- Department of Urban and Regional Planning, North West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Insecurity, violence, and xenophobia manifest at different geographic scales of the South African landscape threatening to compromise, reverse, derail, and contradict the envisaged democratic processes and gains in the country. Since the dawn of the new democracy in 1994, the South African landscape has witnessed surges of different scales of violence, protests, riots, looting, criminality, and vigilantism in which question marks have been raised with respect to the right to the city or urban space and the right to national resources and opportunities, i.e., access, use, distribution and spread of social, economic, environmental, and political resources and benefits. Louis Trichardt is a small rural agricultural town located in the Makhado municipality of Vhembe District in Limpopo Province, South Africa. In the study, this town is used as a securityscapes lens of analysis to explore urban conflict and violence. The relative importance index (RII) was used to measure the barriers and solutions to advance safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in the study area. In this way, issues influencing the performance of reconfigured securityscapes in Louis Trichardt were explored by highlighting how new town neighborhood securityscape initiatives and activities are contributing to space, place, and culture change management transitions. The discussion pressure and pain points revolve around the widening societal inequalities, deepening poverty, influx of (ll)legal migrants and migrant labor, lingering xenophobia, and failure to embrace the otherness difficulties in the country. Findings highlight the options for urban (in)security, social (in)justice, and (re)design in post-colonies possibilities, limitations, and contradictions of securityscapes in (re)configured spaces of Louis Trichardt. Policy and planning proposals to improve safety and security spatial logic and innovation are explored. The critical role of community and local neighborhood watch groups in complementing state security and private registered security systems is one way of tackling this matter.

1. Introduction and background

In South Africa and with respect to decolonized African architecture and engineering feats in the built environment, ancient, indigenous, and vernacular architecture and designs highlight that historically and traditionally, the South African home has always been heavily securitized enclosures and developments, i.e., in terms of livestock (e.g., kraal and laager), symbolic of identity, territoriality, protection, pride, wealth, and investment among other considerations. This is not surprising as since civilization began, human beings have always been concerned about safety, security, and, by extension, crime. This was either in the form of defining space as a home—be it a cave or an enclosure—or a shelter structure constructed of either wood, grass, mud, or stone. This phenomenon has not completely disappeared but still exists in advanced forms of human livingscapes as reflected in modern and advanced construction and building forms and architectural styles. In a rapidly urbanizing world, there is a growth in concerns about a perceived deterioration in the sense of community due to a heightened fear of crime and violence (Agbola, 1997; Owusu et al., 2015; Frimpong, 2016; Glebbeek and Koonings, 2016). A discernible twist in the urbanization processes and identifiable trends in the Global South is the portrait of segmentation and fragmentation that is mirrored in terms of uneven allocation, distribution, and access to housing, infrastructure, transportation, and opportunities in space, time, and scale. This (sub)structure creates vulnerabilities and cracks that act as urban dividend platforms for safety, security, and crime from both positive and negative perspectives. The interplay of these realities and conditions presents challenging crime, safety, and security matters for post-apartheid South African cities and towns, which have been labeled “divided,” “fragmented,” and “broken” (Todes et al., 2002; Harrison and Huchzermeyer, 2003; Watson, 2009; Nightingale, 2012; Turok, 2013; Van Wyk and Oranje, 2014; Nel, 2016; Chakwizira et al., 2018a,b, 2021; Bank, 2019; Potts, 2020). As a sequel to these underlying spatial structure and organization inefficiencies, different sectors of the city are occupied by different social status groups that exhibit differences and diversity in livelihood styles, including the quality of urban environments (Glebbeek and Koonings, 2016).

In both developed and developing countries, such as South Africa, the safety and security narrative is a priority action area (Jürgens and Gnad, 2002; Landman and Koen, 2003; Snyders and Landman, 2018). One response to this phenomenon has been the emergence and rise of “gated communities” and “enclosed neighborhood” as a mechanism to prevent and control crime, violence, and incivility (Landman, 2000; Landman and Koen, 2003; Lemanski, 2006; Dlodlo et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016, 2019; Breetzke, 2018; Pridmore et al., 2019). These responses are partly explained by inadequate state and safety systems in place meant to protect property and citizens (Atkinson and Flint, 2004; Blandy, 2018; Branic and Kubrin, 2018; Atkinson and Ho, 2020; Ehwi, 2021; Morales et al., 2021). In these neighborhoods and precincts, the urban residents redefine urban spatial structure from territorial inclusion to controlled territories of exclusion, segregation, fragmentation, and gentrification. The steering mechanisms used to achieve the needs and aspirations of the “new enlarged homes and communities” are neighborhood enclosures, neighborhood patrol, vigilantes, private security or corporate guards, installation of closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras, mob action, and “jungle justice” (Karreth, 2019; Kurwa, 2019; Landman, 2020; Makinde, 2020; Quraishi, 2020; Smith and Charles, 2020; Thuku, 2021). Ballard (2005) argued that individuals, groups, and communities can respond through either alone or a combination of assimilation, emigration, semigration, or integration. In criticism, the author has labeled this as the privatization of apartheid and the “diabolical project of creating Europe in Africa” (Ballard, 2005; Furtado, 2022). In Durban, Kalina et al. (2019) highlighted the phenomenon of securitization as a tool for the on-going privatization of public space, which is done at the expense of excluding urban poor citizens. This worldwide phenomenon is not only peculiar to South Africa (Frühling and Cancina, 2005; Lemanski, 2006; Maguire et al., 2017; Rukus et al., 2018; Adugna and Italemahu, 2019; Karreth, 2019; Thuku, 2021). Indeed, urban space is a contested space, and if one adds the right to the city discourse, crime, safety, security, and, at times, violence are used as the instruments in (re)producing and (co)production of spatial enclaves of crime, safety, and security. A subtle but significant characteristic of urban areas is that the demographic density of cosmopolitan people and cultures creates an urban mesh environment in which the (in)visibility and mobility of human and spatial impact of crime, safety, and violence is high, complex, and difficult to extricate (Glebbeek and Koonings, 2016). Crime, safety, (in)security, and violence have been picked in literature as a “system of systems” in urban spatial (re)differentiation and (re)stigmatization in which poverty, exclusion, urban deprivation, and cultural “othering” feature strongly but acknowledgment is provided that these matters represent hard and difficult conversation areas (Leeds et al., 2008; Davis, 2012; Millie, 2012; Milliken, 2016; Salahub et al., 2018). Navigating these urban spatial (re)production, environmental design, and planning matters requires an expanded window of understanding, including exploring the changing and shifting nature of urbanscapes, streetscapes, and neighborhoodscapes if sustainable, comprehensive, and integrated solutions are to be attempted.

While many studies exist from across Africa and South Africa that investigated the social, economic, political, environmental, and physical narrative on safety, security, and crime in urban neighborhoods, no study to date has sought to explore how securityscapes have evolved and (re)shaped neighborhoods in small rural agricultural towns as represented by Louis Trichardt, Limpopo province, South Africa. Generally, the most prevalent crimes are contact crimes (assault), shoplifting, and commercial crime. In residential and industrial neighborhoods, the most reported crimes are burglary and stock theft. These crimes happen within a context in which there are several police stations and satellite stations in Makhado local municipality, namely, Police Stations (Louis Trichardt), South African Police Service (SAPS)—Saamboubrug, SAPS—Makhado, Vleifontein Police Station, SAPS—Dzanani, SAPS—Mara, SAPS—Levubu, SAPS—Watervaal, SAPS—Vuwani, SAPS—Tshitale, SAPS—Tshilwavhusiku, and SAPS—Waterpoort. Although this study acknowledges the contributions thereof of previous studies in terms of the architecture of fear, the creation of “walled cities and neighborhoods,” “enclosures within enclosures,” “perpetuation of gentrification and socio-economic spatial fragmentation,” and “the conceptual understanding and application of the framework of crime prevention through environmental design” (CPTED), the full-cycle application and context issues analysis can never be exhausted in addition to this being limited in the proposed study area (Agbola, 1997; Coetzer, 2003, 2011; Makinde, 2014, 2020; Glebbeek and Koonings, 2016; Landman, 2020). Consequently, studies that seek to further contribute to the changing and shifting urban landscape as motivated by society's response to safety, security, and crime threats and risks in terms of architectural home (re)design, information communication technologies (ICT) and standard engineering and construction safety systems, gated communities, and semi-public spaces are very important (Makinde, 2020). This study, therefore, sought to achieve the following objectives: (1) to understand the knowledge of the crime, safety, and security in Louis Trichardt, a new town as perceived and described by the people who live in the area; (2) to discuss the crime, safety, and security streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes barriers to safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in the study area; and (3) to explore solutions of advancing safe crime, safety, and security streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes in Louis Trichardt town.

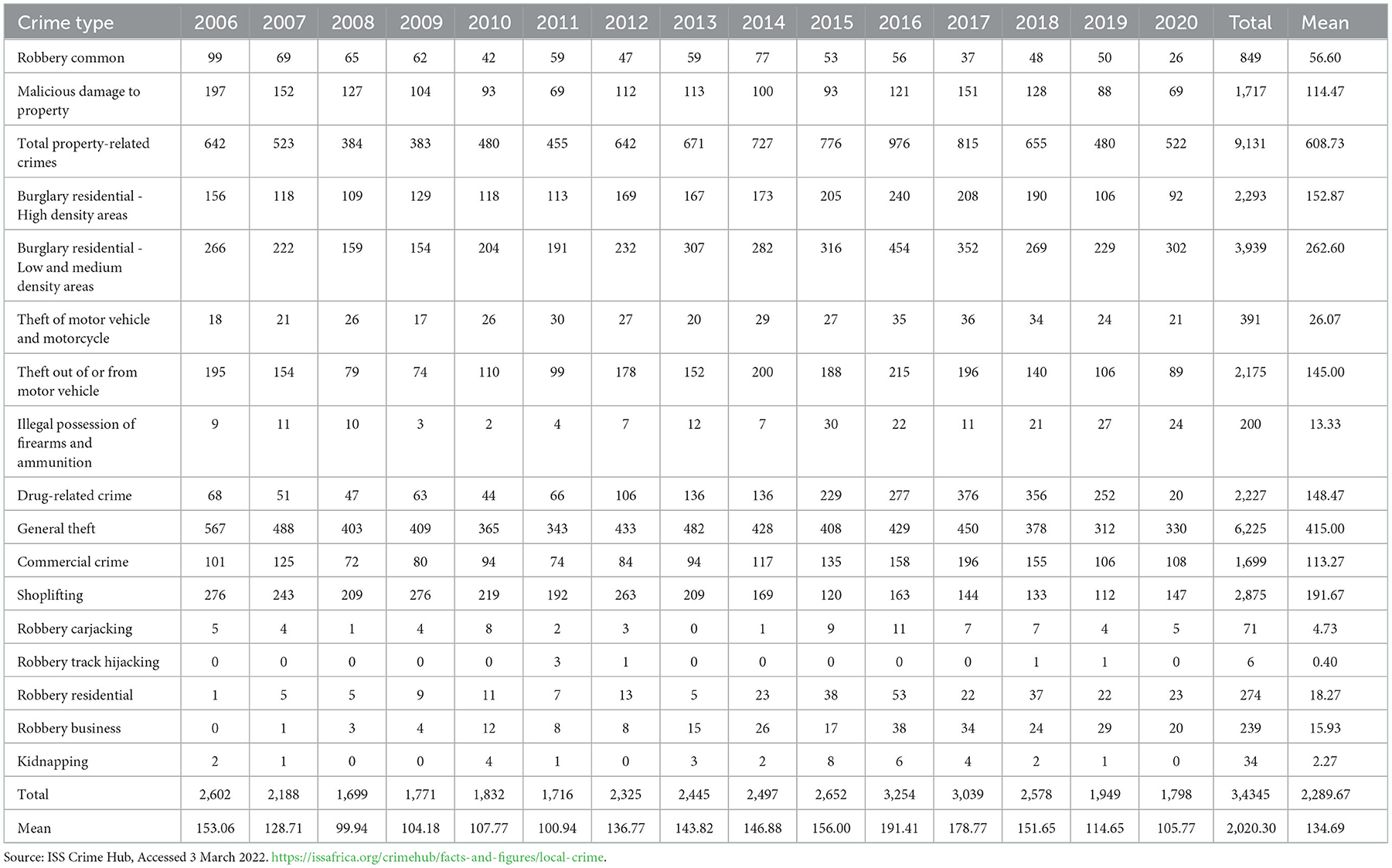

Located 113 km from the Beitbridge border post, the town offers a hedge against border town constraints but at the same time is not immune from the border post geography securityscapes issues of crime and security, cross-border trading (in)formalities, and (in)competitiveness discourses. Table 1 presents a trend analysis of crime statistics in Louis Trichardt (Makhado), during the period 2006–2020.

A spatial increase and spike in crime have been witnessed in Louis Trichardt (refer to Table 1). This is perceived as partly linked to an increase in “illegal” migrants, inadequate employment, entrepreneurship, and job opportunities, as well as the spatial geography, environmental design, and planning inequalities in the town, thus creating tensions and contradictions to safe streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes with implications for spatial land-use securityscapes in the town.

2. Research methods

This qualitative study is based on a case study of a new town residential suburb, Louis Trichardt, Limpopo Province, South Africa. This section covers the description of the case study; qualitative research method, questionnaire structure, and analysis procedure; data sources accessed and analyzed; and data analysis and method procedure.

2.1. Description of case study

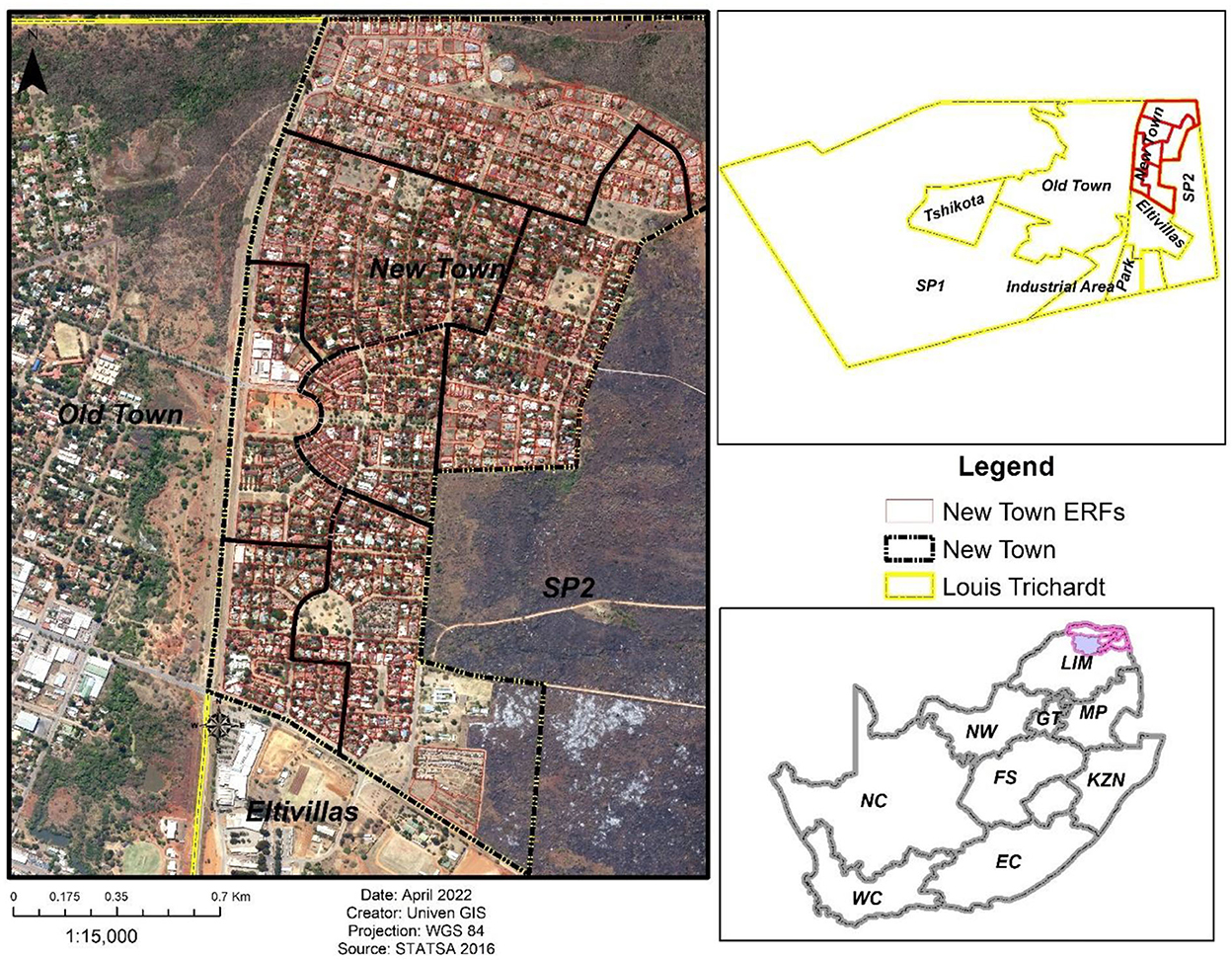

Louis Trichardt town is a small rural agricultural town that is well-known for agricultural products such as litchis, bananas, mangoes, and nuts. The town is located at the foot of the Soutpansberg mountain range, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Louis Trichardt is the center of the Makhado Local Municipality, occupying a land area of ~7,605.06 km2 (or 760,506 hectares) and is populated by ~516,031 residents. The national road (N1) cuts through the town. Louis Trichardt is located 437 km from Johannesburg and 113.3 km from the Zimbabwean border at Beitbridge. The major residential suburbs that surround Louis Trichardt are Vleifontein, Elim, Tshikota, Madombidzha, and Makhado Park. Figure 1 presents the study location map.

This research was conducted in Louis Trichardt, New Town residential areas (Figure 1), Limpopo Province, for a variety of reasons. This small rural agricultural town was selected as it recently experienced a surge in crime and security in unemployment (36.7%), poverty (45.4%), proximity to the Musina border, and a perceived increase in the number of illegal or undocumented migrants from countries located to the north of South Africa's borders. In addition, Louis Trichardt has several active neighborhood watch groups that are integrated with the SAPS. These community policing neighborhood watch groups conduct(ed) jointly and severally night patrols to minimize crime and security concerns in the Town. In terms of interviewing key informants, the snowball sampling method was utilized. This method is very helpful in approaching a population that is not readily available such as typical of the safety, security, and safety value chain and systems (Perez et al., 2013; Alvi, 2016). The participants were asked to rate the extent to which each of the crime, safety, and security neighborhood barriers affected the neighborhoodscapes as well as to make suggestions on possible solutions in advancing safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in Louis Trichardt town using a five-point Likert scale. The reliability of multiple Likert scale questions was measured using Cronbach's alpha. The Cronbach's alpha (α) value obtained using SPSS version 27 was 0.81, indicating a high level of internal consistency for the scale.

2.2. Qualitative research method, questionnaire structure, and analysis procedure

A qualitative research methodology approach was used in seeking to explore the study's research aims and questions. Qualitative research methodology offers the advantages that it is in the research paradigm that argues that human–environmental behavior and interactions cannot be understood and studied outside the context of an individual's daily life and lived experiences (Low, 2003, 2008a,b, 2009, 2017; Salcedo, 2003).

Qualitative interviews were carried out with key informants who were leaders and had lived and experienced the urban environmental conditions of the study area for at least a minimum of 3 years. The purposive selection of the key informants enabled the collection of detailed data and information on the urban crime, safety, and security conditions of the study area (Babbie, 2001, 2020; Wagenaar and Babbie, 2001). In addition, qualitative approaches are viewed as an ethically sensitive way of conducting research (Minichiello et al., 2008). Overall, this method enabled “access to, and an understanding of, activities and events which [could not] be observed directly by the researcher” (Minichiello et al., 2000, p. 70; Quintal, 2006; Minichiello et al., 2008).

In addition to the two five-point Likert scale questions, an open-ended question schedule was developed to examine the issues central to the research questions (Minichiello et al., 2000, p. 65). The questions were related to (1) the safety, security, and crime experiences of living in the residential community; (2) initiatives and possible solutions to addressing safety, security, and crime experiences in the study area; and (3) any ideas or suggestions for improving the environmental conditions in the study area.

These open-ended questions helped to complement, confirm, and triangulate the data and information sources with respect to the two five-point Likert scale central questions. Given the sensitivity and nature of the study, the key informants were approached through contacts making use of the snowball sampling technique. Random approaches on matters linked to safety, security, and crime could have aroused suspicion, thereby causing distress, discomfort, and/or lack of cooperation.

A thematic content analysis of the research findings was conducted, with each transcript being coded according to the identified themes (Low, 2003). Thematic coding made it possible to explore the following issues: (1) respondents lived experiences and perception of safety, security, and crime in the study area; (2) exploring a chronology of measures, strategies, and actions adopted by the residents in response to perceptions of safety, security, and crime in their residential neighborhood; and (3) discussing ideas and potential solutions to fighting the perceived forms of safety, security, and crime in the neighborhood.

2.3. Data sources accessed and analyzed

Four data sets were accessed to explore security statistics in the study area. First, the Makhado Integrated Development Plan (IDP) from 2015–2022 documents were accessed and analyzed. These documents were reviewed with the aim to understand and explore trends with respect to the theme of crime, safety, and security. The interest was to establish whether the theme remained a key theme and a significant priority intervention area. Second, the Crime and Security SAPS databases were reviewed. This database was accessed from 2015 to 2022 with the purpose to understand the trends and major forms of crime, safety, and security matters in South Africa, Limpopo province, and Louis Trichardt in particular. Third, the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) crime statistics databases were reviewed, focusing on extracting crime statistics for the study area. Finally, the Crime and Justice Hub (https://issafrica.org/crimehub) was also accessed and reviewed, with a focus on crime statistics for the study area. Through this triangulation of data, validity and reliability were ensured. It is also suffice to point out that the databases were complementary and had the same information in the final analysis. What differed is how the data and information are presented and analyzed. The content and thematic analysis of these databases enabled for the better interpretation and analysis of study results and analysis in context.

2.4. Data analysis and method procedure

Data obtained were analyzed using frequency, percentage, mean, relative importance index (RII), and ranking. The RII was used to rank barriers to safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in Louis Trichardt town as well as potential steering mechanisms and inflection points to advance safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in Louis Trichardt town, using the new town as the case study. The RII computed in this article is adopted from a previous computation in Mbamali and Okotie (2012), which is as follows:

where

Here x = weights given by each participant on a range of 1–5 on the Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree); f = frequency of respondents' choice of each point on the scale x; and k = maximum point on the Likert scale (in this case, k = 5). The RII computed for barriers to safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in Louis Trichardt town as well as potential steering mechanism and inflection points to advance safe neighborhoods settlements and built environment areas were ranked in their order of size.

Ranking of the items under consideration was based on their RII values. The item with the highest RII value is ranked first, next, and so on. Interpretation of the RII values is made as follows: if RII <0.60, the item is assessed to have a low rating; if 0.60 ≤ RII < 0.80, the item is assessed to have a high rating; and if RII ≥ 0.80, the item is assessed to have a very high rating.

3. Theoretical framework

This section covers three critical but complementary aspects of the theory and philosophy of securityscapes. This section is dedicated to critically exploring the concept and notion of securityscapes and engaging in a theoretical reflection on the multiple dimensions and perspectives on crime, safety, and security in residential neighborhoods. In addition, the concept of home/house, fear, and security is explored within the purview of environmental, urban design, and spatial planning.

3.1. Concept and notion of securityscapes

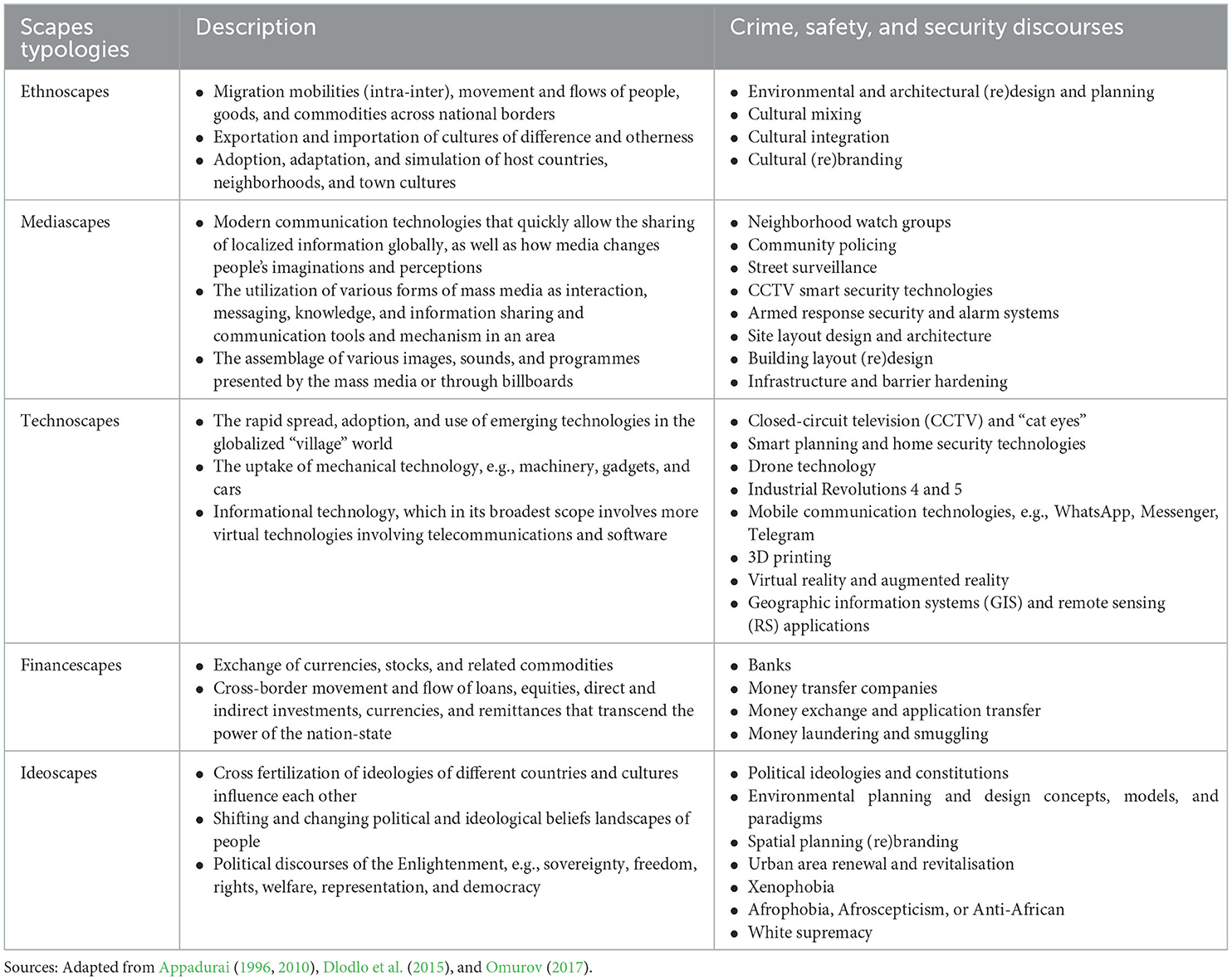

The concept of a securityscape is linked to the understanding of human (in)securities. It was coined and developed from the original concept of “scapes,” originally proposed by Appadurai in 1996 (Appadurai, 1996, 2010; Omurov, 2017). Securityscapes are defined as “imagined individual perceptions of safety motivated by existential contingencies or otherwise theorized as givens of existence (i.e., death, freedom, existential isolation, and meaningfulness)” (Omurov, 2017). Table 2 presents an adapted exploration of Appadurai's (1996) five scapes within the scope of the built environment.

Table 2. Unraveling Appadurai's (1996) five scapes: reduction and application to crime, safety, and security in built environment dimensions.

According to Appadurai (1996), definitions of scapes can be viewed as the conceptual lens with applications to the built environment (refer to Table 1). This can be understood from a perspective that scapes are imaginary transboundary perceptions consisting of “ethnic, cultural, religious, national, political, and other identities” not confined to geographical scales but are subject to globalization drivers such as labor mobility, technology innovation and diffusion, media communication, curation and management, and ideology with regard to individual domestication of the above-mentioned issues (Omurov, 2017). Following Appadurai's concept of “scapes,” von Boemcken has attempted a refinement of the definition of securityscapes (Von Boemcken et al., 2018; Von Boemcken, 2019; Von Boemcken and Bagdasarova, 2020). In these studies, the authors highlighted that people have developed both mitigation and adaptation strategies and everyday life behavior linked to perceived and imagined threats and potential solutions. This is achieved via mind mapping and picturing secure and safe streets, neighborhoods, and environments (both psycho-social and geographical-spatial) for themselves, families, neighborhoods, and communities. From this exercise, one then adjusts attitudes, behavior, movement, and trip pattern (whether conscious or subconscious) to fit and navigate in safe and sustainable living patterns within imagined secure world realms (Omurov, 2017; Boboyorov, 2018; Ismailbekova, 2020; Oestmann and Korschinek, 2020; Paasche and Sidaway, 2021).

In this article, the concept and notion of securityscapes are extended to apply to the concept of streetscapes, blockscapes, and neighborhoodscapes. In this regard, streetscapes, blockscapes, and neighborhoodscapes are conceived and viewed as multiple and differentiated dynamic, changing, and shifting scale dimensioned; safety, security, and crime imagined; and related imaginations and practices that individuals, communities, and organizations adopt in seeking to show and make their environments safe from crime and violence. This incorporates the concept of “riskscapes,” which is defined by Müller-Mahn et al. (2018) as an assemblage of local practices for managing risks quite, irrespective of the “discourses of danger” articulated within the “ideoscape” of the town, neighborhood, or nation-state (Lemanski, 2006; Müller-Mahn et al., 2018).

3.2. Theoretical synthesis on crime, safety, and security in residential neighborhoods

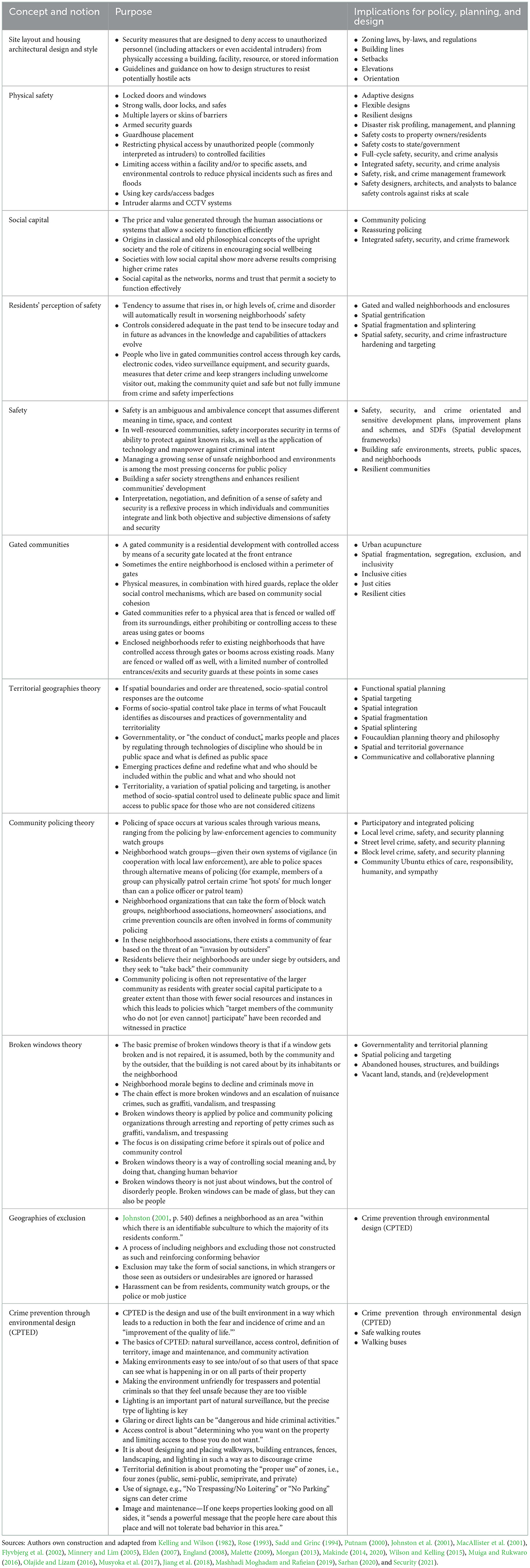

Table 3 presents a schematic tabular representation of safety, security, and crime theoretical groundings.

Table 3. Schematic literature review of representation of safety, security, and crime theoretical groundings.

The intersection of crime, safety, and security highlights the multidimensional, multidisciplinarity nature of the crime, safety, and security adaptive complex “system of systems” (refer to Table 3). At the same time, interventions and initiatives to address the challenge are innumerable, but these measures and efforts can never be perfect or complete. Although safety, security, and crime can be reduced, it is debatable whether all risks can be completely wiped off in an area. Safety and its antithesis of unsafe are, therefore, conceived and viewed as important and intriguing concepts (Wilson and Kelling, 1982, 1989; Lawanson et al., 2013; Farinmade et al., 2018; Iliyasu et al., 2022). Makinde (2020) highlighted that although increased safety precautions may alleviate the resident's fears, upgrades and alterations to the physical environment can introduce visual cues that may intensify concerns about neighborhood crime, safety, and security in other people as well as give high-risk signals to attract criminals to such highly “protected and defended” properties. It is also interesting to note that the need for a more reassuring police presence in the community is highlighted as part of the solution (Millie and Herrington, 2005; Millie, 2010, 2012, 2014; Millie and Wells, 2019). Millie's “reassurance policing” is an approach to encourage positive encounters between the police and the public, thereby fostering greater police presence, visibility, and accessibility (Povey, 2001; Millie, 2012; Oh et al., 2019; Park et al., 2021; Aston et al., 2022).

3.3. Linking security, urban design, and spatial planning

Linking security, urban design, and spatial planning is one critical cornerstone to building sustainable and friendly urban environments. In seeking to explore how security, urban design, and spatial planning are interrelated and interconnected, there is a need to revisit the notions and concepts of security, urban design, and spatial planning. Such reconceptualization seeks to locate the home/house as the first unit of security, urban design, and spatial planning, while the community is an invisible open enclosure of the extended aggregated values and standards of the home/house security, urban design, and spatial planning regimes. In this analysis, three typologies of security, urban design, and spatial planning emerge (1) home/house security, urban design, and spatial planning (i.e., micro site unit location, design, and architectural offerings); (2) neighborhood security, urban design, and spatial planning (i.e., meso block and street landscape, layout and block design, and sense of place characteristics); and (3) the residential suburb community security, urban design, and spatial planning (i.e., the macro township or suburb or suburban security, design concept and spatial structuring form, and structure and arrangement). These three levels of the concept of home, house, street blocks, and neighborhood cascading to the township or city-wide spatial structure represent the hierarchy of security, urban design, and spatial planning complexities that operate as a “system of systems” in either promoting safe urban environments or not.

In exploring the relationship further, a home/house is defined by the Oxford dictionary as “the place where a person (or family) lives; one's dwelling place, e.g., a specific house, apartment, etc.” The concept of the home can be expanded to include the extended home/house (the neighborhood, the suburb, the town, and community, as well as other environments that we identify as home, e.g., spatial area or region or province of origin) and is, therefore, viewed as symbol-laden. A home encompasses the following attributes: resting place, place of peace and security, love and belonging, recovery and social ties and bonding, inspiration, and identity, among other aspects (Appleyard, 1979a,b). The home, therefore, embodies the familiar place in which residents are comfortable and feel at ease. In addition, the home nests a place identity through the medium of a location that one perceives as “theirs, ours” and acts as a symbol of self-identity, consciousness, ownership, possession, and inheritance (Marcus, 1976, 1997, 2006; Low, 2008a,b; Argandoña, 2018; Smith, 2018; Akesson and Basso, 2022). The term “fear (of crime, safety, and security plus)” was coined by Lemanski (2006) in recognition that fear of crime, safety, and security is related to much wider processes than just crime and violence. Various studies corroborate that “fear (of crime, safety, and security plus)” does not match the actual risk of victimization (Valentine, 1989, 2016, 2022; Valetine, 1992; Beck and Willis, 1995; Beck and Chistyakova, 2002; Beck and Robertson, 2003; Eugene et al., 2003; Buus, 2009; Eagle, 2015; Beck, 2019; Hughes, 2022). Oftentimes, the fear of crime, safety, and security plus masks broader and deeper fears (Judd, 1994, 2004; Samuels and Judd, 2002; Judd et al., 2005; Jalili et al., 2021). In South Africa, these deeper and broader fears include the presence of other races/ethnicities/nationalities in proximity, fear of “otherness,” fear of changes (at a national, provincial, and local scale), and fear of uncertain future for oneself and one's family (Schuermans, 2016; Blandy, 2018; Masuku, 2018; Yates and Ceccato, 2020). In this regard, Lemanski (2006) highlighted that the label “fear of crime, safety, and security plus” can be viewed as the explanation for deeper fears of change and racial difference.

Meanwhile, a community is defined as “an interacting population of various kinds of individuals in a common location” or “a group of people with a common characteristic or interest living together within a larger society” (Dunn, 1996; Clough, 1999; Jordan, 2018). Invariably, the concept of the community can have interpretations in terms of an extended and expanded concept and notion of the house/home and neighborhood that creates a sense of belonging, cohesion, bonding, togetherness, and unity of common purpose within the bounds of diversity and differences in a township, suburb, or city-wide environment.

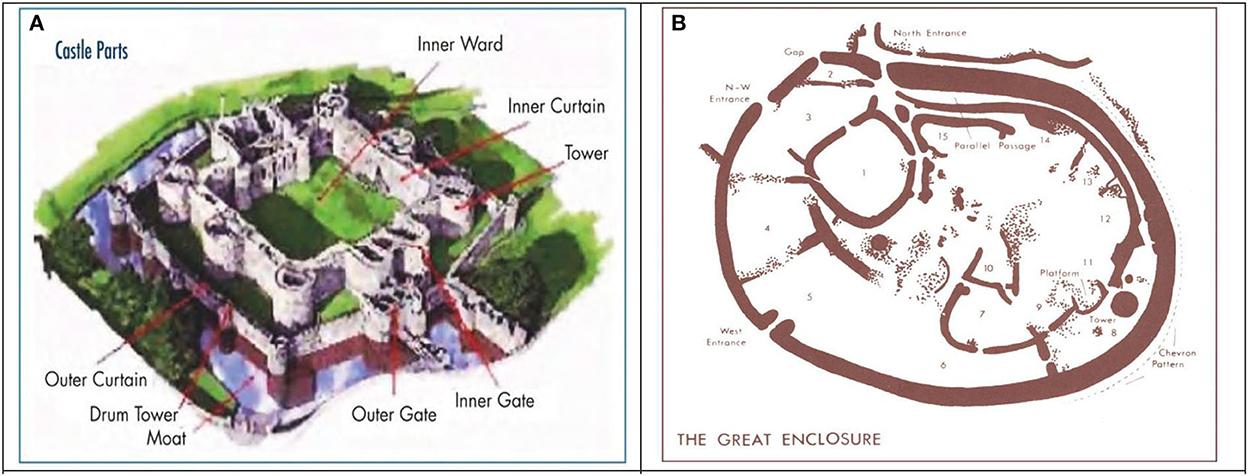

Considering the proceeding debates, the history of urban planning and spatial design has numerous studies that clearly incorporate fear (of crime, safety, and security plus). For example, the classical design of castles and walled cities (found in both pre-colonial and post-colonies of developed and developing countries), in terms of the courtyard design and the Cul-De-Sac and Radburn principle, has long demonstrated the influence of location, site design, urban design, spatial planning, landscape architecture, and public planning in creating safe environments, neighborhoods, and homes (refer to Figure 2). The medieval cities and castles, Bentham's (1830, 1843a,b) classic “panoptican” prison design, Baron Haussman's Parisian boulevardization, and Jacobs's (1961) reliance on natural surveillance (“eyes on the street”) to reduce fears of crime, safety, and security related focused on research studies that illuminate the interaction, integration, and complementarity between private, citizen, and state-driven fear spatial design, planning, and management strategies (Lemanski, 2006; Li et al., 2011; Frimpong, 2016; Philo et al., 2017; Courtney, 2018).

Figure 2. Crime, safety, and security plus site, urban design, and spatial planning examples from the history of town planning. (A) Fema's site and urban design for security historic European settlement spatial structure. (B) Great Zimbabwe site and urban design African settlement spatial structure. Source: Fema (2007) and Chirikure and Pikirayi (2008).

Urban planning and design principles, norms, and standards to counter crime, safety, and fear plus issues consider the following elements summarized in the CPTED (refer to Figure 1): built and neighborhood environments that are easy to see into/out; lighting to make criminals and intruders impossible to hide; designing and placing walkways; building entrances and fences; landscaping; and lighting in such a way so as to discourage crime are important hallmarks in home, site, street, neighborhood, and town/cityscapes design and spatial logic systems (Cozens et al., 2005; England, 2008; Owusu et al., 2015; Iqbal and Ceccato, 2016; Lee et al., 2016; Marzbali et al., 2016; Sohn, 2016; Thani et al., 2016; Mihinjac and Saville, 2019). Thus, connecting, linking, and integrating security, urban design, and spatial planning in a harmonious way are central to creating safe and friendly home/houses precincts, urban streetscapes, blockscapes, neighborhoods, suburbs, and cities that are a pleasure to work, live, and recreate in. These building blocks are linked to each other in an “onion” security, urban design, and spatial planning framework in which each unit of analysis builds and adds a layer and skin of (in)security, urban design, and spatial form that, in aggregate, constitute the “total” security, urban design, and spatial planning safe and friendly environment. This security “system of systems” “onion-layering” security, urban design, and spatial planning system create a value chain that if “broken” or disturbed, has reverberating impacts on the need for system security, urban design, and spatial planning framework adjustment and amendments in attempts to recover and imprint security, urban design, and spatial planning norms and standards of safe and secure environments subscribed in each area. Considering the discussion, the importance of full-cycle analysis and activation of these linkages in application to the crime, urban design, and spatial planning context of any urban or rural setting cannot, therefore, be over-emphasized.

4. Discussion of results and findings

This section discusses study results and findings from the key informants' interviews (KII) as well as an analysis of crime statistics extracted from the relevant databanks. In addition, the study recommendations, study limitations, and areas for future research are also explored.

4.1. Key informants respondents: Descriptive statistics

Forty-four (44) key informants were purposively sampled by the researcher for their knowledge of the crime, safety, and security in Louis Trichardt and the new town residential suburb. Table 4 presents the demographic breakdown and representativeness of the study respondents.

The selected key informants had first-hand information working with the district development planning forum, spatial planning and human settlement and environmental design, IDP Representative Forum, IDP Clusters, IDP Steering Committee, Community Policing Forum, Crime Intelligence, and Investigating Crime (refer to Table 4). They thus provided critical insights, reflexive thinking, and perceptions with respect to the integration and intersection of crime, safety, and security with environmental design, architecture, street planning layout, spatial planning, community policing, statutory constitutional peace, and order as well as general environmental wellbeing of streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes. These insights assisted in deepening and expanding the interpretation of the discourse under investigation. It is suffice to point out that the IDPs in the study area have prioritized basic service delivery provision with an emphasis on water and energy and implied attention to crime, safety, and security. The identified gap partly explains the lack and absence of architectural Liaison Officers in the police departments and local authorities for structured engagement and resolution of crime, safety, and security matters in the study area. Although preventing and combating crime is not easy, it is, however, not an insurmountable task. With greater cooperation between the state and non-state actors, the various types and categories of crime can be tackled head-on. However, attention must not be lost that those solutions to (re)solve these issues are complicated and rely on a level of state resources/competence that seems difficult to materialize if we use prior knowledge and experience on how similar problems have played out in practice. This perhaps calls for the need for both the state and non-state sectors to re-invent and innovate differently in seeking to transform the crime, safety, and security landscapes in blockscapes, streetscapes, and neighborhoodscapes in any setting.

4.2. Crime statistics trends in the study area

Data sets from SAPS statistics and the ISS were accessed and filtered by sub-district and precinct to reflect the data relevant to Makhado Local Municipality. Property crime and property-related crime instances are very high in the study area (refer to Table 1). While this is the case, attention should not be lost on the other crimes as criminals usually commit the crimes in a chain and a multi-pronged comprehensive and all-inclusive approach to tackling crime and safety matters are important. An approach that isolates and targets one crime and safety hotspot and thematic zone area will result in displaced crime and safety spill-over effects. Crime has been on an upward trend from 2006 to 2020 (refer to Table 1). At the same time, due to the COVID-19 lockdown in 2021 together with stronger local neighborhood activity during this period, the crime levels were low. This upward and concerning trend in crime activity was lamented by one of the key activist informants as follows:

“When I moved to stay in Louis Trichardt town in the early 2000s, this was owing to a job opportunity I was very keen to pursue. The little town was sweet, clean, and peaceful. I am afraid I cannot say the same about the town as of now. I remember I could hang clothes until very late in the night and would sometimes forget to pick up the clothes on the line. However, my family and I would wake up and still find the clothes on the line—intact. Now mention this to fellow residents and it is like you are talking folk stories or jokes. We now must be vigilant. We now have an active neighborhood watch group that also has an interest in the development of the town. They are night patrol teams that work hand in hand with the police. These patrol the streets at night for seven days. Different teams do this every day, and they have nicknames and identity codes that I will not share with you. They are doing a very good job and assisting with identifying bushes that should be cleared, overgrown grass that should be cut, and identifying abandoned or vacant stands to establish owners and ensure that these areas are not nests for unscrupulous elements. They have a functional system which we are grateful for. I know they are working on hiring a security company for the neighborhood and have engaged well with the municipality to implement a city-wide CCTV programme to assist in crime detection and prevention.” Extract of a verbatim interview with a key informant respondent local development activist in the study area.

As reflected in Table 1, with regard to the burglary at residential premises in the police precinct, Makhado is a crime area of concern. Burglary has been an increasing trend, creating fear, security, and crime plus challenges for the residents. Usually, the spike tends to be in the early year (i.e., January to March) and midyear around (i.e., August and September) as well as October and November. These are linked to the holiday and festive seasons as well as the beginning of the year in which some key informants attributed anecdotal evidence to returning “illegal immigrants” from the north of South Africa. Although this perception was shared, there were no hard statistics to support and confirm this viewpoint. Regarding the current levels of crime in Makhado Local Municipality, in 2022, residential burglary and general theft are the highest forms of crime common in the study area. This places in perspective on residents' crime, safety, and security fear plus concerns, thus prompting residents to respond in various ways such as changing traveling behavior and patterns and upgrading home security systems, such as buying dogs and cats for added security. Property- and contact-related crimes are high in the study area. This is because property attacks usually involve contact with thieves.

4.3. Barriers to secure streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes

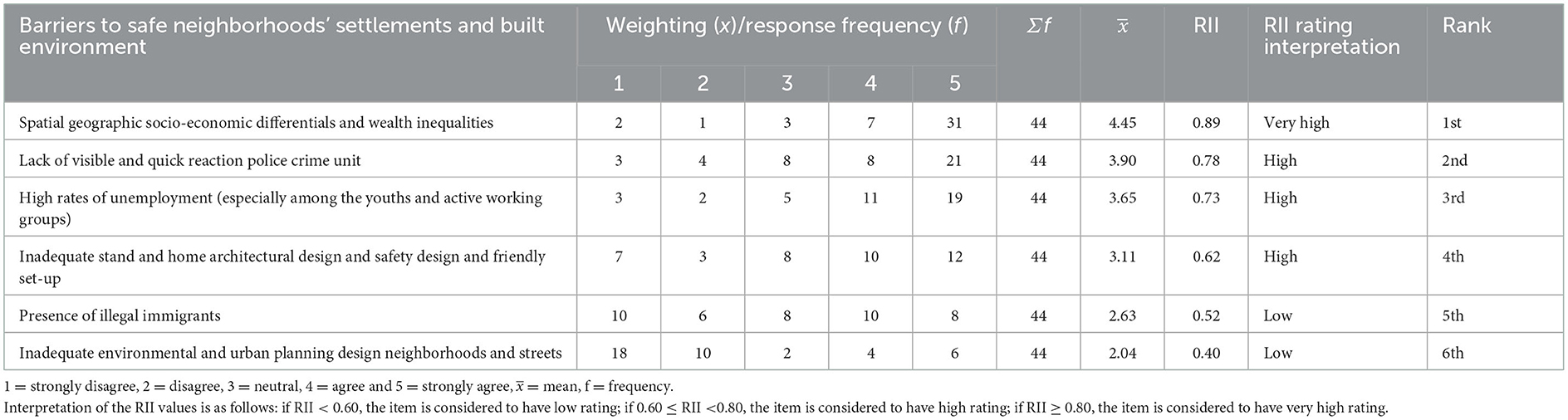

The barriers identified from the literature and confirmed by key informant stakeholders of the new town Louis Trichardt neighborhoods' settlements were ranked according to their RII (refer to Table 5).

Table 5. Barriers to safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in Louis Trichardt town.

The ranking that crime, safety, and security plus matters are indeed social and economic issues corroborates previous findings of similar and related studies that apply the “broken windows” theory to the phenomenon (refer to Table 5) (Frimpong, 2016; Wrigley-Asante, 2016; Beck, 2019; Oh et al., 2019). The major crime, safety, and security streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes barriers to safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas are as follows: spatial geographical socio-economic differentials and wealth inequalities (RII = 0.89), lack of visible and quick reaction of police crime unit (RII = 0.78), high rates of unemployment (especially among the youths and active working groups) (RII = 0.73), and inadequate stand and home architectural design and safety design and friendly set-up (RII = 0.62). However, the presence of illegal immigrants (RII = 0.52) and inadequate environmental and urban planning design neighborhoods and streets (RII = 0.40) are low ranking factors that explain the architecture and dimensions of crime, safety, and security streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes in the study area. The need to address the spatial and economic geography inequalities, inefficiencies, and settlement distortions have long been identified as a stubborn legacy that requires resolution in South Africa (Nightingale, 2012; Turok, 2013; Chakwizira et al., 2018a). The 2030 National Development Plan (NDP) in South Africa highlights the importance of creating a reassuring and world-class police and security system in South Africa. Chapter 12 on building safer communities objective is: “In 2030 people living in South Africa feel safe and have no fear of crime. They feel safe at home, at school, and work, and they enjoy an active community life free of fear. Women can walk freely in the street and the children can play safely outside. The police service is a well-resourced professional institution staffed by highly skilled officers who value their work, serve the community, safeguard lives and property without discrimination, protect the peaceful against violence, and respect the rights of all to equality and justice.” The requirement for better policing presence, availability, accessibility, and velocity in addressing crime, safety, and security is a requirement and expectation that transcends nation-states throughout the world (Millie and Herrington, 2005; Millie, 2010, 2014; Ratcliffe et al., 2015). The matter of the inadequate site, home and neighborhood environmental, spatial planning, and design deficiencies is a matter at the core of urban design and planning (Cozens et al., 2005; Owusu et al., 2015; Iqbal and Ceccato, 2016; Lee et al., 2016; Marzbali et al., 2016; Sohn, 2016; Thani et al., 2016; Mihinjac and Saville, 2019; Saraiva et al., 2021). The following transcript extract from a resident who owns a Security and Alarms Company provides useful insights on potential security features that one can consider in building home defense and seeking to make houses and homes safer:

“Look, residents and everyone must understand that criminals are out there on the prowl and looking for the slightest opportunity to break into your home, company premises, car etc., and take valuables and property. What I would advise and generally advise clients, relatives, families, and friends is that have clear entrances and transparent walls or elevation that allow your home/house or premise to be visible from the main street. Have lighting and if possible, security sensor lights that are triggered by movements. Also having beams and a security system linked to a security company provides a sense of added safety and security. Increasing the layers that intruders must peel through, from the wall, razor wire or electric fencing, or spikes, strong locks and doors, extra door screens, and good burglary to ensure you delay any forced attempts and give you reaction time is important. Having a dog or dogs can also deter criminals and even cats can assist in case of intruders. If you have an alarm system always test that it is working. It also helps to have contact numbers of your neighbors, the police hotline as well as being on the social/community neighborhood watch group platforms. In the event of an attack, you can always alert these systems of networks so that they can be activated for support. In general, also, remember to be vigilant as usually criminals study and comb your area for some time studying all the victim's movement patterns, activities as well as profiling the victim household in terms of composition by age, sex, and other information etc.” Extract of a verbatim interview with a key informant respondent who owns a security and alarm company operating in the study area.

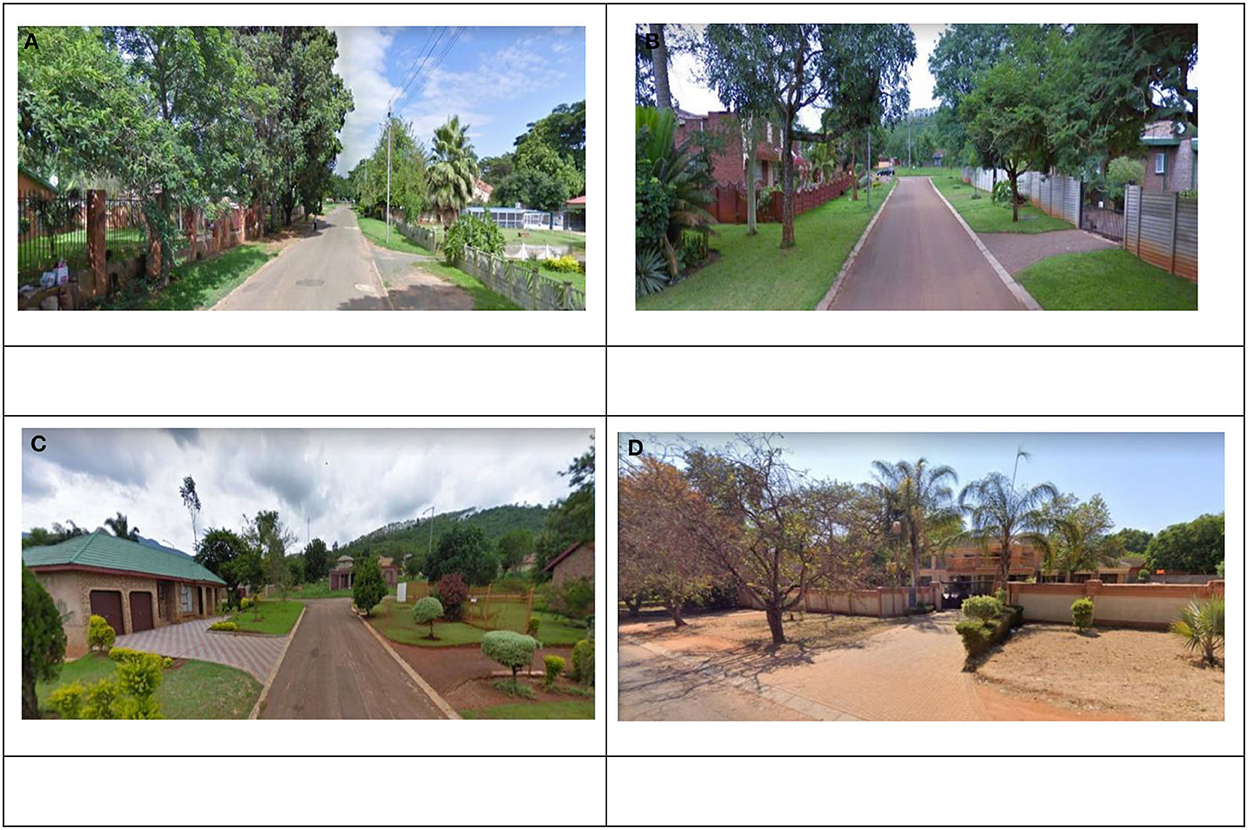

Figure 3 presents streetscapes pictures of different streets in the new town, Louis Trichardt. On the other hand, Figure 4 presents buildingscapes skyline and architectural changes over time in the study area.

Figure 3. Pictures of streetscapes in the new town, Louis Trichardt. (A) Mimosa street: low and open fencing/walling. (B) Rietbok street: no fencing, high and closed durawalls/fencing. (C) Leeu street: no fencing—landscaping, gardening, and elevation. (D) Bauhinia street: high strong walls, electric fence, and gate.

Figure 4. Buildingscapes skyline and architectural changes over time in Louis Trichardt. (A) Modern house with high wall, electric fence, and transparent electric gate. (B) Old style (1970–1980s) house with tree and steel open fencing and gardening. (C) Gated community housing estate with open communal courtyard. (D) Modern double storey building—open and closed landscaping and elevation security designs at play.

Different households and residents have erected different types of security systems (Figure 3). These range from low transparent walls and open fencing for increased inside and outside surveillance, to high closed off walls in which both inside and outside surveillance are blocked and extremely curtailed usually accompanied by electric fences, CCTV camera, and armed response security teams' subscription and protection. The main private armed response security companies operating in Louis Trichardt and the study area are Big 5 Security Company, DRS Security Company, and TMS Security Company among others. Similarly, at the same time, buildingscapes skylines have evolved over time with a mixture of open and closed building systems being constructed and developed in the study area (Figure 4). The issues of securityscapes, neighborhoodscapes, streetscapes, blockscapes, and mapping riskscapes are matters that have also been investigated and identified as critical in seeking to understand barriers in advancing safe communities and neighborhoods. Indeed, barriers to crime, safety, and security are complex, multiple, interconnected, and interdependent, suggesting that solutions to overcoming these barriers need collaborative engagement and partnership of all role players and actors involved in safety, security, crime prevention, combating, and reduction value chain.

4.4. Advancing secure streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes in Louis Trichardt town

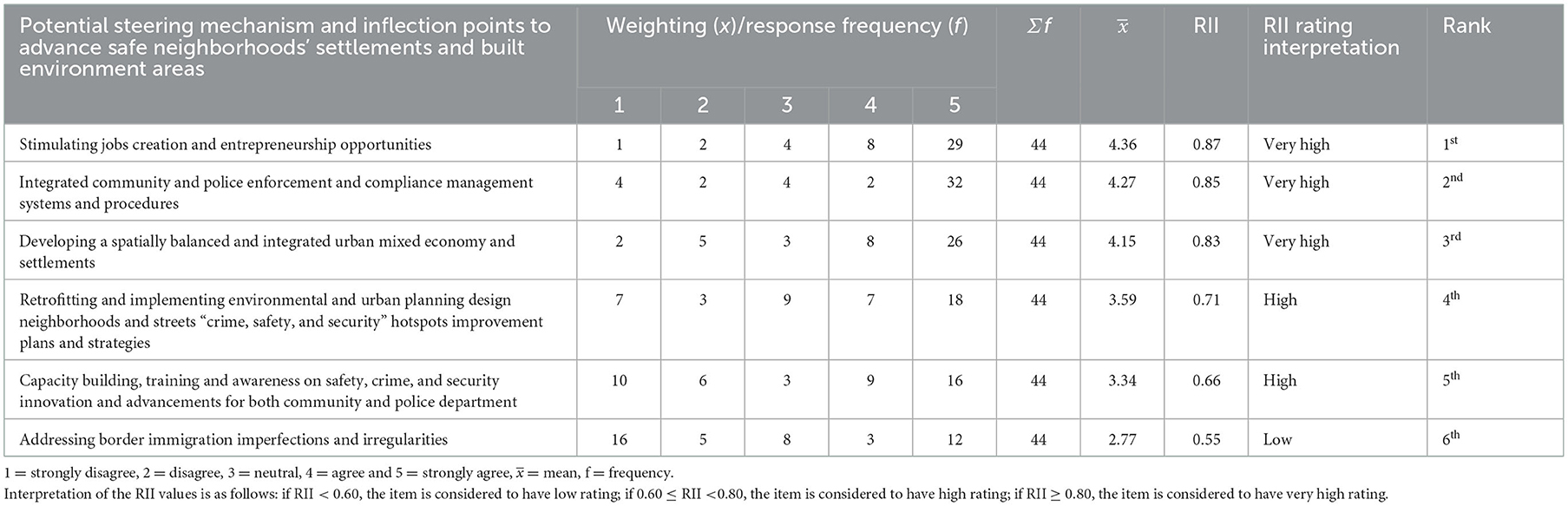

Potential steering mechanism and inflection points to advance crime safe and security streetscapes, blockscapes, and neighborhoodscapes environments were identified from the literature and confirmed by key informant stakeholders of the new town Louis Trichardt neighborhoods' settlements and, thus, were ranked according to their RII (refer to Table 6).

Table 6. Potential steering mechanism and inflection points to advance safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in Louis Trichardt town.

Entrepreneurship, economic growth, innovation, and diversification strategy (RII = 0.87) are at the core of measures and actions meant to advance safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in Louis Trichardt town specifically, but South Africa generally and developing countries in general (refer to Table 6). An economic approach to solving socio-economic problems manifesting in crime, safety, and security plus challenges is not a new approach but a well-established approach (Judd, 2004; Scheider et al., 2012; Soltes et al., 2020). The challenge was to build strong local integrated and balanced economic systems and structures that can foster an environment that encourages job creation and employment opportunities (RII = 0.83) at rates higher than the demand for jobs and employment. The following transcript extract from a key informant who is an urban design and planning expert provides useful insights on how the spatial and mobility turn pathway can be used as a pathway in fostering the existence of safer environments and communities:

“The legacy of the spatial divide and fragmentation in South African cities must be addressed with a greater sense of urgency and velocity than we have witnessed before. The longer we nurse this wound, the longer it will continue to pain and hurt us in so many ways. The situation in which the country remains one of the most unequal societies in the World, with the gini-coefficient hovering around 63 does not do good to various well-meaning efforts by government to tackle poverty, unemployment, and inequality. Given this context, areas of high income are seen as spatial enclaves of wealth and opportunity by criminals who predominantly come from the low-income areas and poverty enclaves, or persons sometimes being labeled as illegal migrants, although crime knows no border, nationality, or race. Urban designers, architects, planners, and various actors involved in the planning, renewal, upgrading and establishment of human settlements should always plan and design the blocks, streets, and neighborhoods with a view for implanting in-built design policing and social surveillance systems in place. Retrofitting designs after plan approval and implementation always places the bigger burden for financial capital investment for upgrades on the residents and to some extent the municipality. In short, many gains in friendly, safer designs and communities can be achieved with participatory urban design planning and the inclusion of multiple disciplines and stakeholders interested in neighborhood, town, and urban planning and development.” Extract of a verbatim interview with a key informant respondent who is an urban design and planning expert in the study area.

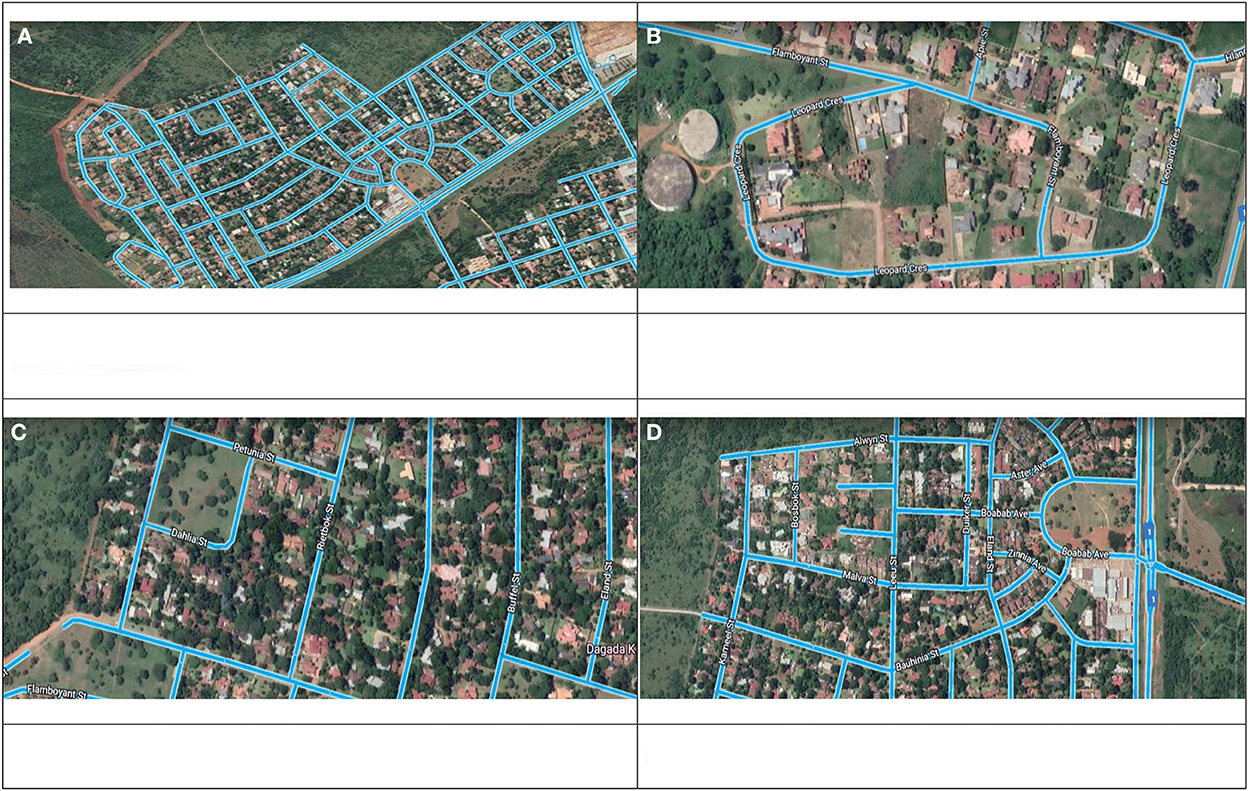

Figure 5 presents 2D mapping illustrations of streetscapes and blockscapes layout and arrangement in the new town residential area, Louis Trichardt.

Figure 5. 2D streetscapes and blockscapes layout and arrangement in new town residential area, Louis Trichardt. (A) Streetscapes and blockscapes aerial 2D view of new town—the proximity of the neighborhood to N1 as well as the block layout and streetscape that encourages permeability, easy accessibility and exit, and ease legibility providing opportunities for quick escape by criminals, especially those that are mobile. (B) Streetscapes and blockscapes aerial 2D view of new town showing vacant/open stands that pose security threat in area. (C) 2D streetscape and layout showing big open space as well as stands bordering farms—which edge farmlands and forests are used by criminals as get-away and hiding nests. (D) 2D streetscape and blockscape showing cul-de-sac and short avenues that enhance neighborhood surveillance and community or street/block policing.

The 2D mapping of streetscapes and blockscapes in new town residential area shows that different forms of planning and design principles were used in the layout and arrangement of the neighborhood (Figure 5). These spatial planning and urban design models are predicated on the need to encourage accessibility, legibility, and permeability, bringing variation in street function, length, size, and distribution with diverse crime and security implications. In trying to maximize place-making connectivity and linkages of neighborhoods, the challenge lies in seeking to balance these principles with the need for safety, security, peace, orderliness, serenity, and the protection of the neighborhood quality of area.

While it can be argued that the ideal would be to design homes and neighborhoods that are crime-related, the reality is criminals are always re-inventing themselves in pursuit of their evil intentions. Interestingly, the findings from the study are consistent with wider literature that highlights the importance of integrated community and police enforcement and compliance management systems and procedures (RII = 0.71). The need for innovation and advancement in police systems (i.e., including harnessing the power of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and its attendant technologies) complementary to integrated community policing systems has been suggested as one way of fighting crime, safety, and security plus issues better and requires further improvement and enhancement continuously (Sadd and Grinc, 1994; Matlala, 2018; Karreth, 2019; Laufs and Borrion, 2021). Overall, finding lasting solutions cannot be complete without also exploring further the role that appropriate safe home designs and streets at the local and site levels in terms of organization and orientation to encourage safer environments are in place (RII = 0.71). Hence, the need for capacity building and literacy programmes on CPTED (RII = 0.66) for both police security and residents remains key (Cozens et al., 2005, 2019; Cozens, 2015; Fennelly and Perry, 2018; Al-Ghiyadh and Al-Khalifaji, 2021). These initiatives could take the form of ensuring that municipalities conscript the Architecture Liaison Officers in the police station and local authorities, whose role would be to assist with advise and liaison on the streetscapes, blockscapes, and neighborhoodscapes safety from an architectural, urban design, and spatial planning perspective. In addition, to provide assessments, suggestions, and guidance for layout and structural design upgrades after crime breaches, they would also conduct pro-active services with respect to assisting in the creation of safe streetscapes, blockscapes, and neighborhoodscapes from a technical service. Competitions and rewards [covering provinces; districts; local municipalities; non-governmental organizations (NGOs); community organizations and groups; primary, secondary, and high schools; Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET), Universities] linked to police label secure housing, confronting xenophobia, violence, and crime with schemes and steering mechanisms that can be linked to home insurance schemes and discounts could be part of an extended home safety and design value chain system. Invariably, home areas with secure police labels or secure by design certification will have in theory higher values, provide a better perceived return on investment, and create a sense of better security and safety systems for the residents. This training can be scaled up to include international training and certification of police officers in CPTED, which currently is not the case in the study area. The South African Council of Planners (SAPLAN) and South African Council for the Architectural Profession (SACAP) could be enlisted by local governments through the South African Local Government Association (SALGA) to assist with pioneering work for the development and piloting of customized crime, safety, and secure house and spatial planning designs, using international benchmarks and practice as a departure point (Stummvoll, 2012; Chiodi, 2016; Kent and Wheeler, 2016; Saraiva et al., 2021). The capacity building and training workshops, covering all geographic scales, sectors of the economy, all inclusive (gender, age, disability) will be essential in making in-grounds to the emergence of positive post-colonial urban resilient and conflict conquering societies.

4.5. Xenophobic violence, crime, and safety in streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes

The matter of xenophobic violence, crime, and safety in South African streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes has been a recurring wave since 2008 (Moyo and Nshimbi, 2020). The lived realities of South Africa project a narrative in which the need to explore how alternative and expanded options and solutions including spatial, urban, block, and building layout designs can be incorporated as technical solutions to resolving the problem. It was argued by one participant that “a smart involvement of the taxi industry in addressing the xenophobia challenge would be a masterstroke.” This was viewed in terms of the taxi industry's ability to manage and being involved in the interface of transporting commuters from residential areas to work and recreational facilities. It was argued that they can form a human shield in fighting xenophobia and even looting shopping malls as they have a stake and are an important component of the value chain of the business and commercial industry as an enterprise. If both the shops and the passengers upon whom their derived transport business is based are negatively affected, then their livelihood and existence are seriously threatened. On the other hand, addressing border immigration imperfections and irregularities (RII = 0.55) was the lowest ranked issue by the respondents as a key driver in seeking to (re)solve streetscapes crime, safety, and security matters in the study area. This finding was unexpected as it ran counter to the mainstream theorization and construct of xenophobia, operation dudula, crime, and security that dominate mainstream mediascapes and literature (Lamb, 2019; Moyo and Nshimbi, 2020). The construct labels and creates an image of clubbing foreign migrant labor and illegal migrant labor together and conceptualizes a foreigners' typology narrative as fueling instability and anger from the public and communities in which they live as they are viewed as stealing jobs and economic opportunities from the locals—creating subtle and visible forms of inter-personal and collective violence that in maturity take the form of xenophobia violence (Lamb, 2019). In probing the participants, they all acknowledged that the presence of (il)legal migrants who were sometimes referred to as foreigners was an expression of the “fear of otherness” in communities (Lemanski, 2006). It was argued by some of the study participants that while it is easy to blame foreigners for crime and violence, the truth on the ground is that “crime knew no nationality, tribe, race, or color” as it was being committed by persons from any background, racial or national descend. Several participants highlighted that they were “aware of a number of incidences in which foreigners or suspected foreigners without any skill or permit (who are, therefore, by an extension (il)legal and undocumented laborers or persons in the country) were involved in crime such as stealing, pickpocketing, and housebreaking.” However, the same participants were much more concerned that these (il)legal migrants and foreigners were vulnerable, cheap laborers, easy prey and pawns exploited through being “under-paid, under-employed” and, therefore, a willing instrument in the capitalism model of economic development as well as being instruments used in committing the crime, taking instructions from well-established syndicates, who were not “foreigners or illegal immigrants in most cases” to begin with. Some participants further argued that to tackle the issue of xenophobia, crime, and security, focusing on illegal migrant laborers or persons was an incomplete approach and perhaps by and large missing the real socio-economic inequality issues that needed priority and redress. This corroborates similar findings on the mechanism to solve xenophobia requiring integrated and comprehensive solutions covering the gamut of social justice, social cohesion, innovations on foreigner-citizen working models of contact, internalized racism discourses, socio-economic poverty and inequality, strengthening training and compliance on immigration and refugee laws, nationalism and post-urban colonies development dilemmas, township and informal settlement dynamics, governance, and politics (Ejoke and Ani, 2017; Kerr et al., 2019; Ngcamu and Mantzaris, 2021). It was in the opinion of one of the participants “focusing on the symptoms of the problem, instead of focusing on the root and trunk causes of the problem.” These findings corroborate prior findings on vigilantism, violent protests, and xenophobia in South Africa, especially from poor communities in South Africa, in which it has been argued that the violence may have been orchestrated by perverted constructs of social cohesion galvanized and trumpeted on the genuine socio-economic inequalities and service delivery inadequacies in communities (Kerr et al., 2019; Lamb, 2019). A possible explanation to the findings and drift in understanding and exploring the views of the participants in the study area being different from perceived mainstream literature discourses on xenophobia in South Africa can be explained from many folds: (1) the case study area, new town residential area, is a high-income and affluent area; (2) Louis Trichardt town is home to a healthy mixture of both highly skilled and expert professionals who mix with ordinary community members in various socio-economic activities presenting multiple opportunities for engagement, communication, and integration; (3) the region displays very strong inter-generational socio-economic historical lineage, inter-marriages, and cultural background ties shared between the former pre-colonial nation-states of Great Zimbabwe (Zimbabwe) and Mapungubwe (Limpopo, South Africa); and common languages of TshiVhenda are spoken across the two countries, with Shangaan, Tsonga, Ndebele, Tswana, Sotho/Pedi, and Khoisan being common languages spoken between nationalities of the two countries, especially in Matabeleland South, Zimbabwe. In addition, the Venda grammar language shares similarities with Shona dialects, which are spoken in Zimbabwe. The study area, therefore, represents a classical example in which better social cohesion and community integration can be attempted showing the prospects for confronting and taming xenophobia, violence, and security to some extent, with such peaceful co-existence of people from different cultures and backgrounds, challenging, and extending the decolonial critique on post-apartheid and colonies violence (Ngcamu and Mantzaris, 2021; Furtado, 2022).

4.6. Complexities in tackling violence, crime, and safety in streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes

Efforts aimed at tackling violence, crime, and safety in streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes face multiple and complex challenges at all levels and geographic scales. These challenges should rather be viewed as opportunities rather than terminal barriers to solution generation. Potential solutions range from physical, social, economic, and environmental, to political. However, there are always limitations to social cohesion and integration as this is influenced by all stakeholders' willingness and readiness to engage in assimilation, emigration, semigration, or integration (Ballard, 2005). The spatial distribution of safety, security, and crime affecting both the public and private domains require a joint or one governance approach pitched generally at three levels:

• The city level, i.e., in respect of exploring and understanding better the socio-economic and spatial differences between areas and districts with a view to creating balanced, competitive, and self-sustaining and interlinked productive economies.

• Crime, safety, and security plus action, measures, strategies, spatial plans, interventions, and programmes should be focused on the scale to address the required area or district, sub-district, neighborhood, street, block, and precinct-level needs in terms of diversity, inclusivity, difference, and integration so that urban economic and social patterns, goods flow, commodities exchanges, and trade lines are not skewed in fewer or one district or area. This suggests the importance of differentiated and appropriate decentralized spatial targeting and balanced spatial development to foster a more stable, just, and equitable society in which the inequalities are reduced and brought to tolerable levels that do not spark and generate crime, safety, and security to spiral out of control and reach of curation by existing systems and machinery in place meant to resolve the problem.

• The public space level and realms should be planned, designed, and revitalized in terms of the dynamics of multiple and changing activities, users, and supporting the sustainable environment use and ecosystems of both public and private spaces. The participatory approach is central to generating solutions that are transparent, comprehensive, and inclusive of everyone.

4.7. Study limitations and areas for future research

Crime, safety, and security in blockscapes, streetscapes, and neighborhoodscapes are complex social, economic, environmental, physical, and political phenomena that require cross-cutting and integrated spatial planning, environmental design, and reassurance policing, including community policing to reduce the problem. However, crime, safety, and security can be viewed as an extension of the socio-economic and development inequalities and disparities that require sharper and better structured national, regional, and local spatial growth and development frameworks, plans, and programmes, aimed at tackling the root causes and creating sustainable platforms for efforts by the police to be meaningful and appreciated. This study did not cover the following aspects that can be the focus of future studies and investigations:

• The current study was more of a temporal scoping study and conducting a longitudinal study covering the study area for a long time could be very revealing in terms of findings and policy making. In addition, this study was a case study of Louis Trichardt's new town residential suburb. A full-scale study of Makhado may be exciting, together with comparative district, provincial, and national studies.

• Thematic study on crime, safety, and security of gender, youths, aged, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ), and persons with disabilities is a potential area for further studies at the local, national, and international levels.

• A detailed CPTED study that seeks to gain a deeper understanding in terms of the urban planning, design, and management of the blocks, neighborhoods, towns, and other towns could also provide interesting insights.

• The study did not tackle safety, security, and crime in informal settlements and neighborhoods, urban decay, or blighted inner city residential areas. Future research can explore these aspects for policy planning, design, management, and learning,

However, an attendant but important aim of this study was to stimulate and focus the debate on this important topic with a view to encouraging continued discussion, dialogues, debate, and studies to better inform policy and planning. In addition, given that the study was conducted on operation dudula1 in the South and is a movement in which inequality is at the center of initiatives to remove illegal/undocumented migrants in South Africa. A follow-up study telescoping the movement and how the narrative has played out in the study area and other parts of South Africa is an area for further research.

5. Concluding remarks

The study has the advanced policy and planning implications for further entrenching enhanced safety, security, and crime in the existing and future design and development of residential areas in the study area. The study has concluded that the needs, barriers, and solutions of safety, security, and crime for creating safer and (re)configured streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes are complex and multidimensional matters. Potential action and measures that have been implemented to date include (re)solving improvements including crime prevention through environmental design, neighborhood design, surveillance, homeownership potential development; social interaction, and improvement in the concepts of territoriality, surveillance, and integrated policing and neighborhood watchdog cooperation, collaboration, and partnership (Atkinson and Flint, 2004; Atkinson and Ho, 2020; Brower, 2020; Makinde, 2020; Morales et al., 2021). However, the challenge with current efforts and attempts is that instead of facilitating social cohesion and integration of communities and societies, such privatization and securitization of public spaces through strong private, social, and community groups/associations has tended to internalize and domesticate new forms of “apartheid,” “segregation and fragmentation.” While in the study area, given the area's predominantly cosmopolitan and multi-racial nature, the private, social, and community groups/associations have tended to operate above racial and xenophobic lines, providing evidence that socio-economic inequalities challenges in any area can be addressed without fanning and drawing appeal to xenophobia, violence, and crime; however, this is not the case in other areas of South Africa, especially low-income residential neighborhoods. Developing xenophobia, violence, and crime safe places, and spaces (both physical and virtual) including creating platforms, theater, and drama platforms to address and debate openly the challenges of xenophobia, violence, and crime are critical areas requiring continuous development. Workshops, seminars, webinars, round-table discussions, and pilot and demonstration projects that showcase the beauty of economies of scale as contrasted to diseconomies of scale; advantages of stable economies vs. fragile and broken economies; perceived advantages and disadvantages of xenophobia, violence, and crime in the short, medium, and long term, including incorporating inter-generational conversations and voices, piloting and retrofitting blockscapes, streetscapes, neighborhoodscapes, and sprucing up urban design and spatial planning interventions to have in-built and targeted xenophobia, violence, and crime fighting back and building better community systems are critical. There is a need to institutionalize, rationalize, align, and internalize xenophobia forums and dialogue groups not as an ad hoc and knee jerk reaction to each and every isolated xenophobia violent event but be a strategic, operational, and tactical social building, community integration tool and strategy that constitute part of the growth and development milieu of an area such as housing upgrading programmes and projects in low-income areas, extension of care and humanitarian training components in executing expanded public works programme, international training on CPTED for police and community liaison officers as ways of encouraging community ethics of care, humanity, safe home design, and places and neighborhoods in low-income groups/areas. Addressing the safety, security, and crime issues can also be made by harnessing the advantages of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The mobilities turn and impact of drones and big data in terms of smart homes, smart places, and culture management are key issues that require further investigation for better understanding and tackling the need for building resilient and safer environments. This may entail the need to up-scale the application and piloting of smart urban and rural safe environments and communities in tackling crime at all levels. In this context, the (co)production of knowledge, information, and innovation should transcend traditional disciplines and bilateral relationships with interested stakeholders to have improved relationships among public service clients and other stakeholders (Manzi and Smith-Bowers, 2005; Bovaird and Loeffler, 2012).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

The communities, key informants, and stakeholders from Makhado Local Municipality are greatly appreciated. The peer reviewers for constructive criticism resulted in tremendous improvement of the final published article. Dr. Beacon Mbiba and Prof. Thulisile N. Mphambukeli for encouraging me to contribute.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^“Dudula” means to “force out” or “knock down” in isiZulu and, therefore, refers to the movement's goal and target as to expel immigrants especially undocumented/illegal immigrants from South Africa.

References

Adugna, M. T., and Italemahu, T. Z. (2019). Crime prevention through community policing interventions: evidence from Harar City, Eastern Ethiopia. Humaniora 31, 326. doi: 10.22146/jh.44206

Agbola, T. (1997). The Architecture of Fear: Urban Design and Construction Response to Urban Violence in Lagos, Nigeria. Geneva: Ifra. doi: 10.4000/books.ifra.485

Akesson, B., and Basso, A. R. (2022). From Bureaucracy to Bullets: Extreme Domicide and the Right to Home. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. doi: 10.36019/9781978802759

Al-Ghiyadh, M. A.-K., and Al-Khalifaji, S. J. N. (2021). “The role of urban planning and urban design on safe cities,” in: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Tokyo: IOP Publishing), 012065. doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/1058/1/012065

Alvi, M. (2016). A Manual for Selecting Sampling Techniques in Research. Karachi: University of Karachi, Iqra University. Available online at: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/70218/ (accessed September 10, 2022).

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity At Large: Cultural dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Appadurai, A. (2010). How histories make geographies. J. Transcult. Stud. 1, 4–13. doi: 10.11588/ts.2010.1.6129

Appleyard, D. (1979b). The environment as a social symbol: Within a theory of environmental action and perception. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 45, 143–153. doi: 10.1080/01944367908976952

Argandoña, A. (2018). The Home: Multidisciplinary Reflections. Working Paper, WP-1183-E. University of Navarra, Madrid, Spain.

Aston, E., Wells, H., Bradford, B., and O'Neill, M. (2022). “Technology and police legitimacy,” in Policing in Smart Societies, eds A. Verhage, M. Easton, and S. De Kimpe (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 43–68.

Atkinson, R., and Flint, J. (2004). Fortress UK? Gated communities, the spatial revolt of the elites and time-space trajectories of segregation. Housing Stud. 19, 875–892. doi: 10.1080/0267303042000293982

Atkinson, R., and Ho, H. K. (2020). “Segregation and the urban rich: enclaves, networks and mobilities,” in Handbook of Urban Segregation, ed S. Musterd (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing).

Babbie, E. R. (2020). The Practice of Social Research, Cengage Learning. Boston: Chapman University.

Ballard, R. (2005). Bunkers for the Psyche: How Gated Communities Have Allowed the Privatisation of Apartheid in Democratic South Africa. Cape Town: Isandla Institute.

Bank, L. J. (2019). City of broken dreams: myth-making, nationalism and the university in an African motor city (Ph.D. dissertation). York University, Toronto, ON.

Beck, A., and Chistyakova, Y. (2002). Crime and policing in post-Soviet societies: bridging the police/public divide. Policing Soc. 12, 123–137. doi: 10.1080/10439460290002677

Beck, A., and Robertson, A. (2003). Crime in Russia: exploring the link between victimisation and concern about crime. Crime Prev. Commun. Saf. 5, 27–46. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.cpcs.8140137

Beck, A., and Willis, A. (1995). Crime and Security: Managing the Risk to Safe Shopping. Cham: Springer.

Beck, B. (2019). Broken windows in the cul-de-sac? Race/ethnicity and quality-of-life policing in the changing suburbs. Crime Delinq. 65, 270–292. doi: 10.1177/0011128717739568

Blandy, S. (2018). Gated communities revisited: defended homes nested in security enclaves. People Place Policy 11, 136–142. doi: 10.3351/ppp.2017.2683778298

Boboyorov, H. (2018). “If It Happens Again”: everyday responses of the ruszabon to existential dangers in Dushanbe. Int. Q. Asian Stud. 49, 61–82.

Bovaird, T., and Loeffler, E. (2012). From engagement to co-production: the contribution of users and communities to outcomes and public value. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Vol. Nonprofit Organ. 23, 1119–1138. doi: 10.1007/s11266-012-9309-6

Branic, N., and Kubrin, C. E. (2018). Gated Communities and Crime in the United States, eScholarship. New York, NY: University of California.

Breetzke, G. D. (2018). The concentration of urban crime in space by race: evidence from South Africa. Urban Geogr. 39, 1195–1220. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2018.1440127

Brower, S. (2020). Neighbors and Neighborhoods: Elements of Successful Community Design. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781351179126

Buus, S. (2009). Hell on earth: threats, citizens, and the state from Buffy to Beck. Cooper. Conflict 44, 400–419. doi: 10.1177/0010836709344446

Chakwizira, J., Bikam, P., and Adeboyejo, T. A. (2018a). Different strokes for different folks: access and transport constraints for public transport commuters in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Int. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 8, 58–81. doi: 10.7708/ijtte.2018.8(1).05

Chakwizira, J., Bikam, P., and Adeboyejo, T. A. (2018b). Restructuring Gauteng City Region in South Africa: Is a Transportation Solution the Answer? An Overview of Urban and Regional Planning. London: IntechOpen, 83–103. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.80810