- 1Education and Learning Sciences Group (ELS), School of Social Sciences (WASS), Wageningen University & Research, Wageningen, Netherlands

- 2School of Architecture and Urban Planning, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, Porto Alegre, Brazil

- 3Institute of Research in Urban and Regional Planning (IPPUR), Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- 4Institute of Energy and Environment (IEE), University of São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, Brazil

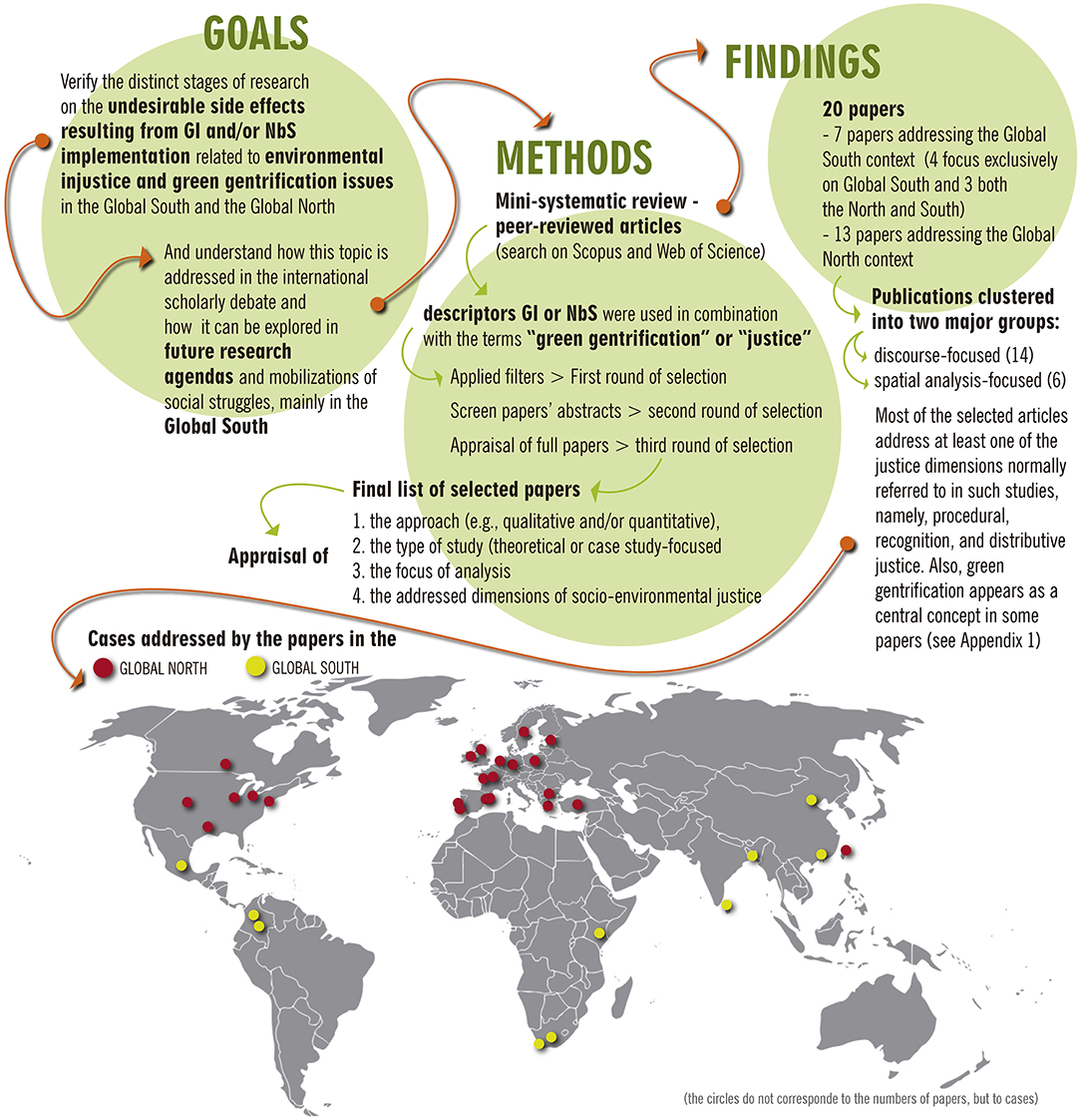

The design and deployment of green amenities is a way to tackle cities' socio-environmental problems in the quest for urban sustainability. In this study, we undertake a systematic review of research published in international peer-reviewed journals that analyzes environmental justice issues within the context of the deployment of urban green amenities. Since most studies focus on the Global North, where this scholarship first emerged, our goal is to link the literature focused on the North and the South. This study aims to outline similarities and differences regarding the nexus of justice and the greening of cities in both contexts as well as to identify knowledge gaps in this scholarship in the Global South. “Green infrastructure” and “nature-based solutions,” as the leading concepts for cities' greening agendas, are used as descriptors in combination with “justice” and/or “green gentrification” in searches undertaken of two bibliographic databases. Our results show there is a need to better delineate a research agenda that addresses such issues in a heterogeneous Global South context while gaining insights from advances made by research on the Global North.

Introduction

An increasing number of studies have investigated and demonstrated undesirable side effects of implementing green amenities in cities to promote more resilient territories and better quality of life. “Nature-based solutions” (NbS) and “green infrastructure” (GI) are well-established concepts that generally outline the agenda and orientations followed by cities in their quest for urban greening. The undesirable side effects resulting from GI and/or NbS implementation reported in recent scholarly research are related mainly to environmental injustice and the deepening of economic inequalities, which are mostly linked to green gentrification processes (Anguelovski et al., 2020). Therefore, environmental justice has been increasingly recognized as a crucial investigatory approach within the context of the new urban agenda for green spaces (Silva et al., 2018; Liotta et al., 2020; Mabon, 2020). Studies in environmental justice since Robert Bullard's classic “Dumping in Dixie” (Bullard, 2008) have exposed the uneven distribution of environmental harm in the territory, with greater exposure to black and more vulnerable populations. Contemporary authors have observed the widening of the scope of themes linked to mapping environmental inequalities, related to privileges and power imbalances (Acselrad, 2010), as well as agendas associated with the unequal destruction of green areas in cities (Park and Pellow, 2013; Anguelovski et al., 2019), or the impacts of climate change (Mohai et al., 2009). The deployment of GI and NbS can trigger increased land prices, leading to displacement of local communities that cannot afford higher living costs (Safransky, 2014; Miller, 2016; Shokry et al., 2020). In that sense, the notion of “green gentrification” addresses the social consequences of urban greening from environmental justice and political ecology perspectives. Green gentrification can be defined as a process triggered by the creation of a green amenity or green renewal of an urban area, which results in changes in the residents' pattern and whitening of the territory due to removals and rising of land prices (Gould and Lewis, 2012).

Other lenses of justice concern unequal spatial distribution (Venter et al., 2020) and unequal sharing of financial investments in green amenities, since wealthier social groups tend to be more favored than disadvantaged ones (Bockarjova et al., 2020). Injustices related to how nature is framed and certain narratives and cultural practices are endorsed to others' detriment (Anguelovski et al., 2019).

The starting point is scholarly evidence that research on this topic is further advanced in the context of the Global North and still in its initial stages in the Global South. For instance, there is a significant number of literature reviews on the topics of Green Infrastructure and Nature-based Solutions primarily focusing on the Global North context (Tzoulas et al., 2007; Ferreira et al., 2020; Oral et al., 2020; e.g., Chatzimentor et al., 2020), while a lack of such studies centered on the Global South or the North-South connection is noted. For the Global South context, it is necessary to recognize the social processes behind the space production, and the specifics of the colonial, extractive, and unequal formation of these territories that contribute to a long-lasting perpetuation process of social inequalities and injustices (Rolnik, 2011). It is essential to observe the limits (or barriers) that this material reality imposes on the capacity to react against this process from an institutional and social viewpoint.

In this sense, this study has two objectives. The first is to verify the assumption described above concerning the distinct stages of that research topic on the Global South and the Global North. The second is to understand how the theme is addressed in the international scholarly debate and how it can be explored in future research agendas as well as within mobilizations of social struggles, mainly in the Global South.

Methods

For our systematic literature review of peer-reviewed articles, the search was carried out using two prominent electronic bibliographic databases, Scopus and Web of Science. The descriptors GI or NbS were used in combination with the terms “green gentrification” or “justice” appearing in titles, keywords, or abstracts (see Figure 1). The concepts of GI and NbS were chosen—despite the existence of other terms related to urban greening (e.g., green spaces, green areas etc.)—due to both their connection to the special issue's scope and tests carried out with other descriptors within the bibliographic databases. These concepts showed the highest incidence in research agendas and scholarly publications in recent years. It should be noted as well the growing interested for these concepts and their adoption by global and local NGOs, scientific reports, economic agencies, and multilateral organizations. Subsequently, a filter by subject area was applied to the resulting list of papers to exclude those that unrelated to social and/or environmental sciences (e.g., medicine, energy, and chemical engineering). Then, we searched for the descriptor “cities” in the results to exclude papers focused on non-urban areas. Next, the term “Global South” was applied as a filter to identify which of the papers applied to this context. These steps were applied in both search databases, and the results were merged. Following this, all papers' abstracts were screened in order to exclude those that did not have “justice” and/or “green gentrification” as central topics of analysis.

Full papers of the final list were appraised by the authors for data extraction. In that phase, papers that did not properly meet the study goal were still identified and excluded (e.g., papers that did not analyze green amenities under the conception of GI or NbS, or papers focused on best practices without centrally addressing justice or green gentrification issues). Each of the remaining papers was then appraised to identify (1) the approach (e.g., qualitative and/or quantitative), and (2) the type of study (theoretical or case study-focused), (3) the focus of analysis, and (4) the addressed dimensions of socio-environmental justice. Data were then extracted and organized, following these categories, in an Excel spreadsheet. Finally, it should be noted that shortcomings in such a systematic review are unavoidable, as such publications as books, dissertations, and non-English regional journals were excluded from the review.

Results

Our search in the bibliographic databases resulted in 64 papers after applying filters described in the methods, of which 20 met the scope of this study after abstract and full text screening (for a synthetic view of the 20 selected papers, see Appendix 1). Among these, it was found that seven papers address the Global South context, of which four (Anguelovski et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019; Sultana et al., 2020; Venter et al., 2020) focus exclusively on case studies in the Global South and three (Tozer et al., 2020; Woroniecki et al., 2020) investigate multiple cases, including cities in the North and South. Out of this sample of articles, it is important to note here that one paper, produced by Anguelovski et al. (2020), does not specifically address either the South or the North (see indication in Appendix 1), as it is a theory-oriented study; however, it updates boundaries related to justice issues within urban greening of special interest to the Global South, presenting ideas of extreme relevance to this review (please see indication in Appendix 1).

Anguelovski et al. (2019) were the first to address the Global South context, while Safransky (2014) was the first to focus on the Global North. This indicates that the connection between justice issues and the implementation of an urban green agenda in the South is still in its initial stage in the international debate. Although heterogeneous, the Global South has more socially vulnerable territories in which access to justice and rights are still under construction. The contemporary right to the city claims for a better quality of life, just sustainability, and different justice dimensions (Coolsaet, 2020). In this sense, it is a contradiction that such approaches are not coined from this reality, as the Global South has a strong transforming potential in contributing with this topic. On the contrary, research indicates that GI and NbS agendas in the Global North reinforce neoliberal global capitalism expansion (Kotsila et al., 2020).

Our appraisal of the 20 papers suggests that publications can be clustered into two major groups, namely, discourse-focused (14 papers) and spatial analysis-focused (6 papers)—see Appendix 1 and Figure 1. The former is predominantly focused on qualitative approaches and mainly analyzes discourses, actors' perceptions, power relations, and how these topics relate to socio-environmental justice aspects in the design, implementation, and use of urban green amenities. These papers are either supported by case studies or present theoretical approaches. The latter are essentially quantitative studies that analyze the inequality in spatial distribution of the green amenities of whole cities or countries according to different socioeconomic status of citizens as well as the lack of prioritization of marginalized communities due to racial, economic, and social aspects in projects of GI and/or NbS. In addition, most of the selected articles address at least one of the justice dimensions normally referred to in such studies, namely, procedural, recognition, and distributive justice. The first two prevail in papers classified as discourse-focused, while distributive justice is the main focus of the spatial analysis-focused papers. Green gentrification appears as a central concept in some papers, either as the only focus of analysis or associated with one or more dimensions of justice.

Among six papers focusing on the Global South, four were classified as discourse-focused. From this set of publications, the most cited is Anguelovski et al. (2019) about a case of green infrastructure planning in Medellin, Colombia. This paper reinforces the need for more empirical research and cases in the region, and helps to affirm the urban greening agenda entry more as a neoliberal discursive agenda (Kotsila et al., 2020) than a bottom–up process with particularities, demands, and local dimensions.

Discussion

The Global North and South have clear differences in social, economic, political, and cultural dynamics as well as institutional structures. The four aspects identified on how justice issues are related to implementation of urban green amenities—procedural, recognition, distributive justice, and green gentrification—appear as broad frames of analysis applied to both contexts; however, each reality has particular dimensions. In this section, we outline the main issues observed in each of these aspects for both the Global North and South realities to capture similarities and differences. This would help to identify the specific needs of the research agenda in the Global South; concurrently, scholars focused on the Global North can also benefit from emerging questions and proposals in the Global South concerning this topic. However, although the Global South has historical socio-economic structural similarities, it is still rather heterogeneous, with distinct processes of city production, which requires further critical analysis. The historical formation and production of inequalities in cities of Latin America, Africa, and Asia are very different. Thus, we need more empirical-based analyses (local and regional) to understand each place's specifics.

Procedural justice is fundamentally related to how the participation of various actors involved in GI or NbS projects is structured and conducted with the aim of producing spaces that meet the needs of communities effectively in a fair way (Haase et al., 2017; Amorim et al., 2020). Top–down GI or NbS projects, with limited involvement of diverse actors (mainly excluding disadvantaged communities) (Anguelovski et al., 2019), are widely recognized as directing the urban green agenda to the most privileged social groups (Toxopeus et al., 2020; Verheij and Nunes, 2020), thereby producing unequal distribution of environmental improvements within cities (Venter et al., 2020). However, participation alone does not guarantee desired procedural fairness (Woroniecki et al., 2020). The research in the Global North highlights the effects of power structures on the definition of who is included or not in participatory processes (Miller, 2016; Verheij and Nunes, 2020) or what discourses are most/least endorsed and accounted for in participation (Safransky, 2014; Woroniecki et al., 2020). These papers emphasize the need to hold a critical perspective on how dialog is implemented, facilitated, and delivered within participatory processes to effectively include the various ontologies and epistemologies of different participants (Woroniecki et al., 2020; e.g., Verheij and Nunes, 2020). In the Global South, this seems rather challenging given the pronounced disparities between social groups. Residents of informal settlements or marginalized communities have less voice and access to decision-making arenas than privileged groups with greater political power and influence, as illustrated by the Greenbelt project in Medellin (Anguelovski et al., 2019). In such context, Anguelovski et al. (2020) argue that an environmental justice perspective is needed that takes an anti-subordination stance and an emancipatory approach toward autonomy as well as respect for marginalized communities, which requires the transformation of institutions and practices that reproduce such systems.

The articles in our review reveal a strong interplay between recognition and procedural justice, since the way participation is conducted is key to the effective incorporation of the plurality of values, goals, and practices of a given community in a GI or NbS project (Tozer et al., 2020; e.g., Toxopeus et al., 2020). The critical scrutiny of how structural inequality and hegemonic worldviews—usually those aligned with a neoliberal agenda and technical discourses to the detriment of peripheral, marginalized voices and traditional knowledge—shape GI and NbS projects, come into focus (e.g., Safransky, 2014; Toxopeus et al., 2020). Safransky (2014) remarks that the hegemonic and technical discourses of nature as “infrastructure” have paved the way for discrediting alternative approaches to how green spaces should be praised or planned. This is in line with Woroniecki et al. (2020), who stress that the instrumental use of nature reflects dominant frames underpinned by ideas of economic development and extractivism (resulting in more environmental deterioration), while marginalized knowledge and subjectivities are more likely to associate nature with intrinsic values. It follows that a more critical appraisal of GI and NbS approaches is required, toward a broader appropriation of place-based knowledge and subjectivities throughout a project's deployment (Woroniecki et al., 2020). For example, it would include the views and demands of traditional indigenous communities and so-called first nations (Lyons et al., 2017; Jelks et al., 2021), as well as community strategies to resist agendas that not favor disadvantages groups (Apostolopoulou and Kotsila, 2021). Anguelovski et al. (2019) uses the case of Medellin to show how a large GI project is promoted by the municipality through a top–down approach focusing on control and rationalization of green spaces for use by privileged social segments and tourists; this leads to a conflicting notion of nature with those of local communities, as it neglects the community's existing forms of relationship with nature and local practices (e.g., urban farming practices).

The selected articles focusing on distributive justice mainly address, in both the Global North and South, issues regarding whether GI is prioritized in areas inhabited by disadvantaged communities and the extent to which GI projects tend to be concentrated in wealthier areas (Venter et al., 2020; Verheij and Nunes, 2020). This aspect also encompasses methodological approaches to address this problem, such as indexes to identify sites with greater demand for green amenities (Zhu et al., 2019; Liotta et al., 2020). Such research, however, highlights that indexes alone do not guarantee environmental justice as a whole, and it is essential to consider ways to address the other justice dimensions holistically. In addition, GI or NbS projects in locations deprived of green areas where disadvantaged communities reside may involve gentrification processes or evicting these populations (Mabon, 2020; Shokry et al., 2020), rendering distributive justice particularly complex. In the Global South, special emphasis is placed on how the implementation of GI or NbS is intertwined with the eviction and relocation of disadvantaged communities in informal settlements (e.g., favelas)—in many cases located in risky areas (e.g., hillsides or riverbanks); this not only leads to the erosion of the social fabric of these communities but also puts them in a less favorable geographical location than before where it becomes increasingly difficult for them to make a living (Anguelovski et al., 2019; Sultana et al., 2020). This raises critical questions for the Global South. If GI reaches these most deprived communities and qualifies the areas where they live, how can gentrification of these places be prevented? If removal has occurred, was it necessary? What is the social cost to these populations and is the remedy provided for them just?

Finally, the selected papers focused on green gentrification, mainly in the Global North, explore this aspect from various perspectives. Most studies are largely concerned with understanding the dynamics of valorization of a given urban area as a function of implementing a green amenity (Silva et al., 2018; Bockarjova et al., 2020; Shokry et al., 2020). Amorim et al. (2020), with a focus on Barcelona, show how intangible values and features set by cultural ecosystem services increase the level of gentrification produced by a green amenity, noting that less gentrified parks placed more emphasis on social and cultural activities. Bockarjova et al. (2020) identify a means of predicting market dynamics, establishing links between property values and different types of urban nature, to help overcome undesirable gentrification trends. Garcia-Lamarca et al. (2019) analyze several cities in Europe and North America, and shows that rebranding a city as more ecological, through intense green rhetoric, over a long period of time leads to increased living cost in these cities. Similarly, Anguelovski et al. (2019) point out that the number of Global South cities branding themselves as “green” seems to be growing; the rhetoric is aimed at attracting international capital investment for the implementation of large GI projects. The influx of private capital and the progressive dependence of municipalities on public–private partnerships tend to favor wealthier areas of a city (Sultana et al., 2020). This generates ecological enclaves and reinforces the image of a sustainable city tied to the hegemonic neoliberal discourse, eventually validating and stimulating such greening initiatives backed by international and private capital, and exempting local governments from pursuing effective responses to structural issues that could effectively tackle poverty and promote environmental justice (Anguelovski et al., 2019).

Conclusions

The Global South will show in the coming decades the most rapid urban growth with numerous informal settlements and vulnerable places (Bai et al., 2018). Thus, it is essential to consider how those Southern cities will use and/or take advantage of GI and NbS projects to address social and environmental inequalities simultaneously. Further research is required to propose responses for creating a just and resilient future for the Global South within an interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary agenda that should tackle climate, inequalities, and sustainable urban planning.

Little was gleaned from the systematic literature review regarding resistance to the effects of GI and NbS implementation in the Global South. Some clues are evident, however, including the anticipation of ongoing non-desired outcomes provided by the Global North experience. One key highlight is the importance of acknowledging the need of participatory processes from projects conception, in a community-based oriented action toward a decolonial perspective to face present and future problems in the Global South. Finally, it is important to remark that the emergence of this research agenda in the Global South, on the one hand offers lessons and recommendations hitherto focused from the Global North, and on the other, points to further challenges, gaps, and specificities to be posed by future studies, thus expanding knowledge on urban justice and green cities worldwide.

Author Contributions

DdS and PT: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, review, and editing. DdS: data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) supported this study, with the Process 2018/06685-9, which is part of the Thematic Project MacroAmb Environmental Governance in São Paulo Macro Metropolis in a Climate Variability Context (2015/03804-9).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2021.669944/full#supplementary-material

References

Acselrad, H. (2010). Ambientalização das lutas sociais - o caso do movimento por justiça ambiental. Estud. Avançad. 24, 103–119. doi: 10.1590/S0103-40142010000100010

Amorim, M. A. T., Calcagni, F., Connolly, J. J. T., Anguelovski, I., and Langemeyer, J. (2020). Hidden drivers of social injustice: uncovering unequal cultural ecosystem services behind green gentrification. Environ. Sci. Policy 112, 254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.05.021

Anguelovski, I., Brand, A. L., Connolly, J. J. T., Corbera, E., Kotsila, P., Steil, J., et al. (2020). Expanding the boundaries of justice in urban greening scholarship: toward an emancipatory, antisubordination, intersectional, and relational approach. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 110, 1743–1769. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2020.1740579

Anguelovski, I., Irazábal-Zurita, C., and Connolly, J. J. T. (2019). Grabbed urban landscapes: socio-spatial tensions in green infrastructure planning in medellín: grabbed urban landscapes. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 43, 133–156. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12725

Apostolopoulou, E., and Kotsila, P. (2021). Community gardening in hellinikon as a resistance struggle against neoliberal urbanism: spatial autogestion and the right to the city in post-crisis athens, Greece. Urban Geogr. 1–27. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2020.1863621

Bai, X., Dawson, R. J., Ürge-Vorsatz, D., Delgado, G. C., Barau, A. S., Dhakal, S., et al. (2018). Six research priorities for cities and climate change. Nature 555, 23–25. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-02409-z

Bockarjova, M., Botzen, W. J. W., van Schie, M. H., and Koetse, M. J. (2020). Property price effects of green interventions in cities: a meta-analysis and implications for gentrification. Environ. Sci. Policy 112, 293–304. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.06.024

Bullard, R. D. (2008). Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. Boulder, CO: Avalon Publishing-Westview Press.

Chatzimentor, A., Apostolopoulou, E., and Mazaris, A. D. (2020). A review of green infrastructure research in europe: challenges and opportunities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 198:103775. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103775

Coolsaet, B (Ed). (2020). Environmental Justice: Key Issues. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429029585

Ferreira, V., Barreira, A. P., Loures, L., Antunes, D., and Panagopoulos, T. (2020). Stakeholders' engagement on nature-based solutions: a systematic literature review. Sustainability 12:640. doi: 10.3390/su12020640

Garcia-Lamarca, M., Anguelovski, I., Cole, H., Connolly, J. J. T., Argüelles, L., Baró, F., et al. (2019). Urban green boosterism and city affordability: for whom is the ‘branded’ green city? Urban Stud. 58, 90–112. doi: 10.1177/0042098019885330

Gould, K. A., and Lewis, T. L. (2012). “The environmental injustice of green gentrification: the case of Brooklyn's Prospect Park,” in The World in Brooklyn: Gentrification, Immigration, and Ethnic Politics in a Global City, eds D. Judith, and T. Shortell (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books), 113–146.

Haase, D., Kabisch, S., Haase, A., Andersson, E., Banzhaf, E., Bar,ó, F., et al. (2017). Greening cities – to be socially inclusive? About the alleged paradox of society and ecology in cities. Habit. Int. 64, 41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2017.04.005

Jelks, N. O., Jennings, V., and Rigolon, A. (2021). Green gentrification and health: a scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:907. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18030907

Kotsila, P., Anguelovski, I., Baró, F., Langemeyer, J., Sekulova, F., and Connolly, J. J. T. (2020). Nature-based solutions as discursive tools and contested practices in urban nature's neoliberalisation processes. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space. doi: 10.1177/2514848620901437

Liotta, C., Yann, K., Levrel, H., and Tardieu, L. (2020). Planning for environmental justice - reducing well-being inequalities through urban greening. Environ. Sci. Policy 112, 47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.03.017

Lyons, K., Brigg, M., and Quiggin, J. (2017). Unfinished Business: Adani, the State and the Indigenous Rights Struggle of the Wangan and Jagalingou Traditional Owners Council. Brisbane, QLD: The University of Queensland.

Mabon, L. (2020). Environmental justice in urban greening for subtropical asian cities: the view from Taipei: environmental justice in urban greening in Asia. Singa. J. Trop. Geogr. 41, 432–449. doi: 10.1111/sjtg.12341

Miller, J. T. (2016). Is urban greening for everyone? Social inclusion and exclusion along the gowanus canal. Urban For. Urban Green. 19, 285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2016.03.004

Mohai, P., Pellow, D., and Roberts, J. T. (2009). Environmental justice. Ann. Rev. Environ. Res. 34, 405–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-082508-094348

Oral, H. V., Carvalho, P., Gajewska, M., Ursino, N., Masi, F., van Hullebusch, E. D., et al. (2020). A review of nature-based solutions for urban water management in european circular cities: a critical assessment based on case studies and literature. Blue Green Syst. 2, 112–136. doi: 10.2166/bgs.2020.932

Park, L. S., and Pellow, D. (2013). The Slums of Aspen: Immigrants Vs. the Environment in America's Eden. New York, NY: NYU Press.

Rolnik, R. (2011). Democracy on the edge: limits and possibilities in the implementation of an urban reform Agenda in Brazil. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 35, 239–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.01036.x

Safransky, S. (2014). Greening the urban frontier: race, property, and resettlement in detroit. Geoforum 56, 237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.06.003

Shokry, G., Connolly, J. J. T., and Anguelovski, I. (2020). Understanding climate gentrification and shifting landscapes of protection and vulnerability in green resilient philadelphia. Urban Clim. 31:100539. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2019.100539

Silva, C. S., Viegas, I., Panagopoulos, T., and Bell, S. (2018). Environmental justice in accessibility to green infrastructure in two European cities. Land 7:134. doi: 10.3390/land7040134

Sultana, R., Birtchnell, T., and Gill, N. (2020). Urban greening and mobility justice in dhaka's informal settlements. Mobilities 15, 273–289. doi: 10.1080/17450101.2020.1713567

Toxopeus, H., Kotsila, P., Conde, M., Katona, A., van der Jagt, A. P. N., and Polzin, F. (2020). How ‘just’ is hybrid governance of urban nature-based solutions? Cities 105:102839. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2020.102839

Tozer, L., Hörschelmann, K., Anguelovski, I., Bulkeley, H., and Lazova, Y. (2020). Whose city? Whose nature? Towards inclusive nature-based solution governance. Cities 107:102892. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2020.102892

Tzoulas, K., Korpela, K., Venn, S., Yli-Pelkonen, V., Kazmierczak, A., Niemela, J., et al. (2007). Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using green infrastructure: a literature review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 81, 167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.02.001

Venter, Z. S., Shackleton, C. M., van Staden, F., Selomane, O., and Masterson, V. A. (2020). Green apartheid: urban green infrastructure remains unequally distributed across income and race geographies in South Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 203:103889. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103889

Verheij, J., and Nunes, M. C. (2020). Justice and power relations in urban greening: can lisbon's urban greening strategies lead to more environmental justice? Local Environ. 26, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2020.1801616

Woroniecki, S., Wendo, H., Brink, E., Islar, M., Krause, T., Vargas, A., et al. (2020). Nature unsettled: how knowledge and power shape ‘nature-based’ approaches to societal challenges. Glob. Environ. Change 65:102132. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102132

Keywords: global south, global north, environmental justice, green gentrification, green infrastructure, nature-based solutions

Citation: de Souza DT and Torres PHC (2021) Greening and Just Cities: Elements for Fostering a South–North Dialogue Based on a Systematic Literature Review. Front. Sustain. Cities 3:669944. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2021.669944

Received: 19 February 2021; Accepted: 26 April 2021;

Published: 24 May 2021.

Edited by:

Jennifer Buyck, Université Grenoble Alpes, FranceReviewed by:

Wenjie Wang, Northeast Forestry University, ChinaMathieu Perrin, National Research Institute of Science and Technology for Environment and Agriculture (IRSTEA), France

Copyright © 2021 de Souza and Torres. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniele Tubino de Souza, ZGFuaWVsZXR1Ymlub0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Daniele Tubino de Souza

Daniele Tubino de Souza Pedro Henrique Campello Torres

Pedro Henrique Campello Torres