- 1Department of Art and Design, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, United States

- 2Architectural Engineering Department, United Arab Emirates University, Al-Ain, United Arab Emirates

The country of Jordan is committed to sustainable development goals and public well-being but faces challenges such as high rates of poverty and disaffection, exacerbated by the influx of refugees. This study aimed to evaluate housing-related happiness factors and provide recommendations for integrating these metrics into sustainable housing evaluations. We conducted qualitative interviews and used interpretative phenomenological analysis, grounded in an interpretivist paradigm, to understand Jordanian residents’ perspectives on their housing conditions. The research design emphasized capturing the subjective experiences of residents and the meanings they assign to their housing environments. Our findings indicate that social integration and community bonds are crucial for housing happiness, emphasizing cultural continuity, place attachment, social belonging, and dignity. These insights highlight the importance of considering social and psychological outcomes in sustainable housing initiatives, often overshadowed by economic and ecological metrics. We propose recommendations to enhance sustainable housing policies by focusing on social sustainability, contributing to the growing trend of incorporating social and psychological outcomes in green building evaluations. This study offers a framework for future sustainable housing projects to ensure they address the social and psychological needs of residents, thereby improving overall community well-being.

1 Introduction

The influential Brundtland Report of 1987 described sustainable development as a “triple-bottom-line” approach aims to balance economic, environmental, and social objectives. While this balancing of concerns has continued to be rhetorically influential, most actual sustainability research and practice has focused on the economic and environmental aspects, with much less attention to social issues. This is a serious elision since population demographics and broad socioeconomic relationships are closely intertwined with the activities of production and consumption that must be adjusted to meet sustainable development goals (Sachs et al., 2022; United Nations Jordan [UN Jordan], 2022). This oversight gains particular importance in understanding the intricate relationship between socioeconomic factors and individuals’ environmental perceptions and behaviors, which is essential for promoting sustainable living practices (Clayton and Myers, 2015; Steg and Vlek, 2009). Such interdependence highlights the need for a holistic approach that integrates the insights from psychological research with the triple-bottom-line approach to sustainable development (Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989). Various forms of social inequality, poverty, and conflict continue to persist throughout the world, including in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region where the current study took place (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2019). These social metrics are closely linked to the tendency to fall behind on all aspects of the sustainable development agenda (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia [UN ESCWA], 2020).

Unfortunately, recent economic growth in the MENA region has often occurred in conjunction with social destabilization, rising inequality, and unsustainable building practices (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs [UN DESA], 2020). While some financial outlooks in the region appear impressive, recent reports, express significant reservations about the ongoing prospects for continued growth and prosperity, even in near-future terms (Arezki et al., 2019; United Nations Jordan [UN Jordan], 2022). This concern is primarily due to the region’s long-term economic underperformance compared to global standards, which is significantly attributed to a lack of transparency and inefficient data systems (Arezki et al., 2019). This is particularly true for MENA countries that lack oil reserves, some of which are accumulating significant fiscal deficits as they import energy to meet the needs of a burgeoning middle-class population (Arezki et al., 2019; United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], 2017). These oil-importing nations are already beginning to see the effects of unsustainable growth, evident in rising rates of unemployment among young people, increasing extremes of poverty, and—as noted in other sources—ecological degradation (Arezki et al., 2019; Elmassah and Hassanein, 2023; Mansour, 2012).

The MENA region has one of the highest income disparities in the world, with the richest 1% controlling twice as much wealth as the poorest 50% of the population (Chancel and Piketty, 2021; Moshrif, 2020). Such wealth disparities can have a tremendous impact on housing, which is one of the essential socioeconomic circumstances for human well-being and quality of life (Rolfe et al., 2020; World Bank, 2018). Growing rates of urbanization in the MENA region and across the world have exacerbated housing affordability issues especially among marginalized groups and low-income earners (World Bank, 2020a). Reflecting on its strategic advancements in sustainable urban development, Jordan has endorsed its first-ever National Urban Policy, developed in partnership with United Nations Habitat, to promote environmentally sustainable, economically prosperous, and socially inclusive urban growth (UN-Habitat, 2023). Building on Jordan’s strategic advancements in sustainable urban development, the authors initiated a research trajectory to investigate the social sustainability and well-being dimensions of affordable housing in the Jordanian context. The research problem addressed in this paper is integrating social and psychological outcomes into sustainable housing development and policies in Jordan. Despite Jordan’s commitment to sustainable development goals, the country faces significant challenges in addressing poverty, disaffection, and the influx of refugees, which impact residents’ happiness and well-being.

Recognizing the challenges in sustainable housing, the first author, in collaboration with Dr. Adel Al-Assaf, an expert in Jordan’s green built environment, initiated a research trajectory with a ‘Pilot Study’ that explored the foundational dimensions of sustainable housing and social sustainability. The preliminary findings from this pilot highlighted the potential benefits of sustainable housing in terms of social equity, health, and well-being (Ebbini and Al-Assaf, 2018). Building on these insights and the limitations identified, the first author and Dr. Al-Assaf then conducted ‘Study 1’, which further investigated key indicators for social well-being, subjective well-being, and social sustainability performance of sustainable affordable housing in the Jordanian context (Ebbini and Al-Assaf, in preparation).

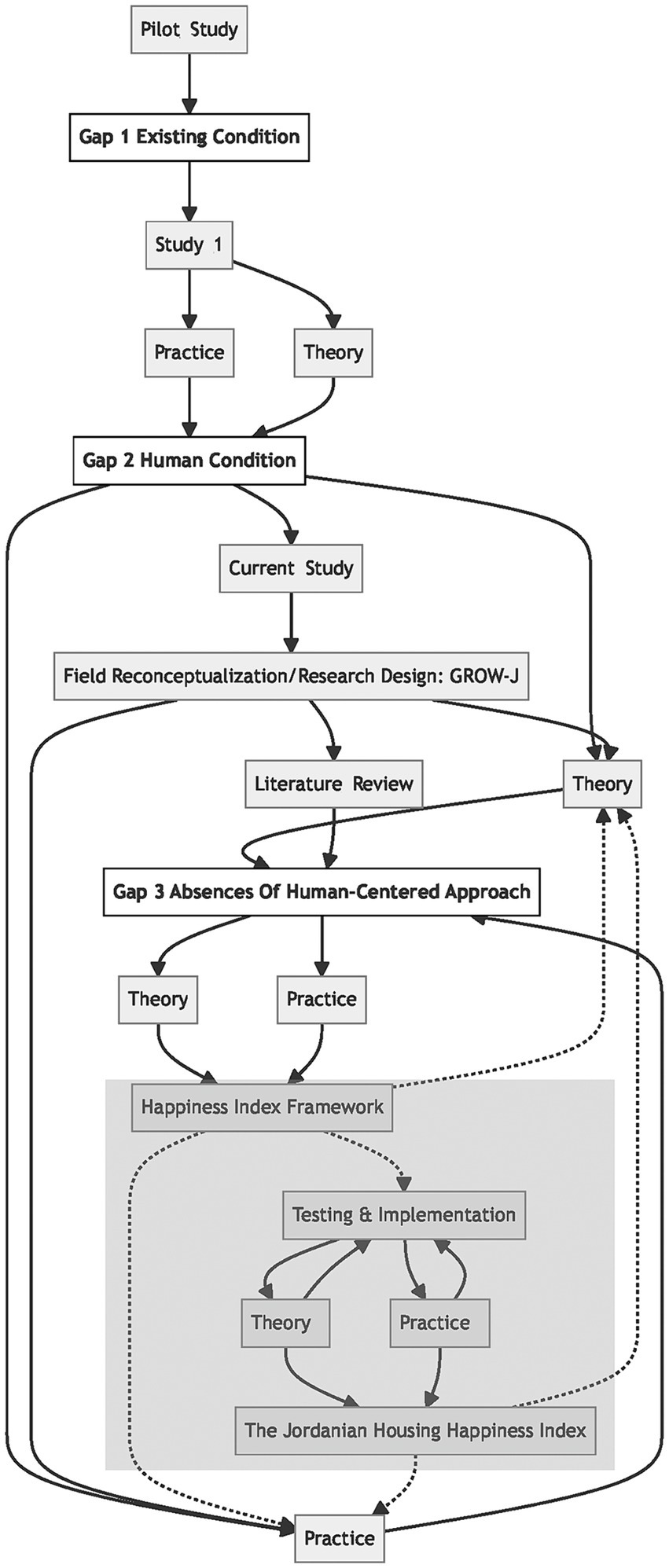

Building upon a foundational pilot study and ‘Study 1’, which explored the social sustainability and well-being dimensions of sustainable housing in Jordan, this current study extends our research trajectory. This study evaluates housing-related happiness factors among Jordanian residents living in sustainable housing developments. Through qualitative interviews and interpretative phenomenological analysis, we explored how residents perceive their housing conditions and how these perceptions influence their well-being, sense of place, and social integration. It seeks to deepen our understanding of how sustainable housing influences housing happiness, sense of place, and subjective well-being, using the same participant list and locations as the previous studies. Focusing on Jordan—a context underrepresented in existing literature—this work reveals the complex impact of sustainable housing on psychological well-being. Through integrating urban planning and psychology, we highlight the critical role of housing quality in achieving environmental sustainability and enhancing social cohesion. As part of our broader research trajectory to develop a Housing Happiness Index for Jordan, we present a roadmap of our approach in Figure 1, which illustrates the progression of our studies and the integration of findings across different phases. This paper aims to fill the gap by comprehensively evaluating the social and psychological outcomes of sustainable housing initiatives in Jordan. By focusing on residents’ subjective experiences and well-being, this study contributes to the growing body of literature advocating for the inclusion of social sustainability in green building evaluations.

Figure 1. Roadmap of the overall research trajectory to develop a housing happiness index for Jordan; the current study focuses on evaluating “Gap 2” related to experiences and perceived needs of residents.

This situation contributes to objective material hardships, and at the same time, it can have a profound impact on subjective well-being (SWB), a psychological state that is associated with social integration and pro-social behaviors, and therefore with the success of economic and environmental sustainability. The current article draws from Diener’s (1984, 2009) understanding of SWB as an internal state of satisfaction with life and with one’s conditions. When viewing affordable housing development from this perspective, researchers must be cognizant of factors that extend beyond objective material conditions, such as the perception of cultural continuity, place attachment, social belonging, and feelings of dignity. Given this broader context, our study examines the intricate relationships between living environments and psychological well-being, conditions to influence individuals’ sense of place and overall happiness. This inquiry not only adheres to but also expands the scope of inquiry within the field, addressing critical aspects of human-environment interactions.

Like many countries, Jordan has seen profound achievements in economic development and in some environmental metrics in recent years, but the population’s average standards of living, happiness, and SWB have actually declined (Sachs et al., 2022; United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2019). The most recent World Happiness Report lists Jordan as the third-unhappiest country in the MENA region (Helliwell et al., 2024). Many of the country’s citizens have difficulty obtaining even the most basic essentials of life (World Bank, 2020a), with an estimated 17% of the urban population has been reported as living in “slums” (World Bank, 2020b). This is a striking outcome in a country that has made great strides in meeting other economic and environmental sustainable development targets. Despite these advancements, the stark contrast between Jordan’s developmental progress and the declining well-being of its citizens highlights the complexity of the challenges at hand. Our study aligns with and critically examines the frameworks concerning built environments and well-being, highlighting the intricate relationship between physical spaces and psychological health. By focusing on Jordan, we provide insights into how sociocultural and housing factors intertwine to affect place attachment and individual happiness, potentially expanding and challenging current environmental psychology theories. Such an examination enriches the discourse, encouraging a reevaluation of the influence of environmental and policy conditions on psychological well-being in varied settings. This context sets the stage for a deeper exploration of sustainable housing’s role in enhancing well-being, a subject that has recently gained traction. Research has increasingly highlighted the multifaceted impact of sustainable housing, from physical attributes to socio-cultural dimensions, in various contexts from the UAE to Scotland (Ibrahim, 2020; Rolfe et al., 2020).

The discrepancy can be attributed to the fact that social outcomes such as a positive sense of place, a feeling of belonging and sufficiency, perceived social equality, and SWB in general are rarely considered in evaluating sustainable housing developments’ success (Badland et al., 2014; Vallance et al., 2011). Such omissions are a part of the long-standing minimization of social development in sustainability practice, but in this context part of the challenge is that we have limited knowledge about how specific housing development factors affect happiness in various cultural contexts, and limited ability to precisely measure such outcomes. Recent research by Ibrahim (2020) alongside Rolfe et al. (2020) emphasizes the importance of localized empirical research to better understand these social dynamics in sustainable housing. These studies highlight the need for context-specific approaches to sustainable housing, which can address unique cultural and social factors. Considerations such as housing costs or energy use are readily quantified, but the impacts of housing development on social inclusion, sense of place, and SWB can be harder to pin down. To better understand and assess these factors, localized empirical research is needed. This led us to pose the specific research questions investigated in this study as follows:

RQ1. How does sustainable retrofitting influence the subjective well-being and sense of place among marginalized Jordanian residents in sustainable affordable housing?

RQ2. How can the insights gained from understanding this influence inform and enhance the quality of life, social sustainability, and overall happiness of both homeowners and the larger community?

The current study was conducted to address this gap in the context of Jordan by identifying factors that participants linked to happiness with their housing situation. The study findings provide insight into Jordanians’ perspectives on their housing needs, and they allow us to make recommendations for improving sustainable building practices in Jordan to address the SWB aspects of the country’s sustainable development goals. In future work these findings will also be integrated into a nuanced and detailed measurement instrument that can be used to assess Jordanian housing happiness outcomes. In contrast to existing general surveys of respondent happiness, the work developed here is specifically tailored to housing-related happiness and to the local cultural context, seeking to identify dimensions of housing that are subjectively important for the Jordanian population. While other metrics such as energy efficiency and sanitation are also highly important, sustainable housing projects cannot achieve their full potential if they fail to account for the social and psychological thriving of inhabitants. Focusing on housing happiness, particularly related to the lived experience of underrepresented, often marginalized populations, helps increase resident buy-in for these projects, increases housing quality, and promotes a virtuous cycle of social cohesion and development.

The researchers conducted interviews and direct observations to better understand the “rich texture” of housing in the lives of economically marginalized Jordanian residents. We were interested in accomplishing three primary goals in the research:

1. Identify essential indicators of perceived housing happiness among low-income Jordanians, which can be used to improve sustainable building practices and, in future work, to develop a quantitative Housing Happiness measurement instrument.

2. Evaluate the relationship between social factors (such as community engagement and access to services) and psychological factors (such as subjective well-being and sense of place) in the Jordanian context.

3. Conduct a preliminary assessment of the policy implications and practical applications of the identified happiness indicators, considering their relevance to sustainable development practices in Jordan.

2 Background

The meaning of sustainability has been described as “shifting” over time and as meaning different things to different actors (Kaidonis et al., 2010, p. 83). The origins of this concept have broad ecological and social dimensions, which continue to be enshrined in documents such as the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations [UN], 2015). In practice, however, sustainability is often reduced to technical performance metrics such as energy efficiency. The current study is part of a research trend that seeks to re-emphasize the social welfare component of sustainability as it relates to housing development. Recent studies further emphasized the significance of sustainable housing in enhancing well-being. For instance, a study on sustainable housing development in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) highlighted the importance of satisfaction based on both physical characteristics and traditional social aspects of housing units (Ibrahim, 2020). Another study from west central Scotland developed an empirically-informed realist theoretical framework, emphasizing housing as a determinant of health and well-being (Rolfe et al., 2020). Complementing these perspectives, earlier research by Hartig et al. (2014) highlight the necessity of integrating natural elements into urban spaces to enhance well-being. Similarly, Scannell and Gifford (2010) emphasize the importance of place attachment, suggesting that emotional connections to the environment play a crucial role in fostering sustainable behaviors and enhancing life satisfaction. These insights guide our exploration into Jordan’s unique cultural and climatic context, stressing the need for sustainable housing designs that address environmental challenges and resonate with local cultural values. Such studies emphasize the evolving understanding of sustainability, moving beyond mere technical metrics to encompass broader sociocultural and well-being dimensions.

A significant interdisciplinary body of research has demonstrated the importance of housing quality for human health and well-being (Diener et al., 1985; Robinson and Eid, 2017; Rojas, 2016; Rolfe et al., 2020; Rüger et al., 2023; Sirgy, 2012; Veenhoven, 1991, 2012). However, in the sustainability context, housing literature most often focuses on resettlement, as is required for the immediate needs of homeless individuals, refugees, and other marginalized people (Adabre et al., 2020). There has been less emphasis on the long-term impacts of housing characteristics for enriching communities and promoting human flourishing (Cummins et al., 2003; Diener et al., 1985; Lubell et al., 2007; Veenhoven, 1991, 2012).

In recent years, there has been a notable shift towards recognizing that ‘green’ designs must thoughtfully address how housing development impacts human social functioning and community stability (Vallance et al., 2011). This evolving perspective emphasizes the need for designs that not only meet environmental goals but also foster social sustainability, ensuring that communities are cohesive, inclusive, and resilient (Abed and Al-Jokhadar, 2021). Furthermore, researchers have noted that a lack of consideration of such “human factors” may result in sustainable designs being rejected or not used as intended, thereby leading to negative outcomes for other aspects of the sustainable development agenda. Even the most visionary and well-funded sustainability programs can fail to meet their goals if they do not consider residents’ lifestyles, behaviors, and opinions (Semeraro et al., 2021; Lafrenz, 2022). Thus, there is a growing emphasis in the sustainable design community on promoting social welfare and pro-social outlooks as an indispensable aspect of ecological and economic stability, as well as an intrinsic good (Kjell, 2011; Stiglitz et al., 2009).

2.1 Overview of the state of sustainable housing in Jordan

While Jordan has made significant strides in various sectors, sustainable housing remains a complex domain influenced by a myriad of factors. The country has grappled with structural challenges and external shocks, including persistent drought, the influx of nearly 1.3 million Syrian refugees, and the ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic (UN-Habitat, 2022a; World Bank, 2020a; World Bank, 2023). The requirements of meeting basic, immediate human needs, particularly for refugees, has often meant that long-term housing development goals are abrogated or postponed, resulting in suboptimal living conditions for a significant portion of the country’s population (UN-Habitat, 2022b). Despite these challenges, the government recognizes the importance of a healthy and productive population and has made efforts to improve access to quality education, healthcare, and housing (Government of Jordan, 2014; United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2019; World Bank, 2018; World Bank, 2020a). Several recent affordable and sustainable housing programs in Jordan, such as the Green Affordable Homes initiative (a collaboration between the Jordan Green Building Council and Habitat for Humanity Jordan), have been particularly noteworthy. Green Affordable Homes made strides in addressing cultural nuances in housing, ensuring not only that the developments were affordable and environmentally sustainable, but also that the homes built resonated with the values and needs of their inhabitants (Habitat for Humanity Jordan, 2019). Similarly, UN-Habitat’s Jordan Affordable Housing Program has emphasized the interconnectedness of environmental concerns with human rights, aiming to provide housing that aligns with the cultural needs and quality-of-life concerns of vulnerable groups (UN-Habitat, 2016; United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], 2017, p. 89). However, despite these promising directions, there is still a significant gap in the country’s overall housing development when it comes to integrating insights about residents’ well-being. A central issue is the piecemeal nature of these programs and the lack of rigorous academic scrutiny to evaluate their outcomes against key indicators. This research seeks to explore this gap, aiming to guide future housing initiatives in Jordan.

As is the case in most regions, cultural norms and traditions play a pivotal role in shaping housing preferences and perceptions for the Jordanian population (Alnsour, 2016). Thus, it is imperative to pursue housing solutions that resonate with these cultural values while also ensuring affordability and meeting other sustainability goals. Previous researchers have noted that when it comes to housing Jordanians generally value privacy, the integrity of family space, and the preservation of social norms (Abed et al., 2023; Al Husban et al., 2021; Obeidat et al., 2022; UN-Habitat, 2015). Their ideal homes would be designed to accommodate extended families and feature designated spaces such as living rooms and guest rooms specifically intended for socializing (Al Husban et al., 2021; Obeidat et al., 2022). These norms may play an important role in effective spatial layout in development projects; for example, it is common to find separate living areas for men and women in traditional Jordanian homes (Abed et al., 2023; Al Husban et al., 2021; Obeidat et al., 2022). At the same time, previous researchers have found that affordability remains a key concern and may be prioritized by many families over traditional living arrangements (Abed et al., 2023; Alnsour, 2016). Previous research has demonstrated that community involvement and access to nearby community spaces are crucial factors valued by Jordanian residents in housing projects (Al-Homoud and Is-haqat, 2019). Specifically, Al-Homoud and Is-haqat’s (2019) study highlights the importance of integrating social services and infrastructure to meet the residents’ needs and enhance their satisfaction. In Jordanian society, the notion of home extends beyond the physical structure to encapsulate familial bonds, social harmony, and collective identity (Abed et al., 2023; Farhan and Al-Shawamrh, 2019). A housing model that disregards these ingrained values stands in discordance with the culture’s embedded notion of well-being and is at risk of being rejected or viewed as demeaning by residents (Farhan and Al-Shawamreh, 2019; Rolfe et al., 2020).

The vernacular architecture of Jordan historically manifested principles of environmental sustainability (Amro and Ammar, 2020; Sokienah, 2020); however, the rapid urbanization of the late 20th century entailed a paradigmatic shift away from ecologically adapted housing designs to models that were often incongruous and out of sync with local climatic and social conditions (Alnsour and Meaton, 2009; Sokienah, 2020). A retrospective examination of these changes illustrates a complex narrative of modernity, ecological disregard, and emergent awareness that eventually culminated in the renewed advocacy for sustainable housing seen today (Alnsour and Meaton, 2009; Sokienah, 2020). Thus, a return to more conventional architectural forms can be understood as part of a shift toward sustainable development. In this regard, and in the context of rapid urbanization and associated environmental vulnerabilities, Jordan may serve as a pivotal case study for exploring the interdisciplinary convergences of sustainable housing, cultural fidelity, and subjective well-being (Alnsour and Meaton, 2009; Ryan and Deci, 2001; Sokienah, 2020).

Despite these insights, gaps remain in understanding how various factors interact to influence housing choices and housing happiness for Jordanians, particularly in relationship to new green developments. The current study was designed to expand upon, confirm, and update these earlier insights, looking particularly at the housing factors that current low-income residents in Jordan most associate with subjective well-being. As we examine deeper into the intricacies of housing happiness in Jordan, it is essential to ground our study in the broader literature that has shaped our understanding of sustainable housing and well-being.

2.2 Foundational literature in the development of the GROW-J framework

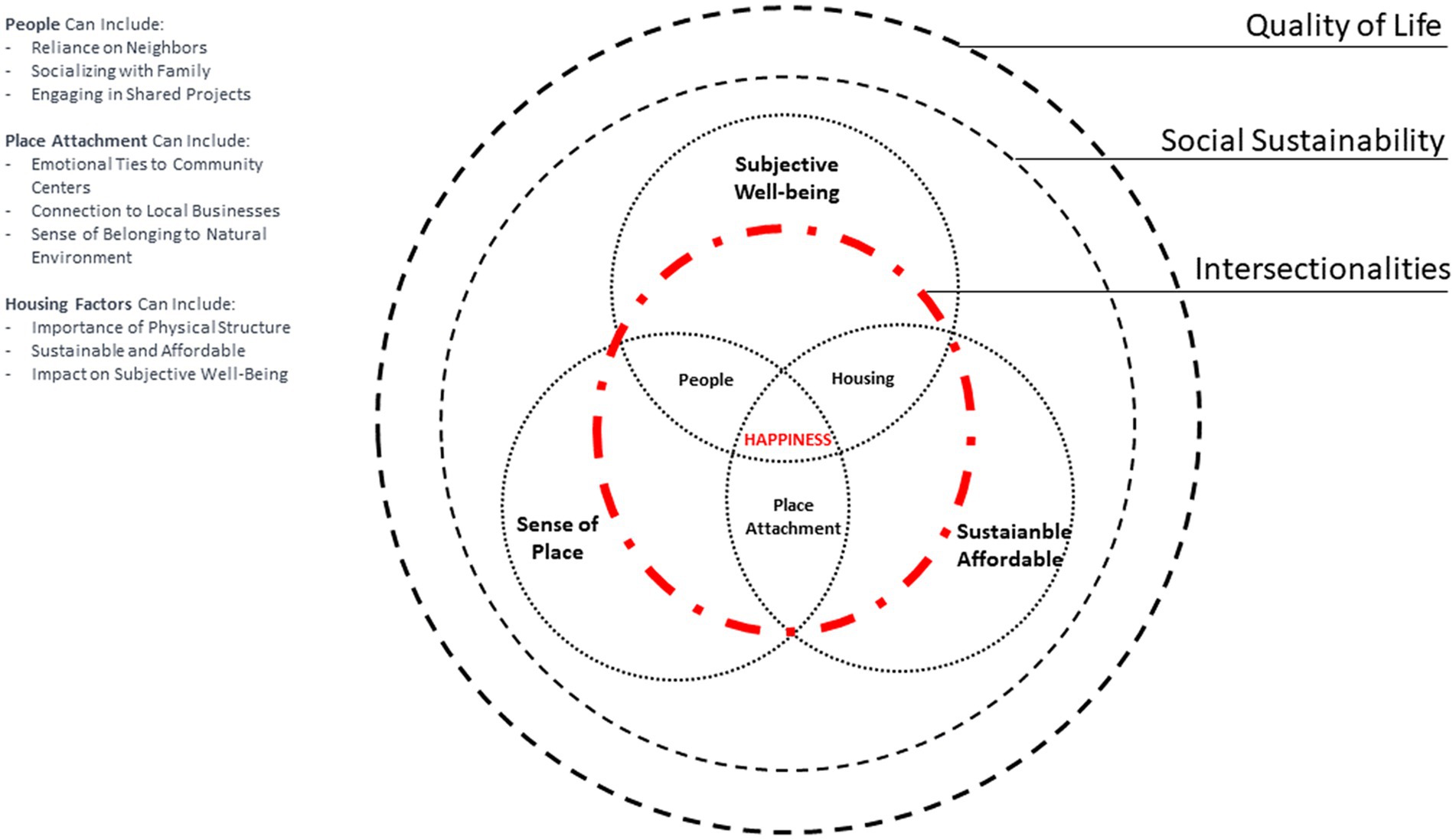

We developed a conceptual framework for this project that we called GROW-J (Growing Residential and Overall Well-being in Jordan). The initial iteration of GROW-J was grounded in existing theories and models related to housing and well-being; this framework was then further developed and localized based on the empirical research results as discussed in Section 5 below. For the initial development, we drew strongly from Diener’s (1984, 2009) foundational work in subjective well-being, along with Diener et al.’ (1985, 1999) contributions, and other authors as discussed in the following sections. We used prior frameworks such as the “Gross National Happiness” metric (Ura, 2015) and the PERMA well-being study (Donaldson et al., 2021) as a foundation for the initial development of GROW-J, while also referring to literature on the role of environmental conditions in personal well-being (Ryan and Deci, 2001; Hansenne, 2021). Based on this prior literature, the framework that we developed was divided into three main components: (a) subjective well-being, (b) sense of place, and (c) merging sustainability with affordability (Figure 2). This initial conceptual development guided the research and helped us to identify what potential topics to consider when discussing housing and happiness with our Jordanian participants.

2.2.1 Relevant literature on subjective well-being

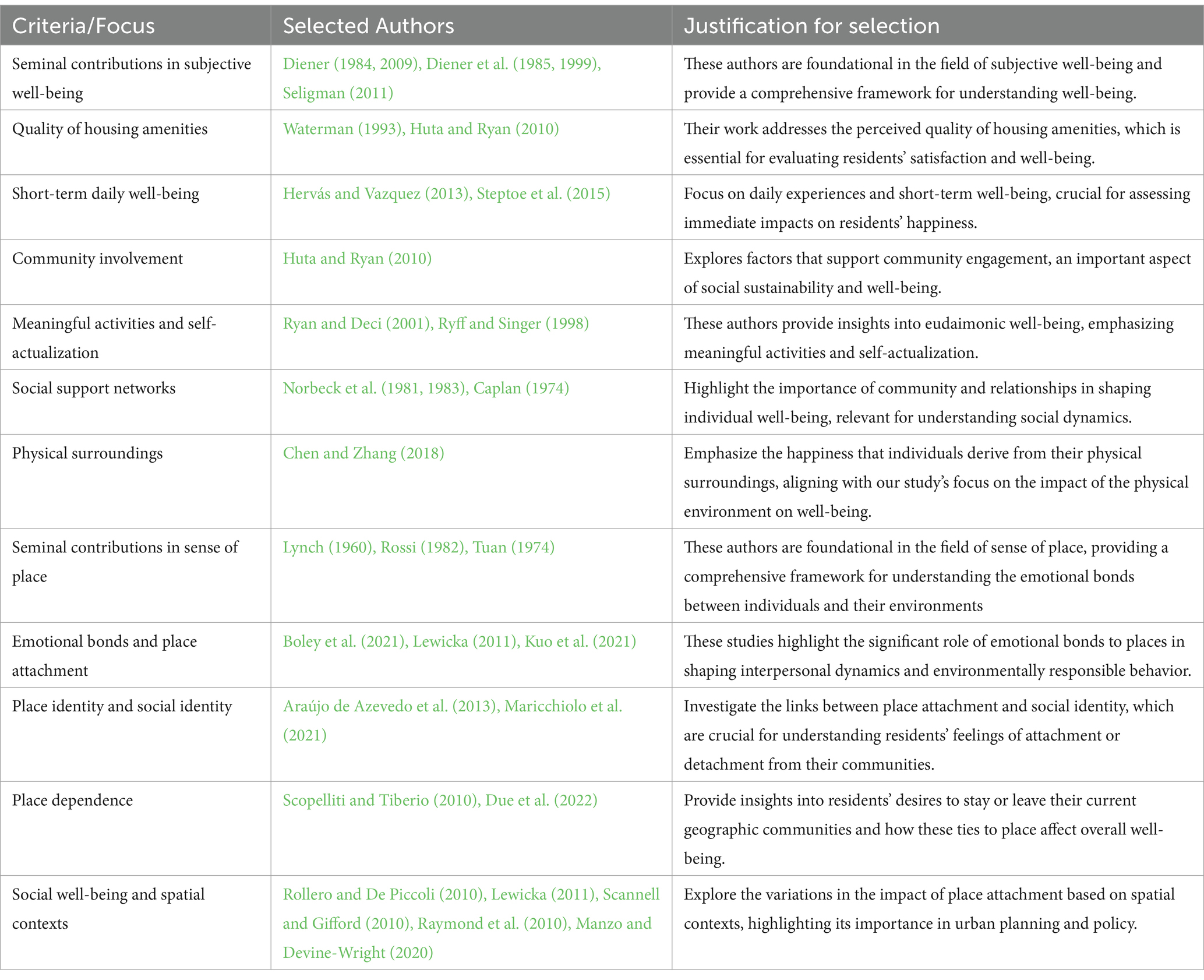

Discussions of well-being, which encompass emotional and psychological dimensions as well as economic and material factors, provided a foundational perspective for our study (Diener, 1984, 2009; Diener et al., 1985, 1999; Rastelli et al., 2021; Seligman, 2011). These authors were selected based on their seminal contributions to the field of subjective well-being and their direct relevance to the dimensions we sought to explore in our study. In developing our interview questions, we also incorporated topics about the perceived quality of housing amenities (Waterman, 1993; Huta and Ryan, 2010), short-term daily sense of experienced well-being (Hervás and Vazquex, 2013; Steptoe et al., 2015), factors supporting community involvement (Huta and Ryan, 2010), and sense of participating in meaningful and valuable activities (Huta and Ryan, 2010). This approach therefore merged both “hedonic” concepts of well-being and “eudaimonic” concepts of self-actualization (Ryan and Deci, 2001; Ryff and Singer, 1998). This dual focus was pursued to ensure that our framework captured both the immediate joys and the more enduring aspects of residents’ well-being. Recognizing that well-being is also a function of one’s social environment, our framework integrated the understanding of social support networks from Norbeck et al. (1981, 1983), and Caplan (1974) which highlighted the pivotal role of community and relationships in shaping individual well-being. Finally, we drew from Chen and Zhang (2018), who emphasized the happiness that individuals derive from their physical surroundings. The selection criteria and detailed rationale for including these authors are summarized in Table 1.

2.2.2 Relevant literature on sense of place

The emphasis on ‘sense of place’ in GROW-J is rooted in existing literature that underscores the profound connection between individuals’ emotional bonds to places and their overall well-being. Boley et al. (2021) highlighted the pivotal role of such emotional bonds in shaping interpersonal dynamics. Lewicka (2011) provides a comprehensive review of place attachment, emphasizing its significance in urban planning and policy. Similarly, Kuo et al. (2021) identified a direct relationship between place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior and intentions. Exploring the phenomenon of place attachment further, Araújo de Azevedo et al. (2013) and Maricchiolo et al. (2021) investigated the intricate links between place and social identity. Their insights have been instrumental in shaping our research questions, especially those that probe residents’ feelings of attachment or detachment from their local environment and communities.

We also draw upon the work of Scopelliti and Tiberio (2010) and Due et al. (2022), who have developed the concept of “place dependence.” Their research adds depth to our understanding of how residents may desire to leave or stay in their current geographic communities, and how these ties to place affect overall well-being. Adding to the understanding of the nuanced relationship between place attachment and well-being, Rollero and De Piccoli (2010) explored their influence on the five components of social well-being among first-year undergraduates. Their study revealed variations in the impact of place attachment based on spatial contexts, such as neighborhood versus city, emphasizing the need to consider these various spatial contexts in research. Lewicka (2011), Scannell and Gifford (2010), Raymond et al. (2010), and Manzo and Devine-Wright (2020) further elucidate the psychological benefits of place attachment and its significance in urban planning and policy. Additionally, the foundational contributions of Lynch (1960), Rossi (1982), and Tuan (1974) have been instrumental in understanding the theoretical underpinnings of place attachment and sense of place. Their seminal works have laid the groundwork for contemporary studies and are essential for a comprehensive understanding of these concepts. A detailed rationale for including these authors is outlined in Table 1.

2.2.3 Relevant literature on merging sustainability with affordability

We included an emphasis on affordability and environmental sustainability in our framework with the understanding that these variables may have a secondary impact in shaping residents’ social engagement opportunities and psychological well-being (Turcotte and Geiser, 2010; Winston and Pareja Eastaway, 2008). It is notable in this context that long-term affordability must be considered; for example, housing that lacks energy-efficient features may initially be more affordable but can lead to escalated costs over time, both individually and socially. Conversely, housing development that focuses exclusively on ecological sustainability without considering affordability can result in solutions that, while environmentally commendable, are economically prohibitive for a broad segment of the population. These complex interactions between sustainability and affordability have been noted by prior researchers such as the influential groups such as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] (2020); and they are integrated into the points of emphasis enshrined in the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations [UN], 2015).

Recent research has further illustrated the potential benefits of sustainable housing for low-income households, emphasizing both direct and indirect advantages related to social equity, health, and well-being (Ebbini and Al-Assaf, 2018). In particular, the housing environments’ impact on mental well-being has been emphasized, especially concerning Syrian refugees in Jordan, pointing to a pressing need for improved housing policies (Al-Soleiti et al., 2021). Although the current study did not specifically focus on the refugee population, the challenges they face serve as a poignant reminder of the broader housing crisis in Jordan. This crisis affects various segments of the population, emphasizing the importance of our research in identifying and addressing the housing factors that Jordanians associate with happiness and well-being. These studies reiterate the importance of merging sustainability with affordability, ensuring that housing solutions cater to both environmental and human needs.

A closely related body of literature focuses on “social sustainability,” which refers to residents’ ability to live healthy and productive lives and to feel psychologically secure (Atanda, 2019; Atanda and Öztürk, 2020; Colantonio, 2009; Fatourehchi and Zarghami, 2020; Richter et al., 2023; Vallance et al., 2011). In formulating our interview questions, we sought to assess how participants leveraged the benefits of the implemented retrofitting against other happiness-related concerns. Furthermore, we explored how factors like affordability, age, ethnicity, and gender might influence residents’ perceptions of sustainable development and intersect with broader themes of social sustainability (Fatourehchi and Zarghami, 2020; Richter et al., 2023; Thomson et al., 2013).

2.3 Role of the current study in the overall research trajectory

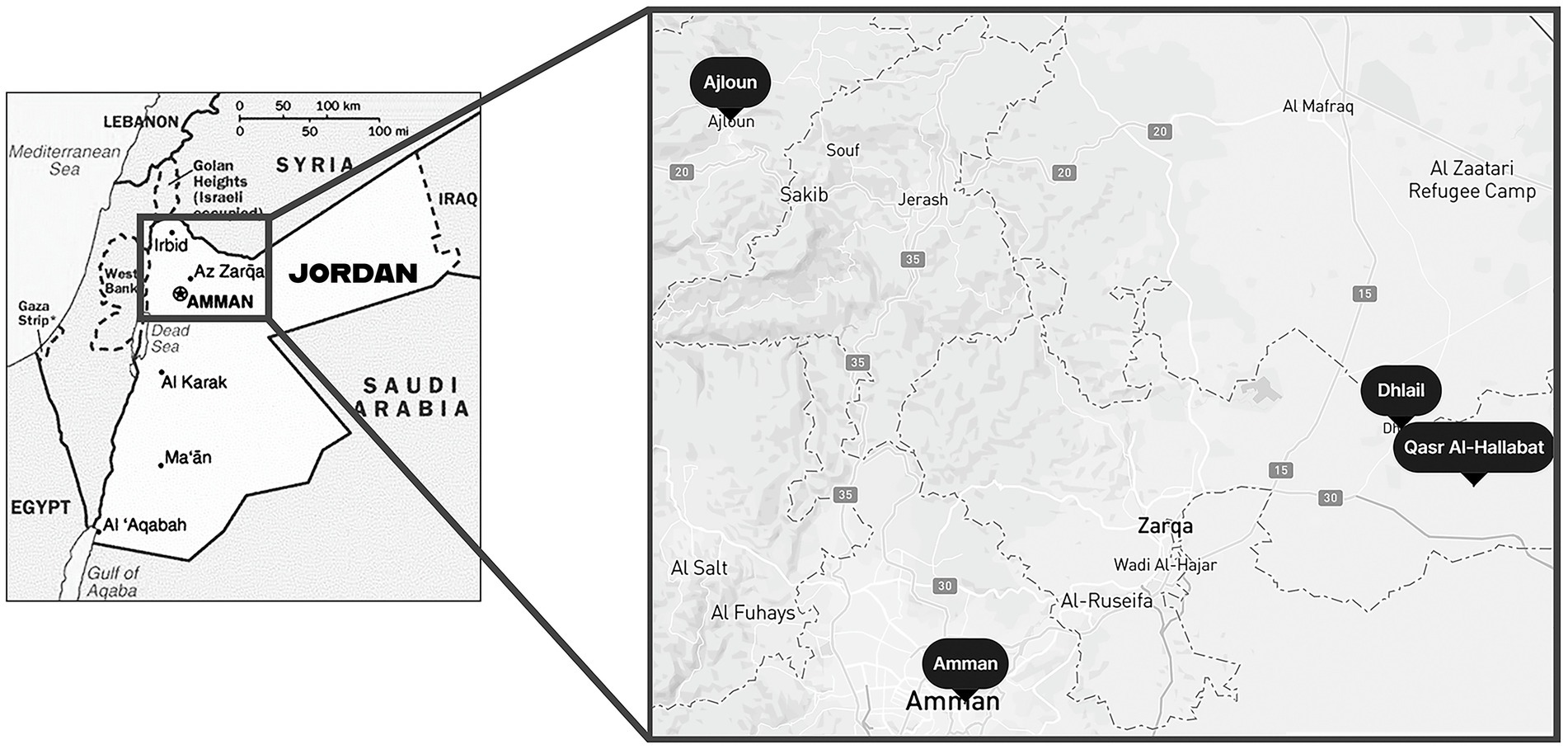

Our collective research direction concerning housing happiness in Jordan is illustrated in Figure 1. The areas of Qasr Al-Hallabat and Ajloun, consistent with the initial “Pilot Study” and “Study 1,” are demarcated with a dotted square in Figure 1 and laid the groundwork for the subsequent phases of the research trajectory. These regions were chosen due to their contrasting socio-economic and cultural contexts. They offer a comprehensive perspective on housing happiness across diverse Jordanian settings. Their involvement in the Jordan GBC’s Green Affordable Homes initiative further emphasized their relevance. This aligns with our overarching focus on sustainable and affordable housing.

Building on the foundational studies by Ebbini and Al-Assaf (2018, under review) that examined Jordan’s sustainable development practices and policies, the initial exploration into “Knowledge Gap 1” was undertaken (as illustrated in Figure 1). This foundational study examined Jordan’s sustainable development practices and policies. The current study addresses “Knowledge Gap 2,” focusing on identifying residents’ outlooks and perceived needs. The aim is to empirically discern which housing factors are most closely associated with happiness among Jordanians, to categorize these factors within the GROW-J framework, and to propose some overarching policy recommendations based on these findings.

In future research we will also address “Knowledge Gap 3,” which is an evaluation of specific ways in which human-centered design practices can be effectively integrated into Jordan’s sustainable construction industry. For clarity, the gray square in Figure 1, highlights the next pivotal phase of our research, which will be discussed in detail in section 5.2. This will include the development of a Housing Happiness Index instrument to quantitatively measure the outcomes of building practices. This future work will necessarily rely on the empirical findings of the current study, because happiness-producing construction practices cannot be identified or evaluated until we have a solid knowledge of local residents’ happiness needs. In line with the findings of Adamec et al. (2021), sustainable housing is not just about improved environmental performance. It is a comprehensive approach that considers the entire lifecycle of a dwelling, from its design phase to its eventual end-of-life stage. This perspective on sustainable housing aligns with the direction of the current study and stresses the importance of evaluating housing solutions holistically, considering both sustainability and well-being. Such insights further validate the direction of our research, emphasizing the need to holistically evaluate housing solutions in the context of sustainability and well-being.

3 Methods and research design

Our research design used in-depth semi-structured interviews combined with direct observations of participants’ lives. We adopted an interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) method in collecting this data (interviews and observations) and in subsequently analyzing and triangulating the results. IPA is particularly well-suited for investigations of participants’ perceived needs and outlooks, because it allows researchers to remain flexible and open to emerging, nuanced themes in the data rather than simply evaluating preconceived hypotheses. This approach allows researchers to learn about how individuals make sense of their own subjective lived experiences, which is essential for topics that require cultivating an in-depth understanding of human feelings and emotions (Eatough and Smith, 2008; Smith, 2004). Given the research’s alignment with the previously mentioned contextual gap, this approach ensures that participants’ lived experiences are seamlessly integrated into our established conceptual framework (Smith et al., 2021).

3.1 Participant recruitment

Building on the foundational work conducted in the “Pilot Study” and “Study 1” as detailed in Section 2.3, our current research phase continued to focus on the residents associated with the Jordan Green Building Council’s Green Affordable Homes initiative. This initiative’s list of enrolled residents served as our primary recruitment source, emphasizing the retrofitting housing in Ajloun and Qasr Al-Hallabat. Collaborating with a local architect, Mohammed Musleh, who had close ties with Green Affordable Homes, we engaged community-based organizers (CBOs) to connect with potential participants. These CBOs played a pivotal role in reaching out to residents, to gauge their interest in joining our study. We provided an informative handout to potential participants (in Arabic) explaining the purpose of the research and clarifying that involvement was entirely voluntary and unrelated to their housing benefits (Bhattacherjee, 2012). The study employed purposive sampling, a non-probability sampling technique, to select participants based on their specific characteristics and relevance to the research objectives. The criteria for inclusion were residency in either retrofitted homes or newly-built green affordable homes as part of the Jordan Green Building Council’s initiative. There were no specific exclusion criteria. Incentives for participation were not provided; however, following cultural customs the researchers brought a gift of sweets to each family when arriving for interviews and observations.

All study participants lived in the areas of Qasr Al-Hallabat (including nearby Dhlail) or Ajloun (Figure 3 and Table 2). Qasr Al-Hallabat is located in the eastern part of Jordan, lying amidst a desert landscape, dotted with sparse vegetation. It is known for the historical Qasr Al-Hallabat desert castle, which is part of a broader series of ancient desert castles scattered around the region. The area can be categorized as a semi-rural location, with a history rooted in Bedouin traditions and culture. The economic structure of Qasr Al-Hallabat is primarily based on modest farming and limited tourism. Most residents rely on small-scale agriculture, with plots dedicated to growing basic crops, and herding, given the pastoral tradition of the Bedouins. Despite its historical significance, the area does not draw significant tourist crowds, primarily due to its remote location. The majority of its residents fall within the low-income bracket. Socially, the community is tight knit, with strong family bonds and shared cultural traditions. The primary ethnicity is Arab Bedouin, which influences the local customs, traditions, and even the dialect spoken.

Ajloun, situated in the northern highlands of Jordan, offers a stark contrast to Qasr Al-Hallabat. It is surrounded by dense forests and is a hub of biodiversity. The town is known for the Ajloun Castle (Qala’at Ar-Rabad), a 12th-century Muslim castle built atop the ruins of a historic monastery. The castle, apart from its historical significance, offers panoramic views of the Jordan Valley, attracting both local and international tourists. The economy of Ajloun is a blend of agriculture, local crafts, and tourism. The fertile land supports olive and fruit cultivation, and many households are engaged in producing high-quality olive oil. Handcrafted items, like basketry, are also prevalent in local markets. Unlike Qasr Al-Hallabat, Ajloun does see a significant influx of tourists, which helps sustain the local economy. While the town is more economically dynamic than Qasr Al-Hallabat, the majority of its residents still fall within the low to middle-income bracket. Ethnically, Ajloun is predominantly Arab, with communities that have been settled in the region for generations, including both urban and rural populations.

We successfully engaged 36 individuals distributed among 16 households in Qasr Al-Hallabat and 11 households in Ajloun (in some cases there were multiple participants per household). In line with the Interpretative Phenomenological (IP) approach adopted for this study, a sample size of 36 individuals was chosen to ensure depth and richness in capturing participants’ lived experiences. The sample size was determined based on the availability of participants and the feasibility of conducting in-depth interviews and observations within the study’s timeframe and resources. This approach ensured a sufficient number of participants to capture diverse perspectives while accommodating practical constraints. This size aligns with recommendations for IP studies, emphasizing detailed exploration over breadth (Smith et al., 2021). During most of the interviews there were other immediate family members present who did not vocally participate; these individuals were not counted as participants. Participants were identified as either female or male, reflecting the predominant gender identities recognized within the cultural contexts of the study locations, no other gender identities were reported. For those who did participate, 77.78% (n = 28) presented as women and 22.22% (n = 8) presented as men, with no individuals presenting in an ambiguous or gender-neutral fashion. For a detailed breakdown by household, refer to Table 2. Participants were asked to report their age verbally; these ages ranged from 35 to 60 years, with a mean age of 47.5 years (SD = 10.27 years). We did not collect data on other demographic factors, but the fact that they were living in the Green Affordable Homes project indicates that all participants were low-income.

The study procedures were approved by the Internal Review Board at Purdue University, Main Campus and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to research activities. To protect participant anonymity, we assigned a number to each participant’s data and did not retain identifying personal information.

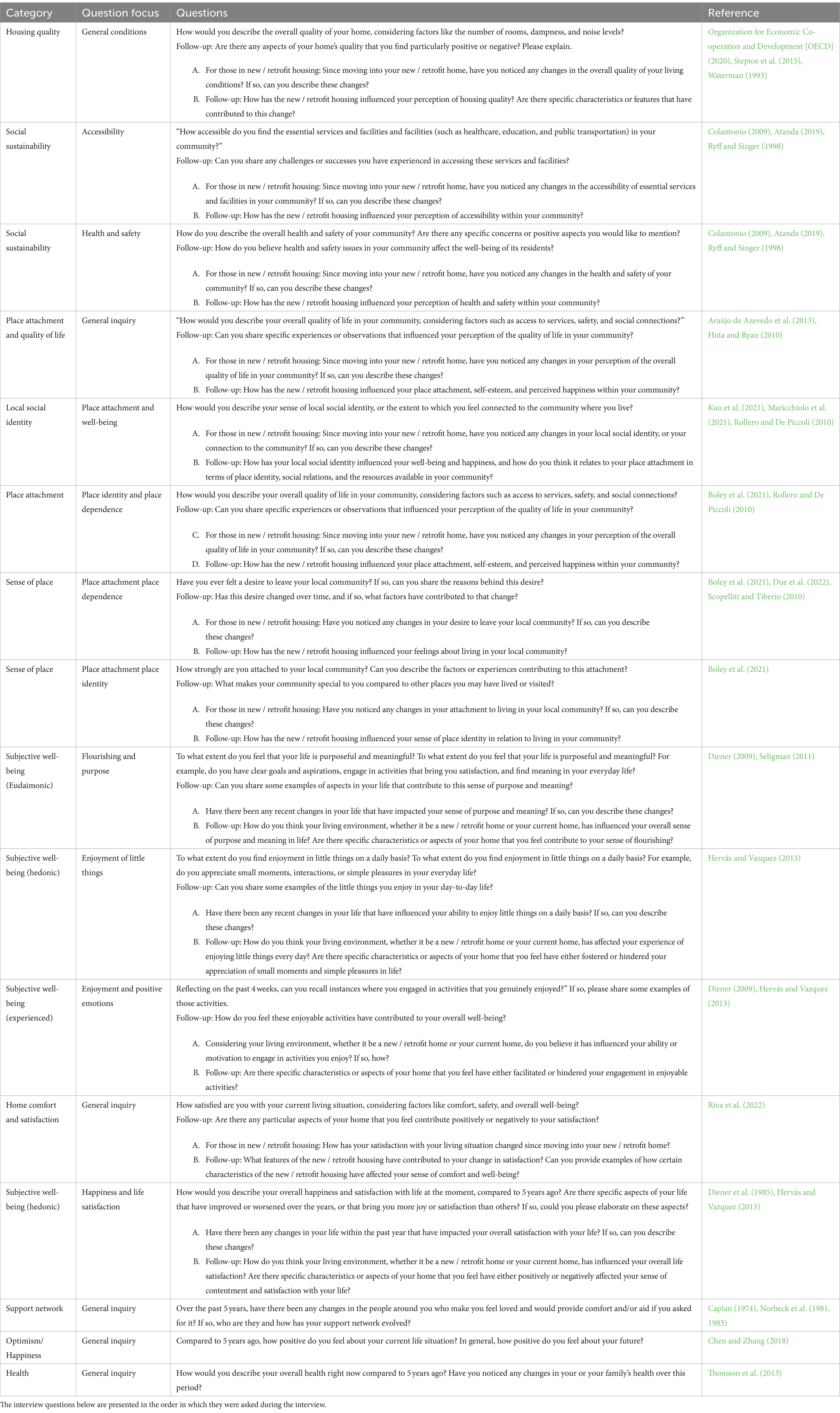

3.2 Interview questions

We grounded most of the interview questions in the three components of our initial GROW-J framework, including subjective well-being, sense of place, and the integration of sustainable/affordable. For example, under subjective well-being, participants were asked about their daily emotions, general life satisfaction, and long-term life achievements (echoing both hedonic and eudaimonic concerns) and were invited to link those perceptions to aspects of their housing environment. To capture the diverse perspectives of our participants, we included questions that specifically addressed cultural and historical contexts, and how these influenced their perceptions of housing and well-being. This approach ensured that we integrated the ‘different ways of seeing and interpreting the world’ into our complex methodology, providing a richer context for our findings.

In addition to covering the three main GROW-J components, we asked specific questions about the characteristics of participants’ homes (layout, number of rooms, noise levels, etc.), and about access to nearby services in the community. An overview of the questions is provided in Table 3, which serves as the comprehensive in-depth interview guide, detailing all the questions asked during the interviews. Additionally, while a formal observation schedule was not used during the interviews to respect cultural norms and ensure a natural interaction with participants, a structured observation schedule based on the GROW-J framework has been developed and included as Supplementary material 1 to provide a clear outline of the observational points considered during the data collection process.

3.3 Data collection and analysis

To enrich our data collection process, we employed visual ethnography techniques by taking photographs of the living environments, with participants’ consent. These images provided additional context for our analysis and helped triangulate the data collected through interviews and observations. This multi-method approach enhanced our understanding of participants’ lived experiences and ensured a comprehensive analysis.

The interviews were conducted in the summer of 2023. They took place in the participants’ homes, in areas that the participants selected, most often living rooms, gardens, and/or exterior patios. All the interviews were conducted by the same bilingual (native Arabic and English) female researcher, to help ensure standardization across participants (Bhattacherjee, 2012). The visiting team also included a second researcher, a fieldwork organizer, and the local CBO, all of whom interacted cordially with the household’s members in accordance with local customs. As per Jordanian tradition, the families typically served refreshments such as tea, candy, and fruit (collected from their gardens), and often multiple non-participant family members were present during the interview process. As noted in Section 3.1, during most of our visits a single household member took the lead in responding to the interview questions; however, in some of the households more than one individual responded in sufficient depth that we included each of them as study participants. The interviews were conducted in Arabic and lasted between 15 to 60 min. We audio-recorded the interviews with the explicit permission of the participants. These recordings were transcribed in Arabic and subsequently translated into English. It is important to note that while translating, we aimed to capture the essence of the responses, recognizing that many Arabic phrases lack direct English equivalents. Therefore, the direct quotes presented in Section 4 (Results) have been contextually interpreted, taking into account the regional dialects of Ajloun and Qasr Al-Hallabat.

Parallel to the interview process, observational data were recorded by the primary research interviewer, the second researcher, and the fieldwork organizer. These observations focused on several factors. First, we recorded participants’ relevant non-verbal cues and gestures, which might hint at underlying sentiments or reveal information not fully captured in the audio recordings. Second, we made a note of any family dynamics among the household members that might have bearing on the interview data. Finally, we observed the houses themselves (the areas into which the participants invited us), including any local adaptations that had been made by the residents or any particular features that the participants pointed out to us. Such a holistic approach to data-gathering provides a richer context to the spoken words of the interviewees. To ensure a structured approach to our observations, we have created a detailed observation schedule based on the GROW-J framework, which is included as Supplementary material 1.

Each interview was transcribed verbatim in Arabic and then translated to English and analyzed through a rigorous coding process, supported by qualitative data analysis software (NVivo; Bhattacherjee, 2012). Initial codes were grouped into emergent themes to identify frequently expressed perspectives, which were then triangulated against the observational notes to ensure a comprehensive analysis.

4 Results

The data collected during this study provided several important insights about the low-income Jordanian residents’ views of housing and happiness. The findings are presented below, organized according to the research questions stated in the Introduction.

4.1 Influence of sustainable retrofitting on subjective well-being and sense of place (RQ1)

4.1.1 Social integration and community bonds

One of the central findings was that participants expressed a consistently high preference for socially integrated housing; that is, living in closely-knit neighborhoods in which they were clustered together with other households whom they perceived to share similar social characteristics. This phenomenon was affirmed in both of the areas where the study took place (Qasr Al-Hallabat and Ajloun). In general, social bonding and networks were the factors that had the most profound impact on participants’ satisfaction with their housing situation, as expressed through “knowing and trusting one’s neighbors” and being able to participate in activities with neighbors.

For example, participant 08H emphasized this sense of community by stating that: “I feel we all are one family. The bonds we share as one rural community make us more positive and productive. Whenever a member of the community has any social occasion, we all come together to help, whether it’s weddings, graduations, or times of mourning.” Participant 01H highlighted how all the women in her neighborhood enthusiastically respond to calls for workshops and productive activities initiated by the neighborhood committee, making items such as pickles and jam to sell (Figure 4). She then continued to state: “I have lived here my entire life. The houses are always open and welcoming. I have a front yard that keeps me connected to both people and nature.” This strong sense of neighborhood community and stability emerged as a crucial factor that needs to be considered in Jordanian development projects for the sake of resident happiness.

Figure 4. Women engaging in collaborative neighborhood farming and entrepreneurship (photos taken by authors).

4.1.2 Impact of retrofit measures

Participants linked their commitment to the local community with a desire to diligently maintain their homes, and this affected their positive reception of retrofit measures enacted under the Green Affordable Homes program. Multiple participants commented on the fact that these investments made them feel that they were contributing to the quality of the neighborhood and would support their esteem in the local community, which contributed to their happiness. We observed that it was common for the participants to have made their own sustainability-relevant home modifications even outside of the program’s contributions, for example by using locally sourced bamboo to create attractive window shades aimed at mitigating the impact of the intense southern sun (Figure 5). The unique topography of Ajloun, characterized by its rolling hills and dense forests, has influenced the residents’ views on sustainability. The region’s specific climate conditions necessitate certain sustainable practices, such as water conservation and energy-efficient housing, which were frequently highlighted by our participants. Another frequently expressed outcome of the retrofit was that it improved participants’ practical ability to contribute to their family and local community. Participant 12H attested that the installation of solar hot water panels enabled her to address other essential household needs for her children, adding that: “The fact that I no longer need to spend time heating the water for our daily routines brings comfort, especially during early mornings when everyone has to prepare for school. Also, it saves money and provides more time to tend to my plants and garden.” These findings highlight the centrality of community life for these participants and the value of appealing to socially positive outcomes and activities, in contrast to individualist gains, when discussing the benefits of sustainable development in Jordan.

4.1.3 Access to essential services

The ability to access essential services, such as hospitals and schools, was a common complaint among these residents. For example, all of our participants who lived in Qasr Al-Hallabat brought up problems associated with getting to and from the city of Dhlail, which is their nearest urban center for accessing many services. Public transportation was reported to be infrequent and unreliable, which meant that residents often had to pay for an expensive taxi or else walk the entire 12.0 km (7.4 miles) into town, and then walk back again. Even in this regard, however, the participants focused on the value of the local community, discussing how a few individuals who owned private automobiles would often organize carpools to help their neighbors travel to the city. Overall, we found that in both the hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of subjective well-being, the study participants consistently positioned the maintenance of neighborhood relationships as a crucial aspect of the housing-related concerns, and a primary resource for fostering their sense of place (Rastelli et al., 2021).

This same pattern continued when it came to a sense of place, which for our participants was associated much more strongly with people than with any aspects of the natural environment or surroundings. They unanimously expressed that their familiarity with neighbors, coupled with a deep-rooted sense of an extended family, prompts feelings of safety, reduced stress, and willingness to readily offer help. For example, they often relied on neighbors to care for their children in times when they were away from the home or traveling. This strong sense of community is the main thing that fostered an attachment to their locality. As participant 13H poignantly put it, “Our home extends beyond its four walls. It reaches out to the neighbors who are a part of our lives. Here, we support each other in every way necessary. That’s the beauty of this community, and that’s what makes it home for me.” In Qasr Al-Hallabat, the historical landmarks and ancient ruins have fostered a deep-rooted sense of belonging among the residents. This historical backdrop amplifies their attachment to the community, as evidenced by Participant 08H’s statement about the bonds they share. Similarly, the rich cultural heritage of Ajloun, with its renowned castle and traditional events, has shaped the residents’ perspectives on community and housing.

4.1.4 Community projects and collective responsibility

Participants explained that neighbors in their areas often banded together to accomplish community projects, further tying them to the place that they inhabit. In addition to the gardening and entrepreneurial projects discussed above, during the time in which we were conducting interviews, participants in Qasr Al-Hallabat were involved in a campaign urging Jordan’s Ministry of Education to address the dire state of the community’s sole, deteriorating school. In a powerful display of solidarity, the women of the neighborhood organized a three-days local strike, acquiring significant media attention and applying pressure to expedite the construction of a new school building. The project is now operational and provides education up to the ninth grade (Figure 6). Participant 01H expressed that, “This is not just about a building; it’s about the foundation of our future. Coming together to get this school built, that’s what community is. And now we are more motivated than ever, looking at what we have achieved; we are already talking about rallying for a local clinic.” Several of our participants pointed to these efforts as an indication of how they developed a sense of place and feelings of belonging, with some indicating that they were eager to adopt a similar approach to advocate for the establishment of a local clinic.

Figure 6. Members of the community were able to pressure the ministry of education into building a new local school (photo taken by authors).

This sense of collective responsibility has extended to the study participants’ efforts to maximize the advantages derived from home retrofitting, for example by pitching to assist with the care of newly planted trees, even when those trees are not in their own yards. Neighbors have also shared information about the benefits of the program and its offerings, encouraging others to prepare to take advantage of future initiatives. For example, participant 09A shared, “When we got the solar hot water panels installed, my neighbor came over and I explained how much we were saving on the electric bills. I showed him how the panels worked, and now we both have them, in addition to other families in the community. We’re not just saving money; we are doing something good for all of us.” This indicates the profound value in the Jordanian context of leveraging community relationships to create buy-in for the value of sustainable development.

In Ajloun, the presence of nearby cultural heritage and touristic locations meant that many of our participants were involved in local businesses catering to outsiders. For example, participant 01A, whom we interviewed had converted part of her front yard into a restaurant, and others had leased rooms to visiting tourists. While this created faster income than farming, some of the participants expressed concerns that it might also lead to an erosion of the community fabric. Again, in this context, it was amply demonstrated in our interviews that the sense of place for these residents was directly connected to their relationships with their neighbors, more so than to environmental features such as local attractions.

4.2 Enhancing quality of life, social sustainability, and overall happiness (RQ2)

4.2.1 Perceptions of sustainability and affordability

In regard to perceptions of sustainability and affordability, the Green Affordable Homes program has had a transformative impact on the community’s environmental consciousness. “More people are recognizing the importance of sustainable housing. It’s a trend growing in our neighborhood,” one participant observed. This heightened awareness is not merely theoretical; it translates into tangible benefits. “We have saved 50% of our electricity bill through solar hot water heaters—we use the savings to spend on the children,” another participant added. However, this newfound enthusiasm for sustainability is tempered by the realities of affordability. Participant 14H encapsulated this tension, “Sustainability is not a luxury for us; it’s a necessity. But how do we balance that with the immediate needs of providing for my family?” The primarily agricultural landscape of Qasr Al-Hallabat shapes the residents’ perspectives on housing and sustainability.

The emphasis on gardens and water conservation is not just an environmental concern but is deeply tied to their livelihoods. As Participant 05A mentioned, their gardens are not just sources of food but symbols of pride and sustainability. This sentiment was reiterated across the community, highlighting the delicate balance between long-term sustainability goals and immediate, pressing needs. As participant 11A succinctly stated, “We want to do right by the environment, but first, we have to do right by our children. You cannot think about tomorrow when today is a struggle.” The participants also spoke about the practical aspects of sustainability that are woven into their daily lives. Participant 13H noted, “We reuse water in our homes for different purposes; it’s not about being ‘green’ as much as it is about necessity. When you have to count every drop, you naturally become sustainable.” Social and cultural norms further complicated the affordability issue, as Participant 01H explained, “In our community, you are expected to host relatives and neighbors frequently. How do you reconcile that with water and energy conservation? It’s not just about the bills; it’s about our way of life and social traditions.”

4.2.2 Home features and community impact

When it comes to the specific features of their homes, participants displayed a blend of traditional values and a growing awareness of sustainability. Alongside these traditional elements, there is an increasing interest in sustainable features. Participant 08H, who commented on the retrofit of energy-efficient windows, said, “I never thought windows could make such a difference. Now, the house stays cooler, and dust free.” The concept of gardens emerged as a focal point in the discussion about sustainable living. For example, participant 13H, “Our garden is more than just a place to grow food; it’s a place to grow relationships.” This sentiment was echoed by others who saw the garden as a tangible manifestation of their collective commitment to a sustainable future.

The participants were pragmatic in their approach to sustainability within the confines of their homes as shared by participant 07A, “We cannot afford solar panels, but we have started using energy-saving bulbs.” While a few families could not afford solar panels, the majority managed to integrate them, significantly reducing utility bills and enabling participants to address other needs, such as expanding their homes by adding guest sitting rooms, decorating interior spaces, creating outdoor living areas, and building second-story extensions to accommodate growth of their families—this trend was evident in both Qasr Al-Hallabat and Ajloun (Figure 7). The concept of edible gardens was particularly popular, as Participant 05A explained: “We may not have fancy technology, but our small gardens are a source of both food and pride. When you grow your own tomatoes, you are not just feeding your family; you are also teaching your children about where food comes from.” Water conservation was another significant theme. “We collect rainwater for our plants. It’s a small step, but it’s something,” Participant 05A said. This practice was not just about sustainability but also about survival, given the harsh climatic conditions of the region.

Figure 7. Measures of home improvements. The images illustrate various enhancements, including outdoor living spaces (left), construction of second-story extensions (center), and improved interior living spaces (right; Photos taken by authors).

The study’s findings highlight the intricate relationship between sustainability, affordability, and community in shaping the housing preferences of low-income Jordanian residents. As participant 01H aptly summarized, “Sustainability is not just about individual choices; it’s a community journey. And on this journey, we carry each other’s burdens and share each other’s joys.” The participants are not passive actors in this discourse; they are actively making choices, within their means, to better their living conditions and reduce their environmental footprint. These choices are collective expressions of a community striving to harmonize their immediate needs with a longer-term vision for sustainability.

5 Discussion, implications, and applications

The researchers conducted fieldwork with economically marginalized residents in Jordan to determine what type of housing sustainability initiatives are most likely to have an impact on their subjective well-being and are most likely to be enthusiastically accepted. This “human-centric” approach is significant because it places the experiences and needs of the residents at the forefront of the research, aiming to understand and address their specific preferences. Subjective factors are often overlooked in current practice—for example, in a study by Ekhaese and Hussain (2022), while they explored how factors of psychosocial well-being influence the happiness of residents in a green residential community, the happiness, satisfaction, or well-being of building occupants were not the primary focus in the context of sustainable, affordable housing development. Similarly, Rolfe et al. (2020) correlated housing service provision, tenants’ experience of property quality, and aspects of the neighborhood with measures of health and well-being but did not list these subjective factors among the significant issues to consider in sustainable, affordable housing development. The current study’s approach to center residents’ felt needs therefore fills a vital gap in the existing literature and practice and engages with questioning real challenges of achieving sustainability within a constrained environment. This aligns with the perspectives outlined by Das et al. (2020) on the importance of integrating psychological and public health viewpoints to understand subjective well-being (Das et al., 2020).

When considering the study’s findings, it is important to keep in mind that there may be great regional and demographic variation in happiness factors. Our results are specific to the interviewed population of low-income Jordanians, and additional empirical and comparative work would be needed to evaluate their application in other contexts. Even within our current study, we found some notable differences between the two sites. In Qasr Al-Hallabat, residents placed a relatively greater emphasis on shared community projects and neighborhood relations, an outlook that resonates strongly with the work of Boley et al. (2021), Huta and Ryan (2010), and Maricchiolo et al. (2021). The participants in Ajloun placed a relatively higher value on immediate family interactions and the quality of the physical home environment, which is similar to concepts discussed by Riva et al. (2022) and Chen and Zhang (2018). This suggests that even within Jordan, a one-size-fits-all approach to housing policy may be inadequate. Instead, housing initiatives that aim to be both sustainable and human-centric should make efforts to consider the specific human dynamics of different communities. In Qasr Al-Hallabat, an emphasis on community-oriented building (shared outdoor neighborhood spaces, public transportation, a new local clinic, etc.) would be highly advisable; whereas in Ajloun, policies that prioritize family-friendly housing features, such as open-concept designs and private gardens, may be more enthusiastically accepted and produce more happiness for residents.

Economic differences between the two study sites can be understood as part of these varying outlooks on housing and happiness. While both communities are low-income, financial resources as well as government services are relatively sparser in Qasr Al-Hallabat. This neighborhood widely uses a direct barter system when trading goods, and families often share essential resources such as water and electricity, a form of interdependence that likely contributes to their prioritization of collaborative social projects. Residents in Ajloun tended to showcase a different form of resilience, focused on narrower family ties and on embracing an entrepreneurial spirit within the country’s larger market system. Many of our participants in Ajloun, especially the women, had successfully launched small, home-based enterprises that contributed to their household income and served as a locus of perceived empowerment. A compelling case in point is Participant 01A, who transformed part of her home into a successful restaurant that became a popular destination for tourists visiting the region. This business was a significant point of pride for the participant that she frequently linked to her sense of happiness; it also served to provide job opportunities for nearby neighbors, contributing to social stability and cohesion (Myers and Diener, 2018). Such economic contexts should be carefully evaluated and taken into account when developing local housing policies. While residents in Qasr Al-Hallabat would likely chafe against an influx of commercial businesses, those in Ajloun would tend to perceive a happiness benefit associated with policies that facilitate home-based enterprises (e.g., mixed-use zoning and building codes that accommodate the needs of dual-purpose residential and business spaces).

The texture of the local community can have an important effect on the selection of specific design elements to promote happiness and enhance the success of sustainable building. For example, in Qasr Al-Hallabat, housing could emphasize ease of access to ample, centrally located community spaces, with motifs that link such spaces to individual homes. Projects such as solar water heating could more easily take on a shared/community aspect in this neighborhood, thereby benefitting from economies of scale. In Ajloun, family-centric housing could be made sustainable by enhancing household garden spaces and implementing multi-generational housing designs, as well as by adding energy-saving features useful to home businesses, which can be promoted to residents for their economic benefits. By carefully attending to such nuanced local preferences, we can develop housing policies that are not only sustainable but also resonate with emotional and psychological needs. This increases the likelihood of their enthusiastic acceptance and long-term success.

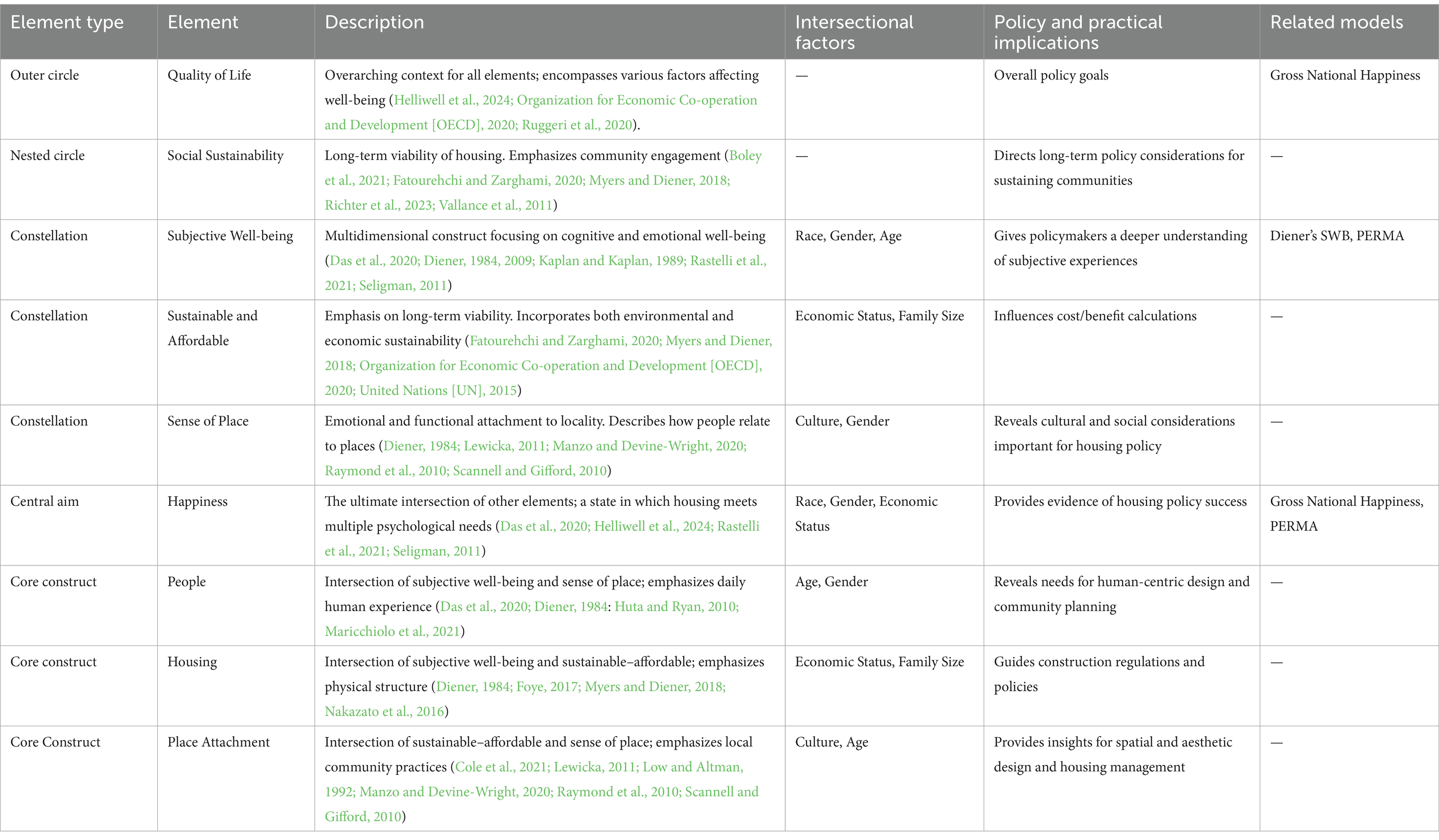

5.1 Expansion and revision of the GROW-J framework

Based on the study findings, we revised the GROW-J framework to introduce more nuance and detail about housing-related happiness factors for our Jordanian participants. This helped to make GROW-J more contextually relevant and empirically grounded (Figure 8 and Table 4). One of the significant changes that we made on the conceptual level was to demote housing from the center of our Venn Diagram and to replace it with happiness as the focal point, aligning with the seminal work of Evans (2003) on the relationship between the built environment and mental health. This shift in focus is further supported by recent studies that emphasize the importance of considering housing as a social determinant of health and well-being (Rolfe et al., 2020) and the impact of housing conditions and indoor environmental quality on mental health outcomes (Riva et al., 2022). These studies highlight the need for a comprehensive approach to understanding the complex interplay between housing, social sustainability, and subjective well-being. This is in accordance with better encapsulating our emphasis on happiness outcomes, but it also was inspired by our findings that housing is only one of the aspects of community development prioritized by the study participants (Seligman, 2011). As the residents that we interviewed, especially in Qasr Al-Hallabat, continually turned their focus toward broader community-based projects, we have accordingly balanced “housing” against the equally important factors of “people” and “place attachment” as contributors to personal happiness (Low and Altman, 1992; Scannell and Gifford, 2010). This slight decentering of housing is important in terms of sustainable development policy, as it should prompt decision-makers in Jordan to recognize that it is important to consider the features of entire neighborhoods, not just individual homes.

Table 4. Elements of the GROW-J framework for evaluating housing happiness in Jordan (refer to Figure 8 for graphical diagram).

In the newly revised framework, based on the conducted analysis, the factors of housing, people, and place attachment are conceptualized as intersections among our original topical areas. Housing is located at the intersection of sustainable/affordable building and subjective well-being. This area indicates the importance of physical structures for happiness outcomes. Our study indicated that Jordanians valued housing that fosters a sense of community and social bonds, incorporates sustainable features like energy-efficient windows and solar hot water tanks, and is proximal to essential services like schools and hospitals. They also expressed a strong preference for homes that allow for the practice of traditional cultural norms, such as hosting relatives and neighbors. These preferences highlight the need for housing solutions that are not just sustainable in an environmental sense but also resonate with the lived experiences and social values of the residents. The significance of cultural factors in shaping environmental behaviors and fostering a deep attachment to place supports the importance of incorporating traditional cultural norms into sustainable housing designs (Al Husban et al., 2021; Qtaishat et al., 2020).

Sustainable and affordable construction must recognize these preferences or risk-producing environments that are technically sustainable but fail to connect with residents emotionally (Abed and Al-Jokhadar, 2021; Adabre et al., 2020; Al Husban et al., 2021; Cole et al., 2021; Obeidat et al., 2022; Qtaishat et al., 2020). For instance, a housing development focusing solely on environmental sustainability without considering the residents’ cultural and social needs could result in low occupancy rates and poor community engagement (Foye, 2017; Nakazato et al., 2016; Qtaishat et al., 2020). Based on the study findings, some central questions to ask local residents when developing new sustainable housing or retrofits some suggestions include, “what communal spaces are important to you for fostering social bonds” and “how important is proximity to essential services like schools, hospitals, and public transportation?” In addition, questions pertaining to sustainable features, asking questions such as, “are there specific sustainable features you would like to see incorporated into the housing design,” “how can the housing design accommodate traditional cultural practices,” and “what are your priorities when it comes to balancing sustainability and affordability?” By asking these questions, developers and policymakers can create housing solutions that are sustainable and affordable and contribute to the residents’ subjective well-being.

The factor of “people” is located at the intersection of sense of place and subjective well-being. It indicates the role of local relationships for happiness outcomes. Our findings indicated that the fabric of these relationships may be quite different among different localities, even within the shared context of low-income Jordanians. Our participants in Ajloun focused primarily on relationships within the family, while those in Qasr Al-Hallabat were more interested in discussing relationships with neighbors as having an impact on their happiness. When creating a sustainable development initiative, decision-makers in Jordan should attend to the particular types of social fabrics that exist in the affected communities, asking questions such as, “who do you need to keep in contact with on a daily/weekly basis” and “what type of social interaction spaces are most important to you?” This can help to inform projects that are designed to assist in maintaining and strengthening such local social ties, contributing to residents’ happiness and buy-in. Such outcomes should extend not only to the features of individual houses, but to the development of local community spaces and the neighborhood urban fabric as a whole.

The factor of “place attachment” is located at the intersection of sense of place and sustainable/affordable building. It indicates the role of connections to the local environment for happiness outcomes. In our current study, the participants’ sense of place was primarily grounded in the people known and activities undertaken there, with relatively little attention paid to the ecological environment or cultural landmarks. The structures most associated with place attachment were community centers and local businesses. This finding should be taken with caution, however, as ecological and cultural features may often come to be taken as an assumed “background” for life, to the extent that does not merit specific note or conscious attention. We did not specifically ask our participants how they would feel if certain existing natural or cultural aspects of their environment were destroyed. Decision-makers should carefully evaluate any such potentially destructive acts of development and carefully solicit feedback from residents before proceeding. At the same time, based on our findings, particular attention should be given in Jordan to the maintenance of the physical touchstones of local life that enhance place attachment, such as community meeting areas, schools, and local restaurants.

Finally, sustainable development projects should attend carefully to intersectional demographic factors (indicated by the red dashed line in Figure 8) that may impact all of the above dimensions. We have noted throughout this section how some of our results differed between the communities of Qasr Al-Hallabat and Ajloun, many of which differences may be related to the specific characteristics of the people who live in these neighborhoods. In addition, sustainable development may affect individuals within the same community in divergent ways depending on factors such as gender or age. When investigating salient issues in local housing preferences, webs of relationship, and place attachment, it is important to consider the voices of residents from many different walks of life, so that the happiness needs of one particular group does not dominate the decision-making process, avoiding a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach.