- 1Urban and Regional Planning Department, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

- 2Urban and Regional Planning Department, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

The Global North has dominated the planning theories for decades to resolve planning problems globally. These Northern theories were not feasible for most problems in the Global South, as the continued use of Northern theories maintains the inequalities of disjointed and divided cities caused by colonialism. However, as this approach is inappropriate and inadequate, planning theories require decolonization from the continued focus on the Global North in order to reflect the realities of the South. This paper contributes to the scholarship of decolonization in planning by investigating how planning academics and professionals in South Africa view the progress made in the decolonization of planning theories for inclusion and equity.

1 Introduction

Most planning theories originate from the Global North, where for decades, they have dominated attempts to identify, understand, and resolve urban and regional planning problems. Fishman (2015, p. 33) stated that from 1890 to 1930, three Global North planning theorists, “Ebenezer Howard, Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier,” formulated some of the first planning theories directed at the Global North’s planning problems. Over the years, more Global North planning theorists developed theories on the same Global North outlook of planning (Taylor, 1998). This perspective of planning problems does not necessarily overlook the issues of the Global South but views them through a Northern lens. In many places in the Global South, the continued use of Northern theories maintains the inequalities and divided cities produced by colonialism. This approach of utilizing Global North planning theories has proven to be inappropriate and inadequate. According to Harrison et al. (2008) and Silva et al. (2019), European and American planning theories were viewed as Apartheid systems of planning that contributed to fragmented and divided cities in the Global South, emphasising the significance of decolonizing planning theories. The late Vanessa Watson, in her paper “Shifting Approaches to Planning Theory: Global North and South” (2016), highlighted the need for planning theories to be more Global South-orientated for Southern countries. Her paper also shows that these Global South planning ideas are still in the early stages of development. Therefore, this paper asks the following question: If decolonizing the planning theories would contribute to more inclusive and equitable theories in the South African context?

This paper seeks to investigate whether Southern planning theories can be more inclusive and equitable using the lens of decolonization. Decolonization is a critical and transformative encounter with direct forms of colonial power and indirect influences of coloniality. Although it began earlier, much theorizing began along with the struggle for independence in the mid-1900s. Although there are many aspects to the decolonization theory, this paper focuses on knowledge production through a decolonization paradigm. A paradigm is interpreted as a worldview or framework for research or practice (Taylor and Medina, 2011).

The paper adopted an exploratory qualitative research methodology to sample, source, and collect data from planning academics and professionals in South Africa to determine if there is a need for decolonization of planning theories to address problems in the Global South. The primary data that had been collected were then analysed through the content analysis method to categorise the results into two categories, with planning academics and professionals reporting the results.

The paper is divided into four major sections: reflection on decolonizing of planning theory, methodology, report on the findings, and the paper concludes with our views on decolonization, equity and inclusion.

2 Reflection on decolonizing of planning theories

Although planning theory is vague with numerous nuances (Allmendinger, 2002), Rydin (2021, p. 9) defined theory as a “set of ideas that fit together coherently and make general statements about the world or a part of it fundamental assumptions about how the world is as well as value judgements about how it should be.” Normative planning theory is concerned not only with what is but also with how the world should be (Rydin, 2021). Planning theory is thus used to identify and understand the origin or cause of problems to find solutions (Abukhater, 2009; Brooks, 2019; Donaghy and Hopkins, 2006; Gunder et al., 2018). Different interpretations of dilemmas seen through different paradigms will lead to different proposals to solve them.

Most planning theories originated from the Global North and disregarded Global South systems (Sihlongonyane, 2018). Nel and Denoon-Stevens (2024) pointed out that Global South scholars indicated that when Global North theories are utilised in the Global South, it is often inappropriate due to the different settings in which they had been developed. Therefore, viewing the inappropriate of Global North theories in the Global South through the utopian perspective is an example.

Utopian planning theory is a theoretical framework that aims to provide an idea or method for establishing an ideal city (Hoch, 2016). As a result, Global North utopian theorists set out to design the perfect city with limitless potential, for example, to alleviate contemporary social instabilities in a spatial arrangement that would reunite society in perfect spatial harmony. The following theorists, Ebenezer Howard, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Le Corbusier, according to Fishman (2015, p. 27), are utopian. In 1898, Ebenezer Howard established the Garden City theory. The heart of this is to plan for the perfect social city with interconnected urban and rural areas that have a unique attraction force for densification (Reblando, 2014; Daci, 2022). The Garden City theory is a well-known Global North planning theory that inspired numerous Northern cities, although they ignored communalism and other social components (Ben-Jospeh, 2005; Brockett, 1996).

As most planning theorists have been from the Global North, only a few alternative planning theories originated from the South. According to Harrison et al. (2008, p. 214), Global North planning concepts (e.g., what is a good home) have “diffused” globally. Cilliers (2020) confirmed that the planning ideas of the Global North countries dominate African planning. Many such concepts reject indigenous solutions and are unrealistic in Africa. Huchzermeyer (2011) called for the acceptance of local realities, such as informal settlements, while Nel and Denoon-Stevens (2024) pleaded for appropriate forms of spatial governance. For the planning theories to be more inclusive and equitable, they must be decolonized from the North to more Southern-oriented theories.

There are several ways of decolonizing from the North to the South. First, decolonization is the universal transition from Western global-scale domination to self-rule and independence (Dirette, 2018; Gordon, 2014; Higgs, 2012). Second, there must be a delinking from the colonial way of thinking (paradigm) to the decolonized (Global South) through increased Southern thinking and scholarship that contributes to diverse knowledge systems (Chambers and Buzinde, 2015). Third, this transition should address the long history of injustices experienced. Sadly, as Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2018) suggested, some countries do not want to accept this shift of power and knowledge with redress.

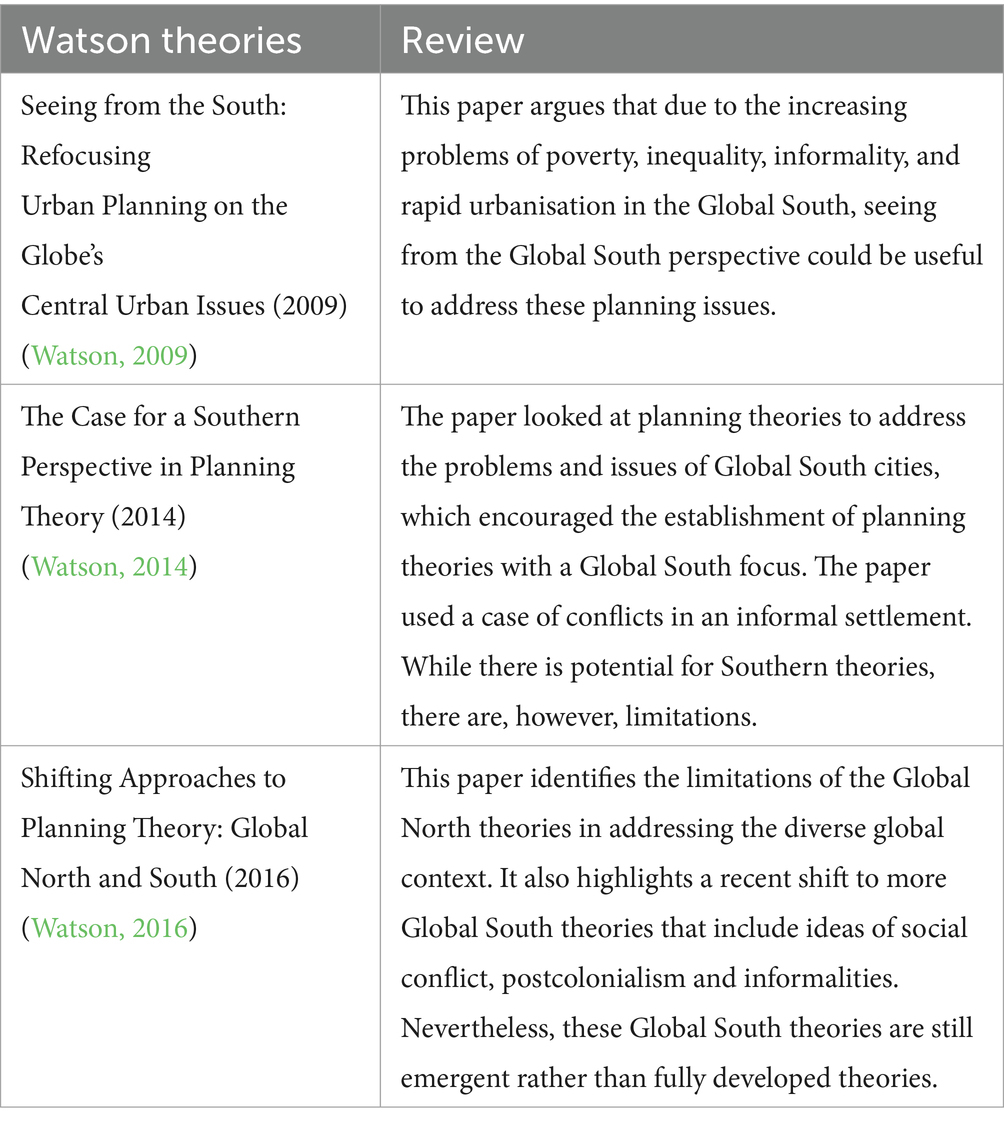

Nonetheless, there is a growing literature on South African planning theory. A leading theorist is the late Vanessa Watson, who called for “seeing from the South” (2009), noting “the case for a southern perspective” (2014) and identified “shifting approaches to planning theory” (2016) as reviewed in the following Table 1.

Other theorists are Yiftachel (2006), Phil Harrison and Alison Todes (Harrison et al., 2008; Harrison and Todes, 2015) and Ivan Turok (Seeliger and Turok, 2013; Turok and Scheba, 2019).

3 Methodology

A qualitative research design that focuses on the why rather than the what was adopted (Brodsky et al., 2016; Taherdoost, 2016). Exploratory research is a type of quantitative research that looks at research problems that have not been thoroughly studied and can be utilised to get new perspectives (George, 2021). Thus, for this paper, exploratory research was the best methodology for investigating undiscovered research on decolonizing planning theory. The qualitative exploratory research methodology has been adopted with two units of analysis as the planning academics and professionals, and Table 2 illustrates the different methods that have been selected for this paper methodology:

The data from both the survey and the interviews were analysed using content analysis based on the same question posed to each group (Bhattacherjee, 2012; Stemler, 2015). Content analysis analyses textual data to contribute to new knowledge. Stemler (2015) stated that content analysis creates categories and then reports on the results in narrative text. Therefore, the analysis categorised the data into two categories: academic and professional planners’ results. The justification for using two categories to analyse and depict the data is that all planning academics support the decolonization of planning ideas, whereas some planning professionals are less supportive. This reflects (Fainstein, 2012) apposite comment that planning practitioners generally ignore planning theory. Denoon-Stevens et al. (2020) indicate that the respondents to the survey conducted as part of the SAPER project – which also used self-selection from the South African Council for Planners database – had a low opinion of planning theory.

4 Planning academics and professionals reflecting on decolonizing the planning theories

Both groups (academics and professional planners) are classified as professional planners. As such, the results of this paper have been categorised into planning academics and professionals to present their results on decolonising the planning theories separately.

4.1 Planning academics

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with all nine planning academics to obtain their perspective on decolonizing the planning theories. They all agreed that planning theories should be decolonized to reflect the Global South better. Four academics explained that new planning theories (ideas) are based on a pre-existing Global North paradigm. One academic stated the following:

We still need the mainstream planning purists that were developed in the West, because they still apply and offer value. We also need to bring the indigenous Global South theories so that they add more value, and we create more robust planning theories.

Other academics emphasised the importance of including more indigenous knowledge in planning theories, improving the participation of communities, and understanding the areas that require planning. One academic said:

The planning approaches derived solely from Western contexts may not effectively address Global South countries’ complex challenges, such as rapid urbanisation, informal settlements, environmental degradation, etc.

Most Global South countries do not have vast resources, and infrastructure services are therefore also limited, which contributes to urban sprawl and informal settlements with few basic services. Indigenous knowledge must stay relevant in Southern planning theories as the planning situations could change over time.

One academic commented that a colonial perspective had shaped most planning theories and often neglected the diverse realities and needs of Global South countries. Another comment was that the older generation of academics and scholars who were educated in the Global North believed in those planning theories, while younger academics and scholars were mostly educated in the Global South and were more pro-decolonizing. Future planning theories in the Global South will be more South-focused. Watson’s (2016) groundbreaking work was recognised, as stated by an academic:

There are a lot of excellent theoretical perspectives that have been originating from the Global South.

This academic supported the decolonizing of planning theories yet noted a challenge faced with drafting Southern theories. A theory must be tested, which is difficult in a context where most Global South scholars have limited funding to conduct the necessary research.

4.2 Planning professionals

The survey findings reported that 60% of the planners supported decolonizing planning theories, 30% disagreed, and 10% were uncertain, as illustrated in Figure 1.

It was identified that planners generally disregard planning theories, but 60% of planners supported the decolonization of planning theory in the open-ended survey. Five of the planners voiced in their responses the importance of Global South planning theories, and one stated.

that Global South planning theories must address issues that are relevant in developing countries, such as rapid urbanisation, informal settlements, and sustainable development in resource-constrained environments.

As South Africa is a developing country with rapid urbanisation and informal settlements, planning theories need to be Global South-oriented to address these challenges accurately. A planner explained further that as South Africans living in the Global South, our challenges are different from those of the Global North, and it is important to decolonize the planning theories from the classic (Global North) planning theories. Global South scholars such as Harrison, Todes, Watson and Huchzermeyer confirmed that Global North planning theories are unrealistic in the Global South. Then, one of the planners said that.

African problems can only be solved through African ways. What may be a problem in America may not be a problem in South Africa.

Of the 60% of planners who support decolonizing planning theories, eight of the planners stated that it is important to have Global South planning theories to resolve local challenges.

Three of the planners who supported decolonization showed interest in learning more about Global South theories if this would assist them in finding solutions to their day-to-day challenges. One of the three planners stated that decolonizing the planning theories would equip future development practitioners to serve African cities, towns, and traditional settlements better. This acknowledges that planners are interested in Global South planning theories and want to learn more. With this in mind, a planner said that Global South planners.

Should deconstruct much of the current theories and embrace local knowledge and systems.

This statement is closely linked to the aim of this paper to decolonize the planning theories, which is that the Global South planners and planning scholars must review the current planning theories and see if they can be altered to be more Global South-oriented. It was then mentioned that young scholars must be encouraged to develop Southern theories for their Global South countries such as South Africa. The literature on these Global South theories is limited, as demonstrated by the reflection on the decolonising of planning theories section.

Four of the planners stated they are absolutely in agreement that planning theories must be decolonized. However, they also pointed out in their responses that planners must not throw away the Global North planning theories. One suggested that Global South planners who develop Global South theories can learn from the history of the Global North theories. All history has lessons to be learned, good or bad, and the Global South planners must be open-minded. It is important to note that the four planners are fully in agreement to decolonize the planning theories but mentioned that the Global South theorists can learn from Global North theories.

Ten percent of planners stated that they are neither against nor for decolonizing planning theories. One of these planners stated that planning needs to be broadened, not narrowed. Thus, African planning theories must be introduced, but Global North theories should not be excluded. This notion had been the core of the planner that responded with uncertainty. According to another planner, Global South planning theories should be embraced, but not at the expense of Northern planning theories. Another uncertainty was that not all Global South countries are the same; thus, not all Global South planning theories will be equal. The uncertain responses still identified slight support for decolonizing the planning theories but not fully excluding the Global North planning theories.

As Figure 1 demonstrates, 30% of the planners disagreed with decolonizing planning theories. Of these, only one planner is against the concept of decolonization, stated.

Decolonization is a buzzword that might be popular for a decade or so.

This planner then voiced their perspective on decolonizing the planning theory as.

Western cities are models of planning craftsmanship and skill – not to learn from this is madness.

It was important to identify that this planner was the only one that was against decolonization in general and to decolonize planning theories. The other planners support the concept of decolonization in general, but they disagree that planning theories must be decolonized. One planner believes that decolonization is a political approach and stated the following:

Decolonization has no reason to be entertained in the planning system, as that is the reason why we have the devised cities we have today, which are caused by political interference.

As decolonization was defined as the universal transition from Global North domination to independence, it also delinked the colonial way of thinking to a more Southern one. To decolonize the planning theories, the planners must also focus their thinking on more home-grown solutions for the present planning challenges. One planner explained that planners must play an important role in developing, assessing, and implementing theories that are sound and improve people’s livelihoods, which may imply that some Global North planning theories are applicable and should not be discarded in favour of less developed and possibly less appropriate decolonized theory. Two of the planners also supported the idea that Global North planning theories are applicable and should not be discarded.

Regarding the applicability of Global North planning theories, the planner then expressed their belief that Global South planning theories do not apply to cities built with colonised ideas and principles, implying that Global South planning theories do not exist. Planners would have this perspective, as Watson (2009) exemplified, that there are African countries still utilizing Global North planning theories and laws and that some Global South post-colonial states implement colonial planning theories more rigid than the previous colonial authorities. Then, two of the planners claimed that one could only learn from success, meaning that the Global North theories are successful and that focusing solely on decolonization will result in more important possibilities being overlooked. These planners strongly believed that only the Northern theories are successful and applicable to planning challenges globally.

5 Conclusion

Global North dominated the planning theories and utilised these planning theories in Global South countries, which proved to be inappropriate and inadequate for addressing Southern challenges. This raised the question of whether decolonizing the planning theories would contribute to inclusion and equity in planning theories for the Global South. The results identified that all the planning academics and 60% of the planning professionals fully support decolonizing the planning theories. Not all of the participants that contributed to this study supported decolonizing planning theories, with 10% uncertain and 30% disagreeing.

However, the majority support decolonizing planning theories. Global South planning theories are critical to meeting the challenges of Southern countries, as Global North theories may not be applicable. Furthermore, there is a need for more indigenous knowledge to be incorporated into the decolonization process, as African problems can be solved through African ways. Some academics indicated that older academics schooled in Northern planning theories might stick to them, but younger planners may embrace Global South theories. Some of the planners also mentioned their interest in learning more about Global South theories. The need for a relevant planning theory that reflects the realities of the Global South is gaining ground. The work of past scholars, such as Vanessa Watson, has played an important role in this process.

Some of the planning professionals voiced their uncertainty or disagreement about decolonizing the planning theories as they believe that Global North planning theories are applicable and should not be discarded. While colonialism created infrastructure and brought some benefits to the South, it also brought segregation, disruption of traditional lifestyles and disparaging of indigenous knowledge. Northern planning theories may have contributed to these ills but were unable to solve the challenges they created. Home-grown solutions are therefore needed.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of the Free State’s (UFS) General/Human Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. VN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abukhater, A. B. E.-D. (2009). Rethinking planning theory and practice: a glimmer of light for prospects of integrated planning to combat complex urban realities. Theor. Emp. Res. Urban Manage. 4, 64–79. doi: 10.2307/24872421

Adeoye-Olatunde, O. A., and Olenik, N. L. (2021). Research and scholarly methods: semi-structured interviews. J. Am. College Clin. Pharm. 4, 1358–1367. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1441

Allmendinger, P. (2002). Towards a post-positivist typology of planning theory. Plan. Theory 1, 77–99. doi: 10.1177/147309520200100105

Ben-Jospeh, E. (2005). The code of the city: Standards and the hidden language of place-making. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices. 2nd Edn. Tampa, FL: Digital Commons @ University of South Florida.

Brockett, L. (1996). The history of planning south African new towns: political influences and social principles adopted. New Contree 40, 20–179. doi: 10.4102/nc.v40i0.504

Brodsky, A. E., Buckingham, S. L., Scheibler, J. E., and Mannarini, T. (2016). “Introduction to qualitative approaches” in Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. eds. L. A. Jason and D. S. Glenwick (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 13–22.

Chambers, D., and Buzinde, C. (2015). Tourism and decolonisation: locating research and self. Ann. Tour. Res. 51, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2014.12.002

Cilliers, E. J. (2020). Reflecting on global south planning and planning literature. Dev. South. Afr. 37, 105–129. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2019.1637717

Crouch, M., and McKenzie, H. (2006). The logic of small samples in interview-based qualitative research. Soc. Sci. Inf. 45, 483–499. doi: 10.1177/0539018406069584

Daci, E. (2022). Lessons from the garden city movement: Making a case to regionalize city of Toronto’s tower renewal program. London: York University.

Denoon-Stevens, S. P., Andres, L., Jones, P., Melgaço, L., Massey, R., and Nel, V. (2020). Theory versus practice in planning education: the view from South Africa. Plann. Prac. Res. 37, 509–525. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2020.1735158

Dirette, D. P. (2018). Decolonialism in the profession: reflections from WFOT. Open J. Occup. Ther. 6:1565. doi: 10.15453/2168-6408.1565

Donaghy, K. P., and Hopkins, L. D. (2006). Coherentist theories of planning are possible and useful. Plan. Theory 5, 173–202. doi: 10.1177/1473095206064974

Fishman, R. (2015). “Urban utopias in the twentieth century” in Readings in planning theory: Fainstein/readings in planning theory. eds. S. S. Fainstein and J. DeFilippis (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons), 23–50.

George, T. (2021). Exploratory research | definition, guise, & examples. Available at: https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/exploratory-research/ (Accessed September 16, 2024).

Gordon, L. R. (2014). Disciplinary decadence and the decolonisation of knowledge. Africa Dev. 39, 81–92.

Guest, G., Namey, E. E., and Mitchell, M. L. (2013). Collecting qualitative data: A field manual for applied research. London: Sage.

Gunder, M., Madanipour, A., and Watson, V. (2018). “Planning theory” in The Routledge handbook of planning theory. eds. M. Gunder, A. Madanipour, and V. Watson (London: Routledge), 1–12.

Harrison, P., and Todes, A. (2015). Spatial transformations in a “loosening state”: South Africa in a comparative perspective. Geoforum 61, 148–162. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.03.003

Harrison, P., Todes, A., and Watson, V. (2008). Planning and transformation. Learning from the post-apartheid experience. The RTPI library series. London: CRC Press.

Higgs, P. (2012). African philosophy and the decolonisation of education in Africa: some critical reflections. Educ. Philos. Theory 44, 37–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-5812.2011.00794.x

Hoch, C. (2016). Utopia, scenario and plan: a pragmatic integration. Plan. Theory 15, 6–22. doi: 10.1177/1473095213518641

Huchzermeyer, M. (2011). Cities with ‘slums’: From informal settlement eradication to a right to the city in Africa. Cape Town: UCT Press.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. (2018). The dynamics of epistemological decolonisation in the 21st century: towards epistemic freedom. Strat. Rev. Southern Africa 40, 16–45. doi: 10.35293/srsa.v40i1.268

Nel, V., and Denoon-Stevens, S. P. (2024). Land-use management to support sustainable settlements in South Africa. London: Routledge.

Reblando, J. (2014). Farm security administration photographs of greenbelt towns: selling utopia during the great depression. Utop. Stud. 25, 52–86. doi: 10.5325/utopianstudies.25.1.0052

Seeliger, L., and Turok, I. (2013). Towards sustainable cities: extending resilience with insights from vulnerability and transition theory. Sustain. For. 5, 2108–2128. doi: 10.3390/su5052108

Sihlongonyane, M. F. (2018). The generation of competencies and standards for planning in South Africa: differing views. Town Reg. Planning 72, 70–83.

Silva, C., Lewis, M., and Nel, V. (2019). “Setting standards and competencies for planners” in Routledge handbook of urban planning in Africa. ed. C. N. Silva (London: Routledge), 162–176.

Stemler, S. E. (2015). “Content analysis” in Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences: An interdisciplinary, searchable, and linkable resource. eds. R. Scott and S. Kosslyn (Amsterdam: Wiley), 1–14.

Taherdoost, H. (2016). Sampling methods in research methodology: how to choose a sampling technique for research. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manage. 5, 18–27. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3205035

Taherdoost, H. (2021). Data collection methods and tools for research; a step-by-step guide to choose data collection technique for academic and business research projects. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manage. 10, 10–38.

Taylor, P. C., and Medina, N. D. (2011). Educational research paradigms: from positivism to pluralism. College Res. J. 1, 9–23.

Turok, I., and Scheba, A. (2019). ‘Right to the city’ and the new urban agenda: learning from the right to housing. Territ., Politics, Gov. 7, 494–510. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2018.1499549

Watson, V. (2009). Seeing from the south: refocusing urban planning on the Globe’s central urban issues. Urban Stud. 46, 2259–2275. doi: 10.1177/0042098009342598

Watson, V. (2014). The case for a southern perspective in planning theory. Int. J. E-Plann. Res. 3, 23–37. doi: 10.4018/ijepr.2014010103

Watson, V. (2016). Shifting approaches to planning theory: global north and south. Urban Plan. 1, 32–41. doi: 10.17645/up.v1i4.727

Wei, C., Yan, L., Li, J., Su, X., Lippman, S., and Yan, H. (2018). Which user errors matter during HIV self-testing? A qualitative participant observation study of men who have sex with men (MSM) in China. BMC Public Health 18, 1108–1105. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6007-3

Keywords: planning theory, decolonization, inclusion, equity, Global South

Citation: Buttner D, Nel V and Mphambukeli TN (2025) Applying a decolonization paradigm to planning theory for inclusion and equity. Front. Sustain. Cities. 6:1475883. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2024.1475883

Edited by:

Prudence Khumalo, University of South Africa, South AfricaReviewed by:

Joseph Kwaku Kidido, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, GhanaCheonjae Lee, Kangwon National University, Republic of Korea

Copyright © 2025 Buttner, Nel and Mphambukeli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dane Buttner, ZGFuZWJ1dHRuZXJAeW1haWwuY29t

Dane Buttner

Dane Buttner Verna Nel

Verna Nel Thulisile Ncamsile Mphambukeli

Thulisile Ncamsile Mphambukeli