94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain., 10 May 2022

Sec. Sustainable Organizations

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2022.798330

This article is part of the Research TopicEducation for Sustainable Development: How Can Changes in Local Practices Help Address Global ChallengesView all 8 articles

What transforms society? Using the quintuple helix model (QHM) of social innovation, this study examines how the Okayama Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) project has transformed the local community and its people, and how this has led to global recognition. Okayama is known as a world leader in ESD and their unique approach is called the Okayama Model of ESD. This study further looks at the institutional configuration on the elements contributed to knowledge co-creation and how the key actors interacted to contribute to societal transformation through knowledge, social innovation, and institutional setting. The goal of this study is to outline the Okayama Model of ESD using the QHM lens constituted of five helices; education, politics, society, economy, and the natural environment. This study applies a qualitative research method, in which key actors who contribute most to the development of the Okayama Model of ESD are identified by content analysis and semi-structured interviews that are conducted using the life history method. The result shows that the firm ground of the political subsystem facilitates the interaction among the stakeholders in the three subsystems–education, social, and natural environment, which ultimately contributes to the joining of the economic subsystem and the initiation of the knowledge circulation process. Transformation necessitates a city-wide approach involving a network of multiple actors to collaborate for knowledge co-creation and circulation, and the establishment of a new social values system. The study revealed several key points of local action that accelerated the transformation process by helping in value creation, knowledge convergence, and system interaction, which was instilled early through all forms of education—multiple actors' interaction that shapes through the ESD project that stimulates the triangulation of mind, hearts, and hands. This way, the city of Okayama functions as a living laboratory for the Okayama Model of ESD. This situation naturally promotes Mode 3 of the knowledge co-creation system, and the principles of civic collaboration and citizen engagement developed through the Okayama Model of ESD have been elaborated in the prefecture-wide vision statement.

Providing an enabling environment for transformation is crucial to attain a sustainable society. The quintuple helix model (QHM) is one of the frameworks that promotes knowledge and creativity as valuable resources in the development of society (Carayannis et al., 2012). The framework includes five key domains—education, politics, society, economy, and the natural environment—that represent the actors in society and drive the transformation in response to the anthropogenic challenges of global warming. As a result, QHM is used in a systemic change mode to shift from technological to social innovation (Franc and Karadžija, 2019; Fazey et al., 2021). Beginning with the emergence of the triple helix system's knowledge economy, society's transformative approach evolved into the quadruple helix system, which relates to knowledge society and knowledge democracy, and later on into the QHM system, which refers to a broader perspective of socio-ecological transformations and the natural environment (Campbell et al., 2015). The European Commission has mentioned this socio-ecological transition as the future roadmap of development (Carayannis et al., 2012). This is where social innovation becomes one of the most important elements in development strategies. The model's interactive mode enables knowledge exchange and co-creation in a transdisciplinary approach (Carayannis and Campbell, 2010) by integrating public opinion in knowledge development, creative industries, politics, lifestyles, culture, values, and norms (MacGregor et al., 2010; Sunina and Rivza, 2016). However, the interaction that results in the transformation of society is yet to be caught elsewhere.

Education for sustainable development (ESD) is defined by Wals and Kieft (2010) as “a vision of education that attempts to reconcile human and economic wellbeing with cultural traditions and respect for the Earth's natural resources.” This broad definition emphasizes several learning aspects of ESD, such as future education, citizenship education, education for a culture of peace, gender equality and respect for human rights, health education, population education, education for protecting and managing natural resources, and education for sustainable consumption. Further, ESD was developed to assist communities in developing their sustainability goals or action plans based on educational change (Arbuthnott, 2009), while the ESD toolkit was developed to assist communities in developing their sustainability goals (McKeown et al., 2002). There is a need for a systemic approach to accelerate the entire transformation process in society (Brennan, 1997) by involving multiple domains—social, political, cultural, and technical (Hölscher et al., 2017). Besides, it is difficult to develop tools and methods to capture change across such wide-ranging domains (Williams and Robinson, 2020) and over long time periods (Schot and Kanger, 2018). This study tries to demonstrate the gaps using QHM for the homegrown practices of the Okayama Model of ESD.

The Okayama Model of ESD is a concept and term that has got widespread recognition and been used as a result of the unique nature of the Okayama ESD project, a joint public–private initiative. The Okayama ESD project is based on the principle of engaging all citizens in an integrated approach. The model received the UNESCO–Japan Prize for ESD in 2016, which honors and showcases outstanding and innovative ESD projects and programs within the framework of the Global Action Programme on ESD (GAP) (UNESCO., 2017b). The model describes various actors' involvement such as a network of schools, community learning centers (Kominkan in Japanese), the government, corporations, NGOs, and other civil society organizations. However, none of the research studies the actors' interaction in a systemic way.

The city is also involved in the global network of regional centers of expertise (RCEs) for ESD governed by United Nations University, Tokyo, Japan (Mochizuki and Fadeeva, 2008). “RCE Okayama” plays a crucial function by working actively with the local stakeholders across the network. Regarding how this “Okayama Model” promoted by RCE Okayama has penetrated into the local community, the Okayama ESD Promotion Commission—the promoting body of RCE Okayama—suggests that there was a unique and considerable effort at the beginning of the project to link school education and social education with the diverse practices that already existed in the community. From Usami (2017), it can be seen that this was due to the fact that the project's secretariat office was located within the local government—Okayama City Council—as the ESD Promotion Division, and the local government actively provided financial and human support to involve businesses, schools, and citizens' groups. In other words, the city has made ESD a public project, which has broadened the vision of ESD and made it possible to involve more citizens, leading to transformation. For ESD to spread this way, people's sense of urgency about the sustainability of the earth is considered to be an important driving factor. However, as the Okayama prefecture is one of the least disaster-prone areas in Japan and is blessed climatically, naturally, and culturally, it is a contradictory situation that the general public's sense of urgency about sustainability is low. After World War II, the industrial structure of the region changed dramatically, and lifestyles have rapidly become more urbanized, leading to considerable changes in the way they interact with nature. In this sense, this study suggests that the Okayama Model of ESD has the potential to be more universal and versatile.

In the current context of sustainable development goals (SDGs), quality education (SDG No 4) or ESD has been stated under Target 4.7 (UNESCO., 2017a). ESD has been announced as a key enabler to the 17 SDGs toward 2030 with special attention to individual transformation, societal transformation, and technological advances (UNESCO., 2020). The emphasis on the five priority actions is advancing policy, transforming the learning and training environment, developing the capacity of educators and trainers, mobilizing youth, and accelerating sustainable solutions at the local level. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze whether and how the Okayama Model of ESD relates to and accelerates these priority actions, and if not, why not. SDG 4.7 is as follows:

“By 2030 ensure all learners acquire knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including among others through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship, and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture's contribution to sustainable development.”

The emphasis of QHM on knowledge and social innovation as the most essential resources entails significant collaboration of players that create a platform for knowledge co-creation. This is aligned with the spirit to achieve sustainable development and combat climate change. In the sustainable transition phase, QHM places a strong emphasis on the interaction of nature and environment as the focal point of society's transformation. This transformational mindset is congruent with the objective of ESD.

Some parts of transformation that took place toward the sustainable society of Okayama from various perspectives of ESD have been demonstrated in several studies. This includes institutionalization of lifelong education in Japan by local government (Maehira, 1994), high dependency of development of ESD initiative to the relevant Ministries—Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) and the Ministry of the Environment (Nomura and Abe, 2010), reorienting education toward sustainable education (Clark et al., 2020), review of ESD implementation in higher education institutions (Kitamura and Hoshii, 2010), and the emergence of the Japanese ESD movement (Nomura and Abe, 2009). These studies explain the formal education contribution of ESD in the Okayama prefecture. However, none of them identify the actors' contribution to the city's transformation process toward a sustainable society in the lens of QHM as a transformative approach, which shares the same agenda with ESD. QHM becomes a framework of societal ecological transformation in addressing the 21st century climate change crisis, which is part of the societal transformation (Feola, 2015).

The expansive economic growth and development brings its consequences and questions how sustainable the society is. Several local studies in the Okayama region highlighted how the environment affects the waste generation rate (Matsui, 2015), uranium contamination (Yamamoto et al., 1974), searching final waste disposal method (Na et al., 2007), and presence of microplastic (Yamamoto et al., 2021), which portray the local challenge. Those studies briefly describe the state of sustainable society that requires the social actor's contribution to solve the problem. Action-oriented research was documented in several studies covering topics such as conservation of waste cooking oil (Yang et al., 2017), sustainable energy policies (Izutsu et al., 2012), improving rural connectivity through information technology (Fujinami, 2017), marine conservation programs (Sakurai and Uehara, 2020), fishers' conservation (Tsurita et al., 2018), and forest vegetation for conservation (Ohta and Hada, 2012). Concern on a sustainable future through ESD has been raised by recognizing the key sustainable development issues. The key issues are climate change, disaster risk reduction, biodiversity, poverty reduction, and sustainable consumption (Leicht et al., 2018). Those natural forces are part of the transformation of society. However, those studies do not identify the key actors' involvement in mobilizing action performed by the communities in Okayama. This part is crucial in leading societal transformation through transformative learning.

According to Jack Mezirow's adult transformational learning theory in the 1980s, the transformation aimed to be a comprehensive, idealized, and universal model comprising the general structures, elements, and processes of adult learning. Culture and situations determine the structure's elements and process, which are constructivist to the learner's interpretation and reinterpretation in producing meaning and learning through their sense of experience. These theories of lifelong learning and adult learning have been accepted in social education in Japan, and they have been reflected in the Kominkans that have been established to realize these principles. In particular, Okayama City is the town with the most active social education system in Japan, and its Kominkans are known as good models that have developed many learning activities based on this philosophy. The Okayama ESD project has developed around Kominkans, and it goes without saying that Mezirow and other theories of experience-based learning and transformative learning are fundamental to the learning theory that underpins the project. The initiative came to complement the existing formal education system, such as schools and the university. Therefore, it can be said that the model establishes a learning environment for transformation that fits into the QHM's sociocultural domain (Carayannis and Campbell, 2018). The Okayama ESD Promotion Commission that promotes the projects entails collaborative interaction among several parties or stakeholders, including administrative entities, citizens' groups, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and higher education institutions (Abe and Habu, 2009). Yet, it is unclear how societal engagement occurred.

In the name of transformation, various forms and levels of education are required to support societal transformation. The individual level of transformative learning of adult learners, outlined previously by Mezirow (1994), advances to a Communities of Practice (CoP) where people with the same concerns and interests interact regularly (Wenger, 1998); further, the transformation requires a platform for social learning or social education (Wals et al., 2017). Here, there is a shift from teaching to learning (Kolb and Kolb, 2005) beyond formal education through experiential learning, which can bring new ideas and behavior for change (Craps and Brugnach, 2021). To support that, it is necessary to create a social environment that encourages transformation beyond formal education or non-formal education (NFE). This is coined as lifelong learning, which is vital for the transformation of society.

QHM provides the potential for knowledge creation and creativity (Carayannis et al., 2012, 2017), and social (societal) interactions (Carayannis and Campbell, 2010) in a specialized environment (Baker and Mehmood, 2015). This is to catalyze the development of new technologies, knowledge, and societal transformation (Grundel and Dahlström, 2016). It demonstrates how intricately interwoven civilization and nature are. The social innovation component encourages collaboration to address social problems through innovative community activities and is linked to societal performance and innovation (Franc and Karadžija, 2019). The phrase “social innovation” is based on an earlier definition of traditional innovation as “the doing of new things or the doing of things that are already being done in a new way” (Schumpeter, 1947). New solutions (products, services, models, markets, processes, and so on) simultaneously meet a social need (better than existing solutions) and lead to new or improved capabilities and relationships for better asset and resource utilization (Murray et al., 2010). Social innovations are beneficial to society and increase society's power to act. However, the process of producing social innovation may need iterative action, reflection, and deliberation of individuals and groups of effort. This is where they need to engage in sharing their experience and ideas to solve complex challenges collaboratively. This is termed as social learning (Diduck et al., 2005; Keen et al., 2005).

The social component of the QHM paradigm aims to capture community and public-based media participation in knowledge co-creation. The (societal) interchange and transfer of knowledge outside of schooling subsystems constitutes the social and collaborative learning dimension (Barth, 2011). This platform extends the linear model of invention that has been utilized for decades in basic research (Narin et al., 1997). From the formal education mode that allows transdisciplinarity through a campus living lab (Zen, 2017; Zen et al., 2019), this interaction of a non-linear innovation model collects several types of information in transdisciplinary research beyond formal education, which facilitates Mode 3 of knowledge co-creation (Grundel and Dahlström, 2016; Provenzano et al., 2016; Franc and Karadžija, 2019; Durán-Romero et al., 2020). However, few articulated how the various expertise and know-how are employed in the context of the QHM framework.

There is a link between knowledge co-creation, various actors' involvement, and the mode of education underlying the aspiration of QHM that is yet to be explained. Several pedagogical approaches that relate to knowledge co-creation are found in the informal learning process (García-Peñalvo et al., 2013) and learning through experiential learning (Tanaka et al., 2016). Moreover, several modes of involvement—that is, community participatory video (Tremblay and Jayme, 2015), stakeholder engagement for water planning (Graversgaard et al., 2017), and collaborative water governance—provide a platform for interaction but are yet to explain how this interaction takes place. These approaches have a transformative component that can be used to transform society. However, a study that demonstrates how the whole society transforms is yet to be found elsewhere.

The term “social-ecological transition” refers to recent political, financial, and cultural changes that have resulted from efforts to address the social-ecological crisis. The dilemma of the 21st century, which includes climate change, biodiversity and ecosystem loss, artificial intelligence, obesity, pandemic, and their intersection (IPBES, 2018; IPCC, 2018), requires rapid action on the part of people and society as a whole. Effective and systemic changes are required to inspire fundamental changes at the individual, community, and societal levels. How institutions adapt by creating the conditions for social learning is rarely emphasized (Armitage et al., 2011). Emphasis on changes in the way actors interact is also required (Clark et al., 2020), especially on how humans interact with nature in the context of socio-ecological systems through consistent practice and collective action within certain geographical concern (Anderies et al., 2004). Community participation in solving issues through science or Citizen of Science (Calabrese Barton, 2012; Pykett et al., 2020) shows the contribution of the scientific community toward creating a social learning environment in a more participatory fashion. Therefore, the social consequences of various efforts to change captured in the sustainability transition smooth the transformational changes (Williams and Robinson, 2020).

The four key thrusts of Agenda 21 are public awareness and knowledge access to high-quality basic education; reorienting existing education and all-sector training, which also enhances the cognitive, social, emotional, and behavioral dimensions of learning as a holistic and transformational change that encompasses learning content and outcomes; pedagogy; and the learning environment itself (UNESCO., 2014). QHM also serves as a framework for transdisciplinary analysis of sustainable development and social ecology, with its application viewed as a transition from technological to social innovation (Franc and Karadžija, 2019) in a systemic change mode (Fazey et al., 2021) by integrating public opinion in knowledge creation, creative industries, politics, lifestyles, culture, values, and norms (MacGregor et al., 2010; Sunina and Rivza, 2016). The incorporation of public opinion into knowledge co-creation processes is consistent with the ethos of knowledge democratization toward a knowledge-based society and a knowledge-based democracy (Carayannis and Campbell, 2009). As a result, information becomes inclusive and becomes a part of the process of societal development.

In this paper, we aim to outline the Okayama Model of ESD using the QHM lens contributed by their five helices; education, politics, society, economy, and the natural environment. This work discusses the following: (i). how the various actors represented in the helices interact and contribute to the transformation of the city through ESD implementation in formal and non-formal education; (ii). how the political domain contributes to sustainable governance to facilitate transformation of the society; and (iii). how the community at their level addresses the local issues related to the natural environment and what are the economic factors that contribute to the long-term transformation of society. Such initiatives would bolster the socio-ecological shift that is occurring in tandem with local concerns.

Okayama City, located on the north shore of the Seto Inland Sea in Japan, is a major hub of education, social welfare, culture, medical services, and transportation in West Japan (Figure 1). The city has a population of approximately 700,000 and an area of 790 square kilometers (Figure 2), which is blessed with abundant water and greenery. Another core point is its acknowledgment by the United Nations University as one of the seven initial Regional Centers of Expertise on ESD (RCEs) in the world in 2005. The goal of RCE Okayama is to promote ESD, which reflects the nature of the region; and to create a community where people learn, think, and act together, through interaction and cooperation between people involved in ESD within and outside the region. Multiple individuals and organizations such as schools, universities, Kominkans, NGOs/NPOs, enterprises, and administrations implement ESD with themes of natural environment, international understanding, community development, agriculture, food, energy, and so on (UNESCO World Conference on ESD, 2005).

The QHM framework consists of five actors or domains identified as follows: (i). the education system, which generates and disseminates new knowledge; (ii). the economic system, which controls, possesses, and generates economic capital; (iii). the political system, which has political and legal capital (e.g., laws, clearances, policy, public goods); (iv). media-based & culture-based public civil society, which has social capital, and is characterized by traditions, values, and behavioral patterns; and v. the natural, which has natural capital (e.g., natural resources, climate, air quality, and geological stability) (Carayannis et al., 2012) (Figure 3).

This study's qualitative technique comprises semi-structured interviews with key actors prior to the introduction of the UNESCO Okayama Model of ESD in 2016. This is to go deeply into issues that have been encountered and perceived (McGrath et al., 2019). People participating in the ESD project were interviewed about their role during Okayama's transformation phase toward sustainability. The link between the scholars involved in this process and the key actors emphasizes the examination of human phenomena and the naturalistic paradigm of the transformation. The inclusion of actors, including laypeople and practitioners, contributes to the study's transdisciplinary nature (Mobjörk, 2010) and participatory action research strategy (Thiollent, 2011). It is believed that developing the research process with the help of these two groups will result in robust research output with practical and theoretical implications. Their findings will supplement the scientific findings from the desktop study, which used content analysis as an inductive approach. Furthermore, content analysis employs the Okayama Model of ESD, which contributes to the QHM framework for the creation of a conceptual framework or categories (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008).

The study interviewed the following six actors who have been involved with the Okayama ESD project from the beginning, between October 2020 to February 2021. The process of selecting interviewees, that is, identifying key actors of the project, was based on the desktop surveys and literature review. The list of interviewees is presented in Table 1. Researcher involvement in ESD-related projects with Kominkans, school activity, and Okayama University helps robust data gatherers with the observation during the study. This process allowed the study to develop a deeper and fuller understanding of how the Okayama Model of ESD may affect community life in general and the knowledge co-creation at large. Field observation, which is part of the researcher's work as a professional staff member at the ESD Promotion Center of Okayama University, and involvement with several schools' ESD-related projects help to understand a broader perspective of the QHM.

The results section is outlined based on the following questions: (i). How do the actors in the Okayama Model of ESD interact to implement the ESD project? (ii). What are the initiatives being executed up to today? (iii). How does each of the domains play its role and functions in the context of QHM? and (iv). How has the co-creation of knowledge and values taken place?

In general, the study outlines the results from the interviews according to key actors who represent the system of QHM—their interaction in and contribution to the transformation process of the Okayama Model of ESD. The interviewee's experiences involved in the Okayama Model of ESD were used to validate the main finding. The synthesis from the main finding is explained in Table 2.

The Environment Preservation Department—the Environment Bureau of Municipalities of Okayama City—represents the political domain or sub-system of QHM. The facilitation of the Environmental Bureau to the residential association strengthened by the establishment of the Law for the Promotion of Nature Restoration enacted in December 2002 provides a framework for nature restoration projects implemented through the participation of various local actors. This regulation connects the existing organizations and people dealing with these issues together to promote citizens' awareness and action for environmental issues. Here is how the government plays its roles in educating the public while allowing the co-creation of knowledge and values. This effort was combined with the financial and technical support provided through a framework titled “Environment Partnership Project: EPP” in 2001. Hence, it further raised public recognition toward the importance of creating environmentally sound communities. This mechanism provides a basis for knowledge development and values of the Okayama Model of ESD, and the support continues until today (Table 2).

Second, the media-based & cultural-based public knowledge domain of the QHM version of the Okayama Model of ESD was strongly supported through the establishment of Kominkans. This establishment strengthens the EPP project of ESD by creating a sense of attachment, a sense of belonging between the people and their place, and sensitivity to local issues. Hence, it creates new values systems and social norms from the Okayama Model of ESD as a learning environment for changes that fit into the sociocultural-based domain of QHM (Carayannis and Campbell, 2018). ESD teaches them about the history of the community and place. It gives them more understanding on how to tackle local issues, which shapes the way they interact in the future. Besides, there are community representatives who are involved in the teaching and learning process with the students for the Period of Integrated Studies. The schools allocate a session for the community to get involved in sharing knowledge about their locality (Table 2). Moreover, the creation of a conducive learning environment resulting from the effort of the Okayama ESD Promotion Commission creates a cooperative relationship among diverse groups or stakeholders, which includes administrative bodies, citizens' groups and NGOs, and higher educational institutions (Abe and Habu, 2009).

The government's efforts to create an enabling environment help in stimulating the action of the people in the community. It also helps the actors on the co-learning platform for social innovation (Clark et al., 2020; Carayannis et al., 2012, 2017). This explains the interaction between the political and sociocultural media-based domains. Hence, it resulted from the non-linear social innovation form involving various actors beyond the normal education systems (Barth, 2011), that is, Kominkans, residential association, school network, and academia, which requires learning in a collaborative way (König et al., 2020). This also added to the local indigenous practices that represent the sociocultural domain of the quintuple helix model shown in local wisdom that has a strong environmental dimension such as satoyama (woodlands).

Third, the QHM education system version of the Okayama Model of ESD is explained by several characteristics: (i). strong collaboration between schools and universities, (ii). transformative learning, (iii). involvement in the RCE global network; (iv). the ESD Promotion Commission of Okayama City, (v). strong knowledge culture, and (vi). strong ESD implementation (Table 2). The connection between and within the domains recorded the knowledge transfer among the entities of the system of QHM.

Fourth, the QHM natural environment system version of the Okayama Model of ESD is characterized by the main concern in conserving natural environment resources (Table 3). This is where the landscape of Okayama City becomes the living lab for any ESD project involving community, school children, and local authorities.

Based on interviews with relevant officers, it was found out that the ESD Promotion Commission expanded the ESD to the local communities by providing training about the RCE concepts. This effort was coupled with the provision of a coordinator, who is essential to encourage people to join the project and connect with other organizations to promote ESD activities. The ESD Promotion Commission/Division is funded at the City's expense and is a part of Okayama City Hall. Figure 5 summarizes the chronological sequence of ESD in Okayama.

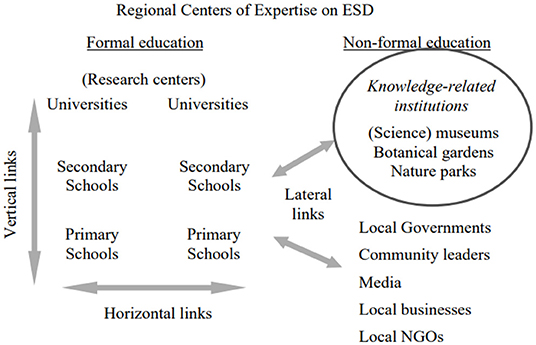

Figure 4. Standard RCE framework and the actors, and the source is UNU (2004).

Fifth, the economic subsystem of the Okayama Model of ESD is demonstrated by the involvement of an architect firm in the ESD cafe (Table 3). The president of an architect firm who participated in the ESD café organized by the Okayama ESD Promotion Commission learned about ESD, consulted with the ESD coordinator, and transformed his company building into an ESD learning center in collaboration with both schools and Kominkans, and began to implement a number of sustainability practices. Specifically, in one area of Okayama City, schools, community centers, and private companies and civic organizations have been working together to build a sustainable society. The results of these efforts have been found in the proactive participation of a large number of children and youth in activities, their growth as “middle leaders” in the area's disaster prevention planning, and the sharing of awareness among local residents. Above all, it is evidenced by the fact that the problematic delinquent behavior of children in the area, which was thought to be caused by the rapid development of the area and the fragmentation among the residents, has improved, and the area is now one of the most popular and prosperous areas for migration among the citizens.

It is worth mentioning that the company has been reflecting the philosophy of sustainability in real estate sales, construction, and urban development; this has raised the interest of the general public in the region toward a sustainable society. In cooperation with the local government, they have established a group consisting of various stakeholders including neighborhood associations, schools, Kominkans, and other local actors/businesses to create a park that can function as a disaster prevention base in the community through dialogues among citizens. It has also linked the junior high school's Period of Integrated Studies to this movement, turning it into an activity in which many citizens participate. At the park, other economic activities such as small businesses, agriculture and food sales based on sustainability, and NPOs that promote satoyama development have started to gather; and a small community of practice for creating a sustainable society has begun to form (Okayama ESD Promotion Commission, 2020).

Another school district in the south of the city, which has been involved in ESD for the longest time, is an area developed by land reclamation and is facing the issue of large-scale agriculture and its management; the elementary school, which is an ASPnet School, is particularly enthusiastic about ESD activities in cooperation with local farmers, university teachers, and students. However, in such a region, an industrial waste disposal company was often perceived as a nuisance. After participating in an ESD coordinator training session organized by the Commission, the company decided to transform itself into an environmentally creative company that would be accepted by the local community. The company has since joined the Okayama ESD project, welcomed the actors to the company, conducted ESD workshops for employees, held lectures at local elementary schools, created environmental education programs, and conducted environmental tours in cooperation with community centers. In Japan, industrial waste management is still often associated with antisocial forces, and there has been a tacit understanding that it is impossible to run a company like this with clear accounting and a break with these forces. However, it is worth mentioning that the company has changed this situation and created an industrial waste business that contributes to the improvement of the local environment (Chugoku ESD Center., 2022).

The Okayama Model of ESD is considered as part of a long-term societal change that was originally based on the Social Education Act launched in the 1940s. Social education is known as Shakaikyôiku, the Japanese word for non-formal education. It is defined by the Social Education Act, Article 2 as the areas of adult education, community education, and education for children and youth that take place outside of school. The overall learning ecosystem of the model is also supported by the local government's establishment of social education infrastructure, financial and technical support, and facilities. The certified social education manager as a module developed by Okayama University with the supervision of MEXT is a form of investment or “input” in QHM to produce highly skilled human resources in managing Kominkans and any other social learning activity as an output (MEXT, 2006). Further, it contributes to sustainable governance and strong institutional support (Ostrom, 1990), and serves as an example for collective action of the socio-ecological system (Anderies et al., 2004) from the EPP/ ESD project. This forms the institutional/organizational changes that contribute to the overall transformation of the society (Table 3). It demonstrates how society overcomes challenges posed by sustainability transition experiments beyond sustainability projects, that is, the ESD project (Williams and Robinson, 2020). This study shows how social learning through knowledge circulation in Kominkans speeds up the transition process, as mentioned by Schäpke et al. (2017). It encourages social change and social innovation, that is, social educator training, which contribute to long-term societal transformation as summarized in Figure 6.

As a regional center for lifelong learning, Kominkans in Okayama City offer a variety of courses and classes for self-realization and cultural and personal interest-based learning such as music, painting, cooking, and dance. The Okayama Model of ESD has focused on the potential of Kominkans and has made full use of their functions. As a result, Kominkans have come to play a major role in the promotion of ESD as knowledge hubs. By facilitating social learning, this approach becomes an example of a sustainable transition experiment within a government organization (Williams and Robinson, 2020). Through active knowledge clusters and innovation networks, it has become a platform for democratizing knowledge in Okayama City through knowledge circulation. This coexisted with the QHM's sociocultural domain, which had a strong non-formal educational realm of ESD dating back to its social education legislation in the 1940s. Kominkans serve as a meeting place for the actors of the education system, such as academia, students, and the sociocultural subsystem, by offering a space for people to learn about knowledge and gain certain skills linked to their culture (Figure 6). As a result, Kominkans and continuous training serve as a framework for consistent community participation and the formation of ESD Communities of Practice (Table 3).

Japan's MEXT promoted the establishment of Kominkans across the country and ratified the social education function as a similar concept with non-formal education. Kominkans are legalized social education facilities, according to the outline of the Social Education Act, Articles 20, 21, and 23. Following World War II, local governments frequently built Kominkans for local inhabitants in compliance with the Social Education Act. Kominkan's mission is to conduct various projects for the cause of education, science, and culture, meeting the daily needs of residents in municipalities and other specific areas to develop their attainments, improve their health, cultivate their sentiment, elevate their cultural life, and increase the community's social welfare. The Minister establishes the standards required for the establishment and operation of Kominkans to promote their sound development.

As social education has a strong connection with Kominkans, it is further defined as all formal, non-formal, or informal education that promotes social development and societal progress (Wang, 2019). In this part, the role of adult education including children and youth non-school education in the community and family was reinstated (Matsuda et al., 2016). Later on, it became citizen-led initiatives where the origin of technical terms of science instilled social values and strengthened the local knowledge and community (Calabrese Barton, 2012). Hence, the Okayama Model of ESD becomes an inspiring example of community-based ESD for effective social learning to facilitate social change (Didham et al., 2017; Wals et al., 2017) with the involvement of citizen science (Calabrese Barton, 2012) driven for the ESD project.

In the context of QHM, the Okayama Model of ESD implements the non-linear innovation model where various types of information are gathered involving various actors beyond the formal education system (Grundel and Dahlström, 2016; Provenzano et al., 2016; Franc and Karadžija, 2019; Durán-Romero et al., 2020). Several initiatives such as Kominkans, ESD projects, social education, and RCE involvement contribute to the transdisciplinarity of the Okayama Model of ESD. This demonstrates the strong intervention of political subsystems into other types of subsystems. Domination of the political subsystem of the Okayama Model of ESD highlights several core points, which are described in Figure 6 and explained below:

• The Governance of the ESD initiative - Starting the ESD project with full commitment of Okayama City smooths the knowledge executed in various communities' projects that involve various modes and levels of education: formal, non-formal, and informal education. The involvement of the local government staff as the executive board of the Okayama UNESCO Association in 1994 in the series of Earth Environmental Lecture of UNESCO educational programs led to ESD activities (Okayama ESD Promotion Committee 2015). The governance of the ESD initiative shows the existence of the Okayama ESD Promotion Commission, which is represented by research institutions, citizen's groups, educational institutions, corporate enterprises, administrative institutions, and media organizations.

• Robust Framework of Knowledge Exchange - The adoption of the RCE knowledge framework (RCE Okayama (Okayama ESD Promotion Commision Secretariat)., 2011) as being part of the involvement of RCE Okayama in the RCE global network was initiated by the municipality of Okayama City (Figure 4). It provides vertical and horizontal knowledge interaction among the education entities. This allows a more diverse knowledge exchange, robust results on the application of the ESD project, and smooth knowledge circulation among key actors. This framework provides a knowledge co-creation platform with other actors or domains of the Okayama Model of ESD. The horizontal knowledge interaction links where each of the school entities has their own knowledge sharing on ESD project within their students. Non-formal education, categorized as social education, involves “Specialized Institutions,” which include art museums, Kominkans, science museums, libraries, botanical gardens, and natural parks. Meanwhile, the possible vertical knowledge among the government, civic communities, and enterprises involves the local government, local education authorities, local UNESCO association, NPOs/NGOs, private enterprises, and mass media. The existence of RCE Okayama with its RCE global framework provides a solid foundation to support social education in Okayama (Table 2). Moreover, being part of the RCE global network, which has around 200 members from various countries, provides a supra learning experience at the global scale by emphasizing local action and facilitates value creation (Mochizuki and Fadeeva, 2008). This is the only platform that connects the local community for local action with global concern or the GloCal approach. It is one of the most effective long-term ways to achieve social transformation, increase environmental awareness, and facilitate the economic de-growth transition (Glavič, 2020).

• Transdisciplinary Knowledge Exchange - The RCE framework of action establishes a transdisciplinary system in which citizens with tacit knowledge are participating in environmental activities. Citizen participation is visible through civic clubs, neighborhood associations, and Kominkans in every community. All of this contributes to the formation of a robust network of social systems and the creation of sustainable resource governance in the context of Ostrom's institutional analysis framework (1990). RCE Okayama's active participation in developing the annual ESD Okayama Award for excellent community-based ESD projects demonstrates their dedication to educating greater society within the RCE network declared by Okayama City (ESD Okayama Award, 2021). Furthermore, the Okayama Environmental Cooperation Project, which is a citizens–local government partnership for ESD projects such as cleaning the river and rescuing endangered species, demonstrates the construction of a conducive atmosphere that stimulates society's voluntary and spontaneous activity. This work highlights how the strong citizen science movement (Calabrese Barton, 2012) contributes to the wellbeing of Okayama society and characterizes the model.

• Values Creation Through a Network of Actors - While a detailed assessment of a sustainable society based on value generation examines value creation from philosophical, ethical, economic, psychological, and technical perspectives, with a focus on society's decision-making dilemma (Ueda et al., 2009), our findings emphasize the creation of social mechanisms for value creation through a network of actors, the existence of a Kominkan as a regular meeting place, the ESD Cafe, and regular ESD training and support. The community-driven ESD initiative launched by the government or political system and reaching out to the societal domain through the Okayama ESD project exhibits significant civil society support in sync with other systems.

• Training the Social Actor - The Social Education Manager's course is offered by the QHM education system, such as in Okayama University. As a response to the stipulations of Articles 9-5 of the Social Education Law, the political domain of QHM, it is co-organized by MEXT and the Faculty of Education, Okayama University. This link strengthens knowledge generation for social innovation. The goal is to govern activities like social education manager training, so that individuals who should be social education managers have the particular knowledge and abilities required to carry out their activities. The course covers a wide range of topics such as lifelong learning theory; lifelong learning society in the framework of social education; collaboration among schools, families, and communities and learning systems I and II; and the significance and function of social education administration.

• Conserving Endangered Species - The natural environmental domain is evidenced by local environmental changes and the Okayama City Council's concern. Actor A's second interview, Interview No. 2, captured this. This scenario can be explained in terms of Japanese agricultural modernization, which has resulted in the loss of wetlands, habitat fragmentation, and contamination of the environment (Naito et al., 2012). As a result of wetland loss, rice paddies and neighboring regions have played an important role in providing substitute habitats for wetland species and supporting the diversity of indigenous ecosystems. Resultantly, the Okayama City Council's Environmental Preservation Division prioritized the preservation of these species. The new agriculture policy in Okayama prefecture's suburban area acknowledged that both patch- and landscape-scale factors can influence pond frog distribution (Yamamoto and Senga, 2012).

• Activities at School for the Local Environment - The Okayama City Council-funded ESD project forges an intriguing link with the QHM education system. Their Division of Environment Conservation has taken the lead in involving the school in the preservation of several endangered local species. The ASPnet school students, for example, investigated how to reintroduce the endangered wild bellied newt Cynopspyrrhogastersp to their river ecosystem, feeding them once more. The school nurtures the nature conservation character of its students from an early age by connecting them with their local environment. This initiative establishes a solid foundation for future generations to care for their natural environment, particularly in the Okayama region. This initiative exemplifies the link between education and the natural environment system as part of the socio-ecological transition that occurred in the Okayama Model of ESD. This is an example of one of the schoolchildren's conservation initiatives to rescue endangered local wildlife.

• Strong Local Network - By connecting networks, for example, encouraging environmental education groups to join this network, the development of the ESD ethos, as described by Abe as a “whole-city” approach, is accelerated. For instance, ESD Promotion Committee members in the most advanced districts have emphasized from the beginning that ESD is important for building a sustainable society, and that collaboration between local residents and the government is essential for this (Usami, 2017). Despite the concern to protect and maintain endangered species and the environment, network connectivity and work accelerates the application and dissemination of the ESD spirit in the Okayama community. This phrase defined Okayama's sustainable society. The council developed the “Okayama ESD Project Fundamental Plan” and launched the “Okayama ESD Project” (Okayama Promotion Commission 2014). This discusses the co-creation of knowledge and values in Okayama.

The natural landscape of Okayama City includes public parks, rivers, and river basins; and endangered species conservation. This initiative provides a platform for ongoing individual capacity development and social learning involvement in the context of socio-ecological transition. The Okayama ecological catastrophe prompted societal transformations through the implementation of the ESD project. For example, an initiative was launched to combat the effects of Japanese agricultural modernization, such as the loss of wetlands, habitat fragmentation, and contamination. As a result, socio-ecological transformation and institutional changes are achieved through the ESD project, which contributes to a sustainable transition with societal transformation. This link contributes to the building of local tacit knowledge in addressing local concerns and promotes the natural environment as a living learning lab, a source of learning, and a source of practical knowledge that contributes to the production of values. Accordingly, the natural environment is being protected using a framework known as “Environment Partnership Project: EPP is a project-based strategy that addresses specific local challenges by involving school children, community/Kominkans, and local government” (Okayama ESD Promotion Commission, 2014).

There are several essential points that connect the Okayama Model of ESD in QHM:

(i) The implementation of the ESD project funded by Okayama City Council functions as a unified entity that synergizes several systems in QHM (Figure 6). Within the educational system, the university is involved in sharing knowledge through lectures and training, community projects involving students and community, and Kominkans. This interaction smooths the co-creation knowledge of Mode 3 or the transdisciplinarity where tacit and scientific knowledge meets (Mauser et al., 2013). Kominkans function as a platform for non-formal education—a social place to nurture the Japanese culture and values, and various talks and programs related to community such as healthy lifestyle, healthy food, and arts and crafts. Presently, since ESD is mainstreamed now in Okayama, the university acts as a leading body of ESD and the additional role of academics at Kominkans is as a coordinator to organize people's opinions and get students involved in local community programs. There are also students ESD-related credits of courses on human resource development from taking part in community/ESD activities. This system expands the university lectures/teacher's connection with community activities (Gardner et al., 2021). The university's community involvement through lecturing relates with the local social issues. Consistency of this effort until today creates a network of society that learns about their local issues.

(ii) Kominkans' social and information system serves as a connector for various stakeholders such as NGOs, NPOs, residential associations, and school networks in the community, and brings people together. Hence, it smooths the knowledge circulation that contextualizes each locality. Kominkans' professional staff, that is, the social education manager is also essential for the accomplishment of self-governing Kominkan operations that necessitate certification. The Kominkan employees, who are elected by local citizens and represent them, may not be qualified, but they are the most knowledgeable about their town. As a result, the element of tacit knowledge and local spirit shows the “Shimoina Guiding Principles.” According to this philosophy, they serve as professional practitioners who work with and for local residents and have a thorough awareness of their requirements.

(iii) Okayama City's nomination as a UNESCO Key Partner of the Global Action Programme on ESD (GAP) to accelerate sustainable solutions at the local level exemplifies the Okayama Model of ESD's knowledge co-production for a sustainable society. This collaborative effort has long been established in Kominkans through community-based learning, which promotes community development, social welfare, and active participation of all community members (Murata and Yamaguchi, 2010); and through the “three-levels” building theory of Kominkans, also known as People's University, which promotes inclusive education and lifelong learning to the Japanese (Kajita and Yamamoto, 1992; Ogawa, 2005). This initiative reinforces Japanese cultural values and social norms. This establishes the foundation for strong tacit knowledge for a transdisciplinary approach and lifelong learning. The establishment of RCE Okayama in 2005, which has a broad knowledge platform from the participation of various actors, has also contributed to this. The earlier establishment of RCE aims to improve ESD around the world and has been successful in supporting the Okayama Model of ESD. The involvement of diverse participants in RCE aims to create new forums for debate and collaboration across numerous organizations and groups in Okayama, including educational institutions, municipal administrations, and civil society, laying the groundwork for social innovation. Resultantly, it appears to be a hybrid autonomous government that promotes innovation (Champenois and Etzkowitz, 2017).

Well-established knowledge circulation through the ESD project and subsystem attracted the local architect firm. This is where knowledge circulation is spreading to the economic subsystem by the active involvement of the local government in education and social education at public platforms like Kominkans. It can also be said that the innovation starts from the encounter and resonance between small individuals, such as an ESD coordinator and a company president, which was also indicated by the transformative learning theory as transformation always occurs in encounters with other perspectives. However, these businesses are still at the nascent stage, and it is necessary to take a long-term look at how much influence they have on the transformation of the local community into a sustainable society.

Through the lens of QHM, this study investigated the theoretical underpinnings and innovative rationales for the Okayama Model of ESD. The previously developed strong social learning culture gives a solid platform for the subsystem and actor to engage. As a result, a Mode 3 transdisciplinary environment is fostered in which each actor's contributions are recognized. The study reveals several practices that other societies in other regions can emulate, with an emphasis on transforming the learning and training environment, developing the capacity of social educators, and providing training for social managers in Kominkans; and provides a platform for social learning for every citizen and various actors to meet, mobilizing youth through the school network and ESD project, and accelerating sustainable solutions at the local level. This QHM lens reveals that the remarkable function of non-formal education in Kominkans outperforms formal education in Okayama. It is because of its power in allowing many vital domains to connect that QHM as an analytical framework captures how diverse stakeholders and a network of participants defined as all learners interact to acquire knowledge and skills as part of an eco-innovation ecosystem to promote sustainable development. Resultantly, it contributes to the socio-transformational development of the Okayama people, which historically has the intention to promote democracy and human rights as well as lifelong learning. The spirit of knowledge sharing and working collaboratively align with the spirit needed to achieve sustainable development and combat climate change.

The following results were reached as a result of this study: (i). The QHM analysis is capable of clarifying the process involved in the Okayama Model of ESD as a non-linear circulation of knowledge as a result of the involvement of various modes of education and communities of practice approaches in Kominkans and the ESD project; (ii). The creation of a conducive knowledge circulation environment with the system's contribution for knowledge co-creation and generation contributes to the co-creation of values and the overall transformation of society; (iii). Okayama has adopted the RCE global framework, which provides a platform for the manifestation of various actors' inter- and transdisciplinary approaches; (iv). Improving actor performance as a knowledge producer and a knowledge user toward knowledge democratization, which is critical in the society's eco-societal transition; and (v). The QHM analysis of the Okayama Model of ESD aids in strengthening the knowledge-based society for eco-innovation in inter- and transdisciplinary approaches.

Over a longer time period where social learning has been in place since the establishment of the social education act in the 1940s, it has contributed to the development of the sustainable society of Okayama, which is referred to as the Okayama Model of ESD.

Even though the study captures the enabling environment that facilitates knowledge co-creation across subsystems, it is unable to document the type of knowledge generated due to the project's short time frame and limited travel permits to Okayama, Japan due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We are grateful to the Sumitomo Foundation (FY19824I) who financed the project. We express endless gratitude and thanks to the partner institution, Graduate School of Okayama, Okayama University, Okayama City Council, and the officers and Kominkans in Okayama City for sharing various insights regarding the Okayama Model of ESD.

Abe, H., and Habu, M. (2009). “Efforts of UNESCO Chair at Okayama University for Realizing a Sustainable Society”, in The manuscript of the 3rd international Conference Higher Education for Sustainable Development. Vol. 20, p. 22.

Anderies, J. M., Janssen, M. A., and Ostrom, E. (2004). A framework to analyze the robustness of social-ecological systems from an institutional perspective. Ecol. Soc. 9. doi: 10.5751/ES-00610-090118

Arbuthnott, K. D. (2009). Education for sustainable development beyond attitude change. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 10, 152–163 doi: 10.1108/14676370910945954

Armitage, D., Berkes, F., Dale, A., Kocho-Schellenberg, E., and Patton, E. (2011). Co-management and the co-production of knowledge: learning to adapt in Canada's arctic. Global Environ. Change. 21, 995–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.04.006

Baker, S., and Mehmood, A. (2015). Social innovation and the governance of sustainable places. Local Environ. 20, 321–334. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2013.842964

Barth, T. D. (2011). The idea of a green new deal in a Quintuple Helix Model of knowledge, know-how and innovation. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Develop. 2, 1–14. doi: 10.4018/jsesd.2011010101

Brennan, B. (1997). Reconceptualizing non-formal education. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 16, 185–200. doi: 10.1080/0260137970160303

Calabrese Barton, A. M. (2012). Citizen (s') science. A response to“ the future of citizen science”. Democ. Educ. 20, 12.

Campbell, D. F., Carayannis, E. G., and Rehman, S. S. (2015). Quadruple helix structures of quality of democracy in innovation systems: the USA, OECD countries, and EU member countries in global comparison. J. Knowl. Econ. 6, 467–493. doi: 10.1007/s13132-015-0246-7

Carayannis, E. G., Barth, T. D., and Campbell, D. F. J. (2012). The quintuple helix innovation model: global warming as a challenge and driver for innovation. J. Innov. Entrepren. 1, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/2192-5372-1-1

Carayannis, E. G., and Campbell, D. F. (2009). ‘Mode 3'and'Quadruple Helix’: toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem. Int. J. Tecnol. Manag. 46, 201–234.

Carayannis, E. G., and Campbell, D. F. (2018). Smart Quintuple Helix Innovation Systems: How Social Ecology And Environmental Protection Are Driving Innovation, Sustainable Development And Economic Growth. Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-01517-6

Carayannis, E. G., and Campbell, D. F. J. (2010). Triple helix, quadruple helix and quintuple helix and how do knowledge, innovation and the environment relate to each other? A proposed framework for a trans-disciplinary analysis of sustainable development and social ecology. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Develop. 1, 41–69. doi: 10.4018/jsesd.2010010105

Carayannis, E. G., Cherepovitsyn, A. E., and Ilinova, A. A. (2017). Sustainable development of the Russian Arctic zone energy shelf: The role of the quintuple innovation helix model. J. Knowl. Econ. 8, 456–470. doi: 10.1007/s13132-017-0478-9

Champenois, C., and Etzkowitz, H. (2017). From boundary line to boundary space: the creation of hybrid organizations as a Triple Helix micro-foundation. Technovation. 76, 28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2017.11.002

Chugoku ESD Center. (2022). Available online at: https://chugoku.esdcenter.jp/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2018/11/82243dba8df7ef116d9b9839e30d61a2.pdf (accessed January 23, 2022).

Clark, I., Nae, N., and Arimoto, M. (2020). “Education for sustainable development and the “whole person” curriculum in Japan,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.935

Craps, M., and Brugnach, M. (2021). Experiential learning of local relational tasks for global sustainable development by using a behavioral simulation. Front. Sustain. 2, 694313. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.694313

Didham, R. J., Ofei-Manu, P., and Nagareo, M. (2017). Social learning as a key factor in sustainability transitions: The case of Okayama City. Int. Rev. Educ. 63, 829–846. doi: 10.1007/s11159-017-9682-x

Diduck, A., Bankes, N., Clark, D., and Armitage, D. (2005). “Unpacking social learning in social-ecological systems: case studies of polar bears and narwhal management in northern Canada”, in Berkes, F., Huebert, R., Fast, H., Manseau, M., Diduck, A. (Eds.), Breaking Ice: Renewable Resource and Ocean Management. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, pp. 269–291 doi: 10.2307/j.ctv6gqvp5.20

Durán-Romero, G., López, A. M., Beliaeva, T., Ferasso, M., Garonne, C., and Jones, P. (2020). Bridging the gap between circular economy and climate change mitigation policies through eco-innovations and Quintuple Helix Model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 160, 120246. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120246

Elo, S., and Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs 62, 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

ESD Okayama Award (2021). Call for Applications!! ‘ESD Okayama Award, 2021’ (city.okayama.jp) Available online at: https://www.city.okayama.jp/kurashi/0000029539.html

Fazey, I., Hughes, C., Schäpke, N. A., Leicester, G., Eyre, L., Goldstein, B. E., et al. (2021). Renewing universities in our climate emergency: stewarding system change and transformation. Front. Sustain. 2, 677904. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.677904

Feola, G. (2015). Societal transformation in response to global environmental change: a review of emerging concepts. Ambio. 44, 376–390. doi: 10.1007/s13280-014-0582-z

Franc, S., and Karadžija, D. (2019). Quintuple helix approach: the case of the European Union. Notitia-časopis za ekonomske, poslovne i društvene teme. 5, 91–100. doi: 10.32676/n.5.1.8

Fujinami, T. (2017). Improving sustainability in rural communities through structural transitions, including ICT initiatives. JRI Res. J. 1, 44–65.

García-Peñalvo, F. J., Conde, M. Á., Johnson, M., and Alier, M. (2013). Knowledge co-creation process based on informal learning competences tagging and recognition. Int. J. Human Capital Inf. Technol. Profess. 4, 18–30. doi: 10.4018/ijhcitp.2013100102

Gardner, C. J., Thierry, A., Rowlandson, W., and Steinberger, J. K. (2021). From publications to public actions: the role of universities in facilitating academic advocacy and activism in the climate and ecological emergency. Front. Sustain. 2, 42. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.679019

Glavič, P. (2020). Identifying key issues of education for sustainable development. Sustainability. 12, 6500. doi: 10.3390/su12166500

Graversgaard, M., Jacobsen, B. H., Kjeldsen, C., and Dalgaard, T. (2017). Stakeholder engagement and knowledge co-creation in water planning: can public participation increase cost-effectiveness?. Water. 9, 191. doi: 10.3390/w9030191

Grundel, I., and Dahlström, M. (2016). A quadruple and quintuple helix approach to regional innovation systems in the transformation to a forestry-based bioeconomy. J. Knowl. Econ. 7, 963–983. doi: 10.1007/s13132-016-0411-7

Hölscher, K., Wittmayer, J. M., and Loorbach, D. (2017). Transition versus transformation: what's the difference? Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 27, 1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2017.10.007

IPBES (2018). Summary for Policymakers of the Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Europe and Central Asia of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn: IPBES secretariat.

IPCC (2018). “Summary for Policy Makers: Global Warming of 1.5?C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5?C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways”, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty.

Izutsu, K., Takano, M., Furuya, S., and Iida, T. (2012). Driving actors to promote sustainable energy policies and businesses in local communities: a case study in Bizen city, Japan. Renew. Energy. 39, 107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2011.07.033

Kajita, K., and Yamamoto, N. (1992). Empirical studies on the institutionalization of lifelong education at the municipalities level. Soc. Educ. Japan. 36.

Keen, M., Brown, V. A., and Dyball, R. (2005). Social Learning in Environmental Management. Earthscan, London.

Kitamura, Y., and Hoshii, N. (2010). Education for sustainable development at universities in Japan. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 11, 202–216. doi: 10.1108/14676371011058514

Kolb, A. Y., and Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Acad. Manage. Learn. Educ. 4, 193–212. doi: 10.5465/amle.2005.17268566

König, J., Suwala, L., and Delargy, C. (2020). “Helix Models of Innovation and Sustainable Development Goals”. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. p. 1–15. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-71059-4_91-1

Leicht, A., Heiss, J., and Byun, W. J. (2018). “Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development”, UNESCO:Paris, France.

MacGregor, S. P., Marques-Gou, P., and Simon-Villar, A. (2010). Gauging Readiness for the Quadruple Helix: A Study of 16 European Organizations. J. Knowl. Econ. 1, 173–190. doi: 10.1007/s13132-010-0012-9

Maehira, Y. (1994). “Patterns of lifelong education in Japan”, in Lifelong Education/Education Permanente. Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 333–338. doi: 10.1007/978-94-011-0087-8_14

Matsuda, T., Kawano, A., and Xiao, L. (2016). Social education in Japan. Pedagogía Social. Rev. Interuniversitaria. 27, 253–280.

Matsui, Y. (2015). Waste generation rate from households and relevant factors in Okayama city, Japan. J. Solid Waste Technol. Manage. 41.

Mauser, W., Klepper, G., Rice, M., Schmalzbauer, B. S., Hackmann, H., Leemans, R., et al. (2013). Transdisciplinary global change research: the co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 5, 420–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2013.07.001

McGrath, C., Palmgren, P. J., and Liljedahl, M. (2019). Twelve tips for conducting qualitative research interviews. Med. Teacher. 41, 1002–1006. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1497149

McKeown, R., Hopkins, C. A., Rizi, R., and Chrystalbridge, M. (2002). “Education for Sustainable Development Toolkit,” Knoxville: Energy, Environment and Resources Center, University of Tennessee.

MEXT (2006). Social education in Japan. Available online at: http://www.mext.go.jp/~component/a_menu/education/detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2010/06/01/1285289_1.pdf

Mezirow, J. (1994). Understanding transformation theory. Adult Educ. Quart. 44, 222–232. doi: 10.1177/074171369404400403

Mobjörk, M. (2010). Consulting versus participatory transdisciplinarity: A refined classification of transdisciplinary research. Futures. 42, 866–873. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2010.03.003

Mochizuki, Y., and Fadeeva, Z. (2008). Regional centres of expertise on education for sustainable development (RCEs): an overview. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 9, 369–381. doi: 10.1108/14676370810905490

Murata, K., and Yamaguchi, M. (2010). Education in Contemporary Japan: System and Content. Tokyo: Toshindo Pub.

Murray, R., Caulier-Grice, J., and Mulgan, G. (2010). “The Open Book of Social Innovation.” The Young Foundation and NESTA: London, UK. p. 3. ISBN 9781848750715.

Na, M., Kurihara, K., and Gion, N. (2007). Optimal allocation of final waste disposal sites based on physical and social factors. J. Environ. Sci Sustain. Soc. 1, 25–32. Available online at: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jesss/1/0/1_0_25/_pdf/-char/en

Naito, R., Yamasaki, M., Natuhara, Y., and Morimoto, Y. (2012). Effects of water management, connectivity, and surrounding land use on habitat use by frogs in rice paddies in Japan. Zool. Sci. 29, 577–584. doi: 10.2108/zsj.29.577

Narin, F., Hamilton, K. S., and Olivastro, D. (1997). The increasing linkage between US technology and public science. Res. Policy 26, 317–330.

Nomura, K., and Abe, O. (2009). The education for sustainable development movement in Japan: a political perspective. Environ. Educ. Res. 15, 483–496. doi: 10.1080/13504620903056355

Nomura, K., and Abe, O. (2010). Higher education for sustainable development in Japan: policy and progress. Int. J. Sustain. High Educ. doi: 10.1108/14676371011031847

Ogawa, S. (2005). Lifelong learning and demographics: a Japanese perspective. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 24, 351–368 doi: 10.1080/02601370500169269

Ohta, K., and Hada, Y. (2012). “The vegetation on the granite rock area at Ashimori”, Okayama City, SW Honshu, Japan.

Okayama ESD Promotion Commission (2014). Okayama ESD project: Learning together and passing on our precious earth to the next generation. Okayama. Available online at: http://www.okayama-tbox.jp/esd/pages/4989">. (accessed September 20, 2021)

Okayama ESD Promotion Commission (2020). “Guide to Promoting Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in Local Communities”, in Shibakawa, H., Yamada, K. and Fujii, H. (eds.) Available online at: https://www.city.okayama.jp/kurashi/cmsfiles/contents/0000022/22185/4.pdf">.

Ostrom, E. (1990). “Governing the Commons”, The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY: USA. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511807763

Provenzano, V., Arnone, M., and Seminara, M. R. (2016). Innovation in the rural areas and the linkage with the Quintuple Helix Model. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 223, 442–447. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.269

Pykett, J., Chrisinger, B., Kyriakou, K., Osborne, T., Resch, B., Stathi, A., et al. (2020). Developing a Citizen Social Science approach to understand urban stress and promote wellbeing in urban communities. Palgrave Commun. 6, 1–11. doi: 10.1057/s41599-020-0460-1

RCE Okayama (Okayama ESD Promotion Commision Secretariat). (2011). ESD Okayama in Promotion (Okayama Model). Global Citizens Conference on DESD 2011. United Nations University RCE Initiative.

Sakurai, R., and Uehara, T. (2020). Effectiveness of a marine conservation education program in Okayama, Japan. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2, e167. doi: 10.1111/csp2.167

Schäpke, N., Omann, I., Wittmayer, J., van Steenbergen, F., and Mock, M. (2017). Linking transitions to sustainability: a study of the societal effects of transition management. Sustain. Account. Manage. Policy J. 9. doi: 10.3390/su9050737

Schot, J., and Kanger, L. (2018). Deep transitions_ Emergence, acceleration, stabilization and directionality. Res. Policy. 47, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2018.03.009

Schumpeter, J. A. (1947). The creative response in economic history. J. Econ. Hist. 7, 149–159. doi: 10.1017/S0022050700054279

Sunina, L., and Rivza, B. (2016). The quintuple helix model of regional development centers in Latvia to smart public administration. Res. Rural Develop. 2, 135–142.

Tanaka, K., Dam, H. C., Kobayashi, S., Hashimoto, T., and Ikeda, M. (2016). Learning how to learn through experiential learning promoting metacognitive skills to improve knowledge co-creation ability. Proc. Comput. Sci. 99, 146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2016.09.107

Thiollent, M. (2011). Action research and participatory research: an overview. Int. J. Action Res. 7, 160–174.

Tremblay, C., and Jayme, B. D. O. (2015). Community knowledge co-creation through participatory video. Action Res. 13, 298–314. doi: 10.1177/1476750315572158

Tsurita, I., Hori, M., and Makino, M. (2018). “Fishers and conservation: sharing the case study of Hinase, Japan,” in Marine Protected Areas: Interactions with Fishery Livelihoods and Food Security, 43.

Ueda, K., Takenaka, T., Váncza, J., and Monostori, L. (2009). Value creation and decision-making in a sustainable society. CIRP Ann. 58, 681–700. doi: 10.1016/j.cirp.2009.09.010

UNESCO World Conference on ESD (2005). ESD City Okayama. Available online at: http://users/User/Downloads/ESD%20City%20Okayama.pdf.

UNESCO. (2014). UNESCO Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2017a). Education for Sustainable Development Goals. Learning Objectives. Available online at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002474/247444e.pdf">.

UNESCO. (2017b). UNESCO Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development. Information Folder. Available online at: https://www.gcedclearinghouse.org/sites/default/files/resources/248081e.pdf">

UNESCO. (2020). Education for Sustainable Development a Roadmap. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802.locale=en (accessed November 26, 2021).

UNU (2004). Regional Centres of Expertise on Education for Sustainable Development: Concept Paper. Available online at: www.ias.unu.edu/binaries2/RCE_Concept_Paper.doc

Usami, R. (2017). “Okayama City: public and private sectors united for ESD. Education for sustainable development success stories”, UNESCO Doc. 0000248941. Okayama City: public and private sectors united for ESD - UNESCO Digital Library

Wals, A. E., and Kieft, G. (2010). Education for sustainable development: Research overview. Available online at: http://www.sida.se/publications (accessed January 13, 2022). doi: 10.1177/097340820900400106

Wals, A. E., Mochizuki, Y., and Leicht, A. (2017). Critical case-studies of non-formal and community learning for sustainable development. Int. Rev. Educ. 63, 783–792. doi: 10.1007/s11159-017-9691-9

Wang, Q. (2019). Japanese social education and kominkan practice: focus on residents' self-learning in community. New Direct. Adult Contin. Educ. 2019, 73–84.m doi: 10.1002/ace.20327

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice Learning as a Social System. Available online at: http://www.co-i-l.com/coil/knowledge-garden/cop/lss.shtml. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511803932

Williams, S., and Robinson, J. (2020). Measuring sustainability: an evaluation framework for sustainability transition experiments. Environ. Sci. Policy. 103, 58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2019.10.012

Yamamoto, K. I., Oshiki, T., Kagawa, H., Namba, M., and Sakaguchi, M. (2021). Presence of microplastics in four types of shellfish purchased at fish markets in Okayama City, Japan. Acta Medica Okayama. 75, 381–384.

Yamamoto, T., Yunoki, E., Yamakawa, M., Shimizu, M., and Nukada, K. (1974). Studies on Environmental Contamination by Uranium: 5. Uranium contents in daily diet and in human urine from several populations around a uranium mine in okayama prefecture. J. Radiat. Res. 15, 156–162. doi: 10.1269/jrr.15.156

Yamamoto, Y., and Senga, Y. (2012). The distribution of the Tokyo Daruma pond frog, Rana porosa porosa, and its habitat status in paddy fields fragmented by urbanization. Japan. J. Conserv. Ecol. 17, 175–184.

Yang, J., Fujiwara, T., and Geng, Q. (2017). Life cycle assessment of biodiesel fuel production from waste cooking oil in Okayama City. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 19, 1457–1467. doi: 10.1007/s10163-016-0540-x

Zen, I. S. (2017). Exploring the living learning laboratory: an approach to strengthen campus sustainability initiatives by using sustainability science approach. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 8, 939–955. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-09-2015-0154

Keywords: Education for Sustainable Development, quintuple helix model, knowledge, social education, transformation