95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Sustain. Cities , 26 November 2021

Sec. Urban Resource Management

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2021.725620

This article is part of the Research Topic The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Transformation of Human Relationships with Nature at Multiple Scales View all 21 articles

In addition to impacts on human health and the economy, COVID-19 is changing the way humans interact with open space. Across urban to rural settings, public lands–including forests and parks – experienced increases and shifts in recreational use. At the same time, certain public lands have become protest spaces as part of the public uprisings around racial injustice throughout the country. Land managers are adapting in real-time to compound disturbances. In this study, we explore the role of the public land manager during this time across municipal and federal lands and an urban-rural gradient. We ask: How adaptable are public land managers and agencies in their recreation management, collaborative partnerships, and public engagement to social disturbances such as COVID-19 and the co-occurring crisis of systemic racial injustice brought to light by the BLM uprisings and protests? This paper applies qualitative data drawn from a sample of land managers across the northeastern United States. We explore management in terms of partnership arrangements, recreational and educational programs, and stakeholder engagement practices and refine an existing model of organizational resilience. The study finds abiding: reports of increased public lands usership; calls for investment in maintenance; and need for diversity, equity, and inclusion in both organizational settings and landscapes themselves; and the need for workforce capacity. We discover effective ways to respond to compound disturbances that include open and reflective communication, transforming organizational cultures, and transboundary partnerships that are valued as critical assets.

In addition to the devastating impacts on human health and the global economy, COVID-19 has changed the way humans interact with open space, natural resources, and public lands (Soga et al., 2021). Under anything but the most extreme situations, outdoor walks and exercise at safe distances were not only allowed, but encouraged for sustaining physical, mental, and emotional health and well-being (Samuelsson et al., 2020; Slater et al., 2020). While research on overarching patterns of open space use during the pandemic is still emerging—the use of some natural areas, parks, forests, trails, and bike paths increased (Grima et al., 2020; Venter et al., 2020; Outdoor Industry Association and Naxion Research Consulting, 2021; Plitt et al., 2021 this issue), but this increase was moderated by park closings and occurred more often in white majority neighborhoods in cities (Jay et al., 2021). Certain spaces became overcrowded, and some were closed to public use during the peak of the pandemic. At the same time, many land managers were often deemed “essential”, operating under new protocols to ensure that these resources remained open to the public. Public land managers in both rural and urban settings had to adapt old practices in real-time to a new and changing reality (Jacobs et al., 2020; McGinlay et al., 2020; Miller-Rushing et al., 2021; Sainz-Santamaría and Martinez-Cruz, 2021). Updating fieldwork protocols, adjusting workforces, canceling or changing public events, and providing educational content online are just a few of the adaptations. As the crisis deepened and spread, the impacts on how public land managers steward natural resources and support recreation and public engagement opportunities continued to unfold.

The COVID-19 pandemic is entwined with the concurrent crisis of systemic racial injustice. While structural inequality and systemic racism have long been part of our society, this injustice was brought to broader public attention following the murder of George Floyd and the uprisings and protests as part of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement during summer 2020. In addition to the focal attention on police violence, this movement amplified conversations about disproportionate impacts of the pandemic on people of color, as well as foregrounding issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in all aspects of society (Lipp, 2015; Rodriguez, 2020). For public land managers and urban park professionals, this centered on who feels safe, welcome, and served in green spaces (Hoover and Lim, 2021; Klein et al., 2021), which has been a critical question of recreation research and management particularly in light of changing demographics and values around outdoor experiences (see, e.g., Blahna Dale et al., 2020). During COVID-19 as well as before, many residents could not access larger public lands and natural areas for reasons that include inequitable distribution of open space, physical limitations, reduced transit options, time constraints, or lack of familiarity (Jennings et al., 2012; Jacobs et al., 2020; Lopez et al., 2020; Spotswood et al., 2021). These twinned crises revealed underlying inequities and vulnerabilities that cause people to experience risk and interact with the public realm in different ways (see, e.g. Bassett et al., 2020; McPhearson et al., 2020).

Disturbances do not happen in isolation; they often co-occur or compound upon each other spatially and temporally, creating intersecting impacts and influencing adaptation, and they are situated in longer historical arcs of prior disturbance cycles and underlying social vulnerabilities (Steinberg, 2006). Quigley et al. (2020) define “concurrent hazards” as hazardous events of biophysical origin (e.g., earthquake, cyclone) that overlap in space and time, whereas “compound events” can be hazardous events of any origin that co-occur (e.g., COVID-19 and a hurricane). New research has begun to examine the compound crises of how COVID-19 intersects with other forms of disturbance, including wildfire and systemic racism (see, e.g., Goldstein, 2021; Landau et al., 2021 this issue). Rodriguez (2020) frames COVID-19 as an “interlocking health crisis” that is fundamentally connected with systems of oppression and examines the ways in which both NYC residents in general and social workers in particular work to dismantle these systems (see also Lipp, 2015; Reynolds, 2020). Examining wildfires in Arizona, Edgeley and Burnett (2020) found that current challenges around collective action to address wildfire risk may be further exacerbated due to COVID-19 and the pandemic has potentially widened existing disparities in household capacity to conduct wildfire risk mitigation activities in the wildland–urban interface. COVID-19 must be considered as a disturbance that intersects with structural forces, including pre-existing social inequities and vulnerabilities, leading to “cascading disasters” and inequitable outcomes (Thomas et al., 2020). Response to disturbances–compound or otherwise–is dependent upon processes, practices, and socio-cultural norms in place prior to the event (Harrison and Williams, 2016).

In a land management context, disturbances are often examined for their impact on the landscape and biophysical components of the ecological system (Dolan et al., 2017); leaving a need to examine social disturbances such as racial injustice and pandemics. Particular attention has focused on weather-based and insect-based disturbances, such as wildland fire, bark beetle, pine beetles, and hurricanes (Cannon et al., 2017; Hislop et al., 2018; Van Beusekom et al., 2018 Morris et al., 2018; Bowd et al., 2019; Negrón and Cain, 2019; Vogeler et al., 2020). Disturbances, acting as “focusing events,” and their subsequent “policy windows” also enable organizational learning and adaptation (Michaels et al., 2006). The Forest Service has been shown to learn from responding to both fire (Petersen and Wellstead, 2014) and insect infestation (Steen-Adams et al., 2020; Abrams et al., 2021). At the same time, scholars also point to the presence of “rigidity traps” in fire management approaches that limit the ability for institutional innovation by the agency and its collaborative partners (Butler and Goldstein, 2010). Based on a survey of local governments, Dzigbede et al. (2020) found that preparedness for weather-related natural disasters informs responses to the current crises, yet not all disasters lead to permanent changes in rules and regulations, and this holds in the case of local governments post-fire (Mockrin et al., 2018). In examining pathways of transformation, Newig et al. (2019) highlight the role of failure in organizational learning, noting that “institutional improvement through learning and adaptation resulting from crisis experience happens in a rather ad hoc manner” (p 5). Finally, researchers are re-conceptualizing focusing events and their potential effects on windows of opportunity as a result of the long-term nature of COVID-19 and other pulse events (DeLeo et al., 2021).

Organizational cultures of public land management agencies at multiple organizational levels have long been a subject of scholarship. Kaufman (1960) sought to understand how the Forest Service maintained organizational coherence at such a broad and dispersed geographic scale. Fleischman (2017) revisited Kaufman's findings and examined the contemporary Forest Service, finding that Kaufman's analysis under-explored the importance of political context–as opposed to internal organizational dynamics alone–in shaping outcomes. Further, it is important to acknowledge that large federal agencies are not monolithic. “Street level bureaucrats” working on national forests have some room to maneuver and innovate, but also they are nested within a larger bureaucratic and institutional structure (Lipsky, 1980; Trusty and Cerveny, 2012; Moseley and Charnley, 2014). Recent scholarship continues to emerge about the culture and capacity of land management agencies operating in urban areas or at the municipal level, including from the lenses of: public lands management (Zamanifarda et al., 2016), parks and recreation management (Farland, 2010), urban forestry management (Wirtz et al., 2021), tree planting initiatives (Eisenman et al., 2021), and green infrastructure governance (Hsu et al., 2020). Though various factors are identified and discussed, these studies point to the importance of financial resources from both public and private sectors, leadership, collaborative management approaches with multiple stakeholders, and data-driven decision-making as key components in successful outcomes. Homing in on the culture of urban parks and recreation organizations, Farland (2010) found that these agencies have an “achievement” orientation as their dominant culture, as well as an increasing emphasis on professionalization and accreditation in the field.

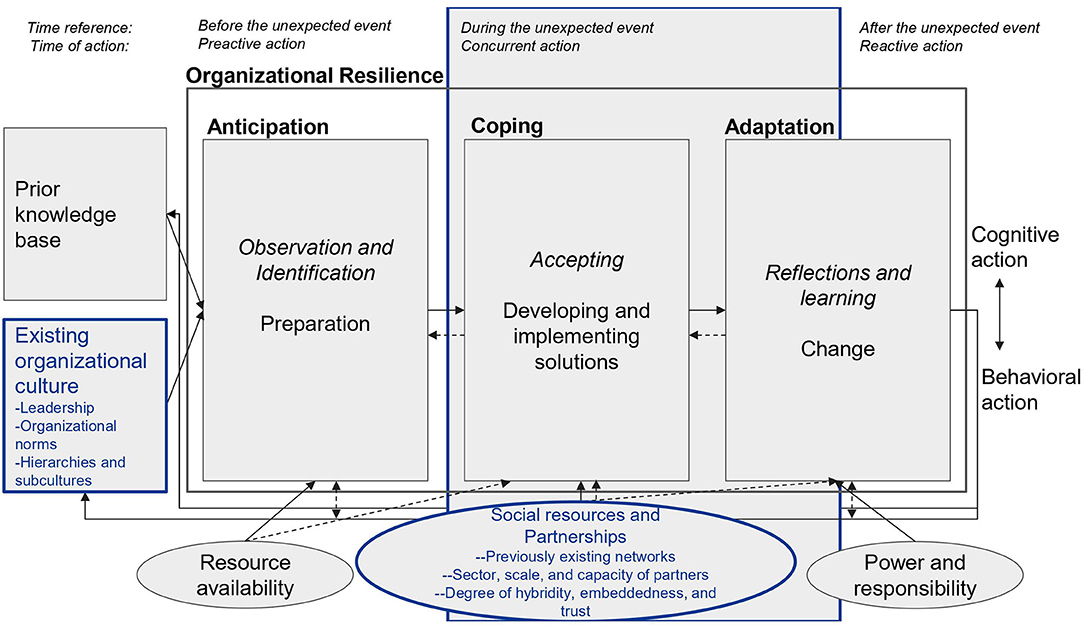

To understand whether, where, and how organizational adaptation and transformation happens in response to disturbance, it is necessary to interrogate pre-existing organizational cultures, capacities, and capabilities. The study of contemporary organizational culture and learning developed initially to examine private firms, but also has been applied to the government sector (Edginton, 1987; Schein, 1992; Coleman and Thomas, 2017) and draws attention to the role of bureaucratic structures and their influence on learning (Cuffa and Steil, 2019). A review by Gilson et al. (2009) identifies knowledge management and organizational learning (and “unlearning”) as key components of government sector organizational culture involved in adapting to crises. Abrams et al. (2017), focusing on land management agencies, point to the enduring importance of bureaucratic institutions and how “institutional persistence and path dependence in limiting the latitude of adaptation to social and environmental shocks” (p.1). Other scholars have called for a focus on not only moments of crisis and disaster management, but also “slow variables” that create mounting pressure on SES (Duit, 2016). Wyborn et al. (2015), examining the adaptive capacity of land management agencies, identify multiple potential “adaptation pathways” that are also constrained by structural “envelopes” that shape potential action. Organizational resilience has also been conceptualized through a capability-based framework. Duchek (2020) identifies proactive, concurrent, and reactive actions that organizations take in response to a disturbance, which occur through processes of anticipation, coping, and adaptation, respectively, which are enabled or constrained by resource availability, social resources, power and responsibility (see Figure 1, p. 224). Duchek also notes two types of actions: cognitive and behavioral occurring within these processes and identifies strong and weak feedback loops. Their study investigates partnerships as an adaptive pathway that enables land management agencies to respond to large scale and concurrent disturbances.

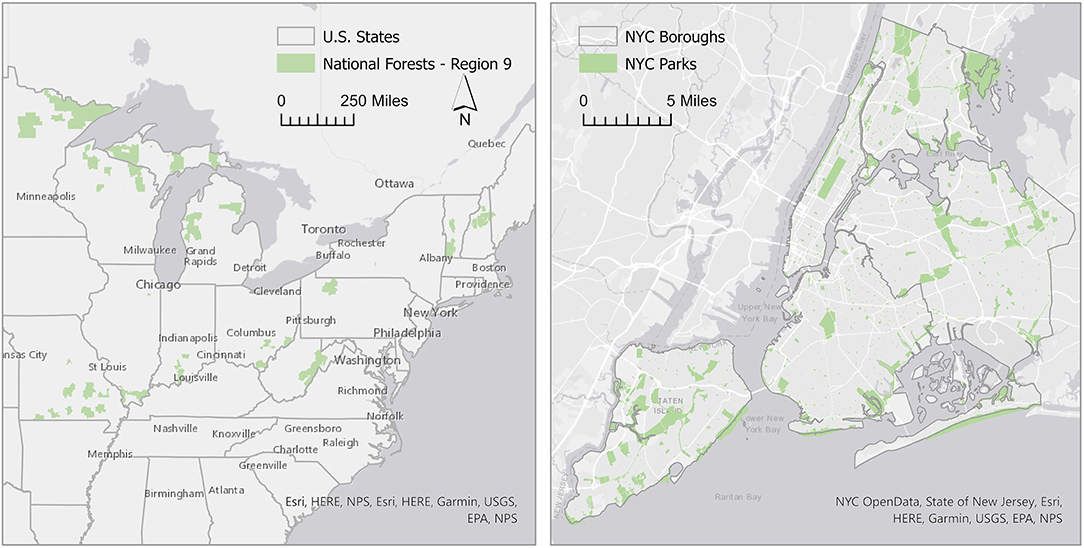

Figure 1. Map of the study area. Left: Forest Service Eastern Region National Forests and Grasslands. Right: New York City parkland. Map created by Michelle Johnson.

Federal and other government land management agencies do not manage natural resources or respond to disturbance alone–they work in collaborative arrangements with a wide range of stakeholders, partners, and cooperators in a governance network that spans sectors and scales. These arrangements among land management actors have variously been explored as co-management (Wondolleck and Yaffee, 2000; Tompkins and Adger, 2004; Koontz and Thomas, 2006; Armitage et al., 2007) and multi-level or networked governance (Bodin and Crona, 2009; Davis and Reed, 2013; Scarlett and McKinney, 2016; Abrams et al., 2017; Abrams, 2019). Focusing on recreation management, partnerships and collaboration are seen to be critical to adding capacity and implementing sustainable practices (Charnley et al., 2014; Selin et al., 2020). Steen-Adams et al. (2020) analyzed the emergence of network governance approaches within the Forest Service in the context of an invasive pest outbreak. The authors found that these network approaches offered added capacity and local legitimacy, but the emergence of networks is driven by preexisting top-down and bottom-up factors–including existing capacity and prior engagement in network approaches (i.e. “network history”).

Urban forest and green space management occurs in a context of a patchwork landscape of multiple landowners and a networked or “mosaic” governance arena (Jansson and Lindgren, 2012; Buijs et al., 2019). In examining and analyzing urban forestry and public lands management, it is important to consider the power dynamics and politics that underlie and shape the planning, programming, and implementation of collaborative partnerships and network governance arrangements (Campbell and Gabriel, 2016; Hsu et al., 2020). Municipal government often plays a lead role in the management of urban tree canopy on streets, in parks, and in “natural area” forested parks (Campbell, 2014, 2017). An array of public-private partnerships and private contracting arrangements exist in the financing and management of urban green spaces, which have variously been celebrated as adding capacity and nimbleness or critiqued as the roll-back of the state under neoliberal approaches that emphasize market efficiencies (de Magalhães and Carmona, 2009; Lindholst, 2017). Civil society–including non-governmental organizations and civic groups– also provide capacity for environmental stewardship (Svendsen and Campbell, 2008), engage in programming and planning that axctivate open space to function as social infrastructure (Campbell et al., 2021), and participate as key brokers in environmental governance networks (Connolly et al., 2013, 2014), but they are uneven across the landscape (Johnson et al., 2019).

Given this context and background, we posed the overarching research question: How adaptable are public land managers and agencies in their recreation management, collaborative partnerships, and public engagement to large scale social disturbances such as COVID-19 and the co-occurring crisis of systemic racial injustice brought to light by the BLM uprisings and protests? We conducted semi-structured interviews with representatives of two public land management agencies operating under different authorities and geographic contexts: urban forested parks in New York City (NYC) operated by the City of New York Department of Parks and Recreation (NYC Parks) and National Forests within the Eastern Region (Region 9, or R9) of the USDA Forest Service National Forest System (Forest Service). Our study area focuses in the northeast United States because it contains public lands and communities that allow for comparison between two different organizational settings working across an urban to rural gradient. We draw upon and test Duchek's (2020) process-based conceptual model of organizational resilience through stages of the prior knowledge base, anticipation, coping, and adaptation (see Duchek, 2020, Figure 1, p. 224) with our public land manager cases, examining how the nature of these concurrent crises affect public agencies as they adapt and potentially transform in response to these inherently social disturbances and underlying inequities. Considering Lipsky (1980) as well, we look for differences in hierarchy and degree of trust as both are important in shaping organizational culture and subcultures. In doing so, we apply organizational resilience literature to public agencies experiencing disturbances at present less examined by this literature: press disturbances requiring immediate responses. Our work also contributes empirical knowledge about municipal land managers, an understudied subject, in conversation with a more well-studied subject, federal public land managers.

We conducted a total of 36 semi-structured interviews with public land managers in the northeastern United States from July to November 2020, a period that encompasses the initial wide spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States before the development of a vaccine–including an early concentration in New York City. Through our study design, we sought to understand the patterns and processes associated with collaboratively managing public lands for recreation and public use on national forests and on urban parkland. In setting the comparative frame, we chose two agencies that were generally aligned in mission and structure, but that vary in terms of geographic context. We interviewed state land managers as well but were unable to reach saturation due to challenges with recruitment and time and resource constraints–as such we excluded those from these analyses. The Forest Service Eastern Region consists of more than 12 million acres spread across 17 National Forests and one National Tallgrass Prairie. Over 40% of the population of the United States lives within the footprint of the Eastern Region–which extends across the Northeast and Midwestern United States. The Eastern Region is distinct with many forests adjacent to urban or urbanizing areas. Still, there are forests within this region that fall within the wildland-urban interface and surrounded by rural counties. NYC is home to approximately 8.8 million people and NYC Parks is the largest public land management agency in the city. NYC Parks is responsible for the care of 30,000 acres–of which approximately one third are forested “natural areas”–across more than 5,000 individual parks (See Figure 1). While national forest lands may be larger in terms of number of acres managed, city parklands are situated within a much greater population density and have extremely high rates of usership. During times of crisis, with such differences in density and geographic context, partnerships and stakeholder engagement in the management of public lands differ and should be examined.

Despite what appears to be stark differences, the two agencies share similar objectives at the broadest scale: to manage public land for the health and vitality of people, plants, and wildlife. Both NYC Parks and the Forest Service engage in the type of land management that includes tending to a wide range of conservation practices while assuring that these lands remain open and accessible to the public for sanctioned use. This study focuses on recreation-based partnerships designed to engage the public. Both agencies operate within regulatory frameworks that guide management and community engagement. The agencies have similar scaled staffing structures that include national or city-wide leadership, forest or park administrators (or park districts), and common field positions (e.g., foresters, rangers, enforcement officers, seasonal workforce, public affairs officers, educators, and scientists). During peak periods of quarantine, both NYC Parks and National Forests were staffed primarily by maintenance workers that were given only the most essential tasks related to trash and signage.

For NYC interview recruitment we included municipal land managers working at NYC Parks (n=9), including seven park administrators who manage large parks and forested areas spread across the five boroughs and two employees who manage partnerships and volunteers citywide. For the Forest Service, we reached out to partnership and volunteer coordinators working on Region 9 National Forests, interviewing 1–2 representatives at each of the National Forests (but not including the National Tallgrass Prairie in the Region) (n = 16), and an additional “spot check” interviews with key leaders at the national level (n = 11). Interviews covered a wide range of topics, including emergence of new strategies, learning, adaptation, and transformation of existing practices, ways in which partnerships are created, how the state-society boundary is navigated, and visions for the future. Interviews took place during the peak outdoor recreation season from June through early fall in 2020. The murder of George Floyd occurred on May 25, 2020 and ensuing protests were underway in many parts of the country. During this period, many states were under strict stay-at-home orders, dependent upon the number of COVID-19 cases.

Interviews were voluntary and confidential in nature (Rutgers University IRB Pro2020001281), lasted approximately 1 h, and were conducted entirely via Zoom video conference. Following the receipt of informed consent, interviews were recorded as audio transcripts, which were auto transcribed and then corrected for accuracy. Each interview was conducted by two researchers from among the team, and immediately following each interview, debrief notes about the core themes and findings were discussed. A total of 154 pages of debrief notes and 478 pages of interview transcripts were generated in this process. Following a process informed by grounded theory (Strauss and Corbin, 1998), at several points throughout the project, full team debriefs were discussed to identify emerging themes and patterns. These emerging themes were then developed into preliminary findings presentations, which were shared with communities of practice at both the municipal and federal levels as a “member check” and a way of validating and ground-truthing preliminary results (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). We then compared these cases and their emergent themes against an existing model of organizational resilience (Duchek, 2020) to empirically examine and refine this model for public land managers and long-term disturbance contexts.

NYC Parks managers reported record-breaking rates of visitation throughout the spring and summer of 2020. During the height of NYC's quarantine period, small neighborhood parks and playgrounds were closed to the public while the larger parks remained open to the public. By late spring, it was clear that outdoor public space and specifically parks became the only places that people could gather in small groups and seek respite from their homes during stay-at-home orders. One administrator said, “People are really seeking a natural experience and trying to find solitude, which I think is obviously becoming increasingly difficult with all the people” (NYC Parks, R1). As most other businesses, offices, and schools were closed, people turned to public lands not only to recreate, but also to adapt other activities that now were only safer outdoors. Land managers observed parks being used for classrooms and summer camps, sites for exercise classes, outdoor workplaces, and even field hospital sites.

Park managers felt overwhelmed by the new maintenance that needed to be performed and struggled to keep parks clean and safe for new and returning users. At the same time, administrators were heartened by the new surge of use and appreciation for parks and forested areas, and the ability to provide a vital space for New Yorkers during the early days of the pandemic. As one park administrator described:

“It felt like every day was a weekend… people were using the park to do their job, working remotely, for their spiritual well-being, for physical activity, you name it. It was all happening in the parks. The level of trash that was generated was unprecedented so, in the parks we're teeming with activity, which was wonderful. But then there was that side effect.” (NYC Parks, R4)

The impacts of these intensified maintenance demands were felt doubly as many parks lost significant staff due to city budget cuts in response to the pandemic. A city-wide hiring freeze eliminated crucial seasonal maintenance positions. One park administrator described the situation as having “twice as many people (in the parks) and half the staff” (NYC Parks, R9). Additionally, social distancing rules prevented the gathering of large groups of volunteers, which for many land managers was a huge loss of maintenance labor on which they had come to depend.

The murder of George Floyd and the subsequent uprisings against racial injustice had an impact on both how parks were used across NYC and the internal culture of NYC Parks. As public outrage grew, NYC Parks granted permits and allowed protesters to gather in publicly visible areas in parks such as sport fields and landscaped parkland, at times even working with local police forces to discuss the events before-hand and help to ensure the safety of the protesters.

“Our parks are seen as a safe haven and when we did have protests and vigils for the most part, they were very constructive… I found it very encouraging that the park was a neutral ground where people could come together in a very diverse neighborhood and things remained respectful.” (NYC Parks, R4)

In addition to anti-police and BLM protests and vigils, NYC Parks staff also mentioned that there were other counter protests happening in parks, such as pro-police protests and, in one case, an anti-lockdown protest. There were some cases in which park administrators mentioned conflicts between BLM protesters and pro-police protesters which turned “violent” or “ugly.” Another racially charged incident occurred in Central Park in May 2020 in which a white woman called 911 to report a Black birdwatcher after he asked her to leash her dog. This incident ignited further discussion on access, safety, and inclusion in parks.

Beyond protests and other actions happening in parks, this moment of national reckoning also stimulated discussion and reflection within the workplace. The NYC Parks Commissioner and senior staff sent emails reflecting on the moment in time. Additionally, the agency, starting first with people of color in a Black-only affinity space, planned and hosted listening sessions in which staff were able to share their feelings, not only about the current moment, but on the staff experiences with racism and agency culture as a whole. Many park administrators spoke of these communications and programs coming from the Commissioner favorably and mentioned that they had been examining their own prejudices and practices as a result of the cultural climate and resulting conversations and programs internal at NYC Parks. However, one NYC Parks employee was more critical of the conversations, appreciating their focus but wondering if they would lead to any lasting change in the agency: “From my perspective I think as a woman, as a person of color, as a New Yorker, as someone who works in a predominantly white division as a public servant in the city, it can be, incredibly challenging, but I do my best” (NYC Parks, R7). Many in the agency used this time of increased focus on racial injustice as a moment to reflect on the relationship between public land management and structural racism, beginning conversations and new programming that some saw as long overdue.

We found that NYC Parks adapted the way park rules were communicated and enforced in response to COVID-19 and BLM protests. Respondents mentioned relaxing rules and allowing New Yorkers to use parks a bit more freely during the pandemic, as it was the only space people had to get out of their houses during the lockdown. Park supervisors were looking the “other way” as small groups gathered without permits. For example, personal trainers used the park for fitness instruction, dog walkers created play spaces for canines, and sports clubs met for practice in small groups. Additionally, in response to the BLM uprisings, NYC Parks staff made efforts to maintain a safe space for protesters. As one park administrator described: “We had protests and sit-ins in the park and we obviously, we weren't accepting permits at the time, but we knew that this was going to happen and we let it happen” (NYC Parks, R9). Some of this relaxed enforcement was clearly intentional, in other cases, enforcement in parks was reduced because of staff cuts which lead to fewer NYC Parks Enforcement Patrol officers in parks. What did not come up in interviews but was reported on extensively in the media (Noor, 2020; Schweber et al., 2020) around this time was increased enforcement of social distancing rules that targeted people of color in public spaces, causing the mayor to publicly reverse orders for police enforcement of social distancing.

In response to both budget cuts and the surge in visitation, the NYC government allocated funding for the hiring of social distancing ambassadors. These positions were created and exempt from the city-wide hiring freeze to help keep New Yorkers safe in parks. In many cases these new staff were also able to help with the increased maintenance burden and take on some of the tasks of the seasonal employees who were not hired. Parks staff also shifted their regular means of reaching out to the public in this unprecedented time. NYC Parks educators and rangers shifted their usual in-park programming to virtual, developing videos and online programming, often targeted to children doing virtual school at home. Park administrators that rely on volunteer maintenance were also able to pivot and create opportunities that allowed for social distancing, such as creating distanced zones and pre-described tasks that volunteers could spread out and complete on their own in the park.

In reflecting on COVID-19 and the BLM uprisings, many NYC Parks administrators looked upon the resources they manage and their role as public servants with a newfound appreciation. The term “essential worker” became part of the public vocabulary during COVID-19, often referring to healthcare and other frontline crisis workers. In this moment, parks workers began to receive recognition as essential workers as they kept the vital green spaces open and available to the public throughout the crisis. In one case, the Empire State Building and other prominent landmarks and buildings were lit green for the night in honor of Parks workers as part of the public recognition campaign #GoingGreenForParkies There was an overall sense of pride in the ability for parks to provide a place of respite as well as a place to protest, grieve, and mourn in the wake of these twinned crises. Some expressed a hope that the intense visitation of and attention on city parks would result in a lasting change in the way New Yorkers support green space and parks.

“I really hope that when the dust settles there will be increased interest in stewardship and advocacy. If people have spent more time in parks…. maybe this is an opportunity…for a new influx of people who have a real interest in the parks and how they are maintained and taking care of them and getting involved. So, I am optimistic that that that is how that will change…in the next year and beyond.” (NYC Parks, R5)

Our summer interviews coincided with this time or reflection and dialogue for the agency. Ongoing programmatic change in response to calls for racial justice and inclusion have continued. For NYC Parks this has included programming annual Juneteenth commemorations as well as going through a citywide process of park namings and re-namings as part of a larger effort to revisit whose stories are commemorated in our public lands. Many of these efforts to address racial injustice had long been discussed and debated with partnership groups and local residents but these matters took on a new urgency, momentum, and personal meaning among NYC Parks staff as a result of the stark revelations brought about by COVID-19 and the BLM movement.

Nearly all park administrators echoed a hope to expand and deepen their partnerships. It is important to note that NYC Parks has always relied heavily on public-private partners and, since the fiscal crisis of the 1970s, park conservancies have taken hold in many of the city's largest and most prominent parks. In some cases, park managers serve hybrid roles of being both a park administrator and the executive director of a conservancy group. Partnerships for Parks, as an outreach program incubated within NYC Parks, has long worked to foster collaboration and, as appropriate, create formal agreements with communities to care for parks or different types of public parkland. These stewardship groups have proven themselves to be part of the governance network of the city's public lands (see also Connolly et al., 2013).

NYC Park's network of civic partners' have shown their ability to respond to the needs of the public quickly and agilely during this time of crisis (see, Landau et al., 2021 this issue). In response to the loss of funding and staff and increased use of public space, several parks advocacy groups formed a coalition, the Parks and Open Space Partners–NYC (POSP). The group, made up of 20 organizations, worked quickly and nimbly to summarize the financial impacts of COVID-19 on NYC's public space (Parks Open Space Partners-NYC, 2020) and mount an advocacy campaign to bring private money to hard-hit parks. In response to these organizing efforts, a coalition of national, family, and community foundations launched the NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund and distributed $3.6 million in grants to support stewardship organizations that care for NYC's parks and open spaces. The power of civic partners to organize support for public space was also evidenced in a number of virtual public forums and hearings. An October 2020 NYC city council hearing on parks and equity and a March 2021 hearing on the NYC Parks budget were attended by a number of civic partners and city officials who provided testimony urging a reversal of the budget cuts to NYC parks and support for civic partners in their work of maintaining parks and making them more accessible and equitable to all. Some of the hearings, testimony, and interviews reflected on moments of learning in past budget crisis:

“Quite frankly, we still have impacts following Sandy, but for the most part, we recovered. It took some time and it was frustrating but like New Yorkers, we came together. We had wonderful volunteers who helped us rebuild and so I think it was a good exercise, the muscles of knowing this too shall pass, like as frustrating as it is and we might have to redo and do over, but we will get through this and we have such a strong community of helpers.” (NYC Parks, R4)

In this case, NYC Parks and partners were ready to adapt to the pulse of COVID-19 and felt the call to address the press of systemic racism. All respondents tended to agree that there is more work to do in addressing both crises but, for the moment, there seems to be a true awakening to the power of partnership networks, open dialogue, and shared messaging.

The Forest Service Eastern region can be characterized as a complex landscape of regulatory frameworks and prevailing socio-cultural norms. COVID-19 created another layer of variation as land managers worked to abide by federal and state directives and adapt to local conditions. In general, land managers felt that adaptation to COVID-19 had been swift. For some, this meant adapting to decisions made at the Governor's office, revisiting work for seasonal maintenance, or shifting plans for volunteer engagement. In certain cases, COVID-19 increased the level of planning and collaboration with partners.

“In a typical year, we would meet quarterly. With COVID going on, we actually were on calls pretty much weekly every Friday. We're still coordinating and asking each other: How are you guys doing? Have you started doing this or that yet?” (Forest Service, R22)

Many managers recognized the need to immediately engage their partners and peers to ensure that they were being consistent in managing public lands across varied jurisdictions and sociocultural norms. Forest Service staff echoed pride in being able to provide free, open, and safe access to the national forests. At the same time, staff were cognizant that national forests are adjacent to other state, federal, and private lands with different jurisdictional and regulatory frameworks. Familiar with this patchwork configuration, many anticipated the need to create a more uniform approach to public access and recreational opportunities during COVID-19.

“We have great communications with a lot of our neighbors. When we met, we included all of our partners from trails, recreation and the private sector and nonprofit sector, all were represented. We really tried to be consistent wherever we could.” (Forest Service, R13)

Across all forests, staff responded to a sometimes-extreme uptick in visitation. Concern over comfort stations and trash was universal. Field workers needed to be deployed quickly but safely and only mission critical workers attending to issues of public safety were working in the office or in the field instead of teleworking from home. As visitation increased, many reflected on the challenge of thinking through a complex web of new protocols in real time, including the need for separate vehicles, field quarters, and actions that could be accomplished at a distance. As one respondent shared, “It's not so easy to shut down a national forest.” Others anxiously expressed that novice visitors to remote forest areas might put themselves and others at risk, requiring additional work for a field staff that was already feeling the strain of COVID-19 conditions. Some respondents relied on partners to send “reports back” from places that were hard to reach, overcrowded, or where trail or other maintenance was becoming an issue.

In meeting this new challenge, Forest Service employees drew upon lessons from prior disturbances including floods, fire, and storms. While the agency's well-known “Incident Command System” was not officially deployed for COVID-19, the imprint of it was present in the agency's response to this novel disturbance. At the forest level, managers reported drawing upon well-established agency procedures for assessing and managing risk, such as performing Job Hazard Analysis (JHAs) to shape workplace and field protocols. At the leadership level, the Washington Office created Operation Care and Recovery as a “one stop shop” to provide internal resources for responding to the pandemic and the 2020 wildfire season. Still, many remarked that COVID-19 was different, as this crisis was not contained to discrete areas and outbreaks continued to shift across space and time. Instead, as the season progressed, so did the steady stream of visitors who spread out across the forest terrain, clustered in popular zones. Managers observed that if visitors were able to access a steady data signal, they would often make the forest their new office or school classroom for weeks.

“We've experienced more families coming out. And younger individuals coming to the Forest, simply because they're able to. Either they lost a job or were laid off or they were able to do their work remotely as long as they could grab internet access or a phone.” (Forest Service, R19)

Not unlike their urban counterparts in NYC, Forest Service staff were, overall, excited over this influx of visitors seeking to recreate in the woods. With so many more visitors engaging in recreational activities of all kinds, staff began to speculate where there might be a rise in revenue from permit fees (e.g., fishing, hunting). One manager remarked, “Because of COVID, we [recreation] have finally been validated within the agency. In the past, it's been all about timber and fire. That's who was getting the support and now I feel that people have realized that the public is really utilizing this land and recreation is an important part of the game.” (Forest Service, R25) As one manager quipped, “You can never fully prepare for this stuff. My joke this whole time has been that two years ago we were worried about our relevancy and whether or not we were still relevant to the American public. Now I'm like, hey, we are over relevant now!” (Forest Service, R17)

With relevancy came responsibility and initially there were constant struggles with maintaining trails, toilets, and shelters. Visitor centers were often closed, and concessionaires were slow to open as they adjusted to COVID-19 protocols. The status of Youth Conservation Corps and seasonal volunteers at campgrounds and shelters, on which each forest depends, were in flux or canceled. Overall, there was an unmistakable pride in service that the agency was able to provide the public with this resource during a time of great tragedy and loss. Many were prepared to do whatever they could to extend the camping season and improve visitor experience as the forest had become a sanctuary for so many. These expressions were not devoid of concern for the cost of forest stewardship. Yet, nearly all respondents were hopeful that the Great American Outdoors Act would provide much-needed attention to the deferred maintenance of the nation's forests and grasslands.

In its long history responding to and recovering from wildland fire, the Forest Service has experienced workplace fatalities and has worked steadily to make safety part of its organizational culture. In recent years, the agency has addressed cases of gender discrimination; a series of very public sexual harassment and assault allegations were documented in a PBS news show in 2018 that news outlets reported may have contributed to the resignation of a former Chief (Baumgaertner, 2018). The Forest Service has expanded this commitment to safety to protect the public and its employees across all locations and categories of work. There is an informal motto that prevails among all levels of leadership: “safety first”. Many respondents commented on this fact and that during COVID-19, being “safe” took on new meanings in relationship to co-workers and partners. Attending to emotional needs and related support appeared to draw colleagues closer to each other.

Many approached their external partners in this way, noting that there was no “official rulebook” on how to connect at this time. As one partnership professional shared, perhaps we rely “too much on tools” and what is really needed is to find ways to adapt, improvise, and connect with each other. Often the conversation would turn toward a respondent's concern for an individual–a loyal campground host who was elderly or a dedicated local volunteer who still wanted to “get out there” and help. Managers found that “sparks of innovation” would emerge, albeit small and measured, by simply checking in with partners. These innovations might include a new way to conduct training on-line, to crowdsource ideas, or to monitor distant areas of the forest. As one manager reflected, “I think we've all learned a lot more from each other and have gotten closer, trying to figure out our way through this together.” (Forest Service, R24)

The ability to improvise in the social realm was not shared by all respondents. Many reported frustrations that much of their programming was “on pause” or their partners “went silent.” As important as it was for land managers to share stories of adaptation, it was noted that not all staff, partners, or members of the community held the same beliefs about COVID-19 or related sociopolitical issues. From those in the field, there were reports of dissent over everything from politics, to distancing protocols, to trail closures. Transboundary partnership groups became essential during the early days of COVID-19 precisely because they offered managers a trusted network of state and local partners. Many of these partnership groups were created to manage shared boundary waters or invasive pests–issues that transcend the forest boundary, but at this moment, groups were serving as a critical community response network. External partners served as a sounding board for tactics and strategies in adapting to COVID-19 and navigating the politics associated with the pandemic and racial unrest.

Nearly all land managers interviewed for this study perform roles that require them to engage with the public. Engagement might include serving as a liaison to a recreation club, coordinating corporate volunteers, shaping student field guides, or facilitating community meetings. Many of these respondents felt they had “lost the season” in terms of building social solidarity through shared field activities. Virtual meetings were an insufficient replacement for field work that might often start by “gathering around camp with a morning coffee” and setting intentions for the day. Many embraced virtual communication strategies out of a necessity to connect and expressed gratitude for technology as at least it offered them some a way to engage. For some managers, virtual technologies would help them adapt in the future.

“When I came on board our social media was just there. It was, oh, this thing happened. And we took pictures of it. Posted it. Now we've really begun to get organized and plan for it. I'm really grateful for it. How else are we going to do this work across such a large area?” (Forest Service, R16)

However, coping and adaptation strategies were slower to form in response to racial unrest. When asked about how the murder of George Floyd and related uprisings might have had an impact on their work with partners, there was a significant pause in the interview conversations. Racial injustice of this magnitude was the disturbance for which there was no unified response or incident command protocol. For some, the summer's racial unrest seemed distant from both their job and their community. A few commented that they were concerned but uncertain on how to mediate the issue, so they did not engage. This was a particularly common response in places that managers described as “not very diverse” or “almost all white.” One respondent remarked, “It really had no impact here.” However, the vast majority of respondents expressed that the murder of George Floyd, BLM protests, and a summer of racial unrest had caused profound personal and professional reflection. Some took action to create dialogues among their staff or with close colleagues. Many reflected that over the years they had witnessed overt racism toward others while in their position. Others reflected on more recent incidents where they had directly experienced racism on the job.

“Things really opened up when we had that conversation where we had multiple employees come forward and say, hey, this happened to me before. An incident happened to [a Native American Forest Service Employee] and she was coming out of a grocery store in town and somebody had made some comments and it's just very disheartening. It is so disheartening to feel that you're just not safe or welcomed, you know, for no apparent reason other than your appearance.” (Forest Service, R14)

It was as if respondents were revisiting events and their communities of practice anew and seeing them in a new light.

“I kept thinking about an incident on our forest and it was very unfortunate. We had a new [African American] deputy district ranger. He absolutely loved the [Local National Forest] employees and was very excited about his job. And this is the part that makes me sad because as I said, I was born and raised here. But he didn't feel comfortable in our community. He said that he was having some issues locally… People would say things to him, you know, holler things out of the car and stuff. After one incident, he ended up putting in for a transfer.” (Forest Service, R14)

Several respondents were grateful for the federal laws that protect individuals' freedoms on public lands as they helped them navigate “spirited encounters” with those visitors who questioned social distancing and mask mandates to prevent the spread of COVID-19 or, those who wanted to express their political views on the forest. Forest Supervisors were helpful in providing guidance, but still many expressed being left to their own judgement when the “lines became blurred” in a certain moment.

In mediating issues, managers had to know and navigate the prevailing sociocultural norms that govern a particular place to be most effective. One respondent who had recently transferred to the forest was surprised at the difference in visitor behaviors when it came to public confrontations over identity politics. She described incidents during the summer where action was taken by Forest Service personnel to remove divisive flags, noting her co-workers' surprise over witnessing so many visitor conflicts this season. Another person shared that in any given year, local groups become agitated over the rights of Tribal members to hunt and fish within the forest, noting that this year was milder than the rest with regard to racially motivated incidents.

“All that information is out there, but still a lot of people aren't aware that the Tribes actually restock this area, monitor it and help control things. Way before I got here, the National Guard had to get called in. But even this year, there was a shooting over this, and somebody was standing on shore, shooting over the heads of the guys [Tribal members] out spearing. Just trying to intimidate them and scare them off. Yeah, once a year or once every other year, we get these reports of someone shooting to intimidate and threaten.” (Forest Service, R11)

The rights of Tribal Nations–including those which include tribal lands and heritage sites–were understood but not forefront in discussions around COVID-19, vulnerabilities, and racial unrest. Numerous interviewees mentioned that similar to the Forest Service campaign around safety, the agency had just begun initiatives designed to address DEI issues prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. These initiatives include both an examination and affirmation of an inclusive agency culture (e.g., This is Who We Are; DEI trainings) as well as specific recruitment and hiring programs aimed at diversifying the composition of the Forest Service workforce (e.g., Resource Assistant Program; Generation Green; partnerships with Historically Black Colleges and Universities). The genesis of This Is Who We Are was, in part, a direct response to highly visible Forest Service incidents and misconduct involving gender issues, and it broadened over time to include other dimensions of discrimination, bias, and building an inclusive agency culture. While protesters were calling for social justice in many parts of the country, there was no pause in the message coming through the Forest Service's Work Environment Performance Office (WEPO); the Chief's Messages; and programs such as Operation Care and Recovery. A series of internal “listening sessions” were organized by WEPO, which is currently headed by a Black woman, and which centered stories of Black employees' lived experiences with discrimination and bias as a starting point for these discussions. In some cases, interviewees also noted that local sessions were also organized in the field and designed to create a space for employees to listen, share, and learn. There was clear appreciation for these efforts among respondents with many offering ideas to reshape partnerships and practice–by advocating for more inclusive hiring practices and engaging urban youth. Those who were adamant about systemic change were often near retirement, new to their position or had been assigned a role that valued diverse partnerships. While there appeared to be an overall desire for change, there was some skepticism shared by individuals or, as one respondent affirmed, by certain groups.

“I was hearing this very loudly from even some of my supervisors. They were starting to feel ashamed. If you were white, you were starting to feel like you were the problem…. So, for now, we're focusing internally. And then the next year or two or three, we're really going to start going out with it to our partners and our stakeholders to say ‘hey you know we're waving our Forest Service flag and we're proud of it. And we want you to be too.” (Forest Service, R32)

The Forest Service, as an organization, is structured to know how, when, and to what degree to respond to the pulse of natural resource disturbance. Adapting to the press of systemic inequalities and achieving the changes needed to redress racism in any agency that covers such a large and expansive social geography will take time and perseverance.

From these two cases of municipal and federal land managers, we revisited Duchek (2020)'s model of organizational resilience, with an eye to adapting this conceptual model based on these public agencies and in the context of longer-term disturbances of COVID-19 and responses to racial injustice (Figure 2). We identify organizational culture and the specific consideration of partnerships as a component of social resources as key factors important to anticipation, coping, and adaptation processes. We also propose revisiting how “during” and “after” the event are conceptualized, as here we saw evidence of both coping and adaptation occurring over months of experiencing both crises. Across these two cases and two concurrent disturbances, we identified key themes that influenced coping and adaptation actions: communications, partnerships, and organizational culture. Communications are critical to organizational resilience, but we did not situate them in the conceptual model since they occur as both flows (e.g., the arrow between social resources and partnerships and coping) and as part of processes (e.g., accepting and reflecting). Following Duchek (2020)'s model and our updated model, our empirical work also highlighted arenas where cognitive actions such as accepting and behavioral actions such as measurable change inconsistently occurred, suggesting these actions may be happening at different scales within the organizations: individuals, field managers, and leadership.

Figure 2. Revised conceptual model of organizational resilience, based on Duchek (2020) under the terms of the Creative Commons 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Bolded boxes indicate additions based on empirical cases of public land organizations during the twinned crises of COVID-19 pandemic and systemic racial injustice.

Communication is key not only in the Forest Service, but also in many other complex organizations. The ways in which the public workforce share ideas and messages is critical to how organizational change occurs in large bureaucracies (Jones et al., 2004). Change must be mediated and discussed at all levels of the organization for effective organizational shifts and transitions (Lewis, 1999). Communication across a vast network is challenging when planned and anticipated, even more so in response to an unanticipated or unfamiliar disturbance.

Indeed, communication was an active area of engagement for land managers due to the need for both virtual connection during the pandemic and spaces for reflection and dialogue about DEI. NYC Parks placed a new emphasis on employee communications and reflections, encouraging staff to engage in listening to others' concerns. Many referenced internal sessions that inspired them to think differently about themselves, their work, and their community. There already had been a movement toward this type of reflective dialogue in the Forest Service to address issues of diversity and discrimination. The pandemic created space for external communications with partners and the broader community. It may be that the vulnerabilities brought to light by COVID-19 had prompted a shift in focus to a broader range of societal issues. This shift surfaced ideas for cross-boundary partnership networks with groups that focus on issues of diversity, vulnerability, and social change.

External communications by many public land agencies are primarily driven by a directive or the need to inform. The Forest Service provides life-saving information regarding conditions and public access. COVID-19 and BLM uprisings prompted the need for communication about complex, contentious, and unpredictable matters. Managers reported paying closer attention to social media to quell misinformation or unproductive dialogues. The pandemic marked a shift in the type of communication needed to be effective and responsive. Broadening the use of communications beyond signage to include active listening, exchange, and boundary spanning activities was the most common reflection shared by respondents in either public agency.

Shifting to virtual platforms had its discontents and virtues. Virtual communications gave managers a way to reach a broader public audience, but it was not always effectively used to make meaningful direct contact with partners. Many reasoned that it was the informal conversations about life and community that had built trust between groups. At the same time, the rise of virtual platforms–including the use of anonymous fora–for listening sessions, discussion, and training on sometimes sensitive topics related to DEI was cited as creating opportunities for “unfiltered,” honest personal reflection and exchange that could lead to growth.

Social media also created a way to see how the public was using forests and parks during the pandemic. Many remarked that it was satisfying to know that public lands were appreciated by more people and were “on the radar” of the press and elected officials. Respondents noted that COVID-19 communications may have helped to expose a new generation of users to public lands. Public awareness raised hopes for new opportunities via grants, partnerships, donations, and legislative actions. The fact that public lands “belong to everyone” seemed especially cogent at this time. Land managers expressed pride in their work. Many shared examples of colleagues working in the field during the pandemic, noting the importance of their work every day and including during times of crisis.

Overall, networks, partnerships, and relationships have been theorized as key components of both adaptive capacity and social resilience at the organizational and community levels (see, e.g., Ceddia et al., 2017; Patel et al., 2017), including in particular for collaborative recreation management (Selin et al., 2020). Amid an unprecedented disturbance, we found land managers from both the Forest Service and NYC Parks were able to assess, adapt, and respond to a changing set of conditions that directly impacted the use and meaning of public lands, in part through their networks and partnerships working to amplify capacity (see, e.g., Bodin and Crona, 2009). Partnership activities were initially paused but, in nearly all cases, managers adapted and engaged with partners. In NYC, partnership networks were activated almost immediately with little or no prompting but drew upon existing networks rather than forming ad hoc ones as observed during other crises (per Weick et al., 1999). Private foundations quickly joined with civic stewardship groups in lending support through fundraising, social media, and hosting public forums in support of urban public land (see also Landau et al., 2021 this issue) Collaboration continued throughout the year including through the summer's protests over racial injustice prompted by the murder of George Floyd. NYC's park network was poised for action, as it engaged in both coping and adaptation processes.

Still, the partnership landscape of both agencies remains uneven with certain geographies having more civic capacity than others. Perhaps because NYC was an initial focal point of the pandemic in the United States, its partnership network responded with the intensity of the crisis itself. Forest Service counterparts often described their network's response to the pandemic as watchful or unsure, reflecting the uncertainty of how or when the pandemic would impact their communities. Transboundary groups seemed to offer the type of support and collaboration that the Forest Service needed for wayfinding among partnership groups and a more expansive geographic terrain. Many of these partners were able to share how their local communities were impacted and adapted to COVID-19 so that agencies could adjust their actions to be more consistent across public lands.

Comparatively, there did not appear to be the same level of transformative change in Forest Service partnership networks other than to serve as a “check in” for COVID-19 protocols, field activities, and some emotional support. While the partnership network was functional, it did not adapt and respond with the same intensity of the urban partnership network. There was no mention of new partnerships emerging in response to the summer of racial unrest. There was no clear indication that the Forest Service staff sought out, leaned on, or activated its partners over issues related to environmental justice, diversity and inclusion, or vulnerable populations. While many did not specify recommendations for future action, there was a strongly expressed desire for change. These findings add to our understanding of the transformative potential of network governance in land management (Scarlett and McKinney, 2016; Steen-Adams et al., 2020).

The complexities of addressing systemic racism and vulnerable populations presented a greater long-term challenge than the rapid adaptations to COVID-19 for land managers in NYC and throughout the Eastern Region. The most significant difference between these two organizations was that not everyone in the Forest Service network agreed on the problem and/or how to address it through partnerships and collaboration (see coping processes, Figure 2). In both cases, there was a great deal of reflection on staff composition and agency responsibility, highlighting cognitive actions that could lead to adaptation. These reflections highlighted the need to attend to the particularities of place. At the same time, there was a desire to identify ideals that could transcend place and inspire shared aspirations across the region. Forest Service staff had limited ways to grow their partnership networks, expressing that staff capacity or local conditions, particularly in rural areas, were limited in terms of financial and human resources. This inertia was a clear counter to NYC Parks' partnership network that had become a persistent driving force of resources and adaptation.

Kaufman (1960) identified the importance of both procedural and reporting techniques and line-level bureaucrats, such as the Forest Supervisor and District Ranger, in modeling and enacting organizational culture, as well as the role of details and lateral moves across geographies as pathways to promotion that create internal coherence by ensuring that staff remain connected to the central mission of the agency more than the particulars of any place or community. Since the 1960s, American society has gone through numerous transformations, including the civil rights movement, the passage of key federal environmental legislation including the National Environmental Policy Act, and changes in technologies of communication – all of which have shaped the composition of the Forest Service as well as the way in which it manages land and interfaces with the public (Tipple and Wellman, 1991; Koontz, 2007; Burton, 2012). The cultural turn influenced by the rising environmental movement alongside the shift in the American economy toward post-industrialism, lead to the rise of an “ecosystem management paradigm” in the Forest Service (Kennedy and Quigley, 1998). Examining this shift to ecosystem management, Sabatier et al. (1995) point to the role of a shared agency ideology in creating similar behavior of local Forest Service officials in the 1980s. Considering a context of compound crisis such as COVID-19 and systemic racial injustice, organizational structures and cultures–including top-down leadership (Maak et al., 2021), readiness of employees as “change recipients” (Armenakis and Harris, 2009) and the role of public service motivation (Wright et al., 2013) are key to consider when examining the potential for transformation within hierarchical, public bureaucracies.

We found that while public land management is structured to respond to disturbances that are typically related to extreme weather, visitor safety, wildlife, and wildfire, responding to the impact of COVID-19 was different in several ways for the land management community and forming a shared ideology. COVID-19 had some degree of impact on all staff and visitors that required actions to take place within households, the workplace, and broader communities. Some staff were more vulnerable than others to the pandemic. Agency response protocols were tested and changed in real time and needed to be adjusted to the local context. Coping with this disturbance required different and new expertise, suggesting this disturbance acted as a focusing event for the agencies' learning and adaptation (see Michaels et al., 2006). Still, many of the skills needed were within the scope of public land management and outdoor recreation. It was the murder of George Floyd, as a pulse within the press of systemic racism, that may have triggered a closer examination of land management in terms of who it is designed to serve, employ, and how the land itself holds meaning for different societal groups. Only time will tell whether the vulnerabilities revealed by the pandemic and the BLM protests will rewrite the cultural code that shapes organizational knowledge and practice.

From their own locational vantage points, land managers relaxed the rules a bit during the 2020 peak recreation season as they tried to navigate the social context of the pandemic and societal unrest. More visitors were allowed to press onward into wilderness areas or to use campground sites for extended stays. In NYC, parks were occupied at all hours of the night and used repeatedly as sites of protest, with or without the permits to do so. Both agencies remained flexible and adaptive to public needs despite staffing challenges in either covering vast areas of a regional forest or densely populated urban areas. It was a time of critical coping for both organizations. Organizational leadership played a key role in the response variation to racial uprisings cited by respondents in both agencies. Many reported being influenced by either their agency head, their park or forest supervisor, or a trusted colleague, supporting previous research around trust as crucial to effective management by Davenport et al. (2007). NYC Parks staff typically referred to the Parks Commissioner, a Black man, as a key influencer at this time. Staff noted the Commissioner's office offered clear direction to learn, listen, and engage with their co-workers, partners, and the community. Some Forest Service respondents pointed to the importance of having Black leaders within the agency speak up and lead, particularly in the context of the creation of the permanent WEPO office and the listening sessions it led. There was much more variation in the response by Forest Service staff. Some land managers drew inspiration and support from their Forest Supervisor and others, directly from their colleagues. Some mentioned that they felt “left in the moment” to determine a course of action for themselves as they became more aware of place-based cultural norms. From a DEI perspective, individual responses reflected a spectrum of values and beliefs that included those who might be typed as a proactive ally, a neutral agent, or a person holding counterproductive views. Several mentioned learning from prior bias incidents or participation in listening sessions as helpful to them at this time. Historically, the Forest Service has a shared ideology (see Kaufman, 1960) that typically shapes similar behavior of local Forest Service officials (Sabatier et al., 1995). However, like Lipsky's (1980) work, Sabatier et al. (1995) also points to differences within the hierarchy, with a preference to adjust directives from regional or national level offices, if they caused problems locally or conflicted with local professional judgment. Our findings signal this sort of small but substantial shift in organizational culture and affirmed the influential role of street level bureaucrats (Lipsky, 1980; Trusty and Cerveny, 2012; Moseley and Charnley, 2014) in shaping aspects of the organization from the field.

Within each agency there are different structural hierarchies and organizational subcultures within those hierarchies. Organizational hierarchies and subcultures are related to the institutional positions of each agency. NYC Parks as a city agency that directly reports to the Mayor of the City of New York who, during this time, called for direct engagement and attention to racial inequities. As an agency under the US Department of Agriculture, the Forest Service is located within the Executive Branch of the federal government. During this same period, the US President was signaling strong disinterest in such issues, eventually signing an Executive Order prohibiting the use of federal funds for DEI training addressing racial injustice and racial bias. Given this complex political landscape, the organizational trajectory that the Forest Service was moving ahead on prior to COVID-19 with regard to DEI awareness and engagements became particularly important in how to frame current actions, adaptations, and future work with staff, partners, and local communities.

In a large public bureaucracy, it can be challenging not only to “sing with one voice,” but also to find one's voice. When individuals were asked about learning from both COVID-19 and BLM uprisings, there was a resounding hope for the future that was largely unspecified in nature. This lack of specificity does not indicate a lack of vision. It suggests an understanding that there are rules that dictate the behaviors of government employees while performing their duties as well as place-based sociocultural norms. It is within the space between organizational hierarchy, subcultures, and the street level bureaucracy that adaptive strategies are formed. Although visions for the future may still be forming in the minds of many land managers, there was consensus on the need for change and that positive change had happened before. How will change be mitigated as a result of COVID-19 and the call for racial justice? What role do new partnerships have in shaping that change and the future of public land management? Perhaps, as observed in other bureaucracies, changes will happen in an ad hoc manner, but also create improvements that endure (per Newig et al., 2019).

By documenting how public land managers across the northeastern United States responded to the first 9 months of the pandemic, this study builds understanding of how adaptation can strengthen resilience to future disturbances and expands Duchek's conceptual model of organizational resilience to include organizational culture and emphasize partnerships. Understanding such efforts has implications beyond public land management, as “the resilience of a public administration…raises questions about the extent to which societies are able to purposefully reform themselves based on lessons from the past” (Duit, 2016, pg. 376). Our work builds upon scholarship that has examined stewardship of nature and social resilience in the wake of acute, chronic, natural, and human-made disturbances including September 11th, 2001, hurricanes, floods, wildfires, and pest invasions (Campbell et al., 2019) and advances our understanding of the novel, compound crises of COVID-19 and systemic racial injustice. The stressors of COVID-19 caused land managers to assess, cope, and adapt to a shifting set of conditions. Responding to a pandemic affecting human populations arguably does not align easily with the mission of public land management. Yet, urban parks and national forests became critical resources for millions of people during the pandemic. In some locations, the impact of COVID-19 was not felt strongly enough at the time to directly impact partnerships or organizational culture and in others, it has been a driving force revealing the importance of recreation and use of public lands. This raises a question of how large bureaucratic organizations can structure adaptation and change, especially when the acceptance, interpretation, and impact of the disturbance may differ depending upon organizational subcultures and uneven access to personnel, partnerships, and related social resources. In caring for the land, it may be a useful precept for natural resource agencies to anticipate and attend to integrative socio-cultural aspects, at any scale, of any given disturbance.

Across both cases, we found abiding: reports of increased public lands usership; calls for investment in maintenance; need for diversity, equity, and inclusion in both organizational settings and landscapes themselves; and the potential for strengthening workforce capacity on public lands. First, communication is key, particularly the need to foster two-way and lateral communication, including on virtual platforms. The most effective leadership has been that which has been open, honest, and reflective, while remaining focused on the core mission to support both land and people. Second, transboundary partners and polycentric environmental networks are critical for public lands management, as these relationships are useful in responding to both press and pulse disturbances. Last, COVID-19 and the BLM movement have revealed that organizations' cultures exist alongside subcultures within public land management. These subcultures are shaped by prior histories, social geographies, and leadership and have the potential to shape larger organizational culture and policies.

Understanding environmental governance during a time of cascading and compounding disturbances is challenging and we find ourselves at a crossroads. The institutional landscape will undoubtedly change as organizational culture shifts in response to greater awareness and reflection, including assessing the impact of policies and programs on issues such as social equity. In this way, actions by NYC Parks or the Forest Service in response to COVID-19 and the BLM uprisings should not be assessed as “better or worse, “but simply affirming that organizational culture is an active and important agent within these institutions. In both cases, we found processes and pathways unique to time and place but driven by organizational culture and partnership interests. For example, at the time of this research it was clear that NYC Parks responded to a dynamic and demanding social network of individuals, groups, and partners who were able to quickly establish a shared course of action in support of urban environmental governance. The reason for this successful transformation remains speculative but may suggest NYC's pre-existing density of partners, intensity of exposure to the virus in the spring of 2020, and the ensuing departmental budget cuts during a time of peak demand for public space resulted in transformative actions. Both agencies used internal adaptive mechanisms to respond to COVID-19 and the BLM uprisings while providing core services. Those who kept in virtual contact with external partners and relied on internal peer networks tended to think more reflectively about inherent social inequities regarding program and practice than those who engaged less often with new or existing partners. This observation opens the door for further inquiry into the role that partnerships and social networks play in flexibility and adaptation to compound disturbances, including complexities facing interstitial public lands along the wildland-urban interface. How can an organization become more flexible and responsive to underlying inequities and engage with new networks and coalitions, while staying on track with its abiding mission? How and when do partnerships begin to shape the organizational culture of land management agencies? Continuing to observe public agencies as they adapt to these and future disturbances in an increasingly unstable world (Harrison and Williams, 2016) offers an opportunity to empirically understand and possibly anticipate future adaptation and response.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Rutgers University Institutional Review Board. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

ES co-led the conceptualization of the research question and study design, co-led Forest Service interviews, participated in coding and analysis, and led the Forest Service case, discussion, and conclusion. LC co-led the conceptualization of the research question and study design, participated in interviews, co-led coding and analysis, and led the introduction and literature review. SP led NYC Parks and Forest Service interviews and participated in coding and analysis, and led the NYC Parks case. MJ participated in conceptualization of the research question and study design and participated in interviews, coding and analysis, and led the conceptual diagram revision and framing within the literature. All authors participated equally in writing.

The USDA Forest Service provided support for this research.