94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain., 07 July 2022

Sec. Sustainable Organizations

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2022.888406

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Role of the Human Dimension in Promoting Education for Sustainable Development at the Regional LevelView all 10 articles

In this text we are interested in the preconditions for, and opportunities provided by sustainable development at local level in non-metropolitan areas, i. e., in rural areas and villages. These areas are generally seen as having an important role in achieving sustainability. The literature review highlights the general principles of endogenous development with an emphasis on local resources including human potential and social capital, and the Czech context. In practice, the empowerment and cooperation of regional actors is crucial for the sustainable transition of rural areas; an analysis of the local situation was thus conducted from the perspective of social capital. Research primarily questioned the role of local actors in different areas related to sustainable development, their relationships and involvement in sustainability processes, as well as deficiencies in social conditions creating barriers to sustainable development. The research methods selected to answer these questions reflected the context-specific, scientifically-overlooked character of the theme of this research where emerging phenomena were at the center of our interest. A survey conducted with representatives of the National Network of Local Action Groups (LAGs) mapped the situation in 50 (out of 180) LAGs in the Czech Republic (28 % of the total number). Data were analyzed quantitatively (single and multiple-choice questions), in combination with qualitative methods which were used to transform and aggregate responses into conceptual categories which were monitored for frequency (to observe majority opinion). The diversity of local actors, their relationships and roles in the sustainable development processes was thus illustrated. A snapshot of actors' current involvement in specific areas of sustainable development was compared with their potential involvement in these areas illustrating the importance of social capital which is not always recognized in relevant policy documents. The engagement of these diverse actors in sustainability transition processes is less evident: in most of the categories of change, the role of public administration prevails. According to the respondents, these changes that would ensure a sustainable future of the regions are often not taking place. While some of these findings may be specific to geographically-defined regional conditions and the Czech historical context, the research raised theoretically relevant questions concerning the role of social capital in sustainability processes.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted by all UN member states in 2015 and in the following years they were elaborated into national development strategies at various levels [in the Czech Republic these are national and regional development strategies (Kárníková, 2017; Ministry of Regional Development, 2020)]. However, the general principles expressed in the SDGs cannot be applied universally. Sustainable development (SD) is context-specific and its implementation depends on the unique conditions in a given place or region, and the initiative of local people (Moallemi et al., 2019). Thus, while the general principles of the SDGs represent a common framework, regionally relevant strategies need to take into account local resources, unique opportunities and constraints, and be embedded in the specific local culture/s, etc. These local agendas are however still rather underexplored (Moallemi et al., 2020). In this text we will look at how the general objectives and principles of sustainable development are “translated” into concrete measures or activities that fit into a sustainability framework, using the regions of the Czech Republic as a case study. We are primarily interested in the social dimension of sustainability, which not only contributes in itself to the quality of the social environment and local life, but is often also a condition for success in achieving the objectives in other dimensions of sustainable development: economic and environmental. In search of local conditions that are favorable for the implementation of general SD strategies in this particular context, we thus concentrate on social aspects as one of the cross-cutting preconditions for sustainability. This perspective highlights the roles of different actors that are represented in this research by their associations—Local Action Groups (LAGs), a network of which covers most of the Czech Republic.

Sustainable development is still embedded in the framework of globalized economy (cf. Blažek and Uhlír~, 2020) which is not always compatible for development at regional level, mainly because in practice this approach generates “winners” and “losers” (Smejkal, 2008). This often results in inequalities between regions—the comparative advantages sought by the economy usually favor the centers (large cities and agglomerations), while using the periphery (mostly rural areas) as a kind of hinterland, which entails dependency and its associated risks (Rodríguez-Pose and Fitjar, 2013; Ženka et al., 2017). These regions are thus vulnerable and often assume the role of (potential) “losers” with all the negative consequences for future development, either in terms of limited opportunities to exploit economic conditions (which centers can do better) or by attempts to match centers at any cost, regardless of local conditions and the sustainability of their resources (cf. Horlings and Padt, 2013).

The strategic objectives of regional development must therefore be based on different assumptions than the criteria for success in a globalized economy—rooted instead on the principles of endogenous development (that relies on internal resources and driving forces, in contrast to exogenous development or neo-endogenous development that combines the advantages of both) (Delín, 2013). The aim is then to mobilize the internal potential of the region and thus contribute to the most efficient, and at the same time, most sustainable use of local resources. As there is a great diversity of conditions among regions, geographically-sensitive policies must take into account specific conditions and limits of the local environment and its resources, and should be embedded in the particular local culture, etc. (Hansen and Coenen, 2015). On the other hand, in rural areas there are also unique opportunities to substantially contribute to sustainability locally and globally, and for some of the SDGs these areas can be considered to be the main “provider” of, for example ecosystem services, which is the context of implementation of SDGs such as climate change, life on land. The role of rural areas is emphasized, for example, by the OECD (2020) in a study showing that at least 100 of the 169 sub-goals (of the 17 SDGs) cannot be met without a significant contribution from cities and regions. They play an important role in achieving SD and quality of life with regards to water management, transport, infrastructure, land use, drinking water, achieving energy efficiency, among others; its main potential contribution is in climate change mitigation (Bachtler and Downes, 2020). Rural areas can be seen as a “provider” of ecosystem services (including aesthetic and recreational services) and the stewards of a resilient environment that is essential for quality of life—globally and in the long term; however, this role is not sufficiently recognized (Sitas et al., 2014) and important actors at local level are still not aware of the responsibility this entails.

Rural areas play a role in all three dimensions of sustainable development; however, sustainability processes at local level [often associated with transition, cf. (Harrington, 2016)] could not be initiated without the awareness and efforts of local people, thus the social capital of the region plays an important role here. The interrelationships between actors, their communication patterns and dynamics, and institutional settings to support collaboration, which vary considerably across regions (and is thus difficult to generalize), is a perspective that has started attracting scholarly attention (Truffer et al., 2015) and has been taken as the focus of this research.

A major contribution of the 2030 Agenda and the concept of the 17 SDGs is the broad coverage of the social, economic and environmental aspects of development on a global scale, and at the same time the internal interconnectedness of the different SDGs in these areas (Elder and Olsen, 2019). On regional level the development goals and needs are usually set within all the three dimensions of sustainability—achieving economic prosperity, meeting social needs, improving the environment (Bagheri and Hjorth, 2007). Each of these dimensions encompasses not only the objectives but also the preconditions for development (the state of the economy, social relations and the state of the environment determine further development). The three dimensions of sustainable development (economic, social, environmental) should thus be mutually supportive (cf. Craps and Brugnach, 2021); according to Hosseini and Kaneko (2012), this principle can be fulfilled mainly at the national scale. In practice, none of these dimensions is usually emphasized above the others, because their importance is linked to different time scales: some are more important in the long term, others in the short term (cf. Purvis et al., 2019). However, the social dimension is highly valued in achieving sustainability as it is addressed by nine out of the seventeen SDGs.

An important factor in development is thus the social environment. In this context Putnam et al. (1993) defined social capital as “characteristics of social organization, such as trust, norms, and networks, that can improve the effectiveness of a society by facilitating coordinated action” (in Smejkal, 2008, p. 40). Social capital is especially important at local level: here it is embedded in the community, encompasses the relationships and communication patterns of actors, and is manifested in the way the community works together in practical activities and projects. As a specific factor influencing the development of rural communities, it is considered to be “soft infrastructure” necessary for local development (Demartini and Del Baldo, 2015). The results of long-term research show that “...aspects of socio-cultural nature are important for the success/failure of peripheries, for their stabilization and for the activation of endogenous resources for their further development” (Jančák et al., 2010, p. 208). According to these authors, social capital can be assessed on the basis of its three basic principles: commitment, trust and satisfaction with community life (ibid., p. 217).

In this regard, social capital is considered as one of the preconditions for development in two other areas—environmental and economic. For the achievement of environmental sustainability in a particular place or community, social relationships between actors and their commitment are beneficial or even essential: the state of the environment is influenced by the everyday activities of individuals and groups, and care for the environment is part of the culture in a given community (Chang, 2013). In terms of economic prosperity, social capital is necessary for building trust and, in certain circumstances, for increasing economic efficiency (Dasgupta and Serageldin, 2001). This is important mainly when the economy depends to a greater extent on local ties and collaboration. Social relations, communication patterns and institutional settings, which vary considerably from region to region, are then considered one of the most important aspects of sustainability in local contexts (Thierstein and Walser, 1999).

Although the different SDGs are interrelated in many ways (cf. Bautista-Puig et al., 2021), the social dimension of sustainability is the most neglected in practice (Cuthill, 2010). Social issues tend to be conceived in development strategies as a problem or an end in itself, to be addressed by measures “from above”, rather than as a means to achieve other goals (Chang, 2013). Also from a regional development point of view, social capital is usually undervalued compared to economic conditions (Boström, 2012). However, this is slowly changing and a new policy framework is starting to redefine the appropriate conditions and environment for sustainable processes at local level: OECD (2006), for example, challenges the basic assumptions and objectives of regional development and describes the need to shift toward endogenous principles. This led to the formulation of a new development framework harnessing the internal potential of rural areas (OECD, 2019), further complemented by a direct link to the Sustainable Development Goals, thereby leading to the formulation of a “new SDG paradigm” (OECD, 2020). In this concept, development goals are defined as the achievement of well-being and quality of life in terms of the SDGs, i.e., based on the 5 Ps: people, prosperity, planet, peace, partnerships. The tools for achieving this type of development include targeted investments in human and social capital, highlighting opportunities to involve all concerned actors, with civil society being a key actor in achieving sustainability (such as active citizens organizations) (OECD, 2020).

At local level, the “emancipation of regions” is thus based on using all their internal resources and potential, including the mobilization of actors, which is considered a change of perspective or even a new concept of rural space (OECD, 2006; Ward and Brown, 2009). These regions deal with many problems of a local nature and must also build capacity for resilience and sustainable care of environmental resources. To deal with these challenges, they need a great deal of autonomy to allow local actors to function as development drivers. This is determined by the social environment: Perlín (1999, p. 3) defines a rural settlement from a social perspective as one “where there are close social contacts between the individual inhabitants of the settlement, and there is long-term informal social control and participation”.

On the other hand, the role of technology is frequently discussed in the context of development: the OECD (2018) identified the driving forces of change in rural areas as being mainly technological in nature. Also the concept of Smart Cities for municipalities and regions is being criticized for its over-reliance on technology (Suartika and Cuthbert, 2020). This technological perspective is still applied in Czech strategies (Ministry of Regional Development, 2018), in spite of the evidence that systemic solutions of a technological nature may not have the expected impact if conditions for their implementation—in terms of human and social capital—are not favorable (Ženka et al., 2017). In rural areas and small villages in particular, the involvement of local people and their willingness to engage in the development processes is a key factor of success.

Increasing attention to endogenous development processes based on internal resources and regional potential (Ward and Brown, 2009) highlights the role of diverse locally-specific actors as one of its most important assumptions and drivers (cf. Zahradník and Dlouhá, 2016). In this context, OECD (2006) emphasized the role of all levels of government, local actors: public, private, non-governmental non-profit organizations (NGOs) and civil society associations, and also their cooperation across sectors. This development concept contrasts to the older model of top-down policy where, in general, the main driving forces are national governments and large farmers which supposedly ensure the region competitiveness (Horlings and Marsden, 2014).

The necessity to involve actors such as businesses and NGOs in the processes of change toward sustainability is widely discussed also by the academic community (Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016). In this regard, processes based on sustainable leadership (Horlings and Padt, 2013), and communication/coordination of joint planning and activities, where attention is given to the role of mediator between actors, are gaining importance and recognition. As a shift of perspective from government to governance is happening, Sedlacek and Gaube (2010, p. 121–122) stress the need for a more comprehensive transition where sustainability principles are increasingly embedded in all relevant institutions, while collaboration with internal/external actors is ongoing. According to these authors, a new type of rural development actor—the Local Action Group (LAG)—has taken on the role of coordinating and supporting this collaboration. The LAG, as a community of citizens, non-profit organizations, private business and public administration (municipalities, associations of municipalities and public authorities), is a regionally-based organization which is independent of political decision-making. One of the important roles of LAGs is to develop a balanced partnership between the main interest groups (municipalities, entrepreneurs, including farmers and the non-profit sector) with a clear set of rules for co-operation (so the LAGs are not a lobby or pressure structure for any rural interest group); on regional level, LAGs cooperate within a network (Binek et al., 2020). LAGs (and their partners) work together to develop rural areas, and administer financial support from EU and national programmes for their region. In the EU, the LAGS opened up opportunities for the strengthening of local and rural governance which is conditioned by the existence of informal networks, multi-level decision-making, and professionalization of bottom-up initiatives, among others. Logically, LAGs are seen as a catalyst for a transformation toward a new paradigm of rural development (Boukalova et al., 2016).

While the OECD (2020) has elaborated on the general territorial principles of SDG implementation from a social perspective, in this article we strive to document and analyse how these principles manifest in the specific context of rural development, using the example of the Czech Republic (CR). We concentrate on regions defined as areas with municipalities of up to 25,000 inhabitants where LAGs are active (NS MAS, 2021). The development of these areas is influenced by public administration institutions (state administration of municipalities, democratically elected councils), and their associations (for example the Union of Towns and Municipalities); there are also professional institutions (responsible for water, nature management, etc.) whose activities are subject to the relevant ministries. To initiate bottom-up processes at the level of municipalities and their rural hinterlands, a new actor in regional development—the Local Action Groups (LAGs)—has been assigned responsibility and provided with the LEADER method as a policy instrument. This method aims to involve partners at local level, including civil society and local economic actors, in the design and implementation of local integrated strategies that support development processes and potentially create conditions for transition to a more sustainable future in the territory and community (Lošt'ák and Hudečková, 2010; Svobodová, 2015). On this basis, territory-specific Strategies of Community-Led Local Development (SCLLDs) are developed, in the formulation and implementation of which the local actors, coordinated by the LAGs, play a role (Konečný et al., 2020). The concept of LAGs representing local partnerships between public, private and civic sector, and whose activities are based on the LEADER approach, is not unique for the Czech Republic—it is widely applied at EU level (Konečný, 2019). However, the specifics of individual countries shape development processes and in the Czech Republic, bottom-up initiatives are greatly influenced by national strategies that provide external stimuli for exogenous development processes (Konečný et al., 2021).

In general, it is primarily the policy of the EU that influences national development priorities in the Czech Republic. However, paradigmatic policy changes are introduced with a delay: the concept of territorial dimension was included in the Regional Development Strategy (RDS) for 2014–2021 (Ministry of Regional Development, 2013), but not fully recognized even by the more recently published Regional Development Strategy 21+ (Ministry of Regional Development, 2020). These strategies lack an emphasis on awareness of local conditions, including human and social capital, as a basis for regional development. What is still emphasized is instead the provision of social services and, above all, the elimination of disparities in territorial cohesion—which is assessed by demographic, economic, or infrastructure indicators (e.g., completed housing), without taking into account community aspects.

The Regional Development Strategy of the Czech Republic 21+ (Ministry of Regional Development, 2020) defines spatially differentiated economic, social and environmental objectives for the different categories of regions: metropolitan areas, agglomerations and regional centers, and it pays special attention to restructured regions and economically and socially vulnerable areas. Its narrative of development has, compared with the previous RDS 2014–2020, shifted toward endogenous development opportunities, local specifics and bottom-up activities. In some areas, for example landscape, this is more visible, in others it is less evident, e.g., in the field of local culture and education. The great potential of local communities with their unique social environment, and also local knowledge and experiences as a resource for learning, remain completely untapped (cf. Dlouhá et al., 2021a). When these strategies deal with bottom-up development processes, they do not take into account its main driving forces—the local actors.

Social capital on local and regional level in the Czech Republic has been explored by Sýkora (2017): the results of a large-scale questionnaire survey show that community activities and the existence of associations are an asset and development potential of all settlements irrespective of size, but are particularly significant for smallest settlements of up to 500 inhabitants. The importance of these community aspects (the relationships between local residents and their willingness to participate in the life of the town or village) for local development decreases as the population size of the settlement increases. In general, anonymity and lack of community life are problems typically attributed mainly to cities (Sýkora, 2017).

In this regard, the vast majority of 89 % of Czech towns and villages consider cooperation with neighboring towns and villages as a suitable tool to facilitate solving development goals and problems. The most important (from the perspective of the respondents of this research) themes of inter-municipal cooperation include maintaining good neighborly relations. There is a clear preference among municipalities for bottom-up, voluntary cooperation, using existing relationships and experience and emphasizing geographical proximity and similarity in size, rather than top-down cooperation. Municipalities associate this top-down cooperation with negative perceptions of state measures, the threat of increased administrative, time and financial burdens, as well as unfriendly relationships and mutual distrust. A certain skepticism toward cities is particularly evident in small municipalities which prefer to work with municipalities of a similar size rather than cities (Sýkora, 2017).

Identified future trends and challenges that will influence the development of settlements with a population of <15,000 in the next 20–30 years include, among others: strengthening local identity (the need for people to identify with their native regions, to belong somewhere); increasing public engagement of local people (dependent on the social capital of the settlement in question); and development of self-help and community initiatives and their support (Studnička, 2018). On the other hand, also supra-local (inter-municipal, micro-regional) cooperation should be considered as an increasingly important tool to address the problems of small municipalities and towns (Studnička, 2018). All these factors are very important for empowering people to contribute to local as well as global sustainability processes (Ober, 2015).

The categorization of regional development actors in the Czech context traditionally comprises three main groups: enterprises, households (individuals) and the public sector (state) (Ježek, 2014) while neglecting non-profit and civil society organizations. From this point of view, the main tools for territorial development are at the disposal of public administration and local government actors (Smejkal, 2008, p. 25) while educational institutions also play an essential role in the regional context. On the other hand, Perlín et al. (2010) emphasize relevant associations, mostly non-profit organizations and civic associations, and their activities in the local environment; Sýkora (2017) then show that community activities and the existence of associations are important especially for local development. The importance of these bottom-up initiatives has been documented in the context of environment and nature protection (Dlouhá and Zahradník, 2015).

In the Czech Republic, the role of supporting social capital (cooperation between actors within the region and beyond) as a necessary pre-requisite for joint envisioning, planning and realization of innovative projects, is unique for LAGs. It makes them one of the most important potential actors in a transformation that may (or may not) lead to a sustainable future. LAGs have only been operating since 2004, when the country joined an international network based on the LEADER method after the Czech Republic entered the EU. In 2020, LAGs were already operating across the Czech countryside (Binek et al., 2020); in 2021 they covered 93 % of the territory of CR with 60 % of its population (NS MAS, 2021). To fulfill their regional role, LAGs provide two main activities: (1) animation of local actors and (2) administrative tasks related to the management of the LAGs and implementation of CLLD strategies into operational programmes (Binek et al., 2020). The first of these roles is based on working with local actors to provide positive motivation, guidance and support in practical activities (projects); the second one sometimes implies the formal fulfillment of the requirements “from above”. The latter is prevalent in less proactive LAGs, which is partly explained by the historical legacy of socialist regimes of there being very little space for taking initiative at grassroots level (Svobodová, 2015; Boukalova et al., 2016). The freedom of local actors to choose their own development objectives is also limited due to the targeted support for the regional policy implementation (formulated at national level), which leads to the selection of applicants who are eligible for this support (Konečný et al., 2021). In the questionnaire responses, LAG managers, for example, spoke of the needs of NGOs, which can be difficult to support, although they are often an essential part of the local community. The inability to support associations and NGOs has led some LAGs to fear the loss of members from this “third” sector. As a result, some of the problems and needs identified in the SCLLD are not addressed in the territory, and the support for community life in rural areas is relatively low (Konečný et al., 2020).

This study was developed in the framework of a 3-year project of cooperation between universities and Local Action Groups; academics had the opportunity to cooperate with LAG representatives during the preparation and implementation of 4 semesters of training on various sustainable development themes. The research team received feedback from training participants (mostly LAG managers) regarding the relevance of the sustainable development themes for practice in local context. This relatively close collaboration is reflected in the nature of the presented action research and its results: important questions emerged during the collaboration. The training was disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic—most of the lectures were delivered online and interaction was also online. In the final phase of the second cycle of the training, a comprehensive survey was designed that reflected experiences from the interaction between lecturers (researchers) and LAG representatives, especially feedback concerning bottom-up processes and local actors as their main driving forces. Research questions included the following:

• What role do LAG representatives attribute to actors from different levels and sectors (individual, local or regional government, non-profit and private sectors) in different areas related to SD?

• How are these actors involved in the processes of sustainability transition/SDG implementation, i.e., in planning for the future and implementation of the changes needed?

• Which actors are currently missing but needed to achieve the SD goals at local level?

The research analyzed the contribution of the identified actors in the 3 dimensions of sustainable development (economic, social, environmental) which was complemented by the topics of education (from the perspective of lifelong learning) and citizen engagement (democratic dialogue). Based on the general research questions, a questionnaire was developed which focused on the following thematic areas:

• Possibilities and tools for sustainable development within the LAG,

• Role of actors in sustainable development of the region,

• Preconditions for the implementation of sustainable development objectives in the region, and

• Specific experiences from the LAG.

The sustainable development aspects of these themes were examined in terms of the actors' current involvement (who plays/does not play a role in the observed area) and with regard to the future outlook (who formulates new sustainable development goals in the region and who implements them, who initiates change and innovation—and who is missing in this respect). These thematic areas correspond to the objectives of the research—to map the possibilities/constraints of sustainable development at local level and its driving forces in terms of actors' engagement (and bottom-up processes initiated by them). As the full questionnaire was quite detailed, its full version and some of the results (relevant for different research questions) were published elsewhere (Dlouhá et al., 2021a; Vávra et al., 2022).

This online questionnaire was disseminated via email among all LAGs in the CR (the chairman of the National Network of LAGs used the database of contacts to disseminate the link). The respondents were mostly chairs or directors of Local Action Groups (12 persons), CLLD managers or project managers (51), administrative staff (6), and in one case a professional consultant. The questionnaire combined closed questions (analyzed with quantitative methods) and open questions (that allowed for a qualitative approach and interpretations). All 180 local action groups were invited to complete this online questionnaire, and full responses were obtained from 50 LAGs (28 % of LAGs). In this set, LAGs of different sizes from all regions of the Czech Republic were represented, including those participating in the project training. Given that the answers of the respondents are based on detailed knowledge of the local situation (LAGs' unique know-how), we can consider the answers to provide a solid basis for mapping the surveyed issue.

The perception of different actors by LAG representatives was analyzed, focusing on their roles that are relevant to the local conditions, and how they can be supported in this unique context. The perceived roles and relationships of both top-down actors and (mainly) local actors responsible for bottom-up processes was highlighted. The quantitative part of the research (single and multiple choice questions) focused on mapping sustainable development at local level: the obtained results illustrate changes toward sustainability, and roles/relationships of local/regional actors. To map their (fulfilled or unfulfilled) potential to contribute to development in different areas of sustainability, a multiple choice matrix was developed (the respondents ticked the box relevant for the actor and the area of contribution). Open ended questions were used to capture spontaneous responses and to catch the views of respondents in their own words. They provide rich information about experiences on the ground and uncover the conditions for sustainable development and SDG implementation from a local (bottom-up) perspective. With open ended questions we analyzed the variety of actors and their influence on pre-determined categories of transition processes. Open ended questions were also used to provide space for comments and reflection of unique experiences which then served as a context for interpretation of results.

Due to the complexity of the questionnaire, all questions were optional; the number of responses to individual questions thus varied. The multiple-choice questions were analyzed quantitatively in absolute numbers of responses rather than percent (those that were completed were considered) with attention to variability and diversity of responses. To increase reliability, consistency between quantitative and qualitative, open-ended, questions was ascertained (concretely in case of mentioned actors with specific roles in different sustainability areas). The research proved to be consistent with respect to similar content and frequency of categories in both types of questions.

Responses to the open-ended questions were usually analyzed with respect to unique insights and experiences. Some of these responses were however transformed and aggregated into conceptual categories for which frequency was monitored (to observe majority opinion). The categories were “data-driven”, they were constructed based on the words and text analyzed. The process of coding was constantly adapted to research objectives and the theoretical background of the research. The data from open questions were used for triangulation and validation of quantitative data.

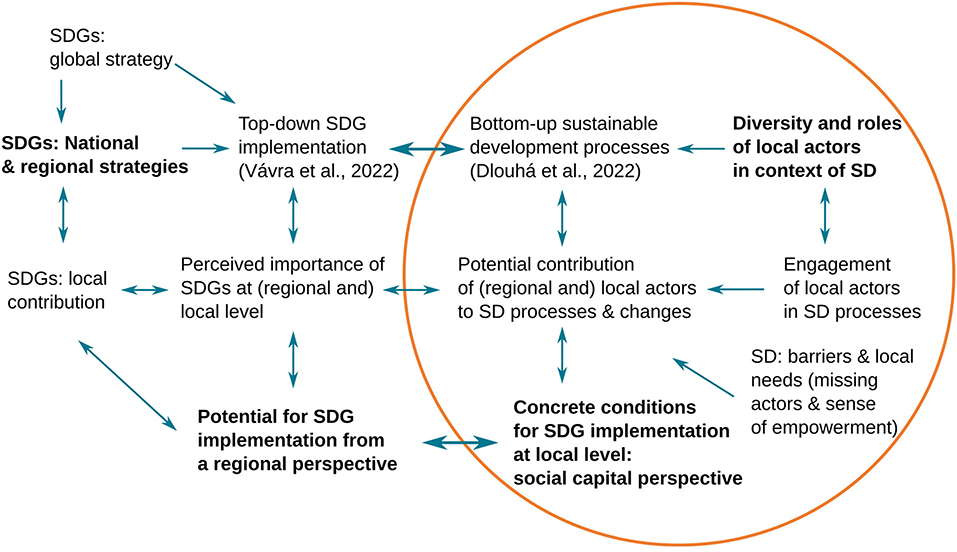

In general, this research explored the conditions for sustainable development at the local level from the bottom-up perspective, paying special attention to local actors. There is complementary research (Vávra et al., 2022), which looks at top-down strategies and their impact at local level where the SDGs are the main focus. This work used the same questionnaire, and also same respondents—employees of the Local Action Groups that were assigned to represent their LAG—answered the questions. For comparison of research objectives in the articles (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Complementarity of research objectives in the two articles of this special collection: this one (in a circle) and Vávra et al. (2022).

Data analysis showed the relationships of the various local actors and their roles as a driving force for sustainable development at local level, and illustrated the social environment in which these actors operate. To provide a comprehensive picture of how the sustainability processes are shaped by the social capital within this regional and local context, we cite other parts of the research (Vávra et al., 2022) while the specific role of education in actors' empowerment that is a pre-requisite of changes toward sustainability has been discussed in the national context (Dlouhá et al., 2021a).

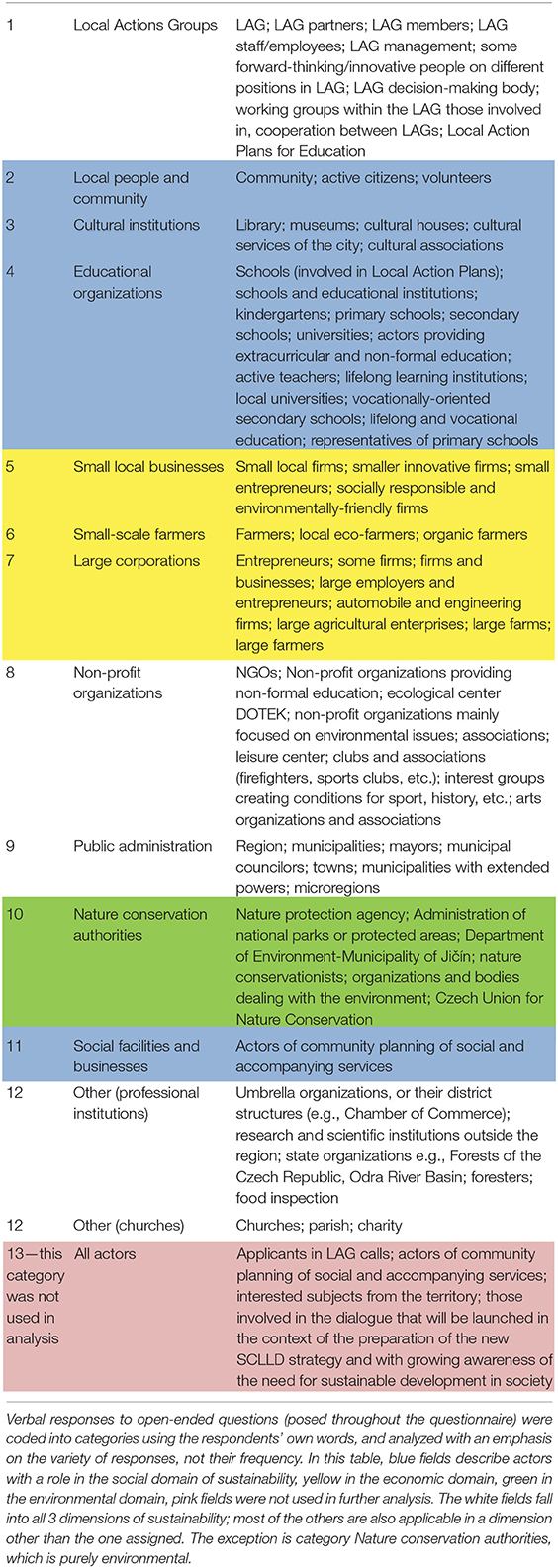

Analysis of verbal responses to open-ended questions confirmed that all mentioned actors fall into the categories established through theoretically-based coding (see Table 1).

Table 1. Definition of actor categories (theoretically based coding) and the summary of responses from open-ended questions.

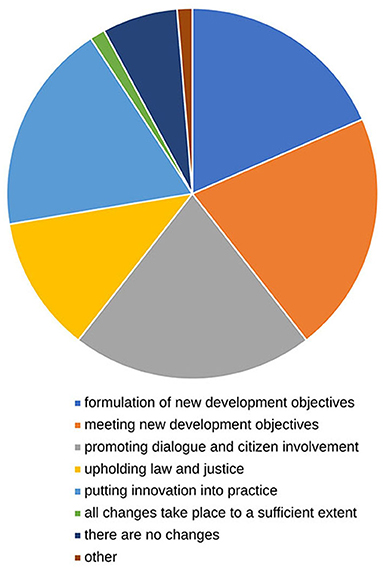

The LAGs' representatives feel that most of the changes toward sustainability needed at the local level are NOT taking place to a sufficient extent—illustrated by Figure 2.

Figure 2. Categories of changes that are NOT taking place in the field of sustainability, n = 46. Answers to the multiple-choice question “Tick which changes to sustainability in your LAG are NOT happening on a sufficient scale, and list the actors that YOU would need to help kick-start them”.

In respondents' opinions, several categories of changes are not taking place (only 1 of the respondents thinks that all changes are taking place and 5 of the respondents think that no changes are taking place at all). The reasons why these changes are difficult to initiate include lack of funding (too narrowly-defined support through the LAGs), insufficient human resources, and the low authority of LAGs in decision-making (due to shortcomings in legislation). The barriers that prevent LAGs from being leaders in sustainable development are discussed in detail by Vávra et al. (2022).

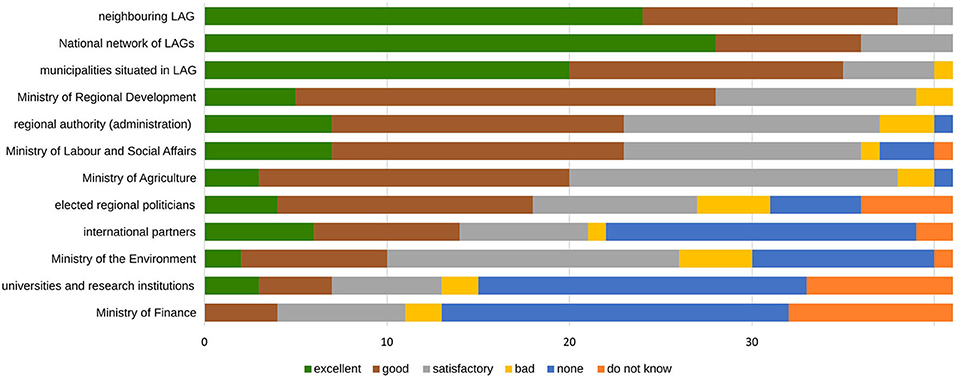

Supporting cooperation with actors at local, regional and national levels is an important part of the LAGs' activities. Figure 3 illustrates how the quality of cooperation with various actors was perceived by the LAGs' representatives.

Figure 3. Extent of the LAGs' cooperation with other actors, n = 41. Answers to the multiple-choice question “How do you evaluate cooperation of your LAG with various actors of public administration and external institutions?”.

The top group of most intensely cooperating actors consists of neighboring LAGs, the National Network of LAGs, and local municipalities—more than 80 % of respondents evaluated this cooperation as excellent or good. On the other hand, cooperation with supra-regional entities is significantly lower; bad cooperation is rare but no cooperation is often mentioned in relation to the Ministry of Finance (this institution was included in the survey as a hypothetically important actor). From this perspective, it is worth noting the weak or absent cooperation with universities and research organizations which in general are an important driving force for sustainable development (cf. Dlouhá and Zahradník, 2015).

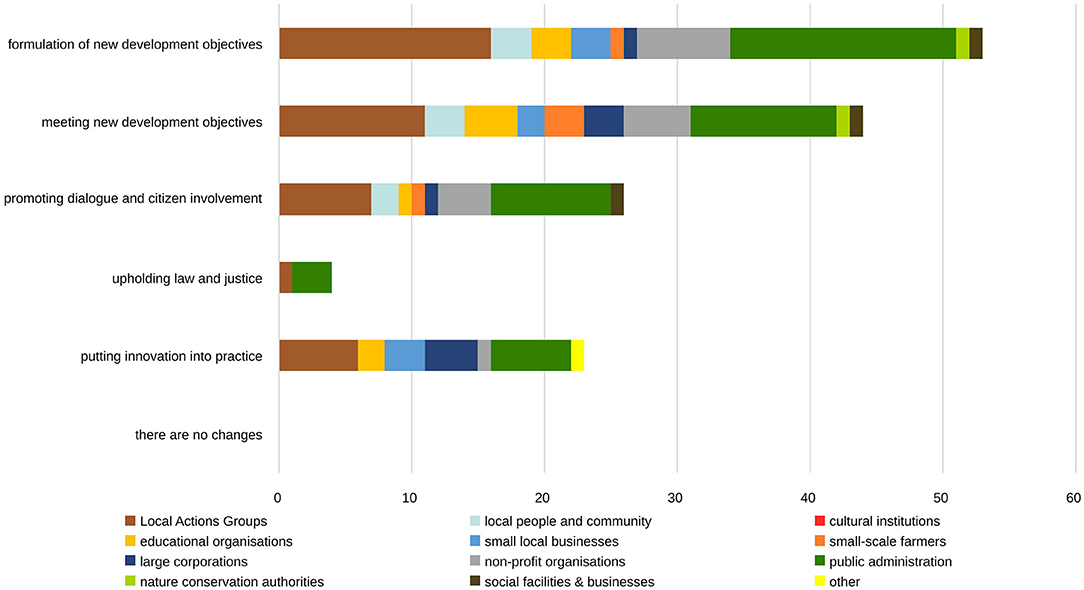

The previous conclusion (that LAGs cooperate mainly with local actors) is related to the following observation about the diversity of local actors (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Which actors are involved in changes toward sustainability, n = 45. Answers to the open-ended question: Which actors are at the PRESENT TIME helping to START a discussion on sustainability in your LAG on the following topics? Actors mentioned by the respondents in open ended responses were consequently assigned into the categories of actors developed through theoretically-based coding.

This question aimed to identify local actors and their role in the processes of change toward sustainability. It is evident that there is a diverse range of actors involved in LAGs around changes toward sustainability; a number of actors are involved especially in the formulation of development goals and their implementation.

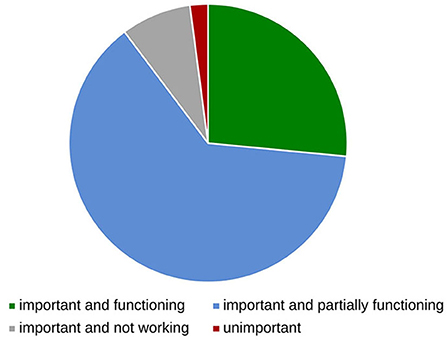

The social capital of a given region can be assessed according to the relationships between actors (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Relationships between actors and their importance, n = 41. Answers to the multiple-choice question: How do you perceive the RELATIONSHIPS between the different actors in your LAG and their IMPORTANCE for sustainable development.

As responses to this question show, LAG representatives mention excellent or good cooperation between all actors in almost 90 % of cases; actors that are lacking in terms of cooperation include the education sector (especially universities) and scientific and research institutions. The most frequently mentioned missing actor in terms of cooperation is entrepreneurs, both small (3 respondents out of 41) and especially large (6 respondents). Powerful employers and large companies may even influence relationships adversely (3 respondents).

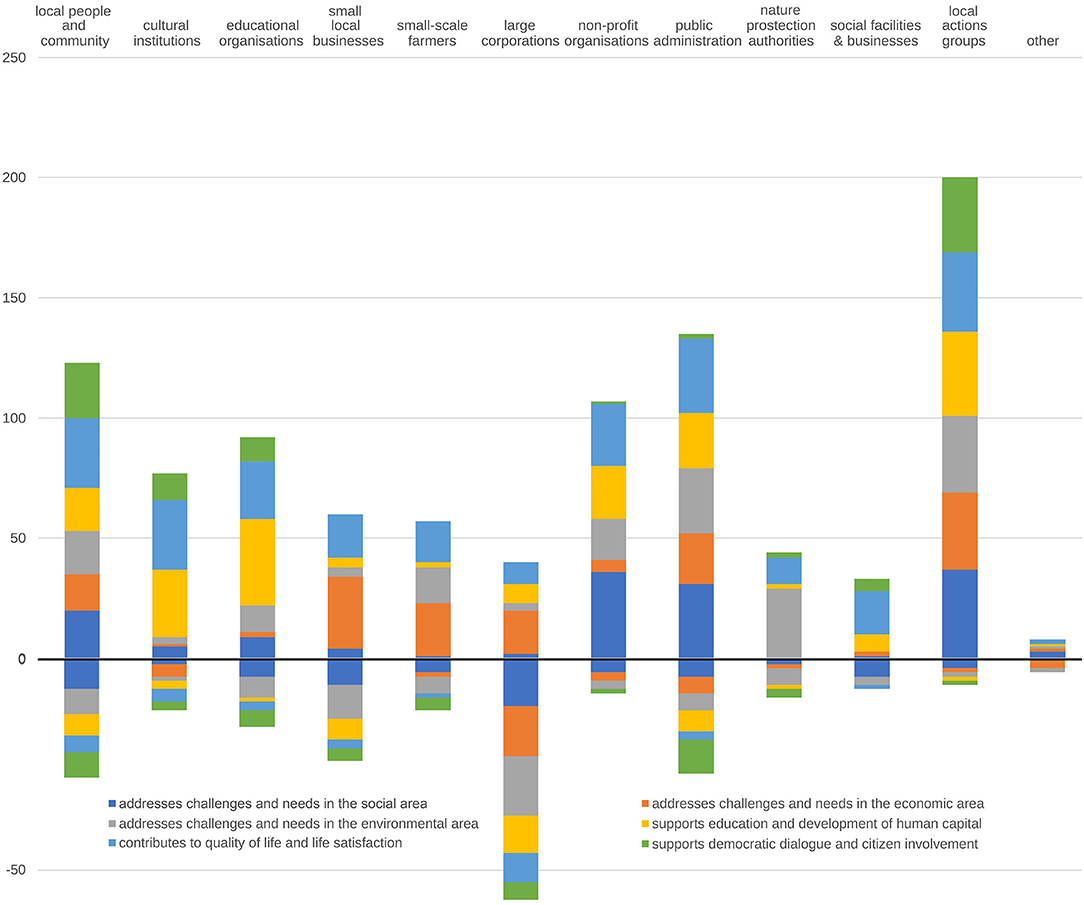

Which actors do, and which do not, play a role in the areas of sustainability is illustrated in Figure 6. Here, the answers to the two questions are compared so that for each actor both the actual perceived contribution to change in the region, and their absence, can be seen. The level of current involvement of the actors, and the unfulfilled potential in this area (from the respondents' perspective) can be ascertained from this comparison.

Figure 6. The extent to which LAG representatives consider that selected actors are currently involved in addressing challenges and needs in the areas of sustainable development (in positive values)—compared to the extent to which LAG representatives consider that the same actors are NOT—but should be—currently involved in addressing the same challenges (in negative values). Here the answers to the two related multiple-choice questions were compared: Who IS CURRENTLY involved in your region in the following... and the next: Who is NOT—BUT SHOULD BE—involved in your region in the following... These questions were answered by ticking a box within the matrix—relevant for the actor and the category of engagement.

The Local Action Groups feel competent to address the challenges of sustainable development; only a very limited number of their representatives feel that they are not sufficiently involved in addressing these challenges. On the other hand (according to these responses) the commercial sector does not contribute much to sustainability (beyond its economic objectives) but the large commercial companies should make a significant contribution in all areas of SD. The (perceived) importance of the civic sector (local people and community, NGOs), as well as cultural institutions and schools is evident.

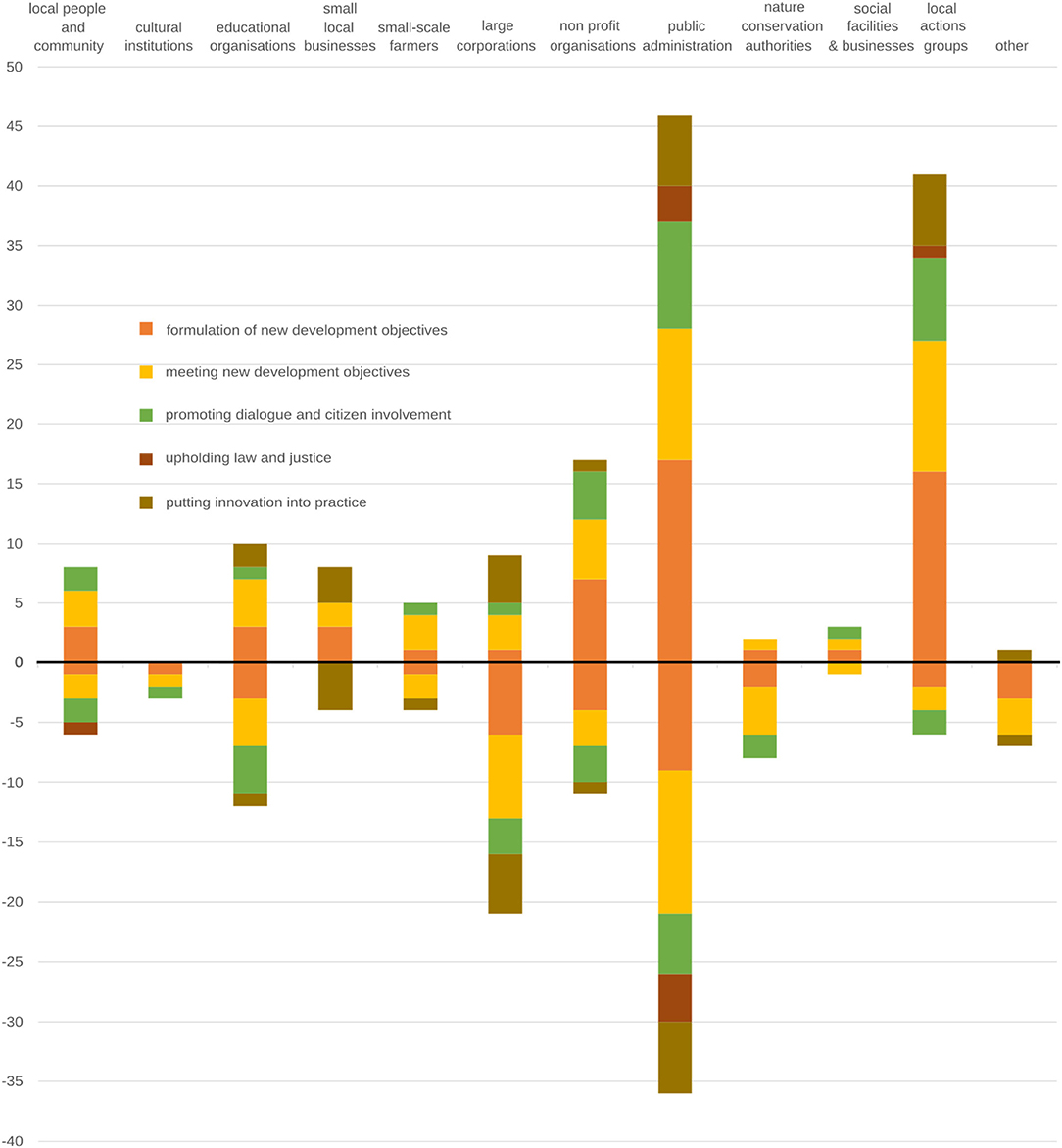

The future perspective of sustainable development—who formulates new sustainable development goals in the region and who implements them, who initiates change and innovation, and who is missing in this respect—is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7. To what extent do LAG representatives believe that selected actors are currently helping to initiate the sustainability changes in the following fields (the part of the graph with positive values), and for which changes toward sustainability that are not taking place to a sufficient extent would they need actors to help initiate them (the part of the graph with negative values). Here the answers to the following questions were compared: Which actors are CURRENTLY helping to START a discussion on sustainability in your LAG on the following topics? Which changes toward sustainability are NOT happening in your LAG to a sufficient extent, and list the actors you WOULD need to get them started. The questions were multiple choice (topics) with an open ended component (description of actors).

The most proactive actor in formulating and implementing new sustainable objectives in the region is reported to be public administration even though this actor still has great potential to be involved in sustainability (the negative part of the graph—below zero). This is the case also for the LAGs themselves (but with a considerably smaller potential of further involvement). The democratic actors may be influential if cooperating together: non-profit organizations plus local people and community, who can be supported by educational institutions. Large commercial companies are perceived as an actor with power which is however not sufficiently used in the public interest despite having relatively large potential in this regard. The role of cultural institutions is perceived as politically passive, not providing new impulses for development.

In terms of how the SDGs can be promoted at local level, LAGs generally understand the importance of the SDG concept; however, there are only a few goals to which they can make a meaningful contribution (cf. Vávra et al., 2022). In general, LAGs can contribute most in the social area, including the economy, where immediate results can be expected. By contrast, their action in the environmental field, especially as regards climate change, has yet to be seen. At the same time, LAG representatives are fully aware of their current and potential role in their local context (see Figures 6, 7) but the opportunities to make substantial impacts on different areas of sustainability are not always straightforward (the obstacles to fulfilling this role were mentioned in the open-ended questions). To fulfill their role in the local context—improving the well-being of individuals within the community, and to support, inspire and coordinate its members—LAGs deliver necessary know-how through education: in this field, their perceived contribution is most significant, as illustrated also by Dlouhá et al. (2021a).

The paper presented a reflection on the preconditions for the implementation of the SDGs at local level, focusing on the nature and roles of the different actors as one of the starting points of sustainability processes from the perspective of LAG representatives. The social conditions of sustainable development mentioned in the relevant documents (OECD, 2019, 2020) have been somewhat neglected in the literature (Cuthill, 2010; Chang, 2013) and are only recently starting to gain attention (Binek et al., 2020)—often following the implementation of the LEADER method in practice and LAGs' subsequent activities.

The analysis showed that a broad range of actors play a role at local level in the different areas of sustainable development. Some of the actors that are usually emphasized from an economic perspective of development (Binek et al., 2009; Ježek, 2014) are of marginal importance in terms of sustainable development at local level. The actors influencing top-down decision-making were considered by the respondents of the survey as less important than those entering processes from below; collaboration with the latter is more intense, as Figure 3 shows. From the bottom-up development point of view, the LAGs were considered to be the most important actors—their role is to empower other local actors and create a supportive environment for their activities. This role is relevant for the strategies of regional emancipation expressed in the “new SDG paradigm” of regional development (OECD, 2020).

The specificities of the endogenous development in the regions that emancipate themselves from the demands of the global economy (OECD, 2006; Ward and Brown, 2009) are illustrated by the perception of large corporations, which, according to the respondents, do not contribute significantly to any of the sustainability domains (and are rated the lowest with regards to contribution to quality of life and democratic dialogue). Even in the economic area, their contribution is average, with other economic players (small local firms and small farmers), and public administration (including the LAGs) making a greater contribution (Figure 6). As the answers to open ended questions also documented, the integration of large corporations into the local context may be highly problematic. On the other hand, large corporations (as perceived by respondents) are the first among those who currently do not but should participate in local development in all areas of SD and initiate necessary changes (Figure 7). This suggests that in the new SDG paradigm, the roles of actors need to be redefined with respect to their influence on sustainability issues (Elder and Olsen, 2019). As sustainability issues are interconnected [as are SDGs in similar ways, see Bagheri and Hjorth (2007)], inter-sectoral approaches (resulting from transdiciplinarity) will require institutional changes at different levels (Sedlacek and Gaube, 2010) within the framework of more substantial policy change at regional level (Bachtler and Downes, 2020).

In line with the integrative approach to sustainability (Bautista-Puig et al., 2021), the disadvantages of over-specialization of actors to only one area of sustainability are obvious; in the specific conditions of the Czech Republic, this can be illustrated by the role of nature conservation organizations, who are rarely involved in sustainability processes and their contribution almost exclusively in the area of nature protection is associated with low impact in other areas (Figure 7). As a result, there is a low level of dialogue on environmental problem-solving across society (cf. Brugnach and Ingram, 2012) and a generally poor awareness of how environmental objectives may be implemented across different dimensions of sustainability. The low perceived importance of environmental SDGs such as climate change by LAG representatives as documented by Vávra et al. (2022) is obvious, alongside the low empowerment of this actor in the environmental field (Figure 6). This is particularly alarming because rural areas are important actors in achieving the environmentally focused SDGs globally, being the major providers of ecosystem services. Without this awareness and empowerment, rural areas cannot play their crucial role in SDG implementation—delivering ecosystem services to the rest of the globe. Besides this role in the environmental dimension of sustainability, social capital is also necessary for building trust and thus increasing economic efficiency locally (Dasgupta and Serageldin, 2001).

What are the characteristics of the diverse actors' roles in the implementation of SDGs at local level? In the sustainability framework established by OECD (2020), the role of civil society received greater emphasis, as opposed to the commercial sphere. This may be characteristic of the Czech context, where businesses have not yet embraced the concept of social responsibility, but possibly also connected to the relatively low potential to promote change, including innovation (comparable to the potential of schools in this respect). As is apparent from the open-ended questions in the survey, when it comes to innovations supporting the green economy, local actors seem to be helpless. According to the respondents, there is not only a lack of active experts, research and development institutions, and consulting firms in the regions; the relevant education is also missing, with several respondents stating that “almost everything” is absent. Insufficient cooperation with universities and research institutions is confirmed by Figure 3. Thus, in terms of shaping the future, the most important actor seems to be currently the public administration (Figure 7). This finding could indicate deficient know-how and low empowerment of other local actors, resulting in their weak influence on decision-making and sustainability processes as such.

The role of local communities and NGOs in addressing current challenges in the CR is comparable to the influence of public administrations. This could suggest strong democratic participation in the regions, but also can be interpreted as a deficiency: numerous problems do not have systemic solutions and are left to the initiative of local citizens which sometimes leads to partial failures and wasted energy. The need to invest in a lot of voluntary work is also mentioned by the respondents as a negative experience of their involvement in LAG activities. In this regard, the representatives of the LAGs complain about the lack of financial and informational support, limited powers and burdensome administration. In the CR, spontaneous bottom-up processes are also often hampered by measures from above, evidence of which is provided by several authors (Svobodová, 2015; Konečný et al., 2021).

Given the perceived importance of the education sector (Dlouhá et al., 2021a), it should be analyzed in more detail (see Figure 6). Almost all actors play a role here, with less importance given to those from the commercial sector and, surprisingly, to nature protection authorities. Small, and particularly large enterprises are most frequently mentioned among those who should be more involved in delivering education to address the needs of the region, while local governments and cultural institutions should also promote “place-based” learning. The open-ended answers concerning the missing actors or systemic measures often indicate that among those significantly missing are “local universities, colleges, vocationally-oriented secondary schools; lifelong and vocational education...”. In some regions there is also “...a lack of support for environmental educational centers and other institutions and NGOs interested in education” or “...active NGOs that would focus on sustainable development issues”. It was mentioned here that local schools sometimes neglect or actually oppose the concept of sustainable development. LAGs have significant competence in the educational field (Smejkal, 2008; Lošt'ák and Hudečková, 2010) and feel that they can contribute here most (Figures 6, 7), but they need a strong actor responsible for education to cooperate with. In reality, not only important actors in education for the needs of the region are missing, but also the legal environment is systemically undervalued—which results in a deficient system of lifelong learning, and the absence of a valid strategy to create it (cf. Dlouhá et al., 2021b).

Not all desirable changes to sustainable development are ongoing to a sufficient degree (Figure 2). There is still some potential to mobilize the social capital of different regions (the negative values in Figures 6, 7), in terms of encouraging local actors and supporting their cooperation and relationships. Even if these relationships are already good or satisfactory (Figure 5), the open-ended questions uncovered some deficiencies. These are seen mainly in insufficient cooperation with local businesses, especially big agricultural companies and other large corporations. Some of the actors and local inhabitants have low commitment to contribute to the community; in this regard, it is the role of Local Action Groups to work with local actors, to empower and support these actors to achieve long term goals, including sustainability. The LAGs already have (from their point of view) the biggest role in addressing sustainable development challenges which might however be a subjective and biased assessment. The areas of sustainable development to which they feel they contribute the most are described by Vávra et al. (2022) and in Figure 7. However, even if the feeling that they can significantly contribute is subjective, it can lead to actions that make their intention a reality.

Prior to the research, close relationships were established with LAG representatives during the design and implementation phase of the training on SD which facilitated direct experience with the context of local development. The research was then conceived as action research and based on qualitative methods—analyzing responses by LAG representatives in the questionnaire, with a quantitative component serving to illustrate the conclusions. This approach facilitated the gradual materialization of a picture of the studied environment.

The sample of respondents included representatives of LAGs from only 28 % of these associations. The composition of the sample and willingness to answer was adversely affected by the situation of COVID-19. Respondents who completed the questionnaire worked carefully and provided much additional information even in open-ended questions; however, their views might be influenced by the way they cooperate with the actors in the region. LAGs usually deliver (a small amount of) financial support to small actors such as local enterprises and have little or no impact on big companies so their perception of this actor may be biased. Moreover, the individual actors and their roles are very diverse, and activities of LAGs in different regions also differ according to the local circumstances, so it is relatively difficult to generalize. However, as the research attempted to identify emergent phenomena (focusing on the diversity and regional specifics of sustainable development), and as the interpretation of the results was triangulated from the theoretical and practical point of view (comments obtained from LAG representatives), it can be said that the results give a fairly good indication of the overall situation in different regions of the country.

To increase data reliability, some questions were asked twice (in a modified form), and the results compared. Verification of the roles of actors in the areas of sustainable development (outcome from the analysis of data from multiple choice questions) was carried out with open ended questions concerning the role of actors in similar sustainability areas (theoretical based coding was used to identify categories of actors for quantitative analysis). The numbers of involved actors (a) ticked and (b) described by the respondents were relatively comparable in the case of positive involvement of the major actors; questions concerning the deficiency of actors had a slightly different focus and were not taken into account. This exercise resulted in the conclusion that the roles of actors and their involvement in sustainable development processes were assessed consistently by the respondents across the whole survey.

The factors of development on local and regional level can be seen as external (incentives, e.g., external subsidies, provided on the basis of top-down decisions) and internal (mobilization of internal resources and potential). These can be appropriately combined; in this article we have dealt mainly with internal (endogenous) factors of development. Top-down measures to promote SD include not only financial incentives and policy frameworks (targets and strategies), but also knowledge, innovation and technology transfer. However, if SD at local level is to take place with sustainable use of the resources and opportunities offered by the region, then these incentives must be appropriately applied in the local context where actors with different views and experiences defend their interests. The drivers of the necessary bottom-up processes are thus related to the social capital in a given place—the interrelationships between local actors and the ways in which they collaborate.

Research conducted through a survey with representatives of Local Action Groups as respondents explored social capital in the small towns and rural areas of the Czech Republic, focusing on the nature and roles of actors in sustainable development processes at local level. The views of LAG representatives were mapped, analyzed and interpreted in the context of a territorial approach to development (OECD, 2020). It became obvious that in the countryside (where LAGs operate), a wide range of actors and diverse contributions to SD (or, on the contrary, a noticeable lack of involvement) have to be taken into account. The actors acting “from above”, i.e., ministries and other governmental bodies, are often seen as an extraneous element, their actions often associated with a lack of understanding of the local situation and increased administrative burden, leading local actors to prefer cooperation with those working from a bottom-up approach. On the other hand, the local actors are the main driving force of sustainable development at the regional level. These actors to different extent address (or fail to address) challenges in social, economic, and environmental areas, contribute to quality of life, education and development of human capital, and promote democratic dialogue with citizen involvement. Their contribution to these sustainable development processes is far from being intuitively obvious: for example, almost all of the actors are perceived to be active in the field of education while only few of them support democratic dialogue. All of them also contribute to well-being while economic challenges are addressed less evenly (with the relatively limited contribution of large corporations). Even more surprising is their involvement in SD processes that shape the future—these actors formulate and meet new development objectives, promote citizens' involvement, uphold law and justice, and put innovation into practice to very different degrees. Most of these processes are initiated by public administration, including LAGs—and this actor is the only one who “uphold law and justice” to a certain extent (according to responses to one of the questions).

At regional level, it is difficult to promote a one-size-fits-all path to sustainability; instead, unique ways of meeting (broadly defined) goals need to be sought that are appropriate to specific local conditions. Too much reliance on uniform, pre-packaged solutions could lead to resignation of local initiatives, blind compliance with policies from above and adoption of ready-made e.g., technological solutions. Without the authentic participation of all local actors, substantial and long-term changes toward sustainability cannot happen. Conversely, development processes that are sensitive to the geographical and historical context may contribute to the formation of a unique local culture. Creating the conditions for cooperation and networking between actors must therefore take into account their diversity and anticipate their different (potential) contribution to the SDGs (which is often dependent on the recent history of the country/region as well as regionally specific current conditions, e.g., funding). The role of education that responds to local needs should be also reflected as it brings relevant expertise and awareness among local inhabitants in the field of sustainability. Here, the role of an actor who is dedicated to mapping local conditions, especially other actors, their interests and networks of cooperation, and who can translate general principles of sustainability into the local context, is indispensable. In the Czech Republic, this role is played by the National Network of Local Action Groups—the most important actor applying the LEADER method to stimulate desirable development processes from below. This actor is active, and the method is used in many other EU countries.

The SDGs undoubtedly changed the paradigm of development on regional and local levels, and this also concerns actors' roles and involvement. The perspective of actors and their social capital consistently promoted in this text may in turn transform understanding of sustainable development as such. On this level, social driving forces—an interplay of processes that are initiated by a variety of actors, with emphasis on social capital and character of social environment—are not only outcomes of development, but also its main preconditions. Accenting the social driving forces of development would shape local culture and support the well-being of local inhabitants, and deepen the commitment of the local actors to contribute on a larger scale. Attention paid to these social aspects of sustainable development thus may have a potential impact on practice; and as an emerging theme in research it is also relevant from theoretical point of view.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are available upon request.

JD: conceptualization of the research, literature review, design of methodology and formal analysis, and writing—original draft. JV: co-design of the methodology and the survey, analysis of data related to the top-down processes of sustainable development, and the role of SDGs. MP: co-design of methodology and the survey, qualitative and quantitative analysis of the data, and interpretation of the results. ZD: contribution to the literature review, comments to the methodology, testing of the survey in the pilot phase, and interpretation of the results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This work has received funding from the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic, the project TL02000012 Sustainable Development on Regional Level—Combination of Theory and Practice.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We would like to express our highest gratitude to Marek Hartych and Jiří Krist who have commented on the first version of the questionnaire and helped with its dissemination throughout the Local Action Groups in Czechia. Many thanks to the respondents—representatives of these LAGs in CR—for their insightful answers. We also want to thank to Jiří Dlouhý for his technical assistance, and Laura Henderson for the proof-reading of the text.

Avelino, F., and Wittmayer, J. M. (2016). Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: A multi-actor perspective. J. Environ. Policy Plann. 18, 628–649. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2015.1112259

Bachtler, J., and Downes, R. (2020). A Time of Policy Change: Reforming Regional Policy in Europe. European Policy Research Paper No. 113, University of Strathclyde Publishing. ISBN Number: 978-1-909522-72-5. Available online at: https://eprc-strath.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/EPRP-113.pdf (accessed October 20, 2021).

Bagheri, A., and Hjorth, P. (2007). Planning for sustainable development: A paradigm shift towards a process-based approach. Sustain Dev. 15, 83–96. doi: 10.1002/sd.310

Bautista-Puig, N., Aleixo, A. M., Leal, S., Azeiteiro, U., and Costas, R. (2021). Unveiling the research landscape of sustainable development goals and their inclusion in higher education institutions and research centers: major trends in 2000–2017. Front. Sustain. 2, 12. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.620743

Binek, J., Konečný, O., Šilhan, Z., Svobodová, H., and Chaloupková, M. (2020). Místní akční skupiny: Leaderi venkova? Brno: Mendelova univerzita v Brně.

Binek, J., Svobodová, H., Holeček, J., Galvasová, I., and Chabičovská, K. (2009). Synergie ve venkovském prostoru: Aktéri a nástroje rozvoje venkova. Brno: GaREP.

Blažek, J., and Uhlí D. (2020). Teorie regionálního rozvoje: Nástin, kritika, implikace. Charles University in Prague, Karolinum Press.

Boström, M. (2012). A missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustainability: introduction to the special issue. Sustainability: Science, practice and policy 8, 3–14. doi: 10.1080/15487733.2012.11908080

Boukalova, K., Kolarova, A., and Lostak, M. (2016). Tracing shift in Czech rural development paradigm (Reflections of Local Action Groups in the media). Agricult. Econ. 62, 149–159. doi: 10.17221/102/2015-AGRICECON

Brugnach, M., and Ingram, H. (2012). Ambiguity: the challenge of knowing and deciding together. Environ. Sci. Policy. 15, 60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2011.10.005

Chang, C. T. (2013). The disappearing sustainability triangle: community level considerations. Sustain. Sci. 8, 227–240. doi: 10.1007/s11625-013-0199-3

Craps, M., and Brugnach, M. (2021). Experiential learning of local relational tasks for global sustainable development by using a behavioral simulation. Front. Sustain. 57. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.694313

Cuthill, M. (2010). Strengthening the ‘social' in sustainable development: developing a conceptual framework for social sustainability in a rapid urban growth region in Australia. Sustain. Dev. 18, 362–373. doi: 10.1002/sd.397

Dasgupta, P., and Serageldin, I. (2001). Social Capital: A Multifaceted Perspective. World Bank Publications. Available online at: http://www.google.com/books?hl=enandlr=andid=6PZ8bvQQmxECandoi=fndandpg=PR9anddq=Social$+$capital:$+$A$+$multifaceted$+$perspectiveandots=EGmcziiKTeandsig=FAkaUx5nEKbpB8DZ7pIxBi_ioLE

Delín, M. (2013). Marketing lokálních identit: Prípadová studie komodifikace kultury a prírody místní akční skupinou. Masarykova univerzita Brno, Fakulta sociálních studií Katedra sociologie.

Demartini, P., and Del Baldo, M. (2015). Knowledge and social capital: Drivers for sustainable local growth. Chin. Bus. Rev. 14, 106–117. doi: 10.17265/1537-1506/2015.02.005

Dlouhá, J., Dvoráková Líšková, Z., and Ježková, V. (2021b). Lifelong learning for the development of people's knowledge and competences for local sustainable development. Envigogika. 16, 1–13. doi: 10.14712/18023061.633

Dlouhá, J., Pospíšilová, M., and Vávra, J. (2021a). Conditions for sustainable rural development—how to support transformation processes in practice? The role of local knowledge and lifelong learning in sustainable development processes of regions. Envigogika. 16, 1–39. doi: 10.14712/18023061.635

Dlouhá, J., and Zahradník, M. (2015). Potential for social learning in sustainable regional development: analysis of stakeholder interaction with a focus on the role of scientists. Envigogika. 10. ISSN 1802–3061. doi: 10.14712/18023061.476

Elder, M., and Olsen, S. H. (2019). The design of environmental priorities in the SDGs. Global Policy. 10, 70–82. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12596

Hansen, T., and Coenen, L. (2015). The geography of sustainability transitions: review, synthesis and reflections on an emergent research field. Environ. Innov. Societal Trans. 17, 92–109. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2014.11.001

Harrington, L. M. B. (2016). Sustainability theory and conceptual considerations: a review of key ideas for sustainability, and the rural context. Papers Appl. Geogr. 2, 365–382. doi: 10.1080/23754931.2016.1239222

Horlings, I., and Padt, F. (2013). Leadership for sustainable regional development in rural areas: Bridging personal and institutional aspects. Sustain. Develop. 21, 413–424. doi: 10.1002/sd.526

Horlings, L. G., and Marsden, T. K. (2014). Exploring the ‘New Rural Paradigm'in Europe: Eco-economic strategies as a counterforce to the global competitiveness agenda. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 21, 4–20. doi: 10.1177/0969776412441934

Hosseini, H. M., and Kaneko, S. (2012). Causality between pillars of sustainable development: Global stylized facts or regional phenomena? Ecol. Indicat. 14, 197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2011.07.005

Jančák, V., Chromý, P., Marada, M., Havlíček, T., and Vondráčková, P. (2010). Sociální kapitál jako faktor rozvoje periferních oblastí: Analýza vybraných sloŽek sociálního kapitálu v typově odlišných periferiích Ceska. Geografie. 115, 207–222. doi: 10.37040/geografie2010115020207

Ježek, J. (2014). Regionální rozvoj. Fakulta ekonomická, Západočeská univerzita v Plzni. ISBN 978-80-261-0462-9. Available online at: https://dspace5.zcu.cz/bitstream/11025/16467/1/Regionalni_rozvoj.pdf (accessed December 7, 2021).

Kárníková, A. (Ed.). (2017). Strategic Framework Czech Republic 2030. Prague: Office of the Government of the Czech Republic. Available online at: https://www.cr2030.cz/strategie/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/05/Strategic_Framework_CZ2030_graphic2.compressed.pdf (accessed November 14, 2021).

Konečný, O. (2019). The Leader approach across the European Union: one method of rural development, many forms of implementation. Sciendo. 11, 1–16. doi: 10.2478/euco-2019-0001

Konečný, O., Binek, J., and Svobodová, H. (2020). The Rise and Limits of Local Governance: LEADER/Community-Led Local Development in the Czech Republic. In Contemporary Trends in Local Governance (s. 173–193). Berlin: Springer.

Konečný, O., Šilhan, Z., Chaloupková, M., and Svobodová, H. (2021). Area-based approaches are losing the essence of local targeting: LEADER/CLLD in the Czech Republic. Eur. Plann. Stud. 29, 619–636. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2020.1764913

Lošt'ák, M., and Hudečková, H. (2010). Preliminary impacts of LEADER+ approach in the Czech Republic. Agricult. Econ. 56, 249–265. doi: 10.17221/27/2010-AGRICECON

Ministry of Regional Development (2020). Regional Development Strategy of the Czech Republic 2021+. Prague: Ministry of Regional Development. Online https://mmr.cz/cs/microsites/uzemni-dimenze/strategie-regionalniho-rozvoje-cr-2021 (accessed January 24, 2022).

Ministry of Regional Development (2013). Regional Development Strategy of the Czech Republic 2014–2020. Available online at: https://www.mmr.cz/cs/ministerstvo/regionalni-rozvoj/regionalni-politika/koncepce-a-strategie/strategie-regionalniho-rozvoje-cr-2014-2020-(1) (accessed January 21, 2022).

Ministry of Regional Development (2018). Methodology for the Preparation and Implementation of the Smart Cities Concept at the Level of Cities, Municipalities. Ministry for Regional Development of the Czech Republic, Regional Policy Department in cooperation with the EU Publicity Department. Available online at: https://mmr.cz/getmedia/f76636e0-88ad-40f9-8e27-cbb774ea7caf/Metodika_Smart_Cities.pdf.aspx?ext=.pdf (accessed December 14, 2021).

Moallemi, E. A., Malekpour, S., Hadjikakou, M., Raven, R., Szetey, K., Moghadam, M. M., et al. (2019). Local Agenda 2030 for sustainable development. Lancet Planet. Health. 3, e240–e241. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30087-7

Moallemi, E. A., Malekpour, S., Hadjikakou, M., Raven, R., Szetey, K., Ningrum, D., et al. (2020). Achieving the sustainable development goals requires transdisciplinary innovation at the local scale. One Earth. 3, 300–313. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2020.08.006

NS MAS (2021). Local Action Groups in the Czech Republic. Available online at: http://nsmascr.cz/en/ (accessed September 21, 2021).

Ober, M. (2015). Vulkanland case study: transformative regional development. Envigogika 10. doi: 10.14712/18023061.436

OECD (2006). The New Rural Paradigm. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online at: http://www.rederural.gov.pt/centro-de-recursos/send/17-politicas-da-ue/733-new-rural-policy-linking-up-for-growth (accessed January 11, 2022).

OECD (2018). Enhancing Rural Innovation. Proceedings of the 11th OECD Rural Development Conference. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/regional/11th-rural-development-conference.htm (accessed January 28, 2022).

OECD (2019). OECD regional Outlook 2019: Leveraging Megatrends for Cities and Rural Areas. Washington, D.C.: OECD Publishing.

OECD (2020). A Territorial Approach to the Sustainable Development Goals. In A territorial approach to the Sustainable Development Goals: Synthesis report. OECD Urban Policy Reviews. Washington, D.C.: OECD Publishing. Available online at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/ba1e177d-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/ba1e177d-en (accessed February 22, 2022).

Perlín, R., Kučerová, S., and Kučera, Z. (2010). Typologie venkovského prostoru Ceska. Geografie. 115, 161–187. doi: 10.37040/geografie2010115020161

Purvis, B., Mao, Y., and Robinson, D. (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustai. Sci. 14, 681–695. doi: 10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5

Putnam, R. D., Leonardi, R., and Nanetti, R. Y. (1993). Making Democracy Work. Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rodríguez-Pose, A., and Fitjar, R. D. (2013). Buzz, archipelago economies and the future of intermediate and peripheral areas in a spiky world. Eur. Plann. Stud. 21, 355–372. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.716246

Sedlacek, S., and Gaube, V. (2010). Regions on their way to sustainability: The role of institutions in fostering sustainable development at the regional level. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 12, 117–134. doi: 10.1007/s10668-008-9184-x

Sitas, N., Prozesky, H. E., Esler, K. J., and Reyers, B. (2014). Opportunities and challenges for mainstreaming ecosystem services in development planning: perspectives from a landscape level. Landscape Ecol. 29, 1315–1331. doi: 10.1007/s10980-013-9952-3

Smejkal, M. (2008). Aktéri, stimulační a regulační mechanismy regionálního rozvoje-príklad Pardubického kraje.

Studnička, P. (2018). Predikce budoucích v?zev sídel do 15000 obyvatel a foresight souvisejících trendu. Západočeská univerzita v Plzni, fakulta ekonomická.

Suartika, G. A. M., and Cuthbert, A. (2020). The sustainable imperative—smart cities, technology and development. Sustainability. 12, 8892. doi: 10.3390/su12218892

Svobodová, H. (2015). Do the Czech Local Action Groups Respect the LEADER Method? Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis. 63, 1769–1777. doi: 10.11118/actaun201563051769

Sýkora, L., Procházková, A. Kebza, M., Ignatyeva, E. (2017). Analýza potreb měst a obcí CR vyhodnocení dotazníkového šetrení. Výzkumná zpráva. Prírodovědecká fakulta UK. Available online at: https://www.smocr.cz/Shared/Clanky/6597/analyza-potreb-mest-a-obci-cr-synteticke-shrnuti.pdf (accessed July 2, 2021).

Thierstein, A., and Walser, M. (1999). “Sustainable Regional Development: Interplay of Topdown and Bottom-Up Approaches conference paper,” in 39th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: Regional Cohesion and Competitiveness in 21st Century Europe (Dublin).

Truffer, B., and Murphy, J. T., and Raven, R. (2015). The geography of sustainability transitions: Contours of an emerging theme. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 17, 63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2015.07.004

Vávra, J., Dlouhá, J., Pospíšilová, M., Pělucha, M., Šindelářová, I., Dvořáková Líšková, Z., et al. (2022). Local Action Groups and sustainable development agenda: Case study of regional perspectives from Czechia. Front Sustain. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2022.846658

Ward, N., and Brown, D. L. (2009). Placing the rural in regional development. Reg. Stud. 43, 1237–1244. doi: 10.1080/00343400903234696

Zahradník, M., and Dlouhá, J. (2016). Metodika analýzy aktéru (Actor analysis methodology). Certified by the Office of the Czech Government č.j. 9645/2016-OUR. Envigogika. 11. doi: 10.14712/18023061.527

Keywords: sustainable development, local actors, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), social capital, regional development, Local Action Groups (LAGs)

Citation: Dlouhá J, Vávra J, Pospíšilová M and Dvořáková Líšková Z (2022) Role of Actors in the Processes of Sustainable Development at Local Level—Experiences From the Czech Republic. Front. Sustain. 3:888406. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2022.888406

Received: 02 March 2022; Accepted: 27 May 2022;

Published: 07 July 2022.

Edited by:

Stavros Afionis, Cardiff University, United KingdomReviewed by: