- 1Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota Duluth, Duluth, MN, United States

- 2Department of Psychological Science, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, United States

- 3Department of Sociology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, United States

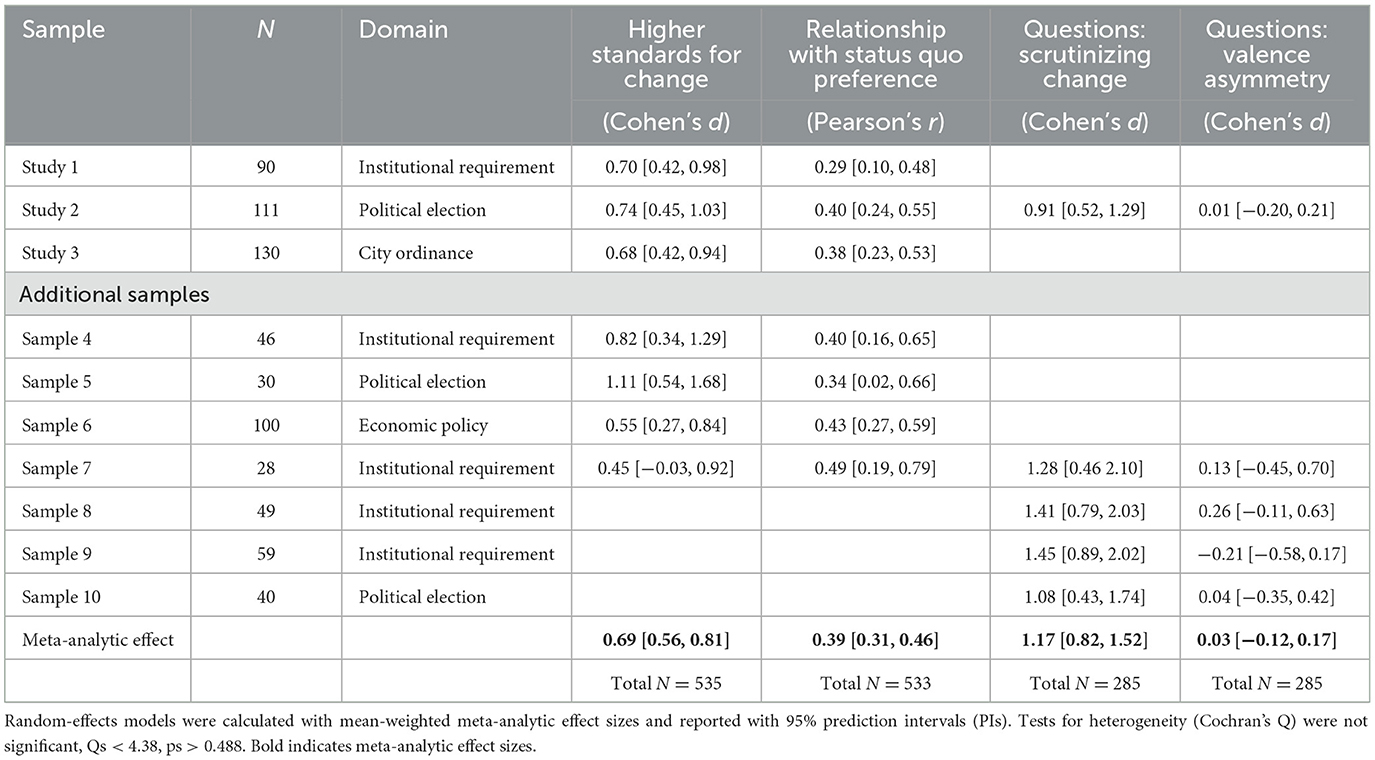

Three studies demonstrate that, all else being equal, the threshold for justifying social change is higher than the threshold for maintaining the status quo. Higher standards for justifying change were observed across institutional requirements (Study 1), political candidates (Study 2), and city ordinances (Study 3). In all studies, lopsided standards increased as status quo preference increased. Study 1 revealed higher standards for novel entities lacking precedence, Study 2 demonstrated increased information-seeking about non-status quo alternatives to scrutinize them, and Study 3 showed biased interpretation of evidence toward maintaining the status quo, even when evidence skewed toward advocating change. The robustness of higher standards for change (d = 0.69; k = 7, N = 535), its relationship with status quo preference (r = 0.39; k = 7, N = 533), and information seeking scrutinizing alternatives (d = 1.17; k = 5, N = 285), rather than confirmation bias (d = 0.03; k = 5, N = 285), was established via small-scale meta-analyses including all data collected for this research program. Implications for theories of social change vs. status quo maintenance are discussed.

Introduction

Investigations of status quo maintenance usually emphasize people's attempts to justify and defend what exists (e.g., Jackman, 1994; Major, 1994; Jost et al., 2004; Kay et al., 2009). People endorse or provide reasons for why the way things are is good, legitimate, and the way things ought to be. In the present research, we take a different approach by focusing on alternatives to the status quo and emphasize the difficulty of justifying change rather than maintaining the status quo. People need few reasons, if any, to stay with what is established, but deviating from the status quo requires compelling evidence. The standards—that is, the amount or quantity of reasons, vetting, and evidence—that must be met to justify change to an alternative are higher than those necessary to justify what is already in place.

Higher standards for justifying change

We argue that the extra justification needed for change is a corollary of the assumptions people make about the status quo relative to its alternatives. People are partial to what is familiar and hence assumed safe (Zajonc, 1968; Harrison, 1977; Bornstein, 1989). They intuit that what “is” is “good” (Eidelman et al., 2009; Cimpian and Salomon, 2014; Eidelman and Crandall, 2014) and longer existence signifies vetting and merit (Eidelman et al., 2010; Blanchar and Eidelman, 2013, 2021). People often prefer to do nothing because it is easier (Samuelson and Zeckhauser, 1988; Anderson, 2003) and because they are averse to risk, loss, and regret (Kahneman et al., 1991; Ritov and Baron, 1992; Moshinsky and Bar-Hillel, 2010). People may also be motivated to justify the status quo to defend their own situations and the system as a whole (Jost et al., 2004; Kay et al., 2009; Jost, 2019). To mitigate the uncertainty and potential hazards associated with change, people often opt to maintain the current situation, flawed though it may be, rather than face an uncertain future. For all these reasons, people should show bias favoring the status quo while adopting a more critical stance toward its alternatives.

When people anticipate or desire a specific conclusion, they often demand greater and more compelling evidence for any alternative (Ditto and Lopez, 1992) and typically exhibit biased information processing, interpreting data selectively to align with their expectations (Kunda, 1990; Ditto et al., 1998; Hart et al., 2009). In fact, people seem to consider different things when they have a priori preferences and expectations. Those wishing to reject a proposition ask themselves whether they “must” accept it, whereas those wanting to affirm it ask whether they “can” accept it (Gilovich, 1991; see also Dawson et al., 2002). The threshold, or minimum level of evidence required, for reaching a particular judgment is higher in the former case. In the present context, people's relative suspicion and dislike for alternatives to the status quo should compel them to set a higher threshold for accepting change. These higher standards make it easier to reject change in favor of retaining the status quo.

Higher standards for change could be due to raising the “bar” for alternatives or lowering it for the status quo. Although not mutually exclusive, we suggest the former process may be dominant. First, because the inertia of existence is assumed to signify successful vetting (Tworek and Cimpian, 2016; Blanchar and Eidelman, 2021), the status quo does not require scrutiny, whereas alternatives represent a pivot toward the unknown that requires extra attention and inspection. Second, calls for social change are construed as more self-interested than keeping the status quo in place (O'Brien and Crandall, 2005). It would be reasonable for people to be suspicious of change, applying more scrutiny to and requiring higher thresholds of evidence for alternatives, if they suspect improper or superfluous motives. Finally, alternatives are evaluated less favorably than the status quo (Eidelman and Crandall, 2014) and unfavourability motivates heightened skepticism, wherein people require stronger evidence to accept conclusions they do not desire or expect (Ditto and Lopez, 1992; Taber and Lodge, 2006). In sum, people should raise standards for justifying change more than lowering standards for retaining the status quo.

This is a unique formulation of how even modest inclinations toward the status quo can translate into the rejection of change. As noted, previous research contends that people cast-off change because they rationalize and defend the status quo as good and better than its alternatives (e.g., Jost et al., 2004; Kay et al., 2009). Our approach distinctively considers how people treat alternatives to the status quo; they apply higher standards when evaluating whether there is justification for enacting change. This does not assume the status quo is “good” or even “superior” to its alternatives, merely that judgment criteria selectively shift to disadvantage alternatives representing change (see Miron et al., 2010, for a similar process).

Seeking and interpreting evidence

Considering change requires seeking and interpreting information about the status quo and its alternatives. We contend that higher standards for justifying change should prejudice which information people prioritize and how they interpret evidence.

Although one might expect perceivers to adopt a confirmatory strategy by selectively exposing themselves to favorable information about the status quo and unfavorable information about its alternatives (Nickerson, 1998; Hart et al., 2009; Fischer and Greitemeyer, 2010), higher standards for justifying change may instead encourage a strategy of selectively scrutinizing alternatives. Specifically, people may prioritize information about alternatives to maximize the potential of discovering flaws and limitations (Liberman and Chaiken, 1992; Ditto et al., 1998; Dawson et al., 2002). For example, gamblers spend more attention and effort explaining away their losses than discussing their wins (Gilovich, 1983), partisans more thoroughly examine uncongenial positions and find ways to discount them (Lord et al., 1979; Taber and Lodge, 2006), and high prejudice individuals show better memory for stereotype-inconsistent information because they engage effortful processing to reconcile it with their existing beliefs (Sherman et al., 2005). Whereas, status quo options are likely to be accepted at face value, alternatives representing change are put to the test to resolve uncertainty and uncover costly deficiencies.

We tested these competing perspectives by adapting an information seeking paradigm based on Snyder and Swann (1978). Participants selected from a list of questions, each crafted to convey positive or negative information about the status quo or its alternative. This allowed participants the flexibility to choose questions affirming the superiority of the status quo or disproportionately scrutinizing change to an alternative. If confirmation bias is guiding the information search process, people will opt for more positively valanced questions targeting the status quo and negatively valanced questions targeting its alternative. Conversely, if selective scrutiny is the operating strategy, people will prioritize information about alternatives—good and bad—in service of exposing potential flaws and faults.

Another important consideration is how decision makers interpret information once available. If people raise standards for justifying change from the status quo to an alternative, then it will be more difficult to see the value of change over status quo maintenance. Even when evidence indicates that the status quo and its alternative are on equal footing, there should be insufficient justification for change. Furthermore, ambiguity is fertile ground for bias (Kunda, 1990), and tends to be perceived in ways that fit with what is desired and expected (Lord et al., 1979; Dunning, 1993; Balcetis and Dunning, 2006). Justification for change should fall short in the presence of ambiguous or mixed evidence and only receive serious consideration when alternatives have clear support over and above that which represents the status quo. Said differently, we argue that, to justify change, evidence favoring alternatives will need to be much stronger than any evidence favoring the status quo.

The present research

We tested these ideas in three studies. Study 1 investigated raised standards for alternatives representing change. Participants considered two institutional requirements, varied with respect to which represented the status quo, or, in a third condition, a true status quo was lacking. In all, participants reported the standards that needed to be met to justify using each institutional requirement. Study 2 investigated bias in information seeking strategies. In the context of a political election, participants indicated the standards necessary to stay with an incumbent running for reelection or change to the challenger and then completed an information seeking task to discern between strategic confirmation bias favoring the status quo and selective scrutinization of alternatives. Study 3 investigated bias in interpreting evidence. We manipulated which of two city ordinances represented the status quo and measured standards for and preferences between the alternative and status quo. Participants then considered evidence favoring the status quo, the alternative, or mixed evidence before indicating the justification for maintaining the status quo or adopting the alternative. We used the “simr” package in R (Green and MacLeod, 2016; R Core Team, 2024) to determine the sample sizes needed to detect a moderate-to-large effect size of standards (d = 0.69; based on additional samples available in online materials) with 80% power. These simulations indicated that samples of 104, 84, and 38 were required in Studies 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Our data analytic approach utilized linear mixed-effects models with responses nested within participants; this method was chosen for its enhanced flexibility, accuracy, and statistical power compared to traditional repeated-measures ANOVA (Magezi, 2015). Finally, we conducted a series of small-scale meta-analyses, including effect sizes from these three studies as well as data from seven additional samples we collected during this research program. All measures, manipulations, and exclusions are disclosed for each study, with materials and data accessible online via Open Science Framework.

Study 1

Study 1 tested our hypothesis that higher standards are necessary to justify change to an alternative of the status quo. Participants read about a potential change to degree requirements at their university and then evaluated the options (adapted from Eidelman et al., 2009), and we counterbalanced which requirement represented the status quo vs. its alternative. Participants reported the standards that needed to be met to justify keeping the status quo in place and to justify change to an alternative. We operationalized standards as the amount and quality of evidence necessary to justify or permit each decision option. If the status quo is indeed allotted a standards advantage, participants should set lopsided standards that favor retaining the existing degree requirement; the standards for justifying change to the alternative degree requirement should be higher and more difficult to meet. Additionally, a third condition allowed us to test whether the standards were being relaxed for the status quo or raised for its alternatives by having participants consider the degree requirements for a new academic program that lacked a true status quo. In this comparison condition, participants judged the standards necessary to implement each of these two institutional requirements, neither of which currently represented the status quo but both had precedence in other programs.

Method

Participants

A sample of 137 undergraduates (92 female; Mage = 19.34, SD = 2.90) was recruited to participate in a study on “student opinions” in exchange for partial fulfillment of a course requirement.

Procedure and materials

Participants were randomly assigned to complete one of three versions of a questionnaire about a degree requirement at their university (for details, see Supplementary material). Two versions of the questionnaire concerned a potential change to an existing requirement but stipulated that current students would not be affected. Half of these participants were led to believe the existing requirement was 32 credit hours within one's major with a possible change to 38 credit hours because it would afford students greater expertise, and the other half were led to believe the status quo was 38 credit hours within the major with a possible change to 32 credit hours because it would afford students a greater breadth of knowledge. In a third version (control condition), participants were told that university officials were developing a new degree program and deciding between a requirement of 32 or 38 credit hours within the major to graduate, but that other degree programs within the university varied in this requirement such that some employed 32 credit hours and others 38 credit hours. Following Eidelman et al. (2009), participants were told this new program would be implemented in 10 years and thus would not affect current students.

Participants indicated their agreement with six items on 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree) response scales. Three items asked about the standards necessary to justify using 32 credit hours for the degree requirement (“Few reasons would be needed to use the requirement of 32 credit hours” (reversed), “Strong reasons would be needed to use the requirement of 32 credit hours,” and “I think a number of reasons would be necessary to use the requirement of 32 credit hours;” α = 0.84). The same three items were re-worded to ask participants about the standards necessary to justify using 38 credit hours as the requirement (α = 0.84). Evaluative preference was assessed via three items in which participants indicated which requirement is “good,” “right,” and “the way things ought to be” (1 = 32 credit hours, 9 = 38 credit hours; α = 0.87).

Results

Standards

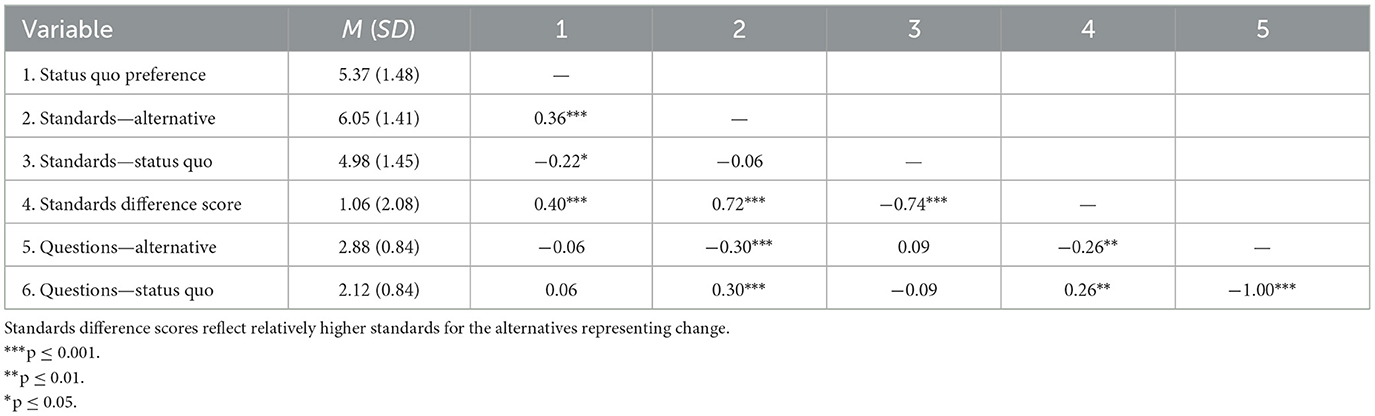

We fit a linear mixed model with random intercepts of participant using the “lme4” (Bates et al., 2015) and “lmerTest” packages (Kuznetsova et al., 2017) in R to estimate the fixed effects of institutional requirement (32 vs. 38 credit hours), existing practice (status quo, alternative, or control), and their interaction on standards setting. The model yielded a significant main effect of existing practice, F(2, 267.49) = 14.20, p < 0.001 (Figure 1). No main effect of institutional requirement emerged, F(1, 134) = 0.10, p = 0.752, nor did it interact with existing practice, F(2, 167.86) = 1.40, p = 0.249. Participants set higher standards for justifying an institutional requirement that represented change (M = 6.36, SD = 1.45) compared to when it represented the status quo (M = 5.34, SD = 1.46), b = 1.03, SE = 0.20, t = 5.16, p < 0.001, 95% CI for difference [0.63, 1.42], or when no true status quo was available in the control condition (M = 5.56, SD = 1.68), b = 0.81, SE = 0.24, t = 3.36, p < 0.001, 95% CI for difference [0.33, 1.28]. In contrast, they applied equivalent standards in the control condition and for justifying institutional requirements that represented the status quo, b = 0.22, SE = 0.24, t = 0.92, p = 0.361, 95% CI for difference [−0.25, 0.69].

Figure 1. Standards for justifying an institutional requirement as a function of existing practice and its content. Error bars: SEs.

Evaluation

An omnibus ANOVA for evaluation was not significant, F(2, 134) = 0.42, p = 0.659. Preference between the 32- and 38-credit hour options did not vary across existing practice condition (status quo: M = 5.27, SD = 2.21; alternative: M = 5.50, SD = 2.03; control: M = 5.12, SD = 1.81).

Relationship with status quo preference

Exempting participants in the control condition where no true status quo was available (n = 47), we computed difference scores reflecting the degree of preference and relative standards for maintaining the current institutional requirement over change to an alternative, with positive scores indicating a stronger status quo preference and higher standards for change, respectively. Status quo preference predicted higher standards for justifying change to an alternative, r = 0.29, p = 0.006.

Discussion

Data from Study 1 support our prediction that people require greater justification for change than maintaining the status quo. Although participants overall did not prefer whichever requirement was said to be in place, status quo preference was positively correlated with higher standards for justifying change. As status quo preference increased, so, too, did the threshold necessary for sanctioning change. Additionally, a comparison condition lacking a true status quo—that is, with no existing requirement from which to deviate—provided evidence that standards are raised when considering change to an alternative rather than relaxed to preserve the status quo. The standards applied to a degree requirement that was not currently in place but had precedence in other programs was equivalent to the standards applied when it represented the status quo. In contrast, when this degree requirement represented change from a true status quo, participants required higher standards. It is worth noting, however, that participants may have perceived the control condition as more akin to a variant of the 'status quo,' potentially reducing their apprehension toward both requirements. Refining the control condition to better reflect a neutral baseline could benefit future studies.

Study 2

Study 1 provided initial evidence for raising the standards that need to be met to justify change. In Study 2, we again tested whether people set relatively higher standards for alternatives representing change, but also examined consequences for information seeking strategies. People may adopt a strategy centered on confirming the status quo as better and more desirable (Nickerson, 1998) or one centered on prioritizing information about its alternatives in service of applying critical scrutiny (Dawson et al., 2002). We tested these possibilities in the context of a political election, varying which candidate represented the incumbent (i.e., status quo) and then measuring the standards participants apply to each candidate and their relative preference between the candidates. Participants also completed an information seeking task that allowed them to select a subset of questions likely to yield positive or negative information about the incumbent or their challenger. If participants are employing a confirmatory strategy, they should select more positive-affirming questions about the incumbent and more negative-affirming questions about the challenger (Snyder and Swann, 1978). However, if participants are employing a strategy of critically scrutinizing alternatives to the status quo, they should prioritize information about the challenger to maximize opportunities to uncover his or her flaws.

Method

Participants

We recruited 113 undergraduate volunteers on the University of Arkansas campus. One participant failed to follow instructions on the key question selection task and another left blank large portions of the questionnaire, leaving 111 participants (47 female, one unknown; age was unavailable) for analyses.1

Procedure

A male experimenter approached undergraduate students around campus about participating in a study concerning a supposed upcoming city council election between two candidates in exchange for a piece of candy. The materials described two candidates, Mike Dever and Matt Petty, of whom one was randomly described as the incumbent. Additionally, we manipulated the relevance of the election for participants via its location either in Fayetteville, AR (where participants resided) or Bloomington, IN (another city far away). Location was an exploratory factor varied to gauge whether personal relevance influenced standards setting.

After reading about the candidates, participants responded to six items, answered on 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree) scales, assessing the standards that should be applied to the incumbent (“Current Councilperson Mike Dever would need to be heavily vetted before sticking with him,” “Strong reasons would be needed to stick with current Councilperson Mike Dever,” and “A large number of reasons would be needed to stick with current Councilperson Mike Dever;” α = 0.72) and to the challenger (e.g., “Challenger Matt Petty would need to be heavily vetted before switching to him;” α = 0.83). Participants indicated their relative candidate preference by indicating who was “best-qualified,” “good,” “the type of person who should be in office,” who they “preferred to be elected,” and “would vote for” (1 = Mike Dever, 9 = Matt Petty; α = 0.88) and they also selected five questions from a list of 12 that they were most interested in having answered. Six questions targeted the incumbent, and six questions targeted the challenger. Half of each set of questions was framed to elicit favorable information (e.g., “How will incumbent Mike Dever's experience in the Planning Commission help economic growth?”) and the other half to elicit unfavorable information (e.g., “What are the potential risks of challenger Matt Petty's economic plan?”).

Results

Standards

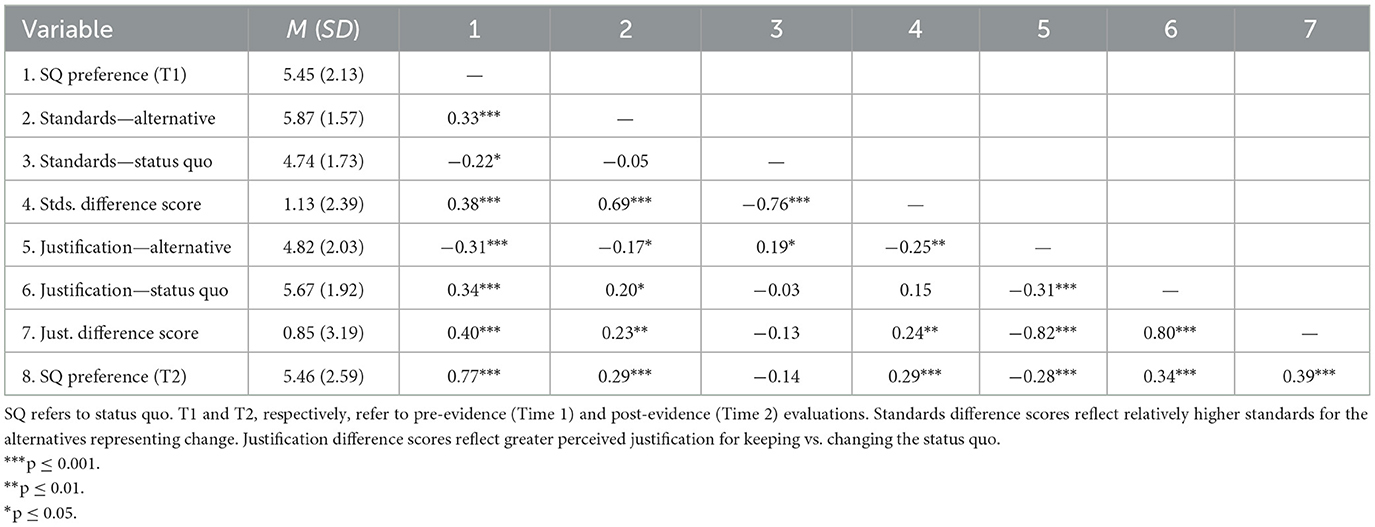

A linear mixed model with random intercepts of participant estimated the fixed effects of incumbency (status quo vs. alternative), political candidate (Matt Petty vs. Mike Dever), location [Fayetteville, AR [local] vs. Bloomington, IN [far away]], and their interactions on standards setting. The model revealed a significant main effect of incumbency, F(1, 214) = 30.32, p < 0.001 (Figure 2). As hypothesized, participants set higher standards for justifying change to the challenger (M = 6.05, SD = 1.41) than maintaining the incumbent (M = 4.98, SD = 1.45), 95% CI for difference [0.68, 1.44]. There were no main effects of political candidate, F(1, 214) = 0.59, p = 0.443, or location, F(1, 214) = 1.01, p = 0.315, and no interaction, Fs = 1.55, ps > 0.21.

Figure 2. Standards for justifying change to the challenger (alternative) vs. maintaining the incumbent (status quo) as a function of political candidate. Error bars: SEs.

Evaluation

A 2 (Incumbent: Mike Dever vs. Matt Petty) × 2 (Location: Fayetteville, AR vs. Bloomington, IN) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of incumbency on candidate preference, F(1, 107) = 7.03, p = 0.009, 95% CI for mean difference [0.19, 1.30]. Participants favored Dever when the incumbent (M = 4.48, SD = 1.28), and favored Petty when he was the incumbent (M = 5.23, SD = 1.65). Neither location, F(1, 107) = 1.40, p = 0.240, nor its interaction with incumbency was significant, F(1, 107) = 0.01, p = 0.927.

Questions

We fit a linear mixed model with random intercepts of participant to estimate the fixed effects of question target (status quo vs. alternative), question valence (positive vs. negative), political candidate (Matt Petty vs. Mike Dever), location (Fayetteville, AR vs. Bloomington, IN), and their interactions on question selection. The model yielded a significant main effect of question target, F(1, 428) = 27.43, p < 0.001, but no effects of question valence, F(1, 428) = 0.62, p = 0.430, political candidate, F(1, 428) = 0.38, p = 0.541, or location, F(1, 428) = 0.00, p = 1.00. Participants directed more questions at the challenger representing change to an alternative (M = 1.44, SD = 0.78) than the incumbent representing the status quo (M = 1.06, SD = 0.76), 95% CI for difference [0.24, 0.52]. We observed uninteresting two-way (Valence × Location), F(1, 428) = 6.41, p = 0.012, three-way (Target × Valence × Candidate), F(1, 428) = 4.42, p = 0.036, and four-way interactions, F(1, 428) = 4.42, p = 0.036, that neither undermined the main effect of question target nor provided theoretically-relevant insights. Specifically, the proclivity to direct more questions at the challenger varied in magnitude erratically depending on valence, candidate, and election location.

Additionally, participants selected more positively than negatively valanced questions for local (Fayetteville, AR: Ms = 1.37 vs. 1.13, SDs = 0.82 vs. 0.72), t = 2.32, p = 0.021, 95% CI for difference [0.04, 0.45], compared to distant elections (Bloomington, IN: Ms = 1.18 vs. 1.32, SDs = 0.80 vs. 0.80), t = 1.25, p = 0.213, 95% CI for difference [−0.33, 0.07]. No other effects emerged, Fs < 1.71, ps > 0.192.

Correlations

Zero-order correlations among study variables are reported in Table 1. We created an index of status quo preference by rescoring evaluations with higher scores indicating stronger preference for the incumbent over the challenger. Whereas status quo preference was associated with higher standards for justifying change to the alternative candidate, it was associated the lower standards for the keeping the incumbent in place. Additionally, the tendency to question the challenger more increased as the standards applied to him increased but it was unrelated to status quo preference and standards applied to the incumbent candidate.

Discussion

Study 2 data indicate that people set higher standards for justifying change to an alternative than maintaining the status quo. Participants required more vetting, more reasons, and stronger reasons for supporting the challenger in a political election compared to when this same candidate represented the status quo as the incumbent. Additionally, candidate evaluations shifted to favor of whoever was the incumbent, and the higher one's preference for the incumbent, the more skewed the standards disadvantaging the challenger. Although exploratory, relevance of the election, by way of its location, did not influence standards or evaluations. We also examined how higher standards for change are related to how people approach seeking positive and negative information about the status quo and its alternatives. Question selection strategies followed a stable pattern: more questions targeted the challenger than the incumbent, implying a strategy of scrutinizing alternatives rather than confirmation bias favoring the status quo. Moreover, higher standards for the challenger and not lower standards for the incumbent predicted question selection disparities. These data suggest that people raise the standards for justifying change, more so than relax standards for maintaining the status quo, and this directs people to prioritizing information about alternatives in service of scrutinizing them. People intuit that there are good reasons for what already is in place (Tworek and Cimpian, 2016; Blanchar and Eidelman, 2021) but selectively ask for more compelling justification for adopting new alternatives, thereby raising the bar for change rather than lowering it for the status quo.

Study 3

Much of status quo maintenance occurs on the front end, as people seek certain types of information over others, selectively scrutinize this information, and so on. But what happens when people are presented with information that is incontrovertibly contrary to upholding the status quo? What if the evidence is mixed or ambiguous? The standards advantage allotted to the status quo should play a role here, too. Holding alternatives to higher standards should result in different conclusions when evidence is held constant. In Study 3, we manipulated which version of a city ordinance represented the status quo and measured standards for and preferences between the alternative and status quo. After which, participants considered evidence that favored the status quo, evidence that favored the alternative, or mixed evidence and indicated the relative justification for retaining the status quo vs. enacting change to the alternative and provided their final evaluation. We anticipated that participants would specify higher standards for the alternative than status quo and evaluate the status quo more favorably than its alternative. We also predicted that they would interpret evidence differently depending on which city ordinance represented the status quo. Whereas, mixed evidence should garner justification for whatever is currently in place, evidence favoring one city ordinance over the other should be judged as sufficient justification for upholding the status quo but insufficient for justifying change to the alternative.

Method

Participants

We recruited 130 undergraduate volunteers (64 female, two unknown; Mage = 19.71, SD = 1.92) on the University of Arkansas's campus.

Procedure

A research assistant approached students on campus and offered candy in exchange for completing a survey concerning city ordinances. Participants read that the law currently allowed or prohibited billboards within the city limits of Fayetteville, AR2; they were informed some people wanted to change this law, while others wanted to keep things the same. Participants then indicated the standards for the status quo (e.g., “The existing law would need to be heavily vetted to keep it in place;” three items, α = 0.79) and alternative (e.g., “The alternative law would need to be heavily vetted before switching to it;” three items, α = 0.68) and provided their evaluations of which city ordinance was likely most “good,” “right,” and “the way things ought to be” (1 = prohibit billboards, 9 = allow billboards; α = 0.88).

After responding to the aforementioned items, participants were shown a table summarizing evidence along eight categories from what was said to be a preliminary investigation into whether the city should prohibit or allow billboards. The evidence was varied such that it favored prohibiting billboards (four categories supported prohibiting, two supported allowing, two were neutral), it favored allowing billboards (four categories supported allowing, two supported prohibiting, two were neutral), or was mixed (three categories supported prohibiting, three supported allowing, two neutral). Participants then indicated their agreement (1 = strongly disagree, 9 = strongly agree) with two items asking whether the evidence justified keeping and changing the current law (“The existing law meets the requirements needed to justify keeping it in place,” “The alternative law meets the requirements needed to justify switching to it”). Finally, participants provided their final recommendation for which ordinance they “supported,” “favored,” and “wanted in place” (1 = prohibit billboards, 9 = allow billboards; α = 0.98).

Results

Standards

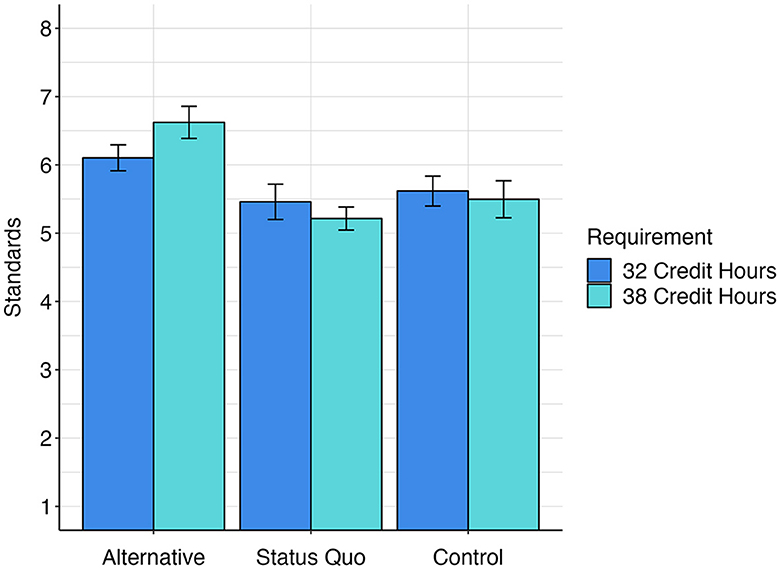

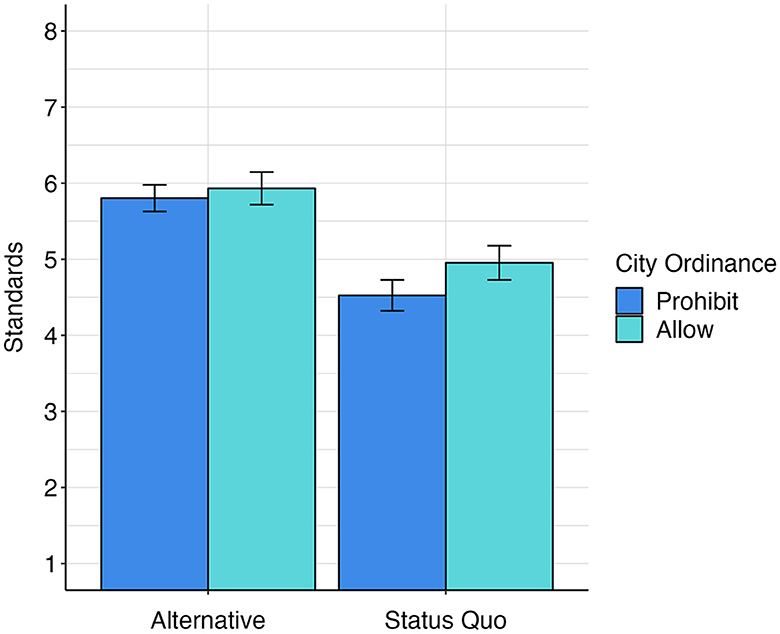

We fit a linear mixed model with random intercepts of participant to estimate the fixed effects of existing policy (status quo vs. alternative), city ordinance (allow vs. prohibit billboards), and their interaction term on standards setting. This model yielded a significant main effect of existing policy, F(1, 256) = 30.42, p < 0.001 (Figure 3). Participants set higher standards for justifying change to the alternative city ordinance (M = 5.87, SD = 1.57) than maintaining the incumbent representing the status quo (M = 4.74, SD = 1.73), 95% CI for difference [0.72, 1.53]. There was no main effect of city ordinance, F(1, 256) = 1.85, p = 0.175, nor did city ordinance interact with status quo, F(1, 256) = 0.53, p = 0.466.

Figure 3. Standards for justifying change to the alternative vs. maintaining the status quo as a function of city ordinance (Study 3). Error bars: SEs.

Pre-evidence evaluation

An independent-samples t-test indicated that pre-evidence evaluations favored prohibiting billboards when it represented the status quo (M = 4.73, SD = 2.11) and shifted to favor allowing billboards when it represented the status quo (M = 5.65, SD = 2.14), t(128) = 2.45, p = 0.016, 95% CI for difference [0.18, 1.65].

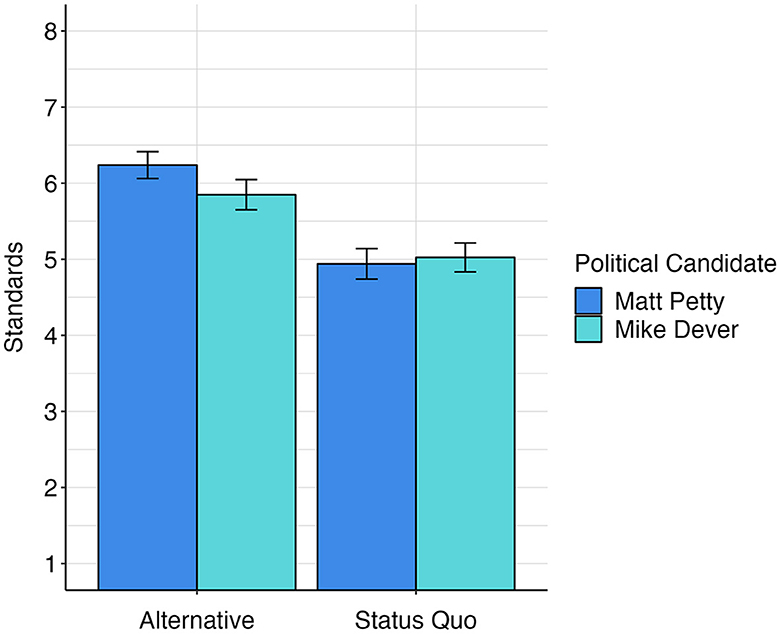

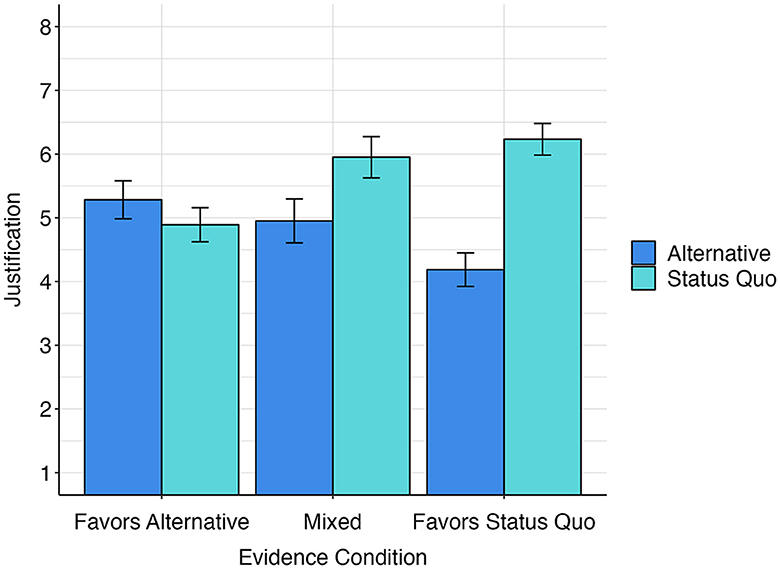

Justification

Perceived justification for keeping vs. changing the status quo was analyzed via a linear mixed model with random intercepts of participant to estimate the fixed effects of existing policy (status quo vs. alternative), evidence condition (favors status quo vs. favors alternative vs. mixed), city ordinance (allow vs. prohibit billboards), and their interactions. This model revealed a significant main effect of existing policy, F(1, 248) = 13.83, p < 0.001, but it was qualified by the predicted existing policy by evidence condition interaction, F(2, 248) = 9.20, p < 0.001 (Figure 4). Keeping the status quo in place garnered more justification than change to the alternative when evidence favored the status quo (Ms = 6.23 vs. 4.19, SDs = 1.63 and 1.72), t = 4.97, p < 0.001, 95% CI for difference [1.24, 2.88], and when the evidence was mixed (Ms = 5.95 vs. 4.95, SDs = 2.07 and 2.20), t = 2.37, p = 0.019, 95% CI for difference [0.17, 1.84]. In contrast, participants judged evidence favoring the alternative as providing equivalent justification for the keeping the status quo (M = 4.89, SD = 1.82) and enacting change to the alternative (M = 5.28, SD = 2.02), t = 1.00, p = 0.318, 95% CI for difference [−1.19, 0.39]. Moreover, perceived justification for change to the alternative was lower when evidence favored change (M = 5.28, SD = 2.02) compared to the perceived justification for keeping the status quo when this same evidence instead favored the status quo (M = 6.23, SD = 1.63), t = 2.31, p = 0.022, 95% CI for difference [0.14, 1.74]. There were no main effects of evidence condition, F(2, 248) = 0.73, p = 0.481, or city ordinance, F(1, 248) = 1.46, p = 0.228, nor did any other interactions emerge, Fs < 1.09, ps > 0.339.

Figure 4. Justification for the alternative and status quo as a function of evidence (Study 3). Error bars: SEs.

Post-evidence evaluation

Post-evidence evaluations were submitted to a 2 (existing policy: prohibit, allow) × 3 (evidence: favors status quo, favors alternative, mixed) between-subjects ANOVA. This analysis revealed a significant main effect of existing policy, F(1, 124) = 4.61, p = 0.034, but it was qualified by a marginally significant existing policy by evidence condition interaction, F(2, 124) = 2.96, p = 0.055. Those exposed to mixed and status quo affirming evidence favored prohibiting billboards when it represented the status quo (Ms = 4.33 and 4.06, SDs = 2.82 and 2.32) and shifted to favor allowing billboards when it represented the status quo (Ms = 6.13 and 5.75, SDs = 2.33 and 2.75), ts = 2.23 and 2.14, ps = 0.028 and 0.034, 95% CIs for differences [0.20, 3.39] and [0.13, 3.24]. However, when evidence favored change, preferences were unaffected by which city ordinance represented the status quo (MProhibit = 5.49, SD = 2.41 vs. MAllow = 4.92, SD = 2.81), t = 0.74, p = 0.462, 95% CI for difference [−2.07, 0.94]. There was no main effect of evidence condition, F(2, 124) = 0.21, p = 0.808.

Correlations

Zero-order correlations among study variables are reported in Table 2. Indexes of status quo preference were computed by rescoring evaluations with higher scores indicating stronger preference for the current city ordinance compared to its alternative. Higher standards for the alternative vs. status quo was associated with stronger status quo preference. Finally, higher standards for the alternative, but not lower standards for the status quo, predicted relatively greater justification for retaining the status quo over change to the alternative.

Discussion

In Study 3, people once again set higher standards for changing compared to maintaining the status quo. Irrespective of whether billboard advertisements were allowed or prohibited, participants indicated that the alternative city ordinance required more vetting, more reasons, and stronger reasons to justify it replacing the current city ordinance. Participants also evaluated the status quo more favorably, and the stronger their preference for the status quo, the higher the standards they put in place for justifying change to the alternative. Interpretations of evidence, experimentally varied to favor maintaining the status quo, changing to the alternative, or to present a mixed portrait, conformed to higher standards for alternatives, such that the same exact evidence favoring one city ordinance over the other was judged as strong justification when it represented maintaining the status quo but insufficient when it represented change to the alternative. Mixed evidence was interpreted as clear justification for whichever city ordinance was allegedly in place. Because of the higher standards for justifying change, alternatives must be backed by much more evidence; otherwise, the status quo maintains.

Small scale meta-analyses

To evaluate the robustness of higher standards for changing than maintaining the status quo, we employed the “metaphor” package in R (Viechtbauer, 2010) to calculate a mean-weighted meta-analytic effect size for the standardized difference between means (Cohen's d unbiased; see Cumming, 2012) via a random-effects model with 95% prediction intervals (PIs). We also meta-analyzed the linear relationship (Pearson's r) between status quo preference and higher standards for change. Finally, we calculated a mean-weighted meta-analytic effect size for the standardized difference between means in the frequency of questions scrutinizing vs. the status quo and for a valence asymmetry in questions likely to reveal more favorable information about the status quo vs. unfavorable information about its alternative. These meta-analyses included effect sizes from seven additional samples we collected but do not report in detail (to avoid redundancy; for details, see Supplementary material).3 The results are presented in Table 3, indicating medium-to-large effect sizes for higher standards for alternatives representing change, d = 0.69 [0.56, 0.81], and its relationship with preference for the status quo, r = 0.39 [0.31,0.46], respectively (ks = 7, total Ns = 535 and 533). Additionally, we found strong and consistent evidence for questions scrutinizing change to the alternative, d = 1.17 [0.82, 1.52], and no evidence for a valence asymmetry in questions reflecting confirmation bias, d = 0.03 [−0.12, 0.17] (ks = 5, total Ns = 285). These meta-analyses include all data we collected for this research program and affirm the stability and robustness of a bias requiring more justification for change than status quo maintenance.

Table 3. Meta-analytic effect sizes of higher standards for change, the relationship between status quo preference and higher standards for change, more frequent questions scrutinizing change, and valence asymmetry in questions that targeting alternatives vs. the status quo.

General discussion

Three studies demonstrate that alternatives to the status quo are subjected to higher standards. Participants indicated that the standards necessary to justify changing an existing institutional requirement (Study 1), a sitting incumbent politician (Study 2), and an established city ordinance (Study 3) are higher than those necessary to maintain it. In each study, who or what represented the status quo and its alternative were experimentally varied; the content of the alternative did not matter, only that it represented change from the existing state of affairs. This work advances our understanding of status bias by highlighting not just the tendency to favor the status quo, but also the increased rigor and justification required for considering and adopting social change.

We also repeatedly found that the more people preferred the status quo, the higher the standards they set for its alternative. However, this does not appear to be a prerequisite. In Study 1, participants instituted higher standards for change despite not evaluating the status quo more favorably. We suggest that the standards effect may not solely hinge on perceiving the status quo as superior, although a preference for the status quo should undoubtedly reinforce it. Instead, the imposition of higher standards for change stems from assumptions people make about the status quo relative to its alternatives. People exhibit caution toward change, often viewing what is familiar and established as safer. The adage “better the devil you know than the devil you don't” captures this sentiment, underscoring the reluctance to embrace uncertainties associated with change. Altering the status quo requires overcoming a significant and higher threshold, as it involves justifying the departure from the familiar and proven. Nevertheless, additional research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms driving this effect and to determine the conditions under which higher standards for change are consistently applied.

Raising standards for justifying change

Several lines of evidence suggest that higher standards for change is more about raising criteria for alternatives than lowering them for the status quo. In Study 1, participants set higher standards for whichever degree requirement represented change to an alternative but set comparable standards for each degree requirement in the control condition when no true status quo existed. Importantly, the standards applied to both options in the control condition were equivalent to those standards applied to the status quo option in the comparison conditions. This suggests that standards were raised when the target was an alternative representing change from the status quo. In Study 2, standards for justifying change to a challenger running for public office were positively associated with more questions scrutinizing him compared to those directed at the incumbent representing the status quo but standards for retaining the incumbent were unrelated to question selections. People appear to elevate standards when justifying change compared to easing standards for maintaining the status quo, as evidenced by their discerning and selective prioritization of information about alternatives—a pattern predicted by one set of standards but not the other.

Consequences for seeking and interpreting evidence

When confronted with the prospect of change, people primarily search for information about alternatives rather than the status quo. We repeatedly observed this phenomenon in the contexts of a political election (Study 2; see also Sample 10) and an institutional requirement (Samples 7–9). Our experimental design involved systematically varying which option served as the status quo vs. its alternative, while keeping the descriptions provided to participants constant. Whichever option was said to represent the alternative was prioritized in the search for information. Contrary to a confirmation bias strategy, we never once found valence differences in the questions participants selected about the status quo vs. its alternative.

Because people hold favorable assumptions about the status quo and its reasons for existence (Eidelman and Crandall, 2014; Tworek and Cimpian, 2016; Blanchar and Eidelman, 2021), they are more skeptical of untested alternatives and require higher standards for change. This promotes a biased search of information in the service of scrutinizing alternatives. As noted by Dawson et al. (2002), “demanding such a strict standard of evidence typically leads to a relatively thorough search through all relevant information, maximizing the chances that any flaws or limitations of the data will be spotted. Thus, people who are motivated to reject an unpalatable proposition may well find cause for doing so” (p. 1380). For instance, scholars report that when Supreme Court Justices direct more questions to one side of a case, that side most often loses their case (Johnson et al., 2009).

Once the search for information is complete, people must weigh the evidence and decide to retain the status quo or enact change to an alternative. However, this process is far from objective. In Study 3, participants considered evidence varying in its support for whether their city should prohibit vs. allow billboard advertisements; simultaneously, the designation of which option represented the status quo was varied. Mixed evidence was reliably interpreted as greater justification for maintaining the status quo over change; people came to see the evidence as more supportive of whichever city ordinance was said to represent the status quo.

In two other conditions, the evidence distinctly favored one option over the other, but objectivity remained elusive. Discrepancies emerged in participants' judgments when the evidence supported either the status quo or its alternative. Evidence that overtly favored the status quo was duly acknowledged; a city ordinance prohibiting billboards was deemed superior and more justified when it represented the status quo, and the same held for an ordinance allowing billboards when it represented the status quo. However, participants did not unilaterally align with evidence overtly favoring the alternative; they construed this evidence as affording comparable levels of justification for both the alternative and status quo. Notably, the quantity and strength of evidence across these two conditions remained identical; our manipulation involved varying which city ordinance represented the status quo vs. its alternative, and the content of each had no impact on participants' responses. They interpreted the same evidence differently based on which city ordinance was allegedly in place, and the higher the standards for the alternative, the less likely participants were to interpret evidence supporting the alternative as sufficient justification for change. Because of higher standards in place for justifying change vs. maintaining the status quo, alternatives must be backed by much more evidence; otherwise, the status quo maintains.

Theoretical and practical implications

A common thread of our research is the recognition that social change is difficult, and people will need to work harder to create change than they would otherwise need to preserve the status quo. These ideas, which provide avenues for future work, are supported by research showing that people match their effort to task demands, working harder for goals they perceive as more difficult to obtain (Kukla, 1972; Wright et al., 1986; Brehm and Self, 1989). To the extent that people recognize the extra barriers that arise from higher standards for change, they may expend more effort, time, and resources in pursuit of change than to stay the course. This perspective complements existing psychological theories of resistance to social change. For instance, Jost (2019) affirms that, “system justification theory does not suggest that social change is impossible, only that it is difficult—for psychological as well as other reasons” (p. 284). System justification theory emphasizes epistemic, existential, and relational needs, and uncertainty and risk associated with change to an unfamiliar alternative is threatening (Jost et al., 2007; Hennes et al., 2012). Hence, advocates of social change have a taller task than those striving to defend the status quo (Jost et al., 2017; Friesen et al., 2019; Blanchar and Eidelman, 2021).

Limitations

Although our studies provide insight into the difficulty of enacting change, several limitations should be acknowledged. For one, our studies were not preregistered. We highlight our commitment to transparency by including data from all studies (k = 10) we conducted within this program of research, and our findings and effect sizes were clear and consistent throughout. Additionally, the sample sizes secured in our studies were relatively small-to-modest in size. Utilizing within-subjects designs for the key comparisons between the status quo and alternative alleviates some concern, as does computing meta-analytic effect sizes across all samples. All our studies were conducted in the United States with non-representative, college student samples. Whether our results generalize to other populations remains to be tested. Finally, while we investigated four very distinct domains, when including our additional samples, there are many others. Surely some situations and contexts would reveal boundary conditions, such as when the status quo is truly intolerable, people are motivated partisans that identify with a movement for social change, or people are area experts that possess a well of knowledge and experience to draw from. These considerations provide avenues for future research.

Concluding remarks

Due to positive assumptions about the status quo and its underlying reasons for existence, people tend to approach untested alternatives with skepticism, demanding higher standards for change. While previous investigations of status quo maintenance have emphasized people's justification and defense of the status quo, we emphasize the difficult task of justifying change. When something represents change from what is already established, the goal posts are moved back and the task of reaching sufficient justification becomes harder. This facilitates critical scrutiny of alternatives and skews interpretations of evidence. Sanctioning change requires justification, greater so than maintaining the status quo.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. All data, materials, and analysis scripts are available via Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/dg723/?view_only=ef4dde66a98842c9b8990c9bd26b908f.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JB: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. SE: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. EA: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Excluding these two participants from analyses did not change any results.

2. ^The city of Fayetteville prohibited billboards within its city limits at the time of data collection, but adjacent areas did not. Therefore, participants could not recall any instances of billboards with certainty. Participants were not familiar with the law, and none expressed suspicion about the accuracy of study materials.

3. ^The three studies presented in this paper were conducted as follow-up investigations to seven earlier studies. These earlier studies recruited smaller sample sizes (Ns = 28–100) and contained either our measure of standards setting or the question-selection task, but not both (except for the smallest study: Sample 7, N = 28). We decided to present the three larger and more complete studies in detail and to report the effects of the seven additional samples via small scale meta-analyses (see Table 3). All materials and data are available online via Open Science Framework.

References

Anderson, C. J. (2003). The psychology of doing nothing: forms of decision avoidance result from reason and emotion. Psychol. Bullet. 129, 139–167. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.139

Balcetis, E., and Dunning, D. (2006). See what you want to see: motivational influences on visual perception. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 91, 612–625. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.612

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., and Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Blanchar, J. C., and Eidelman, S. (2013). Perceived system longevity increases system justification and the legitimacy of inequality. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 43, 238–245. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.1960

Blanchar, J. C., and Eidelman, S. (2021). Implications of longevity bias for explaining, evaluating, and responding to social inequality. Soc. Just. Res. 34, 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s11211-021-00364-1

Bornstein, R. F. (1989). Exposure and affect: overview and meta-analysis of research, 1968–1987. Psychol. Bullet. 106, 265–289. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.265

Brehm, J. W., and Self, E. A. (1989). The intensity of motivation. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 40, 109–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.000545

Cimpian, A., and Salomon, E. (2014). The inherence heuristic: an intuitive means of making sense of the world, and a potential precursor to psychological essentialism. Behav. Brain Sci. 37, 461–480. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X13002197

Cumming, G. (2012). Understanding the New Statistics: Effect Sizes, Confidence Intervals, and Meta-Analysis. New York, NY: Routledge.

Dawson, E., Gilovich, T., and Regan, D. T. (2002). Motivated reasoning and performance on the Wason Selection Task. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 28, 1379–1387. doi: 10.1177/014616702236869

Ditto, P. H., and Lopez, D. F. (1992). Motivated skepticism: use of differential decision criteria for preferred and nonpreferred conclusions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 63, 568–584. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.568

Ditto, P. H., Scepansky, J. A., Munro, G. D., Apanovitch, A. M., and Lockhart, L. K. (1998). Motivated sensitivity to preference-inconsistent information. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 75, 53–69. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.53

Dunning, D. (1993). “Words to live by: the self and definitions of social concepts and categories,” in Psychological Perspectives on the Self, Vol. 4, ed. J. Suls (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 99–126.

Eidelman, S., and Crandall, C. S. (2014). “The intuitive traditionalist: how biases for existence and longevity promote the status quo,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 50, ed. M. Zanna (New York, NY: Academic Press), 53–104.

Eidelman, S., Crandall, C. S., and Pattershall, J. (2009). The existence bias. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 97, 765–775. doi: 10.1037/a0017058

Eidelman, S., Pattershall, J., and Crandall, C. S. (2010). Longer is better. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 46, 993–998. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.07.008

Fischer, P., and Greitemeyer, T. (2010). A new look at selective-exposure effects: an integrative model. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 19, 384–389. doi: 10.1177/0963721410391246

Friesen, J. P., Laurin, K., Shepherd, S., Gaucher, D., and Kay, A. C. (2019). System justification: experimental evidence, its contextual nature, and implications for social change. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 58, 315–339. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12278

Gilovich, T. (1983). Biased evaluation and persistence in gambling. J. Persona. Soc. Psychol. 44, 1110–1126. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.44.6.1110

Gilovich, T. (1991). How We Know What Isn't So: The Fallibility of Human Reason in Everyday Life. New York, NY: Free Press.

Green, P., and MacLeod, C. J. (2016). SIMR: an R package for power analysis of generalized linear mixed models by simulation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 493–498. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12504

Harrison, A. A. (1977). “Mere exposure,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 10, ed. L. Berkowitz (New York, NY: Academic Press), 39–83.

Hart, W., Albarracín, D., Eagly, A. H., Brechan, I., Lindberg, M. J., and Merrill, L. (2009). Feeling validated versus being correct: a meta-analysis of selective exposure to information. Psychol. Bullet. 135, 555–588. doi: 10.1037/a0015701

Hennes, E. P., Nam, H. H., Stern, C., and Jost, J. T. (2012). Not all ideologies are created equal: epistemic, existential, and relational needs predict system-justifying attitudes. Soc. Cogn. 30, 669–688. doi: 10.1521/soco.2012.30.6.669

Jackman, M. R. (1994). The Velvet Glove: Paternalism and Conflict in Gender, Class, and Race Relations. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Johnson, T. R., Black, R. C., Goldman, J., and Treul, S. A. (2009). Inquiring minds want to know: do justices tip their hands with questions at the oral argument in the U.S. Supreme Court? J. Law Pol. 29, 241–261.

Jost, J. T. (2019). A quarter century of system justification theory: questions, answers, criticisms, and societal applications. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 58, 263–314. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12297

Jost, J. T., Banaji, M. R., and Nosek, B. A. (2004). A decade of system justification theory: accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Polit. Psychol. 25, 881–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00402.x

Jost, J. T., Becker, J., Osborne, D., and Badaan, V. (2017). Missing in (collective) action: ideology, system justification, and the motivational antecedents of two types of protest behavior. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 26, 99–108. doi: 10.1177/0963721417690633

Jost, J. T., Napier, J. L., Thorisdottir, H., Gosling, S. D., Palfai, T. P., and Ostafin, B. (2007). Are needs to manage uncertainty and threat associated with political conservatism or ideological extremity? Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 33, 989–1007. doi: 10.1177/0146167207301028

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., and Thaler, R. (1991). The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status-quo bias. J. Econ. Perspect. 5, 193–206. doi: 10.1257/jep.5.1.193

Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., Peach, J. M., Laurin, K., Friesen, J., Zanna, M. P., et al. (2009). Inequality, discrimination, and the power of the status quo: direct evidence for a motivation to see the way things are as the way they should be. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 97, 421–434. doi: 10.1037/a0015997

Kukla, A. (1972). Foundations of an attributional theory of performance. Psychol. Rev. 79, 454–470. doi: 10.1037/h0033494

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychol. Bullet. 108, 480–498. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., and Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1–26. doi: 10.18637/jss.v082.i13

Liberman, A., and Chaiken, S. (1992). Defensive processing of personally relevant health messages. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 18, 669–679. doi: 10.1177/0146167292186002

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., and Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: the effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 37, 2098–2109. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.37.11.2098

Magezi, D. A. (2015). Linear mixed-effects models for within-participant psychology experiments: an introductory tutorial and free, graphical user interface (LMMgui). Front. Psychol. 6:2. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00002

Major, B. (1994). “From social inequality to personal entitlement: the role of social comparisons, legitimacy appraisals, and group membership,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 26, ed. M. Zanna (New York, NY: Academic Press), 293–355.

Miron, A. M., Branscombe, N. R., and Biernat, M. (2010). Motivated shifting of justice standards. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 36, 768–779. doi: 10.1177/0146167210370031

Moshinsky, A., and Bar-Hillel, M. (2010). Loss aversion and status quo label bias. Soc. Cogn. 28, 191–204. doi: 10.1521/soco.2010.28.2.191

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: a ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2, 175–220. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175

O'Brien, L. T., and Crandall, C. S. (2005). Perceiving self-interest: power, ideology, and maintenance of the status quo. Soc. Just. Res. 18, 1–24. doi: 10.1007/s,11211-005-3368-4

R Core Team (2024). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online at: https://www.R-project.org

Ritov, I., and Baron, R. (1992). Status quo and omission biases. J. Risk Uncertainty 5, 49–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00208786

Samuelson, W., and Zeckhauser, R. (1988). Status quo bias in decision making. J. Risk Uncertainty 1, 7–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00055564

Sherman, J. W., Stroessner, S. J., Conrey, F. R., and Azam, O. A. (2005). Prejudice and stereotype maintenance processes: attention, attribution, and individuation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 89, 607–622. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.607

Snyder, M., and Swann, W. B. (1978). Hypothesis-testing processes in social interaction. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 36, 1202–1212. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.36.11.1202

Taber, C. S., and Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 50, 755–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x

Tworek, C. M., and Cimpian, A. (2016). Why do people tend to infer “ought” from “is”? The role of biases in explanation. Psychol. Sci. 27, 1109–1122. doi: 10.1177/0956797616650875

Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36, 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v036.i03

Wright, R. A., Contrada, R. J., and Patane, M. J. (1986). Task difficulty, cardiovascular response, and the magnitude of goal valence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 51, 837–843. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.4.837

Keywords: status quo bias, social change, information search, existence bias, shifting standards

Citation: Blanchar JC, Eidelman S and Allen E (2024) Social change requires more justification than maintaining the status quo. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2:1360377. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2024.1360377

Received: 22 December 2023; Accepted: 08 July 2024;

Published: 04 September 2024.

Edited by:

Joaquín Bahamondes, Universidad Católica del Norte, ChileReviewed by:

Dmitry Grigoryev, National Research University Higher School of Economics, RussiaSarah Buhl, Chemnitz University of Technology, Germany

Jojanneke van der Toorn, Leiden University, Netherlands

Copyright © 2024 Blanchar, Eidelman and Allen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: John C. Blanchar, amJsYW5jaGFAZC51bW4uZWR1

John C. Blanchar

John C. Blanchar Scott Eidelman

Scott Eidelman Eric Allen3

Eric Allen3