- 1Department of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA United States

- 2Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

- 3Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

Background: Persons living in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) face disproportionate risk from overlapping epidemics of HIV and bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for prevention is gradually being scaled up globally including in several settings in SSA, which represents a key opportunity to integrate STI services with HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). However, there is limited literature on how to successfully integrate these services, particularly in the SSA context. Prior studies and reviews on STI and PrEP services have largely focused on high income countries.

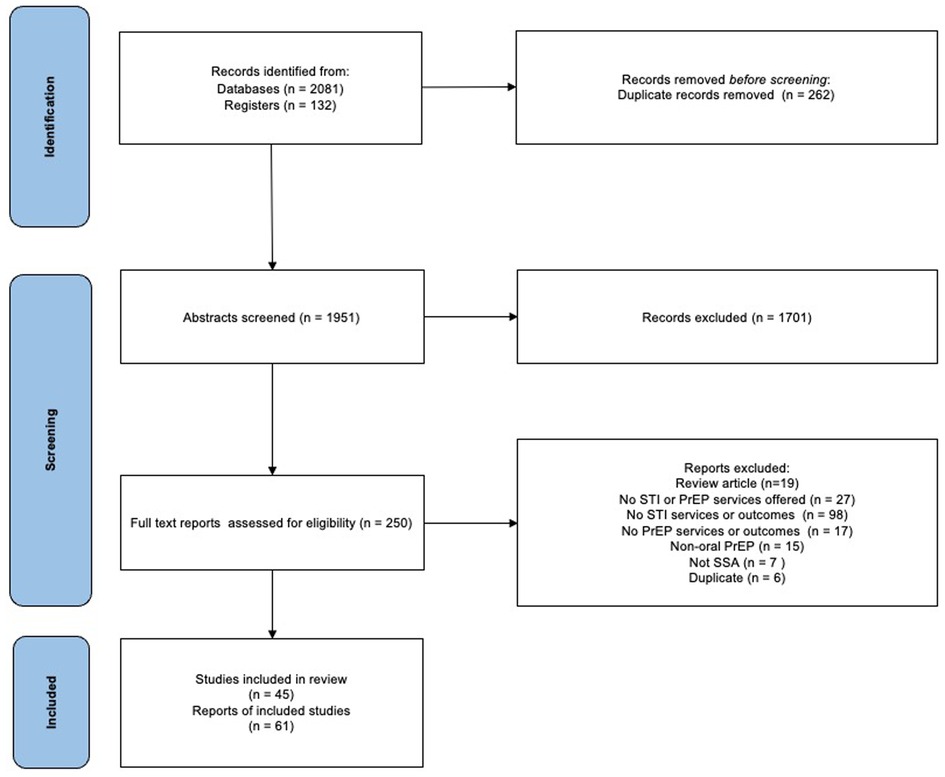

Methods: We conducted a scoping review of prior studies of integration of STI and PrEP services in SSA. We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, and CINAHL, in addition to grey literature to identify studies that were published between January 2012 and December 2022, and which provided STI and PrEP services in SSA, with or without outcomes reported. Citations and abstracts were reviewed by two reviewers for inclusion. Full texts were then retrieved and reviewed in full by two reviewers.

Results: Our search strategy yielded 1951 records, of which 250 were retrieved in full. Our final review included 61 reports of 45 studies. Most studies were conducted in Southern (49.2%) and Eastern (24.6%) Africa. Service settings included public health clinics (26.2%), study clinics (23.0%), sexual and reproductive care settings (23.0%), maternal and child health settings (8.2%), community based services (11.5%), and mobile clinics (3.3%). A minority (11.4%) of the studies described only syndromic STI management while most (88.6%) included some form of etiological laboratory STI diagnosis. STI testing frequency ranged from baseline testing only to monthly screening. Types of STI tested for was also variable. Few studies reported outcomes related to implementation of STI services. There were high rates of curable STIs detected by laboratory testing (baseline genitourinary STI rates ranged from 5.6–30.8% for CT, 0.0–11.2% for GC, and 0.4–8.0% for TV).

Discussion: Existing studies have implemented a varied range of STI services along with PrEP. This range reflects the lack of specific guidance regarding STI services within PrEP programs. However, there was limited evidence regarding implementation strategies for integration of STI and PrEP services in real world settings.

Introduction

Persons living in sub-Saharan Africa face disproportionate risk from overlapping epidemics of HIV and bacterial STIs. Specifically, young African women face a disproportionate risk of HIV acquisition, accounting for more than half of new infections on that continent, with incidence rates that are often more than double that of their male age-mates (1). At the same time, African women also face a disproportionate burden of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 358 million new cases of four curable sexually transmitted infections with the greatest burden in low- and middle-income countries (2). The overlapping epidemics of HIV and bacterial STIs in Africa have been recognized since the earliest days of the HIV epidemic.

The WHO has recommended greater bi-directional integration of STI and PrEP programs, by both incorporating STI services into PrEP programs and targeting STI clients as potential PrEP clients. Furthermore, they recommend moving beyond a syndromic approach to diagnostic STI testing and treatment, given concerns related to missed diagnoses and overtreatment (2). National PrEP guidelines in a number of countries in SSA that have rolled out PrEP recommend STI screening at baseline and in follow up; this is largely done via syndromic management due to limited resources (3–5). A number of barriers exist to implementation of STI testing and service delivery in SSA, including financial, logistical and time constraints. Despite the need for innovative approaches to providing combined STI and PrEP services, limited literature exists around models of integration of STI and PrEP programs (6, 7).

We sought to investigate the evidence around integration of PrEP services with STI services in the SSA context via a scoping review of the literature. Specifically, we aimed to better understand in what contexts STI and PrEP integration had been studied, what types of STI services had been integrated with PrEP, and what evidence existed around barriers and best practices for integration of these services.

Methods

We conducted scoping review to evaluate the evidence base for integration of PrEP and STI services in SSA. We used a systematic approach, following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (8). A study protocol was drafted and filed prior to the search, and is available online via figshare (9).

A full electronic search strategy covered all studies published between January 2012 and December 2022. Studies prior to 2012 were not included due to the lack of PrEP implementation in SSA during that period. Key words were generated to describe the scoping review concepts using index articles as well as the authors’ background knowledge. Initial search strategies were developed using PubMed advanced search builder, which was then followed by an exploratory search. The final search strategy included four core concepts: (HIV) AND (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis) AND (Sexually Transmitted Infections) AND (Sub-Saharan Africa). This search strategy was subsequently adopted to search other databases that included EMBASE, Cochrane, and CINAHL. We also searched conference proceedings and abstracts from major international HIV and STI conferences (i.e., IAS, CROI, ISTDR, INTEREST, Adherence) and the grey literature for reports focused on PrEP and STI services delivery in SSA from World Health Organization (WHO), non-governmental organizations (NGO), and intergovernmental organizations (IGO) that were available on the following databases: Union of International Associations IGO Search, IGO/NGO custom search engines, WHO Institutional Repository for Information Sharing (IRIS), and WHO Library Database. A full description of the search strategy is provided in Supplementary Appendix I.

Following the search, all identified citations were collated and uploaded into Rayyan, a collaborative software for systematic reviews, and duplicates were removed (10). English-language records with a focus on PrEP and STI service delivery were included. In line with the review question, we included studies which described provision of PrEP and STI services as well as the outcomes of these services. PrEP services were defined as provision of PrEP as well as clinical follow-up. Studies that only described promotion, education, counseling, HIV risk assessment or referral related to oral PrEP without any provision of PrEP were not included. We limited our review to oral daily PrEP as it is the current available modality of PrEP that has been approved to use in SSA. STI services were considered to include promotion, education, consulting, diagnosis (e.g., syndromic diagnosis, laboratory diagnostics, and point of care testing), treatment, or partner services. PrEP and STI outcomes included any quantitative and qualitative outcomes reported regarding these services. Because the overall goal of this scoping review was to describe existing models of STI and PrEP service integration, we also included protocols of ongoing studies that described integration of these services, even if no outcomes were available.

Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers (PA, LW) for inclusion in the review and potentially relevant articles were then retrieved in full and assessed for inclusion. If only the abstract was available, effort was made to search for a full text article related to the abstract; if none was available, the abstract was included in our review. Full text records were subsequently screened by two independent reviewers for inclusion. Information on study design, context, target population, PrEP and STI services, relevant outcomes, and conclusions were extracted by one reviewer and reviewed by a second reviewer using a data extraction sheet. Disagreements at each step were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers.

Results

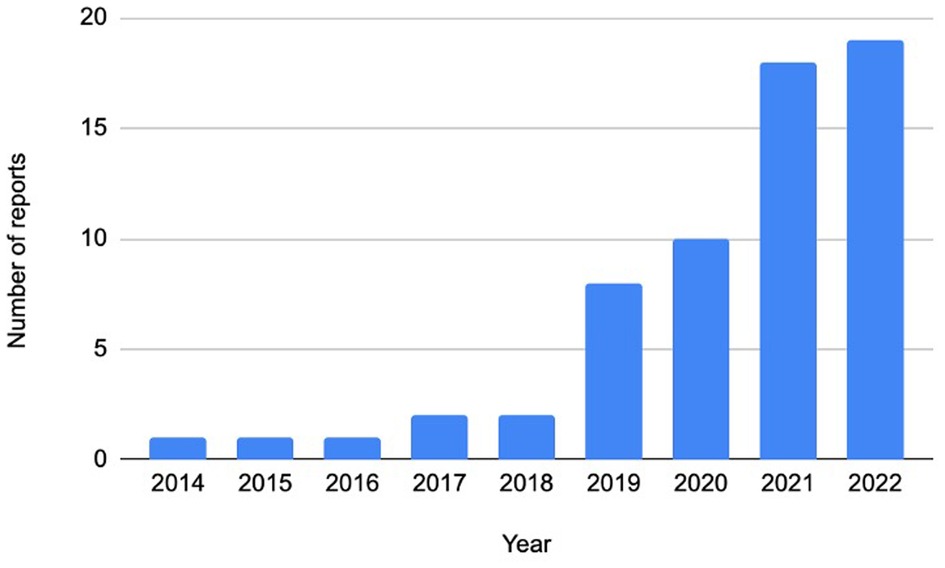

After removal of duplicates, the search strategy yielded a total of 1951 records for abstract review, of which 250 were retrieved in full. Of these, 61 reports of 45 studies were selected for inclusion. Of these, 42 (68.9%) were full text reports, 10 (16.4%) were abstracts and 9 (14.8%) were protocols. Details of the records reviewed, including reasons for exclusion at the full text stage, are provided in Figure 1. The majority of papers were published in 2019 or later (88.5%), reflecting the relatively new rollout of PrEP in SSA (Figure 2).

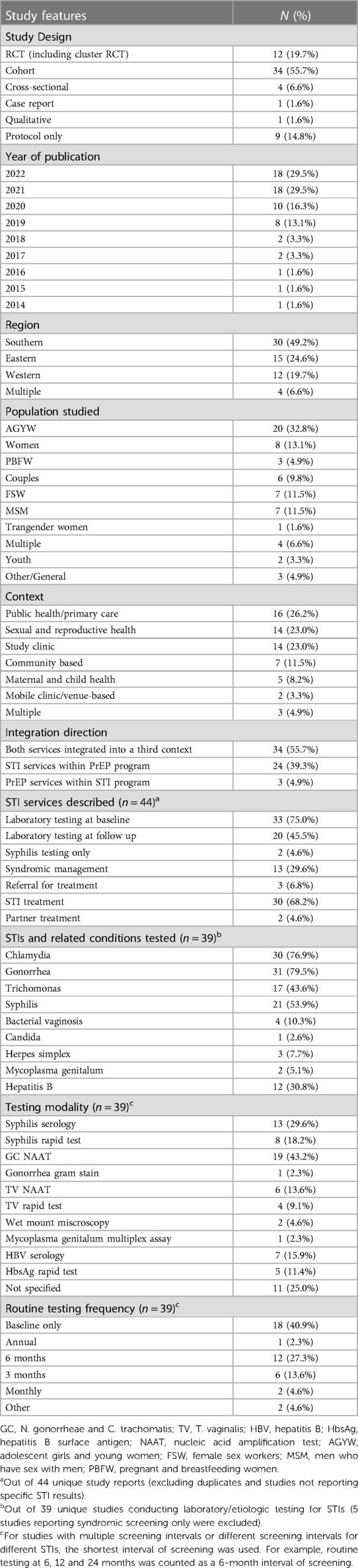

Table 1 shows the characteristics of included reports and type of services and direction of integration. Most papers described cohort studies (34/61, 55.7%), including real-world cohorts and single-arm demonstration studies; randomized control trials (RCTs) comprised a smaller proportion of the included reports (12/61, 19.7%) Consistent with the actual implementation of PrEP in SSA, most studies were conducted in Southern (49.2%) and Eastern (24.6%) Africa, with Western Africa (19.7%) representing a smaller portion of the included reports.

Most papers focused on a particular population at risk for HIV such as adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) (32.8%), female sex workers (FSWs) (11.5%), and men who have sex with men (MSM) (11.5%). Other common populations of focus included women (including peri-conception) (13.1%), pregnant and breastfeeding women (4.9%) and serodiscordant couples (9.8%). Services were implemented in a variety of contexts, including public health clinics (26.2%), study clinics (23.0%), sexual and reproductive care settings (23.0%), maternal and child health settings (8.2%), community based services (11.5%), and mobile clinics (3.3%).

In most cases, both PrEP and STI services were implemented within a third service setting (55.7%). Less frequently, STI services were implemented within a program with a primary focus on PrEP provision, including PrEP RCTs (39.3%). Few studies reported on PrEP services integrated into a primarily STI-focused program (4.9%).

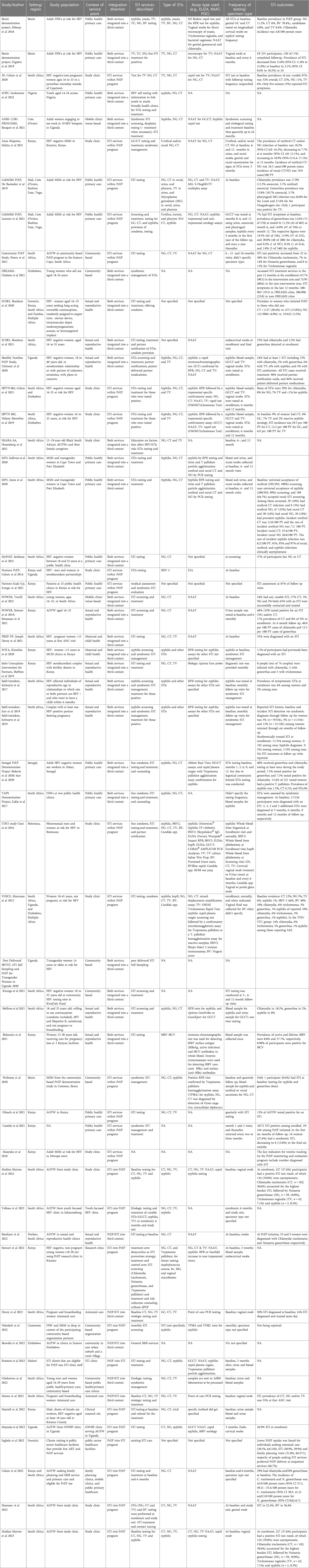

Table 2 provides a summary of data extraction for studies reviewed, including study setting, population, services provides, assays used, and major outcomes. The type of STI services offered varied and often related to the type of study (RCT, demonstration project or real-world implementation). Most studies and study protocols described STI laboratory testing at baseline (75.0%), with fewer describing any follow up laboratory STI testing (45.5%). A quarter described syndromic management, either with or without any etiological testing (29.6%). Type of STIs included in laboratory testing varied. Of 39 studies and protocols that included etiological STI testing, 30 (76.9%) tested for Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), 31 (79.5%) for Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG), 21 (53.9%) for syphilis, 17 (43.6%) for trichomonas vaginalis (TV), 4 (10.3%) for bacterial vaginosis (BV), 1 (2.6%) for Candida, 2 (5.1%) for Mycoplasma genitalium, and 3 (7.7%) for HSV.

Prevalence of STIs varied between studies. Baseline prevalence of genitourinary CT, NG, TV ranged from 5.6–30.8%, 0.0–11.2%, and 0.4–8.0% respectively. Baseline prevalence of syphilis ranged from 0.0–18.0%. Baseline prevalence of symptomatic STI by syndromic screening ranged from 0.0–11.6%. STIs detected by routine laboratory testing were reported to be frequently asymptomatic. In one study of MSM receiving PrEP, 91%, 95% and 97% of rectal, urethral and syphilis infections were clinically asymptomatic (11). In one study of AGYW receiving PrEP, baseline STI prevalence was 32%, though only 3% reported symptoms (12), while another study of AGYW presenting for HIV testing services reported 38% STI prevalence at baseline, of which 59% were asymptomatic (13). Etiological testing frequency ranged from monthly to baseline testing only.

A few distinct models of integration of STI services with PrEP emerged from our review. These included routine integration of etiologic STI testing within PrEP RCTs, routine integration of syndromic STI management within public health clinics offering PrEP, etiological screening for STIs within PrEP programs targeting at-risk groups, and community outreach and mobile-based approaches. Of these, novel approaches to integration of PrEP and STI services included use of mobile clinics and other youth-focused approaches to increase convenience and acceptability (14, 15), and provision of STI testing results as a tool for improving retention in PrEP (16). However, in most studies STI diagnosis and treatment were offered as part of a standard package of PrEP services without a focus on improving either service through integration.

Few studies described quantitative or qualitative outcomes relating to implementation of integrated PrEP and STI services. Qualitative interviews from one study evaluating mobile provision of sexual and reproductive health services including STI and PrEP services found that AGYW appreciated the practicality of service integration (14). In contrast, healthcare providers in another study cited stigma as a reason not to integrate PrEP with other sexual health services (17). There was some evidence of synergy between PrEP and STI services. One report demonstrated improved uptake of PrEP services when results of STI testing was made available to AGYW (18). Several studies demonstrated an association between positive STI diagnosis and PrEP acceptance (19, 20). Implementation science research relating to STI and PrEP service integration was very limited. One study described logistical constraints limiting availability of laboratory STI testing, but these were not explored in detail (21). One research protocol described a planned study comparing standard of care syndromic management with community-based STI services including etiologic testing, but no results are yet available (22).

Discussion

This scoping review describes existing literature around integration of STI and PrEP services in SSA. Prior literature describing provision of both these services covers a range of implementation settings, from public health clinics, sexual and reproductive health settings, mobile clinics and in the community. Most studies targeted particular at-risk groups, such as AGYW, FSW or MSM. Studies largely occurred within an existing service setting or within a PrEP program, but in nearly all studies, PrEP was the primary focus.

Despite a growing interest and rollout of PrEP in SSA, and an ongoing epidemic of curable STIs, we found limited literature covering the integration of PrEP and STI services from an implementation science perspective. Few studies addressed barriers and facilitators of integration of PrEP and STI programs. Prior qualitative work has demonstrated that challenges facing PrEP implementers in incorporating STI services include financial barriers to laboratory STI testing, logistical barriers to STI treatment in mobile settings, time constraints, lack of equipment and lack of training and capacity building around STI services(7). However, our review found a lack of evidence base addressing these barriers. In addition, while a few studies indicated potential synergies between STI and PrEP services in terms of service uptake and client satisfaction, this was not explored in detail. Most studies reported results of STI testing when offered as part of PrEP services, but did not explore the effect of bundling these services on outcomes such as acceptability or adoption.

Types of STI services offered varied widely between studies and settings, reflecting the different funding and implementation environments between RCTs, demonstration projects, and studies of real-world implementation. Some studies reported diagnostic STI screening only at baseline, while others conducted routine screening at regular intervals, and others only performed syndromic managements of STIs. The intervals of routine screening, when performed, was variable, as were the types of STIs screened. Current national PrEP guidelines in countries such as Kenya, Uganda and South Africa do not offer detailed guidance on how STI screening should be conducted (3–5), including standard guidance regarding which STIs to screen, site and frequency of screening in different populations.

Of note, laboratory diagnostic testing of STIs was mainly limited to well funded clinical studies and demonstration projects, with limited evidence from real-world public health settings. Where reported, STI prevalence and incidence by laboratory testing were high among most PrEP cohorts (11, 14, 17, 19, 23–29), with the exception of two studies of safer conception cohorts, which reported low rates of laboratory-diagnosed STIs (30, 31). In many settings, STIs diagnosed by laboratory screening were asymptomatic (12, 26, 33), reaffirming the pressing need to incorporate etiological diagnostics in STI programs offered within PrEP services.

Our scoping review has limitations. Due to the nature of the scoping review, reviewers did not assess study quality but instead gathered existing knowledge on STI services offered with PrEP programs. The review may not have captured all studies related to this topic, including sources of grey literature beyond NGO and IGO reports searched in our review. Furthermore, studies published in languages other than English were not included. Our review included abstract and study protocols in order to capture emerging literature given the relative novelty of study on the topic of PrEP and STI integration; the data collected from these sources may be less reliable than traditional peer-reviewed articles. Given the rapid emergence of literature around PrEP, our review may have failed to capture most recently published or presented literature on this topic.

Despite growing acknowledgement of the limitations of syndromic management (2), which is currently the standard practice in SSA regarding STI services within PrEP programs, few studies have addressed real-world integration of expanded STI services within PrEP programs in SSA. Future studies should examine how inclusion of additional STI services affects acceptability, adoption, and client satisfaction with both PrEP and STI services. In addition, studies should investigate cost, feasibility, and best practices regarding implementing etiologic STI diagnosis and treatment into PrEP programs in real world settings. Finally, more work in needed to understand practice setting and population-specific needs regarding integration of STI and PrEP services, including what services best suit key populations such as AGYW, MSM, FSW, and heterosexual couples, as well as how to best offer PrEP services within existing STI service contexts.

Conclusions

In this scoping review, we found a range of STI services integrated with PrEP programs in SSA. STIs are common among populations using PrEP in SSA, highlighting the need for integration of these services. There was some evidence that integration of STI and PrEP services improves uptake of and satisfaction with both PrEP and STI services but more rigorous studies are needed to describe synergies, barriers and best practices for integration of PrEP and STI programs in SSA.

Author contributions

PA, LW, and KKM contributed to the conception and design of the review plan; PA and LW conducted the initial literature review and screening process. AP, with LW, prepared the first draft of the manuscript. PA, LW, and KKM contributed to the writing and critical revision of the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health of the US National Institutes of Health (grant R01 MH123267 and R00 MH118134). The funders had no role in study design or writing of the report.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frph.2023.944372/full#supplementary-material

References

1. UNAIDS. FACT SHEET 2022. Published (2022). Available at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf (Accessed December 18, 2022).

2. WHO. Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) in the Era of Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV. (2019). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/prevention-and-control-of-stis-in-the-era-of-prep-for-hiv (Accessed March 24, 2022).

3. Uganda Ministry of Health. Consolidated guidelines for the prevention and treatment of HIV and aids in Uganda. (2018). Available at: https://elearning.idi.co.ug/pluginfile.php/5675/mod_page/content/19/Uganda%20HIV%20%20Guidelines%20-%20September%202018.pdf (Accessed March 24, 2022).

4. National AIDS & STI Control Program (NASCOP). Guidelines on Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection in Kenya. (2018). Available at: http://cquin.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/ICAP_CQUIN_Kenya-ARV-Guidelines-2018-Final_20thAug2018.pdf (Accessed March 24, 2022).

5. Bekker LG, Rebe K, Venter F, Maartens G, Moorhouse M, Conradie F, et al. Southern African Guidelines on the safe use of pre-exposure prophylaxis in persons at risk of acquiring HIV-1 infection. South Afr J HIV Med. (2016) 17(1):2–7. doi: 10.4102/SAJHIVMED.V17I1.455

6. Zablotska IB, Baeten JM, Phanuphak N, McCormack S, Ong J. Getting pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to the people: opportunities, challenges and examples of successful health service models of PrEP implementation. Sex Health. (2018) 15(6):481–4. doi: 10.1071/SH18182

7. Ong JJ, Fu H, Baggaley RC, Wi TE, Tucker JD, Smith MK, et al. Missed opportunities for sexually transmitted infections testing for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis users: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. (2021) 24(2):2–7. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25673

8. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169(7):467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

9. Models of integration of pre-exposure prophylaxis and sexually transmitted infection services in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review protocol. Available at: https://figshare.com/articles/online_resource/Models_of_integration_of_pre-exposure_prophylaxis_and_sexually_transmitted_infection_services_in_sub-Saharan_Africa_a_scoping_review_protocol/19209396 (Accessed March 24, 2022).

10. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2016) 5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

11. Jones J, Sanchez TH, Dominguez K, Bekker LG, Phaswana-Mafuya N, Baral SD, et al. Sexually transmitted infection screening, prevalence and incidence among South African men and transgender women who have sex with men enrolled in a combination HIV prevention cohort study: the sibanye methods for prevention packages programme (MP3) project. J Int AIDS Soc. (2020) 23(S6):e25594. doi: 10.1002/JIA2.25594

12. Celum CL, Gill K, Morton JF, Stein G, Myers L, Thomas KK, et al. Incentives conditioned on tenofovir levels to support PrEP adherence among young South African women: a randomized trial. J Int AIDS Soc. (2020) 23(11):e25636. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25636

13. Medina-Marino A, Bezuidenhout D, Ngwepe P, Bezuidenhout C, Facente SN, Mabandla S, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of leveraging community-based HIV counselling and testing platforms for same-day oral PrEP initiation among adolescent girls and young women in eastern cape, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. (2022) 25(7):5. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25968

14. Rousseau E, Bekker LG, Julies RF, Celum C, Morton J, Johnson R, et al. A community-based mobile clinic model delivering PrEP for HIV prevention to adolescent girls and young women in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21(1):888. doi: 10.1186/S12913-021-06920-4

15. Travill D, Ndlovu M, Kidoguchi L, Tlou T, Lunika L, Morton J, et al. Integrating STI screening into PrEP services for adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) in two primary health care (PHC) facilities in Johannesburg: lessons from prevention options for women evaluation research (POWER). J Int AIDS Soc. (2021) 24(S1):28–9.

16. Eakle R, Gomez GB, Naicker N, Bothma R, Mbogua J, Cabrera Escobar MA, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and early antiretroviral treatment among female sex workers in South Africa: results from a prospective observational demonstration project. PLoS Med. (2017) 14(11):e1002444. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PMED.1002444

17. Skovdal M, Magoge-Mandizvidza P, Dzamatira F, Maswera R, Nyamukapa C, Thomas R, et al. Improving access to pre-exposure prophylaxis for adolescent girls and young women: recommendations from healthcare providers in eastern Zimbabwe. BMC Infect Dis. (2022) 22(1):399. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07376-5

18. Oluoch LM, Roxby A, Mugo N, Wald A, Ngure K, Selke S, et al. Does providing laboratory confirmed STI results impact uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake among Kenyan adolescents girls and young women? A descriptive analysis. Sex Transm Infect. (2020) 97(6):467–8. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054637

19. Celum C, Hosek S, Tsholwana M, Kassim S, Mukaka S, Dye BJ, et al. PrEP uptake, persistence, adherence, and effect of retrospective drug level feedback on PrEP adherence among young women in Southern Africa: results from HPTN 082, a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. (2021) 18(6):e1003670. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PMED.1003670

20. Beesham I, Heffron R, Evans S, Baeten JM, Smit J, Beksinska M, et al. Exploring the use of oral Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among women from durban, South Africa as part of the HIV prevention package in a clinical trial. AIDS Behav. (2021) 25(4):1112–9. doi: 10.1007/S10461-020-03072-0/TABLES/4

21. Roberts DA, Hawes SE, Bousso Bao MD, Ndiaye AJ, Gueye D, Raugi DN, et al. Trends in reported sexual behavior and Y-chromosomal DNA detection among female sex workers in the Senegal preexposure prophylaxis demonstration project. Sex Transm Dis. (2020) 47(5):314. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001175

22. Chidumwa G, Chimbindi N, Herbst C, Okeselo N, Dreyer J, Zuma T, et al. Isisekelo sempilo study protocol for the effectiveness of HIV prevention embedded in sexual health with or without peer navigator support (Thetha Nami) to reduce prevalence of transmissible HIV amongst adolescents and young adults in rural KwaZulu-Natal: a 2 × 2 factorial randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22(1):454. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-12796-8

23. Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, Palanee T, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. (2015) 372(6):509–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA1402269

24. Chitneni P, Bwana MB, Owembabazi M, O'Neil K, Kalyebara PK, Muyindike W, et al. STI Prevalence among women at risk for HIV exposure initiating safer conception care in rural, southwestern Uganda. Sex Transm Dis. (2020) 47(8):e24. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001197

25. Delany-Moretlwe S, Mgodi N, Bekker L-G, Baeten J, Pathak S, Donnell D, et al. O10.3 high curable STI prevalence and incidence among young African women initiating PrEP in HPTN 082. Sex Transm Infect. (2019) 95(Suppl 1):A60–1. doi: 10.1136/SEXTRANS-2019-STI.160

26. Li C, Tang W, Wang C, Yang B, Peters R, Medina-Marino A, et al. P167 impact of COVID-19 on adolescent girls and young women in a community-based HIV PrEP programme in South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. (2021) 97(Suppl 1):A102. doi: 10.1136/SEXTRANS-2021-STI.268

27. Laurent C, Dembélé Keita B, Yaya I, Le Guicher G, Sagaon-Teyssier L, Agboyibor MK, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men in West Africa: a multicountry demonstration study. Lancet HIV. (2021) 8(7):e420–8. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00005-9

28. De Baetselier I, Crucitti T, Yaya I, Dembele B, Mensah E, Dah E, et al. Prevalence of STIs among MSM initiating PREP in West-Africa (COHMSM-PREP ANRS 12369-expertise France). Sex Transm Infect. (2019) 95:A245. doi: 10.1136/SEXTRANS-2019-STI.617

29. Mehta SD, Okall D, Graham SM, N'gety G, Bailey RC, Otieno F. Behavior change and sexually transmitted incidence in relation to PREP use among men who have sex with men in Kenya. AIDS Behav. (2021) 25(7):2219–29. doi: 10.1007/S10461-020-03150-3

30. Heffron R, Ngure K, Velloza J, Kiptinness C, Quame-Amalgo J, Oluch L, et al. Implementation of a comprehensive safer conception intervention for HIV-serodiscordant couples in Kenya: uptake, use and effectiveness. J Int AIDS Soc. (2019) 22(4):5. doi: 10.1002/JIA2.25261

31. Schwartz SR, Bassett J, Holmes CB, Yende N, Phofa R, Sanne I, et al. Client uptake of safer conception strategies: implementation outcomes from the Sakh’umndeni safer conception clinic in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. (2017) 20(Suppl 1):46. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.2.21291

32. Garrett NJ, McGrath N, Mindel A. Advancing STI care in low/middle-income countries: has STI syndromic management reached its use-by date? Sex Transm Infect. (2017) 93(1):4–5. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052581

33. Kaida A, Dietrich JJ, Laher F, Beksinska M, Jaggernath M, Bardsley M, et al. A high burden of asymptomatic genital tract infections undermines the syndromic management approach among adolescents and young adults in South Africa: implications for HIV prevention efforts. BMC Infect Dis. (2018) 18(1):4–5. doi: 10.1186/S12879-018-3380-6

Keywords: STIs—sexually transmitted infections, PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis), sub sahara Africa, service integration, HIV prevention, STI prevention

Citation: Anand P, Wu L and Mugwanya K (2023) Integration of sexually transmitted infection and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis services in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. Front. Reprod. Health 5:944372. doi: 10.3389/frph.2023.944372

Received: 15 May 2022; Accepted: 31 May 2023;

Published: 29 June 2023.

Edited by:

Graham Philip Taylor, Imperial College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Anwarud Din, Sun Yat-sen University, ChinaAriane Van Der Straten, University of California, San Francisco, United States

Pamela Abbott, University of Aberdeen, United Kingdom

© 2023 Anand, Wu and Mugwanya. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kenneth Mugwanya bXVnd2FueWFAdXcuZWR1

Priyanka Anand

Priyanka Anand Linxuan Wu

Linxuan Wu Kenneth Mugwanya

Kenneth Mugwanya