- Sustainable Marketing, University of Kassel, Kassel, Germany

Help, I need to get rid of it! In suburban areas of Guatemala City, inhabitants dispose of their household waste by burning it on their private property. Garbage collection coverage in the capital is inadequate, with only 85% of the generated waste being collected and collection rates in suburban areas lag far behind. This study examines the critical events, decisions and emotions linked with the disposition of household items of impoverished consumers living in the suburban area of Cumbre de San Nicolás near Guatemala City. We emphasize the determinants of their behavior, attitudes, and perceptions regarding their daily disposal routines of household possessions. The selected method to describe the poor consumers' experience in the disposition process of their household possessions is that of existential phenomenology. This analysis of 10 in-depth, semi-structured, qualitative interviews provides new insights into residents' daily disposal routines, social life, and traditions. Results show that religion, social norms, and peoples' relationships are essential for the well-being of those in suburban areas. Moreover, they significantly affect peoples' rationales and reflections on their disposal behavior and are promising factors for controlling suburban resource management of waste. This study's respondents showed a high level of awareness that on-site burning of household waste negatively affects human health and the environment. On the individual level, emotions influence the way of how people dispose of their personal belongings. Based on this study's results, we propose an intervention framework tailored to suburban impoverished citizens.

Introduction

The metropolitan area of Guatemala City is home to over 2.5 million people. As in some other capitals in the region, the authorities in Guatemala City face challenges in their attempt to provide adequate municipal solid waste (MSW) services. It is estimated that almost 80% of the Guatemalan population practices unsound disposal behavior (Waste Atlas, 2021). Open-air burning, littering, and open dumping of household waste in woods, rivers, ravines, and mountains (Hettiarachchi et al., 2018) are noticeable concerns in Guatemala as they affect human health and the natural environment. Rodic-Wiersma and Bethancourt (2012) stated that relevant drivers for the development of MSW services are public health and resource value.

MSW management faces multiple challenges with urbanization, climate change (World Bank, 2020), and population growth, adding complexity and dynamics to the issue. The concentration of urban waste requires appropriate disposal facilities, infrastructure, and transportation (Ulgiati and Zucaro, 2019). The modern urban lifestyle is resource-intensive and generates great amounts of waste. As the Guatemalan population rapidly increases, urban and suburban infrastructure has not kept up with its needs. Further problems keeping Guatemala City from sustainability are financing, insufficient separation of materials at the household level, lack of safe landfills, illegal dumping, burning, and street litter as well as limited public awareness, inadequate education on proper waste management practices and weak formal institutions (Rodic-Wiersma and Bethancourt, 2012). Ulgiati and Zucaro (2019) highlight that the community aspect and the management of the resource metabolism are still underexplored and call for a better understanding of societies, their environments, and the material flows resulting from consumption.

A constantly increasing amount of solid waste is generated in developing countries (Salem et al., 2020; Waste Atlas, 2021). On a global scale in the past decade, decreasing extreme poverty (Kaza et al., 2018) has led to increased well-being, prosperity and consequently to consumption (Cruz et al., 2015). Suburban areas in underdeveloped and developing countries are often characterized by an informal structure, deficient infrastructure, and low incomes and recycling rates (Hettiarachchi et al., 2018). The term urban describes the population and area size within a contiguous territory, including its nearby suburban sprawl. In low- and middle-income developing countries, the informal recycling sector is highly active but is often underappreciated as part of a city's solid waste and resource system (Randhawa et al., 2020). The informal recycling sector plays an important role in MSW processing because it increases a city's recycling rate.

Research on consumers' disposal behavior, considered as a natural component of the consumption cycle, has received insufficient scholarly attention (Roster, 2001; Lastovicka and Fernandez, 2005; Raab et al., 2021). Further, there is scarce empirical research intervening individuals' consumption behavior and subsequent disposal decisions in their various forms, which have been found to be frequently guided by emotions (Raab et al., 2020). (Roster, 2014, p. 323) defines disposition as “the psychological and emotional process in which owners/consumers relinquish self-ties to possessions.” Lastovicka and Fernandez (2005) describe disposal as a process with a critical stage of a detachment decision that leads to permanently getting rid of a possession. In terms of marketing, (Saunders, 2010, p. 440) highlighted the relevance of disposal a decade ago, arguing that “the analysis of disposition is as important as acquisition and consumption behavior.” Notably, Türe (2014) provided a discussion of the “value in the disposal” process that goes beyond reducing disposal practices to a set of (technical) antecedents. In this vein, precipitating events, emotions, and decisions associated with the act of disposing of products are relevant because of their effect on the disposal process (Raab et al., 2020).

This qualitative study explores the disposal behavior of poor, suburban consumers and offers insight into the actions of indigenous people and what affects their disposal behavior. We answer the following research questions:

• To what extent are poor people aware of the consequences of their household waste disposal decisions, and how do they feel about and rationalize their actions?

• What emotions, motives, and consequences are associated with poor peoples' disposal decisions?

Method

Data Sampling Context

Guatemala is one of Central America's largest economies and has experienced continued economic stability with a moderate growth rate of 3.5% on average in the past 5 years (World Bank, 2020), but poverty and inequality remain high, with indigenous people continuing to be particularly disadvantaged. Cumbre de San Nicolás belongs to the 353 km2 Municipio “Villa Canales” whose northwestern areas already belong to the agglomeration of Guatemala City. The appearance of this little community is depicted in Figure 1.

This indigenous community, where the interviews took place, is not connected to the urban MSW management services. On a household level, the daily routine of waste disposal includes burning in open holes, illegal dumping, and street littering.

Interview Procedure

To meet this study's goals, the researchers conducted 10 in-depth, open-ended interviews on disposal behaviors related to common household possessions seen as indispensable to poor consumers. The format reflected the methodology of existential-phenomenological interviewing (Thompson et al., 1989), which strives to describe experience emerging in specific contexts or in terms of how it is lived (Valle et al., 1989).

The respondents (eight females, two males) ranged from 21 to 65 years of age and lived in 10 different households with four to five people each, which represented almost 10% of all the families in Cumbre de San Nicolás. The respondents qualified to participate in the study based on their prototypical profile: indigenous, suburban residents of Guatemala who were poor, semi-educated, frequently unemployed, and had a family size of four to five persons. These study respondents were classified as the base of the pyramid (BoP) consumers. The households were carefully selected by a local contact agent living in Cumbre de San Nicolás. The interviews were conducted in 2015 by a native, Spanish-speaking member of our research team and the local contact agent.

To provide a thematic description of poor consumers' experiences of disposing of their possessions, the interviewers began by asking the participants whether they owned any of seven basic household items: pot, toothbrush, television, mattress, mobile phone, clothing, and shoes (Saunders, 2010). The choice of routine objects is crucial because we wanted to study unexceptional cases of disposition behavior (Inglis, 2005). The interview team systematically asked participants whether they had recently disposed of one or more of these items and then asked exactly how they had disposed of them. If the participants had disposed of any of these possessions, they were asked for details about preceding events, decisions, and emotions associated with disposing of the product. The semi-structured nature of the interview allowed the conversation to flow based on the participant's story.

We based the interview guidelines on the disposition taxonomy developed by Jacoby et al. (1977); previous studies by Pieters (1993), Salem et al. (2020), and Young and Wallendorf (1989) relied on this or similar taxonomies of disposition behavior. In this framework, consumers must choose from three options when deciding what to do with their obsolete possessions: (i) keep the product; (ii) permanently dispose of the product; or (iii) temporarily dispose of the product.

Results

Keeping the Product for Later Use

One of the more common reasons offered by the respondents for keeping a product for later use (mentioned nine times) was their emotional attachment to the product and their inner satisfaction, which supports Roster's conclusions (Roster, 2015). Memories and past events linked to the product reflected an emotional attachment (Salem et al., 2020) and frequently inspired a desire to keep the product for later use. “I did not want to throw it [mobile phone] away for the same reason as the pot: I had memories connected with that“ (Vilma, 38). Several participants expressed their desire to keep additional products for later use because they owned so little, but they lacked space in their homes, which supports the responses from camp residents described by Salem et al. (2020).

Keeping the Product for the Same Scope

Keeping a product for the same scope was mentioned only once: “I still use the pot, and I find it advantageous to cook tamales with that” (Odilia, 46). This behavior reflects the fact that the poor simply do not have money to buy new things, which will change as their income increases. Consequently, people will contribute to the increasing production of waste and pollution in cities and suburban areas in the future.

Keeping the Product for a Different Scope

A prevalent answer (mentioned 16 times) shows the willingness of the participants to use the same product for a different scope when it loses its functionality (Figure 2). One participant described the delicious food she cooked in a pot and said that, even though she could no longer use it for that, she still used the item for a different purpose: “I used [the pot] as a flower bowl” (Juana, 49). This reuse behavior makes the disposal process superfluous for the time being. Doing so allowed the respondents to save money for something else that was perhaps more important to them. The situation will worsen with an increase in disposable income–the volume of obsolete items stored in this household type has not been quantified so far.

Figure 2. Example of keeping household possessions for a different purpose. Source: Authors' illustration.

Permanently Disposing of the Product: Throwing the Product Away or Burning It

Regarding the permanent disposal of products, our study reveals two dominant methods: burning in a fire pit near the respondents' homes (mentioned eight times) and discarding the items in the physical environment (mentioned 18 times). The participants often linked the category of throwing a product away (somewhere in their physical environment) with the practice of burning a product. It is remarkable that the respondents recognized (and experienced) the disadvantages of burning toxic durables, such as electronics and shoes. ”It is made of iron and so, if something like this is put in a fire, then it smells bad, and, for the people that are close to it, is dangerous for their health” (Laura, 40).

Generally, the inhabitants of Cumbre de San Nicolás prefer the ingrained disposal choice of burning trash, which is embedded in their tradition, culture, and daily routines. Burning is related to getting rid of daily non-durable goods, such as food waste and packaging. The respondents saw their parents as archetypes and explained that their parents did the same and that their children were learning from the participants. “They are learning from what I am doing. Anyone is learning from what someone else is teaching her. My parents kept it so clean. How clean it was!” (Juana, 49). Every family has a hole in the ground where it can burn its trash, and no one else is allowed to burn trash in that spot. The participants claimed to care about the cleanliness of their homes and aimed to keep trash from flying around. Another very important reason for burning their household belongings was the simple fact that the community was not connected to the MSW collection. “Yes, I burnt [the mattress] because, where I live, there is not a truck coming to collect rubbish” (Fabiana, 36). Another reason is that impoverished people cannot afford the expense of getting connected to an MSW system (Rodic-Wiersma and Bethancourt, 2012).

Permanently Disposing of the Product: Selling the Product

The rationale for selling a product (mentioned five times) is the simple fact that poor people need money, so the choice is made from a reasonable point of view. Evidently, poor people sell their items only when it is essential or when an everyday commodity is broken and must be replaced. “When I start seeing a little crack on it [pot], I already feel the pity. I am telling myself that I put effort into having the budget to buy a new one” (Juana, 49). People's emotional outcomes from selling a product make them feel proud and successful. The participants stated their satisfaction after selling an item and creating more space in their homes. “We gave the pot to the scrap dealer. He is giving a little amount of money for that. And they are passing door to door to ask for that” (Rodrigo, 65). “You have to imagine [the television] there occupying space, and for what?” (Fabiana, 36).

Permanently Disposing of the Product: Giving It Away as a Gift

Giving a product away as a gift (mentioned four times) mainly relates to emotional attachment to the item but also supports the integration of individuals within their peer networks of family and friends. “I give it better to someone in my family. This is because I can still see them, they should wear it and use it” (Laura, 40). Because family members are close to the former owner, giving an item to them keeps it under the former owner's eye, allowing him or her to preserve memories by seeing the product frequently (Kates, 2001). The people mutually help one another because the place where they live is quite small and everyone knows all the others. The value of sharing is a key teaching of the Bible. The participants were all Catholics and believed in God and the scripture's teachings. “My last piece of clothing, I gave as a present. I recognized I was not using it, and I did not want to keep it for myself, so I preferred to give it as a present to someone who was in need, but that person was not living here” (Vilma, 38). This behavior contributes to an individual's self-esteem and the self-concept of the poor. Therefore, we conclude that religion has a substantial impact on disposal behavior.

Temporarily Disposing of the Product

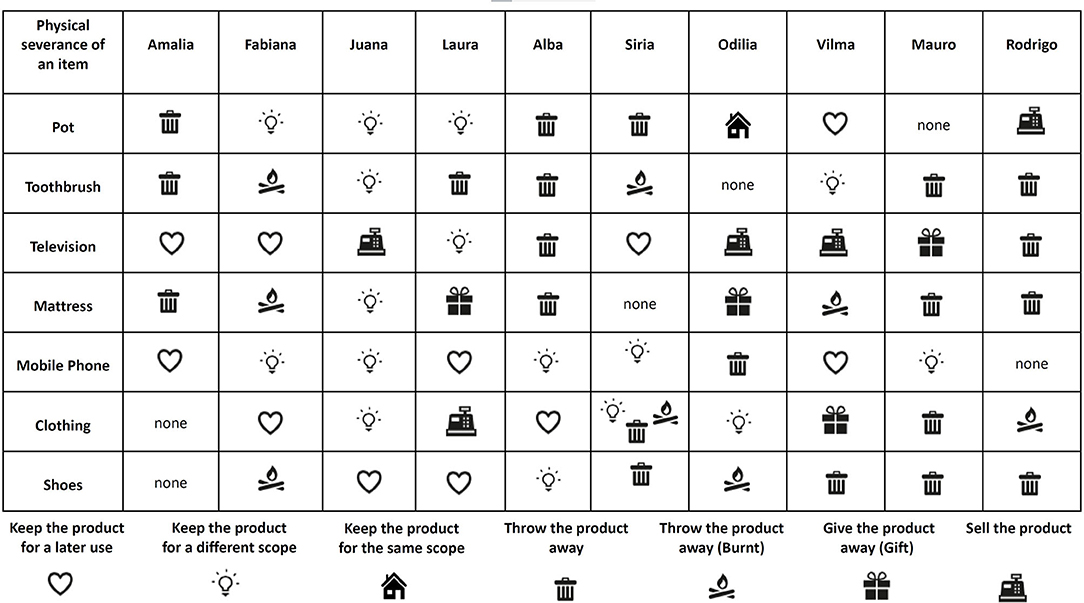

The third option of the taxonomy framework—temporary disposal of a product, such as by renting or lending it—was not mentioned. The respondents claimed that they had scarce possessions but would generally lend one to someone for free until they needed it again. Impoverished people living at the BoP cannot afford to lend “high value” items (Saunders, 2010) or lend something for an indefinite period. Therefore, we conclude that the taxonomy originally proposed by Jacoby et al. (1977) captures a higher complexity than the observed disposal behaviors at the BoP. Figure 3 provides an overview of the respondent's answers. All respondents disposed of these seven asked items. None means that the respondents did not own this item.

Figure 3. Overview of respondent's disposal decisions according to their seven household possessions.

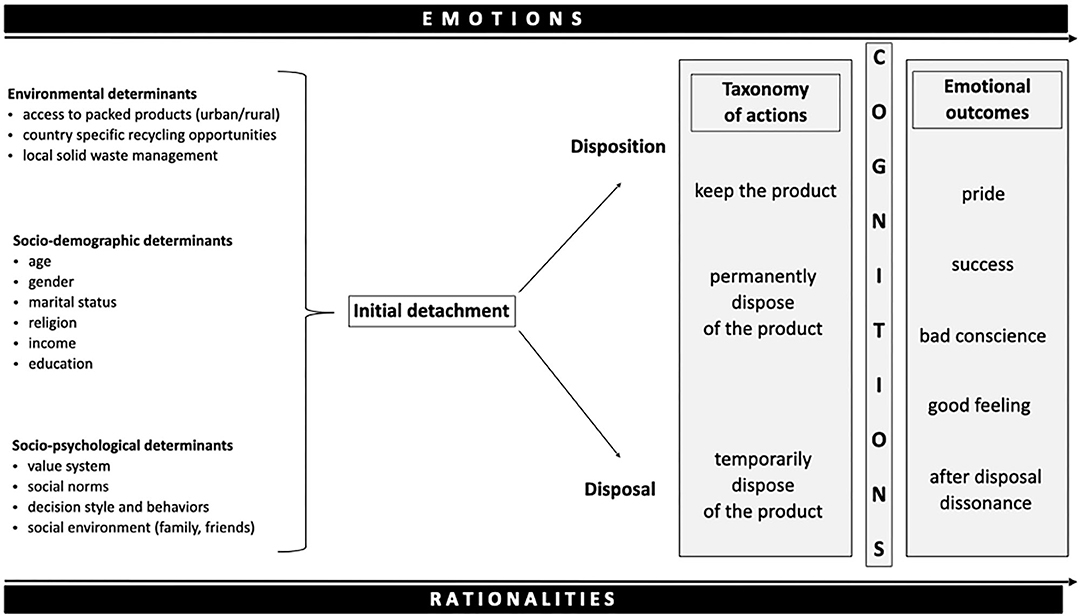

Building upon the results of this study, we suggest an intervention framework tailored to the BoP (Figure 4) to describe the disposal process. The motivation for adopting this framework is to open alternative MSW pathways that may better suit the suburban BoP and their environmental and social concerns. We extended our view by considering three categories of impact: sociodemographic, socio-psychological, and environmental determinants. These influencing determinants are in line with the relevant literature (Raab et al., 2020, 2021). The selection of determinants consolidates our qualitative results and aligns with previous research on disposal behavior (Limon et al., 2020; Salem et al., 2020). The decision to keep a product or permanently dispose of it is informed by the owners' emotions and rationalities and results in cognitive and emotional outcomes, so this framework covers both cognitive reflection and related emotional outcomes. It is the first step toward conceptualizing the disposal behavior process at the BoP. Regardless of the disposal option chosen, positive or negative emotional detachment and a reappraisal of options may occur (Salem et al., 2020). With this framework, we attempt to fill a significant gap in the current research discourse and its scholarly underpinnings. First, the after-disposal dissonance in our intervention framework is a novelty of this study. Second, pride, success and having a good feeling is in line with Türe (2014) and is refining the “value in disposition.” Third, the emotional outcome of a bad conscience fits Roman Catholicism and related traditions.

Discussion

The first research question examines the extent to which the poor are aware of the consequences of their disposal decisions and how the poorest feel about and rationalize their actions. One of the major potentials for the design of sustainable suburban MSW management systems may be a cultural shift from an understanding of waste as trash to the perception of waste as a valuable resource (Türe, 2014). Although (or perhaps because) culture is considered immaterial, it is passed down from generation to generation and is in some cases reinterpreted, which could serve as a means for rethinking disposal behavior to improve sustainability (Cristiano et al., 2020) and the well-being of a city's population. Results go beyond previous research by demonstrating the significant role that religion plays in the informal society investigated in this study. Further, emotional attachment, family and interpersonal relationships, and mutual caretaking and helpfulness in a country dominated by Catholicism substantially affect disposal behavior (Wagner and Raab, 2017a,b; Raab and Wagner, 2019a,b).

The second research question relates to the motives and consequences of disposal decisions at the BoP. Our research revealed that an emotional state arises during and after an individual detaches emotionally from an item, which opens a field of interventions in which city managers could act quickly. If poor people believe that environmental protection and recycling are ways of doing good and that these behaviors could positively influence how others see them, they will consider their disposal behavior in terms of environmentalism. Pleasant arousal from a clean environment plays a significant role in enhancing affective commitment to environmental preservation and recycling, which complements the results of Brosius et al. (2013). Our results support the finding that positive emotions, such as pride, success, and having a good feeling, are essential for strengthening self-expressive recycling and upcycling (Ahmad and Thyagaraj, 2015; Raab et al., 2020). The respondents' knowledge of the health risks related to the daily routine of burning waste was surprising and demonstrates that they are aware of this despite low education, although they contravene their behavioral intentions. Notably, the qualitative results of the interviews emphasize the relevance of positive intervention relation to pride and good feeling, leveraging the self-concept of the suburban BoP residents.

Finally, this study's limitation arises from a mono-religious research context. It would be interesting to replicate this study in informal societies with heterogeneous religious backgrounds. Because the disposal dissonance is not limited to impoverished consumers, quantitative scale development and validation are the obvious next steps for further research.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by ethics committee of University of Kassel. The participants provided verbal informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

GT and RW: research design. Local contact agent and GT: interviews. KR: secondary data. GT and KR: analysis of interviews. KR and RW: writing and revision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

\References

Ahmad, A., and Thyagaraj, K. S. (2015). Consumer's intention to purchase green brands: the roles of environmental concern, environmental knowledge and self expressive benefits. Curr. World Environ. 10, 879–889. doi: 10.12944/CWE.10.3.18

Brosius, N., Fernandez, K. V., and Helene Cherrier, H. (2013). Reacquiring consumer waste: treasure in our trash? J. Public Policy Mark. 32, 286–301. doi: 10.1509/jppm.11.146

Cristiano, S., Zucaro, A., Liu, G., Ulgiati, S., and Gonella, F. (2020). On the systemic features of urban systems. A look at material flows and cultural dimensions to address post-growth resilience and sustainability. Front. Sustain. Cities 2:12. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2020.00012

Cruz, M., Foster, J. E., Quillin, B., and Schellekens, P. (2015). Ending Extreme Poverty and Sharing Prosperity: Progress and Policies. Available online at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/23604/Ending0extreme0rogress0and0policies.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed February 12, 2021).

Hettiarachchi, H., Ryu, S., Caucci, S., and Silva, R. (2018). Municipal solid waste management in Latin America and the Caribbean: issues and potential solutions from the governance perspective. Recycling 3:19. doi: 10.3390/recycling3020019

Inglis, D. (2005). Culture and Everyday Life. New York, London: Psychology Press APA, Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

Jacoby, J., Berning, C. K., and Dietvorst, T. F. (1977). What about disposition? J. Mark. 41, 22–28. doi: 10.1177/002224297704100212

Kates, S. M. (2001). Disposition of possessions among families of people living with aids. Psychol. Mark. 18, 365–387. doi: 10.1002/mar.1012

Kaza, S., Yao, L. C., Bhada-Tata, P., and Van Woerden, F. (2018). What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050. Urban Development. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/30317 (accessed February 12, 2021).

Lastovicka, J. L., and Fernandez, K. V. (2005). Three paths to disposition: the movement of meaningful possessions to strangers. J. Consum. Res. 31, 813–823. doi: 10.1086/426616

Limon, M. R., Vallente, J. P. C., and Corales, N. C. T. (2020). Solid waste management beliefs and practices in rural households towards sustainable development and pro-environmental citizenship. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manage. 6, 441–456.

Pieters, R. (1993). “Consumers and their garbage a framework, and some experiences from the Netherlands with garbage separation programs,” in: E-European Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 1, eds W. F. Van Raaij and G. J. Bamossy (Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research), 541–546.

Raab, K., Salem, M., and Wagner, R. (2021). Antecedents of daily disposal routines in the Gaza Strip refugee camps. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 168:105427. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105427

Raab, K., and Wagner, R. (2019a). “Can god save our environment from waste? – an exploratory study of international flight passengers,” in Proceedings of the 18th Cross Cultural Research Conference (San Juan, PR).

Raab, K., and Wagner, R. (2019b). “Impoverished Consumers dispose of their waste differently: A study from Cumbre San Nicolas-Guatemala,” in 22nd Asia-Pacific Conference on Global Business, Economics, Finance and Social Sciences (Bangkok).

Raab, K., Wagner, R., and Salem, M. (2020). Feeling the waste - evidence from consumers' living in Gaza Strip camps. J. Consum. Mark. 37, 921–931. doi: 10.1108/JCM-04-2019-3171

Randhawa, P., Marshall, F., Kushwaha, P. K., and Desai, P. (2020). Pathways for sustainable urban waste management and reduced environmental health risks in India: winners, losers, and alternatives to waste to energy in Delhi. Front. Sustain. Cities. 2:14. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2020.00014

Rodic-Wiersma, L., and Bethancourt, J. (2012). Rehabilitation of the waste dumpsite in Guatemala City. Available online at: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/fulltext/261803 (accessed February 12, 2021).

Roster, C. A. (2001). “Letting go: the process and meaning of dispossession in the lives of consumers,” in Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 28, eds Mary C. Gilly and J. Meyers-Levy Valdosta (Atlanta, GA: Association for Consumer Research), 425–430.

Roster, C. A. (2014). The Art of Letting Go: creating dispossession paths toward an unextended self. Consum. Mark. Cult. 17, 321–345. doi: 10.1080/10253866.2013.846770

Roster, C. A. (2015). Help, I Have Too Much Stuff!': extreme possession attachment and professional organizers. J. Consum. Aff. 49, 303–327. doi: 10.1111/joca.12052

Salem, M., Raab, K., and Wagner, R. (2020). Solid waste management: the disposal behavior of poor people living in Gaza Strip refugee camps. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 153:104550. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104550

Saunders, S. (2010). “An exploratory study into the disposition behaviour of poor bottom-of-the-pyramid urban consumers,” in Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 37, eds M. C. Campbell, J. Inman, and R. Pieters (Duluth, MN: Association for Consumer Research), 440–446.

Thompson, C. J., Locander, W. B., and Pollio, H. R. (1989). Putting consumer experience back into consumer research: the philosophy and method of existential-phenomenology. J. Consum. Res. 16, 133–146.

Türe, M. (2014). Value-in-disposition: exploring how consumers derive value from disposition of possessions. Mark. Theory 14, 53–72. doi: 10.1177/1470593113506245

Ulgiati, S., and Zucaro, A. (2019). Challenges in urban metabolism: sustainability and well-being in cities. Front. Sustain. Cities 1:1. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2019.00001

Valle, R. S., King, M., and Halling, S. (1989). “An introduction to existential-phenomenological thought in psychology,” in Existential-Phenomenological Perspectives in Psychology (Boston, MA: Springer), 3–16.

Wagner, R., and Raab, K. (2017a). “Assessing emotions in sales interactions: a reaction time based procedure,” in Global Sales Science Institute Conference 2017 (Mauritius: Huston University).

Wagner, R., and Raab, K. (2017b). “Religious impacts on disposal behavior: does religion influence people's disposal behavior?,” in Proceedings of the 17th Cross Cultural Research Conference 2017 (Maui).

Waste Atlas (2021). Guatemala. Available online at: http://www.atlas.d-waste.com/ (accessed February 12, 2021).

World Bank (2020). The World Bank in Guatemala - An Overview. Available online at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/guatemala/overview (accessed February 12, 2021).

Keywords: disposal behavior, emotions, Guatemala, household waste, religion, sustainability, suburban areas

Citation: Raab K, Tolotti G and Wagner R (2021) Challenges in Solid Waste Management: Insights Into the Disposal Behavior of Suburban Consumers in Guatemala City. Front. Sustain. Cities 3:683576. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2021.683576

Received: 21 March 2021; Accepted: 16 June 2021;

Published: 09 July 2021.

Edited by:

Feni Agostinho, Paulista University, BrazilReviewed by:

Dominique Kreziak, Université Savoie Mont Blanc, FranceTamara Fonseca, São Paulo State University, Brazil

Copyright © 2021 Raab, Tolotti and Wagner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ralf Wagner, cndhZ25lckB3aXJ0c2NoYWZ0LnVuaS1rYXNzZWwuZGU=

Katharina Raab

Katharina Raab Giulia Tolotti

Giulia Tolotti Ralf Wagner

Ralf Wagner