- Faculty of Human Geography and Planning Adam Mickiewicz University Poznañ, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poznań, Poland

The scale and dynamics of socio-economic and spatial processes in Poland in the last three decades, including territorial diversification of the pace of economic development and demographic and social changes, as well as processes such as metropolisation and suburbanization, determine new challenges in the management and programming of the development of large cities and their areas functional. The new processes require state and local authorities to take actions in the strictly political, legal and organizational and planning dimensions. In Poland, for almost 20 years, there has been a discussion on the introduction of specific forms of management of metropolitan areas. Failure to adopt systemic solutions at the level of the entire country (lack of political will for metropolitan reform and the creation of metropolitan self-government county) leads to the emergence of numerous grassroots integration initiatives of local governments (metropolitan associations of cities and municipalities). Since 2015, the EU cohesion policy instrument Integrated Territorial Investments has been implemented in functional urban areas. Since 2017, the first multi-task metropolitan union (Metropolitan Union of Upper Silesia—Górnoślasko-Zagłebiowska Metropolis) established by the parliament (special act) and the government (executive regulation) has been operating in Poland. The first—sui generis—statutory metropolis encourages local authorities of other metropolitan areas to adopt their own legislative initiatives (Kraków, Łódz, Tricity: Gdańsk-Gdynia-Sopot). Is the choice of the path for creating individual statutory solutions for each of the Polish metropolises in the form of a metropolitan union appropriate? Does diferrentia specifica for various metropolitan areas seem to be the most justified at the moment, taking into account the political conditions and the bottom-up and top-down approach to metropolitan governance in Poland? The article presents the complex path to solving the issue of management in Polish metropolitan areas and assesses the legitimacy of a solution based on a model tailored to each metropolis, introduced by a separate metropolitan act.

Introduction

The scale and dynamics of socio-economic and spatial processes, including territorial diversification of the pace of economic development and demographic changes, as well as processes such as globalization and metropolisation, pose new challenges for the management and programming of the development of large cities and their functional areas. The description of the increasingly functionally complex settlement systems of large cities begins to include the concept of the metropolitan area, identified not only in morphological, but above all in functional terms. The OECD defines metropolitan areas as functional urban areas of at least 500,000 inhabitants. The authors of The OECD Metropolitan Governance Survey Report (Ahrend et al., 2014) indicate that there are 275 such areas in OECD states, the largest number of which can be found in Europe (101) and in the United States (68). In Poland there are 10 metropolitan areas of this type (Warszawa, Kraków, Łódz, TriCity; Gdańsk-Gdynia-Sopot, Wrocław, Szczecin, Poznań, Bydgoszcz-Toruń, Szczecin, and Lublin).

In most highly developed countries, regardless of their political and administrative system, metropolitan governance, in various legal forms, is becoming increasingly common. According to the above OECD report, 178 of the 263 metropolitan areas analyzed (68%) have metropolitan-level governance bodies/institutions. The first wave of metropolitan reforms (mainly in Europe) took place as early as the 1960s and early 1970s yet subsided in the 1980s. In the 1990s, the number of governance actors in metropolitan areas worldwide started to rise again and reached its highest level in the last few years (Kaczmarek and Mikuła, 2007; Ahrend et al., 2014).

In comparison with many European countries with established forms of metropolitan areas governance (e.g., Germany, France, Italy), Poland is at the beginning of the road to making metropolises major entities of management and planning. This delay is due to historical conditions such as late entry into the suburbanisation phase, the relatively short time of operation of local self-government (since 1990) as well as legal, administrative and political factors. As Izdebski (2010) notes, the three-tier administrative division (commune [gmina], district [powiat- poviat] and region [województwo—voivodeship]), in operation in Poland since 1998, does not correspond to the solutions adopted by the developed countries, based on the polarization-diffusion model of development1. In this model, a special development role is assigned to urban areas, in particular to metropolitan areas. As places of concentration of the development potential, they should by their very nature perform selected regional functions. Undoubtedly, the needs for coordination of actions in urban functional areas are most often realized only with the development of negative phenomena, growing demographic and economic problems (“shrinking” of central cities), as well as transport and ecological issues. Intensive suburbanisation processes became the reality for Polish cities, especially after 2004, along with liberalization of spatial planning (The new act on planning and spatial development from 2003), rapid development of individual car ownership, new trends in housing, and an influx of investments into the suburban zones of large cities (in connection with the accession to the EU).

It is no surprise, therefore, that a debate on the introduction of specific forms of governance for metropolitan areas has been ongoing in Poland for almost 20 years. The lack of political will for metropolitan reform and the abandonment of systemic solutions at a national level (the creation of a metropolitan self-government) have led to the emergence of numerous grass-roots initiatives to integrate local authorities (metropolitan associations of towns and communes).

Governance of metropolitan areas has gained particular importance in recent years, after the emergence of new European Union regional policy instruments. The enhancement of measures for territorial coordination of intervention and management in functional areas in the EU financial perspective 2014–2020 manifested itself in the establishment of a new EU cohesion policy tool within the Common Strategic Framework: Integrated Territorial Investments (ITI). Functional areas of large cities are a natural field for ITI support; it is in large cities that burgeoning development problems are often accompanied by a deficit of intercommunal cooperation. The ITI instrument supports urban functional areas of large cities in countries such as Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia (Biniek et al., 2016). Since 2015, Poland has been implementing the EU cohesion policy instrument known as Integrated Territorial Investments in urban functional areas of regional capitals. Poland's first multi-purpose metropolitan association, i.e., the Górnoślaska-Zagłebiowska Metropolis (GZM), established by Polish Parliament (special law) and the government (executive order), has been in operation since 2017. This first de iure metropolis has prompted the local authorities of other metropolitan areas (Poznań, Kraków, Łódz, Wrocław, Gdańsk-Gdynia-Sopot) to submit their own legislative initiatives in 2018–2020. So far, proposals to establish metropolitan unions for other cities have not received the support of the central authorities and a solution to the question of metropolitan governance in Poland has not been forthcoming. Discussions on reforming the management of functional areas of large cities (so-called metropolitan reform) in Poland are currently seen as a priority by neither the government nor Parliament. Despite the launch of organizational and financial instruments to support the cooperation of self-governments in functional areas (ITI), the need for legislative changes offering metropolitan areas a special status, sources of income and specific competencies must still be borne in mind.

The aim of this paper is to present the premises and the degree of development of integrated management forms in metropolitan areas in Poland and to propose an institutional solution in the form of a metropolitan union. This work attempts to answer the following questions:

1. Is the EU ITI instrument a sufficient way of solving the key development problems of metropolitan areas in Poland?

2. Does the formula of a voluntary metropolitan union (diferrentia specifica) for various metropolitan areas in Polish conditions seem a valid model for managing a metropolitan area?

3. How can the implementation of metropolitan reform, statutory solutions in the form of a metropolitan union for each of the Polish metropolises proceed, given the political conditions and the reconciliation of bottom-up and top-down approaches to metropolitan governance in Poland?

The paper presents the tortuous path to solving the issue of governance in Polish metropolitan areas and assesses the validity of the solution based on a model tailored to each metropolis and introduced by a separate metropolitan law. So far, this model has been implemented in countries with a federal system, such as Germany. The path toward a statutory solution to the metropolitan problem presented here draws on the experience of other countries, such as Italy and France, where metropolitan reform is both discussed and implemented. The main sources of information in this paper are legal acts, reports, academic articles on the solutions to metropolitan governance in Poland, as well as data on the rate of population development in metropolitan areas. The analysis of the above data and information constitutes the basis for the formulation of conclusions and the author's proposal for solving the issue of metropolitan governance in Poland2.

Metropolitan Areas in Poland—Development Problems as a Challenge for Governance

Terms such as a metropolis, a metropolitan area and metropolisation are increasingly commonly used to describe contemporary urbanization processes, taking place also in Poland. Metropolitan issues are related to:

1. growth of the social and economic importance of the largest Polish cities, where metropolitan functions and interfaces related mainly to the globalization of the economy have begun to develop,

2. dynamic spatial development exceeding administrative borders due to spontaneous urban sprawl processes.

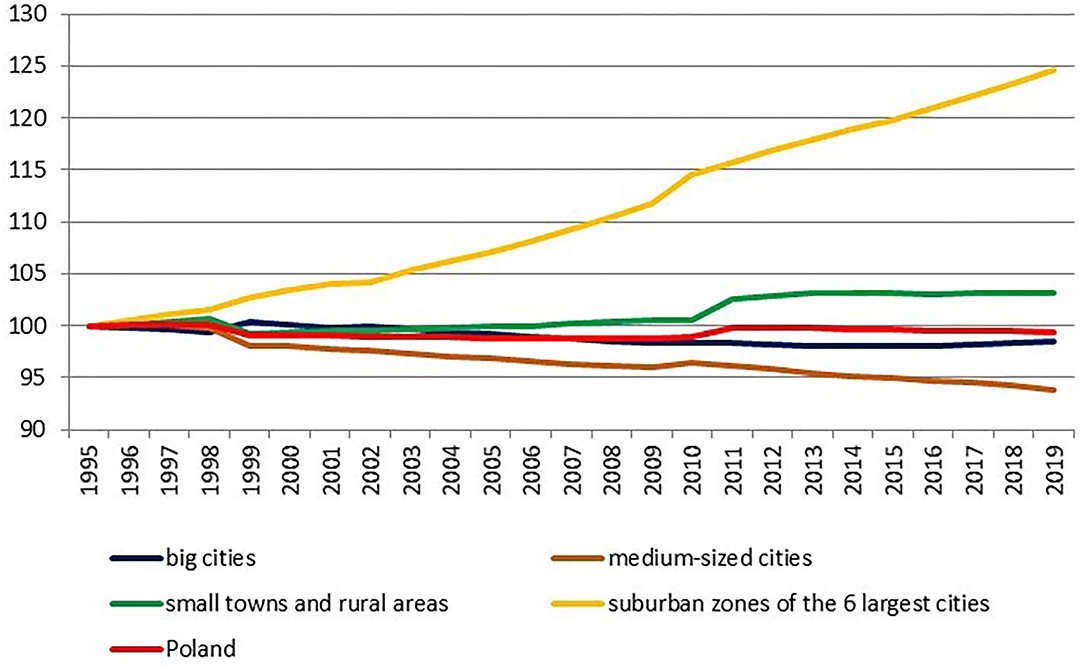

The Polish settlement system after political transformation in 1990 has been very intense. The marketization and globalization of the economy affected the settlement subsystems in various ways, differentiating the development of metropolises, medium-sized towns, small towns, and rural areas (see Figure 1). Metropolitan areas, especially their suburban areas, develop the most dynamically. However, the population of large cities within their administrative boundaries is stagnating or declining (in some cases—quite dramatically).

Figure 1. Population changes in the settlement subsystems of Poland in 1995–2019. Authors' elaboration based on data Central Statistical Office [GUS].

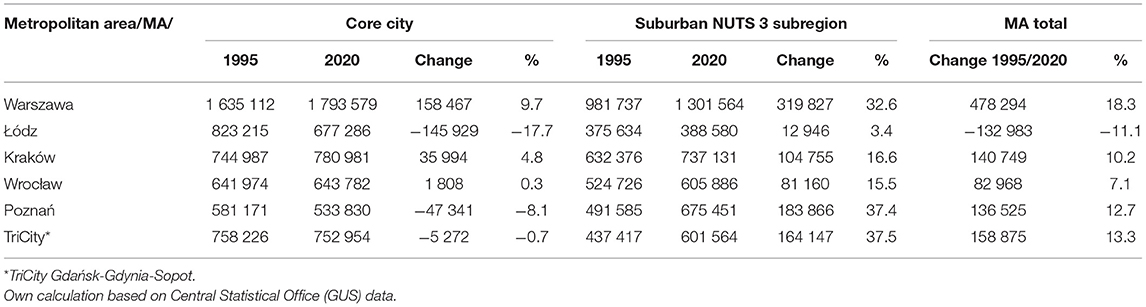

Large cities and metropolitan areas can be clearly divided into three groups according to their functional rank and development dynamics. The first one is Warszawa itself—the definite leader of the urban system in Poland and the only city with highly developed functions on an international scale (Korcelli-Olejniczak and Korcelli, 2015). The second group consists of dynamic centers such as Kraków, Wrocław, Poznań and Gdańsk (TriCity), characterized by a high pace of economic development and strong suburbanization pressure. These two groups together (“Big Five”) concentrate very high investment and construction activity. With regard to these metropolitan areas, the state's development policy should focus primarily on creating an appropriate legal, financial and political framework for the integrated management of spatial and economic development. Due to the high level of development dynamics, these areas need not so much external impulses to stimulate development, but greater autonomy of management and financing, if they are to continue to function as engines of the country's growth. However, the challenge is to achieve spatial and social cohesion in each of these areas in this process. The third group of large cities and metropolitan areas looks slightly different, lagging behind the leaders in terms of development dynamics, mainly due to their industrial past (Łódz, Katowice and Upper Silesia), peripheral location (Szczecin) or insufficiently developed higher order functions (Bydgoszcz, Lublin, Białystok). The structure of investment activity divided into peripheries (weakly developed semi-rural areas yet within the limits of the central city) and the suburban zone (communes adjacent to the central city, with separate administrative and planning jurisdiction) varied from city to city and was in particular linked to the size and nature of the stock of undeveloped areas incorporated into the city limits during the socialist period. Cities which had such reserves were able to maintain a large part of their housing investments within their borders (e.g., Warsaw), while in other cases (e.g., Poznań, Gdańsk) the main investments have shifted to suburban municipalities, with a very strong impact on the decrease in the total number of inhabitants of the central city (Table 1).

The scale and dynamics of suburbanization, as well as the extent to which the self-government authorities' control over this process was limited, exceeded expectations of the time and surprised the authorities (Mikuła, 2019). Dysfunctions of post-transformation spatial development of metropolitan areas, characteristic of most of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (The Post-Socialist City, 2007), which began to manifest themselves in conditions of uncoordinated growth of new housing areas, often without adequate infrastructure and vehicular traffic congestion and pressure on the natural environment, have gradually begun to raise awareness of the need for spatial planning and management on a supra-local scale. The development of a new formula for the coordination of planning and governance at the metropolitan level proved to be a long and still ongoing process.

Metropolitan Areas as the Subject of the Central Policy in Poland

The inclusion of metropolitan areas to the Polish development policy took place together with the adoption of the National Regional Development Strategy (NRDS) in 2010. It establishes strategic intervention areas (SIA) with the highest capacity to create economic growth and generate competitive advantages as the main recipient of a regional policy. These are mainly the largest cities from which development processes are supposed to spread (NRDS, 2010, p. 73). A document which gave the geographical and planning dimension to SIA at the national level is National Spatial Development Concept 2030 (NSDC 2030) (2011). According to NSDC 2030, “urban functional areas as spatially continuous settlement system consisting of units separate in administrative terms. An urban functional area covers a compact urban area with a functionally linked urbanized zone. Those administrative areas may include urban communes, rural communes and urban-rural communes” (p. 187). Four basic types of FUAs have been distinguished based on their sizes. It has been underlined at the same time that the functional areas of voivodeship centers play a key role in the socio-economic development of the country. These provisions are implemented into the Polish legal system in 2014 by the amendment of the Spatial Planning and Management Act according to which functional urban areas include the city which is the seat of voivodeship authorities or a voivode and its closest, functionally linked surroundings (Article 2, Section 6b). The position of the cities and their functional areas in the Polish legal system has been consolidated with the adoption of the National Urban Policy in 2015 defined as “a targeted, territorially directed action of the country for the sustainable development of cities and their functional areas and the use of their potential in the country's development processes.”

Despite introducing entities such as functional urban areas to the provisions of national development policies, the management of these areas was not a priority for the subsequent governments in Poland. In the case of Poland, a country with little experience in integrated territorial management and self-government cooperation, the recommendations included in the OECD overview of the National Urban Policy in Poland (2011) were of crucial importance for working out management principles. It was emphasized that it was necessary to prepare a new generation reform of public multi-level governance and also to strengthen the cooperation of local government units, both vertical and horizontal.

In the last years, works on several draft bills introducing new forms of the cooperation of self-government units have been conducted, especially concerning functional areas of large cities. Their purpose was to achieve socio-economic and spatial cohesion and to create the basis for the effective and integrated management of metropolitan areas. An inner system of the metropolitan area was to resemble in general terms the rules of an inter-commune multi-task union. As stated in the White Paper of Metropolitan Areas (2013) “imposing the solution for the whole country by a top-down reform would not be an effective solution because it would be based on generalizations which might not reflect the real needs of Polish cities.” In the light of no political consensus regarding a legal regulation of the status of metropolitan areas, the last year's policy of the government was reduced to the financial support of bottom-up integration forms in functional urban areas. As stated in the White Paper … (op. cit.) “A bottom-up management integration supported by financial incentives will start the solutions whose dynamics and direction will depend on the local authorities within metropolitan areas.” In order to prepare functional urban areas (including metropolitan ones) to the absorption of EU funds, and most of all to promote and program their integrated development, the Ministry of Regional Development in 2012–2013 organized a special fund for them under the Operational Programme Technical Assistance (OP TA). It included grants (awarded via a competition procedure) for the activities supporting local government units in terms of planning and the development of functional urban areas. The main concern that appears during the implementation of such competitions is related to the instrumentalization of partnership and creation of business cooperation dependent on specific projects and the possibility to obtain financial means in this regard (see Raport o Stanie Polskich Miast 2017). Several dozens of functional urban areas used the OP TA, including all metropolitan ones which have worked out various programme documents requiring cooperation and arrangements, such as development strategies (e.g., the metropolitan areas of Łódz and Warsaw) or the conceptions or studies of spatial development (e.g., the Poznań Metropolis, the Wrocław Functional Area). Regardless of their conditions-dependent nature, many of such studies have become the basis for the initiation of further, substantial and planned cooperation. Since 2015 the EU structural funds in the form of a new tool of Integrated Territorial Investments have become the main financial source of functional urban areas.

In the process of solving the metropolitan problem, profound changes on the Polish political scene were of key importance. The national programming documents discussed above were related to the ruling parties until 2015, with the liberal civic platform at the forefront. Since 2016, and the takeover of rule by the conservative Law and Justice party, the issues of large cities, managed by representatives of opposition parties, have definitely been relegated to the background of the development policy. The concept of spatial development of the country, although it set the directions for development until 2030, was abolished in 2020. In the new Strategy for The Regional Development of the Country until 2030, the functional areas of large cities are treated marginally, the term metropolitan area is avoided in it, and strategic intervention is they mainly concern medium-sized cities that lose their socio-economic functions and peripheral rural areas3.

It is worth noting that the outgoing government at the last session of the Polish parliament on October 9, 2015, before it lost power, adopted the Metropolitan Union Act (commonly known as “the Metropolitan Act”). The act provided for the establishment of metropolitan unions in all metropolitan areas with more than 500,000 inhabitants. They were to have their own authorities, representing local units of the metropolitan area, their own sources of financing—participation in taxes on the income of the population and tasks in the field of spatial planning, public transport integration, road management, creating your own development strategy and promotion.

Due to political changes, The Metropolitan Union Act as a solution for all largest Polish cities was not implemented. In return, the new government announced the creation of “tailor-made legal solutions” for individual metropolitan associations. So far this solution has been applied in the Metropolitan Union in the Slaskie Voivodeship, established on July 1, 2017. The adoption of the metropolitan law for the Upper Silesian (GZM) conurbation was followed by legislative initiatives of the authorities of other Polish metropolises. With the support of MPs, in particular of the opposition, draft laws successively submitted to Parliament included:

- MPs' draft law on the Poznań Metropolitan Union, 2017.

- MPs' draft law on the Krakow Metropolitan Union, 2018.

- MPs' draft law on the Wrocław Metropolitan Union, 2018.

- Senate draft law on the Łódz Metropolitan Union, 2020.

- Senate draft law on the Metropolitan Union in Pomorskie Region, 2020.

However, these initiatives have been consistently blocked by the parliamentary majority, which represents the ruling coalition. The main reason is the reluctance of the authorities to strengthen the role of large cities, governed by representatives of opposition parties.

Forms of Bottom-Up Cooperation in Metropolitan Areas and Its Supporting From UE-Level

With the emergence of discussions on the status of metropolitan areas and the failure of the top-down creation of metropolitan structures, local government units began to emerge in Poland, based on voluntary cooperation of municipal and poviat level units.

Since 1990, self-government legislation in Poland has provided the legal basis for inter-commune cooperation and since 2015, for commune-poviat cooperation, and enables local governments to make autonomous decisions regarding this case. Since ~10 years, we have been observing the bottom-up process of building local coalitions of cities and the communes and poviats surrounding them, which can be defined as the beginnings of the integration management process and planning in functional urban areas. Various less formal structures (councils, partnership agreements) appeared especially in the influence zones of large cities (metropolises) and more formal (companies with the participation of local governments, municipal unions, associations) for the purpose of solving common problems and coordinating management in metropolitan areas. The following are the most advanced ones (the foundation year in brackets): the Association of the Szczecin Metropolitan Area (2005), the Upper Silesian Metropolitan Union “Silesia” (2007) and the Poznań Metropolis Association (2011, the former Poznań Agglomeration Council, 2007). In the last two cases, the basis for cooperation in the form of a development strategy, which has been implemented for several years (Silesia since 2010, the Poznań Metropolis since 2011), was even created. In most of the functional areas, however, cooperation was less advanced or less institutionalized (e.g., Opole, Białystok, Łódz, Lublin). In some functional areas, for many years there was strong competition between local governments, and their main city authorities adopted antagonistic attitudes to one another (Gdańsk-Gdynia and Bydgoszcz-Toruń) or, as in the case of Rzeszów, a core city and neighboring communes4.

Strengthening of mechanisms for territorial coordination of intervention and management in functional areas in the current perspective manifests itself by the establishment of a new EU tool of the cohesion policy such as Integrated Territorial Investments (ITI) under the Common Strategic Network. In a broader perspective, according to the European Parliament recommendations, the ITI implementation is going to strengthen the cooperation of different administrative units (EC 2014). What is interestingly, not all countries use this tool (e.g., Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Spain) and those using it, employ it in different areas (e.g., Biniek et al., 2016; Kurowska and Lackowska, 2016). The natural areas of the ITI support are functional urban (first of all metropolitan/areas where, as has already been mentioned, development problems are often accompanied by the lack of inter-municipal cooperation. The ITI instrument supports functional areas in such countries like Poland, the Czech Republic or Slovakia, whereas in Great Britain, Belgium or in Germany it is applied only in selected regions (England and Scotland, Brussels-Capital Region and Flanders, Baden-Württemberg and Schleswig-Holstein).

The legal basis for the ITI implementation at the EU level is established by three Resolutions of the European Parliament and the EU Council of December 17, 2013, i.e., no. 1303/2013 (Article 36), no. 1301/2013 (Article 7) and no 1304/2013 (Article 12). In Poland, the determinants of the ITI implementation are included in the Partnership Agreement (2014), the provisions of which have been transferred to the national legal system in the so-called Implementation Act. Thus, in the case of the ITI instrument, EU states and the regions governing operational programmes specify the EU top-down regulations (so-called double top-down regulations, see for more details: Kurowska and Lackowska 2016). Due to the fact that local units (cities and communes situated in functional areas) are the ITI receivers, in this case we are dealing with territorial governance.

The ITI is supposed to encourage the development of urban territories and their functional areas by promoting the cooperation of their constitutive administrative units, the implementation of common inter-sectoral, integrated projects meeting comprehensively the needs and problems of a given functional area whose range exceeds administrative borders and covers neighboring units. The support for these areas is to be programmed by an integrated, inter-sectoral territorial strategy—the ITI Strategy (an ex-ante condition to the ITI activation) or other strategies or territorial pacts. The actions indicated in a strategy are implemented in the form of project bundles financed from several priority axes and operational programmes; one project can be jointly financed from various funds (ERDF, ESF and Cohesion Fund). Formalized partnerships for local government units—the ITI unions having little power over the task delegation within the Regional Operational Programmes (ROP) allocation management—are responsible for the ITI implementation. The establishment of a non-institutionalized partnership form, so-called the ITI Union, has become a sine qua non-condition for the ITI implementation by local governments. Inter-commune or commune-poviat municipal unions, associations and agreements of local government units have become the legal forms of the partnership. According the national guidelines (Principles of Accommodating the Urban Dimension of the EU's Cohesion Policy including Integrated Territorial Investments, 2013), ITIs are obligatory implemented in the FUA of voivodeship centers and in accordance with the decision of voivodeship authorities—in regional and sub-regional centers (Kaczmarek and Kociuba, 2017).

As Kurowska and Lackowska (2016) notice, a top-down initiative of cooperation did not contribute much to any form of closer cooperation. A top-down cooperation order “did not encounter strong resistance, yet it did not change the way people think about cooperation at the metropolitan scale” (op. cit., p. 96). Relatively frequent criticism of the ITI strategy is also indicative of that. Critics draw attention to the tendency of recording numerous, but not interrelated projects of the local scale of influence in this document, which opposes the ITI concept. Janas, Jarczewski (Raport o Stanie Polskich Miast 2017, p. 22) are even more critical, stating that “most local intergovernmental partnerships in Poland operating in functional urban areas were formed on the principle that projects create partnerships. However, it should be the other way around—partnerships should activate projects.” In the case of ITI unions, one can distinguish partnerships operating for many years and established for strategic objectives (cooperation model) and those not created on the basis of the previous experience of long-term cooperation where the absorption of the EU funds has become a main incentive for cooperation (Kaczmarek and Kociuba, 2017; Kuć-Czajkowska, 2019).

In the literature on the territorial partnership the dependence of durability and the effectiveness of self-government cooperation of their previous experience is often emphasized (Heinelt and Kübler, 2005; Kaczmarek and Mikuła, 2007; Heinelt et al., 2011). The success of the ITI instrument implementation should be attributed not only to its financial impact, but also to the tradition of cooperation and the development of long-term cooperation forms. As noticed in the analysis of the dependence of ITI structures (a range and legal formula) on previously existing cooperation forms, top-down adaptation pressure played a less significant role in the case of the cooperation tradition. Then, the conception of “path-dependency” is clearly indicated, upon which a variety of decisions and development directions are the result of “historical institutionalism,” i.e., former events and decisions (Kurowska and Lackowska, 2016). Thus, it is worth noting that for some functional areas the ITI instrument has become an incentive to create formal structures and cooperation programmes. But then, for the local governments which have already been on the defined integration path of governance, ITIs have become only an additional element, basically strengthening their cooperation in programming and finances.

Taking into consideration the factors that are catalysts of actions of local governments, one can distinguish at least two “paths” leading to more advanced management forms in functional areas. The first path (“from the top”) presents the establishment of cooperation in accordance with the top-down procedure by the necessity to redefine the ITI territorial union: its area (delimitation), organization (legal form) and programme (strategy). A model integration path of the “bottom-up” management seems to be more durable and effective. Here, in the face of new development problems, the cooperation aiming at their solution starts much earlier before the ITI instrument appears. In these functional areas in which local government units have cooperated for years, the adaptation process to the EU's new territorial policy is generally easier. It is possible to achieve a consensus faster while establishing common projects within the ITI strategy, whose principles can be based on previous programming documents, and also to develop a joint approach to the borders of functional urban areas where the ITI strategy will be implemented. It is clear that it is still too early to evaluate the results of ITI programs in Poland. An optimistic diagnosis may also be such that even an instrumental approach to ITI can be a stable impulse for further cooperation between local governments in metropolitan areas.

A Solution to the Metropolitan Question—Discussion

Despite the creation of organizational and financial instruments supporting the cooperation of self-governments in functional areas (Integrated Territorial Investments), there is a continued need for legislative changes which would offer metropolitan areas a special status, sources of income and remit. According to the authors of the OECD Urban Policy Reviews Poland. (2011), even in the face of successful joint grassroots activities in metropolitan areas, it is still necessary to develop legal platforms for inter-communal cooperation in Poland, thanks to which cities, communes and poviats could apply joint solutions to problems of social, economic and spatial development. This is the context for considering a possible scope of metropolitan reform in Poland. With reference to national specificities and European experience, it may take two paths:

1. Creation of another level of territorial administration, by giving metropolitan areas a special status of a local government unit (metropolitan poviat). It would be viable to set up these units on the basis of the existing administrative division and to flatten the commune and county structures, in the case of a circular county (the model of the Hanover Region), in the case of several counties bordering a city—the model of the Città metropolitana (where a metropolitan area replaces a province) or Metropole de Lyon (where it takes over the competences of a department).

2. Establishment of a legally regulated (statutory) territorial corporation of the city with its surrounding areas to perform shared tasks (Górnoślasko-Zagłebiowska Metropolis model, some metropolitan unions in Germany).

The former solution, i.e., the creation of another tier of local government in Poland, does not seem feasible in the current political and social situation. It has been rejected in the course of discussions as incompatible with the Polish model of a three-tier structure of local government (commune, district and region), established in 1999. The creation of an intermediate tier of local government between commune, district and region is not supported by the government due to the fact that metropolitan and suburban communes are administered by mayors who generally represent opposition parties. The entry of large metropolitan areas into the administrative shadow is not really well-received by the cities themselves or the surrounding municipalities. Regional (voivodship) authorities are also opposed to the creation of a metropolitan tier of government with regional competences, as for them raising the profile of the metropolises would mean losing control over the cores, the most prosperous areas of the regions.

As Izdebski (2010) proposes, the reform of metropolitan area governance in Poland could consist of stages and assume a high degree of flexibility of systemic and territorial solutions for individual metropolitan areas in the country. The creation of self-governmental metropolitan associations, i.e., self-governmental corporations of a union type, each with its own unique features, should be adopted as a core intervention tool, which does not disturb the three-tier territorial division of the country and does not require a comprehensive reform of local government structures (including depriving local and regional units of their competences). This differentia specifica is related to the size of the metropolitan area, the nature of the settlement system (mono-, bi- or poly-centric), the type and intensity of functional links, the magnitude of social, economic and spatial problems, and traditions of cooperation and integration in various areas of the organization of political and socio-economic life. The metropolitan union would have a formula which has already been applied in the law on metropolitan union in the Slaskie Voivodeship.

The doctrine of Polish administrative law defines in part a metropolitan union (Szlachetko, 2020; Ofiarska and Ofiarski, 2021). Earlier literature emphasizes the generic and structural distinctiveness of a metropolitan union (e.g., in relation to an “ordinary” municipal association). The key properties of such a union are:

1. A separate legal basis defining the system and tasks of the metropolitan union

2. Statutory regulation of the association's own tasks, which are de iure own tasks

3. Additional sources of financing the association's activities, which enhances its operational capacity

4. Legally protected independence

As Ofiarska and Ofiarski (2021) note, the metropolitan union as a separate legal entity in the local government sector, should in the near future become a legal institution of much greater use. The major features of a metropolitan union should moreover include a statutory premise of a material legal nature, determining the right of communes and poviats to participate in a metropolitan union.

As regards establishing and setting up a metropolitan union, cooperation between central and local government bodies and a mechanism for social consultation should be an essential principle. A metropolitan area governance reform understood in this way should include “top down” and “bottom up” features. European experience shows that metropolitan integration is created precisely by both such measures. It is the result, and often a compromise, of different visions for metropolitan reform, both among central authorities and in terms of initiatives or expectations on the part of local communities and the political forces representing them in local authorities. In Europe, there are no uniform solutions and their strongly national or even regional character is adjusted to the systemic, political, historical, populational, and economic specificities of a given country. In countries where these visions are relatively coherent, metropolitan reforms have been successfully implemented, while in countries where these visions diverge, where there is a lack of political or social will, metropolitan governance is merely a subject of discussion and political disputes.

The metropolitan association follows from the constitutional principles of the Republic of Poland as a state based on the rule of law. The Constitution ensures the right of association to local government units. Furthermore, the metropolitan reform implements the principle of cooperation between public authorities (central and local government at various levels), the principle of subsidiarity and the principle of ability to perform public tasks. The legal regulation of a metropolitan union should be in the form of a parliamentary law. As such, it has a stronger legal basis than that of a regulation and is more democratic (parliamentary majority).

Detailed laws on metropolitan union should, in relation to a specific metropolis, regulate the following:

- Method of delimitation boundaries and the procedure for establishing a metropolitan union

- Scope of operation of the metropolitan union and the union's tasks (in particular as to the spatial planning decisions, strategic management, integration of public transport, economic development, promotion, etc., e.g., joint implementation of selected social services)

- Competencies, procedures and principles of selecting authorities of the metropolitan union, as well as principles of operation of the representative for establishing the union

- Acquisition and management of metropolitan union property

- Handling of the metropolitan union's financial management

The Mode and Scope of the Metropolitan Reform—Recommendations

According to the proposed solution, the decision on the establishment of a metropolitan union and on its boundaries remains within the remit of the Council of Ministers and Parliament, but the real influence on the choice of systemic form and territorial range of the metropolitan union should be in the hands of the local authorities interested in its establishment. In the first case, the influence of local and regional authorities on the formation of the association's systemic model (including the tasks to be performed by the association) should be ensured, while in the second case the scope of the metropolitan area should be defined through a comprehensive and multi-faceted assessment of the actual state of affairs and through the prism of statutory criteria agreed upon with local and regional authorities. It is therefore necessary to phase in the creation of a formalized metropolis, in which the communes (and also the interested poviats) of the metropolitan area work out, in the course of “bottom-up” cooperation, a systemic model of a specific union in accordance with the general framework defined in the laws on commune and poviat self-government. It is the local units that enter into cooperation in the form indicated in the current legal order in the Act on municipal self-government (inter-municipal, municipal-county union), verifying the scope of public tasks, including those whose performance would, with the consent of the local governments, be transferred to the metropolitan area level from the level of individual communes or poviats. The scope of implementation of these tasks (as well as effectiveness, efficiency, etc.) should be evaluated prior to the submission of an application for the establishment of a metropolis to the Council of Ministers, in which the model of cooperation between communes (and poviats) within the metropolitan area should be verified, and the conclusions should be included in the application or result in postponing the submission. A resolution on cooperation to establish a metropolis is adopted by the councils of the communes (and poviats) concerned; they are moreover obliged to hold local government and public consultations and to administratively monitor the entire procedure.

The justification for the proposal to establish a metropolitan association should include, in particular, an indication of the areas of cooperation between the communes (and poviats) which are to make up the metropolitan association, the functional links and the advancement of urbanization processes, as well as a description of the settlement and spatial system, taking into account social, economic and cultural ties, statistical data on the population and area of the metropolitan association, and the results of consultations with the residents of the individual communes.

State urban policy is carried out by the Council of Ministers. The body responsible for coordinating activities related to state urban policy is the minister in charge of regional development. Currently these activities are carried out by the Ministry of Regional Funds and Regional Policy. As for the implementation of the task within the structures of the territorial self-government, it is necessary to cooperate with the minister in charge of public administration, currently the Ministry of Interior and Administration, and all representations of the territorial self-government, with the Union of Polish Metropolises, and the Association of Polish Cities, as well as other self-government organizations of the local and regional level.

It is advisable to set up a joint governmental and self-governmental Task Force for Metropolitan Reform together with substantive partners. As there is already a Task Force for Functional Metropolitan and Urban Areas operating within the framework of the Joint Commission of the Government and Local Self-Government, the discussion should also take place with its involvement.

The timetable for metropolitan reform in Poland could be as follows:

1. Establishment of a joint governmental and self-governmental Task Force for Metropolitan Reform. Coordinating function: Ministry of Regional Funds and Regional Policy.

2. Diagnosis of the metropolitan issue in Poland. Justification of the reform of metropolitan governance, evaluation of the operation of the Górnoślaska-Zagłebiowska Metropolis, in existence for 4 years, and the use of its outcomes in building solutions for subsequent metropolises.

3. Establishing a framework model of a legal and administrative system of a metropolitan union for all metropolitan areas in Poland. An à la carte solution including variants/spectrum of possibilities for selecting elements of the target system (including the tasks of the union) or in the form of phasing in its implementation.

4. A metropolitan pact between the government and local self-governments of metropolitan communes and poviats, setting out the objectives of urban policy in relation to the metropolis (e.g., modeled on the metropolitan act in France—the Pacte État-Métropoles5).

5. working out legal and organizational solutions for individual metropolitan areas (draft laws) by local authorities aiming to establish a metropolitan union, in particular taking into account the nature of the settlement system (mono-, bi- and poly-centric metropolitan areas) and scales of potentials, connections and supralocal problems, delimitation of metropolitan areas depending on the uniqueness of the settlement system and the adopted scope of union tasks, for individual metropolitan unions.

6. Procedures for social consultations and voting of commune (poviat) councils on resolutions on joining the metropolitan union.

7. Drawing up final acts on metropolitan union and their adoption by the Parliament of the Republic of Poland.

8. Appropriate regulations of the Council of Ministers on the establishment of a metropolitan union.

9. Establishment of a metropolitan union.

10. Taking over the implementation of public tasks, no earlier than on 1 January of the year following the year in which the Regulation of the Council of Ministers was issued.

As already mentioned, the above stages of the “metropolitan reform” take into account two approaches: a “top down” one, working out by the government and local authorities of a common systemic framework for the metropolitan union (points 1–4 of the schedule) and a “bottom up” one, involving the selection of the metropolitan association's system, including the scope of tasks and territorial range, by the local governments interested in its establishment (points 5–6 of the schedule).

Concluding Remarks

Only a systemic solution to the problem of metropolitan governance can improve and strengthen the public policies of large urban centers and the adjacent areas. Ad hoc, ephemeral measures such as the EU Integrated Territorial Investments instrument, are dedicated to selected local government projects and does not ensure coherent governance, integration of spatial and socio-economic planning and territorial management of sensitive sectors such as transport infrastructure and organization, spatial planning, coordination of supra-local service provision. The authors of the Report on the State of Polish Cities (Raport o Stanie Polskich Miast, 2017) observe that the majority of intergovernmental partnerships in Poland within the framework of urban functional areas, were established according to the logic where projects create partnerships. However, it should be the other way round and partnerships should launch projects. In response to the question posed in the introduction to this article, it should be stated that the EU ITI instrument is insufficient to solve the key development problems of metropolitan areas in Poland. Apart from the ITI, until now there have been no government programmes supporting the integration of governance in order to make it sustainable.

Is the formula of a voluntary metropolitan union, the diferrentia specifica for various metropolitan areas in Polish conditions the appropriate model for a metropolitan area governance? It would appear that under current political conditions, including the lack of consensus on systemic solutions on a national scale, this voluntary solution should be promoted. Integration of strategic governance, coordination of spatial planning including the location of investments of a metropolitan nature, obtaining a greater influence by the local authorities concerned on infrastructure and transport organizations, as well as increasing and improving the effectiveness of supra-local service provision, require the development of metropolitan union laws dedicated to individual metropolitan areas in Poland.

The article outlines proposals for implementing the metropolitan reform, taking into account political conditions and reconciling bottom-up and top-down approaches to metropolitan governance in Poland. As noted, it requires state and local authorities to take action in both strictly political and legal terms, in a spirit of trust and partnership. For that purpose, a new urban policy of the state is necessary, which as a part of the social, economic and spatial development policy aims at creating conditions favorable for the development of cities and their vicinities and improving their governance processes, in particular by:

1. shaping a rational functional and spatial structure, in particular ensuring adequate living conditions for inhabitants and providing favorable operating conditions for entrepreneurs;

2. spatial management in a manner ensuring the improvement of spatial order, protection of cultural heritage, protection of natural resources and natural environment, more effective use of already built-up areas and prevention of building dispersion, as well as limitation of urbanization pressure on green areas, including public green areas, and natural and cultural heritage sites;

3. increasing the cohesion of the settlement system, in particular by increasing transport accessibility to large urban centers, construction of their beltways, especially on national roads, creation of integrated public transport systems on a city and metropolitan area scale, as well as technical infrastructure systems in relation to the planned urbanization areas, taking into account energy saving measures in spatial development and construction.

The numerous legislative proposals by the government, the parliament and the big polish cities themselves, are becoming part of a long history similar to the development and implementation of metropolitan reform in Italy. Tortorella and Allulli (2014) in the title of their paper “Città metropolitane. La lunga attesa” they figuratively called it “the long wait.” As in the Italian case, its end may be brought by a political shift, a change of attitude of the central authorities toward the metropolitan problem or a mature compromise and consensus between the central authorities and the authorities of large cities and their functional areas. The choice of a path to create individual statutory solutions for each of the Polish metropolises in the form of a metropolitan union should therefore be considered appropriate. Adoption of a tailor-made metropolitan association formula appears to be the most desirable and feasible. Against the background of many European countries with a long-established culture of cooperation between local government units and their interaction with the government, Poland still has little to boast about in this respect. Currently, countries such as Germany, France and Italy are in the vanguard of metropolitan governance; there the metropolitan reform is not only discussed, but also gradually implemented. Metropolitan governance in Poland should definitely tap into the experience of these countries.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The current administrative division of Poland, its genesis, changes after 1990 and problems of functioning can be found in the article by Kaczmarek (2016).

2. ^The author, as an expert of the Urban Development Institute, has drafted proposed solutions to the governance of metropolitan areas in Poland as part of the recommendations for updating the government document National Urban Policy 2030. The proposed solutions were presented at the Urban Policy Congress in Katowice on 7-8.06.2021, which gathered representatives of government and local authorities, experts, NGOs, and entrepreneurs. The update of the National Urban Policy is intended to bring it into line with the latest development priorities in Poland and international trends in urban development.

3. ^The national government's direct and short-term political interest (voters who live in peripheral regions, not in metropolitan areas, see Szczerbiak 2019) is not the only and dominant reason for stopping metropolitan policy. The attitudes to democracy, the balance of power, degree of centralization or decentralization (more Local Regional Democracy in Poland, 2019), subsidiarity, respect for diversity and several others inflict on the preferred concept of the state territorial organization and administrative division. The question of metropolitan governance is the only piece of a larger, politic jigsaw.

4. ^For example, in the case of Gdańsk and Gdynia, a sign of reluctance to cooperate was the establishment of two separate metropolitan associations around Gdańsk and Gdynia (Gdańsk Metropolitan Area Association and Metropolitan Forum NORDA). Only the ITI initiative became a catalyst for the merger of both institutions. Rzeszów, on the other hand, has been using the annexation of parts of suburban communes for 10 years as a way to solve the problem of suburbanization, often against the will of the local communities. In the last decade, the city has doubled its area.

5. ^The State-Metropolitan Area Pact in France, signed on 6 July 2016, sets out a national strategy for the development of metropolitan areas based on the integration of governance and the development of innovation (https://www.gouvernement.fr/action/les-metropoles).

References

Principles of Accommodating the Urban Dimension of the EU's Cohesion Policy including Integrated Territorial Investments (Zasady Uwzgledniania Wymiaru Miejskiego Polityki Spójności UE Wtym Realizacja Zintegrowanych Inwestycji Terytorialnych). (2013). Warszawa: Ministry of Regional Development.

White Paper of Metropolitan Areas (Biała Ksiega Obszarów Metropolitalnych). (2013). Warszawa: Ministry of Administration and Digitization.

Ahrend, R., Gamper, C., and Schumann, A. (2014). The OECD Metropolitan Governance Survey: A Quantitative Description of Governance Structures in large Urban Agglomerations. OECD Regional Development Working Papers 2014/04.

Biniek, J., Opravil, Z., Chmelar, R., and Svobodova, H. (2016). Cooperation and mutual relationships of cities and their hinterlands with regard to the operation of EU integrated development instruments. Quaestiones Geographic. 35, 59–70. doi: 10.1515/quageo-2016-0015

Heinelt, H., and Kübler, D. (Eds.). (2005). Metropolitan Governance. Capacity, Democracy and the Dynamics of Place. Routledge, London.

Heinelt, H., Razin, E, and Zimmermann, K. (Eds.). (2011). Metropolitan Governance. Different Paths in Contrasting Contexts: Germany and Israel. Frankfurt; New York, NY: Campus Verlag. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.680743

Izdebski, H. (2010). “Dwadzieścia lat samorzadu terytorialnego – potrzeba rozwiazania problemu metropolii (Twenty years of local self-government - the need to solve the problem of the metropolis),” in Metropolie. Wyzwanie polskiej polityki miejskiej, ed. R. Lutrzykowski, and R. Gawłowski. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek.

Kaczmarek, T. (2016). Administrative division of Poland – 25 years of experience during the systemic transformation. Echogeo. 35, 1–17. doi: 10.4000/echogeo.1451

Kaczmarek, T., and Kociuba, D. (2017). Models of governance in the urban functional areas. Policy lessons from the implementation of integrated territorial investments in Poland. Quaestiones Geographic. 36, 47–64. doi: 10.1515/quageo-2017-0035

Kaczmarek, T., and Mikuła, Ł. (2007). Ustroje Terytorialno-Administracyjne Obszarów Metropolitalnych w Europie (Territorial and Administrative Organisation of Metropolitan Areas in Europe). Poznań: Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

Korcelli-Olejniczak, E., and Korcelli, P. (2015). On European metropolisation scenarios and the future course of metropolitan development in Poland. Geogr. Polon. 88, 107–121. doi: 10.7163/GPol.0008

Kuć-Czajkowska, K. (2019). Obszary Funkcjonalne Miast Wojewódzkich w Polsce – Przestrzeń Współpracy i Konkurencji Samorzadów Terytorialnych (Functional Areas of Voivodeship Capital Cities in Poland - the Space of Cooperation and Competition of Local Governments). Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej.

Kurowska, J., and Lackowska, M. (2016). Metropolitalne kolory europeizacji. Instytucjonalizacja współpracy w funkcjonalnych obszarach miejskich w Polsce w świetle nowych instrumentów polityki spójności UE (Metropolitan colours of europeanization. Institutionalization of cooperation in functional urban areas in Poland in the context of new EU Cohesion Policy instruments). Studia Regionalne i Lokalne 1, 82–107. doi: 10.7366/1509499516304

Local Regional Democracy in Poland (2019). Recommendation 431 (2019)1. The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Eurpope. Available online at: https://rm.coe.int/local-and-regional-democracy-in-poland-congress-session-rapporteurs-da/168093c47e (accessed Dec 15, 2020).

Mikuła, Ł. (2019). Zarzadzanie Rozwojem Przestrzennym Obszarów Metropolitalnych w Swietle Koncepcji Miekkich Przestrzeni Planowania (Management of Spatial Development of metropolitan areas in light of the ‘soft spaces of planning' concept). Poznań: Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

NRDS (2010). National Regional Development Strategy 2010-2020 (Krajowa Strategia Rozwoju Regionalnego 2010-2020). Warszawa: Ministry of Regional Development.

Ofiarska, M., and Ofiarski, Z. (2021). Zwiazki Komunalne i Metropolitalne w Polsce (Municipal and Metropolitan Unions in Poland). Warszawa: Wolters Kluver.

Raport o Stanie Polskich Miast (2017). Zarzadzanie Obszarami Miejskimi (Report on the State of Polish Cities. The Management of Urban Areas), eds. K. Janas, and W. Jarczewski. Kraków: Obserwatorium Polityki Miejskiej Instytutu Rozwoju Miast.

Szczerbiak, A. (2019). Why Is Poland's Law and Justice Party Still So Popular? Available online at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2019/10/01/why-is-polands-law-and-justice-party-still-so-popular/ (accessed Oct 7, 2021).

Szlachetko, J. H. (2020). Normatywny Model Samorzadu Metropolitalnego (Normative Model of Metropolitan Self-Governmen). Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego.

The Post-Socialist City (2007). “Urban form and space transformations in central and Eastern Europe after socialism,” in The Post-Socialist City, Series: GeoJournal Library, ed K. Stanilov (Dordrecht: Springer).

Keywords: metropolitan area, metropolitan governance, inter-municipal cooperation, Integrated Territorial Investments, Poland

Citation: Kaczmarek T (2021) A Tailor-Made Metropolitan Union. Is This a Good Solution of the Metropolitan Governance Problem in Poland? Front. Sustain. Cities 3:724354. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2021.724354

Received: 12 June 2021; Accepted: 13 October 2021;

Published: 18 November 2021.

Edited by:

Lukasz Damurski, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, PolandReviewed by:

Maciej Tarkowski, University of Gdansk, PolandJakub Szlachetko, University of Gdansk, Poland

Copyright © 2021 Kaczmarek. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tomasz Kaczmarek, dG9ta2FjQGFtdS5lZHUucGw=

Tomasz Kaczmarek

Tomasz Kaczmarek