- 1Centre for Community-Based Research, Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria, South Africa

- 2Psychology Department, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa

- 3Impact Centre, Human Sciences Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa

Availability of and access to services that promote sexual and reproductive health (SRH) amongst adolescent girls have become a global priority. Yet, while researchers have explored factors that influence the uptake of SRH services in low-and-middle income countries, the roles that “agency” and “hope” play in adolescent SRH is less understood. To study this, this mini review systematically reviewed the literature across three databases, EBSCO-host web, Pubmed and South Africa (SA) epublications, for the period of January 2012 to January 2022. Findings showed that a paucity of studies identified the link between agency, hope and adolescent SRH respectively. Our review included 12 articles and found no studies that focused on hope and its role in adolescent SRH or seeking SRH services. However, the literature revealed the complexities of adolescent SRH agency and autonomy where female adolescents had limited autonomy to make SRH decisions. Limited access to adolescent friendly SRH services was also found to restrict girls' agency to prevent unintended pregnancies or to take up SRH support. Given the paucity of research, empirical studies are needed to further understand the extent to which hope, agency and other subjective factors implicate adolescent SRH in the African context.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, there has been growing interest in the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) of adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) who have been identified as a particularly vulnerable group (1, 2). Adolescents are young people between the ages of 10 and 19 who experience socio-developmental transformations as they transition into adulthood (3, 4). These transformations are often associated with decision-making, establishing a social identity and self-concept, forming interpersonal relationships and physical changes in the body through puberty (4). Adolescent SRH relates to the freedom and rights that young people have to live healthy lives that are characterised by access to information, services, programmes and support that prevent, interrupt and/or address individual, social and systemic practices that put adolescents at risk of sexual violence, unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections and/or unsafe abortions (5). It also prioritises freedom of choice in accessing these services (6) and, in this way, challenges broader socio-cultural, religious and systemic practices that restrict access to SRH information and services.

While there have been remarkable improvements in the promotion of SRH knowledge and access to SRH services, globally, these gains have been inequitable in low-and-middle-income countries where the access, availability and quality of services have been inadequate (6). This is particularly evident in African countries where AGYW experience poverty and limited resources, gender inequality, gender-based violence and genital mutilation which significantly hinder access to and uptake of SRH services (7). Recent literature further indicates that adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) endure the highest burden of adverse SRH outcomes, where adolescent girls account for the largest number of new HIV-infections in East and SSA (8). More alarming is that women make up 72% of all young persons living with HIV in SSA while the global proportion of this cohort is lower at about 60% (9). It is therefore imperative to understand the factors that influence SRH amongst AGYW in African communities, to ensure that they have access to the highest attainable standard of health (10) and have knowledge and awareness of SRH information and their rights and agency to make informed SRH decisions.

Agency, hope and adolescent SRH

This paper is concerned with the roles that agency and hope plays in the SRH of adolescents including accessing SRH services. Current SRH studies and programs have largely been directed towards enhancing AGYW's SRH knowledge and access to quality services, with a growing need to explore informed decision-making around their SRH (9). Agency refers to “the power to originate action” (11) and is often described as an ability that develops as we reflexively engage with social systems (12). According to Banerjee et al. (13), agency entails the ability to make strategic life choices through personal competence and self-efficacy. It implies a belief that the individual has the potential to direct a sequence of events that make the sum of lived experience. Pertaining to SRH, Vanwesenbeeck, and colleagues (14) uses the term sexual agency which describes young women's ability to make sexual choices, including initiating sex. Banerjee et al. (13) argues that a lack of SRH knowledge and information, and limited agency to negotiate sexual encounters contribute to early and unprotected sex for youth. Adolescents require agency to make health-related decisions, to access health services and to decide whether and when to engage in sexual relations and contraception (13). Social norms and community support enhance adolescents' agency and empower adolescent girls to make decisions in favour of their health such as postponing early marriage and their first childbirth as well as accessing SRH information and services (15). However, in SSA, young adolescents may have a general awareness about sexual and reproductive health matters, but lack in-depth knowledge to sufficiently protect themselves from sexual risks (16). Thus, Vanwesenbeeck et al. argue that agency is multifaceted and that the constructions of SRH agency need to consider the various contextual factors that limit adolescents decision-making (14).

Closely linked to agency, increasing attention has been given to the extent to which having hope shapes adolescent wellbeing (17–19). Hope is defined as an individual's “perceived capability to derive pathways to desired goals and motivate oneself via agency thinking to use those pathways” (18). Hope is the driver of agency, implicating the possibility to act necessary for the self-actualization of a goal. Studies have associated higher levels of hope with more positive outcomes in young people, including enhanced self-esteem, self-worth and self-care agency (19, 20). Hope has also been linked to decision-making and risk behaviours where adolescents have described young people who misused substances as having “no hope” (21) or associated hopelessness with engagement in adverse behaviours (17). Furthermore, hopelessness and other mental health indicators have been related to SRH amongst adolescents. A recent systematic review on the intersection between mental health and SRH amongst AGYW (22) shows that feelings of hopelessness, depression and diminished self-esteem have a bi-directional influence on young women's SRH. For example, unexpected pregnancies were associated with increased distress, hopelessness and depression while teenage pregnancy was identified as an emotional burden and linked to poor mental health (22). Diminished self-esteem was related to a lack of supportive environments and also described by young women as an outcome of controlling and violent sexual relationships (22).

While studies have examined the roles of hope and/or agency in adolescent health behaviour and outcomes, little is known about how these constructs intersect with adolescents' SRH practices in the African context. To study this, we conducted a systematic search of the literature, using set criteria, to identify published studies conducted in Africa on these topics. This mini review thus synthesises the identified literature to explore how these subjective factors influence adolescents' SRH and access to SRH services.

Review approach

This mini-review consulted three databases, namely, EBSCO-host web, SA epublications and Pubmed, making use of Boolean phrase options within databases. The first set of keywords used were “agency” OR “autonomy” OR “self determination” OR “self esteem” OR “self concept” AND “adolescents” OR “teenagers” OR “teen” OR “youth” AND “sexual reproductive health” OR “sexual reproductive health services” AND “Africa”. Apart from the term “Africa”, only articles with the respective keywords in the abstracts were deemed relevant. This strict criterion was applied to ensure that we identify articles that directly link to our interest area and, in this way, avoid articles that merely mention the respective keywords in the body of the text. This search produced the following, EBSCO-host web (n = 455), SA epublications (n = 25), and Pubmed (n = 36). The second keyword search were “hope” OR “hopefulness” OR “self efficacy” AND “adolescents” OR “teenagers” OR “teen” OR “youth” AND “sexual reproductive health” OR “sexual reproductive health services” AND “Africa”. This search produced the following, EBSCO-host web (n = 18), SA epublications (n = 8), and Pubmed (n = 124).

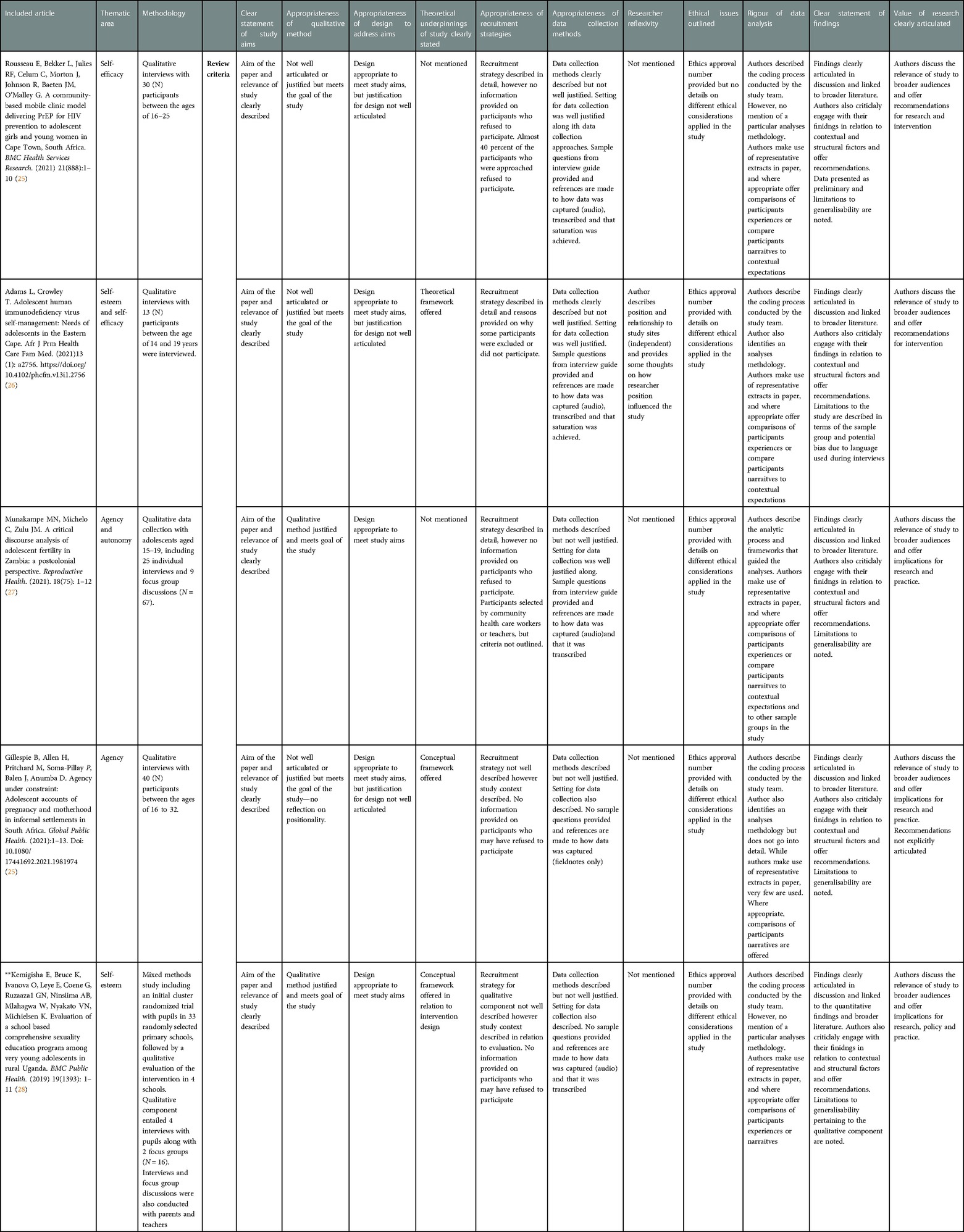

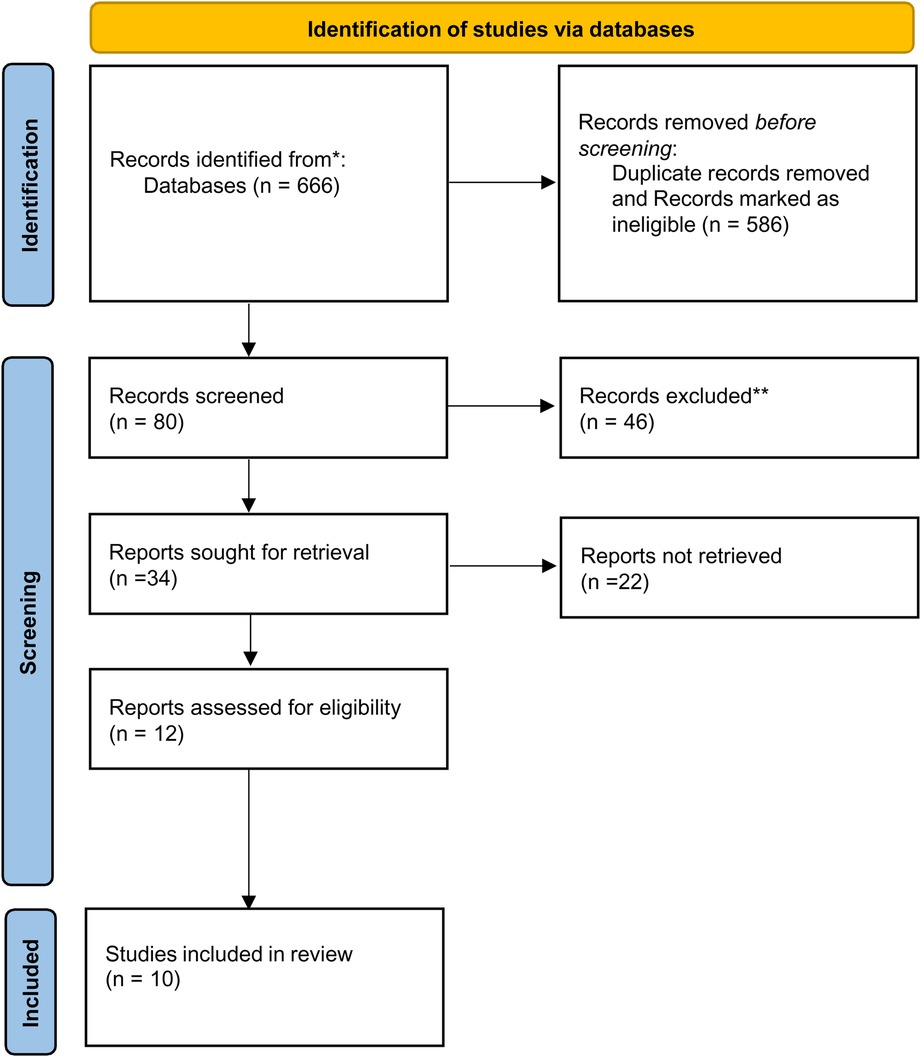

Following this initial search, we conducted an abstract level assessment based on the inclusion criteria such as the timeline (i.e., January 2012 to June 2022), only peer-reviewed articles, English language, and studies including empirical data. The three reviewers used these criteria, together with the primary objective that only articles that relate to the link between hope and SRH (including services) or agency and SRH (including services), to assess the relevance of each abstract and whether it was included or excluded. After the abstract assessment, 34 articles were selected for full text assessment. Full text articles were independently assessed by three authors for methodological rigor and to avoid bias (see Figure 1). The final review included a total of (n = 10) articles (See Appendix A).

Figure 1. Prisma diagram to screen articles. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

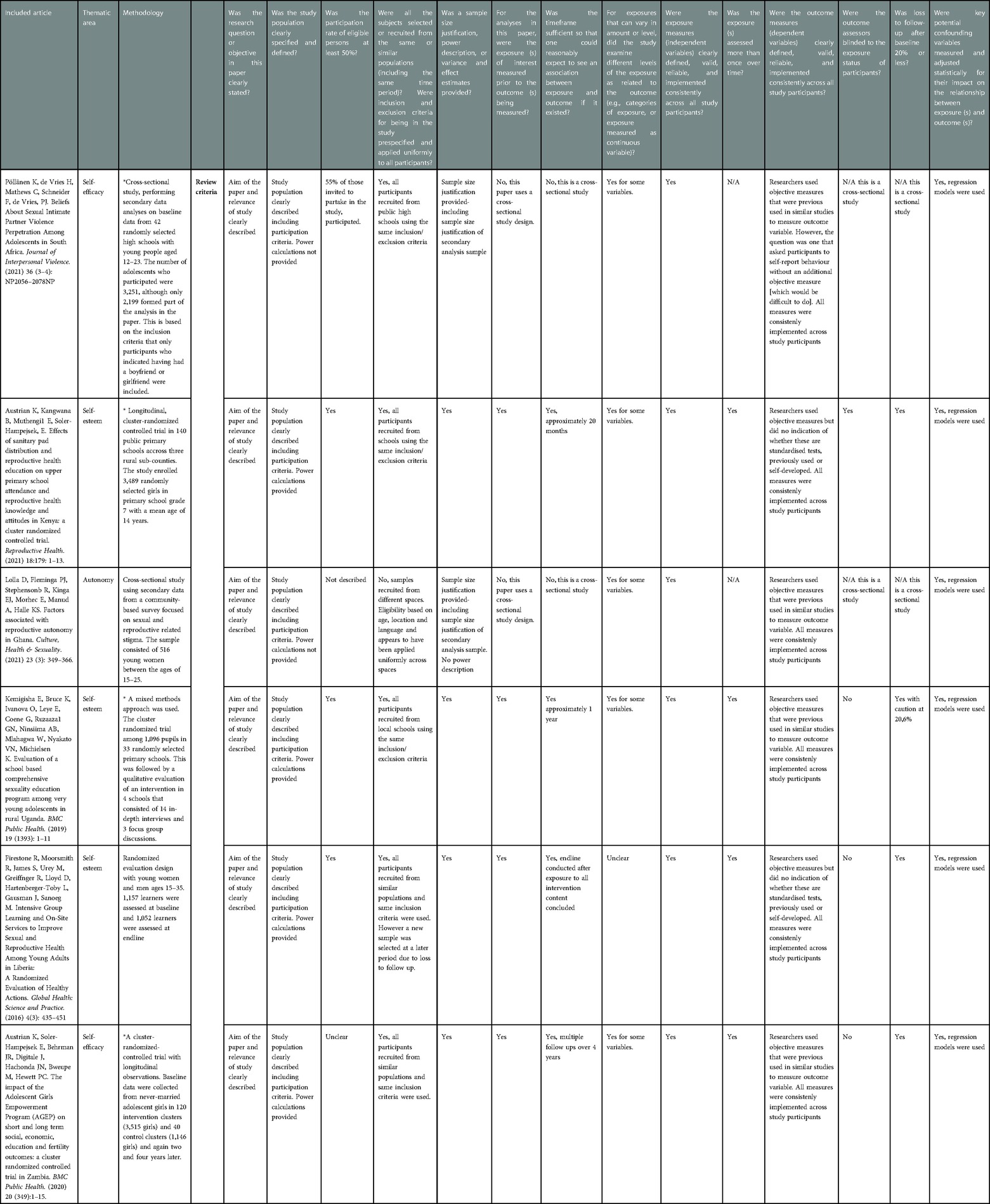

Furthermore, we also conducted quality appraisals of the articles included in this paper using two frameworks. For papers that employed qualitative methods (including the mixed methods study), we used the Long and colleagues' revised critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool (23), while we appraised quantitative papers using the Study Quality Assessment Tools proposed by the National Institute of Health (NIH) (24).

Results

Descriptive profile of papers

Most of the papers were published in 2021 (n = 7), followed by 2020 (n = 1), 2019 (n = 1) and 2016 (n = 1). Although most papers were recently published, no studies focused directly on the COVID-19 pandemic. As shown in Tables 1, 2, the majority of the articles made use of quantitative approaches (n = 5) (29–33), followed by qualitative- (n = 4) (25–27, 34), and one mixed methods study (n = 1) (28). Of the studies using quantitative methods, one (n = 1) used a randomized evaluation design, three (n = 3) used a randomized control trial (including the mixed methods study) and two (n = 2) used a cross-sectional design. In terms of context, the articles focused on Kenya (n = 1), Ghana (n = 1), South Africa (n = 4), Uganda (n = 1), Zambia (n = 2), and Liberia (n = 1).

Table 1. Study population clearly described including participation criteria. Power calculations provided.

Agency, hope and sexual and reproductive health

Of the articles that were relevant, studies focused on self-efficacy and self- esteem (n = 2), and agency and autonomy (n = 3). Authors also evaluated programmes that generally aimed to enhance uptake of SRH services amongst adolescents (n = 5). No studies in our sample examined the association between hope and SRH amongst adolescents as framed by our inclusion criteria.

Self-Efficacy and self-esteem

Self-efficacy and self-esteem were identified as important factors in adolescents SRH practices. Adams & Crowly (26) examined the self-management practices and needs of older adolescents (14–19 years) living with HIV in a community in South Africa. They found that amongst those participants who were sexually active, some felt pressured to have sex without a condom and had lower self-efficacy to negotiate condom use with their partners as they had not disclosed their HIV status to their partners (26). Non-disclosure was also associated with enhanced self- esteem and confidence because the secrecy of their HIV status protected the participants from experiencing stigma or othering in their social environments (26). Further, non-disclosure, or keeping their HIV status confidential, played a part in how treatment taking was managed where participants would make concrete efforts (like going somewhere private or taking medication before socialising) to hide their status (26). It was, however, unclear whether this influenced treatment adherence or whether self-esteem or self-efficacy influenced accessing SRH services. Yet, findings did show that some participants did not consider interactions with their healthcare workers as important and felt demotivated to communicate with them due to “the attitude of certain healthcare workers, a large number of patients at the clinics and long waiting times” (26).

The link between self-efficacy and SRH behaviours was also examined by Pöllänen et al. (29) who investigated South African adolescent boys' and girls' experiences and intentions towards perpetrating sexual violence within their relationships. They found that boys not only had attitudes that were more supportive of committing sexual intimate partner violence than girls, but they also had “a lower self-efficacy to refrain from pressurizing a boyfriend or girlfriend to have sex than girls” (29). In the overall sample, self-efficacy to refrain from pressurizing a partner to have sex was also lower in those who had indicated that they had committed sexual intimate partner violence (29). Across both studies included here, self-efficacy influenced sexual behaviours either through an inability to negotiate condom use in sexual relationships (26) or an inability to resist pressurizing a partner to have sex (29).

Agency and autonomy

The role of agency and autonomy in SRH practices and behaviours was discussed in three papers. Munakampe, Michelo and Zulu (27) explored the various discourses that influence adolescent fertility in Zambia. Their findings showed that female adolescents had limited autonomy, or “control of their fertility” which subsequently led to early marriage and early childbearing cultures within the country (27). And while early marriage and childbearing was associated with agency to access SRH services, adolescent girls' agency was compromised by diminished financial independence and reduced autonomy to use SRH information and services. Limited adolescent autonomy was also reinforced by elders in the community, such as parents, teachers or healthcare workers, which subsequently increased adolescents' acceptance of restricted autonomy to make SRH related decisions (27).

Restricted autonomy amongst adolescent females has also been reported in Ghana where Lolla, et al. (30) explored SRH decision-making and communication autonomy of young women. Focusing on females aged 15 to 24 years, Lolla et al. (30) found that older women, women who have never been pregnant, and who have increased social support for adolescent SRH were more comfortable to discuss (communication autonomy) SRH related issues (contraception, pregnancy etc.) with their male partners had more autonomy than young adolescents with no support. On the other hand, increased decision- making autonomy (having control over SRH decisions) was observed amongst younger participants and those who have never been pregnant (30). In this regard, the authors concluded that reproductive autonomy is complex where younger women are more comfortable to talk about reproductive decisions with their male partners but did not necessarily have the “the most say in [making] decisions” around their SRH (30).

Similar findings were also reported in South Africa by Gillespie, et al. (25) who explored adolescents' perspectives of falling pregnant and motherhood in informal settlements. Gillespie et al. (25) found that adolescents' agency to prevent unintended pregnancies was compromised by limited adolescent-friendly SRH services and a lack of communication on SRH practices including issues of safe sex and contraception. Some adolescents reported that they were not comfortable to access SRH services in their community due to fears of being judged and limited privacy at the clinics.

Adolescents thus had limited access to contraceptives and condoms and limited information on safe sex practices. Supporting Munakampe et al. (27) and Lolla et al. (30), the authors concluded that adolescents' agency is multifaceted and that constructions of SRH agency need to consider the various contextual factors that “limit their potential space for action and decision-making” while recognising the attempts that adolescents continue to make to manage their decisions.

Services and programmes

Majority of the included studies evaluated SRH programmes (including services and education programs) for adolescents across different African contexts. In South Africa, the Tutu Teen Truck (TTT) mobile health clinic was developed to improve adolescents access to SRH services (34). Services provided through the TTT included HIV testing, STI testing and treatment, and a range of contraceptives (oral, injectable, and implant). Majority of the adolescent girls who participated in the study used contraceptives, started on PrEP and tested for STIs (34). The findings revealed that TTT made SRH services accessible to adolescents as it eliminated logistical and travel barriers and operated through short visits rather than lengthy appointments (34). In addition, AGYW indicated that positive provider-client interactions they fostered with the TTT strengthen self-efficacy (34). In Kenya, adolescents in primary schools were selected to form part of the NIA project intervention (31). One part of the intervention included adolescent girls receiving one packet of ten disposable sanitary pads monthly and two pairs of underwear, while the other part included a 25-session curriculum delivered by trained facilitators as part of extra-curricular activities in schools (31). The authors reported that although the intervention improved girls' attitudes and self-efficacy, increasing their pride and comfort, it did not improve adolescent girls' attendance in school during their menstruation period.

The remaining three papers reported on the value of education programs to enhance youth SRH knowledge and facilitate positive SRH behaviours. This included the evaluation of the HealthyActions curriculum in Liberia where out of school youth were provided with SRH information and access to products and services (32). An increase in the use of contraceptives and HIV testing centres (HTC) were found among the study sample at the end of the study. Positive SRH outcomes were also reported in Southwestern Uganda where researchers evaluated an intervention designed to enhance SRH knowledge and practices with primary school adolescents (28). Findings showed improved SRH knowledge and increased understandings of SRH related risks (28). Enhanced SRH knowledge was also identified as an outcome of the Adolescent Girls Empowerment Program (AGEP) which was implemented in ten sites across four provinces in Zambia (33). AGEP included three intervention components: firstly, weekly group meetings; secondly, provision of a health voucher to be used at contracted public and private facilities; and thirdly, provision of an adolescent-friendly savings account (33). Findings showed that there was a sustained change in SRH knowledge and self-efficacy, and savings, but the shorter-term changes did not result in longer-term impacts on education or fertility for vulnerable girls in the Zambian context (33). It is evident to state that the findings of the SRH programmes within the included articles revealed that there was improvement with adolescent's self-efficacy, however, it did not focus on agency or hope in relation to adolescents SRH in the African context.

Quality appraisal

The final step in our review was to conduct a risk of bias assessment of the studies using two separate frameworks for papers employing qualitative methods and those using quantitative approaches, as outline previously. Summaries of these assessments are presented in Tables 1, 2. Using Long et al.' s framework (23), Table 1 shows that a primary area for concern amongst the qualitative studies was limited descriptions or justifications on the applicability of qualitative methods to meet the study goals. This limitation was observed in 3 of the 5 studies which may pose a risk of bias and draw caution to how the findings of these studies are interpreted. Other risks included inadequate justifications of the appropriateness of qualitative data collection approaches, where authors generally identified approaches (i.e., individual interviews or focus group discussions) without justification. Only one paper referred to the author's positionality within the research process but did not unpack how this potentially influenced the study outcomes. While all the qualitative papers used representative extracts to present the qualitative data, two papers did not identify a credible analytic technique and majority employed a group coding approach. This collective coding approach may enhance inter-rated credibility of the findings, but this was not unpacked in the studies. Further, an accepted limitation of qualitative studies is restrictions of generalizability of findings which most studies recognized. However, to address these issues, studies adequately related their findings to the broader literature, drawing, also, implications for research policy or practice.

The quantitative studies included in this review generally used structured assessment techniques. As indicated in Table 2, studies that employed evaluation designs provided power estimations on how the sample were identified which enhances the generalizability of the study findings to the broader population. Majority of the studies recruited participants from similar contexts (generally through schools) and all studies uniformly applied their inclusion/exclusion criteria during recruitment. Intervention studies conducted pre-tests and post-test to assess changes in outcomes due to intervention exposure and collected post-test data between 1 year and 4 years after conclusion of intervention. These studies also showed good retention rates where loss to follow-up after baseline was 20% or less. Papers generally described the assessment tools used in the studies, but some did not indicate whether these tools were self-developed or derived from established tools. This may present a risk of bias as it is difficult to assess the validity of such measures (24). However, all papers used methodologically sound analytic approaches and generally relied on regressions which are considered reliable approaches to take account for the influence of confounding variables (24).

In all, the quantitative studies offered less risks of bias, given the structured and objective approaches used to gather and analyze the data. The qualitative studies on the other hand, showed less room for such objectivity, which is not unexpected given the subjective nature of qualitative research. However, qualitative papers used established data collection approaches (although not always justified), and usually employed a group coding approach to assess the groundedness (strength) of codes and sub-themes. These approaches enhance the credibility of the findings which were also interpreted in relation to the literature.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to explore the literature on hope and agency in adolescents' SRH in the African context. While research has explored the factors that influence uptake of SRH services in low-and-middle income countries, our findings show that the role of hope and agency in accessing SRH services is less understood. Importantly, no studies in our sample examined the association between hope and adolescent SRH, highlighting a significant gap in the literature. While we also included the keyword “hopefulness” as part of our Boolean search, this too generated no studies that were directly linked to adolescent SRH. Still, enhanced hope has been associated with decreased participation in health-related risky behaviours such as alcohol use (21) while hopelessness and poor mental health have been associated with an increased likelihood of risk behaviours such as perpetration of sexual violence (35) or other violence behaviours (36). Empirical research to study how hope influences adolescent SRH practices, behaviours and access to services in the African context is warranted.

Studies also explored the link between self-efficacy, self-esteem, agency and autonomy, and adolescents SRH, respectively. While the influence of these constructs in adolescents seeking of SRH services was not a primary focus in some studies, self-efficacy was found to influence sexual behaviours either through an inability to negotiate condom use in sexual relationships (26) or an inability to resist pressurizing a partner to have sex (29). The literature also revealed the complexities of adolescent SRH agency and autonomy where female adolescents had limited autonomy and experienced early marriage and childbearing (27) or did not have “the most say” in their own SRH decisions (30). Agency and autonomy were also linked to uptake of SRH services. Limited access to adolescent friendly SRH services restricted girls’ agency to prevent unintended pregnancies (27) or to take up SRH support (25).

Majority of the included articles discussed SRH programmes to improve adolescents access to SRH services. These included a mobile clinic to deliver SRH services (34), distribution of SRH products to sustain school involvement during menstruation (31), education programs (28, 32, 33). In general, these studies reported positive results where uptake of SRH services like PrEP, HIV testing, contraceptive use amongst adolescent girls, was found (32, 34). Education programs was also found to increase SRH knowledge (28, 31, 33). While the distribution of sanitary pads did not improve school attendance during menstruation, the program did enhance adolescent girls' self-efficacy and positive attitudes towards menstruation (31). While positive results were reported in these studies, further research is necessary to assess the feasibility of these interventions in different countries and communities.

Multi-country investment is pertinent to identify contextually relevant and culturally sensitive interventions and programmes to enhance adolescent SRH and prevent, interrupt, and address the various barriers to accessing adolescent friendly SRH services and products. Contextual factors not only play significant roles in shaping the quality, availability, and accessibility of SRH services and programs for AGYW, but also regulates how young people make decisions or enact their agency and constructions of hope (14, 17, 37). For example, studies show that AGYW's ability to exercise autonomy over their bodies is constrained by traditional, cultural, and religious norms that view publicly expressing sexuality and talking about sex as taboo (38–41). This was also reported in the literature that formed part of this mini review (27, 31–33). Consequentially, accessing sexual and reproductive health services are hindered by limited dialogues about sex and sexuality, or judgemental attitudes that AGYW receive from older healthcare workers (42–44). Young women also fear experiencing stigma and shame after clinic visits as some remain doubtful about health care worker confidentiality (45). Furthermore, the literature in this study also draws attention to impact that wider structural constraints, like poverty and living conditions can have on adolescents' agency and SRH. There was general recognition of the limited availability of SRH services in low resource communities where Rousseau and colleagues (34), for example, called for SRH services that use diverse modalities to deliver services such as the mobile health clinic.

Conclusion

This mini review highlights the importance of understanding the role of individual factors like hope, self-efficacy, agency, and autonomy in adolescent SRH, behaviours and access to services. Studies are necessary to also consider how these factors interact to either facilitate or compromise safe SRH practices and access to services amongst adolescents. Recognising the influence of the social environment in examining these interactions is key, given the important roles that culture, religion and traditional norms play in shaping risk and protective SRH behaviours in African contexts (27, 38–41). Many AGYW are hindered from accessing SRH services due to experiences and fears of being condemned, feeling judged and not being able to engage in open dialogue about sex and sexuality with relatively older health care workers (25, 27, 42, 44–46). In this regard, we support Desmond et al. (21) who argues that we need “to understand how individuals and groups understand their environment, how they interact with and change their environment, and how these understandings and interactions shape behaviour [and access to support or intervention]”.

Moreover, this paper is not without limitations. The review included papers published within particular journals and databases, and within a set timeframe where we may have excluded other relevant. Importantly, access to full text articles were provided through our institutional subscriptions, which may have further restricted access to articles published in journals to which the institution does not subscribe. Our criteria also strictly included empirical studies while other systematic reviews (if available) or unpublished dissertations could offer additional insights into the relationships between hope or agency and adolescent SRH. Papers also focused only on studies that include adolescents within their samples and we therefore acknowledge that further understandings can be gleaned from the broader literature on adult youth SRH.

Author contributions

CG and NI: has contributed to the conception, analysis, interpretation of data, and write up of the work. NI: also facilitated collating of full paper, editing references, and revising of the work. PQ: has contributed to the analysis, write up, and revising of the work. All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Ahonsi B. Scientific knowledge dissemination and reproductive health promotion in Africa. Afr J Reprod Heal. (2017) 21(2):9–10. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2017/v21i2.1

2. Allen F. COVID-19 and sexual and reproductive health of women and girls in Nigeria. Cosmop Civ Soc An Interdiscip J. (2021) 13(2):1–11. doi: 10.5130/ccs.v13.i2.7549

3. Toska E, Hodes R, Cluver L, Atujunad M, Laurenzie C. Thriving in the second decade: bridging childhood and adulthood for South Africa's Adolescents. South Afr Child Gauge. (2019) 2:81–94. http://www.ci.uct.ac.za/

4. Hendry L, Kloep M. Adolescence and adulthood: Transitions and transformations. UK: Palgrave Macmillan (2012).

5. World Health Organisation (WHO). Recommendations on adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights. Global: Inís Communication (2018). Available online at https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/sexual-andreproductive-health (Accessed November 12, 2021).

6. Groenewald C, Isaacs D, Isaacs N. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mini review. Frontiers Reprod Heal. (2022) 4:1–8. doi: 10.3389/frph.2022.794477

7. World Health Organization. Sexual and reproductive health. African Region: World Health organisation, African region (2021). Available online at https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/sexual-and-reproductive-health (Accessed November 12, 2021).

8. Chandra-Mouli V, Neal S, Moller AB. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health for all in sub-saharan Africa: a spotlight on inequalities. Reprod Health. (2021) 8(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01145-4

9. UNICEF. Opportunity in crisis: preventing HIV from early adolescence to early adulthood. Global: UNICEF with UNAIDS, UNESCO, UNFPA, ILO, WHO and the World Bank (2011). Available online at https://data.unicef.org (Accessed November 12, 2021).

10. World Health Organisation. WHO Recommendations on adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights. Global: Inís Communication (2018). Available online at https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275374/9789241514606-eng.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed November 12, 2021).

11. Bandura A. Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J Moral Educ. (2002) 31(2):101–19. doi: 10.1080/0305724022014322

12. Code J. Agency for learning: intention, motivation, self-efficacy and self-regulation. Front Genet. (2020) 5(19):1–15. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00019

13. Banerjee SK, Andersen KL, Warvadekar J, Aich P, Rawat A, Upadhyay B. How prepared are young, rural women in India to address their sexual and reproductive health needs? A cross- sectional assessment of youth in Jharkhand. Reprod Health. (2015) 12(97):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0086-8

14. Vanwesenbeeck I, Cense M, van Reeuwijk M, Westeneng J. Understanding sexual agency. Implications for sexual health programming. Sexes. (2021) 2:378–96. doi: 10.3390/sexes2040030

15. Svanemyr J, Amin A, Robles OJ, Greene ME. Creating an enabling environment for adolescent sexual and reproductive health: a framework and promising approaches. J Adolesc Health. (2015) 56:S7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.011

16. Berhane Y, Worku A, Tewahido D, Fasi W, Gulema H, Tadesse AW, et al. Adolescent Girls’ agency significantly correlates with favorable social norms in ethiopiad implications for improving sexual and reproductive health of young adolescents. J Adolesc Health. (2019) 64:S52–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.12.018

17. Ngwenya N, Seeley J, Barnett T, Groenewald C. Complex trauma and its relation to hope and hopelessness among young people in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. (2021) 16(2):166–77. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2020.1865593

18. Snyder CR. Hope theory: rainbows in the mind. Psychol Inq. (2002) 13(4):249–75. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01

19. Marques SC, Lopez SJ, Pais-Ribeiro RJ. Building hope for the future: a program to foster strengths in middle-school students. J Happiness Stud. (2011) 12(1):139–52. doi: 10.1007/s10902-009-9180-3

20. Canty-MitchelL J. Life change events, hope, and self-care agency in inner-city adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. (2001) 14(1):18. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2001.tb00285.x

21. Desmond C, Seeley J, Groenewald C, Ngwenya N, Rich K, Barnett T. Interpreting social determinants: emergent properties and adolescent risk behaviour. PLoS One. (2019) 14(12):1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226241

22. Duby Z, McClinton Appollis T, Jonas K, Maruping K, Dietrich J, LoVette A, et al. As a young pregnant girl… the challenges you face”: exploring the intersection between mental health and sexual and reproductive health amongst adolescent girls and young women in South Africa. AIDS Behav. (2021) 25(2):344–53. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02974-3

23. Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Res Meth Med Health Sci. (2020) 1(1):31–42. doi: 10.1177/2632084320947559

24. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study quality assessment tools. USA: National Institute of Health (2021) Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (Accessed on 19 January 2023).

25. Gillespie B, Allen H, Pritchard M, Soma-Pillay P, Balen J, Anumba D. Agency under constraint: adolescent accounts of pregnancy and motherhood in informal settlements in South Africa. Glob Public Health. (2021) 9:1–13. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1981974

26. Adams L, Crowley T. Adolescent human immunodeficiency virus self-management: needs of adolescents in the eastern cape. Afr J Prim Heal Care Fam Med. (2021) 13(1):1–9. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v13i1.2756

27. Munakampe MN, Michelo C, Zulu JM. A critical discourse analysis of adolescent fertility in Zambia: a postcolonial perspective. Reprod Health. (2021) 18(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01093-z

28. Kemigisha E, Bruce K, Ivanova O, Leye E, Coene G, Ruzaaza GN, et al. Evaluation of a school based comprehensive sexuality education program among very young adolescents in rural Uganda. BMC Public Heal. (2019) 19(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6343-3

29. Pöllänen K, de Vries H, Mathews C, Schneider F, de Vries PJ. Beliefs about sexual intimate partner violence perpetration among adolescents in South Africa. J Interpers Violence. (2021) 36(3–4):2056–77. doi: 10.1177/0886260518756114

30. Loll D, Fleminga PJ, Stephenson R, Kinga EJ, Morhec E, Manud A, et al. Factors associated with reproductive autonomy in Ghana. Cult Health Sex. (2021) 23(3):349–66. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2019.1710567

31. Austrian K, Kangwana B, Mutheni E, Soler-Hampejsek E. Efects of sanitary pad distribution and reproductive health education on upper primary school attendance and reproductive health knowledge and attitudes in Kenya: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Reprod Health. (2021) 18(179):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01223-7

32. Firestone R, Moorsmith R, James S, Urey M, Greiffnger R, Lloyd D, et al. Intensive group learning and on-site services to improve sexual and reproductive health among young adults in Liberia: a randomized evaluation of HealthyActions. Glob Heal Sci Pract. (2016) 4(3):435–51. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00074

33. Austrian K, Soler-Hampejsek E, Behrman JR, Digitale J, Hachonda JN, Bweupe M, et al. The impact of the adolescent girls empowerment program (AGEP) on short and long term social, economic, education and fertility outcomes: a cluster randomized controlled trial in Zambia. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20(349):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08468-0

34. Rousseau E, Bekker L, Julies RF, Celum C, Morton J, Johnson R, et al. A community-based mobile clinic model delivering PrEP for HIV prevention to adolescent girls and young women in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21(888):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06920-4

35. Martin K, Stermac L. Measuring hope: is hope related to criminal behaviour in offenders? Inter J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. (2010) 54(5):693–705. doi: 10.1177/0306624X09336131

36. Bolland JM. Hopelessness and risk behaviour among adolescents living in high-poverty inner- city neighbourhoods. J Adolesc. (2003) 26(2):145–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-1971(02)00136-7

37. Johnson-Peretz J, Lebu S, Akatukwasa C, Getahun M, Ruel T, Lee J, et al. “I was still very young”: agency, stigma and HIV care strategies at school, baseline results of a qualitative study among youth in rural Kenya and Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. (2022) 25(1):58–65. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25919

38. Erasmus MO, Knight L, Dutton J. Barriers to accessing maternal health care amongst pregnant adolescents in South Africa: a qualitative study. Int J Public Heal. (2020) 65(4):469–76. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01374-7

39. Jabareen R, Zlotnick C. The cultural and methodological factors challenging the success of the community-based participatory research approach when designing a study on adolescents sexuality in traditional society. Qual Health Res. (2021) 31(5):887–97. doi: 10.1177/1049732320985536

40. Mkhwanazi N. An African way of doing things”: reproducing gender and generation. Anthropol South Africa. (2014) 37(1–2):107–18. doi: 10.1080/23323256.2014.969531

41. Wight D, Plummer M, Ross D. The need to promote behaviour change at the cultural level: one factor explaining the limited impact of the MEMA kwa vijana adolescent sexual health intervention in rural Tanzania. A Process Evaluation. BMC Public Heal. (2012) 12(1–12):1–12. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/788

42. Jonas K, Roman N, Reddy P, Krumeich A, van den Borne B, Crutzen R. Nurses’ perceptions of adolescents accessing and utilizing sexual and reproductive healthcare services in Cape Town, South Africa: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. (2019) 97:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.05.008

43. Muller A, Spencer S, Meer T, Daskilewicz K. The no-go zone: a qualitative study of access to sexual and reproductive heatlh services for sexual and gender minority adolescents in Southern Africa. Reprod Health. (2018) 15(12):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0462-2

44. Ndinda C, Ndhlovu T, Khalema NE. Conceptions of contraceptive use in rural KwaZulu- natal, South Africa: lessons for programming. Int J Environ Res Public Heal. (2017) 14(4):353. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14040353

45. Wechsberg WM, Browne FA, Ndirangu J, Bonner CP, Minnis AM, Nyblade L, et al. The PrEPARE Pretoria project: protocol for a cluster- randomized factorial-design trial to prevent HIV with PrEP among adolescent girls and young women in tshwane, South Africa. BMC public Health. (2020) 20(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09458-y

46. Strode A, Essack Z. Facilitating access to adolescent sexual and reproductive health services through legislative reform: lessons from the South African experience. South African Med J. (2017) 107(9):741–4. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i9.12525

Appendix A

a. Rousseau E, Bekker L, Julies RF, Celum C, Morton J, Johnson R, Baeten JM, O’Malley G. A community-based mobile clinic model delivering PrEP for HIV prevention to adolescent girls and young women in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Health Services Research. (2021) 21(888):1–10

b. Pöllänen K, de Vries H, Mathews C, Schneider F, de Vries, PJ. Beliefs About Sexual Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration Among Adolescents in South Africa. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. (2021) 36(3–4): NP2056–2078NP

c. Austrian K, Kangwana B, Muthengi1 E, Soler-Hampejsek, E. Effects of sanitary pad distribution and reproductive health education on upper primary school attendance and reproductive health knowledge and attitudes in Kenya: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Reproductive Health. (2021) 18:179: 1–13.

d. Adams L, Crowley T. Adolescent human immunodeficiency virus self-management: Needs of adolescents in the Eastern Cape. Afr J Prm Health Care Fam Med. (2021)13(1): a2756. https://doi.org/10.4102/ phcfm.v13i1.2756

e. Munakampe MN, Michelo C, Zulu JM. A critical discourse analysis of adolescent fertility in Zambia: a postcolonial perspective. Reproductive Health. (2021). 18(75): 1–12

f. Lolla D, Fleminga PJ, Stephensonb R, Kinga EJ, Morhec E, Manud A, Halle KS. Factors associated with reproductive autonomy in Ghana. Culture, Health & Sexuality. (2021) 23(3): 349–366.

g. Gillespie B, Allen H, Pritchard M, Soma-Pillay P, Balen J, Anumba D. Agency under constraint: Adolescent accounts of pregnancy and motherhood in informal settlements in South Africa. Global Public Health. (2021):1–13. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1981974

h. Kemigisha E, Bruce K, Ivanova O, Leye E, Coene G, Ruzaaza1 GN, Ninsiima AB, Mlahagwa W, Nyakato VN, Michielsen K. Evaluation of a school based comprehensive sexuality education program among very young adolescents in rural Uganda. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19(1393): 1–11

i. Firestone R, Moorsmith R, James S, Urey M, Greiffnger R, Lloyd D, Hartenberger-Toby L, Gausman J, Sanoeg M. Intensive Group Learning and On-Site Services to Improve Sexual and Reproductive Health Among Young Adults in Liberia: A Randomized Evaluation of Healthy Actions. Global Health: Science and Practice. (2016) 4(3): 435–451

j. Austrian K, Soler-Hampejsek E, Behrman JR, Digitale J, Hachonda NJ, Bweupe M, Hewett PC. The impact of the Adolescent Girls Empowerment Program (AGEP) on short and long

k. term social, economic, education and fertility outcomes: a cluster randomized controlled trial in Zambia. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20(349): 1–15.

Keywords: adolescent & youth, agency, autonomy, sexual and reproductive health, self esteem, self-efficacay

Citation: Groenewald C, Isaacs N and Qoza P (2023) Hope, agency, and adolescents' sexual and reproductive health: A mini review. Front. Reprod. Health 5:1007005. doi: 10.3389/frph.2023.1007005

Received: 29 July 2022; Accepted: 30 January 2023;

Published: 17 February 2023.

Edited by:

Thembelihle Zuma, Africa Health Research Institute (AHRI), South AfricaReviewed by:

Leah S. Sharman, The University of Queensland, Australia© 2023 Groenewald, Isaacs and Qoza. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nazeema Isaacs bmlzYWFjc0Boc3JjLmFjLnph

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Adolescent Reproductive Health and Well-being, a section of the journal Frontiers in Reproductive Health

Candice Groenewald

Candice Groenewald Nazeema Isaacs

Nazeema Isaacs Phiwokazi Qoza

Phiwokazi Qoza