- 1Institute of Communication Science, Friedrich-Schiller- University, Jena, Germany

- 2Diversity, Engagement and Discrimination, Institute for Democracy and Civil Society (IDZ), Jena, Germany

Introduction: While research on online hate speech (OHS) has expanded in recent years, only few studies adopt a theoretical framework to understand how ideological attitudes differentially motivate individuals to engage with OHS. Drawing on the dual-process motivational model of ideology and on previous political psychological research on OHS, this study examines how individual levels of social dominance orientation (SDO) and right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) predict the likelihood of producing OHS for online platforms users.

Methods: We used logistic regressions to analyze the survey data from a representative German sample of social media platform users (N = 7,349).

Results: The analyses indicate that SDO is related with higher odds of producing OHS, while RWA is related with lower odds. After adjusting for socio-economic factors and controlling for alternative predictors, the odd ratios remain significant, indicating that these two ideological attitudes predict online hate speech in different directions.

Discussion: The results show that high-RWA individuals are less likely to engage with OHS, which is explained through their conservative motivation to conform to social norms and maintain social stability. High-SDO individuals are more likely to produce OHS and may use it following their competitive motivation to increase hierarchical relations and improve their social status within society. The findings are discussed taking into consideration the specificities of the German social context, and corroborate and expand previous research. From these subtle but crucial differential effects, relevant implications are drawn for the platform as well as for social and political levels.

Introduction

In the last decade, the socio-political phenomenon of online hate speech (OHS) has been spreading so quickly that it reached policy makers before they were prepared to provide a political or a practical response. Research investigating OHS has been initiated in several fields, not only because an interdisciplinary approach is required to capture the multiple dimensions of the phenomenon, but also to keep pace with the fast technological and socio-political developments. Yet, online hate research appears disaggregated: the different approaches are rarely integrated with each other and often adopt very different definitions (Schweppe, 2021). Hate Speech is in fact difficult to define because its definitions are determined by the field of research as well as by the cultural contexts (Sellars, 2016; Schweppe, 2021; Schweppe and Perry, 2022). In the present study hate speech is defined drawing from Cohen-Almagor (2011) as “bias-motivated, hostile malicious speech aimed at a person or a group of people because of some of their actual or perceived innate characteristics. It expresses discriminatory, intimidating, disapproving, antagonistic, and/or prejudicial attitudes toward those characteristics, which include gender, race, religion, ethnicity, color, national origin, disability, or sexual orientation” (p. 1–2).

Most research on OHS has been focusing on content (Cohen-Almagor, 2018; Reichelmann et al., 2020), exposition (Hawdon et al., 2016; Bilewicz et al., 2017a; Soral et al., 2018; Savimäki et al., 2020; Schäfer et al., 2021) and victimization (Costello et al., 2016; Rasanen et al., 2016; Geschke et al., 2019), but not much is known on the perpetrators' side. So far, the perpetrators' perspective has mostly been investigated through the study of far-right groups and white supremacists in regard to racist content (Awan and Zempi, 2016; Jakubowicz, 2017; Cohen-Almagor, 2018; Bliuc et al., 2019; Jaki and De Smedt, 2019; Burke et al., 2020). A systematic literature review of research in the last thirty years (1992–2018) indicates that little is known about the psychosocial factors related with the use of OHS at an individual level (Tontodimamma et al., 2021). More recently, with the relevance of OHS growing worldwide, psychological research has started delving into the field using different approaches. A psychopathological approach showed that the dark triad of personality traits (narcissism, Machiavellianism and psychopathy) predicts the use of OHS (Frischlich et al., 2021). An interactionist approach was adopted in a representative sample to investigate different motives of gender based OHS (competition, control, punishment, retribution, image, justice and undeservingness), yet none of the analyzed motives significantly predicted the use of OHS (Mohseni, 2023). A social-cognitive approach has focused on social motives for engaging with OHS, such as social learning (Brady et al., 2021) and group-identity motivations (Brady et al., 2020). Lastly, a political-psychological approach provided evidence showing that ideological attitudes of right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) and social dominance orientation (SDO) predict the support for OHS prohibition from the observer point of view in opposing ways (Bilewicz et al., 2017a; Bilewicz and Soral, 2020): while RWA was a positive predictor of the support for OHS prohibition, SDO was a negative predictor.

The current study builds upon the work by Bilewicz et al. (2017a) and Bilewicz and Soral (2020) and adopts the dual process motivational model by Duckitt and Sibley (2009a) to examine the production of OHS from the perpetrator's perspective, corroborating and expanding previous research. The aim for this research is mainly to analyse whether and how the ideological attitudes of RWA and SDO motivate individuals to engage with OHS in different ways. The model allows us to theoretically understand which individuals are more likely to produce OHS, under which contextual circumstances and what personal and social goals are being pursued through the use of OHS.

Theoretical framework: right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and the dual process motivational model of ideology

Research on Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) and Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) has a long tradition in social and political psychology. Rather than personality traits, RWA and SDO are considered as ideological attitudes, belief systems or world views that implicate specific social cognitions and motivate social behaviors (Duckitt, 2001; Van Hiel et al., 2004; Duckitt and Sibley, 2009a,b). They are present to a certain extent in all individuals and across different cultures (see Pratto et al., 2000; Duriez et al., 2005; Duckitt and Sibley, 2009a,b, 2010; Ho et al., 2012). The following review of the literature on the two ideological attitudes sheds lights on the multidimensional system that RWA and SDO entail, highlighting their communal and differential characteristics.

The ideological attitude of RWA reflects three subdimensions, namely authoritarian submission, conventionalism and punitiveness against deviants and it is motivated by a fear of external threats that might alter a given order (Altemeyer, 1981, 1998; Duckitt, 2001; Van Hiel et al., 2004). The ideological attitude of SDO reflects the preference for more hierarchical rather than egalitarian social relations in which the own position is above the others, and it involves the two complementary sub-dimensions of dominance and (anti) egalitarianism (Pratto et al., 1994; Ho et al., 2012, 2015). Right-wing individuals usually report high levels of RWA and SDO, while individuals who consider themselves as politically “center” and “left” oriented mostly have lower levels. However, some work indicates that RWA and SDO are conceptually and empirically independent (Van Hiel et al., 2004, 2006; Duckitt and Sibley, 2009a,b). Research examining RWA and SDO indicates that the two conservative ideological attitudes capture distinct socio-political aspects (Altemeyer, 1998; Roccato and Ricolfi, 2005). RWA is positively associated with religiosity, valuing order, structure, and traditions, whereas SDO is not (Altemeyer, 1998; Duckitt, 2001). Differently from RWA, SDO is associated with valuing power and a social Darwinist view of the world. In regard to Schwartz's (1992) universal values model, RWA correlates with conservation values of security, conformity and tradition, while SDO correlates with self-enhancement values of power, achievement and hedonism (Duckitt, 2001; Duriez and Van Hiel, 2002). Duckitt and Sibley (2009a) developed the dual process motivational model to conceive the differential psychosocial mechanisms behind these ideological attitudes.

The dual process motivational model

According to Duckitt and Sibley (2009a), RWA and SDO result from the interplay of specific personality traits and characteristics of the social context, which induce related worldviews. These world views motivate individuals to similar yet differential conservative socio-political outcomes. In particular, RWA is the product of a social context that stresses dangers and threats, and of a personality that values social conformity rather than autonomy (Duckitt and Sibley, 2009a,b). Subsequent studies on personality traits showed that RWA individuals score high in conscientiousness and low in openness (Heaven and Bucci, 2001; Sibley and Duckitt, 2009). The combination of those personality and social threat induces the conception of the world as inherently dangerous which results in high RWA and, thus, the uncertainty-driven motivation to establish or maintain collective security through social cohesion, order, traditions, and norms. In a similar but distinct logic, SDO is the product of a social context that highlights competition over status, power and group dominance, and of a tough-minded personality (Sibley and Duckitt, 2009), with often low levels in agreeableness (Sibley and Duckitt, 2009; Heaven and Bucci, 2001). These elements determine a view of the world as a competitive jungle, enhance SDO and, thus, competition-driven motivational goals of establishing group dominance and superiority. While both RWA and SDO usually predict conservative socio-political behaviors, several studies showed that they often implicate qualitative differences regarding political voting behaviors, economic policies support, intolerance and legitimizing myths toward specific social groups. Namely, high-RWA individuals are more likely to vote for right-wing parties that call for traditional values and order (Duckitt and Sibley, 2009b), to support war in case of external attacks (McFarland, 2005) and to endorse prejudice against threatening social groups (Thomsen et al., 2008; Cohrs and Asbrock, 2009; Duckitt and Sibley, 2010). High-SDO are instead more likely to vote for parties that vouch for free market capitalism and anti-welfare policies (Duckitt and Sibley, 2009b), to support war for conquering purposes and regardless of the human costs (McFarland, 2005), and to endorse prejudice against derogated social groups (Thomsen et al., 2008; Cohrs and Stelz, 2010; Duckitt and Sibley, 2010). Longitudinal research (Sibley et al., 2007; Asbrock et al., 2010), cross-national research (Duckitt and Sibley, 2009b; Cohrs and Stelz, 2010) and experimental research (Dru, 2007; Cohrs and Asbrock, 2009) confirmed this theoretical reasoning and contributed to support the causal relations of the model.

RWA and SDO as predictors of online hate speech

Few but relevant studies in political psychology explored OHS through the ideological attitudes of RWA and SDO. Bilewicz et al. (2017a) investigated RWA and SDO as predictors of the support for prohibiting OHS. Their analyses revealed that while both ideological attitudes are positively related with outgroup prejudice, RWA individuals are in favor of OHS prohibition, whereas SDO individuals are instead against any limitation to OHS. The authors argued that high-RWA individuals might consider OHS as a severe violation of social norms, thus they would oppose to it. Further studies showed that desensitization (Soral et al., 2018), normativity (Soral et al., 2020), and the emotion of contempt (Bilewicz et al., 2017b) can predict the spread of OHS. Authoritarianism, empathy and a strong sense of social norms would instead prevent individuals from spreading OHS (Bilewicz et al., 2017a). Aggregating results from different studies on OHS, Bilewicz and Soral (2020) developed the “Hate Speech Epidemic Model” on the spread of OHS from the observer perspective. Based on this probabilistic model, the more individuals are exposed to OHS, the less they will be able to recognize OHS, and if they endorse high levels of contempt against outgroups, they will be highly likely to spread of OHS (Bilewicz and Soral, 2020). However, their model has been so far tested only through agent-based simulations and not through real world data. Our work can contribute to this body of research analyzing survey data to investigate the production of OHS through the ideological attitudes of RWA and SDO.

Hypotheses

The study builds its hypotheses upon the model by Duckitt and Sibley (2009a) and previous research conducted on the ideological attitudes and OHS (Bilewicz et al., 2017a; Bilewicz and Soral, 2020). Individuals with high levels of RWA are expected to be less likely to produce OHS, as they are assumed to follow their conservative motivation to maintain the social order and to conform to social norms. Individuals with high levels of SDO are expected to be more likely to produce OHS as an expression of their competitive motivation to achieve power and social status, exerting their dominance over other individuals.

Hyp.1: For individuals engaging with social media platforms, high-RWA will be related with lower odds of OHS production.

Hyp.2: For individuals engaging with social media platforms, high-SDO will be related with higher odds of OHS production.

The relations of RWA and SDO with the production of OHS should be independent of socio-economic factors.

Hyp.3: The differential relations of RWA and SDO with the odds of producing OHS will remain significant after adjusting for age, gender and education.

Since RWA and SDO are expected to constitute ideological attitudes intertwined with personality traits as well as with the social context, their relations with the production of hate speech are expected to remain robust beyond the effects of the alternative predictors of political attitude and outgroup prejudice, which are usually investigated as determinants of OHS (Awan and Zempi, 2016; Jakubowicz, 2017; Cohen-Almagor, 2018; Bliuc et al., 2019; Jaki and De Smedt, 2019; Bilewicz and Soral, 2020; Burke et al., 2020).

Hyp.4: The differential relations of RWA and SDO with the odds of perpetrating OHS will remain significant also after controlling for political attitude and for outgroup prejudice.

Methods

The study presents secondary statistical analyses conducted on the Hate Online data (Geschke et al., 2019). Logistic regressions were used to investigate the production of OHS. The data were collected by the research firm YouGov between April and May 2019 through a German representative online survey (CAWI) that focused on participants' perceptions of OHS, their personal experiences, its effects on targeted individuals and support for political measures against it. The sample targeted individuals living in Germany (N = 7,349) aged between 18 and 95. Representativity was ensured through statistical weights for age, gender, voting behavior (based on the 2017 national elections), education and population size (Geschke et al., 2019). The only criteria to take part in the online survey was to use online platforms (video platforms, advise platforms, blogs, forums, online news, Messenger or other chat services, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat, Pinterest, other social networks) at least once per week.

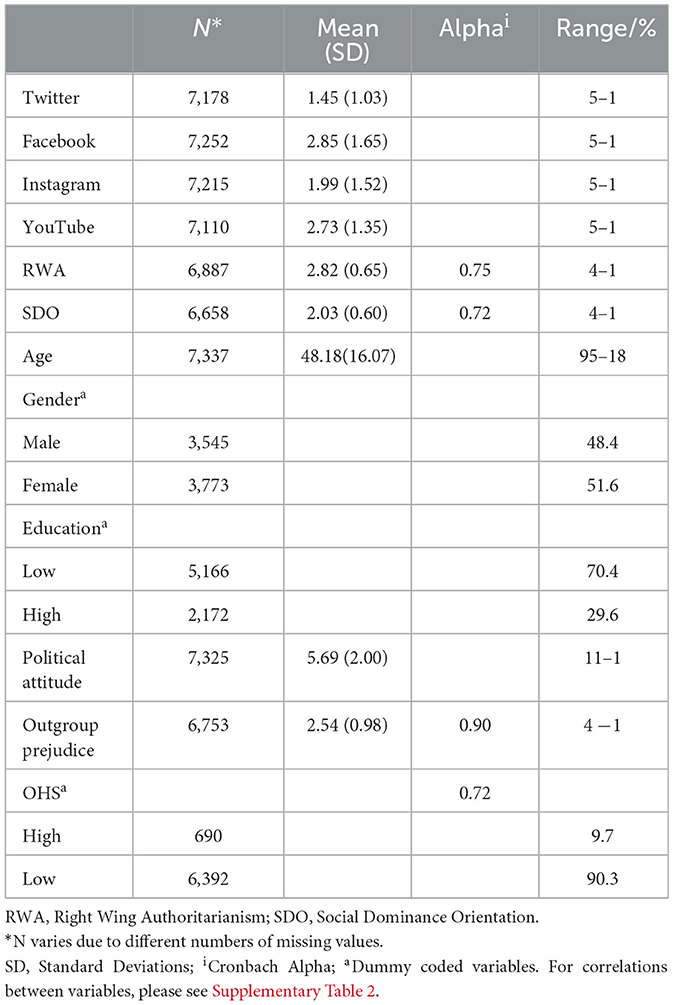

The production of Online Hate speech (OHS) is measured through two items (“I sometimes insult strangers online”; “I post things that I would not otherwise say”)1, replied on a four-point Likert scale (from 1 = “I disagree” to 4 = “I agree”). The items were combined into a reliable scale (α = 0.72), based on the mean (M = 1.32; SD = 0.62; N = 7,082). Due to the very high skewness of the variable, the scale was dichotomized for the analyses based on the cut-off point of 2.5 (cf. Table 1 for a summary of descriptives). Based on this measure, 9.7% respondents produce hate speech (n = 690).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of all scales and variables as inserted into the regression analyses.

Social Dominance orientation (SDO) is measured through five items (replied to on a 4-point Likert scale) based on Ho et al.'s (2012) measurement. The items were available in German (Cohrs et al., 2002). The two dimensions of dominance (e.g.: “To get ahead in life, it is sometimes necessary to have no regard for others”) and (anti)egalitarianism (e.g.: “All groups should have equal opportunities in life”; reverse item) are investigated. Right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) is assessed through six items (4-point Likert scale), based on previous German research (Heytmeyer and Heyder, 2002; Decker et al., 2016). The items examine the three sub-dimensions of aggression (e.g.: “In order to maintain law and order, there should be tougher action against outsiders and troublemakers”), submission (e.g., “People should leave important decisions in society to leaders”) and conventionalism (e.g., “Established behaviors should not be questioned”), with two items for each subscale. Both the RWA and SDO scales are built after checking for the internal consistency (RWA: α = 0.75; SDO: α = 0.72) and they are based on mean scores (RWA: M = 2.82, SD = 0.65; SDO: M = 2.03, SD = 0.60). The moderate, positive correlation between the two scales confirmed the independency of the scales (r = 0.24, p < 0.001)2.

Since a certain use of social media platforms constitutes a necessary condition to produce OHS, we inserted four variables to control for the engagement with the main social media platforms: Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube. The variables measure the frequency of use (on five points from “never” to “several times per week”) for each investigated platform, thus the resulting measures range from 1 to 5. Facebook and YouTube are used more widely in this sample, while Instagram and twitter are used to a lesser extent (see details in Table 1).

The variables of age, gender and educational level are inserted to adjust the analyses for the socio-economic status. Age is a continuous variable ranging from 18 to 95 and 25% of participants were aged below 35 years old (M = 48.2, SD = 16.02). 55.5% of participants identified themselves as male (N = 3,545). In regard to education, 29.6% of individuals hold a high-school degree (N = 2,172).

Political attitude and outgroup prejudice are included in the analyses to control for potential alternative predictors of OHS. Participants' political attitude is examined through a self-report measure, drawn from the European Social Survey (Schnaudt, 2016). Responses were based on a continuum from 1 to 11, whose extremes were named respectively as “left” and “right” (M = 5.69, SD = 2.0). Most of respondents considered themselves as “center” (60%). Outgroup prejudice is measured using three items from Zick et al. (2016) work on xenophobia in Germany. They investigate anti-migrants' attitudes, based on a four-point Likert scale (“There are too many immigrants living in Germany”; “Immigrants living in Germany are a burden for the Social State”; “Because of the many Muslims living in Germany I sometimes feel like stranger in my own country”). The scale was computed based on mean scores (M = 2.54; SD = 0.98; α = 0.89).

Based on the distribution of the OHS variable, logistic regressions were used to investigate the differential effects of SDO and RWA on the production of OHS. The independent variables were inserted through three hierarchical models.

Results

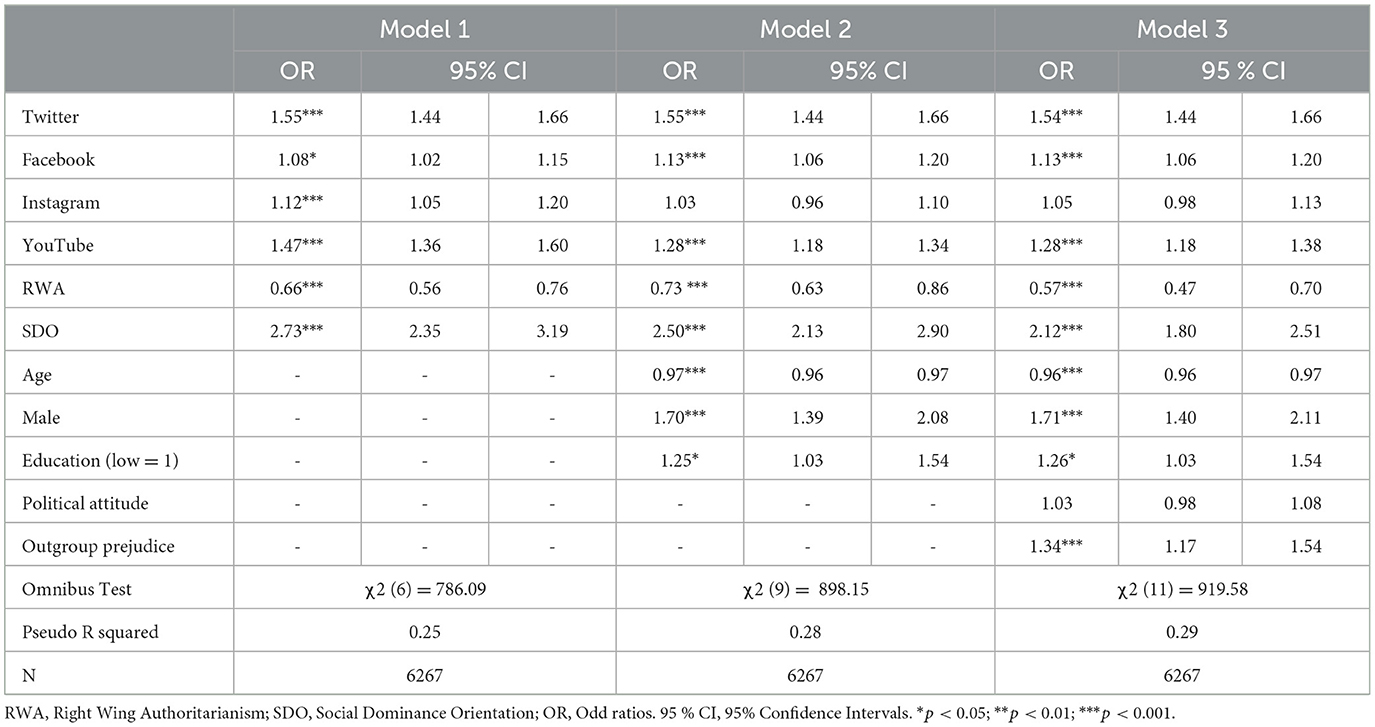

Hierarchical logistic regressions3 were performed to assess the impact of RWA and SDO on the likelihood of producing OHS (Table 2). The variables were inserted into the analyses through three models: the main independent predictors of RWA and SDO, followed by the control variable of social media platforms use (first model); the socio-economic variables of age, gender and education (second model); the potential alternative predictors of outgroup prejudice and political attitude (third model)4. The full model was statistically significant (Omnibus Test: χ2 (11, 6,267) = 919.584, p < 0.001) and it explained 29% of variance, correctly classifying 17% of cases of OHS production (OHS = 1)5.

For individuals engaging with social media platforms, high-RWA levels were significantly related with lower odds of producing OHS, while high levels of SDO were significantly associated with higher odds of OHS production. In particular, individuals scoring high on SDO resulted more than two times more likely to produce OHS, as compared to individuals with lower scores on SDO (SDO: OR = 2.73, 95% CI: 2.35–3.19). On the contrary, individuals with high levels of RWA resulted two times less likely to perpetrate OHS, in comparison to individuals with low levels of RWA (RWA: OR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.56–0.76). The first model explained most of the variance of OHS perpetration (25%), correctly identifying most of the cases of individuals scoring high on OHS (12.4%). The relations of RWA and SDO with the production of OHS slightly diminished in the second model, when adjusting for the socio-economic factors (RWA: OR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.63–0.86; SDO: OR = 2.50, 95% CI: 2.13–2.90). However, they remained significantly robust. The second model explained slightly more variance (28%) and a higher number of correctly identified cases (16%). After controlling for the alternative explanations of OHS, the relations of RWA and SDO with the odds of producing OHS decreased, but RWA and SDO remained the main significant predictors of OHS (RWA: OR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.47–0.70; SDO: OR = 2.12, 95% CI: 1.80–2.51). In fact, the third and final model only slightly increase the explained variance (29%) and the percentage of correctly identified cases (17%).

The individual socio-economic factors and control variables resulted mostly significantly related with the production of OHS. Namely, age was related with lower odds of OHS perpetration (age: OR = 0.96; 95 % CI: 0.96–0.97), while being male and having a lower education were related with higher odds of OHS, as compared to being female and having a higher education (male: OR = 1.71; 95% CI: 1.40–2.11; lower education: OR = 1.26; 95 % CI: 1.03–1.54). Concerning the potential alternative predictors of OHS, only outgroup prejudice resulted significantly related with higher odds of OHS (prejudice: OR = 1.34; 95 % CI: 1.17–1.54). Political attitude did not result significantly related with the production of OHS. (Political attitude: OR = 1.03; 95 % CI: 0.98–1.08). Results are discussed in depth in the next section.

Discussion

Logistic regressions were used to analyse how the ideological attitudes of RWA and SDO predict the production of OHS in a German representative sample. Duckitt and Sibley's (2009a) dual process motivational model was adopted to develop the hypotheses, expanding previous research in the field of political psychology. Overall, results confirmed the differential effects' hypotheses. High-RWA individuals were less likely to produce online hate speech, as compared with low RWA-levels (Hyp.1). On the contrary, high-SDO individuals were two times more likely to produce online hate speech, as compared with individuals with low levels of SDO (Hyp.2). The relations remained significant even after adjusting for socio-economic factors (Hyp.3) and after controlling for the effects of outgroup prejudice and political attitude (Hyp.4).

While the negative relation of RWA might appear counterintuitive, it corroborates several previous studies. Namely, RWA expresses the strong need for stability, the conformity to social norms and, accordingly, the rejection of “deviant” behaviors (Duckitt, 2006). For instance, the study by Thomsen et al. (2008) showed that high-RWA individuals develop aggressive intentions against migrants when those are perceived as “not willing to assimilate”, but they accept those who want to assimilate, differently from high-SDO individuals. High-RWA individuals are more likely to develop outgroup prejudice against social groups that are perceived as “dangerous” and threatening, but they usually do not include socio-economically disadvantaged groups in this category (Cohrs and Stelz, 2010; Duckitt and Sibley, 2010). In the current analyses, RWA and outgroup prejudice strongly correlated (see the Supplementary material)6, yet RWA was related with lower odds of producing OHS. Therefore, even though they endorse high levels of outgroup prejudice, high-RWA individuals might avoid engaging with OHS because it constitutes an overt violation of social norms. This is in line with Bilewicz et al.' findings on the positive relation between RWA and outgroup prejudice and the simultaneous support of RWA individuals to prohibit OHS (Bilewicz et al., 2017a), and the conception of authoritarianism as a protective factor against OHS (Bilewicz and Soral, 2020). In other terms, high-RWA individuals might choose not to overtly express their prejudice against minorities through OHS, following their conservative motivation (Stangor and Leary, 2006) to preserve the social order and conform to social norms (Duckitt and Sibley, 2009a). High-RWA individuals might in fact condemn individuals using OHS because they might be seen as breaking clear social norms.

High-SDO individuals, instead, are not hindered by social norms nor by the values of social order or stability. On the contrary, they are driven by strong competitive values, self-enhancement and achievement (Duckitt, 2001; Duriez and Van Hiel, 2002). They endorse prejudice against individuals that they perceive as “derogated”, as socio-economically disadvantaged groups who, according to them, take advantage of the social system (Cohrs and Stelz, 2010; Duckitt and Sibley, 2010). Differently from high-RWA individuals, high-SDO individuals are more likely to develop aggressive intentions against minorities who want to assimilate into the dominant culture (Thomsen et al., 2008). Namely, high-SDO individuals endorse a social Darwinist world-view in which the strong win and the weak lose (Duckitt and Sibley, 2009b). In fact, individuals with high levels of SDO are more likely to adopt Machiavellian strategies, thus justifying means by aims (Saucier, 2000). Thus, they could use OHS to exclude individuals of different social groups from the socio-economic competition for power and status. By disparaging social minorities, high-SDO individuals would not only ensure hierarchical intergroup relations and increased social inequality, but also gain higher status within society, according to their world-view.

Some considerations on the social context in which the data collection took place are necessary for both RWA and SDO. The German society has adopted a strong position against OHS (e.g., see NetzDG framework7), addressing OHS as a threat to social stability and cohesion. Obliging social media platforms to intervene more promptly, the German government and civil society strongly reinforced the social norms against hate speech. Such legal and societal efforts most likely have a positive impact on high-RWA individuals, strengthening their conformity to social norms and making them refrain from engaging with OHS. It is important to avoid interpreting these results in absolute terms, abstracted from the context. In fact, if no regulations condemning OHS are implemented and socio-political leaders followed by high-RWA individuals use hate speech against minorities, high-RWA individuals would most likely engage with OHS too. They might namely follow the behavior of their leaders, perceiving social minorities as threats for the societal order, and they might not perceive any inconsistency with the social norms that would otherwise prevent them from using OHS. Thus, it is likely that without these relevant conditions of the social context, the relation between RWA and OHS might differ. In the case of SDO, different consideration should be highlighted. Normative approaches have most likely little to no effect on high-SDO individuals, as their SDO competitive and Machiavellian world-views would allow them to act regardless of social norms and social opinion. High-SDO individuals are instead strongly influenced by socio-economic contexts that stress competition over status and power in every personal and social situation, and such contexts are overwhelmingly present in market-based societies. High-SDO individuals are particularly sensitive to the neoliberal values of self-interest, free and ruthless competition, financial success and (blind) meritocracy (Kasser et al., 2007; Amable, 2011; Littler, 2013; Bay-Cheng et al., 2015). For instance, the social comparative mechanisms induced by social media and the advertisement, the inflated competitive rules of the labor market, of educational settings and increasingly often of the social protection system (Kasser et al., 2007; Littler, 2013, 2018; Mirowski, 2013) are likely to elicite the competition-driven motivation of high-SDO individuals to prove the own superiority in the social and econominc competition. High-SDO individuals might therefore use OHS as a successful strategy to eliminate from the level playing field individuals belonging to social minorities, while increasing hierarchical relations and affirming their own status in society.

Lastly, most of the control variables behaved as expected, but some aspects deserve closer attention, starting from the alternative explanations of OHS of political attitude and outgroup prejudice. Political attitude did not result significally related with the odds of producing OHS. The explanatory power of the self-rated political attitude (left vs. right, measured on a scale from 1 to 11) might have been depicted by the scales of RWA and SDO; however, the correlations between RWA and SDO and the political attitude was only moderate (see the Supplementary material). Thus, this result also suggests that OHS is not attributable to right-wing “extremists” only. While outgroup prejudice is at the core of OHS and OHS is mostly defined as discriminatory speech against social minorities (e.g., Cohen-Almagor, 2011; Sellars, 2016; Schweppe, 2021; Schweppe and Perry, 2022), results confirm previous research indicating that prejudice endorsement represents a necessary, but not sufficient condition for producing OHS (Bilewicz et al., 2017a; Bilewicz and Soral, 2020; Frischlich et al., 2021; Mohseni, 2023). Regarding the sociodemographical factors, being male results instead one of the strongest predictors of OHS, corroborating research on gender-based OHS (Chetty and Alathur, 2018; Mechkova and Wilson, 2018; Döring and Mohseni, 2019; Frenda et al., 2019; Trindade, 2019; Dragotto et al., 2020; Powell et al., 2020; Castaño-Pulgarín et al., 2021) as well as research on the relation between SDO and sexism (Sidanius and Pratto, 2001; Sibley et al., 2007; Bay-Cheng et al., 2015). In conclusion, while social media platforms were inserted in the analyses as control variables, it is interesting to note that the links between the use of OHS and the use of different mainstream platforms are similar in size. In this German sample, despite the NetzDG entering in place in 2018 (see note 6), the link between OHS and Twitter and YouTube is strongest, followed by Facebook and Instagram. When adjusting for age, gender and education, Twitter and YouTube use are more strongly associated with OHS, followed by Facebook, while the relation between Instagram and OHS becomes instead not significant. However, this result could be affected by the time in which the data were collected: in 2019 a smaller percentage of German individuals had an Instagram account, in particular among those aged 35 or above8. In fact, the new version of the “Online Hate” Survey Project indicate that OHS in Germany has been mostly seen on Twitter/X, TikTok, Facebook and Instagram, and less frequently on YouTube (Bernhard and Ickstadt, 2024, p. 32).

Implications

The findings address some relevant implications. Focussing on the potential perpetrators, this study shows that among potential offenders, two groups differ in their likelihood of engaging with OHS in the 2019 German context. Namely, despite endorsing outgroup prejudice, RWA individuals are less likely to produce OHS and, as argued in the discussion, this is likely to be the case thanks to the environmental conditions that were put in place in Germany: social norms against OHS were strenghten through legal and societal efforts, such as the NetzDG and the many civil society campaigns. The results of this study support the adoption of this structural and societal approach to condemn and counteract OHS. On the contrary, since SDO individuals are more likely to produce OHS regardless of the societal norms and efforts, it is important to provide legal measures against OHS offenders, in particular for against those engaging with OHS against social minorities. Finally, it is crucial for governments and international bodies to demand that mainstream social media platforms take OHS seriously, as Germany has attempted to do in the last years. While the more frequently used platforms might change over time, as it has been the case in recent years with Instagram and TikTok, they will all to some extent provide space for OHS users. Therefore, social media platforms should by design facilitate actions against OHS, for example through easily accessible reporting mechanisms and effective deletion of OHS when reported. This would in fact limit the spread of OHS and strengthen the social norms against it.

Limitations and future research

Since the data were collected through an online survey, self-report biases might have influenced results. In particular, the OHS scale might have been subjected to social desirability biases. However, several studies used self-report measures (Rasanen et al., 2016; Wachs and Wright, 2018; Frischlich et al., 2021), also with more direct wording. In this case the indirect wording chosen to reduce the risks related to social desirability, limiting the likelihoods that participants respond in a moral conventional manner by lying about their actual behavior. Other studies have used vignette to capture the use of OHS (e.g., Mohseni, 2023), yet this methodology leads to ethical issues because individuals especially from minorities are differently affected by it. Therefore, the current solution represents a compromise between social desirability issues, ethical concerns and possibilities within a large representative sample, but future research should explore different methodologies. In addition, the current study adopts a general approach to OHS, which was defined here discriminatory speech as against minorities, however the analyses did not investigate it further in details. It is crucial for future studies to focus on OHS against gender minorities and sexual orientation, religious and racist speech to capture its specificities in nature, share and effects on minorities and on the broaden society. Lastly, as the digital sphere becomes a relevant complementary part of our working and social life (see Helsper, 2012; Bor and Petersen, 2021), future research should aim at examining actual hate speech data from online platforms and its effect on the online behavior. This is only possible through interdisciplinary work.

Conclusions

Focusing on the perpetrator's perspective, this study examined the relations of RWA and SDO with the production of OHS, drawing on Duckitt and Sibley's (2009a) Dual process motivational model and previous research on ideological attitudes and hate speech (Bilewicz et al., 2017a; Bilewicz and Soral, 2020). The multiple logistic regressions confirmed the differential effects of RWA and SDO on OHS for individuals engaging with Twitter, YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Results indicated that high-RWA individuals are less likely to engage with OHS and this is explained through their conservative motivation to conform to social norms. On the contrary, high-SDO individuals resulted more likely to produce OHS, which is in line with their competitive motivation of exerting power over other individuals to increase their social status within society. OHS could represent for high-SDO individuals a communicative strategy to eliminate other social groups from the socio-economic competition and demonstrate the own superiority. The differential relations remained significantly associated with the odds of producing OHS also after adjusting for socio-economic factors and controlling for the alternative explanations of outgroup prejudice and political attitude. The significant relations corroborate and expand previous research, indicating that RWA and SDO constitute ideological attitudes that predict similar yet different socio-political behaviors.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: The data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to bGF1cmEuZGVsbGFnaWFjb21hQGlkei1qZW5hLmRl.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because the study consists of an analysis of secondary data. The original data was published in 2019, by Geschke et al. (2019). The data was collected through a panel study by the research agency YouGov. All participants gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. The dataset is fully anonymized, individuals cannot be identified based on personalized information in the dataset. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LD: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Data curation, Methodology. DG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Writing—review & editing. TR: Supervision, Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. We acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation Projekt-Nr. 512648189 and the Open Access Publication Fund of the Thueringer Universitaets- und Landesbibliothek Jena. This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 861047.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2024.1389437/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The original items are as follows: ”Ich poste im Internet Sachen, die ich sonst nicht sagen würde.“; ”Manchmal beleidige ich fremde Personen im Internet.“

2. ^To ensure that RWA and SDO are measured as distinguished and independent scales, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted, and it indicated the presence of three independent factors. The first one was loading high on the items of RWA, while the second and third factors were loading high on the items of the two dimensions of SDO, respectively social dominance and anti-egalitarianism (see Supplementary Table 3 for the specific items and results of the factor analysis). These results confirmed the successful operationalisation of the different constructs and, thus, allowed for more in-depth analyses.

3. ^Variables were inserted stepwise into the regression analyses, following the hypotheses. Assumptions for logistic regressions were checked before the analyses (Field, 2013). There is potential for multicollinearity because outgroup prejudice and right-wing authoritarianism correlate at.58. However, the variance inflation factor (VIF) is 1.84, indicating that multicollinearity does not constitute an issue.

4. ^All results of individual models as well as correlations between all predictors can be read in the Supplementary material.

5. ^The percentage of correctly classified cases for the likelihood of not perpetrating OHS (OHS = 0) is 98.7%.

6. ^Before conducing the logistic regression, correlations were checked. A strong positive correlation between RWA and outgroup prejudice against migrants was found (r = 0.58**). The correlation between SDO and outgroup prejudice resulted positive but less strong (r = 0.44**). The VIF values allowed continuing with the analyses. All correlations can be observed in the Supplementary material.

7. ^The “Network Enforcement Act” (Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz, NetzDG) obligates social media platforms to remove illegal content within 24 h or within 7 days, depending on the extent of the damaging content. The official document is made available by the German Ministry of Justice: NetzDG.pdf (gesetze-im-internet.de).

8. ^In 2019 only 23.4% of the German population had an account on Instagram, while in 2024 the percentage increased to 41% and the new users are especially individuals aged 35 or above (Data from Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1021975/instagram-users-germany/).

References

Altemeyer, B. (1998). “The other “authoritarian personality”,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47–92. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60382-2

Amable, B. (2011). Morals and politics in the ideology of neo-liberalism. Socio-Econ. Rev. 9, 3–30. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwq015

Asbrock, F., Sibley, C. G., and Duckitt, J. (2010). Right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation and the dimensions of generalized prejudice: a longitudinal test. Eur. J. Pers. 24, 324–340. doi: 10.1002/per.746

Awan, I., and Zempi, I. (2016). The affinity between online and offline anti-Muslim hate crime: Dynamics and impacts. Aggress. Violent Behav. 27, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2016.02.001

Bay-Cheng, L. Y., Fitz, C. C., Alizaga, N. M., and Zucker, A. N. (2015). Tracking homo oeconomicus: development of the neoliberal beliefs inventory. J. Soc. Politi. Psychol. 3, 71–88. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v3i1.366

Bernhard, L., and Ickstadt, L. (2024). Lauter Hass – leiser Rückzug. Wie Hass im Netz den demokratischen Diskurs\bedroht. Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Befragung. Das NETTZ, Gesellschaft für Medienpädagogik und Kommunikationskultur, HateAid und Neue deutsche Medienmacher*innen als Teil des Kompetenznetzwerks gegen Hass im Netz (Hrsg.) (2024): Berlin.

Bilewicz, M., Kaminska, O., Winiewski, M., and Soral, W. (2017b). From disgust to contempt-speech: The nature of contempt on the map of prejudicial emotions. Behav Brain Sci. 40:e225. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X16000686

Bilewicz, M., and Soral, W. (2020). Hate speech epidemic. the dynamic effects of derogatory language on intergroup relations and political radicalization. Adv. Polit. Psychol. 41, 3–33. doi: 10.1111/pops.12670

Bilewicz, M., Soral, W., Marchlewska, M., and Winiewski, M. (2017a). When authoritarians confront prejudice. Differential effects of SDO and RWA on support for hate-speech prohibition. Polit.Psychol. 38, 87–99. doi: 10.1111/pops.12313

Bliuc, A.-M., Betts, J., Vergani, M., Iqbal, M., and Dunn, K. (2019). Collective identity changes in far-right online communities: the role of offline intergroup conflict. New Media Soc. 21, 1770–1786. doi: 10.1177/1461444819831779

Bor, A., and Petersen, M. B. (2021). The psychology of online political hostility: a comprehensive, cross-national test of the mismatch hypothesis. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 116, 1–18. doi: 10.1017/S0003055421000885

Brady, W. J., Crockett, M. J., and Van Bavel, J. J. (2020). The MAD model of moral contagion: the role of motivation, attention, and design in the spread of moralized content online. Persp. Psychol. Sci. 15, 978–1010. doi: 10.1177/1745691620917336

Brady, W. J., McLoughlin, K., Doan, T. N., and Crockett, M. J. (2021). How social learning amplifies moral outrage expression in online social networks. Sci. Adv. 7:eabe5641. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe5641

Burke, S., Diba, P., and Antonopoulos, G. A. (2020). ‘You sick, twisted messes': the use of argument and reasoning in Islamophobic and anti-Semitic discussions on Facebook. Discour. Soc. 31, 374–389. doi: 10.1177/0957926520903527

Castaño-Pulgarín, S. A., Suárez-Betancur, N., Vega, L. M. T., and López, H. M. H. (2021). Internet, social media and online hate speech. System. Rev. 58:101608. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2021.101608

Chetty, N., and Alathur, S. (2018). Hate speech review in the context of online social networks. Aggress. Violent Behav. 40, 108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.05.003

Cohen-Almagor, R. (2011). Fighting hate and bigotry on the internet. Policy & Internet 3, 89–114. doi: 10.2202/1944-2866.1059

Cohen-Almagor, R. (2018). Taking North American white supremacist groups seriously: the scope and the challenge of hate speech on the internet. Int. J. Crime, Justice Soc.Democr. 7, 38–57. doi: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v7i2.517

Cohrs, J. C., and Asbrock, F. (2009). Right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and prejudice against threatening and competitive ethnic groups. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 39, 270–289. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.545

Cohrs, J. C., Kielmann, S., Moschner, B., and Maes, J. (2002). Befragung zum 11. September 2001 und den Folgen: Grundideen, Operationalisierungen und deskriptive Ergebnisse der ersten Erhebungsphase. Bielefeld: Universität Bielefeld.

Cohrs, J. C., and Stelz, M. (2010). How ideological attitudes predict host society members' attitudes toward immigrants: exploring cross-national differences. J. Social Issues. 66, 673–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01670.x

Costello, M., Hawdon, J., and Ratliff, T. N. (2016). Confronting online extremism. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 35, 587–605. doi: 10.1177/0894439316666272

Decker, O. K., Kiess, J., and Brähler, E. (2016). Die enthemmte Mitte: Autoritäre und rechtsextreme Einstellung in Deutschland - Die Leipziger ”Mitte“ Studie 2016. Giessen: Psychosozial-Verlag.

Döring, N., and Mohseni, M. R. (2019). Fail videos and related video comments on YouTube: a case of sexualization of women and gendered hate speech? Commun. Res. Rep. 36, 254–264. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2019.1634533

Dragotto, F., Giomi, E., and Melchiorre, S. M. (2020). Putting women back in their place. Reflections on slut-shaming, the case Asia Argento and Twitter in Italy. Int. Rev. Sociol. 30, 46–70. doi: 10.1080/03906701.2020.1724366

Dru, V. (2007). Authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and prejudice: Effects of various self-categorization conditions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 43, 877–883. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2006.10.008

Duckitt, J. (2001). A dual-process cognitive-motivational theory of ideology and prejudice. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 33, 41–111. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(01)80004-6

Duckitt, J. (2006). Differential effects of right wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation on outgroup attitudes and their mediation by threat from and competitiveness to outgroups. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 32, 684–696. doi: 10.1177/0146167205284282

Duckitt, J., and Sibley, C. G. (2009a). A dual-process motivational model of ideology, politics, and prejudice. Psychol. Inq. 20, 98–109. doi: 10.1080/10478400903028540

Duckitt, J., and Sibley, C. G. (2009b). “A dual process motivational model of ideological attitudes and system justification,” in Social and Psychological Bases of Ideology and System Justification, ed. J. Thorisdottir (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 292–313.

Duckitt, J., and Sibley, C. G. (2010). Right–wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation differentially moderate intergroup effects on prejudice. Eur. J. Pers. 24, 583–601. doi: 10.1002/per.772

Duriez, B., and Van Hiel, A. (2002). The march of modern fascism, a comparison of social dominance orientation and authoritarianism. Pers. Individ. Dif. 32, 1199–1213. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00086-1

Duriez, B., Van Hiel, A., and Kossowska, M. (2005). Authoritarianism and social dominance in Western and Eastern Europe: the importance of the sociopolitical context and of political interest and involvement. Polit. Psychol. 26, 299–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00419.x

Frenda, S., Ghanem, B., Montes-Y-Gómez, M., and Rosso, P. (2019). Online hate speech against women: automatic identification of misogyny and sexism on Twitter. J. Intellig. Fuzzy Syst. 36, 4743–4752. doi: 10.3233/JIFS-179023

Frischlich, L., Schatto-Eckrodt, T., Boberg, S., and Wintterlin, F. (2021). Roots of incivility: How personality, media use, and online experiences shape uncivil participation. Media Commun. 9, 195–208. doi: 10.17645/mac.v9i1.3360

Geschke, D., Klaßen, A., Quent, M., and Richter, C. (2019). Hass im Netz: Der schleichende Angriff. Available online at: https://www.idz-jena.de/forschung/hass-im-netz-eine-bundesweite-repraesentative-untersuchung-2019 (accessed June 1, 2024).

Hawdon, J., Oksanen, A., and Räsänen, P. (2016). Exposure to online hate in four nations: a cross-national consideration. Deviant Behav. 38, 254–266. doi: 10.1080/01639625.2016.1196985

Heaven, P., and Bucci, S. (2001). Right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and personality: an analysis using the IPIP measure. Eur. J. Pers. 15, 49–56. doi: 10.1002/per.389

Helsper, E. (2012). A corresponding fields model for the links between social and digital exclusion. Commun. Theory 22, 403–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2012.01416.x

Heytmeyer, W., and Heyder, A. (2002). “Autoritäre Haltungen,” in Deutsche Zustände, ed. W. Heitmeyer. (Berlin: Suhrkamp), 59–81.

Ho, A. K., Sidanius, J., Kteily, N., Sheehy-Skeffington, J., Pratto, F., Henkel, K. E., et al. (2015). The nature of social dominance orientation: theorizing and measuring preferences for intergroup inequality using the new SDO(7) scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 109, 1003–1028. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000033

Ho, A. K., Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., Levin, S., Thomsen, L., Kteily, N., et al. (2012). Social dominance orientation: revisiting the structure and function of a variable predicting social and political attitudes. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 38, 583–606. doi: 10.1177/0146167211432765

Jaki, S., and De Smedt, T. (2019). Right-wing german hate speech on twitter: analysis and automatic detection. arXiv [Preprint]. arXiv:1910.07518. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1910.07518

Jakubowicz, A. H. (2017). Alt_Right white lite: trolling, hate speech and cyber racism on social media. Cosmopol. Civil Soc.: An Interdiscipl. J. 9, 41–60. doi: 10.5130/ccs.v9i3.5655

Kasser, T., Cohn, S., Kanner, D., and Ryan, R. M. (2007). Some costs of american corporate capitalism: a psychological exploration of value and goal conflicts. Psychol. Inquiry 18, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/10478400701386579

Littler, J. (2013). Meritocracy as plutocracy: the marketising of ‘equality' within neoliberalism. New Format. 80–81, 52–72. doi: 10.3898/NewF.80/81.03.2013

Littler, J. (2018). Against Meritocracy: Culture, Power and Myths of Mobility. London and New York: Routledge.

McFarland, S. G. (2005). On the eve of war: authoritarianism, social dominance, and American students' attitudes toward attacking Iraq. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 31, 360–367. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271596

Mechkova, V., and Wilson, S. L. (2018). Norms and rage: Gender and social media in the 2018 U.S. mid-term elections. Elect. Stud. 69:102268. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102268

Mirowski, P. (2013). Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown. London: Verso.

Mohseni, M. R. (2023). Motives of online hate speech: results from a quota sample online survey. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Network. 26, 499–506. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2022.0188

Powell, A., Scott, A. J., and Henry, N. (2020). Digital harassment and abuse: Experiences of Sexuality and gender minority adults. Eur. J. Criminol. 17, 199–223. doi: 10.1177/1477370818788006

Pratto, F., Liu, J. H., Levin, S., Sidanius, J., Shih, M., Bachrach, H., et al. (2000). Social dominance orientation and the legitimationof inequality across cultures. J. Cross-Cultural Psychol. 31, 369–409. doi: 10.1177/0022022100031003005

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., and Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 67, 741–763. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741

Rasanen, P., Hawdon, J., Holkeri, E., Keipi, T., Nasi, M., and Oksanen, A. (2016). Targets of online hate: examining determinants of victimization among young finnish Facebook users. Violence Vict. 31, 708–726. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-14-00079

Reichelmann, A., Hawdon, J., Costello, M., Ryan, J., Blaya, C., Llorent, V., et al. (2020). Hate knows no boundaries: online hate in six nations. Deviant Behav. 42, 1100–1111. doi: 10.1080/01639625.2020.1722337

Roccato, M., and Ricolfi, L. (2005). On the correlation between right-wing RWA AND SDO authoritarianism and social dominance orientation. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 27, 187–200. doi: 10.1207/s15324834basp2703_1

Saucier, G. (2000). Isms and the structure of social attitudes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 78, 366. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.366

Savimäki, T., Kaakinen, M., Räsänen, P., and Oksanen, A. (2020). Disquieted by online hate: negative experiences of finnish adolescents and young adults. Eur. J. Crimi. Policy Res. 26, 23–37. doi: 10.1007/s10610-018-9393-2

Schäfer, S., Michael, S., and Reiners, L. (2021). Hate speech as an indicator for the state of the society. J. Media Psychol. 34, 3–15. doi: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000294

Schnaudt, C. (2016). Country-Specific, Cumulative ESS Data Set for Germany 2002-2014 (ESSDE1-7e01). Available online at: https://stessrelpubprodwe.blob.core.windows.net/data/round8/survey/ESS8_appendix_a7_e01_1.pdf (accessed June 20, 2024).

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 25, 1–65. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60281-6

Schweppe, J. (2021). What is a hate crime? Cogent Soc. Sci. 7:1902643. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2021.1902643

Schweppe, J., and Perry, B. (2022). A continuum of hate: delimiting the field of hate studies. Crime, Law Social Change 77, 503–528. doi: 10.1007/s10611-021-09978-7

Sibley, C. G., and Duckitt, J. (2009). Big-five personality, social worldviews, and ideological attitudes: further tests of a dual process cognitive-motivational model. J. Soc. Psychol. 149, 545–561. doi: 10.1080/00224540903232308

Sibley, C. G., Wilson, M., and Duckitt, J. (2007). Effects of dangerous and competitive worldviews on Roght-Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation over a Five-Month Period. Polit. Psychol. 28:2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2007.00572.x

Sidanius, J., and Pratto, F. (2001). Social Dominance: An intergorup theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Soral, W., Bilewicz, M., and Winiewski, M. (2018). Exposure to hate speech increases prejudice through desensitization. Aggress. Behav. 44, 136–146. doi: 10.1002/ab.21737

Soral, W., Liu, J. H., and Bilewicz, M. (2020). Media of comtempt: social media consumption predicts normative acceptance of anti-muslim hate speech and islamoprejudice. Int. J. Conflict Viol. 14:2020. doi: 10.4119/ijcv-3774

Stangor, C., and Leary, S. P. (2006). Intergroup beliefs: investigations from the social side. Adv. Exp. Social Psychol. 38, 243–281. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38005-7

Thomsen, L., Green, E. G. T., and Sidanius, J. (2008). We will hunt them down: How social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism fuel ethnic persecution of immigrants in fundamentally different ways. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 44, 1455–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2008.06.011

Tontodimamma, A., Nissi, E., Sarra, A., and Fontanella, L. (2021). Thirty years of research into hate speech: topics of interest and their evolution. Scientometrics 126, 157–179. doi: 10.1007/s11192-020-03737-6

Trindade, L. V. P. (2019). Disparagement humour and gendered racism on social media in Brazil. Ethnic Racial Stud. 43:1689278 doi: 10.1080/01419870.2019.1689278

Van Hiel, A., Duriez, B., and Kossowska, M. (2006). The presence of Left-Wing Authoritarianism in Western Europe and its relationship with conservative ideology. Polit. Psychol. 2007, 769–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00532.x

Van Hiel, A., Pandelaere, M., and Duriez, B. (2004). The impact of need for closure on conservative beliefs and racism: differential mediation by authoritarian submission and authoritarian dominance. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 30, 824–837. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264333

Wachs, S., and Wright, M. F. (2018). Associations between bystanders and perpetrators of online hate: the moderating role of toxic online disinhibition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15:2030. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15092030

Keywords: online hate speech, right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, social context, social media platforms

Citation: Dellagiacoma L, Geschke D and Rothmund T (2024) Ideological attitudes predicting online hate speech: the differential effects of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2:1389437. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2024.1389437

Received: 21 February 2024; Accepted: 11 June 2024;

Published: 02 July 2024.

Edited by:

Natalie Shook, University of Connecticut, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Dellagiacoma, Geschke and Rothmund. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura Dellagiacoma, bGF1cmEuZGVsbGFnaWFjb21hQGlkei1qZW5hLmRl

Laura Dellagiacoma

Laura Dellagiacoma Daniel Geschke2

Daniel Geschke2