- 1Department of Urban Studies, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden

- 2The Swedish Knowledge Center for Public Transport, Lund, Sweden

- 3Institute of Urban Research, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden

Sweden is a country with an international reputation for gender equality. The political goal of gender equality is based on feminist analysis of what constitutes a just society according to gender and the fight against patriarchal norms. Despite policy recommendations and legislation that counteract discrimination against women, women still fear traveling by public transport and being out in the evenings. This indicates that Swedish society still has patriarchal norms to deal with. The article is based on qualitative interviews and data retrieved from the Swedish National Statistics, SCB. The interviews explored mobility practices and strategies, experiences with different modes of transport, and reliability, affordability, and comfort of the mobility options available. The results shows that travel choices for women are affected by their concerns about safety and related necessary adaptation to situations identified as threatening. Despite the “mythical mantra” of the gender equal society, Sweden share the patriarchal norms with other countries, that delimits women's use and access to public space and public transport.

1 Introduction

Women's mobility in public spaces has always been surrounded by norms of respectability (Wilson, 1992; Koskela, 1997), where women and men have had very different access to mobility, travel, and public space (Sheller, 2006). Claiming women's right to the city (Fenster, 2005; Nelischer, 2018), public space, and the freedom to move (Law, 1999; Hanson, 2010; Scholten et al., 2012) has been important feminist battlefields to ensure accessibility to important everyday destinations and the right to use and stay in public space, and also to acknowledge that trips and journeys are made in togetherness, sometimes including children, prams, grocery bags, or other dependent relatives. The journey is not always performed by independent, high-functional “atoms” without social responsibilities, social bonds, or relations who can move freely in the transport system (Friberg et al., 2004; Scholten and Jönsson, 2010).

Sweden has a well-recognized “mythical mantra” for being one of the most gender-equal countries in the world (Martinsson and Griffin, 2016, p. 3). This goes back to the development of the Swedish welfare state model (Esping-Andersen, 1990). The mantra and storytelling of the gender-equal feminist Sweden are kept alive by institutions monitoring gender equality, such as the European Institute for Gender Equality, EIGE, where Sweden scored 82.2 out of 100 in 2023 (https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2023/country/SE).

Much has been written about the Swedish gender equality policy where feminist and post-colonial criticism of the Swedish state feminism have revealed how the policy is constructing heteronormative and racialized subjects and how it is producing discriminatory practices (Magnusson et al., 2008; Melby et al., 2008; Martinsson and Griffin, 2016). Keeping the post-colonial feminist criticism in mind, the Swedish gender equality policy nonetheless continues to create success stories, and the Bureau of National Statistics (SCB) is an important resource in the work for gender mainstreaming. Gender mainstreaming was employed as a method in 1995 by the Swedish government to ensure that all policy areas in Sweden are implementing gender equality (https://swedishgenderequalityagency.se). This applies to the transport policy as well. The national transport policy objective states that:

“The objective of transport policy is to ensure the economically efficient and sustainable provision of transport services for people and business throughout the country.” The overall objective is divided into sub-goals, in which gender equality is specifically mentioned: “...The transport system will be gender equal, meeting the transport needs of both women and men equally.” (Transport Analysis Follow-up of Transport Policy Objectives, 2014:5, p, 4).

Understanding today's society without addressing mobility is not possible (Sheller and Urry, 2006). The concept of mobility adds dimensions to the conventional understanding of transportation and has put people's and artifacts' movements in space into the context of physical and digital flows that organize societies today in a profoundly different way compared with the digital era before (Castells and Cardoso, 2006). Turning to mobility when investigating the meaning of transport contributes to the combination of digital services, which has become part of how accessibility is being understood while at the same time acknowledging the importance of accessibility through different modes of transportation. The combination of the “fixed,” the “fluid,” the “spatial,” and the “digital” when analyzing accessibility and everyday transportation can help to reveal the multi-layered power structures women and men must be able to maneuver to be able to move around. It is in relation to these multi-layered structures that the relationship between gender equality and the transport system becomes important. Urban planning after WWII mainly focused on private cars, with the result of urban sprawl and heavy investments in automobile infrastructures. At the same time, public transportation has been devalued and underdeveloped (Schiller and Kenworthy, 2017). Road space has been taken from sustainable modes of transport, e.g., bicycling and walking, and turned active modes of transport into a hazardous practice for those who must use an active mode of transport or those challenging the norm of the car society by biking and walking (Koglin and Rye, 2014). The negative externalities from traffic are an unproportional burden for low-income households and non-car users (Litman, 1996). Still, everyday life requires transportation to reach opportunities and important destinations (Urry, 2000; Lucas, 2004; Scholten and Joelsson, 2019; Henriksson and Lindkvist, 2020). The zoning of urban land due to car-oriented planning forces people to transport themselves and dependent relatives over longer and longer geographical distances. The cost of bridging home, school, work, and shopping is increasing, and the accessibility to reach these destinations is dependent on where services are located, the opening hours of services, and how the price and fares on the public transport system are set. When societies are built for highly mobile individuals, and less consideration is taken to the distributions of services regarding restrictions due to gender, income, and place of residency, then it is indeed an issue of justice and equity (Lucas et al., 2016; Martens, 2016; Bondemark et al., 2021).

Investigating the Swedish National Statistics (SCB) on women and men indicates the disparities between those acknowledging themselves as women and those acknowledging themselves as men. According to the figures in the national travel survey, the discrepancy between the sexes is small. Women and men have about the same distance to the main destinations (work and school), and they spend almost the same amount of time traveling despite the fact that men conduct more distant travels. This indicates that men use faster modes of transport, e.g., car, train, or flights (https://www.trafa.se/kommunikationsvanor/RVU-Sverige/). However, according to statistics concerning environmental issues, women, especially elder women, are more concerned about climate change (Smidfelt Rosqvist, 2019; Kollektivtrafikbarometern 2022 Kvinnors och mäns resande, 2022; https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2023/country/SE); women use public transport to a higher degree compared to men (see Uteng et al., 2019; Ryan et al., 2023); fewer women possess a driver's license comparable to men; and women have less access to a private car compared to men (Solá, 2016; Kollektivtrafikbarometern 2022 Kvinnors och mäns resande, 2022). Women tend to conduct so-called chain trips, where they conduct multiple errands in one trip. Since women are mostly the main carers, they escort minor children to school or collect goods for dependant relatives, so-called care trips (Friberg, 1993; Ng and Acker, 2018; de Madariaga and Zucchini, 2019; SCB, 2021; Kollektivtrafikbarometern 2022 Kvinnors och mäns resande, 2022; Landby, 2023). Moreover, the intersection of gender and other forms of inequalities, such as those related to disability, defines further burdens and limits to daily mobility (see, e.g., Egard et al., 2022; Landby, 2023).

Women are also self-reporting higher levels of stress, regardless of family situation. Gender-related time inequalities have been stressed by the literature on time poverty and time pressure since the 1970's. Vickery (1977) can be mentioned as a pioneer in her work on time poverty. Balbo (1978) published on women's double presence and Hochschild (1989, 1997) on time bind and the second shift. More recent research has been exploring the relationship between temporal stress, gendered division of household labor (e.g., Craig and Baxter, 2016), and temporal social norms defining gendered time use expectations (e.g., Epstein, 2004; Minnen et al., 2015). Statistics on time-use gender inequalities in Sweden (European Institute for Gender Equality) show that, while the time devoted to activities related to care and education for children, grandchildren, elderly, or people with disabilities is equally distributed between men and women, time devoted to cooking and housework weighs on women to a larger extent. At the same time, Swedish women allocate less time to leisure and voluntary or charitable activities than men. From an intersectional perspective, it is important to note that the difference in time spent on housework for lower-income women is higher than that spent by higher-income women—a difference that is not there in the case of men (SCB, 2021).

Women also work part-time to a higher degree than men (20% compared to 10%, Women and men in Sweden, SCB, 2021, p. 66). According to the statistics, the majority of women claim it has been difficult to find full-time employment or the employer has not offered full-time employment (SCB, 2021, p. 68). The trade union LO, which organizes blue-collar workers in Sweden, has for a long time struggled to force employers to offer women full time, 35 h or more on a weekly basis. The income effect is especially difficult for women in low-salary jobs (https://www.lo.se/start/pressmeddelanden/arbetande_kvinnor_forlorar_5_000_kronor_per_manad_pa_deltid; Garofalo and Laub, 1978).

Finally, the fear of being victimized or assaulted when moving by public transport is important when trying to understand mobility strategies. In a large-scale investigation on customer satisfaction in 28 world cities by Ouali et al. (2020), the results showed that there was “a significant gap between men and women both in perceived satisfaction and in safety. We find that women are 10% more likely than men to feel unsafe in metros and 6% more likely to feel unsafe in buses” (Ouali et al., 2020, p. 738). In a Swedish study (Ceccato et al., 2023), women reported experiences of being sexually offended. Ceccato et al. (2023) asked about travel experiences when going to university campuses using public transport. Both women and men reported experiences of being violated, but 61% of women expressed being sexually victimized when using public transport compared to 27% of the male students (Ceccato et al., 2023, p. 493), which corresponds to the survey conducted by the Kollektivtrafikbarometern 2022 Kvinnors och mäns resande (2022), where especially young women were reporting higher responses regarding measures taken for personal safety, which has been reported in several studies from Great Britain (Box et al., 1988) and Finland (Koskela, 1999). Ceccato et al. (2023, p. 488) also refer to studies showing that this awareness also includes other social groups, such as older adults (Yin, 1980), disabled people (Iudici et al., 2017), people within the LGBTQI community, and poor people. In a Swedish collection focusing on public transportation as a socially sustainable mode of transport, one of the chapters reflected on gay and transgender persons' mixed emotions about using public transportation and the necessity of developing some kind of safety measures to be able to use the services (Wimark, 2020).

Taken together, it should be mentioned that the Swedish policy on gender equality has contributed to strengthening women's rights in several policy areas over the years. However, despite the policy formulations on gender equality, women do not feel safe when moving in public spaces (Listerborn, 2016) or using public transport. Women are sexually harassed, violated, and threatened when moving around, and the outcome is concerns and spatial restrictions because of gender. In a society where mobility is considered self-evident and a necessity to be able to interact in the labor market, in the education system, engage in leisure activities, and socialize with friends and family, women's safety is a matter of social justice (Lucas, 2012; Martens, 2016; Scholten and Joelsson, 2019). The right to be not afraid or be dependent on partners, family members, or friends to move around is an indisputable right (Listerborn, 2002). It is, therefore, of utmost concern to understand how women organize their everyday mobilities and to understand their experiences and concerns. The aim of the article is to contribute to the understanding of gendered mobility strategies, contribute to a more nuanced understanding of gender equality, and give some comments on what needs to be done to improve the sensation of more secure public spaces with a focus on public transportation.

In this article, people defining themselves as women reflect on their experiences of using public transport and moving around. The concept of gendered mobility strategies is used to understand the experiences and how the experiences women have from using public transport and moving around are compatible with the Swedish self-image as a gender-equal society. To discuss the gendered preconditions to carry out everyday mobility projects in time and space and investigate the dimension of gender equality, the gender system theory developed by the Swedish historian Hirdman (1990, 2004) is used together with the study by the German sociologist Sven Kesselring on mobility pioneers (Kesselring, 2006).

1.1 A gender system theory approach to analyze women's mobility strategies and action spaces

Gender system theory (Hirdman, 1990, 2004) aims to explain the power dynamics between women and men. The precondition for the theory is that society is structured by patriarchal logic where the feminine is subordinate to the masculine. The gender system theory identifies two logics which are historically traced through different cultural expressions and texts to ancient Greece: first, the definite, clearcut, and sharp delimitation of the two sex categories “woman” and “man;” and second, the superiority of what is considered on a general term as the “masculine” over the “feminine” (Hirdman, 1988, p. 51). The subordination is rationalized by social, economic, and cultural suppression of what is defined or interpreted as “feminine” (Gemzöe, 2002). According to Gemzöe, this manifests in women being paid less compared to men even in jobs that are equal regarding qualifications and responsibilities, how job status becomes devalued when the working majority shifts from men to women, and how traditional women's cultural expressions are less recognized compared to men's. Evidence of this structural form of discrimination against the feminine can, according to this logic, be found in economic, social, and cultural sectors where women dominate or women are a majority, and it is manifested in how women and men are paid for the work they do, the work conditions they have, other benefits related to work, social and emotional investments, and cultural expressions. The gender system logic has time-specific characteristics and is, according to Hirdman, framed as “gender contracts” between society and women. This is how the relationship between what is considered “masculine” and “feminine” characteristics can change over time and how women continue to live on in societies that are still fundamentally patriarchal.

The logic from the gender system approach also contains spatial domination. The gender system theory revolves around the dual sex categories and heterosexual relations.1 According to the gender system theory, women trade sexual services and emotional labor for the privilege of security and support for themselves and their children. The children are also important since they guarantee the maintenance of the family line, and it is the interest of the male to ensure the continuation of the family. This unequal, patriarchal relationship is based on dependence, which also entitles the masculine control over the feminine and the children. The masculine hereby exercises control of the action space of the subordinated feminine. It becomes in the interest of the patriarchal power to execute control over the family members' movement. From the example of the single-family organization, these power relations can be translated into the societal level, where women are blamed when they are exposed to violence and mistreatment. According to Hirdman, this domination manifests itself by “...women's position in society in relation to men's [which] is characterized by less space, restricted movement, controlled actions. The oppression of women is characterized exactly by the control of women's ability to move in physical and psychological space” (Hirdman, 1990, p. 79, authors translation).

This structural control and domination emanating from a patriarchal organization of society can be translated to the gendered division of fear between the sexes. Tenuous social and cultural norms on women's and men's access to public space and which person can access what spaces during the day are still limiting women and people defining themselves as women the right to free movement in the city and the transport system (Wilson, 1992; Hille, 1999; Spaccatini et al., 2019). This gendered division creates fear among people defining themselves as women, especially self-disciplining practices, to avoid the risk of becoming blamed for being out alone, or worse, attracting attention because of the clothes they wear or not being sober. Such a division of fear puts extra burden on those who define themselves as women when managing their trips and movements, especially in the public transport system.

The gender system theory has been criticized for not offering developed explanations on how changes in the power balances between the sexes are possible (Wetterberg, 1992; Hagemann, 1994) and for being heteronormative. Notwithstanding its limited focus on the binary sex categories, the gender system theory offers, in this specific case, a helpful framework used to analyze and discuss women's mobility strategies when they have to adjust their action space in accordance with the urban complex structure.

The complex urban structure has developed much thanks to car-oriented urban planning, in which zoning and thereby increased travel distance to reach important destinations has become an everyday reality for most people. The combination of urban planning, which requires people to bridge physical distances, and a post-industrial labor market based on what Kesselring (2006) labels the “mobility imperative” (p. 269, see also Urry, 2000) forces people to develop mobility coping strategies (Kesselring, 2006). Coping strategies can contain different resources. According to Kesselring, mobility strategies are defined as “... the inner logic of mobility practice” (p. 270). I understand this as a combination of accepting that everything, such as people, artifacts, information, and non-human agents, is constantly moving (Urry, 2000) and combining this understanding with the capacity to combine different physical and social capabilities. These capabilities can be how to use a smartphone to buy a bus ticket, being knowledgeable about different modes of transport available, and how to engage with the social settings of the mobility system to decide whether one has to physically move or engage via digital communication. Taken together, the inner logic of mobility practice means understanding the logic of planning, organizing, engaging with, and being involved with society in a meaningful way on terms and conditions that make sense to the individual (Kaufmann and Audikana, 2020). According to Kesselring, mobility strategy perspectives can help us understand not only the specific tactical decisions made by people when they are moving in the public transport system but also how individuals develop a more thorough understanding of the meaning of being connected in the world and how life conditions are structured in relation to movement. Understanding the organization of movement, or using the words by Kesselring, the individual's ability to manage mobility is dependent on several aspects. These aspects include, among others, available mobility resources, such as different modes of transport and communication tools, as well as knowledge and competencies to use these different resources. Staying put can also be a strategy, but to many women in the workforce, this is not an option since many Swedish women have employment that requires their attendance in a specific geographical place (Kollektivtrafikbarometern 2022 Kvinnors och mäns resande, 2022). Mobility also takes time and requires allocating transport resources in a coherent structure. There are different perspectives on analyzing the structural conditions for different modes of mobility management.

2 Materials and methods

The empirical material was collected in two separate research projects. The first project was conducted in the Stockholm metropolitan area and the Gothenburg metropolitan area in Sweden. The city districts in Gothenburg and Stockholm are socially and ethnically mixed city districts. They are also considered socio-economically vulnerable, and by the time of the research, the city districts had been on the national police register for areas of special attention due to the high rate of criminality (Polisen, 2015).

The research was conducted through focus groups and interviews in 2019 (Breen, 2006), with 3–11 participants each, taking place in the suburb of Angered, north-west of Gothenburg, and Botkyrka, south of Stockholm (see Table 1). The participants were either looking for employment, attending high school or university studies, or being employed in low-income labor such as elderly care homes. Most of the participants were of ethnic minority origin, e.g., Turkish, Middle Eastern, Slavic, Central Asian, or Somali origin. The participants were recruited to the focus groups by two unemployment agencies, a social network for young people, and among employees at two care homes for elderly people. The focus group meetings were scheduled in the education office they attended for their training or the workplace and lasted for 3 h. The talks were recorded and transcribed. In total, 47 people were engaged in the focus groups and interviews. For this article, the data from the focus groups are used. The groups were made up of immigrant and Swedish young people aged 17–29 years in vocational training for getting a job, except for three people (see Table 1). One focus group included older participants aged 18–51 years working in care homes for elderly people and in social service and included some experiences from older adults and their experiences from using public transport.

Two of the young participants had a driver's license (focus groups 1–4) and access to a car via their families. Most young people lived with their parents or an older sibling. The main focus of the project for which the focus groups were conducted was issues of transport equity (see Henriksson and Lindkvist, 2020, for further details on the research). In the focus groups, the themes of the discussion revolved around the area of the dwelling, how to get around to different activities, the experiences of using public transport, the price of riding public transport, how to organize everyday activities and moving between important everyday destinations, about family responsibilities and accompanying minors or dependent family members, and experiences of safety and the use of different modes of transportation. In the focus groups, the participants were also asked to produce mental maps of their neighborhood and daily movements and to keep a travel diary for a week. The travel diary was used in following-up discussions on mobility and the need for transportation.

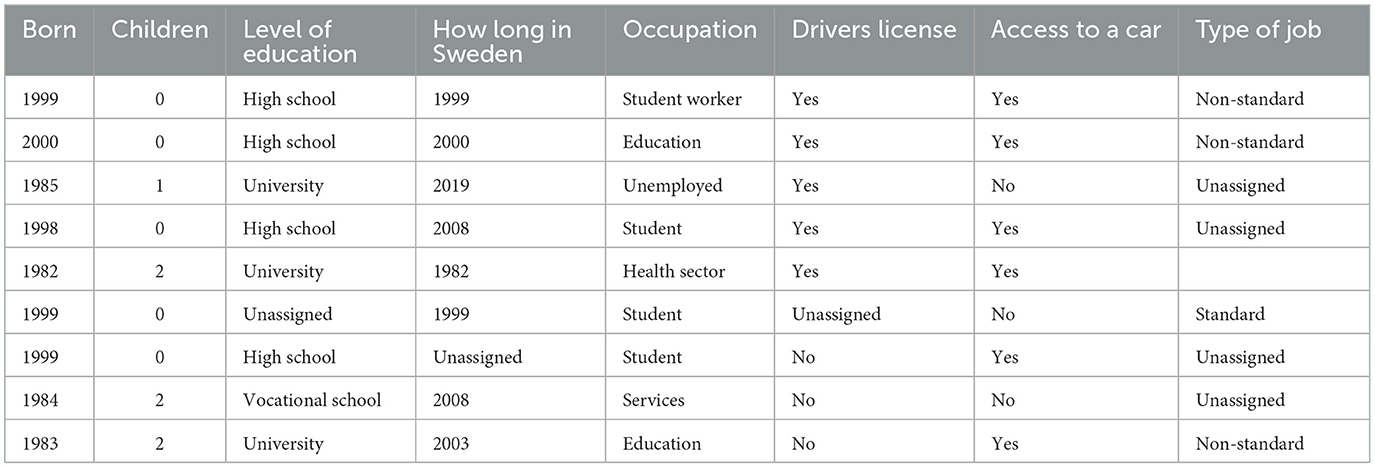

The second research project was conducted in 2019 and 2020 in the Malmö metropolitan area, and 15 individual semi-structured interviews (Brinkmann and Kvale, 2018) were conducted, of which nine people who identified themselves as women were analyzed for this article (see Table 2). The interviews were conducted in a place of choice by the interviewee, lasted 1 h and an hour and a half, and were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The women were born between 1983 and 2000, and four of them had children. One of the interviewees lived with her parents and the others lived in mixed housing neighborhoods. Eight of the interviewees had driver's licenses and access to a car if they needed one, but most of them shared the car with their partner, and it was usually the partner who used the car on a daily basis.

The interview focused on transport equity, where the interviewees' daily schedule and geography to reach important daily destinations were in focus. The interview included questions on the use of different modes of transport, experiences from using public transport, and the level of service and accessibility to everyday important destinations (see Vitrano and Mellquist, 2023, for further details on the research). In both studies, questions connected to safety were raised by the interviewees and the interviewers.

The research projects were not considered to be collecting sensitive data (according to the ethical standards and Swedish legislation for higher education and research), and in line with the recommendations from the ethical approval agency for higher education and research, the ethical approval was not conducted. The participants in the focus groups and the individual interviewees were informed about the project and approved their participation by signing consent forms regarding their participation in the projects, sharing information within the research group, and publishing results.

For this article, the data have been re-examined to especially focus on the parts of gendered experiences using public transport to reach everyday destinations. For this purpose, a thematic analysis was conducted (Maguire and Delahunt, 2017) based on the theoretical framework presented above: gender system and mobility strategies.

2.1 Analytical perspective

This research positions itself in the research tradition of social constructivism, where meaning to everyday situations and objects is created through human interaction and language (Berger and Luckmann, 2023). It also emphasizes contextuality and situatedness, especially emphasized by feminist scholars (Haraway, 2016). A constructivist perspective claims that gender is unstable, fluid, and performative (West and Zimmerman, 1987; Butler, 2009) and varies with geographical location, historical time, and social status (Hirdman, 2004), where the notion of being gendered is time, space, and socially specific constructs.

3 Results

The following section is organized around the themes that the thematic analysis brought forward. The first section deals with measures that people who identify themselves as women are taking to be able to move and their mobility strategies. It also deals with the sense of safety and how the interviewees relate to the spaces of transport they have to engage with to be able to reach their everyday destinations. The second section focuses on the situation on the bus, the commuter train, or the tram and what makes them feel safe or vulnerable. Finally, the third section deals with travels the interviewees conduct with children or because of dependent relatives. This section also highlights the spatial-temporal conditions women face when using public transport for everyday travel.

3.1 Gendered spaces and strategies to keep safe

Women are socialized into social norms that are built on patriarchal power, where they, as girls and later women, are vulnerable to men and that their bodies are not safe in public places during nighttime and, therefore, are taught to be careful. All the interviewees except one who was concerned about moving around, especially at night and on weekends, by the public transport system. They were referring to how they had been told as children to be careful and attentive, not to get in trouble or be violated or sexually abused:

“I've known it since I was a little girl, all my friends in the neighborhood knows that you don't use the tunnels [under the main road] at night. You hardly use them in daytime, because it has happened that people have been mugged, and there is just one main crossing, quite new because people don't use the tunnels” (woman, early 20's, Malmö).

Instead, she and her friends walk along a quite big and busy road and cross the street where it is possible to avoid putting themselves in danger or risk being exposed to harassment. Some of the young women with immigrant backgrounds explained that they were not allowed to stay out after dark, and if they were seeing friends, the parents came to pick them up. Dark and poorly lit environments when walking to a bus and around the public transport stations and bus stops are commonly referred to as hinders to women's feeling of security and, according to the interviewees, prevent women from using public transportation in the evenings and nights. Not being able to see properly or shady and bushy environments where someone could hide gives women a feeling of insecurity.

“The reason which I cannot go out certain hours is because of the fear. Nothing has ever happened, but it's the fear, everything you hear and read about what is happening to girls” (woman, early 20's, Gothenburg).

Another young woman explains:

When it's dark, there are places I don't want to stay at... it's scary, well perhaps not scary, but you are alone, and I get a bit scared... it's dark and just shadows (woman, early 20's, Stockholm).

Traveling by public transport gives a sense of safety, even if situations sometimes occur on the bus or the metro when the women feel themselves exposed and vulnerable.

“I mean, it feels safer to use public transport than walk alone in the middle of the night” (woman, early 20's, Malmö).

Some of the interviewees had been on public transport when there was a situation, but they were not personally attacked; it was more about talks among friends, rumors, and media reporting on situations that were stopping them from going out and using public transport after dark. There are also parts of the city with bad reputations, which the women describe as something they try to avoid. One of the women describes a previous area where she used to live:

“I used to live in that area, and you never knew when things get bad, just taking a walk and you might end up in a situation, and the people living there, could be really hostile, you try not to make too much of yourself, to stay in your own “bubble,” sometimes someone has been following me, but I guess it's something common for women if you go out by yourself in the night, you feel like someone is watching you” (woman, early 20's, Malmö).

A middle-aged woman living in Stockholm explains that women, in general, are concerned about traveling by public transport and moving around out at night:

“I think, no matter if you live in Stockholm or in these surroundings, especially women feel a bit unsafe if the light is poor, the street I usually walk is quite ok, I could take a shortcut through the woods, but I don't” (woman, early 40's, Stockholm).

Two of the interviewees had recently got their driver's licenses. They admitted that it is a great relief to have the possibility to drive and that it is a kind of freedom not to have to be picked up by their parents at night. They are also being allowed to stay out longer hours with their friends when they can drive the car and not use public transport anymore. They also provided a lift for their friends and picked them up when the friends needed to go somewhere or get back home. One of the young women with a driver's license explained to us:

“You don't have to wait for a crowded, dirty bus with a hostile bus driver and getting angry for being treated rude or feeling unsafe at the commuter train station in the night. It is expensive to have a car but it is worth it” (woman, early 20's, Stockholm).

The risk of exposing oneself to harassment or violence and sticking to public transport or being picked up by friends or relatives also contributes to limiting the action space of women. Walking in the dark is a risky situation, which could eventually lead to being accused of not taking precautions and deliberately asking for trouble. Especially young women being out late with friends and partying have to be aware of and organize their time according to the bus timetable so as not to miss the last connection, even if it would be possible to walk the distance home:

R: I wouldn't walk very late at night.

I: Because you wouldn't feel safe?

R: I wouldn't feel safe and also like [...] if you go partying you can't drive if you are going to drink and you don't want to take the cab because it's expensive and I don't like taking the cab because I don't feel safe taking the cab by myself for example, so I would always be…I would be at the club and I would check like the time tables of when I have to leave [laughs] (woman, early 20's, Malmö).

The women are also reflected on the different city districts and how belonging to a specific area in the city contributes to different attitudes and stereotyping of identities. When the women were not familiar with the area, they felt more insecure and vulnerable. There was a concern about how they would be treated by men and boys at the bus stop if they had to tell in which part of the city they live:

“When you have been out here [pointing at the map], partying, it is very scary to walk here [showing on the map] by yourself. Not necessarily because of the people, but the ambient, and these areas (pointing to the east part of the city), it feels like the city doesn't prioritize this part as much as this one (points to the west part of the city). That people [in the east part] feels more excluded and that makes me feel that they [living in the east side] already have opinions about me, just waiting for the bus, and I don't like to talk, I feel like I say the wrong things, so usually I have a male friend waiting together with me for the bus” (woman, early 20's, Malmö).

Below, I will return to the women's comments on maintenance and what could be understood as a lack of care for the environment.

3.2 Strategies for feeling safe on public transport

Being on the bus or the metro is, according to our interviewees, always better than being on the street. In the interviews, the women told us that they prefer to use public transport compared to walking home. However, the safety of the buses is a concern, especially for young women. During peak hours, the buses are overcrowded and messy; at nights and on the weekends, there are noisy groups of youngsters creating chaos and disturbing the other passengers. To choose where to sit on the bus is one strategy adopted by the interviewees:

“I mean, going by bus in the evenings, it's when it happens, not criminality, but chaotic people, they have been drinking too much or taking other stuffs. Especially here, so when I go by bus in the evenings, my mum always tells me to sit at the front seat, close to the driver” (woman, early 20's, Gothenburg).

At the same time, the bus driver is not necessarily the safeguard they are thought to be. All the young women have experienced hostile and rude bus drivers. Several of the interviewees mentioned unpleasant experiences with people using drugs, even during the ride on the tram, “and I told the tram conductor, but he didn't bother at all” (young woman Gothenburg).

Another of the interviewees explains:

“It can be messy, especially during weekends and you don't feel safe, so even when it's little things, like if someone is not nice to you and you are exposed even if there is a lot of people in the commuter train, no one reacts. I have experienced that, and it is the same on the bus and not even the bus driver reacts, and I think it's wrong. They (the noisy people) are affected by drugs, mostly alcohol or I don't know. They are threatening and they misbehave, and often, I understand, everyone is scared so no one reacts, unfortunately” (woman, mid 20's, Stockholm).

As was mentioned above, there is a documented interest among women in traveling more sustainably, and the idea of public transport supports this engagement for sustainability. However, the messy situations, especially during weekends, feeling unsafe, and the dirty and noisy environment made the interviewees choose other modes of transport, preferably to be picked up by a family member:

“I try not to [use the bus], it's quite uncomfortable as a woman to use public transport. Especially on Friday's and Saturdays because of all people out and partying. I have pretty unpleasant experiences and I prefer to go by car home, I call my partner to pick me up or someone else of my relatives. I wish they could do something to make women feel safer” (woman, late 20's, Malmö).

The crowdedness, in general, creates situations that the interviewees experience as stressful. In the buses, there is space for two prams, and sometimes people are denied entering the bus because it is already overcrowded, which creates tensions when people still try to get onto the bus or when someone has a problem getting off because it is full.

“There are so many people and it gets very crowded and chaotic. There are lots of prams and stuff which wants to get aboard but can't find space, and lots of people, and people who cannot get off and yes, it becomes chaotic” (woman, mid 20's, Malmö).

Maintenance is also important for the feeling of safety when using the public transport. Just like the women in the interviews and focus groups reflected on the poor and harsh environment in different parts of the city, the environment on board the bus or train is important. The interviewees, except for one, reflected on dirty buses and subways; the lack of care for the interior of the vehicles is an issue and sometimes makes it difficult for women to use the bus or the commuter train. An interviewee and a mother of a minor told us that her daughter becomes easily sick from dirty environments where chewing gums are stuck in the seats. The daughter does not want to sit properly on the seat, and that is dangerous if it is a careless bus driver. “…and some of the drivers do drive carelessly and that is something you don't know until you are on the bus,” another woman in her 30's tells us.

In several interviews, the women told us how they appreciate the idea of using public transport, choosing a sustainable mode of transport, and that traveling together is a good thing for the environment. A woman in her mid-20's in Malmö reflects on the idea of traveling by public transport:

“Still, I like the idea of thinking sustainability. I don't have to spend money and petrol and have a negative impact on the climate. I like traveling with others. But still, it's strange, because it can be really disgusting on the buses sometimes, and then I think, why did I choose this...”

3.3 Managing public transport fares and time schedules

Even if seven out of 34 women in the focus groups and interviews have driver's licenses, they do not have access to a car on a daily basis. They are representatives of the Swedish national statistics that indicate a lower level of driver's licenses for women compared to men. The women are all dependent on public transport to reach everyday destinations:

“Since I don't have a driver's license, I am pretty dependent on public transport, I live here and not inside the city, we live on the outskirts, it is at least half an hour with the bus to get here, so I use public transport to go to the gym, doing my grocery shopping, my everyday errands, so to speak” (woman, mid 20's, Malmö).

Time schedules, whether it is the public transport timetable, working hours, or opening hours where women do errands such as taking children to schools, shops, or other amenities, organize and structure how women plan their trips. When everything is running as it should, the public transport system is considered very convenient. “If I miss the bus there is another one in 10 min, it's very good” (woman, early 40's, Malmö). However, when there are hick-ups in the transport system and the bus or commuter train is canceled, it creates stress and frustration for being late for picking up the children at school or the daycare center.

The design of the public transport system is an important factor for women without a driver's license and access to a car. The Swedish labor market is distinct when it comes to gender. The largest employer in Sweden is the care sector and care homes for the elderly and daycare centers for children are quite evenly distributed in the urban fabric. When new residential areas are built, there are public services provided, but, not necessarily public transport. This becomes an accessibility issue for women working non-regular working hours in social services.

Occasionally, the connections do not work, even if they should according to the timetables. Sometimes, the connecting bus or train leaves too early, which is described as extremely annoying by the women. There were even examples given in the interviews that people had turned job opportunities down because of poor connections between different parts of the city. The feeling of not having control over your time, waiting for public transport which might arrive, makes life unpredictable in a frustrating way. The irregularities in keeping the time schedule make the interviewees develop strategies to get on time, and it is usually about taking one or two buses earlier than necessary, just to make sure to be on time for work or school.

“I always check the bus, like I got this when I went to high school, the bus was always late, so I developed this habit to always checking the time table to see if anything is happening, so I always check the bus” (woman, early 20's, Malmö).

Another interviewee is very annoyed by the situation, “why should I give 20 min for free to my employer every day, just because I can't trust the timetable for the bus?” (woman, 40's, Malmö).

With a low salary (the average income for an assistant nurse, which is the most common occupation for women in Sweden, is between 24,700 and 34,400 SEK before tax), a monthly card for travel with public transport is expensive. Women who are in education or vocational programs can have their monthly card paid for by social services or the school. For others, the expense is between 550 and 800 SEK, depending on where in Sweden they reside. The upside of a monthly card is that you can share it with others, which was common among the interviewees who had one. Nowdays the monthly card is digital and can easily be transferred between cell-phones. “It's very easy,” a young woman told us: “if you have the monthly card, you can lend it by sending it by the phone number to the person who needs to borrow it, it's very convenient.”

When you cannot afford a monthly card and must buy single tickets, it impacts your travel behavior. In some regions in Sweden (which are responsible for organizing public transport), you can use one ticket for 90 min, meaning you can go and come back home with the same ticket. The fares are considered expensive. One of the interviewees explain:

“You try to minimize the travel time. If you have a travel card with cash, then you have 90 min to use the ticket, from when you tap it for going and have to be back home. Otherwise, you have to tap it again and then you have to pay the double price, so sometimes when friends ask if we should meet before going somewhere, I say no, because otherwise I have to pay double, it becomes more expensive if I stay longer” (woman, mid 20's, Stockholm).

The fares for public transport tickets sometimes impacted the travel, and the interviewees explained this by rhetorical questions such as “do I really have to go? Do I really want to go? Can I do this errand some other time?” Finally, the price of tickets impacted the travel conducted. When asked if the interviewee would have traveled more if the ticket price was lower, we got the following answer:

“Perhaps I would have traveled to Lund more often. Now I go to Lund when I must. It's quite expensive, a monthly card with connections to Lund is 800 SEK or something, so it's quite a difference, if there was alternative, perhaps I would have bought that and used it more frequently, I have friends in Lund and I have relatives in Lund and I used to study in Lund, nowadays I really must plan when to go there” (woman, early 20's, Malmö).

The characteristics of the neighborhoods also have a significant impact on the sense of having options in reach. The socioeconomic underprivileged city districts struggle to invest in children's activities, and at the same time, efforts are made in other places, such as the case of Malmö, which is close to the sea. One of the women explains:

“Here at Lindängen, there are many poor families with many, many children, and even if they (the municipality) do a lot of nice playgrounds at the sea for the kids, there are many families who can't go there” (woman, early 40's, Malmö).

Having a monthly card gives freedom for travel. The feeling of freedom, not being stuck in one place, can match the expenses of buying the monthly card:

“Since I don't drive, it feels, even if I don't use the card, I know I can get around. Yes anywhere. I go to my daughter in Uppsala, with my monthly card and sometimes, when it comes to work situations, different vocational trainings for my job, you can move around more freely. It's during work hours, but I have my monthly card, I use it” (woman, early 50's, Stockholm).

3.4 Gendered rhythms and gender norms

The earlier sections give examples of how young women being out with friends are constantly “online” with the time schedule for public transport and how the timetable organizes the hours when they can stay out with friends. Women also have more family-related responsibilities compared to men, and when traveling, they also conduct more of so-called chain trips, which have been labeled care trips (de Madariaga and Zucchini, 2019). The combination of public transport timetables, opening hours of daycare centers and schools for minors, and other daily services in combination with work hours are structuring the activity space available to the women. One of the interviewees tells us: “My mother is dependent on me to help her out moving around, quite a lot dependent actually, to get to the doctor and so on” (woman, early 40's, Malmö). The care trips she is conducting are squeezed in between working hours and other time schedules to which she is subjugated. All in all, these kinds of trips contribute to a complex network of shorter travels, usually with a combination of walking and public transport.

A good example of this structure is the following description:

“Usually I walk, I leave my daughter at school, and we walk there. Then I take the bus and my stop is at Dalaplan and from there I walk, or not Dalaplan, the stop before, I usually travel with the bus number 2. And often I must go back to pick up my daughter after school, take her to my cousin where she stays in the afternoons, and then I take the bus back to work. So, sometimes I use the bus 3–4 times a day” (woman, early 40's, Malmö).

The women with children who are going to activities in different parts of the city learn the different routes and which bus line takes them to their destination in the most efficient way. Interchanges are considered difficult because there is limited space for trollies on the bus and because it is stressful to get off and hop on the right bus when you are accompanying young children. The trip also sometimes becomes much longer because there are no direct lines to where you need to go:

“I have younger siblings and you can't take them to the beach at Västra Hamnen, the water is too deep, so I have to take them to Ribban (another beach in Malmö) and then you have to change the bus which can be problematic with two small children. Otherwise, I believe I can reach most of my destinations” (woman, mid 20's, Malmö).

Another example from the interviews is a woman in her early 20's in Malmö who is a group leader for younger children's activities in the evening. She uses public transport to get to the activity, but the bus schedule is not really synchronized with the hours of the activities. In her case, she has solved the problem of getting late by having two friends who can welcome the children and start the activities before she arrives. She, on the other side, stays late to close and put stuff away before leaving in the evening.

Leisure trips are not only long and sometimes exhausting. In Sweden, families can choose their children's school through a free choice option. This means that a family in a socially disadvantaged neighborhood where the schools might have a bad reputation or are not performing well can choose another school in another part of the city. In Gothenburg, one of the women told us that she would apply for a school in a more affluent area where she used to live before they had children and had to find a larger apartment. “The schools there are very good,” she told us but it means she has to travel 40 min one way each day. She found herself lucky because the tram will take her directly to the city district where the school is located.

The caring responsibilities were manifested in how the women described how they were taking care of younger siblings or dependent relatives. There was the mother of two in Gothenburg, who would be traveling on the tram for 40 min from one direction to the opposite of the city center when her children began to go to school. It will be her responsibility, and her time schedule that needs to be adjusted to be able to have her children in a school of preference. It is the daughter who takes her mother to medical appointments and must organize her schedule in accordance with the caring responsibility for her dependent mother. It is the mother of two who rides the bus across the city of Malmö to let her children get to know different parts of the city and visit leisure activities. There were women working in low-wage occupations or being unemployed who could not afford to visit friends and relatives because of the ticket prices on public transport. The gender contract, the relation between women and society, implicitly requires women to adapt and adjust their schedules to others.

4 Discussion

In this article, the gendered practices and strategies in everyday mobility have been investigated from a feminist perspective (Koskela, 1997, 1999; Law, 1999; Listerborn, 2002), where people defining themselves as women have shared their experiences and thoughts about their everyday movements based on using public transport. The motivation for writing the article is an urgent need to open a discussion on what it means to live in a gender-equal society where women and men are entitled to the same rights to protection and safety when moving around. From the unconditional right to be mobile or choose not to move (Sheller, 2018), the limitations and restrictions of women's movement are, in this context, understood as patriarchal structures that deny people, defining themselves as women, the right to access public spaces, to be mobile, and to feel safe when traveling by public transport. The voices from the focus groups and interviews reveal that the physical threats and violence are not usually directed toward them as women. Instead, the patriarchal power structures work much more sophisticated by imposing self-discipline and self-withdrawal from public space. The safety issues also transcend the individual since the care and responsibility concerns dependent family members and the care in escorting them (de Madariaga and Zucchini, 2019) is deeply included in the gender contract between women and society. This also leads to women developing strategies on how to move and access everyday important destinations without exposing themselves or dependent family members to danger and limiting themselves according to the time schedules of others.

The findings presented are coherent with what is found in research in criminology on women's behavior and strategies to avoid being exposed to or, even worse, becoming victimized by fellow users of the transport system (Killias and Clerici, 2000; Loukaitou-Sideris, 2020; Ouali et al., 2020; Ceccato et al., 2023). In addition, the experience of displacement as a woman using the transport system as a public space for transportation is confirmed by the interviewees. The tenuous historical and socio-cultural construction of the decent woman (Wilson, 1992; Rose, 1993; Massey, 1994; Spain, 2000) is still haunting today's women who need and want to live their lives as independent and self-managing individuals. The deeply embedded patriarchy in society still controls women from accessing public spaces and transport services to get home from work, meeting with friends, or just for the freedom of movement. With jobs organized outside of office hours, women must move around and should be able to do so without the risk of being harassed or victimized. Having a night out with friends should not end with the question of how to get a safe home. From the interviews, the dimensions of ethnic minority and age, as well as the spatial limitations, become even more strong. The result is that women, by themselves or by their parents, protect themselves from unpleasant situations and organize everyday movements so they can avoid being in specific places at specific times. The masculine superiority, to use the phrase from Hirdman's gender system theory (Hirdman, 1988), delimits women's movement and women's available action space.

From the mobility strategies perspective, in combination with gender system theory, the individual develops a mobility sensitivity regarding security, where gender identity, age, socioeconomic status, and ethnic background intersect and produce gendered mobility strategies where the individual develops an internal time scheduling mode and ableness to read and interpret situations not to get in trouble. Bodies wearing the signs of femininity become tempo-spatially self-disciplined and solve the risk of being harassed by not staying out late or submitting themselves to the tempo-spatial control of partners and parents. On top of this, the organization of work hours and public transport timetables contributes to time-spatial limitations for women. The concept of mobility strategies, as formulated by Kesselring (2006), needs to include the strategies developed by women to feel safe while practicing everyday mobility. My suggestion is to use the concept of gendered mobility strategies to ensure the conditions of being defined by a sex category and what that definition implies regarding mobility.

As mentioned in the introduction section, Sweden has a reputation for being gender equal. The findings from a Swedish context might not be able to apply to contexts outside the Scandinavian because of the discursive understanding of Sweden as something exceptional. The main contribution of this article is to show that gender equality is never done or finally reached. Gender equality is something that needs to be considered in all societies at all times. Depending on what kind of gender contract is presently organizing the relationship between women, men, and society, the gendered power structures will reveal themselves in different shapes. This piece of work is a reminder that the work for gender equality must never stop, and the work must be done in all areas of society.

Different solutions are presented by public bodies to ensure safer travels for women, and there are examples of women's only taxis and public transport, such as metros and buses (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/26/women-only-train-carriages-around-the-world-jeremy-corbyn). None of these is a solution to the problem of men taking the liberty to uninvitedly approach random women in public space. Investigating what groups heavily dependent on public transport need in terms of safety—by asking them and inviting them to produce and plan better services is one important first step (Ryan et al., 2023; Vitrano and Mellquist, 2023).

Data availability statement

The author has no permission to share data. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to amVzc2ljYS5iZXJnQHZ0aS5zZQ==; Y2hpYXJhLnZpdHJhbm9AdnRpLnNl.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because semi structured interviews and focus group interviews where attendants are given information about the aim and purpose of the study and have to sign a written consent where it is clearly stated that they can withdraw without further explanation to the research team, does not require ethical approval according to the Swedish Ethical Research Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

CL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research was funded by the Swedish National Knowledge Center on Public Transport, K2, funding register number: 2018001 and 2018029.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Jessica Berg and Chiara Vitrano, at VTI, Sweden for stimulating research collaboration. I am grateful for the generous funding of the original research project, received from K2, the Swedish National Knowledge Centre for Public Transport. I highly appreciated the valuable and constructive comments from the two reviewers and the support from the Frontiers in Sustainable Cities Editorial Office.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^For which the gender system theory has been criticized.

References

Berger, P., and Luckmann, T. (2023). “The social construction of reality,” in Social Theory Re-wired (London: Routledge), 92–101.

Bondemark, A., Andersson, H., Wretstrand, A., and Brundell-Freij, K. (2021). Is it expensive to be poor? Public transport in Sweden. Transportation 48, 2709–2734. doi: 10.1007/s11116-020-10145-5

Box, S., Hale, C., and Andrews, G. (1988). Explaining fear of crime. Br. J. Criminol. 28, 340–356. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a047733

Breen, R. L. (2006). A practical guide to focus-group research. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 30, 463–475. doi: 10.1080/03098260600927575

Butler, J. (2009). Performativity, precarity and sexual politics. Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana 4:40303e. doi: 10.11156/aibr.040303e

Castells, M., and Cardoso, G., (eds.). (2006). The Network Society: From Knowledge to Policy. Washington, DC: Johns Hopkins Center for Transatlantic Relations, 323.

Ceccato, V., Langefors, L., and Näsman, P. (2023). The impact of fear on young people's mobility. Eur. J. Criminol. 20, 486–506. doi: 10.1177/14773708211013299

Craig, L., and Baxter, J. (2016). Domestic outsourcing, housework shares and subjective time pressure: gender differences in the correlates of hiring help. Soc. Indicat. Res. 125, 271–288. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0833-1

de Madariaga, I. S., and Zucchini, E. (2019). Measuring mobilities of care, a challenge for transport agendas. Integr. Gender Transp. Plan. 7, 145–173. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-05042-9_7

Egard, H., Hansson, K., and Wästerfors, D. (2022). Accessibility Denied: Understanding Inaccessibility and Everyday Resistance to Inclusion for Persons With Disabilities (London: Taylor & Francis), 232.

Epstein, C. F. (2004). “Border crossings: the constraints of time norms in the transgression of gender and professional roles,” in Fighting For Time: Shifting Boundaries of Work and Social Life, eds. C. F. Epstein and A. L. Kalleberg (Newyork, NY: Russell Sage Foundation), 317–340.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Fenster, T. (2005). The right to the gendered city: different formations of belonging in everyday life. J. Gender Stud. 14, 217–231. doi: 10.1080/09589230500264109

Friberg, T. (1993). Everyday life: Women's adoptive strategies in time and space. Lund Stud. Geogr. 55, 1–218.

Friberg, T., Brusman, M., and Nilsson, M. (2004). Persontransporternas “vita fläckar”: om arbetspendling med kollektivtrafik ur ett jämställdhetsperspektiv. Linköping: Linköpings Universitet.

Garofalo, J., and Laub, J. (1978). The fear of crime: broadening our perspective. Victimology 3, 242–253.

Hagemann, G. (1994). Postmodernismen en användbar men opålitlig bundsförvant. Tidskrift för genusvetenskap 3:sid-19. doi: 10.55870/tgv.v15i3.4882

Hanson, S. (2010). Gender and mobility: new approaches for informing sustainability. Gender Place Cult. 17, 5–23. doi: 10.1080/09663690903498225

Haraway, D. (2016). “Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective,” in Space, Gender, Knowledge: Feminist Readings, eds. L. McDowell and J. Sharp (London: Routledge), 53–72.

Henriksson, M., and Lindkvist, C. (2020). Kollektiva resor: utmaningar för socialt hållbar tillgänglighet. Lund: Arkiv förlag.

Hille, K. (1999). “Gendered exclusions”: women's fear of violence and changing relations to space. Geografiska Annal. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 81, 111–124. doi: 10.1111/j.0435-3684.1999.00052.x

Hirdman, Y. (1988). Genussystemet-reflexioner kring kvinnors sociala underordning. Tidskrift för genusvetenskap 3:sid-49. doi: 10.55870/tgv.v9i3.5365

Hirdman, Y. (1990). Genussystemet i Demokrati och makt i Sverige: Maktutredningens huvudrapport, SOU 1990: 44. Stockholm: Allmänna Förlaget.

Hirdman, Y. (2004). Genussystemet-reflexioner kring kvinnors sociala underordning. I genushistoria-en historiografisk expos. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Hochschild, A. R. (1989). The Second Shift. Working Parents and the Revolution at Home. New York, NY: Viking.

Iudici, A., Bertoli, L., and Faccio, E. (2017). The “invisible” needs of women with disabilities in transportation systems. Crime Prev. Commun. Saf. 19, 264–275. doi: 10.1057/s41300-017-0031-6

Kaufmann, V., and Audikana, A. (2020). Mobility Capital and Motility (No. BOOK_CHAP) (Abingdon, VA: Routledge), 430.

Kesselring, S. (2006). Pioneering mobilities: new patterns of movement and motility in a mobile world. Environ. Plan. A 38, 269–279. doi: 10.1068/a37279

Killias, M., and Clerici, C. (2000). Different measures of vulnerability in their relation to different dimensions of fear of crime. Br. J. Criminol. 40, 437–450. doi: 10.1093/bjc/40.3.437

Koglin, T., and Rye, T. (2014). The marginalisation of bicycling in Modernist urban transport planning. J. Transp. Health 1, 214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jth.2014.09.006

Kollektivtrafikbarometern 2022 Kvinnors och mäns resande Svensk Kollektivtrafik. (2022). The Barometer of Public Transport - Women and Men's Travelling 2022. Available online at: https://www.svenskkollektivtrafik.se/globalassets/svenskkollektivtrafik/dokument/aktuellt-och-debatt/publikationer/kvinnors-och-mans-resande-2022.pdf (accessed February 5, 2024).

Koskela, H. (1997). “Bold walk and breakings”: women's spatial confidence versus fear of violence. Gender Place Cult. 4:301. doi: 10.1080/09663699725369

Koskela, H. (1999). “Gendered exclusions”: women's fear of violence and changing relations to space. Geografiska Annal. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 81, 111–124. doi: 10.1111/1468-0467.00067

Landby, E. (2023). A family perspective on daily (im) mobilities and gender-disability intersectionality in Sweden. Gender Place Cult. 2023, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2023.2249249

Law, R. (1999). Beyond “women and transport”: towards new geographies of gender and daily mobility. Progr. Hum. Geogr. 23, 567–588. doi: 10.1191/030913299666161864

Listerborn, C. (2002). Trygg stad: diskurser om kvinnors rädsla i forskning, policyutveckling och lokal praktik. Gothenburg: Chalmers Tekniska Hogskola.

Listerborn, C. (2016). Feminist struggle over urban safety and the politics of space. Eur. J. Women's Stud. 23, 251–264. doi: 10.1177/1350506815616409

Litman, T. (1996). Using road pricing revenue: economic efficiency and equity considerations. Transport. Res. Record 1558, 24–28. doi: 10.1177/0361198196155800104

Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (2020). A gendered view of mobility and transport. Engender. Cit. 2:2. doi: 10.4324/9781351200912-2

Lucas, K. (2004). “Transport and social exclusion,” in Running on Empty (Bristol: Policy Press), 39–54.

Lucas, K. (2012). Transport and social exclusion: where are we now? Transp. Pol. 20, 105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.01.013

Lucas, K., Mattioli, G., Verlinghieri, E., and Guzman, A. (2016). “Transport poverty and its adverse social consequences,” in Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Transport, Vol. 169, No. 6 (London: Thomas Telford Ltd), 353–365.

Magnusson, E., Rönnblom, M., and Silius, H. (2008). Critical Studies of Gender Equalities: Nordic Dislocations, Dilemmas and Contradictions. Göteborg & Stockholm: Makadam Förlag.

Maguire, M., and Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: a practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Ireland J. High. Educ. 9.

Martinsson, L., and Griffin, G. (2016). Challenging the Myth of Gender Equality in Sweden. Bristol: Policy Press.

Melby, K., Ravn, A. B., and Wetterberg, C. C. (2008). “A Nordic model of gender equality? Introduction,” in Gender Equality and Welfare Politics in Scandinavia (Policy Press), 1–24.

Minnen, J., Glorieux, I., and Pieter van Tienoven, T. (2015). Who works when? Towards a typology of weekly work patterns in Belgium. Time Soc. 25:918. doi: 10.1177/0961463X15590918

Nelischer, K. (2018). Women's Right to the City. The Site Magazine. Available online at: https://www.thesitemagazine.com/thesitemagazine

Ng, W. S., and Acker, A. (2018). Understanding Urban Travel Behaviour By Gender for Efficient and Equitable Transport Policies. International Transport Forum. Available online at: https://www.itf-oecd.org/

Ouali, L. A. B., Graham, D. J., Barron, A., and Trompet, M. (2020). Gender differences in the perception of safety in public transport. J. Royal Stat. Soc. Ser. A 183, 737–769. doi: 10.1111/rssa.12558

Polisen (2015). Utsatta områden -sociala risker, kollektiv förmåga och oönskade händelser. Nationella operativa avdelningen. Stockholm: Underrättelseenheten. (Exposed Districts - Social Risks, Collective Capabilities and Unwanted Incidents. The Swedish Police).

Rose, G. (1993). Feminism & Geography: the Limits of Geographical Knowledge. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Ryan, J., Pereira, R. H., and Andersson, M. (2023). Accessibility and space-time differences in when and how different groups (choose to) travel. J. Transp. Geogr. 111:103665. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2023.103665

SCB (2021). En fråga om tid (TID2021) En studie av tidsanvändning bland kvinnor och män 2021 (A question about time - a study of time use among women and men 2021). Stockholm.

Schiller, P. L., and Kenworthy, J. (2017). An Introduction to Sustainable Transportation: Policy, Planning and Implementation. London: Routledge.

Scholten, C., Friberg, T., and Sandén, A. (2012). Re-reading time-geography from a gender perspective: examples from gendered mobility. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 103, 584–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9663.2012.00717.x

Scholten, C., and Jönsson, S. (2010). Påbjuden valfrihet? om långpendlares och arbetsgivares förhållningssätt till regionförstoringens effekter. Växjö: Institutionen för samhällsvetenskaper, Linnéuniversitetet.

Scholten, C. L., and Joelsson, T. (2019). Integrating Gender Into Transport Planning: From One to Many Tracks. Berlin: Springer.

Sheller, M. (2006). “Gendered mobilities: epilogue,” in Gendered Mobilities, eds. T. P. Uteng and T. Cresswell (Aldershot: Ashgate), 270.

Sheller, M. (2018). Mobility Justice: The Politics of Movement in an Age of Extremes. London: Verso Books.

Sheller, M., and Urry, J. (2006). The new mobilities paradigm. Environ. Plan. A 38, 207–226. doi: 10.1068/a37268

Smidfelt Rosqvist, L. (2019). “Gendered perspectives on Swedish transport policy-making: an issue for gendered sustainability too,” in Integrating Gender Into Transport Planning: From One to Many Tracks, 69–87.

Solá, A. G. (2016). Constructing work travel inequalities: the role of household gender contracts. J. Transp. Geogr. 53, 32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2016.04.007

Spaccatini, F., Pacilli, M. G., Giovannelli, I., Roccato, M., and Penone, G. (2019). Sexualized victims of stranger harassment and victim blaming: the moderating role of right-wing authoritarianism. Sexual. Cult. 23, 811–825. doi: 10.1007/s12119-019-09592-9

Transport Analysis Follow-up of Transport Policy Objectives (2014). Summary Report. Available online at: https://www.trafa.se/globalassets/rapporter/summary-report/2011-2015/2014/summary-report-2014_5-follow-up-of-transport-policy-objectives.pdf

Urry, J. (2000). Mobile sociology. Br. J. Sociol. 51, 185–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2000.00185.x

Uteng, T. P., Christensen, H. R., and Levin, L. (2019). Gendering Smart Mobilities. London: Routledge.

Vickery, C. (1977). The time-poor: a new look at poverty. J. Hum. Resour. 12, 27–48. doi: 10.2307/145597

Vitrano, C., and Mellquist, L. (2023). Spatiotemporal accessibility by public transport and time wealth: insights from two peripheral neighbourhoods in Malmö, Sweden. Time Soc. 32, 3–32. doi: 10.1177/0961463X221112305

West, C., and Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender Soc. 1, 125–151. doi: 10.1177/0891243287001002002

Wetterberg, C. C. (1992). Från patriarkat till genussystem-och vad kommer sedan? Tidskrift för genusvetenskap 3:sid-34. doi: 10.55870/tgv.v13i3.5035

Wilson, E. (1992). The Sphinx in the City: Urban Life, the Control of Disorder, and Women. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Wimark, T. (2020). “Hbtq och nyanländ - begränsningar och möjligheter i mobilitet för personer med dubbelt utanförskap,” in Kollektiva resor - utmaningar för socialt hållbar tillgänglighet, eds. M. Henriksson and C. Lindkvist (Lund: Arkiv).

Keywords: gender equality, mobility strategies, public transport, women, gender system theory

Citation: Lindkvist C (2024) Gendered mobility strategies and challenges to sustainable travel—patriarchal norms controlling women's everyday transportation. Front. Sustain. Cities 6:1367238. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2024.1367238

Received: 23 February 2024; Accepted: 14 May 2024;

Published: 03 June 2024.

Edited by:

Inés Novella Abril, Universitat Politècnica de València, SpainReviewed by:

Mihai S. Rusu, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, RomaniaNeil Simcock, Liverpool John Moores University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2024 Lindkvist. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christina Lindkvist, Y2hyaXN0aW5hLmxpbmRrdmlzdEBtYXUuc2U=

Christina Lindkvist

Christina Lindkvist