95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Soc. Psychol. , 08 February 2024

Sec. Intergroup Relations and Group Processes

Volume 2 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsps.2024.1305150

The extant literature recognizes national identity as a pivotal factor motivating both individual and collective actions to tackle environmental problems. Yet, prior research shows mixed evidence for the relationship between national identity and environmentalism. Here, we propose a theoretical approach that articulates distinctions between different forms of national identity and their differential associations with environmental attitudes and behaviors. Specifically, we argue that it is key to differentiate national identification, which reflects a positive attachment to one's country and ties to other compatriots, from national narcissism, which reflects viewing one's country as exceptional and deserving of special treatment. In contrast to national identification, national narcissism is consistently associated with lower environmental concern and predicts support for anti-environmental policies. We show that this is likely due to national narcissism being linked to belief in climate-related conspiracy theories, support for policies that challenge external pressures yet present the nation in a positive light (e.g., greenwashing), and focusing on short-term benefits for the nation. Extending past individual-level findings, we report a pre-registered analysis across 56 countries examining whether national narcissism is also linked to objective indices of lower environmental protection at the country level of analysis. Results revealed a negative relationship between countries' environmental performance and country-level national narcissism (while adjusting for national identification and GDP per capita). We discuss the theoretical and practical implications of our approach and the country-level findings for advancing research in the field.

The global challenge of climate change has driven research into identifying factors that can influence pro-environmental actions and policy support (Dunlap and Brulle, 2015; Van Lange et al., 2018). Readiness for collective action often stems from strong group attachment (Van Zomeren, 2013), which has led scholars to argue that strong social identities might motivate collective action for combating global environmental problems (Fritsche et al., 2013; Postmes et al., 2013).

Among many social identities that an individual can hold, national identity stands out because it ties generations through shared symbols, language, history, and culture (Easterbrook and Vignoles, 2012; Anderson, 2016). National identity is consequential as governments typically create policies to address social crises, and strong positive attachment to one's nation can motivate support for such efforts due to shared values, collective responsibility, sense of pride and heritage (Kalin and Sambanis, 2018; Schlicht-Schmälzle et al., 2018; Dovidio et al., 2020; Huddy et al., 2021), including pro-environmental efforts and policy support (Fielding and Hornsey, 2016).

However, research regarding national identity and environmentalism has shown mixed results. For example, national identification correlated positively with pro-environmental action in New Zealand, where environmental care is an important part of national identity (Milfont et al., 2020), but negatively with environmental concern in Australia (Ray, 1980), while it was positively associated with denial of environmental problems in the US (Feygina et al., 2009), and unrelated to climate change denial in Turkey (Kiral Ucar et al., 2023). While the content of national identity, which may or may not include pro-environmental components, could potentially explain these mixed effects to some extent (cf. Fielding and Hornsey, 2016), we propose a novel perspective. We argue that distinguishing between different forms of citizens' national identity (Cichocka, 2016; Cichocka and Cislak, 2020) could elucidate their attitudes and the level of environmental performance in their countries.

National identity can take various forms (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009; Bonikowski and DiMaggio, 2016). For example, researchers distinguish between patriotism (attachment to one's nation) and nationalism (striving for dominance over other nations; Kosterman and Feshbach, 1989), with the latter predictive of intergroup antagonism. This is an example of approaches that tend to converge in the conclusion that different forms of identification are related to different intergroup outcomes (see also Schatz et al., 1999; Roccas et al., 2008). A broader perspective that can be applied beyond the national context (including organizational, or political)—and thus has the potential to serve as a unifying framework—distinguishes between collective narcissism and ingroup identification. Collective narcissism is a belief that one's group is exceptional and deserving of privileged treatment but underappreciated by others (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009), while ingroup identification can be understood as satisfaction with ingroup membership, feelings of bonds and solidarity with ingroup members (Tajfel et al., 1971). National narcissism and national identification (i.e., collective narcissism and ingroup identification applied to the national context) share a positive view of the national ingroup. However, controlling for their overlap (e.g., by including them as joint predictors in a regression analysis) allows us to observe their unique effects. In line with this idea, accumulating evidence shows that national narcissism and national identification are linked to different antecedents and outcomes (Cichocka, 2016; Cislak and Cichocka, 2023).

National narcissism, in contrast to national identification, is underpinned by frustrations of personal control (Cichocka et al., 2018) or self-worth (Golec de Zavala et al., 2019; Golec De Zavala et al., 2020), which are characteristic of anxious forms of psychological attachment (Marchlewska et al., 2022). National narcissism is regulated by protecting the national image (resulting in suspicion, devaluation of others, and striving for supremacy) and by enhancing the national image (resulting in ingroup glorification or demands for recognition and privileged treatment). This mirrors the dynamics of individual narcissism, but individual narcissism tends to be regulated by the protection and enhancement of the individual—rather than the collective—self (Back et al., 2013). Needs for image enhancement and protection mean that national narcissism tends to predict support for actions that either boost one's nation's image (Główczewski et al., 2022) or display outgroup hostility, especially under threat (Golec de Zavala et al., 2013; Cichocka and Cislak, 2020; Federico et al., 2023). Importantly, the effect of national narcissism on such tendencies have been observed in various contexts (Cislak and Cichocka, 2023). Similar effects have also been observed for other forms of collective narcissism, suggesting that they might be less dependent on identity content (cf. Abou-Ismail et al., 2023).

We argue that psychological needs for image protection and enhancement typical of national narcissism can translate into lower levels of environmentalism. We argue that this is due to (1) climate-related conspiracy beliefs and science skepticism, (2) support for policies that challenge external pressures, (3) prioritizing national image enhancement over people, and (4) focusing on short-term rather than long-term benefits.

Environmental efforts typically require that the public trusts scientific evidence (Gundersen et al., 2022). Yet, national narcissism seems to be linked with science skepticism. One reason for this is that the motives of national image protection and enhancement are associated with conspiracy beliefs (Cichocka et al., 2016; Cislak et al., 2021a; Sternisko et al., 2023). Conspiracy theories can serve as a justification for blaming others for any national disadvantages. Furthermore, if people believe that powerful outgroups conspire against them, it pictures the nation as important enough for others to want to undermine it (Cichocka et al., 2016). Finally, conspiracy beliefs may serve to signal ingroup devotion, and thus conspiracy theories are often relied on as tools for political mobilization (Marie and Petersen, 2022).

In the environmental domain, national narcissism predicted belief in climate change conspiracy theories (such as “climate change is a hoax”) which mediated the effect of national narcissism on science skepticism: those higher in national narcissism were more prone to support climate conspiracy beliefs, and in turn less likely to accept statements reflecting the current state of science (such as “human CO2 emissions cause climate change”; Bertin et al., 2021). After controlling for national narcissism, national identification was unrelated to climate change conspiracy beliefs, and unrelated or positively related (in one study) to climate science acceptance (Bertin et al., 2021).

Findings on science skepticism help explain why national narcissism predicts lower support for science-backed public policies. To illustrate, Cislak et al. (2023) observed that those higher in national narcissism were less likely to support climate change mitigating policies, such as the Green Deal or governmental subsidies for renewables. After controlling for national narcissism, national identification was positively related to support for such policies. In a similar vein, using the 2016 European Social Survey dataset Kulin et al. (2021) found that nationalist ideology (a combined measure of national identification, sovereignty, protectionism, and attachment) was positively linked to both climate change skepticism and opposition to fossil fuel taxation. This study, however, did not differentiate between various forms of national identity.

Environmental policies can be perceived as imposed on the nation by external pressures demanding actions that benefit not only the local but also the global environment. Such pressure narratives resonate with those high in national narcissism. For example, in Poland national narcissism was linked to support for the development of fossil fuel energy sources (Cislak et al., 2023), subsidizing the coal industry, and cutting a protected forest (Cislak et al., 2018). The effect of national narcissism on support for the two latter policies was mediated by the need to make decisions independently of external influences (Cislak et al., 2018)—see Bonaiuto et al. (1996) for similar effects of nationalism on denial of UK beach pollution in response to EU-imposed standards. After controlling for national narcissism, Cislak et al. (2018) observed that national identification was unrelated to the need for independent environmental decision-making.

National narcissism is also linked to support for political decisions that assert national independence even if they can harm the national environmental heritage or risk citizens' health (e.g., due to air pollution). For example, in 2020 the French president, Emmanuel Macron, encouraged activists to protest against Green Deal reluctance of the Polish government. In response, those high in Polish national narcissism supported taking an image-focused symbolic action (delivering a diplomatic démarche), rather than encouraging the Polish government to reconsider its energy policy (Cislak et al., 2021b). Thus, support for anti-environmental policies can serve as a signal of the nation's status, reflecting resistance to powerful outgroups even at a cost of harm to current and future compatriots. In fact, such harm may be perceived as an acceptable price to pay for enhancing the ingroup image (for similar processes demonstrated in the public health domain see Gronfeldt et al., 2023).

Overall, those high in national narcissism seem more concerned with the nation's image than with the natural environment (Cislak et al., 2021b) or the wellbeing of ingroup members (Gronfeldt et al., 2023). This means that they might be drawn to political greenwashing: promoting the country's image as pro-environmental without actually investing in pro-environmental policies. In fact, when explicitly asked whether a genuine pro-environmental action or a purely image-boosting campaign should be subsided, those high in national narcissism preferred to use public funds in greenwashing campaigns (Cislak et al., 2021b). However, greenwashing campaigns are supported by those high in national narcissism only when these campaigns do not require significant costs (Cislak et al., 2021b).

The studies to date suggest that national narcissism might promote a focus on short-term image benefits over long-term environmental solutions, while national identification might be more conducive to a longer-term perspective. Initial evidence comes from research by Jamróz-Dolińska et al. (2023), who differentiated between constructive patriotism, conventional patriotism, and national glorification (a construct related to national narcissism; Roccas et al., 2008). They found that constructive patriotism was positively related to a future temporal orientation, which translated into greater support for policies that might have immediate costs but carry future benefits, such as many environmental policies. By contrast, national glorification was unrelated to future temporal orientation and even positively related to prioritizing policies with immediate benefits and future costs (the pattern for conventional patriotism was mixed). Findings reported by Cislak et al. (2021b) showing a preference for mostly symbolic, image-enhancing actions among those high in national narcissism suggest a similar short-term focus.

Past research shows that national image concerns are reflected in climate conspiracy beliefs, opposition to pro-environmental agendas, support for anti-environmental policies, and short-term focus on greenwashing rather than long-term pro-environmental actions. These individual attitudes seem to be underlain by needs to oppose powerful outgroups, which may be perceived as taking advantage of the nation, conspiring against it, and imposing costly policies that are seen as benefitting the global community more than local citizens.

Importantly, the effects of national narcissism tend to be different from those observed for conservative or right-wing ideologies often linked to anti-environmentalism (McCright et al., 2014). While those high in national narcissism oppose anti-environmental policies, they are comfortable with taking advantage of environmental narratives to greenwash the country's image—a strategy that does not appeal to conservatives (Cislak et al., 2021b). In other words, while right-wing ideology is linked to rejection of any pro-environmental policies, national narcissism predicts support for low-cost actions that might boost the country's environmental image.

While past research sheds light on the psychological processes shaping the relationships between national identity and environmentalism, there is an important limitation. Most studies were conducted in Europe, and thus the pattern may be dependent on this specific socio-political context. For example, while environmental care is an important part of being a New Zealander (Milfont et al., 2020), the coal industry may be a source of national pride in certain European countries such as Poland (Zuk and Szulecki, 2020). Still, narratives that appeal to the nation's environmental greatness are politically exploited beyond Europe, even in countries with mixed engagement in the implementation of conservation policies. To illustrate, referring to the increased deforestation rates of the Amazon, the former president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, told the former German Chancellor, Angela Merkel: “take that money and use it to reforest Germany, O.K.? You need it way more than we do here” (Simões, 2019). Similarly, former US president, Donald Trump, was accused of greenwashing when he presented himself as both a “champion for fossil fuels” and “the number one environmental president since Teddy Roosevelt” (Hohmann and Alfaro, 2020). Such narratives might serve not only to mobilize political support, but also shape long-term policymaking and, thereby, a countries' environmental performance.

Moreover, past work was focused on attitudinal outcomes, such as conspiracy beliefs or support for pro- vs. anti-environmental policies. As governments might be motivated to implement policies that are supported by the citizens, it may be hypothesized that environmentalism is lower in countries in which the level of national narcissism of the citizens is higher. Also, more work is needed on real-life implementation of the policies which can be observed with objective measures of environmental performance. Thus, we propose to examine the relationships between national narcissism, national identification, and environmentalism at the country level of analysis. We pre-registered a hypothesis proposing that higher country-mean levels of national narcissism predict a lower tendency to prioritize climate change mitigation and lower rates of implementation of pro-environmental policies at the country level.

To test our hypothesis, we relied on publicly available data collected in 2020–2021 as part of the COVID-19 International Collaboration on Social and Moral Psychology (Azevedo et al., 2023). Dataset and pre-registration are available at https://osf.io/zktw9/, and more details regarding the measures (including reliability) are reported in Cichocka et al. (2023). We used country-level means of both national narcissism (NN), measured with three items (i.e., “[My national group] deserves special treatment,” “Not many people seem to fully understand the importance of [my national group],” “I will never be satisfied until [my national group] gets the recognition it deserves”), and national identification (NI), measured with two items (i.e., “I identify as [nationality]” and “Being a [nationality] is an important reflection of who I am”). We relied on data from 56 countries as units of analysis (all samples N > 90; representative samples from 33 countries) used in previous work on country-level effects of national narcissism (Cichocka et al., 2023). According to sensitivity analyses in G*Power, we were able to detect moderate to large effects: r = 0.36 for the sample size of 56, r = 0.45 for 33 (assuming power of 0.80, α = 0.05; two-tailed).

Besides country-level national identity we used two environmentalism indicators at the country level. We used the Environmental Performance Index (EPI)—an objective measure created by environmental experts (Wolf et al., 2018). We relied on the 2022 EPI data to match the national identity data. We used the overall EPI score for each country (reflecting the country's overall score based on 32 performance indicators) as well as three subindexes: Environmental Health (EH), Ecosystem Vitality (EV), and Climate Change (CC). Higher scores indicate better environmental performance. Our second variable was the environment–economy trade-off question from the 2017–2022 World Values Survey, wave 7 (Haerpfer et al., 2022). We used the percentage of those who chose the environmental option as an indicator of prioritizing the environment (PE)—a higher score means more people in the country prioritize protecting the environment over economic growth and creating jobs. Finally, as both country-level environmental outcomes might be dependent on the wealth of the country, we used 2021 GDP per capita (a country's Gross Domestic Product divided by its total population; The World Bank, World Development Indicators, 2021) as a control variable. Table 1 provides more details and summary statistics.

First, we performed correlational analyses with countries as units of analysis. In line with results from individual-level studies, we observed a positive association between country-level national narcissism and national identification (r = 0.75, p < 0.001). Both national narcissism and national identification were negatively associated with the overall EPI and its subindexes (EPI: rNN = −0.67, p < 0.001 and rNI = −0.54, p < 0.001; EH: rNN = −0.61, p < 0.001 and rNI = −0.51, p < 0.001; EV: rNN = −0.54, p < 0.001 and rNI = −0.41, p = 0.002; CC: rNN = −0.60, p < 0.001 and rNI = −0.50, p < 0.001) but not with prioritizing environmental protection over economic growth and jobs (rNN = −0.27, p = 0.130 and rNI = −0.09, p = 0.635).

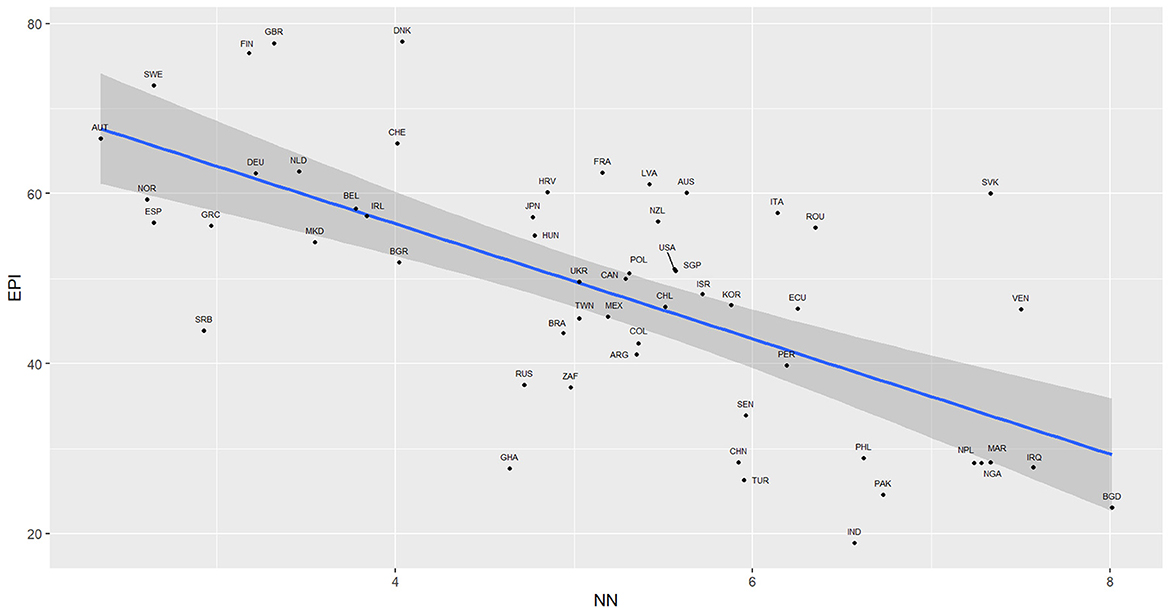

Second, we tested a series of hierarchical regression models to assess the relationships between each of the environmental measures and national narcissism (controlling for national identification). In line with our pre-registered plan, we first estimated a model in which national narcissism and national identification were entered as predictors of EPI, F(2,54) = 21.06, p < 0.001. National narcissism was strongly negatively related to EPI, B = −6.15 (−9.37, −2.93), β = −0.61, p < 0.001, while national identification was unrelated, B = −1.33 (−6.47, 3.82), β = −0.08; p = 0.607. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between national narcissism and EPI. Considering specific subindexes, we found that national narcissism was a strong significant negative predictor of EH, EV, and CC, while national identification was unrelated to any of these subindexes (see detailed analyses in Supplementary material).

Figure 1. The 2022 Environmental Performance Index (EPI) depending on country-level national narcissism (NN). The abbreviations are ISO symbols of the countries.

The model with prioritizing the environment over economic growth included only 32 countries. National narcissism was marginally negatively related to prioritizing the environment, B = −4.36 (−9.26, 0.54), β = −0.61, p = 0.079 (although note that the standardized coefficient was similar in magnitude to the coefficient observed for EPI), while national identification was unrelated to this outcome, B = 4.99 (−3.44, 13.42), β = −0.41; p = 0.236.

We then repeated the main analyses controlling for GDP per capita to test the robustness of the results over and above the countries' wealth. After controlling for GDP, national narcissism was marginally negatively related to EPI, B = −2.96 (−5.94, 0.03), β = −0.29 p = 0.052, and national identification was unrelated to it, B = −2.62 (−6.94, 1.69), β = −0.16; p = 0.228. The effect for GDP per capita was significant and positive, B < 0.001 (0.0002, 0.0004), β = 0.49, p < 0.001. Both national narcissism, B = −3.78 (−8.71, 1.15), β = −0.61, p = 0.127, and national identification, B = 5.31 (−3.05, 13.67), β = 0.41, p = 0.203, were unrelated to prioritizing the environment. The effect for GDP was not significant in this model, B < 0.001 (−0.001, 0.0002), β = 0.25, p = 0.204.

As pre-registered, we then repeated all the analyses including only representative samples, and observed strong effects of national narcissism for EPI and its subindexes, and significant effects for prioritizing environment over economic growth and creating jobs (see detailed analyses in Supplementary material).

This work contributes to the extant literature documenting individual factors that underpin environmental protection or exploitation by highlighting the roles of different forms of national identity. We review the differential effects of national narcissism and identification on environmentalism, and four main mechanisms that help explain why psychological needs for image protection and enhancement typical of national narcissism might translate into lower levels of environmentalism. Crucially, we argue that national narcissism is related to lower environmentalism because pro-environmental efforts are costly, they may be perceived as submissiveness to stronger groups, and because the wellbeing of compatriots is not prioritized by those high in national narcissism. But those high in national narcissism are not against any environment-related actions (as right-wingers are): they support image-enhancing greenwashing campaigns, although only when these campaigns do not incur major costs for the ingroup.

Extending past research that has focused on individual-level associations, we report pre-registered analyses examining country-level associations and find that countries in which the average level of national narcissism of the citizens is higher tend to perform less effectively in the environmental domain. Although some of the effects were marginal or statistically non-significant with the current samples, their sizes tended to be large. National narcissism is not only negatively related to the attitudes of the citizens, but also to more objective measures of environmentalism. Effects for national identification were generally weaker and statistically not significant.

Overall, our review and novel country-level findings further elucidate why past work might not have consistently found links between environmentalism and national identity (Bonaiuto et al., 1996; Feygina et al., 2009; Milfont et al., 2020). We argue that to fully understand the links between national identity and environmentalism, it is important to differentiate national narcissism, which can undermine environmental efforts at both individual and country levels, from non-narcissistic national identification, which might be consistent with promoting pro-environmental goals.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

ACis: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. ACic: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. TM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Science Center Grant 2018/29/B/HS6/02826.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsps.2024.1305150/full#supplementary-material

Abou-Ismail, R., Gronfeldt, B., Konur, T., Cichocka, A., Phillips, J., and Sengupta, N.K. (2023). Double trouble: how sectarian and national narcissism relate differently to collective violence beliefs in Lebanon. Aggress. Behav. 49, 669–678. doi: 10.1002/ab.22104

Anderson, B. R. O. (2016). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Revised Edition. London: Verso.

Azevedo, F., Pavlović, T., Rêgo, G. G., Ay, F. C., Gjoneska, B., Etienne, T. W., et al. (2023). Social and moral psychology of COVID-19 across 69 countries. Sci. Data 10:272. doi: 10.1038/s41597-023-02080-8

Back, M. D., Küfner, A. C. P., Dufner, M., Gerlach, T. M., Rauthmann, J. F., Denissen, J. J. A., et al. (2013). Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: disentangling the bright and dark sides of narcissism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 105, 1013–1037. doi: 10.1037/a0034431

Bertin, P., Nera, K., Hamer, K., Uhl-Haedicke, I., and Delouvée, S. (2021). Stand out of my sunlight: The mediating role of climate change conspiracy beliefs in the relationship between national collective narcissism and acceptance of climate science. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 24, 738–758. doi: 10.1177/1368430221992114

Bonaiuto, M., Breakwell, G. M., and Cano, I. (1996). Identity processes and environmental threat: the effects of nationalism and local identity upon perception of beach pollution. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 6, 157–175. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1298(199608)6:3<157::AID-CASP367>3.0.CO;2-W

Bonikowski, B., and DiMaggio, P. (2016). Varieties of American popular nationalism. Am. Sociol. Rev. 81, 949–980. doi: 10.1177/0003122416663683

Cichocka, A. (2016). Understanding defensive and secure in-group positivity: the role of collective narcissism. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 27, 283–317. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2016.1252530

Cichocka, A., and Cislak, A. (2020). Nationalism as collective narcissism. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 34, 69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.12.013

Cichocka, A., de Zavala, A. G., Marchlewska, M., Bilewicz, M., Jaworska, M., and Olechowski, M. (2018). Personal control decreases narcissistic but increases non-narcissistic in-group positivity. J. Pers. 86, 465–480. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12328

Cichocka, A., Marchlewska, M., Golec de Zavala, A., and Olechowski, M. (2016). ‘They will not control us': ingroup positivity and belief in intergroup conspiracies. Br. J. Psychol. 107, 556–576. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12158

Cichocka, A., Sengupta, N., Cislak, A., Gronfeldt, B., Azevedo, F., Boggio, P. S., et al. (2023). Globalization is associated with lower levels of national narcissism: evidence from 56 countries. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 14, 437–447. doi: 10.1177/19485506221103326

Cislak, A., and Cichocka, A. (2023). National narcissism in politics and public understanding of science. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2, 740–750. doi: 10.1038/s44159-023-00240-6

Cislak, A., Cichocka, A., Wojcik, A. D., and Milfont, T. L. (2021a). Words not deeds: National narcissism, national identification, and support for greenwashing versus genuine proenvironmental campaigns. J. Environ. Psychol. 74:101576. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101576

Cislak, A., Marchlewska, M., Wojcik, A. D., Sliwiński, K., Molenda, Z., Szczepańska, D., et al. (2021b). National narcissism and support for voluntary vaccination policy: the mediating role of vaccination conspiracy beliefs. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 24, 701–719. doi: 10.1177/1368430220959451

Cislak, A., Wójcik, A. D., Borkowska, J., and Milfont, T. L. (2023). Secure and defensive forms of national identity and public support for climate policies. PLoS Clim 2:e0000146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pclm.0000146

Cislak, A., Wojcik, A. D., and Cichocka, A. (2018). Cutting the forest down to save your face: narcissistic national identification predicts support for anti-conservation policies. J. Environ. Psychol. 59, 65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.08.009

Dovidio, J. F., Ikizler, E. G., Kunst, J. R., and Levy, A. (2020). “Common identity and humanity,” in Together Apart: The Psychology of Covid-19, eds J. Jetten, S. D. Reicher, S. A. Haslam, and T. Cruwys (London: Sage Publications Ltd), 142–146.

Dunlap, R. E., and Brulle, R. J. (2015). Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199356102.001.0001

Easterbrook, M., and Vignoles, V. L. (2012). Different groups, different motives: identity motives underlying changes in identification with novel groups. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 38, 1066–1080. doi: 10.1177/0146167212444614

Federico, C. M., Golec De Zavala, A., and Bu, W. (2023). Collective narcissism as a basis for nationalism. Polit. Psychol. 44, 177–196. doi: 10.1111/pops.12833

Feygina, I., Jost, J. T., and Goldsmith, R. E. (2009). System justification, the denial of global warming, and the possibility of “system-sanctioned change.” Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 36, 326–338. doi: 10.1177/0146167209351435

Fielding, K. S., and Hornsey, M. J. (2016). A social identity analysis of climate change and environmental attitudes and behaviors: insights and opportunities. Front. Psychol. 7:121. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00121

Fritsche, I., Jonas, E., Ablasser, C., Beyer, M., Kuban, J., Manger, A.-M., et al. (2013). The power of we: Evidence for group-based control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 49, 19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.07.014

Główczewski, M., Cichocka, A., Wójcik, A. D., and Cislak, A. (2022). “‘Cause we are the champions of the world”. national narcissism and group-enhancing historical narratives. Soc. Psychol. 53, 357–367. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000506

Golec de Zavala, A., Cichocka, A., Eidelson, R., and Jayawickreme, N. (2009). Collective narcissism and its social consequences. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 97, 1074–1096. doi: 10.1037/a0016904

Golec de Zavala, A., Cichocka, A., and Iskra-Golec, I. (2013). Collective narcissism moderates the effect of in-group image threat on intergroup hostility. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 104, 1019–1039. doi: 10.1037/a0032215

Golec de Zavala, A., Dyduch-Hazar, K., and Lantos, D. (2019). Collective narcissism: political consequences of investing self-worth in the ingroup's image. Polit. Psychol. 40, 37–74. doi: 10.1111/pops.12569

Golec De Zavala, A., Federico, C. M., Sedikides, C., Guerra, R., Lantos, D., Mroziński, B., et al. (2020). Low self-esteem predicts out-group derogation via collective narcissism, but this relationship is obscured by in-group satisfaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 119, 741–764. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000260

Gronfeldt, B., Cislak, A., Sternisko, A., Eker, I., and Cichocka, A. (2023). A small price to pay: national narcissism predicts readiness to sacrifice in-group members to defend the in-group's image. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 49, 612–626. doi: 10.1177/01461672221074790

Gundersen, T., Alinejad, D., Branch, T. Y., Duffy, B., Hewlett, K., Holst, C., et al. (2022). A new dark age? Truth, trust, and environmental science. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 47, 5–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-120920-015909

Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J. (Eds.), et al. (2022). World Values Survey: Round Seven - Country-Pooled Datafile Version 5.0. Madrid: JD Systems Institute and WVSA Secretariat. doi: 10.14281/18241.20

Hohmann, J., and Alfaro, M. (2020). The Daily 202: Trump is not ‘the Number One Environmental President since Teddy Roosevelt.' Washington, DC: The Washington Post.

Huddy, L., Del Ponte, A., and Davies, C. (2021). Nationalism, patriotism, and support for the European Union. Polit. Psychol. 42, 995–1017. doi: 10.1111/pops.12731

Jamróz-Dolińska, K., Sekerdej, M., Rupar, M., and Kołeczek, M. (2023). Do good citizens look to the future? The link between national identification and future time perspective and their role in explaining citizens' reactions to conflicts between short-term and long-term national interests. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 91, 01461672231176337. doi: 10.1177/01461672231176337

Kalin, M., and Sambanis, N. (2018). How to think about social identity. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 21, 239–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-042016-024408

Kiral Ucar, G., Gezici-Yalcin, M., Özdemir Planali, G., and Reese, G. (2023). Social identities, climate change denial, and efficacy beliefs as predictors of pro-environmental engagements. J. Environ. Psychol. 91, 102144. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.102144

Kosterman, R., and Feshbach, S. (1989). Toward a measure of patriotic and nationalistic attitudes. Polit. Psychol. 10, 257–274. doi: 10.2307/3791647

Kulin, J., Johansson Sevä, I., and Dunlap, R. E. (2021). Nationalist ideology, rightwing populism, and public views about climate change in Europe. Environ. Polit. 30, 1111–1134. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2021.1898879

Marchlewska, M., Górska, P., Green, R., Szczepańska, D., Rogoza, M., Molenda, Z., et al. (2022). From individual anxiety to collective narcissism? Adult attachment styles and different types of national commitment. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 014616722211390. doi: 10.1177/01461672221139072

Marie, A., and Petersen, M. B. (2022). Political conspiracy theories as tools for mobilization and signaling. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 48:101440. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101440

McCright, A. M., Xiao, C., and Dunlap, R. E. (2014). Political polarization on support for government spending on environmental protection in the USA, 1974–2012. Soc. Sci. Res. 48, 251–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.06.008

Milfont, T. L., Osborne, D., Yogeeswaran, K., and Sibley, C. G. (2020). The role of national identity in collective pro-environmental action. J. Environ. Psychol. 72:101522. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101522

Postmes, T., Rabinovich, A., Morton, T., and van Zomeren, M. (2013). “Toward sustainable social identities: including our collective future into the self-concept,” in Psychology and the Environment, ed. H. C. M. van Trijp (London: Psychology Press), 185–202.

Ray, J. J. (1980). The psychology of environmental concern—some Australian data. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1, 161–163. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(80)90034-3

Roccas, S., Sagiv, L., Schwartz, S., Halevy, N., and Eidelson, R. (2008). Toward a unifying model of identification with groups: integrating theoretical perspectives. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 12, 280–306. doi: 10.1177/1088868308319225

Schatz, R. T., Staub, E., and Lavine, H. (1999). On the varieties of national attachment: blind versus constructive patriotism. Polit. Psychol. 20, 151–174. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00140

Schlicht-Schmälzle, R., Chykina, V., and Schmälzle, R. (2018). An attitude network analysis of post-national citizenship identities. PLoS ONE 13:e0208241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208241

Simões, M. (2019). Brazil's Bolsonaro on the Environment, in His Own Words. New York, NY: The New York Times.

Sternisko, A., Cichocka, A., Cislak, A., and Van Bavel, J. J. (2023). National narcissism predicts the belief in and the dissemination of conspiracy theories during the covid-19 pandemic: evidence from 56 countries. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 49, 48–65. doi: 10.1177/01461672211054947

Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., and Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1, 149–178. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420010202

The World Bank World Development Indicators. (2021). GDP Per Capita. Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD

Van Lange, P. A. M., Joireman, J., and Milinski, M. (2018). Climate change: what psychology can offer in terms of insights and solutions. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 27, 269–274. doi: 10.1177/0963721417753945

Van Zomeren, M. (2013). Four core social-psychological motivations to undertake collective action. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 7, 378–388. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12031

Wolf, M. J., Emerson, J. W., Esty, D. C., Levy, M. A., de Sherbinin, A., and Wendling, Z. A. (2018). 2022 Environmental Performance Index. New Haven, CT: Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy.

Keywords: collective narcissism, national identity, conservation, environmental policy, environmental performance

Citation: Cislak A, Wojcik AD, Cichocka A and Milfont TL (2024) National identity and environmentalism: why national narcissism might undermine pro-environmental efforts. Front. Soc. Psychol. 2:1305150. doi: 10.3389/frsps.2024.1305150

Received: 30 September 2023; Accepted: 19 January 2024;

Published: 08 February 2024.

Edited by:

Adam M. Croom, Case Western Reserve University, United StatesReviewed by:

Sharon Coen, University of Salford, United KingdomCopyright © 2024 Cislak, Wojcik, Cichocka and Milfont. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aleksandra Cislak, YWNpc2xha0Bzd3BzLmVkdS5wbA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.