- 1African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC), Nairobi, Kenya

- 2Institute of Development Studies (IDS), Brighton, United Kingdom

Introduction: It is widely acknowledged that vulnerable populations are hit very hard, both in the short and long term, when their health and wellbeing needs are not met. Despite the efforts at different levels to protect and promote their health and wellbeing, older persons, people with disabilities and children heads of households, continue to face significant social, economic and cultural difficulties in relation to health and wellbeing inequities. While rights to health and wellbeing are constitutionally guaranteed, and strategies can be advanced to reduce vulnerable situations, challenges persists and yet societies, communities, and individual factors that engender vulnerability are understudied and remain poorly understood. Situating our findings and understandings within CLUVA social vulnerability framework, allows us to adapt a conceptual framework for understanding vulnerability to health and wellbeing challenges across different groups in informal urban space. We used CLUVA social vulnerability framework to explore and uncover drivers of vulnerability to health and wellbeing challenges among the vulnerable and marginalized groups using the governance diaries approach.

Methods: This was an ethnographic study, using governance diaries with 24 participants in Korogocho and Viwandani informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. The governance diaries approach involved bi-weekly governance in-depth interviews (IDIs) with study participants for 4 months, complemented with observations, reflections, participant diaries and informal discussions. We used framework analysis methodology.

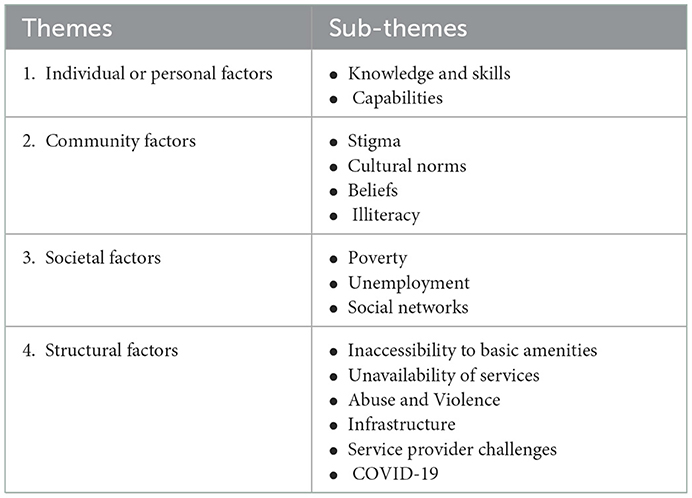

Results: We identified several interlinked drivers and grouped them as individual, community, societal and structural level factors.

Discussion: A comprehensive view of drivers at different levels will help actors engage in more expansive and collaborative thinking about strategies that can effectively reduce health and wellbeing challenges.

Conclusion: The factors identified come together to shape functioning and capabilities of vulnerable groups in informal settlements. Beyond applying a more comprehensive concept of understanding health and wellbeing challenges, It is important to understand the drivers of vulnerability to health and wellbeing challenges from the perspective of marginalized and vulnerable populations. Particularly for local urban planning, the information should blend routine data with participatory assessment within different areas and groups in the city.

Introduction

Unplanned settlements continues to grow in cities and towns in Low and Middle income Countries (LMIC), due to the inability of local and national governments to adequately manage rapid urbanization and to meet the evolving needs of residents in cities and towns (United Nations Human Settlements Programme, 2016; UN Habitat, 2022). Rapid and unplanned urbanization increases the vulnerability of residents living in informal settlements to health and wellbeing challenges that includes natural and artificial risks (Williams et al., 2019; Zerbo et al., 2020). Residents of informal settlements typically face multiple risks due to (a) hazardous shelter and local environmental conditions; (b) limited or non-existent access to safe water, sanitation, public transport and clean energy; (c) tenure insecurity; (d) exclusion from affordable, high-quality healthcare, education, waste management and other vital services; (e) spatial segregation; (f) violence and insecurity; and (g) political marginalization (Corburn and Karanja, 2016). As such residents in informal settlements experience poorer health and wellbeing than those in neighboring urban areas or even rural areas (Emina et al., 2011; Ezeh et al., 2016). The residents who are exposed to vulnerableconditions include individuals who face systemic difficulties, exclusion and discrimination based on their age, disability, race, ethnicity, gender, income level, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation, and migratory status (Atkinson and Flint, 2001; Brady), in addition to persons with disability (PWD), child-head of households (CHHs) and older persons in informal settlements (Browne, 2015; Zerbo et al., 2020; Brady). In the informal settlements where these vulnerable and marginalized citizens live, there is the near absence of the public service and such groups are mostly invisible and much efforts are needed to protect and promote inclusive urban health and wellbeing at all times (Zerbo et al., 2020).

In 2015, United Nations member states adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (CSDH, 2008). These inter-related goals aim to reduce poverty, improve health and wellbeing and ensure all people enjoy peace and prosperity without social exclusions (Rice et al., 2022). The World Cities Report 2022 envisages an optimistic scenario of urban futures that relies on collaborative interventions to tackle multidimensional poverty and inequalities; build healthy and thriving cities; promote well-planned and managed urbanization processes; and ensure inclusive digital economies for the future (UN Habitat, 2022). Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) refer to particular needs of vulnerable populations as an entitlement rather than charity (Roelen and Sabates-Wheeler, 2012). The optimistic scenario envisions concerted holistic new urban agenda framework for urban development that encourages the integration of all facets of sustainable development to promote inclusion (UN Habitat, 2022). Despite the efforts, older persons, people with disabilities and children heading households still face social, economic and cultural difficulties in relation health and wellbeing challenges (Bezerra et al., 2013). Yet, among the rights that are constitutionally guaranteed, is the right to health and wellbeing, which is of particular importance (Kenya, 2022).

Children including child-head of households are more vulnerable to health and wellbeing challenges (UNICEF, 2018; Thaly, 2021). Three elements of challenges for a CHHs are biological and physical challenges; strategic challenges (i.e., children's limited levels of autonomy and dependence on adults); and institutional invisibility due to a lack of voice in policy agendas (Roelen and Sabates-Wheeler, 2012). Older people face challenges including a lack of access to regular income, work and health care; declining physical and mental capacities; and dependency within the household (Sepúlveda and Nyst, 2012). Without income or work, older people tend to depend on others for their survival and are usually vulnerable in informal settlements where their caregivers also have health and wellbeing challenges (Wairiuko et al., 2017; Mehra et al., 2020). PWD are often (sometimes incorrectly) assumed to be unable to work and hence increasing their vulnerabilities to health and wellbeing challenges (Lippold and Burns, 2009; World Health Organization, 2020). Evidence shows that PWD have higher rates of poverty, and face physical, communication and attitudinal barriers, and a lack of sensitivity or awareness (Rohwerder, 2014). With the clear understanding of different vulnerable population, It is widely acknowledged that vulnerable populations have unique basic needs from the general population and are harder hit, both in the short and long term, when there is no action taken (Roelen and Sabates-Wheeler, 2012; Zerbo et al., 2020).

Older persons', PWD and CHHs' vulnerability to health and wellbeing risks is rising on the social protection agenda, but coverage is still low (Kohn, 2014; Browne, 2015; Bright, 2017). Vulnerable populations are usually included in mainstream programmes for support if they meet standard criteria, or sometimes, they are targeted specifically (Brady; Sarma and Pais, 2008). However, most common form of support does not reach the majority (Browne, 2015; Shiba et al., 2016; Brady). Governments can do what one individual cannot; they can transform unfavorable settings or conditions that decrease access to support on public services such as health, education, transportation, clean water, and sanitation into safe and health-promoting settings, yet little is done (Browne, 2015; Barron et al., 2022). On the other hand, societies, communities and individuals can promote change that will reduce vulnerable situations, yet societies, communities, and individuals factors are undervalued and understudied (Ahmad, 2008; Butler et al., 2020). A Lack of data in slums across cities has been identified as a major hindrance to answering questions critical to the health and wellbeingw (3-D Commission, 2021; Kibuchi et al., 2022), more so data on drivers of vulnerability among the most marginalized populations (Rohwerder, 2014). We therefore used CLUVA social vulnerability framework to explore and uncover determinant factors and drivers of vulnerability to health and wellbeing inequities among the vulnerable and marginalized populations in informal settlements using governance diaries approach.

Conceptual framework

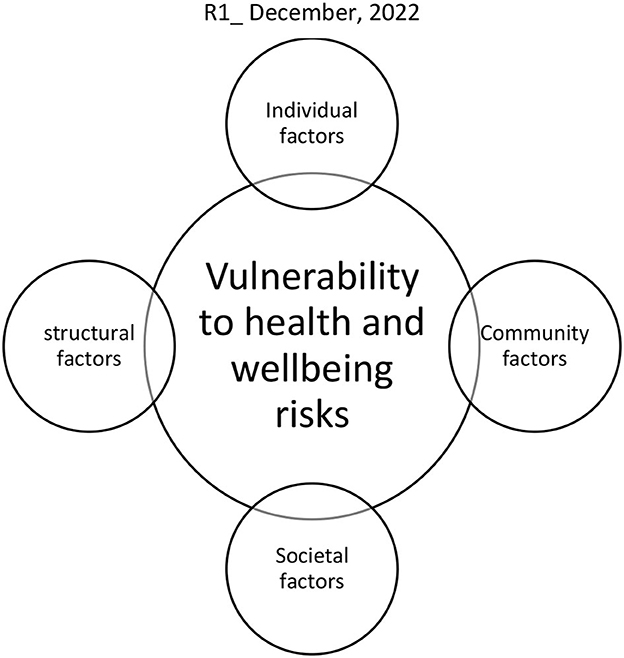

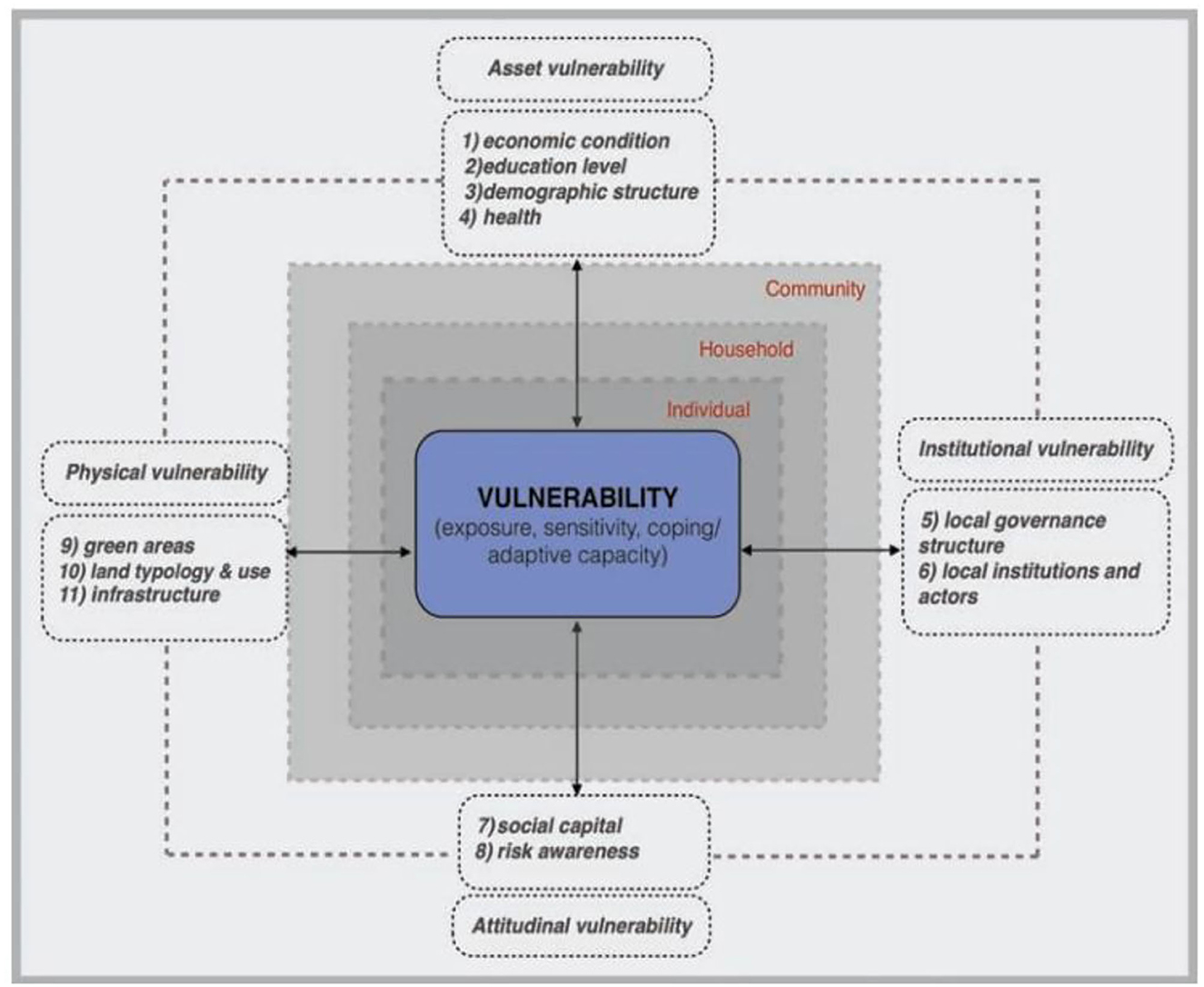

Social vulnerability framework describes how assessing social vulnerability requires considering contextual circumstances (Bright, 2017; Zerbo et al., 2020). This allows highlighting and interlinking relevant factors/indicators at individual, household, community and society levels, which are encompassed in four key dimensions as shown in Figure 1: Asset vulnerability which encompasses the human livelihood and material resources of individuals and groups; institutional vulnerability which refers to the state of local authorities and civil action groups that operate to prevent, adapt or reduce the effect of extreme weather events; attitudinal vulnerability which represents the perception and risk management attitude of individuals and groups and physical vulnerability which accounts for the natural and/or man-made characteristics of the built environment and land cover (Kunath and Kabisch, 2011). The vulnerabilities are anchored at different levels and the framework is applicable to our study because we present vulnerabilities to health and wellbeing inequities anchored at the individual, community, societal and structural factors.

Figure 1. CLUVA framework for assessing vulnerability, adapted from Adrien Coly et al. (2012).

Literature review

This section presents the literature of vulnerability and informal settlements in Kenya.

Vulnerability

Urban planners and public health practitioners attempt to identify and then remove, or at least reduce, threats of harm. However, harm does not affect everyone in the same way. Some people and communities are resilient, whereas others are more susceptible to potential harm. Much urban planning and public health work is carried out by, or on behalf of, governments', where people or communities are at great risk of harm, government has a clear and firm responsibility to protect its citizens. One way of describing a potential source of such a risk of harm is to focus on the idea of vulnerability (Barrett et al., 2015). The concept vulnerability with regard to groups and individuals implies the ones who are more exposed to risks than their peers, in terms of deprivation (food, education, and parental care), exploitation, abuse, neglect, violence, and infection to diseases (Arora et al., 2015; Zerbo et al., 2020). Vulnerability is a relative state that may range from resilience to total helplessness.

Informal settlements in Kenya

Informal settlements are unplanned sites that are not compliant with authorized regulations (Satterthwaite, 2018). The widespread growth of informal settlements in urban centers in Kenya has become a central debate in urbanization during the last two decades (Mberu et al., 2016). Yet, the hesitancy of the Kenyan government regarding improving informal settlements and at least providing the minimum support for basic requirements and services has led to unimaginable suffering among residents (Mutisya and Yarime, 2011). This is coupled with the fact that the government has had a history of failing to recognize the growth and proliferation of informal settlements and, thus, excludes the urban poor from the rest of the city's development plan (Atkinson and Flint, 2001; Mutisya and Yarime, 2011). While constitutional and attitudinal changes are observable, it is hoped that advocating for the urban poor, particularly marginalized and vulnerable groups, would help change the course of events in informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya.

Methods

Aim/objectives and study design

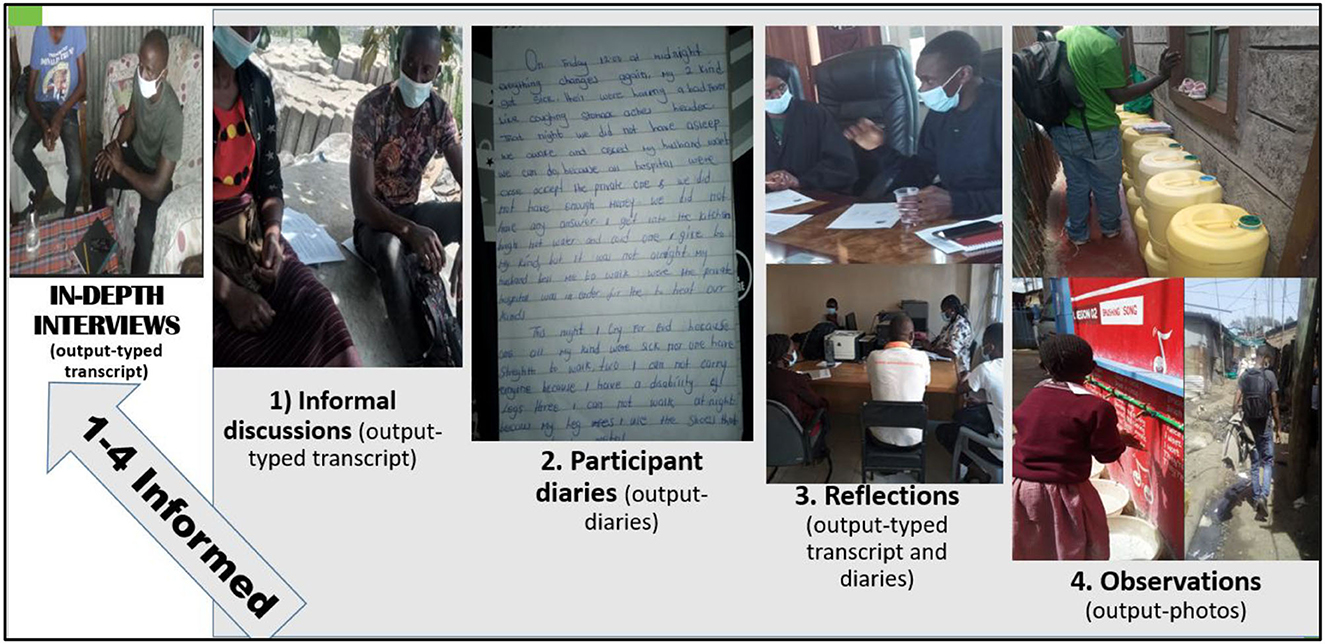

Our study sought to explore the drivers of vulnerability to health and wellbeing challenges among the vulnerable and marginalized populations using governance diaries approach. This study was implemented using the qualitative governance diaries methodogy. Governance diaries is an ethnographic approach using more than one method of data collection and where participants make regular records of their daily activities and experiences (Bishop, 2015; Munyewende et al., 2015; Tkacz, 2021). For this study, governance diaries included in-depth interviews (IDIs), which were informed by participant diaries, informal discussions, participant observations and reflections. Governance diaries are typically used in contexts where there is a need to explore the depth of everyday life, as time allows researchers to spend longer periods in the field for exploration (Munyewende et al., 2015; de Lanerolle et al., 2017).

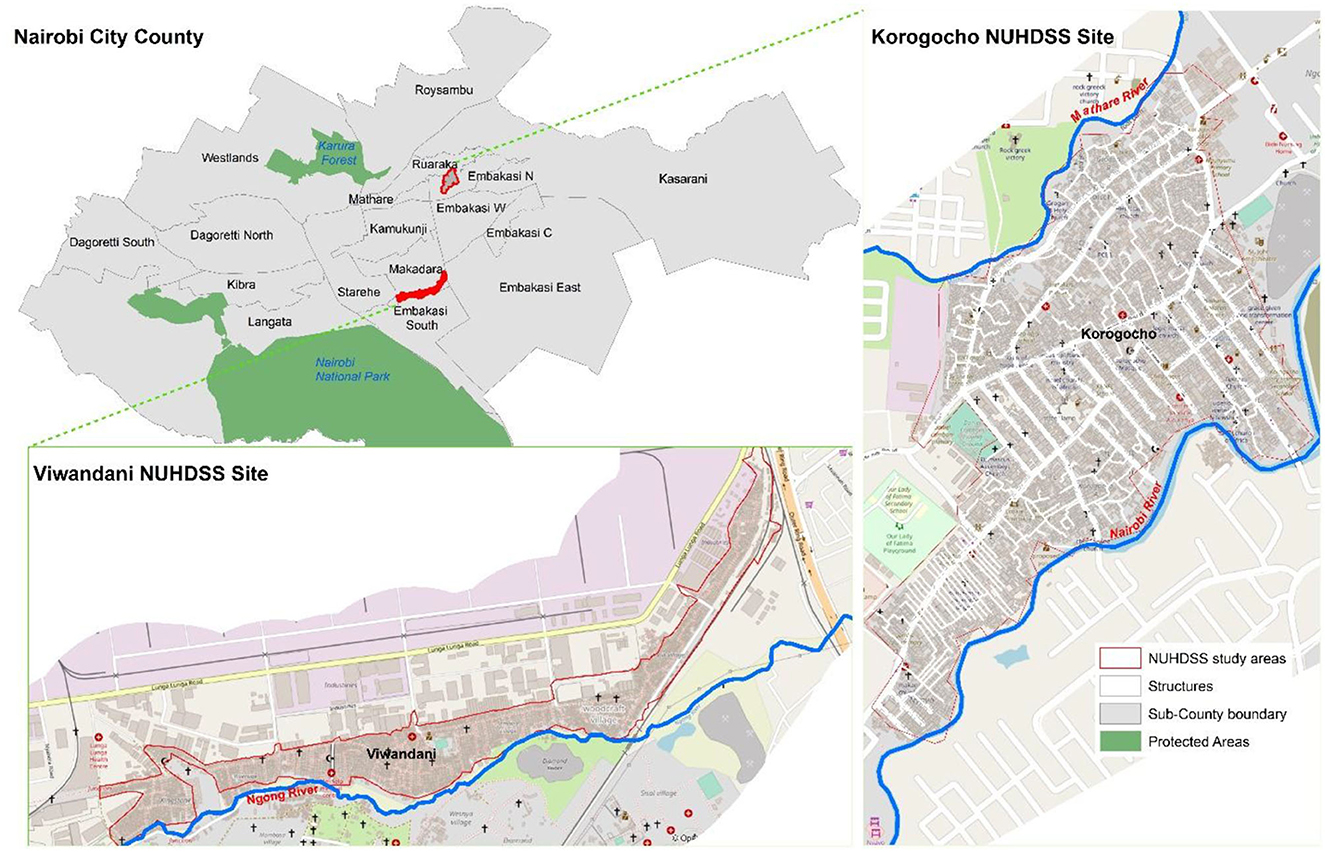

Study setting

The study was conducted in Korogocho and Viwandani informal settlements in Nairobi, in the areas covered by Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System (NUHDSS) initiated in 2002 by the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) (Beguy et al., 2015). Korogocho has a stable and settled population and residents have lived in the area for many years (Emina et al., 2011), while Viwandani is located next to an industrial area with many highly mobile residents who work or seek jobs in the industrial area (Emina et al., 2011). Vulnerable groups identified through a social mapping process included persons with disability (PWD), older persons and child heads of households (Atkinson and Flint, 2001; Zerbo et al., 2020; Brady). Further, each of the informal settlements has 8 subdivisions/units/villages, which acted as a guide during the selection of study participants (Figure 2).

Target population, sampling and sample size

The population of interest were PWD, child headed households and older persons. We sampled 24 participants comprising 4 PWD, 4 child headed households and 4 older persons in each of the study sites. We purposively selected the participants' who were residents and benefiting from services from at least two units/villages.

Data collection process

Community Advisory Committees (CACs) (individuals selected by the community to represent them and act as a liaison between the researchers and the community) worked with co-researchers (community members who are recruited as research assistants because they have a better understanding of the context and respondents could create a good rapport with them) together with researchers in the recruitment of study participants. We used governance diaries to collect data from January to April 2021 with questions related to drivers of vulnerability to health and wellbeing challenges among the vulnerable populations. Diaries were implemented through IDIs, participant observation, participant diaries, reflection meetings and informal discussions. IDIs were the dominant method and were informed by the other methods. Below is the description of data collection process.

Informal discussions

An informal conversation was carried out between the participant and the researcher just before the IDIs to find out key insights and to create rapport with the study participants before the IDIs- The discussions were incorporated in the IDIs;

Reflexive discussions/reflections

There were reflective discussions between pairs of research assistants, among the whole group of research assistants and between researchers and research assistants, and were done daily, weekly and bi-weekly respectively to understand the outcome and determine emerging themes and gaps to be probed during subsequent IDIs and routine observations.

Observations

This included observation by the co-researchers, which allowed for a holistic awareness of events as they unfold and as such, a more comprehensive understanding of what matters to respondents. We also observed the environment related to our study subject including observing health and wellbeing services undertaken by the research assistants. This resulted in photos and insights on what to probe in the IDIs. The research assistant whose role was to be an observer did the observations before, during, and after the IDIs to complement the discussions recorded and to inform and complement participant diaries, reflexive discussions and IDIs. Reflexive discussions informed the content and concepts for observations.

Participant diaries

We provided the study participants with guidelines pasted on the front of the diary. Each participant would write daily activities related to formal and informal support actors and related networks at their homes, without writing their names. Research assistants/co-researchers would call participants and conduct impromptu visits to remind participants about diary writing activities.

IDIs

We used guides with questions on formal and informal support actors and related for the vulnerable populations. IDIs for subsequent visits on the same questions were adapted based on observations, reflections, informal discussion and participant diaries (Figure 3). In-depth conversation/discussion between the research assistant and the study participants were administered in pairs of 2 research assistants; one who was moderating the interviews and the second, acting as an observer, note taker and facilitating the recording of the conversations. We reached saturation in the IDIs with the 24 participants in the sixth visit when we were approaching the fourth month.

The outputs from informal discussions, observations, participant diaries and reflections informed and enhanced robust probing during IDIs. For example, if the co-researchers observed some ambulance or water pipe bursts next to their home. During IDIs, they would probe on how long it has been leaking? Who should fix the water pipes? Among other questions. The multi-pronged ethnographic data collection processes are summarized in Figure 3.

Research assistants/co-researchers received training for 6 days on the aims of the study, data collection process, data collection tools, and research ethics. We piloted the study tools with one older person, PWD and child headed households in each of the study site, followed by a debriefing to assess if the study approach and study tools were well understood by both research assistants and study participants. The pilot exercise also enabled us to adjust the translated guides to concepts understood by the study participants and to estimate the time an interview could take. We excluded participants in the pilot from the main study. During fieldwork, researchers accompanied the co-researchers to assess data quality through spot-checks. Team debriefing sessions were held at the end of each working day to assess progress and ensure quality data collection processes. Researchers and co-researcher debriefings were conducted weekly for cross-learning, while research assistant reflexive sessions were held after every round of the six visits to reflect on the previous round of data collection and to strengthen research skills for the next round of visits.

Data management

Recorded audios from IDIs, reflections and informal discussions were translated and transcribed from Swahili to English and saved as individual Microsoft Word documents. Outputs (Figure 3) were assigned number codes to prepare for analysis and to ensure confidentiality. Thereafter, transcripts were imported into NVivo 12 software (QSR International, Australia) for coding and analysis. Each transcript had a unique identifier comprising participant category, study site and sex to enhance anonymity and facilitate informed analysis. Outputs that could not be typed (photos from observations and participant diaries) were scanned and saved in a safe folder by the researchers, as they were reference materials during data analysis.

Data analysis

Transcripts were imported into NVivo 12 software (QSR International, Australia) for coding and analysis. NVivo is a qualitative data management software that can be shared and worked on in groups and facilitate thinking, linking, writing, modeling and graphing in ways that go beyond a simple dependence on coding (Bazeley and Jackson, 2013). We used a framework analysis (Gale et al., 2013), informed by the CLUVA framework (Ii et al., 2003). Framework analysis is adopted for research that has specific questions, a pre-designed sample and priory issues (Gale et al., 2013). The first step of framework analysis was listening to the recordings to familiarize the researchers with the drivers of vulnerability. To ensure reliability, two researchers (an experienced qualitative researcher and an anthropologist) and 5 co-researchers, who collected the data participated in the development of a coding framework by reading the outputs imported in NVivo 12 software, participant diaries and photos independently to establish an inter-coder agreement. Once the initial coding framework was completed, the team met to discuss the themes generated and to reach an agreement on themes (Table 1). The two researchers proceeded with coding, charting, mapping and interpretation of transcripts.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the AMREF Health Africa's Ethics and Scientific Review Committee (ESRC), REF: AMREF-ESRC P747/2020. We also obtained approvals from National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI), REF: NACOSTI/P/20/7726. Approval was also obtained from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) and the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) internal ethical review committee. All participants provided informed written consent before participating in an interview including consent for using photos and videos if there were any.

Results

Drivers of vulnerabilities to health and wellbeing challenges

We present drivers in four themes of individual, community, societal and structural factors (Table 2).

a) Individual factors

Individual level factors are those that are present or absent in an individual who is marginalized or vulnerable (Angeles et al., 2022). Individual level factors included challenges related to age, knowledge, skills and capabilities.

Knowledge and skills

The older residents described how some community members perceived them as unworthy to learn, receive new information or engage in skill development. The child-head of households on the other hand were marginalized and did not receive information that could help their livelihood including information on informal labor available.

“Because of my old age, no one thinks that I am worthy to be taught anything new or to receive any support on skills development” (IDI, Older person, Viwandani, F).

“I am old and also with this illness {chronic illness}, Nobody is willing to provide me with information because they think I am not important… When there is relief food no one bothers to pass on the information, thy treat PWD like us” (IDI, Older person, Viwandani, F).

“I don't receive any information on employment… even the informal employment in the community” (IDI, Child-head of household, Korogocho, M).

Capabilities

The study participants stated how they lacked capabilities to access basic amenities. This was attributed to scarcity in resources and their conditions. For example PWD may not use a sanitation facility because it is not adapted to their needs/conditions.

“People like me who depend on free water from borehole face hardships because sometimes, there is water scarcity at the borehole” (IDI, Older person, Viwandani, M).

“People with disability have a challenge using the normal toilets” (IDI, PWD, Viwandani, M).

b) Community factors

Community level factors are neighborhood characteristics that may aid or hinder an individual's efforts. The key community-level factors were challenges from the community associated with stigma, cultural norms, beliefs and illiteracy.

Stigma

“Old is usually supposed to be gold… However, that is not the case in this community. No one treasures our knowledge. At every place you go, they say women and youth should have a priority. We end up isolated and we are going through difficult circumstances” (IDI, Older person, Viwandani, M).

“To be sincere, we are going through difficult circumstances, people refer to us as children with children and when there is relief food or water, we are not lucky to access… when in the health facility, it is the same thing… I usually try my level best not to go to public facilities like health centre or even to think of going back to school” (IDI, Child-head of household, Korogocho, F).

“Children with disabilities can be easily singled out from the rest…many parents don't often bath them or feed them if they are unable to feed themselves.” (IDI, PWD, Viwandani, M).

Cultural norms

“The disabled are marginalized…An individual may have a child with disability but they hide them… they don't want them to be seen. Therefore, many disabled children in this community do not go to school and do not receive other child related benefits” (IDI, PWD, Korogocho, F).

“There is a time I decided to go back to school, other children did not want to speak with me, they did not want to share a seat with me… I felt ashamed and left the school” (IDI, Child-head of household, Viwandani, M).

“When you go to the health clinic, you are not given a priority like other groups; they think you should be in school and not in the health facility seeking for child care services” (IDI, Child-head of household, Viwandani, F).

Beliefs

“The mentally ill…are also marginalized. When they talk something which is right; it appears that they are wrong because they are mentally ill” (IDI, PWD, Viwandani, F).

“People discriminate us… they think we are like this {showing her disability} because of a curse and we can transfer the curse to them… So we have challenges in accessing all basic services” (IDI, PWD, Viwandani, M).

“I cannot go back to school because other children laugh at me… I cannot go to the health facility unless it is a critical condition or unless the community health volunteer is going with me… Other mothers in the hospital think that you are a bad person since you are a child and you have a child” (IDI, Child-head of household Viwandani, F).

Illiteracy

“I usually depend on my neighbour for all the information I need regarding health… I trust her. All has been well except for last week my child had eye ache and she gave me some drugs that was used by his son… the drugs worsened the health of my child” (IDI, Child-head of household Korogocho, F).

“I am not very educated… I depend on friends for Covid-19 information… Even them {friends} are not very educated but they are employed and are likely to know better than me… Last week they told me that Corona is not in our village and there is no need to worry much about wearing masks” (IDI, Child-head of household, Viwandani, M).

“I am waiting for my grandchild to help me read the labels in the drugs… If she will be late, I just have to wait… One time, a neighbour's child read the label wrongly and I had to go back to hospital the next day” (IDI, Older person, Viwandani, M).

c) Societal factors

Society level factors include elements which occur at a level beyond the community—such as at the municipal, state level, or federal level. Societal factors identified included challenges associated with poverty, unemployment, and poor social networks.

Poverty

Older persons with health challenges and could not afford healthy food were vulnerable and food insecure.

“I can just say it's just how sometimes someone just feel they are weak in the body because of hunger and I could not afford good food. What happens is after taking milk with bread just like someone living with diabetes, my blood sugar rose so I tried every means to ensure the blood sugar goes down but until yesterday it did not reduce.” (IDI, Older person, Viwandani, M).

“From money you have, you may be able to get food and the rent but you don't have the school fees and the situation has been difficult” (IDI, Child-head of household, Viwandani, F).

“Older people with disability are slow in movement so by the time I arrive to the free water collection point or point of disbursing relief food, there will be none left and I just have to find a way of buying water or food, yet I don't have money” (IDI, Older person, Viwandani, M).

“I am needy, yet I have never received any information on relief food, free water or anything free from government” (IDI, PWD, Korogocho, F).

Unemployment

“I am discriminated and so I have no friend, I cannot find any job… Parents think I dropped from school and so I can influence their children to drop from school too… That is why sometimes I take alcohol so that I forget the frustration” (IDI, Child-head of household, Viwandani, M).

“The discrimination to me has been extended to my children and so the children do not even get common employment given to the youth in the village- like the youth being employed for solid waste work” (IDI, PWD, Korogocho, F).

“Youth involved in garbage collection are hand-picked, no one has ever noticed me yet I am needy and have no one to depend on. I mostly get no jobs” (IDI, Child-head of household, Korogocho, F).

“I do not have any chance of being employed because of my health condition” (IDI, Older person, Viwandani, M). “My lower educational level and inability to see has made people not to employ me” (IDI, PWD, Korogocho, M).

Inadequate social networks

“The older persons with special needs who are often at home and in poor health conditions are more vulnerable, they cannot move or do anything and they don't have resources or anyone to support them” (IDI, PWD, Korogocho, M).

“When we are writing names for people to receive donations like relief food, or clothing, some people delete the names of older persons and persons with disability and sometimes no one is willing to help them write their names” (IDI, Older person, Viwandani, M).

“I stay alone… I have no one to help me understand the information shared widely on Covid-19… You see the information in the paper there, I cannot read and no one is here to help me read” (IDI, Older person, Korogocho, M).

“{Name of an informal actor} and some people who were passing by here told us that there is no Corona… the government is using Corona to receive loan and support from well off countries” (IDI, Child-head of household, Viwandani, M).

d) Structural factors

Structural factors refer to the broader political, economic, social, environmental conditions and institutional factors. The factors provide a part of the contextual information necessary to interpret the individual and community and societal factors. Poor access to health and wellbeing amenities, lack of health and wellbeing amenities, abuse and violence, infrastructural challenges, service provider challenges and Covid-19 challenges were identified as structural factors impacting health and wellbeing of marginalized and vulnerable populations.

Inaccessibility of basic amenities

Older persons were also left out in many community activities. Further, they could not scramble for available basic resources and during distribution and ended up without any basic service.

“Mostly the elderly, for example, at the water point, we will not scramble like others; we step aside not unless someone is merciful to help us… so in many cases, we do not benefit from handouts/donations” (IDI, Older person, Viwandani, F).

“We are left out in community activities and in decision making… even community education nobody remembers the elderly” (IDI, Older person, Korogocho, M).

“When you go to the water point you are the last person to fetch water and sometimes by the time it is your turn… the vendor would have run short of water” (IDI, Child-head of household, Korogocho, F).

Unavailability of services

“There are people who have toilets in their plots…We do not have any here and so we pay for toilet… when we do not have money, it is usually a challenge” (IDI, PWD, Viwandani, F).

“We do not have a public school and we do not have a public health facility in our village” (IDI, Child-head of household, Korogocho, M).

Abuse and violence

“If you are disabled… and you go someplace to fetch water…you find that your water cans are taken to the back of the queue (IDI, PWD, Viwandani, F).

“My age has made me go through many life challenges; because of hardship that I am going through in accessing water, health, toilet and other services, my children and grandchildren are also discriminated and are going through many difficulties in accessing basic services… a while back my child was sexually abused” (IDI, Older person, Korogocho, F).

“There is a boy who was bullying me when I was in school because I did not have a good uniform… He was bright and favoured by each teacher. If you went and reported to the teacher, the teacher would not have listened to you.” (IDI, Child-head of household, Korogocho, F).

Infrastructural challenges

“The visually impaired people are in difficult situation because they have so much challenges… they can hit something or fall in a hole and no one will help them out because they have disability… Even if I have disability I use crutches and keep going unlike the blind, so the blind, deaf and the paralyzed are more marginalized and vulnerable.” (IDI, PWD, Korogocho, M).

“People like me depending on water kiosks have a problem because there is no fixed price, sometimes it is too expensive and I cannot afford… I have to depend on water kiosks because I am weak and not able to go far to the borehole at the school” (IDI, Older person, Korogocho, M).

“Those who are constructing toilets do not consider us{PWD}, we are left out. It is hard for me using the normal toilets, because of my condition, but I have no option” (IDI, PWD, Korogocho, M).

Service provider challenges

“I mainly do not go to the public health facility because if I go there, they will start to speak badly to me and they will start to tell me that I am young and I have such bad behaviour of giving birth to children when I am young. When they tell me that, I do feel bad… We were 3 girls and we had gone there for clinic and that is what they said and we have never gone there again.” (IDI, Child-head of household, Korogocho, F).

“My child is going through lots of discrimination, abuse and other difficulties because she is mostly lacking basic things like uniform” (IDI, PWD, Viwandani, M).

COVID-19 challenges

“It is difficult nowadays because if you keep your child inside the plot there is no one who will know if they are going to school or not, so it is difficult to follow up. In the past {before Covid-19}, the Chairman {local leaders} used to follow on but nowadays with the Covid-19 situation, it is not possible” (IDI, PWD, Viwandani, F).

“Covid-19 has made challenges we face to be too challenging… Community leaders and community volunteers, who would visit homes to hear our issues and offer support are no longer visiting because of such things as social distance” (IDI, PWD, Viwandani, M).

“We are socially isolated… If people are treated equally, life would be simple for us… The only job I can find is for solid waste work and we are using protective clothing used by nurses in the hospital… sometimes I fear for my health” (IDI, Child-head of household, Korogocho, F).

“Currently mental health of women with disability is really affected as men in the family no longer go out to work, Men are idle and want money and other basic needs” (IDI, PWD, Korogocho, F).

Discussion

The SDGs agenda 2030, based on the monitoring and evaluation of global debates and discussions, takes a comprehensive approach to poverty and informal settlements, by introducing a goal dedicated to cities, SDG Goal 11 aims to “make cities and human settlements inclusive safe, resilient and sustainable.” The vision of sustainable and equitable urban futures will not be guaranteed unless actors take bold and decisive actions to address urban challenges (UN Habitat, 2022). The study has identified the interaction between the different factors which affect health and wellbeing challenges among the vulnerable population. Using governance diaries approach, we identified four driving factors of vulnerability to poor health and wellbeing among the vulnerable and marginalized population in Nairobi informal settlements. The factors that included individual, community, societal and structural factors, were interrelated and interlinked (Figure 4). We found good alignment between the factors identified by the three different vulnerable and marginalized groups (PWD, CHH and older persons). The drivers identified were similar in relation to studies conducted previously describing consistency in the individual, interpersonal, community, societal, and structural factors underlying health and wellbeing of mining workers (Rice et al., 2022). The findings from this study will reinforces the literature on vulnerability to health and wellbeing challenges among the vulnerable populations in informal settlements. It strengthens the perspective that while urbanization can be beneficial for health and wellbeing, the increase in informal settlements represents a significant challenge for advancing health and wellbeing in the global south, since informal settlements are also the location of persistent vulnerabilities (Corburn and Karanja, 2016).

Determinant factors have a bearing on health and wellbeing challenges of the vulnerable populations. The individual's lack of knowledge and skills; community stigma, cultural norms, beliefs and illiteracy on health and wellbeing needs of vulnerable populations, as well as societal and structural factors were identified as contributors to high mortality rates, due to preference for of traditional healers over biomedical treatment, and preference of traditional approaches to handling environment and mental health issues over biomedical and professional approach (CSDH, 2008; Muchukuri and Grenier, 2009). Older persons, CHHs and PWD are vulnerable to higher health and wellbeing challenges, for example, the vulnerable groups are able to work provided they are given the opportunity to learn the required skills and to access employment. As such, improving access and opportunities will enable them to become eligible for social and financial benefits (Rohwerder, 2014). Our findings speak to the multiple vulnerable groups and interrelated and interlinked drivers of vulnerabilities. Past studies have described how community factors, environmental, social and political forces simultaneously influence health in these communities (Rifai et al., 2016; Alelah, 2017).

Overall, the study underscores the importance of understanding vulnerability to health and wellbeing disadvantages among the vulnerable populations. The results point to the need for policy makers to be aware of the existence of exclusions and disparities even among the urban poor. The results support the idea that health and wellbeing intervention strategies could benefit from being supplemented with strategies aimed at the general population, as individual, community and societal perception, attitude and will is required for mechanisms to operate contextually (CSDH, 2008; Chumo et al., 2021). Moreover, interventions at the structural context, could be supplemented with individual, community and societal level interventions for maximum benefit to the vulnerable population. This is consistent with previous studies describing the importance of supplementing interventions, aimed at reducing socioeconomic inequality with strategies aimed at poverty and illiteracy reduction (Egondi et al., 2015).

Similar to other studies, we suggest the need for policy agenda to ensure at all levels– in government, public and private institutions, workplaces, family, societal and the community that there is considerate accounting of vulnerable populations living and working in informal settlements for creating healthy societies (World Health Organization, 2003). By acknowledging and acting on interrelated drivers of vulnerabilities to health and wellbeing, policies will not only improve health and wellbeing of the vulnerable populations, but may also reduce a range of other social problems that flourish alongside health and wellbeing inequities and catastrophes, rooted in some of the same socioeconomic, political, environmental and technological processes. Further, the comprehensive view of drivers at different levels will help decision-makers engage in more expansive and collaborative thinking about strategies that can effectively improve health and wellbeing outcomes. Lastly, our results will also help to assign responsibility and accountability for addressing health and wellbeing inequities across an array of actors at the community, society, family or government level (3-D Commission, 2021).

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study builds on our strong networks in the study sites, well-trained and skilled data collectors recruited from the community and the ability to use an existing framework for analysis. This strengthened the validity of the study results. Our study however, is not without limitations. It was conducted in only two informal settlements in Nairobi with vulnerable groups identified through the social mapping phase. It was indeed adequate for painting the picture of drivers of vulnerability to health and wellbeing challenges among the vulnerable and marginalized populations. Nonetheless, a more holistic approach that combines qualitative and quantitative data, and integrates all stakeholders would be necessary for a broader understanding of the many aspects of the study. Although the relative importance of the emerging themes might vary or the presence of other more pressing drivers may exist in other settings, the overarching value of the governance diaries strategy we used is that the results can be widely applied in diverse settings to shape efforts to reduce vulnerabilities to health and wellbeing needs. Importantly, the governance diaries approach derived insights from the vulnerable populations that might have been otherwise overlooked.

Conclusion

In the context of clear imperative to urgently address the SDG1, SDG3 and SDG11, understanding drivers of vulnerabilities to health and wellbeing challenges remain imperative. As long as the informal settlements remains present in LMICs, investment into addressing drivers of health and wellbeing disadvantages may form a crucial part of implementing inclusive programmatic activities, with focus at multiple levels: structural, societal, community, as well as individual factors. This will enable vulnerable groups to benefit as their context is considered and that the interventions are designed to target the most marginalized groups.

Beyond applying a more comprehensive concept of understanding health and wellbeing challenges, It is important to understand the drivers of vulnerability to health and wellbeing challenges from the perspective of marginalized and vulnerable populations. Particularly for local urban planning, it should blend routine information with participatory assessment within different areas and groups in the city. The governance diaries approach showed the new evidence this provides, as marginalized are vulnerable groups who are not always involved in decisions that affects them were engaged.

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because other manuscripts are still being written using the same data.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the AMREF Health Africa's Ethics Scientific Review Committee (ESRC), REF: AMREF-ESRC P747/2020. We obtained a research permit from National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI), REF: NACOSTI/P/20/7726. Approval was also obtained from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) and the African Population and health Research Centre (APHRC) internal ethical review committee. All participants provided informed written consent before participating in an interview including consent for using photos and videos if there were any. Written informed consent from the participants' legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

IC and BM: conceptualization. IC: data curation. IC and CK: formal analysis. IC, CK, AS, and BM: methodology and writing. All authors approved the manuscript for submission.

Funding

The GCRF Accountability for Informal Urban Equity Hub (ARISE) funded the project activities through the UKRI Collective Fund award reference ES/S00811X/1.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all participants who took part in this study and colleagues at APHRC and ARISE consortium for their guidance and input during this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

APHRC, African Population and Health Research Center; CAC, Community Advisory Committee; COREQ, Criteria for Reporting Qualitative research; ESRC, Ethics and Scientific Review Committee; IDIs, In Depth Interviews; NACOSTI, National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation; NUHDSS, Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System; PWD, Persons with Disability.

References

Adrien Coly, A., Risi, R. D., di Ruocco, A., Garcia-Aristizabal, A., Herslund, L., Jalayer, F., et al. (2012). “Climate change and vulnerability of African cities,” in ResearchGate, Vol. 1, eds P. Gasparini, A. di Ruocco, and A. -M. Bruyas (Napoli: officine Grafiche Francesco Giannini & Figli s.p.a). Available online at: http://www.unhabitat.org/grhs/2011

Alelah, O. (2017). Factors influencing sustainability of water and sanitation. University of Nairobi, Kenya.

Angeles, L., Guzman, E. B., Escobedo, F. J., and Leary, R. O. (2022). A socio-ecological approach to align tree stewardship programs with public health benefits in marginalized neighborhoods in Los Angeles, USA. Front. Sustain. Cities. 4, 944182. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2022.944182

Arora, S, Shah, D., Chaturvedi, S., and Gupta, P. (2015). Defining and measuring vulnerability in young people. Indian J. Community Med. 40, 193–197. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.158868

Atkinson, R., and Flint, J. (2001). Accessing hidden and hard-to-reach populations: snowball research strategies. Soc Res Updat. 33, 1–4.

Barrett, D., Ortmann, L., Dawson, A., Saenz, C., Reis, A., and Bolan, G. (2015). Public health ethics: cases spanning the globe_vulnerability and marginalized populations. Public Health Ethics Cases Spann. Globe. 3, 203–240. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-23847-0

Barron, G., Laryea-adjei, G., Vike-freiberga, V., Abubakar, I., Dakkak, H., Devakumar, D., et al. (2022). Viewpoint Safeguarding people living in vulnerable conditions in the COVID-19 era through universal health coverage and social protection. Lancet Pub. Health. 7, e86–92. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00235-8

Bazeley, P., and Jackson, K. (2013). Qualitative data analysis with Nvivo. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Beguy, D., Elung, P., Mberu, B., Oduor, C., Wamukoya, M., Nganyi, B., et al. (2015). HDSS Profile: the nairobi urban health and demographic surveillance system. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 462–471. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu251

Bezerra, M., Paulo, J., Suely, K., and Silva, Q. (2013). Support networks and people with physical disabilities: social inclusion and access to health services. 20, 75–84. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232014201.19012013

Bishop, S. (2015). Using water diaries to conceptualize water use in Lusaka, Zambia. Int. E-J. Crit. Geogr. 14, 688–699.

Bright, C. (2017). Defining child vulnerability: definitions, frameworks and groups. London: Children's Commissioner for England Sanctuary Buildings.

Butler, N., Johnson, G., Chiweza, A., Aung, K., Quinley, J., Rogers, K., et al. (2020). A strategic approach to social accountability : bwalo forums within the reproductive maternal and child health accountability ecosystem in Malawi. BMC Health. Serv. Res. 20, 568. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05394-0

Chumo, I., Simiyu, S., Gitau, H., Kisiangani, I., Kabaria, C., Muindi, K., et al. (2021). Manual pit emptiers and their heath: profiles, determinants and interventions, 1–15.

Corburn, J., and Karanja, I. (2016). Informal settlements and a relational view of health in Nairobi, Kenya: sanitation, gender and dignity. Health Promot. Int. 31, 258–69. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dau100

CSDH (2008). Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva. Lancet. 372, 1661–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6

Data Social Determinants, and Better Decision-making for Health: The 3-D commission. J Urban Health. (2021) 98, S4–S14. 10.1007/s11524-021-00556-9.

de Lanerolle, I., Walton, M., and Schoon, A. (2017). Izolo: Mobile diaries of the less connected. Mak. All Voices Count Res. Report. (Brighton: IDS), 31.

Egondi, T., Oyolola, M., Mutua, M., and Elung, P. (2015). Determinants of immunization inequality among urban poor children : evidence from Nairobi' s informal settlements. Int J Equity Health. 14, 24. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0154-2

Emina, J., Beguy, D., Zulu, E., Ezeh, A., Muindi, K., Elung, P., et al. (2011). Monitoring of health and demographic outcomes in poor urban settlements : evidence from the Nairobi urban health and demographic surveillance system. J. Urban Health 88, 200–218. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9594-1

Ezeh, A., Population, A., Oyebode, O., Satterthwaite, D., and Chen, Y. (2016). The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums. Lancet. 389, 547–558. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31650-6

Gale, N., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., and Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

Ii, B. L., Kasperson, R., Matson, P., Mccarthy, J., Corell, R., Christensen, L., et al. (2003). A framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability Science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 100, 8074–8079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1231335100

Kenya, R. (2022). Kenya' s constitution of 2010. National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General, Nairobi, Kenya.

Kibuchi, E., Barua, P., Chumo, I., Teixeira, N., Filha, D., Howard, P., et al. (2022). Effects of social determinants on children' s health in informal settlements in Bangladesh and Kenya through an intersectionality lens : a study protocol. BMJ Open. 12, e056494. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056494

Kohn, N. (2014). Vulnerability theory and the role of government vulnerability theory and the role of government. Yale Journal of Law and Feminism. 26, 1–26.

Kunath, A., and Kabisch, S. (2011). Review and evaluation of existing vulnerability indicators for assessing climate related vulnerability in Africa Article. UFZ-Bericht, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung, No. 07/201.

Lippold, T., and Burns, J. (2009). Social support and intellectual disabilities: a comparison between social networks of adults with intellectual disability and those with physical disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 53, 463–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01170.x

Mberu, B., Haregu, T., Kyobutungi, C., and Ezeh, A. (2016). Health and health-related indicators in slum, rural, and urban communities: a comparative analysis. Glob. Health Action 9, 1–13. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.33163

Mehra, A., Rani, S., Sahoo, S., Parveen, S., Singh, A, Chakrabarti, S., et al. (2020). A crisis for elderly with mental disorders: relapse of symptoms due to heightened anxiety due to COVID-19. Asian J. Psychiatr. 51, 102114. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102114

Muchukuri, E., and Grenier, F. (2009). Social determinants of health and health inequities in Nakuru (Kenya). Int. J. Equity Health. 8, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-8-16

Munyewende, P., Rispel, L., and Rispel, L. (2015). Using diaries to explore the work experiences of primary health care nursing managers in two South African provinces. Glob. Health Action. 7, 25323. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.25323

Mutisya, E., and Yarime, M. (2011). Understanding the grassroots dynamics of slums in nairobi: the dilemma of Kibera informal settlements. Int Trans J Eng Manag Appl Sci Technol. 2, 197–213.

Rice, B., Boccia, D., Carter, D., Weiner, R., Letsela, L., Wit, M., et al. (2022). Health and wellbeing needs and priorities in mining host communities in South Africa : a mixed-methods approach for identifying key SDG3 targets. BMC Public Health. 22, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12348-6

Rifai, D., Mosaad, G, and Farghaly, Y. (2016). Urban framework as an approach towards health equity in informal settlements. WIT Transactions on Ecology and The Environment. 210, 87–98. doi: 10.2495/SDP160081

Roelen, K., and Sabates-Wheeler, R. (2012). A child-sensitive approach to social protection: Serving practical and strategic needs. J. Poverty Soc. Justice 20, 291–306. doi: 10.1332/175982712X657118

Sarma, M., and Pais, J. (2008). Financial inclusion and development: a cross country analysis. Annu. Conf. Hum. Dev. Capab. Assoc. New Delhi. 168, 1–30.

Satterthwaite, D. (2018). Environment and urbanization. Editorial: A new urban agenda? A new urban agenda. 1–10. doi: 10.1177/0956247816637501

Sepúlveda, M., and Nyst, C. (2012). The human rights approach to social protection. Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. p. 1–72. Available online at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2114384

Shiba, K., Kondo, N., and Kondo, K. (2016). Informal and formal social support and caregiver burden : the AGES caregiver survey. J. Epidemiol. 26, 622–628. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20150263

Thaly, D. (2021). Data must speak: guidelines for community engagement and social accountability in education. UNICEF. 1, 1–37.

Tkacz, N. (2021). Data diaries: a situated approach to the study of data. Big Data Soc. 2021, 8. doi: 10.1177/2053951721996036

UN Habitat (2022). Envisaging the future of cities. United Nations Human Settlements Programme, Nairobi, Kenya.

UNICEF (2018). Shaping urbanization for children a handbook on child-responsive urban planning. New York, NY.

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2016). UN-habitat support to sustainable urban development in Kenya. 4, 1–21.

Wairiuko, J., Cheboi, S., Ochieng, G., and Oyore, J. (2017). Access to healthcare services in informal settlement: perspective of the elderly in Kibera Slum Nairobix-Kenya. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 7, 5–9.

Williams, D., Costa, M., Sutherland, C., Celliers, L., and Scheffran, J. (2019). Vulnerability of informal settlements in the context of rapid urbanization and climate change. Environ. Urban. 31, 157–176. doi: 10.1177/0956247818819694

World Health Organization (2003). Determinants of health the solid facts. 2nd ed. World Health Organization, Geneva. Available online at: http://www.euro.who.int/_data/assets/pdf_file/0005/98438/e81384.pdf

World Health Organization (2020). Disability considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak COVID-19. WHO reference number: WHO/2019-nCoV/Disability/2020.1.

Keywords: vulnerability, marginalized and vulnerable groups, governance diaries, qualitative study approach, Nairobi, Kenya

Citation: Chumo I, Kabaria C, Shankland A and Mberu B (2023) Drivers of vulnerability to health and wellbeing challenges in informal settlements. Front. Sustain. Cities 5:1057726. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2023.1057726

Received: 29 September 2022; Accepted: 09 January 2023;

Published: 03 February 2023.

Edited by:

Remus Cretan, West University of Timişoara, RomaniaReviewed by:

Mihai S. Rusu, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, RomaniaOlumuyiwa Adegun, Federal University of Technology, Nigeria

Boglárka Méreiné-Berki, University of Szeged, Hungary

Copyright © 2023 Chumo, Kabaria, Shankland and Mberu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ivy Chumo,  aXZ5Y2h1bW9AZ21haWwuY29t

aXZ5Y2h1bW9AZ21haWwuY29t

Ivy Chumo

Ivy Chumo Caroline Kabaria1

Caroline Kabaria1