94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Soc. Psychol. , 26 June 2024

Sec. Attitudes, Social Justice and Political Psychology

Volume 2 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsps.2024.1356998

This article is part of the Research Topic The Political Psychology of Social Change View all 12 articles

Movements for progressive social change (e.g., Black Lives Matter, #MeToo) are commonly met with reactionary counter-movements that seek to protect the rights and interests of structurally advantaged groups (e.g., All Lives Matter, #MenToo). Drawing on the insights of the social identity approach and the needs-based model of reconciliation, the current research explores whether men's support for progressive and reactionary action (i.e., their intentions to promote women's rights and men's rights, respectively) are shaped by their need to defend their group's moral identity. Combined analyses of three samples (N = 733) showed that men's social identification was associated with their reduced intentions to act for women's rights and positively related to their intentions to promote men's rights—effects mediated by their need for positive moral identity and defensiveness regarding the issue of gendered violence. Overall, the findings suggest that defensive construals regarding group-based inequalities may not only present a barrier to men's engagement in collective action for gender equality, but might also underlie their participation in reactionary actions designed to advance the rights of their own (advantaged) group.

In recent years, movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter have highlighted the pervasive nature of racial and gendered violence and led to increased societal discussions regarding ongoing discrimination against women and ethnic minorities. Notably, these movements have called on members of structurally advantaged groups (i.e., men, White people) to acknowledge their group's power, privilege, and history of perpetrating harm against members of the disadvantaged group. For example, the #MeToo movement drew attention to the over representation of men among perpetrators of sexual harassment and assault. Similarly, Black Lives Matter continues to demand that the state acknowledge and address institutionalized racism and violence against Black people and ethnic minority groups.

The reactions of advantaged group members to movements advocating for social change are varied (Radke et al., 2020; see also Kutlaca et al., 2020; Shuman et al., 2024). While some choose to stand in solidarity with the disadvantaged group to challenge injustice (e.g., men who tweeted “#HowIWillChange” in reaction to women's disclosures of sexual violence; PettyJohn et al., 2019), others respond with backlash and resistance (e.g., men who claim that the #MeToo movement discriminates against their group; de Maricourt and Burrell, 2022; Lisnek et al., 2022). Indeed, both #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter triggered reactionary counter-movements (#MenToo, #AllLivesMatter) that sought to advocate for the rights of the advantaged group (Becker, 2020; Boyle and Rathnayake, 2020; Choma et al., 2020; West et al., 2021; Thomas and Osborne, 2022). The interactions between these movements (based on, respectively, support for, and opposition to, the rights of disadvantaged and advantaged group members) are an example of what Thomas and Osborne (2022) term the dialectical nature of collective action.

In the current paper, we explore the processes underlying men's support for progressive vs. reactionary forms of collective action. That is, we examine men's intentions to support women's rights, and their intentions to engage in actions designed to promote the rights of their own—advantaged—group (Becker, 2020; Thomas and Osborne, 2022). Drawing on insights from social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979) and the needs-based model of reconciliation (Shnabel and Nadler, 2008), we propose that men's support for collective actions designed to promote women's and men's rights, respectively, may be shaped, in part, by their distinct identity-based needs as members of a structurally advantaged group (i.e., their social identification as members of a group held responsible for perpetrating harm).

Extending work on the relationship between moral image concerns and advantaged group members' support for the disadvantaged groups' action (see Kende et al., 2020; Teixeira et al., 2020), we propose that men's need to defend their group's morality may not only undermine their intentions to support the movement to end gender-based violence—but, that it may also motivate their engagement in reactionary actions designed to promote the rights of their own group. In doing so, our approach brings together work on defensive reactions to reminders of ingroup harmdoing (Doosje et al., 1998; Leidner et al., 2010; Bilali et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2012; Leach et al., 2013; Rotella and Richeson, 2013; Bilali and Vollhardt, 2019) with the collective action literature (see Thomas et al., 2022, for an overview) to understand how advantaged group members respond to movements advocating for justice and equality for disadvantaged groups.

Social psychological research on advantaged group members' support and opposition to social change has focused predominantly on how the increasing rights of disadvantaged group members can lead members of the advantaged group to feel that their position in the status hierarchy is under threat (Craig and Richeson, 2014, 2018; Dover et al., 2016; Shepherd et al., 2018; Reicher and Ulusahin, 2020; Brown et al., 2022; Domen et al., 2022; Rivera-Rodriguez et al., 2022). Advantaged group members' perception that they are competing with the disadvantaged group for power and resources has been associated with their reduced support for progressive policies designed to protect minority group members from prejudice and discrimination (Leach et al., 2007; Norton and Sommers, 2011; Craig and Richeson, 2014). In a similar vein, research has linked conservative ideologies such as right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) and social dominance orientation (SDO) with advantaged group members' opposition to system-challenging action (e.g., Black Lives Matter), and their engagement in system-supporting action (e.g., White nationalist movements that seek to protect “White power”; Choma et al., 2020; Selvanathan et al., 2020; Holt et al., 2022).

However, movements for progressive social change are not only concerned with the disadvantaged group's access to rights and resources. Protest from disadvantaged groups also highlight the unearned privileges and immoral actions of the advantaged group (Kende et al., 2020; Teixeira et al., 2020; Okuyan and Vollhardt, 2022; Shuman et al., 2024). For example, commentary surrounding the #MeToo movement notes that while #MeToo was instrumental in emphasizing the need for structural, legislative change to prevent violence against women, it also brought into sharp relief men's over representation as the perpetrators of sexual violence (Hill, 2021; de Maricourt and Burrell, 2022; Lisnek et al., 2022). Hill (2021) describes how, as #MeToo gained traction online in 2017, it increasingly became an “accountability” movement concerned with promoting justice for victims and retribution for male perpetrators (p. 10). In this way, movements like #MeToo not only challenge existing power relations between men and women, but also call into question men's moral character.

Members of historically advantaged groups are particularly sensitive to information that suggests that their group has acted immorally (Doosje et al., 1998; Sullivan et al., 2012; Knowles et al., 2014; Bilali and Vollhardt, 2019; Kahalon et al., 2019). According to the needs-based model of reconciliation (Shnabel and Nadler, 2008; Aydin et al., 2019), disadvantaged group members—who are often the victims of discrimination—can experience a threat to their need for power and agency. Conversely, advantaged group members—who are often accused of being prejudiced against the disadvantaged group—experience a heightened need for morality and acceptance (Shnabel et al., 2009; Nadler and Shnabel, 2015). This need is particularly heightened for members of the advantaged group who are strongly attached to their ingroup (that is, those who view their social identification in a particular group as central to their self-concept; Branscombe et al., 1999).

Drawing on the framework provided by the needs-based model, research has shown that advantaged group members' support for social movements designed to promote the rights of the disadvantaged group is influenced by their perception that their group's moral image is under attack (see Shnabel et al., 2013; Kahalon et al., 2019; Kende et al., 2020; Teixeira et al., 2020). For example, Kende et al. (2020) found that men's need to defend their group's moral reputation was associated with their reduced support for the #MeToo campaign. Similarly, Teixeira et al. (2020) showed that advantaged group member's support for the disadvantaged group's protest decreased as a function of people's concerns about their group's moral image.

However, to date, research on support for (and opposition to) progressive social change has tended to focus on how morality concerns may undermine advantaged group members' support for the disadvantaged group's protest, without considering how morality needs might also mobilize advantaged group members to advocate for the rights of their own (privileged) group. This is despite the fact that, in recent years, counter-movements on behalf of advantaged group members (#NotAllMen, #MenToo, #AllLivesMatter) have often been characterized by attempts to defend against threats to their group's morality (e.g., by denying the advantaged group's role in perpetrating harm; Bilali, 2013); by minimizing the severity of the wrongdoing (Leidner et al., 2010; Bilali et al., 2012); and/or by arguing that the advantaged group has suffered more than the disadvantaged group (competitive victimhood; Noor et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2012; Young and Sullivan, 2016).

In the context of women's disclosures of sexual harassment, men's backlash often includes defensive strategies designed to downplay or outright deny the issue of violence against women (Sullivan et al., 2012; Flood, 2019; Flood et al., 2021; Okuyan and Vollhardt, 2022). “Not all men” is a common argument used to claim that sexual violence is only perpetrated by a few “bad apples”, thereby allowing men to deny the structural nature of gendered violence by positioning it as a problem attributable to a “deviant” few (Flood, 2019). In response to “#MeToo”, “#MenToo” responded with claims that men are also the victims of sexual harassment and violence—or, the victims of false rape allegations (Gruber, 2009; Flood et al., 2021; de Maricourt and Burrell, 2022). As victims are often viewed as morally superior to perpetrators, claims to victimhood (such as “#MenToo”) can function to defend against moral image threats by asserting one's own group has “moral credentials” (see also Noor et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2012, p. 102; Young and Sullivan, 2016).

Defensive reactions to reminders of ingroup harm have received substantial attention in social psychology (see Bandura et al., 1996; Bandura, 1999; Peetz et al., 2010; Noor et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2012; Rotella and Richeson, 2013; Bilewicz, 2016; Bilali and Vollhardt, 2019). In the present research, we propose that defensiveness—that is, the various strategies people can employ to protect against threats to their personal or group identity—may shape men's intentions to engage in progressive forms of collective action (i.e., their support for women's rights), and their intentions to promote the rights of their own (advantaged) group (i.e., support for men's rights). In the context of online content implicating men as the perpetrators of sexual harassment, we examine the relationship between men's social identification and concerns about their group's morality. We expect that men's need for morality should motivate defensive reactions regarding the issue of sexual harassment. We test whether defensiveness, in turn, is negatively related to men's intentions to act for women's rights, and positively associated with their intentions to act on behalf of the rights of their own group (i.e., for men's rights).

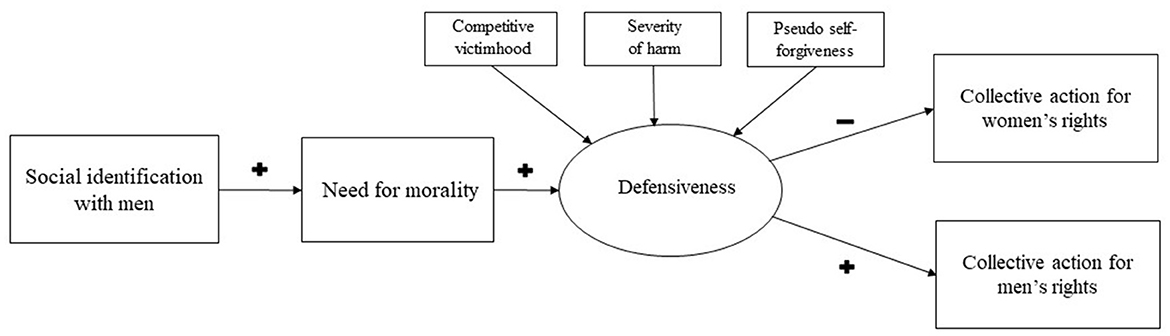

The current paper explores whether men's need to defend their group's moral identity shapes both their intentions to take action to promote equality for women and their intentions to act to advance the rights of their own (advantaged) group (as a form of reactionary collective action; Thomas and Osborne, 2022). We examine these ideas in the context of fabricated online content that emphasizes men's role in perpetrating sexual harassment (participants viewed tweets highlighting men's responsibility for maintaining and addressing sexual harassment). Based on the key tenets of the needs-based model (Shnabel and Nadler, 2008), we expect that men's need for morality will arise as a function of their commitment to their group membership (i.e., their social identification with men; Tajfel and Turner, 1979). Men's need for morality should, in turn, be associated with defensive strategies designed to protect their ingroup (see Figure 1 for our full conceptual model).

Figure 1. Conceptual model of how men's progressive and reactionary actions are shaped by morality needs and defensiveness.

Based on common ways groups can defend against threats to their identity identified in both the interpersonal and intergroup literatures, in the current studies we operationalized defensiveness as the extent to which men competed with women for victim status (competitive victimhood; Noor et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2012), perceived men as experiencing more harm as a result of sexual harassment in the workplace and its consequences—compared to women (Bilali et al., 2012)—and their engagement in pseudo self-forgiveness (the extent to which they let men “off the hook”, by minimizing harm, denying wrongdoing, and derogating the victim group; Hall and Fincham, 2005; Fisher and Exline, 2006; Woodyatt and Wenzel, 2013). Responses to each of these variables were parceled together and modeled as reflective indicators of defensiveness. This approach allows for consideration of the shared or common underlying construct of defensiveness, while transcending individual literatures on (for example) attributions of harm and competitive victimhood, per se. Statistically, the parceling approach we adopt creates a more parsimonious model while accounting for measurement error (rather than using all items separately; Hall et al., 1999).

Finally, we test the relationship between defensive construals regarding the issue of sexual violence, and men's intentions to participate in collective action for both women's rights and men's rights. Building on existing work regarding the influence of moral identity threats on advantaged group members' support for the disadvantaged group's protest (see Shnabel et al., 2013; Kende et al., 2020; Teixeira et al., 2020; Hässler et al., 2022), we expect that defensiveness will be negatively related to men's willingness to act collectively for women's rights. In contrast, we expect that defensiveness may positively predict collective action for men's rights—as publicly advocating for equality for men offers a means of deflecting attention away from the morally threatening issue of men's violence against women (Sullivan et al., 2012). If the hypotheses are supported, it would show that the same process of defensiveness explains variation in commitment to actions that promote justice for women (negative effect) and men (positive effect). We test our theoretical model (Figure 1) across three samples (total N = 733) using Multigroup Structural Equation Modeling (MSEM).

The current research was originally pre-registered on the Open Science Framework as three experiments that sought to manipulate a threat to men's need for morality via an accusation of ingroup wrongdoing: https://osf.io/fnxaq?view_only=6940e019f0114f04a32be8c56aee63dd.i We expected that the relationship between men's social identification and their need for morality would be strengthened in contexts where their group was explicitly implicated as responsible for women's victimization (i.e., when morality concerns are most salient; Sullivan et al., 2012; Knowles et al., 2014).

However, all three experimental manipulations were unsuccessful in shifting men's need for positive moral identity.1 In all studies, men's need for morality was above the midpoint across conditions—highlighting the strength of the relationship between people's social identification and their need for their group to be seen as good and moral (Branscombe et al., 1999; Aquino and Reed, 2002; Ellemers and Barreto, 2003; Nadler and Shnabel, 2015). We believe that the failed manipulations speak to a key challenge of experimental social and political psychology: that it is often difficult to successfully shift the nature of people's deeply rooted identities, ideologies, attitudes, and behaviors (see Spears and Smith, 2001, for a discussion).

In the current paper we solely focus on reporting the results of our mediation model (Figure 1) across the three samples. In the interests of full transparency we report the stimuli, methods, results, and discussion regarding the threat manipulations in a Supplementary file.2 This file also includes information regarding exploratory measures taken across the three studies. The original pre-registration documentation and data sets are stored in a repository on the Open Science Framework.

All three samples were made up of North American men recruited online via Amazon's Mechanical Turk (TurkPrime; Litman et al., 2017). All participants were US citizens. Sample 1 comprised of 198 men (Mage = 37.99, SDage = 12.99). They were predominantly White (88%) and heterosexual (89%). 55% were bachelor's degree educated or higher. Sample 2 included 296 men (Mage = 37.16, SDage= 11.85). Participants were predominantly White (81%) and heterosexual (90.2%). Around 60% indicated that they had a bachelor's degree or higher. Sample 3 comprised of 239 men (Mage= 38.86, SD = 12.89; 93% heterosexual). 69% of participants identified as White, 18% as Asian, and 10% as Black. 63% reported they held a bachelor's degree or higher.

The procedure was similar across the three samples. Participants completed a survey titled “Responses to Online Information”. The studies were advertised as surveys interested in understanding how people respond to information that they encounter on social media. All three studies used the same measures of social identification,3 need for morality, defensive strategies, and collective action intentions (for men's rights, and women's rights, respectively). Therefore, taking the data from these three separate samples, we conducted a combined analysis using multigroup structural equation modeling (SEM) to test our theoretical model (Figure 1). Multigroup SEM allows for the testing of complex mediation models across groups (i.e., across different samples; Yuan and Chan, 2016). Below, we detail how each of our key constructs was measured.

Sensitivity analyses using pwrSEM v 0.1.2 (Wang and Rhemtulla, 2021) for parameter estimation in structural equation modeling showed that our samples (N = 198, 296, 239) were sufficient to detect an indirect effect (f = 0.03–0.13, i.e., a small effect; Cohen, 1988) of social identification on collective action intentions via need for morality and defensiveness, assuming an alpha of 0.05 and power of 0.80.

Unless otherwise indicated, items were answered on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). We report multi-item scale reliabilities using Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficients. Given that the measures of our key constructs were taken in the context of participants viewing (fabricated) Twitter content regarding women's disclosures of sexual harassment, some items reflect this specific context. See the Supplemental material file for all stimuli used across samples.

One item from each of Leach et al.'s (2008) five subscales of social identification was adapted to assess men's social identification. Example items included “The fact I am a man is an important part of my identity” (centrality), “I am glad to be a man” (ingroup affect), and “I feel a bond with other men” (solidarity), α = 0.85–0.87 across samples. In sample 3, the measure of social identification was measured on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree).4

To control for potential order effects, the measure of social identification was counterbalanced with half of the participants completing the measure at the start of the survey and the other half completing the measure at the end of the study. The order in which participants completed the measure of ingroup identification did not impact their levels of identification, or the other main variables of interest.

Adapted from Shnabel and Nadler (2008), three items assessed participants need for their group to be seen as moral by members of the outgroup: “I wish that women would perceive men as moral”, “I would like women to know that men try to act fairly, and “I would like women to understand that men are not harsh people”, α = 0.88–0.89 across samples.

As anticipated above, defensiveness was operationalized with a latent combination of variables that, together, conceptually denote ways group members can defend against threats to their ingroup's moral image, either by downplaying their group's role in perpetrating harm, or through attempts to claim victim status.

Competitive victimhood was captured by the extent to which men believed their group is victimized more than women. Four items were adapted from Kahalon et al. (2019): “[Economically/politically/socially] men in America are discriminated against more than women” and “Men in America are now suffering more emotional pain than women”, α = 0.92 across samples.

One item (adapted from Bilali et al., 2012) measured participant's perceptions of the severity of harm inflicted on their own group compared to women due to the issue of sexual harassment in the workplace, “Which group experiences more harm as a result of sexual harassment against women in the workplace?”. Responses were measured on a bipolar scale where 1 = women and 7 = men, such that higher scores reflected the perception that men suffer more harm due to sexual harassment, compared to women.

Six items measured the extent to men engaged in pseudo self-forgiveness (letting their group “off the hook” for wrongdoing; Hall and Fincham, 2005; Woodyatt and Wenzel, 2013; Wenzel et al., 2023) by denying their group's involvement in perpetrating sexual harassment and blaming women for the issue of sexual harassment. Example items include: “I think the person in the tweet was really to blame for what happened”, “I'm not really sure whether what men did was wrong”, and “Men aren't the only ones to blame for what happened”, α = 0.83–0.85 across samples.

Participants indicated their agreement with a series of statements involving intentions to act on behalf of their own group (men) and women, e.g. “I intend to advocate for equality for [women/men] in my own place of work”, “I intend to raise awareness of the issues that some [women/men] experience in the workplace by posting on social media”, (men: α = 0.61–0.68, women: α = 0.57–68).

Given that sample 3 measured social identification on a 9-point scale and samples 1 and 2 used a 7-point scale, our first step was to transform this scale to a comparable 7-point scale. No other transformations were applied.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between variables for each of the three samples can be found in Table 1.

Multigroup structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted using Amos 29.0 to test our hypothesized mediation model. We tested a model where regression weights for all paths were constrained to be equal across samples (that is, we assumed that the relationships between variables would not differ across different populations, in this case, the samples from the three discrete studies). Social identification was a direct predictor of men's need for morality. Need for morality was expected to be positively associated with defensiveness, which should, in turn, be negatively associated with men's intentions to participate in collective action in solidarity with women. Further, we tested whether men's defensiveness was also significantly positively related to their intentions to act to promote the rights of their own group (i.e., men's rights).

We report several widely accepted model fit indices: the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Cut-off points for these fit indices were: 0.95 or higher for CFI; 0.08 or lower for SRMR, and values of 0.01, 0.05, and 0.08 indicating excellent, good, and acceptable fit, respectively for RMSEA (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Bentler, 2007). Indirect effects were computed using the indirect effects command in Amos with 10, 000 bootstrap samples (95% confidence intervals). We concluded that the indirect effect was significant when the 95% CI did not include zero.

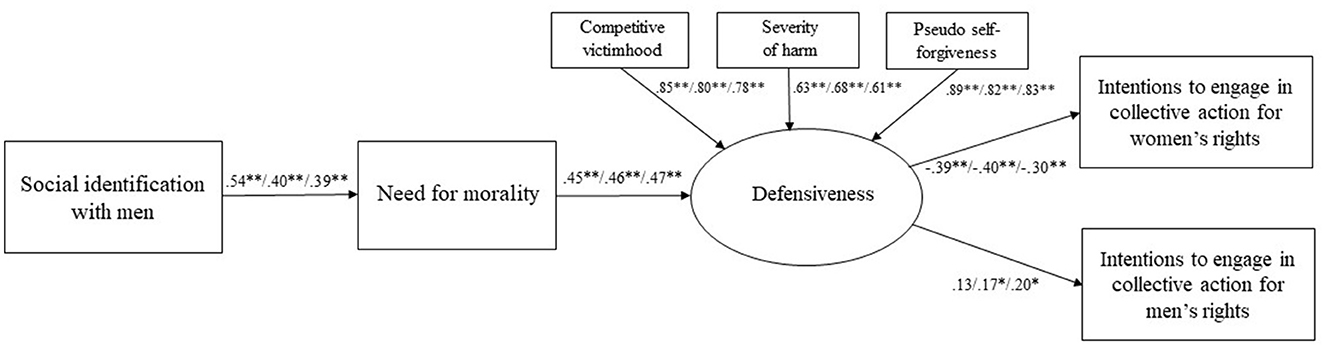

The model evidenced good fit with the data, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.06. The results of the constrained model with standardized (beta) path weights is shown in Figure 2 (note that the regression weights are similar across samples as we have constrained the parameter estimates to be the same—accordingly, differences are due to variation in sample standard deviations). All paths are significant at p < 0.001, except for the defensiveness-collective action (for men's rights) path, which was significant at p < 0.01 for samples 2 and 3.

Figure 2. Mediation model predicting men's intentions to act for women's and men's rights. values are standardized regression coefficients for the hypothesized structural model. the values for the model in sample 1 are to the left of the slash, sample 2 in the middle, and sample 3 on the right. **denotes that the path is significant at p < 0.001. *denotes that the path is significant at p < 0.01. N.B. the residual error terms for both collective action intention variables (for men and for women) were allowed to covary.

There was a significant negative indirect effect of social identification on collective action (for women) via need for morality and defensiveness across all three samples (see Table 2). There was a significant, positive indirect effect of social identification on collective action (for men) in samples 2 and 3.

The current paper examined men's intentions to act for women's rights (i.e., their support for progressive collective action) and their intentions to act to advance the rights of their own (advantaged) group (i.e., their support for reactionary action). Drawing on the insights of the social identity approach (Tajfel and Turner, 1979) and the needs-based model of reconciliation (Shnabel and Nadler, 2008), we tested whether (a) men's social identification was negatively associated with their intentions to act for equality for women and positively related to their intentions to advocate for men's rights, and (b) whether men's need for morality and defensiveness mediated these effects.

Three studies provide evidence for our conceptual model (Figure 1). Men's social identification was positively related to their desire for women to accept their group as good and moral, which, in turn, increased their defensiveness regarding the issue of men's violence against women. In line with empirical work on the impact of morality concerns on support for progressive social change (Kende et al., 2020; Teixeira et al., 2020), we show that men's attempts to defend their group's morality was negatively associated with their intentions to engage in collective action for women's rights (samples 1–3). However, we expand on previous research by showing that men's defensiveness was positively related to their intentions to participate in action to promote the rights of their own group, over and above their decreased commitment to advocate for equality for women (this effect was significant in samples 2 and 3).

Overall, our results suggest that advantaged group member's need to protect their group's moral identity may not only act as a barrier to their participation in actions to advance the rights of the disadvantaged group—but may also motivate them to act to advocate for the rights of their own (privileged) group. These findings seem particularly significant, given that supporters of reactionary counter-movements to feminist efforts (such as “#MenToo” or “#HimToo”) commonly argue that the use of these hashtags simply represent attempts to broaden the “inclusivity” of the gender equality movement (Boyle and Rathnayake, 2020). However, in the current research, men's intentions to act on behalf of their own group were associated with downplaying the issue of violence against women, blaming women for the issue of sexual harassment and assault, and claiming that men suffer more (politically, socially, economically) than women. These results align with work by West et al. (2021) in the context of racial inequality—who note that while supporters of “All Lives Matter” (ALM) typically argue that ALM is “more inclusive” than “Black Lives Matter”, support for ALM is associated with color-blind ideologies that seek to deny the reality of racial inequality.

The pattern of results in the present studies suggest that potential solutions to attenuating the relationship between men's social identification and their need to defend their group's moral identity may lie in targeting the nature of men's social identification—that is, “what it means” to be a man. This could include attempts to align male identity with a “pro-gender equality” orientation (or opinion; Bliuc et al., 2007), for example, by manipulating identity normative content to include men's expressions of support and engagement with women's rights (see Wiley et al., 2013). Further, endorsement of normative content by prominent group leaders has been shown to increase the likelihood group members adopt norms as central to their group identity (Haslam et al., 2015; see also Subašić et al., 2022). Future research could therefore examine the influence of such identity and leadership manipulations on men's need for morality, and the flow on effects for defensiveness and men's collective action intentions.

In all three samples our collective action measures (intentions to support women's rights and men's rights) were positively correlated (r's = 0.61, 0.63, 0.64). This finding suggests that, on average, participants may have viewed support for men's rights and women's rights as compatible commitments. It is possible that this finding reflects an issue with our measure of collective action intentions—which tapped into support for “men's rights” and “women's rights” broadly. This made it difficult to know the specific actions men had in mind when considering advocating on behalf of rights for women or rights for men. It is possible that some participants interpreted “men's rights” in the context of liberating men from restrictive patriarchal norms, a perspective that aligns with the promotion of women's rights (both pursuits aim to dismantle systemic gender inequalities). Conversely, some participants may have construed “men's rights” to mean protecting men from perceived threats or disadvantages. This divergence in understanding what constitutes men's rights could explain why the two measures are positively associated with each other overall, while they are related in opposing ways to men's need to defend their group's morality. As a result, it would be important for future work to assess a range of context-specific progressive and reactionary actions that men could support. For example, research could examine the likelihood that men attempt to protect other men from sexual assault allegations, or their support for programs designed to address “toxic” masculinity (see Mikołajczak et al., 2022, p. 15). We should also clarify that reactionary action should not be conceptualized as the reverse (inverse) of progressive action; there are many factors that would explain people's engagement in reactionary action that would not explain participation in progressive forms of action—and vice versa (Osborne et al., 2019; Choma et al., 2020).

In the present paper we focus on one particular type of morality need—men's need for moral-social acceptance from members of the outgroup (i.e., to be perceived as fair and moral by women; Shnabel and Nadler, 2008). However, research on morality-based threats has distinguished between threats to the ingroup's moral essence (“moral shame”; Allpress et al., 2014), and threats to the ingroup's moral reputation (“image shame”). Importantly, these distinct types of threat have divergent effects on intergroup outcomes (e.g., how advantaged group members react to conversations regarding inequality between groups; Eckerle et al., 2023). Thus, future work could explore the nuances around different kinds of identity threats (moral, meritocractic, status), and how they each shape people's participation in progressive vs. reactionary forms of collective action. Such research could also tease apart when advantaged group members will use a particular defensive strategy over another, and investigate the influence of each on support or opposition for actions to support disadvantaged or advantaged groups (see also, Shuman et al., 2024). Further, single item measures are limited in capturing the complexity of psychological constructs; future research should therefore seek to use more comprehensive measures of psychological defensiveness to improve validity and reliability.

Adopting a latent measurement approach using multi-group SEM allowed us to test a complex set of hypotheses while taking measurement error into account. However, given the correlational nature of the data we cannot make any claims regarding causation or the direction of effects. Nevertheless, the ordering of variables in our mediation analyses is consistent with past theory and research (Shnabel and Nadler, 2008; Noor et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2012; Shnabel et al., 2013). Despite this, it is possible that men's intentions to participate in collective action on behalf of their own group may motivate them to defend their group more strongly. Similarly, men's defensiveness (e.g., denying that men have caused harm) may further heighten their need to convince women group of their morality—and this need may, in turn, reinforce men's identification with their ingroup. It is likely that the relationships are dynamic and interdependent (see also Stott and Drury, 1999; Drury and Reicher, 2009; Thomas et al., 2009; Dixon et al., 2020). Indeed, it is established that social identities both produce, and are produced by, intra- and inter- group processes (Thomas et al., 2022). However, future experimental work is needed to untangle the relationships outlined here more concretely.

It is important to acknowledge that support for both progressive and reactionary forms of social change are not clearly divided across the boundaries of “advantaged” or “disadvantaged” group membership (Siem et al., 2013; Dixon et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2022). Advantaged group members often engage in action to support disadvantaged group members, and disadvantaged group members often engage in actions that seemingly go against their group interests (e.g., anti-feminist women; Mikołajczak et al., 2022). The current studies also did not account for how multiple group memberships—such as race or sexual orientation—intersect with gender identity to influence responses (Howard and Renfrow, 2014; Bowleg, 2017). A nuanced account of support for progressive and reactionary collective actions should therefore consider social identities that transcend traditional intergroup boundaries, as well as how people's membership in multiple groups intersect to shape their support for particular forms of social change (see also Cole, 2009; Nair and Vollhardt, 2020).

A final point concerns the generalizability of the current findings to other contexts of structural inequality between groups. It is important that models of collective action explain behavior across a variety of intergroup contexts (including those in non-Western/non-WEIRD countries; Henrich et al., 2010). Thus, future work should explore whether these results apply in other intergroup contexts.

The current findings bridge together the literature on conservative forms of collective action (Jost et al., 2017; Osborne et al., 2019; Becker, 2020) with work on group's psychological needs (Shnabel and Nadler, 2008; Siem et al., 2013; Nadler and Shnabel, 2015)—and the defensive strategies groups can take to address those needs (see Bilali and Vollhardt, 2019, for a review). This synthesis seems particularly important, given the rise of counter-movements from advantaged group members, and how these movements often involve assertions of the ingroup's morality (e.g., through competing for victim status; Young and Sullivan, 2016). Okuyan and Vollhardt (2022) note that advantaged group members' resistance to progressive social change need not be overtly violent to cause harm. That is, while defensive reactions may appear to be less harmful than more violent forms of intergroup resistance, they are insidious precisely because of how they subtly work to obscure the reality of group-based inequalities, and, as a result, cast doubt on the necessity of social change. The current findings indicate a need for further research to investigate how morality needs and defensiveness shape (and are shaped by) social movements that seek to challenge or uphold the status quo.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://osf.io/bk4md/files/osfstorage?view_only=6940e019f0114f04a32be8c56aee63dd.

The studies involving humans were approved by Flinders University Human Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

AB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ET: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LW: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2024.1356998/full#supplementary-material

1. ^There are a number of reasons for why this might have been the case. One reason might be that the nature of the threat manipulation may have been fairly inconsequential to male participants: It described one women's disclosure of sexual harassment. That is, given that allegations of men's wrongdoing are commonplace, and given the frequency of interactions between men and women in personal, professional, and political life, attempts to threaten men's need for morality experimentally may have been overpowered by the socio-political context in which this research was conducted.

2. ^Study 3 also manipulated the salience of men's social identification to provide causal evidence regarding the relationship between men's identification and their need for morality. We include information (method, results, discussion) regarding this manipulation in the Supplementary material.

3. ^Social identification used the same items across samples but was measured using different scale-points in Study 3.

4. ^Because of the relatively high mean for social identification (above the mid-point) in samples 1 and 2, a 9-point scale was used in sample 3 in an attempt to see whether there was greater variation in identification when more response options were available.

i. ^Further deviations from original pre-registration documentation

1. ^Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to test our hypothesized model rather than PROCESS as specified in our pre-registration document for Study 1.

2. ^We did not initially pre-register defensiveness as a latent variable in Study 1 and 2. Defensiveness as a latent variable was pre-registered in Study 3.

3. ^Collective action intentions (to promote [men/women]) were initially pre-registered as exploratory variables but are reported here as focal outcome variables.

4. ^The pre-registration documentation for Study 1 and Study 2 conceptualized an accusation of harm as the predictor variable and social identification as a moderator variable.

Allpress, J. A., Brown, R., Giner-Sorolla, R., Deonna, J. A., and Teroni, F. (2014). Two faces of group-based shame: moral shame and image shame differentially predict positive and negative orientations to ingroup wrongdoing. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 40, 1270–1284. doi: 10.1177/0146167214540724

Aquino, K., and Reed, I. I. A. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83, 1423–1440. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1423

Aydin, A. L., Ullrich, J., Siem, B., Locke, K. D., and Shnabel, N. (2019). Agentic and communal interaction goals in conflictual intergroup relations. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 7, 144–171. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v7i1.746

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 3, 193–209. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., and Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 71, 364–374. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364

Becker, J. C. (2020). Ideology and the promotion of social change. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 34, 6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.10.005

Bentler, P. M. (2007). On tests and indices for evaluating structural models. Pers. Individ. Dif. 42, 825–829. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.024

Bilali, R. (2013). National narrative and social psychological influences in Turks' denial of the mass killings of Armenians as genocide. J. Soc. Issues 69, 16–33. doi: 10.1111/josi.12001

Bilali, R., Tropp, L. R., and Dasgupta, N. (2012). Attributions of responsibility and perceived harm in the aftermath of mass violence. Peace Conflict: J. Peace Psychol. 18, 21–39. doi: 10.1037/a0026671

Bilali, R., and Vollhardt, J. R. (2019). Victim and perpetrator groups' divergent perspectives on collective violence: implications for intergroup relations. Polit. Psychol. 40, 75–108. doi: 10.1111/pops.12570

Bilewicz, M. (2016). The dark side of emotion regulation: historical defensiveness as an obstacle in reconciliation. Psychol. Inq. 27, 89–95. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2016.1162130

Bliuc, A. M., McGarty, C., Reynolds, K., and Muntele, D. (2007). Opinion-based group membership as a predictor of commitment to political action. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 37, 19–32. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.334

Bowleg, L. (2017). “Intersectionality: an underutilized but essential theoretical framework for social psychology,” in Palgrave Handbook of Critical Social Psychology (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 507–529.

Boyle, K., and Rathnayake, C. (2020). #HimToo and the networking of misogyny in the age of #MeToo. Feminist Media Stud. 20, 1259–1277. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2019.1661868

Branscombe, N. R., Ellemers, N., Spears, R., and Doosje, B. (1999). “The context and content of social identity threat,” in Social Identity: Context, Commitment, Content, eds. N. Ellemers, R. Spears, and B. Doosje (Oxford: Blackwell), 35–58.

Brown, X., Rucker, J. M., and Richeson, J. A. (2022). Political ideology moderates White Americans' reactions to racial demographic change. Group Proc. Intergroup Relat. 25, 642–660. doi: 10.1177/13684302211052516

Choma, B., Hodson, G., Jagayat, A., and Hoffarth, M. R. (2020). Right-wing ideology as a predictor of collective action: a test across four political issue domains. Polit. Psychol. 41, 303–322. doi: 10.1111/pops.12615

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences (2nd ed). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, 109–143.

Cole, E. R. (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am. Psychol. 64, 170–180. doi: 10.1037/a0014564

Craig, M. A., and Richeson, J. A. (2014). On the precipice of a “majority-minority” America: perceived status threat from the racial demographic shift affects White Americans' political ideology. Psychol. Sci. 25, 1189–1197. doi: 10.1177/0956797614527113

Craig, M. A., and Richeson, J. A. (2018). Majority no more? The influence of neighborhood racial diversity and salient national population changes on Whites' perceptions of racial discrimination. RSF: Russ. Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 4, 141–157. doi: 10.7758/rsf.2018.4.5.07

de Maricourt, C. D., and Burrell, S. R. (2022). #MeToo or #MenToo? Expressions of backlash and masculinity politics in the #MeToo era. J. Men's Stud. 30, 49–69. doi: 10.1177/10608265211035794

Dixon, J., Elcheroth, G., Kerr, P., Drury, J., Al Bzour, M., Subaši,ć, E., et al. (2020). It's not just “us” versus “them”: Moving beyond binary perspectives on intergroup processes. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 31, 40–75. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2020.1738767

Domen, I., Scheepers, D., Derks, B., and van Veelen, R. (2022). It's a man's world; right? How women's opinions about gender inequality affect physiological responses in men. Group Proc. Interg. Relat. 25, 703–726. doi: 10.1177/13684302211042669

Doosje, B., Branscombe, N. R., Spears, R., and Manstead, A. (1998). Guilty by association: When one's group has a negative history. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 75, 872–886. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.872

Dover, T. L., Major, B., and Kaiser, C. R. (2016). Members of high-status groups are threatened by pro-diversity organizational messages. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 62, 58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.10.006

Drury, J., and Reicher, S. (2009). Collective psychological empowerment as a model of social change: researching crowds and power. J. Soc. Issues 65, 707–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01622.x

Eckerle, F., Rothers, A., Kutlaca, M., Henss, L., Agunyego, W., and Cohrs, J. C. (2023). Appraisal of male privilege: on the dual role of identity threat and shame in response to confrontations with male privilege. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 108, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2023.104492

Ellemers, N., and Barreto, M. (2003). “The impact of relative group status: affective, perceptual and behavioural consequences,” in Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology: Intergroup Processes, 325–343.

Fisher, M. L., and Exline, J. J. (2006). Self-forgiveness versus excusing: the roles of remorse, effort, and acceptance of responsibility. Self Identity 5, 127–146. doi: 10.1080/15298860600586123

Flood, M. (2019). “Men and #Metoo: Mapping Men's responses to anti-violence advocacy,” in #MeToo and the Politics of Social Change (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 285–300.

Flood, M., Dragiewicz, M., and Pease, B. (2021). Resistance and backlash to gender equality. Australian J. Soc. Issues 56, 393–408. doi: 10.1002/ajs4.137

Hall, J. H., and Fincham, F. D. (2005). Self–forgiveness: the stepchild of forgiveness research. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 24, 621–637. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2005.24.5.621

Hall, R. J., Snell, A. F., and Foust, M. S. (1999). Item parcelling strategies in SEM: investigating the subtle effects of unmodeled secondary constructs. Organ. Res. Methods 2, 233–256. doi: 10.1177/109442819923002

Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D., and Platow, M. J. (2015). “Leadership: Theory and practice,” in APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology, Volume 2: Group Processes (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 67–94.

Hässler, T., Ullrich, J., Sebben, S., Shnabel, N., Bernardino, M., Valdenegro, D., et al. (2022). Need satisfaction in intergroup contact: a multinational study of pathways toward social change. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 122, 634–658. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000365

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., and Norenzayan, A. (2010). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature 466, 29–29. doi: 10.1038/466029a

Holt, T. J., Freilich, J. D., and Chermak, S. M. (2022). Examining the online expression of ideology among far-right extremist forum users. Terror. Polit. Viol. 34, 364–384. doi: 10.1080/09546553.2019.1701446

Howard, J. A., and Renfrow, D. G. (2014). “Intersectionality,” in Handbook of the Social Psychology of Inequality (Dordrecht: Springer), 95–121.

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equat. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Jost, J. T., Becker, J., Osborne, D., and Badaan, V. (2017). Missing in (collective) action: Ideology, system justification, and the motivational antecedents of two types of protest behaviour. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 26, 99–108. doi: 10.1177/0963721417690633

Kahalon, R., Shnabel, N., Halabi, S., and SimanTov-Nachlieli, I. (2019). Power matters: The role of power and morality needs in competitive victimhood among advantaged and disadvantaged groups. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 58, 452–472. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12276

Kende, A., Nyúl, B., Lantos, N. A., Hadarics, M., Petlitski, D., Kehl, J., et al. (2020). A needs-based support for#metoo: power and morality needs shape women's and men's support of the campaign. Front. Psychol. 11:593. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00593

Knowles, E. D., Lowery, B. S., Chow, R. M., and Unzueta, M. M. (2014). Deny, distance, or dismantle? how white americans manage a privileged identity. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9, 594–609. doi: 10.1177/1745691614554658

Kutlaca, M., Radke, H. R., Iyer, A., and Becker, J. C. (2020). Understanding allies' participation in social change: a multiple perspectives approach. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 50, 1248–1258. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2720

Leach, C. W., Ellemers, N., and Barreto, M. (2007). Group virtue: the importance of morality (vs. competence and sociability) in the positive evaluation of in-groups. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 93, 234. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.234

Leach, C. W., Van Zomeren, M., Zebel, S., Vliek, M. L., Pennekamp, S. F., Doosje, B., et al. (2008). Group-level self-definition and self-investment: a hierarchical (multicomponent) model of in-group identification. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 95, 144–165. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.144

Leach, C. W., Zeineddine, F. B., and Cehajić-Clancy, S. (2013). Moral immemorial: the rarity of self-criticism for previous generations' genocide or mass violence. J. Soc. Issues 69, 34–53. doi: 10.1111/josi.12002

Leidner, B., Castano, E., Zaiser, E., and Giner-Sorolla, R. (2010). Ingroup glorification, moral disengagement, and justice in the context of collective violence. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 36, 1115–1129. doi: 10.1177/0146167210376391

Lisnek, J. A., Wilkins, C. L., Wilson, M., and Ekstrom, P. D. (2022). Backlash against the #MeToo movement: how women's voice causes men to feel victimized. Group Proc. Intergroup Relat. 25, 682–702. doi: 10.1177/13684302211035437

Litman, L., Robinson, J., and Abberbock, T. (2017). TurkPrime.com: a versatile crowdsourcing data acquisition platform for the behavioural sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 49, 433–442. doi: 10.3758/s13428-016-0727-z

Mikołajczak, G., Becker, J. C., and Iyer, A. (2022). Women who challenge or defend the status quo: ingroup identities as predictors of progressive and reactionary collective action. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 52, 626–641. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2842

Nadler, A., and Shnabel, N. (2015). Intergroup reconciliation: Instrumental and socio-emotional processes and the needs-based model. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 26, 93–125. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2015.1106712

Nair, R., and Vollhardt, J. R. (2020). Intersectionality and relations between oppressed groups: intergroup implications of beliefs about intersectional differences and commonalities. J. Soc. Issues 76, 993–1013. doi: 10.1111/josi.12409

Noor, M., Shnabel, N., Halabi, S., and Nadler, A. (2012). When suffering begets suffering: the psychology of competitive victimhood between adversarial groups in violent conflicts. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 16, 351–374. doi: 10.1177/1088868312440048

Norton, M. I., and Sommers, S. R. (2011). Whites see racism as a zero-sum game that they are now losing. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 6, 215–218. doi: 10.1177/1745691611406922

Okuyan, M., and Vollhardt, J. (2022). The role of group versus hierarchy motivations in dominant groups' perceived discrimination. Group Proc. Intergroup Relat. 25, 54–80. doi: 10.1177/13684302211053543

Osborne, D., Jost, J. T., Becker, J. C., Badaan, V., and Sibley, C. G. (2019). Protesting to challenge or defend the system? A system justification perspective on collective action. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 49, 244–269. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2522

Peetz, J., Gunn, G. R., and Wilson, A. E. (2010). Crimes of the past: defensive temporal distancing in the face of past in-group wrongdoing. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 36, 598–611. doi: 10.1177/0146167210364850

PettyJohn, M. E., Muzzey, F. K., Maas, M. K., and McCauley, H. L. (2019). #HowIWillChange: engaging men and boys in the #MeToo movement. Psychol. Men Mascul. 20, 612–622. doi: 10.1037/men0000186

Radke, H. R., Kutlaca, M., Siem, B., Wright, S. C., and Becker, J. C. (2020). Beyond allyship: Motivations for advantaged group members to engage in action for disadvantaged groups. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 24, 291–315. doi: 10.1177/1088868320918698

Reicher, S., and Ulusahin, Y. (2020). “Resentment and redemption: on the mobilization of dominant group victimhood,” in The Social Psychology of Collective Victimhood, ed. J. R. Vollhardt (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 275–294.

Rivera-Rodriguez, A., Larsen, G., and Dasgupta, N. (2022). Changing public opinion about gender activates group threat and opposition to feminist social movements among men. Group Proc. Intergroup Relat. 25, 811–829. doi: 10.1177/13684302211048885

Rotella, K. N., and Richeson, J. A. (2013). Motivated to “forget” the effects of in-group wrongdoing on memory and collective guilt. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 4, 730–737. doi: 10.1177/1948550613482986

Selvanathan, H. P., Lickel, B., and Jetten, J. (2020). Collective psychological ownership and the rise of reactionary counter-movements defending the status quo. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 60, 587–609. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12418

Shepherd, L., Fasoli, F., Pereira, A., and Branscombe, N. R. (2018). The role of threat, emotions, and prejudice in promoting collective action against immigrant groups. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 447–459. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2346

Shnabel, N., and Nadler, A. (2008). A needs-based model of reconciliation: satisfying the differential emotional needs of victim and perpetrator as a key to promoting reconciliation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 94, 116–132. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.116

Shnabel, N., Nadler, A., Ullrich, J., Dovidio, J. F., and Carmi, D. (2009). Promoting reconciliation through the satisfaction of the emotional needs of victimized and perpetrating group members: the needs-based model of reconciliation. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 35, 1021–1030. doi: 10.1177/0146167209336610

Shnabel, N., Ullrich, J., Nadler, A., Dovidio, J. F., and Aydin, A. L. (2013). Warm or competent? Improving intergroup relations by addressing threatened identities of advantaged and disadvantaged groups. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 43, 482–492. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.1975

Shuman, E., van Zomeren, M., Saguy, T., Knowles, E., and Halperin, E. (2024). Defend, deny, distance, and dismantle: a new measure of advantaged identity management. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1–29. doi: 10.1177/01461672231216769

Siem, B., Von Oettingen, M., Mummendey, A., and Nadler, A. (2013). When status differences are illegitimate, groups' needs diverge: testing the needs-based model of reconciliation in contexts of status inequality. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 43, 137–148. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.1929

Spears, R., and Smith, H. J. (2001). Experiments as politics. Polit. Psychol. 22, 309–330. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00241

Stott, C., and Drury, J. (1999). The inter-group dynamics of collective empowerment: a social identity model of crowd behavior. Group Proc. Intergroup Relat. 2, 381–402. doi: 10.1177/1368430299024005

Subašić, E., Mohamed, S., Reynolds, K. J., Rushton, C., and Haslam, S. A. (2022). Collective mobilisation as a contest for influence: Leading for change or against the status quo? Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 52, 1111–1127. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2891

Sullivan, D., Landau, M. J., Branscombe, N. R., and Rothschild, Z. K. (2012). Competitive victimhood as a response to accusations of ingroup harm doing. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102, 778–795. doi: 10.1037/a0026573

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1979). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict,” in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds. W. G. Austin and S. Worchel (Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole), 33–37.

Teixeira, C. P., Spears, R., and Yzerbyt, Y. (2020). Is Martin Luther King or Malcom X the more acceptable face of protest? High-status groups' reactions to low-status groups' collective action. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 118, 919–944. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000195

Thomas, E. F., Duncan, L., McGarty, C., Louis, W. R., and Smith, L. G. (2022). MOBILISE: a higher-order integration of collective action research to address global challenges. Polit. Psychol. 43, 107–164. doi: 10.1111/pops.12811

Thomas, E. F., McGarty, C., and Mavor, K. I. (2009). Aligning identities, emotions, and beliefs to create commitment to sustainable social and political action. Personality and social Psychol. Rev. 13, 194–218. doi: 10.1177/1088868309341563

Thomas, E. F., and Osborne, D. (2022). Protesting for stability or change? Definitional and conceptual issues in the study of reactionary, conservative, and progressive collective actions. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 52, 985–993. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2912

Wang, Y. A., and Rhemtulla, M. (2021). Power analysis for parameter estimation in structural equation modelling: a discussion and tutorial. Adv. Meth. Pract. Psychol. Sci. 4, 1–17. doi: 10.1177/2515245920918253

Wenzel, M., Quinney, B., Wohl, M. J., Barron, A., and Woodyatt, L. (2023). Tensions between collective-self forgiveness and political repair. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 53, 1641–1662. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.3006

West, K., Greenland, K., and van Laar, C. (2021). Implicit racism, colour blindness, and narrow definitions of discrimination: why some white people prefer ‘All Lives Matter' to ‘black lives matter'. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 60, 1136–1153. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12458

Wiley, S., Srinivasan, R., Finke, E., Firnhaber, J., and Shilinsky, A. (2013). Positive portrayals of feminist men increase men's solidarity with feminists and collective action intentions. Psychol. Women Q. 37, 61–71. doi: 10.1177/0361684312464575

Woodyatt, L., and Wenzel, M. (2013). The psychological immune response in the face of transgressions: pseudo self-forgiveness and threat to belonging. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 49, 951–958. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2013.05.016

Young, I. F., and Sullivan, D. (2016). Competitive victimhood: a review of the theoretical and empirical literature. Curr. Opini. Psychol. 11, 30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.004

Keywords: collective action, social identity, defensiveness, advantaged group, morality needs, social change

Citation: Barron AC, Thomas EF and Woodyatt L (2024) #MeToo, #MenToo: how men's progressive and reactionary actions are shaped by defensiveness. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2:1356998. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2024.1356998

Received: 17 December 2023; Accepted: 27 May 2024;

Published: 26 June 2024.

Edited by:

Richard P. Eibach, University of Waterloo, CanadaReviewed by:

Matthew Hibbing, University of California, Merced, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Barron, Thomas and Woodyatt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anna C. Barron, YW5uYS5iYXJyb25AcHJpbmNldG9uLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.