- Centre for Africa-China Studies, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Urbanization has been unprecedented in post-colonial Africa. While cities and towns (urban areas) are crucial to bolstering economic activities, they are equally perceived as the scene for social and economic problems. This in turn exacerbates urban human insecurity. The paper draws on qualitative research method in exploring the challenges and opportunities that undermine or facilitate achieving sustainable and inclusive cities in post-colonial Africa. Particularly, the role of the African Union through Agenda 2063 in materializing sustainable and efficient cities, against the backdrop of climate change, in post-colonial Africa. The study present statistics on urbanization and human security trends in the region such as the rate of urbanization, quality of life in informal settlements and slums, the share of urban population living in slums, and a correlation matrix on the quality of human development in slums. The study finds that while varied strides have been taken across the African continent on a national level, the problem of coordination, structural/systemic violence, prevalence of external vision for Africa's development, and gaps in policy implementation pose a threat to adequately addressing the perils of urbanization on human security in post-colonial Africa. Irrespective, Agenda 2063 offers the continent the opportunity to prioritize urban human insecurity issues as an emerging non-conventional security threat requiring securitization. Also, it offers an opportunity to re-center people at the heart of policy decisions while creating incentives for member states to meet the aspirations, goals, and targets set out in Agenda 2063, as it pertains to sustainable and inclusive cities in post-colonial Africa.

Introduction

Rapid urbanization has been unprecedented in post-colonial Africa. The growth in total urban population was estimated at 28 million in the 1950s, over 125 million in the 1980s, and projected to be 2 billion by 2030 (World Bank, 1986; van Ginkel, 2008). For post-colonial Africa, urbanization connotes modernization and along with it, economic growth and human development through access to better opportunities and social amenities, sound public service delivery, and the fulfillment of the ideals of the American Dream (Churchwell, 2021). The pursuit of industrialization, characteristic of the principle of developmentalizm, would see the emergence of manufacturing [over agriculture] as the means to improving Africa's development and posture in the global political economy (World Bank, 2021). With industrialization would come–at least as promised–new prosperity; increased regional cooperation and integration; sound road, rail, sea, and air infrastructure to foster intra- and inter-regional trade and movement; a shift in skill acquisition; and overall development. Instead, far from economic and human development we see high levels of poverty, poor access to basic social amenities, growing unemployment, and increased susceptibility to pandemics and epidemics. Far from prosperity, we see increased inequality and dichotomy between rich and poor, urban and rural, skilled and unskilled. And far from regional [and international] cooperation and integration, we see conflict and interest-driven rather than people-centered [development] policy interventions, high levels of injustices and human insecurity across the board. Thus, the contributions of urban areas to the overall development of post-colonial Africa remains a hotly contested topic in academia and policy spaces.

Cities and towns in post-colonial Africa are often perceived as the scene of social and economic problems. Mabogunje (2015) argues that their role has been to draw attention to endemic poverty and social degradation which otherwise remain buried and unobtrusive in the rural areas, rather than contribute meaningfully to development. The sporadic increase in informal settlement and slum partially accounts for this problem. As urban population grows, the cost of living or obtaining housing in urban areas increases. Thus, individuals especially those within the low-to-no-skilled categories are forced to live in the periphery of urban areas where they set up informal settlements. These areas rarely have access to basic social amenities like clean water, electricity, and good infrastructure (Bocquier, 2008). The glaring dichotomy between rich and poor incentivizes violence and crime, further undermining human security and hampering attempts at overall growth and development. Considering that urbanization is inevitable, it is imperative that post-colonial Africa becomes proactive in addressing urban human security challenges to achieve sustainable economic and human development.

Cognisant of these challenges, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as the blueprint for a better and sustainable future addresses key global challenges including poverty, climate change, environmental degradation, inequality, peace, security, and justice. Specifically, goal #11 promises to make cities and human settlements more sustainable, resilient, safe, and inclusive (United Nations, 2019). By 2030, the UN envisions that all across the globe will have access to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums; improved and affordable transport with attention to the needs of the vulnerable including persons with disability, women, children and elderly persons; enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries; protect and safeguard the world's cultural heritage; significantly reduce the number of deaths and decrease the direct economic losses relative to global GDP caused by disasters etc.; reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities while paying attention to air quality and waste management; universal access to safe, green and public spaces; improved national and regional development planning; incorporate disaster reduction and management in country-level city and human settlement planning; and support least developed countries in building sustainable and resilient buildings utilizing local materials (United Nations, 2019).

On a continental level, the African Union's Agenda 2063, the New Partnership for Development (NEPAD), Programme Infrastructure Development for Africa, are all instruments aligned to the objectives of the SDGs. Particularly, the first aspiration of Agenda 2063 promises “a prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable development” (African Union, 2021). The seven goals outlined under this aspiration include: a high standard of living, quality of life and wellbeing for all citizens; well educated citizens and skills revolution underpinned by Science, Technology and Innovation; Healthy and well-nourished citizens; transformed economies; modern agriculture for increased productivity and production; blue/ocean economy for accelerated economic growth; and environmentally sustainable and climate resilient economies and communities (African Union, 2021). Of importance to this article is goal #1 and the four priority areas: incomes, jobs and decent work; poverty, inequality and hunger; social security and protection including persons with disabilities; and modern and liveable habitats and basic quality services.

The state has a major role to play in attaining this global and continental agenda. It is tasked with providing the framework to achieve sustainable and inclusive cities in post-colonial Africa while creating an enabling environment for other actors like the private sector and civil society to play their part. Leaving this critical role solely to the private sector would ultimately foster divisions as this actor is profit-oriented while the public sector is tasked with providing public good and the maintenance of law and order. Thus, the level of analysis for this paper is the continental-regional-national dynamics to addressing urban human security challenge.

The aim of this article is to explore the capacity of post-colonial African states in achieving the global and continental goals embodied in the SDG #11 and the Agenda 2063's goal #1 (priority #4). The key question this study seeks to answer is: what challenges and opportunities undermine or facilitate the achievement of sustainable and inclusive cities in post-colonial Africa? We argue that attaining the continental goal presents key challenges and opportunities. The challenges include the lack of coordination across continental-regional-national levels, the beneficiation of systemic violence, external visions for Africa's development, and policy implementation gaps. The opportunities for post-colonial Africa lie in the ability to prioritize the challenges of urban human security as a high (instead of low) politics issue, rethink the region's approach to development–from interest-driven to people-centered, and create incentives to facilitate compliance at a continental level. In this study, we conceptualize urban human security challenges as systemic/structural violence perpetuated by the state and international order.

To this end, the article is structured as follows. The next section discusses and establishes a link between urbanization and human security. Following this, the study draws on the political settlement theory to understand the prevalence of slums and informal settlements in Africa. Also, using descriptive statistics, an overview of urbanization and human security trends are provided. Following this, a discussion on informal settlements and slums as a consequence of structural violence ensues. The article concludes by assessing Africa's capacity to address urban human security issues on a continental scale, while noting the challenges and opportunities.

Urbanization and human security

While there exist many definitions and contestations on what constitutes human security, a prominent feature is that the concept prioritizes the security of individuals, communities and groups over state actors. Thus, human security is a situation where individuals, groups, and communities are privy to a variety of options necessary with the corresponding capacity and freedom to end, mitigate, or adapt to threats to their human, social, economic, and environmental rights (Lonergan, 1999).

The discourse on human security goes beyond its mere definition. As Gasper (2006, p. 228) argues, it “includes normative claims that what matters is the content of individuals' lives, including a reasonable degree of stability.” It prioritizes and securitizes human wellbeing by advocating that the basic requirements necessary for human existence and survival be provided. In addition, Beck (1992) argues that human security is equally about freedoms from threats and risks – and the said risks are increasingly becoming global in scale owing to the phenomenon of globalization.

As Gasper (2006) argues human security as a concept that brings together a myriad of related issues enabling the interrogation of structure, power, politics, and the contextual factors that create and foster insecurities. The concept is central to research or studies related to matters on human development, human rights and social welfare/wellbeing, teasing out the challenges that undermine the protection and empowerment of humans (Gasper, 2006). The discourse on human security has developed since the early 1990s when the first Human Development Report was published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) with the aim of placing individuals at the heart of the development process.

Furthermore, the concept seeks to promote and re-center the importance of a well-being economy over capitalistic (private) and state-based approach. The promotion of human security is also closely linked to a “positive vision” of society that is embodied in notions such as well-being, quality of life, and human flourishing (Lister, 2004). This positive vision has been elaborated through the capabilities approach, which emphasizes the freedom of people to choose among different ways of living, and to pursue opportunities to achieve outcomes that they value (Sen, 1999, p. 2). The state is still liable in the provision of the necessary environment to foster/enable human security, nonetheless. In viewing development as freedom, Amartya Sen draws attention to the notion of opportunities, and in particular focuses on the role of human beings as instruments of social change. Freedoms emphasize “both the processes that allow freedom of actions and decisions, and the actual opportunities that people have, given their personal and social circumstances” (Sen, 1999, p. 17). Thus, human security implies the protection from threats, and empowerment to respond to those threats in a positive manner. The absence of human security can be perceived as violence towards personhood or an individual.

Urbanization, characterized by the increase in the number of people who dwell in cities and major towns, has had varied effects and impacts across Africa. Rapid urbanization has created economic opportunities and increase the productive capacity of [mega]cities. They generate a higher-than-average proportion of the nation's output of goods and services, epicenters for innovation, while offering (economic) opportunities to individuals and businesses alike (Makinde, 2012). For instance, Lagos is considered the biggest metropolitan area in Africa and generates 10 per cent of Nigeria's total GDP (Zandt, 2022). Despite these benefits, the side effect of rapid urbanization includes the creation of informal settlements and slums. With urbanization, at least in the developing world, comes has a hike in the cost of living. This often cause people to move or settle in areas within their budgets, facilitating urban sprawl and agglomeration in the form of informal settlements and slums. Studies show that in sub-Saharan Africa, 72 per cent of urban population is slum dwellers. This rapid increase in the number of slum dwellers in Africa is termed as “mega slums”–characterized by continuous belts of squatter and informal settlements at the periphery of big or mega cities (Bollens, 2008). Irrespective of the characteristic and nature of slums, [human] security is a precondition for development. Thus, the needs of these communities need to be prioritized.

In his seminal text titled Violence, Peace and Peace Research (1969), Johan Galtung defines violence as “present when human beings are being influenced to the extent that their actual somatic and mental realizations are below their potential realizations” (Galtung, 1969, p. 168). Structural violence constitutes the loss of life or reduced potential realizations owing to unequal distribution of resources and wealth, often inherent in social order. This broad definition includes forms of social injustice as structural violence. Structures that promote or maintain certain conditions that gravely affect the security of human beings—physical, economic, psychological, social—can be categorized therein. Urban human security addresses a wide range of concerns and issues affecting urban dwellers. These include basic challenges such as access to food, shelter and health amenities, to impact of climate change and natural disasters such as flooding, earthquakes and cyclones, and collective security issues such as protection from urban terrorism or war (UN-Habitat, 2007). Thus, the failure of key factors such as governments and the relevant institutions to priorities and attend to the needs of urban dwellers in informal settlements and slums constitutes structural violence. For instance, the absence of public goods like electricity, poor or no sewage infrastructure, water and sanitation cause slum dwellers and inhabitants of informal settlements to turn to (environmentally degrading) alternatives.

Given the failure to provide public goods to such communities, members often tend to individually or collectively “pool” resources together to meet their respective needs. This includes digging a borehole or a well to provide water to the community and/or sell to others to generate income. While this has and continues to serve such communities, it has also been a source of health-related issues, communicable diseases and untimely deaths. Most of these communities are hubs for health hazards—pollution, congestion, sanitation, poor waste management systems (Akanle and Adejare, 2017). The unsanitary nature of most slums and informal settlement characterized by stagnant water puddles, burst sewers flowing through the streets or road networks, dumping site for rubbish and plastics often find their way into the drinking water source in these communities while creating a breeding ground for diseases such as malaria (in tropical areas), typhoid, diarrhea, and dysentery, among others.

Also, energy poverty exacerbates the problem. Individuals in peri-urban areas and informal settlements tend to turn to kerosene lanterns and candles for lighting, firewood for cooking, and illegal “tapping” of electricity with sub-par wires and poles—all of which present a penchant for fire disasters. Poor road networks have caused children brace high-rise floods to go to school; children sent to draw water from a communal well have often lost their lives in the process. Poor access to hospitals or healthcare against the backdrop of unemployment has created an enabling environment for quack Doctors to thrive—selling fake and/or expired drugs to members of these communities—and acclaimed herbalists. These occurrences have grave implications on the physical and psychological wellbeing of slum dwellers; they threaten their human security (Krishna, 2010) notes that for the poor, illness can be devastating as it not only affects their ability to earn income, but the added expenses of healthcare can further plunge them below the poverty line.

These harsh living conditions has arguably contributed to the increase in crime and violence within cities. These conditions have created a breeding ground for thugs, gangsters, area boys who commit petty crimes and violent offences to survive. An article by The New Humanitarian cited a study by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime in Nigeria where the emergence of area boys or “agberos” in Yoruba language (one of Nigeria's three main languages) was imputed to the complex dynamics of socio-economic deprivation that confronts young people in cities (The New Humanitarian, 2005). In South Africa, gangsterism is a major source of violent crime in the post-apartheid era. Kynoch (1999) argued that the townships, squatter camps, hostels and mining compounds which have comprised the urban living space for black South Africans have always been plagued with high levels of violence, much of it gang related (Kynoch, 1999, p. 55). The literature on the emergence of gangs provide insight into the role of poverty as crucial causal factors. This argument postulates that the impoverished environments of the locations, slums, informal settlements or squatter camps caused individuals collude to secure territory and control over income-generating activities which often lead to confrontations with other groups pursuing a similar agenda.

Thus, the patterns and outcomes in slums as discussed above are resultant from the government's failure to provide public goods to “illegal” settlements. While such response may be in alignment with the laws and regulations of the land, the reality remains that slums and informal settlements are a direct consequence of rapid urbanization and systemic/structural issues that must be adequately addressed and prioritized in national, regional, and continental development agenda. Prior, it is important to establish an understanding of the prevalence and persistence of slums and informal settlements in post-colonial Africa despite various exploratory development agenda and initiatives to address poverty, socio-economic inequalities in the continent.

Contextualizing the rise of informal settlements in post-colonial Africa

State building efforts in post-colonial Africa have been characterized by neo-liberal dogma in the quest to build or construct state institutions for a functioning state. The quest for political freedom quickly spiraled into the need to participate, thrive, and survive in a global economic system designed to keep Africa as the source of cheap labor and resources, yet a “dumping site” for manufactured goods produced outside the continent. The systemic inequalities characteristic of the global economic system is underpinned by neoliberalism. Richmond argues that neoliberalism assumes that inequality creates productive competition and no risk of conflict where a viable state and social contract exists (Richmond, 2014). This comes at the expense of welfarism, social cohesion, peace, security, and order within societies and states. Herein lies the need for formal institutions in tandem with informal institutions working to ensure that rules, regulations, law and order are maintained, and consequences adequately managed, while the said productive competition ensues. The breakdown or absence of agency within these institutions gives rise to elite groups gaining traction and power to influence and shape outcomes for their benefit.

Khan (2010) defines political settlements as the social order determined by political compromises between powerful groups in society, which shapes the context for institutional and other types of policies. He perceives political settlements as a combination of power and institutions that are mutually compatible and also sustainable in terms of economic and political viability. This implies that institutions and the distribution of power have to be compatible else, in a case where actors are not benefitting from the said compatibility, they are inclined to change the institution Khan (2010). According to this analogy, a political settlement only occurs when institutions and the distribution of power result in minimal economic and political viability. In relation to developing countries, Khan (2010) posits that they are characterized by clientelist political settlement where patron-client networks exercise significant amount of power through formal and informal institutions. In a clientelist political settlement, powerful groups can influence outcomes irrespective of the existence of formal institutions such as regulatory frameworks.

Goodfellow (2017) draws on this approach in examining urban transformation across major cities in Africa. In showing the explanatory strength of the political settlement theory, Goodfellow (2017) adopts Khan's arguments in understanding national political settlements in Africa. He argues that in relation to cities and urban transformation, the relevant formal institutions constitute the legal and regulatory frameworks and instruments within states. These include national-level legislation on property rights and land tenure, as well as decentralized laws and municipal regulations regarding building control, land use, taxation, urban master plans, zoning rules, tendering procedures, and investment incentives Goodfellow (2017). Informal institutions are defined in terms of traditional forms of land delivery that are not endorsed by the state that are clientelist and neo-patrimonial in nature. In terms of distribution of holding power, Goodfellow the theory fosters understanding on some of the outcomes of the distribution of power as well as the formal-informal institutional configuration through which power is achieved Goodfellow (2017). Still on distribution of holding power, Goodfellow assesses mega cities in Kampala, Kigali, and Addis Ababa, and how powerful groups and interests shaped development outcomes across the board. In his analysis, an emerging theme remains issues of land ownership and its relationship with power. His study critically examines the dynamics of urbanization through the political settlement lens, making surmountable contributions to the field.

Informal settlements and slums in Africa are characterized by spatially concentrated poverty and human rights abuses (Klopp and Paller, 2019). As would be discussed in the latter part of the article, slums are characterized by clientelism and repression, but they could also be reflective of cooperation, political mobilization, and collective problem-solving. In Africa, slums and informal settlements must be understood within a wider political context as products of larger historical processes that generate severe inequalities in standards of living, rights, and service provision.

In the early 1950s and the immediate post-independence era, slums were beginning to mushroom owing to mass and continuous migration from rural to urban areas in post-colonial Africa. At that time, slums did not pose existential threat to development prospects thus, authorities ignored the steady rise of slums on the basis that they would erode as economic growth and development occurred (Arimah, 2011). As a result, they were not afforded basic amenities like water, electricity, access to transportation etc. However, as slums and informal settlements became increasingly perceived as a threat to economic growth and development, African governments adopted various strategies to remedy the problem. These strategies include forced removal, slum upgrading programs, low-cost housing and resettlement (Arimah, 2011).

In the post-colonial era, informal settlements and slums are both politically and economically viable to powerful groups. As will be discussed in-depth, they are a source of cheap labor for the rich living in neighboring urban areas. Domestic workers, gardeners, handy-man services are provided by slum dwellers to rich-middle class counterparts in the core urban centers. Also, these settlements are a source of political votes for powerful political elites. Many a times, political candidates campaign in these areas baiting dwellers with resources that address their immediate basic needs—food parcels, money, and supplies—with a promise to upgrade their communities should the candidate be voted into office. Beyond this, the plight of slum dwellers has also been used as a bargaining chip to address existing political and socio-economic issues, for instance, in South Africa, the government through the constitution provides RDP houses to those considered as previously disadvantaged. While there is an availability of land, there is equally disproportionate ownership of land along racial lines. A land audit conducted by the government of South Africa in 2017 depicts land ownership by racial group. 72% of land is owned by whites, 15% by coloureds, 5% by Indians, and only 4% by the majority black Africans (South African Government, 2018). This has contributed to the debates and talks around “Land Expropriation Without Compensation” in an attempt to undo the ills of the repressive and exploitative apartheid regime (Mayinje, 2022).

The political settlement theory problematizes the role of powerful elitist groups in shaping development outcomes across the board through institutions (formal and informal) and holding power. For this study, the theory was used, albeit descriptively, as an exploratory tool to understand the prevalence and persistence of slums and informal settlements in post-colonial Africa. The next section builds on this narrative by discussing the trends and patterns of urbanization and human security in post-colonial Africa. This is imperative in teasing out the challenges undermining continental efforts at effectively addressing human security as a collective problem.

Methods

Trends in urbanization and human security: Africa in perspective

An adequate continental response to urban human security crisis requires a holistic and in-depth understanding of the challenges facing the region at the country and local levels. This section provides an overview of some of the trends in urbanization in Africa drawing on examples from across the African continent but preference will be given to two of the fastest growing megacities in the region namely Johannesburg, South Africa and Lagos, Nigeria. Lagos, Nigeria is deemed the largest city in Africa by number of inhabitants, with an estimated population of nine million people (Faria, 2022). Also, Johannesburg, South Africa is considered one of the fastest-growing cities in Africa with a mix of a booming population and an ever-increasing economic growth (Oluwole, 2022).

Rate of urbanization

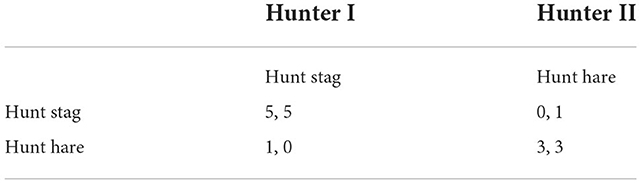

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report titled Africa's Urbanization Dynamics 2020: Africapolis, Mapping a New Urban Geography assesses the trends in urbanization in Africa. It notes that over 50 per cent of the region's population live in one of the urban agglomerations or areas and the urban transition is driven by population growth, rural transformations, and mobility (OECD/Sahel and West Africa Club, 2020). Urbanization in Africa is characterized by mass rural-urban migration and population growth. Studies project that the population of African cities is expected to triple from about 400 million to 1.2 billion by 2050 (Wamsler et al., 2015; United Nations, 2021). Figure 1 is a map showing the share of urban population in Africa, in the year 2020.

Figure 1. Share of people living in urban areas, 2020. Source: Ritchie and Roser (2018).

In the year 2000, most countries in the region fell between 10 to 50 per cent however South Africa (56.9%), Angola (50.1%), Botswana (53.2%), Republic of Congo (58.7%), Algeria (59.9%), Morocco (53.3%), Gabon (78.9%), Tunisia (63.4%), Libya (76.4%) and Djibouti (76.5%) fall above the 50 per cent mark. As of 2020, there has been a sharp increase across the continent in the share of urban population. With regional hegemons in focus, we see an upward trend in the 2020 data: Nigeria has increased from 34.8 per cent in 2000 to 52 per cent, South Africa (67.4%), Kenya (28%), the Democratic Republic of Congo (45.6%), and Libya (80.7%). These patterns support predictions and arguments on the increase urbanization rate in Africa across time and space.

Quality of life (slums and informal settlements)

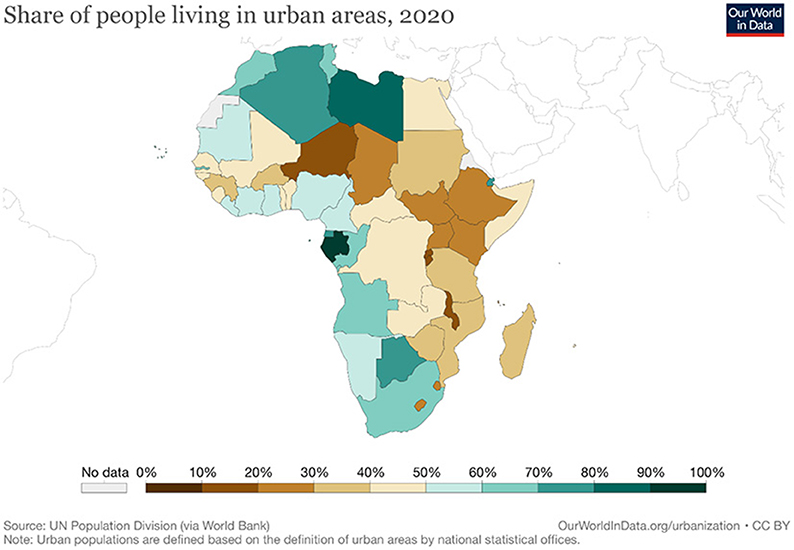

The share of urban population living in slum households and informal settlement reflects the quality of living standards in urban areas across the globe (Ritchie and Roser, 2018). This in turn is a measure of the wellbeing of urban dwellers (and by extension, how secure they are). Thus, the higher the number of slum dwellers, the lower the quality of living becomes thereby threatening human security. The United Nations defines slum households or dwellers as a group of individuals living in an urban area but lack one or more of the following: durable housing, sufficient living area, access to basic social amenities including water and sanitation, and a secure tenure (UN-Habitat, 2006). Informal settlement is perceived as a spatial reflection of dwellings that do not conform to formal planning and legality, standards, and institutional arrangements (Olajide, 2013). Figure 2 shows the share of people living in slums in Africa, 2018 (the latest year with complete data).

Figure 2. Share of urban population living in slums, 2018. Source: Ritchie and Roser (2018).

In Figure 2, only three countries in Africa fall between 0 and 10 per cent—Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia. South Africa and Senegal fall between the 20 and 30 per cent mark and five countries between the 30–40 per cent mark namely Cameroon, Eswatini, Gabon, Ghana, and Zimbabwe. Central African Republic (95.4%), South Sudan (91.4%), Sudan (88.4%) and Chad (86.9%) rank the highest in the region, falling within the 80 to 100 per cent mark. Nigeria (53.9%), the DRC (77.5%), Kenya (46.5), Ethiopia (64.3%) falls within the 40–80 per cent mark.

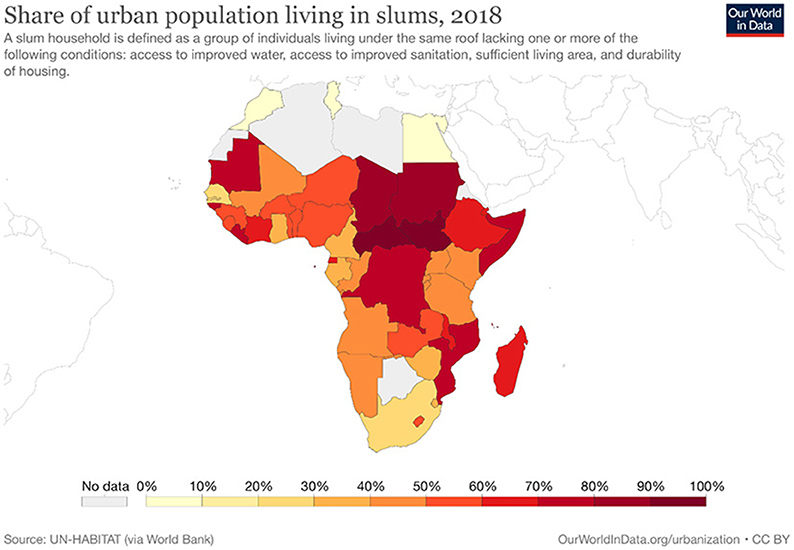

Following this, it was necessary to establish the correlation between the share of population living in slums and human development index, using 2018 data. A correlation graph depicts the level of interdependence or interrelation between variables (Rodgers, 1959). It reflects the strength and direction of the relationship between variables which can be either positive or negative.

Figure 3 shows that there is a negative correlation between HDI and share of population living in slums. A negative correlation implies that an increase in one variable is associated with a decrease in the other. Figure 3 shows that as the share of people living in slums increase, the country's HDI score decreases, although there are outliers in the above. A concentration of countries falls between 3.2 and 4.5 million on the urban population living in slums axis and between 0.4 and 0.6 on the HDI scores. This indeed confirms the importance and centrality of slums and informal settlements in development discourse.

Figure 3. Share of urban slum population and human development. Source: Scatter plot created by the author from The World Bank Data: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS.

Prevalence of non-conventional security threats

There tends to be an overwhelming focus on climate-induced and environmental threats to human security in the literature (Fukuda-Parr and Messineo, 2012; Adger et al., 2014). Other scholars prioritize the prevalence of socio-economic issues such as poverty (defined broadly which expands the usual living below $1 a day to include energy poverty or poor access to basic amenities), human development index, and food, water, and health security (King and Murray, 2001). While we acknowledge the importance of these issues in the human security discourse, we would like to expand these issue-areas to include crime and violence. According to the Urban Safety Reference Group, the interlinked dynamics of urbanization, marginalization, and poor social and physical environments increase the likelihood of crime and violence (South African Cities Network, 2016). This depicts the reality of most post-colonial cities in sub-Saharan Africa yet policy intervention and development agendas are disproportionately focused on erecting modern buildings while forcibly evicting urban poor into the urban periphery areas with little or no access to public service delivery and social amenities required for everyday living.

Mcllwaine and Moser (2003) establish the link between violence, security and poverty in urban Colombia and Guatemala. They find that for the poor, violence and physical safety are perceived to be more threatening than income poverty (Mcllwaine and Moser, 2003). Hove et al. (2013) assess the role of violent internal conflicts in urban population growth. They argue that such conflicts result in the displacement of rural population who end up migrating to [mega]cities in search of greener pastures and relative peace, security, and stability (Hove et al., 2013). Aduloju et al. (2020) argue that crime is a consequence of urban violence. While there exists many forms of such violence against urban dwellers, this study places emphasis on structural violence characterized by inequality, injustice, exclusion, and exploitation (Aduloju et al., 2020). This type of violence is embedded in the functioning of systems set up to cater to the needs of all who dwell within a given jurisdiction.

Studies show that informal settlements and slums are hotspots for crime and violence across Africa. In South Africa, the Cape Flats has been a hotspot for gang violence and crime. Competition for dominance between different gang groups such as the Clever Kids, Hard Livings and Fancy Boys have resulted in vicious shootings often implicating passers-by (Stoltz, 2022). In Kenya, gang-related crime in settlements like Kibera and Mathare are well-documented (Mutahi, 2011). In the struggle for access to limited resources, informal settlements have also become hotspots for xenophobic attacks. In South Africa, ‘Operation Dudula' started in 2021, in Soweto has quickly spread to inner parts of Johannesburg and Ekurhuleni. The operation together with the Put South Africa First Movement aim to root out illegal foreign nationals dwelling in areas like Berea, Daveyton, Hillbrow, Yeoville and the likes (Shange, 2022). Such operations have led to vicious attacks on migrants accused of occupying jobs they deem should be held by South African nationals while blaming the resort to alcohol and drug abuse by South African Youths on the inability to find employment in the country. Adisa (1994) examines the factors that prompt the problem of street violence, drugs and “area boys” in Nigeria. He argues that “the rootlessness of Lagos life, the state of anomie, resulting from migration and social dislocation, rapid economic and social changes, the breakdown of the traditional family structure—which tend to produce a large number of children who go largely uncared for under the harsh economic setting of the megacity—where both parents have to work and children are sent out hawking in the streets in order to survive, are crucial determinants of the increase in street violence in Lagos, Nigeria” (Adisa, 1994).

Results

Africa's capacity to address human security implications of urbanization: Challenges

Rapid urbanization results in a wide range of security challenges that require effective management in terms of the provision of social goods while improving the quality of life for the urban dwellers (Chmutina and Bosher, 2017). Achieving this goal on a continental scale, as reflected in the AU's Agenda 2063, presents key challenges and opportunities. The key challenges include lack of coordination, the continued existence of systemic/structural violence, [external] visions for Africa's development, and policy implementation gaps. Irrespective, Agenda 2063 accords Africa the opportunity to: prioritize the challenges of urbanization as high rather than low politics, rethink the region's approach to development—from interest-driven to people-centered development, and create incentives to facilitate compliance.

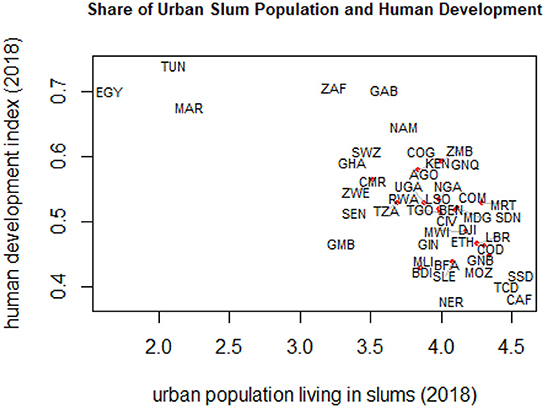

The challenge of coordination between the continental, sub-regional, national, and local levels is adequately captured by game theory, specifically the Stag Hunt or Trust Dilemma or Assurance game (Aggarwal and Dupont, 2008). The game captures the plight of two hunters who have the option to cooperate or choose individual strategies. Cooperation in the game implies “pooling” resources - hunting skills/expertise, machinery/tools, economies of scale/scope—to hunt a stag in which case each hunter will go home with a big portion of meat. Where individual strategy is preferred, both hunters would go home with a hare (smaller portion of meat) or nothing at all (Eyita, 2014). Table 1 illustrates the payoff matrix.

With reference to Table 1, it is evident that the payoffs of cooperation and coordinating strategies to hunt the stag or meet continental goals and targets are beneficial will prove beneficial to all parties involved (5, 5). Mutual defection to default on continental agenda in pursuit of national strategies (or lack thereof) in the lower-right box yields a better payoff (3, 3) than unilateral defection depicted in the lower-left and upper-right boxes (1, 0 and 0, 1), respectively. Thus, the dominant strategy in this coordination game is to credibly commit to cooperation for collective gains.

Similarly, the penchant to achieve the SDGs and aspiration #1 of Agenda 2063 requires member states to align their national policies with that of the continental framework and strengthen implementation of such policies. Thus, collective action towards building resilient cities and liveable habitats in Africa rests on the credibility of commitment by member states towards the goal. Coordination through regional bodies is crucial to addressing urban human security issues. Studies show that city and town dwellers in Southern Africa have grown by 100 million people in the past two decades. As of 2021, 179 million people live in urban spaces representing 47 per cent of the region's total population (le Roux and Napier, 2022), necessitating a need for regional response. In South Africa, the Department of Human Settlement is charged with addressing the urban divide through the provision of quality housing to all South African citizens. Thus, the issue of urban safety is perceived as intricate/inherent to the government's strategy on informal settlements. The South African government has prioritized upgrading informal settlements through its National Housing Policy and the Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme, both of which are part of the Housing Code (Department of Human Settlements and Republic of South Africa, 2009). In compliance with global agenda on housing and sustainable cities, South Africa alongside other sub-Saharan African countries were signatory to the United Nations New Urban Agenda, adopted at the Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development in October 2016. This is indicative of the political will to attain sustainable cities in post-colonial Africa.

Beyond the coordination problem is the existence of structural issues fueling the core-periphery divide in urban areas across sub-Saharan Africa. Specifically, the issue of patronage and clientelism politics of slums and innate the “othering” of people are the focal points of this discussion. The perceived illegality of slums and informal settlements create an enabling environment for opportunism, patronage politics, and clientelism, thereby de-incentivizing the need to pursue the goal of sustainable, resilient cities and liveable habitat. Political clientelism refers to the (promise of) distribution of resources by political office holders or political candidates in exchange for political support, especially in the form of electoral votes (Gay, 1990). Scholars such as (Murillo et al., 2021) argue that insecure tenure, scarce and often discretionary access to public services and resources, and location in areas exposed to environmental shocks increase the vulnerability of slum dwellers which is in turn exploited by politicians and brokers. They tend to politicize access to scarce resources in exchange for political and/or personal favors such as votes. A vast body of literature exists on the link between slum dwellers and political brokerage (Murillo et al., 2021, p. 2).

For instance, money and food politics have been instruments for vote-buying in most parts of Africa. Vote-buying is the direct exchange of benefit and material goods by the political elites to propel electoral support. It includes buying of the voting shares or payments made to voters to influence them to vote for a specific candidate (Essien and Oghuvbu, 2021). Studies show that in Nigeria, people living in rural areas are more likely to experience vote-buying in organized elections (Sasu, 2022). This is highly correlated with the prevalence of poverty in most rural areas. In urban areas, slums and informal settlements have a higher likelihood of vote-buying drawing on the preceding argument on the high rate of poverty. The data shows that across gender, 21 percent of male respondents declared that they were offered money or non-monetary favours in exchange for their votes in the state and national elections in comparison to 18 per cent of female respondents (Sasu, 2022). In Zimbabwe, politicians have overtly promised food parcels in exchange for votes. In the 2013 election, a video footage surfaced on how both Zanu-PF and the MDC used the promise of farming supplies as bait to garner electoral votes (Mail and Guardian, 2013).

On the other hand, some scholars highlight the varying interpretations of vote buying across religious, ethnic, and cultural lines (Auyero, 1999; Mohammed, 2020). In a critical assessment of vote buying and selling in Nigeria, Mohammed (2020) argues that sometimes what is perceived in the literature as vote buying is often demanded by the electorate as incentives to vote and other times, politicians give such incentives of their own free will. He argues, drawing on ethnic, religious, and cultural lines, that in Nigeria when a stranger or a person goes to visit an elderly person, a group of people or a community presenting a gift(s) and its reception thereof is perceived as an act of welcoming the giver. This gesture opens the avenue for the giver to receive the attention of the host and to a large extent, get his wishes granted. Kramon (2013) also argues that cash or food handouts signal a message to the voters on the extent to which the politician is willing and ready to serve and protect their respective interests (Kramon, 2013). Thus, on this premise some politicians present gifts to their electorate with such incentives to vote. While acknowledging the prevalence of such acts in Nigeria and across the African continent, he postulates that the relationship between vote buying and voters' decision remain unclear (Mohammed, 2020). Irrespective, the fact that money and/or food parcels is exchanged with the expectation of voting for a particular candidate or political party to address key development issues in these communities is indeed detrimental to sound governance practices and construes human development as transactional.

Other scholars have alluded to the potential informal settlements hold in promoting democracy in Africa. They argue that slums and informal settlements could become sites and catalysts for increased democratization in Africa through cooperation, accountability, and political mobilization (Anku and Eni-Kalu, 2019; Klopp and Paller, 2019). However, an enabling environment is fundamental for the exploration and exploitation of such potentials.

Furthermore, the existence of slums in post-colonial African cities continues the systemic patterns of “othering” rooted in colonization. On a global stage, African countries (as part of the “Third World”) continue to fight against the core-periphery divide across trade, monetary systems, and issues of global governance. Fairness in international trade to improve terms of trade, volatility in [primary] commodity prices, volatility in exchange rates and participation in key decision-making processes global (such as a seat on the United Nations Security Council) are some examples of the consequences of colonization and an attempt to become an active and important player in global political economy. Yet, on a domestic level, the same core-periphery divide is glaringly perpetuated across different sectors of the economy and works of life—infrastructure, education, access to amenities, access to opportunities, and healthcare.

In Africa, South Africa's transport system can be deemed one of the functional systems in the region. Across the globe, railway transport [arguably] offers an affordable means to move people and goods over short or long distances, effectively. The Gautrain Rapid Rail Project is Africa's first rapid rail network that connects the city of Tshwane/Pretoria, Johannesburg, and the OR Tambo International Airport. Lucas (2011) posits that historically, transportation has been a site for class and race struggles in South Africa. Making reference to the apartheid era, Lucas (2011) notes that passenger transportation was designed to move labor from the townships to urban areas and back. This system resulted in the social exclusion and artificial separation of people. Yet, in post-apartheid era, the government not much has been done to address the mobility needs of low-income travelers who constitute most of the urban population (Lucas, 2011). Currently, the transport system in South Africa reflects continued inequality across income, class, and racial lines. Elites living in “developed” areas of the city commute using cars and the rapid high-speed train–Gautrain, while in poorer areas, people commute by foot, bicycles, minibus, buses, taxis, commuter trains and sometimes, hitchhiking on cars and trucks (Thomas, 2013).

In addition to the coordination problem and systemic violence, competing [external] visions for Africa's development poses an added challenge to the prioritization of urban human security and the consequential alignment in continental-regional-national-local spheres. Particularly, the role of external actors in shaping infrastructure development in Africa cannot be overstated. Post-independence, infrastructure development has been integral to Africa's development strategy. Although, in the immediate period after decolonization under the auspice of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) newly independent governments were exclusively concerned with nation-building, of which infrastructure was integral. The abandonment of infrastructure development was largely owing to the externally imposed development agenda by Western donors, countries and institutions. Under the pretext of the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAPs), governments (mostly from the developing South) were required to pursue certain policies that prioritized and proliferated liberal principles such as free market economy, privatization of strategic national assets and institutions, and shift towards a market-driven (instead of state-driven) system (Abaza, 1996). Consequently, infrastructure investment was undermined in the immediate post-independence era leading to the continued existence in the legacy of colonial spatial planning and exploitation. However, through the formation of the New Partnership for Africa's Development, infrastructure across various sectors of the economy such as energy, transport, communication, and water have been re-prioritized. For Africa, infrastructure is deemed instrumental/fundamental to economic growth and prosperity through the increased movement of commodities and people from one jurisdiction to another. The African Development Bank posits that Africa stands to gain massive economic benefits from improved infrastructure in comparison to other regions of the world (African Development Bank, 2018, p. 66). Irrespective, the type, scope, size, nature and quality of infrastructure developed in most parts of Africa is not solely dependent on the need or requirements of its people but on “international experts”, donors, so-called development partners through the approval of project funds and the conditionalities—technical, feasibility and environmental studies. This enables “development partners” to use the said infrastructure as bargaining chips, as evidence in the proposed Grand Inga Dam, in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Also, these development partners tend to prioritize the economics of infrastructure specifically its ability to yield returns on their investments or enable the borrowing country to repay the loans over the stipulated/agreed time frame. The obsession with infrastructure being necessary for economic development arguably undercuts the social implications of such infrastructures. While infrastructure adds value to the economics of living, it also adds value to the welfare of individuals across the board. Thus, the motivation and decision to develop infrastructure should be premised on the socio-economic impacts as opposed to mainly economic benefits. Also, infrastructure development in Africa has become part of a larger contestation between two world powers—the United States and its allies versus the People's Republic of China. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) underpins China's foreign policy; its “Going Out Strategy”. Embodied in this initiative is China's grand plan to interconnect different countries and regions of the world to China through interconnected railway, road, water, and air transport, as well as information and communication technologies. Yet, Africa's regional infrastructure development agenda is “inward looking” to promote economic growth and increased integration in the region (Lisinge, 2020).

Lokanathan (2020) examined emerging trends in China's BRI in Africa. China's investment in ports and port areas along the coastline from the Gulf of And through the Suez Canal towards the Mediterranean Sea; using its connectivity projects to link its industrial and energy projects in the hinterland of Africa to the infrastructure projects along the African coastline; the argument by China that the project serves local needs is undermined by the use of its State-owned Enterprises (SOEs) in developing infrastructure in Africa; China has been successful in building transnational projects in Africa only where there is either a deficit or vacuum in strong governance across countries; and has had little success working with third-partner countries on specific projects in Africa (Lokanathan, 2020). The United States and its allies have a counter or rather competing “global” development agenda called the Build Back Better World Initiative(B3W). It aims to provide post-pandemic recovery to low- and middle-income developing countries in key areas like climate change, health security, digital technology, gender fairness and equality (Huiyao, 2021). Drawing on these arguments, Africa's agency in such infrastructure development partnerships is non-existent. Scholars like Chipaike and Knowledge (2018) have rebutted the accounts of Africa as a supplicant actor in inter-national relations. They argue that African governments can exert assertive agency in their relations with externalities however, the level or influence of such agency is determined by a number of factors. This includes regime type; possession, ownership, and control of strategic resources; and the willingness of regimes to work with civil society in its engagement with external actors (Chipalke and Knowledge, 2018). Thus, national government intervention through policy and the political will and commitment to ensure that infrastructure development promotes a welfare economy as opposed to exploitation for economic gains is crucial.

Discussion

Building capacity to resolve urban human insecurity: Opportunities

Addressing the crisis of urban human insecurity in Africa to achieve efficient, inclusive, and sustainable cities requires policy and regulatory action, and investments in infrastructure. To achieve these, urbanization and its impact must be considered as high politics issues where the securitization of urbanization has serious consequences on political, economic and social life. Secondly, policies and regulatory action should be people-centered not interest- or business-driven. Finally, there is need for the African Union to create incentives for member states to meet the aspirations, goals, and targets set out in Agenda 2063.

Bollens (2008) argues that enhancing urban safety and security can be achieved through sound urban policies that create physical and psychological spaces that can co-contribute to and actualize human security in cities. He places emphasis on the importance of urban planning interventions as part of a broader and multi-faceted approach that incorporates addressing formal criminal justice and policing, increases community involvement and development of local capacity (Bollens, 2008). A report by the World Bank outlines that planning, connectivity, and finance are three crucial dimensions to attain and maximize the gains from urbanization and sustainable cities (World Bank, 2013). Meeting these dimensions in the quest for sustainable and liveable habitats requires careful planning and coordination across spatial and institutional levels. Planning entails designing policies that would guide the use of urban land, spread population density, and expand basic infrastructure and public services. Connecting entails linking different city markets through good infrastructure to allow the easy movement of goods, services, and people. Financing entails sourcing for huge capital investments for sustainable infrastructure development (World Bank, 2013). In Africa, coordination across national, regional, and continental strategies are crucial.

Infrastructure financing is crucial to urbanization and building sustainable cities. Transport networks, telecommunication, energy, water and sanitation are key components to achieving the continental aspiration of inclusive development. However, national plans and strategies need to be coordinated with regional and continental-level plans and strategies. For instance, the proposed African Integrated High-Speed Railway network proposed by the African Union Development Agency-NEPAD (AUDA) seeks to revive, expand and modernize railway as an affordable form of transport, connecting various cities while establishing Trans-Africa Beltways (African Union, n.d). The impact of this project would encourage intra-Africa trade, boost agricultural and manufacturing sectors, and lower the cost of food (food security) in the medium to long-term. Despite the associated benefits of this project, national governments need to ensure that infrastructure development within their respective jurisdictions take into consideration the continental agenda and goal. Synergy in policies, strategies, design, and project implementation on a national-regional-continental scale cannot be overemphasized.

To build the necessary capacity, urban human security issue needs to be securitized and considered a matter of high politics. The concept of human security itself raises the alarm bell function of security to direct attention and resources to the security of people instead of states (Floyd, 2016). Anderson (2010) argues that security and the act of securing are both dependent on non-existent phenomena of threats and promises. In traditional security discourse, a threat is conceptualized in relation to national or state security. Thus, securitizing a phenomenon as an existential threat that must be addressed swiftly and decisively depends on the prevalent political discourse and its ability to foster transformation. As Guzzini (2011, p. 330) argues, “security is understood not through its substance but through its performance”. Thus, a befitting answer to the question on what makes a problem worth securitizing is the political (and social) construction of the problem. Arguably, a phenomenon becomes a security issue worth securitizing when securitizing actors construct them as such. For instance, the pre-pandemic (COVID-19) world was wrought with discourses on the securitization of migration. The act of terming migration a threat to national security and/or to access to resources by locals evokes a political concern requiring a response such as improved border security, implementing administrative and regulatory rules such as visa requirements, quota systems for temporary or permanent residency permits, and inciting anti-migration sentiments and violence through media platforms among the citizenries.

Similarly, urban human security challenges are construed to pose a threat to national/state security. The glaring core-periphery dichotomy, lack of access to reliable social amenities, increased cost of living, all perpetuate the continued existence of crime, gang violence, and poor quality of life especially in peri-urban areas. As a result, key stakeholders especially within government, have classified these issues as national security threats. In South Africa, the Department of Human Settlement is tasked with the provision of low-cost housing (RDP houses) to previously disadvantaged citizens, in an attempt to address the growth in informal settlements and slums. This is an indication of the government's political will and commitment to achieve the constitutional promise of providing housing to all South African. Despite this, challenges emerge in the implementation of such mandates. For instance, the provision of RDP houses to South Africans is to eradicate informal settlements or “shack-living”. However, the attempt to address this situation remains redundant as RDP homeowners often lease their houses to immigrants in peri-urban areas while remaining in shacks or informal settlements (Scheba and Turok, 2020).

Owing to the affordable cost of rent, immigrants often find themselves in peri-urban areas, with most setting up neighborhood businesses to earn a living. This increase in the number of immigrants has become the political tool for securitizing immigrants. Political heads like Herman Mashaba (Bornman, 2019) and the rise of Operation Dudula (Ho, 2022) have furthered the construction of immigrants as “the problem” and the need for a state response to this growing (and unchecked) threat. The same narrative dominated Donald Trump's four-year regime in the United States. Mexicans were construed as the reason for increased crime, violence, lack of jobs/opportunities for Americans, and the need to “build a wall” to keep out the threat. In both cases, construing immigrants as a security threat by “securitizing actors” (government or political heads) necessitated a state response by both government (on administrative issues) and civil society (mob justice).

Yet, the existential threat of inequality, hike in crime, violence and poor quality of life persists. This indicates that the state's response to urban human security challenges by securitizing migration has not resolved the existing problems. Thus, responses by the state should be geared towards addressing the root causes of the problem—existing structural violence and high youth unemployment rates, among others. Systemic/structural violence is evident in the discriminatory delivery or provision of public good. The Sandton-Alexander case study in Johannesburg, South Africa and the Island-Mainland case in Lagos, Nigeria are some examples of this problem. For instance, in South Africa, residents of Alexander have complained about the poor service delivery in waste management and social amenities like water and sanitation (Ntuli, 2022). Garbage accumulates for weeks on end enabling the infestation of rodents, leaking sewage spilling onto the streets and neighborhood where [pregnant] women, children, and the elderly live. Political candidates have often used the plight of these residents for election campaign purposes, making promises to address the challenges of threatening human welfare, yet fail to deliver upon (re) election.

Similarly, residents of Lagos Island are typically well-to-do middle- and upper-class citizens. As a result, they can, as a community or housing complex, negotiate with the public utility—the Power Holding Company of Nigeria (PHCN) for constant electricity, at an extra cost (mostly to grease the palms of these officials). Yet, mainlanders could go months without electricity and are required to thrive. Most peri-urban areas and informal settlements like Ajegule and Makoko barely have access to electricity, water and sanitation (Egbejule, 2016). The discriminatory nature of service delivery perpetuated by the state through its parastatals fuel urban human security crises. These centers, if properly catered for in national development plans, can be positively impact the growth of urban economies. As le Roux et al. (2022) argue, informal settlements can be a beneficial to urban economies in the provision of affordable labor and low-cost housing services. They encourage city authorities to develop positive, innovative responses to informal and peri-urban areas and recognize them. They draw on cities like Dar es Salaam in Tanzania and the continued efforts in upgrading unplanned settlements by providing infrastructure where communities manage essential systems and services.

Secondly, development policies, strategies and implementation should be people-centered rather than interest-driven. The pillars of capitalism, an economic system characterizing the post-Cold War era prioritizes profiteering even within the confines of development. While profit is widely construed in terms of capital or monetary or fiscal capacity, this paper expands the definition to include non-monetary profits such as soft power, continuity, and agenda-setting. Similar arguments have been used in scrutinizing the politics of development aid in Africa. The absence of poverty, war/conflict would indeed be unprofitable to organizations such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), state actors like the United States, (international) non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and other key players in the “aid and development” business. Similarly, the absence of informal settlements to prey on for votes would have serious implications on politics and elections in Africa. For one, politicians would have to prove their worthiness to be considered for public office. Arguably, the fear of losing such leverage contributes to the growing number of slums in the region.

Finally, it would be useful to create incentives on a continental level beyond rewards for the display of democratic ideals in the conceding of elections. For instance, the criteria for awarding the Mo Ibrahim Prize to African executive leaders tends to emphasize “strengthened democracy and human rights” as a key feature (Mo Ibrahim Foundation, 2022). Yet, the poor living conditions of slum dwellers in African can equally be perceived as undermining fundamental human rights. Also, the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) is a mutually agreed instrument voluntarily undertaken by AU member states as an African self-monitory mechanism. The APRM seeks to promote the AU's ideals and shared values of democratic governance and inclusive development by encouraging all member states of the union to participate in the peer review process and implement the recommendations thereof (APRM, 2017). Perhaps, there is need to expand governance review mechanisms to include indicators drawing on the provisions of Agenda 2063. With reference to the issue considered here, how well a government served its people and improved the human security and development index is a better indication of a government's performance in the quest for (continental and national) development. Expanding governance (review) mechanisms should be based on actual impact and service to the people not just “democracy” index which arguably perpetuates western ideology. The concept of Ubuntu underpinning most of Africa's foreign policy needs to be localized through addressing the human security challenges of urbanization in the region. These recommendations seek to hold key actors like national and local governments accountable and responsible for the implementation of “just” urban transition policies rather than fault “weak” or the absence of institutions as mainstream literature posits.

Conclusion

Post-colonial Africa's urbanization experience has been a double-edged sword. While there have been economic gains from urbanization, there has equally been human security challenges emerging. The economics of urbanization, often associated with hike in living standards, is a major contribution to the movement of low-to-no skilled workers to the periphery of urban areas. Cities and towns meant to be conduit for modernization, economic growth and the promotion of human development become marred with economic and social degradation owing to the glaring divide between “the haves” and the “have nots”. This in turn undermines the safety, security, and welfare of humans thereby requiring state intervention to address urban human insecurity.

To improve the status quo of cities and towns in post-colonial Africa, Agenda 2063 aims to achieve sustainable, resilient, and inclusive cities. However, this vision can only be achieved if regional and national policies of all AU member states are aligned to this goal. For one, national policy decisions have a spillover effect on the region and the continent thus, credibility in commitment to building sustainable, resilient, safe and inclusive cities and towns in post-colonial Africa is crucial. While noting the importance of member state buy-in, other challenges emerge namely coordination problems, structural violence, competing external development agenda for Africa, and the challenges of policy implementation.

Irrespective of these, striving towards the continental goal equally accords African states the opportunity to rethink its approach to development, incentivize development cooperation and compliance, and categorizing urban human security issues as a high politics problem with this goal. Thus, capitalizing on the benefits of rapid urbanization requires meticulous planning and implementation, synergy between human settlement policies at a regional and continental level if Africa is to achieve goal #11 of Agenda 2063.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

This study acknowledges the Centre for Africa-China Studies (CACS), University of Johannesburg for funding my Post-Doctoral Fellowship.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abaza, H. (1996). Integration of sustainability objectives in structural adjustment programmes using strategic environment assessment. Project Appraisal. 11, 217–228.

Adger, W. N. (2014). “Human Security,” in Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects,Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Field, C. B., Barros, V. R., Dokken, D. J., and Mach, K. J. (eds). Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 755–791.

Adisa, J. (1994). “Urban Violence in Lagos,” in Urban Violence in Africa: Pilot Studies (South Africa, Cote d'Ivoire, Nigeria). Ibadan: IFRA-Nigeria. p. 139–175. doi: 10.4000/books.ifra.789

Aduloju, O., Adeniran, I., and Ageh, J. A. (2020). “Urban Violence and Crime: A Review of Literature,” in The Just City: Poverty, Deprivation and Alleviation Strategies. Akure: Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Federal University of Technology. p. 392–406.

African Development Bank. (2018). Annual Report 2018. Available online at: https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/annual-report-2018

African Union. (2021). Goals and Priority Areas of Agenda 2063. Available online at: https://au.int/agenda2063/goals (accessed 2021).

African Union. (n.d.). Towards the African Integrated High Speed Railway Network (AIHSRN) Development. Available online at: https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/32186-doc-towards_the_african_integrated_high_speed_railway_network_aihsrn_development-e.pdf

Aggarwal, V. K., and Dupont, C. (2008). “Collaboration and Co-ordination in the Global Political Economy,” in Global Political Economy. 2nd ed. Ravenhill, J., (ed). New York: Oxford University Press.

Akanle, O., and Adejare, G. S. (2017). Conceptualising megacities and megaslums in Lagos, Nigeria. Africa's Public Ser. Delivery Performance. 5, 1. doi: 10.4102/apsdpr.v5i1.155

Anderson, E. (2010). Social Media Marketing: Game Theory and the Emergence of Collaboration. New York, NY: Springer.

Anku, A., and Eni-Kalu, T. (2019). Africa's Slums Aren't Harbingers of Anarchy - They're Engines of Democracy: The Upside of Rapid Urbanization. Available online at: https://eng.majalla.com/node/79591/africas-slums-arent-harbingers-of-anarchy-theyre-engines-of-democracy.

APRM (2017). About the APRM. Available online at: https://www.aprm-au.org/page-about/

Arimah, B. C. (2011). “Slums as expressions of social exclusion: explaining the prevalence of slums in african countries,” in OECD International Conference on Social Cohesion and Development (Paris: OECD), 1–33.

Auyero, J. (1999). “From the client's point(s) of view”: how poor people perceive and evaluate political clientelism. Theory Society. 28, 297–334. doi: 10.1023/A:1006905214896

Bocquier, P. (2008). Urbanisation in developing countries: is the 'cities without slums' target attainable?. IDPR. 30, 1–7.

Bollens, S. A. (2008). Human security through an urban lens. J. Human Secur. 4, 36–53. doi: 10.3316/JHS0403036

Bornman, J. (2019). Mashaba's Xenophobic Legacy. Available online at: https://mg.co.za/article/2019-11-07-00-mashabas-xenophobic-legacy/

Chipaike, R., and Knowledge, M. H. (2018). The question of african agency in international relations. Cogent Soc. Sci. 4, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2018.1487257

Chmutina, K., and Bosher, L. (2017). “Rapid Urbanisation and Security: Holistic Approach to Enhancing Security of Urban Spaces,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Security, Risk and Intelligence, Dover, R., and Goodman, M. (eds). London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-53675-4_2

Churchwell, S. (2021). A brief history of the American dream. The Catalyst. 21. Available online at: https://bushcenter.org/catalyst/state-of-the-american-dream/churchwell-history-of-the-american-dream.html

Department of Human Settlements and Republic of South Africa. (2009). Incremental Interventions: Upgrading Informal Settlements. s.l.: DHS South Africa.

Egbejule, E. (2016). Lagos's Blackout Nightmare: The Suburb that's been in Darkness for Five Years. Available online at: https://amp.theguardian.com/cities/2016/feb/25/blackout-blues-the-lagos-nigeria-suburbs-that-have-been-in-darkness-for-five-years

Essien, P. N., and Oghuvbu, E. A. (2021). Vote buying and democratic elections in Nigeria. J. Public Admin. Finance Law. 20, 79–129. doi: 10.47743/jopafl-2021-20-05

Eyita, E. K. (2014). Energy Security through Transboundary Cooperation: Case Studies of the Southern African Power Pool (SAPP) and the West African Power Pool (WAPP). Available online at: https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/items/84405ea7-0585-4693-8b58-b7f147aa35ec

Faria, J. (2022). Largest Cities in Africa as of 2021 by Number of Inhabitants (in 1,000s). Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1218259/largest-cities-in-africa/

Floyd, R. (2016). “The promise of theories of just securitization,” in Ethical Security Studies: A New Research Agenda, eds J. Nyman and A. Burke (Routledge).

Fukuda-Parr, S., and Messineo, C. (2012). “Human Security: A Critical Review of the Literature,” Centre for Research on Peace and Development (CRPD) Working Paper. p. 1–19.

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. J. Peace Res., 6, 167–191. doi: 10.1177/002234336900600301

Gasper, D. (2006). Securing humanity: situating 'human security' as concept and discourse. J. Human Dev. 17, 221–245. doi: 10.1080/14649880500120558

Gay, R. (1990). Community organization and clientelist politics in contemporary brazil: a case study from Suburban Rio de Janeiro. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 14, 648–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.1990.tb00161.x

Goodfellow, T. (2017). Urban fortunes and skeleton cityscapes: real estate and late urbanization in kigali and Addis Ababa. Int. J. Urban Region. Res. 41, 786-803. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12550

Guzzini, S. (2011). Securitization as a causal mechanism. Secur. Dialogue. 42, 329–341. doi: 10.1177/0967010611419000

Ho, U. (2022). Nhlanhla Lux Exposed - The Disturbing Picture Behind the Masks of the Man Heading Operation Dudula. Available online at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-04-16-nhlanhla-lux-exposed-the-disturbing-picture-behind-the-masks-of-the-man-heading-operation-dudula/

Hove, M., Ngwerume, E. T., and Muchemwa, C. (2013). The urban crisis in sub-saharan africa: a threat to human security and sustainable development. Stability. 2, 1–14. doi: 10.5334/sta.ap

Huiyao, W. (2021). Build Back Better vs Belt and Road: To Improve Infrastructure Competitition must Yield to Cooperation. Available online at: https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3157865/build-back-better-vs-belt-and-road-improve-infrastructure

Khan, M. (2010). Political Settlements and the Governance of Growth-Enhancing Institutions. Available online at: https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/9968/1/Political_Settlements_internet.pdf

King, G., and Murray, C. J. L. (2001). Rethinking human security. Polit. Sci. Q. 116, 585–610. doi: 10.2307/798222

Klopp, J. M., and Paller, J. W. (2019). Slum politics in Africa. Oxford: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.985

Kramon, E. J. (2013). Vote Buying and Accountability in Democratic Africa. Los Angeles: University of California.

Krishna, A. (2010). One Illness Away: Why People Become Poor and How They Escape Poverty. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199584512.001.0001

Kynoch, G. (1999). From the ninevites to the hard livings gang: township gangsters and urban violence in twentieth-century South Africa. Afr. Stud. 58, 55–85. doi: 10.1080/00020189908707905

le Roux, A., and Napier, M. (2022). Southern Africa's Housing Crisis needs Progressive Policy with less Stringent Urbanisation Regulation. Available online at: https://dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-04-13-southern-africas-housing-crisis-needs-progressive-policy-with-less-stringent-urbanisation-regulation/

Lisinge, R. T. (2020). The belt and road initiative and africa's regional infrastructure development: implications and lessons. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 12, 425–438. doi: 10.1080/19186444.2020.1795527

Lonergan, S. (1999). Global Environmental Change and Human Security (GECHS), Bonn: International Human Dimensions Programme on Global Environmental Change.

Lucas, K. (2011). Making the connections between transport disadvantage and the social exclusion of low income populations in the tshwane region of South Africa. J. Transp. Geogr. 19, 1320–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.02.007

Mail Guardian. (2013). Zimbabwe's Politicians Promise Food - For Votes. Available online at: https://mg.co.za/article/2013-03-19-zimbabwes-politicians-promise-food-for-votes/ (accessed 19 March, 2022).

Makinde, O. O. (2012). Urbanization, housing and environment: megacities of Africa. Int. J. Dev. Sustainabil. 1, 976–663.

Mayinje, Q. (2022). Land Expropriation Without Compensation in South Africa: Why it is Sustainable. p. 1–6. doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.19354616

Mcllwaine, C., and Moser, C. (2003). Poverty, violence and livelihood security in Urban Colombia and Guatemala. Prog. Dev. Stud. 3, 113–130. doi: 10.1191/1464993403ps056ra

Mo Ibrahim Foundation. (2022). Ibrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership. Available online at: https://mo.ibrahim.foundation/prize

Mohammed, A. B. (2020). The menace of vote buying and selling in nigeria and ways forward. ILHR. 29. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3555512