- 1Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

- 2The Desmond Tutu HIV Centre, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

- 3Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute (Wits RHI), Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 4Centre for Microbiology Research, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Nairobi, Kenya

- 5Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

- 6Department of Research & Programs, Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

- 7Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

- 8Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

- 9Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

Background: Successful integration of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with existing reproductive health services will require iterative learning and adaptation. The interaction between the problem-solving required to implement new interventions and health worker motivation has been well-described in the public health literature. This study describes structural and motivational challenges faced by health care providers delivering PrEP to adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) alongside other SRH services, and the strategies used to overcome them.

Methods: We conducted in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs) with HCWs from two demonstration projects delivering PrEP to AGYW alongside other SRH services. The Prevention Options for the Women Evaluation Research (POWER) is an open label PrEP study with a focus on learning about PrEP delivery in Kenyan and South African family planning, youth mobile services, and public clinics at six facilities. PrIYA focused on PrEP delivery to AGYW via maternal and child health (MCH) and family planning (FP) clinics in Kenya across 37 facilities. IDIs and FGDs were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using a combination of inductive and deductive methods.

Results: We conducted IDIs with 36 participants and 8 FGDs with 50 participants. HCW described a dynamic process of operationalizing PrEP delivery to better respond to patient needs, including modifying patient flow, pill packaging, and counseling. HCWs believed the biggest challenge to sustained integration and scaling of PrEP for AGYW would be lack of health care worker motivation, primarily due to a misalignment of personal and professional values and expectations. HCWs frequently described concerns of PrEP provision being seen as condoning or promoting unprotected sex among young unmarried, sexually active women. Persuasive techniques used to overcome these reservations included emphasizing the social realities of HIV risk, health care worker professional identities, and vocational commitments to keeping young women healthy.

Conclusion: Sustained scale-up of PrEP will require HCWs to value and prioritize its incorporation into daily practice. As with the provision of other SRH services, HCWs may have moral reservations about providing PrEP to AGYW. Strategies that strengthen alignment of HCW personal values with professional goals will be important for strengthening motivation to overcome delivery challenges.

Introduction

Adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) in sub-Saharan Africa have among the highest HIV incidence rates globally. In southern and eastern Africa, HIV prevalence among young women aged 15–24 is approximately three times as high as males in the same age group (1, 2). Although voluntary medical male circumcision, community-wide HIV testing, and increased antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage for people living with HIV have all contributed to reductions in global HIV incidence, young African women have not significantly benefited from these prevention strategies (3, 4). HIV incidence in African AGYW has remained ~4% in recent HIV vaccine and prevention trials (5, 6). Oral tenofovir-based pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been proven safe and effective in preventing HIV (7), and has tremendous potential to empower young women to protect themselves (8, 9). Longer-acting PrEP formulations with the dapivirine vaginal ring (10, 11) and injectable cabotegravir (12) have also been shown to be safe and efficacious and will provide a choice of PrEP options once they have received regulatory approval. Although oral tenofovir-based PrEP has been included in national guidelines in most sub-Saharan African countries, identifying and refining pathways for its delivery to AGYW is a work in progress.

Integrating PrEP with other sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services has significant potential for reaching young women (13). Over the past 20 years, advocates have argued that integrating HIV testing, care, and treatment into SRH services produces benefits and efficiencies for both facilities and clients (14–17). Some evidence has shown that such integration at antenatal care clinics (ANC), maternal and child health (MCH) clinics, and family planning (FP) clinics results in increased provision, uptake, and efficiency of services while improving client satisfaction and service outcomes (14, 16, 18, 19). However, process evaluations have shown a high degree of heterogeneity in both implementation and results (20–22).

Recently, African countries with high HIV prevalence have begun promoting the integration of PrEP into routinely delivered SRH services. Theoretically, health care workers (HCWs) in FP clinics may be especially well-positioned to counsel on PrEP as they already counsel women on SRH and routinely screen for sexual behavior and HIV risk factors (23, 24). Although there are some early indications that integrated delivery in these clinics is feasible and acceptable to clients, and reach significant numbers of women (23, 25), there is little in the peer- reviewed literature describing potential challenges to sustained, scaled implementation in routine practice settings. This study describes experiences of HCWs delivering PrEP to adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) alongside other SRH services in Kenya and South Africa, the challenges they foresee in scaling integrated PrEP and SRH services, and the strategies they suggest to overcome them.

Materials and Methods

Study Settings

Qualitative data were drawn from two different studies exploring PrEP delivery to AGYW aged 15–25 as an integrated component of SRH services. The Prevention Options for Women Evaluation Research (POWER) study was a prospective cohort implementation science study to evaluate PrEP delivery in six facilities across three locations: two family planning clinics in Kisumu, Kenya; a mobile clinic serving youth in disadvantaged communities and a primary care facility in Cape Town, South Africa; and an adolescent friendly clinic and a primary health care facility in Johannesburg, South Africa. The PrEP Implementation in Young Women and Adolescents (PrIYA) study evaluated the integration of PrEP delivery into existing SRH healthcare services provided in FP and MCH clinics at 37 facilities in Kisumu, Kenya (26). POWER hired study staff to integrate PrEP into other SRH services at four primary study facilities and these staff then provided technical assistance to provide PrEP at two additional facilities. PrIYA hired study nurses to integrate PrEP into existing SRH services at 16 facilities and then provided technical assistance to 21 additional facilities.

The POWER study was reviewed and approved by ethics committees at the University of Cape Town, the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), and the University of Washington. The PrIYA study was reviewed and approved by the Kenyatta National Hospital Ethics and Research Committee and the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection

As part of the POWER study, we conducted in-depth interviews (IDIs) from October 2019 through January 2020 using a semi-structured interview guide. We used purposive sampling to recruit HCWs with different roles and responsibilities in PrEP delivery. Sample size was based on estimates of informational saturation and through extensive conversations with study team members who have extensive experience working with the study facilities. Interviews were conducted in English by two highly experienced, formally trained American qualitative researchers. Interviews lasted between 60 and 90 min and were audio recorded. Interviewers debriefed impressions and experiences of the interview process on telephone calls and via emails throughout the process. POWER staff in Kenya and South Africa hired individuals to transcribed the audio recordings of the interviews verbatim and audio recordings were reviewed and quality checked by the primary interviewers. As part of the PrIYA study, we conducted focus group discussions (FGDs) between October and December 2018. The sample size for FGDs was based on estimates of information saturation and arrived at through extensive discussions with study team members with extensive experience working with Kenyan facilities. FGDs were led by formally trained and highly experienced Kenyan facilitators who had worked with study researchers in other projects. FGDs were conducted in a mix of English, Kiswahili, and/or Dholuo, lasted between 65 and 140 min, and were audio-recorded. FGD facilitators wrote debriefing reports after each interview, highlighting main observations and their own reflections on the group dynamics, including their interactions with the group. Interviewers transcribed audio recordings of the FGD they facilitated verbatim, and then translated them where necessary. Transcripts were quality checked by senior study team members. Both IDIs and FGDs explored perspectives and experiences of delivering PrEP as an integrated component of SRH services provided to AGYW. Participants in both IDIs and FGDs provided written informed consent.

Data Analysis

Interview transcripts were uploaded to Atlas.ti version 8 (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). FGD transcripts were uploaded into Dedoose version 6.1.18 (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, Los Angeles, California, USA). Codebooks for each project were developed through a combination of deductive and inductive methods. Deductive codes were generated from several implementation science frameworks (27–29). Inductive codes were then added through multiple reviews of the transcripts by qualitative analysts. Using a final codebook, interview transcripts were coded by one researcher (SR) while a second researcher (GO) reviewed coded transcripts and noted areas of disagreement. For FGD transcripts, three qualitative researchers (KB-S, AW, and GO'M) divided and independently coded transcripts which were then exchanged and reviewed by a secondary coder who noted areas of disagreement. Disagreements in coding for both IDIs and FGDs were resolved through discussion and consensus. Thematic content analysis (30) was conducted first for each data set (PrIYA FGDs and POWER IDIs) separately, and then common themes across both projects were compiled for this analysis.

Results

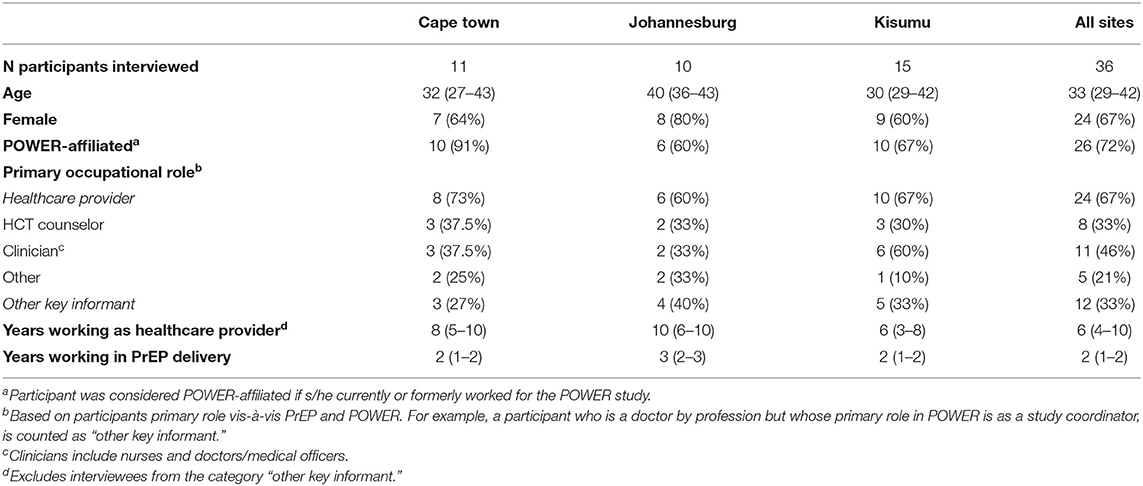

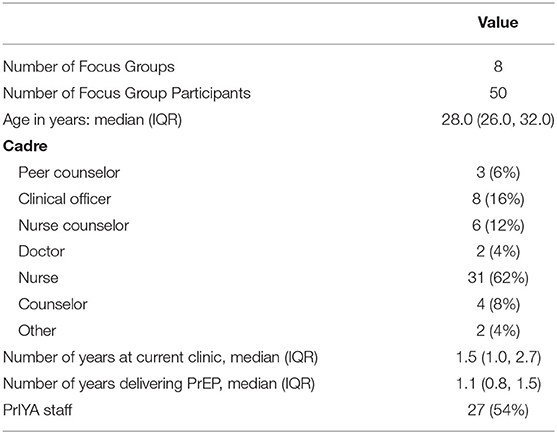

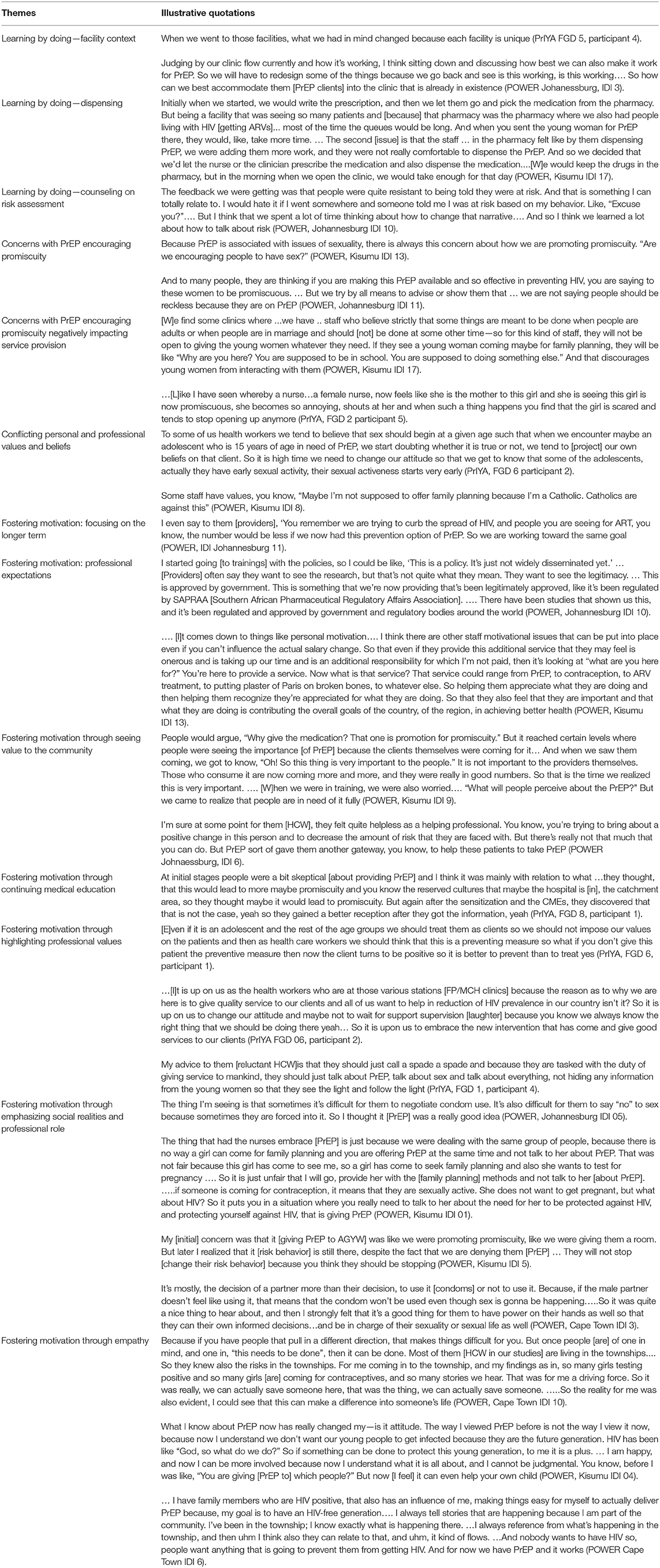

We conducted 36 IDIs with HCWs engaged with the POWER study in six facilities in Kisumu, Cape Town and Johannesburg. We conducted eight FGDs with a total of 50 HCWs affiliated with the PrIYA study across 37 facilities in Kisumu. Most, though not all, of our participants were recruited and trained by the POWER and PrIYA studies. Demographic information about study participants is described in Tables 1, 2. FGD and IDI participants described an active ‘learning by doing’ approach as needed to successfully integrate delivery of PrEP into existing SRH services at their facilities. Participants anticipated HCW motivation as being the biggest challenge to sustained and scaled service integration. Common thematic challenges and strategies related to service integration and PrEP delivery to AGYW are described below. Additional illustrative quotations are included in Table A1.

Learning by Doing: Problem-Solving by Front-Line HCWs Aimed to Strengthen Provision of Patient Centered PrEP Services

HCWs described an ongoing process of active learning and modification of practices to integrate PrEP into existing reproductive health services within the context specific to each clinic.

… [W]e, from different facilities, had to find something that would work in wherever we were working, because at the end of the day what will work for this facility might not work for the other, and we had to come up with ways to make PrEP delivery better for the future generation (PrIYA, FGD 2, Participant 1).

HCWs noted that AGYW were extremely sensitive to perceived judgmental attitudes and stigma associated with sexual activity and PrEP, and hence were very concerned with their privacy. Once initial plans were made and PrEP delivery begun, HCWs reworked delivery processes aimed at improving patient centered care for their AGYW population.

For example, HCWs identified several approaches to minimize the time their young PrEP clients spent in public queues at the clinic, thus lessening their exposure to other clients at the facility whom AGYW feared might judge them. In many clinics HCWs implemented a practice of “fast tracking” PrEP clients by either moving PrEP clients to the head of the queue or by having a single clinician provide multiple aspects of PrEP services in the same consulting room, e.g., HIV testing, counseling, and prescribing.

…[O]nce they come for their clinic day, they need to be fast tracked. … She just goes straight to the clinician, she is given a prescription, then straight to pharmacy. [She] doesn't want to be in the line. When you do like that, you will find them coming back (PrIYA FGD 5, Participant 4).

In many facilities in Kenya, PrEP is dispensed from “ART pharmacies,” that is, pharmacies known to be dedicated to provision of antiretroviral therapy for individuals living with HIV. HCWs reported AGYW did not want to be seen queuing outside these pharmacies due to the stigma associated with being thought to be HIV-infected. In response, some nurses volunteered to pick up PrEP themselves from the ART pharmacy and then dispensed it from their clinic rooms.

HCWs also learned that AGYW often wanted to keep their PrEP use private and were concerned their family members or friends might see the PrEP bottle or hear the tablets rattling. To respond to this concern, some HCWs reported transferring the medication to small plastic bags for distribution so storage of a month's supply of tablets would be more discrete.

Okay, we always repackage the PrEP into a zip lock bag, yeah, that one after we had a meeting of all the employees of the program and we agreed that even if you repackage it, it will not affect the efficacy. So, we always repackage it to a zip lock bag, and they like it that way (PrIYA FGD 1, Participant 1).

Finally, although both South Africa and Kenya have formal PrEP risk assessment tools, HCWs explained that these formal risk assessments could make clients feel judged. In response, many HCW described fine-tuning their risk assessment and counseling techniques to support AGYW in making their decisions about whether they needed/wanted PrEP.

You tell them, “Hey, I'm here for you. So, tell me about your partner.” So, once they start telling you about their life and their partner, you—both of you together—you can start to do assessments like, “So you said he comes late and he's drinking. It's okay. That is his life, and you are used to it. But, you see, there are certain risks.” So, you explore [PrEP] with them and ask, “Is it viable for you or not?” (POWER, Kisumu IDI 3).

HCWs also reported adjusting their counseling advice to acknowledge the fluidity of AGYW sexual relationships, the multiple demands on their time and attention, and affirming their clients' autonomy in deciding whether or how long to use PrEP. Several health care providers used analogies between PrEP and family planning methods to convey key messages about duration of use.

I found that comparing it [PrEP] to contraceptives, it works a lot, like, “You are doing contraceptives, and you can stop anytime you want when you feel that you no longer want to use them…. [Similarly, PrEP] will help you for as long as you need it…” It [the analogy] works well, and you realize that they understand it quickly when you go that route (POWER, Johannesburg IDI 11).

Motivational Challenges Due to PrEP Delivery Being Seen as Extra Work and Potential Solutions

Although HCWs in POWER and PrIYA experienced a learning curve in terms of incorporating PrEP into existing SRH services, they all described such service integration as feasible, as long as there was health care worker motivation. Lack of front-line staff motivation was highlighted by participants as the biggest anticipated challenge to scaling up PrEP. They predicted that since HCWs in public SRH clinics typically experience challengingly high patient volumes, they would consider PrEP provision as “added work.”

If you want to add a service to an existing service, the first words you will hear are, “We're already working so hard. You want to add extra now for the same pay?” It's not going to happen. So that in itself is a barrier (POWER, Cape Town IDI 10).

Despite the inclusion of oral PrEP in national HIV prevention strategic frameworks, many HCWs reported having had minimal training or exposure to PrEP, little awareness of why they were being asked to engage in PrEP service delivery, and uncertainty about PrEP's safety and efficacy.

At first … I was like, “Why do you want to give people ARVs and they are not HIV-positive? …. It is going to lead to maybe drug resistance? …” At that point, I was not that enlightened about PrEP because I had known about HIV and ARVs and stuff, but very little about PrEP (POWER, Kisumu IDI 17).

Study participants emphasized that in order for scaled delivery of PrEP as an integrated component of SRH to succeed, HCWs need to understand not only what PrEP is but why it is being brought in. Our study participants emphasized the important role of sensitization and training of those who are responsible for direct service provision.

It's good to prepare staff. That is the first point for me, because when we arrived at [site name], people were raw in terms of “What are we doing? What is PrEP all about? Why is it necessary?” … If they understand how PrEP works, and you try to troubleshoot whatever fears or concerns they may have, it'll be easy [to scale PrEP up] if these other sites are convinced from the word ‘go’ of why PrEP has to be rolled out (POWER, Johannesburg IDI 04).

Study participants reported that many of the HCWs they encountered were generally unaware that PrEP was part of national healthcare policy. Participants believed that if PrEP policies were disseminated more purposively to HCWs, they would be less inclined to view PrEP provision as extra work.

[One potential challenge to scale-up] is if it's seen as extra work rather than standard of care. …. [P]eople see all the new programs—HIV and AIDS [services], PrEP, even AYFS [adolescent and youth-friendly services]—they see it as extra work. And [they think] that's not their work because they were employed to do this [other thing] … But if you have a memo from the National [Department of] Health, people will do whatever the memo says (POWER, Johannesburg IDI 1).

They also emphasized the importance of the in-charge nurse or lead clinical officer being able to refer to national guidelines to normalize PrEP provision as an integrated component of SRH services.

“[T]he nurse in-charge and the clinical officer, they made us realize that PrEP is in the guidelines. So, it's not that we're doing something new. It is something that's supposed to be in existence already running…. So that made us not feel like, “This is out of place” … (POWER, Kisumu IDI 3).

Finally, several of our participants advised addressing short-term workload concerns by emphasizing the longer-term benefits of reducing HIV incidence in the population, and thus stemming increases in HIV client volume at their health facility.

I think often the problem with something like PrEP … is that the benefits of them are long-term. And it's hard as someone in the thick of it who sees 60 patients a day to see that, by doing this now, you're … reducing your patient load [in the] long term (POWER, IDI Johannesburg 10).

Motivational Challenges Due to Social Stigma and Concerns Around Promiscuity

The most frequently referenced barrier to HCW motivation to deliver PrEP was their uneasiness with adolescent sexuality and their moral concerns regarding sexual activity among unmarried young women. Participants were often told by their colleagues that suggesting a young woman begin PrEP would be the same as encouraging her to have unprotected sex.

I think most people, including some of the health workers, still think that when we talk about PrEP we are encouraging promiscuity or early sex (PrIYA FGD, participant 1).

[Initially,] there was a belief [among some health care workers] that this [PrEP] will cause young women to be more promiscuous … [and HCW were] not wanting to have those conversations with young women … (POWER, Cape Town IDI 2).

IDI and FGD participants frequently described working in locations with “conservative” community and religious norms. Participants emphasized that HCWs are also part of these communities, and frequently share community moral concerns about young women's sexual relationships. These moral reservations in turn negatively impacted motivation and willingness to provide PrEP services.

Actually, when it started, it was a slow move because people would argue, “Why give the medication? That one is promotion for promiscuity” (POWER, Kisumu IDI 9).

They [HCW] are still reluctant about it [providing PrEP]…[T]hey are thinking if you are making this PrEP available and so effective in preventing HIV, you are saying to these kids, to these women, to be promiscuous, that's some of their thinking (POWER, Johannesburg IDI 11).

Overcoming Moral Concerns and Reluctance to Provide PrEP

Study participants reported a variety of strategies to overcome HCW moral reservations about providing PrEP. One approach was to link HIV prevention to a woman's valued role in society, e.g., that of mother.

[I told colleagues] “This PrEP is not for people to be promiscuous. It's for helping people. And even if someone is a kind of sex worker and she's using PrEP, it's still better for her because you know at least she'll stay HIV negative for her children” (POWER, Kisumu IDI 3).

HCWs in our study also tried to overcome colleagues' moral reservations by prioritizing HCWs' professional obligation to keep clients healthy, regardless of their personal opinions about sexually active AGYW.

What I would advise them [colleagues] is when trying to talk to the adolescent, “Try and push that client first. Irrespective of your opinion or the feelings you have, put the interests of the client first … so that you may be able to …help as a healthcare worker” (PrIYA FGD 2, Participant 1).

Study participants also reported trying to persuade their colleagues of the value of providing PrEP through a pragmatic emphasis on the empirical realities of AGYW being sexually active, and their professional responsibility to keep them HIV-free.

Now, you need to realize why did this adolescent come to the clinic for family planning, meaning this girl is going to have unprotected sex, meaning HIV here is not catered for. So, they [HCWs] need to understand that these people are having sex, and they need to take action, yes, despite their values, because at the end of the day they need to protect them. Yes, you will continue shouting, “Abstain! Abstain!” They are not abstaining (PrIYA FGD 4, Participant 5).

In addition, our study participants tried to motivate colleagues to offer PrEP by highlighting the social reality of power differentials between young women and their male partners. In terms of HIV protection, this meant emphasizing PrEP as an empowerment option for women.

PrEP is better when compared with other methods of HIV prevention because, you see, for PrEP, the woman or the lady herself controls it. You see, for a man, he might decide whether to wear condom or not, or when you tell a lady to abstain, the guy might decide whether to abstain or not. But you see, for PrEP, it is within her own control… (PrIYA FGD 2, Participant 5).

[PrEP] gave people more options and more room to make more informed decision and to really feel empowered… [you] don't depend on [your] partners' ‘go-ahead’….So I thought it was a really great option” (POWER, Johannesburg IDI 06).

Some of the health providers interviewed in this study reported urging colleagues to empathize with their young clients' vulnerability. One participant described how encouraging co-workers to imagine members of their own family needing PrEP convinced them that delivering PrEP to AGYW was the right thing to do.

Initially, there was the issue of staff attitude in [facility name], but you know, the good thing is that we got to explain to them that “It can also be your daughter [who needs PrEP] or it can also be you. Maybe today you are here, you know your partner's status, [but] next time, he may be HIV-positive, and you need PrEP.” … So, I think that is what made them feel like, “I am also a human being” (POWER, Kisumu IDI 3).

Several of our participants described how their own initial moral reservations to providing PrEP to AGYW dissipated over time as they gained a greater appreciation of AGYW's HIV risk and began viewing PrEP as an opportunity to intervene.

[Sometimes I'm] like, “Oh my goodness” … But now you think [to yourself], “This is a girl who is at risk. Okay, I have my own values. I have my own beliefs, you know, but now I have to help these young girls, because if I don't, maybe no one will” (POWER, Kisumu IDI 8).

Discussion

HCWs in Kenya and South Africa engaged in delivering PrEP in two studies across 43 facilities described iterative learning to integrate PrEP into SRH services for AGYW. Examples of ‘learning by doing’ included repackaging PrEP pills from bottles to plastic bags, modifying their counseling messages, and streamlining client flow in an effort to make integrated PrEP delivery with SRH services friendlier to adolescents. HCWs believed the biggest challenge to sustained integration and scaling of PrEP for AGYW would be health care worker motivation, primarily due to a tension between personal and professional values and expectations.

The need for iterative learning and practice modifications in order to integrate and scale new health services has been extensively described in the implementation science literature (31–39). Given significant variability in capacity and infrastructure across facilities where SRH services are delivered as well as in the communities they serve, there will not be a single “blue print” for integration of PrEP (40). Successfully integrating new services has been described as mirroring other complex adaptive systems, wherein actors (HCWs and other stakeholders) must continually reinvest energy over time to mobilize resources and engage in an ongoing process of adaptation to refine and realign clinical practices to make them workable, and to meet evolving stakeholder choices, concerns, and expectations (35, 39, 39, 41, 42). This ongoing investment of time and effort relies on frontline health workers being motivated to exercise agency in the adaption and implementation process.

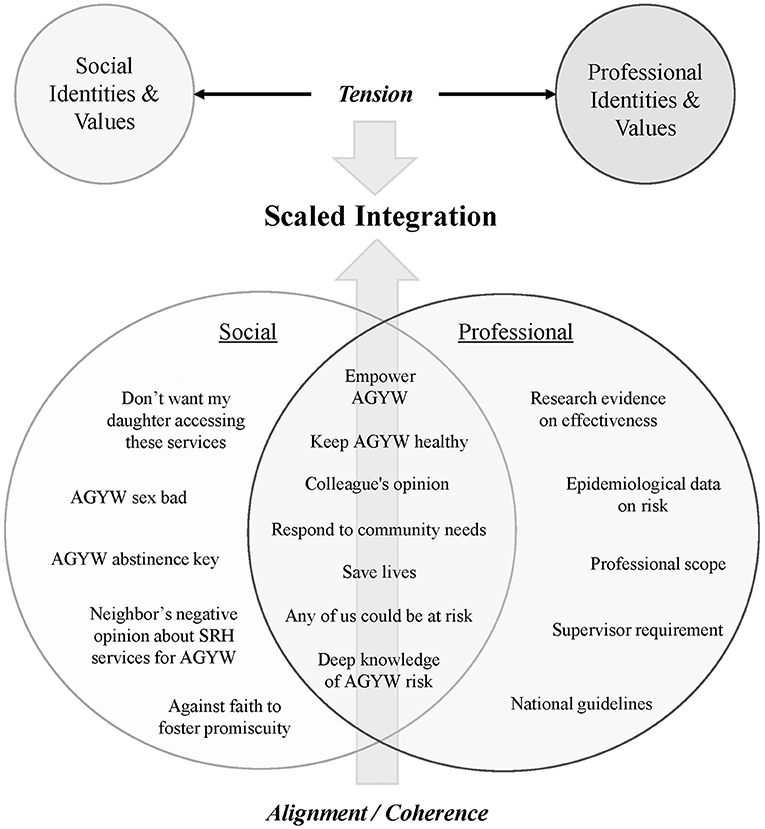

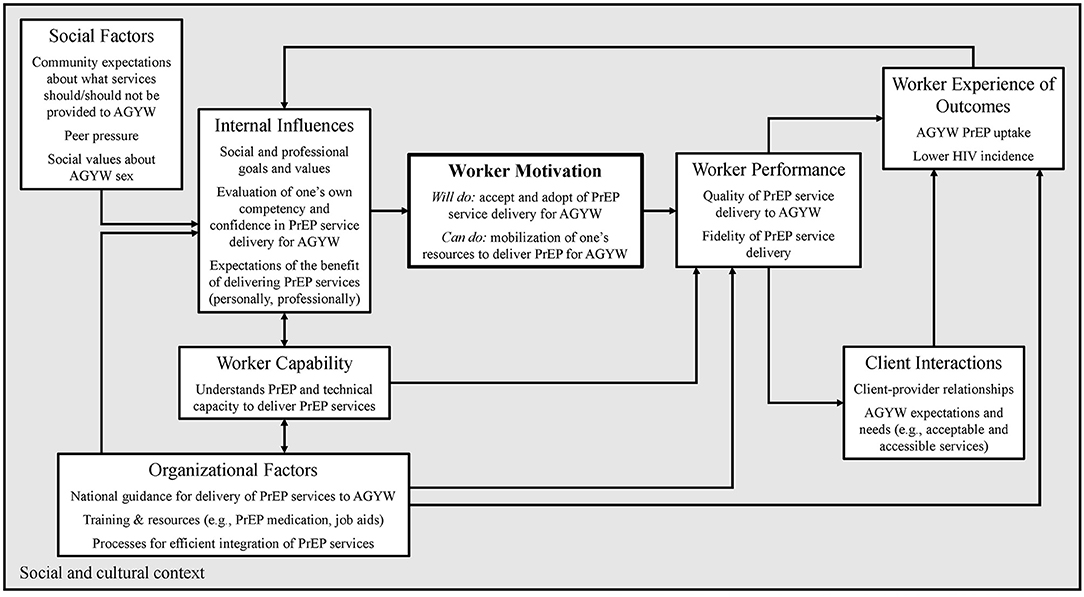

Within the context of these two implementation studies, IDI and FGD participants described their on-going efforts to make PrEP service integration workable and to meet client needs. However, they also predicted health worker motivation would be one of the most likely barriers to delivering PrEP at scale as an integrated component of SRH outside of study contexts. Process evaluations of the interaction of HIV testing, care, and treatment services have similarly identified motivation as a key factor influencing service integration (14, 20, 42). More broadly, health worker motivation has been identified as a prime factor influencing performance of an expected task (39, 41, 43–46). Capacity to provide a new service consists of both “can do” and “will do” components. Skills-based training, national guidelines, and basic materials (e.g., PrEP medication) facilitate the can do of service integration. However, intrinsic motivation is essential to whether providers will do so [(36, 47, 48); Figure 1].

Participants in our study highlighted moral reservations about providing PrEP to AGYW which negatively impacted HCW motivation to invest in the work necessary for service integration. The primary moral concern expressed was not wanting to foster sexual promiscuity. Other studies have similarly described HCW concerns with PrEP provision as condoning or encouraging sexual promiscuity among AGYW, MSM, transgender women, injection drug users, and Black Americans, resulting in lowered health provider willingness to prescribe PrEP to these clients (49–54). More generally, in a systematic review of health care worker motivation, the construct of “moral norms” was found to be a significant determinant of intention, and intention predictive of provider's behavior (55, 56).

HCWs belong to multiple communities in their personal and professional capacities which may have different values and expectations related to PrEP provision. Although national guidelines and formal trainings (professional community) may clearly articulate expectations supporting integration of PrEP with other SRH services for young women, HCWs are also heavily influenced by their social worlds (extended family, neighbors, and faith communities) which may hold very different norms, expectations, and values (38, 39, 43, 56–58). The lack of congruence or alignment between personal and professional expectations and values may add a psychological burden as health providers exert effort to resolve the tension between the two, serving as a demotivating influence on the task-focused work of PrEP and SRH integration (45, 59). While individuals can hold multiple beliefs about a behavior or an intervention, the psychological principle of salience suggests one can attend to a relatively small number of beliefs at any given moment (60, 61). Our study participants described several strategies of persuasion they used to help co-workers resolve this tension, either through encouraging alignment between the personal and professional or be encouraging the salience of professional values as they tasked with integrating PrEP and SRH for AGYW.

First, they urged colleagues to prioritize their professional identities and the associated vocational responsibilities of keeping young women healthy. The construct of “professionalism,” i.e., how closely health care providers identify with the values and expectations associated with their profession, has been documented as an important motivator to implementing evidence-based practices (56, 62). Second, our study participants described entreating their colleagues to recognize AGYW's disproportionate HIV risk and societal norms which often constrain a young woman's ability to keep herself HIV-free, either via abstinence or the use of condoms, and highlighted the potential of PrEP to empower women to protect themselves. Health care worker belief that an intervention is well-placed to meet a client's specific needs has been identified as an important facilitating factor in intervention implementation (27). Finally, our study participants sought to strengthen their colleagues' motivation through appealing to their empathy, urging them to imagine they or their female relatives needed PrEP. The more closely HCWs can align their own perceived risks and needs with those of their client population and their community, the more highly motivated they may be to provide the intervention (41, 63, 64). All of these strategies may contribute to HCWs developing a sense of “coherence” around PrEP and SRH service integration for AGYW. Coherence has been described as a set of beliefs drawing from professional, social, and personal identities, which facilitate actionable meaning-making about an intervention [(45, 56, 62, 65); Figure 2]. The more frontline HCWs perceive a service or practice as meaningful and useful, the more highly motivated they will be and the more likely they are to expend the necessary energy for its implementation (41, 63).

Figure 2. Health care worker motivation and values alignment. Figure adapted from Franco, Bennet, Kanfer, Social Science & Medicine 54 (2002).

Moral concerns around women's sexual activity are not unique to PrEP delivery (66, 67). HCW judgmental and censoring attitudes, especially toward sexual activity of adolescent and unmarried women, have been identified as discouraging the provision and use of contraceptive services by these populations (68–76). Although the WHO and national governments have called attention to the need for adolescent-friendly reproductive health services, progress in public clinics has been slow, though moving in the right direction (77). In spite of natural synergies across the provision of PrEP and other SRH services to AGYW, the success of such planned integration will be limited if moral reservations around family planning are amplified by similar reservations about PrEP among frontline health workers.

There is some evidence that formal training can facilitate changes in HCW attitudes to SRH services to be more client centered, although the outcomes vary greatly depending on training methodologies and content (78, 79). For example, using participatory methods and/or the inclusion of adolescent “standard patients” during training may facilitate shifts in provider attitudes (79–81). Targeted recruitment and use of AGYW as local “PrEP champions” or opinion leaders as trainers, colleagues, or supervisors, may also positively influence shifts in provider attitudes and subsequent practice (82–84). Although widespread positive attitudes about SRH for AGYW, including PrEP, will not in themselves be sufficient for scaled integration and implementation, these will be foundational to a facilitative context (76, 85).

Maximizing the synergistic potential of SRH and PrEP should also consider services integration outside of health facilities. In many countries, policy shifts and product innovations are enabling increased access to SRH services without increasing patient volume at SRH clinics. For example, pharmacies and drug shops are important sources for oral contraceptive pills, emergency contraceptives, and condoms (86). In recent years, a subcutaneous contraception injection product containing medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPASC) has been developed and shown it can be safely used by both community health workers and via self-injection (87). Well-designed digital health applications providing educational information can be highly acceptable to clients for accessing reproductive health information (88). Innovations such as these should also be considered for PrEP as a means toward broadening access for AGYW (89).

An important limitation of our analysis is that it was conducted within the context of two studies, with more resources and training available than in purely programmatic settings. Both PrIYA and POWER hired health care providers as study staff to provide technical assistance and some direct support for integrated PrEP/SRH services. HCW descriptions of workload and motivational challenges could be different outside of a research context. However, all of our study participants had extensive experience with public health clinics in their countries, and not all of the providers interviewed in this project were directly employed by POWER and PrIYA. Motivational issues are likely to be even more important outside of a research context.

Conclusion

While policies, guidelines, and facility-specific protocols are certainly essential tools to guide the integration of PrEP into other SRH services for AGYW, frontline health care workers must be motivated to implement them. HCWs individually and collectively must see the value of and find positive meaning in an intervention such as PrEP for it to become embedded into routine services and practice. Meaning is motivating, and motivation is crucial for the reflexive monitoring and feedback necessary to integrate, modify to evolving context, and hence scale interventions. Decades of family planning research have identified health care worker moral reservations or opposition to providing contraception to adolescents and young women as having a negative impact on the delivery and uptake of contraceptive services. As efforts move forward to integrate PrEP into family planning services for African AGYW, programs should anticipate and proactively work toward overcoming these same concerns.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because request for data sets will require approval of partners in South Africa and Kenya. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Gabrielle O'Malley, Z29tYWxsZXlAdXcuZWR1.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics committees at the University of Cape Town, the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), the Kenyatta National Hospital Ethics and Research Committee and the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

KB-S, SR, GB, and JD organized the database. GO'M, GB, SR, KB-S, and AW coded the data. GO'M wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to conception and design of the study, manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This PrEP Implementation for Young Women and Adolescents (PrIYA) study was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (R01HD094630, R01HD100201, and R01AI125498) and by the United States Department of State as part of the DREAMS Innovation Challenge (Grant # 37188-1088 MOD01), managed by JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc. This study was supported via the University of Washington's Global Center for Integrated Health of Women, Adolescents, and Children (Global WACh). The Prevention Options for Women Evaluation Research (POWER) study was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) (Grant # AID-OAA-A-15-00034) and supported via University of Washington Department of Global Health's International Clinical Research Center. This PrEP for POWER was donated by Gilead Sciences. Data analysis was also supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) via the University of Washington's Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) Behavioral Sciences and Implementation Science Cores (Grant #AI027757).

Disclaimer

The opinions, findings, and conclusions stated herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State, JSI, USAID, NIH, or Gilead Sciences.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the entire PrIYA and POWER study teams and clients for their time and contributions. Additional PrIYA and POWER team study team members: Jaclyn Escudero, Harrison Lagat, Nancy Mwongeli, Winnie Owade, Merceline Awuor, Felix Abuna, Kenneth Mugwanya, Felix Mogaka, Josephine Odyoyo, Nomhle Khoza, Lara Kidoguchi, Ariane van der Straten, Ariana Katz, and Jessica Haberer. We also thank the Kenyan Ministry of Health, the Kisumu County Department of Health, the South Africa National Department of Health, the Gauteng of Department of Health, City of Cape Town Health Department, as well as the facility heads and in-charge for their collaboration.

References

1. UNAIDS. Global AIDS Update 2018. Miles to Go— Closing Gaps, Breaking Barriers, Righting Injustices. Geneva: UNAID (2018).

2. Celum CL, Delany-Moretlwe S, McConnell M, van Rooyen H, Bekker LG, Kurth A, et al. Rethinking HIV prevention to prepare for oral PrEP implementation for young African women. J Int AIDS Soc. (2015) 18(4 Suppl. 3):20227. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.4.20227

4. Vandormael A, Akullian A, Siedner M, de Oliveira T, Bärnighausen T, and Tanser F. Declines in HIV incidence among men and women in a South African population-based cohort. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:5482. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13473-y

5. Evidence for Contraceptive Options and HIV Outcomes (ECHO) Trial Consortium. HIV incidence among women using intramuscular depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, a copper intrauterine device, or a levonorgestrel implant for contraception: a randomised, multicentre, open-label trial. Lancet. (2019) 394:303–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31288-7

6. Corey L, and Gray G. Late breaking news: update from the HVTN 702 vaccine (Uhambo) trial. In: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunitiest Infections (CROI). Boston, MA (2020).

7. Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, Kennedy CE, Baggaley R, O'Reilly KR, Koechlin FM, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. AIDS. (2016) 30:1973–83. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001145

8. Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. (2012) 367:399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524

9. World Health Organization. WHO Implementation Tool for Pre-explosure Prophylaxis (PrEP) of HIV Infection. Geneva (2017).

10. Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, Schwartz K, Soto-Torres LE, Govender V, et al. Use of a vaginal ring containing dapivirine for HIV-1 prevention in women. N Engl J Med. (2016) 375:2121–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506110

11. Nel A, van Niekerk N, Kapiga S, Bekker LG, Gama C, Gill K, et al. Safety and efficacy of a dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV prevention in women. N Engl J Med. (2016) 375:2133–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602046

12. Delany-Moretlwe S, Hughes JP, Bock P, Gurrion S, Hunidzarira P, Kalonji D, et al. Long acting injectable cabotegravir is safe and effective in preventing HIV infection in cisgender women: interim results from HPTN 084. In: R4P Virtual Conference (2021).

13. Celum CL, Delany-Moretlwe S, Baeten JM, van der Straten A, Hosek S, Bukusi EA, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for adolescent girls and young women in Africa: from efficacy trials to delivery. J Int AIDS Soc. (2019) 22(Suppl. 4):e25298. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25298

14. Warren CE, Mayhew SH, and Hopkins J. The current status of research on the integration of sexual and reproductive health and HIV services. Stud Fam Plann. (2017) 48:91–105. doi: 10.1111/sifp.12024

15. WHO, UNFPA, IPPF, UNAIDS. Sexual and Reproductive Health & HIV/AIDS: A Framework for Priority Linkages. Geneva (2005).

16. Church K, and Mayhew SH. Integration of STI and HIV prevention, care, and treatment into family planning services: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plann. (2009) 40:171–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2009.00201.x

18. Gillespie D, Bradley H, Woldegiorgis M, Kidanu A, and Karklins S. Integrating family planning into Ethiopian voluntary testing and counselling programmes. Bull World Health Organ. (2009) 87:866–70. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.065102

19. Lindegren ML, Kennedy CE, Bain-Brickley D, Azman H, Creanga AA, Butler LM, et al. Integration of HIV/AIDS services with maternal, neonatal and child health, nutrition, and family planning services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2012) 2012:Cd010119. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010119

20. Mayhew SH, Ploubidis GB, Sloggett A, Church K, Obure CD, Birdthistle I, et al. Innovation in evaluating the impact of integrated service-delivery: the integra indexes of HIV and reproductive health integration. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0146694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146694

21. Sweeney S, Obure CD, Terris-Prestholt F, Darsamo V, Michaels-Igbokwe C, Muketo E, et al. The impact of HIV/SRH service integration on workload: analysis from the Integra Initiative in two African settings. Hum Resour Health. (2014) 12:42. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-42

22. Colombini M, James C, Ndwiga C, and Mayhew SH. The risks of partner violence following HIV status disclosure, and health service responses: narratives of women attending reproductive health services in Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc. (2016) 19:20766. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20766

23. Mugwanya KK, Pintye J, Kinuthia J, Abuna F, Lagat H, Begnel ER, et al. Integrating preexposure prophylaxis delivery in routine family planning clinics: a feasibility programmatic evaluation in Kenya. PLoS Med. (2019) 16:e1002885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002885

24. Seidman D, Weber S, Carlson K, and Witt J. Family planning providers' role in offering PrEP to women. Contraception. (2018) 97:467–70. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.01.007

25. Milford C, Scorgie F, Rambally Greener L, Mabude Z, Beksinska M, Harrison A, et al. Developing a model for integrating sexual and reproductive health services with HIV prevention and care in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Reproduct Health. (2018) 15:189. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0633-1

26. Kinuthia J, Pintye J, Abuna F, Mugwanya KK, Lagat H, Onyango D, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake and early continuation among pregnant and post-partum women within maternal and child health clinics in Kenya: results from an implementation programme. Lancet HIV. (2020) 7:e38–48. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30335-2

27. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, and Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. (2009) 4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

28. Milat AJ, King L, Bauman AE, and Redman S. The concept of scalability: increasing the scale and potential adoption of health promotion interventions into policy and practice. Health Promotion Int. (2013) 28:285–98. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dar097

29. Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administr Policy Mental Health. (2011) 38:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

30. Hsieh HF, and Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. (2005) 15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

31. Chambers DA, and Norton WE. The adaptome: advancing the science of intervention adaptation. Am J Prevent Med. (2016) 51(4 Suppl. 2):S124–31. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.05.011

32. Paina L, and Peters DH. Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems. Health Policy Plann. (2012) 27:365–73. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr054

33. Castro FG, Barrera M Jr., and Martinez CR Jr. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevent Sci. (2004) 5:41–5. doi: 10.1023/B:PREV.0000013980.12412.cd

34. Nadalin Penno L, Davies B, Graham ID, Backman C, MacDonald I, Bain J, et al. Identifying relevant concepts and factors for the sustainability of evidence-based practices within acute care contexts: a systematic review and theory analysis of selected sustainability frameworks. Implement Sci. (2019) 14:108. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0952-9

35. Rowe A, and Hogarth A. Use of complex adaptive systems metaphor to achieve professional and organizational change. J Adv Nurs. (2005) 51:396–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03510.x

36. Weiner BJ. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implement Sci. (2009) 4:67. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-67

37. Leon N, Lewin S, and Mathews C. Implementing a provider-initiated testing and counselling (PITC) intervention in Cape town, South Africa: a process evaluation using the normalisation process model. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:97. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-97

38. May C, Mair FS, Finch T, MacFarlane A, Dowrick C, Treweek S, et al. Development of a theory of implementation and integration: Normalization Process Theory. Implement Sci. (2009) 4:29. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-29

39. May C. Agency and implementation: understanding the embedding of healthcare innovations in practice. Soc Sci Med. (2013) 78:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.021

40. Birdthistle IJ, Mayhew SH, Kikuvi J, Zhou W, Church K, Warren CE, et al. Integration of HIV and maternal healthcare in a high HIV-prevalence setting: analysis of client flow data over time in Swaziland. BMJ Open. (2014) 4:e003715. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003715

41. Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, and Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. (2004) 82:581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x

42. Mutemwa R, Mayhew S, Colombini M, Busza J, Kivunaga J, and Ndwiga C. Experiences of health care providers with integrated HIV and reproductive health services in Kenya: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. (2013) 13:18. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-18

43. Franco LM, Bennett S, and Kanfer R. Health sector reform and public sector health worker motivation: a conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med. (2002) 54:1255–66. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00094-6

44. Dalkin SM, Greenhalgh J, Jones D, Cunningham B, and Lhussier M. What's in a mechanism? Development of a key concept in realist evaluation. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:49. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0237-x

45. May C, and Finch T. Implementation, embedding, and integration: an outline of normalization process theory. Sociology. (2009) 43:535–54. doi: 10.1177/0038038509103208

46. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. (1977) 84:191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

47. Herscovitch L, and Meyer JP. Commitment to organizational change: extension of a three-component model. J Appl Psychol. (2002) 87:474–87. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.474

48. Meyers K, Price D, and Golub S. Behavioral and social science research to support accelerated and equitable implementation of long-acting preexposure prophylaxis. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. (2020) 15:66–72. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000596

49. Tang EC, Sobieszczyk ME, Shu E, Gonzales P, Sanchez J, and Lama JR. Provider attitudes toward oral preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among high-risk men who have sex with men in Lima, Peru. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. (2014) 30:416–24. doi: 10.1089/aid.2013.0212

50. Bil JP, Hoornenborg E, Prins M, Hogewoning A, Dias Goncalves Lima F, de Vries HJC, et al. The acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis: beliefs of health-care professionals working in sexually transmitted infections clinics and HIV treatment centers. Front Public Health. (2018) 6:5. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00005

51. Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Underhill K, Hansen NB, and Dovidio JF. The impact of patient race on clinical decisions related to prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): assumptions about sexual risk compensation and implications for access. AIDS Behav. (2014) 18:226–40. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0675-x

52. Adams LM, and Balderson BH. HIV providers' likelihood to prescribe pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention differs by patient type: a short report. AIDS Care. (2016) 28:1154–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1153595

53. Pilgrim N, Jani N, Mathur S, Kahabuka C, Saria V, Makyao N, et al. Provider perspectives on PrEP for adolescent girls and young women in Tanzania: the role of provider biases and quality of care. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0196280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196280

54. Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Underhill K, Krakower DS, Magnus M, Hansen NB, et al. Prevention paradox: Medical students are less inclined to prescribe HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for patients in highest need. J Int AIDS Soc. (2018) 21:e25147. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25147

55. Godin G, Bélanger-Gravel A, Eccles M, and Grimshaw J. Healthcare professionals' intentions and behaviours: a systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implement Sci. (2008) 3:36. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-36

56. Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, and Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Safety Health Care. (2005) 14:26–33. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155

57. Hofstede G. Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage (1980).

58. Venter WDF. Pre-exposure prophylaxis: the delivery challenge. Front Public Health. (2018) 6:188. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00188

59. McDonald RI, Fielding KS, and Louis WR. Energizing and de-motivating effects of norm-conflict. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. (2013) 39:57–72. doi: 10.1177/0146167212464234

60. Miller GA. The magical number seven plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychol Rev. (1956) 63:81–97. doi: 10.1037/h0043158

61. Ajzen I. Theory of planned behavior. Org Behav Hum Dec Proc. (1991) 50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

62. Atkins S, Lewin S, Ringsberg K, and Thorson A. Provider experiences of the implementation of a new tuberculosis treatment programme: a qualitative study using the normalisation process model. BMC Health Serv Res. (2011) 11:275. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-275

63. Dissemination and Implementation Models in Health Research Practice. Available online at: https://dissemination-implementation.org/constructDetails.aspx?id=10 (accessed January 15, 2021).

64. Ratka A. Empathy and the development of affective skills. Am J Pharmac Educ. (2018) 82:7192. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7192

65. May C. A rational model for assessing and evaluating complex interventions in health care. BMC Health Serv Res. (2006) 6:86. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-86

66. Myers JE, and Sepkowitz KA. A pill for HIV prevention: deja vu all over again? Clin Infect Dis. (2013) 56:1604–12. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit085

67. Delany-Moretlwe S, Mullick S, Eakle R, and Rees H. Planning for HIV preexposure prophylaxis introduction: lessons learned from contraception. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. (2016) 11:87–93. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000221

68. Bankole A, and Malarcher S. Removing barriers to adolescents' access to contraceptive information and services. Stud Fam Plann. (2010) 41:117–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00232.x

69. Chandra-Mouli V, McCarraher DR, Phillips SJ, Williamson NE, and Hainsworth G. Contraception for adolescents in low and middle income countries: needs, barriers, and access. Reproduct Health. (2014) 11:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-1

70. Preventing Early Pregnancy and Poor Reproductive Outcomes Among Adolescents in Developing Countries: What the Evidence Says. Geneva: World Health Organization (2012).

71. Tilahun M, Mengistie B, Egata G, and Reda AA. Health workers' attitudes toward sexual and reproductive health services for unmarried adolescents in Ethiopia. Reprod Health. (2012) 9:19. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-19

72. Yakubu I, and Salisu WJ. Determinants of adolescent pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health. (2018) 15:15. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0460-4

73. Solo J, and Festin M. Provider bias in family planning services: a review of its meaning and manifestations. Global Health Sci Pract. (2019) 7:371–85. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00130

74. Jonas K, Crutzen R, van den Borne B, and Reddy P. Healthcare workers' behaviors and personal determinants associated with providing adequate sexual and reproductive healthcare services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2017) 17:86. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1268-x

75. Mutea L, Ontiri S, Kadiri F, Michielesen K, and Gichangi P. Access to information and use of adolescent sexual reproductive health services: Qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitators in Kisumu and Kakamega, Kenya. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0241985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241985

76. Webster J, Krishnaratne S, Hoyt J, Demissie SD, Spilotros N, Landegger J, et al. Context-acceptability theories: example of family planning interventions in five African countries. Implement Sci. (2021) 16:12. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01074-z

77. Chandra-Mouli V, Ferguson BJ, Plesons M, Paul M, Chalasani S, Amin A, et al. The Political, research, programmatic, and social responses to adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights in the 25 years since the international conference on population and development. J Adolesc Health. (2019) 65:S16–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.011

78. Warenius LU, Faxelid EA, Chishimba PN, Musandu JO, Ong'any AA, and Nissen EB. Nurse-midwives' attitudes towards adolescent sexual and reproductive health needs in Kenya and Zambia. Reprod Health Matters. (2006) 14:119–28. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)27242-2

79. Denno DM, Plesons M, and Chandra-Mouli V. Effective strategies to improve health worker performance in delivering adolescent-friendly sexual and reproductive health services. Int J Adolesc Med Health. (2020). doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2019-0245. [Epub ahead of print].

80. Seung KJ, Bitalabeho A, Buzaalirwa LE, Diggle E, Downing M, Bhatt Shah M, et al. Standardized patients for HIV/AIDS training in resource-poor settings: the expert patient-trainer. Acad Med. (2008) 83:1204–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31818c72ac

81. Heidke P, Howie V, and Ferdous T. Use of healthcare consumer voices to increase empathy in nursing students. Nurse Educ Pract. (2018) 29:30–4. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.11.007

82. Doumit G, Gattellari M, Grimshaw J, and O'Brien MA. Local opinion leaders: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2007) 24:Cd000125. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000125.pub3

83. Flodgren G, O'Brien MA, Parmelli E, and Grimshaw JM. Local opinion leaders: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2019) 6:Cd000125. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000125.pub5

84. Carpenter CR, and Sherbino J. How does an “opinion leader” influence my practice? CJEM. (2010) 12:431–4. doi: 10.1017/S1481803500012586

85. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, and Pawson R. Realist methods in medical education research: what are they and what can they contribute? Med Educ. (2012) 46:89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04045.x

86. Corroon M, Kebede E, Spektor G, and Speizer I. Key role of drug shops and pharmacies for family planning in Urban Nigeria and Kenya. Global Health Sci Pract. (2016) 4:594–609. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00197

87. Kennedy CE, Yeh PT, Gaffield ML, Brady M, and Narasimhan M. Self-administration of injectable contraception: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Global Health. (2019) 4:e001350. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001350

88. Akinola M, Hebert LE, Hill BJ, Quinn M, Holl JL, Whitaker AK, et al. Development of a mobile app on contraceptive options for young African American and Latina Women. Health Educ Behav. (2019) 46:89–96. doi: 10.1177/1090198118775476

89. Ortblad KF, Mogere P, Roche S, Kamolloh K, Odoyo J, Irungu E, et al. Design of a care pathway for pharmacy-based PrEP delivery in Kenya: results from a collaborative stakeholder consultation. BMC Health Serv Res. (2020) 20:1034. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05898-9

Appendix

Keywords: PrEP, AGYW HIV prevention, sexual and reproductive health services, service integration, health care worker motivation

Citation: O'Malley G, Beima-Sofie KM, Roche SD, Rousseau E, Travill D, Omollo V, Delany-Moretlwe S, Bekker L-G, Bukusi EA, Kinuthia J, Barnabee G, Dettinger JC, Wagner AD, Pintye J, Morton JF, Johnson RE, Baeten JM, John-Stewart G and Celum CL (2021) Health Care Providers as Agents of Change: Integrating PrEP With Other Sexual and Reproductive Health Services for Adolescent Girls and Young Women. Front. Reprod. Health 3:668672. doi: 10.3389/frph.2021.668672

Received: 16 February 2021; Accepted: 22 April 2021;

Published: 28 May 2021.

Edited by:

Agnes N. Kiragga, Makerere University, UgandaReviewed by:

Maria Pyra, Howard Brown Health Center, United StatesDavid Meya, Makerere University, Uganda

Sylivia Nalubega, Soroti University, Uganda

Copyright © 2021 O'Malley, Beima-Sofie, Roche, Rousseau, Travill, Omollo, Delany-Moretlwe, Bekker, Bukusi, Kinuthia, Barnabee, Dettinger, Wagner, Pintye, Morton, Johnson, Baeten, John-Stewart and Celum. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gabrielle O'Malley, Z29tYWxsZXlAdXcuZWR1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share senior authorship

‡Present address: Jared M. Baeten, Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA, United States

Gabrielle O'Malley

Gabrielle O'Malley Kristin M. Beima-Sofie

Kristin M. Beima-Sofie Stephanie D. Roche1

Stephanie D. Roche1 Victor Omollo

Victor Omollo Sinead Delany-Moretlwe

Sinead Delany-Moretlwe Anjuli D. Wagner

Anjuli D. Wagner Jillian Pintye

Jillian Pintye Jared M. Baeten

Jared M. Baeten Grace John-Stewart

Grace John-Stewart Connie L. Celum

Connie L. Celum