance of the economic, environmental, and social activities undertaken by the corporation (Searcy, 2012). This paper also discusses how to design the PM to achieve sustainability objectives (value proposition to various stakeholders) like OHS and the missing link between the business model and the PM system. Some authors touch upon the latter's importance, but more research and clarity are needed. If the business model and the performance management system are decoupled, there is a risk that the business models' value proposals will not be achieved.

This paper is a “think piece” and its purpose is primarily to extend the discussion of the value concept as expressed in the business model for sustainability, but also to emphasize how to avoid de-coupling the value proposition in OHS and the internal general performance management system. When describing a business model for sustainability, very few authors include an internal performance management perspective. One exception is Schaltegger et al. (2016), who suggest that the role of the business model is to describe, analyze, manage and communicate the value of the firm to different stakeholders. However, Schaltegger et al. (2019) conclude that performance measurement and management have yet to be studied. To do so there is a need to open for a broad perspective on business models for sustainability. Since the role of the performance management system is to implement what the business model suggests the performance management system's connections to the business model for sustainability needs to be discussed.

The present paper is neither an empirical paper nor a result of a systematic literature review. Rather, it is a result of many decades of thinking of how to meet health propositions form employees and company's needs for financial performance. Already in the 1970's and 80's human resource accounting (Flamholtz et al., 1985) and the Swedish equivalent human resource costing and accounting (Johanson, 1999) was on the agenda (Flamholtz and Johanson, 2020). These efforts aimed to underline the importance of the workforce to the company. But neither of them really addressed the complexity of combining very different kinds of stakeholder values. Despite the suggestions to extend the borders of accounting nothing really happened (Johanson, 1999; Johanson and Henningsson, 2007). However, when the sustainability agenda was initiated the number of stakeholders grew and the problem to respond to the very different demands from all stakeholders became even more challenging. Aside from the extremely distinct and sometimes contradictory value needs, another lesson learned from human resource costing and accounting is that an accounting approach is very narrow minded when it comes to obtaining change.

Our present point of view is that the approach must be much broader, i.e., include business model as well as a performance management perspective. This is what the present article is about. It is based on three cornerstones: business model, value, and performance management. Subsequent sections will discuss the concept business models for sustainability, the sustainability agenda and value, sustainable value in the current business models, value as an existential matter, internal performance management, and finally a summary of our proposals. Our suggestions in this paper are of a general character with isolated examples from social sustainability, i.e., the field of OHS.

Business models for sustainability, an overview

There are various ways to describe what the business model is in practice. The practice shows the following trends (Black Sun Plc, 2014): Business description—discusses how the company is structured and how it delivers its products and services- which is the most popular approach among FTSE 100 companies; Integral to strategy- the two terms are exchangeable; How company earns profit—focused on financial returns; Value creation story- used to explain how the broader value, which is created, reflecting the growing trend for companies to communicate the broader role they play in society. The business model generally outlines the company's “what, why, and how.” However, defining a business model is difficult. Regardless of this, the literature discusses components of it and different perspectives to consider.

In Osterwalder and colleagues with the business model “ontology”, the business model concept components can be operationalized or structured with the following generic design elements (Osterwalder et al., 2005; Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010). Firstly, the value proposition is the value embedded in the product/service offered by a company to the various stakeholders. Secondly, the supply chain is also important in describing how the upstream relationships with suppliers can be structured and managed. Thirdly, the customer interface specifies how the downstream relationships with customers are to be structured and managed. Fourthly, the core business drivers of costs and benefits from the three other business model elements across business model stakeholders can be specified using a financial model or a calculator. This generates the business logic of a company which creates the foundation for the strategy and business case interrelationships. In this context, the business model influences business strategy and operative outcomes. This also implies that the business model is often interpreted as a determining factor of company behavior and, thus, business opportunities (Wirtz, 2011; Zott et al., 2011).

Over time, publications of business model research in the scientific discourse are assigned to the three basic perspectives of technology, organization, and strategy (Zott et al., 2011; Wirtz et al., 2016). The first perspective focuses on technology—the consequences of technologies on how firms organize to earn profits. The second, organizational, perspective deals with the business model as a strategic management tool to improve a company's value chain (e.g., Linder and Cantrell, 2000; Tikkanen et al., 2005). A third perspective, which is strategy- oriented, adds that creating and delivering sustainable stakeholder value is the centerpiece of any business model (e.g., Afuah, 2004; Chesbrough, 2010; Johnson, 2010; Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010; Zott and Amit, 2010). Moreover, while creating and delivering value, the business model itself can become a source of competitive advantage—by means of business model innovation (e.g., Mitchell and Coles, 2003; Chesbrough, 2010; Johnson, 2010).

The discourse on the sustainable business model is more recent than the business model, as academics and practitioners show growing interest in sustainability. While the early work on sustainable business models has dealt with strategies that contribute to corporate sustainability (Stubbs and Cocklin, 2008), much of it is about the value creation logic (Teece, 2010). The conventional interpretation of business models of sustainability strengthens the business paradigm of for-profit or profit maximization—i.e., financial value creation (Breuer and Lüdeke-Freund, 2014); attractive alternatives are still sought after. More recent studies have discussed business models as tools for addressing social needs, such as improving health care services in poor regions and promoting interactions in low-income markets (Sánchez and Ricart, 2010; Seelos, 2014). There has never been a greater need to make the business case for sustainability in occupational health for a variety of reasons, including but not limited to emerging patterns of non-standard and precarious work, remote telework, insufficient universal access by workers to quality occupational health services, and the prevalence and costs to business due to sickness absences and occupational illnesses.

The linchpin of new perspectives in the sustainable business model discourse has been, at best conceptual and theoretical. The longstanding debate has been about whether sustainability efforts have a positive or negative impact on the company's financial performance (Schaltegger and Hasenmüller, 2005). From a traditionalist perspective, this relationship is uniformly negative: sustainability-related voluntary efforts (e.g., pollution reduction) decrease the company's profit opportunity (e.g., Friedman, 1970; Xepapadeas and de Zeeuw, 1999). From a revisionist perspective, the relationship between environmental and economic performance has a bimodal distribution (Wagner, 2003). This implies that voluntary environmental activities increase the company's financial performance only until optimum (Wagner, 2001; Schaltegger and Synnestvedt, 2002), after which profitability starts to decline with every additional environmental activity. From an environmental economic point of view, the discussion of the profitability implications of the sustainability performance of the company contrasts, in its scope, with the argument that the economic system is part of or a subsystem of a larger global eco-system that sustains it (Daly and Farley, 2010). Therefore, the neoclassical economic perspective applied by many decision makers within organizations might be is limited in the context of a market perspective. When time is taken into consideration, the recent argument is that, in the short-term, the economic and social performance may conflict, while in the long-term, they may coincide. The empirical results, though not decisive about the causal relationship between the two, show statistical association between company social, environmental performance, and economic performance in the form of capital cost, profitability, and stock prices in the long run (Friede et al., 2015; Brooks and Oikonomou, 2018).

Although topics such as performance measurement and management have yet to be thoroughly studied, new perspectives have emerged in the sustainable business model discourse. Abdelkafi and Täuscher (2016) propose a systems perspective on value creation which connects a four-part model: the company, the environment, the decision-maker, and the customer. The part of the model about the company concerns the relationship between the company's value creation potential, the value proposition to the customers, the value to the natural environment, and the value to the company. The model recognizes the decision-maker as an active agent who triggers cognitive interpretation of the natural environment. Consequently, the agent's sustainability-related beliefs and norms and changes in these ideas change behavior that can result in changes in the company's business model that feeds back into the environment and to the customer.

Regardless of perspective, at the center of a sustainable business model is the challenge to internalize social and environmental factors (i.e., externalities) in the value proposition, value creation, and/or value capture to stakeholders and the internal performance management. It is easy to miss the importance of an extended discussion of the value concept and avoiding de-coupling of the internal performance management system and the business model for sustainability. These two concepts, value, and performance management system are essential for OHS.

The sustainability agenda and value

The sustainability agenda suggests that modifications are required within the worldwide economic systems, particularly the way organizations construct their business case. A new emphasis on qualitative rather than a quantitative change in economic growth seems desirable, with an associated de-coupling of economic growth and the consumption of non-renewable resources. There is, however, considerable debate over the extent of change required. This debate primarily centers on the concept of value—the problem of measuring and estimating the value of resources. Value is, after all, a relative term with differential meanings.

From the economist's viewpoint, value is represented by the utility of a resource, particularly if it has economic or monetary conversion potential. There are values such as market value, value to humanity, and overall value to the ecosystem according to the “environmental economists” and the “ecological economists” (Köhn, 1999). One viewpoint considers the natural environment as simply a source of inputs to be allocated for economic development. The second viewpoint is that the economy is the sub-structure of a larger human civilization, its institutions, and the larger biophysical world. The former contributes to unsustainable resource use the continued consumption of materials based on the economic fundamental of expansion (Schütz, 1999). The latter view states that if these resources are deemed irreplaceable and essential requirements for human existence, then the economist's concept of value must be broadened beyond one that holds that biodiversity is a substitutable market good like any other—it must include both market prices and those unquantifiable human cultural and environmental features (Köhn, 1999).

On an aggregated level, this is about the survival of the market economy or growth model, which views the natural environment as input under attack. This market growth model has been suggested not one of the most harmonious in terms of continued consumption of materials and ignoring agreements between the relevant parties, even if it is often approved on legislation. In a global market, there is hardly any space for collective agreement between relevant parties. There is little opening where the stakeholders and organizations can co- operate toward sustainable business cases. As such, the message it sends to new organizations has often been characterized by “If you cannot beat them, join them”. However, with the increasing scarcity and overuse of natural resources, the environmental aspects of business activities are increasingly becoming more important topics of discussion.

In recent years, various ideas and proposals have emerged that aim to rewrite the market economy's social contract. What they have in common is the idea that businesses need more varied measures of successful sustainability and value than simply profit and growth. In sustainability, there is the idea of “doughnut economics”, a theory proposed by economist and author Raworth (2012), which suggests that it is possible to thrive economically as a society while also staying within social and planetary boundaries. Some authors argue sustainable development to require systems thinking that uses network analysis to integrate multiple factors (economic, social, and environmental) and to understand and manage the whole picture by focusing on the relationships between the different entities of a system, rather than on isolated parts.

Value in the current business models

In Upward and Jones (2015)'s propositions, an organization can be labeled sustainable if it sustains human and other life forms throughout its value network that creates positive environmental, social, and economic value. Such an organization would not only do no harm, but it would also create social value while regenerating the environment to be financially viable (Schaltegger et al., 2012).

Value is primarily the benefits derived by stakeholders from tangible and intangible exchanges in a stakeholder network (Yang et al., 2014). Currently, the definition of value is the scope whereby not only economic transactions are considered but also relationships, exchanges and interactions conceptualized as value flows that take place among stakeholders in a network (Den Ouden, 2012). This definition adopts the notion of sustainable value that “incorporates economic, social, and environmental benefits” conceptualized as different value forms (Evans et al., 2017, p. 601). Firstly, economic value forms could include cost savings, profit, return on investment and long-term viability. Secondly, social value forms are the benefits created for various members/groups in society and could include job creation, secure livelihoods, health, wellbeing, and community development. Thirdly, environmental value forms tend to focus on reducing the negative impacts, e.g., resource efficiency and pollution prevention of air, water, and soil, as well as creating positive impacts for the environment, e.g., investing in renewable resources.

Several authors have provided useful general business model frameworks, including several blocks of perspectives of value as components of the business model: customer value (Afuah and Tucci, 2001), value cluster (Rayport and Jaworski, 2001), value network (Hamel, 2000), value chain in the value network (Chesbrough and Rosenbloom, 2000), value proposition, value creation and delivery system, value capture and uncaptured (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010; Yang et al., 2017) as one of the main components of a business model. Multiple forms of new value in the sustainable business model have also featured in the literature, for instance, value captured, value missed, value destroyed, and new value opportunities (Bocken et al., 2013) and value uncaptured (Yang et al., 2017).

Among all these concepts, value proposition, value creation and delivery system, and value capture contained in the business model framework suggested by are more prevalent which can also be extended with modifications to the sustainable business model (Geissdoerfer et al., 2018).

Value proposition

The value proposition building block describes the bundle of products and services that is to be provided and to whom (for e.g., customers or a specific group). Most research on value propositions to date has focused on the narrow customer-firm perspective (Frow et al., 2014; DaSilva, 2018). The value proposition is the reason why customers turn to one company over another. Each value proposition consists of a selected bundle of products, and/or services that caters to the requirements of customers. It may be quantitative (e.g., price, speed of service) or qualitative (e.g., design, customer experience), which is expected to solve a customer problem or satisfy a customer need. In this sense, the value proposition is an aggregation, or bundle, of benefits that a company offers customers. Some value propositions may be innovative and represent a new or disruptive offer. Other proposals may be like offers already existing on the market but with added features and attributes. Recent developments in the sustainable business model innovation space have led to the extension of the value proposition concept to sustainable value propositions generating shared value for a network of stakeholders while addressing a sustainability problem (Baldassarre et al., 2017). A sustainable value proposition makes a proposal of value in terms of the economic, environmental, and social benefits that a company's offering delivers to customers and society at large, considering both short-term profits and long-term sustainability (Patala et al., 2016, p. 144).

Value creation

Value propositions integrate resources and align value creation mechanisms in a reciprocal manner, i.e., actors are operating and seeking an equitable exchange of value (Kowalkowski et al., 2016). The organization with all the functions and activities is involved in this step. Argandoña (2011) argues that if the value created is of multiple forms, better ways of creating economic and non-economic value in a sustained way should be found, so that all stakeholders who help to create the benefits also become beneficiaries of value.

Value captured

The value captured is the benefit delivered to the company and its stakeholders; it includes not only monetary value, but also the wider value provided to the environment and society. It “describes how part of the value generated for a stakeholder can be transformed into value useful for the company” (Geissdoerfer et al., 2018, p. 404). According to Yang et al. (2017), if companies can recognize the value to be captured and identify the opportunities represented by value uncaptured, it might lead to an effective approach to sustainability-focused business model innovation.

In contrast, the concept of value uncaptured proposes that identifying hidden value in the current business model can trigger business model innovation for sustainability. Value uncaptured is defined as the potential value which could be captured but has not been captured yet. To better understand the concept of value uncaptured, Yang et al. (2017) work develops four forms of value uncaptured such as value surplus, value absence, value missed, and value destroyed in business models, which can be transformed into value opportunities.

Not all value uncaptured is guaranteed to be turned into value opportunities, and not all value opportunities can be implemented and turned into value. However, the identification of value uncaptured is intended to trigger the discovery of new value opportunities, which leads to innovation of the business model. This is the main novelty of this framework: using negative forms of value to stimulate the identification of negative aspects of the current business model and directly inspire the identification of value opportunities.

The value proposition in occupational health and safety

The basic topics through which social sustainability is understood, such as working conditions and fair salaries, are important to OHS in the sustainability agenda (see e.g., Murphy, 2017). One of the areas where creating social value can be impactful and is also possible to achieve is through the improvement in the working conditions of those in employment. This implies that work should not cause harm to employees or that no one should go home after work in a different worse health state than before the workday started. The workplace is identified as a priority setting to facilitate social cohesion, inclusion, and interaction among employees and employers. A lot of working people spend a significant amount of time with their work, and existing social networks for social support could be used to change behaviors to improve health and wellbeing. Aspects of social sustainability, which contain components of support, regulations, and/or environmental improvements to encourage healthy behavior, can be used to enhance workers' health and wellbeing.

In one sense, both the employer and employee have a responsibility, but the employer's is a higher order. Since employee health contributes to the profitability, productivity, and safety outcomes of organizations, there is, in principle, a strong business case to integrate OHS into the business model, especially in terms of value proposition to the employee. However, many organizations require persuading through business cases, i.e., showing a financial value to secure approval for investment in an intervention or service. It has been suggested that there is a gap in the communication of cost-benefit evaluation and employers even in the case where a clear cost-beneficial outcome is attained. Previous studies show that employers' reasons for providing access to occupational health services are primarily due to legal and financial reasons or incentives (Miller and Haslam, 2009; Martinsson, 2017). Other reasons include moral duty of care to employees, assisting recruitment and retention, employee expectations, maximizing productivity, and improving employee health and wellbeing. It is obvious that the value proposition to the employee has lost the number one spot where it belongs.

There appears to be growing awareness of the need to justify and demonstrate the value of OHS in financial terms. Although several studies have successfully done so by showing positive financial returns to the employer (Grimani et al., 2018), this estimation is not always straightforward. Attributing exact costs and benefits to occupational health services can be quite difficult, not least because the costs are immediate while benefits usually accrue over time. Also, some of the benefits, e.g., increased employee motivation or improved company image, may be difficult to quantify in monetary terms (Steel et al., 2018). As a result, not only should the business case include major cost drivers, but perhaps all the downstream benefits of the investment should also be considered. This takes the evaluation of value to the employer from the comparative due to the lack of data to the intuitive level. Intuitive evaluation of value can be equally as good as a comparison of value in terms of employee health since data might not always be available. A drastic turnaround in occupational health research would be needed for us to have a bright future ahead with better tailoring and delivery of tools to the needs of the target employee groups, including those workers with low socioeconomic positions.

Value as an existential matter

The value concept has already been addressed several times, but a deeper discussion is needed because of its many denotations. Basically, it is closely related to ethical principles. It could be based on duty, consequence, or virtue ethics. In business models it is common that the value demands, and proposition are expressed from a consequence, utilitarian perspective. However, this is not always the case, e.g., concerning human rights or human resource policies in firms. Regardless of the underlying ethical principles, the value concepts are formulated from subjective anticipations. However, the anticipations are often not explicit. If the value propositions and demands related to sustainability should be meaningful, there is a need to understand and communicate the underlying ethical principles.

In business, utilitarian-based values have their roots in traditional exchange of goods (Cameron and Neal, 2003). These value concepts dominate over other value concepts based on duty or virtue ethics. The utilitarian concepts are often taken for granted. In addition, they have a hegemonic position and a performative power which means that the profit (or loss) overrules almost all other values regardless of stakeholder considerations. There are many reasons for the hegemonic dominance. One such reason is that the shareholder value has for many decades been the most important objective for firms to reach (Friedman, 1970).

The taken-for-granted and narrow-minded view concerning utilitarian business values is now starting to change in favor of a multidimensional view on why firms exist. In accordance with the increasing need for considering sustainability, the number of stakeholders and their value demands have also increased. Regarding OHS, the most important stakeholders are employees and unions, employers and employer associations, citizens (employee families), and local authorities. Their value demands may vary significantly, and the multidimensional variation is quite natural because different stakeholders have different responsibilities to their groups. However, the different stakeholder values have one thing in common, i.e., that duty and virtue ethical principles are underrepresented.

Stakeholder values are not stable over time. This is obvious when looking back on what some economists have suggested during the last 200 years. To start with, Quesnay, who originally served as a doctor to Louis XV in France, held that value and value creation in society is not about money creation but rather concerned the farmers' ability to produce food for people. The farmers and the consumers were the important stakeholders, whereas the merchant was just a parasite (Guillet de Monthoux, 1983). This meant that the value proposition to the farmer was to take care of the nature. Even Adam Smith joined this virtue ethical principle, at least sometimes, even if he suggested that nature could sometimes be expropriated. The close relationship between nature and economics could be found among several economists at the time, e.g., the Swedish economist Anders Berch.

Later, several scholars opposed Quesnay's view. However, Adam Smith also addressed the value of goods. He held that the value was the sum of the costs to produce the goods. Jean- Baptiste Say disagreed with Smith when he emphasized that the value is dependent on the subjective benefit of the goods, i.e., a utilitarian perspective. Say as a representative for the so-called harmony economists added that if economic forces were released, equilibrium should be reached between classes and different interests (Schumpeter, 1954).

The subjective benefit is also referred to by many other economists. In terms of exchange value, Davanzati suggested in, 1588 that water and diamonds, for example, have different values depending on the setting in which the transaction takes place (Schumpeter, 1954). The value of water could be extremely high when water shortage and drought are at hand, whereas diamonds can be worthless. This underlines that utilitarian value concepts often depend on the context.

Even concerning profit, there is a concept of hegemony. Concepts like bottom line, return on equity, and different forms of profit such as profit before taxes, gross profit, operating profit, and net profit are monetary and defined from a shareholder value point of view. They describe the reward to business owners for investing, and at the same time, they are catalysts for the capital economy. However, from an employee standpoint, a more relevant concept would be value-added. For the employee stakeholder category, the thinking behind and definition of value added is most relevant. Value added is normally defined as sales revenues minus raw material and other externally bought goods or services. The value-added shows what is left to distribute between shareholders and employees. The difference compared to other profit concepts is that the latter concepts also include a deduction of employee costs, e.g., salaries, pension costs, and health care.

From a moral perspective there are several problems with many of the monetary-based concepts, e.g., exchange value, production value and market value. Emmanuel Kant raised one of these problems when he stated that something that has been given a monetary-based value could easily be exchanged with something else (Kemp and Hedenblad, 1991; Kant, 1996). In the 30 Years War price lists comprising agreed prisoner values existed. The agreed market price for an imprisoned field marshal was 20,000 taler, whereas a private soldier could be bought for eight taler (Frey and Buhofer, 1986).

The reason for discussing the concept of value is to focus on the necessity to deeply understand and communicate the value concept related to business models for social sustainability. Stakeholders differ between advocating values based on the consequence, duty, or virtue principles. To make it even more complicated, the same stakeholder may sometimes express value demands comprising both consequence and duty-based principles. Concerning the employee stakeholder category, the value demand could include both a decent salary (consequence ethics) and safety guarantees (duty ethics).

Ecologic, social, and economic sustainability are difficult to separate. Rather they are integrated or even embedded (Marcus et al., 2010). Stakeholder value demands and propositions are of existential characters (Hägglund, 2019). Regarding OHS, the situation at the workplace can be separated from neither why the firm exists nor the individuals' existential demands. If not embedded, the firm and the employee are interdependent. A safe and healthy firm has a better chance to offer safe and healthy working conditions and vice versa. However, the value proposition to the employees that are expressed in the business model for social sustainability must be transformed into practice.

As we have already stated, basically, value is an existential matter dependent on what we human beings want to achieve in life. What is necessary and important for human beings to feel free and satisfied (Hägglund, 2019)? To survive, it is necessary to secure basic needs of food, drink, and accommodation. Suppose the fetching of fresh water at a distant place is a necessary activity. In that case, the experience of the beautiful nature when fetching the water is rather a matter of satisfaction and freedom. Work is, for most people, necessary because one needs earnings to survive. For others, work is about satisfaction. The important issue at stake is whether the human feels free to choose an activity or is forced to accomplish the activity. The border between freedom and necessity is not sharp, and sometimes, the idea of value is mixed with the question of what is valuable. For example, recovering from the necessary working time might not be valuable as such and can thereby not be regarded as free time. Regarding OHS, there are numerous actions that seek to avoid harm to employees, including but not limited to preventing accidents or hazardous diseases, delivering a fair wage, guaranteeing better work conditions, and enabling a respectful collaboration between the employer and the employees. Respectful cooperation normally gains from interactive cooperation about positive changes, especially, in the psychosocial work environment, which in turn have positive effects on the employer and the employees in terms of productivity gain, reduced absences, improved health, work ability, etc. (e.g., Karasek and Theorell, 1990).

The concept of value becomes even more complex because our present society is built on an inherent basic neo-classical assumption that growth is important (Brown et al., 2017). To achieve growth, people and nature are looked upon as exploitable resources, and to improve productivity, it is important that the workforce is healthy. Health care, food, housing, restrictions concerning working hours, holidays, etc. are necessary elements to increase neo classical based value from the employees. The latter was recognized by Adam Smith as well as Karl Marx. Hägglund holds that the growth imperative is a systemic embedded necessity and therefore, nature as well as people become commodified. However, technical innovation can mitigate the harm caused by commodification and the growth imperative (Hägglund, 2019).

We hold that for OHS and other sustainability matters, a very urgent issue is to start debating and increasing awareness about what is value and what is valuable. This is a concern not only for the employees and the managers but for most of the firms' stakeholders, e.g., shareholders, unions, the civil society, and the customers. The scientific and broader literature demonstrates that investments in occupational health bring value through reduced costs associated with the prevention of ill health, increased productivity, and a variety of intangible benefits (Nicholson, 2022) and vice versa. Employers may be motivated by three key factors (legal, moral/ethical, and financial reasons) to care for their employees and are socially responsible by providing them with access to occupational health services (Nicholson, 2022). This can assist in safeguarding and improve a company's reputation with customers, workers, investors, regulators, and shareholders.

To achieve sustainability, the value proposition, value creation and delivery, and value capture and uncaptured by OHS should also be discussed within the companies. The monetary and non-monetary value provided to employees, health assurance association and society, the increased or decreased value creation capability by health improvement or impairment, the value captured by the company in terms of reputation, business performance and stock price or uncaptured because of lack of vitality. There are not many, but some of the companies in Japan have been telling their value creation story (the implicit sustainable business model) with OHS included (Yao and Johanson, 2022).

More insightful and knowledgeable discussions of growth imperatives will hopefully result in better informed definitions of the normative concept of value based on value propositions and value demands from all the different stakeholders with interests in a specific firm. The business model for sustainability is the right place, the agora, where the discussions can be coordinated. However, value propositions and value demand also need to be transformed into practice in relation to external as well as internal stakeholders. The transformation tool within the firm is the performance management system.

Performance management

As mentioned earlier, very few authors include an internal performance management perspective when business models for sustainability are discussed. A couple of exceptions are Schaltegger et al. (2016), and Schaltegger et al. (2019). In the latter article the authors suggest that performance measurement and management have yet to be studied. Despite Schaltegger et al. (2019) suggestions, we hold that the literature addressing business models is too vague concerning the interrelationship between the business model and the internal performance management.

Performance measurement per se is a well-researched area. There are many definitions of performance management. For example, it is defined as a set of performance measures that provide a company with helpful information that helps manage, control, plan and perform the activities undertaken by the company (Tangen, 2005). The definition of performance in the literature demonstrates that it is always linked to objectives or goals and the results of activities or operations. When sustainability is embraced in the business, the objective and actions of the business differentiate from the conventional one, with the definition of performance changing accordingly to go beyond the economic value. It has been argued that companies need to integrate sustainability into their business using their performance management systems (sustainable performance measurement) to maximize the economic, environmental, and social benefits (Searcy, 2012; Sroufe, 2017; Wijethilake and Upadhaya, 2020). This implicitly connects the business model for sustainability and performance management. Once designed with a value proposition, a business model must be implemented. Performance management is the tool that helps to implement a business model by setting performance objectives, observing performance, integrating performance information, performance evaluation, giving feedback, performance review meetings, and performance coaching (Schleicher et al., 2018). The business model needs to be coherent with the internal management process and structure to achieve the value propositions to the different stakeholders. If the latter is decoupled from the business model (Meyer and Rowan, 1977), the value propositions, the value created, and the value captured is less likely to be realized.

To achieve OHS, establishing a performance management system and integrating it into the business model is also indispensable. PM has been extensively discussed in human capital management. Adopting a sustainable HR approach to PM incorporates a balance of financial results with positive human and social outcomes, both of which are critical to sustaining superior long-term business performance (Maley, 2014). However, though employee health and wellbeing are considered a part of human capital (Islam and Amin, 2022) compared with other HCM topics, OHS was less discussed and seldom investigated in the PM. The following are some points concerning designing an OHS PM.

Emanating from decades of critics of the limited scopes of accounting and management control, several researchers have suggested frameworks for more extensive performance management systems (e.g., Malmi and Brown, 2008; Ferreira and Otley, 2009). To analyze the design and the use of such a performance management system, Ferreira and Otley (2009) suggested a broad framework comprising a dozen of issues that must be considered. However, very soon after that, Broadbent and Laughlin (2009) proposed that Ferreira and Otley's framework could be further elaborated to separate a relational and a transactional performance management system. The former is based on practical and communicative rationality, where consensus between different actors is essential. The foundation of the transactional view is more abstract and instrumental. Already Hofstede (1978) complained that management control systems and accounting suffer from an instrumental approach because of philosophical poverty where basic values and visions could be forgotten.

Broadbent and Laughlin (2009) also suggested a division between the performance management system's functional and contextual processes. For example, strategies, goals, key performance measurements, and evaluations are functional, whereas organization structure, rewards and coherence are contextual. The role of the contextual processes is to support the functional processes. The very importance of and division between functional and contextual performance management system elements was also obvious in a study of Swedish listed companies by Johanson et al. (2001a). They studied and identified different functional and contextual processes that facilitate learning and the transformation of attention and knowledge into action.

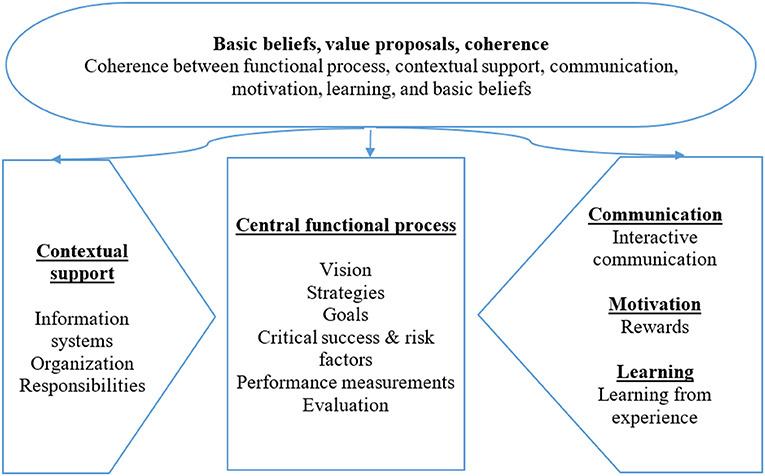

Johanson and Aboagye (2020a,b) have further developed Ferreira and Otley's performance management framework (see Figure 1). They hold that most companies follow standard operating procedure concerning the internal management. They call this the central functional process (Broadbent and Laughlin, 2009). The latter comprises visions, strategies, goals, targets, critical risk and success factors, performance measurements and finally evaluations. These functional factors include financial and non-financial data. The functional process is supported by contextual support processes (Broadbent and Laughlin, 2009). The contextual processes (or structures) comprise organization and information systems (Ferreira and Otley, 2009) but also responsibilities (Johanson et al., 2019). The latter could be of different kinds, formal or informal. Sometimes responsibilities are clarified in a contract between a manager and a subordinate. Even these can be of a formal character or just informal (Johanson et al., 2019).

Figure 1. A performance management framework (Johanson et al., 2019).

Further, a well-functioning performance management system is normally based on interactive communication between the people or stakeholders involved (Simons, 1995; Ferreira and Otley, 2009). To avoid rigidity and inflexible structures within all kinds of management systems, it is important to encourage free and open discussions based on respect and cooperation (Noland and Phillips, 2010). The ultimate desire is to obtain a mutual understanding (Fryer, 2015) of the design of the performance management system and how it works with respect to the achievement of the business model and the stakeholder value propositions. The interactivity is also a precondition not just for an employee involvement but also for a continuous learning process (Ferreira and Otley, 2009) that facilitates a continuous adaptation of the complete performance management system. Because variations in the society that are more complex than the internal performance management system create tensions that firms must cope with and adapt to in order to survive (Boisot and McKelvey, 2010), the treatment of the tensions demands a balance between stability and flexibility.

The openness for discussions and change is also a matter of changing the view on management as agents in favor of a stewardship view (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). An agent view based on command, control and passivity are not appropriate when creativity, adaption, and innovations are necessary for future survival of the organization. Instead, a stewardship view facilitates cooperation, interventions, and sustainable relations with all stakeholders like management, shareholders, customers, and employees (Donaldson, 2008).

Rewards (Johanson et al., 2001b; Ferreira and Otley, 2009) are another important condition for an efficient performance management system. The rewards could be extrinsic or intrinsic (Flamholtz et al., 1985), i.e., it is not just about salary and bonus items, but also about, for example, feedback from other stakeholders like top management demand and by means of benchmarking (Johanson et al., 2001b).

All organizations and all management systems are based on basic beliefs (Johanson et al., 2019) of how to achieve or disregard the value propositions. Sometimes these beliefs and values are explicit, but sometimes they are not. Nevertheless, they are extremely important because all other management processes are designed and put into practice with the basic beliefs as a point of departure. In the present text, basic beliefs refer to what is seriously expressed with respect to what should be obtained by the organization, i.e., the value propositions. The basic beliefs are often explicitly or implicitly expressed in the business model, which concerns how the firm is supposed to work. If the basic beliefs and performance management system are decoupled (Meyer and Rowan, 1977) an instrumental approach to the performance management system is reinforced.

Finally, the performance management system needs to be coherent. Ferreira and Otley (2009) claim that, “Although the individual components of the performance management systems may be apparently well designed, evidence suggests that when they do not fit well together (either in design or use), failures can occur” (Ferreira and Otley, 2009, p. 275). This means that it is important that not just functional, but all other processes are coherent with each other and with the business model and its value propositions. In case coherence does not exist, there is even at this point a risk that the de-coupling will cause serious harm to the desire to achieve stakeholder value as expressed by the business model for social sustainability.

The suggested performance management framework is constructed from a relational as opposed to a transactional point of view (Broadbent and Laughlin, 2009) to admittance to a view that patterns and structures, independently of individual actors, influence the possibilities of action (Cuff et al., 1998). Giddens (1984) proposes that (individual) action and organizational structures are related, whereby (individual) action generates organizational structures and vice versa. Equally important is that structures not only constrain but also enable action. The structuration theory is about the interplay of an agent's actions, and social structures in the production, reproduction, and regulation of any social order. According to Giddens (1984), structures are involved in all types of social interaction, and they are the foundation as well as the outcome of actions. Wicks (1998) persuasively argues that structures provide the foundation for both stability and change. The structure is mediated through norms and moral codes, which sanction behaviors. It comprises the shared sets of values and ideas about what things are important vs. what things are of a more trivial nature. Applying this perspective, we mean that the structures have the simultaneous ability to provide control of organizational activities and yet be shaped by them, i.e., the duality nature of structures.

The framework does not represent an ideal classification system. It is not exhaustive in the way that all possible factors are included. Neither are the categories exclusive (Gröjer, 2001). It is difficult or even impossible to sharply distinguish between the different categories. The framework is meant to be useful when the business model and its interrelation with the performance management systems are developed or analyzed. However, the framework should not be applied in line with what Lapsley (2009) labels “a tick the box mentality”, because it is not a prescription of what is needed to address when designing a coherent performance management system. Hopefully, it is a framework that has the potential to achieve “a rich understanding” of the performance management systems (Ferreira and Otley, 2009). To borrow from a famous saying, “essentially this framework may be wrong, but it can be useful.”

To understand the usefulness of the framework, some earlier case studies have been performed, e.g., in a couple of local municipalities (Johanson et al., 2019) and to understand the functionality of OHS management (Frick and Johanson, 2013). With respect to the latter the analyses revealed that in one of the investigated organizations an OHS vision existed, but this vision was not supported by other OHS management processes. Critical success and risk factors were vaguely described. Strategies and goals existed, but these were not coherent with performance measurements. The latter means that follow-ups were difficult to perform. The formal treatment of the OHS was good and in accordance with the provision but still the achievement of the OHS basic view, i.e., a good working environment, was not convincing. Budget issues, i.e., a conventional management control process, seemed to be more important than achieving a good working environment. The latter was probably also due to insufficient or vague responsibility and contract processes as well as rewarding processes that prohibit necessary work environment investments when these investments even slightly exceeded the budget.

Most recently, Yao and Johanson (2022) have used the framework to analyze Japanese companies' OHS management. The best practices incorporate health and productivity management (H&PM) into the company code or norm, clarifying the value proposition to employees and society. They also establish a solid organizational structure, define responsibility to support the central function, communicate with employees, collaborate with healthcare professionals and health insurance associations, and use the Plan, Do, Check, Act (PDCA) cycle for improvement to ensure value proposition can be realized. They also testify to the effectiveness of H&PM, such as turnover, presenteeism or absenteeism, engagement, and other performance to make sure value is captured. Though the business model for sustainability is still implicit in most companies, establishing a coherent version and integrating it with the business model contributes to a highly evaluated H&PM.

Conclusion

In this article, we have discussed a couple of major shortcomings in the literature about business models for social sustainability. The shortcomings refer primarily to the concept of the value and the missing coherence between the suggested business models, including its value propositions, value creation, and value capture in relation to different stakeholders and the performance management system. Regarding the value concept, almost all of what is written discuss or anticipate financial values regardless of suggestions that even other stakeholders than shareholders and company management must be considered when values are discussed and developed. This is to say that for some of the stakeholders' duty or virtue values could be as important as or even more important than utilitarian-based values. For example, employees could value addressing equality, or the right to express one's views about health or safety at the workplace could be crucial issues.

Concerning the lack of coherence between a proposed business model and the performance management system, there is also an issue since there is a high possibility that the de-coupling would result in a situation in which the business model's value proposition to important stakeholders is not met. The most important issue at stake is that the performance management system is designed in a way that the value delivery could be achieved. For analytical reasons, we have suggested a conceptual framework that hopefully can be used. The framework comprises a functional process (e.g., strategies, goals, key indicators, etc.) and even more important contextual factors that may reduce the risk of de-coupling. These factors are interactive communication, motivation, and learning but also information systems, organization, and responsibilities.

Schoenmaker and Shramade (2020) argue that there are strong forces to maintain the status quo for many companies to preserve the current value of their assets. However, companies can incorporate externalities by connecting social and environmental dimensions to the sustainability-oriented business model. However, they may also risk decoupling the performance management system from the sustainable-oriented business model if a congruent change in basic beliefs and values is not sufficiently dealt with. As we have discussed, such change is of great importance because all other management processes are designed and put into practice with the basic beliefs as a point of departure. Challenges that could emerge if decoupling between the sustainability-oriented business model and the internal performance management include (1) A reinforcement of an instrumental approach to the performance management system as well as the business model; (2) A de-coupling between espoused theory and practical action that could cause serious harm to the desire to achieve stakeholder value as expressed by the business model for sustainability.

As we suggested in the introduction this paper is a “think piece” and its purpose is primarily to extend the discussion of the value concept as expressed in the business model for sustainability, but also to emphasize how to avoid de-coupling the value proposition in OHS and the internal general performance management system. The perspective is broad and calls for further development and deeper discussions. We hope that the article will trigger many future comments and discussions with the aim of facilitating improvements of business models for sustainability especially focusing occupational health and safety.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

This manuscript originally written by UJ. Later reviewed and changed by EA and JY.

Funding

This study was supported by Karolinska Institutet (400 USD).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdelkafi, N., and Täuscher, K. (2016). Business models for sustainability from a system dynamics perspective. Organ. Environ. 29, 74–96. doi: 10.1177/1086026615592930

Argandoña, A. (2011). “Stakeholder theory and value creation,” in IESE Business School Working Paper No. 992 (Pamplona: University of Navarra).

Baldassarre, B., Calabretta, G., Bocken, N. M. P., and Jaskiewicz, T. (2017). Bridging sustainable business model innovation and user-driven innovation: a process for sustainable value proposition design. J. Clean. Prod. 147, 175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.081

Beckmann, S. C., Morsing, M., and Reisch, L. A. (2006). “Strategic CSR communication: An emerging field,” in Strategic CSR Communication, eds M. Morsing, and S. C. Beckmann (Stockholm: DJØF).

Black Sun Plc. (2014). Business Model Disclosure: The Missing Link. London: Black Sun Plc.Available online at: https://www.blacksunplc.com/en/our-thinking/insights/blogs/business-model-disclosure-the-missing-link.html (accessed June 19, 2022).

Bocken, N. M. P., Short, S. W., Rana, P., and Evans, S. (2013). A value mapping tool for sustainable business modelling. Corp. Gov. 13, 482–497. doi: 10.1108/CG-06-2013-0078

Boisot, M., and McKelvey, B. (2010). Integrating modernist and postmodernist perspectives on organizations: a complexity science bridge. Acad. Manage. Rev. 35, 415–433. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2010.51142028

Breuer, H., and Lüdeke-Freund, F. (2014). “Normative innovation for sustainable business models in value networks,” in Paper Read at the Proceedings of XXV ISPIM Conference: Innovation for Sustainable Economy and Society, at Dublin, Ireland.

Broadbent, J., and Laughlin, R. (2009). Performance management systems: a conceptual model. Manage. Account. Res. 20, 283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.mar.2009.07.004

Brooks, C., and Oikonomou, I. (2018). The effects of environmental, social and governance disclosures and performance on firm value: a review of the literature in accounting and finance. Br. Account. Rev. 50, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bar.2017.11.005

Brown, J., Söderbaum, P., and Malgorzata, D. (2017). Positional Analysis for Sustainable Development. Reconsidering Policy, Economics and Accounting. London: Routledge.

Busch, T., and Hoffmann, V. H. (2011). How hot is your bottom line? Linking carbon and financial performance. Bus. Soc. 50, 233–265. doi: 10.1177/0007650311398780

Cameron, R., and Neal, L. (2003). A Concise Economic History of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chesbrough, H. (2010). Business model innovation: opportunities and barriers. Long Range Plann. 43, 354–363. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.010

Chesbrough, H., and Rosenbloom, R. S. (2000). The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: evidence from Xerox Corporation's technology spinoffs. Industrial Corp. Change 11, 529–555. doi: 10.1093/icc/11.3.529

Cuff, E. C., Sharrock, W. W., and Francis, D. W. (1998). Perspectives in Sociology. New York, NY: Routledge.

Daly, H., and Farley, J. (2010). Ecological Economics: Principles and Applications. Washington, DC: Island Press.

DaSilva, C. M. (2018). Understanding business model innovation from a practitioner perspective. J. Bus. Models 6, 19–24. doi: 10.5278/ojs.jbm.v6i2.2456

Den Ouden, E. (2012). Innovation Design: Creating Value for People, Organizations and Society. London, UK: Springer.

Donaldson, L. (2008). Ethics problems and problems with ethics: toward a promanagement theory. J. Bus. Ethics 78, 299–311. doi: 10.1007/s10551-006-9336-6

Evans, S., Fernando, L., and Yang, M. (2017). “Sustainable value creation—from concept towards implementation,” in Sustainable Manufacturing. Part of the series Sustainable Production, Life Cycle Engineering and Management, eds R. Stark, G. Seliger, and J. Bonvoisin (Cham: Springer).

Ferreira, A., and Otley, D. (2009). The design and use of performance management systems: an extended framework for analysis. Manage. Account. Res. 20, 263–282. doi: 10.1016/j.mar.2009.07.003

Flamholtz, E., and Johanson, U. (2020). Reflections on the progress in accounting for people and some observations on the prospects for a more successful future. Account. Audit. Account. J. 33, 1791–1813. doi: 10.1108/AAAJ-02-2019-3904

Flamholtz, E. G., Das, T. K., and Tsui, A. S. (1985). Toward an integrative framework of organizational control. Account. Org. Soc. 10, 35–50. doi: 10.1016/0361-3682(85)90030-3

Frey, B., and Buhofer, H. (1986). A market for men, or: there is no such thing as a free lynch. J. Inst. Theor. Econ. 142, 739–744.

Frick, K., and Johanson, U. (2013). Systematiskt arbetsmiljöarbete: - syfte och inriktning, hiner och möjligheter i verksamhetsstyrningen: En analys av svenska fallstudier. Stockholm: Arbetsmiljöverket, Rapport 2013, 2011.

Friede, G., Busch, T., and Bassen, A. (2015). ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 5, 210–233. doi: 10.1080/20430795.2015.1118917

Friedman, M. (1970). A Friedman doctrine - The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine, 122–126.

Frow, P., McColl-Kennedy, J. R., Hilton, T., Davidson, A., Payne, A., and Brozovic, D. (2014). Value propositions: a service ecosystems perspective. Mark. Theory 14, 327–351. doi: 10.1177/1470593114534346

Geissdoerfer, M., Vladimirova, D., and Evans, S. (2018). Sustainable business model innovation: a review. J. Clean. Prod. 198, 401–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.240

Giddens, A. (1984). The Constitution of Society. Berkley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Grimani, A., Bergstrom, G., Casallas, M. I. R., Aboagye, E., Jensen, I., and Lohela-Karlsson, M. (2018). Economic evaluation of occupational safety and health interventions from the employer perspective: a systematic review. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 60, 147–166. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001224

Gröjer, J. E. (2001). “Intangibles and accounting classifications: in search of a classification strategy,” in Classification of Intangibles, eds J. E. Gröjer and H. Stolowy (Paris: Groupe HEC), 150–173.

Hamel, G. (2000). Leading the Revolution, Strategy & Leadership. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hofstede, G. (1978). The poverty of management control philosophy. Acad. Manage. Rev. 3, 450–461. doi: 10.5465/amr.1978.4305727

Islam, M. S., and Amin, M. (2022). A systematic review of human capital and employee well-being: putting human capital back on the track. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 46, 504–534. doi: 10.1108/EJTD-12-2020-0177

Jensen, M. C., and Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 3, 305–360. doi: 10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

Johanson, U. (1999). Why the concept of human resource costing and accounting does not work. Personnel Rev. 28, 91–107. doi: 10.1108/00483489910249018

Johanson, U., and Aboagye, E. (2020b). “Financial gains, possibilities, and limitations of improving occupational health at the company level,” in Handbook of Socioeconomic Determinants of Occupational Health - From Macro- Level to Micro-level Evidence, eds T. Theorell (UK: Springer).

Johanson, U., Almqvist, R., and Skoog, M. (2019). A conceptual framework for integrated performance management systems. J. Public Budget. Account. Financ. Manage. 31, 309–324. doi: 10.1108/JPBAFM-01-2019-0007

Johanson, U., and Henningsson, J. (2007). “The archaeology of intellectual capital: a battle between concepts,” in Chapter 2 in Intellectual Capital Revisited. Paradoxes in the Knowledge Organisation, eds C. Chaminade, B. C. Edvard Elgar, 8–30.

Johanson, U., Mårtensson, M., and Skoog, M. (2001a). Measuring to understand intangible performance drivers. Eur. Account. Rev. 10, 1–31. doi: 10.1080/09638180126791

Johanson, U., Mårtensson, M., and Skoog, M. (2001b). Mobilising change by means of the management control of intangibles. Account. Org. Soc. 26, 715–733. doi: 10.1016/S0361-3682(01)00024-1

Kant, I. (1996). Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785). In Practical Philosophy (England: Cambridge University Press), 37–108.

Karasek, R. A., and Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life. New York: Basic Books.

Kemp, P., and Hedenblad, R. (1991). Det oersättliga. En teknologietik. Stockholm: Östlings bokförl. Symposion 1991.

King, A. A., and Lenox, M. J. (2001). Lean and green? An empirical examination of the relationship between lean production and environmental performance. Prod. Operat. Manage. 10, 244–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1937-5956.2001.tb00373.x

Köhn, J. (1999). Sustainability in Question: The Search for a Conceptual Framework. Cheltenham, UK; Northampton: MA: E.Elgar.

Konar, S., and Cohen, M. (2001). Does the market value environmental performance? Rev. Econ. Stat. 83, 281–289. doi: 10.1162/00346530151143815

Kowalkowski, C., Kindström, D., and Carlborg, P. (2016). Triadic value propositions: when it takes more than two to Tango. Service Sci. 8, 282–299. doi: 10.1287/serv.2016.0145

Lapsley, I. (2009). New public management: the cruelest invention of the human spirit? Abacus 45, 1–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6281.2009.00275.x

Linder, J. C., and Cantrell, S. (2000). Changing Business Models: Surveying the Landscape. Working paper: Accenture: Institute for Strategic Change.

Maley, J. (2014). Sustainability: the missing element in performance management. Asia Pacific J. Bus. Adm. 6, 190–205. doi: 10.1108/APJBA-03-2014-0040

Malmi, T., and Brown, D. A. (2008). Management control systems as a package-opportunities, challenges and research directions. Manage. Account. Res. 19, 287–300. doi: 10.1016/j.mar.2008.09.003

Marcus, J., Kurucz, E. C., and Colbert, B. A. (2010). Conceptions of the business-society-nature interface: implications for management scholarship. Bus. Soc. 49, 402–438. doi: 10.1177/0007650310368827

Martinsson, C. (2017). Occupational Health and Safety Interventions - Incentives and Economic Consequences. (licentiate). Solna: Karolinska Institutet Stockholm.

Meyer, J. W., and Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 83, 340–363. doi: 10.1086/226550

Miller, P., and Haslam, C. (2009). Why employers spend money on employee health: Interviews with occupational health and safety professionals from British Industry. Safe Sci. 47, 163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2008.04.00

Mitchell, D., and Coles, C. (2003). The ultimate competitive advantage of continuing business model innovation. J. Bus. Strategy 24, 15–21. doi: 10.1108/02756660310504924

Murphy, K. (2017). The social pillar of sustainable development: a literature review and framework for policy analysis. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 8, 15–29. doi: 10.1080/15487733.2012.11908081

Nicholson, P. J. (2022). Occupational Health: The Value Proposition. London: Society of Occupational Medicine.

Noland, J., and Phillips, R. (2010). Stakeholder engagement, discourse ethics and strategic management. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 12, 39–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00279.x

Osterwalder, A., and Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. New Jersey: Wiley.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., and Tucci, C. L. (2005). Clarifying business models: origins, present, and future of the concept. Commun. Assoc. Inform. Syst. 16, 1–25. doi: 10.17705/1CAIS.01601

Patala S. Jalkala A. Keränen J. Väisänen S. Tuominen V. Soukka R. (2016). Sustainable value propositions: framework and implications for technology suppliers. Indust. Mark. Manage. 59, 144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.03.001

Perceva, C. (2003). Towards a process view of the business case for sustainable development. J. Corp. Citizenship 9, 117–132. doi: 10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2003.sp.00011

Raworth, K. (2012). A Safe and Just Space for Humanity: Can We Live within the Doughnut? Oxfam Discussion papers. Oxfam International. Available online at: https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/dp-a-safe-and-just-space-for-humanity-130212-en.pdf (accessed June 19, 2022).

Sánchez, P., and Ricart, J. (2010). Business model innovation and sources of value creation in low- income markets. Eur. Manage. Rev. 7, 138–154. doi: 10.1057/emr.2010.16

Schaltegger, S., and Burritt, R. (2018). Business cases and corporate engagement with sustainability: differentiating ethical motivations. J. Bus. Ethics 147, 241–259. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2938-0

Schaltegger, S., Hansen, E., and Lüdeke-Freund, F. (2016). Business models for sustainability: a co- evolutionary analysis of sustainable entrepreneurship, innovation and transformation. Organ. Environ. 29, 264–289. doi: 10.1177/1086026616633272

Schaltegger, S., and Hasenmüller, P. (2005). Nachhaltiges Wirtschaften aus Sicht des “Business Case of Sustainability. Lueneburg: Centre for Sustainability Management (CSM), Leuphana University of Lueneburg.

Schaltegger, S., Hörisch, J., and Freeman, R. E. (2019). Business cases for sustainability: a stakeholder theory perspective. Organ. Environ. 32, 191–212. doi: 10.1177/1086026617722882

Schaltegger, S., Lüdeke-Freund, F., and Hansen, E. (2012). Business cases for sustainability: the role of business model innovation for corporate sustainability. Int. J. Innovat. Sustain. Dev. 6, 95–119. doi: 10.1504/IJISD.2012.046944

Schaltegger, S., and Synnestvedt, T. (2002). The link between “green” and economic success: environmental management as the crucial trigger between environmental and economic performance. J. Environ. Manage. 65, 339–346. doi: 10.1006/jema.2002.0555

Schleicher, D. J., Baumann, H. M., Sullivan, D. W., Levy, P. E., Hargrove, D. C., and Barros-Rivera, B. A. (2018). Putting the system into performance management systems: a review and agenda for performance management research. J. Manage. 44, 2209–2245 doi: 10.1177/0149206318755303

Schoenmaker, D., and Shramade, W. (2020). Principles of Sustainable Finance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Searcy, C. (2012). Corporate sustainability performance measurement systems: a review and research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 107, 239–253 doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-1038-z

Seelos, C. (2014). Theorizing and strategizing with models: generative models of social enterprises. Int. J. Entrep. Venturing 6, 6–21. doi: 10.1504/IJEV.2014.059406

Simons, R. (1995). Levers of Control: How Managers Use Innovative Control Systems to Drive Strategic Renewal. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Sroufe, R. (2017). Integration and organizational change towards sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 162, 315–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.05.180

Steel, J., Godderis, L., and Luyten, J. (2018). Methodological challenges in the economic evaluation of occupational health and safety programmes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 2606. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15112606

Stubbs, W., and Cocklin, C. (2008). Conceptualizing a “sustainability business model.” Org. Environ. 21, 103–127. doi: 10.1177/1086026608318042

Tangen, S. (2005). Demystifying productivity and performance. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manage. 54, 34–46. doi: 10.1108/17410400510571437

Teece, D. J. (2010). Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plann. 43, 172–194. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.003

Tikkanen, H., Lamberg, J., Parvinen, P., and Kallunki, J. (2005). Managerial cognition, action and the business model of the firm. Manage. Decis. 43, 789–809. doi: 10.1108/00251740510603565

Upward, A., and Jones, P. (2015). An ontology for strongly sustainable business models defining an enterprise framework compatible with natural and social science. Organ. Environ. 29, 97–123. doi: 10.1177/1086026615592933

Wagner, M. (2001). A Review of Empirical Studies Concerning the Relationship Between Environmental and Economic Performance. What Does the Evidence Tell Us? Lüneburg: Center for Sustainability Management (CSM).

Wagner, M. (2003). An Analysis of the Relationship Between Environmental and Economic Performance at the Firm Level and the Influence of Corporate Environmental Strategy Choice. Lueburg: Lüneburg University.

Wicks, D. (1998). Organizational structures as recursively constructed systems of agency and constraint: compliance and resistance in the context of structural conditions. Can. Rev. Sociol. Anthropol. 35, 369–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-618X.1998.tb00728.x

Wijethilake, C., and Upadhaya, B. (2020). Market drivers of sustainability and sustainability learning capabilities: the moderating role of sustainability control systems. Bus. Strategy Environ. 29, 2297–2309. doi: 10.1002/bse.2503

Wirtz, B. W. (2011). Business Model Management Design, Instruments, Success Factors. Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Wirtz, B. W., Pistoia, A., Ullrich, S., and Göttel, V. (2016). Business models: origin, development and future research perspectives. Long Range Plann. 49, 36–54. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2015.04.001

Xepapadeas, A., and de Zeeuw, J. A. (1999). Environmental policy and competitiveness: the Porter hypothesis and the composition of capital. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 37, 165–182. doi: 10.1006/jeem.1998.1061

Yang, M., Evans, S., Vladimirova, D., and Rana, P. (2017). Value uncaptured perspective for sustainable business model innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 140, 1794–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.07.102

Yang, M., Vladimirova, D., Rana, P., and Evans, S. (2014). Sustainable value analysis tool for value creation. Asian J. Manage. Sci. Appl. 1, 312–332. doi: 10.1504/AJMSA.2014.070649

Yao, J., and Johanson, U. (2022). Stakeholder culture and motivation: a review of government-led health and productivity management and disclosure practice in Japan. Frontiers in Sustainability.

Zott, C., and Amit, R. (2010). Business model design: an activity system perspective. Long Range Plann. 43, 216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.004

Keywords: OHS, value, performance management, business model, value proposition

Citation: Johanson U, Aboagye E and Yao J (2022) Integrating business model for sustainability and performance management to promote occupational health and safety—A discussion of value. Front. Sustain. 3:950847. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2022.950847

Received: 23 May 2022; Accepted: 18 August 2022;

Published: 14 September 2022.

Edited by:

Bankole Awuzie, Central University of Technology, South AfricaReviewed by:

Lesiba George Mollo, Central University of Technology, South AfricaAmal Abuzeinab, De Montfort University, United Kingdom