This journal is devoted to the issues and concerns at the intersection of three related urban debates.

Cities and Social Difference

The first is the basic proposition that cities are sites of social difference. Differences include, but are not limited to, ability status, age, class, citizenship, ethnicity, gender, race, sexual orientation, and socio-economic position. These differences are neither a biological given, nor fixed nor stable. They are social constructs that are maintained and created as well as resisted and contested. They are embraced as well as disputed. Differences in the city are not simply revealed, they are created and enacted. These differences are sites of action, social mobilization and performances acted out in private and public spaces in the city. In other words, social differences are not simple categorizations, but complex, contested sites of meaning.

Take, for example, the issue of gender. There is now a considerable body of work about how gender is maintained and created in urban settings with the result that men and women experience urban space differently. In an early contribution, Wilson (1991) argued that for too long the design of cities was driven by masculine desire to control the place of women. The regulation of urban space is still highly gendered and is used to legitimize gender oppression and regulate sexuality. Valentine (1989) for example has long described the heterosexuality of public spaces and contends that women are often constrained into the restricted use and occupation of public space. Patriarchal societies limit women's mobility in a gender partitioning of urban space. Gender roles are inscribed and transgressed, codified and undermined in cities, often under the surveillance of the male gaze.

There is the intersectionality of social differences (Cho et al., 2013; Hancock, 2016; Valentine, 2007). Social differences overlie each other from every angle from parallel to orthogonal, creating differences within differences. There are, if we carry on with gender, sometimes huge differences in the lived experience of women of different ages, body types, class, ethnicity, race, and sexual orientation. The experiences of low-income minority women in the cities of the global urban south, for example are vastly different from those of upper income white women in cities of the global north. Class, gender, and race are just some of the major social differences that intersect to undermine the singular notion of Women, or Middle class or White. Stansell (1986) provides a careful analysis of changing female identities by class in New York City. She looked at the development of working-class women as an economic social and political force to subvert previously held the ideas of the proper place of women and of women's essential nature. She shows how they created small freedoms from large oppressions.

There are many sources of social differentiation that connect and collide, intersect, and undercut each other in complex and constantly changing forms. Differences large and small intersect with other differences, also large and small to create complex social mosaic of social difference in the city. “Mosaic“ is perhaps the wrong metaphor; comprised as it is of small hard fragments. More accurately, the categories of social difference are shape shifting in space and time and not so much static categories as in a continual process of production and reproduction, imposition and resistance.

The Sustainable City

The second discourse is the notion of the city as a site of sustainability and resilience especially in the face of global climate change (Benton-Short and Short, 2014; James, 2014). Here, I draw on a previous paper (Short, 2015). Sustainability aims for an ecological equilibrium that maximizes efficiency, minimizes waste, and spends interest but not principle. In 2015, after 3 years of negotiations and debate, 193 countries agreed to adopt sustainable development goals (SDGs) that built on the success of the 2000 United Nations Millennium Development Goals and aimed to go further to end all forms of poverty. The program calls for action by all countries to promote prosperity for protecting the planet with the recognition that ending poverty must go hand in hand with strategies that build economic growth and address a range of social needs. The SDGs set an agenda for investment in advancing sustainability and focus efforts to implement the three E′s of sustainability: economy, ecology, and equity. Sustainable practices are being adopted around the world and new metrics are being developed for the Anthropocene Age as we recognize limits to the traditional economic models that because they endorse a bottom line consisting of revenues minus costs and expenses only measure a narrow range of economic costs and benefits. These traditional economic models do not recognize the full weight of external costs on the environment nor account for their impacts on the long-term sustainability of the global resource commons.

At first blush the city is an unlikely platform for sustainability. Cities house more than half the world's population; they consume 75 percent of the world's energy and emit 80 percent of the world's greenhouse gasses. But cities are not just areas of problems, they have also emerged as innovative sites for policy solutions. The concentration of population and investment means that cities are at the very heart of issues of sustainability and resilience.

The brute facts of climate change vulnerability in cities are promoting a new and more pronounced urban environmental sensitivity. Cities are responding with both mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation focuses on reducing the concentrations of greenhouse gases by using alternative energy sources, encouraging greater energy efficiency and conservation and through the promotion of carbon sinks through planting trees. Adaptation involves the remaking of cities to become more resilient to climate change.

There is a bottom-up movement from urban residents for a better quality of urban life. Global climate change issues, such as the shrinking polar ice sheets and the perilous state of polar bears are real but distant, long term and difficult to solve for the urban residents of today's megacities. But the residents have an immediate experience of poor air quality in their city and a more immediate and greater ability to leverage local policies that effect change. The global issues can seem distant yet pressing, creating a sense of anxiety without any form of immediate political response. The nation state can be both too big to deal with urban issues and too small to affect global affairs. National legislatures, such as the US Congress, whose debates are shaped more by big monied interests that the everyday needs of local citizens can too often lock into ideological disputes and paralysis. The city is often the sweet spot of climate change issues because it is small enough to connect with citizens and tailor specific policies, while large enough to affect a real difference. Cities are the ideal stage for developing policies and practices of sustainability compared to the global and the national.

Cities are nodes in a global network of flows of people, ideas, and practices. While the world is often described as separate national surfaces of nation states, it is increasingly visualized as a global urban network. Cities are learning from each other, as policies are tested in cities with the more successful ones diffused, adopted and adapted around the global network.

Many US cities have initiated environmental legislation that exceeds EPA standards, in the absence of national leadership. The C40 group is a group of the world's largest cities committed to tackling climate change to reduce carbon emissions and to increase energy efficiency. Forty cities signed up in 2006, hence the name, but more than 97 cities from around the cities are committed to the project (https://www.c40.org). There is also growing competition between cities. As the world globalizes, cities are assessed by international standards in the competition for investment, skilled people and creative industries. Cities need to respond to the demands of an increasingly mobile and ecologically aware capital and global talent pool. Cities are now ranked, compared and assessed by the greenness of their environment, and their success in moving toward more sustainable policies.

We also have much to learn from the marginal of the world's cities. In the past 60 years between 1 and 2 billion people have created self-build communities in cities all over the world. They have quite literally made their urban environments. This is not to romanticize the problems in slums. But our present environmental predicament is in large part due to an unthinking reliance on technology, the higher tech the better. The slums of the world provide an invaluable experience of creating cities with limited resources; they are in fact a living experiment in doing more with less. There are many lessons we can learn for this 60-year experiment of informal urban living.

There is a lot of bad news concerning climate change as our planet gets hotter and more vulnerable to environmental risks. But the cities of the world are where adaptation and mitigation policies are being most tried and tested. They are also a source of new jobs as the green economy and green jobs provide new alternatives to traditional occupations. The cities are both the cause of many of our environmental problems but also, as it turns out, also the solution.

The complex nature of creating a more inclusive and sustainable city is apparent in the number of different SDGS including 5, 10, 11, and 16 that respectively deal with gender, reducing inequalities, sustainable cities, and human rights. There are many overlapping issues involved in the creation of a sustainable inclusive urban future.

The Inclusive City

The third discourse is the idea of social inclusion and the city (Collins, 2003; Fainstein, 2014; Silver, 2015; Wolff, 2017). The social differences we noted earlier are mapped onto political power relations, social status and the ability to make and remake the city. The sources of difference are also scenes for the operation of power and sites of subordination. To be Black in the White City or working class in the capitalist city, or an immigrant in the xenophobic city, or a woman in a man -made city is not just a social category but to be on the wrong end of an asymmetric power relation. It is to be placed in a more marginal position that affects your life chances and your ability to shape and inform the city.

The idea of social inclusion also raises its counter, social exclusion. The emergence of the neoliberal city for example was a move toward limited government spending, reducing social subsidies, and freeing up the market from government regulation and public oversight (Hackworth, 2011; Pinson and Journel, 2017). An urban neoliberalism coalesced around an ideological core of ideas about accountability, choice competition, incentives, and performance that recast citizens as consumers prioritized capital over labor. The neoliberal city entailed a shift in political culture as residents were seen more as consumers and the poor were simply a problem.

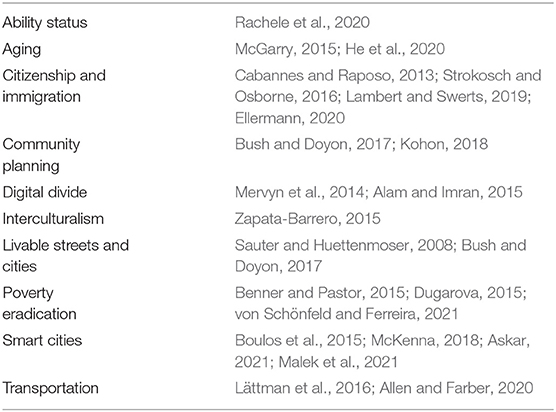

Numerous scholars have drawn attention to the fact that many ideas and practices of sustainability and resilience fail to address issues of equity, justice, and power (Fitzgibbons and Mitchell, 2019). Unless practices, politics and ideas of resilience and sustainability engage with issues of social justice then they will fail to connect resilience with equity and sustainability with social justice. We now have a large body of work that looks at the impacts of social inclusion on specific elements of urban life and urban living including. Just a sample of recent studies is noted in Table 1. It is clear from these and other studies that social inclusion has positive benefits beyond being more equitable. The more voices that are heard, the wider the bandwidth for understanding complex issues. And one thing we do know is that the smaller number of people making decisions, and especially if they are from a similar profession, caste or class then the greater the possibility of a groupthink coming up with partial, wrong and just plain dumb ideas. A polyphonic city is not only more just it is may also be more efficient.

Ideas on social inclusion in cities have been around for some time and form a recurring obsession of my work. Some time ago I wrote a book, The Humane City with the subtitled Cities as if People Matter (Short, 1989). There were specific chapters on the city as if only capital matters, the city as if only professionals matter, and cities as if only some people matter. The basic argument was that most cities are built around the needs, desires and preferences of certain groups. A more recent book looked at reasons behind the displacement of the poor and growing inequality in global cities (Short, 2018).

Social inclusion is now a dominant concern. However, three specific points about the focus on social inclusion. The first is we should be wary that, as it becomes such an encompassing term, it may gain width but lose depth. When specific terms take on feel good qualities then there is always the danger that they act as more as a form of academic signaling rather than as a useful analytical construct. Second, we need to be aware that the actual forms of social inclusion need to be scrutinized. To have community participation on a narrow range of predetermined choices is only partial inclusion. Real power exists in the ability to shape the narrative in which choices are made. Real power is a form of cognitive capture that structures what is being discussed and how. Getting poor people to decide between two alternatives presented by monied interests is participation theater not the exercise of full inclusion. Third, a more radical notion of social inclusion is raised in the idea of the right to the city. The urban theorist Henri Lefebvre outlined a right to the city that involved the freedom to collectively make and remake the city for everyday human needs rather than reflecting the logic of capital or the dictates of the state (Levebvre, 1996, 2003). The right to the city, in his conception, was the right to access, use and enjoy the city and fully participate in the production of urban space. It involved two specific rights, the right to participation and the right to appropriation. A right to the city along these lines involves also a deeper restructuring of social relations (Harvey, 2012; Hintjens and Kurian, 2019).

The Grand Challenge

Ultimately social inclusion is about marrying ideas of fair and equitable cities with green and green and resilient cities. Ideas of social inclusion need to be central to climate change adaptation and mitigation in order to make the green city also the just city. The Journal looks forward to publishing the work of scholars and professionals trying to capture the attempts, practices and implications of producing such a fair green and inclusive city.

This section welcomes contributions that investigate the distributional effects and the impacts on different population groups. The mission of the journal is to host innovative research that shapes the crucial interaction between sustainability and social inclusion across cities in the global North and the global South. Areas covered by this section, but not limited to:

How social differences are created and contested.

How formal and informal sectors are treated as sites of sustainability.

What social differences- such as age, gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, citizenship, immigration status, class, (dis) ability etc.- are embodied in ideas and practices of sustainability.

How urban policies reinforce, undermine, and highlight social differences.

How cities generate and overturn the social inclusion and exclusion of different type of groups through promoting sustainability.

How sustainability can be heightened with more inclusive practices.

The changing social inclusion/exclusion of different groups.

The redistributional consequences of sustainability.

How the right to the city is expressed through policies of sustainability and resilience.

The role of participatory theater in sustainability policies and practices.

The lack of social inclusion in policies of sustainability and resilience.

How sustainability policies produce different outcomes from different social groups in the city.

How social difference in the city is reinforced, undermined, contested, celebrated and eradicated by the pursuit of urban sustainability.

What groups are included and excluded in the pursuit of sustainability.

The published papers will contribute insights into the numerous and complex relationships between social difference, sustainability and the rhetoric, and practices of social inclusion and exclusion.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Alam, K., and Imran, S. (2015). The digital divide and social inclusion among refugee migrants. Inform. Technol. People 28, 344–365. doi: 10.1108/ITP-04-2014-0083

Allen, J., and Farber, S. (2020). Planning transport for social inclusion: an accessibility-activity participation approach. Transport. Res. D Transport. Environ. 78:102212. doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2019.102212

Askar, R. A. (2021). “Cultural creativity and social inclusion in creative cities: preliminary indicators,” in Handbook of Research on Creative Cities and Advanced Models for Knowledge-Based Urban Development, ed A. A. R. Galaby (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 265–283. Available online at: https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/cultural-creativity-and-social-inclusion-in-creative-cities/266643 (accessed April 1, 2021).

Benner, C., and Pastor, M. (2015). Brother, can you spare some time? Sustaining prosperity and social inclusion in America's metropolitan regions. Urban Stud. 52, 1339–1356. doi: 10.1177/0042098014549127

Benton-Short, L. M., and Short, J. R. (2014). City and Nature, 2nd Edn. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203002322

Boulos, M. N. K., Tsouros, A. D., and Holopainen, A. (2015). ‘Social, innovative and smart cities are happy and resilient': insights from the WHO EURO 2014 International Healthy Cities Conference. Int. J. Health Geogr. 14:3. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-14-3

Bush, J., and Doyon, A. (2017). “Urban green spaces in Australian cities: Social inclusion and community participation,” in State of Australian Cities Conference (City of Gold Coast). Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Judy_Bush/publication/327756077_Urban_green_spaces_in_Australian_cities_social_inclusion_and_community_participation/links/5ba2d18e92851ca9ed174198/Urban-green-spaces-in-Australian-cities-social-inclusion-and-community-participation.pdf (accessed April 1, 2021).

Cabannes, Y., and Raposo, I. (2013). Peri-urban agriculture, social inclusion of migrant population and right to the city: practices in Lisbon and London. City 17, 235–250. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2013.765652

Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. W., and McCall, L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: theory, applications, and praxis. Signs 38, 785–810. doi: 10.1086/669608

Collins, H. (2003). Discrimination, equality and social inclusion. Mod. Law Rev. 66, 16–43. doi: 10.1111/1468-2230.6601002

Dugarova, E. (2015). Social inclusion, poverty eradication and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (No. 2015-15). UNRISD Working Paper. Available online at: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/148736 (accessed April 1, 2021).

Ellermann, A. (2020). Discrimination in migration and citizenship. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 46, 2463–2479. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1561053

Fainstein, S. S. (2014). The just city. Int. J. Urban Sci. 18, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/12265934.2013.834643

Fitzgibbons, J., and Mitchell, C. L. (2019). Just urban futures? Exploring equity in “100 Resilient Cities”. World Dev. 122, 648–659. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.06.021

Hancock, A. M. (2016). Intersectionality: An Intellectual History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199370368.001.0001

He, S. Y., Thogersen, J., Cheung, Y. H. Y., and Yu, A. H. Y. (2020). Ageing in a transit-oriented city: satisfaction with transport, social inclusion and wellbeing. Transport Pol. 97, 85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.06.016

Hintjens, H., and Kurian, R. (2019). Enacting citizenship and the right to the city: towards inclusion through deepening democracy?. Soc. Incl. 7, 71–78. doi: 10.17645/si.v7i4.2654

James, P. (2014). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315765747

Kohon, J. (2018). Social inclusion in the sustainable neighborhood? Idealism of urban social sustainability theory complicated by realities of community planning practice. City Cult. Soc. 15, 14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccs.2018.08.005

Lambert, S., and Swerts, T. (2019). “ From sanctuary to welcoming cities”: negotiating the social inclusion of undocumented migrants in Liège, Belgium. Soc. Incl. 7, 90–99. doi: 10.17645/si.v7i4.2326

Lättman, K., Friman, M., and Olsson, L. E. (2016). Perceived accessibility of public transport as a potential indicator of social inclusion. Soc. Incl. 4, 36–45. doi: 10.17645/si.v4i3.481

Malek, J. A., Lim, S. B., and Yigitcanlar, T. (2021). Social inclusion indicators for building citizen-centric smart cities: a systematic literature review. Sustainability 13:376. doi: 10.3390/su13010376

McGarry, P. (2015). Local government, ageing and social inclusion: past, present and future. J. Poverty Soc. Justice 23, 71–79. doi: 10.1332/175982715X14236418723040

McKenna, H. P. (2018). “Re-conceptualizing social inclusion in the context of 21st-Century smart cities,” in Social Inclusion and Usability of ICT-enabled Services, eds J. Choudrie, S. Kurnia, and P. Tsatsou (New York, NY: Routledge), 1–18. doi: 10.4324/9781315677316-4

Mervyn, K., Simon, A., and Allen, D. K. (2014). Digital inclusion and social inclusion: a tale of two cities. Inform. Commun. Society 17, 1086–1104. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.877952

Pinson, G., and Journel, C. M., (eds.). (2017). Debating the Neoliberal City. London: Taylor and Francis.

Rachele, J. N., Wiesel, I., van Holstein, E., Feretopoulos, V., de Vries, T., Green, C., et al. (2020). Feasibility and the care-full just city: overlaps and contrasts in the views of people with disability and local government officers on social inclusion. Cities 100:102650. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2020.102650

Sauter, D, and Huettenmoser, M. (2008). Liveable streets and social inclusion. Urban Design Int. 13, 67–79. doi: 10.1057/udi.2008.15

Short, J. R. (2015). Why cities are a rare good news story in climate change. Available online at: https://theconversation.com/why-cities-are-a-rare-good-news-story-in-climate-change-45016 (accessed April 1, 2021).

Short, J. R. (2018). The Unequal City: Urban Resurgence, Displacement and the Making of Inequality in Global Cities. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315272160

Silver, H. (2015). The Contexts of Social Inclusion. Available online at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2641272 (accessed April 1, 2021).

Strokosch, K., and Osborne, S. P. (2016). Asylum seekers and the co-production of public services: understanding the implications for social inclusion and citizenship. J. Soc. Policy 45, 673–690. doi: 10.1017/S0047279416000258

Valentine, G. (2007). Theorizing and researching intersectionality: a challenge for feminist geography. Prof. Geograph. 59, 10–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9272.2007.00587.x

von Schönfeld, K. C., and Ferreira, A. (2021). Urban planning and European Innovation Policy: Achieving sustainability, social Inclusion, and economic growth? Sustainability 13:1137. doi: 10.3390/su13031137

Wolff, J. (2017). Forms of differential social inclusion. Soc. Philos. Pol. 34, 164–185. doi: 10.1017/S0265052517000085

Keywords: sustainability, equity, social inclusion, social difference, right to the city, urban sustainability, social justice

Citation: Short JR (2021) Social Inclusion in Cities. Front. Sustain. Cities 3:684572. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2021.684572

Received: 23 March 2021; Accepted: 29 March 2021;

Published: 22 April 2021.

Edited and reviewed by: Bernadette Hanlon, The Ohio State University, United States

Copyright © 2021 Short. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: John Rennie Short, jrs@umbc.edu

John Rennie Short

John Rennie Short