- Oxford Institute for Sustainable Development, Faculty of Technology, Design and Environment, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, United Kingdom

This desktop study paper suggests a “flows and livelihoods” framework for comparative studies on displaceability in the context of infrastructure and investment/projects in diverse post-colonial settings. It uses the ongoing upgrading of Mbudzi (Goats) interchange, in Harare, to discuss the utility of this framework in addressing diverse sustainability and human security questions irrespective of scale, scope and settings of the project. Thus, the paper contributes to integrated ways of understanding dynamics and sustainability of infrastructure investments. In the process, it also responds to calls on the need for exemplars on how theory can be integrated into planning research. Ultimately, what it offers is a heuristic device for cross-sectional and time-series studies.

Introduction: Infrastructure, the post-colonial and displaceability

Contributing to debates on urbanization in the global south, Randolph and Storper (2022, p. 4) observed that much of the existing research and scholarship is “ethnographic, illuminating the texture of everyday life and the interactions between culture and social relations and institutions that produce particular experiences.” In a word, there is limited theorisation. At the same time, Rydin (2021) has called for more exemplars of how theory can and should be used to guide research in planning studies. With this backdrop in mind and focusing on infrastructure, the overall argument in the paper is that urban development induced displacements in Africa are as significant as the rural displacements and that the consequent human security shortcomings should be considered together with the dominant urban violence, crime, health and safety concerns especially in post-colonial Southern Africa.

The post-colonial moment in Southern Africa is not just about arrival of political independence or majority rule. Political independence coincided with a neoliberal moment where the welfare role of the state has been hallowed out or emasculated. In countries like Zimbabwe, the 1980s development and welfare role of the state underpinned by growth with equity policies (GoZ, 1981)1 was short-circuited by this neoliberal turn. The ideology and rationale of market-based delivery of public services dominates this post-colonial neoliberal moment, with the resultant marginalization of the majority who cannot afford to pay. As a result, increased class differentiation, polarization, inequality and fragmentation (Harrison et al., 2003), spatial and infrastructure violence (Matamanda and Mphambukeli, 2022) are key features of societies in the region. At the top end is a small but growing super rich comprador class whose enrichment is often through plunder of public resources (see GoZ, 2019; Baeta, 2022; GoSA, 2022). At the bottom end are the destitute and increasing numbers of the new poor (Minujin, 1995) who survive as an informal proletariat sustaining (yet at the margins of) the global capitalist system. This informality of livelihoods and economies of the majority translates into spatial informalities such as witnessed at Mbudzi (Harare, Zimbabwe, see next section).

However, informal spaces exist in a state displaceability (Yiftachel, 2020). This is a condition of itinerancy and vulnerable existence susceptible to involuntary displacement: physical, economic, civic and epistemological dispossession (Samson, 2015). While Shannon et al. (2018) claim that key drivers of such displacement are market/investor led redevelopment in the case of Mozambique, elsewhere [e.g. in Nairobi (Manji, 2015), Cape Town (Newton, 2009) and Addis Ababa (Di Nunzio, 2022)] there are significant state led developments often crafted to create an environment conducive to future market led investments. Since about 2000, there has been an upsurge in infrastructure development globally, the so called “infrastructure turn” (Dodson, 2017); with governments in Africa making genuine attempts to upgrade dilapidated infrastructure which in some cases dates back to pre-independence years (over 40 years ago in the case of Zimbabwe). The upgrading of Mbudzi is an example of such state-led projects. As Shannon et al. (2018) indicate, these investments are associated with a narrative of growth and public interest; the focus on issues of displacement is rather muted.

The upsurge in public and private sector led infrastructure projects has witnessed a resurgence in involuntary displacement of occupants and livelihoods on the land required for any development (Shannon et al., 2018; Baeta, 2022). COHRE (2009) reports these as forced evictions while Shannon et al. (2018) characterize them as development induced involuntary displacements and resettlement (DIID). As Rolnik (2019) underscores, such displaceability of informal occupants and livelihoods represents tenure insecurity for the majority in diverse economies. Urban displacements range from public sector led urban renewal and upgrading such as in Addis Ababa (Di Nunzio, 2022), infrastructure investments in Nairobi (Manji, 2015), housing developments in Luanda (DW, 2005) and Accra (Du Plessis, 2005), urban policy in Harare (Auret, 1994; UN-HABITAT, 2005; Kamete, 2007; Potts, 2011; Hammer, 2016), private sector led urban renewal in Maputo (Baeta, 2022) and Beira (Shannon et al., 2018) to mega-sports infrastructure in South African cities such as Cape Town (Newton, 2009; Jordhus-Lier, 2015). Regarding South Africa, hosting the 2010 FIFA World Cup was a particular episode where largely government funded urban sports infrastructure displaced thousands of households and livelihoods (Newton, 2009; Pillay et al., 2009; Maharaj, 2015). In Cape Town alone, twenty thousand (20,000) residents of an informal settlement were displaced to an impoverished area at the periphery of the city (Newton, 2009, p. 105; Maharaj, 2015, p. 990). Displacements extend to those arising from tourism infrastructure, including space enclosures in rural areas and hotels in urban areas (Leonard et al., 2021).

For Southern Africa, the fact that displaceability of majority Africans was also a key feature of settler colonial-apartheid years (Newton, 2009; Isaacman and Isaacman, 2013; Muller, 2013) suggests that there is continuity in democratic deficits and the fundamental forces of unequal power underpinning these societies. It seems office bearers in central and local governments may change, but the enduring fundamentals of capitalist social existence in the region make displaceability inevitable. The socio-economic and spatial reality of marginalization, features of urban settlement and the voicelessness of the majority remain entrenched; the post-colonial is yet to come.

Consequently, displaceability and tenure insecurity that is one the many dimensions of human insecurity examined by the United Nations (UN, 2003; UN-HABITAT, 2007), is endemic in Southern Africa. The majority of citizens are at risk and highly vulnerable to development induced involuntary displacements in both rural and urban areas given the surge in infrastructure projects (UN-HABITAT, 2007, p. 31–34). Nascent acts of resistance and insurgency (Miraftab, 2009; Ray, 2010; Jordhus-Lier, 2015) have not had a lasting effect. Concepts are needed to help frame and examine displaceability questions across the rural-urban divide. Such questions for research are outlined in the third section. The fourth section then sketches the conceptual apparatus/mind maps that could be used for comparative studies along both cross-sectional and temporal lines. Human security and people's lives and livelihoods are at the core of development induced impacts. Hence the comparative framework is anchored on the sustainable livelihoods framework (Rakodi and Lloyd-Jones, 2002; Scoones and Wolmer, 2002)-a standard concept in development studies. This is combined with what Shannon et al. (2018) have proposed as an exploratory “flows and spaces” approach. Without delving into the empirical details, section four also revisits the questions for research using the suggested “flows, spaces, and livelihoods” framework. It does so with reference to an ongoing project, the Mbudzi interchange upgrading project, Harare, described in section three. To reiterate, this is not an empirical based research paper but a desk study based provisional attempt to extend to infrastructure planning, theorisation calls implied in Rydin (2021) and Randolph and Storper (2022). Centered on Zimbabwe as a case in Southern Africa, the next section presents trends in infrastructure to provide the context within which to ask questions on infrastructure delivery and livelihoods security. Following a short description of a reference project (Mbudzi Interchange) in section three, section four presents the “flows, spaces, and livelihoods” framework and its potential utility.

Infrastructure projects: Overview of trends research questions

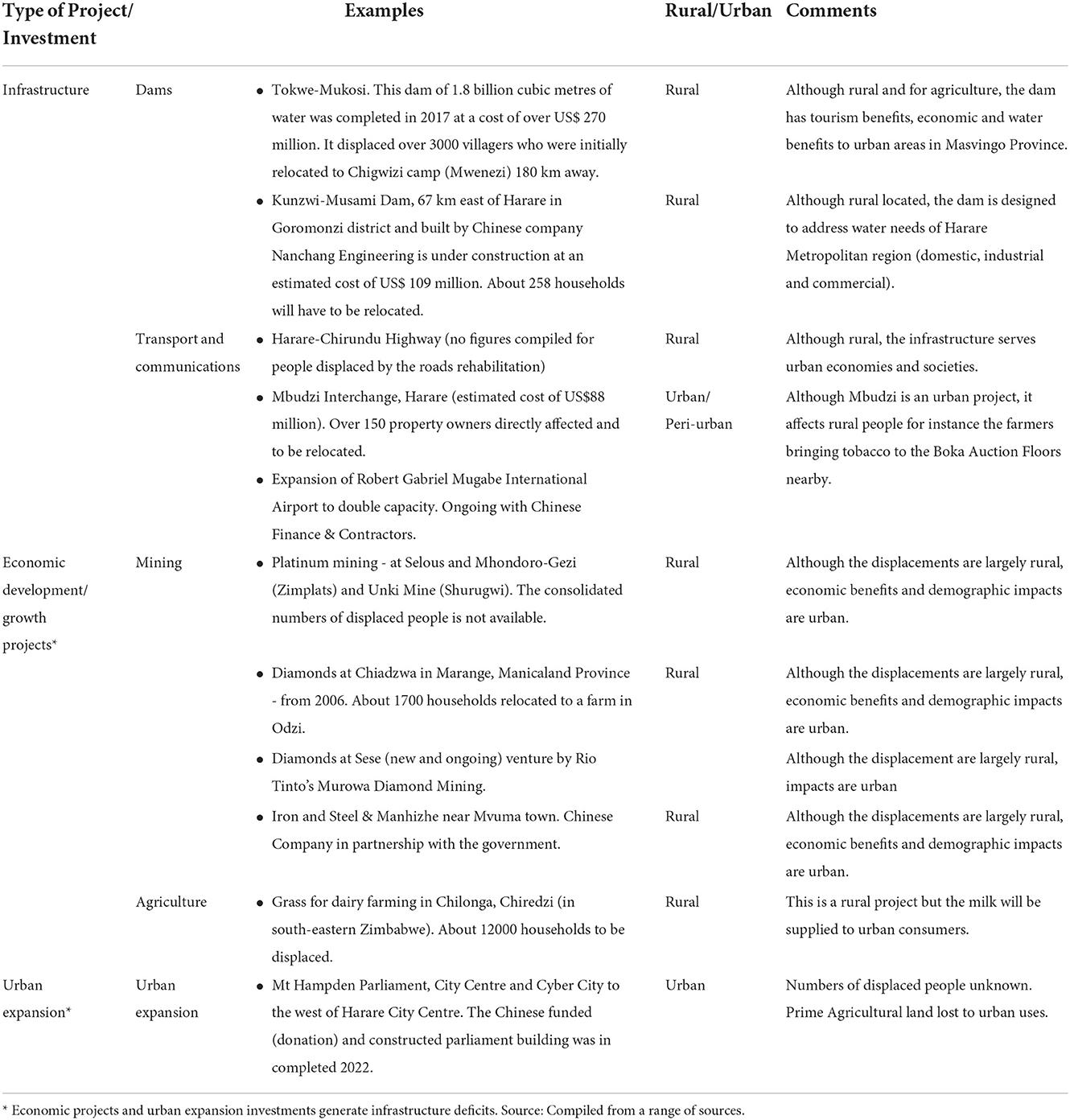

“Infrastructure turn” (Dodson, 2017) is a term often used to capture the post 2000 resurgence in infrastructure investment as a strategic economic and development imperative: a rise in private and public infrastructure driven projects across the globe as countries seek to address an increasing “infrastructure gap/deficit” (Goodfellow, 2020). The drivers and characteristics of this deficit are diverse. They include the need to rehabilitate dilapidated infrastructure, to provide infrastructure to previously excluded communities and lagging regions (Kanai and Schidler, 2022) and to replace obsolete infrastructure to match new technologies and demands for a green economy and knowledge society. Taking Zimbabwe as an example, current large infrastructure projects are related to economic development and rehabilitation of archaic infrastructure in both rural and urban areas with the goal to make Zimbabwe a high middle-income country by 2030. These growth projects range from large dams such as the Tokwe-Mukosi dam and the Kunzwi dam2 to large platinum plants (Selous and Mhondoro), diamond mines (Marange3 and more recently at Sese4) and iron and steel mining (Manhizhe near Mvuma)5 to roads and communications projects (Beit-Bridge border post, Harare-Chirundu Highway) and urban expansion (Mt Hampden City/Cyber City). The topical and current cases in the agriculture sector include the Lucerne grass for dairy production Chilonga6 project in impoverished southeast Zimbabwe. As indicated in Table 1, thousands of people were or are likely to be displaced especially in the dam, mining, tourism and agriculture projects.

Displacements (often very traumatic) associated with the projects as indicated in Table 1 lead to questions of whether the associated displaceability differs between rural and urban infrastructure projects or across sectors (mining, agriculture, energy etc.); what accounts for such differences if any and how learning across spaces can be enhanced for human security. Reflecting on aspects of these questions, Shannon et al. (2018, p. 3) emphasize that:

“…involuntary displacement and resettlement research has focused predominantly on large scale and one-off interventions in the rural realm… and what this development induced displacement and resettlement ultimately mean within the context of urban development and how it relates to issues of urban sustainability, is therefore largely unknown.”

Furthermore, Shannon et al. (2018) argue that urban development induced involuntary displacement and resettlement in Africa has been discussed only in the context of neoliberal urbanism where market forces are a key driver–suggesting that state led projects are minimal.

However, literature on urban housing, planning, land and local resistance in South Africa (see for instance Huchzermeyer, 2003; Miraftab, 2009; Ray, 2010; Muller, 2013; Jordhus-Lier, 2015) in Zimbabwe (see Kamete, 2007; Potts, 2011; Hammer, 2016) and Ethiopia (Di Nunzio, 2022) points to a contrary position. Development induced involuntary displacement and resettlement or development violence (Escobar, 2004) is a recurrent feature in Southern Africa since colonial times and some has occurred outside the context of neoliberal urbanism. In the context of Zimbabwe, recurrent urban demolitions and displacements, [such as Porta Farm (Auret, 1994); Operation Murambatsvina (UN-HABITAT, 2005; Kamete, 2007; Potts, 2011; Hammer, 2016; Mbiba, 2018)] occurring with/without resettlement often exhibit extreme human rights abuses characterized under the rubric of forced evictions (COHRE, 2009; Mbiba, 2022). The point is that large-scale development induced displacements (an integral feature of modernization) do occur in urban areas and the state is an instigator of projects in significant instances. Even if the majority of urban displacements were small scale in scope (relative to the rural), the cumulative impact is equally significant.

Therefore, there is need to take a differentiated approach in order to understand the nuances and diversity of displaceability between and within countries and cities and over time even for one displacement case. Moreover, infrastructure projects like dams that are rural located can at the same time, be explicitly for water supply to urban areas as in the case of Kunzvi Dam-designed to supply water to Harare Metropolitan region (see Table 1). The legendary Kariba dam was built (in 1958) primarily to supply electricity to the Zambian Copperbelt and urban Zimbabwe (then Southern Rhodesia) while Cabora Bassa, built in the early 1970s (about 100 km downstream of Kariba) in Mozambique, had 82% of its electricity earmarked for export, mainly to South Africa (Isaacman and Isaacman, 2013, p. 3). The Lesotho Highlands Project (Katse dam) has a similar contribution to South African cities. Thus, the rural and urban categories are artificial and not always accurate.

These nuances suggest that generalizations may not be helpful; instead, questions should be raised to deepen case understanding using approaches that enable learning over time and across cases. This paper will suggest the framework to use for such endeavors and to address a range of further questions relating to stakeholder dynamics, claims, interests, roles and engagement strategies. Infrastructure projects take place on land and are contested by all stakeholders with claims and rights to the land. Contestation around claims, compensation, and resettlement are central issues. Questions include issues of:

• How stakeholders learn and what knowledge they bring from previous displacements to negotiate new ones;

• What formal and informal livelihoods safeguards are put in place and how sustainable they are in the different cases;

• What roles different stakeholders play and whether and to what extent the stakeholder characteristics and structures determine outcomes;

• What third party oversight institutions are involved and what determines their impact.

• How to incorporate the rural and urban dimensions of each project so as to better understand the current, cumulative, local and dispersed displacement impacts of the project.

As alluded to earlier, there is an abundance of empirical and ethnographic case studies that address most of these questions. However, what Shannon et al. (2018) illustrate is the path toward needed enhanced theorisation for comparative understandings over time and across contexts. The purpose is not to generate law like theories [itself a futile exercise in the social sciences (Randolph and Storper, 2022)] but to supply a heuristic conceptual apparatus that can be a basis for comparative empirical exploration and dialogue. Such a task is attempted in this paper in which the “static” but well known livelihoods framework is combined with the flows models of Shannon et al. (2018) to create a dynamic framework. In the process, reflections will be made in the context of the Mbudzi Interchange (Harare) described below.

Mbudzi interchange: Background and contemporary policy context

Mbudzi/imbuzi (goats) is a name given to a major gateway road junction on the southern part of Harare, the capital city of Zimbabwe. Until the last decade, it was at the edge of the city where the regional highway from Harare to South Africa intersects with the High Glen-Chitungwiza road that is a section of the incomplete circular ring road around Harare (see Supplementary Images 1 and 2). Like most major junctions in and around the city, it was a favorite spot for hitchhikers–in this case traveling to southern Zimbabwe and beyond to South Africa. Hawkers and informal traders were attracted to the junction to provide services to such travelers and long-distance truck drivers. In no time, the site became a bustling economic space and market place where basic goods, building materials and services (such as hair saloons, food kiosks, foreign currency) could be purchased.

In the early years, goat traders found the crossroad and the pastures around it an ideal place to sell goats; goat meat is a delicacy for large sections of the Zimbabwe population. Goat sellers targeted urban residents from Harare and Chitungwiza where keeping goats is prohibited. The distinctive presence of goats (Mbudzi) gave the place its popular name. Industries and developments sprouting in the neighborhood in recent years include the Boka Tobacco Auction Floors (established 1997) about 3 km down the road as well as nearby Granville Cemetery, that is popularly known as “kuMbuzi” (the place of goats)7 commissioned in 1997. A large and vibrant West Properties designed and managed “Mbudzi People's Market” was opened in 2015 as a Public Private Partnership with City of Harare. By the turn of the millennium, the cacophony of informal activities, a rapid increase in car ownership and increased traffic servicing new post 2000 residential areas in Harare South (e.g., Hopley and Southlea) made Mbudzi junction a highly congested space and traffic bottleneck. Dilapidated infrastructure (roads, storm water drainage, refuse removal, street lighting) compounded the dire congestion situation.

The chaos and infrastructure decay at Mbudzi and the rest of the Harare–South Africa highway was symptomatic of the neglect during the Mugabe years. Not surprisingly, after 2017, the Second Republic (New Dispensation) made rehabilitation of Chirundu-Harare –South Africa highway a priority under the National Development Strategy 1. Therefore, unlike in the case of infrastructure reported for Beira in neighboring Mozambique (Shannon et al., 2018) where the local authority is in charge, the state through Ministry of Transport is the custodian of development/upgrading of Mbudzi interchange where engineering works commenced in May 2022 (GoZ, 2022). The local authority, Harare City Council does not own the project but is one of the key consultees and partners. The question is where and how do projects like Mbudzi interchange fit into the bigger trends of infrastructure development in Africa? How should they be understood within and beyond the local context? The next section adopts Shannon et al. (2018) illustrating how when combined with the sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF), provides a new framework for understanding processes and outcomes of infrastructure projects such as Mbudzi Interchange.

“Flows, spaces, and livelihoods framework” for comparative analysis of infrastructure induced displacement and resettlement: Outline and discussion

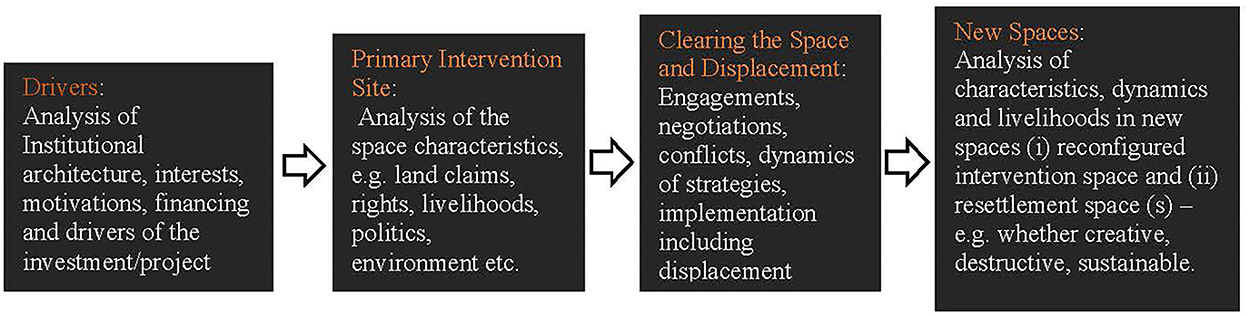

In their review, Shannon et al. (2018) argue that urban areas have unique institutional and socio-political challenges/opportunities that lead to different infrastructure pathways and outcomes when compared to rural contexts. However, as implied in the discussion of Table 1, this rural-urban distinction hides linkages that are critical in how impacts of investments should be understood. A framework is needed to facilitate comparison between and within the spatial domains. Focusing on disruptions arising from private sector investments in Beira, Mozambique, Shannon et al. (2018, p. 4) proposed a flows approach which enables discussions to go past “livelihood impacts alone” and to also consider how infrastructure investments are both destructive and creative processes. Ideas from Shannon et al. (2018) are transformed into Figure 1.

Figure 1. The flows and spaces approach to infrastructure project analysis. Source: Synthesized from Shannon et al. (2018).

Analysis has to consider the drivers, structural and agency factors as these pervade all projects at all times. Next is understanding characteristics of the primary intervention space and how this is reconfigured in ways that can be creative, destructive, or sustainable/unsustainable. However, such an evaluation (i.e., view on whether processes are creative or destructive) will vary among stakeholders and over time. Significant attention in enforced displacement focuses on dynamics of engagements relating to “Clearing the Space and Displacement” (in Figure 1). Shannon et al. (2018) encourage analysis of the entire chain including characteristics, outcomes and sustainability in the New Spaces–the resettlement spaces as well as the original space now reconfigured. Usually analysis of these spaces is detached from what went on before.

In the case of Harare, some of the new spaces created from previous displacements include Porta Farm camp to the west and Hatcliffe Extension to the North of Harare, respectively. Each of these has layered histories and governance structures. New Spaces for settling the displaced can become clearing spaces at a later date. For instance Hatcliffe Extension was a holding camp (New Space) for those displaced as a result of urban clearing policies (e.g., from Churu Farm in 1993 and Porta Farm). Government and local authority provided services and planned the new area. Yet the state's 2005 Operation Murambatsvina razed to the ground large parts of this settlement (New Space) leaving almost 10,000 people destitute (see e.g., AI, 2006, p. 5). This suggests that the politics of infrastructure projects should be considered well beyond the spatial-temporal confines of the original project itself (beyond primary space in Figure 1) as New Spaces can become “Primary Intervention Spaces.”

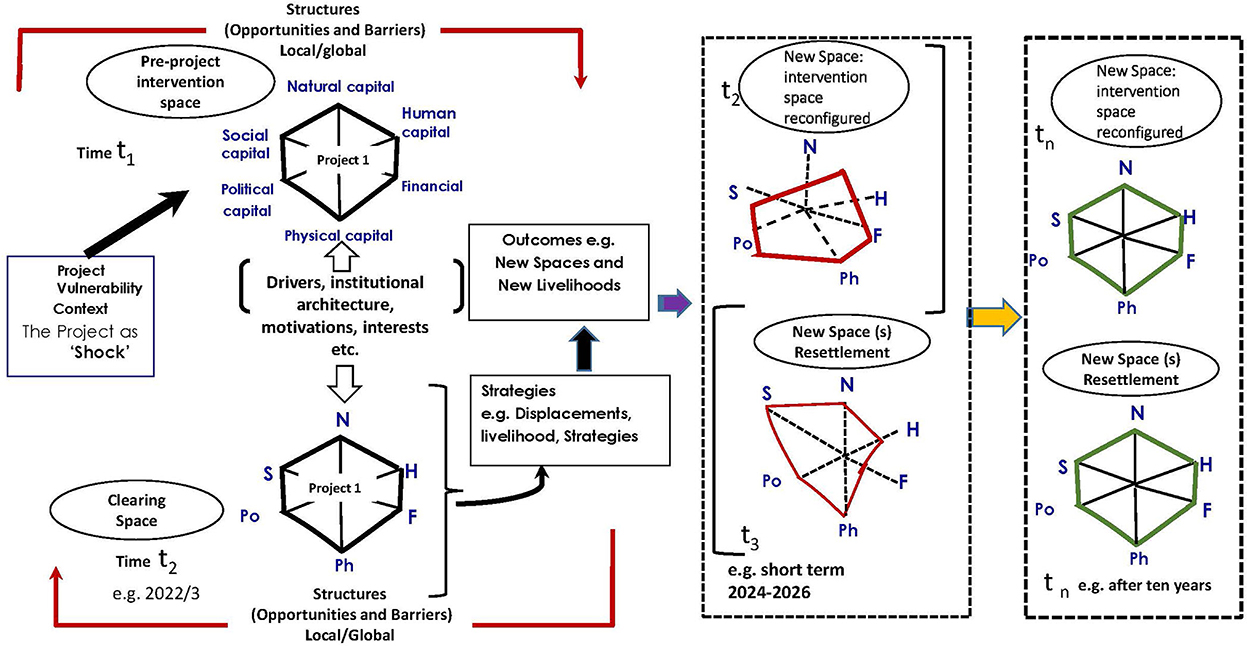

In the analysis of whether and to what extent the New Spaces contribute to urban sustainability and (in) security, people's livelihoods should remain at the core. As concluded at the dawn of the new millennium and enshrined in the UK International Development Act 2002, any discussion of sustainability is inadequate if it is not people centered. Consequently, the flows approach has to be incorporated into some overall version of the sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF) (Rakodi and Lloyd-Jones, 2002; Scoones and Wolmer, 2002). For brevity, such a version is sketched in Figure 2. The contours of change (creative or destructive) can be identified and analyzed vis a vis any of the assets/capitals in the framework.

Figure 2. Consolidated flows, spaces, and livelihoods framework for analysis of infrastructure investment/projects.

In the context of the SLF, infrastructure is part of the physical capital in a neighborhood, city, region or country. Changes in this physical capital enhances and/or destabilizes conditions everywhere else. Crucially, the framework (Figure 2) does not prescribe neither the questions to be asked nor the materials and techniques to be employed for data collection and analysis. All these are context specific and driven by the key research question(s) posed. For post-colonial Southern Africa, the worldwide “infrastructure turn” has generated a surge in displacement of land occupants and livelihoods. In urban areas, such infrastructure induced displacements (with or without official relocation) add to the endemic displacements ordinarily studied under the rubric of planning policy, land and housing (Mbiba, 2022). The framework suggested here could be used to examine whether and to what extent urban displacements differ from those in rural investment across sectors and within sectors. This is an apt juncture at which to return to the Mbudzi Interchange and illustrate some of the basic elements on the utility of the combined flows and livelihoods framework in particular the questions that can be asked and approaches to be taken.

In the context the Zimbabwe transport and communication infrastructure investments, the Mbudzi interchange upgrading (costing US$88 million) is part of the ongoing rehabilitation of the Chirundu- Beit Bridge Highway that has brought excitement among Zimbabweans that it is a harbinger of better things to come. As promised, one could use the framework (in Figure 2) to revisit the questions posed earlier on how to understand processes of infrastructure development.

• Understanding the structure-agency characteristics and how these determine displaceability in this and comparable projects and spaces is a key question. For the Mbudzi Interchange, the state, through the Ministry of Transport is the lead institution. The primary legislation invoked is the Roads Act [Chapter 13:18] (GoZ, 2022). Laws and procedures related to environmental management, compensation, local government etc. are also critical but in this instance in relation to the Roads Act. To what extent are the flow dynamics and space characteristics different where different laws are primary such as in the case of the Mining Act for mining developments (e.g., at Manhizhe in Table 1) related displacements or the agriculture related (as at Chilonga) and dam construction (such Tokwe-Mukosi or Kunzwi dam)? The lead agencies and stakeholders will also vary in all these instances.

• The development intervention is a shock. Analysis of change and how various stakeholder assets are eroded/enhanced and deployed at different times is sorely important for sustainable development goals programming. At 2022, the primary space at Mudzi Interchange became a Clearing Space with processes initiated to upgrade infrastructure (GoZ, 2022). Soon it will be a New Space. Analysis of transitions in this space need to occur simultaneously with that in the relocation spaces (often multiple).

• Analysis may examine inter alia, to what extent the new space dynamics and outcomes (land rights, compensation, displacement and relocation) at Mbudzi Interchange are similar or different from those relating to the Beit-Bridge Border post upgrading or to the various rural cases along the highway spaces. These are spaces where the communal areas village land and land at service centers has had to be incorporated into the new infrastructure that is part of Chirundu–Beit Bridge highway. Whenever land is involved; the project interventions are highly contested. Why do these contestations appear more pronounced in some projects and spaces and not others? Why has the Mbudzi Interchange project generated muted resistance compared to other infrastructure projects, the mining projects, the dam projects (Tokwe Mukosi and Kunzwi dam) and the Chilonga lucerne grass pastures projects? (all listed in Table 1). The role of stakeholders, the governance, and legitimacy of the project as well as of rights to the land are all factors for consideration. Land expropriation is a key feature of infrastructure and development projects in Southern Africa. However, the prevailing perception is that compensation for expropriated lands is inconsistent and unfair (Paradza et al., 2021). Figure 1 combined with Figure 2 act as a sensitizing framework in analysis of how and what structures and capitals determine agency and outcomes and to improve on such outcomes among different stakeholders and spaces.

• As reported in the media (e.g., NewsDay, 2022; The Herald, 2022), the Mbudzi Interchange was going to displace over 150 property owners (residential, commercial and industrial) fifty of whom had title deeds, 135 settled by the City of Harare and the rest illegal settlers. By early November 2022, only five of the property owners with title deeds were yet to agree compensation with the government. Crucially, the Minister of Transport was quoted in the media, affirming that the government would not impose compensation on the property owners (The Herald, 2022). The reported government adherence to legal procedure, professionalism and offer of fully negotiated compensation, if realized, would be unusual in the context of development projects in Zimbabwe. What factors determined this approach by the state, why has this not been the norm or is it the beginning of a new approach to development governance?

• Furthermore, oversight is a critical factor is the governance of development projects in order to achieve transparency and accountability. Ordinarily, the glare of the media and presence of international eyes in urban areas forces governments and private sector developers to be more cautious and more respectful of citizens' rights. Does this “media glare and international eyes” explain the approach taken by the state to address issues of displacement and compensation at Mbudzi? However, in specific contexts, governments may still proceed in ways that trample on these rights. What is the nature and presence of oversight institutions in different project settings and what has determined the different outcomes across projects in “primary spaces,” “clearing spaces” and “new spaces” (Figure 2). What incentives and motivations have guided different stakeholders in the engagements? What knowledge have the different stakeholders brought onto the table?

• Considering the different spaces (Figure 2), what are the “creative” and “destructive” dynamics in the short term, selectively and cumulatively? These dynamics are not just physical, social and economic but also about knowledge. A reading of Fricker (2007) reminds us that physical displacement of citizens in infrastructure and other development projects is accompanied and facilitated by epistemic dispossession in which those to be displaced are denied opportunities to frame the knowledge that underpin interventions as well as the narrative of long-term impacts. Put differently, this invites researchers and policy makers to (at different stages of implementing projects like Mbudzi interchange), examine how the language and knowledge used (to justify actions in planning, clearing spaces, compensation, resettlement etc.) empowers some stakeholders while dis-empowering others. Samson (2015) suggests that the poor suffer epistemic dispossession in most development projects. Indeed the “progress and prosperity” tag that officials attach to infrastructure is in sharp contrast to how (for displaced citizens), mention of the projects evokes anguish, pain, trauma and loss for generations (Isaacman and Isaacman, 2013). The model proposed in this paper calls for the knowledge interrogations to be conducted comparatively over time, in the different spaces (Figures 1, 2) and bringing all stakeholder positions onto the table.

The questions asked above are not exhaustive but just indicative. Their nature and the context will determine the research designs and methods for data collection and analysis. For instance, where records are available and accessible, the primary data collected will start from a different footing compared to a context with no such data. In-depth understanding may require much grounded qualitative approaches. Such approaches combined with complementary surveys may be needed to arrive at quantitative profiles required to deal with compensation issues. Historical data and people's testimonies may be used to help understand interlinkages of dynamics in different spaces and among stakeholders.

Conclusions

This article sought to extend debates on development induced displacement with specific reference to infrastructure projects given the prevailing infrastructure turn (Dodson, 2017). It argued that contrary to Shannon et al. (2018), urban displacements are as significant as the rural and that public investments are as dominate as the private. The categorisations (rural vs. urban) are not always helpful as interlinkages dominate rural and urban projects as well as private and public investments. While contesting some of the generalizations made in Shannon et al. (2018), the paper adopted the “flows and spaces” approach they proposed and combined this with the sustainable livelihoods framework concepts to suggest a more comprehensive flows and livelihoods framework. Given the complexity of infrastructure projects and diversity of contexts even within one jurisdiction, generalization should not be the expected outcome of using the framework. Instead, the framework is a heuristic device (Randolph and Storper, 2022) that enables in-depth understanding, learning and lessons sharing across spaces over time. The Mbudzi Interchange upgrading referred to in this paper is ongoing and has not been examined in detail. Anticipating that local scholars and practitioners will want to study this and other infrastructure interventions, the paper offers a framework that several scholars could use to enable comparative in-depth studies.

There has been a dearth of infrastructure investment in Zimbabwe for over two decades. However, as witnessed in Mozambique (Shannon et al., 2018; Baeta, 2022) this may change and the country may become attractive to global and regional investors. Already, since 2017, there has been noticeable and welcome public sector investment in water, energy, and transport infrastructure as well as in mining; with Chinese funding a major feature. The flows, spaces and livelihoods framework proposed in this paper would be a handy conceptual starting point to examine the sustainability of past and future interventions in a comparative way irrespective of whether these interventions are rural or urban, micro or macro. It is a framework that makes it possible to examine both the heterogeneous precariousness and opportunities that arise from infrastructure projects.

Much of the literature on infrastructure puts emphasis on the economic growth impacts or at the local level, the vulnerability and insecurity of rights for those occupying the land. Extending space arguments from Shannon et al. (2018), the framework proposed in this paper recognizes linked spaces (pre-intervention spaces, clearing spaces and new spaces) that need to be analyzed taking into account both destructive and creative dynamics in these spaces. The determinants of how livelihoods, politics and sustainability of these spaces evolve are candidates for comparative research and policy learning.

Author contributions

BM was responsible for paper conceptualization, data curation, and writing–drafting and editing.

Funding

This was a self-financed project. The study reported in this paper received no funding from a public body, research funding organisation, international development agencies, private sector or civil society.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2022.1045646/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The 1980s delivered inter alia mass education, free health services, agricultural extension and marketing services to previously marginalised majority peasants in the countryside and owner-occupied housing in urban areas.

2. ^“Kunzvi Dam: A tale of hope, expectation anxiety.” The Sunday Mail, Harare, 3rd April 2022. https://www.sundaymail.co.zw/kunzvi-dam-a-tale-of-hope-expectation-anxiety (last visited 7th September 2022).

3. ^See for example Gukurume and Nhondo (2020).

4. ^“Sese's gem war: inside villagers' feud with Murowa Diamonds,” The Herald, Harare, 31st July 2021, https://www.herald.co.zw/seses-gem-war-inside-villagers-feud-with-murowa-diamonds/ (last visited 7th September, 2022).

5. ^“Mvuma steel plant takes shape, affected families compensated,” NewZimbabwe.com, 27th May 2022. https://www.newzimbabwe.com/mvuma-steel-plant-takes-shape-affected-families-compensated/ (last visited 7th September 2022).

6. ^“Zimbabwe: 12 000 Chilonga villagers face eviction after losing High Court battle,” Land Portal, 6th January 2022 https://landportal.org/node/101324 (last visited 7th September 2022); “Frontier politics in Zimbabwe: the Chilonga case” Agriculture Futures, 28th March 2021. https://www.future-agricultures.org/blog/frontier-politics-in-zimbabwe-the-chilonga-case/ (last visited 7th September 2022).

7. ^See Mbiba and Chiwanga (2006) for a detailed account on the nature of burials at this cemetery and the double meaning of “kuMbudzi”.

References

AI (2006). Zimbabwe: Quantifying Destruction- Satellite Images of Forced Evictions. Amnesty International (AI), 8th September 2006, AI Index, AFR46/014/2006. Available online at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/afr460142006en.pdf (accessed October 31, 2022).

Auret, M. (1994). Churu Farm: A Chronicle of Despair. Harare: Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace (CCJP).

Baeta, P. V. (2022). The Right to the City in Disputed Sites: Urban Redevelopment and the Street Economy Space Nexus in Maputo, Mozambique. Unpublished PhD Thesis, School of the Built Environment, Oxford Brookes University.

COHRE (2009). Forced Evictions: Violations of Human Rights No.11. Geneva: COHRE (Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions)

Di Nunzio, M. (2022). Evictions for development: creative destruction, redistribution and the politics of unequal entitlements in inner-city Addis Ababa (Ethiopia), 2010–2018. Polit. Geogr. 98, 102671. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102671

Dodson, J. (2017). The global infrastructure turn and urban practice. Urban Policy Res. 35, 87–92. doi: 10.1080/08111146.2017.1284036

Du Plessis, J. (2005). The growing problem of forced evictions and the crucial importance of community –based, locally appropriate alternatives. Environ. Urban. 17, 123–134. doi: 10.1177/095624780501700108

DW (2005). Urban land reform in post war Luanda: research, advocacy and policy development. Luanda: Development Workshop (DW), in association with One World Action (UK), CEHS, Edinburgh and supported by DFID (UK), Norwegian Foreign Ministry and Novib, The Netherlands.

Escobar, A. (2004). Development, violence and the new imperial order. Development 47, 15–21. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.development.1100014

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198237907.001.0001

Goodfellow, T. (2020). Finance, infrastructure and urban capital: the political economy of ‘gap-filling'. Rev. Afr. Political Econ. 47, 256–274. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2020.1722088

GoSA. (2022). Judicial Commission of Inquiry Into State Capture: Corruption and Fraud in the Public Sector Including Organs of State, (six volumes). Pretoria: Government of South Africa/Republic of South Africa. Available online at: https://www.statecapture.org.za/ (accessed September 6, 2022).

GoZ (2019). Presentation of report “The Commission of Inquiry into the matter of sale of state land in and around urban areas since 2005” (Chaired by Justice Uchena): Summarising Findings and Recommendations. Harare: Government of Zimbabwe. Available online at: http://veritaszim.net/node/3847 (accessed September 6, 2022).

GoZ. (2022). General Notice 1173 of 2022. Roads Act (chapter 13:18] Notice of Closure of Potions of Harare- Masvingo Road, Chitungwiza Road and High Glen Road at Mbudzi Roundabout. Zimbabwe Government Gazette, 27th May 2022, Harare.

Gukurume, S., and Nhondo, L. (2020). Forced displacements in mining communities: politics in Chiadzwa area, Zimbabwe. J. Contempor. Afr. Stud. 38, 38–54. doi: 10.1080/02589001.2020.1746749

Hammer, A. (2016). Urban displacement and resettlement in Zimbabwe: the paradoxes of propertied citizenship. Afr. Stud. Rev. 60, 81–104. doi: 10.1017/asr.2017.123

Harrison, P., Huchzermeyer, M., and Mayekiso, M. (2003). Confronting Fragmentation: Housing and Urban Development in a Democratising Society. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press.

Huchzermeyer, M. (2003). Housing rights in South Africa: Invasions, evictions, the media, and the courts in the cases of Grootboom, Alexandra, and Bredell. Urban Forum 14, 80–107. doi: 10.1007/s12132-003-0004-y

Isaacman, A. F., and Isaacman, B. I. (2013). Dams, Displacement and the Delusion of Development: Cahora Bassa and Its Legacies in Mozambique, 1965-2007. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. doi: 10.1353/book.22451

Jordhus-Lier, D. (2015). Community resistance to megaprojects: the case of the N2 gateway project in joe slovo informal settlement, Cape Town. Habitat. Int. 45, 169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.02.006

Kamete, A. Y. (2007). Cold-hearted, negligent and spineless? planning, planners and the (r) ejection of ‘filth' in urban Zimbabwe. Int. Plan. Stud. 12, 153–171. doi: 10.1080/13563470701477959

Kanai, M. J., and Schidler, S. (2022). Infrastructure-led development and the peri-urban question: Furthering crossover comparisons. Urban Stud. 59, 1597–1617. doi: 10.1177/00420980211064158

Leonard, L., Musavengane, R., and Siakwah, P. (2021). Sustainable Urban Tourism in Sub-Sahara Africa: Urban Risk and Resilience. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003024293

Maharaj, B. (2015). The turn of the south? social and economic impacts of mega-events in India, Brazil and South Africa. Local Econ. 30, 983–999. doi: 10.1177/0269094215604318

Manji, A. (2015). Bulldozers, homes and highways: nairobi and the right to the city. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 42, 206–224. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2014.988698

Matamanda, A. R., and Mphambukeli, T. N. (2022). Urban (in) security in an emerging human settlement: perspectives from Hopley Farm settlement, Harare, Zimbabwe. Front. Sustain. Cities 4:933869, doi: 10.3389/frsc.2022.933869

Mbiba, B. (2018). Planning scholarship and the fetish about planning in Southern Africa: the case of Zimbabwe's operation Murambatsvina. Int. Plann. Stud. 24, 97–109. doi: 10.1080/13563475.2018.1515619

Mbiba, B. (2022). The mystery of recurrent housing demolitions in urban Zimbabwe. Int. Plann. Stud. 27, 320–335. doi: 10.1080/13563475.2022.2099353

Mbiba, B., and Chiwanga, P. C. (2006). Death and the City in the Context of HIV/AIDS: The Case of Harare. Chapter 3 in Mbiba. B. (ed.) Death and The City in East and Southern Africa. London: The Urban and Peri-Urban Research Network (Peri-NET) Working Papers, 10–13. ISSN 1752-1912.

Minujin, A. (1995). Squeezed: The middleclass in Latin America. Environ. Urban. 7, 153–166. doi: 10.1177/095624789500700214

Miraftab, F. (2009). Insurgent planning: situating radical planning in the Global South. Plann. Ther. 8, 32–50. doi: 10.1177/1473095208099297

Muller, G. (2013). The legal-historical context of urban forced evictions in South Africa. Fundamina J. Legal Hist. 19, 367–396. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264556208_The_legal-historical_context_of_urban_forced_evictions_in_South_Africa

NewsDay (2022). Mbudzi Interchange victims compensated. NewsDay, Harare (10th November, 2022). Available Online at: https://www.newsday.co.zw/local-news/article/200003300/mbudzi-interchange-victims-compensated (accessed November 17, 2022).

Newton, C. (2009). The reverse side of the medal: about the 2010 FIFA World Cup and the beautification of the N2 in Cape Town. Urban Forum 20, 93–108. doi: 10.1007/s12132-009-9048-y

Paradza, P., Yacim, J. A., and Zulch, B. (2021). Consistency and fairness of property valuation for compensation for land and improvements in Zimbabwe. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 29, 67–84. doi: 10.2478/remav-2021-0030

Pillay, U., Tomlinson, R., and Bass, O. (2009). Development and Dreams: The Urban Legacy of the 2010 Football World Cup. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council Press.

Potts, D. (2011). Shanties, slums, breezeblocks and bricks (Mis) understandings about informal housing demolitions in Zimbabwe. City Anal. Urban Change Ther. Action 15, 709–721. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2011.611292

Rakodi, C., and Lloyd-Jones, T. (2002). Urban Livelihoods: A People Centred Approach to Reducing Poverty. London: Earthscan Publications Limited.

Randolph, F. R., and Storper, M. (2022). Is urbanisation in the global south fundamentally different? Comparative global analysis for the 21st century. Urban Studies, 1–23. doi: 10.1177/00420980211067926

Ray, B. (2010). Residents of Joe slovo community v thubelisha homes and others: the two faces of engagement. Hum. Rights Law Rev. 10, 360–371. doi: 10.1093/hrlr/ngq002

Samson, M. (2015). Accumulation by dispossession and the informal economy–struggles over knowledge, being and waste at a Soweto garbage dump. Environ. Plan. D. Soc. Space 35, 813–830. doi: 10.1177/0263775815600058

Scoones, I., and Wolmer, W. (2002). Introduction: livelihoods in crisis: challenges for rural development in Southern Africa. IDS Bull. 34, 1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2003.tb00073.x

Shannon, M., Otsuki, K., Zoomers, A., and Kaag, M. (2018). Sustainable urbanisation on occupied land? the politics of infrastructure development and resettlement in Beira City, Mozambique. Sustainability 10, 1–18. doi: 10.3390/su10093123

The Herald (2022). Mbudzi Interchange: 46 Property Owners Accept Compensation Awards. The Herald, Harare (10th November 2022). Available Online at: https://www.herald.co.zw/mbudzi-interchange-46-property-owners-accept-compensation-awards/ (accessed November 17, 2022).

UN-HABITAT (2005). Report of the Fact Finding Mission to Zimbabwe to Assess the Scope and Impact of Operation Murambatsvina by the UN Special Envoy on Human Settlements Issues in Zimbabwe, Mrs Anna Kajumulo Tibaijuka (July 2005). Nairobi: United Nations HABITAT.

UN-HABITAT (2007). Enhancing Urban Safety and Security. Global Report on Human Settlements, 20027. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT).

Keywords: urban, infrastructure, displaceability, livelihoods, human security, post-colonial Africa

Citation: Mbiba B (2022) Urban infrastructure development-human security nexus: Flows, spaces, and livelihoods framework for comparative research in Africa's post-colonies. Front. Sustain. Cities 4:1045646. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2022.1045646

Received: 15 September 2022; Accepted: 21 November 2022;

Published: 21 December 2022.

Edited by:

Ojonugwa Usman, Istanbul Commerce University, TurkeyCopyright © 2022 Mbiba. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Beacon Mbiba, Ym1iaWJhQGJyb29rZXMuYWMudWs=

Beacon Mbiba

Beacon Mbiba