94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Cities, 22 March 2022

Sec. Social Inclusion in Cities

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2022.835797

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Hyper-Polarized City: New Insights from Racial EconomyView all 4 articles

In the Summer of 2020, as the latest coronavirus quickened its evolutionary journeys through the human mobilities of planetary urban systems, the research journal of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development published an article by the world's most famous urban economist. Edward Glaeser's article, “The Closing of America's Urban Frontier,” celebrates the influential interpretation of U.S. history offered by Frederick Jackson Turner in a lecture delivered in Chicago in 1893, as part of Glaeser's advocacy of neoliberal, supply-side deregulated city-building as social policy. Yet Glaeser carefully evades the fundamental ethnoracial inequalities at the heart of Turner's frontier thesis, which were inseparable from the Social Darwinist hijacking of evolutionary thought that corrupted economics and other social sciences beginning in the late 19th century. In this paper, the Glaeser-Turner genealogy is used to interpret today's evolving materialities and discourses of race, class, identity, and urbanism. A mixed-methods blend of quantitative modeling and simple, descriptive online media analysis in the spirit of Robert Park's “Natural History of the Newspaper” is used to map the contours of competition, succession, and representation in a planetary urbanism that is now diagnosed as a new phase of “cognitive-cultural” capitalism. Cognitive-capitalist urbanism evolves along multiple semiotic frontiers of cosmopolitan diversity and multidimensional, intersectional hybridity – while valorizing performative competitive hierarchies that legitimate the reproduction of the structured inequalities of capital accumulation. Combinatoric expansion of the spatio-temporal reference points of identity and ancestry present daunting challenges to all who pursue equity or equality – requiring careful strategic confrontation of the meanings of neoliberal planetary human evolution.

In the years of Donald J. Trump's America – our long national and transnational nightmare that is not really over – it became routine to situate the daily scandals produced by the “metropolitan talk machine” of Washington, D.C. (Thrift, 2004) in the lineage of Richard Nixon (in stories about political corruption) or Hitler and the Nazis (in accounts of racism and xenophobia). Trump's campaign for the Presidency reflected and reproduced a cybernetic acceleration of violent cultural and political memes. White nationalists and anti-Semites hijacked the strange cartoon figure of Pepe the Frog and bizarre punctuation (indicating Jewish names with triple parentheses) to build racist solidarities while maintaining digitized plausible deniability. Trumpians used lines from The Matrix trilogy to “red pill” chat-room revelations of conspiracies involving an ever-changing cast of Democrats, globalists, Zionists, George Soros, the Pope, Hilary Clinton, and/or (I am not making this up) Illuminati genetically descended from shape-shifting, blood-drinking, pedophiliac extraterrestrial lizards (for the early historical roots of these viral conspiracies, see Ronson, 2001; pp. 138–169). Struggling to make sense of the chaotic rage, journalists and pundits quickly mainstreamed a previous generation's obscure internet phrase, “Godwin's Law”: “As an online discussion continues, the probability of a reference or comparison to Hitler or Nazis approaches 1.” In the Fall of 2016, Mike Godwin, who had been a computer hobbyist and law-school student when he devised the one-liner in 1990, found his Facebook timeline and Twitter feed flooded with correspondence about Trump's attacks on Mexicans, Muslims, ethnoracial minorities, and every other “other.” In the aftermath of the election, Godwin (2016) issued an update to his quarter-century-old adage: “If you're thoughtful about it and show some real awareness of history,” he wrote in the Washington Post, “go ahead and refer to Hitler or Nazis when you talk about Trump. Or any other politician.”

A few years hence, however, there is compelling evidence that the historical-geographical reference point of Germany in the 1930s and 1940s is generally right but precisely wrong. We can learn far more about the evolution of contemporary ethnoracial relations in the era of planetary urbanization if we explore a dialogue between today's variegated circuitry of communicative capital – the equivalent of 1.45 times the entire global population that is the combined user base of the TikTok, WeChat, Instagram, WhatsApp, Facebook, and YouTube tentacles of corporate empires with a collective market cap of some $7.65 trillion – and ideologies of the late 19th century. Hijacked distortions of the scientific, economic, and philosophical revolutions wrought by Darwin's Origin of Species have been embedded into the consciousness of a humanity that has now finally become – at the planetary scale – a fully diversifying urban species. Planetary consciousness is an illusion, however, a self-reproducing false consciousness belied by the fact that individual, embodied humans are incapable of living and thinking at the global scale. But a warning that was wise two decades ago – Spivak's (2003), p. 72 remark that “the globe is on our computers... no one lives there” – underestimates the performative power of today's globalizing surveillance capitalism, with billions of smartphones reproducing multitudes of algorithmic hallucinations. “At the very moment when we are called to connect with the earth and be stewards of our planet,” writes the Lacanian psychoanalyst and technology critic Turkle (2021), p. 347, “we are intensifying our connection to objects that really do not care if humanity dies.”

The purpose of this paper is to analyze trends in racial formation and governance (Omi and Winant, 1994) in a current era that has been diagnosed as “cognitive-cultural capitalism” (Moulier Boutang's, 2011; Scott, 2011a,b, 2017). The core argument is directed to self-identified progressives and radicals: materialist antiracist strategy is betrayed by the discursive performativity and false radicalism of cybernetic intersectionality. “Woke capitalism” seems new, but in crucial ways it is a cybernetic reincarnation of the most horrific material and ideological assumptions of 19th-century Euro-American Social Darwinism. A simple blend of quasi-positivist and narrative methods are used to examine how the long-sought revolutionary goal of “replacing ... a certain ‘species”’ of humanity “by another ‘species”’ (Fanon, 1961; p. 35) is proceeding – but in confusing, contradictory, and often regressive directions. The primary geographic focus is the U.S. and Canada, examining continuity and change in Smith (1996) diagnosis of the “new urban frontier” of U.S. urban politics as well as the enduring Canadian “fringe” between colonial and transnational past, present, and future (Smith, 2003; Coulthard, 2014).

In the Summer of 2020, as global COVID-19 cases topped ten million and Covid-related deaths surpassed 600 thousand, the second issue in Volume 22 of the journal Cityscape was published online while print copies were dispatched by post. A policy-oriented but rigorously refereed scholarly “Journal of Policy Development and Research,” Cityscape is published by the PD&R division of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). HUD is a microcosm of contradictions in America's racial economy. Its authorization in 1965 was only possible because a rural Southern segregationist president understood how to maneuver the enabling legislation past other rural, Southern segregationist Democrats in the Senate. Ever since, HUD has been the target of every Republican dog-whistle racist attack, from Nixon's silent majority Southern Strategy to Reagan's welfare queens to Trump's inaugural “American Carnage.” Yet by the end of the twentieth century, HUD had been reconstructed through the neoliberal economics that separated race from class, reframing the structured inequalities of inner cities as new market opportunities (Reed, 2020; pp. 77–131). Cityscape, created in the second Clinton Administration, reflected a long-overdue focus on cities, as traditionally anti-urban disciplines finally recognized what major corporations and investors were seeing: the significance of the world approaching the majority-urban threshold (Glaeser, 2011; West, 2017). It was not entirely surprising, then, that Cityscape's second decade featured a lead article by the world's most famous urban economist – the “celebrity urbanologist” Edward Glaeser (Peck, 2016) – offering a panoramic analysis of how public policy was strangling the market dynamism that had created prosperity and opportunity across America's metropolitan system of cities and suburbs. The real surprise was the unapologetic pride Glaeser displayed in drawing inspiration from one of the most horrific products of America's eighteenth- and nineteenth-century racial state: Frederick Jackson Turner's (1893) legendary frontier thesis.

The “fluidity of America's economic geography has radically changed over the last 50 years,” Glaeser (2020, p. 19) argues in a detailed synthesis of economic history and policy analysis. “For most of the period between 1870 to 1970,” Glaeser suggests, “the urban frontier was a great escape valve from local poverty.” Rapid city-building across the midwest, the Great Plains, and the West (and suburbanization across all regions) had facilitated high levels of geographical mobility. Spatial mobility sustained social mobility: moving to new homes and new cities “helped people find better jobs and helped regions transform themselves” through innovation and productivity. Glaeser (2020, p. 19) laments that since 1970, “successful urban areas have made building increasingly difficult,” and with the combination of municipal regulatory bureaucracy and homeowner NIMBYism, “the urban frontier has begun to close.” The process of creating new urban environments, Glaeser contends, was the quintessential comparative advantage in the way America created and renewed its dynamic economy and society. Regulatory interference in the creation of new urban environments is thwarting economic and societal development and progress.

Distilled to this abstract form, Glaeser's account seems to resemble Lefebvre's (1970) theorization of the twentieth century as an historical transition from industrialism to urbanism. But Glaeser's conceptualization of planetary urbanization involves a very different genealogy, reflecting the distinctive American influences involved in the institutional success of his discipline. The consolidation of power and prestige of mainstream economics in various forms – neoclassical, Keynesian, Hayekian-neoliberal, and even today's behavioral turn – is inseparable from the science, politics, and ideologies of Darwinian evolution (see Mirowski and Nik-Khah, 2017). The epicenter of this disciplinary history developed in the early twentieth century alongside the Chicago School of Sociology – a hegemony once satirized as “Urbanism, Incorporated” (Martindale, 1958; p. 28) – and a Chicago School of Geography besotted with an environmental determinism correlating human development with variations in climate, landscape, and agricultural productivity (Block, 1980). Glaeser's view of a city-building century that began in 1870, therefore, is a deepfake Daguerreotype of industrialization, intense competition, and the societal dynamism of mass immigration of settlers from diverse European cultures who created new homes and new identities in a new land of growth and opportunity. This is why Glaeser's story about the creation of cities as the great escape valve from local poverty begins with happy nostalgic scenes from the pre-eminent nineteenth-century celebration of a world created by European colonial capitalism: the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

“In 1893,” Glaeser (2020, p. 5) begins, “Frederick Jackson Turner presented his essay on ‘The Significance of the Frontier in American History’ to the American Historical Association in Chicago.” Glaeser notes that Turner spoke in the World Congress Auxiliary Building of the city's “great Columbian Exposition,” and emphasizes Turner's narrative of the role of colonization of free land in American development. But “the free land that mattered most was not ranchland in the Dakotas,” Glaeser (2020, p. 5) avers, but “land on the edge of Chicago or Los Angeles or New York City.” For Glaeser (2020, p. 6), the “open urban frontier” is “the space to build up and out within already developed urban areas” as well as the shifting spatialities of metropolitan restructuring after World War II, as millions of African Americans fled the Jim Crow South for northern urban industrial jobs while other domestic migrants moved to “new car-oriented cities” built in “Sun Belt states like Arizona and Texas.” Glaeser's goal is to urbanize the historical paradigm that became so influential among American historians of the twentieth century, and so he exploits a misgiving that Turner had expressed in a private letter to Arthur Schlesinger in 1925: “There seems likely to be an urban reinterpretation of our history” (cited in Schlesinger, 1940; p. 43). Glaeser (2020, p. 8) observes that despite “the dramatic urban growth that was happening right before Turner's eyes, the word ‘city’ appears only four times in his famous essay.” True enough. But Glaeser carefully avoids counting any of the keywords Turner actually does use to explain why the frontier is so significant: this was where immigrant-fueled European settler colonialism became American social and political modernity through the “recurrence of the process of evolution” in the dispossession of multiple, resistant, sovereign Indigenous cultures, territories, and traditions (Turner, 1893; p. 200). Obviously, it did not occur to Turner to attempt even a modicum of linguistic respect like today's discourses of NDN sovereignty and Indigeneity: he called the frontier “the meeting point between savagery and civilization” (Turner, 1893, p. 200). Glaeser does not use any such offensive terminology, but the loud message is clear enough from the silences. Glaeser includes not a single mention of Native Americans, Indigenous peoples, evolution, or Darwin – despite the fact that such concepts were the entire basis of Turner's history. Institutions and “constitutional forms” are shaped by “vital forces” that create the “organs” of political life “and shape them to meet changing conditions,” Turner (1893, p. 199) explained. And then:

“The peculiarity of American institutions is the fact that they have been compelled to adapt themselves to the changes of an expanding people – to the changes involved in crossing a continent, in winning a wilderness, and in developing at each area of this progress out of the primitive economic conditions of the frontier into the complexity of city life.” (Turner, 1893, p. 199).

A great deal had been written about the frontier “from the point of view of border warfare and the chase,” Turner (1893, p. 200) clarified, but no one had ever been able to tell a coherent story of why and how America had developed an economy and political institutions so different from those in Europe (see also Fields and Fields, 2014; p. 11). This is what Turner provided, framing U.S. history in the Social Darwinism that was revolutionizing inquiry across all of the social and physical sciences (Hofstadter, 1944). The frontier is a line of “rapid and effective Americanization,” Turner (1893, p. 201) wrote, where the repeated “return to primitive conditions on a continually advancing” zone drives adaptation, innovation, and a dynamic form of social development that begins over and over again. “This perennial rebirth,” Turner (1893, p. 200) told his audience, “this fluidity of American life, this expansion westward with its new opportunities, its continuous touch with the simplicity of primitive society, furnish the forces dominating American character.” Turner's achievement, and his influence over a century of historical and political theory, was to explain how the violence and innovation of the frontier encounters between distinct societies – colonists from multiple warring countries in Europe, the Indigenous peoples he called “savages” – had created an entirely new, unique race: the American.

Glaeser dates the end of an expanding American urban frontier to 1970. Perhaps not coincidentally, this is the nadir of the U.S. foreign-born population share. It has increased ever since to finally return to the transnational melting-pot levels of Turner's day. We are now half a century into a turbulent era marked by the demise of Keynesian welfare-state Fordist industrialism anchored in the U.S. and Western Europe, the ascendance of Friedman-Hayek neoliberal ideologies of market-centric governance from Chile to the U.K. and the P.R.C. and beyond, recurrent bubbles and crises of speculative financialization, and successive rounds of deindustrialization, automation, and adaptive, flexible, and increasingly algorithmic cybernetic networks of economic production, service provision, and everyday social life. Among the many attempts to theorize these post-Fordist transformations, the most valuable is Scott's (2011a,b, 2017) refinement of Moulier Boutang's (2011) account of “cognitive capitalism.” A new frontier of capitalist growth and uneven development is constituted by,

“(1) the new forces of production that reside in digital technologies of computing and communication; (2) the new divisions of labor that are appearing in the detailed organization of production and in related processes of social re-stratification, and (3) the intensifying role of mental and affective human assets (alternatively, cognition and culture) in the commodity production system at large.” (Scott, 2011b; p. 846).

Scott analyzes the economic, political, and spatial transformations associated with cognitive-cultural capital accumulation, while offering a “first-cut geography” (Scott, 2011a, p. 294) of this new wave based on MasterCard WorldWide's ranking of global centers of commerce. These centers stand in for the leading edges of finance, corporate control, consumption, and elite residential and tourist destinations. The peak of the MasterCard hierarchy replicates Sassen's (2002) familiar global city top tier of London, New York, and Tokyo, but down the list are numerous ascendant centers across East and Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America. “The logic of urban change today,” Scott (2011a, p. 316) writes, “is intertwined with the evolutionary development of a globalizing cognitive-cultural capitalism in the context of a dominantly neoliberal policy mileu” that is simultaneously varied, contextual, adaptive, and planetary.

At the heart of cognitive-cultural capitalism's relations with America's racial state, however, is a striking paradox of scale in a world of hybridity, postcolonialism, diaspora, and transnationalism (Omi and Winant, 1994; Appiah and Gates, 1995; West, 1999). The embodied, lived experiences of real, material urbanism are shifting decisively toward multiple centers of the Global South and East. But the key nodes of design, product development and financing, and control for the computational infrastructures of communicative, cognitive-cultural capital accumulation remain, for the most part, anchored in the Global North. Particularly powerful are the tightly-linked axes of media, financial, and political power on the East Coast megalopolis from Boston to New York and Washington, D.C., and the West Coast cinematic and digital corridor from Los Angeles to San Francisco and Seattle; in turn, each of these axes involve significant cross-border interdependencies with Toronto and Ottawa in the East, and Vancouver, BC in the West.

From the vantage point of these important but selective nodes of the North American urban system, the view of planetary urbanism is severely distorted: the entire urban system of Canada and the U.S. combined (only 300 million) is less than two-thirds of the 471 million people in urban India, and barely a third of the 843 million urbanites of China. When ethnoracial dimensions are considered, Anglo, White North America comprises little more than a tenth of urban East and South Asia. Proportions fall further when adjusted for age, family formation, and childbirth. Look down the ranking of the world's largest cities – Tokyo, Delhi, Shanghai, São Paulo, Mexico City, Dhaka, Cairo, Beijing ... and the traditional “West” of the Global North capitalist “core” only appears at rank 28 (Paris) and 35 (London) with New York City holding on at rank 44. In a vast rapidly-growing planetary urban system, North America is a tiny sliver of human evolution at the “edge of the world” (Dyson, 1997; p. ix).

In contemporary planetary urbanism, therefore, the “West” is just one of many frontiers of competitive encounters in the ongoing production of hierarchical human difference. In new luxury master-planned communities in Johur Bahru on islands between Singapore and Malaysia, dominant P.R.C. development firms ensure that security is provided by a specialized private force of ethnic Chinese officers to reassure anxious Chinese buyers who are fearful of the close proximity of Malay Muslims (Mahrotri and Choon, 2016). In Modi's India, the BJP's “mythoscientific” theology of Hindu “bionationalism” inspires a Citizenship Amendment Act that stigmatizes a Muslim community equivalent to the entire population of Nigeria (Subramaniam, 2019; Prashad, 2020). Shop owners from Nigeria are targeted in deadly riots in Johannesburg, where the African Center for Migration and Society warns that xenophobic violence has been “a longstanding feature in post-Apartheid South Africa”; “How is it possible that a black person can be a foreigner in South Africa?” one woman asks a reporter (Turkewitz, 2019). In Hong Kong, anxieties over the P.R.C.'s long-term incorporation strategies were manifest in a portrayal of Mainlanders as “uncivilized” “locusts” invading the once-semi-autonomous region; in 2012 Jimmy Lai Chee-ying's Apple Daily published a full-page, crowdsourced ad of a giant locust looming over Hong Kong – a meme targeting Mainland mothers who come to Hong Kong to give birth so that their “anchor babies” gain access to Hong Kong facilities and benefits (Hayoun, 2014). While Jimmy Lai now serves prison time for protesting the imposition of a new national security law that Beijing portrays as a bulwark against Western influence, the dualisms of colonial and postcolonial, past and present, space and time, are being reconfigured once again. One route to the “core” of the U.S. racial formations of the early-twentieth-century Detroit industrial urbanism that Scott (2011a,b) now sees in its twilight runs through the Ecuadorial Amazon of the twenty-first century. Here, there are only a few hundred Zápara people who survived the “rubber genocide” of Henry Ford's mass-production supply-chain as they were enslaved by Indigenous Quichua, who had been earlier evangelized by Spanish missionaries. To adapt to the slash-and-burn environment produced by the voracious demand for the tires that helped advance the centrifugal frontiers of Glaeser's U.S. Sunbelt suburbanization, the Zápara survivors now hunt spider monkeys. “When we're down to eating our ancestors,” one elder asks, “what is left?” (Weisman, 2006; p. 3).

Nevertheless, the most distorted views can have the most profound consequences. Even the comparatively small quantitative magnitude of an historic U.S.-Canada core that is now on the periphery of world urbanization merits careful scrutiny. Indeed, it is precisely in the way small numbers at the advancing sharp edges of a periphery – the very definition of a frontier – where we see evolutionary dynamics in their purest form. That's why Frederick Jackson Turner did not pay attention to the large numbers of people living in or moving to cities in the United States in the 1890s: he was focused on those few people on the advancing edges of the Census Bureau's maps of the “frontier” defined by lines delimiting areas with population densities of two persons per square mile. Even there Turner was not concerned with most of those persons. He mostly cared about those new kinds of persons created by what he called the process of “Americanization,” as they engaged in what Turner portrayed as “winning a wilderness.” At any moment in time, comparative quantification of human populations is a snapshot on an advancing temporal frontier that privileges the present. This is one facet of what Lefebvre (1970) calls the “blind field” of urbanism, and its deceptions reveal the true significance of an historian's 1893 lecture celebrated by an influential economist in 2020 during the first global pandemic of the age of planetary urbanization. Quantifying the present conceals previous generations of war, politics, theology, and ideology of who counts as human, the meanings of human nature, and where humans come from. The evolution of today's urban planet reanimates Turner's vision – and not just because of Glaeser's celebration of a free-market century of city-building. The essence of Turner's understanding of how new political cultures are produced is now an inescapably planetary process, in a blend of fast-changing biomaterial scientific advances and cognitive-capitalist circuits of discourse, representation, politics, and entertainment. The scientific biomaterialism advances on neo-Darwinian frontiers such as CRISPR gene editing and DNA phenotyping that is adapting William Bratton's vision of “police Darwinism” (Jefferson, 2020; p. 115) to the comprehensive surveillance camera infrastructures and coercive blood sample collections in Xinjiang (Wee and Mozur, 2019). Meanwhile, cognitive-cultural politics and social movements maneuver on multidimensional frontiers that recombine core/periphery, North/South, West/East, colonial/decolonial in shifting reconfigurations best understood as a planetary cybernetic form of neo-Lamarckianism.

Multiple, overlapping, and shifting zones of evolutionary encounters of diaspora and difference create complex, combinatoric configurations of unexpected intersectionalities of identity, politics, and competition. The toxic melting-pot blending of a millennium of European ethno-histories into the American Whiteness of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries encompassed a tiny share of global humanity at the time, and is now an even smaller, rapidly-shrinking fraction of world urbanism. Even within the narrow context of North America itself, a “seismic shift” of demography, culture, and politics has been underway for decades. As Camarillo's (2016, p. 140) notes, the white population of the 100 largest cities in the U.S. fell below a majority as early as 2001, exposing “the new frontier in ethnic and race relations in American cities and suburbs of color.” The varied yet ubiquitous manifestations of diversification – from large, fast-growing, multi-cultural, multi-lingual immigrant-gateway megalopoli to declining, deindustrialized small towns hollowed out by decades of outsourcing – makes residual whiteness increasingly defensive, desperate, angry, and sometimes violent. This is of course a prime lesson from the rise of Trump, where as early as the beginning of the primaries in 2016 Republican candidates were courting an enraged base who preferred white people, hated Obama, Muslims, and Syran refugees, and feared the possibility that the U.S. might some day elect a Latino President (Table 1). Yet in retrospect it is clear that the all-consuming media overload of the Trump years has had the unfortunate effect of prolonging the illusion of stable, inherited binaries of white/non-white relations of identity, class, culture, and power. That's the past. The present and the future are intersectional – even as intersectionality itself has evolved rapidly since Crenshaw's (1991) formulation of the powerful concept. The binary hegemony of U.S. electoral politics conceals a great deal of complexity in identities, alliances, and affinities – apparent in multiple, distinct axes of progressivism vs. conservatism and left- and right-wing versions of populist, anti-elitist anger (Table 2). For decades both parties have developed intricate infrastructures to analyze and harvest intercorrelated identities, but there are especially vivid revelations from the post-postracialism shocks of the 2016 election. Christopher Wylie, the self-described “gay Canadian vegan who created Steve Bannon's psychological warfare mindfuck tool,” struggled to explain the nuances of eigenvalues (of the sort appearing in Table 2) to British parliamentarians investigating the Cambridge Analytica scandal. Wylie's memoir also reveals that the architects of Trump's campaign – Bannon, and the dark-money funders Robert and Rebekah Mercer – fully understood the possibilities of poststructuralist epistemologies like Judith Butler's theories of gender performativity. Rebekah Mercer loved Wylie: “We need more of your kind of people,” she told Wylie (2019, p. 83). “The gays – who I love, by the way.” Bannon's crew exploited right-wing insights on the role of the politics of gender and sexuality – and other multiple dimensions of intersectional identities – as the leading edge of cultural change. Strategy and tactics followed the maxim that “politics is downstream from culture.” If the “core” of Trumpism seemed to embody a stereotypical native-born ethnonationalism of twentieth-century white cisheteropatriarchy, though, its highly visible marketing on the margins – the sociocultural frontier of competition in Electoral College swing districts and low-information voters – encompasses the bizarre diversity of Nikki Haley, Dinesh D'Souza, Diamond and Silk, Milo Yiannopoulos, Caitlyn Jenner, and even the crowds cheering for Ted Cruz, Donald Trump, and Narendra at the “Howdy Modi!” rally in Houston, Texas in September, 2019.

Counterintuitive intersectional racial geographies continue to evolve in the ongoing practice of “racecraft” (Fields and Fields, 2014). In May of 2021, reporters with the Washington Post profiled Brandon Rapolla, a 46-year-old Marine veteran and Second-Amendment hardliner who played a role in no fewer than four armed standoffs with the federal government, including the infamous Bundy Ranch encounter of 2014. Rapolla explains that his brown skin confused an Asian airline ticket agent when his name popped up on the domestic terrorist watch list. It's no mistake, he told the agent, “That's what I'm labeled as.” Rapolla's ancestry traces to China and Guam on his father's side, and on the mother's side a blend of Scandinavian, Inuit, Mexican, and Greek (Allam and Nakhlawi, 2021). Viewed through an antiracist lens with the proper historical focal length, both the medium and the message of the page views, shares, tweets and re-tweets of the Wapo profile of today's “multiracial far right” map the descendants of Park's (1925, p. 80) deployment of biology to make sense of the “natural history of the press” as the “surviving species” of human communications best adapted to the “conditions of modern life.”

Two aspects of continuity and change are significant in today's renaissance of Turner's frontier logics in the reproduction of hyper-polarized urbanism in cognitive-cultural capitalism. The first involves comparative stability in the material infrastructures of capital flows that reproduce long-term urban inequalities of class and race. The second involves the paradoxical blend of continuity and change in intersectional elite diversification and evolutionary hierarchies of cognitive-cultural capital.

One of the core mechanisms of the reproduction of class and racial inequalities in American urbanism is the stratification of mortgage-financed access to the benefits of private property ownership. Every decade since the journalist Brian Boyer's (1973) exposé of predatory FHA lending schemes has brought new market innovations that change the details in the social allocation of credit, risk, debt, and investment – while replicating durable intergenerational divides. At the beginning of this century, a decade of aggressive marketing of abusive, high-cost “subprime” credit integrated local house price bubbles into worldwide networks of investment in mortgage-backed securities, culminating in the global financial crisis of 2008–2009. The inflation of the credit bubble exacerbated class and racial inequalities among those drawn into abusive financial arrangements, while the collapse magnified inequalities in defaults, foreclosures, and the destruction of accumulated home equity and family wealth. Mortgage markets that had become complex arenas of product segmentation quickly reverted to old-fashioned, denial-based stratification of access. In the housing finance literature this is typically modeled as

where represents a vector of financial measures for i individual applicants, represents institutional characteristics of regulatory and industry segmentation among banks and other lenders offering various products, and incorporates housing characteristics of the property serving as collateral for the loan. After accounting for all of these purportedly “non-racial” characteristics, then, the βR coefficients measure the persistent disparities of treatment of applicants of different racial identities that cannot be dismissed by the banking industry's well-financed apologists of economic rationality. This modeling approach indicates that, after controlling for all observable applicant financial characteristics, non-Hispanic African American applicants were 1.80 times more likely to be denied credit compared with non-Hispanic Whites in 2004; this ratio fluctuated in the next few years, reaching 2.52 in 2009. All of these disparities vary widely across the U.S. urban system, along with other contextual circumstances for Latinas and Latinos and others marginalized in America's evolving urban racial state (Wyly et al., 2009).

Replicating this standard methodology with the recently-expanded variable definitions pursuant to the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) reveals intricate new details of old, entrenched inequalities (Table 3). Modeling lenders' and underwriters' rejection decisions achieves a very close fit across nearly all of the response curve, with the exception of modest departures in the 75–79 percent probability range (where the model predicts 78 percent of applications rejected, vs. only 65 percent actually turned down) and the 55–59 percent range (57 vs. 52 percent) (Table 4).

From one perspective, these results are just the latest quantification of the racial disparities documented in the vast literatures on redlining and housing market segregation. In these models, the “reference” applicant is the stereotypical suburban “white picket fence” bank customer: a non-Hispanic white man with a very low debt level (<20 percent of income) applying for a conventional, first-lien mortgage to purchase a site-built, single-family home. More than 89 percent of these borrowers are approved. Yet while some dimensions of this once-dominant market segment endure – applicants who chose “white” as the first of five possible responses to identify race account for 64 percent of the 6.85 million applications filed in 2019 – their interdependency highlights diversity and change. The whiteness of American housing capital endures, but the market shrinks when narrowed to non-Hispanic white (54.1 percent) men (36.5) seeking loans on single-family homes (35.5) to be purchased (15.5) with conventional first-lien mortgages (10.9); adding the final criteria of the stereotypical applicant – income and wealth sufficient to borrow at a low debt-to-income ratio – the market vanishes to just 58 thousand borrowers, less than one percent of the nearly seven million customers nationwide that year. Capital can quite quickly and efficiently simplify a diverse market by segmenting applicants just by class: a restrictive debt-to-income ratio alone excludes 93.9 percent of all applicants. The crucial market opportunities are diverse, but in deeply unequal segments that require aggressive selection processes to allocate high-cost credit while carefully rationing mainstream lending through underwriting and denials. Black applicants are 2.3 times more likely to be rejected, even after controlling for debt burdens and all other observable loan and housing characteristics. Applicants identifying as Hispanic or Latino face ceteris paribus rejection odds ratios of 1.6, while disparities are worse for Native Americans (1.9), South Asians (1.7), Filipino/as (1.8), Vietnamese (2.3), and Samoan (2.4) applicants.

Again, it is possible to regard these results as just the latest manifestation of the tangle of American pathologies of the racialized urbanism of the 12th century. But this turns out to be a contentious matter even today. Mortgage credit is one of the domains examined in Reed's (2020) wide-ranging critique of the post-racialism myths running through the Obama years to Coates' (2014) influential article, “The Case for Reparations” (see also Fields and Fields, 2014; Wallace-Wells, 2022). For Reed (2020, p. 1), Obama and Coates “have taken up complementary roles of black emissaries of neoliberalism,” with the former embracing a postracialism that promotes the trope of individual underclass deficiencies of behavior and culture, while Coates treats “racism as the engine of history” that can only be understood in terms of “inexorable white prejudice” and the repeated plunder of Black bodies. Both approaches succumb to a race-reductionism that treats racial disparities “as if they exist in a world apart from the economic processes that generate them,” Reed (2020, p. 102) argues, resulting in a deceptive evasion of the complex history of state and market processes that shaped housing market segregation and Keynesian suburbanization in the 1940s and 1950s. Reed explains how FHA and VA state-backed mortgage insurance (launched in 1934 and 1944, respectively) enabled millions of renters to become homeowners, while excluding African Americans and many other racialized peoples until the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Reed faults Coates for repeatedly separating race from political economy, and for attacking the New Deal as irredeemably racist – thus ignoring how housing policy had become a Keynesian solution yielding macroeconomic growth and enticing benefits that helped defuse the widespread labor militance and unionized class consciousness that had threatened capital in the 1930s and 1940s. Reed's meticulous examination of organizing, coalition-building, and strategic politics in the New Deal makes it clear that state-backed mortgage subsidies were a class project stratified by race, not a race project stratified by class.

This distinction became a cruel paradox when formal institutional discrimination was outlawed in 1968. Federal agencies reversed course on racialized credit markets, away from guarantor of standardized racial exclusion toward anti-discriminatory intervenor to stamp out the worst of bigoted industry practices and state and local codes. This shift was slow, uneven, and often contradictory, but had achieved decisive changes in lending and underwriting by the mid-1990s. By the time the federal government had begun seriously to address racism in access to credit, however, the combined effects of deindustrialization, suburbanization, and the new international division of labor had transformed the role of housing finance. From the 1930s to 1968, federally-subsidized cheap mortgages delivered remarkably consistent access to affordable new homes in growing suburbs, purchased in large part by unionized workers in manufacturing industries – front-office, white-collar employees as well as blue-collar, assembly-line workers – who could look forward to modest but increasing standards of living through steady wage increases, rising home equity, good health care coverage, and generous retirement pensions. All of these arrangements collapsed or were disentangled after 1968 with the demise of Fordist-Keynesian urbanism. Benefits became more inconsistent, stratified, rationed, unreliable, and unequal from the 1970s through the 1990s. At the same time, offshoring, decentralization, and gentrification created severe, structural spatial mismatches in metropolitan labor markets. Such mismatches were especially severe in the interactions between race and gender (McLafferty and Preston, 1992), but the manifold inequalities were universally driven by the national and transnational consolidation of neoliberalism and class competition. “[T]he pathways that white ethnics traveled from tenements to middle-class suburbs,” Reed (2020, p. 172) concludes, “have steadily narrowed over the past half century,” as the aborted yet aspirational universalism begun in the New Deal devolved into an ever more fine-grained quilt of uneven neoliberal market opportunities.

New dangers appeared immediately. The 1968 legislation that reoriented FHA created lucrative opportunities for predatory scammers and blockbusters exploiting Black desperation for ownership and white fears of falling property values – yielding quick profits for realtors and brokers (Wachter, 1980) while saddling Black borrowers with loans destined for default across a vast urban system of inner-city foreclosures. In his book Cities Destroyed for Cash, Brian Boyer (1973) referred to these hundreds of thousands of foreclosures scarring hundreds of neighborhoods across dozens of cities as one giant metropolis, which he named for Nixon's HUD Secretary: “Romney City.” While the FHA scandal was subsequently addressed through regulatory changes in Washington, DC, successive rounds of bipartisan deregulation in banking and finance in the Reagan, Bush I and II, and Clinton years opened vast – but hyper-polarized – new market opportunities. Borrowers got access to new choices and new kinds of loan products, but many of the new options were quite dangerous. Investors in the U.S. and around the world got access to the implicit guarantee of Fannie and Freddie and the intoxicating steady yields from mortgage-backed securities. Lenders, brokers, and realtors got access to volume-based fees while passing off long-term risks to secondary-market investors.

By the time of the dramatic credit bubble of 2001–2007 that culminated in the global financial crisis, half a century of neoliberalization had completely transformed the social function of the traditional, New Deal / Keynesian Fordist home mortgage (Harvey, 1989). That old model had been part of a wider social contract – of strategic concessions by capital to militant labor – and it had also shaped the evolution of America's racial economy. “[T]he New Deal and postwar economic expansion did not simply enable hyphenated East European Americans, hyphenated Mediterranean Americans, and Jews to ascend to the middle class,” Reed (2020, p. 170) writes; “the opportunities the welfare state of yesteryear afforded these and other white ethnics helped transform these once racialized groups into archetypical ‘Americans.”’ But in the new century the old social-contract mortgage had been completely replaced by a neoliberal lottery ticket. Home loans gave less reliable access to the benefits of good homes and good neighborhoods, and the massive “subprime virus” of high-risk loan products put millions of borrowers at risk – along with their neighbors and their local governments (Engel and McCoy, 2011). Mortgages facilitated the frantic pursuit of home equity as a substitute for the shrinking remnants of the New Deal safety net that had been created through militant labor struggles in the 1930s. And it is worth recalling that one of the firms at the center of the 2001–2007 subprime boom was led by a Black man who worked his way up to Wall Street CEO from a house without plumbing in Wedowee, Alabama, whose grandfather had been born into slavery in 1861 (O'Neal, 2008); the firm's top management also included an Egyptian-American Vice Chair, a Korean-American Co-Head of Global Markets, a Turkish-American Head of Fixed Income, an Indian-American Head of Equities, and a Japanese-American Head of Market Risk.

The key point here is that while sharp racial disparities persist in American housing capital, they are reproduced through the self-replicating circuits of class, finance, and debt. It is an absolute injustice that Black loan applicants are, all else equal, more than twice as likely to be denied mortgage loans compared to non-Hispanic whites. But all else is not equal. Black applicants are nearly twice as likely to have high consumer debt loads (21 percent have debt-to-income ratios over 50 percent, compared to only 11 percent of whites) and this is where the most ruthless social stratification in mortgage markets reflects the wider context of precarity for all poor and working-class Americans. Even after controlling for racial disparities, applicants with debt-to-income ratios over 50 percent face rejection odds over 3.0, and over 60 percent the barrier shoots up to nearly 28. When the models are estimated separately by race, the screening effects of debt load are most pronounced for non-Hispanic whites: rejection odds rise to 3.6 for DTIs over 50 percent, and to 32.6 over 60 percent (vs. 1.44 and 11.2, respectively, for non-Hispanic Black applicants). The racialized predatory wave of the late 1990s and 2000s does not appear to have returned: odds ratios from a model predicting subprime loan features remain statistically significant but comparatively low for Blacks (1.10) and Hispanics (1.14). The disproportionate importance and benefits of FHA insurance endure, however: holding all else constant, Black borrowers are 1.99 times more likely to receive an FHA loan, while the ratio is 1.94 for Hispanic/Latina borrowers.

Reed (2020) situates the historical portrayal of housing finance in Coates' (2014) case for reparations in today's wider cultural discourses and political struggles over inequalities in access to good jobs, elite educational opportunities, and equitable representation in political and cultural institutions. After generations of market-focused neoliberalization – from Reagan's “government is the problem” to Bush's “ownership society” and Clinton's “new Democrat” triangulation of “new markets” – public policy and social activism now focus obsessively on the pursuit of equitable access to inherently inequitable resources (debt-leveraged private property ownership, Ivy League admissions, elected office in hierarchical systems of political power). Through the strategic deployment of “the language of structural racism and intersectionality,” Reed (2020, p. 8) argues, neoliberalism has hijacked the anti-racism and equity principles of progressives in order to strengthen the foundations of market society. The result is a wholesale reconfiguration of historical consciousness – suppressing the memories of Bayard Rustin, A. Philip Randolph, and other civil rights leaders from the 1930s and 1940s who understood working-class solidarity as fundamental to achieving racial equality. At the same time, the popular progressive ontology of embodied race divorced of materialist political economies of class – or at least those political economies that were the subject of union labor militance in North America in the 1930s – has reanimated varied strains of purity and essentialism. This is most clear when Coates' (2014) case for reparations is taken to its logical conclusions with the vibrant political movement ADOS – American Descendants Of Slavery – which “wants to establish what it considers a properly ‘cohesive’ notion of Black identity, fencing out people like Barack Obama and Kamala Harris as ‘New Black’ usurpers of a native lineage of suffering” (Appiah, 2020). Other indications are apparent in the way flourishing social movements seeking to build solidarities of BIPOC lived experience and liberations of gender and sexuality – the current acronym inclusion frontier is LGBTQQIP2SAA+ – must dialectically define their goals in opposition to previous “new left” social movements that were seen in the 1960s as transcending an obsolete class reductionism. Witness the hatred of some progressives for the human identities now memed as “Karens” or “Jessicas” or TERFs and SWERFs (Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminists, Sex Worker Exclusionary Radical Feminists). Now that post-Fordist, post-structuralist, automated deindustrialization has developed – at least in many cities of North America – into a comprehensive informational form of cognitive-cultural capitalism, capitalist-rooted class inequalities can be further entrenched while everyone fights online over such things as the bitter feud of Obama's legacy with Cornel West that led Coates to leave Twitter, or the self-referential Godwin's Law ironies of a declaration that the Nazi genocide of European Jews is “not about race” – offered by the Black celebrity Whoopi Goldberg, who identifies as Jewish (Hersh, 2022). In any event, on the fast-changing frontiers of cognitive-capitalist inequality, the real focus of attention is not on those who find it necessary to ask a bank for a mortgage to be able to buy a house. Forbes, which has been diversifying its multiple, popular billionaires' lists for many years now, proudly features Shonda Rhimes – the “Screen Queen” with annual earnings of US$70 million – on the cover of its Summer 2021 “Inclusive Capitalism” special issue. “I never worried that I deserved the money,” declares the brilliant, charismatic, and entrepreneurial Rhimes. “I deserve every penny.”

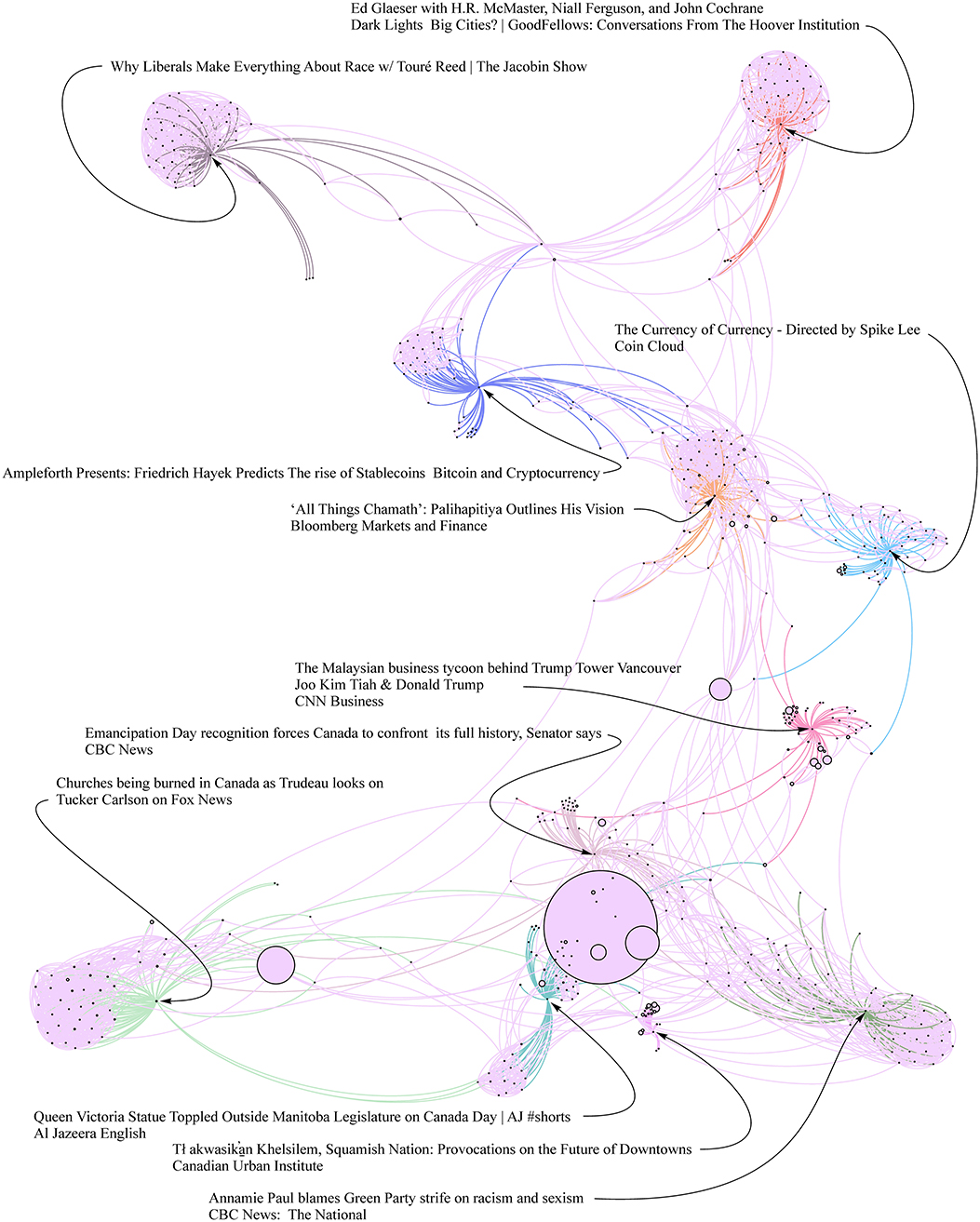

Durable material infrastructures of interlocking race-class inequalities are reproduced through adaptive legitimations of identity in cognitive-capitalist neoliberalization. Recently, publicly-released innovations by Reider et al. (2018) have made it possible to map parts of the infrastructures by which “behavioral futures markets” of human attention and discourse are valorized and capitalized in what Zuboff (2019) diagnoses as “surveillance capitalism.” At least on one of the key portals of cognitive capitalism – YouTube – it is now a simple matter for anyone to create empirically detailed maps of the “seemingly endless and intricate webs of representation” (Harvey, 1992; p. 42) by which “differentiated urban consciousness” (Katznelson, 1988; p. 615) co-evolves with the “factory of fragmentation” of a variegated yet planetary capitalism (Harvey, 1992, p. 44; cf. Harvey, 2018, and Zuboff, 2019). The specifically urban dimensions of online discourses are not the geographic locations of those producing, sharing, or viewing the messages – but rather the fractal communicative hierarchies of language as an evolutionary medium (Zipf, 1949; McLuhan, 1962) that became the organizing principle of urbanism as a spatial-science strain of economics: cities as systems within systems of cities (Berry, 1964). Figure 1 displays connections between online audience formation processes for one of Touré Reed's lectures critiquing neoliberalized racial identity politics, one of the talks by Glaeser in the months after the publication of his “Frontier” article, and a series of other representations of events in the Summer of 2021 highlighting North American discourses of whiteness, race, culture, and capital.

Figure 1. Mapping Evolutionary Online Discourses of Race, Urbanism, Culture, and Capital. “Recommended for You” video correlations suggested by YouTube's algorithms, as extracted from the YouTube application programming interface (API) with the open-source tools developed by Bernhard Reider at the Digital Methods Initiative at the University of Amsterdam (see Reider et al., 2018, and https://tools.digitalmethods.net/netvizz/youtube/mod_videos_net.php). Connecting lines indicate correlated suggestions by YouTube's algorithmic analysis of individual and collective viewer preferences. Bubble sizes scaled proportional to viewcount. Data extracted August 3, 2021. Graphic constructed by the author.

The magnitude of prosumptive cognitive labor in Figure 1 – 525 intercorrelated videos with a total viewcount of more than 826 million – illustrate the scale of the evolving worlds of discourse, culture, identity, and representation. In the U.S. and Canada, race is of course central to these processes. In 2015, Touré Reed's father, Adolph Reed, Jr., juxtaposed the progressive celebrations of Caitlyn Jenner's transgender revelations with the progressive vitriol over Rachel Dolezal's “fraudulent” Black identity. Race politics is now “not an alternative to class politics,” Reed (2015) wrote; “it is a class politics, the politics of the left wing of neoliberalism.” Social and political struggles over diversity and representation in the top tiers of economic, political, and cultural hierarchies now reproduce a moral economy that naturalizes the structured inequalities of a capitalist market order – thus replicating the survival-of-the-fittest ideological political economy of Turner's (1893) day. This is a representational moral economy, Reed (2015) explains, where

“a society in which 1% of the population controlled 90% of the resources could be just, provided that roughly 12% of the 1% were black, 12% were Latino, 50% were women, and whatever the appropriate proportions were LGBT people.”

Each of these dimensions is intersectional, dynamic, and combinatoric, dialectically evolving through alliances and conflicts as Harvey's (1992) factory of fragmentation generates more than US $257.6 billion in revenue for Alphabet alone in 2021 – more than four-fifths of it from renting out optimized reconfigurations of the global attention span (i.e., advertising). The real, material urban landscapes of the past century of struggle documented by Reed (2020) now co-evolve with online hierarchies of representation, identity, and mobilization. There are two distinct ways to interpret the intricate interconnections and hierarchies mapped in Figure 1. First, all the complexity and diversity can easily be distilled by the rank-size rule logics of urban systems (Zipf, 1949; Berry, 1964) that are now encoded into the algorithmic architectures of Silicon Valley (Aiden and Michel, 2013):

where the population P of a city ranked r equals the population of the top-ranked city divided by r raised to the exponent of q; in most cases, empirically, q approximates 1.0. Substituting audience size for city populations allows the complexity of Figure 1 to be summarized as

with R2 = 0.9184. Nine-tenths of the diversity of online discourse is easy to predict if all one cares about is attention and the accumulation of cognitive surplus. This is part of what Zuboff (2019, p. 377) diagnoses as the “radical indifference” of “equivalence without equality” in the computational consciousness of surveillance capitalism.

But what if we do care about the diversity of human lives, discourses, and representations that are constantly competing in these hierarchies? This is the second approach. Let's follow just the main axes of connections among the correlations served up by YouTube's API “up next” viewing recommendations. As we work through these complex and often confusing correlations, it becomes clear that the self-replicating codes (Dyson, 2012) of cognitive capitalism accelerate the production of intersectionality through representational connections that scramble time and space among the living and the dead. Hence it is no surprise that Reed's warnings on the dangers of “race-first neoliberalism” connect via a 1991 interview of Milton Friedman over to Ed Glaeser's talk on the future of cities with H.R. McMaster – who in 1991 was Lieutenant General preparing for the Battle of 73 Easting in Operation Desert Storm, but is now, after serving as Trump's first post-Flynn National Security Advisor, honored as the Fouad and Michelle Ajami Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution. The post is named for the Iranian-Lebanese-American broadcaster who was the first Arab-American ever to win a MacArthur “genius” award, who compared Saddam Hussein to Hitler, cheered the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, and attributed Islamist terrorism to self-delusion and rage over losing world supremacy to Europe after the failed 1693 Turkish seige of Vienna. Edward Said once called Ajami's neocon geopolitics “unmistakably racist.” Go the other way, and Reed and Glaeser's talks connect with Friedman's ally and mentor Friedrich Hayek, whose entire epistemology comes directly from the same nineteenth-century Social Darwinist philosophies that shaped Turner's (1893) frontier thesis – and whose conceptualization of a “market mind” (Hayek, 1982) is now all the rage among the billionaire architects of cloud computing, artificial intelligence, blockchain and cryptocurrencies, and the singularity of human and computational consciousness. The billionaires of the future of capital, moreover, embody the speed of change on the evolutionary frontiers of cosmopolitan capital. The newest entry on the Forbes world billionaires list is Chamath Palihapitiya, who speaks of taking the baton from Warren Buffett to speak for a new generation “in the language they understand.” Palihapitiya tweets to his 1.5 million followers on humanity's future as a “robust multiplanetary species,” cheered the GameStop meme stock rally, and quoted Charles Dickens from 1859 to assure his investors that capital and technology will replace A Tale of Two Cities with a “world with an even starting line for everyone,” regardless of religion, gender, location, or socioeconomic status. When a journalist asked tough questions about investors angered over his implosion of a venture capital fund, Palihapitiya replied,

“I chose to retire. This is my decision. I am not your slave. I just want to be clear. My skin color, two hundred years ago, may have gotten you confused, but I am not your slave.” (quoted in Duhigg, 2021).

Similarly, Spike Lee – who back in 2015 memorably defined gentrification as “motherfuckin' Christopher Columbus syndrome” – now praises the “digital rebellion” of CoinCloud, a company that operates 3,000 cryptocurrency ATMs in 47 U.S. States and Brazil. Old money is white, and it “systematically oppresses,” Lee declares in his self-directed commercial, whereas new money is “positive, inclusive,” diverse, “fluid, strong, culturally rich,” as the scene cuts to smiling faces of color holding a sign for BLACK TRANS LIVES MATTER. Follow the links through a few late-night comedy clips on anti-Fauci conspiracy theories and satires of Trump, and you get to news accounts of the visionary behind the Trump Tower in Vancouver, B.C., which by key measures has become the world's second most expensive real estate market (Gordon, 2020; Ley, 2020). A quarter century after Mitchell (1993) diagnosed the region as “Multiculturalism, or, The United Colors of Capitalism,” the capitalization of global ethnoracial evolution is featured in recurrent spectacles like Joo Kim Tiah, the eldest son of Malaysia's wealthiest developer, happily shaking hands with The Donald at the groundbreaking in Vancouver, then a few years later tweeting out a selfie from Trump's Inaugural. Yet there were profound ironies in what Tiah told a journalist about their partnership. Tiah and Trump shared the experience of growing up alienated from harsh, powerful, distant fathers who demanded success; but while “I want to achieve and make money,” Tiah explained, “there has to be a bigger purpose. What drives me in my heart, my calling, my purpose, is God” (quoted in Ryan, 2013; p. C2). Tiah is just one of many devout Christians among the ascendant transnational entrepreneurs of British Columbia's West/East growth machine (Ley and Tse, 2013), accentuating the distinctive intergenerational contradictions of capital accumulation in Canada's colonial present (Bowman, 1931; Smith, 2003; Coulthard, 2014; Joseph, 2018). Canada remained a formal colonial “Dominion” until a constitutional patriation in 1982, and for a full century beginning in Turner's day, Canada pursued a forced assimilation policy in partnership with Christian churches that coercively removed more than 150,000 Indigenous children from their families. Church-run residential schools have been formally recognized as a form of cultural genocide (Truth Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015), and in the Spring and Summer of 2021 fresh revelations emerged when ground-penetrating radar located hundreds of unmarked graves of children at school sites in B.C. and Saskatchewan. Protests spread across Canada on National Indigenous Peoples Day, and then on Canada Day protesters toppled and beheaded a statue of Queen Victoria at the Manitoba Legislature in Winnipeg. In the days before RoseAnne Archibald clinched the fifth round of votes to become the first woman ever to serve as National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations to represent 634 of Canada's Indigenous nations, several churches in the western province were set ablaze. After Vice World News tweeted the latest update, the Vancouver-based attorney and author Harsha Walia re-tweeted the story, adding, “Burn it all down (Bramham, 2021).” It was Godwin's Law all over again, with a social media firestorm amplified by a Fox News segment with Tucker Carlson calling Walia a “monster,” intense debates over whether it was anti-Jewish to describe the residential schools as “little Auschwitzes,” journalists chasing after Indigenous leaders to ask whether they supported the burning of churches, and a flurry of academic blog posts explaining that “burn it all down” does not mean “burn it all down” but is instead part of a centuries-long “lexicon of social justice.” Walia was forced out of her position as Executive Director of the BC Civil Liberties Association, followed by a wave of recriminations amongst rival BCCLA board factions over allegations of targeted racism and misogyny. The Minister of the Chinese Mission to the U.N. in Geneva took the opportunity to call the unmarked graves “only the tip of the iceberg” of “genocide in Canada,” while among the churches set ablaze was an African Evangelical Church serving refugees, a parish building housing Vietnamese and Filipino congregations, and a Coptic Orthodox church. A congregation member whose family immigrated to Canada three decades ago and helped build the sanctuary of St. George Coptic Orthodox Church in Surrey, B.C. cried when she learned the news. “It hurts to see no words from the government,” she lamented to a journalist as officials worked through the discursive dichotomy of Indigeneity vs. Christianity. “We are the Copts, which is the Indigenous group of Egypt” (quoted in Ryan, 2021). Meanwhile, there were tweets from an Indigenous anthropologist at UBC who had once been sued for using the phrase “Alt-Right” to describe a new party launched by a Hong-Kong-born devout Christian Conservative parliamentarian representing a district where, she proudly noted, three-quarters of the residents have “ethnic backgrounds from around the world.” This time the “Alt-Right” label was applied to Canada's federal Green Party, and a purportedly “anti-Indigenous” aide to Annamie Paul, the Party's recently-ascended breakthrough leader – the first Black Canadian and first Black Jewish woman to lead a federal party in Canada. Amidst disputes over the strength of condemnation of Israel's air strikes in Gaza, the aide accused progressives and climate activists of “appalling anti-Semitism” and tweeted, “We will work to defeat you and bring in progressive climate champions who are antifa and pro LGBT and pro indigenous sovereignty and Zionists!!!!!” As Al Jazeera covered the preparations for Canada's newly-decreed Emancipation Day holiday with an archive photo of a Toronto sit-in to mark the Juneteenth commemoration of Texas' delayed news of the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, national and transnational capital investment continues valorizing new frontiers in British Columbia. Nearly all of the province is unceded under the strictures of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, and thus as recent court decisions have repeatedly (if belatedly) recognized the non-Cartesian, overlapping land claims of more than 200 First Nations, entirely new spatio-temporal coordinates of moral claims and capital accumulation are remaking the region's settlement fabric and political discourse. Objections to “highest and best use” are routinely attacked as racist, even as corporations and public institutions develop ever more sophisticated narratives of legitimation to reconcile the inclusion of regional, national, and transnational capital flows with the layered histories where – as one Indigenous knowledge-keeper emphasized in a recent ceremony with UBC President Santa Ono – “the lands we stay on are made up of the blood and bones of our people.” Median single-family detached home values for Canadian-born homeowners in the Vancouver metropolitan region are Cdn$1.25 million, while the values are Cdn$1.66 million for recent immigrants, Cdn$2.40 million for immigrants admitted under Canada's cash-for-citizenship investor class, and Cdn$2.80 million for immigrant investors from mainland China who are admitted through Quebec's separate program, but who then went to Vancouver (Gellatly and Morissette, 2019, p. 7). Capital, competition, and culture intensify older-established strains of Eurocentricty and white supremacy (Mitchell, 1993; Blomley, 2003), while also valorizing selective new configurations of identity, origins, and ancestry that tie local parcels of multi-generational layers of investment (Massey, 1978) into lineages stretching across the planet or millennia into the local past. On one side of downtown, a tiny parcel of land is the subject of a lawsuit over a short document signed in Hong Kong by a firm co-founded by a Hong-Kong-born Canadian developer and a billionaire from Singapore, after they began to fight over the details of a Cdn$500 million project. A kilometer away, an old apartment building with an assessed value of Cdn$16.8 million was flipped in a crowdfunded bidding war for a shell company on WeChat for Cdn$60 million, then flipped again for Cdn$68 million to a new firm established by a Shanghai developer's pair of sons – graduates of Vancouver's Sir Winston Churchill Secondary School (Young, 2016). A few blocks away, Vancouver's first tower in the new “Super-Prime” global building classification carves out a new frontier in the charitable ethos of equity, inclusion, and “giving back to get ahead” amongst local developers (Hyde, 2020): each unit sold finances a home made from a shipping container, given to a family living on the edge of a garbage dump in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. The penthouse unit is now being marketed by a Chinese-Canadian entrepreneur starring in a new realty-reality series with the producers of Ultra Rich Asian Girls, as she brandishes a tablet copy of Trump's Art of the Deal. The “one for one real estate gifting model” was developed by a retired Hollywood film executive. The lead developer – a locally-grown firm now with marketing offices in Beijing, Taipei, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Tokyo – is in a joint venture on the other side of False Creek, on a parcel of land that might very well be a reversal of Turner's (1893) frontier, a new fusion of Glaeser's (2020) city-building utopia that achieves a kind of re/possessive collectivism (cf. Roy, 2017) on Camarillo's (2016) new “racial frontier” to transform whiteness as property (Harris, 1993; Appiah, 1997). “The @NYTimes features Vancouver's Seńáḵw Development and the MST Developments in a wonderful view into the growing efforts by Indigenous Peoples to make investments into land & real estate,” tweeted Khelsilem, Spokesperson for the Squamish Nation. In 2003, a court decision returned a tiny triangle of land to the Squamish, who had been dispossessed in 1913 from a broad territory covering what is now the entire City of Vancouver. Now this parcel is the site of the largest Indigenous development project in North America, a Cdn$2.67 billion plan to build a four-million-square-foot complex of a dozen mixed-use towers with 6,000 apartments, in a mixture of rentals and market-rate condos on leasehold land. The development “on land that was illegally confiscated from my ancestors,” Khelsilem explained to the Times reporter, will “create value that is going to benefit our people,” and will position the Squamish to be “long-term leaders in the region” – to use knowledge acquired through Seńáḵw “to develop the expertise and capacity to do projects at this scale elsewhere” (Baker, 2021). In 2016, the Squamish established a consortium with the Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh Nations – MST – and now “the three local First Nations upon whose territory Vancouver sits,” Khelsilem explained in a Zoom talk to the Canadian Urban Institute, “are currently the largest property owners in Vancouver. And I'll reiterate that again: the Indigenous people of Vancouver who are from here and have been here for thousands of years, own more private property than any other developer in the region.” The Indigenous values on culture, environment, and transportation incorporated into Seńáḵw point the way to what “community building and city building means in the twenty-first century.” “Colonization began only a few generations ago on these lands,” notes the project website. Now, after the colonial interregnum that so damaged human relations with nature as well as understandings of human nature, “we can demonstrate how humanity and nature can co-exist.” Non-Indigenous developers, investors, and real-estate analysts are enthralled by the new meanings of “highest and best use” enabled by Seńáḵw and MST, regarding them in the precise free-market terms Glaeser (2020) advocates in his deregulatory urbanization of Turner (1893). The city-building plans of reascendant Indigeneity are beyond the jurisdiction of the restrictive municipal zoning codes and other bureaucratic constraints loathed by champions of neoliberal urban optimization.

The point of all these empirical narratives is to highlight the enduring significance of Turneresque nineteenth-century thought for understanding the implications of Glaeser's (2020) advocacy of free-market city-building – at a moment when the production of intersectional identities is accelerated through the algorithmic fusion of capital and cognition. Today's celebrated breakthroughs of intersectional diversity help to reproduce the evolutionary infrastructures of societal competition, popular legitimacy, and naturalized market inequality that have consituted capital accumulation since the era of Social Darwinist industrial colonialism that infected Turner's thought. The exact same logics that Turner applied to the frontier of rural land then transformed urban studies and economics when Hayek used nineteenth-century psychology to theorize market relations in terms of human cognition. For Hayek, Keynesian economic planning was the Godwin's law “road to serfdom” and a “menace to civilization” because of the limits of both individual and collective human knowledge. The human central nervous system is nothing more than a fluid, stimulus-response process of “continuous and simultaneous classification and constant reclassification” (Hayek, 1982, p. 289; Hayek, 1952). The only reliable source of economic knowledge is The Market – the “spontaneous order” of extended human cooperation in exchange relations that have evolved over the entire history of planetary and human evolution, creating an omnisicient, species-wide form of cognition that is “probably the most complex structure in the universe” (Hayek, 1988; p. 127). This “cognitive Darwinism” can never be acknowledged openly by U.S. neoliberals – given the power of Christian creationists in the political constituencies of the American Right – but it is now encoded into the cognitive-capitalist operating systems of a “planetary Silicon Valley” (Zukin, 2021) that intertwines the material interests of urban growth machines with the semiotic production processes of the technology industries. It is here where Turner's hierarchical Social Darwinism applied to land co-opts the long-term goals of the Left with a cognitive-Darwinist colonization of the shifting “mental terrain” of racecraft (Fields and Fields, 2014, p. 18). To the degree that separating struggles over race from those of class ensures a failure to deal with either (Reed, 2020), such evasions are solidified as cognitive-capitalist factories of fragmentation automate the production of new dimensions of intersectional difference, from ADOS to BIPOC to TERFs and SWERFS and LGBTQQIP2SAA+ and beyond. As every new axis of identity creates opportunities for visibility, amplification, and recognition within newly-created spaces of hierarchical competition, intersectionality is co-opted to reproduce meritocracies that legitimate the endless commodification of discourse, culture, identity, and ancestry. Cognitive capitalism now produces parallel urban systems – systems within systems (Berry, 1964) of material urban embodiment and the disembodied “anticipatory evolution” of neoliberal sociocultural market transformation and algorithmic racecraft (Berry, 1964, 1980; Fields and Fields, 2014). The differentiated urban consciousnesses of postindustrialism are now capitalized through the operation of flexible-specialization memetic assembly lines of the industrialized production of human difference, yielding infinite, combinatoric competition over multi-scalar, transhistorical moral rent gaps (Smith, 1982; Katznelson, 1988; Harvey, 1992, 2000; Coulthard, 2014).

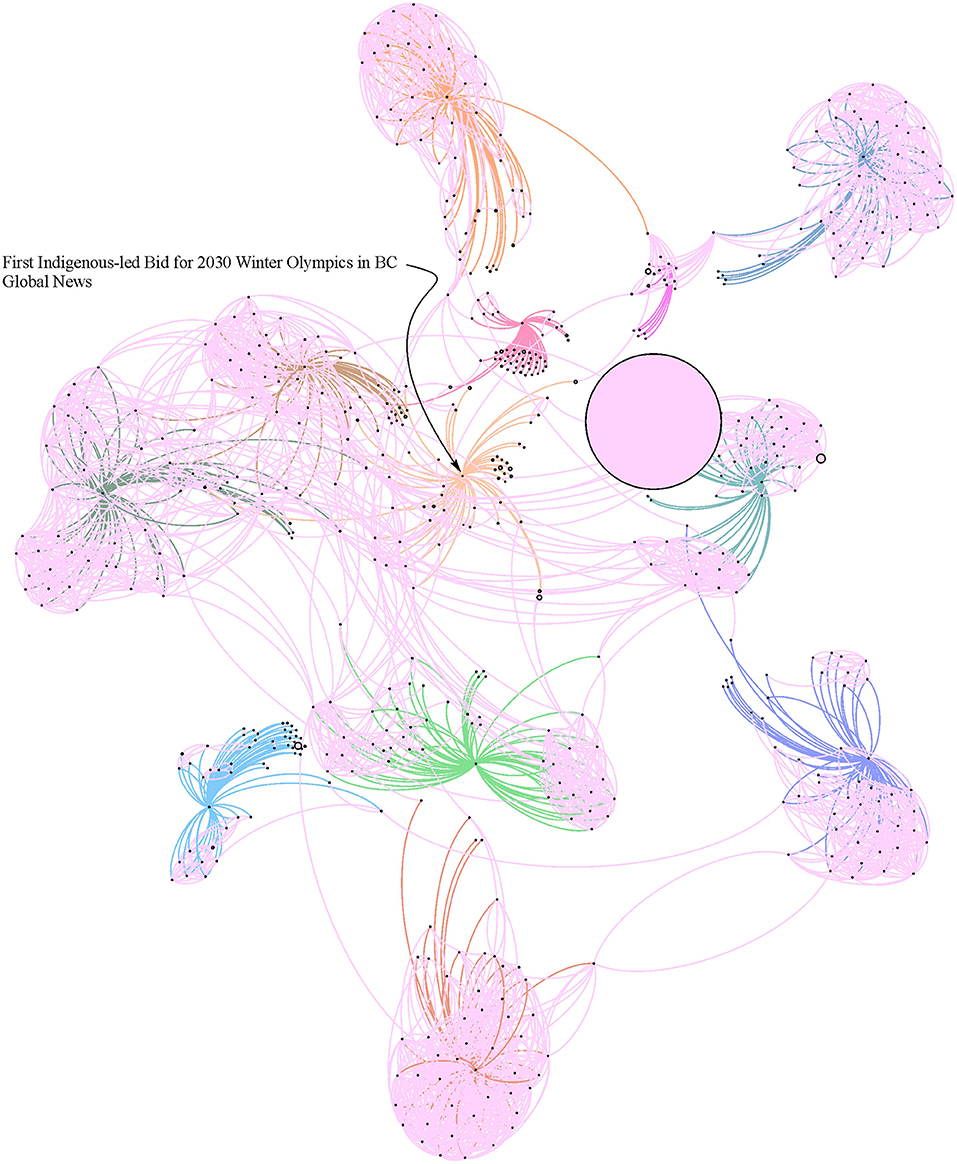

A year after Vancouver's hosting of the 2010 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games and a year before Neil Smith died, Smith spoke alongside the anti-poverty activist Jean Swanson at an anti-gentrification community meeting in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside. Held in a building that is hallowed ground in memories of Canada's dispossession and internment of Japanese-Canadians in 1942, the event highlighted how local discourses and practices of “poor-bashing” (Swanson, 2001) were becoming enmeshed in the “extraordinary ubiquity” of cosmopolitan, transnational forms of gentrification in twenty-first century global urbanization (Smith, 2011). Only a decade later, in early December, 2021, leaders of the Lil'wat, Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations held a press conference to announce a Memorandum of Understanding with the Mayors of Vancouver and Whistler. The announcement was held in BC Place, a giant, multipurpose stadium built in the early 1980s on old cleared railroad lands from the 1880s, only a few meters away from the tiny parcel that is the subject of ongoing court battles between Vancouver and Singapore billionaires disputing the meanings of a piece of paper signed in Hong Kong. The BC Place press conference announced a planned bid to host another Winter Olympics. It will be the first Indigenous-led Olympic bid in world history. “I know our ancestors are looking at us now,” Musqueam Chief Wayne Sparrow told reporters. “We're going to be a big part of an Indigenous-led proposal. It's very, very exciting, and I think this is a big part of reconciliation” (quoted in Fumano, 2021). “Back in 2010, we were just little,” Tsleil-Waututh Nation Chief Jen Thomas added, reflecting on the last time the region hosted the world's largest hallmark event. “Now, everybody knows MST. Everybody knows this is our territory.” The region's adaptive growth machine highlights the advancing frontiers of ethnoracial legitimation, pre-emptively discrediting community opposition of the sort witnessed in 2002 and 2003 – back when Neil Smith got arrested at a housing-rights protest and Jean Swanson worked to mobilize activists in the Downtown Eastside who questioned the use of public funds to subsidize a global spectacle of gentrification and displacement. Now on City Council after repeated, hard-fought underdog campaigns, Swanson is torn. “I spent 3 years of my life fighting the Vancouver Olympics,” Swanson told a reporter. The Games cost US $7.6 billion – triple the initial budget – including a secret, emergency billion-dollar City bailout of private developers' profits on the Olympic Village when a New York hedge fund withdrew bridge financing amidst the Global Financial Crisis. But now, an Indigenous bid is harder to question. “I'm skeptical,” Swanson explained. “But I want to do things that will support the host nations. So it's a huge conflict for me.”

Cognitive capitalism is an evolutionary acceleration of the adaptive legitimations of Turneresque human hierarchies, and so YouTube's API easily assimilates a news item on the first Indigenous-led Olympic bid in world history with Ed Glaeser's chat with H.R. McMaster, Chamath Palihapitiya's ruminations on humanity as a multi-planetary species, Spike Lee's crypto rebellion against the systemic oppression of old white money, church burnings and protests over Indigenous residential schools, and Khelsilem's reminder that the Indigenous peoples of Vancouver who have been here for thousands of years now own more private property than any other developer in the region (compare Figure 1 with Figure 2). Racism and anti-racism dialectically co-evolve in the representation, legitimation, and reproduction of structured material inequalities, and it is a simple matter to quantify the equivalence without equality that Zuboff (2019) identifies in the operation of surveillance capitalism. Figure 1 was just an instantaneous snapshot of fast-changing evolutionary discourses, and when the press conference of the plans for Vancouver's Indigenous Olympics bid is added (Figure 2), the equation for the mental terrain of digitized racecraft of 1.792 billion intercorrelated views adapts smoothly to a new temporary, partial equilibrium of

with R2= 0.9408. If the goal is to reach a genuinely new, new frontier on an urban planet – to truly reconcile human difference with human equality – the first step must be to think strategically, to avoid the dangerous deceptions of neoliberal capitalist cognition. Algorithmic intersectionality is re-positioning the multidimensional spatial and temporal coordinates of intergenerational ethnoracial evolution in planetary urban systems, building a new fusion of objective/materialist and subjective/humanist manifestations of universal alienation, and creating daunting new challenges in distinguishing allies from adversaries.