- Dahdaleh Institute for Global Health Research, York University, Toronto, ON, Canada

Interest in resilience and vulnerability has grown remarkably over the last decade, yet discussions about the two continue to be fragmented and increasingly ill-equipped to respond to the complex challenges that systemic crises such as climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic pose to people, places, and the planet. Institutional interventions continue to lag behind, remaining predominantly focused on technocratic framings of vulnerability and resilience that do not lead to a more robust engagement with the reality of the changes that are underway. This paper provides a blueprint for facilitating intersectional resilience outcomes that ensure that as a society we are not merely surviving a crisis, but are committing to interventions that place equity, solidarity, and care at the center of healthy adaptation and wellbeing. First, it traces the evolution of resilience from a strictly ecological concept to its uptake as a socio-ecological framework for urban resilience planning. Next, it argues that current framings of vulnerability should be expanded to inform interventions that are locally relevant, responsive, and “bioecological.” The integrative resilience model is then introduced in the second half of the paper to challenge the scope of formal resilience plans while providing an entry point for renewed forms of resistance and recovery in the age of neoliberalism-fueled systemic crisis. The three pillars of the model are discussed alongside a selection of scalable and adaptable community-driven projects that bring this approach to life on the ground. By being rooted in lived experience, these innovative initiatives amplify and advance the work of frontline communities who are challenging and resisting the neoliberalization not only of urban governance and resilience, but of wellbeing and (self-) care more broadly.

Introduction

While in the past 3 years calls for recovery and transformation have been at the heart of virtually every strategic plan advanced by governmental and multilateral actors, formal interventions continue to remain focused on outdated framings of vulnerability and resilience that are conceptually ill-equipped to address the interconnected nature of the crises that confront us today. Scholars warn that the infiltration of neoliberal interests into the definition and operationalization of resilience does not reduce vulnerability, at best it enhances the capacity of communities to endure it (Slater, 2014; Derickson, 2018; Jon, 2021). Others caution against the coupling of resilience with social innovation, a discourse and a practice that is increasingly invoked by institutional actors eager to facilitate a swift transition to “post”-pandemic and climate-proofed futures. Premised on the idea of “disruption,” social innovation has been criticized for co-opting the language of social movements to gain support for interventions that “act as a catalyst to push neoliberal policies further in society by deploying ‘new ideas that work' based on a certain construction of the problem” (Fougère and Meriläinen, 2021, p. 4).

Institutional plans such as those for climate resilience and Covid-19 recovery can be considered “structures of selective attention” (Forester, 1980, p. 276) through which economic and political elites preemptively frame important concepts to pursue beneficial agendas. This subtle yet pervasive form of influence—what McCann (2017) calls “definitional power”—is consistent with Gramsci's idea of “hegemony through neutralization” (Routledge et al., 2018), a process through which the very construction of the problem determines the scope of its attendant solutions. Today, “official” resilience plans advance a strategically narrow idea of vulnerability that “collapses the political realm into the technocratic realm” (Derickson, 2018, p. 431) by reinforcing the idea that to be resilient is to “bounce back” to the status quo. As I document elsewhere, their “infrastructure-first” approach presumes that if buildings and the economy are kept safe, then residents will be kept safe as a result (Camponeschi, 2021). Similarly, because formal plans overwhelmingly exclude losses not easily quantified in monetary terms from their scope of concern, their engagement with the health dimensions of the climate crisis is marginal, particularly by neglecting to account for experiences of trauma and mental health impairment that systemic crises often entail (Cianconi et al., 2020; Cunsolo et al., 2020; American Psychological Association, 2022; Camponeschi, 2022). Institutional plans suffer from two additional shortcomings: a focus on the global scale of the problem often neglects and dismisses the local level, where lived experience manifests. As a result, institutional actors continue to advance interventions that are divorced from place-based needs and experiences, an outcome that is exacerbated by a focus on neoliberal agendas, which means that planners are often reluctant to engage residents in the project of articulating “alternative” visions for community resilience. This, in turn, results in “profound damage to democratic practices, cultures, institutions and imaginaries (Routledge et al., 2018, p. 78).” Secondly, they continue not to integrate emerging concepts such as systemic risk and planetary health into their analysis, which means that while “cities in many regions have responsibility for functions affecting population wellbeing (Sheehan et al., 2022, p. 2)” to this day there is still “no major global city climate network organized around population health outcomes and public health interventions (Sheehan et al., 2022, p. 12).”

DeVerteuil (2015) argues that violence is still “insufficiently conceptualized and disconnected from wider currents and debates in the social sciences (DeVerteuil, 2015, p. 216),” and insists we must shed light on the ways in which structural violence “acts as a vehicle to implicate the state's crucial role in health promotion or denial (DeVerteuil, 2015, p. 217).” In his analysis, violence becomes institutionalized through poverty, inequality, and discrimination, influencing collective health and preventing people from meeting their basic needs. In this sense, the selective attention of institutional plans and narratives perpetuates several forms of harm: from the “slow violence” (Nixon, 2013) that validates certain needs over those of others, to the “necropolitics” of “letting die” (Sandset, 2021). These are forms of vulnerability that do not command the same urgent collective attention as acute crises do, but are nevertheless manifestations of “ethical loneliness” (Stauffer, 2018), forms of stealth violence that arise from not being seen and heard in one's needs and experiences. The increasingly neoliberal and technocratic nature of strategic plans therefore contributes “not only to epistemological injustice, but also to very real violence played out over time as a result of any number of climate–related policies” (O'Lear, 2016, p. 7).

Whether in the face of a climate or health emergency, frontline communities play a crucial role in creating parallel structures of care that repair the harms caused by official inattention. These are communities that “do not wait for the state, or allow capital to take the initiative, but instead “negotiate with their hands” (Jon and Purcell, 2018, p. 238) to heal themselves and subverting top-down expectations of “responsibilization” (Keil, 2009) through the articulation of different values, narratives, and approaches to resilience. As I document in this paper, their organizing is truly powerful and innovative, confirming bell hooks' intuition that marginality is much more than a site of deprivation, “it is also the site of radical possibility, a space of resistance (Hooks, 1989, p. 20).” Nevertheless, their contributions continue to operate outside the formal and sustained attention even of academic researchers. Calls for radical resilience have been appearing more frequently in academic literature (Biermann et al., 2016; Fainstein, 2018; Goh, 2021), yet radical resilience itself remains undertheorized, and “we have fewer instances where those ideas are linked to concrete cases in a way that can help draw specific lessons that could be useful for planning practice” on the ground (Jon and Purcell, 2018, p. 237). Similarly, most community-engaged research is often in relation to moments of acute crisis, meaning that we are still not “able to hear the voices of those forced to live with disruption long after the disruptive event” is over (Harvey, 2007, p. 863), or learn what is required to support and sustain resilience in daily life.

In response, I couple the concept of “integrative resilience” (Camponeschi, 2022) with examples of community-driven initiatives from around the world to: more accurately name and assess experiences of vulnerability in all of their complexity; validate the needs and contributions of frontline communities; and call for the design of “infrastructures of care” to invest in the provision of resources necessary to facilitating equitable outcomes in daily life and at times of acute need. I agree with O'Lear (2016, p. 5) that “reliance on grand narratives of mathematical, natural science erase or significantly discount the presence of humans and hide uneven power and social relations rooted in neoliberalism.” This paper contributes to naming and identifying what is obscured and invalidated by dominant narratives of resilience and vulnerability, and offers entry points to guide the design and implementation of more equitable interventions rooted in relationality and care. Rather than following technocratic scripts organized around “innovation and the mining of hope” (Hobart and Kneese, 2020, p. 10), a focus on care and solidarity entails “a repoliticization of climate instead of the depoliticized techno-economist utopias that never deliver (Sultana, 2022, p. 2).” With an explicit commitment to amplifying practical solutions to inspire both policy change and community-engaged scholarship, this paper: (1) contributes to a more robust engagement with “radical” resilience in both theory and practice; (2) connect the dots between integrative resilience and concepts such as systemic risk and planetary health; (3) brings a much-needed focus on the (mental) health impacts of systemic risks to formal action plans, so as to expand their scope of concern beyond the context of acute crisis; and (4) offers research and policy prompts that provide the necessary scaffolding to guide the design and implementation of “multisolving” (Sawin, 2018) interventions in pursuit of healing justice. While in this paper the integrative resilience model is applied to the context of climate resilience and Covid-19 recovery, this is a responsive and scalable approach that can be leveraged in a variety of settings where adaptation, equity, and wellbeing coalesce—one that I am confident will only become more relevant in the years to come.

Literature review: The limits of socio-ecological resilience thinking

The root of the word resilience can be traced to the Latin resalire, which translates as walking or leaping back (Gunderson, 2010). Since the 1973 publication of Holling's (1973) paper Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems, the concept has been steadily gaining the attention of academics and non-specialized audiences in a variety of settings. This interest can perhaps be explained by resilience's potential to facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration in “managing a transition toward more sustainable development paths” (Folke, 2006, p. 260). As a metaphor, resilience is also a way of thinking about the future, having a “futuristic dimension” (Manyena, 2006, p. 439) that can stimulate new forms of learning and adaptation. In its broadest sense, then, the concept can be defined primarily in one of two ways: as a desired outcome, or as a process to achieve a desired outcome (Southwick et al., 2014).

Within ecological literature, resilience has undergone several evolutions. Early theorizations of the concept assumed that, following a disturbance, nature would “self-repair” based on an implicitly “stable and infinitely resilient environment where resource flows could be controlled” (Folke, 2006, p. 253). This “engineering” view of resilience considered ecological systems as existing in a single equilibrium. In this sense, what constituted resilience was the “return time” required to bring a system back to its original state (Pimm, 1991). In later years, the concept of an “ecological” resilience was introduced by Holling (1996) to describe systems that may not return to their previous equilibrium but instead reconfigure into a different form of organization. From this perspective emerges the popular definition of resilience as the amount of disturbance that a system can absorb before tipping into a new state (Walker et al., 2004). From this vantage point, systems are not predictable and mechanistic but rather complex and adaptive. This means that they are understood to be process-dependent, with feedbacks among multiple scales influencing their ability to self-organize.

Gunderson and Holling's concept of panarchy (Gunderson and Holling, 2002) illustrates the trajectories that shape these feedbacks. Their heuristic model is composed of four phases of development: exploitation, conservation, release, and renewal. The exploitation phase is characterized by a period of exponential change that eventually leads to stasis (conservation), followed by periods of readjustment (release), and re-organization (renewal). As a set of hierarchically structured scales, the four stages are interconnected and equally important. Folke (2006), however, remarks that processes of release and re-organization have mostly been ignored in policy realms in favor of an emphasis on the first two. For example, in documents such as municipal climate plans the widespread use of terms such as “coping,” “bouncing back,” and return to “normal” suggests and reinforces a reactive stance to change by keeping the focus on exploitation and conservation. This translates most often into a view of resilience as the ability of social systems to withstand external shocks to their social infrastructure more than on their ability to respond to a disturbance by questioning and transforming the status quo itself. A disturbance, however, can unleash the potential for debate and transformation. For this reason, many have argued that resilience should be far more than the ability to cope or to bounce back. It should be a process that is centered around “people's aspirations to be outside of the high-risk zone altogether” (Manyena, 2006, p. 438).

As the last point alludes to, it is not just ecological systems that demonstrate resilience—individuals, communities, and nations can also organize to respond to change. Local adaptation strategies, cultural heritage, and different forms of experiential knowledge are all important factors that influence adaptive capacity on the ground. The term “social-ecological systems” has been introduced in the literature precisely to acknowledge the role that social agents play in influencing the trajectory of resilience (Adger, 2000; Anderies et al., 2004; Olsson et al., 2004; Walker et al., 2004) as well as to stress that the delineation between ecological and social systems is “artificial and arbitrary” (Folke, 2006, p. 262).

Connecting analyses of ecological change to their interrelated social dynamics has contributed enormously to shaping the direction of climate action, particularly by recognizing cities as social-ecological systems in their own right. In their climate plans, municipalities increasingly adopt systems thinking in an attempt to account for the complexities of climate impacts. Many of them recognize that cities are linked to ecological systems across multiple scales, for example, through the production and distribution of food or the global provision of energy. They also acknowledge that cities rely on infrastructures of service delivery in order to function efficiently, as well as on networks of social agents and institutions to manage their day-to-day operations. Indeed, literature on social-ecological systems agrees on the centrality of individuals, networks, and institutions to inform the capacity of complex urban systems to self-organize, learn, and adapt. The Resilience Alliance (2010), a consortium of researchers that stimulates interdisciplinary science using resilience as an overarching framework, identifies four key factors that affect socio-ecological resilience planning at the municipal level: metabolic flows, governance networks, social dynamics, and the built environment. In its idealized form, this framework: (1) strengthens systems to reduce their exposure and fragility to ecological threats; (2) builds the capacity of social agents to develop adaptive responses; (3) creates the conditions for supportive institutional mechanisms that facilitate the ability of agents to take action, and (4) takes into account the interconnections between all the above (Manyena, 2006).

Nevertheless, many have criticized the ways in which social-ecological resilience has been operationalized in cities to date. While resilience in municipal plans is typically presented as a positive, desirable, and necessary attribute, some challenge its top-down, value-neutral rhetoric for excluding non-“expert” knowledge from formal consideration (MacKinnon and Derickson, 2012; Fainstein, 2018; Brantz and Sharma, 2020; Goh, 2021). Here, a common critique that is leveled against current resilience planning processes is that a lack of critical engagement with issues of inclusion, power, and injustice is leading to problematic policies that do not give adequate space and legitimacy to local needs and experiential knowledge (Cretney, 2014; Dubois and Krasny, 2016; Lindroth and Sinevaara-Niskanen, 2016; Angelo and Wachsmuth, 2020). Such exclusion is seen as a strategy to silence those voices that diverge from institutional understandings of (and priorities for) urban resilience planning, often exacerbating the already uneven impacts of urban development on marginalized populations (Hodson and Marvin, 2010; Middlemiss and Parrish, 2010; Jon, 2021). Indeed, while resilience has been the subject of increasing academic debate and critique, vulnerability remains an under-theorized and often misunderstood component of resilience planning. As Lebel et al. (2006) argue, at present “the discourse of managing resilience or vulnerability is subject to its own peculiar forms of politics rooted in relatively narrow ecological reasoning that has impacts on who participates and how.”

Municipalities have been criticized for not adequately responding to the complexities of systemic risks by working with a limited conceptualization of resilience that largely discounts how questions of socio-economic inequality, political accountability, and community participation influence overall vulnerability (Joseph, 2013; Schmeltz et al., 2013; Diprose, 2014; DeVerteuil and Golubchikov, 2016). To assess the effectiveness and relevance of their interventions, it is therefore crucial to first understand how institutional actors frame their understandings of resilience, vulnerability, and participation. When these terms are invoked, who is seen as a legitimate stakeholder? Who benefits from formal interventions, and how are community-based needs accounted for? The next section picks up on these questions by arguing that the way that vulnerability is engaged with in institutional spaces should be expanded along “bioecological” lines to facilitate truly responsive, locally relevant, and “integrative” responses to systemic crises such as climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic.

A “bioecological” reading of vulnerability

While vulnerability and resilience research overlap to some degree, Tyler and Moench (2012, p. 317) warn that there is still “little consistency or consensus on definition” in the ways the two are engaged across several disciplines and fields. These differences are perhaps best explained by the terms' differing origin in the literature: “resilience has emerged from a positivist biophysical scientific perspective, while vulnerability has been described mainly from a constructivist social science and political ecology framework” (Tyler and Moench, 2012, p. 317). At the same time, as Watts and Bohle (1993, p. 45) argue, the relationship between vulnerability and resilience still “does not rest on a well-developed theory; neither is it associated with widely accepted indicators or measurements.” As Manyena (2006, p. 439) asks, “is resilience the opposite of vulnerability? Is resilience a factor of vulnerability? Or is it the other way around?”

In the context of climate planning, for example, the overwhelming majority of municipal governments frame their action plans around a view of vulnerability that places the concept in an inverse relationship with resilience, where low resilience is believed to result in a higher degree of vulnerability and vice versa (Gallopín, 2006). Foundational to their approach is the belief that lowering exposure to natural hazards by fortifying the built environment increases the resilience of a city as a whole, thus making it less vulnerable to climatic events. This view is reinforced by how municipalities scope their action plans: these documents commonly limit their assessment of risk to weather-related events, and typically restrict it further by focusing on the primary forms of ecological vulnerability—such as flooding and heat waves—that are identified as being most problematic for each city. Even in this case, however, institutional actors refer to hazards and risks in abstract terms, choosing to focus on their potential to act as a “stressor” or as a “disturbance” on systems and rarely with a grounded analysis of how they would affect the lives of people on the ground. To this day, most municipal plans purposefully do not take into account other forms of vulnerability and loss—such as: “more comprehensive health impacts” and personal losses—that might arise as a result of exposure to such disruptive events (see, for example, Camponeschi, 2021). For this reason, some warn that the narrow conceptualization of vulnerability as a primarily ecological matter limits the focus of municipal interventions in ways that, at best, reduce “the vulnerability of those best able to mobilize resources, rather than the most vulnerable” (Adger, 2006, p. 277).

In response, scholars of social resilience argue that any meaningful policy must be able to identify the mechanisms contributing to a community's exposure to risks and intervene to reduce the causes of social—not just ecological—vulnerability. They contend that vulnerability must be conceived of not only in relation to exposure to climate or health hazards, but also to the pre-existing “social frailties” (Manyena, 2006, p. 436) that influence local adaptive capacity. These pre-existing conditions may include factors such as socio-economic status, gender, and ability, all of which have been found to contribute to the differential vulnerability of some groups by determining access to services and forms of socio-economic support that shape and constrain the overall resilience of a community (Norris et al., 2008; Hoffman and Kruczek, 2011; DeCandia and Guarino, 2015). The role of local governments and of community organizations is therefore crucial because resilience is supported by high-capacity agents who are enabled by supportive institutions, who together determine the availability and success of prevention strategies and response services (Tyler and Moench, 2012).

Critical scholarship on vulnerability has been instrumental in bringing a more nuanced analysis to the way resilience is planned for in cities, insisting that “vulnerability is driven by inadvertent or deliberate human action that reinforces self-interest and the distribution of power in addition to interacting with physical and ecological systems” (Adger, 2006, p. 270). For some, creating mechanisms for the promotion of participatory assessments could serve as a key strategy to include the voices of marginalized populations into the resilience planning process (Adger, 2003; Krishnamurthy et al., 2011; Pringle and Conway, 2012; Wilk et al., 2018). In the fields of disaster risk reduction and public health, for example, participatory assessments are considered to be an integral part of meaningful adaptation because they help paint a more accurate picture of which subpopulations are most exposed to risk and what could in turn help mitigate their vulnerability (van Aalst et al., 2008; Pfefferbaum et al., 2015). Nevertheless, municipal governments continue to struggle to include a well-rounded definition of vulnerability in their resilience plans, and participatory assessments rarely inform the scope of their interventions. To this day, most of them also fail to provide responses that are commensurate with the multilevel impacts of systemic crises, particularly for what concerns questions of health and wellbeing. For example, municipal plans still largely do not recognize the interplay between physical and mental health, nor do they integrate “One Health” or planetary health (World Health Organization, 2017; UNFCCC, n.d.) approaches to their strategic plans. Scholars in the fields of community psychology as well as activists in the healing justice movement, on the other hand, center their analysis on an “ecological” view that directly challenges static and technocratic framings of vulnerability and resilience (Engel, 1977; Berzoff, 2011; Melchert, 2015; Cox et al., 2017).

The “ecological turn” of community psychology (Harvey, 1996) emphasizes the interdependence of individuals and the communities to which they belong. As Harvey explains (2007, p. 16): “community psychologists share with field biologists the premise that organisms live (i.e., survive, thrive, or decline) in interdependence with their environments.” Rather than framing resilience as a value-neutral, technocratic process, this “resource perspective” sees resilience “as transactional in nature, evident in qualities that are nurtured, shaped, and activated by” (Harvey, 2007, p. 17) people's embeddedness in complex and dynamic social contexts “that are themselves more or less vulnerable to harm, more or less amenable to change, and apt focal points for intervention” (Harvey, 2007). This interdependence brings to life the ways in which the impacts of a disturbance do not begin and end with an individual alone but rather interact with the broader context (i.e., “ecosystem”) within which they occur. As a result, the “ecological analogy” (Trickett, 1984; Kelly, 1986) can be especially powerful in the context of urban resilience planning because what constitutes an ecological threat is considered from a more expansive perspective. Rather than conceiving of disturbances strictly from the lens of environmental risks and hazards, here it's any political, socio-economic or relational factor that restricts the flow of resources between an individual and their environment that is considered a threat, because it can weaken the ability of communities to foster health and resilience among their members (Prilleltensky, 2012; Chavez-Diaz and Lee, 2015; Ginwright, 2015).

Bronfenbrenner and Ceci's “bioecological” model (Bronfenbrenner and Ceci, 1994) takes this view one step further by identifying five nested systems through which these exchanges occur, explicitly connecting them to their influence on human health and development over time. These systems include: the biophysical (individual) level, which encompasses physiological factors that determine one's predisposition to health and resilience; the microsystem level, which is made up of the systems that most intimately and directly influence an individual's life, such as connection to family, friendship bonds, and neighborhood affiliations; exosystems such as healthcare, welfare, and education through which formal resources most commonly flow; macrosystems, which are made up of the societal norms, sociopolitics, and economic beliefs that create the larger cultural context within which resource exchanges are justified and prioritized; and, lastly, chronosystems, which reflect the trajectory of personal and collective adaptations (and their influence on health and wellbeing) over time. All five of these systems are foundational to meeting the biopsychosocial needs of individuals over their lifespan, and form the context through which vulnerability to systemic risks and the merit of resilience interventions could be evaluated in cities.

Applied to the municipal context, this view of vulnerability brings to life the ways in which successfully responding to a disturbance means going beyond economic priorities and “infrastructure-first” approaches (Camponeschi, 2021), explicitly committing to resourcing the very infrastructures of care that facilitate wellbeing, empowerment, and healing in everyday life instead. Indeed, to conceive of resilience as a process that goes beyond flood prevention or emergency medical response is a powerful way to assert that we live in a state of “shared precarity” (Butler, 2004) with one another, to acknowledge that risks and hazards do not affect only the built environment or economic portfolios but can equally impact individuals, communities, and more-than-human life. The healing justice movement discussed below has been instrumental in leveraging this bioecological lens to legitimize the needs and experiences of equity-seeking communities, advocating for the allocation of resources and the provision of services that directly nurture and expand these infrastructures of care. This is a process that entails “building robust structures in society that provide people with the wherewithal to make a living, secure housing, access good education and health care, and realize their human potential” (Southwick et al., 2014, p. 6).

The section that follows introduces the concept of integrative resilience as means of uniting these various threads into a cohesive framework for researchers and practitioners of resilience. In addition to highlighting the connections between ecological, bioecological, and social-ecological approaches, the integrative model contributes an additional dimension to the work of advancing equitable resilience outcomes by explicitly adding a trauma-informed lens to proposed municipal interventions. As a framework, it serves as a bridge between diverse disciplines and practices, and contributes to the formulation of more comprehensive policies and services that create the conditions for structural care as opposed to insisting on individualized resilience as a means (or the only means) of surviving a crisis.

The three pillars of integrative resilience

Risks and hazards are becoming increasingly systemic, meaning that their effects often ripple out to affect communities and infrastructures far beyond the point of origin of a disturbance (Pescaroli and Alexander, 2019). In under 2 years, for example, the coronavirus pandemic has made abundantly clear the many ways in which our health and wellbeing are not separate from that of people who surround us, that of the environment we live in, and that of the systems we depend on for the optimal functioning of day-to-day life. In many ways, Covid-19 has helped shift public consciousness toward a more nuanced and complex understanding of vulnerability, one that recognizes that exposure to an emerging infectious disease is not the only health hazard we face: so are poverty, isolation, and other pervasive forms of inequality that have resulted from years of neoliberal governance (Slater, 2014; Kaika, 2017). Addressing the impacts of systemic crises such as climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic therefore requires a cohesive and responsive framework that ensures that risks and opportunities are distributed fairly across diverse populations—especially in light of their pre-existing needs and vulnerabilities.

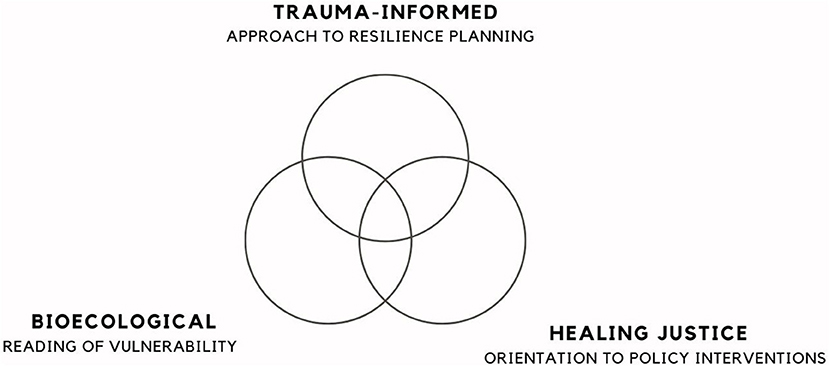

Systemic risk events reverberate and cascade across a multitude of scales, which is why responses must be multilevel as well. The integrative resilience model connects current debates about social-ecological resilience and critical urban scholarship with contributions from community psychology, trauma studies, and planetary health to call for more robust and locally relevant support before, during, and after a disturbance. The section that follows provides an overview of its three key pillars (Figure 1) to highlight their relevance and urgency in the context of resilience planning and social transformation.

Figure 1. The integrative resilience model (Camponeschi, 2022).

Trauma-informed approach to climate planning

Climate change is increasingly recognized as a public health issue (Martinez et al., 2020; American Psychological Association, 2022). On a warming planet, researchers warn of the rise of a range of physical ailments such as asthma, heat stress, and more frequent viral outbreaks that will pose significant risks to individual and collective wellbeing in the years to come (IPCC, 2021; Watts et al., 2021). At a time of systemic crises and rampant inequality, trauma is also increasingly seen as an issue of concern for public health, in large part thanks to emerging research that is transforming our understanding of how the interplay between physiological and psychological distress can affect human health and development (Levine, 2010; van der Kolk, 2014). Nevertheless, little research exists that directly investigates the relationship between climate change and trauma. Recognition is slowly growing for the mental health dimensions of climate change, particularly instances of eco-anxiety, grief, and depression that are affecting a growing number of people worldwide (Cianconi et al., 2020; Clayton, 2020). For example, the work of health geographers such as Ashlee Cunsolo has contributed enormously to exposing the reality of ecological grief and how it is disrupting attachment to place, sense of identity, and psycho-emotional health among affected communities (see, for example, Cunsolo et al., 2020).

At the same time, studies that explicitly connect climate change and trauma remain few and mostly focused on disaster recovery (Galea et al., 2005; Leitch et al., 2009; Schmeltz et al., 2013; Schulenberg, 2016). Typically, they do not acknowledge that structural inequality is in itself a traumatizing experience that can unfold not just acutely but also incrementally in everyday life (for an exception, see Paine, 2019, 2021). Similarly, when trauma is acknowledged, it is primarily treated as a personal medical experience disconnected from the broader socio-economic structures from which it originates.

Trauma-informed care is an approach that recognizes that if policy mechanisms provide uneven opportunities for healing in the population (particularly by not taking into account the bioecological nature of vulnerability) then recovery is going to be a longer, more arduous process, one that may include significant deterioration as a result of protracted exposure to stress. A trauma-informed lens is especially timely to conversations about resilience and recovery because it provides valuable guidance on how to more accurately name and validate experiences of vulnerability in all of their complexity, and helps identify invest in resources that can help to mitigate their impacts along equitable, accessible, and inclusive lines. While still a niche practice in some regards, trauma-informed care is steadily being employed to guide the provision of frontline services, particularly in the context of houselessness, sexual abuse, and addiction recovery. Its principles are also gradually gaining prominence in the public education sector, especially as more is learned about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and their intergenerational ramifications (Burke-Harris, 2018).

Healing justice orientation to policy making

Healing justice is a small but promising field that is informing intersectional activism around the world, yet remains under-theorized and under-discussed in academic literature. As a social movement, its aim is to legitimize the needs and experiences of marginalized populations by advocating for the allocation of resources that can restore health while creating systems change (Southwick et al., 2014). At the core of this work is the view that healing is more than an act of individual self-care but rather a political process through which people and communities can reclaim wholeness and seek empowerment by tackling the root causes of maladaptive interventions (Chavez-Diaz and Lee, 2015; Ginwright, 2015). For many equity-seeking communities, the impacts of these interventions are often intergenerational, causing profoundly traumatic effects across a continuum that extends from the school-to-prison pipeline (American Civil Liberties Union, n.d.) to genetic expression (Yehuda and Bierer, 2009; Voisey et al., 2014). For this reason, healing justice advocates understand that prolonged exposure to trauma and systemic oppression not only limits a sense of agency—it also crucially undermines trust, hope, and belief in the possibility for change, thus reinforcing the status quo. As a result, they call for the design of solutions that aren't simply a one-off intervention but are rather part of a larger mandate to calibrate responses to evolving needs and shifting ecological priorities, thus repairing the disconnect between socio-economic and environmental vulnerability that currently influences mainstream framings of resilience.

With their activism, healing justice advocates help communities and institutions “think about the diversity of caring needs and practices in our society and try to create social institutions congruent with that diversity (Tronto, 2015).” Their work also provides a bridge between bottom-up resilience planning and top-down responses, particularly by demanding a more equitable distribution of power in the interactions between communities and institutions. Indeed, because care has always been central to social movements, healing justice is inherently coalition-building work, at once an “interstitial strategy” that gives rise to “new forms of social empowerment beyond the state” and a “symbiotic strategy” of collaboration with the state, which is pushed to deepen the scope and reach of its interventions (Routledge et al., 2018, p. 80). In other words, the state “might be reconfigured to be more responsive to local or localized interventions while still providing the necessary architecture for coalition building across scales of governance and disparate geographies” (Routledge et al., 2018).

In this way, power-sharing and coalition-building have the potential to become a mediating space between institutions and residents as well as between local and multilevel scales. This dynamic interplay, in turn, allows for a departure from the status quo, allowing residents to draw from “alternative global imaginaries to bring about social, economic and environmental justice (Routledge et al., 2018, p. 84).” Through listening and power-sharing the state could similarly facilitate a more equitable redistribution of resources by supporting and investing in a “responsive architecture for solidarity and shared governance at a range of scales (Routledge et al., 2018, p. 79),” which the concept of infrastructures of care proposed in this paper represents. The latter, discussed in greater detail below, is not only a discursive form of resistance to the current ‘infrastructure-first' approach espoused by most institutional resilience plans today, but is also a practical way to make those institutions more caring themselves.

Bioecological reading of vulnerability

As discussed earlier in this paper, critiques that brilliantly connect the rise of resilience planning to the neoliberalization of municipal and environmental governance are not lacking in social science literature (Keil, 2014; Angelo and Wachsmuth, 2020; Goh, 2021; Jon, 2021). At the same time, these debates still do not give adequate space to the climate crisis and its roots in neoliberal and extractivist agendas, nor to their implications for the health of the body and that of the body politic (Sultana, 2022). Similarly, in social-ecological literature, conversations that expose the links between socio-economic vulnerability and systemic risk are growing, yet recommendations for interventions do not generally advocate for systems change in a way that connects structural inequality with planetary health agendas or the demands of social movements. In contrast, the bioecological lens contributes to legitimizing and supporting community-driven approaches to resilience and recovery that, to date, remain largely excluded from formal consideration, all the while expanding the limited scope of current interventions by repoliticizing the resilience planning process.

At the heart of this repoliticization is an explicit commitment to challenging the epistemic violence inherent in technocratic discourses of resilience and vulnerability. This is a process that requires shifts in our collective imaginaries and obligations, starting with questioning “critical geopolitics of knowledge production as well as re-evaluating expertise and experts (Sultana, 2022, p. 8).” In other words, interrogating “who is invited to speak, who is heard, and who helps set agendas (Sultana, 2022)” in today's calls for resilience, recovery, and societal transformation. A bioecological reading of vulnerability helps re-centers the lived experience of frontline communities by “listening through the roars, whispers, and silences that exist (Sultana, 2022)” in today's institutional plans while taking into account the rich and dynamic needs, aspirations, and strengths of frontline communities. From this perspective, we can begin to challenge our assumptions about what causes harm, how we design our interventions, and what our benchmarks are for establishing safety, wellbeing, dignity, and health. Indeed, a bioecological lens offers alternative entry points for assessing, monitoring, and responding to the intersectional dimensions of vulnerability, in the process opening up a space for leveraging more accurate benchmarks and tools through which to evaluate the effectiveness of formal response mechanisms on the ground.

Together, the three pillars at the heart of the integrative resilience approach three pillars of integrative resilience connect disciplines and practices that have much to contribute to the conversation about transformative change but that continue to largely be kept separate in both policy and academic realms, such as: community psychology, trauma studies, care and disability studies, and more. Informed by the bioecological lens, the integrative resilience model explicitly positions trauma as a central piece (and outcome) of disruption, and is the first to connect these dimensions to a discussion of healing justice in the context of resilience planning. A healing justice orientation to the design and implementation of policies and services reveals how neoliberal values have constrained and, in many ways limited, the scope of municipal plans, calling instead for the “resourcing” of resilience through the provision of attuned services and adequate (financial, material, and relational) resources through the lens of infrastructures of care.

Nurturing infrastructures of care through structural interventions doubles as an avenue to demand the integration of wellbeing, environmental justice, and the right to the city into the very definition, process, and evaluation of resilience planning on the ground. Indeed, what makes the emphasis on healing so transformative is that if bouncing back is not the endpoint of being resilient, but rather promoting equity and wellbeing are, then resilience planning becomes an avenue through which to ask critical questions about the push to “bounce back” to the status quo in the first place—for example, by asking which values the mainstream culture is promoting, how they play out spatially and materially, and who gets to benefit the most from them.

Combined with their already strong climate change projections and economic/infrastructural plans, an integrative approach to resilience would be a formidable complement to existing municipal climate plans. It could provide tangible tools and metrics to help keep institutions accountable and strengthen the demands of local social movements, making equity and wellbeing the primary outcomes—and standards—of successful climate adaptation. The integrative model invites policymakers, healthcare professionals, planners and other actors to consider the relational and multilevel ways in which all aspects of a community or city's life would be affected by events that they already call disruptive, working for system-level change so that policies and programs are designed with empowerment in mind rather than perpetuating barriers to access or causing re-traumatization. The second half of the paper introduces a handful of participatory initiatives that bring this model to life, providing an example of how institutional actors could, in partnership with frontline actors themselves, intervene to support, finance, and scale integrative responses in the communities they serve.

Methodology

The initiatives introduced in the next section originate from a community-placed research project that sought to interrogate how narratives of resilience and vulnerability are framed, legitimized, and circulated in cities (Camponeschi, 2021, 2022). The project aimed to understand whose experiences and interests are prioritized in formal plans and how representative they are of local needs and aspirations. To do so, it relied on an interdisciplinary approach that was grounded in mixed methods such as key informant interviews, site visits, and participatory workshops in two case study cities, Copenhagen and New York, as well as in a systematic review of their official climate action plans. This review, in turn, was complemented by a background analysis of the climate plans of an additional eight cities in Europe and North America1 to better locate the efforts of Copenhagen and New York City within the broader context of municipal climate action.

The scope of previous articles did not allow for a dedicated focus on the contributions of the many community-driven initiatives uncovered during the course of this work—and that have continued to emerge following the Covid-19 pandemic. They are presented here in the hope of offering a concrete entry point for the work of operationalizing the integrative resilience model in cities around the world. These adaptable and adaptive interventions range from participatory disaster recovery to climate health planning, reflecting “an inherent belief in the ability of people to accurately assess their strengths and needs, and their right to act upon them” (Minkler, 2004, p. 684). In the spirit of locally relevant, community-driven processes, these cases vary greatly in their design, processes, and governance structures because they reflect the unique needs and experiences of the communities from which they originate. While faithful to the tenets, values, and aspirations of the integrative model, these initiatives also vary in their interpretation and implementation of the three pillars. Being guided by local priorities, these projects adopt an incremental approach to resilience that allows communities to swiftly respond to acute needs while continuing to draw from the “toolkit” of strategies and solutions encompassed by the integrative resilience model as needs (and multi-stakeholder collaborations) evolve over time. This is a toolkit which they themselves contribute to and enrich as more integrative solutions are co-designed and deployed by frontline communities and social movements around the world. Therefore, rather than offering a systematic assessment of these projects, the next section is intended to serve as a prompt to stimulate the collective imagination of academics, decision-makers, and other stakeholders interested in engaging with integrative resilience from a practical, not just purely theoretical, perspective. Indeed, while different in scope, these projects all share key characteristics that make them especially well-suited to an exploration of more equitable and transformative alternatives to current models of resilience planning. Together, they address structural inequality while simultaneously providing a space for biopsychosocial support on the ground, helping to keep institutions accountable while articulating stronger demands for meaningful long-term recovery and community empowerment.

Integrative resilience in action: Stories from the global frontlines

A total of six initiatives are introduced in this section. They are organized across three major categories: participatory resilience-building; community-led disaster response and preparedness; and climate health planning. The three are non-exhaustive and do not by any means capture the wide diversity and creativity that characterize emerging approaches to transformative resilience in communities around the world. Nevertheless, they have been selected for their direct relevance to the scope of this paper, which aims to discuss the contributions that the integrative model stands to make to responses to systemic crises such as the coronavirus pandemic and climate change. They have similarly been selected to represent an inclusive range of perspectives and experiences, particularly those that are typically excluded from, and dismissed by, formal resilience plans. Unless otherwise noted, all information about them has been sourced and cited directly from their websites and/or official reports, in a desire to let those involved in their development describe their aims and approach in their own words.

Participatory resilience-building

Northern Manhattan Climate Action (NMCA) Plan

New York City (USA)

https://www.weact.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Final_NMCA_Print_UpdateNov2016.pdf

Spearheaded by We Act, an environmental justice nonprofit organization, the NMCA Plan draws from residents' experience of Hurricane Sandy to weave an integrative lens into the resilience-building process in New York City. A key premise of the plan is that “the very government definition of resilience is shortsighted, and must be expanded to include reshaping political power and erasing economic inequality.” Recognizing that communities in Northern Manhattan are disproportionately exposed to and impacted by climate hazards, the NMCA Plan was co-created by residents through a participatory process that engaged hundreds of participants in seven public workshops, that were complemented by dozens of meetings with project partners and city agencies over a period spanning from January to July of 2015. Their needs and feedback directly helped shape the core ideas presented in the plan, which is structured around four key pillars: energy democracy; emergency preparedness; social hubs; and public participation. Stated in the plan is the belief that the “billions of dollars” governments and private institutions are investing in climate preparedness “should also be leveraged to address other social crises, such as chronic unemployment, poor diet, mass incarceration, and quality of education, among others.” Otherwise, they warn, “the slower erosion of poverty will have the same long-term impact” on New Yorkers as climate change will. For this reason, the Plan outlines policy recommendations and informal local actions that are designed to simultaneously mitigate the impacts of environmental hazards while also addressing “the systemic inequality that has led to a disparity in political power for poor and working-class communities confronting the advancing effects of climate change” today. Solutions include the institution of community land trusts, investments in affordable cooperative housing, the facilitation of active transportation planning, the establishment of cooperatively owned microgrids, the promotion of community banking, and much more. The plan equally identifies existing municipal campaigns that are relevant and complementary to its goals, and works with local champions and municipal allies to push for more ambitious outcomes and ensure that their delivery is executed along equitable and participatory lines. Following its release in July 2015, We Act continues to work with community members and other allies to implement the plan's recommendations, which are currently being developed in partnership with local stakeholders.

Health In Harmony

Indonesia, Madagascar, and Brazil

https://healthinharmony.org/wp-content/uploads/2021-HIH-Impact-Report_Final_small.pdf

Health In Harmony is an organization that works alongside 135.000 Indigenous, traditional, and rainforest peoples to protect over 8.8 million hectares of high-conservation value rainforest in Indonesia, Madagascar, and Brazil. As a nonprofit dedicated to reversing the harms of colonialism, Health In Harmony believes that the climate crisis, the extinction crisis, and the justice crisis must be addressed together. Through its Radical Listening methodology, the organization facilitates locally-designed, community-led interventions that are premised on a deceptively simple mandate: “asking communities what they need to protect their environment, [then] investing precisely in their solutions.” Recognizing that “Indigenous communities are experts on planetary health,” Health In Harmony acknowledges that communities “know the most feasible solutions for living in balance with their ecosystem,” and that allowing them to lead not only validates and respects their knowledge and capabilities, but “helps engender a sense of trust and commitment between communities and global citizens who can help funnel resources to their solutions.” As they write, working in partnership is important because “Indigenous peoples make up just 5% of the population, yet they manage 25% of the Earth's land and support 80% of the Earth's biodiversity.” As an approach, their Radical Listening methodology is groundbreaking not only because it shifts the flow of resources—material, relational, and discursive—from outsider institutions to frontline communities, but because its emphasis on interdependence makes it widely applicable to many other contexts and needs. When the Covid-19 pandemic broke out, for example, Health In Harmony swiftly combined emergency medical response with a “rainforest stimulus package” to address threats to health, livelihoods and the environment. To date, the organization has conducted over 20.300 patient visits and has administered almost 4.000 Covid-19 vaccines in hard-to-reach areas while continuing to call on governments worldwide “to think about comprehensive pandemic prevention that would work at the source to stop future pandemics from happening, rather than focusing investments on simply responding to Covid-19.” For this reason, Health In Harmony also partners with local and international universities to research whether “a Planetary Health/One Health approach of community-designed health, livelihoods, and conservation interventions reduces the risk of viral spillover from animals to humans.” As they write, “Covid-19 is the first of many global shocks resulting from the climate and nature crises. The results could influence conservation and development funders to eliminate silos and design more holistic approaches.” To date, research into the long-term impacts of its innovative methodology has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and a new study is scheduled to be published in late 2022. In addition, the Radical Listening approach has been recognized as a Model to Address Climate Change by the WHO, and has won the 2020 UN Momentum for Climate Change Action Award, among others.

Community-led disaster response and preparedness

Community Disaster Readiness Plan

Red Hook, New York City (USA)

https://rhicenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/RHI-Hurricane-Report-6_2013.pdf

Red Hook is a neighborhood that lies on a peninsula, which makes it especially vulnerable to climatic events. 85% of its residents are Black or Latino, and with a 45% poverty rate, data indicate that Red Hook's residents are “more likely to be exposed to social risk factors, increased barriers to health care, and compounded stressors” (Schmeltz et al., 2013, p. 801). Perhaps unsurprisingly, when Hurricane Sandy made landfall in October 2012, Red Hook was one of the city's four hardest-hit neighborhoods (New York City Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency, 2013). Residents suffered severe disruptions that included lack of heat and electricity for 17 days, and lack of running water for 11 (Schmeltz et al., 2013). Subsequent studies into the impacts of Hurricane Sandy found that the major disaster plans in place at the time did not account for the impacts that “extensive and long-lasting power outages and subsequent lack of key services” (Schmeltz et al., 2013, p. 800) would have on the community. In response, Red Hook's residents developed the Community Disaster Readiness Plan to establish a locally-relevant protocol to address the critical 72 hours before and after a disaster.

The plan is part of Red Hook's Long Term Community Recovery (LTCR) process, a project of the Red Hook Coalition which received assistance from Emergency Management Methodology Partners (EMMP), and financial contributions from the American Red Cross, the Brooklyn Community Foundation/Brooklyn Recovery Fund, and the NYC Housing and Neighborhood Recovery Donor Collaborative. Informed by the experience of community members who were in Red Hook during and after Hurricane Sandy, the plan is especially mindful of the crucial period “before formal government assistance is in place,” and provides recommendations for how to conduct relief operations from the bottom-up. As the initiative's website recounts: “in the first hours and days after Hurricane Sandy, the community of Red Hook organically came together and managed the initial response. Everything from wellness checks, to medical triage, to food distribution, and communications was organized by the community until disaster response and recovery workers were able to get to the isolated neighborhood.” Today, residents consider this document a companion to government policies because, in addition to hurricane emergency response, the Readiness Plan acknowledges the complex reality of systemic risks and “is designed for a wide range of events including snow storms, heat waves, power outages, tornadoes, and earthquakes, among others.” Upwards of 200 people were involved in its development through planning meetings and community input gatherings. At the heart of Red Hook's readiness framework are seven thematic areas that organize and distribute relief efforts across the community. These are: Support Services; Food and Shelter; Communications; Health and Medical; Community Response Team; Utilities; and Coordination. Through each of these areas, the community identifies specific locations where relief activities will be coordinated from at a time of emergency, and outlines roles and resources that will be mobilized by community members until emergency workers are able to reach the neighborhood. An example of such a role is that of Community Response Teams, which are groups of residents who perform basic search and rescue activities to locate individuals who may be trapped in place or requiring special assistance, and who deliver first aid to those in need. Another innovative feature of their plan is Red Hook Wifi, a community-based, solar-powered, free wireless internet network that residents launched during Hurricane Sandy to carry out emergency management operations and restore ongoing communications outside of the neighborhood (Cohen, 2014). Following the completion of the participatory recovery plan, the broader community was invited to learn about its contents and participate in local events that included youth training, workforce development in context emergency preparedness as well as Ready Red Hook Day, a community-wide drill, organized in 2014, that simulated an emergency scenario and acted out the guidelines found in the plan.

International Medical Corps (IMC)

Various Countries

https://internationalmedicalcorps.org/program/mental-health-psychosocial-support/

IMC is a global humanitarian organization that delivers emergency medical services to high-risk populations affected by conflict, disaster, and disease. Established in 1984 by volunteer doctors and nurses, today IMC is a nonprofit with over 7,500 staff around the world, 97% of whom are local. Their approach is rooted in a strong focus on empowerment and self-reliance, which the organization promotes by providing community members with the skills they need to “become effective first responders themselves.” In addition to their emphasis on care and engagement, what distinguishes IMC's approach is the fact that, to date, they are one of the few relief organizations that prioritizes the prevention and treatment of mental health and psychosocial needs—not just in humanitarian crises, but in global healthcare more broadly. As stated on their website, “survivors of conflict and disaster are at higher risk for psychological distress and mental health conditions, due to continued and overwhelming chaos and uncertainty, as well as the enormity of loss that often includes homes, community, loved ones and livelihoods.” Recognizing that mental illness accounts for 4 of the 10 leading cases of disability worldwide and that, during emergencies, the rates of those suffering from common mental disorders can double from 10 to 20%, the organization employs a long-term strategy to help strengthen mental health care systems and shape national policies even after an immediate disaster. For example, IMC advocates for the importance of investing in adequate mental health programs at the donor, government, and policy levels. As their site reports, “only 1% of the global health workforce is working in the field of mental health today,” yet “mental health is critically important to the overall health, economy and social development of whole communities and societies—not just individuals experiencing mental illness.” This is of particular consequence to low- and middle-income countries, where four out of five people are not treated for mental health concerns, and where the impacts of systemic crises are felt more strongly. IMC's model is therefore especially well-aligned with the principles of integrative resilience because of a unique acknowledgment of the importance of mental health and psychosocial support before, during, and after a disturbance. Their work acknowledges the importance of relationship to both resilience-building and healing, and their psychosocial approach is closely aligned with the principles of “bioecological” human development and wellbeing advocated by community psychologists and frontline responders.

Climate health planning

Indigenous Climate Action's Healing Justice Pathway

Canada

https://www.indigenousclimateaction.com/pathways/healing-justice

Indigenous Climate Action is an organization that develops programs and resources that aim to decolonize climate policy and shed light on the ways in which climate issues are intricately connected to Indigenous rights and sovereignty. The organization's action areas are organized along five pathways that range from Gatherings to Trainings and, most recently, a direct focus on Healing Justice. As is the case for many healing justice advocates, this new pathway was informed by personal experiences of burnout and collapse experienced by ICA's leadership, who took stock of the importance of trauma-informed care in avoiding the inadvertent recreation of systems of harm that “reward hyper-productivity” within the context of community organizing. With this pathway, ICA is taking a direct stance against extractivism of all kinds by directly naming, and seeking to transform, the relational dynamics that affect personal and collective wellbeing in the work of advocating for a just future for all. As the organization writes, “in Indigenous communities, the intersection of environmental racism where homelands are destroyed, the trauma of social inequality and violence, and the constant need to assert basic rights in an unwelcoming society leads to a variety of overlapping mental and physical health challenges for many. On top of this, the culture of extraction that defines capitalism is a layer that seeps into every aspect of life—extraction on the land, akin to extraction of time, stories, knowledge, and energy—extraction as a mindset and way of being.” The Healing Justice pathway complements an already rich and dynamic suite of offerings put forward by ICA, and has also been identified as foundational to its internal operations so as to bring about restorative decolonial practices and tools “that strengthen the health of our bodies and whole selves” in every aspect of what the organization does. Some of the offerings in this pathway include the Indigenous Youth Mental Wellness Honorarium, which supports the activism of younger generations by providing accessible and self-governed financial support to uplift their mental health—for example, by accessing funds to help pay for a counseling session, leave the city and “get out on the land,” provide an honorarium to elders for their teaching, afford a training session, pay for a yoga class, and more. Central to ICA's vision is the recognition that “healing is climate justice” and that “rest and relationships are revolutionary.” As they write, “healing is unique to each individual but also is tethered to the collective, to the communities where people work and live.” Here, “communities” include non-human relatives and future generations as well, which is why the organization also actively participates in events–such as the Indigenous Economics conference, organized by the Canadian Society for Ecological Economics, or the global Talks on Trauma series-to raise awareness about the connections between anticolonial and relational thinking with healing justice, planetary health, and resilience.

Indigenous Climate Health Action Plan

British Columbia, Canada

https://www.fnha.ca/what-we-do/environmental-health/climate-health-action-program

British Columbia's First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) is the first and only provincial First Nations health authority in Canada. The organization works with local communities, government partners, and other allies to improve health outcomes for Indigenous people through a collaborative and transparent process. One of its aims is to modify and redesign health services so that they can replace federal programs and better meet the health and wellness needs of their consituents. As part of this work, FNHA launched the Indigenous Climate Health Action Program (ICHAP) to support First Nations leadership in reducing the adverse impacts of climate change on community health. Drawing from the strength of traditional Indigenous knowledge and a relational understanding of health and wellness, the program is explicit about acknowledging that the climate crisis affects health and wellness in direct and indirect ways. The significance of this approach has also been recognized by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which in August of 2019 acknowledged the importance of Indigenous Knowledge in climate change adaptation and mitigation, and stated that Indigenous values play a key role in building climate resilience. The FNHA recognizes that “First Nations' deep cultural connections to the land, water and air make many First Nations in BC more susceptible to climate impacts on health and wellness.” As a result, ICHAP's aim is to strengthen community resilience by “applying a flexible, community-centered approach and wholistic view of health and wellness.” The community-driven projects that ICHAP funds range from a focus on food sovereignty and access to the land to mental health, traditional medicine and harvesting, and more. Even in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, its first funding cycle successfully supported 30 projects across five B.C. health regions from April 2021 to March 2022. Initiatives included the Aboriginal Coalition to End Homelessness; Southern Stl'atl'imx Climate-Resilient Food Sovereignty Project; the Tobacco Plains Land-Based Wellness Project; and Tsleil-Waututh Nation's Climate Change and Community Health Impact Assessment and Resilience Plan2.

Overall, the locally-driven solutions introduced in this section closely resonate with the tenets of the integrative resilience model. They place traditional and experiential knowledge at the heart of framings of vulnerability, and are explicit in centering systems thinking in the ways that solutions are conceived of and invested in. Their strong resource-centered and flexible approach helps to expand and update understandings of health and wellbeing while also shifting power dynamics and narrative framings—promoting empowerment, agency, and collaboration between people and institutions. These initiatives work transversally and incrementally to connect individual and collective wellbeing by providing access to resources, services, and programs that are “multisolving” (Sawin, 2018) and intersectional. As a whole, they provide entry points for continuing to envision, build, and strengthen those the very infrastructures of care that residents recognize as essential to keeping their health (and that of the ecosystems they depend on) resilient and thriving.

Nurturing infrastructures of care: Prompts for future research

This paper aimed to offer an exploratory view of how the integrative resilience model could be leveraged to rethink current approaches to resilience and recovery. While certainly complementary and equally timely, a number of questions and areas for future research emerge that did not immediately fit within the scope of this research project. For example, there is an urgent need to develop indicators that can accurately track progress on integrative resilience, particularly along biopsychosocial lines. Municipalities already collect public health data that might prove useful as a baseline for the development of resilience indicators: how might inter-departmental collaboration be spurred to refine data collection and develop new evaluative tools? Overall, how could these indicators contribute to advancing trauma-informed and healing justice-oriented policies and programs more systematically? Thinking, for example, about the links between traumatic stress and the production of cortisol (Miller et al., 2007; Bevans et al., 2008)—commonly known as “the stress hormone”—as well as insulin dysfunction (Nowotny et al., 2010; Blessing et al., 2017) and increased cardiovascular risk (Edmondson and von Känel, 2017; Remch et al., 2018), how might these biomarkers be employed to track the impacts of environmental distress and the success of resilience interventions for affected populations? How could these be leveraged not to encourage biosurveillance but to legitimize the need for better (mental) health and wellbeing support at a structural level?

Similarly, participatory processes that allow for a bioecological assessment of vulnerabilities on the ground to emerge will also be crucial, so that institutional success isn't measured solely in terms of preventing damage to infrastructure and economic activity but rather on the ability of communities to heal and thrive before, during, and after a disturbance. This process becomes especially significant for marginalized communities who are disproportionately exposed to hazards while simultaneously being at higher risk of isolation and low social support. What methodologies could best support these efforts? What opportunities are there for academic researchers to receive training in emotional first aid and trauma-informed care so as to avoid the risk of (re)traumatization when working with them?

Equally important will be supporting the development of new roles and skills around the nexus of systemic crisis and planetary health, particularly to encourage a preventative model of policymaking that can conceive of community more expansively. As Bednarek (2021, p. 23) asks, “can we include rivers, forests, mountains, salmon and viruses in our idea of community?” Thinking of care beyond the context of acute crises, what could an integrative mandate for Chief Resilience Officers look like? What other roles, departments, and competencies might creatively be conceived of as systemic crises ramp up? At the social level, what policy interventions could facilitate culture change and break the stigma around loss, grief, and mental distress that continues to surround and influence these experiences? How to create response mechanisms that preemptively address the potential for burnout and/or “vicarious trauma” on first responders and community leaders? Similarly, further research directly exploring the climate change-trauma nexus would be especially valuable in exposing instances of environmental racism and climate injustice. It could also support the integration of community-led resilience plans such as the NMCA into official municipal frameworks, and contribute to developing participatory assessments of vulnerability from a bioecological lens. What role could academic research play in facilitating such a change?

In relation to healing justice, what opportunities are there to create spaces for healing and rest—structurally and relationally—as the climate continues to change? How could academic researchers and activists facilitate the creation of a culture of care and solidarity at a time of unrelenting economic pressure, pervasive emotional and relational disconnect, and rampant inequality? Could volatility and uncertainty about the future be used as an opportunity for connection rather than disconnection? What opportunities are there to further theorize healing justice in academic literature and participatory research? And how could healing justice be advanced without erasing or coopting the contributions of LGBTQIA, Indigenous people, and racial minorities who have contributed enormously to its conceptualization and practice?

Lastly, there is also an opportunity to keep refining the integrative resilience framework itself, particularly by conducting a systematic assessment of resilience plans beyond the ones included in this research project so as to identify common areas for intervention in academic, policy, healthcare, and activist domains. Here, a few preliminary questions emerge: How might integrative resilience contribute to our understanding (and development of) therapeutic spaces to mitigate the adverse (mental) health impacts of systemic crises and neoliberal planning? What role could public space play in organizing community responses and facilitating relational healing? And how might a healing justice perspective support community activism around the right to the city and planetary health more broadly?

Conclusion: Stimulating narrative resistance

While the early months of the pandemic seemed to reawaken an appreciation for systems thinking and bring renewed vigor to calls for climate leadership and societal transformation, the lens of crisis has continued to be invoked to reinforce a reactive stance to change, one driven by narratives of enclosure, disconnection, and austerity. Crises, however, can be richly generative moments of rupture that reveal contradictions, incite action, and stimulate new imaginaries for change. They are moments of “moral punctuation” that can be leveraged to fight back against the “anesthetizing effects (Ahman, 2018, p. 144)” of official inattention in two key ways: by “apprehending threats imaginatively (Ahman, 2018, p. 151)” and making them an “arena of creative action open to even the most historically disenfranchised groups (Ahman, 2018, p. 161).” In other words, they are galvanizing events with the potential to turn moments of crisis into moments of care.

Indeed, while neoliberal values have, in large degree, co-opted the resilience planning process in cities, for many community organizers and critical scholars resilience can still be reclaimed and redeemed. The integrative model recognizes that resilience possesses a largely unacknowledged and underestimated potential through which to articulate more robust and meaningful demands for transformative change. In particular, it points to how expanding and diversifying visions of resilience itself could double as a strategy to advance interventions that are explicit in their demands for wellbeing and justice. Experiences such as Ready Red Hook's demonstrate how a strong sense of community, belonging, and engagement can and do empower the emergence of local resilience, giving rise to “a set of networked adaptive capacities” (Norris et al., 2008, p. 135) that contribute directly to the resourcefulness of a community. In other words, it is a way to reframe resilience as more than the practice of protecting buildings and the economy but as the practice of putting relationships back at the heart of systems thinking.