- Department of Geography, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden

It has been argued that to achieve a genuinely sustainable society, our mode of being in the world needs to change. Understanding macro visions such as the desirable size of our economies remains essential, but concrete ways of being in the world which unite such aspects of our existence as the self, being with others (humans and non-humans) and being in and with nature deserve a much closer attention. Hence, I propose focusing our attention on being once again. But rather than contemplating being as an abstract philosophical category, this paper looks at being in the world in this dual sense: we are part of the cosmos, of the web of existence and at the same time we are in the world locally, in concrete places and locations characterized by particular cultural attributes, political-economic systems, climate and landscape. This nature of being applies to individual humans and human organizations. This paper focuses specifically on business as one type of organizations. I employ the concept of degrowth business, the philosophy of critical realism and humanistic geography as lenses to enhance and deepen our understanding of what it could mean and look like for a business to be in the world locally and more sustainably. To understand what it could mean and look like in reality, I offer a case of a firm from Northern Sweden specializing in vertical hydroponic agriculture.

Introduction

Our current mode of being in the world is unsustainable (Spash, 2015, 2017; Bonnedahl and Heikkurinen, 2019; Spash and Smith, 2019; Elhacham et al., 2020). It causes degradation on many levels. On a personal level, humans, beings inherently capable of love, creativity, freedom (Bhaskar, 2000, 2002, 2012) came to self-identify with material objects often mass produced in a capitalist economy and with their accumulation (Koch, 2012). On the level of societies, humans are objectified, treated as an abstract category of labor, as a factor of production (Bookchin, 1982). On the level of human-nature interactions, ecological degradation is evident and has been widely documented by scholars of limits to growth (Meadows et al., 1972, 2002; Daly, 1996) and scholars of planetary boundaries (Rockström et al., 2009; Steffen et al., 2015). Researchers coming from a variety of fields such as sustainable development1 (see e.g., Waas et al., 2011; Griggs et al., 2013), transition science (see e.g., Geels, 2002; Loorbach, 2007), business sustainability and corporate social responsibility (see e.g., Bocken and Short, 2016; Dyllick and Muff, 2016; Schönherr and Martinuzzi, 2019) contemplate how societies may undergo a transition toward a more sustainable mode of being in the world and what it entails for businesses and other organizations.

Amongst the researchers who work to respond to the unfolding crises are degrowth scholars, including economists (e.g., Bonnedahl and Heikkurinen, 2019), political economists (e.g., Buch-Hansen and Carstensen, 2021), sociologists (e.g., Koch, 2022) and geographers (e.g., Schmid, 2018). Their arguments are based on the necessity to honor the limits of the planet via de-growing our economies to a size that can be sustained in the long term (Daly, 1993). Degrowth proposes an explicit and urgent deviation from the pursuit of economic growth and instead focuses on harmonious and peaceful co-existence within humanity and between humanity and nature (Bonnedahl and Heikkurinen, 2019; Buch-Hansen, 2021). While fields such as transition science and corporate social responsibility are research fields, degrowth is at once a research field, a political project, and a social movement (Buch-Hansen, 2021). Originally, degrowth appeared to be more concerned with the macro visions and the issues of fitting human economies within the limits of the planet. However, more recently the microeconomic level has received more attention (Schmid, 2018; Nesterova, 2020a,b). An important defining feature of degrowth scholarship is its ongoing philosophical contemplation (see e.g., Heikkurinen, 2018; Buch-Hansen and Nesterova, 2021), applicable both to our scientific efforts (Buch-Hansen and Nesterova, 2021), to our mode of being (Heikkurinen, 2018) and business (Nesterova, 2021c). In this sense, the roots of degrowth compatible ideas go far back in time, to the eighteenth century idea of “sustainable use” by Hannß Carl von Carlowitz (Waas et al., 2011), the ninteenth century calls for simple living in harmony with nature (Thoreau, 2016) and as far back as to ancient China where similar thoughts were expressed (Mote, 1989; Laozi, 2001).

Explicitly inviting philosophy to participate in a dialogue which focuses on alternative ways of being and running our economies is useful as it opens spaces for more adventurous and reflective theorizing. Recently, the philosophy of critical realism was proposed as a (but importantly not “the”) suitable philosophy for degrowth (Buch-Hansen and Nesterova, 2021). Some of the grounds for such proposal are the following: a deep look into ontology (the nature of being), a humble and relativist epistemological position which is radically open to exploration and cooperation with other perspectives and sciences due to seeing any knowledge as subject to critique and improvement. The grounds also include a normative orientation toward a better mode of being, a theory of how change may unfold, a hopeful and positive view of human nature, an attempt to reconcile the “opposites” (such as mind and body, culture and nature). The proposal to put degrowth and critical realism in a dialogue goes back to Roy Bhaskar, the founder of critical realism, who advocated for degrowth (Bhaskar et al., 2012).

Bringing together degrowth and critical realism, and especially using critical realism to underlabour for degrowth research appears to be fruitful (see e.g., Nesterova, 2021a,c). One aspect of critical realism which is immediately applicable to theorizing a different way of being in the world is the four planes of social being (Bhaskar, 1993; Buch-Hansen and Nielsen, 2020). The four inter-related planes include the plane of embodied personality, human relations, human structures, and humans' transactions with nature (Bhaskar, 1993). This resonates with other philosophies, such as existentialism, which focus on being and inter-relationship of humans with our own selves and our natural and social environments (Heidegger, 2001). It also resonates with geographical approaches which encompass multiple scales and levels of reality, from the self to the cosmos. Humanistic geography (Tuan, 1974, 1976, 1998) is an example of this geographical approach. It is a branch of geography which, while being a geography (thus interested in the earth and places within its realm), focuses on human beings, our geographical knowledge, relationships to and with places, others (e.g., crowding vs. privacy), livelihood and economics, and religion (Tuan, 1976). This branch of geography is associated, most notably, with the works of Yi-Fu Tuan.

Being and change, apart from occurring on the four planes of social being, always occurs somewhere. In other words, there is a dual character of existence. On the one hand, humans are part of the cosmos (Bhaskar, 2000; Laozi, 2001; Tuan, 2013). On the other hand, we act from somewhere. It can be a location such as a city, a place such as an office or a home, a space, i.e., a unique and dynamic, always in becoming cultural, political-economic environment. The nature of this location, its unique constellation of culture, landscape, climate affects our possibilities and actions (Tuan, 1974). Thus, we are in the world locally and not only generally as parts of existence.

While attempting to understand the unfolding of being on various planes generally helps us deviate from reduction to any particular level, examples of being in the world locally are called for. Humans can be in concrete locations in different ways, as individuals and as communities of individuals, thus forming new social entities. In this paper I turn my attention to a common type of a social entity in need for ecological and social transformation, a firm, and a particular location, the North of Sweden. The firm I investigate specializes in vertical hydroponic agriculture. I use a case study method to capture the nuance and detail of the firm's existence (Flyvbjerg, 2006) and aim to view a firm in a different light with the help of the concept of degrowth business, critical realism, and humanistic geography. Seeking novel view on firms appears to be pertinent in the situation where much hope is placed on firms to participate in transformation toward a more sustainable mode of living.

I adopt a humanistic approach to firms by recognizing that a firm is a social entity, a community of humans (Lawson, 2015b). While a firm can also be seen in terms of structures (consider, for instance, hierarchies, departments, teams, rules, norms), seeing a firm in terms of human beings and their various interactions allow us to benefit from the existing knowledge from other fields and approaches such as a reflective, holistic and multi-dimensional approach of humanistic geography (Tuan, 1974, 1998, 2013). In its hopeful and positive approach to human nature (see Tuan, 2008), humanistic geography is not dissimilar from critical realism. Likewise, such an approach to human nature appears to be in line with degrowth theorizing: if change toward a better society is indeed possible, humans must be willing to participate in change, even if it entails stepping into the realm of the unknown and leaving behind what humans are used to.

This paper uses degrowth, the philosophy of critical realism and geography as lenses through which a different mode of being can be viewed. All of these fields share similarities yet allow us to learn something new and to understand how genuine sustainability can become possible. Inter-disciplinary dialogues are not unusual for any of these three bodies of knowledge. For instance, inter-disciplinarity is central to both degrowth and critical realism (Bhaskar et al., 2010; Buch-Hansen and Nielsen, 2020; Buch-Hansen and Nesterova, 2021). Geography itself is a field which uses knowledge from a wide variety of different disciplines (see e.g., Tuan (1974; 1998) use of psychology, anthropology, and other sciences in his investigations), including the philosophy of critical realism (Sayer, 2015).

The paper is organized as follows. The nature of a firm and its being are explored in Section Being of a Firm Toward Degrowth of this article in more detail. The third section focuses on methodology. The fourth section reports the findings and Section Discussion discusses the implications of thinking in terms of the three lenses of degrowth, critical realism and geography. The final section concludes.

Being of a Firm Toward Degrowth

In this section, to understand the being of a firm toward degrowth, three bodies of knowledge, including degrowth, critical realism and geography are employed to serve as lenses through which a firm can be viewed.

One prominent feature of degrowth theorizing is a deviation of societies away from capitalism (Buch-Hansen and Carstensen, 2021). From the degrowth perspective, firms may be seen as capitalist organizations, in contrast with a degrowth-compatible organization, where an organization is a form of some kind which is alternative to a firm. For example, it can be a cooperative. Against this perspective, it has been argued (Nesterova, 2021c) that a firm is a community of individuals (Lawson, 2015a), and a form of an organization, though may indeed influence the how of doing business, is less important than what it does and how. A cooperative can be hierarchical and may seek to expand (Gibson-Graham and Dombroski, 2020) while a firm can be non-hierarchical, it can be non-growing, it can strive to create a healthy space for work, human development, and learning. Moreover, both a firm and a cooperative existing within a capitalist system would be facing similar issues, for instance of access to funding. Hence, the how of doing business (by a cooperative or a firm) becomes more important than looking for an ideal form of production: many (and diverse) forms of production may be suitable for degrowth.

The “how” naturally provokes reflection on concrete practices. While many practices have been proposed by degrowth scholars (Hankammer et al., 2021), they generally relate to the three dimensions of a firm's existence (Nesterova, 2020a,b). These dimensions include (1) the environment, (2) humans and non-humans and (3) a deviation from the profit maximization imperative. The last dimension, deviation from the profit maximization imperative, is something which partly answers the criticism of those who argue in favor of eliminating a firm as an organizational form in favor of other forms of producing organization. If a firm as a community of humans does not strive to maximize profit, it opens space for creativity in terms of how to run a business, with whom, and what for. Why would humans strive for something other than profit and view business as a creative activity? The possibility of this different kind of striving as well as a creative approach can be assumed, in critical realism, due to humans' inherent capacities for love, creativity, imagination, freedom, intentionality, acting deliberately toward something better such as a better future (Bhaskar, 1998, 2002, 2012). Bhaskar (2000, p. ix) goes as far as to say that “the most appropriate (correct, best possible) ethical and political stance is one of unconditional love for our essential selves, and that of each and every other being and the environment we inhabit.” This is also something he believes can be manifested in reality. Such a positive and hopeful view of human nature is not dissimilar to that of humanistic geography which assumes human goodness (Tuan, 2008). It is of course important to note that human goodness for Tuan (2008) is not perfection, nor is it an overly romantic view of human nature. It should thus be differentiated from “inhuman goodness” (Tuan, 2008, p. 174) or sainthood.

Critical realism helps us understand a firm's being in terms of its relatedness with the world around it. At the core of a firm are human beings (Lawson, 2015a) who are not isolated but rather related and are part of the same community of life (Bhaskar, 2000). A firm itself can be seen as an agent in societies and economies whose agency derives from the agency of the humans involved (Nesterova, 2021b). In critical realist terms, agents reproduce and transform structures (Bhaskar, 1998; Buch-Hansen and Nielsen, 2020). Thus, change arises from agents transforming structures and reproducing those ones which are already compatible with a desired society. Social structures can be transformed because they are only relatively enduring (Bhaskar, 1989). The word “structure” may seem abstract. An example is called for. For example, norms are a type of structures. The attitude of exploitation toward nature has become one of the norms in industrialized societies (Næss, 2005, 2012, 2016; Bonnedahl and Heikkurinen, 2019). This is one of the structures in need of deep transformations. Note the notion of “every other being” rather than “every other human being” in Bhaskar's quote above: non-human beings have the same right for self-realization (Bhaskar, 2000; Næss, 2016).

Finally, the being of a firm unfolds somewhere. This makes geography helpful in understanding of the being of a firm more holistically (Nesterova, 2021c). Geography is a science which has a long history of disambiguating the meaning of “where”, describing the world and concrete location, places, and spaces within it. Bhaskar et al.(2012, p. 102) rightly notes: “we act from the only place we can act, actually ever act, that is here, right here and now, the time you are in—now.” Similarly to critical realism, geography emphasizes the context and various aspects of it in terms of the physical characteristics (such as the landscape and climate) and the human characteristics (such as the political, economic, cultural context). A firm, seen through the lens of geography, is part of the economic, political, cultural landscape and even part of the landscape in physical terms, as well as part of the cosmos or existence at large.

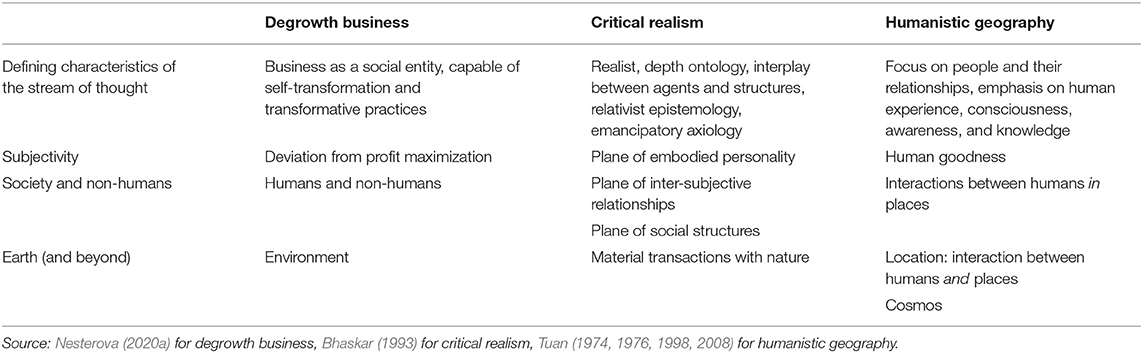

In this concluding paragraph as well as in Table 1. I summarize the three bodies of knowledge (degrowth business, critical realism, humanistic geography) and the key concepts which illuminate a firm's being toward degrowth. I relate these three bodies of knowledge across three broad domains of subjectivity, society and non-humans and the Earth (and beyond).

To bring about a degrowth society, firms need to participate in change and self-change. Self-change of firms includes deviating from profit maximization and operating in such a way which takes into account the firm's inseparability from humans, non-humans and the environment. Critical realism, in terms of the self, encourages adoption of a deeply ethical position (Bhaskar, 2000). In terms of human societies, it reminds us of the existence and importance of inter-subjective relationships and social structures which can constrain and empower. In terms of the environment, critical realism postulates that every aspect of our being involved material transactions with nature. Humanistic geography shares Bhaskar's positive attitude to humans. However, as a geography, it highlights the importance of a place. Interactions between humans, as well as between humans and nature, happen somewhere, in places. The notion of the environment becomes finer and more multi-dimensional. Humanistic geography reminds us that we make a place, and the place makes us. As a rather philosophical branch of geography, humanistic geography not only brings our attention to concrete locations but also the cosmos as the common domain of existence. Finally, while degrowth business may seem to be an entity, critical realism and humanistic geography point beyond being. They point at becoming, change. Similarly to how human societies and landscapes change throughout time and space, a degrowth business likewise transforms.

Methodology

Having theorized a firm with the help from critical realism and humanistic geography, it is essential to look into the real world. After all, from a critical realist perspective, theories should be useful for practice and for the transition to genuinely sustainable development in reality (Bhaskar et al., 2012). On this occasion, I turn my attention to my own location in the North of Sweden and a firm based in this location. Attentiveness to one's own location allows more intimate investigation and affords an in-depth case study. Since critical realism focuses more on ontology, epistemology, and axiology (Buch-Hansen and Nielsen, 2020), it allows much freedom in terms of methodology and methods, providing they honor critical realist ontology, epistemology, and axiology. A case study method, while often being critiqued for a lack of possibilities to generalize one's findings, is embraced by critical realists (Nesterova, 2020b). This is especially so because social entities are ever changing and always in becoming (Sayer, 2015). Thus speaking of regularities becomes challenging no matter which social entity or phenomenon one is interested in (see also Buch-Hansen and Nielsen, 2020), but a new space opens for investigating detail and nuance (Flyvbjerg, 2006) as well as for attentiveness to the context in which this social-entity-in-becoming is embedded (Bryman, 2012; Yin, 2014).

I begin by briefly outlining the scene in which the case firm is set. Sweden is a country which is characterized by industrialization and urbanization (Hägerstrand, 2012b). The north of Sweden has been described as harsh and remote (Lundmark, 2002). The northern part of Sweden is commonly known as Norrland. It covers approximately 60 percent of the total land area of Sweden, but only 13 percent of the total Swedish population live there, making it a sparsely populated area (Lundmark, 2002). The political-economic system in Sweden is that of capitalism, though the type of capitalism is coordinated (Buch-Hansen, 2014). This means that, in contrast to countries such as the UK and the US (liberal capitalism) and countries such as Japan, Italy (state-led capitalism), in Sweden trade unions play a significant role and redistribution is prominent (Buch-Hansen, 2014). Moreover, Koch(2012, p. 128) notes the following about the Nordics (Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Denmark): “in terms of sustainability and use of renewable energy sources they also outperform other Western countries.” Swedish landscape is something where the geographical dimension becomes prominent. As Arell (1993, p. 11) notes, “[t]he geographical dimension is evident in countries that stretch a long way from north to south in northern latitudes, like Sweden. Usually the snow still lies deep on the ground in the north when it is time for spring plowing on the southern plains.” In the north of Sweden, winters are long and cold, summers are short and mild. This has obvious implications for agriculture, and this is the industry where the case firm belongs to. The kind of agriculture the case firm performs is somewhat unusual. It can be described as vertical hydroponic agriculture.

The case firm was selected from a list of initiatives and enterprises that the unit for research support and collaboration at the university maintains. My interest was directed at initiatives and enterprises which could be broadly described as socially and ecologically “sustainable.” My decision to look specifically into this industry and this firm arises from acknowledging that food is a basic need, and this industry needs careful and continuous attention for this reason, including by degrowth scholars. All data was collected in the autumn of 2021 via two site visits, two interviews and ongoing conversations, note-taking, short surveys designed for this study and via utilizing online sources (such as the website of the case firm). The primary informant (PI) is one of the three owners-employees of the firm. However, during one of the site visits I had an opportunity to meet and converse with another owner-employee as well as with the owner-manager of a firm which delivers the goods of the case firm.

In my investigation, I focused on the following dimensions: (1) case firm's ecological practices and principles, (2) social practices and principles, (3) attitude to profit or other possible key pursuits, (4) experience of being in a particular location (the North of Sweden), (5) barriers case firm experiences (e.g., funding, other organizations, political-economic and social structures), (6) empowerment case firm experiences (e.g., helpful, beneficial, reassuring structures, events, people). My questions were based on these dimensions, but not restricted to them. For instance, investigating the case firm's owners' attitudes to profit led to (unexpected) conversations about spirituality and mindfulness. In this situation, the conversation assumed a non-structured path.

The six dimensions identified above arise from the recent literature on degrowth business (Nesterova, 2020a, 2021c). Dimensions one, two and three reflect directly the degrowth business framework. Awareness of social structures which critical realism encourages (Bhaskar, 1989, 1993, 1998) led to the necessity to include dimensions five and six. Dimension four is geographical. It was inspired by humanistic geography and the need to consider firms' relationships with places. During my investigation in relation to this dimension, my interest was in the firm's relationship to Sweden and in particular the North of Sweden, its climate, landscape, and the city where the firm is based as a place. The following section reports the findings across each of the six dimensions, with constraints and empowerment reported in one section to show the following duality of the firm's being: it is at once within constraining and within empowering structures.

Findings

Ecological Practices and Principles

In vertical hydroponic agriculture which the case firm practices, no soil is utilized. Plants are grown indoors, vertically, which allows many plants to be grown in a relatively small space. A computer regulates the delivery of nutrients, water, and (LED) light to the plants. The computer also ensures circularity of water use which allows to be more attentive to the amount of water being used by the firm. Overall, all activities of the case firm are aimed at minimizing the use of resources while deepening connection with others, including customers and other organizations. The case respondent notes: “Since our company is started from the perspective of future predictions on climate change and the Anthropocene's impact on food production, our way of growing food with less resourses, more locally and with new business models that can create a deeper relationship with end consumers or organizations selling food has the potential (in long term) to help biodiversity flourish and thrive and have a more circular local food production through the whole value chain.”(PI, interview). The PI's view points in the direction of awareness of ecological degradation and relationality, willingness to participate in change, to seek ways for such participation.

Social Practices and Principles

Being a small firm where the three owners are also the only employees opens spaces for choice: what to grow, what other business options to explore, who to work with. It is a creative process and a process of learning together, unrestricted by the decisions which may have come from the management if the firm was, for instance, a subsidiary. Much of this learning is done via doing, but also via interacting with others coming from various walks of life. The PI has not attended a university and they appreciate a variety of knowledges beyond scientific knowledge as well as questioning “everything” (PI, personal communication, Autumn 2021). The structure of the firm is non-hierarchical, there is no relationship of subordination, and the owners-employees are related. The firm is run by two brothers and one of these brothers' partners. This creates a safe environment to discuss ideas and explore ways in which available resources and ideas can be constellated.

Apart from ecological awareness mentioned above, individuals involved in the case firm see positive social outcomes which can arise from their activities. There is a “potential to result in a healthier way of living, more job opportunities tied to nature itself and hopefully change the way we see ourselves in this world as a connected part of the whole” (PI, interview). What stands out from this quote is a deep awareness of connectedness of everything within the world with everything else. This position is similar to the spiritual turn within the philosophy of critical realism which recognizes oneness of being (Bhaskar, 2000, 2012). This different way of seeing ourselves in this world appears to transcend business activities. For instance, during one of the conversations, the PI mentioned that they saw me as a “human being, not a scientist” (PI, personal communication, Autumn 2021).

Profit

While recognizing the embeddedness of the firm within the existing and powerful structures of capitalist economy, thus the need to make a profit, the PI notes that in their firm they “believe in using money to push the change since there is no way of doing it otherwise on a global scale” (PI, interview). The desire to make a difference via the case firm appears to be connected with a spiritual practice of the PI and the other owner-employees' attentiveness and support toward the PI's spiritual practice. This is in line with a finding made recently by the geographers Schmid and Taylor Aiken (2020). In my conversations with the PI, I noted their references to mindfulness, meditation, nature-connectedness, simple living, and spirituality in a broad sense, i.e., without referring to any particular spiritual tradition (see, e.g., Nelson, 2009). The PI noted their personal journey of growth which has a deep connection with the way they operate their business, communicate with others and nature, and the direction in which they want their business to go.

Being in the North of Sweden

The owners-employees of the case firm are acutely aware of their location. While the start of the business was indeed a more general passion for food and recognizing the importance to produce it locally, what followed was consideration of the “where.” While vegetables such as potatoes can indeed be grown in Northern Sweden outdoors during the summer season, growing herbs and lettuce in winter in Northern Sweden is not an option. Vertical hydroponic agriculture allows the case firm to grow lettuce and herbs throughout the year. This requires much energy. The energy bill is the second largest expenditure of the case firm after wages. This bill can be larger in those countries where energy is more expensive than in Sweden. And while Sweden produces and uses a large amount of renewable energy (Swedish Institute, 2021), renewable energy still requires material and energetic investment.

The case firm is aware of the geographical dimensions of their being and of adaptations that need to take place. For instance, the respondent expands on this in the following: “Looking at climate change in the southern part of Europe, the northern part of Europe has a great opportunity to grow food in the future. As it looks right now, the north will probably be an important location for food production for Europe in 100 years. We have space to grow and innovation driven cities to create opportunities for it. Someone needs to start the long-term goal for it. We have seen companies from, e.g., Spain moving to Sweden to grow food taking their knowledge and techniques with them. This indicates perhaps something important for the future.” (PI, interview).

Constraints and Empowerment

Both geography and the philosophy of critical realism recognize the context, the embeddedness of an individual and of social entities within political-economic, social, cultural structures. For instance, the case firm respondent notes the culture surrounding food consumption aimed at convenience rather than health and the ritual of food consumption. Other barriers include political barriers and what economic systems are orientated toward and what they remain ignorant about. This is captured in the following excerpt: “At first, being a small start-up in the food industry is very hard. It seems that many people know the importance of food but really don't connect to the real importance of it, e.g., health (physical and mental), the environmental impact and so on. This is a barrier since it takes long time to convince people about it with less time and money. Political views are related too since they guide how we look at buying local food in schools, hospitals and so on. Even funding trough regional bodies are very hard since pretty much nothing can be related to food production” (PI, interview).

Despite the existence of barriers, there are also structures which can be empowering, though not always or easily accessible. The case respondent notes that “[r]eassuring would be funding from funding ventures since it would directly make space for faster development and more people with the right knowledge and connections to the market. Without it, companies die even if both the people within it are working very hard and have all the skills to make it work” (PI, interview).

Interesting to note is empowerment, support and collaboration which arise when other businesses, which are likewise on the journey toward sustainability, work together. While studying this case I noticed the unusual means that the case firm uses for the purpose of delivery of their goods. The case firm works with another small, local enterprise run and operated by one individual. This individual uses an electric pod (a type of a vehicle) made in Sweden which they use for delivery, as a taxi, for tours around the local area. The pod has various messages written on it, including words such as tolerance, empathy, gratitude. The challenge with this method of delivery is such that the pod cannot be used when the temperature drops below minus 10 degrees Celsius. This yet again highlights the importance of paying closer attention to the climatic conditions of the local area. When the option of delivery is not available, customers can pick up their vegetables from a location at the local train station which is within a walking distance from the main site of the case firm. The second location also serves as an office for the case firm. The office is made largely from the local wood.

Empowerment likewise comes from the constellation of social structures available in locations. The location where the case firm is based has a large university, a “university of the North” (Lundmark, 2002, p. 34). It is a growing city with many opportunities for innovation and exploring alternatives. And while indeed every human is capable of creativity (Bhaskar, 2012), creativity may be more readily exercised where conditions are suitable and even encouraging.

Discussion

In the field of degrowth the need to seek profit while being on a journey toward a better world has been well documented (Schmid, 2018; Nesterova, 2020b). It is commonly seen as a constraint on the path of transformation of business. Understanding such dynamics and constraints is essential since agents exists within structures which are real and impose their effects (Harvey, 2002). Various capitalist structures are constraining since capitalism orientates the society toward the valorisation of capital (Gorz, 2012), not toward peaceful and harmonious co-existence between humanity and nature and within humanity. Even though the type of capitalism in Sweden, as noted above, is coordinated, and Sweden can be described in the words of Tuan (2008, p. 163) as a “mature democracy,” it remains a capitalist country. Critical realism maintains that dominant social and economic power structures suppress potentialities and possibilities (Norrie, 2010). And yet, these potentialities and possibilities manifest themselves in the pockets and niches of capitalism. They manifest themselves through the practices of individual humans, resulting in our societies and our economic system being reproduced and transformed, in an emergent manner, “through the sum total of our individual practices” (Lawson, 2019, p. 11). The society is at once the condition for our actions and also the outcome of our various actions and practices (Lawson, 2019). These practices are not directed at the narrow self-interest. Rather, they accommodate deep awareness of being in the world with others (Heidegger, 2001): other humans and non-humans. Thus, in the same capitalist society there are multiple dynamics at once. In this sense, the unfolding of degrowth practices in the case firm is truly a journey across the landscape of capitalism. This landscape is, however, not homogenous and, upon a closer look, not even universally capitalist. It is more similar to how Gibson-Graham (2006) and Gibson-Graham and Dombroski (2020) view capitalism: within the society there are constraining structures but also those which empower, there are capitalist practices and non-capitalist practices. The possibility to work with like-minded individuals, seek and execute ways to contribute to deep transformations are certainly empowering. Constraints such as the need to seek funding are likewise present, hence humans are at once free and un-free (Boss, 1988). Oftentimes, as is the case with the firm investigated, one foot may be in the capitalist economy while the other outside it (Boonstra and Joosse, 2013). Likewise, some aspects of a firm's being can be degrowth, while others are not. For instance, the case firm practices local food production, but does so via using high technology. Could it be a better option to instead grow potatoes outdoors in the summer season? Perhaps this would be more degrowth-compatible (e.g., less energy intensive), but it would also be limiting toward creativity of the owner-employees and exploration of options for a transformed world.

It remains interesting to see, when analyzing primary data, the desire for self-transformation, not only the transformation of the world around more generally. Various scholars in both philosophy (Bhaskar, 2002, 2012) and geography (Tuan, 2008) note the existence of human goodness, which can be seen, for instance, in doing good in situation when there is a choice, to do good or not to do it, to participate in change or not to participate in it. Multiple individuals involved in business appear to be seeking alternative and intentionally better modes of being. They explore a wide variety of pathways for self-growth, nurturing moral agency and even spirituality. Part of this spiritual journey is learning. The individuals I had an opportunity to interact with during this research mention learning often. What is striking is a widely held in society assumption that business can, or perhaps should, be taught at business schools. None of the individuals I interviewed and had conversations with during this research were graduates of business schools, some not even university graduates. The fact of unfolding ecological degradation is well-known. It should not be surprising when scholars propose that aiming to avoid collapse is the most preferable scenario for the future (Moriarty and Honnery, 2017). This is likewise something humans outside academia realize acutely. Gehlen (1988) notes that humans are future-orientated beings, thus the concern of business owners, and the concern of every other human being about the future is understandable. Thus, in terms of temporality, human considerations transcend the present moment and go far into the future.

Apart from temporality, I would like to touch on spatiality and what is more often associated with geography, in particular scales and locations with their own socio-economic structures, cultures, landscapes, and climate. It seems intuitively true that even though we are part of general existence, we are also in concrete locations from which we act. In relation to this, Hägerstrand(2012a, p. 132) notes that we “can learn more about the global, we can talk about global issues and we can (possibly) agree on global strategies for change. But it will be the many local actions dispersed across the landscape mantle that produce over time the desired global changes.” Transformation of structures (Bhaskar, 1989, 1998) concerns structures in locations, and agents who transform structures (Bhaskar, 2002; Lawson, 2007) are also in locations and places. This local scale needs to receive more attention when considering alternative futures such as degrowth. Degrowth focuses intensely on the forms on production, including proposing a wide variety of such forms. Those forms may include household and artisanal producers (Trainer and Alexander, 2019), small firms (Schumacher, 1993; Leonhardt et al., 2017; Trainer and Alexander, 2019), alternative business models (Leonhardt et al., 2017), social enterprises (Johanisova and Frankova, 2017). What remains essential is understanding how these forms of production can be and can produce in different locations, how place sensitivity can be manifested alongside the realization and honoring of being part of nature and the cosmos. In other words, how to be in the world and locally.

It is pertinent to return to the lenses through which a firm was viewed in the beginning of this paper. When investigating, and interacting with, firms which are on a transformative journey, it appears that the three dimensions of degrowth business (deviation from profit maximization, nature and non-humans and the environment) do not suffice. They do not sufficiently bring forward the complex and multi-dimensional nature of a firm's being, including its being toward degrowth. The lenses of critical realism and humanistic geography illuminate and bring forward the aspects which could otherwise be missed, such as inter-subjective relationships, structures, and intimate inter-relationships with places. A new approach to degrowth business may strive to incorporate and study: the (necessarily relational) self, human relationships (with and to other humans and non-humans), human structures, geography (being in nature and in places).

Conclusion

It is often assumed that capitalist society is a dire and bare landscape. Weil(2001, p. 129) notes, for instance, that “[c]apitalist society reduces everything to pounds, shillings and pence; the aspirations of the masses are also expressed chiefly in pounds, shillings and pence.” Such bare landscape can be compared with the flora in Norway which Næss (2016) described in detail. However, Næss (2016) does not describe it in negative terms. In fact, he admires it, studies its diversity, and derives philosophical reflections from interacting with it. Within the landscapes of capitalism, it likewise appears important to seek existing alternatives and to study their multi-dimensional being and becoming. The philosophy of critical realism does not let us forget about the key planes or levels of being and change. Humanistic geography encourages us to contemplate our relationships to, and with, both the cosmos at large and to places. It appears that to capture the complex nature of being, both in the world in general and in locations specifically, no single science suffices. In this paper I looked at a firm via the three lenses of the philosophy of critical realism, degrowth business and humanistic geography. Each of them, while looking at the same world or a phenomenon, illuminates something different. Combining the insights from each of these fields leads to the necessity, while studying firms and their deep transformation toward a better society, to be attentive to the human self, human relationships, human structures, places and nature beyond one's own location. Looking at a case from Northern Sweden points in the direction that a degrowth business is not an entity, but rather a process.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Recent dialogues on sustainable development appear to go hand in hand with many degrowth proposals. Initially, sustainable development was defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED, 1987, p. 43). After undergoing a long journey of (mis)interpretations, more recent discussions and definitions highlight the necessity to clarify the meaning of sustainable development as well as to clearly bring together the questions of needs and planetary limits (see Waas et al., 2011; Griggs et al., 2013). For instance, Griggs et al. (2013) propose the following new definition of sustainable development in the Anthropocene: “Development that meets the needs of the present while safeguarding Earth's life-support system, on which the welfare of current and future generations depends”.

References

Arell, N. (1993). “In the old days,” in Work and Leisure, ed. K. V. Abrahamsson. Stockholm: SNA Publishing.

Bhaskar, R. (1989). Reclaiming Reality: A Critical Introduction to Contemporary Philosophy. London: Verso.

Bhaskar, R. (1998). The Possibility of Naturalism: A Philosophical Critique of the Contemporary Human Sciences. 3rd ed. London: Routledge

Bhaskar, R. (2002). Meta-Reality: The Philosophy of Meta-Reality. Volume I: Creativity, Love and Freedom. London: Sage.

Bhaskar, R., Frank, C., Høyer, K.G., Næss, P., and Parker, J., (eds.). (2010). Interdisciplinarity and Climate Change: Transforming Knowledge and Practice for Our Global Future. London: Routledge.

Bhaskar, R., Høyer, K.G., and Næss, P., (eds.). (2012). Ecophilosophy in a World of Crisis: Critical Realism and the Nordic contributions. London: Routledge.

Bocken, N.M.P., and Short, S.W. (2016). Towards a sufficiency-driven business model: Experiences and opportunities. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 18, 41–61. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2015.07.010

Bonnedahl, K.J., and Heikkurinen, P. (2019). “The case for strong sustainability,” in Strongly Sustainable Societies: Organising Human Activities on a Hot and Full Earth, eds K. J. Bonnedahl and P. Heikkurinen (London: Routledge), 1–20.

Bookchin, M. (1982) The Ecology of Freedom: The Emergence and Dissolution of Hierarchy. Palo Alto: Cheshire Books.

Boonstra, W.J., and Joosse, S. (2013). The social dynamics of degrowth. Environ. Values 22, 171–189. doi: 10.3197/096327113X13581561725158

Boss, M. (1988). Recent considerations in daseinsanalysis. Human. Psychol. 16, 58–74. doi: 10.1080/08873267.1988.9976811

Buch-Hansen, H. (2014). Capitalist diversity and de-growth trajectories to steady-state economies. Ecol. Econ. 106, 167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.07.030

Buch-Hansen, H. (2021). Modvækst som paradigme, politisk projekt og bevægelse. Nyt fokus: Fra økonomisk vækst til bæredygtig udvikling. Available online at: http://www.nytfokus.nu/nummer-17/modvaekst-som-paradigme-politisk-projekt-og-bevaegelse/ (accessed December 05, 2021).

Buch-Hansen, H., and Carstensen, M.B. (2021). Paradigms and the political economy of ecopolitical projects: green growth and degrowth compared. Compet. Change. 25, 308–27. doi: 10.1177/1024529420987528

Buch-Hansen, H., and Nesterova, I. (2021). Towards a science of deep transformations: Initiating a dialogue between degrowth and critical realism. Ecol. Econ. 190, 107188. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107188

Daly, H. E. (1993). “Introduction to essays toward a steady-state economy,” in Valuing the Earth: Economics, Ecology, Ethics, eds H. E. Daly and K. N. Townsend (London: The MIT Press), 11–50.

Daly, H. E. (1996). Beyond Growth: The Economics of Sustainable Development. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Dyllick, T., and Muff, K. (2016). Clarifying the meaning of sustainable business: introducing a typology from business-as-usual to true business sustainability. Organ. Environ. 29, 156–174. doi: 10.1177/1086026615575176

Elhacham, E., Ben-Uri, L., Grozovski, J., Bar-On, Y. M., and Milo, R. (2020). Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass. Nature. 588:442–444. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-3010-5

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual. Inquiry 12, 219–245. doi: 10.1177/1077800405284363

Geels, F. W. (2002). Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: a multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 31, 1257–1274. doi: 10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00062-8

Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2006). The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It): A Feminist Critique of Political Economy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Gibson-Graham, J. K., and Dombroski, K. (2020). “Introduction to The Handbook of Diverse Economies: Inventory as Ethical Intervention,” in The Handbook of Diverse Economies, eds J. K. Gibson-Graham and K. Dombroski (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 1–24.

Griggs, D., Stafford-Smith, M., Gaffney, O., Rockström, J., Öhman, M.C., Shyamsundar, P., et al. (2013). Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature 495, 305–307. doi: 10.1038/495305a

Hägerstrand, T. (2012a). “Global and local,” in Ecophilosophy in a World of Crisis Critical Realism and the Nordic Contributions, eds. R. Bhaskar, K.G. Høyer and P. Næss (London: Routledge), 126–134.

Hägerstrand, T. (2012b). “On making sense of the human environment: the problem,” in Ecophilosophy in a World of Crisis Critical Realism and the Nordic Contributions, eds R. Bhaskar, K. G. Høyer and P. Næss (London: Routledge), 135–146.

Hankammer, S., Kleer, R., Mühl, L., and Euler, J. (2021). Principles for organizations striving for sustainable degrowth: framework development and application to four B Corps. J. Clean. Prod. 300, 126818. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126818

Harvey, D.L. (2002). Agency and community: a critical realist paradigm. J. Theory Social Behav. 32, 163–194. doi: 10.1111/1468-5914.00182

Heikkurinen, P. (2018). Degrowth by means of technology? A treatise for an ethos of releasement. J. Clean. Prod. 197, 1654–1665. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.07.070

Johanisova, N., and Frankova, E. (2017). “Eco-social enterprises,” in Routledge Handbook of Ecological Economics: Nature and Society, ed C. L. Spash (Abdingdon: Routledge), 507–516.

Koch, M. (2012). Capitalism and Climate Change: Theoretical Discussion, Historical Development and Policy Responses. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Koch, M. (2022). State-civil society relations in Gramsci, Poulantzas and Bourdieu: Strategic implications for the degrowth movement. Ecol. Econ. 193, 107275. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107275

Lawson, T. (2007). An orientation for a green economics? Int. J. Green Econ. 1, 250–267. doi: 10.1504/IJGE.2007.013058

Lawson, T. (2015b). The nature of the firm and peculiarities of the corporation. Cambridge J. Econ. 39, 1–32. doi: 10.1093/cje/beu046

Leonhardt, H., Juschten, M., and Spash, C. L. (2017). To grow or not to grow? That is the question: lessons for social ecological transformation from small-medium enterprises. GAIA 26, 269–276. doi: 10.14512/gaia.26.3.11

Loorbach, D.A. (2007). Transition Management: New Mode of Governance for Sustainable Development. Amsterdam: Erasmus University Amsterdam.

Lundmark, K. (2002). “The University of Umeå—The University of Northern Sweden,” in Higher Education across the Circumpolar North: A Circle of Learning, eds. D. C. Nord and G. R. Weller. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp 27–45.

Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., and Randers, J. (2002). The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update. Hartford, CT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., and Behrens, W. W. (1972). The Limits to Growth. New York: New American Library.

Moriarty, P., and Honnery, D. (2017). Three futures: nightmare, diversion, vision. World Futures. 74, 51–67. doi: 10.1080/02604027.2017.1357930

Næss, A. (2012). “The deep ecological movement: Some philosophical aspects,” in Ecophilosophy in a World of Crisis Critical Realism and the Nordic Contributions, eds R. Bhaskar, K. G. Høyer and P. Næss (London: Routledge), 84–98.

Nesterova, I. (2020a). Degrowth business framework: implications for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 262, 121382. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121382

Nesterova, I. (2021a). Small firms as agents of sustainable change. Futures 127, 102705, doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2021.102705

Nesterova, I. (2021b). “Small, local, and low-tech firms as agents of sustainable change,” in Sustainability Beyond Technology, eds P. Heikkurinen and T. Ruuska (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Nesterova, I. (2021c). Addressing the obscurity of change in values in degrowth business. J. Clean. Prod. 315, 128152. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128152

Norrie, A. (2010). Dialectic and Difference: Dialectical Critical Realism and the Grounds of Justice. London: Routledge.

Rockström, J.W., Steffen, K., Noone, Å., Persson, F.S., Chapin III, E., Lambin, T.M., et al. (2009). Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecol. Soc. 14, 32. doi: 10.5751/ES-03180-140232

Sayer, A. (2015). “Critical realism in geography,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, ed J. D. Wright (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 277–280.

Schmid, B. (2018). Structured diversity: a practice theory approach to post-growth organisations. Manag. Revue 29, 281–310. doi: 10.5771/0935-9915-2018-3-281

Schmid, B., and Taylor Aiken, G. (2020). Transformative mindfulness: the role of mind-body practices in community-based activism. Cult. Geogr. 2020, 1–15. doi: 10.1177/1474474020918888

Schönherr, N., and Martinuzzi, A. (2019). Business and the Sustainable Development Goals: Measuring and Managing Corporate Impacts. Cham: Springer Nature.

Schumacher, E.F. (1993). Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as If People Mattered. London: Vintage Random House.

Spash, C.L. (2015). Review essay: the future post-growth society. Dev. Change 46, 366–380. doi: 10.1111/dech.12152

Spash, C. L. (2017). The Need For and Meaning of Social Ecological Economics. Available online at: http://www-sre.wu.ac.at/sre-disc/sre-disc-2017_02.pdf (accessed December 05, 2021).

Spash C. L. and Smith, T. (2019). Of ecosystems and economies: re-connecting economics with reality. Real-world Econ. Rev. 87, 212–229.

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., et al. (2015). Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347, 1259855. doi: 10.1126/science.1259855

Swedish Institute (2021). Energy Use in Sweden. Available online at: https://sweden.se/climate/sustainability/energy-use-in-sweden (accessed December 05, 2021).

Trainer, T., and Alexander, S. (2019). The simpler way: envisioning a sustainable society in an age of limits. Real-world Econ. Rev. 87, 247–260.

Tuan, Y.-F. (1974). Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values. New York: Columbia University Press.

Tuan, Y.-F. (1976). Humanistic geography. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 66, 266–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1976.tb01089.x

Tuan, Y.-F. (2013). Romantic Geography: In Search of the Sublime Landscape. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Waas, T., Hugé, J., Verbruggen, A., and Wright, T. (2011). Sustainable development: a bird's eye view. Sustainability 3, 1637–1661. doi: 10.3390/su3101637

Keywords: degrowth, critical realism, humanistic geography, Northern Sweden, firm

Citation: Nesterova I (2022) Being in the World Locally: Degrowth Business, Critical Realism, and Humanistic Geography. Front. Sustain. 3:829848. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2022.829848

Received: 06 December 2021; Accepted: 05 April 2022;

Published: 27 April 2022.

Edited by:

Simon Mair, Bradford University School of Management, United KingdomReviewed by:

Elke Pirgmaier, University of Lausanne, SwitzerlandTom Waas, Thomas More University of Applied Sciences, Belgium

Copyright © 2022 Nesterova. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Iana Nesterova, aWFuYS5uZXN0ZXJvdmFAdW11LnNl

Iana Nesterova

Iana Nesterova