94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Soc. Psychol., 13 February 2024

Sec. Attitudes, Social Justice and Political Psychology

Volume 2 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsps.2024.1337715

This article is part of the Research TopicRising Stars in Social Psychology 2023View all 8 articles

What happens when you express anger at work? A large body of work suggests that workers who express anger are judged to be competent and high status, and as a result are rewarded with more status, power, and money. We revisit these claims in four pre-registered, well-powered experiments (N = 3,852), conducted in the US, using the same methods used in previous work. Our findings consistently run counter to the current consensus regarding anger's positive role in obtaining status and power in the workplace. We find that when men and women workers express anger they are sometimes viewed as powerful but they are consistently viewed as less competent. Importantly, we find that angry workers are penalized with lower status compared to workers expressing sadness or no emotions. We explore the reasons for these findings both experimentally and descriptively and find that anger connotes less competence and warmth and that anger expressions at work are perceived as inappropriate, an overreaction, and as a lack of self-control. Moreover, we find that people hold negative attitudes toward workplace anger expressions, citing them as relatively more harmful, foolish, and worthless compared to other emotional expressions. When we further explore beliefs about what can be accomplished by expressing anger at work, we find that promoting one's status isn't one of them. We discuss the theoretical and applied implications of these findings and point to new directions in the study of anger, power, and the workplace.

What happens when you express anger at work? Is your anger met with respect and deference, or is resented, disregarded, or penalized? In an era characterized by upheavals in the labor market and abuses uncovered at multiple workplaces (e.g., Kantor and Twohey, 2019), questions about the costs and benefits of expressing anger at work or about the workplace have surged. In the last few years alone, journalistic accounts of the history and present status of anger in society and the workplace have captured public attention (e.g., Traister, 2018; Duhigg, 2019; Frank, 2019). These books and other accounts chronicle the uses and effects of anger, and advocate for more public expressions of anger, particularly women's anger (Cooper, 2018; Soraya, 2018; Traister, 2018). Leaders and celebrities in politics, sports, and film have also called for a broader acceptance of anger, and from a wider diversity of people (Obama, 2018; Williams, 2019).

Psychologists and other social scientists have long been interested in questions about anger at work, and their findings show why the expression of anger is so important in this context. First, they find that the right to express anger at work is reserved for workers who are high in power (e.g., Hochschild, 1983; Friijda, 1986; Averill, 1997; Scherer, 1999; Gibson and Callister, 2010). Second, they find that workers who are higher in power are more likely to exercise this right, i.e., to show their anger (Pierce, 1996; Sloan, 2004). Third, the association between anger and power has become a stereotype, such that when workers express anger, observers assume that they are high in status (Knutson, 1996; Hess et al., 2005; Hareli and Hess, 2010).

Observations of the “angry = high status” stereotype pointed psychologists to a related but substantially different question: could expressions of anger actually boost a person's perceived or real status at work? If this is the case, then anger may be an instrumental emotion for people who wish to gain status, and perhaps for members of underrepresented groups at work who wish to address workplace inequalities. In pursuit of these questions, a group of highly-cited studies (e.g., Tiedens, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008) led to the current received wisdom that “people who express certain emotions, such as anger... give the impression of competence, which leads to status conferral” (Bendersky and Pai, 2018, p. 187). That is, expressing anger leads to more status at work.

Notwithstanding some findings that anger is not rewarded for women at work (e.g., Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008; Marshburn et al., 2020), a takeaway from the literature remains that anger expressions in the workplace are generally rewarded (Gibson and Callister, 2010; Brescoll, 2016; Bendersky and Pai, 2018). This bottom line fits well with broad contemporary approaches to the study of anger, which characterize anger as an instrumental emotion that accomplishes different tasks across many contexts (van Kleef et al., 2004; Lerner and Tiedens, 2006; Hareli et al., 2009; Reifen Tagar et al., 2011; Hess, 2014).

The present research revisits these claims in four pre-registered, well-powered studies that use the same methods from now-classic studies that tested whether status and power are rewarded to individuals who express anger in the workplace. Our findings run counter to the current consensus regarding the positive role of anger. We do not find that anger functions as a catalyst for higher status in the workplace. Moreover, we find that anger is regarded more poorly than other emotional expressions like sadness or muted emotion. The only instance in which anger is considered positively relative to other emotions is when anger is expressed in reaction to another person's clear wrongdoing. These findings hold for both men and women expressing anger (vs. sadness or muted emotion) in the workplace. We explore and experimentally test reasons why anger does not improve status as previously believed. The data suggest that even though people assume that individuals expressing anger have higher status, they do not reward the expression of anger with higher status because they find their anger to be inappropriate, cold, an overreaction, and counter-instrumental for workplace goals.

While most recent accounts of anger in psychology and in the public discourse attempt to remake the image of anger–from a negative emotion into an instrumental emotion, and even into a positive emotion–our studies suggest a context in which anger is still negative. Specifically, anger is not instrumental for improving one's status at work.

It has long been observed by psychologists and other social scientists that high status grants a person more flexibility in their emotional expression (Hochschild, 1983; Averill, 1997; Hech and LaFrance, 1998). Anger in particular is allowed for people of higher status (Hochschild, 1983; Friijda, 1986; Ridgeway and Johnson, 1990; Averill, 1997; Scherer, 1999; Gibson and Callister, 2010). For example, Averill (1997) suggested that high power is an “entrance requirement” for expressing anger. In line with this view, the appraisal theory of emotion contends that “power potential” is a necessary requirement for anger expression (Friijda, 1986; Scherer, 1999). It is thus not surprising that people high in power also display more anger (Pierce, 1996; Sloan, 2004). For example, using the General Social Survey data (GSS) from 1996, Sloan (2004) analyzed 320 anger incidents in the workplace. She found that while high status workers reported experiencing less anger compared with low status workers, they were three times more likely to report displaying their anger.

Researchers are not alone in looking for patterns in emotion displays, and anger displays in particular. Lay individuals notice patterns of emotion and use them when making inferences about others (van Kleef, 2016; Barrett, 2017). For example, studies have found that people observe anger displays and infer that the angry person is dominant (Knutson, 1996; Hess et al., 2005; Hareli and Hess, 2010) or high status (Tiedens et al., 2000). Further, people report a belief that high status people do not just display but experience more anger (Conway et al., 1999; Tiedens et al., 2000; Hess et al., 2005), and they tend to judge anger displays from high status people as more appropriate (Hess et al., 2005).

Another line of work suggests that in addition to inferring status from anger displays, people may also confer status to those expressing anger. That is, people go beyond the assumption that an angry person is high status, to reward the angry person with more status, power, money, or the like. According to this idea, expressing anger can be instrumental because it leads others to grant status to the individual expressing anger. In line with this instrumental view of anger, in a classic study that was one of the first to highlight a positive role for anger, Tiedens (2001) found that anger expressions (vs. sadness) facilitate status conferral. Across four studies, she tested the role of anger in political and business settings and demonstrated that people confer more status to targets who express anger than to targets who express sadness.

For example, in one study, 91 business school students watched a video depicting a job interview. In the interview, the applicant discussed a negative event from his previous job and stated that he felt anger (vs. sadness) in response to that event. Participants were then asked to indicate how competent and likable they found the applicant, whether they would hire him, and to indicate how much status, power, independence, rank, and salary they thought the applicant should receive. Findings suggested that participants who viewed a sad applicant rated him as more likable and were more likely to hire him, compared with participants whose applicant expressed anger. However, Tiedens also found that participants whose applicant expressed anger rated the applicant as more competent, conferred more status to the applicant, and indicated that he should get paid more, compared with participants whose applicant expressed sadness (Tiedens, 2001). More recently, scholars found that this effect is true for low- but not high-intensity anger (Gaertig et al., 2019).

Tiedens' influential work marked a turning point in how anger was perceived and studied by psychologists. While the majority of work prior to Tiedens (2001) focused on the negative consequences of anger (Johnson, 1990; Berkowitz, 1993; Averill, 1997), much of the work today focuses on the positive consequences of anger. The present general consensus is that anger expressions in the workplace are largely rewarded (e.g., Gibson and Callister, 2010; Bendersky and Pai, 2018; Rafaeli et al., 2019). Closely following Tiedens' work were other lines of research on anger in the workplace, stipulating that anger may be an asset for accomplishing goals in negotiations (van Kleef et al., 2004; Sinaceur and Tiedens, 2006; Adam et al., 2010; Lelieveld et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012), and for enhancing one's credibility (Hareli et al., 2009). These positive accounts of anger expressions in the workplace dovetail with other accounts of the instrumental functions of anger outside of the workplace (e.g., Lerner and Tiedens, 2006; Hess, 2014). For example, Lerner and Tiedens (2006) argue that anger can be positive for decision making processes when it leads to reduced perceptions of risk (Lerner et al., 2003). In the context of intergroup conflict, a series of studies demonstrate that anger toward the outgroup can lead to increased support for risk-taking in peace negotiations (Halperin et al., 2011; Reifen Tagar et al., 2011).

Taken together, these findings are consistent with the social functional account of emotion (Friijda, 1986; Keltner and Gross, 1999), which focuses on the adaptive role of anger in attaining a person's goals. But from another vantage point, the findings are surprising; specifically, given the well-documented harmful effects of anger on health and wellbeing (Johnson, 1990; Phillips et al., 2006; Novaco, 2010; Williams, 2010), as well as anger's well-known relation to aggression (Berkowitz, 1993).

The shift in the theoretical zeitgeist from the negative to the positive effects of anger is particularly marked for research in the context of the workplace. Earlier work on anger in organizations that employed observational methods such as structured or semi-structured interviews (e.g., Fitness, 2000; Glomb, 2002; Booth and Mann, 2005) highlighted the negative consequences of anger for individuals, relationships, and organizations (Geddes and Callister, 2007; Gibson and Callister, 2010). For example, Glomb (2002) interviewed 74 employees about their experience of workplace aggression and concluded that anger is related to negative organizational and personal outcomes like reduced job satisfaction and performance, and to increased job-related stress and withdrawal behaviors like leaving work early to go home. Other studies outlined the negative effects of anger on interpersonal relationships in the workplace. For example, Booth and Mann (2005) analyzed 24 interviews and found that ten of their interviewees admitted to contemplating taking revenge on the person who acted angrily toward them. Friedman et al. (2004) examined 355 real online mediation disputes and found that anger expressions generated angry responses by the other party. Experimental evidence supports these observational findings on the harmful role of anger in interpersonal relationships. For example, van Kleef et al. (2004), found that in negotiations, participants who communicated anger to their opponents (Study 3) were less likely to achieve their goals compared with participants who communicated happiness. Others have found that workers who express anger are negatively evaluated as cold, unfriendly, and unlikable (e.g., Tiedens, 2001; Hess et al., 2005; Hareli and Hess, 2010; Dicicco, 2013).

Given psychology's re-orientation toward anger as a positive force in the workplace, and the calls for more public expressions of anger, we set out to test one of the foundational hypotheses about anger expressions at work. In four pre-registered, well-powered studies, we revisit the paradigms that tested whether expressing anger could help a worker gain status in the workplace. Specifically, we ask: do workers gain status when they express anger? Is anger perceived to be a signal of competence? And at the most basic level: do others like anger in the workplace?

Our findings provide consistent answers to these three questions. First, we find that workers do not gain status in the workplace when expressing anger. In fact, our findings suggest that anger expressions at work are penalized rather than rewarded. Second, we find that workers who expressed anger were judged as less competent. Third, even though people assume that workers expressing anger have higher status, they do not like it when workers express anger at work. Anger expressions were judged as inappropriate, cold, an overreaction, and counter-instrumental for workplace goals.

Psychologists who study emotion expressions at the workplace employ common methods and measures that allow them to build on previous work and compare results across different settings and participants (Rafaeli et al., 2019). For example, much of the work on emotion in the workplace has employed vignettes (either through text or videos) that depict a situation in a workplace environment in which a worker is described as having an angry, sad, or neutral reaction to a situation (e.g., Tiedens, 1998; Keltner and Gross, 1999; Tiedens et al., 2000; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008; Hareli and Hess, 2010; Brooks, 2011). When we embarked on this research, we designed a study with these now-classic vignette designs as a means of extending the research to new questions about emotion in the workplace. However, our findings (Study 1) did not support the general consensus of the literature that anger expressions are positive for status conferral. Consequently, we designed the next three studies to return to this basic question of whether anger is rewarded with more status in the workplace.

To reexamine this question, we conducted four studies using the same methods and materials used in previous work (e.g., Tiedens, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008). Across all studies, we experimentally manipulated the emotion being expressed (i.e., anger, sadness, or no/muted emotion). We measured status conferral similarly to Tiedens (2001) by asking participants to indicate how much status, power, independence, and respect the worker expressing the emotion deserved in the organization, as well as by asking participants to indicate the yearly salary they would pay the worker expressing the emotion.

To test the boundaries of our findings, we experimentally varied the gender of the worker expressing the emotion (i.e., men or women), the target of the emotional expression (i.e., another person, the circumstances), and the context in which the emotion was expressed (i.e., job interview, a normal workday). We experimentally varied the workers' gender to understand whether our findings held for both men and women. This is important given some work demonstrating that women are penalized for expressing anger while men are rewarded (e.g., Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008; Marshburn et al., 2020). We varied the target toward whom the emotion was expressed such that in Studies 1 through 3 the emotion (anger, sadness, or no emotion) was targeted at another colleague, while in Study 4 the emotion was targeted at the circumstances. This was important given that findings from previous work were inconsistent based on whether the target of the emotion was another worker (e.g., Tiedens, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008), or the circumstance (e.g., Tiedens, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008). Finally, to generalize our findings to different workplace scenarios, in Studies 1 & 2 the emotion was expressed in response to a norm violation in the workplace, while in Studies 3 & 4 the emotion was expressed in the context of a job interview.

In addition, we sought to explore explanations for our results. Previous work has pointed to a number of potential explanations for why anger may increase status conferral. For example, some suggest that anger expressions create an impression of competence, and that explains why angry protagonists are conferred more status (e.g., Tiedens, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008). Thus, in Studies 2 through 4 we experimentally tested whether the emotion being expressed influenced one's perceptions of the protagonist's competence, likability, perceived appropriateness, or levels of self-control. In Studies 3 & 4 we also explored descriptive explanations, such as participants' assessments of the emotional expression (e.g., the extent to which it was bad-good), and of the instrumental functions of anger and sadness expressions in the workplace.

We used linear regression in all analyses. Throughout our work, we make multiple comparisons in our analyses. The multiple comparisons inflate our alpha and increase the chance of false-positive discoveries. Thus, we assessed our p-values against the most stringent Bonferroni correction. The Bonferroni corrected alpha threshold for each study is as follows: Study 1: α = 0.025 (0.05/2); Study 2: α = 0.002 (0.05/24); Study 3: α = 0.0034 (0.05/13); Study 4: α = 0.004 (0.05/11). All of our p-values reported as significant at the p < 0.05 level throughout the manuscript are also significant according to these corrected levels of significance. We report the uncorrected p-values for simplicity. We pre-registered all four studies using the “As Predicted” website and included pre-registration of hypotheses and analytic strategy. For replication codes and pre-registrations see Open Science Framework.

Study 1 was designed as a conceptual replication of the classic sadness vs. anger expression studies of workplace emotion. We designed it as a conceptual and not an exact replication given other research goals: as mentioned above, we hoped to replicate the classic findings that anger would improve status en route to testing extensions of this effect. When we were unable to replicate those findings, we changed the design in Studies 2–4 to hew as closely as possible to those classic studies.

To determine the size of our sample we conducted a simulated power analysis using findings obtained by Tiedens (2001) in Study 4. Using DeclareDesign software, we considered sample sizes between 50 and 2,000 in increments of 50 and simulated each 500 times. Based on this analysis (for code and figure see Supplementary material), we found that to detect a main effect for emotion powered at 80% we would need 75 participants in each condition. Given that this was our first study, we decided to be cautious and increase our power to 99% by recruiting 800 participants (200 participants in each condition). Participants were invited to participate via Amazon Mechanical Turk in exchange for $1.95. While 894 participants started the survey, 803 completed it and were included in our analyses (45.1% women, 54.4% men, 0.5% other, mean age = 36.88, SD = 11.04).

We employed a 2 (emotion: anger or sadness) X 2 (gender: men or women) experimental design. Participants were invited to read a brief scenario describing a norm violation in the workplace:

“Please imagine that you have just started working in a new organization. These are your first few days, and you are trying to understand the rules of conduct. Today you are joining your department's weekly meeting, where you discuss the team's task for the following week. The meeting begins on time, with all of the department workers taking their seat around the table, and pulling out pens and binders to take notes. You notice that one worker pulls out a laptop instead and opens it”.

At this point, participants were randomly assigned to conditions. To manipulate emotion, we changed the described emotion the protagonist was expressing. In the expression of anger conditions participants read:

“Watching this person opening the laptop, one of your colleagues, Amanda/John, looks angry. Her/his mouth presses into a frown, and S/he narrows her/his eyes. Amanda/John raises her/his voice above the other workers and says: ‘how many times do we need to remind everyone of the rules on note-taking in these meetings. This makes me just so angry”'.

In the expression of sadness conditions participants read:

“Watching this person opening the laptop, one of your colleagues, Amanda/John, looks sad. Her/his mouth twists, and her/his eyes look pained. Amanda/John waits for a silence and then quietly says: ‘how many times do we need to remind everyone of the rules on note-taking in these meetings. This makes me just so sad”'.

To vary the gender of the protagonist expressing the emotion we named that person either John or Amanda. Then, participants were asked to answer two reading comprehension questions to ensure that they read the scenario carefully. Participants who failed one of these questions were looped back to the beginning of the experiment and asked to read the scenario again and answer the same two questions again. To safeguard our random assignment, we included all participants in the final analysis regardless of whether they passed or failed the reading comprehension questions. Following this, participants were asked to answer a series of questions containing our outcomes of interest, as well as provide socio-demographic information.

Following Tiedens (2001) participants were asked to indicate on a scale of 1 (none) to 11 (a great deal) how much status, power, independence and respect the protagonist (i.e., Amanda or John) deserves in the organization. We grouped the mean score of these four items to create a status conferral index (α = 0.93).

Participants were asked to indicate what position they thought the protagonist had in the organization. They could select from four options: 1 = S/he is a subordinate; 2 = S/he is an equal of the other meeting attendees; 3 = S/he is the boss; 4 = I'm not sure what Amanda/John's position is. In our analysis, we re-coded answer 4 so it would appear as an NA.

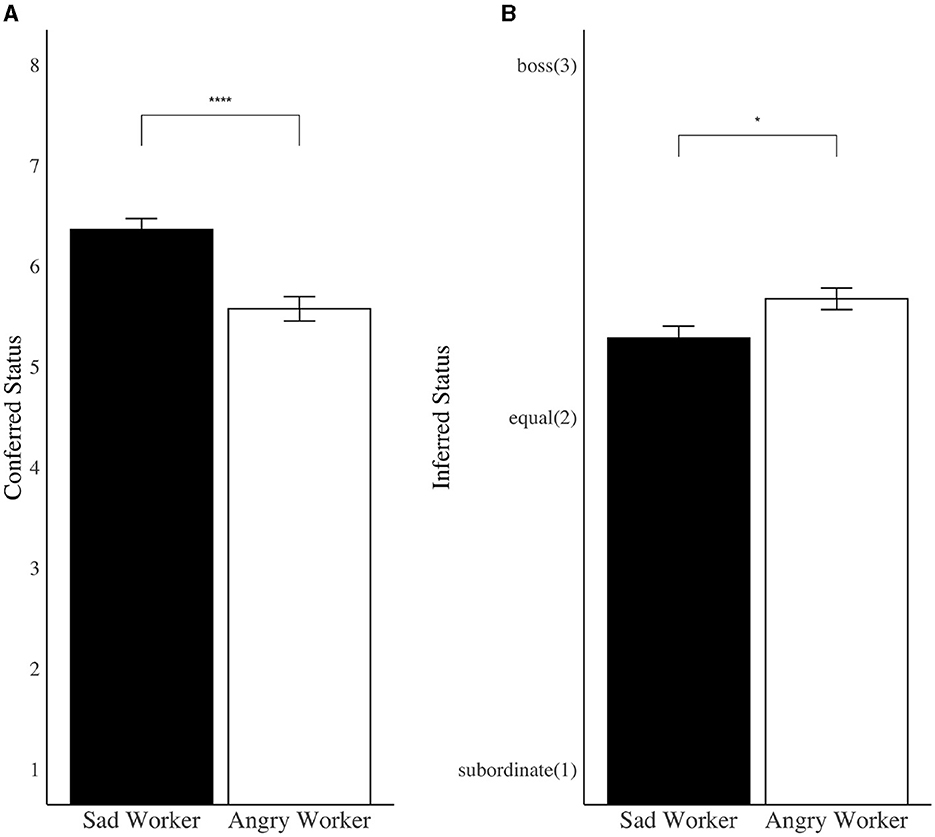

For status conferral, participants believed that the angry worker deserved less status (M = 5.58, SD = 2.38) relative to participants who observed a sad worker (M = 6.37, SD = 2.16) (β = −0.79, SE = 0.16, p < 0.001). For inferred status, participants who observed an angry worker believed that they had more status (M = 2.34, SD = 0.54) relative to participants who observed a sad worker (M = 2.22, SD = 0.61) (β = 0.11, SE = 0.05, p = 0.01) (see Figures 1, 2). Thus, while participants inferred that an angry protagonist already had higher status, they felt that the sad protagonist deserved more status, relatively speaking. Additionally, we find that the gender of the protagonist did not influence participants' inferences about status in general or differentially in reaction to the emotion expressed (see Supplementary material).

Figure 1. Study 1. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001. Participants conferred less status to the angry worker relative to the sad worker (A), but inferred that the angry worker had more status relative to the sad worker (B).

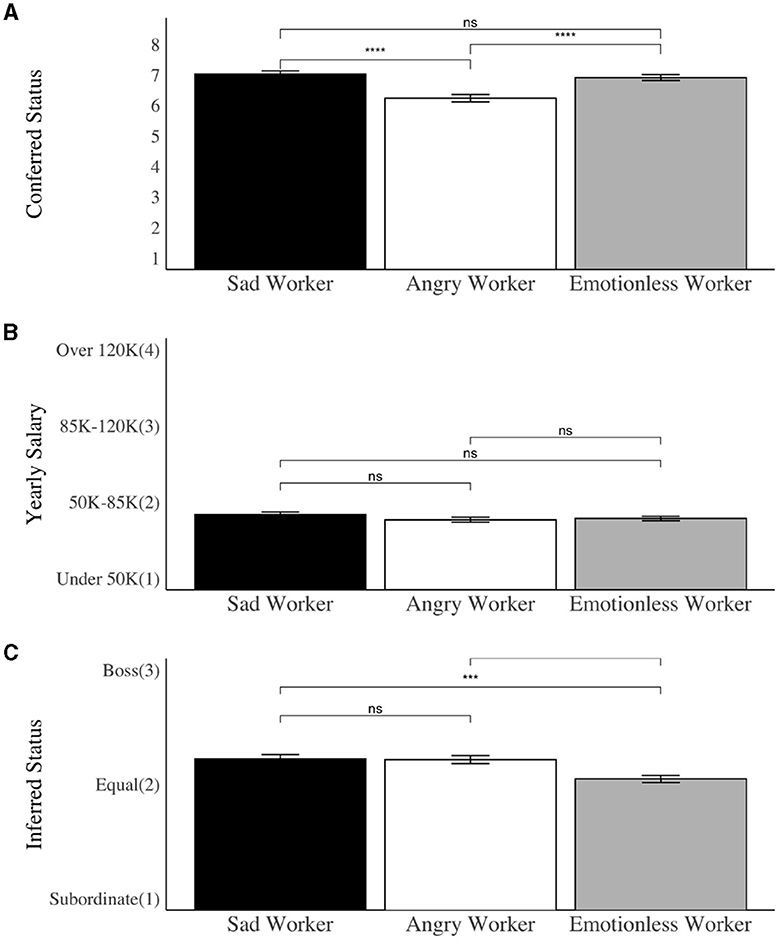

Figure 2. Study 2. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Participants conferred less status to the angry worker relative to the sad and emotionless workers (A), but did not think that the workers deserved different yearly salaries (B). Participants also inferred that both the angry and sad workers had higher status relative to the emotionless worker (C).

Taken together, our results support previous findings that expressions of anger at work lead individuals to assume that the angry worker already has high status-at least, higher relative to a worker expressing sadness. However, contrary to previous accounts, participants thought that angry protagonists deserved less status than those expressing sadness. These findings, which were strong and significant within similar paradigms of previous work, led us to replicate the study with a control condition and additional outcome measures from previous research on anger at work.

The goal of Study 2 was to replicate and extend the findings from Study 1 in several ways. First, we wanted to determine the direction of our effects: were participants punishing the angry protagonist by conferring less status to them? Or were participants rewarding the sad protagonist? To determine this, we added a third condition where the protagonist showed no emotion. Second, we added another measure for status conferral used in previous work (e.g., Tiedens, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008). Participants were asked to indicate what the protagonist's yearly salary should be. Third, to ensure that participants recognized the emotion expressed by the protagonist, we added a manipulation check asking participants to rate the extent to which the protagonist was feeling anger and sadness. Fourth, previous work provides several possible explanations that may shed more light on the nature of our effects. For example, some suggest that people confer more status to those expressing anger because they perceive them as more competent (e.g., Tiedens, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008; Backor, 2009; Dicicco, 2013; Marshburn et al., 2020), and in control (e.g., Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008). Others find the degree to which one's emotional reactions are perceived as appropriate important for forming judgments (e.g., Kelly and Hutson-Comeaux, 2000; Hutson-Comeaux and Kelly, 2002). To test whether these explain our effects we added measures of competence, control, and appropriateness.

As in Study 1, we aimed for 200 participants in each condition. Participants were recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk in exchange for $0.70. Given reported problems with participants on Amazon Mechanical Turk at the time (Dennis et al., 2019; Webb and Tangney, 2022), we opted for a larger sample. Thus, 1,603 participants started the survey, 1,411 completed it, and were included in our analyses (43.4% women, 56.4% men, 0.2% other, mean age = 36.08, SD = 11.71).

We employed a three (emotion: anger, sadness, or emotionless) X 2 (gender: men or women) experimental design. Participants read the same scenario as in Study 1 depicting a norm violation scenario in the workplace. For the muted emotion/no emotion condition following the first part of the vignette, participants read:

“Watching this person opening the laptop, one of your colleagues, John, keeps looking. John turns to that person and says: ‘Would you mind turning off the computer. There is a rule about this. It is what it is.”'

Then, as in Study 1, participants were asked to answer two reading comprehension questions to ensure that they read the scenario carefully, and were looped back to the start of the experiment if they failed one of the two questions. All participants were included in the final analysis regardless of the number of times they failed the check. Following the reading comprehension check, participants were asked to answer a series of questions containing our outcomes of interest. Finally, they rated the protagonist's emotion as a manipulation check and provided socio-demographic information about themselves.

As in Study 1 (α = 0.93).

As in Study 1.

Following Tiedens (2001), participants were asked to indicate what would be the yearly salary they would pay the protagonist (1 = under $50,000/year, 2 = between $50,000 and $85,000/year, 3 = between $85,000 and $120,000/year, 4 = over $120,000/year).

Participants were asked to rate the protagonist on the trait dimensions of competent-incompetent, knowledgeable-ignorant, warm-cold, and likable-not likable, using 11-point trait semantic differential scales (r's = 0.86 and 0.83 for competence and warmth, respectively).

Following Brescoll and Uhlmann (2008), participants were asked to assess the extent to which they perceived the protagonist as a (1) out-of-control or (11) in-control person.

Following Kelly and Hutson-Comeaux (2000), participants were asked to judge the appropriateness of the protagonist's response to the situation by rating the degree to which the scenario depicted an appropriate/inappropriate and an over- or under-reaction to the situation on an 11-point scale with (1) anchored as appropriate or under-reaction and (11) anchored as inappropriate or overreaction.

Following Lewis (2000) and Tiedens et al. (2000), participants were asked to rate the extent to which the protagonist was feeling anger, apathy, sadness, and joy, on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 9 (to a great extent).

Participants who observed an angry worker were significantly more likely to think they felt anger (M = 7.72, SD = 1.28) relative to participants who observed a sad (M = 5.55, SD = 2.38) or emotionless workers (M = 5.43, SD = 2.30) (β = 2.29, SE = 0.13, p < 0.001). Similarly, participants who observed a sad worker were significantly more likely to think they felt sadness (M = 6.66, SD = 2.11) relative to participants who observed angry (M = 3.39, SD = 2.53) or emotionless workers (M = 3.04, SD = 2.46) (β = 3.62, SE = 0.15, p < 0.001). Finally, participants who observed an emotionless worker were significantly more likely to think they felt apathy (M = 3.92., SD = 2.57) relative to participants who observed angry (M = 3.39, SD = 2.69) or sad workers (M = 3.22, SD = 2.52) (anger dummy: β = −0.54, SE = 0.17, p = 0.002; sad dummy: β = −0.71, SE = 0.17, p < 0.001). All tests suggest that our manipulations were understood as presented.

We find that the angry worker was conferred less status relative to the sad and emotionless workers (see Table 1 for means, SDs, and regression output). We do not find differences in conferred status between sad and emotionless workers (see Figure 2A). For our second status outcome, yearly salary, we find no differences in judgments of salary among the three conditions (see Table 1; Figure 2B).

We also find that participants inferred higher status for both the angry and sad workers relative to the emotionless worker. Unlike Study 1, there were no differences in inferred status between the angry and sad workers (see Table 1; Figure 2C). Workers' gender did not significantly predict conferred or inferred status as a main effect or in the interaction with emotion (for regression output see Supplementary material).

These results support Study 1's findings, that while individuals assume that the angry protagonists have high status, they don't confer them more status as a result of their anger expression. Further, Study 2 extends our findings from Study 1 by pointing out that angry workers are “punished” for their anger expression as they are awarded less status relative to sad or emotionless workers. Once again, our results held for both men and women expressing anger vs. sadness or muted/no emotion.

We next tested whether expressions of anger led to higher ratings of competence relative to expressions of sadness or muted emotion (see Table 2). We find that participants thought that the angry worker was less competent relative to the sad and emotionless workers.

Further, we find that participants judged the angry worker as less warm than the sad and emotionless workers. Ratings of warmth did not differ between sad and emotionless workers, suggesting that only angry workers were perceived as less warm (see Table 2).

We tested whether expressions of anger were perceived as inappropriate or as an overreaction relative to expressions of sadness or muted emotion. For inappropriateness, both the angry and the sad workers were perceived as more inappropriate relative to the emotionless worker. The angry workers' response was judged as significantly more inappropriate than the sad worker (see Table 2). Similarly, for overreaction, participants thought the angry and sad workers overreacted relative to the emotionless worker. Again, anger expressions were viewed as significantly more of an overreaction than sadness expressions.

Participants perceived the angry and sad workers as less in control relative to the emotionless worker, but angry workers were rated as less in control relative to sad workers (Table 2).

In keeping with other analyses, we found that gender did not predict ratings of competence, warmth, appropriateness or overreaction, or control, either overall or as an interacted effect with the emotion expressed by workers (for regression output see Supplementary material).

Taken together, Studies 1 & 2 run counter to the literature and the present-day zeitgeist. We don't find evidence supporting the notion that anger in the workplace is instrumental for gaining status. Furthermore, our findings suggest that anger expressions at the workplace are perceived as inappropriate, and angry workers are judged as less competent, likable, and out of control. These negative evaluations of the worker and their emotional reactions provide some insight as to why participants choose to “punish” the protagonist by granting them less status.

Another set of results standing in contradiction to the current literature is the comparability of reactions to the emotions expressed by men and by women. In these two studies, women were not punished more, or men rewarded more, for expressions of anger. This is surprising given the influential work by Brescoll and Uhlmann (2008) arguing that women's anger is regarded differently than men's anger. Building on Tiedens (2001) and Brescoll and Uhlmann (2008) used a similar vignette paradigm and demonstrated that when women expressed anger at work in the same way as men, they were granted less status compared to men expressing anger or women expressing sadness (Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008). Across both of our studies, both angry men and women were conferred less status, power, independence, and respect at work following the expression of anger. Thus, in Study 3 we sought to challenge these null findings by replicating more exactly the classic gender and emotion research paradigms pioneered by Tiedens (2001) and Brescoll and Uhlmann (2008).

Our goals for Study 3 were (1), to test the robustness of our results that angry workers are conferred less status, and (2), to test whether the similarity of reactions to men and women was particular to the vignettes used in Studies 1 & 2. Therefore, we used a classic workplace vignette designed by scholars interested in the emotion-gender-status relationship (Tiedens, 1998, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008; Dicicco, 2013). The vignette depicts a job interview in which the protagonist describes how, together with a colleague, they lost an important account. The protagonist describes the incident as causing them to feel either angry or sad. We kept the vignette as similar as possible to that used in previous work (Tiedens, 1998, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008; Dicicco, 2013). However, to be consistent with the two previous studies we ran, we modified the target of the angry/sad reaction. While in the classic work of Tiedens (2001) and Brescoll and Uhlmann (2008) the anger expression was targeted at the circumstances, in this scenario, we targeted the anger expression at another worker who was blamed for losing the account.

A third goal of Study 3 was to probe additional explanations for why participants might confer less status to the angry protagonist. Recent work suggests that people's evaluations of emotion are associated with the perceived utility of the emotions (Netzer et al., 2018). For example, people who perceive anger to be instrumental in attaining goals also hold a more positive attitude toward anger. Thus, in Study 3 we sought to measure participants' evaluations of the utility of emotions expressed by the worker protagonist.

To ensure that we were powered to detect the interactive effects obtained by Brescoll and Uhlmann (2008) we conducted a simulated power analysis using their findings from Study 1. Using declare design software, we considered sample sizes between 50 and 2,000 in increments of 50 and simulated each 500 times. Based on this analysis (see Supplementary material), we found that to detect an interaction powered at 80% we would need 50 participants, to detect a main effect for gender powered at 80%, we would need 250 participants, whereas to detect a main effect for emotion powered at 80%, we would need 500 participants. This suggests that to detect an effect we would need about 125 participants in each condition. Given that this was our first study using this vignette, we opted for 200 participants in each condition on the Prolific platform. Participants were invited to participate in the study in exchange for $1.00. Of 813 participants who started the survey, 795 completed and were included in our analyses (47.7% women, 50.4% men, 1.9% other, mean age = 33.7, SD = 12.1).

We employed a 2 (emotion: anger or sadness) X 2 (gender: men or women) experimental design. Following Tiedens (1998, 2001) and Brescoll and Uhlmann (2008), Tiedens et al. (2000), participants were invited to read a scenario depicting a job interview:

The purpose of this study is to examine negative questions in a job interview. During the hiring process, interviewers often ask applicants questions that require the applicant to say something negative about himself or herself. We would like to present you with a scenario depicting a job interview, and specifically responses to questions that require applicants to describe something negative about their previous work experience. After reading this scenario, we will ask you a number of questions regarding the applicant.

Interviewer: Could you describe a time when things did not go so well in your previous job?

At this point, participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions. To manipulate the gender of the protagonist, as in Studies 1 & 2, we named that person Amanda or John:

Amanda/John: Sure. One story comes to mind immediately. A few months after I started my previous position, me and my colleague had an important meeting at a client's offices, which was on the other side of town We took my colleague's car, and even though we had no spare time, my colleague made a stop on our way for a personal errand. We were terribly late to the meeting, and the client was very upset with us. Eventually they decided to go with another firm.

Interviewer: How did you feel at the time?

To manipulate emotion, we changed the emotion the protagonist was described as expressing. In the anger conditions participants read:

Amanda/John: I felt angry. I can still remember my mouth pressing into a frown, my eyes narrowing, and raising my voice at my colleague when speaking about it.

In the sadness conditions participants read:

Amanda/John: I felt sad. I can still remember my mouth twisting, my eyes probably looked pretty pained, and then I quietly spoke to my colleague about it.

Then, as in our previous studies, participants were asked to answer two reading comprehension questions to ensure that they read the scenario carefully and were looped back to read the scenario again if they did not. All participants were included in the final analysis. Following this, participants were asked to answer a series of questions containing our outcomes of interest, and a manipulation check. Finally, participants were asked to provide their socio-demographic information.

As in Study 1 (α = 0.91).

As in Study 1.

As in Study 2.

As in Study 2 (r's = 0.73 and 0.74 for competence and warmth, respectively).

As in Study 2.

As in Study 2.

Following Netzer et al. (2018), participants were first reminded of the protagonist's emotional response to losing the client. Then, they were asked to assess the protagonist's feelings on 7-point semantic differential scales (1 = negative evaluation adjectives; 7 = positive evaluation adjectives), focusing on five evaluative dimensions: bad-good, harmful-useful, foolish-wise, worthless-valuable, and redundant-necessary. We reverse-coded all five scales so that a high number signifies a more negative assessment.

As in Study 2.

Participants who observed an angry worker were significantly more likely to think they felt anger (M = 7.78, SD = 1.25) relative to participants who observed a sad worker (M = 5.28, SD = 2.02). Participants who observed a sad worker were significantly more likely to think they felt sadness (M = 8.03, SD = 1.26) relative to participants who observed an angry worker (M = 4.44, SD = 2.17). All tests suggest that our manipulations were understood as presented.

For conferred status and yearly salary, the effects were positive but insignificant, suggesting that angry workers were neither penalized nor rewarded for their anger (see Table 3). For inferred status, just as in Study 1, participants who observed an angry protagonist believed they had more status relative to participants who observed a sad protagonist (see Table 3). Status conferred or inferred did not depend on the gender of the worker; men vs. women were not awarded or perceived to have more status in general or in combination with a particular emotion (see Supplementary material).

Angry workers were not perceived as more competent relative to sad workers (see Table 4). However, angry workers were perceived as less warm relative to sad workers.

A worker's anger expression was rated similarly inappropriate relative to the sad worker's expression (see Table 4). However, anger expressions were perceived to be significantly more of an overreaction compared to sadness expressions.

Angry workers were perceived as more in control than sad workers, but not to a significant extent (see Table 4).

Participants assessed expressions of anger as more harmful, foolish, and worthless, relative to expressions of sadness (see Table 5).

We found no evidence from interacted regressions that participants' ratings of warmth, competence, inappropriateness, overreaction, control, and assessment of emotional reactions depended on the gender of the protagonist (for regression output see Supplementary material).

Study 3 extends our previous findings by testing the effects of anger expressions in the workplace in a different workplace context—a job interview rather than a meeting among colleagues. In addition, the new interview scenario featured emotional reactions to a rather large mistake (losing an account) as opposed to a more minor norm violation (using laptops in a meeting). We find that, consistent with the meeting scenario in Study 1 (but not Study 2), people assume angry protagonists have a higher status relative to sad protagonists.

This study adds more evidence to the notion that individuals recognize angry colleagues as being higher status, but don't reward angry expressions with more status. We find that participants don't penalize angry protagonists, but they don't reward them either. Consistent with our findings from Studies 1 & 2, we find that angry protagonists are judged as colder, and their reaction is perceived as an overreaction. We also find that participants assess expressions of anger at work as harmful, foolish, and worthless, relative to sadness expressions.

Diverging from our findings in Studies 1 & 2, we find that angry protagonists are not perceived as less competent or less in control relative to sad protagonists and that their emotional reaction is judged equally appropriate to a sad reaction. These diverging findings may be because in this scenario the angry reaction was in response to a costly mistake by a colleague that had very negative repercussions for the protagonist (i.e., losing a client). Thus, unlike in Studies 1 & 2 where anger may have been perceived as unwarranted, in this scenario an angry response appears to be perceived as appropriate. Finally, as in our previous studies but in contrast to previous literature, we did not find that these effects differed when judging men vs. women who were expressing anger or sadness. That is, the gender of the worker protagonists did not seem to matter.

Our goal for Study 4 was to test whether the slightly divergent results found in Study 3 were due to the new context introduced (i.e., job interview), or the fact that anger was warranted given the colleague's behavior. To do so, we changed the Study 3 vignette to be a near replica of the vignette originally used in previous work (Tiedens, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008). Specifically, in Study 4 the emotion expressed (i.e., anger or sadness) was not in response to a colleague's wrongful behavior or mistake, and therefore was targeted at the circumstances rather than at another worker. Another goal of Study 4 was to explore descriptive explanations that could shed light on why people don't reward anger with more status and sometimes penalize it. We focused on how people perceive anger and sadness expressions in the workplace. We were interested in whether people thought expressing anger in the workplace was instrumental or detrimental to work-related goals such as gaining status or relationships with others. Additionally, given the null findings regarding gender differences, we wanted to directly assess participants' beliefs about the masculinity and femininity of expressing anger and sadness (LaFrance and Hecht, 2000; Shields and Shields, 2002; Ellemers, 2018).

As in previous studies, we opted for 200 participants in each condition. Participants were recruited via Prolific in exchange for $1.00. While 845 participants started the survey, 842 completed it, and were included in our analyses (47.1% women, 51.3% men, 1.6% other, mean age = 35.5, SD = 12.8).

We employed a 2 (emotion: anger or sadness) X 2 (gender: men or women) experimental design. Participants read the same scenario as in Study 3, except that the protagonist's colleague was not responsible for the loss of the client. Instead, participants learned that the protagonist and the colleague were late to the meeting because of bad traffic conditions. Thus, this scenario replicated more closely previous work by others (i.e., Tiedens, 1998, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008) where the anger was targeted at the circumstances rather than at the colleague. The remaining procedure was identical to previous studies. We added an additional descriptive measure regarding participants' perceptions of the instrumental functions of anger and sadness at the workplace, as well as a measure capturing participants' beliefs about the masculinity and femininity of expressing anger and sadness.

As in Study 1 (α = 0.93).

As in Study 1.

As in Study 2.

As in Study 2.

As in Study 2.

As in Study 3.

As in Study 2.

Participants were asked to rate 12 phrases regarding anger and sadness on a 1 (disagree) to 7 (agree) scale. Phrases were intended to convey whether participants thought expressing anger and sadness were instrumental for work-related goals such as gaining status or maintaining relationships. Sample items include: “expressing anger/sadness in the workplace is costly to one's relations with one's colleagues”.

Participants were asked to rate on a scale of 1 (disagree) to 7 (agree) the extent to which expressing anger and sadness at the workplace is masculine and feminine.

Participants who observed an angry worker were significantly more likely to think they felt anger (M = 7.62, SD = 1.24) relative to participants who observed a sad worker (M = 4.16, SD = 1.99). Participants who observed a sad worker were significantly more likely to think they felt sadness (M = 8.06, SD = 1.15) relative to participants who observed an angry worker (M = 4.96, SD = 2.09).

To a statistically significant degree, participants conferred less status to angry workers relative to sad workers. Angry workers were also given a smaller salary, although this difference was not statistically significant. Participants believed that angry workers were higher status than sad workers, but this difference was not significant (see Table 6).

In this study, we found a significant negative interaction between gender and emotion when predicting status conferral (β = −0.52, SE = 0.24, p = 0.03). Follow up analyses suggest that angry men protagonists (M = 5.89, SD = 1.72) were conferred the least status, compared with sad men protagonists (M = 6.61, SD = 1.74) and with angry (M = 6.45, SD = 1.80) and sad (M = 6.65, SD = 1.73) women protagonists. In contrast to the consensus of previous literature, participants punished angry men by conferring them lower status. For yearly salary, the interaction coefficient was positive and significant (β = 0.16, SE = 0.08, p = 0.05), however, follow up analyses found no significant simple differences among conditions on proposed yearly salary. For inferred status, we found no significant prediction for gender as a main effect or in the interaction term.

Anger expressions were perceived as more inappropriate and as an overreaction, relative to sadness expressions (see Table 7).

Angry workers were perceived as significantly less in control than sad workers (see Table 7).

Expressing anger was assessed more negatively on all five dimensions relative to expressing sadness. That is, expressing anger was perceived as more bad, harmful, foolish, worthless, and redundant, relative to expressing sadness (see Table 8).

We found no evidence from interacted regressions that participants' ratings of inappropriateness, overreaction, and assessments of emotional reactions depended on the gender of the protagonist. We did find a significant negative interaction between gender and emotion when predicting judgments of self-control (β = −0.62, SE = 0.30, p = 0.04). Follow up analyses suggest that angry men workers (M = 6.56, SD = 2.22) were perceived as less in control compared with sad men workers (M = 7.34, SD = 2.23) and with angry (M = 7.13, SD = 2.25) and sad (M = 7.29, SD = 2.24) women workers (see also Supplementary material).

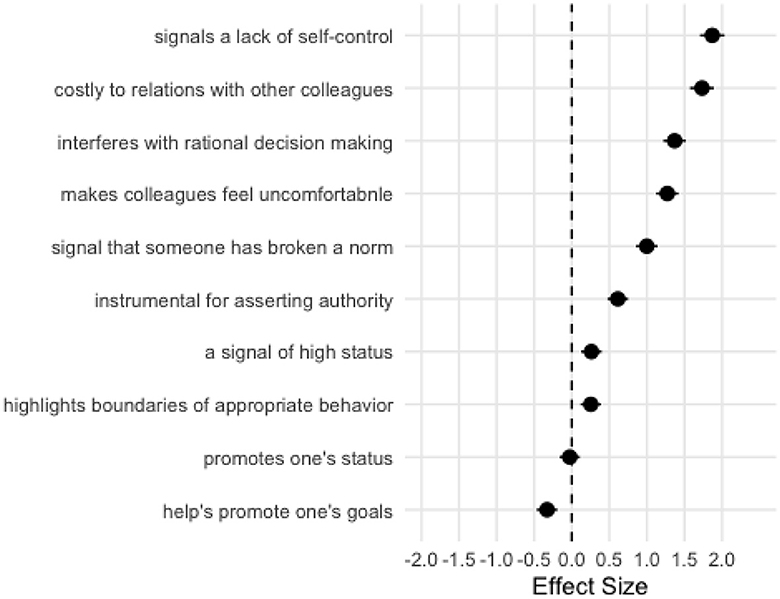

Next, we examined participant's perceptions of the instrumental functions of expressing anger and sadness at work (see Figure 3). Participants' perceptions aligned with the experimental findings accrued throughout this research. First, we find that similar to our experimental data, participants perceived anger expressions at work to be a stronger signal of high status (M = 2.57, SD = 1.61) and for asserting authority (M = 2.59, SD = 1.60), relative to sadness expressions (signaling status: M = 2.35, SD = 1.34; asserting authority: M = 2.07, SD = 1.36). However, participants did not rate anger expressions at work to be instrumental for promoting one's status (M = 2.21, SD = 1.37) relative to sadness expressions (M = 2.23, SD = 1.26). Thus, we find that while participants agree that anger expressions signal higher status, they don't believe that anger is instrumental for boosting one's status at work.

Figure 3. Results from Study 4. Participants perceive that high status workers are more likely to express anger, but they do not think it is instrumental for boosting one's status. They also perceive anger to be personally and socially destructive. Anger is perceived as instrumental mainly for signaling that a norm has been broken.

Second, we examined how participants perceived anger and sadness expressions at work to affect interpersonal relationships. We find that, to a statistically significant extent, participants perceived expressions of anger to be more costly to one's relationship with colleagues (M = 5.62, SD = 1.33), to make colleagues feel more uncomfortable (M = 6.19, SD = 1.16), and to signal a greater lack of self-control (M = 5.39, SD = 1.50), relative to expressions of sadness (relationships: M = 3.98, SD = 1.61; uncomfortable: M = 5.24, SD = 1.40; self-control: M = 3.62, SD = 1.69). Third, we find that anger expressions are to a significant extent perceived to be harmful for promoting work-related goals (M = 2.42, SD = 1.44) and for rational decision making (M = 5.74, SD = 1.48) relative to sadness expressions (goals: M = 2.69, SD = 1.39; decision making: M = 4.50, SD = 1.62).

One interesting domain where anger expressions were perceived as instrumental was for signaling norms. Participants perceived anger expressions to be a stronger signal that someone broke a social norm (M = 4.83, SD = 1.58), and a stronger signal of boundaries of appropriate behavior (M = 4.03, SD = 1.67), relative to sadness expressions (social norms: M = 3.90, SD = 1.56; appropriate behavior: M = 3.81, SD = 1.27).

Although participants didn't judge protagonists differently according to their gender, they recognized that expressions of anger and sadness are gendered. Specifically, expressing anger at the workplace was perceived to be significantly more masculine (M = 3.83, SD = 1.89) than feminine (M = 2.83, SD = 1.45) [t(841)=-16.75, p < 0.001], whereas expressing sadness at the workplace was perceived to be significantly more feminine (M = 3.80, SD = 1.71) than masculine (M = 2.69, SD = 1.71) [t(841) = 17.62, p < 0.001].

Taken together, the results of Study 4 are consistent with our previous findings, especially those of Studies 1 & 2. We find that angry workers are conferred less status, and in this study, we find that this is especially true for angry men. Angry expressions at work are perceived to be inappropriate and an overreaction, and the worker expressing them is perceived to be out of control. Participants also judge the angry response as bad, harmful, foolish, worthless, and redundant.

Study 4 provides descriptive evidence for how anger at work is perceived, regardless of the workplace scenarios depicted in the experiment. We find that anger is perceived to be costly to one's work-related relationships, making others feel uncomfortable and signaling a lack of self-control. Anger is also deemed as unprofessional as it interferes with rational decision making. One instance where anger is perceived as instrumental is for signaling that a norm has been broken. Most importantly, with regards to the central outcome of interest– status–we find that to some extent anger at work signals high status and authority (although these effects are relatively weak), but it is not perceived to be instrumental for boosting one's status at work. Finally, we find that perceptions regarding the expressions of anger and sadness haven't changed over the years, and are still gendered.

Over the past decade, many psychologists have recast anger as a positive emotion, and have noted its positive effects in society and particularly in the workplace. While the majority of scholarly work prior to Tiedens (2001) considered workplace anger as a negative phenomenon with detrimental consequences for individuals, relationships, and organizations (Glomb, 2002; Friedman et al., 2004; Booth and Mann, 2005; Geddes and Callister, 2007; Gibson and Callister, 2010), the current theoretical and empirical landscape highlights its positive consequences for status, goal accomplishment, and more. The takeaway from this literature is that workers judge other workers who express anger to be high status (Knutson, 1996; Tiedens, 1998; Hess et al., 2005; Hareli and Hess, 2010) and competent (Tiedens, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008), and as a result reward them with more status, power, and money (Lewis, 2000; Tiedens, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008; Gaertig et al., 2019).

Across four studies we revisited these claims. Our findings consistently run counter to current received wisdom regarding anger's positive role in obtaining status and power at the workplace. While previous work argues that angry workers are perceived to be high status (Knutson, 1996; Averill, 1997; Hess et al., 2005; Hareli and Hess, 2010), our experimental and descriptive findings only lend partial support to this argument. We find that when workers express anger they are sometimes inferred as being high power and sometimes not. Participants self-reported that anger expressions at work are a signal of high status, but they reported at significantly and substantively higher levels of agreement that anger signaled negative qualities, such as a lack of self-control, destructive relationships with colleagues, and interference with rational decision making. Previous work suggests that angry workers are judged as competent (Lewis, 2000; Tiedens, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008). However, we consistently find the opposite. In our work, angry workers were judged to be less competent compared to sad or emotionless workers. Most importantly, previous work argues that angry workers are rewarded with more status (Tiedens, 2001; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008; Gaertig et al., 2019). However, we find that angry workers are penalized and given less status compared with sad or emotionless workers.

Why do people confer less status to angry individuals? Our findings suggest that expressing anger is evaluated negatively in several ways. First, we find that anger connotes less competence and warmth, compared to other emotional expressions. Second, we find anger expressions at work are perceived as inappropriate, and the worker expressing them is evaluated as having an overreaction and being out of control. Third, we find negative attitudes toward workplace anger expressions, such that people find it relatively more harmful, foolish, and worthless. When we further explore beliefs about what expressing anger (vs. sadness) can accomplish at work, we find that promoting one's status isn't one of them.

Our set of results should not be considered an anomaly. We obtained these findings while closely tracking the methods and materials used in previous work. We used vignettes as our stimuli, following the scenarios used in the classic work of Tiedens (2001) and Brescoll and Uhlmann (2008). Across all four studies we used the same measures from previous work to examine outcomes related to status and competence. In addition, to determine sample sizes and ensure that we were powered enough to detect interaction effects, we conducted power analyses based on the findings obtained in classic work and recruited more than double the sample from those estimates. Importantly, we followed open science practices that allow for full transparency and reproducibility of the findings. Our studies were all pre-registered, including the methods, measures, and analyses we ran, and these pre-registrations along with the code and data can be found on the Open Science Framework (OSF).

The experimental findings also distinguish the extent to which anger at work is rewarded, penalized, or ignored–whether men and women can “get away” with anger at work. The experimental design that is needed to answer this question is one that has not been used in previous work. Specifically, the design we use in Study 2, which crosses the gender of the worker with the emotion they are expressing—anger vs. sadness vs. muted emotion – is the only design that can test whether anger is penalized or sadness is rewarded. Previous work examined the anger-status relation by either comparing angry workers to sad workers (e.g., Tiedens, 2001), comparing angry men workers to angry women workers (e.g., McCormick-Huhn and Shields, 2021), or by comparing angry workers to emotionless workers (e.g., Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008). While these comparisons provide useful information, they cannot determine whether workers who express anger are penalized, or whether workers who express other emotions (e.g., sadness) are rewarded. We find that sad workers are awarded similar status to emotionless workers, suggesting that expressions of sadness are neither rewarded or penalized. However, anger is penalized–workers expressing anger are granted less status than sad or emotionless workers.

Another set of results that stands in contrast to previous work is the comparability of reactions to both angry men and women. The classic work of Brescoll and Uhlmann (2008) suggests that women are penalized when expressing anger. More recently, McCormick-Huhn and Shields (2021) compared angry white women to angry white men and found that angry women were granted more status than angry men. Thus, while Brescoll and Uhlmann (2008) argue that angry women are penalized, McCormick-Huhn and Shields (2021) argue that they are rewarded. In the current set of studies, we don't find that angry women are rewarded or penalized compared with angry men. Instead, we find that both men and women are equally penalized for their anger.

What might explain these stark differences in findings regarding gender and anger at work? At first glance, it seems like these findings contradict a large body of previous work on gender and anger at work. Two possible explanations are that gendered norms of anger expression have changed over time since previous studies were conducted, or that we used different samples compared to previous studies. These two explanations seem unlikely. First, we note that our measurement of the gendered expression of emotion indicates that expressing anger at the workplace is still perceived to be more masculine than feminine. Thus, gendered norms of anger have not changed. Second, like previous studies we used non-student samples, making it unlikely that our diverging findings are the result of different sample populations.

To explain our divergent findings regarding gender and anger at work, we think it is important to take a closer look at what has been characterized as a wide and consistent body of evidence suggesting that women are punished for anger expressions at work. The previous body of work might be best characterized as a highly influential group of initial studies (Tiedens, 1998, 2001; Tiedens et al., 2000; Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008), a few of which demonstrated that women were punished and men were rewarded for anger using small samples. Following these foundational findings, a group of published studies investigated questions that followed this initial finding, such as whether these results differed for non-white men and women (Livingston et al., 2012; McCormick-Huhn and Shields, 2021). These studies did not use experimental designs that could directly replicate the initial findings. There is a third group of studies in this literature that were not published (Backor, 2009; Dicicco, 2013), some of which did test the initial questions about gender and anger but did not replicate the initial findings. Thus, taken together, our findings for gender and anger contradict the earliest group of studies but not subsequent work. Our findings suggest that foundational ideas about who is penalized and rewarded for anger at work need more scrutiny, and we hope this paper restarts that research program. Thus, we call for a reexamination of whether an angry woman can get ahead. But we also call for a reexamination of whether angry workers can get ahead more generally.

A critical future direction involves building out our incomplete understanding of the expression of anger at work by explicitly incorporating race and intersectionality into our study methods. The classic work by Tiedens (2001) and Brescoll and Uhlmann (2008) implicitly studied the anger of white men and women by never mentioning race. Our work closely followed these previous accounts and thus focused on the anger-status relation among white people. An important question for future research is whether these findings are true for Black women and men expressing anger. Research by Livingston et al. (2012) finds that Black women leaders were favorably evaluated when enacting agentic behaviors. McCormick-Huhn and Shields (2021) extend this finding by examining how angry Black women are evaluated at work. In two studies (Studies 2 & 3), they compared reactions to angry Black women with reactions to angry white men. In parallel to their evidence for reactions to angry white women, they find that angry Black women are conferred more status than angry white men. However, it is unclear whether angry Black women are rewarded for their anger, or whether like angry white men they are not penalized for their anger. With regards to angry Black men, unpublished findings by Banks (2019) suggest that angry Black men are negatively evaluated compared with angry white men, but only by racially prejudiced white men.

An important limitation of our studies, as well as other related studies is the use of vignette designs to assess the role of anger expressions in the workplace. First, the vignette approach allows us to examine reactions to “state anger”, or passing flashes of anger. Our findings cannot generalize to reactions to anger from a person who is known to you as prone to anger, which is “trait anger”. Thus, future research is needed to address the interplay between trait and state anger, and how these affect status conferral and judgments regarding competence in the workplace. Second, the vignette approach is artificial in many ways, thus further research is needed to examine whether the negative consequences of anger expression occur in actual workplace environments. Conducting this kind of field research may be particularly challenging. However, a recent study by Mobasseri (2018) provides a possible route. In her work, Mobasseri (2018) analyzed a corpus of 710 employee emails from a mid-sized technology firm to uncover what emotions are expressed at the workplace, and whether there are rewards or penalties when one aligns their emotions toward other workers. Future research could use this type of data along with HR records to examine whether employees who express more anger in their emails are more likely to be promoted or fired.

Notwithstanding our acknowledged limitations, these clear and consistent findings represent a strong countervailing perspective to current views of anger as a positive instrumental emotion. These studies highlight one context where anger may not serve or promote an individual's status, regardless of whether they are a man or a woman. While most of the recent accounts of anger in scholarly journals as well as in the public discourse tend to highlight the positive consequences of expressing anger, our studies suggest that in the context of the workplace, anger may not lend the same positive outcomes.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

The studies involving humans were approved by Princeton IRB Committee #10576. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

RP: Writing—original draft, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization. EL: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. We acknowledge funding to EL from Princeton University. We also acknowledge funding to RP from the Azrieli Foundation.

We thank John-Henry Pezzuto for superb research assistance. We thank Deborah Prentice for her invaluable feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript. We also thank Lasse Suonperä Liebst and Sanaz Mobasseri for excellent feedback via Altheia.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2024.1337715/full#supplementary-material

Adam, H., Shirako, A., and Maddux, W. W. (2010). Cultural variance in the interpersonal effects of anger in negotiations. Psychol. Sci. 21, 882–889. doi: 10.1177/0956797610370755

Averill, J. R. (1997). “The emotions: an integrative approach,” in Handbook of Personality Psychology, eds R. Hogan, J. Johnson, and S. Briggs (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 513–541.

Backor, K. (2009). Anger in the Workplace: Effects of Gender and Frequency in Context on Social and Job-Related Outcomes (Dissertation). Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States.

Banks, A. J. (2019). To Be Angry or Not to Be Angry: Are Black Political Candidates Emotionally Disadvantaged. Princeton, NJ. Available online at: https://spia.princeton.edu/events/be-angry-or-not-be-angry-are-black-political-candidates-emotionally-disadvantaged

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How Emotions are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. New York, NY: Mariner Books.

Bendersky, C., and Pai, J. (2018). Status dynamics. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 5, 183–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104602

Berkowitz, L. (1993). Aggrssion: Its Causes, Consequences, And control. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Booth, J., and Mann, S. (2005). The experience of workplace anger. Leaders. Org. Dev. J. 26, 250–262. doi: 10.1108/01437730510600634

Brescoll, V. L. (2016). Leading with their hearts? How gender stereotypes of emotion lead to biased evaluations of female leaders. Leaders. Q. 27, 415–428. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.02.005

Brescoll, V. L., and Uhlmann, E. L. (2008). Can an angry woman get ahead?: status conferral, gender, and expression of emotion in the workplace. Psychol. Sci. 19, 268–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02079.x

Brooks, D. J. (2011). Testing the double standard for candidate emotionality: voter reactions to the tears and anger of male and female politicians. J. Polit. 73, 597–615. doi: 10.1017/S0022381611000053

Conway, M., Di Fazio, R., and Mayman, S. (1999). Judging others' emotions as a function of the others' status. Soc. Psychol. Q. 62, 291–305. doi: 10.2307/2695865

Cooper, B. (2018). Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower. New York, NY: St. Martin's Publishing Group.

Dennis, S. A., Goodson, B. M., and Pearson, C. (2019). Virtual Private Servers and the Limitations of IP-Based Screening Procedures: Lessons From the MTurk Quality Crissis of 2018.

Dicicco, E. (2013). Competent but Hostile: Intersecting Race/Gender Stereotypes and the Perceptions of Women's Anger in the Workplace (Dissertation). Penssylvania State University, State College, PA, United States.

Duhigg, C. (2019). The Real Roots of American Rage. The Atlantic. Available online at: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/01/charles-duhigg-american-anger/576424/

Ellemers, N. (2018). Gender stereotypes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69, 275–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011719

Fitness, J. (2000). Anger in the workplace: an emotion script approach to anger episodes between workers and their superiors, co-workers and subordinates. J. Organ. Behav. 21, 147–162.

Frank, T. (2019). America's Anger Problem Runs Deeper Than Donald Trump. Vanity Fair. Available online at: https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2019/08/americas-anger-problem-runs-deeper-than-donald-trump

Friedman, R., Anderson, C., Brett, J., Olekalns, M., Goates, N., and Lisco, C. C. (2004). The positive and negative effects of anger on dispute resolution: evidence from electronically mediated disputes. J. Appl. Psychol. 89, 369–376. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.2.369

Gaertig, C., Barasch, A., Levine, E. E., and Schweitzer, M. (2019). When does anger boost status? J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 85. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2019.103876

Geddes, D., and Callister, R. R. (2007). Crossing the line(s): a dual thereshold model of anger in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 32, 721–746. doi: 10.5465/amr.2007.25275495

Gibson, D. E., and Callister, R. R. (2010). Anger in organizations: review and integration. J. Manage. 36, 66–93. doi: 10.1177/0149206309348060

Glomb, T. M. (2002). Workplace anger and aggression: informing conceptual models with data from specific encounters. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 7, 20–36. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.7.1.20

Halperin, E., Russell, A. G., Dweck, C. S., and Gross, J. J. (2011). Anger, hatred, and the quest for peace: anger can be constructive in the absence of hatred. J. Conflict Resol. 55, 274–291. doi: 10.1177/0022002710383670

Hareli, S., Harush, R., Suleiman, R., Cossette, M., Bergeron, S., Lavoie, V., et al. (2009). When scowling may be a good thing: the influence of anger expressions on credibility. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 39, 631–638. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.573

Hareli, S., and Hess, U. (2010). What emotional reactions can tell us about the nature of others: an appraisal perspective on person perception. Cognit. Emot. 24, 128–140. doi: 10.1080/02699930802613828

Hech, M. A., and LaFrance, M. (1998). License or obligation to smile: the effect of power and sex on amount and type of smiling. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 24, 1332–1342. doi: 10.1177/01461672982412007

Hess, U. (2014). “Anger is a positive emotion,” in The Positive Side of Negative Emotions, ed G. W. Parrot (New York, NY: The Guilford Press).

Hess, U., Adams, R., and Kleck, R. (2005). Who may frown and who should smile? Dominance, affiliation, and the display of happiness and anger. Cognit. Emot. 19, 515–536. doi: 10.1080/02699930441000364

Hutson-Comeaux, S. L., and Kelly, J. R. (2002). Gender stereotypes of emotional reactions: how we judge an emotion as valid. Sex Roles 10. doi: 10.1023/A:1020657301981

Johnson, E. H. (1990). The Deadly Emotions: The Role of Anger, Hostility, and Aggression in Health and Emotional Well-Being. New York, NY: Praeger Publishers.

Kantor, J., and Twohey, M. (2019). She Said: Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story That Helped Ignite a Movement. London: Penguin Press.

Kelly, J. R., and Hutson-Comeaux, S. L. (2000). The appropriateness of emotional expression in women and men: the double-bind of emotion. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 15, 515–528.

Keltner, D., and Gross, J. J. (1999). Functional accounts of emotions. Cognit. Emot. 13, 467–480. doi: 10.1080/026999399379140

Knutson, B. (1996). Facial expressions of emotion influence interpersonal trait inferences. J. Nonverb. Behav. 20, 165–182. doi: 10.1007/BF02281954

LaFrance, M., and Hecht, M. (2000). “Gender and smiling: a meta analysis,” in Gender and Emotion: Social Psychological Perspective, ed A. M. Fischer (New York, NY: Cambridge University Pres), 118–142.

Lelieveld, G.-J., Van Dijk, E., Van Beest, I., and Van Kleef, G. A. (2012). Why anger and disappointment affect other's bargaining behavior differently: the moderating role of power and the mediating role of reciprocal and complementary emotions. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 38, 1209–1221. doi: 10.1177/0146167212446938

Lerner, J. S., Gonzalez, R. M., Small, D. A., and Fischhoff, B. (2003). Effects of fear and anger on perceived risks of terrorism. Psychol. Sci. 14:7. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01433

Lerner, J. S., and Tiedens, L. Z. (2006). Portrait of the angry decision maker: how appraisal tendencies shape anger's influence on cognition. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 19, 115–137. doi: 10.1002/bdm.515

Lewis, K. M. (2000). When leaders display emotion: how followers respond to negative emotional expression of male and female leaders. J. Org. Behav. 21(Spec Issue), 221–234. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(200003)21:2<221::AID-JOB36>3.0.CO;2-0

Livingston, R. W., Rosette, A. S., and Washington, E. F. (2012). Can an agentic black woman get ahead? The impact of race and interpersonal dominance on perceptions of female leaders. Psychol. Sci. 23, 354–358. doi: 10.1177/0956797611428079

Marshburn, C. K., Cochran, K. J., Flynn, E., and Levine, L. J. (2020). Workplace anger costs women irrespective of race. Front. Psychol. 11:3064. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.579884

McCormick-Huhn, K., and Shields, S. A. (2021). Favorable evaluations of black and white women's workplace anger during the era of# metoo. Front. Psychol. 12:396. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.594260

Mobasseri, S. (2018). Emotions at Work: Norms of Emotional Expression and Gender Dynamics in Workplace Communication. Berkeley, CA: University of California.

Netzer, L., Gutentag, T., Kim, M. Y., Solak, N., and Tamir, M. (2018). Evaluations of emotions: distinguishing between affective, behavioral and cognitive components. Pers. Individ. Dif. 135, 13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.06.038

Novaco, R. W. (2010). “Anger and psychopathology,” in International Handbook of Anger, eds M. Potegal, G. Stemmler, and C. Spielberger (New York, NY: Springer), 465–497.

Phillips, L. H., Henry, J. D., Hosie, J. A., and Milne, A. B. (2006). Age, anger regulation and well-being. Aging Mental Health 10, 250–256. doi: 10.1080/13607860500310385