- 1Department of Community Medicine, Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo, Ogun State, Nigeria

- 2Yale Institute of Global Health, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

- 3Department of Public Health, Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo, Ogun State, Nigeria

Editorial on the Research Topic

Evidence on the benefits of integrating mental health and hiv into packages of essential services and care

Introduction

People living with HIV (PLWH) suffer disproportionately higher levels of mental disorders than the general population, both in high-income and low- and middle-income countries (1). There is also evidence to suggest that the burden of mental disorders is worse `in HIV compared to other chronic diseases (2). Mental disorders negatively affect client engagement and care retention and result in significant distortions in health outcomes at every stage of the HIV care continuum (1). The need for mental health care for PLWH is critical to mitigate HIV transmission and progression and improve clinical outcomes by creating awareness for mental disorders and integrating mental health services into the HIV care continuum. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health Organization (WHO) have underscored the importance of integrating HIV and mental health services, considering that both conditions accentuate each other's risk. Also, Integrated HIV-mental health approaches lead to better health outcomes, overall well-being and quality of life (3). More so, the “feasibility and acceptability of integrating mental health screening into an existing community-based program for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV targeted at pregnant women and their male partners” is acceptable (4). For success, service integration should conform with all the critical elements of integrated service delivery as outlined by the WHO- “the management and delivery of health care services so that the clients receive a continuum of preventive and curative services that cater to their needs over time and across different levels of the health system” (5).

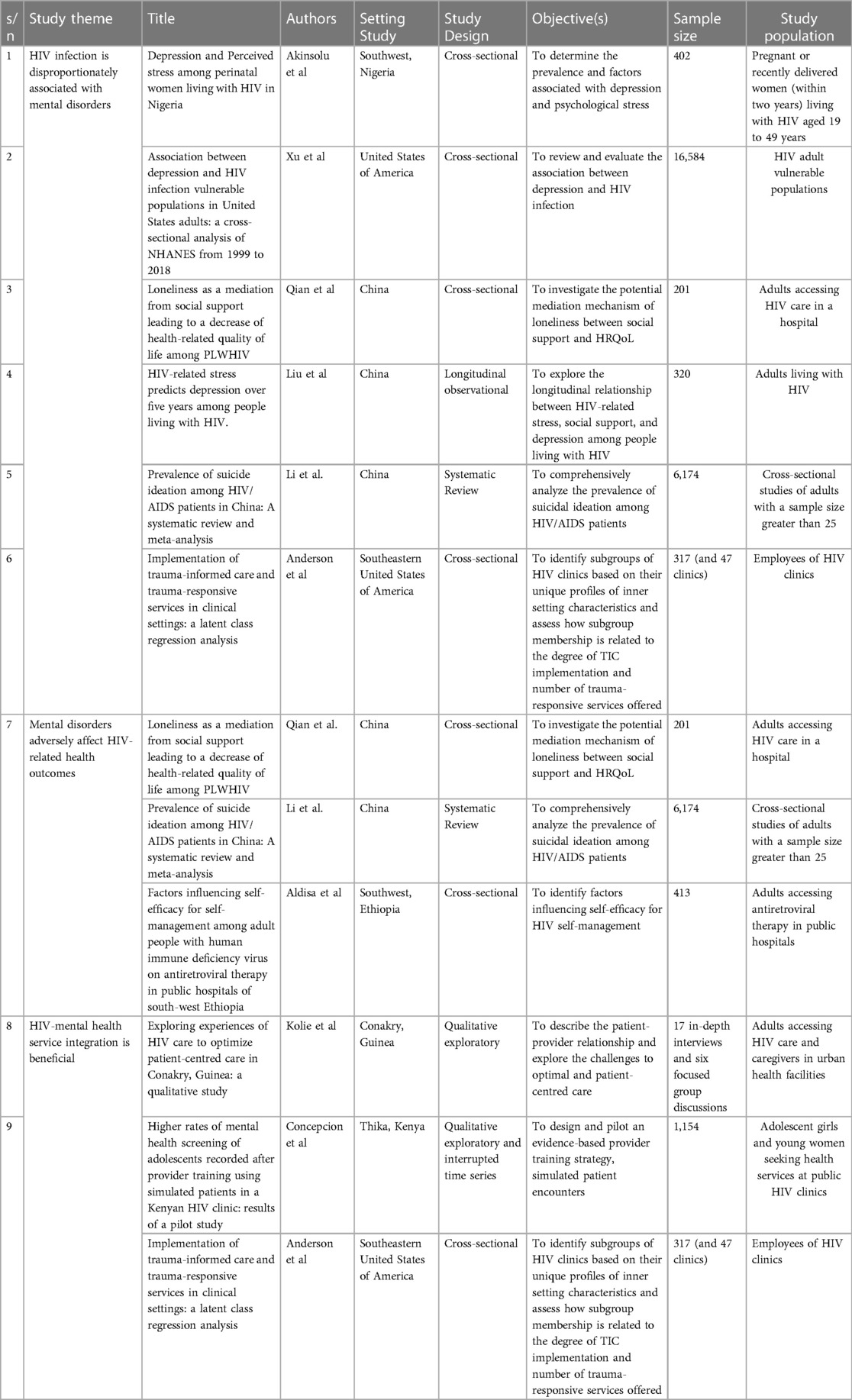

This editorial highlights some of the benefits of HIV-mental health services integration by introducing nine manuscripts published as a collection in response to the Research Topic: Evidence on the Benefits of Integrating Mental Health and HIV into Packages of Essential Services and Care. The manuscripts are from both high-income and low- and middle-income countries. Specifically, three are from China, two from the United States of America and one each from Ethiopia, Guinea, Kenya and Nigeria. The manuscripts (1) underscore the high prevalence of mental disorders among people living with HIV, (2) demonstrate that mental disorders lead to suboptimal health outcomes among PLWH, and (3) demonstrate the value of integrating mental health care into HIV care programs (Table 1).

HIV infection is disproportionately associated with mental disorders

PLWH experience disproportionately high levels of many common mental disorders. Depression is significantly associated with HIV infection in studies from Nigeria, the US and China (Akinsolu et al., Xu et al., Qian et al., Liu et al.). The accentuated burden of depression in HIV, which likely exceeds that of other chronic diseases, is thought to be mediated by HIV-related stress (2). Depression is also commoner among HIV-vulnerable populations (Xu et al.), suggesting that the drives of HIV infection may also drive depression. This collection emphasizes the mediatory role of stress and loneliness in HIV-related depression. Stress is prevalent among PLWH (Akinsolu et al.), and stress and loneliness are potent predictors of depression and anxiety among PLWH, especially in the early stages of HIV infection (Liu et al., Qian et al.). Also, suicidal ideation is prevalent and rising among PLWH (6, 7). A meta-analysis of sixteen Chinese studies shows that about one-third of PLWH had suicidal ideation (Li et al.). Furthermore, interpersonal violence is also common among PLWH (Anderson et al.).

Although it has been demonstrated that mental disorders are commoner among PLWH than the general population, it is unlikely that all HIV subpopulations are equally vulnerable to mental disorders. This collection shows that men, homosexuals, unmarried and the depressed are more affected by suicidal ideations. Also, longer periods since HIV diagnosis and lower CD4 cell counts were associated with a higher risk of suicidal ideation (Li et al.). Other factors that are related to mental disorders in PLWH include being female, serodiscordant partners, low-income levels, lack of family support, duration on ART and the gestational age among HIV-positive pregnant women (Akinsolu et al.).

Mental disorders adversely affect HIV-related health outcomes

Mental disorders are associated with HIV progression, poor medication adherence and exacerbation of the social and economic barriers to accessing HIV care, resulting in poor health outcomes and suboptimal quality of life (8). In this collection, Qian et al. used a Structural Equation Model to demonstrate a link between loneliness and reduction in health-related quality of life. Suicidal ideation is also associated with lower CD4 counts (Li et al.), while low self-efficacy is also related to drug side effects (Abdisa et al.). More so, the social context and stigmatising social process in which PLWH live, causes them to be stigmatised which further affects HIV-related health outcomes (9).

HIV-mental health service integration is beneficial

Integrating mental health services into HIV care programs has the potential to mitigate the risk of disease progression and engender better health outcomes. Integrated service delivery also increases health system efficiency and patient satisfaction. Although available evidence demonstrates the value of service integration, health system challenges, including human resources, infrastructure and supply chain management, often constitute significant hindrances. Critical success factors include human capital development, awareness creation, stakeholder ownership and commitment and continuous health system development (5).

This collection also demonstrates the benefit (real or potential) of implementing mental health care interventions within HIV care programs. Integration of psychosocial counselling into HIV care promotes confidentiality, provider availability and care, improved access to antiretrovirals and patient preferences. These factors in turn optimize patient-centred care and result in better health outcomes for people living with HIV (Kolie et al.). Also, building the capacity of HIV caregivers will increase the enhance the diagnosis and referral of mental disorders. Concepcion et al. piloted a three-day Simulated Patient Encounter training on HIV care providers in Kenya. The study shows that evidence-based provider training can improve their competencies and service delivery for common mental disorders in HIV care settings. Anderson et al. underlined the significance of implementing trauma-informed care and trauma-responsive services in HIV settings to avoid re-traumatization in those with experience of intimate partner violence. The study also demonstrates that the success of HIV-mental health integration strategies hinges on the appropriate characterization of health facilities based on critical success factors depending on the core issue under consideration.

In summary, mental disorders disproportionately affect PLWH and result in poor HIV and mental health outcomes. Integrating mental health and HIV into Packages of Essential Services and Care will help recognize and address mental health needs and result in better health outcomes among PLWH.

Author contributions

OA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TI: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that this research conduct was without any commercial or financial relationships that could constitute a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Conteh NK, Latona A, Mahomed O. Mapping the effectiveness of integrating mental health in HIV programs: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. (2023) 23(1):396. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09359-x

2. Abiodun O, Lawal I, Omokanye C. PLHIV are more likely to have mental distress: evidence from a comparison of a cross-section of HIV and diabetes patients at tertiary hospitals in Nigeria. AIDS Care. (2018) 30(8):1050–7. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1441973

3. WHO, UNAIDS. Integration of Mental Health and HIV Interventions; Key Considerations. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and the World Health Organization (2022).

4. Iheanacho T, Obiefune M, Ezeanolue CO, Ogedegbe G, Nwanyanwu OC, Ehiri JE, et al. Integrating mental health screening into routine community maternal and child health activity: experience from prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) trial in Nigeria. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2015) 50:489–95. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0952-7

5. Lenka SR, George B. Integrated health service delivery: why and how? Nat J Med Res. (2013) 3(03):297–9.

6. Yu Y, Luo B, Qin L, Gong H, Chen Y. Suicidal ideation of people living with HIV and its relations to depression, anxiety and social support. BMC Psychol. (2023) 11(1):159. doi: 10.1186/s40359-023-01177-4

7. Bamidele OT, Agada D, Afolayan E, Ogunleye A, Ogah C, Amaike C, et al. Pattern and risk factors for suicidal behaviors of people accessing HIV care in Ogun State, Nigeria: a cross-sectional survey. HIV AIDS Rev. (2023) 23(2):141–51. doi: 10.5114/hivar/171613

8. Hoare J, Sevenoaks T, Mtukushe B, Williams T, Heany S, Phillips N. Global systematic review of common mental health disorders in adults living with HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. (2021) 18(6):569–80. doi: 10.1007/s11904-021-00583-w

Keywords: mental health, HIV, service integration, health outcome, quality of life

Citation: Abiodun O, Iheanacho T and Lawal SA (2024) Editorial: Evidence on the benefits of integrating mental health and HIV into packages of essential services and care. Front. Reprod. Health 6:1454453. doi: 10.3389/frph.2024.1454453

Received: 25 June 2024; Accepted: 1 July 2024;

Published: 12 July 2024.

Edited and Reviewed by: Elizabeth Bukusi, Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), Kenya

© 2024 Abiodun, Iheanacho and Lawal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olumide Abiodun, b2x1bWlhYmlvZHVuQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Olumide Abiodun

Olumide Abiodun Theddeus Iheanacho

Theddeus Iheanacho Saheed Akinmayowa Lawal

Saheed Akinmayowa Lawal