Abstract

This study navigates the terrain of community development in metropolitan areas across the United States (US), spotlighting the interplay between stakeholder engagement, development success, and distinct types of community development characteristics. While urban centers in US cities experienced disinvestment and urban flight for more than 5 decades, they now experience renewed interest amidst the complexities of rampant urbanization. Gentrification and displacement are some of the critical consequences of urban re-development, which warrants the exploration of the success metrics that turn disinvested communities into thriving ones. Methodologically, archetype analysis is employed to examine 73 case studies reported by the United States Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD) as examples of successful development. The case studies span 37 US states and 67 cities. The analysis utilizes the Distressed Communities Index (DCI) as a supporting metric and offers an intermediate level of abstraction between a case-by-case analysis of successful development strategies and a generalized approach that assumes that one strategy fits all. Instead, the analysis identifies four distinct types of successful community development archetypes based on five relevant characteristics that emerged from our analysis: (1) public investments, (2) private investment (3) development plans, (4) stakeholder engagement, and (5) the DCI. The four identified archetypes represent unique Community Development Success pathways with specific development characteristics. Understanding the diversity reflected in these distinct archetypes is crucial for policymakers and stakeholders seeking to address the specific needs and challenges of each development success type. This can inform more targeted policy initiatives for fostering prosperity and vitality in diverse communities across the US and beyond.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, historically disinvested urban communities (i.e., communities that have received diminishing services and capital throughout an extended time period) have seen significant shifts in their demographics and economic landscapes. The term disinvested communities describes a sadly familiar process in United States urban planning whereby entire neighborhoods or sections of a city were abandon and neglected. Not surprisingly, disinvestment typically falls along racial and class lines (Bradford and Rubinowitz, 1975; Body-Gendrot, 2000; Gibson, 2007; Platt, 2014). More recently, disinvested United States cities have experienced a turnaround from their urban flight and disinvestment past, and are subject to renewed interest along with the complexities of rampant urbanization (Naparstek and Dooley, 1997; Dreier, 2003). Some scholars have called this recent turn around the back-to-the-city moment (Sturtevant and Jung, 2011) and the new urban renewal (Hyra, 2017). While it mirrors global trends of urbanization (Yeolekar-Kadam and Chandiramani, 2024), the United States leads the world in urbanization with more than 80% of United States Americas living in cities and metropolitan areas. Gentrification is one of the downsides of the back-to-the-city moment. Disinvested neighborhoods with low property values are prime candidates for reinvestment. The influx of funding and higher-income residents leads to increased property values, and the displacement, the forced migration of long-time, low-income residents (Hyra, 2017; Moskowitz, 2018).

Yet while the overall urbanization pressures tend to spur local governments and planners to develop disinvested communities where the land values are cheaper (Eastman and Kaeding, 2019), not all urbanization leads to gentrification. Urbanization is driven by many factors that differ due to the unique nuances found in different communities, such as the level of development, economic maturity, the percentage of retirees, employment levels, or school-aged children, recreational assets, climate conditions etc. These factors and more can influence how migration patterns take shape (Boyd, 1989; Wu et al., 2019; Grafeneder-Weissteiner et al., 2020). Some view gentrification pressures as a transition critical to the economic success of urban centers (Logan and Molotch, 2007). Others find displacement a rare phenomenon (Ellen and O’Regan, 2011); while others contend it is prevalent (Newman and Wyly, 2006). Regardless, increased public and private investment in disinvested communities invariably causes an increase in property values, which tends to push out long-time residents. This warrants a further exploration of the role of investments in successful community development outcomes (Hyra, 2017; Rothstein and Rothstein, 2023). Similarly, development plans are important factors that influence development success. There is in fact broad consensus that measuring community development success must be based on clearly defined goals (Chantal et al., 2019). Yet how to arrive at these goals is far less clear. In fact, a range of conventional and unconventional methods exists to formulate development plans and identify both broad and specific measures to track progress toward the identified development goals (Savini, 2021). The engagement of stakeholders in defining both goals and success measures has proven to be an influential factor as well (O’Hara, 1999). Some argue that universal measures are desirable to provide communities with a succinct road map to development success. Others contend that goals and measures must be based on the specific conditions of each local community.

This study aims to explore the space between these two poles and tests the hypothesis that successful community development initiatives are not uniform but show distinct differences. Awareness of these differences constitutes a useful tool for local decision makers while also saving them the time and expenses of developing their own community based development approach. It is therefore all the more important to identify what variations exist so that communities can identify the development path that provides the most promising road map for them. The study explores these varied yet transferrable development paths based on five relevant characteristics that emerged from our analysis: (1) public investments, (2) private investment (3) development plans, (4) stakeholder engagement, and (5) the DCI.

2 Disinvested communities and the role of investment

In the discourse on urban economics and community development, the terminology used to describe community conditions can significantly influence the focus and implications of research and policy initiatives. The literature often uses the deficit-based term “distressed” when addressing these same communities (Shultz et al., 2017; Eastman and Kaeding, 2019; Bartik, 2020). Other studies (see Zuk et al., 2018; Schnake-Mahl et al., 2020), prefers the term “disinvested” over the term “distressed” to describe communities experiencing long-term economic and service decline. Unlike the deficit-focused term “distressed,” which often connotes an inevitable decline, “disinvestment” is an asset-based term that implies a reversible process and focuses on the withdrawal or withholding of investments and services over an extended period of time. This perspective aligns with our research aim to identify and reverse these trends through targeted interventions.

This study further operationalizes the term “disinvestment” by using both empirical data and qualitative assessments. Naparstek and Dooley’s (1997) definition provides a critical foundation for this perspective. They describe disinvestment as “a series of progressive, purposeful steps by lending institutions to withdraw their investment from the communities they expect to deteriorate.” This definition encompasses a broader range of actions than mere economic decline, including the strategic decisions by developers, lenders, and even public sector entities to limit or withdraw financial and infrastructure support from certain areas. These actions contribute not only to economic degradation but also to the erosion of community well-being and the social fabric of the community.

To quantify and analyze the impacts of disinvestment, this study employs the Distressed Communities Index (DCI) developed by the Economic Innovation Group (2020). The DCI provides a robust empirical framework for assessing economic distress across various dimensions, including employment, educational attainment, and housing stability. The index scores zip codes on seven economic indicators, with scores ranging from 0 (most prosperous) to 100 (most distressed), across five tiers of well-being. By integrating DCI data, it is possible to identify communities that are statistically distressed and to examine the correlation between high distress scores and areas historically subjected to disinvestment (Table 1).

Table 1

| Metric | Definition |

|---|---|

| No High School Diploma | Percent of 25-year-old+ population without a high school diploma or equivalent. |

| Housing vacancy rate | Percent of habitable housing that is unoccupied, excluding properties that are for seasonal, recreational, or occasional use. |

| Adults not working | Percent of prime-age (25–54) population not currently employed. |

| Poverty rate | Percent of the population living under the poverty line. |

| Median income Ratio | Median household income as a percent of metro area median household income (or state, for non-metro areas). |

| Change in employment | Percent change in the number of jobs. |

| Change in establishments | Percent change in the number of business establishments. |

Distressed communities index—seven components.

This integration of DCI scores with the conceptual framework of disinvestment allows for a nuanced analysis of how policy and economic decisions impact community vitality. The DCI’s comprehensive scoring system offers a mechanism to track changes over time, providing a way to assess the effectiveness of targeted development initiatives. It also helps to illustrate the broader impact of disinvestment practices, showing how they manifest in tangible economic and social outcomes.

Furthermore, using the DCI in conjunction with our methodological approach offers a dual-lens through which community well-being can be viewed. It highlights areas suffering from acute economic struggles and contextualizes the struggles within a framework of historical and ongoing investment decisions. This makes it possible to both identify the symptoms of community distress and highlight the underlying causes, thereby offering a more comprehensive understanding of the factors driving community distress and offering clearer pathways for policy intervention aimed at reversing negative trends.

3 Participation in development and planning

A review of the literature on urban development and planning indicates that not only the measures of development success are critical but also the engagement of local stakeholders in selecting them. Blanke and Walzer (2013), for example, assert that engagement results in better goals and outcomes measures as well as increased public’s awareness of the issues involved in attaining them. This view is prevalent not only at the community level but also at every level of development. It argues that different stakeholders leave their distinct mark on the selection of indicators to measure development success (O’Hara, 1999). Some in the urban studies field have therefore raised concerns about development approaches that lack local engagement and decimate the economic and social fabric of neighborhoods (Perry, 2020; O’Hara et al., 2023). Others recognize that urban planners and developers may not see sufficient value in investing the time and resources necessary to establish a meaningful local engagement process, especially given the opportunity costs associated with scarce urban resources (Blanke and Walzer, 2013).

Given these tensions between abstracts and generalizable definitions of development and local specificities and engagement-based definitions, the literature provides a range of frameworks for measuring community development that address the need for collective voices and displacement mitigation. Contingent measurement approaches like the Success Measures toolkit created by NeighborWorks America make it possible for community members to select and monitor indicators from performance measures that they identify as priorities (Blanke and Walzer, 2013; Success Measures, 2020). Data on the identified indicators and outcomes are then collected annually to track progress. Scholars like Stoecker (2013) also argue for a contingent measurement approach where each community selects its own indicators that align with its goals.

Yet, some communities do not have a clear vision for their outcomes that can be translated into appropriate success measures. Patton (2011) provides a model for measuring community development success that focuses on examining outcomes when the expected results are unclear. This approach, called the Development Evaluation model, suggests that a more nimble evaluation process that grows and shifts is needed as the community’s vision manifests (Patton, 2011).

While these various approaches provide in principle the opportunity for inclusive community development, local governments, and developers cite cost and time constraints as reasons why they are not leveraging the breadth of research that advocates for a participatory model of development (Blanke and Walzer, 2013). Time and resource constraints are also cited as hurdles that limit the ability of urban planner to facilitate approaches that measure community development outcomes based on goals relevant to each specific community (Walzer and Hamm, 2012).

While both academics and practitioners agree that indicators are important when measuring community development success, the literature is divided on the specific indicators that are most relevant or on the process for selecting them. Generally, engagement is recognized not only as indispensable to developing unique community based development indicators, but also in building capacity and producing more actionable goals. Yet especially for communities with limited resource broad based participation remains a challenge (see for example Zautra et al., 2008). Others, therefore contend that the universal measurement approach is more desirable, and universal indicators are needed to ensure broader development success (see for example Hoffer and Levy, 2010).

In the field of urban planning, stakeholders are organizations, groups, and individuals that can impact, are impacted by, or believe they can influence a project’s design, directions, or outcomes (Project Management Institute, 2021). In development, particularly sustainable development, engaging stakeholders requires a delicate balancing act between economic, environmental, and societal conditions (Rondinel-Oviedo and Schreier-Barreto, 2018; O’Hara et al., 2023). The community development literature suggests that planners, local governments, and developers follow a traditional method of stakeholder engagement (Bhattacharyya, 2004; Hampton et al., 2024).

Traditionally, urban planning within a neighborhood includes a mandatory outreach meeting intended to provide residents with opportunities to engage with planners and government officials regarding a planned development (Villanueva et al., 2017). Yet often, meetings are sparsely attended due to their times, locations, and the community’s belief that elected officials and developers have already brokered backroom deals (Gearin et al., 2023). Some studies have corroborated these perceptions and have found that traditional revitalization practices are often driven by city elites and elected officials who follow a predetermined project agenda shaped by private developers (Villanueva et al., 2017). Community voice that result from community engagement are often marginalized or altogether absent from the development agenda (Matarrita-Cascante and Brennan, 2012; Bahadorestani et al., 2020). Citing resource constraints, even less time-consuming survey approaches to gaging stakeholder opinion have found limited acceptance despite their useful findings (O’Hara, 2001).

The literature notes that scholars have proposed other non-traditional approaches to stakeholder engagement in hopes of increasing the breadth, depth, and equity of community input and participation (O’Hara, 2001; Gearin and Hurt, 2024). The collaborative planning approach is a participation technique used by some urban planners to build community consensus (Berke and Kaiser, 2006). Collaborative planning consists of three stages: pre-plan making, plan making, and plan implementation. These stages work to facilitate inclusive participation, common purpose and problem definition, participant self-education, multiple option testing, consensus decisions, shared implementation, and an informed public. Ultimately, this approach serves to increase community voice and participation, but it may not avoid the pitfalls of traditional approaches to engagement altogether (Berke and Kaiser, 2006).

4 Materials and methods

This study employs archetype analysis as its primary methodological framework. Of particular interest here is the capacity of archetype analysis to structure complex phenomena by identifying recurrent patterns at an intermediate level of abstraction. As defined by Oberlack et al. (2019), archetype analysis systematically explores varied instances of a phenomenon to delineate models that encapsulate the essential mechanisms driving these occurrences under specific conditions. The methodology is therefore particularly adept at capturing the subtleties and variations inherent in complex systems. This makes archetype analysis an ideal approach for examining the multifaceted dynamics of community development.

Archetype analysis allows researchers to move beyond simplistic categorizations and delve into the nuanced interplay between different factors influencing community development (Sietz et al., 2019). In this study, it is used to scrutinize the successful development outcomes of urban communities across the United States, focusing on the role of stakeholder engagement and governance structures and investments. By examining these interactions, the analysis illuminates the continuum between generalized developmental goals and the tailored approaches necessitated by unique community contexts.

Eisenack et al. (2019) provide a four-factor conceptualization of archetypes, which we adapt to frame our investigation:

Nonuniversal: Each archetype represents a specific configuration of characteristics that does not necessarily apply universally but exhibits significant explanatory power within particular contexts.

Building blocks: Archetypes serve as modular components that can be interconnected to construct comprehensive models of phenomena. This modular nature allows for the flexible assembly of archetypes to describe complex and varied cases.

Common vocabulary of attributes: Archetypes are characterized by a shared set of attributes, which facilitates the comparative analysis across different cases and enhances the generalizability of the findings within similar contexts.

Classification of components: Each archetype classifies elements of cases, helping to organize and systematize the attributes observed in different instances of community development.

The application of archetype analysis in this study is geared toward understanding how different models of stakeholder engagement and governance influence community development outcomes along with the role of investment. Given its capacity to integrate both qualitative and quantitative data, and to systematically analyze multidimensional land use patterns, archetype analysis proves invaluable in dissecting the complex, intersectional dynamics present in urban areas across the United States and specifically in disinvested urban communities. Archetype analysis can therefore highlights the distinct pathways through which urban communities can achieve development success while also offering insights into how specific combinations of factors contribute to successful urban development outcomes.

4.1 Case studies and cluster analysis

The case studies for our archetype analysis were retrieved from the database of development success stories of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and its Office of Policy Development and Research (PD&R) (see for example Seawright and Gerring, 2008). This is the largest database of detailed urban development case studies in the United States as HUD also contributes the bulk of public funding for urban development (HUD, 2024). It must be stressed that all of the cases in this database are considered “successful” to varying degrees and all of them are considered disinvested to varying degrees as indicated by their DCI.

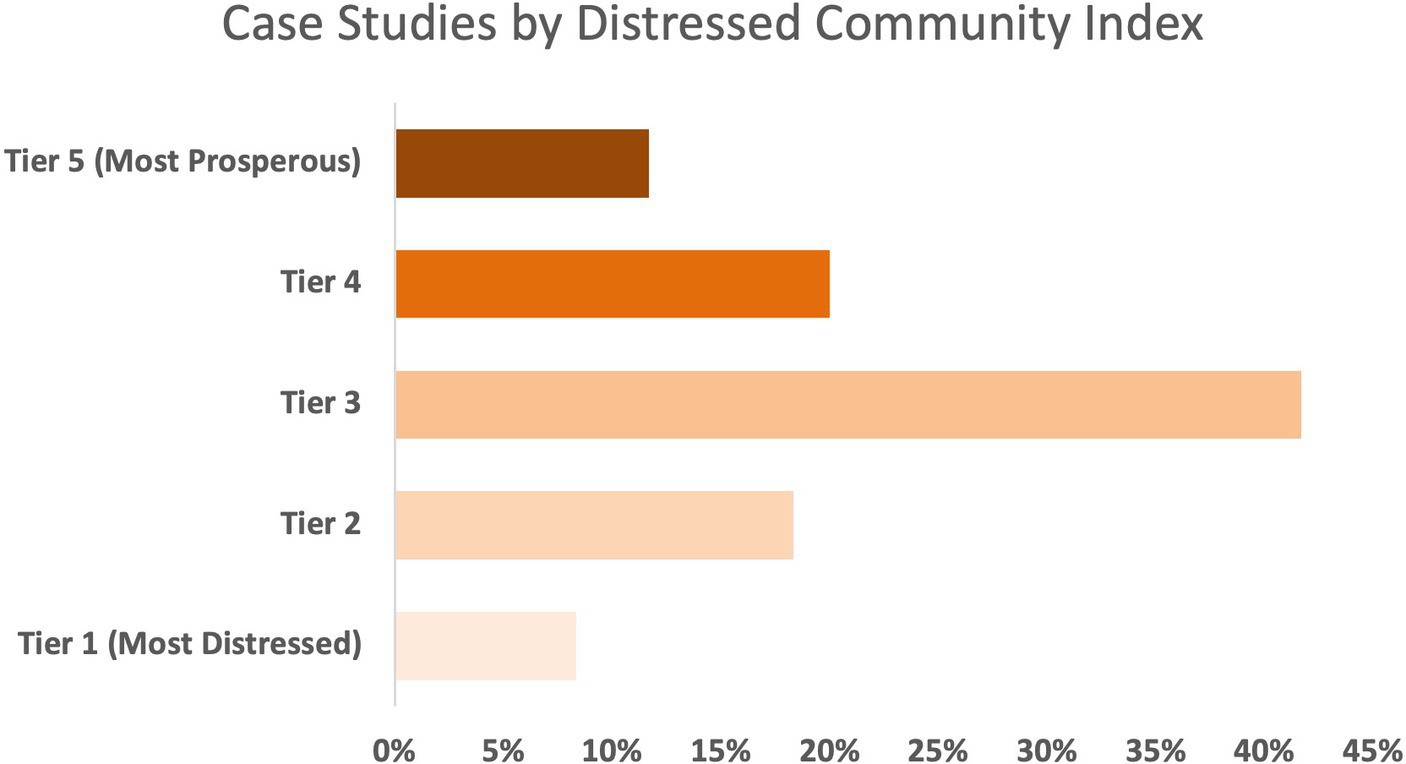

We used the keywords “engagement OR stakeholder engagement” AND “economic OR business” AND “governance OR decision-making OR capacity” to assemble the case studies ultimately included in our study. Case studies were drawn from a wide range of cities across the United States and from across the DCI spectrum (see Figure 1). We further established inclusion criteria first to the case study titles and then to the full case study texts. These inclusion criteria specified that cases had to include information about the structures, processes, and outcomes and provide an indication of decision-making and stakeholder engagement. This procedure yielded 73 case studies across 37 states and 67 cities in the United States. However, detailed information about the selection process of the stakeholders or their specify demographic characteristics was inconsistent across the HUD database.

Figure 1

Case studies by distressed community index.

The qualitative case studies were coded using a thematic analysis methodology (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Corbin and Strauss, 2007), which was then employed to analyze our dataset of 73 diverse case studies. This qualitative approach was chosen for its systematic yet flexible framework for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within the data. Each case study was meticulously examined, with the data undergoing a detailed coding process in an iterative manner. This process involved several stages: initial coding of data by identifying significant features and organizing data relevant to each code; subsequent searching for themes by collating these codes into potential themes; and final review and refinement of themes. Throughout this process, the constant comparative method was integral and ensured that each piece of data was continually compared with others for similarities and differences. Five key themes emerged from the data variables as characteristics of our development success case studies: private investment, government investment, development plans, indicators, and stakeholder engagement. These five characteristics formed the basis for generating binary data, indicative of the presence or absence of these identified themes in each case study.

Following the thematic analysis, principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to the binary data derived from the case studies. This statistical technique reduced the dimensionality of the data while preserving most of the variation within it. The PCA transformed the binary variables into a set of principal components: orthogonal, uncorrelated linear combinations of the original variables. Each PC represented a specific pattern in the data, capturing the maximum variance possible. This step was crucial for identifying underlying structures in the dataset that might not be immediately obvious, and for preparing the data for subsequent clustering analysis.

Finally, a K-means cluster analysis (MacQueen, 1967) was conducted on the transformed data. K-means is a widely used partitioning method that divides data into k distinct, non-overlapping subgroups or clusters. The number of clusters, k = 4, was determined based on the elbow method, which involves plotting the explained variation as a function of the number of clusters and identifying the point where the rate of decrease sharply changes. Each case study was assigned to the cluster with the nearest mean, with the algorithm iteratively optimizing the positions of the cluster centers. The goal of this analysis was to group case studies into clusters based on similarities in their principal components, which reflected underlying patterns identified in the Thematic Analysis and PCA stages. This clustering provided insights into categorizing case studies with similar thematic characteristics, aiding in further interpretation and understanding of the complex dataset.

The methodological approach—specifically the combination of thematic analysis, PCA, and cluster analysis—was specifically designed to reflect our research objectives. By categorizing case studies into distinct clusters, we were able to delineate clear patterns of successful community development efforts. Each cluster represents different strategies and outcomes, providing nuanced insights into how various combinations of investment, planning, and stakeholder engagement correlate with successful community development. The clustering of our case studies not only enhanced our understanding of effective development strategies, but also offers a methodological blueprint for assessing distinct community development pathways in varied urban settings.

5 Results and discussion

The five variables that capture a range of relevant characteristics of the successful development cases we retrieved from the HUD database are consistent with existing frameworks for identifying redevelopment efforts in distressed communities. They are (1) private investment, (2) government/public investment, (3) development plans, (4) development indicators, and (5) stakeholder engagement. The Distressed Community Index (DCI) is leveraged as a contextualizing component of our analysis, as it provides a standardized, comparative measure of economic well-being, offering insights into each community’s relative standing among its peers.

Additionally, the thematic analysis of the case studies reveals five distinct topics (see Table 2); each representing a theme associated with successful community development initiatives in the United States. This, along with case study coding, allows the analysis to move beyond an interpretation of binary attribute configurations to a dynamic examination of the clusters. The interplay between private and government investment, development plans, stakeholder engagement, and the DCI provides a novel view of the group characteristics in each cluster. Overall, the cases in our sample rank between a Tier 1 and 5 community in the development nomenclature.

Table 2

| Themes | Description | Examples in cases |

|---|---|---|

| Private investment | Identifies the origin or type of private investment. | Local businesses, multinational corporations, private equity, and venture capital. |

| Quantifies or describes the extent of private investment. | Large-scale investments, small to medium enterprise support. | |

| Observations or descriptions of the effects of private investment. | Job creation, technology transfer, and market expansion. | |

| Government investment | Differentiates various forms of government investment. | Infrastructure projects, educational funding, and healthcare services. |

| Relates to policies or frameworks guiding government investment. | Economic policies, development agendas, and regulatory environments. | |

| Effects or outcomes of government investment. | Social welfare improvement, economic growth, and public sector development. | |

| Development plans | Extent and coverage of development plans. | Regional plans, sector-specific plans, and long-term strategies. |

| Goals or targets of development plans. | Sustainable development, poverty reduction, and urban renewal. | |

| Processes or actions taken to execute development plans. | Project initiation, stakeholder collaboration, and resource allocation. | |

| Indicators | Metrics related to community well-being and development. | Local data intermediaries working in the community development initiative. |

| Agreed measures of development. | Transformational plans based in data, qualitative and quantitative. | |

| Data collected to identify places of investment. | Projections, models, or reports that provide baselines. | |

| Stakeholder engagement | Identifies different stakeholders involved or affected. | Local communities, government entities, and private sector players. |

| Types and depth of stakeholder engagement. | Consultative meetings, partnerships, and community involvement. | |

| Outcomes or effects of engaging stakeholders. | Policy influence, conflict resolution, and increased transparency. |

Themes of successful community development case studies.

Our archetype cluster analysis revealed four distinct archetypes of successful urban development. Each archetype represents a unique combination of attributes that supports its classification as a distinct Community Development Success Types (CDST). It is important to recognize that the four archetypes are not universal but serve instead as unique snapshots of a dynamic urban development landscape. Understanding the characteristics of each archetype and the development strategies they represent is crucial for designing tailored strategies toward fostering prosperous and vibrant urban communities. Each of the four identified CDSTs suggests different community development strategies underlying their successful development outcome. The distinctive characteristics captured in the four clusters are summarized in Table 3. The characteristics illuminate the strengths of the archetype analysis approach in identifying compelling insights for policymakers, planners, and researchers alike. The results suggest four distinct types of development success rather than one overarching type. The cluster analysis approach thus reveals distinct groupings of successful development cases that overcome the limitations of analyzing every case as its own distinct development strategy. Communities can then consult the four clusters based on their own characteristics to identify their most promising development pathway.

Table 3

| Cluster number | Cluster title | Characteristics | DCI tier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | The Proactive Innovation CDST |

| Tier 5 |

| Cluster 2 | The Harmony Seeking CDST |

| Tier 3–4 |

| Cluster 3 | The Opportunity Optimist CDST |

| Tier 2 |

| Cluster 4 | The Adaptive Progressive CDST |

| Tier 1–2 |

Cluster interpretation.

5.1 Cluster description and interpretation

5.1.1 Cluster 1: the Proactive Innovation CDST

This cluster in characterized by both private and public sector investments, indicating a strong commitment to economic development from both stakeholder groups. This archetype captures community development with a high level of both private and government investment, identified indicators, development plans, stakeholder engagement, and advanced DCI scores. Cases in this cluster are proactive in planning their development, as evidenced by their extensive development plans. Moreover, they actively engage with stakeholders, emphasizing the collaborative nature of their development initiatives. They enhance the efficacy of community development initiatives by leveraging social capital generated through extensive stakeholder engagement.

Reflecting on the thematic characteristics, this cluster aligns with themes of integrated development strategies and effective governance structures, showing a clear convergence with patterns of high stakeholder collaboration and advanced DCI scores, indicative of higher economic prosperity. This suggests a relatively high level of prosperity classified as Tier 5 regions. Areas that reflect these attributes actively seek new opportunities to both leverage and increase their assets while systematically targeting areas for improvement. The score reflects the relatively advanced development status of the communities in this cluster compared to communities that score significantly lower on the DCI index.

5.1.2 Cluster 2: the Harmony Seeking CDST

This cluster shows moderate levels of private and government investment. It is not common to see investment from both private and government in the community development initiatives captured in this cluster. Cases in this cluster have indicators and development plans, demonstrating a proactive approach to economic development. This cluster diverges from the common narrative of identifying high levels of engagement with development success. Instead, the cases in this cluster suggest a more nuanced interaction between engagement and development success as well as investment and engagement quality. The characteristics of communities in this cluster are supported by DCI scores, which reflect a balanced state of economic development as most cases in this cluster typically fall into Tier 3 or 4 of the DCI, indicating intermediate development.

This cluster reflects communities that seek to strike a balance between investment and development. They exhibit a harmony between private and government investment, a diverse range of development plans, and moderate DCI scores that correspond to Tier 3 or 4 classifications. These cases indicate the effectiveness of maintaining equilibrium in community development initiatives and of resisting the inclination to overemphasize one aspect at the expense of another, which might result from an tendency to run after to money, and aggressively seek private or public sector funding without sufficient readiness in other areas needed for development success.

5.1.3 Cluster 3: the Opportunity Optimist CDST

This cluster is characterized by both private and public sector investment, signifying that some development resources have been leveraged. Communities in this cluster have development plans, indicators, and varying levels of stakeholder engagement. Despite the DCI scores, which reveal a significantly higher level of disinvestment than the previous two clusters, the Opportunity Optimists have shaped the economic status of their communities through rather detailed reinvestments. This cluster illustrates a clear pattern of leveraging both existing and new resources to kickstart development, and aligning it with thematic findings of resource mobilization for revitalization. This archetype is also characterized by inconsistent stakeholder engagement, which may limit the scale and scope of development.

While the cases in cluster 3 are categorized as successful examples of community development in the HUD database from which we draw our case studies, their modest DCI scores position them in Tier 2 of the DCI. This suggests that there is considerable room for improvement. The untapped potential may lie in the stronger collaborative investment of the public and private sectors to accelerate community development initiatives. A visionary private sector champion may also be an effective catalyst for the development of communities in this cluster.

5.1.4 Cluster 4: the Adaptive Progressive CDST

Communities in this cluster have development plans, indicators, and varying stakeholder engagement levels but only minimal private and public sector investments. Most cases in this cluster are classified as Tier 1 or 2 DCI cases. These comparatively low scores are characteristic of the current state of the communities in this cluster even though they were characterized as development successes in the databases from which we drew our case study samples. It is remarkable that community development success is possible at all for these cases given their low DCI scores, which indicate low to moderate economic development potential.

This finding diverges from other clusters where higher investments correlate with greater development success, which makes this archetype of communities particularly interesting. It highlights the potential for achieving significant development success even with limited resources. This archetype appears to be adapted to navigating development in the specific economic contexts where the communities in this cluster find themselves and illustrates the need for adaptive strategies that consider both investment levels and development plans. However, the need to adapt to diverse economic contexts may lead to a dispersion of resources and efforts, which potentially dilutes the impact of development initiatives.

The results of our analysis of the development success of disinvested urban communities, taking into account the five characteristics of private investment, government investment, development indicators, development plans, and stakeholder engagement, provide valuable insights into the complexities of community development. By exploring the multifaceted interplay between our attributes for community development success and the DCI, we can contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the community development landscape and facilitate more effective data-driven decision-making for the benefit of the diverse communities in need of a successful development strategy.

5.2 Policy implications

Our analysis has direct policy implications. Communities falling within the identified four archetypes face different challenges and opportunities in achieving development success. For The Proactive Innovator types, it will be critical to identify continued support for their robust development plans and stakeholder engagement strategies. Communities with the characteristics of this development archetype can develop and implement policy frameworks that encourage ongoing public and private partnerships and ensure that these collaborations are sustainable and adaptable to changing economic conditions. These communities might establish incentives for continued private investment in urban infrastructure and social programs that are well-aligned with community development goals; they might also create enhanced platforms for stakeholder engagement to ensure that development plans continuously reflect community needs and priorities. Communities characterized by this archetype can serve as models for comprehensive development initiatives, albeit they may be considered relatively resource intensive.

The Harmony Seekers appear to have the ability to adapt and strike a balance between investment and development efforts. This archetype should be encouraged to maintain its balanced approach, and to ensure that its investment remains well-aligned with identified development strategies. Communities that identify with this archetype should focus on creating balanced development programs that promote equal participation from both private investors and public entities. Additionally, community workshops and forums can elevate the level of stakeholder engagement and ensure that all voices are represented in development discussions. Communities characterized by this archetype may also find it helpful to introduce rigorous monitoring and evaluation frameworks to assess the impact of development projects and adjust strategies as needed to maintain the balance they strive for.

The Opportunity Optimists will require policies that can effectively leverage their high private sector investment, channeling it effectively to realize the development potential of the communities falling within this cluster. Through the development of targeted engagement initiatives that aim to involve underrepresented community members in the planning processes, they can enhance the impact of the investments characteristic of this archetype. Communities identified with this archetype might also strengthen public-private partnerships as a mechanism to boost economic development and infrastructure improvements, while designing innovative resource allocation models that prioritize investments in critical areas especially those identified by underrepresented stakeholders.

The Adaptive Progressors would be well advised to consider adaptive strategies that match their specific economic contexts, recognizing that investment and development plans need to align with their current limited capacity. Other strategies might include support for community-led planning initiatives that empower residents to direct development efforts toward their specific needs, and to focus on the efficient utilization of limited resource to ensure that even small investments are maximized to benefit community development goals. This may not be an easy lesson to implement as it may require prioritizing specific development initiatives that avert a dispersion of resources and efforts and make selected initiatives more impactful.

Overall, our results offers valuable insights for development decision makers and policymakers and underscores that the development success of disinvested urban communities cannot readily be captured in a single success strategy. As the example of our Adaptive Progressor archetype illustrates, the practical application of these findings and their implementation in diverse and complex political environments may present challenges. However, these challenges may be mitigated by a more nuanced understanding of the development paths captured in the identified archetypes of successful urban development.

5.3 Study limitations

Our study provides a novel and nuanced examination of community development in disinvested United States cities. However, several limitations must be noted. Chiefly, the source of case studies is the US Department of Housing & Urban Development database of development success stories. While the data provides a wide range of DCI tiers suggesting a range of more and less successful development outcomes, the data does not include the full range of development outcomes, including those initiatives that were not successful. This study can, therefore, be considered a steppingstone for future exploration. Given the lack of undecided or negative development outcomes, the four archetypes of development identified in this study may paint a somewhat optimistic picture. Communities can also exhibit characteristics that span multiple archetypes or shift from one type to another over time. These limitations highlight areas for further research and suggest caution in applying the study’s findings universally without considering specific local contexts and evolving community dynamics in the disinvested communities undertaking development initiatives.

5.4 Future research directions

The study identifies several avenues for further research: (1) exploring the factors that influence stakeholder engagement and how it relates to economic development; (2) investigating the effectiveness of various development plan models and their impact on economic development; (3) assessing the role of policy interventions in fostering private and public sector investment within specific archetypes and policy environments; and (4) longitudinal studies to understand how communities may transition between archetypes over time, reflecting the dynamic nature of regional economic and community development. Further explorations of these topics will undoubtedly make the identified archetypes of urban development more robust even as their specific characteristics already provide useful insights.

6 Conclusion

This study analyzed 73 case studies from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development database, and identified four distinct archetypes of successful urban community development. We were able to discern our four unique clusters of development archetypes by delineating five distinct development characteristics within our data. Each cluster represents an archetype that exemplifies a successful development approach, offering a novel and insightful perspective into the multifaceted community development landscapes across the United States and possibly to communities beyond.

Archetype analysis as a methodological approach enabled us to understand recurrent patterns of variables and processes, which facilitated a deeper investigation into patterns of community development success across a diverse array of urban contexts captured in our case studies. Observing outcomes and stakeholder engagement processes at an intermediate level of abstraction allowed us to distinctly identify four archetypes of Community Development Success Types (CDSTs): the Proactive Innovation CDST—characterized by high investment and active stakeholder engagement; the Harmony Seeking CDST—noted for its balanced approach to investment and development; the Opportunity Optimist CDST—which leverages both public and private investments under conditions of significant historical disinvestment; and the Adaptive Progressive CDST—characterized by success despite minimal investments under economically challenging conditions.

These four archetypes provide a robust foundation for formulating targeted and effective policy initiatives, strategic resource allocation, and promising development strategies that can be more finely tuned to the unique characteristics of each archetype to utilize community resources to their fullest potential.

Recognizing the diversity represented by our four archetypes is essential for policymakers and stakeholders who are tasked with leveraging CDSTs to address a community’s specific needs and opportunities. The value of these CDSTs extends beyond mere classification; they serve as a strategic guide for decision-makers to tailor interventions that resonate with the underlying dynamics of each community. By gaining a deeper understanding of the DNA of each archetype, policymakers and planners are equipped to craft initiatives that leverage existing strengths, address vulnerabilities, and capitalize on growth opportunities. This targeted approach optimizes resource utilization and enhances the effectiveness of the development strategies themselves resulting in more equitable and sustainable urban development outcomes overall.

The implementation of tailored strategies based on our findings is pivotal for driving meaningful change especially in significantly disinvested communities who may not easily see a path forward toward sustainable development and prosperity. Policymakers and stakeholders, armed with a deeper understanding provided by this study, are better equipped to navigate the complexities of community development. Moreover, the refinement and adaptation of policies based on the ongoing assessments and further refinement of the identified archetypes will be instrumental in improving development outcomes, especially for under-resourced communities. Our study lays the groundwork for a strategic and proactive stance in community development that can guide stakeholders toward pathways that help all communities to thrive, adapt, and collectively contribute to a more sustainable and just development future.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SO’H: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Klaus Eisenack for his ideation, technical expertise, and assistance with our study’s archetype analysis methodology, and Lauren Hampton for her editing and proofreading support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2024.1408673/full#supplementary-material

References

1

BahadorestaniA.NaderpajouhN.SadiqR. (2020). Planning for sustainable stakeholder engagement based on the assessment of conflicting interests in projects. J. Clean. Prod.242:118402. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118402

2

BartikT. J. (2020). Using place-based jobs policies to help distressed communities. J. Econ. Perspect.34, 99–127. doi: 10.1257/jep.34.3.99

3

BerkeP.KaiserE. J. (Eds.) (2006). Urban Land Use Planning. 5th Edn, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

4

BhattacharyyaJ. (2004). Theorizing community development. Commun. Dev. Soc. J.34, 5–34. doi: 10.1080/15575330409490110

5

BlankeA. S.WalzerN. (2013). Measuring community development: what have we learned?Community Dev.44, 534–550. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2013.852595

6

Body-GendrotS. (2000). Social Control of Cities. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

7

BoydM. (1989). Family and personal networks in international migration: recent developments and new agendas. Int. Migr. Rev.23, 638–670. doi: 10.2307/2546433

8

BradfordC. P.RubinowitzL. S. (1975). The urban-suburban investment-disinvestment process: consequences for older neighborhoods. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci.422, 77–86. doi: 10.1177/000271627542200108

9

BraunV.ClarkeV. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol.3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

10

ChantalS.de BloisM.HambergR.BaldwinJ. (2019). Community indicators project development guide: Independently published.

11

CorbinJ. M.StraussA. L. (2007). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 3rd Edn: Sage Publ.

12

DreierP. (2003). The future of community reinvestment: challenges and opportunities in a changing environment. J. Am. Plan. Assoc.69, 341–353. doi: 10.1080/01944360308976323

13

EastmanS.KaedingN. (2019). Opportunity zones: what we know and what we Don’t. Tax foundation. Available at: https://taxfoundation.org/opportunity-zones-what-we-know-and-what-we-dont/

14

Economic Innovation Group (2020). The Spaces Between Us: The Evolution of American Communities in the New Century (p. 42). Available at: https://eig.org/dci

15

EisenackK.Villamayor-TomasS.EpsteinG.KimmichC.MaglioccaN.Manuel-NavarreteD.et al. (2019). Design and quality criteria for archetype analysis. Ecol. Soc.24:art6. doi: 10.5751/ES-10855-240306

16

EllenI. G.O’ReganK. M. (2011). How low income neighborhoods change: entry, exit, and enhancement. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ.41, 89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2010.12.005

17

GearinE.DunsonK.HamptonM.NeuhausF.RobertsonN. (2023). Greened out: mitigating the impacts of eco-gentrification through community dialogue. Architect. MPS25. doi: 10.14324/111.444.amps.2023v25i1.002

18

GearinE.HurtC. S. (2024). Making space: a new way for community engagement in the urban planning process. Sustain. For.16:2039. doi: 10.3390/su16052039

19

GibsonK. J. (2007). Bleeding Albina: a history of community disinvestment, 1940-2000. Transform. Anthropol.15, 3–25. doi: 10.1525/tran.2007.15.1.03

20

Grafeneder-WeissteinerT.PrettnerK.SüdekumJ. (2020). Three Pillars of Urbanization: Migration, Aging, and Growth. De Economist168, 259–278. doi: 10.1007/s10645-020-09356-z

21

HamptonM.O’HaraS.GearinE. (2024). Assessing restorative community development frameworks—a Meso-level and Micro-level integrated approach. Sustain. For.16:2061. doi: 10.3390/su16052061

22

HofferD.LevyM. (2010). Measuring Community Wealth, Wealth Creation in Rural Communities43.

23

HUD (2024). Housing and Urban Development. “Case Studies.”Office of Policy Development and Research, Available at:https://www.huduser.gov/portal/casestudies/home.html (Accessed 1 Feb. 2024).

24

HyraD. S. (2017). Race, class, and politics in the Cappuccino City, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

25

LoganJ. R.MolotchH. L. (2007). Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy of Place (20th Anniversary ed. With a New Preface), California: University of California press.

26

MacQueenJ. (1967). “Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations” in Proceedings of the 5th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability 1, 281–297.

27

Matarrita-CascanteD.BrennanM. A. (2012). Conceptualizing community development in the twenty-first century. Community Dev.43, 293–305. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2011.593267

28

MoskowitzP. E. (2018). How to Kill a City: Gentrification, Inequality, and the Fight for the Neighborhood.

29

NaparstekA. J.DooleyD. (1997). Countering urban disinvestment through community-building initiatives. Soc. Work42, 506–514. doi: 10.1093/sw/42.5.506

30

NewmanK.WylyE. K. (2006). The right to stay put, revisited: gentrification and resistance to displacement in new York City. Urban Stud.43, 23–57. doi: 10.1080/00420980500388710

31

O’HaraS. (1999). Economics, ecology and quality of life: who evaluates?Fem. Econ.5, 83–89. doi: 10.1080/135457099337969

32

O’HaraS. (2001). Urban development revisited: the role of neighborhood needs and local participation in urban revitalization. Rev. Soc. Econ.59, 23–43. doi: 10.1080/00346760110036265

33

O’HaraS.AhmadiG.HamptonM.DunsonK. (2023). Telling our story—a community-based Meso-level approach to sustainable community development. Sustain. For.15:5795. doi: 10.3390/su15075795

34

OberlackC.SietzD.Bürgi BonanomiE.de BremondA.Dell’AngeloJ.EisenackK.et al. (2019). Archetype analysis in sustainability research: meanings, motivations, and evidence-based policy making. Ecol. Soc.24:art26. doi: 10.5751/ES-10747-240226

35

PattonM. Q. (2011). Developmental Evaluation: Applying Complexity Concepts to Enhance Innovation and Use, New York: Guilford Press.

36

PerryA. M. (2020). Know Your Price: Valuing Black Lives and Property in America’s Black Cities, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

37

PlattR. H. (2014). Reclaiming American Cities: the Struggle for People, Place, and Nature Since 1900, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press.

38

Project Management Institute (Ed.) (2021). The Standard for Project Management and a Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide). 7th Edn. Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute, Inc.

39

Rondinel-OviedoD. R.Schreier-BarretoC. (2018). “Methodology for selection of sustainability criteria: a case of social housing in Peru” in The Palgrave Handbook of Sustainability. eds. BrinkmannR.GarrenS. J. (New York: Springer International Publishing), 385–409.

40

RothsteinR.RothsteinL. (2023). Just Action: How to Challenge Segregation Enacted Under the Color of Law. 1st Edn. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company.

41

SaviniF. (2021). Towards an urban degrowth: habitability, finity and polycentric autonomism. Environ. Plan. A. Econ. Space53, 1076–1095. doi: 10.1177/0308518X20981391

42

Schnake-MahlA. S.JahnJ. L.SubramanianS. V.WatersM. C.ArcayaM. (2020). Gentrification, neighborhood change, and population health: a systematic review. J. Urban Health97, 1–25. doi: 10.1007/s11524-019-00400-1

43

SeawrightJ.GerringJ. (2008). Case selection techniques in case study research: a menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Polit. Res. Q.61, 294–308. doi: 10.1177/1065912907313077

44

ShultzC. J.RahtzD. R.SirgyM. J. (2017). Distinguishing Flourishing from Distressed Communities: Vulnerability, Resilience and a Systemic Framework to Facilitate Well-Being. In. Handbook of Community Well-Being Research, Eds. PhillipsR.WongC. (pp. 403–421). Springer Netherlands. doi: 10.1007/978-94-024-0878-2_21

45

SietzD.FreyU.RoggeroM.GongY.MaglioccaN.TanR.et al. (2019). Archetype analysis in sustainability research: methodological portfolio and analytical frontiers. Ecol. Soc.24:art34. doi: 10.5751/ES-11103-240334

46

StoeckerR. (2013). Research Methods for Community Change: A Project-Based Approach, New York: SAGE Publications, Inc.

47

SturtevantL. A.JungY. J. (2011). Examining residential mobility in the Washington, DC metropolitan area: Are we moving back to the city?Growth Chang.42, 48–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2257.2010.00543.x

48

Success Measures (2020). Measurement tools | success measures at NeighborWorks America. Available at: https://successmeasures.org/measurement-tools

49

VillanuevaG.GonzalezC.SonM.MorenoE.LiuW.Ball-RokeachS. (2017). Bringing local voices into community revitalization: engaged communication research in urban planning. J. Appl. Commun. Res.45, 474–494. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2017.1382711

50

WalzerN.HammG. (2012). Community Visioning Programs: Processes and Outcomes, New York: Routledge.

51

WuW.ZhaoS.HenebryG. M. (2019). Drivers of urban expansion over the past three decades: a comparative study of Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang. Environ. Monit. Assess.191:34. doi: 10.1007/s10661-018-7151-z

52

Yeolekar-KadamB.ChandiramaniJ. (2024). Analysing the potential of Neighbourhoods in sustainable development: a systematic review of interventions. Environ. Urban. ASIA15, 121–140. doi: 10.1177/09754253241233806

53

ZautraA.HallJ.MurrayK. (2008). Community development and community resilience: an integrative approach. Community Dev.39, 130–147. doi: 10.1080/15575330809489673

54

ZukM.BierbaumA. H.ChappleK.GorskaK.Loukaitou-SiderisA. (2018). Gentrification, displacement, and the role of public investment. J. Plan. Lit.33, 31–44. doi: 10.1177/0885412217716439

Summary

Keywords

community development, governance, stakeholder engagement, urban planning, sustainability

Citation

Hampton M and O’Hara S (2024) Prosperity in progress: a new look at archetypes of successful community development. Front. Sustain. Cities 6:1408673. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2024.1408673

Received

28 March 2024

Accepted

10 June 2024

Published

19 June 2024

Volume

6 - 2024

Edited by

Agatino Rizzo, Luleå University of Technology, Sweden

Reviewed by

Thulisile Ncamsile Mphambukeli, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

Lorenzo De Vidovich, University of Trieste, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Hampton and O’Hara.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Midas Hampton, midas.hampton@udc.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.