- 1Department of Politics and International Relations, Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 2Department of Peace Security and Society, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe

This article examines the complexities around urban informality, in particular illegal street vending in post-colonial Harare in Zimbabwe from 2000 to 2021. It focuses on the positions of the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front party and the Movement for Democratic Change opposition political party regarding illegal street vending. The study acknowledges the role played by the broader macro-economic environment in initiating and sustaining informal trading practices in the City of Harare but establishes the link between illegal street vending and politics and the concomitant effects on human security. Among others, it uses Ananya Roy's ideas about how the state “makes and unmakes” informality and primary and secondary sources of data to mainly argue that the political exploitation of the illegal street vending activities in Harare has detrimental effects on both urban governance and human security. The article concludes that illegal street vending is an integral part of urban societies in Africa and beyond serving different needs in the local economy. Consequently, the politicization and human (in) security of the illegal street vendors in Harare can partly be mitigated when formal employment is generated and political parties stop interfering in the running of the city for the furtherance of their selfish agendas.

Introduction

In the last 21 years Zimbabwe's urban centers witnessed a phenomenal growth of illegal street vending (ISV), particularly in Harare. It is estimated that 5.9 million people out of a total of the 6.3 million working in Zimbabwe work informally (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, 2015: 82). On the other hand, in 2016 the total number of street vendors in Harare was estimated to be 20,000 for the Central Business District (CBD) alone (Daily News Staff Writer, 2016; Moyo, 2017). Both central government and the Harare City Council (HCC) have time and again abortively attempted to get rid of ISV activities through the forcible eviction of the street vendors. In resisting the attempts to push them away from the streets, the street vendors mainly argued that they lacked other means to survive (Kadirire, 2017). The sincerity of the street vendors' argument has seen political players seeking to deviously instrumentalize it and rendering futile the need to maintain the “sunshine status” of Harare. This has generated the curiosity to articulate the link between ISV and politics and the concomitant effects on urban governance and human security in Harare.

Though informality has been conceptualized in diverse ways (see, Chen and Carre, 2020: 4–5), this article discusses ISV as a particular part of the informal sector. In this study, ISV refers to the unlawful selling of goods and services on the streets by informal traders. It is not the same with formal or lawful street vending which is a registered activity, and works within a government or local authority regulated framework (see, Roever, 2020: 173–174). For Jimu (2004: 19), street vending is whereby people sell goods and services to the public from non-permanent or movable structures which can temporarily be set up or relocated. The Urban Councils Act of Zimbabwe (Government of Zimbabwe, 2002) defines ISV as the public selling of goods from one or several fixed places.

It is noteworthy that ISV is discussed in this study mainly as the outcome of economic and political interplay and is illegal solely because of political decisions. According to Chen and Carre (2020: 1), “Historically, all employment, businesses and economic activities were informal until policies and laws were introduced that created a divide between formal and informal, that is, between economic units that are registered with relevant administrative authorities and those that are not and between workers with employment-based social protection and those without.” While this study predominantly has a legal and normative view of street vending as part of the informal sector, it also considers ISV, akin to other informal practices, as an outgrowth of a formal economy's failure to accommodate everyone and continues to be seen as unlawful and insignificant by (misguided) authorities. Progressive and contemporary conceptualizations of street vending and informality suggest that:

…it is no longer formal-informal as two distinct categories of analysis, but as part of a complex set of interrelations that overlap, fragment, multiply and unite at different times. In this way it could be said that the study of street vending and informality in general goes from being analyzed as a static condition linked to structural problems such as poverty and marginalization to being a highly dynamic practice that is in continuous negotiation in daily life, involving multiple urban actors, from state regulatory actors – such as political-administrative units, police – to neighbors, consumers, other street vendors, established merchants and tourists (Crossa, 2020: 169).

Scholars have increasingly focused on the interface between urban governance and politics in Zimbabwe (McGregor, 2013; Magure, 2015; Muchadenyika, 2015a,b; Muchadenyika and Williams, 2016, 2017; Kamete, 2017). This study complements the few scholars who have delved into the effects of the politicization of urban government, particularly ISV (see, e.g., Ndawana, 2018; Hove et al., 2020). Other previous works largely focus on evictions, relocations and daily struggles in the informal economy in Zimbabwe (Kamete, 2006, 2010; Potts, 2006; Musoni, 2010). This article discusses how political parties have sought to abuse ISV to achieve political gains and the concomitant effects on human security. It largely focuses on the positions of the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) party and the opposition political party, Movement for Democratic Change initially led by Morgan Tsvangirai (MDC-T) regarding ISV.1 The central argument in this article is that though the politicization of ISV is not the primary cause of its emergence and proliferation, it has contributed to the lack of effective solutions with detrimental effects on both urban governance and human security. The ISV development is mainly a result of the economic downturn and loss of formal jobs and livelihoods. The article concludes that ISV is an integral part of African and many other developing countries' urban societies serving different needs in the local economy. Consequently, the politicization and human (in) security of the illegal street vendors in Harare can partly be mitigated when formal employment is generated and political parties stop interfering in the running of the city for the furtherance of their selfish agendas.

The study is relevant for broad discussions on informality by scholars and policy makers, especially those working on debates on the intersection of politics and informality and urban governance in Zimbabwe and beyond. Academic work seeking to understand some of the complexities around ISV as part of the informal economy is important in many ways. Among others, none of the four dominant schools of thought on the informal economy debate, namely: the dualists, structuralists, legalists and voluntarists, is adequate on its own to explain the heterogeneity and intricacy characterizing the sector. Although each school articulates the informal economy's causes, configuration, nature and possible solutions differently and has merit, each just reflects a small part of the entire story [for a summary of different analytical positions on informality, see, Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO), (n.d.); Marinescu and Valimareanu, 2019]. Furthermore, all the aforementioned schools of thought view informality with concern emanating from, among other issues, poor working conditions, disregard of the rule of law and low-productivity enterprises characterizing practices in this sector (Perry et al., 2007: 1, 21). This has partly hindered the mobilization and development of the sector's potential with far reaching effects on human security.

The article consists of seven sections. Apart from this introduction, the article discusses the role of the state in influencing the nature and extent of urban informality in third world countries. This serves as the conceptual framework of the study. The third section discusses the methodology used for this study. The fourth provides the evolution of Zimbabwe's economy since 1980 and the challenges that have hindered the growth of formal employment. The fifth section examines how political parties in Zimbabwe have treated urban informal workers, especially those in ISV as assets or liabilities over time and the related consequences on urban governance and human security. The sixth section provides some alternatives to the criminalization of ISV activities in Harare. The last section is the conclusion.

The State and Urban Informality in Third World Countries

This study is mainly informed by the ideas of Roy (2011) about how the state “makes and unmakes” informality. Roy (2011) has challenged scholars studying the invention of street vending practices to do so through what she terms “informal urbanism.” This denotes reconsidering the approach scholars engage with and hypothesize from subaltern spaces, because “subaltern” has been identical with poverty, slums, informal settlements and subaltern matters. All these outlines leave the informal remaining identical with poverty and even marginality. It continues as “the territory and habitus of subaltern urbanism” (Roy, 2011: 233). Still, “subaltern urbanism provides accounts of the slum as a terrain of habitation, livelihood, self-organization and politics” (Roy, 2011: 224).

Focusing “on the limits and alternatives to subaltern urbanism,” Roy (2011: 223) presents “peripheries,” “urban informality,” “zones of exception,” and “gray spaces” as different theoretical classifications to main descriptions of the mega city and subaltern spaces, mostly accounts about “slums” and “slum dwellers” in the Third World. Roy's background and scale somewhat shares a lot with the ISV context in Harare (citizens of a global south country in spaces of their capital). This makes Roy's (2011) work on rethinking our understanding of urban informality highly useful in analyzing the effects of the politicization of ISV in Harare on urban governance and human security. Noteworthy is that urban governance as used in this article denotes a relentless process filled with both cooperation and tension over decision making about the designing, funding and management of urban areas by the government (local, regional and national) and interested parties (Ndawana, 2018: 254).

On the other hand, human security simply refers to the protection from lingering threats, including hunger, disease, and repression, as well as unexpected and upsetting disturbances to everyday life patterns [United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 1994: 23]. Its key objective is “to safeguard the vital core of all human lives from critical pervasive threats” (Alkire, 2003: 22). Many countries have developed different measures of human security including getting responses about context-specific threats such as community, economic, environmental, food, health, personal and political security (Owen, 2003). This suggests that human insecurity is the anti-thesis of human security. Leaning and Arie's (2001) conceptualization of human insecurity as comprising mainly two elements is suitable for the analysis in this study. The first encompasses the essential materials needed for survival such as food, water, shelter and safety. The second one comprises the psychological and social element with three categories, namely, a sense of feeling at home, a connection to community and a perception of optimism. A dearth of the foregoing elements signifies human insecurity. Though the ISV phenomenon has been recognized as “one aspect that has complex effects (both positive and negative) on the survival of both the individual, society (including the business community) and the state at large” (Hove et al., 2020: 73), this study is mainly concerned with its effects on the survival of the individual.

Subaltern urbanization, according to Roy (2011), displays that informality has to be understood beyond subaltern subjects jointly protesting, fighting the state, plus accepting subaltern subjects as courageous entrepreneurs. As an alternative, Roy (2011: 233) challenges urban researchers to hypothesize informality as a “mode of the production of space” and thus not separate from fluid and temporal “formal” state-sanctioned developments. For Roy (2009: 8), informality entails “a mode of production of space defined by the territorial logic of deregulation. Inscribed in the ever-shifting relationship between what is legal and illegal, legitimate and illegitimate, authorized and unauthorized….” Specifically,

The valorization of elite informalities and the criminalization of subaltern informalities produce an uneven urban geography of spatial value. This in turn fuels frontiers of urban development and expansion. Informalized spaces are reclaimed through urban renewal, while formalized spaces accrue value through state-authorized legitimacy… This relationship is both arbitrary and fickle and yet is the site of considerable state power and violence… In this sense, urban informality is a heuristic device that serves to deconstruct the very basis of state legitimacy and its various instruments: maps, surveys, property, zoning and, most importantly, the law (Roy, 2011: 233).

This clearly demonstrates that developments of urban informality are not fashioned disjointedly from state-approved formal processes of urbanization or economic empowerment. In this regard, urban informality exposes prospects of understanding legal/illegal developments as active temporal relations that generate uneven geographies.

In addition to the usefulness of Roy's (2011) work on rethinking urban informality in Harare, the study also draws on the work of Potts (2008) on the state and urban informality in Africa. Potts (2008) examined changes in attitudes toward the role of the urban informal sector in sub-Saharan Africa over contemporary decades. The scholar found that there are profound dynamics of the informal sector and the shifting role of the African state in encouraging or discouraging it in which there is a growth in the negative trend in this respect. Specifically, the urban informal sector was originally seen negatively, especially during the colonial era and early years of independence when it was seen as largely “unmodern.” In the early years of the post-colonial era, which is used here to simply refer to the period after colonial rule (for debates and other meanings of the term post-colonial, see Shohat, 1992), there were shifts in the perceptions of the sector in the face of increasing urban poverty, particularly after the adoption of structural adjustment programmes. During this time, the urban informal sector was seen as a potential safety-net resulting in it receiving favorable policy recommendations.

In recent years, African governments have reverted back to viewing the urban informal sector in the negative sense—something that points to questions around social justice. Social justice in this context entails an unambiguous commitment to equality in different urban domains, including but not limited to economic security, health and housing, that constitute what Weaver (2018) has described as social citizenship. Informality remains tied to state policy in Africa and other parts of the world not necessarily because the state is weak or fragile but its deliberate policy. The state “decides which aspects of the informal economy to turn a blind eye to, which to tolerate or which to get rid of; and which aspects of the informal economy to support or promote” (Chen and Carre, 2020: 24).

The case of ISV in Harare raises useful debates about the state's power to make and unmake urban informality and that this process is not politics free. The term political exploitation is used in this study to describe the use of the vulnerability of a section of people for political gain by political parties and officials. Though the term exploitation generally refers to the use of an individual's susceptibility for one's own good, it is not always negative (for details, see, Mitchell and Munger, 1993; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2016). Still, in Harare, the dominance of politics has not only rendered the role of the state in urban governance problematic to find durable solutions to the challenge of ISV but furthered human insecurity.

This study is also informed by the deep-rooted dualist school-inspired understanding of the involvement in the informal sector as representing a survival strategy poor people adopt as a desperate measure to support their families economically. According to Potts (2006: 288), dependence on the informal sector by the urban poor is not optional, but absolutely essential, particularly when formal jobs could either be not found or are found but paying inadequately to meet basic costs of urban living. It was in these circumstances that urban informality emerged and proliferated in Harare and Zimbabwe in general thus poverty was the central root cause and driver. Consequently, it is foolhardy to embark on state or any other form of interventions targeting eliminating urban informality, especially ISV, and its related negative effects without addressing the macro-economic environment that generated it in the first place. Similarly, Brown (2011) observed that because urban space is a vital resource for underprivileged households it should not be overlooked in the perspective of sustainable development. It is the failure of official policy and regulations to identify its (urban space) significance that hinders the ability of the urban poor to benefit themselves. Many state policies deliberately exclude the informal sector through totally ignoring and overlooking or undervaluing informal workers' invaluable contributions to urban economies and human security. For instance, informal workers significantly contribute to food security and wellbeing of the urban poor through selling food and other goods and services at cheaper prices and convenient locations and city revenue when they pay market rents and operating fees as well as value added tax (VAT) and related sales taxes charged on the inputs they buy in their efforts to eke a living (Chen and Carre, 2020: 25).

As this study shows, the ZANU-PF government vacillates between being tolerant to urban informality and outlawing it informed by the political conditions on the ground but all meant to ensure its continued rule. Though the politicization of urban informality is not the primary instigator and its reversal the guarantor of the realization of effective solutions to the ISV development and concomitant negative effects on human security in Harare, it has also contributed to the challenge. Accordingly, both the central government and the City of Harare's efforts seeking to simply outlaw ISV, among other forms of urban informality and their connected consequences, without addressing the root causes of urban poverty, that is, shortage of gainful formal employment, that initiated and is sustaining it, should be seen as misguided and the main reason for their failure and worsening of street vendors' human insecurity.

Methodological Considerations

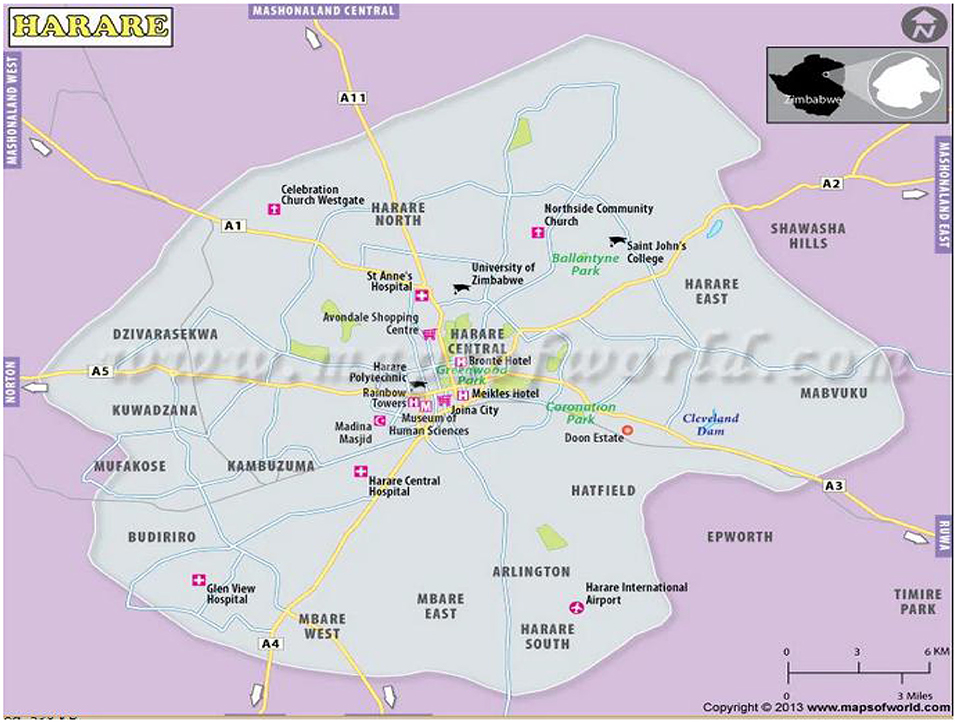

This study utilized a qualitative research approach and a case study research design. The former was adopted mainly for offering a rich and in-depth account of the social phenomenon under inquiry apart from being associated with the latter (Yin, 2014: 19). The single case study research design was chosen for the reason that it allows concentration on a specific case resulting in the development of in-depth and extensive data about it while remaining with a comprehensive and real-life viewpoint (Yin, 2014: 16). The study's data was collected through the analysis of both primary and secondary sources of data. Documentary sources of data used in this study were not synonymous with secondary sources but included primary sources. This is because they not only consisted of published academic works but non-governmental organizations and government published reports and newspaper articles from both private and state owned media that captured official statements, speeches and interviews of both street vendors, political parties and government (both local and central) officials regarding the complexities of ISV in Harare. Both primary and secondary sources were analyzed to get relevant data on the background to the current study, and this helped the researcher to tap into what other existing published case studies connected to the topic say (Yin, 1994: 85). This allowed the collection of data beyond Harare, the geographical area of study whose map is shown in Figure 1. The collected data was analyzed thematically focusing on the developments, changes and continuities and challenges and prospects on how the main political parties and government deal with ISV in Harare and the concomitant consequences on urban governance and human security.

Figure 1. The locality map of Harare. Source: Maps of World, Harare: Zimbabwe, https://www.mapsofworld.com/zimbabwe/harare.html.

Some of the limitations of the collected data include the researcher's failure to conduct own face-to-face interviews and reliance on newspaper articles, which partially capture the voices of the concerned people in this study. These limitations have been mitigated to the extent possible through the use of a combination of newspaper articles from both private and public media and peer reviewed works, which promoted the authenticity of the study's findings. A qualitative case study permits the exploration of a phenomenon in its setting using available sources of data (Yin, 1994: 85). Thus, this study's findings are credible because they are the outcome of the use of a combination of relevant sources.

The Evolution of Zimbabwe's Economy Since 1980 and the Contraction of Formal Employment

The ISV phenomenon in Zimbabwe emerged following independence in 1980. Before 1980 the country's economy seemed to have been stable and vibrant, backed by extensive industrial, commercial, agricultural and mining activities all of which were largely formal enterprises (Mhone, 1993: 1). While by sub-Saharan Africa standards Zimbabwe at independence took over a fairly sophisticated and diversified economy, it increasingly suffered huge investment decline and low economic performance, high unemployment, price controls and a dearth of foreign currency (Tibaijuka, 2005: 16). Consequently, informal economic activities had begun to take root from around 1975 when the economy suffered from the effects of the liberation war, whilst some reforms and adjustment of discriminatory laws led to greater urbanization (Brett, 2005: 93). The existence of some laws that prohibited the uncontrolled movement of black Africans into urban areas (Dhemba, 1999: 12) partly explains why the urban informal economy in Zimbabwe (then southern Rhodesia) remained relatively low at not more than 10% in 1980 [Mazingi and Kamidza, (n.d.): 327].

The first decade of independence largely witnessed economic growth that averaged 5.5%. It was driven by “growing domestic demand, as workers' wages were increased due to government interventions, government's redistributive policies that saw a vast expansion of education and health facilities, and the opening up of external markets, among other factors” (Mlambo, 2017: 103). However, the new government and its associated socialist oriented policies and increased regulation of business affected formal business and generated unemployment (Carmody, 1998; Kamete, 2006; Ranger, 2007). Unemployment increased and was ~20% by the close of the first independence decade (Brown, 2011: 324). This development resulted in the introduction of the freedom to do business in some areas where it was previously prohibited. The establishment of some sites for doing such business started the expansion of the informal economy (McPherson, 1991: 1). In some way, these were the early signs that the Zimbabwean government can tolerate informality.

The government's embracing of the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP) by the close of 1990 in an effort to revamp economic investment and growth through a number of liberal measures including the removal of price and exchange rate controls, privatization of public enterprises and trade liberalization worsened the situation in the second decade of independence (Mlambo, 2017: 104). A combination of factors culminated in ESAP being unproductive and harmful to the Zimbabwean economy it was meant to improve. These ranged from the poor package of ESAP, the severe drought of 1992 and poor implementation of the programme by government (Mlambo, 2017: 104). The resultant slow growth of manufacturing partly due to ESAP actually exacerbated the shrinking of formal employment and the earnest initiation of the informal economy (Brett, 2005: 92). Zimbabwe's informal economy was projected at 59.4% of gross domestic product (GDP) in the 1999–2000 fiscal year while by November 2000 the informal sector was estimated to be supporting 1.7 million people (Mlambo, 2017: 107). Accordingly, Mlambo (2017: 107) notes that “as the economy rapidly contracted, the formal employment sector collapsed and more and more Zimbabweans resorted to the informal sector for survival.” Consequently, ESAP added to the precariousness of livelihoods through social services commercialization, government and private business retrenchments, economic liberalization, increased unemployment, decreased real wages and rising food and fuel costs (Dhemba, 1999: 5). The decline in consumer demand came as a result of the rise in prices that was triggered by the removal of price controls.

Besides ESAP, economic decline took an acute turn in the late 1990s following unwise and unsustainable policy choices which included but were not limited to: the country's involvement in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) war in 1998 and the unbudgeted pension payouts to the liberation struggle war veterans in 1997. The two decisions presumably exhausted the hitherto declining national coffers and led to unparalleled inflation and reduced economic performance. For example, the payouts to war veterans gobbled 9.7 per cent of the government's budget (Richardson, 2006: 3). According to Mlambo (2017: 106), the payouts to war veterans prompted a 74% drop in the value of the Zimbabwean dollar against the United States of America dollar in just over four trading hours on Friday 14 November 1997, now popularly known as Black Friday. Similarly, the decision to intervene in the war in the DRC was unplanned overspending and it led to severe budgetary constraints (Alao, 2012: 155). The combination of the economic debility and the increasing inflation and cost of living levels triggered the December 1997 food riots and strikes. The government responded with cruel measures to quash the strife and, debatably, contributed to the emergence of the MDC-T opposition political party in 1999 (Mlambo, 2017: 106).

In the 2000s, political polarization and disagreements and the fast track land reform programme (FTLRP) in the early years of the twenty-first century that was targeted at redressing the then entrenched skewed colonial land ownership patterns also generated some economic negative effects in the country that were more severe than those of ESAP (Ranger, 2007; Raftopoulos, 2009). The FTLRP of 2000 negatively affected commercial agricultural production, which was arguably the backbone of the country's economy and had subsequent negative effects on industries. The Western countries' retributive response to Zimbabwe's FTLRP with economic sanctions and the accompanying charges of violations of the principle of the sanctity of property rights exacerbated the country's already economic decline (de Jager and Musuva, 2016: 22). Moreover, large volumes of farm workers on commercial farms lost employment (Southern African Migration Project, 2006: 131). Over 300,000 farm workers were left jobless and in most of the cases the new farmers did not absorb them. This development forced the jobless farm workers to either join the growing numbers in the informal economy in towns or engage in gold panning [Mazingi and Kamidza, (n.d.): 349].

The negative economic developments contributed to the rapid increase of the informal economy, such that in 2002 it was projected that not <50% of the national workforce was working in the informal sector (Kamete, 2004). Moreover, the unemployment rate was at 80% in 2004, and the deteriorating economic situation resulted in several company closures. About 800 manufacturing companies ceased operations countrywide since 2002, whereas 25 were stressed and eight faced shutting down in 2004 (Mpofu, 2011: 6; Tibaijuka, 2005: 17). The urban informal economy employed not <76% of the urban workforce in 2004 (Gumbo and Geyer, 2011: 55). About three to four million Zimbabweans were earning their living via the informal sector while ~1.3 million people were formally employed in June 2005 (Mpofu, 2011: 6; Tibaijuka, 2005: 17). A combination of the aforementioned government policies and international responses that saw the significant contraction of formal employment initiated and sustained the informal economy, particularly ISV, in Zimbabwe.

There is no evidence of the decrease of poverty in the country since ESAP. According to Mpofu (2011: 1), urban poverty in Zimbabwe as of 1990/91 was estimated to be 12% but by 1995 it had risen to 39%. Zimbabwe's poverty rate in 2008 was conservatively projected at 70%, whereas unemployment was estimated at 80% (Mlambo, 2017: 106). The record inflation which increased extensively from the late 1990s until it became hyperinflation in 2007 and reached 79.6 billion per cent in mid-November 2008 was the country's greatest challenge (Hove, 2017a: 46). The inflation in Zimbabwe was the product of a combination of years of money printing to fund public costs and quasi-fiscal spending by the central bank (Mlambo, 2017: 107). By January 2009, 10 out of a total of 13 million citizens of Zimbabwe, over 75% of the people, were in despairing poverty (Mpofu, 2011: 1). Roughly 78% of Zimbabweans were unconditionally poor and 55% of the people (nearly 6.6 million) lived under the poverty datum line in April 2010. Over 65% of Zimbabweans were estimated to be living below the poverty datum line in December 2009 (Mpofu, 2011: 1). Mlambo (2017: 107) notes that the creation of the government of national unity in 2009 (until its end in 2013) temporarily assisted in arresting “the free falling Zimbabwean economy.” Nevertheless, the economic state of affairs in the country after 2010 largely continued to be unbearable for the unemployed. Although the economy stabilized following the dollarization of the economy after the failure of the Zimbabwean currency in 2009, formal job development and formation was very inadequate (Mpofu, 2011: 19).

Like in many post-colonial African countries, Zimbabwe's formal job creation continues to be very limited and high rates of unemployment have continued compelling many people to be on the streets trying to sell something to earn a living. Additionally, in 2013 a Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise survey found that there were 5.7 million Zimbabweans employed in the informal economy with 2.8 million as business titleholders and 2.9 million as employees (Mujeyi, 2015: 7). This suggests that the informal economy has turned to be the major employer, accounting for nearly 90% of men and women of working age in the country (Mujeyi, 2015: 7). The unemployment rates in the country further soared because of retrenchments that were experienced in the job market during the last half of 2015 after a land mark Supreme Court ruling that allowed employers to dismiss employee contracts on three months' notice [Zimbabwe Coalition on Debt and Development, (n.d.): 13]. Within a month after the Supreme Court ruling 25,000 formal jobs were lost (Labour Market Profile Zimbabwe, 2015: 4). This further aggravated the number of street vendors in the country's urban centers and accounted for the exponential increase in ISV activities.

The foregoing broader macro-economic outline informs this article's analysis considering that it played a significant role in both initiating and sustaining informal trading practices in Harare and elsewhere in the country. To this end, in an environment marked by desperation as in the case of Zimbabwe, with at least not <80% of the population relying on informal trading, having firm policies on trading sites is not likely to perform any miracles in stopping its continuation. Therefore, the effects of the politicization of ISV in Harare on human security are discussed in the light of the economic problems that Zimbabwe has experienced over the past 21 years.

Illegal Street Vending, Zimbabwean Politics And Human (In) Security In Harare

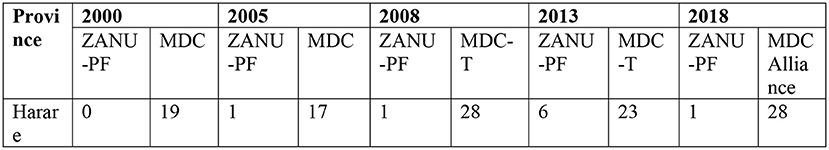

The ZANU-PF government vacillates in its position on, and practices toward, urban informality since the late 1990s. The several concessions to informal workers and housing in the 1990s after ESAP led to the demise of so many formal sector jobs and a related surge in informality were shun in the 2000s following the emergence of the MDC-T as a formidable opposition political party. Here the giving of concessions to urban informality emerged inadequate for ZANU-PF to win urban constituencies which increasingly swung to the opposition. As shown in Figure 2, ZANU-PF has not won more than 6 seats in Harare since 2000. This informed the government's strategy to clampdown on urban informality through, among other interventions, Operation Murambatsvina (OM, Restore Order), which, as we shall see below, was a nationwide militarized clean-up campaign using violent methods to end several urban informal activities, including ISV. Consequently, I put forward that ZANU-PF's actions in dealing with urban informality and ISV in particular, are largely cynical, even Machiavellian (that is, largely interested in retaining power), in its desperate efforts to strengthen its position and extending its rule. So when the ruling party appears to be either on the urban informal sector's side or against it talking of the need to maintain urban orderliness, it is not sincere but seeking to use the sector in a devious way to simply undermine any opposition movements. This is because the party largely draws on pragmatism choosing to uphold or disregard the need for the urban poor to survive through ISV when it sees it fit. Certainly, the ambivalence in ZANU-PF's responses to urban informality since the 1990s is testament to this viewpoint.

Figure 2. ZANU-PF and the MDC-T's performance in parliamentary elections in Harare province between 2000 and 2018. Source: Constructed by the author after synthesizing: Zimbabwe Election Support Network 2000: 89; 2005: 44–45; 2013: 68; 2018: 59.

ZANU-PF and Urban Informality 1980–2000

This subsection briefly demonstrates that the ZANU-PF government's response to urban informality in general and ISV in particular is basically informed by the political climate in the country. This is because notwithstanding some documented cases of evictions of informal settlers in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the ZANU-PF government became tolerant to those people who ventured into the informal economy in the late 1990s because there were no serious political threats (Potts, 2007: 271). This is despite the fact that the 1990 elections witnessed Edgar Tekere's Zimbabwe Unity Movement participating and winning 18% of the votes which came mostly from the large urban areas (Laakso, 2003: 133). According to Dawson and Kelsall (2012),

The “informal” sector expanded rapidly after ESAP as formal employment declined. “Peoples' Markets”, as well as both illegal and licensed vending became ubiquitous. Even here, ZANU-PF was able to utilize access rights to distribute resources to its supporters. While this may be construed as the state decentralizing or partially losing control of rent-management, it is more likely simply a process of extending access to rents into the lower echelons of the party (Dawson and Kelsall, 2012: 55).

The 1990s saw the Zimbabwean government and local authorities responding to the rise in urban informality through negotiating with the urban poor people in order to have them continue surviving thus promoting human security and social justice (Ndlovu, 2008: 218). The government and local authorities saw no liability but assets in the urban informal economy in that the people involved in this sphere were not only viewed as happy to meet their essential needs and had no reason to challenge the government but vote for the ruling party during elections.

Consistent with the idea that informality is inherently tied to state policy, the Zimbabwean government not only enthusiastically encouraged people to benefit and survive from the informal sector in the late 1990s but compelled local councils to ignore enforcing by-laws and permit street vendors to pursue their trade without disruption (Ndlovu, 2008: 218). The government promoted the expansion of the informal sector through a number of policies that included: relaxing regulatory logjams to permit new actors to become involved in the production and distribution of goods and services, assisting local business expansion and black empowerment, and reducing physical planning conditions (Tibaijuka, 2005: 23). Non-residential undertakings in residential areas were effectively endorsed to develop through Statutory Instrument 216 of 1994 of the Regional Town and Country Planning Act. This witnessed the deregulation of many activities including hairdressing, tailoring, book-binding and wood or stone carving (Tibaijuka, 2005: 23). It was the government interventions encouraging the urban informal sector during this period that resulted in an upsurge of the informal sector that made up Siyaso market in Harare. Numerous private flea markets were also created with the approval of government ministers (Ndlovu, 2008: 218). As the article further discusses below, the foregoing progressive trend of leniency toward informality by both the government and urban councils, especially in Harare, since the late 1990s was shunned in the face of ZANU-PF's waning popular support and worsening urban poverty and related human insecurity that occurred in the 2000s.

ZANU-PF and MDC-T Positions on ISV, 2000–2013 and Human (In) Security

While the Zimbabwean government appeared tolerant to informal activities, particularly ISV, in the late 1990s, this position changed in the 2000s following the emergence of a credible opposition and ZANU-PF's loss of control of urban municipalities. For instance, in the 2000 parliamentary elections ZANU-PF did not win a single seat while the MDC-T got all the 19 seats in Harare as shown in Figure 2. The case of OM is engaged because it clearly reveals a strong link between politics and ISV and the related consequences on human security. In fact, ISV was at the center of the other practices of urban informality prevalent in Harare and other major urban centers in the country. It was the ZANU-PF government's view of ISV and the informal sector in general as a liability to its stranglehold on power that informed the execution of OM. Although ZANU-PF saw the informal sector as a liability, it was an asset for the MDC-T for purposes of gaining political support. Since the emergence of the MDC-T the urban areas' susceptibility to collective action as a result of a myriad of challenges including lack of formal employment have largely proved to be a key challenge for ZANU-PF's continued rule and this informed the ruling party's view of the informal sector as a liability.

An examination of the background of what entailed OM, how it was conducted and how it affected the lives of ordinary people bolsters this article's view of ZANU-PF's ambivalence regarding its responses to ISV and related forms of urban informality and its primary concern with retaining power. Among other issues, the urban political landscape since 2000 saw the rise, dominance and control of the MDC-T, opposition political party (through elections) in the functioning of urban activities, to the disappointment of the ruling ZANU-PF party. For Kamete (2006), it was unconceivable for a party in government to be absent as an urban local authority. The elimination of central government representation at the local level drove political players at central government level to become cautious of losing political support, fearing peaceful political extinction. The anxiety originated from the perception of a competitor in formation and political power struggle and the need for continued existence instead of the mere running of local government affairs became dominant (Kamete, 2006: 256). Thus, governance of urban areas came to be hotly disputed and urban councils became significant sites of political struggle. It was in this context that ISV and the informal sector in general was seen as a liability to the ruling party.

The implementation of OM was informed by the increased threats to ZANU-PF rule from the streets. For example, the MDC-T and civil society had called for devastating mass actions in 2003 in the wake of a contested 2002 presidential election result. The far-reaching impact of the MDC-T's mass action route, especially the ‘final push', were echoed by a one-time fierce critic and at some time staunch supporter of ZANU-PF, Jonathan Moyo, who noted that:

Even though it failed in the end, the MDC's 2003 “Final Push” campaign sent shockwaves within Zanu PF by demonstrating the readiness and willingness of huge numbers of Zimbabweans to take to the streets or stay at home and bring public life to a crushing standstill to get Zanu PF out of power (Moyo, 2009).

As a result, OM was viewed in other circles as entailing a pre-emption strategy designed to thwart widespread uprisings due to the expanding food insecurity and other economic sufferings (Musoni, 2010: 308).

It is noteworthy that there is growing literature regarding ZANU-PF attempts to outwit the MDC in urban areas (Ranger, 2007; Kamete, 2008, 2009; Musemwa, 2010; Musekiwa, 2012; Muchadenyika, 2015a). The strategies ZANU-PF employs which have been covered in the literature, among others include: provision of land for housing (Muchadenyika, 2015a; McGregor and Chatiza, 2019, 2020; Matamanda et al., 2020), control of water supply (Musemwa, 2010) and the role of the Minister of Local Government, amendments to the Urban Councils Act (Chapter 29: 15), and ZANU-PF party organizations (Kamete, 2003, 2008; Ranger, 2007; Chirisa and Jonga, 2009; Jonga, 2012; Kriger, 2012; Musekiwa, 2012; Mapuva, 2013; McGregor, 2013). Most of these strategies have continued to be used and their purpose of undermining the working of MDC-dominated councils are still apparent with far-reaching negative effects on urban governance and human security. Nevertheless, this article focuses on ISV in which it appears ZANU-PF's failure to gain control of urban areas through elections was the primary reason for the government-sanctioned OM. As displayed in Figure 2, ZANU-PF won just a single seat while the MDC-T got 17 seats in Harare during the 2005 parliamentary elections. Following victory in the 2005 elections mainly as a result of the rural vote, then president Robert Mugabe commended the rural voters for acting as the most reliable revolutionaries and pivotal pillar of backing for ZANU-PF (Kamete, 2006: 255). More so, before the 2005 parliamentary election ZANU-PF had, as one of its strategies, attempted to preserve control of urban centers by retaining or recapturing control of vital local government administrative and governance bodies including local councils through the different strategies mentioned above. To this end, Jonga (2012) has justifiably described some of these ZANU-PF strategies as political banditry intended to manipulate the status quo of local government and salvage a losing political party.

Considering that OM was launched in an intricate and problematical socio-economic and political milieu largely characterized by a severe anti-urban residents rhetoric after 2000, the government-claimed goals of the operation while somehow correct are mostly difficult to take as entirely accurate. These include the technical and practical motives and that the government activities were legal as they were implementing anti-informality laws in order to bring urban order through getting rid of the results of untidy urbanization including illegal settlements, overcrowding, squalor and poor service delivery (Government of Zimbabwe, 2005: 16). Similarly, Potts (2006: 273) noted that while the government claimed that the radical eradication of “illegal” housing and informal jobs was necessary, “such justifications obscure far deeper economic and political causes.”

It is true that OM had an array of goals. Among others, Makumbe (2011: 27–28) summarized the goals of OM as entailing: diffusing a politically explosive status quo that was evolving and mainly insubordinate to state machinery; reclaiming the political space that the MDC-T had occupied since 2000; attempting to reverse the devastating breakdown of law and order that ZANU-PF itself had encouraged and supported since 2000; getting rid of political, social and economic bodies and structures that were working independent of both the state and the ruling political party; creating an environment favorable to foreign direct investment in a fruitless effort to lure foreign currency back into the economy; a useless attempt at abolishing the parallel market, anticipating that the foreign exchange transacted there would then be accessible to the state through formal financial institutions; inflicting pain on urbanites that are mostly regarded as enthusiasts of opposition political parties; dragging a substantial number of people back to the rural areas where they are more susceptible to ZANU-PF political control; reducing the prominence of growing urban poverty that was a direct by-product of the political crisis and the unsuccessful land reform process and; diverting public attention from some of the nastiest problems that the country was facing including but not restricted to: scarcity of food, fuel, and the collapse of social services, particularly health and education.

How OM was conducted entailing a nationwide militarized campaign using violent methods to destroy the shacks, vending stalls and other urban informal activities left a lot to be desired in terms of its claimed goals and human security. It had far-reaching effects on ordinary people. According to Tibaijuka (2005: 32), 92,460 housing structures were demolished, disturbing 133,534 households at more than 52 sites, while 700,000 people lost either their homes, source of livelihood, or both and 18% of the population or about 2.4 million people were affected either directly or indirectly. Additionally, OM generated the new challenge of thousands of internally displaced people. The political goal and human security costs of OM were displayed in that its “violence was wanton, symbolic and punitive, signifying ZANU(PF)'s determination to maintain power and social control in the face of a population who probably did not provide a majority vote for it, with areas who voted for the opposition MDC the worst affected” (Bracking, 2005: 342). There was a coincidence with geographical areas equivalent to socio-economic standing, especially in Harare, because it largely focused on the poorer residential areas which are the high-density, low-income spaces and informal settlements and in places where informal undertakings of the urban poor thrived (Kamete, 2012: 67).

A number of scholars concur that the major goal of OM was largely the desperate need to regain political power by ZANU-PF in urban areas following its poor electoral performance in urban constituencies since 2000 (Bracking, 2005; Bratton and Masunungure, 2007; Hove, 2017b; Ndawana, 2018, 2020). However, recently Dorman (2016) has reminded us that we need a somewhat more complex analysis than to see OM as purely political instrumentalization because it was planned long before the 2005 election by HCC officials. Still, regardless of the fact that OM also negatively affected ZANU-PF non-elite members, this study, informed by OM's background, how it was conducted and its human security consequences on ordinary citizens, maintains Potts' (2007: 266) observation that “undoubtedly the issue of the fear (and loathing) of political pressures from urban dwellers is relevant.”

Several human insecurities were caused by OM. According to Bratton and Masunungure (2007), OM's scope was extensive and succeeded at some goals, failed at others, and had influential inadvertent effects. For instance, its human security costs were extensive in that its main victims were youthful, jobless families whom state security agents perceived as prospective recruits for social discontent. It certainly disturbed the informal economy but it was not successful in completely evicting urban residents to rural areas or eternally ending ISV in Harare and other major urban centers. For Ndawana (2018: 256–257), a quick recovery in the figures of street vendors was mainly due to the failure to address the conditions that initiated the informal economy, especially joblessness. The clampdown also methodically disgraced the police and other state security organizations and state repression invigorated its victims, extending polarization among political parties and stimulating the ranks of Zimbabwe's resistance campaign (Bratton and Masunungure, 2007). How OM was implemented not only showed that a state's inflexible use of sovereign and rudimentary and openly violent disciplinary methods in its handling of marginalized urban residents is counterproductive and ineffectual but generates widespread human insecurity (Kamete, 2012: 66). This suggests that the basis for the effective handling of ISV with a human security face in Harare partly lies in, though thorny, the creation of formal employment because it was its lack that primarily initiated and sustained the informal economy.

It is clear that the ZANU-PF government vacillates between allowing and totally outlawing ISV activities. This is because OM came against a backdrop of government initiated policies of indigenization and empowerment that had seen the explosion of the informal sector in the late 1990s and early 2000s. However, this growth became a disappointment largely for purposes of political support when the urban constituencies were continuously won by the MDC-T. Thus, it was disapproved by both the central and local governments together with private formal businesses (Gumbo and Geyer, 2011: 55). For Harare, the government in 2001 had intervened stopping the HCC from carrying out its plans that were already under way demolishing tuckshops. As Potts incisively noted,

The ambiguities and conflicts in official attitudes to the strategies necessitated by urban poverty at this time are evident: the ruling party, faced with an increasingly impoverished city electorate which had recently routed it and replaced it with the much hated opposition party, and an urban local government body which was theoretically on its side, sided with the former against the latter. It is horribly ironic that the justifications given by the central government for its opposition to the demolitions and its criticisms of the Commission in 2001 were precisely those used in 2005 to condemn the government for OM (Potts, 2007: 273).

From this perspective, human insecurity is at the center of the Zimbabwean government's reactions to informality including ISV. This is because the responses fluctuate between actions of frontal belligerence and of releasing bouts of involuntary evictions to exploitative tolerance wherein formalization, steeped in the voluntarist school of thought's solutions to informality, is progressively encouraged as a means of extracting revenue flows from at present economically struggling informal entrepreneurs (Rogerson, 2016: 229). Similar to Jeremy Wallace's (2014) observations in China, ZANU-PF efforts to control ISV and on the other hand, allowing it to flourish are intended to prolong its survival and nothing else. It represents a hybrid regime's response to the threats posed by cities when unemployment and human insecurity are rife.

Unending Ambivalence of ZANU-PF and MDC-T Positions on ISV and Human (In) Security After 2013

The urban informal sector, particularly ISV, again featured as both an asset and liability for the government and the MDC because of the huge numbers of people involved in it after the end of the government of national unity in 2013. As illustrated in Figure 2, during the 2013 elections, ZANU-PF won 6 seats compared to the MDC-T's 23 seats in Harare. This was an improvement from ZANU-PF's winning a single seat in 2008 in Harare compared to the MDC-T's 28 seats (Zimbabwe Election Support Network, 2013: 68). The developments after 2013 further confirmed the view that the ZANU-PF government's stance on ISV is largely determined by the political climate in which when there seems to be no political threats it is viewed as an asset and when there are threats it turns to be a liability. The Zimbabwean government and HCC justified the need to remove street vendors following the intermittent outbreaks of cholera and typhoid in Harare since 2015. In January 2017, challenges of typhoid were at the center of the debate to evict street vendors because the authorities argued that ISV activities were mainly contributing to the outbreak and spread of the disease. About 22 cases of typhoid were established in Harare and 250 cases of the disease were examined (Ndebele, 2017).

Although the HCC blamed the outbreak of typhoid on the rampant ISV activities in the city, the street vendors also blamed the HCC for causing it through the failure to regularly collect rubbish from both the CBD and residential suburbs. The HCC was also blamed for the typhoid outbreak due to its failure to constantly deliver sufficient clean water and sanitary facilities worsened by the paucity of attendance to numerous burst sewage pipes around the capital city (Zuze, 2017). This means that ISV activities were merely aggravating factors because the prevailing conditions in the city were a ready seedbed for the outbreak of diseases such as typhoid and cholera thus a serious threat to human security. Despite the fact that the real cause of the outbreak of typhoid in Harare is a hotly contested issue, it is undeniable that ISV activities somehow represented a liability to the government in which it sought to evict the street vendors. Still, given the fact that the country suffers from a huge unemployment rate, the criminalization of ISV in Harare by both the government and HCC can also be viewed as more of a class clash than anything else. Unemployment has produced human insecurity for different classes of people with divergent views about how it can be addressed.

Regardless of the outbreak of typhoid, one school of thought saw the need to forcibly remove vendors as driven by ZANU-PF's fear of Arab Spring style revolutions echoing the same government concerns in 2005 of the fear of the mobilization of urbanites for popular uprisings. This view asserts that, among other concerns, the ZANU-PF government managed to get into power on the basis of promises to create jobs and even temporarily allowing people to continue selling their wares in the streets but began turning against them for fear of Arab Spring style revolts (Daily News Staff Writers, 2015). Given that the controversial and infamous Arab Spring uprisings which came as a surprise to many were triggered by the self-immolation of a Tunisian street vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi in December 2010, there was some truth from those analysts who saw the need to evict the vendors as meant to nip in the bud a similar Tunisian style uprising (Goodwin, 2011: 453). This is because the Zimbabwean socio-political and economic milieu is replete with deep-seated grievances including rife unemployment and anything can trigger a far-reaching conflict which may bring an end to ZANU-PF rule.

Further, representing a liability to the ZANU-PF government and an asset for the MDC-T and other opposition political parties, there was a wave of protests that rocked the country in 2016. The protests encompassed political and economic demonstrations and the government responded by arresting, harassing and threatening those who complained about the then president Mugabe and the government comprising civil society activists, students, independent media, political rivals, and outspoken street vendors (Congressional Research Service, 2016: 11). The response by the government had serious human security costs. The ZANU-PF government viewed every demonstration signaling disagreement with some policy issues or other grievances as “oppositional forces.” This is regardless of the fact that some informal traders and vendors were aligned to the ruling party such as the Grassroots Empowerment Flea Market and Vending Association Trust which operated at Copa Cabana (Matenga and Nyavaya, 2015). Given the need to survive by ZANU-PF, the government reaction was not unfounded because the ruling party was apportioned all the blame for the continued economic state of affairs in the country and some of the organizers of the anti-government protests were well-known anti-government political and social activists such as Stendrick Zvorwadza (Financial Gazette Staff Reporter, 2016). Clearly, the urban areas' susceptibility to collective action as a result of many challenges including rife unemployment after 2013 in which the informal sector appeared a liability for ZANU-PF and an asset for the opposition also compelled the ZANU-PF government to mull the forcible removal of the street vendors as it did in 2005.

On the other hand, ISV represented an asset for both the MDC-T and some key ZANU-PF members. This was evident in the calls by the then first lady, Grace Mugabe and by extension, the ZANU-PF faction she led (these ceased to be part of ZANU-PF in November 2017) where a human security narrative informed her condemnation of the police efforts to drive away vendors from the CBD to designated sites. They both shared the argument that the street vendors were not supposed to be disrupted as long as they were trying to earn a living (Matenga, 2015a). More so, two distinct camps, that is, pro-MDC-T and ZANU-PF camps emerged in 2015 when the HCC tried to discuss how to proceed with the government directive to remove street vendors from the CBD with all not agreeing on how to handle the matter. The groups belonging to ZANU-PF used Grace Mugabe's statements and vowed that they were not going to leave the streets while some of their colleagues were arguing otherwise that people were misquoting her and should move to designated areas (Matenga, 2015b). The large number of the MDC-T councilors comprising the HCC were supporting the position of the vendors to continue doing their business (Newsday Opinion, 2015). Though the official position was that the vendors were supposed to leave the undesignated areas going to designated areas, it was marred by a number of challenges ranging from inadequate legal vending malls to the lack of customers in the new areas (Matenga and Nyavaya, 2015).

More so, the Grace Mugabe human security-informed viewpoint, albeit contrary to the central government and HCC policy, was also echoed by the National Vendors' Union of Zimbabwe, led by Stendrick Zvorwadza, who previously contested primary elections in the MDC-T, emphasizing the fact that the street vendors should continue doing their business to sustain their lives (Herald Reporters, 2015). Again, before he passed on, Morgan Tsvangirai had effortlessly found political fodder in ISV and quickly expressed solidarity with the vendors. He argued that the government was to blame and should not remove the vendors when it had not created the promised jobs (Daily News Staff Writers, 2015). The ZANU-PF government was blamed for the vending challenge by both labor unions and opposition parties, including the MDC-T, on the basis that it did not deliver the promised 2, 2 million jobs since 2013 (Matenga, 2015a).

A combination of some ZANU-PF and MDC-T officials' support for street vendors and problems at the designated vending sites culminated in the street vendors coming back to the CBD where business was better. Undoubtedly, the large numbers of street vendors was seen as a powerful constituency that was likely to hold sway in the forthcoming elections in 2018. Both the Mugabe and Emmerson Mnangagwa administrations were keen to attract vendors through electoral populism that made ZANU-PF appear pro-poor while the MDC-T was heartless, anti-people and elitist (Hove et al., 2020). The street vendors not only raised human security-informed arguments that the ruling party simply wanted to be vindictive to them when there were no jobs the party promised in 2013 but vowed that they were also going to revenge in the impending 2018 elections (Matenga and Nyavaya, 2015). Therefore, plans to evict the street vendors, especially from the CBD were not implemented until after the elections. This raises an important concern about urban governance in that the involvement of political parties has partly rendered futile some attempts to control the ISV activities in Harare. Critically, the need to evict the street vendors from the streets of Harare was futile largely because of the lack of formal jobs which has been key to the beginning and sustaining of ISV.

The Mnangagwa Administration, COVID-19 Pandemic and ISV

By the end of 2021, there were no changes regarding how the central government and HCC deal with ISV during the post-Mugabe era. Akin to the Mugabe era, the criminalization of ISV has continued condemning many urban residents to abject poverty and human insecurity. For example, immediately after the 2018 elections, in which ZANU-PF continued its loss of the majority of urban constituencies, including in Harare where it won only a single seat compared to the MDC Alliance's 28 seats as shown in Figure 2, but won the presidential elections, some vending sites in the CBD such as those near Harare Central Police Station, at Copa Cabana and Simon Muzenda (Fourth Street) bus terminuses were cleared (Herald Reporters, 2018; Muchenjekwa, 2018).

In addition, in 2020 and 2021 vendors continued to be harassed, have their stalls and trading sites destroyed by both the Harare municipal police and the Zimbabwe Republic Police amid the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic (Ntali, 2020; Chibamu, 2021; Makombe, 2021: 290–294). Among the reasons for destroying vending stalls during this period included that the vendors were attracting many people disregarding the observation of COVID-19 guidelines and protocols such as social distancing thus spreading the disease (Bill Watch, 2020; Toriro, 2020). The payment of bribes to those enforcing the COVID-19 restrictive measures and council by-laws became the sole avenue for one to continue plying their trade everyday (Zimbabwe Peace Project, 2021: 2). Therefore, the politicization of ISV has undermined both urban governance and human security in Harare.

The political instrumentalization of ISV activities by political actors can also be viewed as enhancing lawlessness and disorder which heightens human insecurity conditions. Conversely, by encouraging ISV political players also promote human security by producing an opportunity for economic gain in a context of debilitating poverty and massive unemployment. Thus, encouraging ISV becomes a key strategy by political elites to minimize citizens' grievances against the different levels of government because it ensures that human security is enhanced by making jobs and other public goods and services available for the citizenry. This dovetails with Jeremy Jones (2010: 286) work on the kukiya-kiya practices in the informal economy in Zimbabwe entailing “cleverness, dodging, and the exploitation of whatever resources are at hand, all with an eye to self-sustenance.” It is the dire need for survival that compels people to devise tactical, sometimes unethical and cunning ways to make ends meet. As Jones (2010: 298) observes, kukiya-kiya economy became the modus operandi for everyone from the individual level to the institutional level in post-2000 Zimbabwe. It “entailed a strange convergence with economic logics characteristic of the country's centers of power….necessary for business survival, necessary to defend the country's sovereignty” (Jones, 2010: 298). In this context, it is possible that ISV can be simply a proxy for unemployment and economic problems which promotes human security.

Alternatives to the Criminalization of ISV In Harare

As part of solutions, I suggest a voluntarist school of thought-inspired intervention. The Zimbabwean government and HCC should stop continuing to seek to employ more punitive measures such as a clampdown on the ISV activities but rather build a conducive environment for players in the informal sector as a precursor to formalize their business undertakings. This is because informality may be signifying a starting point for developing entrepreneurs that have the potential to create formal employment which can in turn promote human security. There is no doubt that this formalization will result in the creation of more tax-payers and thus help increase government revenue.

There is also a need to identify, mobilize and develop the potential of ISV for the advancement of human security. A legalist-inspired perspective would suggest that the obstructions to the formalization of the informal sector such as solely viewing it as presenting unnecessary competition to formal businesses are actually impeding these enterprises from growing and recognizing their potential which include creating formal jobs and related positive effects on human security. Moreover, the miscarriage of potentially competitive micro and small enterprises to develop due to unrelenting threats to outlaw and crackdown on them is also hindering them to develop and effectively compete with bigger formal enterprises with far-reaching implications for the competitiveness of the broader economy and promotion of human security. This means that the onus is on the Zimbabwean state to decide when and how to make and unmake informality, which according to Roy (2011), is characterized by gray zones and constant transgressions between the formal and the informal sphere where there are no fixed or stable boundaries.

Additionally, the continued failure to forcibly remove the street vendors in Harare is testament to the complex factors that have initiated and sustained their presence on the streets. The primary factors include desperation, extensive unemployment and the dire need to survive that characterize the country while the politicization of the urban informal economy becomes a secondary factor. To this end, it will be inadequate to merely call for the respective political players to stop interfering in the running of the city for the furtherance of their selfish agendas. This is because the state has a role to play in helping the urban poor to survive in the face of severe unemployment as currently the case in Zimbabwe. Accordingly, a dualist school of thought-informed perspective suggests that ISV is a safety-net for many poor urban residents in Harare and Zimbabwe in general. The Zimbabwean government and the HCC need to rethink their conventional strategies of seeking to completely outlaw ISV and related human security consequences. In lieu, they should look for ways to both allow and regulate it with a long term goal to formalize some of the activities and creating formal employment important to promote human security. This is because for the good of urban governance and human security, the Zimbabwean state really needs to negotiate with the urban poor. It must shun its current position of seeking to outlaw ISV, the urban poor and unemployed people's only avenue of survival without giving them an alternative. Failure to do so will simply perpetuate and bolster “the injustice of enforcing urban ‘order' when the symptoms of poverty thereby tackled have been forced upon the urban poor, and not chosen by them” (Potts, 2006: 273).

Importantly, efforts targeting integrating the informal economy into the formal economy need to diverge from current ones that have failed mainly because they represent “a sinister stripping away of the lifeblood of informality” mostly ignoring “that which makes informality a livelihood haven for the majority of urbanites” (Kamete, 2018: 167). Put another way, urban informality, especially ISV, is promoting the human security of many in Harare - both those involved in it and those who rely on it for cheaper provisions. Therefore, formalization can partially address the human insecurity problems emanating from government clamp-down and repression of the informal sector given the current poor state of the Zimbabwean economy. This means that formal employment is not the only solution to urban informality. Considering that informality is nothing else but a mode of the production of space (Roy, 2009, 2011), street vending, which is an integral part of African urban societies fulfilling different needs in the local economy (Skinner and Watson, 2020) should be carefully handled to promote human security. For instance, 70% of poor households in 11 cities in Southern Africa rely on street vendors or informal outlets for their food (Skinner and Watson, 2020: 127). Globally, the informal sector employs around 2 billion people (61.2%) [International Labour Organisation, 2018: 13]. It is the employer of 69.6% and 18.3% in developing and developed countries, respectively (International Labour Organisation, 2018: 15). Also noteworthy is that informal employment's share varies across different regions of the world: from employing 85.8% in Africa and 68.2% in Asia and Pacific to employing 40.0% in the Americas, and 25.1% in Europe and Central Asia (International Labour Organisation, 2018: 13–14). Accordingly, ISV in Harare, akin to other regions of the world where the informal sector is the main employer, needs careful handling failure of which no meaningful solution can be in sight without providing alternatives for people to survive.

Conclusion

The article has discussed the link between ISV and politics in Zimbabwe and the related consequences on human security. It adds to the literature discussing the informal economy but had elided focusing on the effects of the politicization of ISV on human security. It exposes how political parties in Zimbabwe have sought to abuse ISV to achieve political gains regardless of the urban governance and human security consequences. Focusing on the positions of ZANU-PF and MDC-T, the article shows that the politicization of ISV has contributed to human insecurity and the lack of effective solutions, but it is far from being the major cause of its emergence and proliferation in the first place. The Zimbabwean broader macro-economic context typified by economic decline, shortage of formal jobs culminating in loss of livelihoods and desperation was central to the initiation and sustaining of ISV in Harare as elsewhere in the country. As a result, the basis for effective solutions to address the ISV development in Zimbabwe and related human security concerns partly lies in the generation of formal employment. Attempts solely targeting outlawing ISV without consideration of generating formal jobs are subject to be futile. This is because dependence on the informal sector by the urban poor is not voluntary, but unquestionably essential for their survival and human security. People in Zimbabwe mainly join ISV in the face of a lack of formal jobs or when the formal jobs available do not pay adequately to meet basic costs of urban living. It is doubtless that formal employment is not the only solution given the fact that street vending is an integral part of African and other developing countries' urban societies serving different needs in the local economy.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^This article uses the term MDC-T for consistency's sake to refer to the MDC before and after its split. While the MDC split twice in 2005 and 2014, the faction led by Morgan Tsvangirai who passed on in February 2018 has remained the major opposition political player and dominated most urban constituencies. It is noteworthy that a number of developments took place since the 2018 elections including Thokozani Khupe's usurpation of the leadership of the MDC-T from Nelson Chamisa who contested the 2018 elections under the MDC-Alliance banner and Douglas Mwonzora's takeover of both the MDC-T and MDC-Alliance leadership which compelled Chamisa to rename his party the Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC) in January 2022.

References

Alao, A. (2012). Mugabe and the Politics of Security in Zimbabwe. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press.

Alkire, S. (2003). A Conceptual Framework for Human Security. Centre for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity, CRISE Working Paper 2. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08cf740f0b652dd001694/2p.pdf

Bill Watch (2020). Demolitions: Who is Responsible?. Available online at: http://kubatana.net/2020/04/22/demolitions-who-is-responsible-bill-watch-18-2020/

Bracking, S. (2005). Development denied: autocratic militarism in post-election Zimbabwe. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 32, 341–357. doi: 10.1080/03056240500329361

Bratton, M., and Masunungure, E. (2007). Popular reactions to state repression: operation murambatsvina in Zimbabwe. Afr. Aff. 106, 21–45. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adl024

Brett, E. A. (2005). From corporatism to liberalisation in Zimbabwe: economic policy regimes and political crisis, 1980-97. J. Int. Polit. Sc. Rev. 26, 91–106. doi: 10.1177/0192512105047898

Brown, A. (2011). Cities for the urban poor in Zimbabwe: urban space as a resource for sustainable development. Dev. Pract. 11, 319–331. doi: 10.1080/09614520120056432

Carmody, P. (1998). Neoclassical practice and the collapse of industry in Zimbabwe: the case of textiles, clothing and footwear. J. Econ. Geogr. 74, 4318–4343. doi: 10.2307/144328

Chen, M., and Carre, F. (2020). “Introduction,” in The Informal Economy Revisited: Examining the Past, Envisioning the Future, ed M. Chen and F. Carre (New York, NY: Routledge), 1–27.

Chibamu, A. (2021, June 19). Latest: police, harare city demolish traders' stalls in mbare. NewZimbabwe.com. Available online at: https://www.newzimbabwe.com/latest-police-harare-city-demolish-traders-stalls-in-mbare/

Chirisa, I., and Jonga, W. (2009). Urban local governance in the crucible: empirical overtones of central government meddling in local urban councils affairs in Zimbabwe. Theor. Empirical Res. Urban Manage. 3, 166–182.

Congressional Research Service (2016). Zimbabwe: Current Issues and U.S. Policy. Available online at: https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20160915_R44633_b6fcb025c2c9fd9654e912b7e39ebb84a5544d6c.pdf

Crossa, V. (2020). “Street vending and the state: challenging theory, challenging research,” in The Informal Economy Revisited: Examining the Past, Envisioning the Future, eds M. Chen and F. Carre (New York, NY: Routledge), 167–172.

Daily News Staff Writer (2016, November 15). 20,000 vendors occupy harare CBD. Daily News. Available online at: https://www.dailynews.co.zw/articles/2016/11/15/20-000-vendors-occupy-harare-cbd

Dawson, M., and Kelsall, T. (2012). Anti-developmental patrimonialism in Zimbabwe. J. Contemp. African Stud. 30, 49–66. doi: 10.1080/02589001.2012.643010

de Jager, N., and Musuva, C. (2016). The influx of Zimbabweans into South Africa: a crisis of governance that spills over. Afr. Rev. 8, 15–30. doi: 10.1080/09744053.2015.1089013

Dhemba, J. (1999). Informal sector development: A strategy for alleviating urban poverty in Zimbabwe. J. Soc. Dev. Afr. 14, 5–19.

Dorman, S. R. (2016). 'We have not made anybody homeless': regulation and control of urban life in Zimbabwe. Citizensh. Stud. 20, 84–98. doi: 10.1080/13621025.2015.1054791

Financial Gazette Staff Reporter (2016, 23 June). ZANU-PF targets James Mushore. The Financial Gazette.

Goodwin, J. (2011). Why we were surprised (Again) by the Arab Spring. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 17, 452–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1662-6370.2011.02045.x

Government of Zimbabwe (2005). Response by Government of Zimbabwe to the Report by the UN Special Envoy on Operation Murambatsvina/ Restore Order. Harare: Government Printer.

Gumbo, T., and Geyer, M. (2011). 'Picking up the pieces': reconstructing the informal economic sector in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Town Regional Plann. 59, 53–64.

Herald Reporters (2018, 13 August). Council's destruction of makeshift stalls angers vendors. The Herald.

Hove, M. (2017a). Endangered human security in cash strapped Zimbabwe, 2007-2008. Afr. Stud. Q. 17, 45–70.

Hove, M. (2017b). The Necessity of Security Sector Reform in Zimbabwe. Politikon South Afr. J. Polit. Stud. 44, 425–445. doi: 10.1080/02589346.2017.1290926