94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. , 21 October 2022

Sec. Sustainable Consumption

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2022.949710

This article is part of the Research Topic From an Ethic of Sufficiency to its Policy and Practice in Late Capitalism View all 10 articles

Laura Beyeler*

Laura Beyeler* Melanie Jaeger-Erben

Melanie Jaeger-ErbenSustainable transformation toward a circular society, in which all ecosystems and livelihoods are protected and sustained, requires the integration of sufficiency in circular production and consumption practices. Beyond the technological promises to decouple resource use from economic growth, sufficiency measures to reduce production and consumption volumes in absolute terms are necessary. Businesses integrating sufficiency act as agent of change to transform current unsustainable practices along the entire supply chain. By observing the operationalization of sufficiency in 14 pioneer businesses, this study identifies dimensions and practice elements that characterize sufficiency in business practices. This study observed that the sufficiency in business practices mainly represents a rethinking of business doings on three dimensions: (1) rethinking the relation to consumption; (2) rethinking the relation to others; and (3) rethinking the social meaning of the own organization. Sufficiency practitioners understand production and consumption as a mean to fulfill basic human needs instead of satisfying consumer preferences. They co-create sufficiency-oriented value with peers in a sufficiency-oriented ecosystem and they redefine growth narratives by envisioning an end to material growth. Additionally, this study revealed that care, patience and learning competences are essential characteristics of sufficiency in business practices. Sufficiency practitioners reshape their business doings by caring for others and nature; they demonstrate patience to create slow, local, and fair provision systems; and they accept their shortcomings and learn from mistakes. Integrating elements of care, patience and learning in business practices reduce the risks of sufficiency-rebound effects. Ambivalences between the sufficiency purpose and growth-oriented path dependencies persists for sufficiency-oriented businesses. Further research should investigate pathways to overcome these ambivalences and shortcomings that sufficiency practitioners experience, for instance, by exploring political and cultural settings that foster sufficiency-oriented economic activity.

Pressure caused by anthropogenic activities on the biosphere's resilience and its natural ecosystems has grown continuously since industrialization and has not dropped, not even in recent years or since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015 (Rockström et al., 2009; IPCC, 2022a). In 2022, humanity exceeded an additional planetary boundary with environmental pollution by novel entities such as plastic (Persson et al., 2022). The green growth pathway based on efficiency and consistency strategies is currently failing its promises to decouple resource use and environmental impact from economic growth (Zink and Geyer, 2017; Hickel and Kallis, 2019; Parrique et al., 2019). Hence, scholars across disciplines are calling for reduction measures and demand-side mitigations to lessen production and consumption, especially in affluent societies of the Global North (Del Pino et al., 2017; Creutzig et al., 2018; Wiedmann et al., 2020; IPCC, 2022b). In its latest report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change emphasizes efforts to avoid production and shift consumption practices toward low resource and energy use, for example, in mobility or building sectors (IPCC, 2022b). A paradigm shift strengthening sufficiency-oriented strategies in political, economic, and social spheres is urgent to reach a safe operating space within planetary boundaries (Dearing et al., 2014; Raworth, 2017; O'Neill et al., 2018).

Sufficiency is often defined as the pursuit of a state of enoughness that replaces ever-expanding material consumption (Linz, 2004; Spangenberg, 2018; Spangenberg and Lorek, 2019). Sufficiency encompasses all efforts and strategies to reduce production and consumption in absolute volumes (Spangenberg, 2018; Wiedmann et al., 2020). It also advocates for a fair redistribution of wealth and a universal fulfillment of human needs for a good life (O'Neill et al., 2018; Spengler, 2018). While sufficiency started with consumers voluntarily reducing their material dependency (Gorge et al., 2014; Speck and Hasselkuss, 2015), many studies expand the responsibility for sufficiency to other economic and societal actors (Sandberg, 2021). These include businesses (Bocken and Short, 2016; Niessen and Bocken, 2021; Bocken et al., 2022), governments (Fischer and Grießhammer, 2013; Schneidewind and Zahrnt, 2014; Reichel, 2016; Spangenberg, 2018), and non-governmental organizations (Persson and Klintman, 2021).

Businesses can act as agent of change in the transformation of production and consumption practices toward slow, local, and socially just systems of provision (Heikkurinen et al., 2019; Jungell-Michelsson and Heikkurinen, 2022). Thanks to their strategic position in the supply chain, their decisions, orientations, or activities influence both upstream production and downstream consumption (Spaargaren, 2011). Thus, the possibilities for businesses to integrate sufficiency-oriented strategies have recently gained the attention of scholars. Studies have defined sufficiency-oriented strategies for businesses (Schneidewind and Palzkill-Vorbeck, 2011; Bocken and Short, 2016; Reichel, 2018), developed frameworks for sufficiency-oriented business models (Bocken et al., 2020, 2022; Niessen and Bocken, 2021), or identified marketing approaches to promote sufficiency-oriented consumption (Gossen et al., 2019; Frick et al., 2021).

According to current studies, a business is described to be sufficiency-oriented when the company implements sufficiency-oriented strategies, such as sharing, sufficiency-oriented marketing campaigns or long-lasting design in their business model (Niessen and Bocken, 2021). However, the sole focus on strategies potentially neglects sufficiency rebound effects. The implementation of sufficiency-oriented strategies does not directly guarantee production and consumption reduction. For example, restraining consumption saves costs that consumers might reinvest in other non-sustainable consumption areas (Alcott, 2008; Figge et al., 2014). Or Freudenreich and Schaltegger (2020) warn that current secondhand offers in fashion are not a substitute for primary production, but are rather implemented to gain new consumer segments. As for sharing models, Parguel et al. (2017) observed a consumption increase on secondhand sharing platforms instead of the desired reduction. Sharing is also criticized for prioritizing a commercial over a sustainability purpose (Ryu et al., 2019).

Additionally, empirical studies that observed the application of sufficiency-oriented strategies showed that companies mostly implement incremental sufficiency-oriented strategies, such as no ownerships or green product alternatives, rather than radical ones, which refuse consumption (Niessen and Bocken, 2021). A further study concluded that circular business models mostly focus on incremental innovation and thus only induce weak sustainability changes (Hofmann, 2019). Thus, business model frameworks seem inadequate for the complexity, collaboration, or interdependencies that sufficiency transformation calls for Massa et al. (2018), De Angelis (2022). For example, radical innovation, such as limiting or avoiding production of new goods (Heikkurinen et al., 2019; Jungell-Michelsson and Heikkurinen, 2022), or exnovation activities, where unsustainable practices and technologies are withdrawn from the market (Reichel, 2016), are rarely described in circular or sufficiency-oriented business model frameworks.

Thus, understanding sufficiency in business practices requires to look for characteristics beyond business strategies. Sufficiency necessitates alternative visions, values, or needs, as well as new norms, skills, knowledge that facilitate a cultural and societal context of frugality and enoughness (Schneidewind and Zahrnt, 2014). Through the lens of social practice theories, this study observes the implementation of sufficiency in business as a change of social practices and investigates specific practice elements that characterize sufficiency, such as social meanings (values, visions, norms, emotions), competences (skills, knowledge), and material arrangement (infrastructures, technologies, products, resources) and their dynamically evolving and changing interactions (Shove et al., 2012; Spurling et al., 2013). Social practice theories understand business as a complex social phenomenon that is routinely reproduced by a network of interlocking practices (Schatzki, 2002; Massa et al., 2018). It breaks with the fixed architecture and economic and commercial logic of the business model. It offers the possibility for example to observe how various goals of a firm are weaved into business routines and how synergies or trade-offs evolve if goals change and practices are adapted. Thanks to their particular focus on how social practices evolve, stabilize, change, dissolve and re-stabilize (Schatzki, 2002; Shove, 2010; Spurling et al., 2013; Loscher et al., 2019), social practice theories are valid as a conceptual background to investigate how businesses transform their doings toward a sufficiency-oriented and circular society (Jaeger-Erben et al., 2021b). This practice-based and empirical study investigated the following research questions:

1. How do sufficiency-oriented businesses operationalize sufficiency in their practices?

2. What are essential practice elements that characterize sufficiency in business practices?

The study contributes to the development of a systemic understanding and shared definition of sufficiency in business practices by offering insights from empirical data. A better understanding of sufficiency in action is essential for research and transition practice toward a circular society (see, for example, Calisto Friant et al., 2020; Jaeger-Erben et al., 2021a; Jungell-Michelsson and Heikkurinen, 2022). Recommendations for the integration of sufficiency in circular production and consumption practices can be further derived from results of the analysis.

The paper is structured as follows. The conceptual framework of the paper, a short review of the literature of sufficiency in business, and an introduction to social practice theory are depicted in Conceptual background section. Methodology section presents the methodology of the grounded theory applied to the sampling, collection, and analysis of the data. The findings in Results section describe in detail the three dimensions of sufficiency in business: (1) rethinking the relation to consumption; (2) rethinking the relation to others; and (3) rethinking the social meaning of the own organization. Three practice elements—patience, care, and learning processes—which shape all sufficiency dimensions, are also presented, and are revealed to be essential characteristics of sufficiency in business. Finally, in Discussion section, we discuss theoretical and practical implications of the findings, and we conclude by identifying limitations of the study and recommendations for future research.

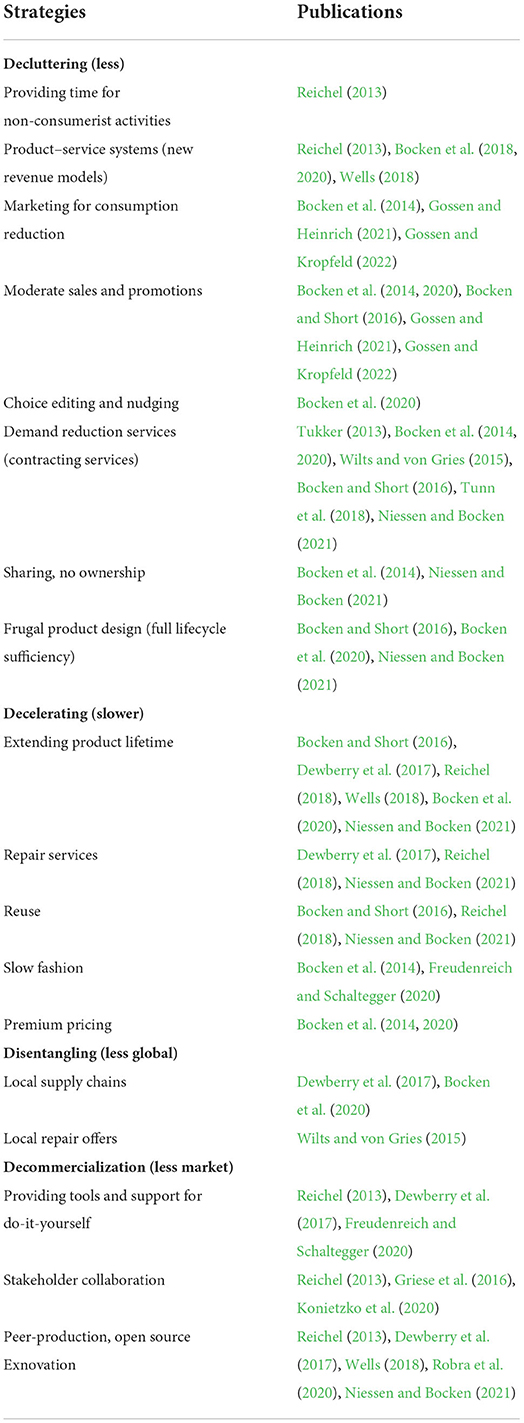

Recent studies defined sufficiency-oriented organizations as those that apply sufficiency-oriented strategies in their business models (Bocken and Short, 2016, 2020; Bocken et al., 2020). Sufficiency-oriented strategies support consumers to reduce their consumption and their material dependency (Bocken and Short, 2016). Additionally, sufficiency-oriented strategies allow businesses to reduce own production volume or avoid production in the first place (Reichel, 2013, 2018). Schneidewind and Palzkill-Vorbeck (2011) presented four lessening categories of sufficiency-oriented strategies: decluttering (less), decelerating (slower), disentangling (more local), and decommercialization (less market).

Decluttering entails various material and energy-reduction strategies, for example, product–service systems such as sharing models or energy-contracting services (Reichel, 2013; Tukker, 2013; Wilts and von Gries, 2015). Extending product lifetime with the production of long-lasting products or by offering repair and reuse options are typical decelerating strategies (Reichel, 2013). Strategies from the disentangling category consist of local supply chains (Dewberry et al., 2017; Bocken and Short, 2020) or stakeholder collaboration (Griese et al., 2016). Finally, decommercialization operates outside of market logics, by providing tools or instruction for self-production (Dewberry et al., 2017; Freudenreich and Schaltegger, 2020), or by developing open-source processes (Wells, 2018; Robra et al., 2020).

More recently, scholars observed an increase in sufficiency-oriented marketing that explicitly discourages consumers from purchasing new products (Gossen et al., 2019; Frick et al., 2021; Gossen and Kropfeld, 2022). Several studies connect sufficiency to low-growth strategies, calling for a redefinition of business growth (Khmara and Kronenberg, 2018; Wells, 2018; Bocken et al., 2020; Nesterova, 2020). Table 1 gives an overview of existing sufficiency-oriented strategies described in the literature.

Table 1. Existing sufficiency-oriented strategies in sufficiency and sustainable business model literature.

Social practice theories cannot be described as a coherent theory but as a bundle of conceptual approaches that share their main focus on social practices as the basic unit of analysis (Reckwitz, 2002). In contrast to the methodological individualism, where the social is thought to emerge from the constellation and accumulation of individual action or single interest, in social practice theories, the social is situated in social practices (Schatzki, 2018), which can be understood as routinized and organized activities performed by actors on a daily basis (Reckwitz, 2002). Social phenomena, such as economic production and consumption goods, start-ups, social organizations, or businesses, are grounded in a nexus of connected social practices (Schatzki, 2002, 2018). For instance, businesses are reproduced by a complex set of interlinked social practices such as advertising, financing, strategic planning, or human resource management (ibid.).

The definition of a social practice, and which elements form the practice, differs depending on the scholars of social practice theories (Gram-Hanssen, 2011). For this study, the social practice theory according to Shove et al. (2012) was applied. For Reckwitz (2002: p. 249), a practice consists of “forms of bodily activities, forms of mental activities, things and their use, a background knowledge in the form of the understanding, know-how, state of emotion and mental knowledge.” Building upon this definition, Shove et al. (2012) describe social practices as an entity of recognizable elements, which they grouped into three categories:

- Social meaning (values, emotions, social norms, or visions)

- Competences (skills, knowledge, or techniques)

- Material arrangement (objects, things, tangible physical entities, or resources)

The social practices are enacted and reproduced by individuals that perform the practices. Individual actors are understood as “carriers” or “performers” of the practices and their elements (Shove et al., 2012). The performance of social practices requires certain skills, the appropriation of particular purposes and values, or the display of emotions which are mainly attributed to the social practice itself and not to the individual carrier and his or her personal attributes (Reckwitz, 2002; Warde, 2005; Shove et al., 2012). Social practice theories have among other evolved as critic of the agent-based individualism prevailing in economic theory which broadens the perspectives of analysis in organization research (Whittington, 2011), as well as in sustainable transformation research (Shove, 2010; Spurling et al., 2013). Thus, various studies in organizational research apply social practice theory, for example, in organizational learning (Nicolini et al., 2016), information systems (Chua and Yeow, 2010), human resource management (Vickers and Fox, 2010), or marketing (Echeverri and Skålén, 2011). Interest in the practice-based approach is growing in research for sustainable transformation, for example, in sustainable consumption (Brand, 2010; Spaargaren and Oosterveer, 2010; Jaeger-Erben et al., 2015; Parekh and Klintman, 2021), sufficiency-oriented consumption, and lifestyle (Speck and Hasselkuss, 2015); in sustainable value co-creation (Korkman et al., 2010); or in the diffusion of sustainable product–service systems (Mylan, 2015).

According to Shove et al. (2012), social practices are dynamic and changing. Their descriptions of practice as an entity (observable elements) and practice as a performance (reproduction by the carriers) are useful for understanding how practices change, either through the emergence or disappearance of specific elements and new connections, or in the adapted reproduction of the practice by the carriers (Shove et al., 2012: p. 8). According to Spurling et al. (2013), unsustainable practices can be changed by carriers when they add, suppress, or modify specific practice elements during the practice reproduction. Entire practices can also be substituted with more sustainable alternatives, or transformation occurs when the interaction and connection between practices shift. This study paid particular attention to the change of social practices from business-as-usual to sufficiency-oriented practices of doing business, with the aim to understand how the business practices and the elements they consist of dissolved, evolved or changed, and finally stabilized with the integration of sufficiency.

Social practice theories neither are a coherent theory, nor do they imply a particular methodological approach (Shove, 2017). While the usual approaches are often qualitative inquiries (Halkier et al., 2011) like case studies, participant observation and interviews, there are few examples of quantitative methods (e.g., Browne et al., 2014; Jaeger-Erben et al., 2021a). For this study, we used a variety of qualitative data gathered during interviews, desk research, online documents, and audio recordings. We decided to follow the research design of Grounded Theory (Corbin and Strauss, 1990) in our attempt to explore and understand sufficiency in business practices. According to Suddaby (2006), “[grounded theory] was founded as a practical approach to help researchers understand complex social processes.” The integration of sufficiency in business practices can be viewed as a complex social process; namely, a social innovation requiring structural change in doing business. With its conceptual roots in the school of thought of Pragmatism (Strübing, 2007), Grounded Theory research is seen as particularly suitable to understand the contexts, logics, and structure of social practices. Based on empirical data, we build new understandings and classification of sufficiency characteristics in business practices.

We selected multiple cases (n = 14) of businesses implementing sufficiency-oriented strategies. Following the recommendation of Hensel and Glinka (2018), we used data triangulation to collected data from multiple sources: primary data from problem-centered interviews and secondary data from publicly available podcasts and written documents from the businesses. In accordance with constant comparison, the data analysis started directly after the collection of the first data. Categories and characteristics emerging from the data analysis were sequentially compared for homogeneity or heterogeneity in further primary or secondary data collection. Thus, the study followed an iterative abductive research procedure (Strübing, 2013). Characteristics of sufficiency in business practices were inductively extracted from interviews and podcasts, and deductively tested in follow-up interviews, podcasts, and in the secondary text material. Abduction is a creative research process, during which researchers produce new forms of knowledge from the abstraction and comparison of the practitioners' subjective experiences (Suddaby, 2006; Reichertz, 2013).

Theoretical sampling is—after constant comparison of data—the second essential precept of grounded theory (Suddaby, 2006). Theoretical sampling leaves it open to the researchers to select a diversity of different cases, which describe best various aspects of the phenomenon under study (Hensel and Glinka, 2018). In line with the iterative process, theoretical sampling does not require the researcher to know all the cases at the beginning of the research (Strübing, 2013). Only the first two cases were defined at the beginning of the study. The following business cases were selected during the iterative process of data analysis and collection. To facilitate the research of cases, we, however, still defined specific criteria for the sampling of the business cases. Thus, the following selection criteria were defined:

(1) Lessening strategies: The most important sampling criterion was that businesses implement sufficiency-oriented strategies. Thus, the four lessening categories from Schneidewind and Palzkill-Vorbeck (2011)—decluttering, decelerating, disentangling, and decommercialization—served as a guide to identify sufficiency-oriented strategies. As a criterion, it was decided that the companies must apply sufficiency-oriented strategies from at least one of these categories, preferably more. In the course of the iterative research process, we further narrowed the cases down to three main sufficiency-oriented strategies: (1) the production of long-lasting consumer goods (decelerating); (2) the offering of sharing services (decluttering); and (3) the facilitation and diffusion of repair possibilities (deceleration and decommercialization). Thus, all business cases build their business activities around one of these three sufficiency-oriented strategies. Additionally, businesses were selected when they were combining one of these main activities with other lessening strategies; for example, when businesses that produce long-lasting products (decelerating) also considered local supply chains (disentangling) or production limitations (decluttering).

(2) Sufficiency purpose: We paid attention to selecting businesses that publicly identified themselves or their pilot project with a sufficiency-oriented purpose, reaching for a reduction of resource and material use or of production or consumption volumes.

(3) Fashion and electronics sectors: The selection of businesses was restricted to B2C companies either in the fashion or in the electronics sector, because, according to the literature, many businesses in both sectors are already integrating sufficiency-oriented strategies. Sufficiency in both sectors is comparable, because both sectors offer long-lasting consumable goods to end consumers. Both increasingly test new business practices enabling, for example, repair, reuse, or supporting consumption reduction. Despite the necessity and high environmental relevance for considering sufficiency in other sectors—such as mobility, energy, or food supply—the dynamics and complexity of these systems were considered too diverse to compare sufficiency in business practices.

(4) Founders available for interviews or existing podcasts with founders: Interviews with the founders of the businesses or with employees in strategic positions were central for data collection. Thus, businesses that accepted the conducting of personal interviews were prioritized. Additionally, publicly available podcasts were also relevant for data input.

(5) European region and languages: To ensure comparability of settings and practices, only businesses located in Europe were selected. Additionally, only cases with primary and secondary data available in German, French, or English—according to the authors' spoken languages—were selected.

Cases were found via multiple Google searches with various keywords relating to the lessening categories in German, French, and English. Various websites with lists—for example, of businesses for the common good, certified B Corporations, or circular businesses—were also helpful in the sampling process. Additionally, personal connections with circular economy programs or Right to Repair roundtables completed the search for empirical cases. In the end, 11 selected cases were small- or middle-sized companies and three were larger companies with more than 500 employees, for example, one large international company that tested a sharing model of its outdoor products. An overview of the selected businesses is visible in Table 2.

The collection of primary and secondary data occurred from May 2021 to November 2021. Additionally, further secondary material to reinforce and actualize the iterative research process was collected and analyzed between July and August 2022. The problem-centered interview format for the collection of primary data suited well the inductive and deductive approach of the study (Witzel, 2000). The interviews were conducted with the founders of the businesses or with employees in strategic positions. The semi-structured questionnaire enabled the sufficiency practitioners to talk freely about the story of their business as well as their daily practices from acquisition of resources to consumption support and closed-loop services. Follow-up questions concerning the governance and culture of the business and the understanding of growth were asked, with the goal to uncover sufficiency elements in further business practices. The interview guidelines are available in the Appendix. We paid attention to select available podcasts that asked similar questions to the interview guidelines. Additionally, for each case, secondary data such as the companies' websites, blog posts, newsletters, TED Talks, sustainability reports, or press interviews were collected. Complementing the primary data with secondary material enabled us to observe the business practices from a different perspective as well as testing the statements from the practitioners via additional material.

Table 3 lists all the primary and secondary data collected for the study. It depicts the iterative collection and coding process by showing the different steps of data collection and coding. In each round, new questions for the interviews, the podcasts or the secondary data were addressed. The adaptation of the questions and interview guideline served the comparison process with the aim to confirm or refute categories that emerged in previous data collection and analysis rounds. While we started with small producing companies, larger sufficiency-oriented companies as well as companies with sharing and repair services were added to diversify the data set. Data from the last collection round addressed specific characteristics of sufficiency that repeatedly appeared in the data. Hypotheses about the limits to growth, the diffusion of practices or the care work along the supply chain were for example addressed in this final collection and coding round.

The interviews—either conducted by the authors or by journalists in podcasts—were central for observing business practices and identifying characteristics of sufficiency. Despite the unconscious and routinized performance of practices, practitioners can still talk about the practices they are embedded in Hitchings (2012). Individuals have access to the elements of the practices; they identify with them and thus can also talk about them. Even Bourdieu's concept of habitus reports a degree of reflexivity that leaves individuals the possibility to self-reflect upon their situation and perform change (Everett, 2002). In interviews, we were able to discuss and reflect elements of practices, and the strategies that are being tested, without expecting the practitioners to fully understand and describe the sufficiency-oriented practices they are performing (Hitchings, 2012; Shove et al., 2012; Spurling et al., 2013).

Categories and characteristics of sufficiency in business practices were inductively identified in interviews and podcasts and then deductively tested and compared in the follow-up interviews, as well as in the secondary data sources (Corbin and Strauss, 1990). Primary and secondary data was coded in ATLAS.ti following the three coding phases of Corbin and Strauss (1990); namely, open, axial, and selective coding. The open coding process generated a variety of sufficiency characteristics. The identified codes were then organized into higher-level categories and groups during the axial coding process. The interaction and connection between the categories were investigated during this coding phase. We tried to identify the causes and intervening conditions of sufficiency in business, as well as the consequences of the sufficiency-oriented strategies for the practitioners, for their ecosystems, and for the political and economic context. In the final phase of selective coding, the sufficiency characteristics, and their interactions, were synthetized regarding the research questions, with the aim to deliver a better understanding of the phenomenon sufficiency in business (Strübing, 2013). The writing of memos accompanied the entire data analysis and supported the progressive interpretation of the data.

Sufficiency in business practices emerges in all observed cases from the identification of the growth imperative and consumption affluence as main drivers of environmental destruction and social injustice. The desire to break path dependencies of exponential growth, or of an abundance of consumption, results in a quest for less materialistic, slower, and more local solutions to production and consumption. Sufficiency practitioners examine the manifold of elements that foster the growth imperative with the attempt to tackle these lock-ins directly. For example, practitioners in the fashion sector observe a reduction in textile and clothing quality intended to shorten product lifetime. According to the practitioners, this sort of planned obsolescence is strengthened by a culture that treasures the newest products, trends, or technologies and by rising investments in marketing. Sufficiency practitioners also deplore innovation and technological protectionism, which hinders access to, for example, repair. The race of profit-oriented investors for growth and financial returns is also condemned by the practitioners, so they are often searching for alternative investment sources.

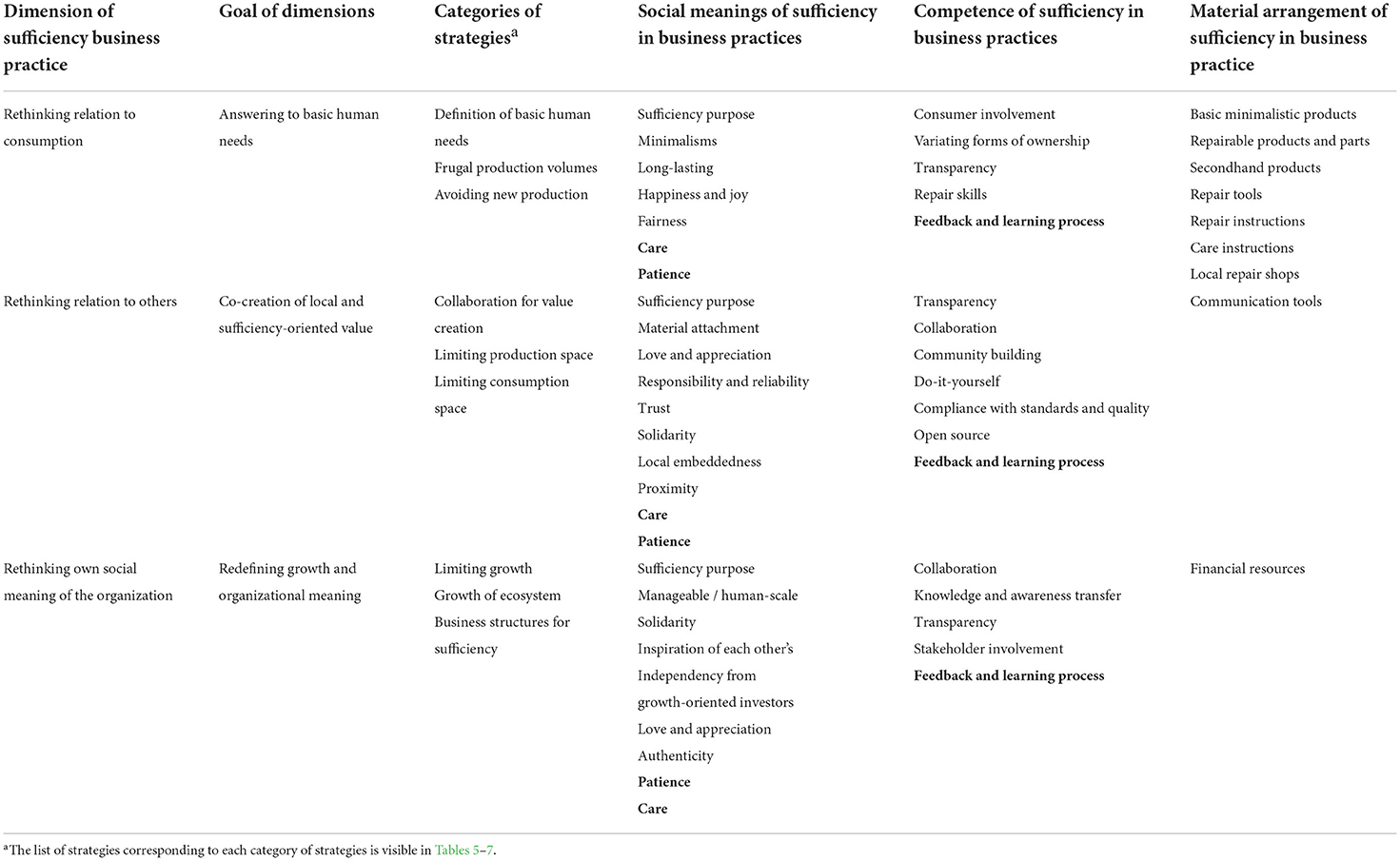

The intention to break the growth and affluence path dependencies consequently leads sufficiency practitioners to take time and offer space to develop a sufficiency-oriented way of doing business. The result show that sufficiency practitioners change their business practices in three dimensions: (1) rethinking the relation to consumption; (2) rethinking the relation to others; and (3) rethinking the social meaning of the own organization. Each rethinking dimensions is characterized by a specific goal and a variety of strategies that are implemented to fulfill the goals. Moreover, these rethinking processes, where alternative sufficiency-oriented business practices are shaped, are characterized by specific social meanings, competences, and material arrangement. Table 4 summarizes all the practice elements identified in the data that emerge and stabilize when integrating sufficiency into business practices. For example, rethinking the relation to consumption follows the goal to orient consumption toward basic human needs. This process requires among others high consumer involvement to co-create basic minimalistic products and design them to fulfill necessary needs. Rethinking the relation to consumption is also characterized by emotions of happiness and joy that are related to the reduction of material dependency. It is notable from Table 4 that patience, care and learning processes appear in all rethinking processes and that they reveal to be essential characteristics of sufficiency in business practices.

Table 4. Classification of codes according to the three dimensions of sufficiency in business practices.

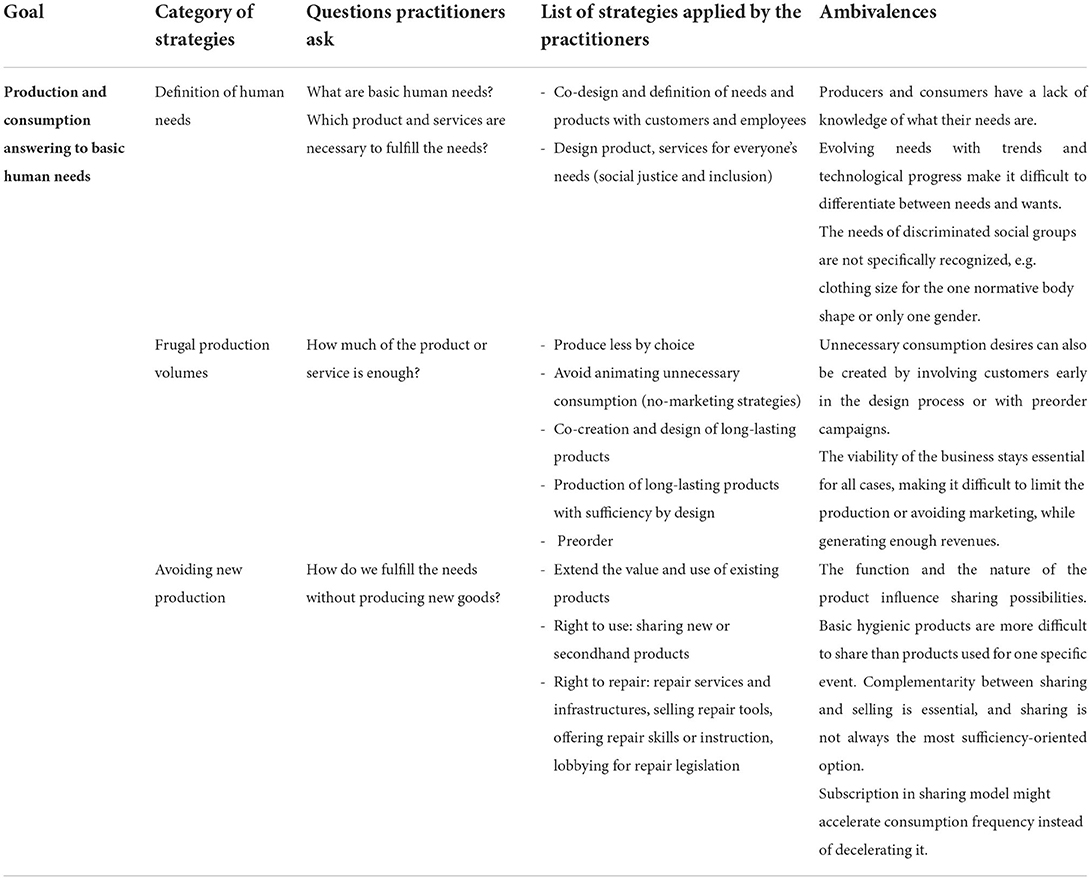

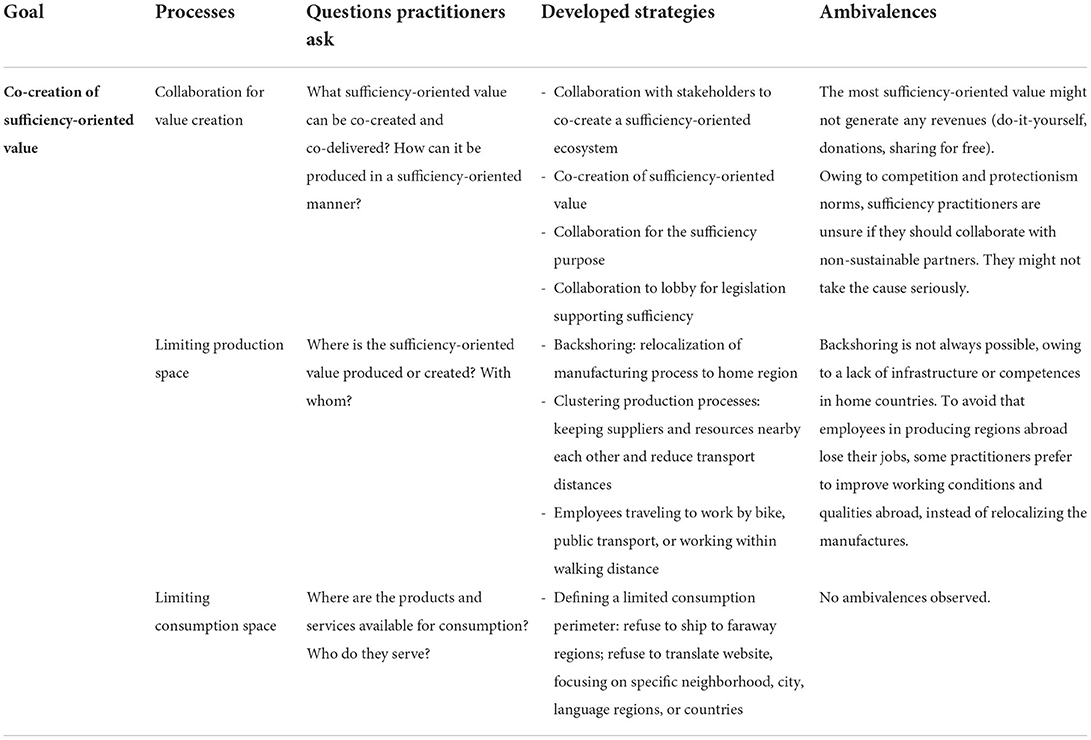

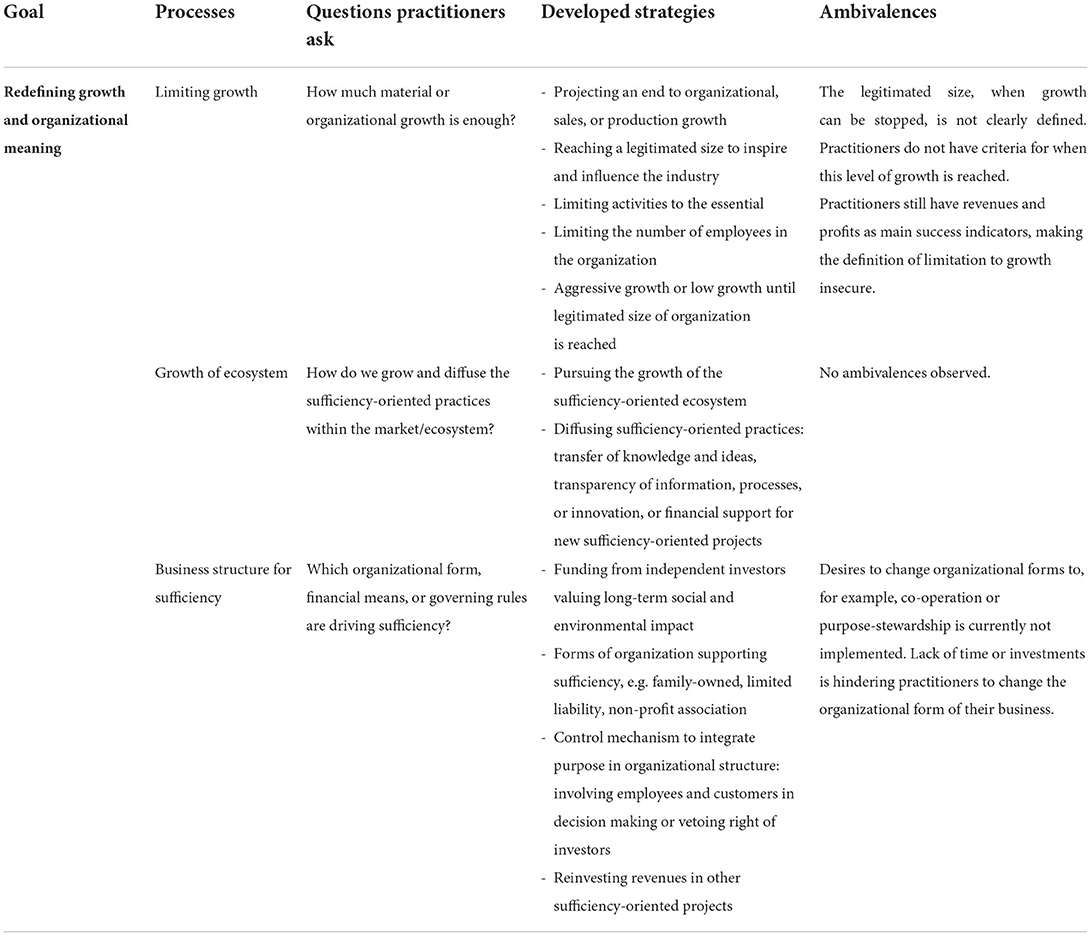

In the following, each rethinking dimension is described in further detail, with an emphasis on the strategies applied and the practice elements emerging. Each dimension is also characterized by ambivalences between the desire to be sufficiency-oriented and the dominant capitalist norms. These ambivalences reveal the difficulty for the practitioners to develop holistic sufficiency-oriented business practices and point to the risks of sufficiency rebound effects. Tables 5–7 summarize for each rethinking dimension the goals, the questions asked by the practitioners, the strategies applied in response, as well as the existing ambivalences.

Table 5. “Rethinking relation to consumption”: Relevant questions, strategies, and emerging ambivalences.

Table 6. “Rethinking relation to others”: Relevant questions, strategies, and emerging ambivalences.

Table 7. “Rethinking social meaning of the own organization”: Relevant questions, strategies, and emerging ambivalences.

Sufficiency practitioners want to ensure that their product palette exclusively answers basic human needs for a good life. They differentiate between products that satisfy human needs and products that satisfy superfluous consumer wants. Sufficiency practitioners criticize marketing strategies that created consumer wants and try to orient their activities toward the satisfaction of basic human needs, as described by this practitioner:

“Let's try to produce only the strict necessary, to buy only what we really need. We try to answer to the need to dress people, with sustainable materials, etc.... and not to create wants.” (Hopaal, publicly available podcast, December 30, 2020)

When asked about the basic human needs that the sufficiency practitioners are answering to, different needs are pointed out. Sufficiency practitioners in the fashion sector respond to the need to dress, since it is socially inappropriate to wear the wrong or no clothes. Consumers also have a need for clothing diversity because of the manifold dress codes in different life settings. Sufficiency practitioners in the electronics sector answer to the social need for communication and connectivity. Additionally, electronic devices are increasingly used in the professional environment, increasing the need for reliable hardware and software. Furthermore, the practitioners in both sectors mention the need for sustainable, long-lasting products, and for services to support the longevity of products.

Despite a strong desire to differentiate between needs and wants, the practical implementation appears challenging. The practitioners' selection of human needs to be fulfilled with their products and services does not follow clear evaluation criteria. Sufficiency practitioners randomly or subjectively define which human needs should be fulfilled with the provided goods and services and which should not. This subjective selection of needs does not differ considerably from the business-as-usual marketing of new products and services according to consumer preferences.

Besides aligning the value proposition to fulfill human needs, the sufficiency practitioners ought to define the right quantity of the products or services necessary to fulfill those needs. Contrary to consumer wants, which never reach saturation, needs can be satisfied (Gough, 2015). Sufficiency calls on practitioners to determine an adequate quantity of goods and services necessary to fulfill the needs of their customers.

To limit production volumes, practitioners try to avoid animating unnecessary consumption. Some sufficiency practitioners have no marketing budget and refuse to pay to attract customers. For example, practitioners can avoid advertisements, sales, or digital marketing instruments to manipulate consumers into unwanted or unconscious purchases. Sufficiency practitioners also refuse to offer limited mobile phone contracts, or seasonal and limited fashion collections, which subjectively shorten their use phase. Sufficiency-oriented marketing is confined to organic strategies, such as public relations, non-paid-for social media content, press appearances, or word of mouth. The purpose of marketing for sufficiency practitioners is to transfer knowledge and learnings about sustainable and sufficiency topics, transmit competences for careful material use, render unsustainable supply chains transparent, and inspire others with their alternative practices.

Another repeated strategy to limit production volume is the early involvement of consumers in the design and production phase, with preorder and co-creation processes. Several sufficiency practitioners ask their community to preorder their products before production. The practitioners will only produce the volume of goods that are ordered and hence necessary to fulfill the needs of their consumers. According to the practitioners, the longer waiting time until delivery fosters conscious purchase decisions. The willingness to wait seems to activate consumer reflection about the necessity to purchase a specific product and reduces impulsive consumption decisions. Co-creation aims at designing the products according to consumers' needs. The consideration of wishes concerning the functionality, design, material, or use of the products is likely to increase consumers' attachment to the product.

The most effective method to restrict production volume to the necessary is to avoid producing new products in the first place. Therefore, many sufficiency practitioners focus on extending the value of existing products. Instead of selling new products, sufficiency practitioners offer access to tools, competences, infrastructures, or services to care and extend the life of existing products. The data reveals that sufficiency practitioners avoid new production by advocating for two consumer rights: right to use (switching from owning to sharing) and right to repair (creating a repair culture).

Sufficiency practitioners introduce sharing offers to the market with the intention to optimize the use of products, especially to avoid unused products from lying in drawers or wardrobes while other users could benefit from them. For sufficiency, it is important that the sharing model is built upon the purpose to limit inflows of new products onto the market. When many consumers share the same objects, less production is necessary. Sufficiency practitioners play with different variants of product ownership to adapt their supply to consumers' needs. Accordingly, consumers do not need to own products which are not frequently used. Sharing is optimal for clothes only worn for special events or to give variety to the wardrobe. Renting is also relevant for one-time use of material or for adapting to rapid technological progress without the need to frequently buy new devices. Furthermore, some sufficiency practitioners value sharing models because of the possibility to try out and test products before purchasing. If the product is proven for everyday practical needs, a purchase for long-term use is worthwhile:

“The self-evidence of ‘I can have what I want now' in a wealthy society is quite common and we see that as problematic. And we are not saying that you should not own, but perhaps more consciously. That means that, with the question ‘Do I borrow a phone that I don't own?', there is also another question: ‘Do I need the phone now effectively?”' (AlderNativ, personal interview, October 14, 2021)

On the other hand, several sufficiency practitioners highlight that not all products are suitable for sharing. They mention, for example, regularly used or essential daily products as inadequate for sharing because of hygienic concerns, as highlighted in the following two excerpts:

“I think if you are running 20 km every day, I am not sure that after a month, the shoe can be rented again.” (Anonymous outdoor brand, interview, September 6, 2021)

“I would never rent, like, a white t-shirt to be honest, or a bra; that is something to consider.” (Palanta, personal interview, August 28, 2021)

Sufficiency, in practice, thus varies between ownership of essential daily used materials and renting of single-used products. The two modes are complementary and reduce the number of bad or superfluous purchases. Ownership is revealed as a useful variable within sufficiency-oriented business practices to keep unused goods in circulation and avoid unnecessary production.

Additionally, sufficiency practitioners advocate for a universal right to repair. They provide access to a variety of repair facilities, so that all products from any brand can be repaired by anybody, independently of the consumers' repair competences or economic situation. The repair possibilities vary according to the products and the materials. In the case of modular and repairable electronic devices that are designed to be repaired, sufficiency practitioners encourage and support their consumers to repair the products themselves. Tools and instructions are often automatically provided with the products. For electronic products that are not designed to be repaired, sufficiency practitioners engage in spreading instructions, tips, and tools for self-repair practices at home. In other cases, especially for clothes, repairing requires expensive technologies such as industrial sewing machines and professional sewing expertise. Learning to repair clothes necessitates time and a financial budget that many consumers might not have. Local repair shops and facilities are thus another important sufficiency practice for the right to repair.

The application of these strategies—from organic marketing, preordering, and co-creation to sharing and repairing—do not systematically implicate sufficiency. For example, with the early involvement of consumers in co-creation activities or preordering, the business still risks inciting consumption desires that are superfluous. Co-creation and preordering may turn out to be intensive early marketing, even without an important marketing budget. A subscription model making consumers pay a monthly contribution to rent products could provoke an acceleration of consumption instead of a deceleration, because consumers have the incentive to pay off the cost of subscription. Only frequent consumption makes subscription worthwhile. This seems to go against the willingness of sufficiency practitioners to promote long-term use of products and reduce the frequency of consumption. Some practitioners, moreover, offer monetary vouchers if the consumers bring back old products for reuse. While the goal to recuperate unused clothes contributes to sufficiency, the voucher still encourages the consumer to buy a new product. In all cases, those strategies can only be sufficiency-oriented with the aspiration to match basic human needs and to limit production volume to the necessary. Without the quest for basic human needs, these strategies can lead to more material consumption instead of sufficiency.

Sufficiency practitioners mention the limitation of a single company to transform the practices of the industry. They all engage in collaboration with like-minded, purpose-oriented organizations, because they are critical toward the dominant logic of competition:

“At the beginning, they were trying to put us in competition with others, and it was keeping me up at night. I mean, I don't like this tension… I met all the young French textile brands, we all get along well, we do things together sometimes, we call each other, we help each other. I don't need to be in a competitive world because I don't need to be the first, I don't need to win all the market shares.” (Loom, personal interview, June 11, 2021)

The collaborations have various forms and goals. Some practitioners offer consulting and support services for other organizations to help them on their sustainability transformation path. Others form partnerships to cover a need or an activity in the supply chain that they are not specialized in, or that one company cannot cover alone. For instance, the outdoor brand reached out to a start-up to manage its renting project. Fairphone partnered with a French company for the take-back, reuse and recycling of smartphones. Overall, sufficiency practitioners support each other with the goal to create a sufficiency-oriented ecosystem and enable social change together. Or, in the words of the founder of Ifixit:

“We invest time, energy, and money because we are concerned with initiating a process of change. It's a kind of social commitment where you can go a long way.” (Ifixit, personal interview, October 11, 2021)

These processes of change are reinforced by collaborative lobby activities that the practitioners engage in. While individual companies fall short in transforming structural and institutional practices, the sufficiency-oriented businesses join forces to advocate for legislations that support sufficiency-oriented practices. For example, following a call from Loom, 400 French fashion companies joined forces to lobby for legislation to encourage a reduction of production volumes, support reuse, and enable the decarbonization of production processes (En Mode Climat, 2022). Bis es mir vom Leibe fällt, Ifixit, and R.U.S.Z engage with associations that advocate, for example, for a value-added tax exemption for repair services, or for financial repair bonuses that would make repairs financially accessible to everyone.

The value co-created in the ecosystem goes beyond the sum of the product and services offered by each practitioner. The efforts and collaboration of the practitioners extend the intrinsic value of existing products or obsolete material. For example, encouraging consumers to repair or take care of their products reinforces the attachment that individuals have to their personal objects or materials. Sufficiency practitioners deliver to users a feeling of appreciation for existing material and resources. Appreciation is delivered to consumers with the transfer of creative ideas, skills, or instructions for the repair or reuse of unused products. Additionally, a key process to extend use and value of products is open source, allowing everybody to improve existing technologies (especially hardware and software). Fairphone, with its open-source community, succeeded in updating the seven-year-old operating system for the Fairphone 2, which was no longer supported by the chipset provider (Fairphone, 2022).

Besides collaboration, local embeddedness and proximity to both suppliers and consumers are central to the ssufficiency practitioners, who do not perceive globalized markets as unlimited expansion and growth opportunities. Rather, most of the practitioners try to concentrate their production and consumption activities to defined regional perimeters. According to sufficiency practitioners, the limited operating perimeters improve the transparency of the supply chain and the compliance of suppliers with social and environmental standards. Proximity enables partnerships with local organizations and communities. Consumers benefit from direct access to repair and reuse services and employees can walk or cycle to their offices. Strategies to reduce both production and consumption perimeters are observed.

In the fashion sector, producing sufficiency practitioners have relocated their supply chains entirely to European countries. Backshoring of fashion supply chains represents, for many practitioners, a gain in trust and control of environmental and social impacts in the value chains. The practitioners quote several benefits from production relocalization: stricter environmental and employment laws in Europe; fewer intermediaries in the supply chain; shorter transport distances; use of local and sustainable resources; and trusted collaboration with strong sustainable partners. However, there are significant differences between the sectors. Backshoring in the fashion sector is possible because the manufacturing infrastructures, as well as the producing knowledge and competences, are still available in Europe despite globalization and de-localization trends. In comparison, backshoring in the electronics sector is more complicated and cost intensive, because the infrastructure and competences to produce specific components of electronic devices are concentrated in few regions; for example, chips and batteries in China. In consequence, the goal of reducing production space is transferred to minimizing transport distances during the entire production process, by keeping suppliers and manufacturers close to each other, rather than an obligation to locate the entire manufacturing process near the consumption regions. According to sufficiency practitioners, consumption and production do not necessarily occur in the same geographical regions.

On the consumption side, sufficiency practitioners intend to provide comprehensive, reactive, and qualitatively high services for sufficiency-oriented lifestyles, such as sharing, repairing, reusing, or upcycling. For fast and reliable customer services, some sufficiency practitioners decide to limit their consumption and delivery perimeters to European countries, specific language regions, cities, or, with regard to practitioners with local shops, neighborhoods. For instance, two practitioners decided not to translate their online shops and websites. Restricting communication to the native language indirectly leads to a limitation of the delivery perimeters. This strategy is motivated by the desire to develop close relationships with the consumers. Sufficiency practitioners cultivate their consumer relationship because they rely on high consumer involvement and feedback to improve their sufficiency-oriented practices.

The sufficiency practitioners describe alternative understandings of growth. It is notable from the data analysis that most sufficiency practitioners are critical of exponential economic growth. They all project an endpoint to their own growth, be it in organizational size, sales, or revenues. In many cases, they aspire to reach an organizational size that gives them enough market legitimation to influence market structures and inspire other organizations with their sufficiency practices:

“We don't envision to become the new Apple. Rather that the big companies that produce phones go step by step down the road that we prove to be possible” (Fairphone, personal interview, June 15, 2021)

Some practitioners, having reached a satisfactory business size, do not aspire to growth further organizationally. For instance, they build an effective set of practices based on the current numbers of employees and activities. With a small number of employees, the practitioners can nurture a sufficiency-oriented work culture, with fewer working hours and more time for care work and leisure activities. A limited number of activities allows the practitioners to keep the processes and operations within a manageable frame.

Even though some practitioners try to stay within their current organizational size, it must be noted that most cases continue to experience material and production growth. Only Patagonia has communicated its wish to stop growing its production volumes and to switch to secondhand and sharing services instead (Kaufmann, 2021). Currently, one section of the practitioners adopts an active and assertive growth strategy to rapidly gain market legitimation and, simultaneously, to grow in environmental and social impact, as described by this practitioner:

“The more our modular phones circulate in Switzerland, the better, of course, because then fewer unsustainable phones will be in circulation.” (AlderNative, personal interview, October 14, 2021)

The second set of sufficiency practitioners adopts an agnostic attitude toward sales growth. The quality of products and services ranks above the sold quantity. Sales continue to grow because the demand for sustainable products and services increases. However, the sufficiency practitioners do not invest in marketing and sales strategies to increase their growth rates. Growth can occur, but it is not the main driver of each company's activities.

In all cases, societal and environmental impact is prioritized over the growth of revenues and profits. Sufficiency practitioners understand growth as the diffusion of sufficiency-oriented production and consumption practices. They aspire to the proliferation of sufficiency-oriented initiatives and organizations on the market. Collective growth of sufficiency-oriented ecosystems prevails over individual growth. Ecosystem growth implies the transfer of ideas and knowledge to other practitioners. Inspiration and transparency play an important role in the diffusion process. Although the sufficiency practitioners were often the first to develop their fair, local, and slow practices, many sufficiency practitioners list their entire supply chain, activities, and partnerships on their websites. Technological innovations are also not protected by patents and openly available to others. Sufficiency practitioners connect with partners in different regions to transfer their practices, encourage enterprises with the same ideas, or financially support the development of new sufficiency-oriented projects. Often, the practitioners do not financially profit from franchising or transfer of practices, because they aim for a diffusion of their practices, not for the company's prosperity.

Even though sufficiency practitioners are not primarily oriented toward profit maximization, it does not mean that sufficiency does not generate revenues. Most of the investigated cases are profitable. The profits are reinvested for the purpose of sufficiency. Either the profits are reinvested in the own company, for future development and to improve business practices, or the profits are distributed to other sufficiency-oriented projects to enable ecosystem growth. For example, cross-financing of projects with a sufficiency purpose is a common procedure for the sufficiency practitioners.

Besides redefining the meaning of growth, sufficiency practitioners also rethink their business roles. They choose legal organizational forms that best fit their sufficiency purpose. For example, the businesses included in this study are limited liability companies, family-owned businesses, or non-profit associations. These legal forms are selected because they allow the practitioners to keep their independence from external shareholders. Sufficiency practitioners wish to conserve their decisional responsibility and avoid their decisions being influenced or driven by external profit-oriented investors.

The question of financial ownership seems essential for sufficiency-oriented businesses. Sufficiency practitioners select investors that value long-term societal impact and wish to encourage the sufficiency purpose. The capital of sufficiency practitioners all comes from purpose-oriented financial investments: foundations, crowdfunding, cross-financing from other sufficiency-oriented projects, personal investment, or a mix of these. Financial ownership stays in the hands of like-minded share- or stakeholders that do not focus mainly on investment returns. In some cases, the investment does not have any promise of returns, which resembles private donations. Appreciation of the project and its sufficiency-oriented purpose is the main investment concern.

Sufficiency practitioners desire to institutionalize the purpose of sufficiency further in their organizational structure, for example, by involving employees and consumers in the decision-making processes with democratic structures or with fair revenue distribution. Loom, for example, aspires to a more co-operative form of organization to counter trends of market concentration and the establishment of monopolies. Those structures, however, are not yet implemented by the sufficiency practitioners included within the study. Only a projection of future forms of organization that best serve sufficiency is observable, as explained by this practitioner:

“No, we are not a co-op at all, we're a normal company. And right now, it's all based on our beliefs with my partner. But one day we'll have to change that... for the moment, we have other things to worry about, but it's a subject that we'll keep in mind and that we'll explore.” (Loom, personal interview, June 11, 2021)

While, in each sufficiency dimension, a variety of different sufficiency-oriented strategies were observed, the study identified three practice elements that influence the design and development of all sufficiency-oriented strategies. Care, patience, and learning processes as elements of social meanings and competences shape sufficiency in all business practices, from sourcing and production to distribution and consumption services, without ignoring supporting activities such as human resources or marketing and communication. Thus, the ability of a business to contribute to the reduction of production and consumption volumes is influenced by the value ascribed to and competence shown in caring for humans, nature, and the material world; by competence in slowing down all processes, to accept to wait and take more time in the performance of practices; and, finally, by the competence in honestly accepting and learning from mistakes, while reaching for feedback and constant improvement for the purpose of sufficiency.

Profit maximization and rapid returns on investment, as well as steady sales and revenue growth, are usually the norms for successful businesses in the dominant capitalist system (Donaldson and Walsh, 2015). From the data, it is observable that it is difficult and inconvenient for both producers and consumers to oppose these standards. Efforts to reduce production and consumption volume necessitate time, reflection, creativity for alternative solutions, and, often, financial investments without security for returns. Sufficiency practitioners take these efforts into account because they care for the environment and social justice. For sufficiency practitioners, the capacity to care for humans and their needs, the protection of the environment, and the longevity of materials and products occur as factors of resistance to the growth imperative and affluence of consumption.

Sufficiency practitioners describe sufficiency in production and consumption practices as care work along the entire supply chain. Care work takes the form of efforts to improve working conditions and sustain fairness in the supply chain. It is care for employees' wellbeing and possibility to reduce working hours so that they can, in turn, have more time for personal care work as well as leisure activities. If sufficiency requires consumers to invest time and energy in repairing and caring for the long-lasting use and reuse of materials, sufficiency practitioners like Loom or Hopaal start by offering this time outside of working hours to their own employees. The sufficiency practitioners also care about long-term relations with their consumers, especially to guarantee support for long-lasting use of their products even years after purchase. Patagonia, for example, offers a lifelong guarantee for repair and Loom stays in contact and gathers feedback on the condition of and consumers' relation to their products as long as three years after purchase. Besides caring about fair relations with others, sufficiency practitioners are also concerned about the quality and careful usage of the products and materials they produce or distribute. All producing practitioners in the study pay attention to ensure the highest quality for long-lasting and multifunctional usage of their products. Testing product prototypes and refusing to market products before they reach the expected quality is usual practice for sufficiency practitioners. Instructions, infrastructures, tools, and the transfer of skills to consumers to ensure a careful usage of material is also a common goal of the practitioners, especially in sharing models, as the products undergo several use phases by different consumers.

Despite positive communications about caring for a more sustainable world or, for example, the feeling of joy and happiness often related to repair activities or to less materialistic consumption practices, the results show that care in sufficiency-oriented practices is time intensive. It influences the temporalities and notion of time in business practices. While current economic activities are increasingly oriented toward efficiency and time reduction, sufficiency practitioners in the study rely on patience and long-term planning.

Sufficiency practitioners take time to produce, to comply with social and environmental standards, and to ensure quality for long-lasting products. A slowing down of production processes, for instance, emerges from the attention that sufficiency practitioners pay to the health and wellbeing of employees and workers along the supply chain. Pressuring suppliers with short delivery deadlines is out of order for every producing sufficiency practitioner. On the consumption side, patience is mirrored in the willingness to wait for the products and services, sometimes several months between preorder and product delivery. Moreover, because products ought to be used for a longer period, this requires time in daily life for care activities, such as repair or reuse. Finally, patience affects the time horizon of the business, switching from short-term to long-term thinking and planning. Short- or middle-term results and impacts of sufficiency in society might not be visible. Sufficiency practitioners mention that sufficiency-oriented transformation processes necessitate time and thus long-term vision and plans. According to some practitioners, even if results are not visible in their lifetime in the organization, every action toward sufficiency-oriented impact is worthwhile and necessary.

Closely related to care and patience are the learning processes that are mentioned with great consistency by the practitioners in the study. Sufficiency practitioners describe themselves as pioneers in their industry, because they were the first to introduce sufficiency-oriented products or services in their local markets or to fundamentally change practices in the supply chains. Being pioneers for sufficiency necessitates an acceptance of mistakes and having space for trial and error. Sufficiency practitioners value honesty and transparent communication of their learnings and potential failures. Mistakes and the strategies to improve them are often openly communicated on their websites. Several practitioners removed products from their assortments or stopped making specific products because of identified shortcomings. With care and patience, sufficiency practitioners rework their products and services, improving them until they reach an expected quality to be put back on the market. Several practitioners mention that the competence to accept and recognize mistakes and shortcomings is necessary to stay authentic to their sufficiency values and goals.

The learning process of sufficiency practitioners is based on regular feedback loops and the involvement of stakeholders, especially consumers and employees. For instance, Patagonia's decision to stop its production growth resulted from a survey filled out by employees of the company after the Covid-19 pandemic. In the words of the CEO:

“We asked all of the employees everywhere in the world to answer four questions (…) in essence, they were: What are the things you're learning through this period? What would you like to see us change? (…) And I think one of the things that came back with incredible consistency from our employees was we should make less product, we just make too much product.” (Patagonia, publicly available podcast, February 2, 2021)

The ability to listen to the feedback of employees or consumers and react to it seems essential for focusing on the real needs of the consumers, ensuring long-lasting quality of products and services, or strengthening sufficiency-oriented strategies and practices. Moreover, sufficiency practitioners often collaborate with research institutions to develop scientifically based solutions or to support their existing practices with scientific facts. Overall, the experience gained from the learning processes serves the stabilization and diffusion of sufficiency-oriented practices in markets and society.

By observing sufficiency in business practices as a change of social practices, the findings of the study show that doing sufficiency consists of the rethinking of three dimensions of current business doings. Sufficiency practitioners change their relation to consumption, their relation to others as well as the social meanings of their own organization. Behind a manifold of sufficiency-oriented strategies that are being applied in these rethinking dimensions, specific elements of social meanings, competences, and material arrangement shape sufficiency in business practices. Practitioners not only implement sufficiency-oriented strategies, but they also discover and develop new values, norms, competences, and processes. They identify relevant values and describe the emotions that emerge in the process, or invent rules and structures that reinforce these values. Materials and infrastructure are also designed to serve the sufficiency purpose. At the same time, the findings show the emergence of ambivalences and difficult-to-avoid rebound effects despite the desire to be sufficiency-oriented. Beyond their own business boundaries, practitioners must collaborate with other like-minded organizations to lobby for structural and political change. In the following sections, we discuss the contribution of the study to theoretical understandings of sufficiency and the practical implications for economic and political actors. We reflect on the limitations of the study and suggest further research paths.

A growing research field contributes to the understanding of sufficiency in production and consumption practices. The foundational work to define sufficiency-oriented business models has roots in conceptual studies based on literature and practice reviews (Schneidewind and Palzkill-Vorbeck, 2011; Bocken and Short, 2016; Reichel, 2018; Freudenreich and Schaltegger, 2020). While conceptual frameworks of sufficiency-oriented businesses and relevant strategies have been empirically tested (Niessen and Bocken, 2021), and completed with evidence from several case studies (Bocken and Short, 2016; Bocken et al., 2018, 2020), empirically grounded knowledge about the operationalization of sufficiency in business practices is still missing. This study contributes to the understanding of sufficiency in business practices by offering insights about the daily realities of sufficiency practitioners. Beyond the implementation of strategies defined in the literature as sufficiency-oriented, such as sharing, preordering, or frugal design, this study investigated what it means for practitioners to be sufficiency-oriented organizations and which elements of their practices (social meanings, competences, and materials) are essential for their sufficiency orientation. In consequence, it is possible to compare the practitioners' experiences with strategies and recommendations from existing sufficiency literature and observe which aspects have been adopted, or which might have been rejected or are still missing application in praxis.

The fulfillment of basic human needs is inherent to the definition of sufficiency (Spengler, 2018; Jungell-Michelsson and Heikkurinen, 2022). Scholars advocate for consumption adjusted to basic needs instead of wants (Gorge et al., 2014; Yan and Spangenberg, 2018; Spangenberg and Lorek, 2019) or for need-oriented policies centered on the satisfaction of the population's basic needs (Schneidewind and Zahrnt, 2014; Callmer and Bradley, 2021). Beyond these concepts lies the premise that all systems of provision should be built upon a theory of needs (Upward and Jones, 2016; Creutzig et al., 2018; O'Neill et al., 2018; Gough, 2020). For example, Ramos-Mejía et al. (2021) place the notion of universal human needs at the core of any economic activity of a postgrowth era.

The results of this study confirm the link between sufficiency and the fulfillment of basic human needs, as sufficiency practitioners attempt to answer basic human needs with their offerings. The satisfaction of human needs is operationalized in practice by various strategies. Sufficiency practitioners pay especial heed to limiting their production to the necessary or avoiding production of new goods. The involvement of consumers in early stages of production, or in the design of services, helps practitioners identify the needs of their consumers. However, despite practitioners' desire to implement a theory of needs, their definition of needs is arbitrary and relies on the capacity of consumers to differentiate between their needs and preferences—a task revealed to be difficult for consumers, who are not sovereign in a cultural and economic context that worships individual desires and wants (Gough, 2015). Hence, sufficiency practitioners and their consumers lack knowledge and political support in defining what basic human needs are. Participative processes—which combine expert knowledge, scientific advances, and the individual experiences of local consumers and communities—seem necessary to collectively identify human needs (Gough, 2017; Guillen-Royo, 2020). The definition of human needs on a societal level could additionally be added to political agendas to guide sufficiency-oriented businesses (Gough, 2017; Di Giulio and Defila, 2019).

The co-creation of sufficiency-oriented value observed in the data is also reflected in previous studies on sustainable business practices. Collaboration is, for example, a key factor in advancing the circular economy (Hofmann, 2019; Konietzko et al., 2020); stakeholder collaboration has also been described as an important component in sufficiency-driven businesses (Reichel, 2013; Griese et al., 2016; Bocken et al., 2022). Recent studies revealed the relevance of regional embeddedness and local production and consumption systems for sufficiency-oriented business practices. Offering quality local products (Bocken et al., 2020), local and co-manufacturing systems (Dewberry et al., 2017), or strengthening local take-back and reuse services (Freudenreich and Schaltegger, 2020) are examples of sufficiency-oriented strategies that were successfully implemented by the practitioners in the study. The strategies applied by practitioners to limit the consumption space are consistent with findings from Niessen and Bocken (2021), which described them as short-distance promotion strategies. However, the findings of this study indicate that limiting consumption perimeters is not only linked to promoting more local consumption practices; sufficiency in action also involves actively avoiding and refusing both material consumption and production, for example, by refusing to translate online shops or to sell specific products because they do not answer to human needs, or by avoiding making new products and, instead, switching to secondhand goods or repair services. The possibilities to interrupt material consumption and fulfill needs outside of current market logics remain unexplored in sufficiency research. Free peer-to-peer exchange, support for do-it-yourself, large-scale exnovation of unsustainable practices or technologies, and established companies intentionally disrupting production and sales spirals are examples of sufficiency practices that require better attention in research. These practices potentially could engender greater reduction of material dependencies.

Rethinking the notion of growth in a business context is a central aspect of sufficiency (Liesen et al., 2013; Reichel, 2013, 2016; Bocken et al., 2020). Degrowth scholars have also been investigating the form and role businesses play in a postgrowth society (Khmara and Kronenberg, 2018; Wells, 2018; Nesterova, 2020; Robra et al., 2020). The findings of this study are, for instance, consistent with the principle of degrowth businesses from Hankammer et al. (2021). The sufficiency purpose of the businesses, the sharing possibilities and alternative forms of ownership, the dedication to improve the work–life balance of employees, or the local embeddedness of the sufficiency practitioners are all characteristics of degrowth businesses. The deviation from profit maximization imperative described by Nesterova (2020) is an aspect that is reflected in the sufficiency practitioners' understanding of growth. Sufficiency practitioners value co-operation over competition, focus on quality over quantity, and are willing to operate on smaller organizational scales. With these alternative meanings of organizational and material growth, the findings also mirror prior studies describing low-growth strategies (Reichel, 2013) or advocating for an agnostic attitude toward growth (Raworth, 2017). New to the understanding of growth in business practices is the finding that sufficiency practitioners envision an end to their material and organizational growth. This limitation enables practitioners to define how much growth is enough and, from that point on, to focus on the diffusion of sufficiency practices and the collective growth of their ecosystem. However, sufficiency practitioners encounter difficulties in defining the “ideal” organizational size. They lack criteria and indicators to concretely determine a limit to material growth. It seems that no practitioner knows when a steady state could be reached, which allows sufficiency practitioners to continuously postpone their end to material growth. More research should be done to better assess when a company owns enough market legitimation and influence to stop production and organizational growth.

The systematic review on sufficiency by Jungell-Michelsson and Heikkurinen (2022) reveals that altruism is a central premise of sufficiency. In contrast to prevalent egoistic interest, sufficiency requires people to care for others and nature. Caring for and sustaining long-lasting relations with others, nature, and the material world are also an essential finding of this study. Sufficiency practice can be described as care work along the entire supply chain. The ability to care is key in the practitioners' quest to unlock growth-oriented path dependencies. Instead of profit-oriented product and service design, sufficiency practitioners care for long-lasting use of materials. Instead of low producing costs and ignorance of working conditions, sufficiency practitioners care for the wellbeing of all employees and workers. Meißner (2021) observed the influence of care on the repairing practices in repair cafés. Care does not only affect the decision to deal with obsolete objects, but it also influences how individuals interact with their neighborhood, how they pay attention to the inclusion of people, or how they save resources in daily life. Similarly, care in sufficiency-oriented business practices drives sufficiency practitioners to resist against current norms of business-as-usual and to invest efforts in all business activities so that a reduction of consumption and production becomes feasible.

Care, patience, and learning processes have the capacity to minimize sufficiency- rebound effects because they create a business practice that is aware of the risks and limitations of sufficiency-oriented strategies. The quality and feasibility of products, services, or business processes are tested and improved with care and patience. Once these are implemented, the culture of learning prevailing in sufficiency-oriented businesses enables adequate reaction and improvement in case of shortcomings or emerging rebound effects. From a practice theory perspective, the findings of this study call for research in sufficiency-oriented business practices to look beyond mere strategies and to search for characteristics supporting, shaping, and connecting strategies and business models; that is, elements that could be key for practitioners in diffusing sufficiency practices in future.

Changing practices toward sufficiency requires practitioners to reflect on specific questions. The findings of this study encourage business practitioners to ask specific questions for the development and orientation of their strategies and practices, for example, concerning basic human needs and needs satisfiers (What are basic human needs? Which product, services, or practice elements are essential to serve these needs?), the created value (What sufficiency-oriented value can be co-created and co-delivered?), or the growth and diffusion of sufficiency-oriented practices (How much growth is enough? How do we spread and diffuse sufficiency-oriented value and practices?). The transformation toward sufficiency-oriented businesses implies that all business processes and strategies need to strive for a state of enough. According to the findings of the study, practitioners willing to integrate sufficiency need to ask how much is enough and what is necessary for a good life before implementing any new products, services, strategies, or processes in the business. Similarly, Bocken et al. (2022) suggest seven core elements of a sufficiency-based circular economy with specific questions that guide businesses toward sufficiency. Their framework confirms the findings of this study by calling sufficiency practitioners to consider sufficiency in all business practices, for example, in their purpose, network, internal governance, or finances.