95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Reprod. Health , 15 February 2023

Sec. Reproductive Epidemiology

Volume 5 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frph.2023.1101400

Background and aims: The key interest of this research is to identify the causes of the ongoing increasing trends in caesarean section or C-section (CS) deliveries in both urban and rural areas of Bangladesh.

Methods: This study analyzed all Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) datasets through Chi-square and z tests and the multivariable logistic regression model.

Results: CS deliveries were found to be more prevalent in urban than in rural areas of Bangladesh. Mothers above 19 years, above 16 years at first birth, overweight mothers, those with higher educational levels, those who received more than one antenatal care (ANC) visit, fathers having secondary/higher education degrees and employed as workers or in business, and mothers living in wealthy households in the cities of Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, and Rangpur divisions had a significantly higher likelihood of CS deliveries in urban areas. Contrastingly, mothers with ages between 20 and 39 years, above 20 years at first birth, normal weight/overweight mothers, those with primary to higher level of education, those in the business profession, fathers who also received primary to higher education, mothers who received more than one ANC visit, and those living in wealthy households in Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, and Rangpur divisions were more likely to have CS deliveries in rural areas. The 45–49 age group mothers had a five times higher likelihood of CS deliveries [odds ratio (OR): 5.39] in urban areas than in rural areas. Wealthy mothers were more likely to be CS-delivered in urban (OR: 4.84) than in rural areas (OR: 3.67).

Conclusion: The findings reveal a gradual upward alarming trend in CS deliveries with an unequal contribution of significant determinants in urban and rural areas of Bangladesh. Therefore, integrated community-level awareness programs are an urgent need in accordance with the findings on the risks of CS and the benefits of vaginal deliveries in this country.

A caesarean section can be a life-saving intervention when medically indicated, but it can also trigger many short-term and long-term adverse health complications for both mother and baby (1–4). CS should be executed only when there is a medical necessity and the standard rate of CS is maintained at approximately 10%–15% (3). However, CS deliveries have been increasing noticeably worldwide during the past two decades and are also placing a high clinical and economic burden on healthcare systems (5–8). The growth in CS deliveries has been revealed to have adverse implications for the health of infants as well as mothers and increased the costs of deliveries (9–11). In comparison with vaginal or natural births, CS deliveries performed on non-medical hints in low-resource settings are linked to higher maternal hazards (7), lengthier postpartum recovery (12), higher rates of rehospitalization (13), prolonged hospital stays (14), greater risk of maternal morbidity (15), and difficulties in subsequent pregnancies (16).

A study showed that the global average CS rate increased by 12.4% in the period between 1990 and 2014, with the maximum average annual rate of increase happening in Asia (2). In Bangladesh, the rate of CS deliveries increased from 4% to 23% between the years 2004 and 2014 (4) and one-third of such deliveries occurred in 2018 (17). Moreover, the percentage of CS deliveries in Bangladesh is significantly higher than that in neighboring countries like Pakistan (14%), India (14%), and Nepal (4%) (4). There are several factors triggering the increment of CS. In most developing countries, social and educational improvements and demographic changes are the main cause for delayed pregnancies among mothers until they reach the end of their fertile lives (18). Studies have found a higher likelihood of CS among shorter mothers (19) and younger mothers with a small pelvis (20). Mothers having better socioeconomic status (21), belonging to upper social classes, highly educated ones, and living in urban and metropolitan areas are more likely to prefer CS (22–28). The high prevalence of national CS is predominantly due to the excessive rate of CS triggered by the richest population living in urban areas in South Asia as well as other low-middle-income countries (29, 30). Generally, CS is observed among mothers whose baby sizes are either smaller than average or very large, have a higher education level, and the place of delivery is a private medical institution (31). Several variables such as age, education, wealth, and the number of antenatal visits were found to be significantly positively associated with CS deliveries among low-risk mothers in India (32).

Various studies conducted in South Asian countries, including Bangladesh, have pointed out to increased concerns about the higher rate of CS and predict that the national increase in the CS rate could be partially motivated by private health facilities that are mainly driven by profit maximization (30, 33, 34). A few studies have found that some physicians conduct CS for economic gains and time management without any medical justification (35). Hospitals’ financial and organizational structures (36, 37) also influence critical decisions. The increase in monetary gains through CS encourages many health providers to choose CS (38, 39). Given the above discussion, it is therefore essential to identify the trends and the most important predictors and their influence on CS deliveries. Some studies on these already exist in the literature, but there is a significant research gap on the issue of urban–rural divide in CS deliveries in Bangladesh. Therefore, this study aims to explore the trends in CS deliveries and their determinants among Bangladeshi mothers at their reproductive age in urban–rural areas using Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) data.

This study considered all published BDHS datasets (i.e., 1993/94, 1996/97, 1999/00, 2003/04, 2007, 2011, 2014, and 2017/18) to examine the trends in CS delivery rates. However, an assessment of the association of CS deliveries with different socioeconomic and demographic characteristics and subsequent analysis is based on the most recent secondary data collected from BDHS-2017/18. The sampling frame of this survey was the list of enumeration areas (EAs) of the 2011 Population and Housing Census of the People's Republic of Bangladesh. The primary sampling unit of the survey was an EA. The survey used a two-stage stratified sampling technique. In the first stage, 675 EAs were chosen, with 227 and 448 EAs from urban and rural areas. However, data could not be collected from three EAs because of the occurrence of natural disaster. These clusters were in Dhaka (one urban cluster), Rajshahi (one rural cluster), and Rangpur (one rural cluster). In the second stage, a systematic sample of 30 households was selected from each EA. A total of 20,250 residential households were selected in four phases. Among the 20,376 ever-married women aged 15–49 years and eligible for interviews, 20,127 were interviewed, yielding a response rate of approximately 99%. The detailed sampling procedure is available in the report of BDHS-2017/18 (17).

The outcome variable in the present study was a dichotomous variable, CS delivery, (i) No or (ii) Yes. This variable was measured by asking a question to the participants, “Did you ever give birth by CS?”.

In this study, the mother's age in years (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44, and 45–49), age at 1st birth (≤16, 17–20, 21–24, and 25 or more years), body mass index (BMI) (underweight, normal, overweight/obesity), educational level (no education, primary, secondary, higher), occupation (not working, worker, business, service), the father’s education level (no education, primary, secondary, higher), the father's occupation (not working, worker, business, service), birth order (1, 2–3, 4 or more), number of antenatal visits during pregnancy (no visits, 1–4, 5–8, and 9 or more visits), religion (Muslim, non-Muslim), place of residence, wealth index (moderately poor, poorest, middle class, moderately rich, richest), and division (Barisal, Chittagong, Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, Rangpur, and Sylhet) were all considered covariates.

In this study, initially, bivariate analysis (Chi-square test) was performed to determine significant associations between mode of birth (caesarean vs. non-caesarean) and select sociodemographic factors. These associated variables were considered independent variables for the logistic regression model (unadjusted and adjusted), which was implemented to find the most influential factors for CS delivery. The logistic regression model can be expressed as

where Yi is a binary variable that takes a value of “1” if the respondent received CS delivery and “0” otherwise; Xi is a vector of independent variables and is a vector of unknown parameters that consist of the intercept parameter and the regression parameter associated with a set of covariates used in the study. The fitted form of the model can be defined as

where represents the estimated regression coefficient of the p-th independent variable in the study.

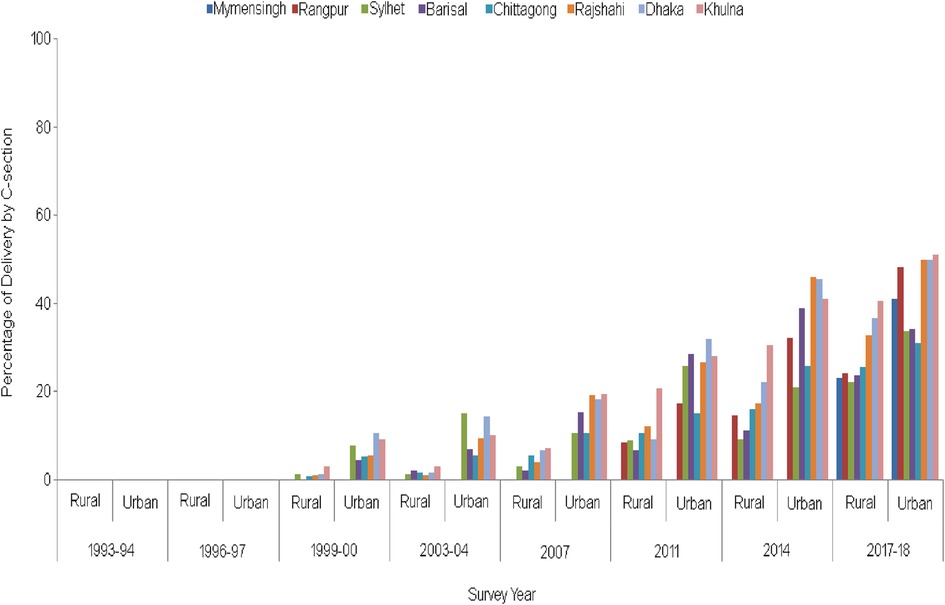

Figure 1 illustrates the percentage of delivery by CS in Bangladesh's urban and rural areas between the survey years 1993 and 2018. CS deliveries in urban areas are more common than in rural areas for all survey years. It is interesting to observe that no CS deliveries are reported in both areas between 1993 and 1996. However, after 1996, the percentage of such deliveries increases gradually from 0% in 1996 to approximately 43% in 2018 in urban areas. On the other hand, it is found that CS deliveries in rural areas slowly increase from 0% in 1996 to approximately 5% in 2007. Then, it increases sharply from approximately 5% in 2007 to approximately 28% in 2018. The overall trend is upward in both urban and rural areas of Bangladesh, but there is a significant gap between the prevalence of CS deliveries between the respondents’ places of residence.

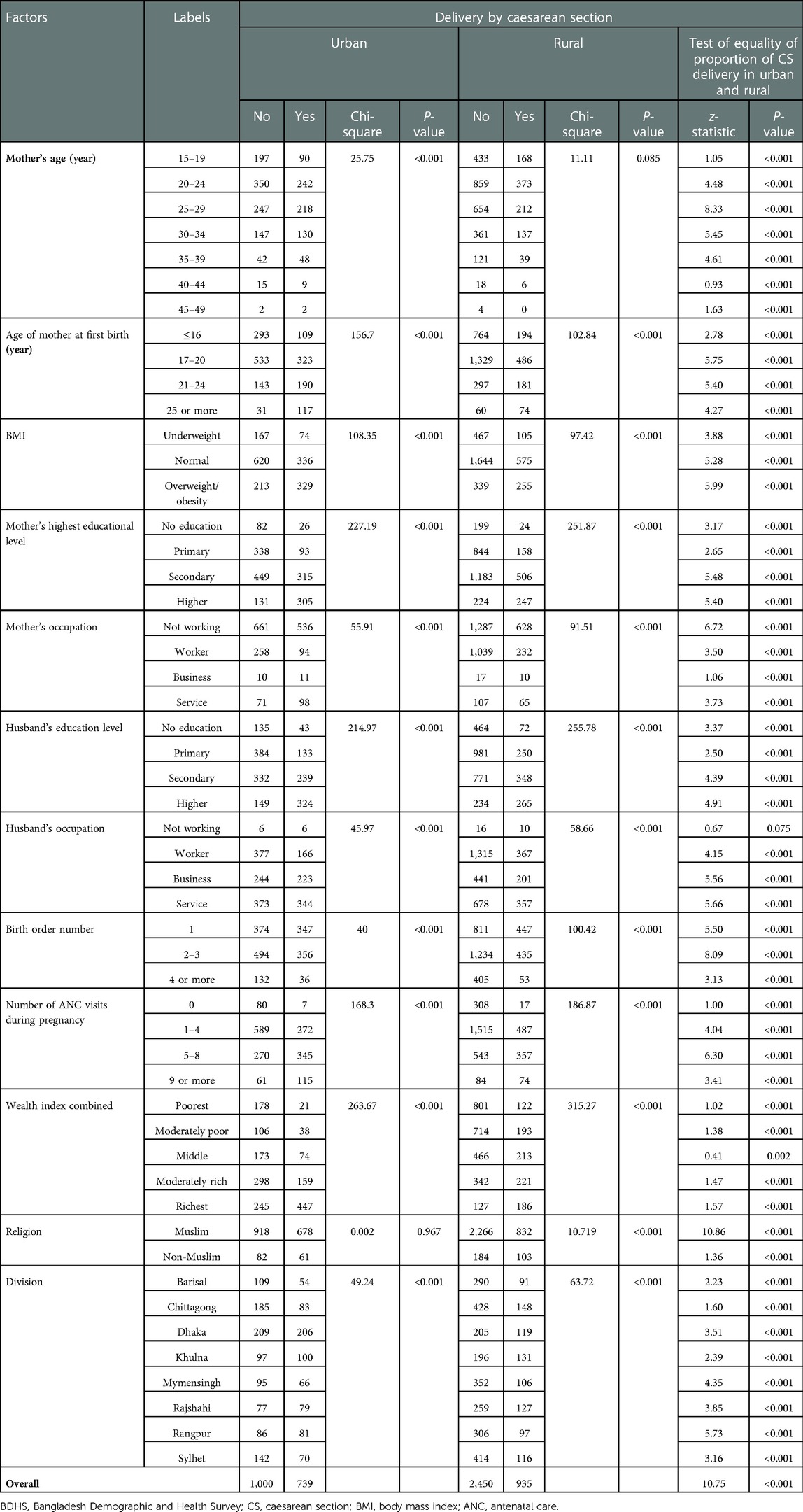

The percentage of delivery by CS based on ever-married women aged 15–49 years, separated by location, namely, rural and urban regions, is presented in Figure 2. We observe that CS deliveries are always higher in urban areas than in rural areas in the country’s geospatial divisions. CS deliveries are the most popular choice in the rural areas of Khulna division for all survey years, followed by Dhaka, Rajshahi, and Chittagong for the last two survey years.

Figure 2. Trends in CS deliveries by division and type of residence from 1993/94 to 2017/18 (note: before 1995, there were only five divisions in Bangladesh, and subsequently, Sylhet, Rangpur, and Mymensingh divisions were added in 1995, 2010, and 2015, respectively).

CS deliveries are widespread in the urban areas of Khulna, Dhaka, and Rajshahi divisions. In contrast, such deliveries are less common in Barisal division's rural and urban areas, followed by the Chittagong division. However, in the Sylhet division, CS was popular initially, but after 2014, the prevalence is less observable. Overall, for the entire survey period, an increasing trend in the percentage of CS is observed in all parts of the country’s urban and rural regions.

The bar chart portrayed in Figure 3, which takes into account the BDHS-2017/18 data, shows the percentage of CS deliveries grouped according to the different reasons for such deliveries in urban and rural areas. Reasons such as convenience, unwilling to bear labor pains, cord prolapse, multiple births, diabetes, previous CS, less pressure on the baby's brain, and other complications during delivery were found to be higher for urban areas than for rural areas. In contrast, reasons such as malpresentation, premature baby, failure to progress in labor, preeclampsia, and broken/dried up water were found to be more in rural areas. Overall, the main reasons for CS were malpresentation (approximately 21% in urban areas and 25% in rural areas), failure to progress in labor ( approximately 23% in urban areas and 24% in rural areas), and previous CS (approximately 25% in urban areas and 21% in rural areas) (Figure 3).

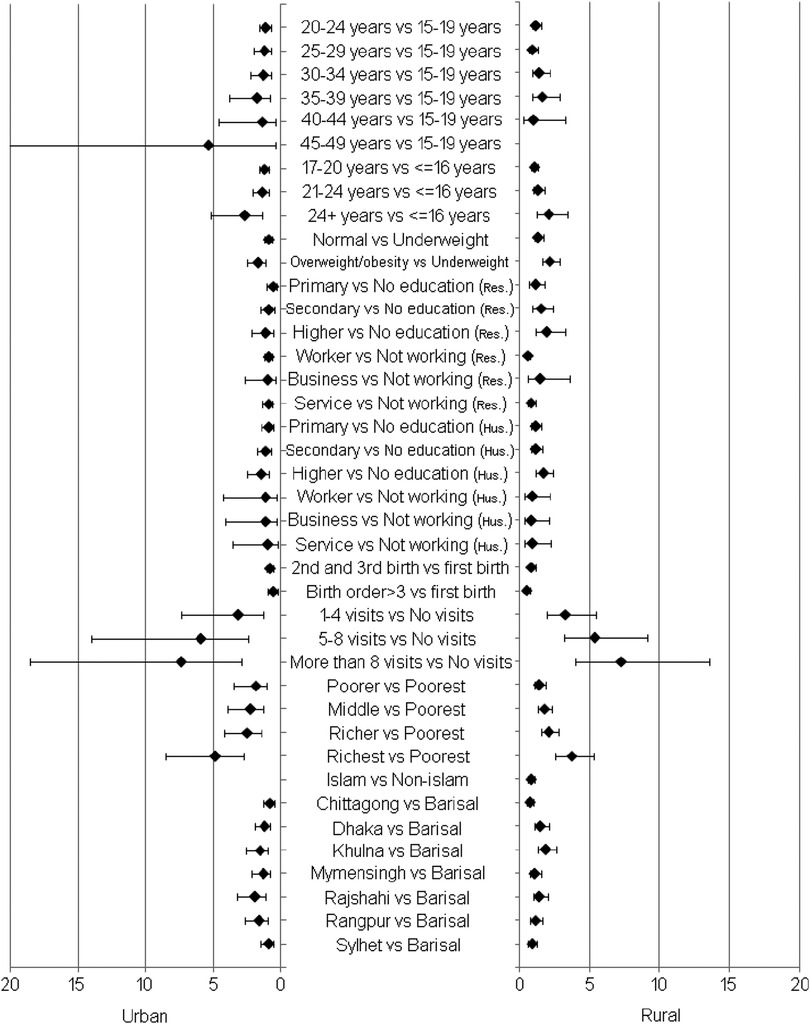

The associations between the prevalence of CS and other sociodemographic, socioeconomic, geographic, and antenatal care (ANC)-related variables were investigated by using the chi-square test, and the results are given in Table 1. Interestingly, it is observed that all the considered covariates influence the prevalence of CS in both urban and rural areas of Bangladesh. Although the mother's age is associated with CS prevalence with a p-value < 0.001 in urban areas, the association is also significant in rural areas with a p-value of 0.085. On the other hand, religion shows a significant association in only rural areas with a p-value of 0.001. Because the difference between the proportions of CS in urban–rural areas can be explicitly visualized, the significance of this difference can also be justified by using the z-test in terms of every covariate considered in this study. The results of the test statistic, along with the p-value, are presented in Table 1. The results demonstrate that the CS delivery rate in urban areas is significantly different from that in rural areas in terms of all covariates. It is fascinating that the observed p-values are less than 0.001 in all levels of the considered variables, except in the wealth index, which is categorized as a middle-class parameter, which denotes that the father does not engage in any work. However, the difference between the two variables of urban and rural areas is also significant, in that there is a 10% level of significance, since the p-values of the wealth index (middle) denoting that the father does not work are 0.002 and 0.075, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Association between mode of birth and socioeconomic and demographic factors of Bangladeshi mothers aged 15–49 years, BDHS-2017/18.

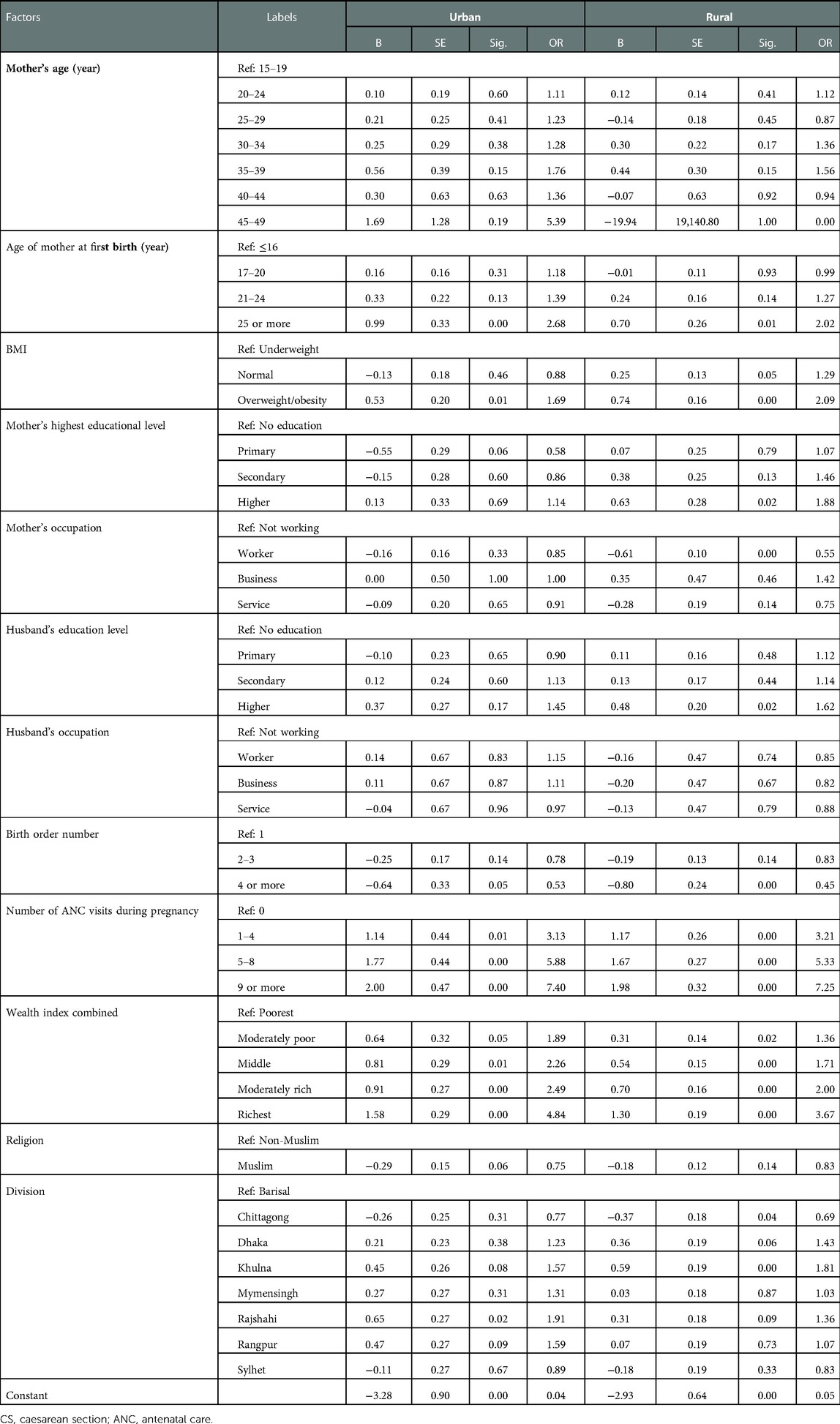

Then, the multivariable logistic regression model with CS as the dependent variable and the identified significant covariates as the independent variables was used to measure the impact of the covariates on CS. The results are presented in Table 2 and Figure 4. The geographical region (Khulna and Rajshahi division) showed a significant association with CS. Mothers who lived in the urban areas of Rajshahi [odds ratio (OR): 1.9] and rural areas of Khulna (OR: 1.8) were significantly more likely to undergo CS compared with those in Barisal. The odds of CS were found higher among better-educated mothers than their less-educated counterparts in both urban and rural areas. Better-educated mothers in rural areas had significantly higher odds (OR: 1.8) of having a CS delivery. Mothers who belonged to higher-wealth quintiles had more odds of undergoing CS in both urban and rural areas, for example, moderately poor (urban: 1.8, rural: 1.3), middle class (urban: 2.2, rural: 1.7), moderately rich (urban: 2.4, rural: 2.0), and richest (urban: 4.8, rural: 3.6). Overweight/obese mothers (BMI > 30) had higher odds of having a CS delivery compared with their underweight counterparts in both urban (OR: 1.6) and rural (OR: 2.0) areas. The odds of obese mothers having a CS delivery, in both urban (OR: 1.6) and rural (OR: 2.0) areas, were significantly higher than those who were underweight (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Forest plot for odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals corresponding to the considered factor's labels in urban versus rural areas.

Table 2. Summary of the logistic regression of CS delivery on the sociodemographic, economic, geographic, and ANC-related factors.

Mothers who received a higher number of antenatal care visits during pregnancy also had higher odds of undergoing CS delivery in both urban and rural areas, for example, 1–4 visits (urban: 3.2, rural: 3.2), 1–4 visits (urban: 5.8, rural: 5.3), and 8 or more (urban: 7.3, rural: 7.2) compared with 0 visits. Rural mothers who were employed had less odds of CS done on them (OR = 0.5) than those who were not. The likelihood of CS deliveries was higher among mothers at first birth in the age group of (24 + years) in urban (OR: 2.6) and rural areas (OR: 2.0) compared with the ≤16 year age group. The possibility of CS decreased with a higher birth order in both urban and rural areas; for example, a birth order of more than 3 in urban (OR = 0.5) and rural areas (OR = 0.4) was lower than that of first birth. The mother's age, religion, and the father’s occupation were not significantly associated with CS deliveries in both areas (Figure 4).

One of the key findings of this study is that the CS delivery rate is continuously increasing over time in urban and rural residents. In a study by Khan et al., it is reported that the prevalence rate of CS has been increasing in Bangladesh over the last few decades (40). However, after a period of 15 years, it is now approximately 11 times that of the first reported rate and nearly three times that of the WHO's recommended ideal rate of 10%–15% in both urban and rural areas of Bangladesh (3). Based on the data up to 2015, the WHO declared that CS rates of more than 10% were not associated with reductions in maternal and new-born mortality rates at the population level (41). The increased rate of CS delivery was associated with different health problems such as an increased risk of postpartum antibiotic use, maternal morbidity and mortality, fetal and neonatal morbidity, placenta accreta, reduced fetal growth, preterm delivery, pelvic pain, adverse reproductive effects, and many more (41). A more than 10% CS rate did not facilitate the provision of health improvement measures for mothers or newborns (42). Therefore, if CS delivery prevalence continues to increase in its current pace, it is highly likely that CS will exercise more harmful impacts at the population level (40). Given the geographical structure of Bangladesh, which is in the form of divisions, CS rates are found to be high in Khulna, followed by Dhaka, Rajshahi, Rangpur, Mymensingh, Chittagong, Barisal, and Sylhet in that order. Interestingly, the pattern of CS delivery practices is similar in Khulna and Dhaka divisions, while Chittagong and Barisal divisions closely follow. Similar findings were reported in 2013 (43).

Nevertheless, CS deliveries are increasing in both areas, but in urban areas, the popular appeal of such deliveries is more than two times that in rural areas over the past decade, and it was much higher in the previous decade. These findings indicate that a large number of urban mothers prefer CS compared with their rural counterparts. Many studies have identified urbanization as a significant contributing factor to CS practices in several countries (27, 30, 42, 44–51). The prevalence of CS has been increasing in urban areas over several decades in low- and middle-income countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America (27, 42, 47–51). A retrospective study was conducted to analyze data from demographic and health surveys, and it reported a rising CS trend in Pakistan’s urban areas compared with the rural areas (52). The CS rate has continuously increased over the years in Vietnam's urban area, which is similar to the trend observed in low- to middle-income countries like Bangladesh (53). However, the urban–rural divide is visible in every division in Bangladesh. The differences in CS delivery in urban and rural areas are multifactorial and complex in nature (40). Nonetheless, it is evident from previous studies that this urban–rural divide reflects the presence of different socioeconomic, demographic, and healthcare factors such as higher income and education level, easy accessibility to healthcare facilities, and easy availability of government, private, and non-government medical facilities for the antenatal care of pregnant mothers (43, 53, 54). In one study, it is mentioned that cultural, educational, and economic differences across areas might be the foremost reasons for region-wise variations in CS (55).

Another finding shows that “other complications during delivery (31.9%)” is the leading indication for CS, followed by malpresentation (23.4%), failure to progress in labor (23.2%), previous CS (22.9%), convenience (9.3%), and unwillingness to bear labor pain (6%). A study conducted in the Thakurgaon district of Bangladesh reported that the most typical indications for CS were previous CS (29.4%), fetal distress (15.7%), cephalopelvic disc proportion (10.2%), prolonged obstructed labor (8.3%), and post-term dates (7.0%) (46). Another study conducted in the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR, B) service area in Bangladesh found that common indications for CS were absence of maternal complications (24.9%), absolute maternal indications (24.7%), failure to progress (16.5%), and no clear medical indication (12.5%) in a total of 401 CS deliveries (56). Fetal distress, preeclampsia, and cervical dystocia were identified as the most common CS indicators in Bangladesh’s urban areas (57). Moreover, fetal distress, previous CS, breech presentation, and slow progress in labor were the most familiar indicators for CS in Nepal (58). The WHO estimated that about one-third of the total CS deliveries were done without medical symptoms described as “unnecessary” (45).

These findings also indicate that the pregnant mother's age, age at first birth, BMI, education, occupation of the mother and her partner, birth order, ANC visits, wealth index, and geographic region (division) are the significant leading factors of CS deliveries in both urban and rural areas. Interestingly, religion is a significant leading factor of CS in rural areas. The factors mentioned above were also identified as potential significant predictors of CS deliveries in many previous studies (4, 25, 31, 32, 40, 53–55). Moreover, these results also indicate that the identified significant leading factors do not uniformly influence CS delivery prevalence in urban and rural areas. It has been reported that the cultural, educational, and economic differences across areas are the main reasons for the regional variations in CS deliveries (55).

Moreover, this study measured the risk of pregnant mothers’ CS deliveries from a different viewpoint of the significant leading factors. It found that older mothers were more likely to experience different complications during pregnancy and delivery (23, 25, 59–61), which increased the likelihood of CS delivery. These findings are similar to our results from urban areas; however, we observe different results in rural areas. As with previous findings (54, 62), this study also found a higher likelihood of CS delivery among mothers who were obese and aged 24 or more at first birth, and the chances of CS decreased with a higher birth order. We found that mothers preferred CS because of the increased risk of complications in other deliveries. Urban mothers aged 24 or more at first birth had a greater possibility of undergoing CS than their rural counterparts, while obese mothers in rural areas had a higher possibility of undergoing CS than urban mothers.

Our findings indicate that mothers with higher education are more likely to undergo CS. This finding is similar to previous studies’ results (40, 54, 55). A better-educated rural mother has a higher likelihood of undergoing CS than her urban-educated counterpart, but the exact reason for this is not clear from this study. Furthermore, this study found that CS delivery and birth order were inversely related in both urban and rural areas. A similar result was identified in many previous studies (43, 54, 63). In addition, mothers living in households with higher socioeconomic status and those who received higher ANC visits during pregnancy were more likely to opt for CS. Our findings are consistent with those of earlier studies that also explored the influence of maternal education, wealth status, and ANC visits on the use of maternity care services, especially CS delivery (4, 54, 64). Higher-educated and wealthiest mothers plumped for CS deliveries because they had a higher ability to pay (62) to receive specialized care (4). The influence of both factors (ANC visits and wealth index) on CS was higher in urban than in rural areas. In a study, data collected from 80 demographic and health surveys from 26 countries in Southern Asia or sub-Saharan Africa were analyzed, and it was found that the wealthiest urban mothers were more likely to undergo CS than the wealthiest rural mothers (30).

Furthermore, mothers whose husbands are also better educated are more likely to accept CS than those whose husbands are less educated, with the likelihood being slightly greater in urban areas. Working mothers are the least likely to opt for CS compared to non-working mothers in both areas. This may be due to the fact that working mothers have less chances of receiving ANC services because of time constraints (65). Likewise, Muslim mothers are less likely to undergo CS deliveries compared with non-Muslim mothers in urban and rural areas. This finding is consistent with that of a previous study, which reported that Muslim mothers have less opportunities to avail of ANC services due to their religious beliefs and the restrictions imposed by their husbands on the breach of privacy (66). Mothers whose husbands are employed in rural areas are less likely to undergo CS, but those whose husbands are professionals or businessmen in urban areas are more likely to undergo CS. Compared with mothers in Barisal division, those in Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, and Rangpur divisions have a greater likelihood of having CS, while mothers in Chittagong and Sylhet divisions are less likely to have CS in both urban and rural areas. Also, urban mothers are more likely to undergo CS than rural mothers in Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, and Rangpur. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies (43, 40). However, these findings are quite alarming for a low- and middle-income country like Bangladesh (4, 54, 64), because the situation can place a heavy financial burden on the healthcare system and family economic status in the country (4). Furthermore, due to the lack of a robust quality control system, there is a possibility that hospitals/clinics in Bangladesh may aim for profit maximization, and similar settings in other countries may produce similar results (4).

The main strength of this study is its novelty. Second, this study was carried out with country representative data. Third, methodological robustness increased the acceptability of the findings. The main limitation of this study is that it was conducted with cross-sectional data, and therefore, causal inferences could not be derived. Second, there may be other contributing factors to CS delivery that were not considered in this study.

The increasing trends in CS deliveries in urban areas is approximately two- to sixfold higher than in rural areas between the years 1993 and 1994 and between 2017 and 2018, and this indicates an undesirable situation in the context of Bangladeshi healthcare. Many factors have already been identified previously for the increasing number of CS deliveries in the country. However, this study focused on the urban–rural variations in CS deliveries. It is suggested that policymakers should design community-based maternal healthcare programs to reduce the prevalence rates of CS and also the economic burden placed on both urban and rural settings in light of the findings of this research.

This study has been conducted in the urban and rural areas of Bangladesh with the principal aim of examining the CS delivery pattern over time and to identify its causes and influential factors. The trend analysis showed that CS delivery prevalence has increased over the past two decades in both areas with apparent differences. Moreover, the increasing trends and the urban–rural divide have also manifested in Bangladesh's geographic divisions. Furthermore, extraneous complications during delivery have been the leading indications for CS, followed by malpresentation, failure to progress in labor, previous CS, convenience, and unwillingness to bear labor pain in both urban and rural areas, however, with a slight difference. However, among these causative factors, CS delivery due to only malpresentation is higher in rural areas than in urban areas, while the prevalence of the remaining factors is higher in urban areas. The analysis confirmed that CS delivery is significantly influenced by the pregnant mother's age, age at first birth, BMI, education, occupation of both mother and husband, birth order, ANC visits, wealth index, and geographic division in both urban and rural areas; religion is an important covariate in rural areas. These findings reveal that the aforementioned influential factors of CS vary in terms of the resident settings (urban or rural) of pregnant mothers.

This study found that urban mothers were more likely to undergo CS deliveries than their rural counterparts. This was mainly the case of those who were more than 19 years old, overweight, had higher education levels, received more than one ANC visit, were aged greater than 16 years at first birth and whose husbands were secondary or higher educated and professionals or businessmen, and lived in wealthy households in Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, and Rangpur divisions. On the other hand, mothers with age between 20 and 39 years, age at first birth >20 years, normal or overweight, received primary to higher education, business professionals, whose husbands were also primary to higher educated, received more than one ANC visit, and belonged to wealthy families in Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, and Rangpur divisions were more likely to undergo CS deliveries in rural areas. However, the increasing practice of CS delivery is posing a threat to traditional and normal deliveries, and for a low- and middle-income country like Bangladesh, CS can place a heavy financial burden on the healthcare system and family economic status. Therefore, the government of Bangladesh needs to act fast by developing new policies and regulations to make sure that CS is carried out only when it is medically appropriate to do so and not for the sole purpose of deriving financial benefits.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These can be found in https://dhsprogram.com.

This study was based on the public domain survey data sets that are freely available online with all identifier information removed. These surveys were initially approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) at ICF and the Bangladesh Medical Research Council (BMRC). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Conceptualization was done by FA, MMH, and AR. Data processing and formal analysis were done by FA and MMH. Visualization was done by FA. Supervision was carried out by MMH and AR. Writing of the original draft was done by FA, MMH, MMR, and MSR. Writing—reviewing and editing—were executed by FA, MMH, MMR, MSR, and AR. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Ji H, Jiang H, Yang L, Qian X, Tang S. Factors contributing to the rapid rise of caesarean section: a prospective study of primiparous Chinese women in Shanghai. BMJ Open. (2015) 5:e008994. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008994

2. Betran AP, Torloni MR, Zhang JJ, Gülmezoglu AM. WHO statement on caesarean section rates. BJOG. (2016) 123:667–70. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13526

3. Sandall J, Tribe RM, Avery L, Mola G, Visser GHA, Homer CSE, et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet. (2018) 392:1349–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31930-5

4. Mia MN, Islam MZ, Chowdhury MR, Razzaque A, Chin B, Rahman MS. Socio-demographic, health and institutional determinants of caesarean section among the poorest segment of the urban population: evidence from selected slums in Dhaka, Bangladesh. SSM Popul Health. (2019) 8:100415. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100415

5. Menacker F, Declercq E, Macdorman MF. caesarean delivery: background, trends, and epidemiology. Semin Perinatol. (2006) 30:235–41. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.07.002

6. Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Gülmezoglu AM, Souza JP, Taneepanichskul S, Ruyan P, et al. Method of delivery and pregnancy outcomes in Asia: the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health 2007-08. Lancet. (2010) 375:490–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61870-5

7. Souza JP, Gülmezoglu AM, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Carroli G, Fawole B, et al. caesarean section without medical indications is associated with an increased risk of adverse short-term maternal outcomes: the 2004-2008 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health. BMC Med. (2010) 8:71. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-71

8. Niino Y. The increasing caesarean rate globally and what we can do about it. Biosci Trends. (2011) 5:139–50. doi: 10.5582/bst.2011.v5.4.139

9. Allen VM, O’Connell CM, Farrell SA, Baskett TF. Economic implications of method of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2005) 193:192–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.635

10. MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Menacker F, Malloy MH. Neonatal mortality for primary caesarean and vaginal births to low-risk women: application of an “intention-to-treat” model. Birth. (2008) 35:3–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00205.x

11. Robson M, Hartigan L, Murphy M. Methods of achieving and maintaining an appropriate caesarean section rate. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. (2013) 27:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.09.004

12. Thompson JF, Roberts CL, Currie M, Ellwood DA. Prevalence and persistence of health problems after childbirth: associations with parity and method of birth. Birth. (2002) 29:83–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536X.2002.00167.x

13. Declercq E, Barger M, Cabral HJ, Evans SR, Kotelchuck M, Simon C, et al. Maternal outcomes associated with planned primary caesarean births compared with planned vaginal births. Obstet Gynecol. (2007) 109:669–77. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000255668.20639.40

14. Liu S, Liston RM, Joseph KS, Heaman M, Sauve R, Kramer MS. Maternal mortality and severe morbidity associated with low-risk planned caesarean delivery versus planned vaginal delivery at term. Can Med Assoc J. (2007) 176:455–60. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060870

15. Sanchez-Ramos L, Wells TL, Adair CD, Arcelin G, Kaunitz AM, Wells DS. Route of breech delivery and maternal and neonatal outcomes. Int J Gynecol Obstet. (2001) 73:7–14. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(00)00384-2

16. Silver RM. Implications of the first caesarean: perinatal and future reproductive health and subsequent caesareans, placentation issues, uterine rupture risk, morbidity, and mortality. Semin Perinatol. (2012) 36:315–23. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2012.04.013

17. National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) and ICF. Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2017-18. Dhaka (2020). Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR344/FR344.pdf. (Accessed date: 24 December 2021)

18. Cohen WR. Does maternal age affect pregnancy outcome?. BJOG. (2014) 121:252–4. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12563

19. Liston W. Rising caesarean section rates: can evolution and ecology explain some of the difficulties of modern childbirth? J R Soc Med. (2003) 96:559–61. doi: 10.1177/014107680309601117

20. Nour NM. Health consequences of child marriage in Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. (2006) 12:1644–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060510

21. Joffe M, Hall MH. Variation in caesarean section rates what difference does it make? Br Med J. (1994) 308:654. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6929.654

22. Gould JB, Davey B, Stafford RS. Socioeconomic differences in rates of caesarean section. N Engl J Med. (1989) 321:233–9. doi: 10.1056/nejm198907273210406

23. Padmadas SS, Kumar SS, Nair SB, Anitha Kumari KR. caesarean section delivery in Kerala, India: evidence from a national family health survey. Soc Sci Med. (2000) 51:511–21. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00491-8

24. Potter JE, Berquó E, Perpétuo IHO, Leal OF, Hopkins K, Souza MR, et al. Unwanted caesarean sections among public and private patients in Brazil: prospective study. Br Med J. (2001) 323:1155–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7322.1155

25. Mishra US, Ramanathan M. Delivery-related complications and determinants of caesarean section rates in India. Health Policy Plan. (2002) 17:90–8. doi: 10.1093/heapol/17.1.90

26. Sufang G, Padmadas SS, Fengmin Z, Brown JJ, William Stones R. Delivery settings and caesarean section rates in China. Bull World Health Organ. (2007) 80:755–62. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.035808

27. Al Rifai RH. Trend of caesarean deliveries in Egypt and its associated factors: evidence from national surveys, 2005-2014. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2017) 17:417. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1591-2

28. Milcent C, Zbiri S. Prenatal care and socioeconomic status: effect on caesarean delivery. Health Econ Rev. (2018) 8:7. doi: 10.1186/s13561-018-0190-x

29. Betrán AP, Merialdi M, Lauer JA, Bing-Shun W, Thomas J, Van Look P, et al. Rates of caesarean section: analysis of global, regional and national estimates. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. (2007) 21:98–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00786.x

30. Cavallaro FL, Cresswell JA, França GV, Victora CG, Barros AJ, Ronsmans C. Trends in caesarean delivery by country and wealth quintile: cross-sectional surveys in southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Bull World Health Organ. (2013) 91:914–22D. doi: 10.2471/blt.13.117598

31. Verma V, Vishwakarma RK, Nath DC, Khan HTA, Prakash R, Abid O. Prevalence and determinants of caesarean section in south and south-east Asian women. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0229906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229906

32. Kumar P, Dhillon P. Household- and community-level determinants of low-risk caesarean deliveries among women in India. J Biosoc Sci. (2021) 53:55–70. doi: 10.1017/S0021932020000024

33. Ajeet S, Nandkishore K. The boom in unnecessary caesarean surgeries is jeopardizing women's health. Health Care Women Int. (2013) 34:513–21. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2012.721416

34. Hoxha I, Syrogiannouli L, Luta X, Tal K, Goodman DC, Da Costa BR, et al. caesarean sections and for-profit status of hospitals: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e013670. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013670

35. Radhakrishnan T, Vasanthakumari K, Babu P. Increasing trend of caesarean rates in India: evidence from NFHS-4. J Med Sci Clin Res. (2017) 5:26167–76. doi: 10.18535/jmscr/v5i8.31

36. Lin HC, Xirasagar S. Institutional factors in caesarean delivery rates: policy and research implications. Obstet Gynecol. (2004) 103:128–36. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000102935.91389.53

37. Milcent C, Rochut J. Hospital payment system and medical practice. caesarean births in France. Rev Écon. (2009) 60:489–506. doi: 10.3917/reco.602.0489

38. Epstein AJ, Nicholson S. The formation and evolution of physician treatment styles: an application to caesarean sections. J Health Econ. (2009) 28:1126–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.08.003

39. Grant D. Physician financial incentives and caesarean delivery: new conclusions from the healthcare cost and utilization project. J Health Econ. (2009) 28:244–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.09.005

40. Khan MN, Islam MM, Shariff AA, Alam MM, Rahman MM. Socio-demographic predictors and average annual rates of caesarean section in Bangladesh between 2004 and 2014. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0177579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177579

41. Hu HT, Xu JJ, Lin J, Li C, Wu YT, Sheng JZ, et al. Association between first caesarean delivery and adverse outcomes in subsequent pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2018) 18:273. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1895-x

42. Souza JP, Betran AP, Dumont A, De Mucio B, Gibbs Pickens CM, Deneux-Tharaux C, et al. A global reference for caesarean section rates (C-model): a multicountry cross-sectional study. BJOG. (2016) 123:427–36. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13509

43. Kamal SM. Preference for institutional delivery and caesarean sections in Bangladesh. J Heal Popul Nutr. (2013) 31:96–109. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v31i1.14754

44. Stanton CK, Holtz SA. Levels and trends in caesarean birth in the developing world. Stud Fam Plann. (2006) 37:41–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2006.00082.x

45. Gibbons L, Belizán JM, Lauer JA, Betrán AP, Merialdi M, Althabe F. The global numbers and costs of additionally needed and unnecessary caesarean sections performed per year: overuse as a barrier to universal coverage. World Health Report 2010 (2010) 30. Available at: https://pureportal.strath.ac.uk/en/publications/the-global-numbers-and-costs-of-additionally-needed-and-unnecessa#:∼:text=The%%20cost%20of%20the%20global%20%E2%80%9Cexcess%E2%80%9D%20CS%20was,command%20a%20disproportionate%20share%20of%20global%20economic%20resources. (Accessed date: 14 January 2022)

46. Aminu M, Utz B, Halim A, van den Broek N. Reasons for performing a caesarean section in public hospitals in rural Bangladesh. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2014) 14:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-130

47. Diamond-Smith N, Sudhinaraset M. Drivers of facility deliveries in Africa and Asia: regional analyses using the demographic and health surveys. Reprod Health. (2015) 12:6. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-12-6

48. Kaboré C, Ridde V, Kouanda S, Agier I, Queuille L, Dumont A. Determinants of non-medically indicated caesarean deliveries in Burkina Faso. Int J Gynecol Obstet. (2016) 135:S58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.08.019

49. Khanal V, Karkee R, Lee AH, Binns CW. Adverse obstetric symptoms and rural-urban difference in caesarean delivery in Rupandehi district, Western Nepal: a cohort study. Reprod Health. (2016) 13:17. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0128-x

50. Boatin AA, Schlotheuber A, Betran AP, Moller AB, Barros AJD, Boerma T, et al. Within country inequalities in caesarean section rates: observational study of 72 low and middle income countries. Br Med J. (2018) 360:k55. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k55

51. Yisma E, Smithers LG, Lynch JW, Mol BW. caesarean section in Ethiopia: prevalence and sociodemographic characteristics. J Matern Neonatal Med. (2019) 32:1130–5. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1401606

52. Nazir S. (2015). Determinants of caesarean deliveries in Pakistan. PIDE Working Papers No. 122. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics. Available at: https://www.pide.org.pk/pdf/Working%20Paper/WorkingPaper-122.pdf. (Accessed date: 12 January 2022)

53. de Loenzien M, Schantz C, Luu BN, Dumont A. Magnitude and correlates of caesarean section in urban and rural areas: a multivariate study in Vietnam. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0213129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213129

54. Rahman MM, Haider MR, Moinuddin M, Rahman AE, Ahmed S, Mahmud Khan M. Determinants of caesarean section in Bangladesh: cross-sectional analysis of Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2014 data. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0202879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202879

55. Hasan F, Alam MM, Hossain MG. Associated factors and their individual contributions to caesarean delivery among married women in Bangladesh: analysis of Bangladesh demographic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2019) 19:433. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2588-9

56. Huda FA, Ahmed A, Dasgupta SK, Jahan M, Ferdous J, Koblinsky M, et al. Profile of maternal and foetal complications during labour and delivery among women giving birth in hospitals in Matlab and Chandpur. Bangladesh J Heal Popul Nutr. (2012) 30:131–42. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v30i2.11295

57. Saha L, Chowdhury SB. Study on primary caesarean section. Mymensingh Med. J. (2011) 20:292–7.21522103

58. Khanal R. caesarean delivery at Nepal medical college teaching hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. (2004) 6:53–5.15449656

59. Webster LA, Daling JR, Mcfarlane C, Ashley D, Warren CW. Prevalence and determinants of caesarean section in Jamaica. J Biosoc Sci. (1992) 24:15–25. doi: 10.1017/S0021932000020071

60. Bell JS, Campbell DM, Graham WJ, Penney GC, Ryan M, Hall MH. Do obstetric complications explain high caesarean section rates among women over 30? A retrospective analysis. Br Med J. (2001) 322:894–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7291.894

61. Esteves-Pereira AP, Deneux-Tharaux C, Nakamura-Pereira M, Saucedo M, Bouvier-Colle MH, Do Carmo Leal M. caesarean delivery and postpartum maternal mortality: a population-based case control study in Brazil. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0153396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153396

62. Neumann K, Indorf I, Härtel C, Cirkel C, Rody A, Beyer DA. C-section prevalence among obese mothers and neonatal hypoglycemia: a cohort analysis of the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics of the University of Lübeck. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. (2017) 77:487–94. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-108763

63. Amjad A, Amjad U, Zakar R, Usman A, Zakar MZ, Fischer F. Factors associated with caesarean deliveries among child-bearing women in Pakistan: secondary analysis of data from the demographic and health survey, 2012-13. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2018) 18:113. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1743-z

64. Faisal-Cury A, Menezes PR. Factors associated with preference for caesarean delivery. Rev Saude Publica. (2006) 40:226–32. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102006000200007

Keywords: C-section, prevalence, BDHS, logistic regression, Bangladesh

Citation: Abdulla F, Hossain MM, Rahman MM, Rahman MS and Rahman A (2023) Risk factors of caesarean deliveries in urban–rural areas of Bangladesh. Front. Reprod. Health 5:1101400. doi: 10.3389/frph.2023.1101400

Received: 1 December 2022; Accepted: 9 January 2023;

Published: 15 February 2023.

Edited by:

Singh Rajender, Central Drug Research Institute (CSIR), IndiaReviewed by:

Mohamed Farghali, Ain Shams University, Egypt© 2023 Abdulla, Hossain, Rahman, Rahman and Rahman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Faruq Abdulla ZmFydXFpdXN0YXQwOW1uaWxAZ21haWwuY29t Md. Moyazzem Hossain aG9zc2Fpbm1tQGp1bml2LmVkdQ==

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Reproductive Epidemiology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Reproductive Health

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.