- 1Department of Psychology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, United States

- 2Department of Psychology, University of Essex, Colchester, United Kingdom

Culturally idealized forms of masculinity have been suggested to be endorsed and internalized by men, resulting masculine identities that are easily threatened and inspire status-quo-reinforcing outcomes. The present examined whether receiving gender-incongruent feedback, which was predicted to threaten masculinity in men (but not femininity in women), serially led to public discomfort, anger, and status-quo-reinforcing prejudice toward members of marginalized groups. To test predictions, men and women in two studies (N = 606) took an apparent gender knowledge test and received feedback indicating that their scores were more similar to the average score of women or men. Consistent with predictions, when men received gender-incongruent information they felt more public discomfort and subsequent anger that, in turn, predicted anti-Black attitudes (Study 1), anti-immigrant attitudes (Study 2), and Islamophobia (Study 2); these effects were not significant among women. The present findings replicate prior research showing that, when receiving gender-incongruent information, men experience threats to masculinity that lead to acts of dominance and aggression, which reinforce men-s dominance over women. The present findings also provide novel evidence that threats to men's masculinity—via public discomfort and anger—arouse White men's dominance over marginalized masculinities.

Introduction

Political discourse often involves rhetoric linking culturally idealized forms of masculinity to the protection of White Americans from men who belong to marginalized groups, and who are argued to be uncontrollable and violent. President Trump skillfully employed such tactics, by presenting himself as a strong masculine protector (e.g., Warner et al., 2021) who would fend off the danger presented by violent immigrant men of color. For instance, during his campaign announcement speech, President Trump claimed that “When Mexico sends its people, they're not sending their best... they're bringing drugs. They're bringing crime. They're rapists” (June 16, 2015). President Trump also claimed the need for aggressive surveillance and control of Muslim communities, positioning himself as one who could and would protect against the perceived Islamic threat. In a speech in Fort Dodge Iowa, on November 12, 2015, President Trump said “I will stop radical Islamic terrorism. We have to be so tough, so smart, so vigilant. We can't allow people coming into this country who have this hatred of the United States.” Similarly, political strategist, Lee Atwater, relied on racially charged language and animalistic depictions of Black men to arouse racialized fears of violence when promoting George H. W. Bush as the protector/law-and-order president during his campaign in 1988 (e.g., Willie Horton). Richard Nixon was known for his use of the “Southern Strategy”, which exploited racial fear and backlash against civil rights to woo White voters in the south with promises of protection provided by continued segregation. And former governor of Alabama and four-time presidential candidate, George Wallace, was known for his segregationist views, inflammatory racist rhetoric during the civil rights movement, and vows to protect against the threat of Black men. Throughout history, political leaders have aroused fear of marginalized men and positioned themselves as strong and powerful protectors.

Scholars have also theoretically connected idealized forms of masculinity with the maintenance of the status quo. Specifically, Connell (1995) suggested that there is a hegemonic—or idealized—form of masculinity within each culture that is elevated above other forms of marginalized and subordinated masculinities. According to Connell (1995), hegemonic masculinity is defined by dominant groups of men and is embedded in political and social institutions. As a result, most people endorse and accept hegemonic masculinity as personally beneficial, which functionally reinforces men's dominance over women. Importantly, Connell (1995) also suggested that the broad endorsement and acceptance of hegemonic masculinity reinforces the dominance of men who belong to culture-majority groups over men who belong to marginalized or subordinated masculinities (e.g., men who are racial, ethnic, religious, or sexual minorities). Prior psychological research has examined the linkages between hegemonic masculinity and sexism that reinforces dominance over women and gay men. To the best of our knowledge, however, there has been no empirical work linking hegemonic masculinity to status-quo-maintaining prejudice toward racial, ethnic, national, and religious minorities.

The goal of the present work is to examine the linkages between hegemonic masculinity and status-quo-maintaining prejudice toward racial, ethnic, national, and religious outgroups. Specifically, this work tests the hypothesis that situational threats to White men's internalized hegemonic ideals lead to racial prejudice, xenophobia, and Islamophobia. To consider this possibility, we elaborate the conceptualization of hegemonic masculinity and link men's internalization of hegemonic masculine ideals to experiences of precarious manhood (Vandello et al., 2008). We then review research showing the affective, attitudinal, and behavioral consequences of threats to masculinity that reinforce gender-based dominance. We then point to critical theoretical points of relevance to hegemonic masculinity that have yet to be empirically tested. Based on an integrated consideration of the foregoing points, we then present a novel hypothesis that links situational threats to White men's internalized hegemonic masculine ideals to racial prejudice, xenophobia, and Islamophobia.

Hegemonic masculinity and the status quo

As noted, hegemonic masculinity refers to the idealized form of masculinity within a culture that is defined by dominant men and that is embedded in social and political institutions (Connell, 1995). Because it is embedded in institutions, hegemonic masculinity functions as an ideology that links idealized forms of masculinity to power, status, and success. In other words, hegemonic masculinity is an ideology that defines the attributes that are associated with success and power in culturally valued domains and links those attributes to men and masculinity, but not women and femininity. Importantly, because hegemonic masculinity is an ideology that is embedded in social and political institutions and is endorsed and accepted as beneficial by most people, the endorsement of hegemonic masculinity justifies and legitimates existing social hierarchies.

The endorsement of hegemonic masculinity functionally justifies and legitimates the power that dominant groups of men have over both women and marginalized men (Connell, 1995). In the United States, White cisgender, straight, Christian, middle- and upper-class men represent the dominant men who are the primary beneficiary of hegemonic masculine ideology. Hegemonic masculine ideology elevates masculinity and reinforces male dominance over women by othering femininity and womanhood (de Beauvoir, 2011), given linkages to sexism (Vescio and Schermerhorn, 2021). Likewise, hegemonic masculinity in the United States justifies notions of White male supremacy by othering marginalized masculinities (e.g., racial, religious minority men)—given linkages to prejudice (Vescio and Schermerhorn, 2021)—and stereotypes of racial, ethnic, and religious minority men as inadequate men who either lack the requisite male agency to thrive or who are violent and need to be controlled (Kimmel, 2008, 2013).

Hegemonic masculinity is founded on the gender binary, or the notion that there are two genders—men and women—who are defined in oppositional terms, which contributes to White men's dominance over marginalized men, as well as women. For instance, in contemporary Western societies, hegemonic masculinity (a) prescribes that men should be high in power, status, and toughness—emotional, mental, and physical toughness and (b) proscribes that men should reject and distance from all that is feminine, gay, or low status (Brannon, 1976; Courtenay, 2000; Fischer et al., 1998; Pascoe, 2007; Thompson and Pleck, 1986; Rudman et al., 2012). Stated differently, in Western cultures, hegemonic masculinity prescribes that men should be high in power (e.g., having the potential to influence or control others, French and Raven, 1959), status (i.e., having earned the respect from others, Keltner et al., 2003), and toughness, particularly relative to low power, low status, warm but weak women. If marginalized groups of men are low in power, low in status, or low in toughness they then risk being perceived as womanly and worthy of being dominated and aggressed against. Importantly, while it is socially inappropriate to overtly express racial prejudice, open rejections of men who fail to uphold cherished standards of masculinity, such as immigrants or Muslim men, are socially acceptable.

Men's internalization of hegemonic masculine ideals

Because hegemonic masculine ideals are valued given their linkages to power, status, and success, most men strive to achieve these ideals, even though few men embody those ideals (Connell, 1995). It is difficult to embody power, status, and toughness across contexts; as a result, many men work hard to achieve and maintain masculine ideals that are precarious and easily threatened (Vandello et al., 2008). Because hegemonic masculinity ideals prescribe that men should be powerful, high status, and tough, while repudiating all that is feminine, masculinity is founded on the gender binary and can be easily threatened by leading men to believe that they are like women. For example, threats to masculinity have been aroused by leading men to believe that they are like women in knowledge (Rudman and Fairchild, 2004), behavior (e.g., Bosson et al., 2009), personality (e.g., Vescio et al., 2021, 2023), or skills (e.g., Dahl et al., 2015).

While masculinity can be relatively easily threatened by leading men to believe that they are like women, femininity is not similarly threatened by leading women to believe that they are like men in attitudes, knowledge, preferences, or skills. This is partly because masculinity is valued and associated with high power and high status, whereas femininity is devalued and associated with low power and low status. Thus, men who learn that they are like women may fear being viewed as low power and devalued, which prior research links to greater experiences of backlash (or social and economic punishments, Rudman et al., 2012); by contrast, women who are perceived as being like men may actually feel they are viewed as higher status and more valued (Vescio et al., 2010). Consistent with this notion, when people are led to believe that they gender atypical or like a gender with which they do not identify—in knowledge, behavior, personality, or skills—men show a pattern of threat related emotions and compensatory behaviors that women do not (e.g., Rudman et al., 2012; Rudman and Fairchild, 2004; Vandello et al., 2008; Vescio et al., 2021).

Because gender is central to notions of self (e.g., Markus and Oyserman, 1989), gender threats motivate compensatory responses that functionally appease the gender threat (see Babl, 1979; Vandello et al., 2008). In other words, gender threats inspire actions that reestablish oneself as a good gendered being. Consistent with this assumption, threats to masculinity have been found to lead to an array of threat-related emotions, endorsement of attitudes that justify male dominance, and aggressive behavior that functionally reestablishes one as a powerful, dominant man. For instance, upon learning that one is like a woman, men experience increased public discomfort, or concern about how one looks in the eyes of others, and anger (Dahl et al., 2015; Schermerhorn and Vescio, 2021), as well as more guilt, more shame, and a lack of empathy (Vescio et al., 2021).1 Public discomfort and anger, in turn, have been found to predict endorsement of beliefs that men should be dominant over women (e.g., benevolent sexism, social dominance orientation in gendered domains; Dahl et al., 2015), the sexualization, sexual harassment, and sexual use of women (Dahl et al., 2015; Vescio et al., 2023; Maass et al., 2003), and violence toward gay men (e.g., Schermerhorn and Vescio, 2021). Although theory links hegemonic masculinity to dominance over both women and marginalized masculinities (Connell, 1995), empirical research has yet to explore whether threatening men's internalized hegemonic ideals leads to subordinating attitudes toward marginalized groups beyond women and gay men.

Threats to masculinity and dominance over marginalized masculinities

As noted, hegemonic masculinity has been conceptualized as an ideology that reifies the status quo by othering marginalized men, as well as women (Connell, 1995). If this is the case, then threats to White men's masculinity should lead to dominance over and aggression toward not only toward women, but also toward racial, ethnic, and religious minority groups. Extending prior work showing that threats to masculinity lead to sexist attitudes that subordinate women to men (Dahl et al., 2015; Weaver and Vescio, 2015), we predict that threats to masculinity will also lead to racial, ethnic, and religious prejudices and stereotypes that subordinate marginalized groups. Threats to masculinity would be expected to lead to dominance over marginalized masculinities, as evidenced by increases in prejudice including general measures of racism, anti-immigrant attitudes, and Islamophobia. This would be expected to the degree that normative people are considered to be White men (e.g., Zarate and Smith, 1990) and general measures of prejudice toward any group may capture people's beliefs about prototypic members of those groups—men. We would also expect this pattern on general measures of prejudice if threats to masculinity simultaneously inspire dominance toward marginalized men and women.

Consistent with the general notion that threats to men's internalized hegemonic masculine ideals leads to dominance over marginalized men, as well as women, masculinity has been found to be associated with racism (e.g., Wade and Brittan-Powell, 2001) and anti-immigrant attitudes (e.g., Connell, 2003), as well as sexism (e.g., Kimmel, 2008) and homophobia (e.g., McCusker and Galupo, 2011; Konopka et al., 2021). However, prior work has been correlational. In addition, whereas prior experimental work has suggested that racism provides a threat to the masculine identities of men of color (e.g., Goff et al., 2012; Hammond et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2014), to the best of our knowledge no prior work has examined if threats to White men's masculinity leads to racism, anti-immigrant attitudes, or Islamophobia.

Hypotheses and the current work

We predicted that, upon learning that one is like a gender with which one does not identify (or receiving gender-incongruent feedback), White men (but not White women) would experience threats to gender, as evidenced by elevations in public discomfort and subsequent anger, that predict racial, religious, and nationality-based prejudice. In other words, we predicted patterns of moderated mediation across studies and variables that replicated and extended prior work showing that threats to masculinity serially lead to public discomfort, anger, and dominance over women (Dahl et al., 2015). However, here we predict that gender-incongruent feedback leads to public discomfort, anger, and prejudice in men but not women. Specifically, upon receipt of gender-incongruent feedback, we predicted that White men (but not White women) would serially feel public discomfort, anger, and endorse prejudice (i.e., racism, anti-immigrant attitudes, and Islamophobia).

Predictions were tested across two studies, which used similar designs. After completing a gender knowledge test, White participants were led to believe that they exhibited knowledge more like the average man or the average woman. Participants then completed measures of public discomfort, anger, and racism (Study 1), anti-immigrant attitudes (Study 2), and Islamophobia (Study 2). All data collection was completed prior to data analysis and all variables analyzed are reported. Data sets and syntax can be found at https://osf.io/qk78p. Preregistration for Study 2 can be found at https://aspredicted.org/6ZZ_FW8.

Study 1

Method

Participants and design

Because a-priori power analyses are difficult for mediation due to the inclusion of an indirect effect (Hayes, 2018), we based our sample size of 300 on the previous research (Schermerhorn and Vescio, 2021: Ns = 270–369) from which our moderated serial mediation hypotheses were based. We recruited 301 undergraduates who were White men (N = 140, including 139 cisgender men and 1 transgender man) and White women (N = 161, all cisgender) using a psychology subject pool at a large mid-Atlantic University. Participants were granted course credit for participation. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 37 (M = 18.86, SD = 1.68) and were randomly assigned to one of four conditions created by crossing participant gender (male, female) and gender feedback (like men, like women) in a between-participants design.

Procedure

After reading a consent form, participants were led to believe that they would complete a personality test that is composed of “questions about common gender related knowledge” (Rudman and Fairchild, 2004). Half of the items on the test addressed stereotypically feminine knowledge (e.g., “the first company to develop hair coloring was: L'Oreal vs. Clairol”). The other half were questions about stereotypically masculine knowledge (e.g., “In 1982, who won the Superbowl's' MVP award? Joe Namath vs. Joe Montana”). Upon completion of the gender knowledge test, participants received feedback. Participants learned of their “scores” in relation to the purported average scores of men and women, as displayed by means of a visual spectrum anchored with endpoints “Female Gender Knowledge” and “Male Gender Knowledge.” Participants learned that their scores were similar to the average scores of women or the average scores of men. Participants then completed public discomfort, anger, racism, and xenophobia measures, as well as demographic items, before being debriefed.

Measures

Public discomfort

Using seven-point scales (1 = not at all, 7 = a lot), while imagining that the researchers were going to publish their full name next to their score, participants reported how much they felt anxious, nervous, defensive, depressed, calm, joyful, happy, and confident (Dahl et al., 2015; Vescio et al., 2021). The positive affective items (calm, joyful, happy, and confident) were reverse scored, and we averaged across items to create a public discomfort variable (α = 0.86); higher scores indicated greater public discomfort.

Anger

Using seven-point Likert scales (1 = not at all, 7 = a lot), participants reported the extent to which—“at this moment”—they felt four emotions that tapped anger (i.e., angry, frustrated, hostile, and mad), which were intermixed with six filler items (i.e., calm, competent, happy, anxious, depressed, and proud). We then averaged across the four items to create an anger variable (α = 0.90); higher numbers reflected more anger.

Racism

Participants completed the Ambivalent Racism Scale (Katz and Hass, 1988), using seven-point Likert-type scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). After reverse scoring appropriate items, we averaged across the items of the pro-Black and the items of the anti-Black subscales, respectively, to a create a pro-Black attitudes variable (α = 0.88) and an anti-Black attitudes variable (α = 0.85). Higher numbers reflected greater endorsement of each attitude.

Xenophobia

Using a seven-point Likert-type scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), participants completed a five-item xenophobia scale (van der Veer et al., 2011, e.g., “interacting with immigrants makes me uneasy,” “I am afraid that our own culture will be lost with increases in immigration”). We averaged across items to create a xenophobia variable (α = 0.88); higher scores reflected more xenophobia.

Study 1 results

We predicted serial mediation—gendered feedback would lead to public discomfort, subsequent anger, and racism (pro-Black and anti-Black attitudes)—among men, but not women, which may involve the absence of significant direct and/or total effects. In fact, when effects sizes are small, significant indirect effects demonstrate the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable even when total effects are insignificant (Kenny et al., 1998; LeBreton et al., 2009; Preacher and Hayes, 2008; Shrout and Bolger, 2002; Zhao et al., 2010). However, evidence of direct effects of gender feedback (like men, like women) and/or participant gender (man, woman) resulting from between-participants Analyses of Variance (ANOVAs) performed on each dependent variable are reported in Supplementary Table 1.

To test predictions, we conducted a series of moderated mediation analyses using PROCESS Model 83 (Hayes, 2018). Feedback condition (1 = like women, −1 = like men) was entered as the independent variable and participant gender (1 = men, −1 = women) was entered as the moderator. Public discomfort and anger were entered as mediators and separate analyses were conducted for each of the dependent variables (anti-Black attitudes, pro-Black attitudes, xenophobia). Moderation was tested specifically for the path leading from threat to public discomfort.

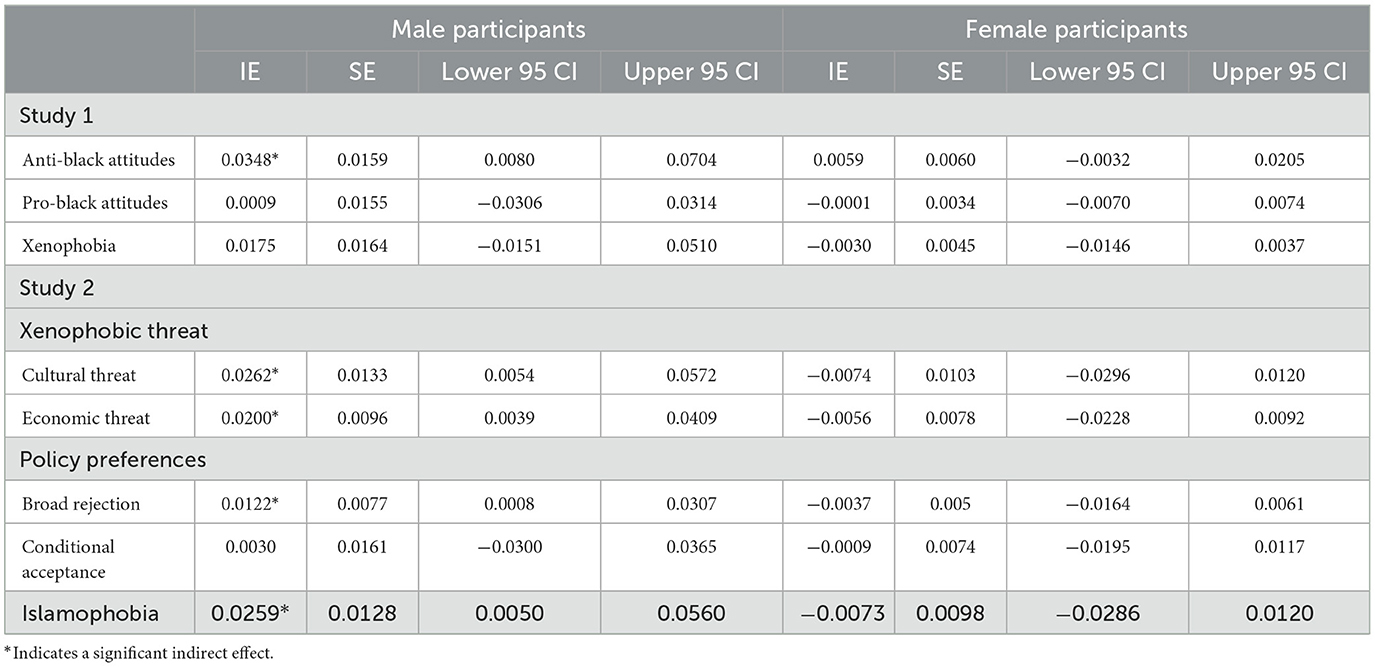

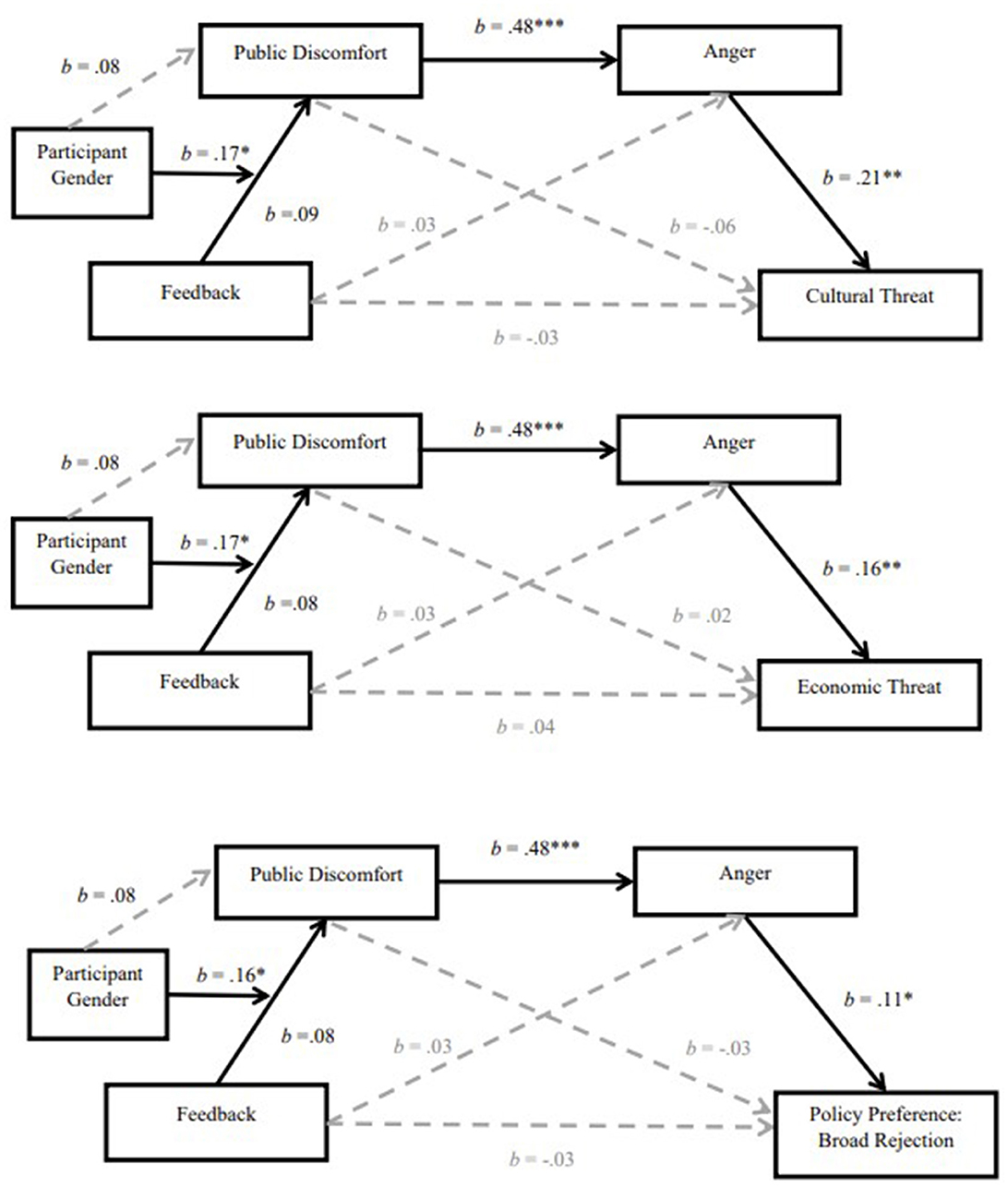

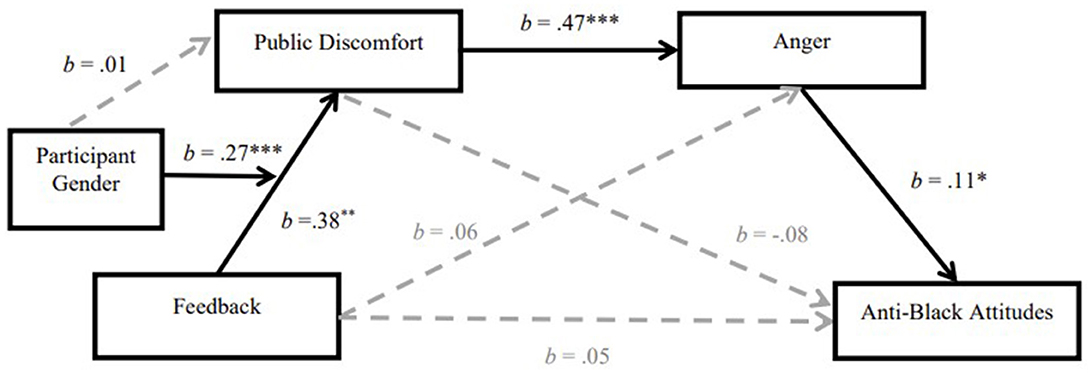

The predicted pattern of moderated mediation emerged on anti-Black attitudes. As shown in Figure 1, gender feedback was associated with public discomfort and that effect was moderated by participant gender; gender feedback predicted increases in public discomfort among men, t(297) = 6.72, p < 0.001, but not women, t(297) = 1.22, p = 0.222. Public discomfort was also associated with greater anger. Anger, in turn, predicted anti-Black attitudes, b = 0.11, SE = 0.046, t(297) = 2.41, p = 0.017, but not pro-Black attitudes, b = 0.00, SE = 0.0515, t(297) = 0.04, p = 0.968. Furthermore, as predicted, the index of moderated mediation was significant on anti-Black attitudes, but not pro-Black attitudes (see Table 1), and the indirect effect of gender threat—via public discomfort and anger—on anti-Black attitudes was significant for men, but not women (see Table 2).

Figure 1. Moderated mediation of gender threatening feedback on anti-black attitudes, Study I. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The predicted pattern of moderated mediation was not significant on xenophobia. Anger did not predict xenophobia, b = 0.0610, SE = 0.0566, t(297) = 1.08, p = 0.283. In addition, the index of moderated mediation was not significant for xenophobia (see Table 1).

Study 1 discussion

Consistent with predictions, findings revealed evidence that gender threats inspired public discomfort and subsequent anger that, in turn, predicted increases in racist attitudes in men but not women. Importantly, the predicted effects emerged on anti-Black attitudes, but not pro-Black attitudes, consistent with the different constructs assessed by the two measures. The anti-Black attitudes scale measures the blame and dispositional attributions ascribed to Black individuals for the relative lower social status of Black people in America. By contrast, the pro-Black attitudes scale measures the endorsement of beliefs that Black Americans are victims of long-standing racial injustice, which is more strongly endorsed (see Supplementary Table 1) and may be less susceptible to situational threats.

Analysis of xenophobia did not reveal the predicted pattern of moderated mediation. In Study 1, we used a five-item measure of intergroup anxiety about people from other countries, or fear-based xenophobia (van der Veer et al., 2011). However, theory on attitudes toward immigrants suggests the importance of four constructs. The first two constructs assess attitudes toward preferences for immigration policies and assess preferences for (a) restrictive policies that broadly reject all immigration, regardless of the immigrant population and (b) conditional restrictions on immigration, which are tolerant of immigration only for native speakers who bring skills/education that will advance a nation. The other two constructs assess perceptions of threat posed by immigrants to culture and to the economy. The assessment of these four constructs has been suggested to provide a more nuanced and cross-culturally valid measure of anti-immigrant attitudes (Meuleman and Billiet, 2012). These four attitudinal constructs were assessed in Study 2. In addition, to further test the prediction that threats to internalized masculine ideals would lead gender-threated men to reject marginalized groups, Study 2 also assessed the impact of gender threats in White men on the endorsement of Islamophobia.

Study 2

Method

Participants

As in Study 1 and noted in our preregistration (https://aspredicted.org/6ZZ_FW8), we sought to recruit 300 participants. Participants were 305 White cisgender men (N = 153) and White cisgender women (N = 152) who were undergraduates enrolled in an introductory psychology course a large mid-Atlantic university, who were granted course credit for participation. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 50 (M = 19.64, SD = 2.90).

Design

Procedure and measures

The design and procedure of Study 2 was similar to Study 1. As in Study 1, we measured public discomfort and anger. However, anti-immigrant attitudes were assessed here with a more nuanced measure that tapped attitudes toward different policy approaches to immigration and different threats. We also included a measure of Islamophobia.

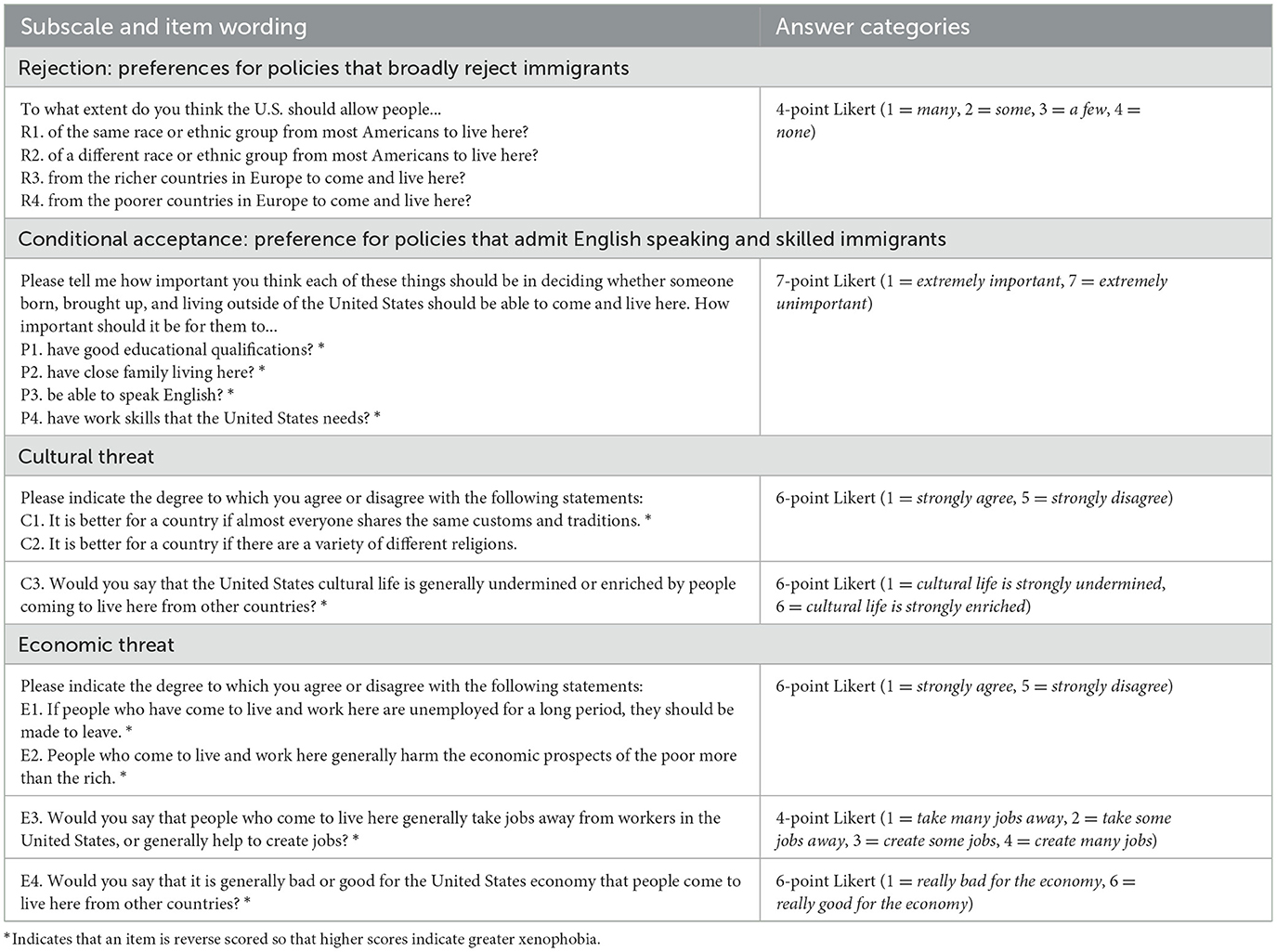

Anti-immigrant attitudes

Participants completed measures of four constructs of anti-immigrant attitudes, which were measured via a subset of items that have been used in the European Social Survey (ESS) and that have been found to be cross-culturally valid (Meuleman and Billiet, 2012). These items assess four constructs, including (1) preferences for restrictive policies that broadly reject all immigrants (five items; e.g., “To what extent do you think the U.S. should allow people of a different race or ethnic group from most Americans to live here?”), (2) preferences for conditional policies that accept native speakers who are skilled/educated (four items, e.g., “How important should it be for them to be able to speak English?”), (3) perceptions of immigrants as cultural threats (three items, e.g., “It is better for a country if everyone shares the same customs and traditions.”), and (4) perceptions of immigrants as economic threats (four items, e.g., “If people who have come to live and work here are unemployed for a long period, they should be made to leave.”). The items and response scales are presented in the Appendix. We reverse scored appropriate items and averaged across items to create two policy variables: preferences for the broad rejection of all immigrants (α = 0.94) and conditional acceptance of native speakers who bring skills (α = 0.86). Because of the use of varied response scales within threat subscales, we standardized responses on each item tapping threat. We then averaged across appropriate items to create two threat variables: cultural threat (α = 0.61) and economic threat (α = 0.72).

Islamophobia

Participants completed an Islamophobia Scale (Lee et al., 2009) using eight-point scales (1 = Strongly Disagree, 8 = Strongly Agree). Items on the scale assessed affective and behavioral responses to Muslim people (e.g., “If possible, I would avoid going to places where Muslims would be.”), as well as cognitive beliefs about Muslim people (e.g., “Islam is a religion of hate.”). We averaged across responses on the scale to create an Islamophobia variable (α = 0.96).2

Study 2 results

As in Study 1, we report the results of all ANOVAs in the Supplementary Table 2 and used PROCESS Model 83 (Hayes, 2018) to test our predicted moderated mediation. Consistent with predictions, evidence of moderated mediation emerged from analyses of anti-immigrant attitudes and Islamophobia.

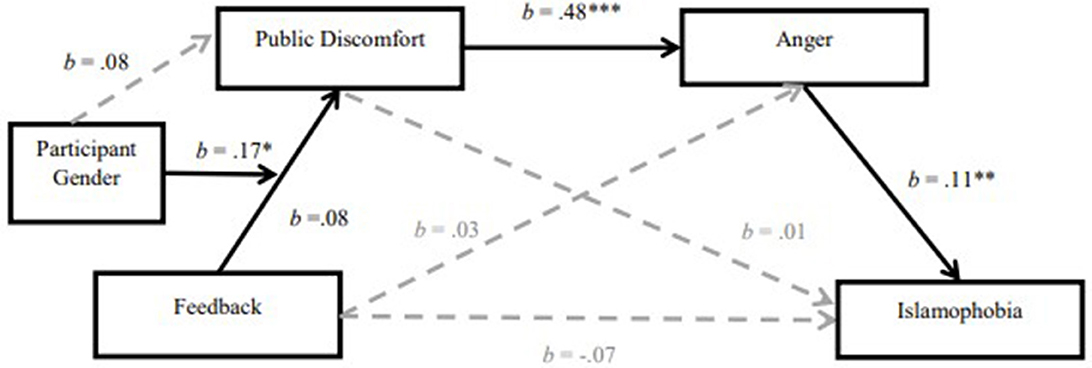

As shown in Figures 2, 3, gender feedback was associated with public discomfort and that effect was moderated by participant gender; gender feedback predicted increases in public discomfort among men, t(301) = 2.83, p = 0.005, but not women, t(301) = −0.97, p = 0.428. Public discomfort was also associated with greater anger. As shown in Figure 2, anger, in turn, predicted cultural threat, economic threat, and preferences for policies that broadly reject all immigrants; also consistent with predictions, the indirect effect of gender threat on each variable via public discomfort and anger was significant for men but not women (see Table 2). As shown in Figure 3, anger also predicted Islamophobia. In addition, the index of moderated mediation was significant for each variable (see Table 1) and the indirect effect gender threat on Islamophobia was significant for men but not women (see Table 2). Anger did not, however, predict preferences for policies that accept English speaking immigrants who are highly skilled/educated (i.e., conditional acceptance), b = −0.02, SE = 0.1150, t(301) = −0.21, p = 0.836, and the index of moderated mediation was not significant on conditional acceptance (see Table 1).

Study 2 discussion

Consistent with predictions, gender-inconsistent feedback predicted increased public discomfort and subsequent anger in men (but not women) that, in turn, predicted anti-immigrant attitudes and Islamophobia. In Study 2, anti-immigrant attitudes were assessed by measuring two threat variables (cultural threat and economic threat) and two policy preference variables (the broad rejection of all immigrants and the conditional acceptance of native speakers who bring skills/education). Consistent with predictions, among men (but not women), gender threat—as evidenced by increased public discomfort and anger—predicted cultural threat and economic threat. Similarly, gender threat predicted preferences for the broad rejection of all immigrants. A parallel pattern was also found on Islamophobia. Learning that one is like a gender with whom one does not identify was associated with increased public discomfort in men, but not women. Public discomfort predicted subsequent anger that, in turn, was associated with anti-immigrant sentiment and Islamophobia.

Interestingly, parallel patterns did not emerge on preferences for immigration policies that conditionally accept English speaking people who are highly skilled/educated. There are several possible reasons for the lack of parallel findings. The lack of findings could possibly be due to the psychometric properties of the scales. Specifically, the items assessing preferences for policies that broadly reject all immigrants have been found to show a high cross-cultural validity, with the results of a multi-group confirmatory factor analysis performed across cultural groups showing that the number of violated equality constraints was limited for the reject scale, while the conditional accept scale is cross culturally far less robust (Meuleman and Billiet, 2012). Alternatively, the lack of parallel findings on the conditional acceptance scale may be related to the American context and the strong nationalism, such that xenophobia leads to broader rejection rather than conditional acceptance of immigrants. Finally, our theoretical back drop is consistent with the suggestion of some scholars; namely, those that suggest prejudice is expected to be directed toward low-status groups, rather than a generalized prejudice toward all outgroups (Bergh et al., 2016), which could explain why gender threat did not predict prejudice toward immigrants who bring skills. Nonetheless, the findings of Study 2 provided strong and consistent patterns of findings supportive of predictions. Together, the findings of Studies 1 and 2 provide evidence that moderated mediation emerged on anti-Black attitudes, xenophobic threat (cultural and economic), preferences for anti-immigrant policies that broadly reject immigrants, and Islamophobia. Of note, our cultural threat variable had a lower alpha reliability, potentially because the scale consisted of only three items. Future work may want to consider alternative measures of cultural threat.

General discussion

Two studies examined whether the receipt of gender incongruent feedback resulted in gender threats in White men (but not White women), serially leading to increases in public discomfort and subsequent anger that was associated with negative attitudes toward marginalized racial, religious, and immigrant people. Findings across studies were consistent with predictions. When White men learned they were like women (vs. men) they reported increased feelings of public discomfort and subsequent anger. Anger, in turn, predicted increases in explicitly stated negative attitudes toward Black Americans (Study 1), immigrants (Study 2), and Muslim people (Study 2). This pattern did not emerge for White women who learned they were like men.

The predicted pattern of results emerged across variables with two exceptions. First, threats to masculinity did not predict xenophobia as measured generally (in Study 1) or the conditional restrictions on immigration measure (Study 2). In hindsight, our original predictions may have been based on a misconception of these measures. Specifically, our predictions were based on the logic that threats to internalized hegemonic masculine ideals would lead to prejudice that reinforces men's dominance over women and White men's dominance over marginalized men. From this perspective, threats to masculinity should inspire prejudice toward low-status men who fail to embody hegemonic masculine ideals but should not inspire prejudice to high status men who successfully embody hegemonic masculine ideals (e.g., rich men, professional athletes, high-power CEOs, see also (Bergh et al., 2016). When extended to considerations of xenophobia and restrictions on immigration, we would expect that threats to masculinity should predict the rejection of low-status foreigners and/or immigrants who are perceived as failing to embody hegemonic masculinity, not all foreigners and immigrants. In other words, these two measures assess broad attitudes toward immigrants who do and do not embody hegemonic masculine ideals, which work against predictions and could explain our lack of findings on these two measures.

Second, threats to masculinity had the predicted effects on anti-Black attitudes, but not pro-Black attitudes (Study 1). Our predictions across variables were based on the assumption that endorsement of prejudice functionally appeases threats to masculinity by reestablishing White men as high status, powerful, and dominant over marginalized men. The endorsement of anti-Black attitudes unambiguously reinforces White men's dominance over Black men, who fail to embody culturally idealized notions of agency, resilience, power, and status and, unsurprisingly, the predicted effects emerged on anti-Black attitudes. It is unclear how reductions in the endorsement of beliefs that Black Americans face situational barriers and discrimination (i.e., pro-Black attitudes) would functionally appease threats to masculinity by reestablishing White men and good men who are high in power and status. Stated differently, while prior work has shown that broader threats affect perceptions of systemic inequality (e.g., Blodorn et al., 2016; Lesick and Zell, 2021), we would expect gender threats in White men to lead to prejudice that reestablishes them as good men, who are high in power and status.

There are limitations of the present set of studies that should be addressed in future work. Most notably, we used the same manipulation of gender threat across studies: people were led to believe that they possessed gender-atypical or gender-typical knowledge. Masculinity has also been shown to be threatened when men are outperformed by women in masculine domains (Dahl et al., 2015), when men perform gender-atypical tasks (e.g., hair braiding, Bosson et al., 2009), and when heterosexual men are targets of the sexual advance of a gay man (Schermerhorn and Vescio, 2021). We would expect to replicate the pattern of findings documented here using any of the manipulations that prior work has shown to threaten masculinity. Furthermore, theoretically, threats to masculinity would also be expected to occur whenever men are low in power, status, dominance, and toughness particularly relative to a woman, given heterosexual interdependencies. Another limitation of our work is that our prejudice scale items did not specify gender and, given that people hold androcentric biases (Bailey et al., 2020), participants may have responded with men in mind. Therefore, future work should explore if the pattern of findings generalizes to women who are Black, immigrants, or Muslim.

Future research should also examine when and with what consequences femininity is threatened. Whereas, leading participants to believe that they are gender incongruent in meaningful ways has been found to lead to gender threats in men but not women, recent research has identified conditions that result in femininity threats. Leading people to believe that they do not physically look like good members of the gender with which they identify has been found to lead to both femininity threats in women and masculinity threats in men (Wittlin et al., 2024; see also Steiner et al., 2022). Gender threats resulting from shortcomings in physical appearance have been found to produce both anxiety and insecurity in women, as well as anxiety in men (Wittlin et al., 2024). Interestingly, while there is some evidence that anxiety (at least social anxiety) is associated with increased feelings of hostility, the same work also shows that anxiety is related to less aggressive behavior (e.g., DeWall et al., 2010). Therefore, we would not expect the anxiety following from physical gender threats to be associated with status-quo-maintaining acts of attitudinal and behavioral dominance over marginalized groups in men or women.

In addition, leading women to believe that they lack positive and stereotypically feminine attributes (e.g., warmth, maternal instincts) has been found to lead to anger and relational aggression, which does not contradict femininity prescriptions in the way that physical aggression does (Foster and Boch, 2024). Furthermore, even if threats to femininity produce feelings of anger, as in Foster and Boch (2024), there is no theoretical reason to presume that femininity threats would lead women to exhibit power and dominance over others. Whereas, anger-inspired acts of dominance and physical aggression have been suggested to appease threats to masculinity by reestablishing a man as “good” and powerful (Bosson et al., 2009; Vandello et al., 2008), dominance and physical aggression should not appease a threat to femininity because such acts violate femininity prescriptions and would not reestablish one as a good woman. From this perspective, even if women experience threats to femininity in some contexts, we would not predict linkages between femininity threats and attitudinal or behavioral acts of dominance. However, future work is need to more thoroughly test our prediction. Further work is also needed to understand the varied causes and consequences of threats to masculinity and femininity in relation to toxic intergroup relations.

Although a necessity given the focus of the present work, all participants in the present work were White men and women, leaving open questions regarding the causes and consequences of threats to masculinity among men with intersecting marginalized identities. Given the conceptualization of hegemonic masculinity, it argued that most people within a given culture endorse the hegemonic idealized notions of masculine. However, there are also critical differences in the content of hegemonic masculinity within and across groups and cultures (Hooks, 2004). Future research is needed to determine when members of marginalized groups internalize broader culturally idealized notions of masculinity vs. alternative masculinities and what factors predict those tendencies (e.g., ingroup identification).

In the United States, hegemonic masculine ideals historically have been and continued to be racialized and, as a result, may be more easily embodied when men are White, straight, able-bodied, and middle class, vs. members of marginalized masculinities (due to race, sexual orientation, religion, socio-economic status). As a result, it is not clear whether threats to masculinity would be similarly or differently associated with prejudicial forms of compensatory dominance among men whose intersecting identities render them members of groups that are marginalized or subordinated masculinities. Future research is needed to examine whether the content and consequences of dominance and prejudice toward people of marginalized races, marginalized religions, and immigrants would vary as a function of the intersecting race, ethnicity, culture, and socio-economic status of participants.

Despite limitations, the present theory and research is timely and important. As noted at the outset, masculinity has been a core component of national discourse about gender, race, and violence. The theoretical framework of hegemonic masculinity can illuminate those linkages, but core to that framework is the notion that idealized notions of masculinity are racialized. Also core to theorizing on hegemonic masculinity is the notion that the status-quo-maintaining acts of dominance and aggression that follow from threats to masculine ideas are directed toward women, as well as marginalized masculinities (e.g., men who are marginalized because of race, religion, nationality) and subordinate masculinities (e.g., gay men and trans men). For the status quo to remain stable across shifts in population, values, and crisis, masculinity as a cultural ideology may play a critical role in legitimating and justifying prejudice toward status-quo-threatening women, ethnic/racial groups, immigrants, and trans people, which is likely to be imbedded in the state and related institutions (e.g., MacKinnon, 1989). This work critically documents the relation between threats to internalized notions of hegemonic masculinity and explicit prejudice toward marginalized men, as well as women, which may support the dehumanization, dominance, and aggression toward marginalized men and women.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://osf.io/qk78p.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Pennsylvania State University IRB. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their implied informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TV: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KY-P: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. NS: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AL: Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Institutional funds from the University of Essex were granted to assist in the publication costs. The work was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE1255832, awarded to the second author. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2025.1494928/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Masculinity threat also been linked to anxiety (Vandello et al., 2008), however, this effect has not been consistently replicated (e.g., Berke et al., 2017).

2. ^For purposes unrelated to the scope of the present paper, participants also completed the 27-item Attitudes Toward Feminism Scale (Smith et al., 1975) using 7-point scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Items measured attitudes toward feminism that were both positive (e.g., “Women have the right to compete with men in every sphere of activity”) and negative (e.g., “A woman who refuses to bear children has failed in her duty to her husband”). After reverse-scoring positive items, we averaged across items to create an anti-feminist attitudes variable (α = 0.88). Analysis of this variable produced findings that paralleled those found on Islamophobia and Xenophobia (cultural threat, economic threat, and broad rejection).

References

Babl, J. D. (1979). Compensatory masculine responding as a function of sex role. J. Consult. Clini. Psychol. 47, 252–257. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.47.2.252

Bailey, A. H., LaFrance, M., and Dovidio, J.F. (2020). Implicit androcentrism: men are human, women are gendered. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 89:103980. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2020.103980

Bergh, R., Akrami, N., Sidanius, J., and Sibley, C. G. (2016). Is group membership necessary for understanding generalized prejudice? A re-evaluation of why prejudices are interrelated. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 113, 367–295. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000064

Berke, D. S., Reidy, D. E., Miller, J. D., and Zeichner, A. (2017). Take it like a man: gender-threatened men's experience of gender role discrepancy, emotion activation, and pain tolerance. Psychol. Men Masculin. 18, 62–69. doi: 10.1037/men0000036

Blodorn, A., O'Brien, L. T., Cheryan, S., and Vick, S. B. (2016). Understanding perceptions of racism in the aftermath of hurricane katrina: the roles of system and group justification. Soc. Just Res. 29, 139–158. doi: 10.1007/s11211-016-0259-9

Bosson, J. K., Vandello, J. A., Burnaford, R. M., Weaver, J. R., and Arzu Wasti, S. (2009). Precarious manhood and displays of physical aggression. Person Soc. Psychol. Bull. 35, 623–634. doi: 10.1177/0146167208331161

Brannon, R. (1976). “The male sex role: our culture's blueprint of manhood, and what it's done for us lately,” in The Forty-Nine Percent Majority: The Male Sex Role, eds. D. David and R. Brannon (Random House), 1–48.

Connell, R. W. (2003). Masculinities, change, and conflict in global society: thinking about the future of men's studies. J. Men's Stud. 11:249. doi: 10.3149/jms.1103.249

Courtenay, W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 50, 1385–1401. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00390-1

Dahl, J., Vescio, T., and Weaver, K. (2015). How threats to masculinity sequentially cause public discomfort, anger, and ideological dominance over women. Soc. Psychol. 46, 242–254. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000248

de Beauvoir, S. (2011). The Second Sex, 1st Edn. Transl. by C. Borde, and S. Malovany-Chevallier. Vintage. (Original work published 1949).

DeWall, C. N., Buchner, J. D., Lambert, N. M., Cohen, A. S., and Fincham, F. D. (2010). Bracing for the worst, but behaving the best: social anxiety, hostility, and behavioral aggression. J. Anxiety Disord. 24, 260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.12.002

Fischer, A. R., Tokar, D. M., Good, G. E., and Snell, A. F. (1998). More on the structure of male role norms. Psychol. Women Q. 22, 135–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1998.tb00147.x

Foster, S. D., and Boch, J. (2024). Feminine honor concerns, reactivity to femininity threats, and aggression in U.S. women. Curr. Psychol. 43, 6725–6738. doi: 10.1007/s12144-023-04875-9

French, J. R. P. Jr., and Raven, B. (1959). “The bases of social power,” in Studies in Social Power, ed. D. Cartwright (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan), 150–167.

Goff, P. A., Di Leone, B. A. L., and Kahn, K. B. (2012). Racism leads to pushups: how racial discrimination threatens subordinate men's masculinity. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48, 1111–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.03.015

Hammond, W. P., Fleming, P. J., and Villa-Torres, L. (2016). “Everyday racism as a threat to the masculine social self: framing investigations of African American male health disparities,” in APA Handbook of Men and Masculinities (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 259–283. doi: 10.1037/14594-012

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated mediation: quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 85, 4–40. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

Katz, I., and Hass, R. G. (1988). Racial ambivalence and American value conflict: correlational and priming studies of dual cognitive structures—ProQuest. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 55, 893–905. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.55.6.893

Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., and Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychol. Rev. 110, 265–284. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.110.2.265

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., and Bolger, N. (1998). “Data analysis in social psychology,” in The Handbook of Social Psychology, 4th Edn., Vol. 1. (McGraw-Hill), 233–265.

Konopka, K., Rajchert, J., Dominiak-Kochanek, M., and Roszak, J. (2021). The role of masculinity threat in homonegativity and transphobia. J. Homosexual. 68, 802–829. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2019.1661728

LeBreton, J. M., Wu, J., and Bing, M. N. (2009). “The truth(s) on testing for mediation in the social and organizational sciences,” in Statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends: Doctrine, Verity, and Fable in the Organizational and Social Sciences, eds. C.E. Lance and R. J. Vandenberg (Routledge), 109–144.

Lee, S. A., Gibbons, J. A., Thompson, J. M., and Timani, H. S. (2009). The Islamophobia scale: instrument development and initial validation. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 19, 92–105. doi: 10.1080/10508610802711137

Lesick, T. L., and Zell, E. (2021). Is affirmation the cure? Self-affirmation and European-Americans' perception of systemic racism. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 43, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2020.1811092

Liang, C. T. H., Salcedo, J., and Miller, H. A. (2011). Perceived racism, masculinity ideologies, and gender role conflict among Latino men. Psychol. Men Masculin. 12, 201–215. doi: 10.1037/a0020479

Maass, A., Cadinu, M., Guarnieri, G., and Grasselli, A. (2003). Sexual harassment under social identity threat: the computer harassment paradigm. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85, 853–870. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.853

Markus, H., and Oyserman, D. (1989). “Gender and thought: the role of self-concept,” in Gender and Thought: Psychological Perspectives, eds. M. Crawford, and M. Gentry (Springer), 100–127. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-3588-0_6

McCusker, M. G., and Galupo, M. P. (2011). The impact of men seeking help for depression on perceptions of masculine and feminine characteristics. Psychol. Men Masculin. 12, 275–284. doi: 10.1037/a0021071

Meuleman, B., and Billiet, J. (2012). Measuring attitudes toward immigration in Europe: the cross-cultural validity of the ESS immigration scales. Res. Methods 21, 5–29.

Pascoe, C. J. (2007). Dude, You're a Fag: Sexuality and Masculinity in High School. University of California Press.

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Rudman, L. A., and Fairchild, K. (2004). Reactions to counterstereotypic behavior: the role of backlash in cultural stereotype maintenance. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 87, 157–176. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.157

Rudman, L. A., Moss-Racusin, C. A., Phelan, J. E., and Nauts, S. (2012). Status incongruity and backlash effects: defending the gender hierarchy motivates prejudice against female leaders. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48, 165–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.10.008

Schermerhorn, N. E. C., and Vescio, T. K. (2021). Perceptions of a sexual advance from gay men leads to negative affect and compensatory acts of masculinity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 52, 260–279. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2775

Shrout, P. E., and Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 7, 422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

Smith, E., Ferree, M., and Miller, F. (1975). A scale of attitudes toward feminism. Represent. Res. Soc. Psychol. 6, 51–56.

Steiner, T. G., Vescio, T. K., and Adams, R. B. (2022). The effect of gender identity and gender threat on self-image. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 101:104335. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2022.104335

Thompson, E. H., and Pleck, J. H. (1986). The structure of male role norms. Am. Behav. Sci. 29:531. doi: 10.1177/000276486029005003

van der Veer, K., Yakushko, O., Ommundsen, R., and Higler, L. (2011). Cross-national measure of fear-based xenophobia: development of a cumulative scale. Psychol. Rep. 109, 27–42. doi: 10.2466/07.17.PR0.109.4.27-42

Vandello, J. A., Bosson, J. K., Cohen, D., Burnaford, R. M., and Weaver, J. R. (2008). Precarious manhood. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 95, 1325–1339. doi: 10.1037/a0012453

Vescio, T. K., and Schermerhorn, N. E. C. (2021). Hegemonic masculinity predicts 2016 and 2020 voting and candidate evaluations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, 1–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2020589118

Vescio, T. K., Schermerhorn, N. E. C., Gallegos, J. M., and Laubach, M. L. (2021). The affective consequences of threats to masculinity. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 97:104195. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104195

Vescio, T. K., Schermerhorn, N. E. C., Lewis, K. A., Yamaguchi-Pedroza, K., and Loviscky, A. J. (2023). Masculinity threats sequentially arouse public discomfort, anger, and positive attitudes toward sexual violence. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 51, 96–109. doi: 10.1177/01461672231179431

Vescio, T. K., Schlenker, K. A., and Lenes, J. G. (2010). “Power and sexism,” in The Social Psychology of Power, eds. A. Guinote and T. K. Vescio (The Guilford Press), 363–380.

Wade, J. C., and Brittan-Powell, C. (2001). Men's attitudes toward race and gender equity: the importance of masculinity ideology, gender-related traits, and reference group identity dependence. Psychol. Men Masculin. 2, 42–50. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.2.1.42

Warner, T. D., Tober, T. L., Bridges, T., and Warner, D. F. (2021). To provide or protect? Masculinity, economic precarity, and protective gun ownership in the United States. Sociol. Perspect. 61, 97–118. doi: 10.1177/0731121421998406

Weaver, K. S., and Vescio, T. K. (2015). The justification of social inequality in response to masculinity threats. Sex Roles J. Res. 72, 521–535. doi: 10.1007/s11199-015-0484-y

Wittlin, N. M., LaFrance, M., Dovidio, J. F., and Richeson, J. A. (2024). US cisgender women's psychological responses to physical femininity threats: increased anxiety, reduced self-esteem. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 110:104547. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2023.104547

Wong, Y. J., Tsai, P.-C., Liu, T., Zhu, Q., and Wei, M. (2014). Male Asian international students' perceived racial discrimination, masculine identity, and subjective masculinity stress: a moderated mediation model. J. Couns. Psychol. 61, 560–569. doi: 10.1037/cou0000038

Zarate, M.A., and Smith, E. R. (1990). Person categorization and stereotyping. Soc. Cogn. 8, 161–185. doi: 10.1521/soco.1990.8.2.161

Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., and Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 37, 197–206. doi: 10.1086/651257

Appendix

Keywords: masculinity threat, prejudice, racism, xenophobia, Islamophobia

Citation: Vescio TK, Yamaguchi-Pedroza K, Schermerhorn NEC and Loviscky AJ (2025) Threats to masculinity evoke status-quo-reinforcing racism, xenophobia, and Islamophobia. Front. Soc. Psychol. 3:1494928. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2025.1494928

Received: 11 September 2024; Accepted: 09 January 2025;

Published: 17 February 2025.

Edited by:

Rachel M. Calogero, Western University, CanadaReviewed by:

Christopher Petsko, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United StatesDiana Betz, Loyola University Maryland, United States

Copyright © 2025 Vescio, Yamaguchi-Pedroza, Schermerhorn and Loviscky. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nathaniel E. C. Schermerhorn, bnMyMzA3MUBlc3NleC5hYy51aw==

Theresa K. Vescio

Theresa K. Vescio Katsumi Yamaguchi-Pedroza

Katsumi Yamaguchi-Pedroza Nathaniel E. C. Schermerhorn

Nathaniel E. C. Schermerhorn Abigail J. Loviscky1

Abigail J. Loviscky1