95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oral. Health , 16 April 2021

Sec. Oral Health Promotion

Volume 2 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/froh.2021.666713

This article is part of the Research Topic Impact of Uncontrolled Diabetes on Oral Disease Progression and Healing View all 7 articles

Matías Dallaserra1,2

Matías Dallaserra1,2 Alicia Morales3,4*

Alicia Morales3,4* Nayib Hussein5

Nayib Hussein5 Marcela Rivera6

Marcela Rivera6 Franco Cavalla3,4

Franco Cavalla3,4 Mauricio Baeza3,4

Mauricio Baeza3,4 Franz J. Strauss4,7,8

Franz J. Strauss4,7,8 Yazmin Yoma9

Yazmin Yoma9 Claudio Suazo10

Claudio Suazo10 Gisela Jara3

Gisela Jara3 Johanna Contreras4

Johanna Contreras4 Julio Villanueva1,2,11

Julio Villanueva1,2,11 Francisca Valenzuela-Villarroel12

Francisca Valenzuela-Villarroel12 Jorge Gamonal3,4*

Jorge Gamonal3,4*Background: Decompensated diabetes is associated with a higher prevalence and severity of periodontitis and poorer response to periodontal therapy. It is conceivable that periodontal therapy may cause systemic and local complications in this type of patients. The aim of the present study was to identify and describe the best available evidence for the treatment of periodontitis in decompensated diabetics.

Material and methods: An expert committee including participants from different areas gathered to discuss and develop a treatment guideline under the guidance of the Cochrane Associate Center, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Chile. In total, four research questions were prepared. The questions prepared related to decompensated diabetic patients (glycated hemoglobin >8) were, (1) Does the exposure to periodontal treatment increase the risk of infectious or systemic complications? (2) Does the antibiotic treatment or prophylaxis, compared to not giving it, reduce infectious complications? (3) Does the exposure to periodontal treatment, compared to no treatment, reduce the glycated hemoglobin levels (HbA1c)? Last question was related to diabetic patients, (4) Does the exposure to a higher level of HbA1c, compared to stable levels, increase the risk of infectious complications? Based on these questions, a search strategy was developed using MEDLINE and EPISTEMONIKOS. Only systematic reviews were considered.

Results: For question 1, the search yielded 12 records in EPISTEMONIKOS and 23 in MEDLINE. None of these studies addressed the question. For question 2, the search yielded 58 records in EPISTEMONIKOS and 11 in MEDLINE. None of these studies addressed the question. For question 3, the search yielded 16 records in EPISTEMONIKOS and 11 in MEDLINE. Thirteen addressed the question. For question 4, the search yielded 7 records in EPISTEMONIKOS and 9 in MEDLINE. One addressed the question.

Conclusions: In decompensated diabetic patients, there is lack of scientific information about risk of infectious or systemic complications as a result of periodontal treatment and about the impact of antibiotic treatment or prophylaxis on reduction if infectious complications. A defined HbA1c threshold for dental and periodontal treatment in diabetic patients has yet to be determined. Finally, periodontal treatment does have an impact on HbA1c levels.

Chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are a worldwide public health issue, and the leading cause of death with an estimated of 41 million deaths per year [1]. In Chile, it is estimated that 22.8% of the population suffers from two or more NCDs. Diabetes is one of the most frequent NCDs in the population, with a prevalence of 382 million worldwide in 2013 that would increase to 592 million in 2035 [2]. According to the latest data obtained from the National Health Survey [3], Chile has a prevalence of diabetes of about 12%.

Among oral diseases, non-treated caries in permanent teeth is the most prevalent condition worldwide, affecting 2.5 billion people; non-treated caries in primary teeth affect 573 million children, and severe periodontal disease affects 538 million people, including 276 million people with total tooth loss [4]. In Chile, periodontitis affects more than two thirds of the adult population [5, 6]. Periodontitis has been mentioned as the sixth complication of diabetes, with higher degrees of severity in patients with poor glycemic control of their diabetes [7, 8].

Several studies show the bidirectional relationship existing between diabetes and periodontitis. Their connection lies in the common underlying inflammatory processes. When decompensated, diabetes acts as a predisposing factor for periodontitis, affecting the response to periodontal treatment and increasing the risk of tooth loss [9–11]. On the other hand, it has been demonstrated that periodontitis has a deleterious effect on metabolic control in diabetic patients, aggravating cardiovascular complications [9, 10].

In patients with diabetes and periodontitis, improvement in the metabolic indicators of diabetes associated with periodontal treatment still shows contradictory results. Whereas, some studies demonstrate a beneficial effect by lowering the glycemic and glycated hemoglobin levels [12–15], other studies have concluded that there is insufficient evidence for a beneficial effect [16, 17].

In the Chilean Primary Health Care (PHC), a model of comprehensive care has been implemented, in which one of the central aims is the treatment of NCDs [18]. As a result, different health programs exist, in order to cover all the diseases affecting the Chilean population; among them is the Cardiovascular Health Program (CVHP) [19]. It consists of the comprehensive and multidisciplinary care of patients suffering from cardiovascular risk factors who enter in a follow-up and control system, with the aim to decrease the risk of dying. Individuals diagnosed with one or more of the following conditions are admitted in the program: history of atherosclerotic disease, dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and smoking in people older than 55. Reference criteria of determined complications are included in the care of diabetic patients, in which the timely investigation of retinopathy, nephropathy, macroangiopathy and diabetic foot is encouraged [19]. PHC however, lacks a protocol for the care of patients with periodontitis. This results in an increase of referrals to the hospital rising the workload on the specialist and creating a waiting list for periodontal treatment. It should be emphasized that the treatment of periodontitis is included in the list of benefits of the different dental programs existing in the PHC [20–22].

Although the bidirectional relationship of the two diseases has been demonstrated, periodontal treatment is not included within the CVHP for diabetic patients. Moreover, the clinical guidelines for periodontal disease do not define clear directions regarding the management of a decompensated diabetic patient, often resulting in delayed dental care which would ultimately improve the health conditions of the patients [23].

Primary health care must consider the effect of periodontal treatment on the metabolic control of diabetic patients. Therefore, dentistry has the challenge of integrating into a patient-centered care, where clinical care is approached by multiple professionals belonging to different healthcare areas, with fluent communication and focusing on the resolution of the diseases as a multidisciplinary team [24]. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to identify and describe the best available evidence for the treatment of periodontitis in patients with decompensated diabetes and thereby develop a treatment protocol.

The design of this study is a critical review of the scientific literature related to the topic, with the objective to identify and describe the best available evidence on a number of questions already established. EPISTEMONIKOS was used for the search of information, as well as the MEDLINE database. EPISTEMONIKOS combines the best Evidence-Based Health Care, information technologies and a network of experts to provide a unique tool for people making decisions concerning clinical or health-policy questions.

Before the beginning of the study, a group of experts was created, with representatives from the area of periodontal research (AM, MB, FC, FS, JG), public health (CS, YY, GJ), primary health care (CS, YY), family medicine (MR, FVV) and the Cochrane Associate Center of the Faculty of Dentistry, Universidad de Chile (MD, JV). The objective of this group of experts was to gather the main concerns and uncertainties in the dental and medical field, in relation to the periodontal management of patients with diabetes mellitus, with emphasis on the Primary Health Care Programs existing in Chile, in order to prepare the questions that, once resolved, will allow us to propose protocols of care.

In total, four research questions were prepared. The questions prepared related to decompensated diabetic patients (glycated hemoglobin >8) were, [1] does the exposure to periodontal treatment increase the risk of infectious or systemic complications? [2] Does the antibiotic treatment or prophylaxis, compared to not giving it, reduce infectious complications? [3] Does the exposure to periodontal treatment, compared to no treatment, reduce the glycated hemoglobin levels (HbA1c)? Last question was related to diabetic patients, [4] Does the exposure to a higher level of HbA1c, compared to stable levels, increase the risk of infectious complications?

From these questions, search strategies were built for the EPISTEMONIKOS database, as well as for the MEDLINE database, in order to confirm the results. MeSH terms used in the search strategy are described in Table 1. Inclusion criteria for this study are the systematic reviews answering directly the questions involved, since the objective is to identify and describe the best available evidence for each question. All the studies selected were evaluated by independent experts (NH, MD, and JV).

For the questions that had systematic reviews matching the inclusion criteria, evidence matrixes were built in EPISTEMONIKOS to identify the reviews answering the question and the primary studies included. Afterwards, a descriptive report of the available evidence was made for these cases, in relation to the reported effects, risk of bias and methodological aspects of the design of the included studies and their respective primary studies. Regarding the questions without results matching the inclusion criteria, future methodological recommendations will be suggested, according to the type of question.

The results of the search strategy for the 4 questions, according to EPISTEMONIKOS and MEDLINE, are found in Table 2.

When searching studies for the following question: “In decompensated diabetic patients (HbA1c >8%), does the exposure to periodontal treatment increase the risk of infectious or systemic complications?,” a total of 12 systematic reviews was obtained in EPISTEMONIKOS, none of which was relevant for the question asked. While the search strategy for the same question in MEDLINE, gave a total of 23 systematic reviews, none of which was relevant for the question asked, confirming the results of EPISTEMONIKOS.

When searching studies for the following question: “In decompensated diabetic patients (HbA1c >8%), does the antibiotic treatment or prophylaxis, compared to not giving it, reduce infectious complications?,” the search strategy in EPISTEMONIKOS for this question obtained 58 systematic reviews, none of which was relevant for the structures question asked. On the other hand, the search strategy for the same question in MEDLINE obtained 11 systematic reviews, none of which answered the question asked, also confirming the results of EPISTEMONIKOS.

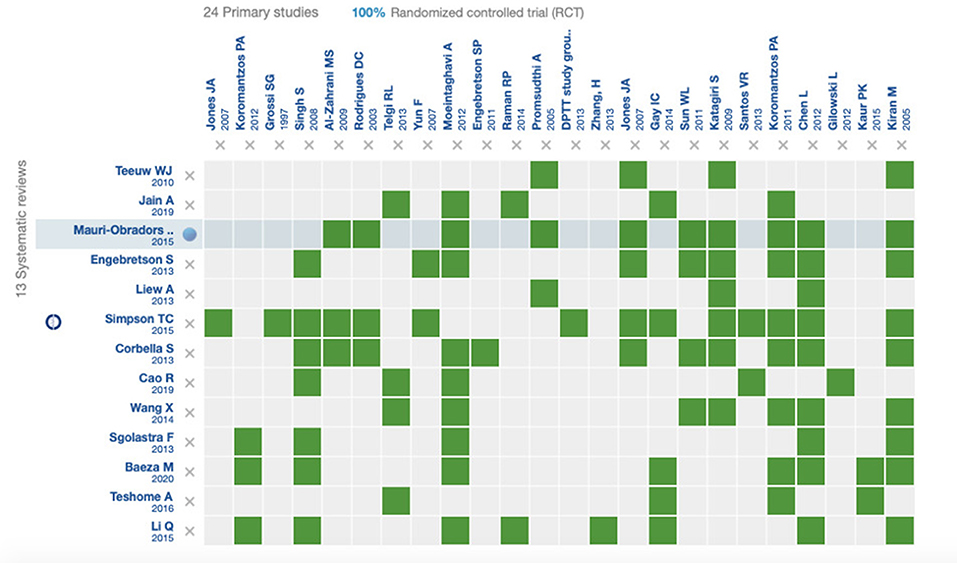

In the next question: “In decompensated diabetic patients (HbA1c >8%), does the exposure to periodontal treatment, compared to no treatment, reduce the HbA1c?,” the search strategy applied in EPISTEMONIKOS and MEDLINE allowed for the construction of an evidence matrix with 13 systematic reviews [12, 17, 25–35] (Figure 1). The systematic reviews contained in the matrix built for this question included 37 primary studies, of which 24 are randomized clinical trials. The effect of periodontal therapy on the levels of HbA1c reported in the different meta-analyses varied with mean differences from 0.27 to 0.65, with statistically significant and clinically relevant results, in favor of the intervention [12, 17, 25–28, 30, 32, 35]. Tables 3, 4 show the description of the systematic reviews included in the question.

Figure 1. Evidence matrix including the systematic reviews answering question 3, and their respective randomized clinical trials.

Finally, in the question: “In diabetic patients, does the exposure to a higher level of HbA1c, compared to stable levels, increase the risk of infectious complications?,” the search strategy applied in EPISTEMONIKOS obtained 7 systematic reviews, and only one of them was relevant for the structured question asked. On the other hand, the search strategy applied in MEDLINE for the same question obtained 9 systematic reviews, and only one of them answered the question, being the same identified with the strategy in EPISTEMONIKOS. The only systematic review answering the question is a qualitative systematic review where no meta-analysis of the studies included was carried out (Tables 3, 5). Besides, this systematic review has methodological limitations, since no exhaustive search in more than one database was carried out and it presented publication bias, since only publications in English were included [36].

Regarding the methodological quality of the different reviews, the vast majority presented publication bias, because their search was limited to studies published in English. Furthermore, the heterogeneity reported by the different meta-analyses was relatively high, reaching 84% [34]. This accounts for possible differences in the population considered in the different primary studies, since the intervention used throughout the studies was always the same.

The internal validity of the randomized clinical trials was not assessed in all the systematic reviews. However, those that did use an appropriate tool to assess risk of bias reported a high risk in most of the articles included (especially for blinding, selective reporting, and incomplete data extraction).

The aim of the present study was to identify and describe the best available evidence for the treatment of periodontitis in patients with decompensated diabetes and thereby develop a treatment protocol.

The search strategy involved the databases MEDLINE and EPISTEMONIKOS in which the latter focuses on decision-making algorithms in the health area [37]. A remarkable feature of EPISTEMONIKOS is the amount of relevant evidence displayed due to the integration of different other databases. The major benefit is the reliable evidence available to answer health questions based on systematic reviews [37]. In the present study four questions were raised. Theoretically, once these questions had been addressed and answered, it would allow us to propose a treatment protocol for patients with decompensated diabetes and periodontitis that could be implemented in primary health care. However, the present study revealed a lack of evidence precluding the construction of a specific protocol.

In decompensated diabetic patients exposed to periodontal treatment, the search strategy failed to identify any appropriate observational study or systematic reviews regarding the risk of infectious or systemic complications. It can therefore, be concluded that there is lack of scientific information to answer the question. More studies are warranted to determine the proposed relationship whether there is a risk of infectious or systemic complication following periodontal therapy.

As for the question of whether antibiotic prophylaxis reduces infectious complications in decompensated diabetic patients, none of the articles directly addressed the question. The search strategy showed an extensive evidence oriented to the use of antibiotics to improve periodontal parameters instead [38]. Therefore, more randomized clinical trials are needed to assess whether the antibiotic treatment or prophylaxis reduces the infectious complications in decompensated diabetic patients.

With respect to the possible HbA1c decrease in diabetic patients following periodontal therapy, the available evidence revealed a significant reduction of HbA1c after periodontal treatment. This is of clinical relevance since a decrease of 1% in HbA1c reduces the probability of major complications of diabetes by 35% [39]. This reduction has been confirmed in a recent study [40]. A previous systematic review on the other hand indicated a reduction of only 0.29% in HbA1c [17]. These differences could be attributed to the great heterogeneity and the high risk of bias of included articles [41]. It is worth noting that it is still unclear how long the HbA1c reduction lasts after periodontal treatment [17, 40].

Other considerations that may have influenced the results were the inclusion of articles only written in English as well as the non-use of all available databases. Furthermore, there were inconsistencies in the results between most reviews. This might be explained by the moderate to high level of heterogeneity (> 40%) found as well as the broad inclusion criteria, the different follow-ups and other confounding variables that were not considered [33]. While Simpson et al. [17] found a HbA1c reduction of about 0.3%, Baeza et al. [35] found a reduction up to 0.6% following periodontal therapy. In a recent clinical study [42], the effects of periodontal therapy in 100 patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic periodontitis were evaluated. The participants were classified as having good (n = 48) or poor (n = 52) glycemic control. The study revealed that periodontal treatment decreased the HbA1c levels by 10% in all patients. However, the improvements were more pronounced in patients with worse glycemic control [42].

With respect to the question whether higher levels of HbA1c increase the rate infectious complications, only one systematic review was found [36]. The authors concluded that there was no relationship between the levels of HbA1c and any postsurgical outcome, including infectious complications. It should be noted, however, that the aforementioned review was merely qualitative and a quantitative data synthesis was not performed. Moreover, the included studies only considered patients in secondary care and limited medical specialties (orthopedics and cardiology) thereby omitting primary health care and other specialties which may have influenced the reported results [36].

In general, most of the reviews included studies with high risk of bias which should be considered when interpreting the reported data. The disagreements found between the systematic reviews, on the other hand, might be attributed to the heterogeneity of the studies, because of the presence of different types of adjuvants, follow-up periods and a high presence of biases. It is important to mention the multifactorial nature of the reduction of glycemia, where, for example, oral care instructions alone have been shown to have effects on glycemia [43]. Jain et al. [34] review stands out [34], where only studies of periodontal treatment as monotherapy were included, reducing the heterogeneity of the results with a decrease of 0.26% in HbA1c, similarly to what Simpson et al. [17] exposed [17].

One strengths of the present study is the use of EPISTEMONIKOS and MEDLINE databases. Nevertheless, and despite the thorough and comprehensive search only limited evidence was found. This clearly indicates that more clinical studies are needed. The present study has some of limitations which should acknowledge. The search strategy involved only 2 databases. Although EPISTEMONIKOS is a broad evidence-based healthcare database, the fact that some studies found in MEDLINE were not included in EPISTEMONIKOS [31, 32] shows the probability to exclude some studies for not researching in more databases. Furthermore, the restricted number of primary studies included limits the generalization of the present findings.

Overall, and due to the lack of clinical studies, clinical recommendations cannot be made. More studies are needed to determine the effect of glycated hemoglobin o the risk of infectious complications. A defined HbA1c threshold for dental and periodontal treatment in diabetic patients has yet to be determined. More studies are required, for the establishment of an evidence-based protocol for patient with decompensated diabetes and periodontitis.

In decompensated diabetic patients, there is lack of scientific information about risk of infectious or systemic complications as a result of periodontal treatment and about the impact of antibiotic treatment or prophylaxis on reduction if infectious complications. A defined HbA1c threshold for dental and periodontal treatment in diabetic patients has yet to be determined. Finally, periodontal treatment does have an impact on HbA1c levels.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

MD, AM, NH, MR, YY, CS, GJ, JC, JV, and JG: conception and design of the study, literature search, analysis and interpretation of data collected, drafting of article and/or critical revision, final approval, and guarantor of manuscript. MD, FC, MB, FS, and FV-V collected data. JV monitored the process. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by FONDEF ID18I10034 and PRI-ODO 19/003.

1. World Health Organization. Non-communicable Diseases. (2018). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed February 19, 2020).

2. Forouhi NG, Wareham NJ. Epidemiology of diabetes. Medicine. (2014) 42:698–702. doi: 10.1016/j.mpmed.2014.09.007

3. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Encuesta Nacional de Salud 2016-2017. Primeros resultados. (2017). Available online at: https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ENS-2016-17_PRIMEROS-RESULTADOS.pdf (accessed January 17, 2021).

4. Bernabe E, Marcenes W, Hernandez CR, Bailey J, Abreu LG, Alipour V, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease 2017 study. J Dent Res. (2020) 99:362–73. doi: 10.1177/0022034520908533

5. Gamonal J, Mendoza C, Espinoza I, Muñoz A, Urzúa I, Aranda W, et al. Clinical attachment loss in chilean adult population: first chilean national dental examination survey. J Periodontol. (2010) 81:1403–10. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100148

6. Strauss FJ, Espinoza I, Stähli A, Baeza M, Cortés R, Morales A, et al. Dental caries is associated with severe periodontitis in Chilean adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. (2019) 19:278. doi: 10.1186/s12903-019-0975-2

7. Loe H. Periodontal disease: the sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. (1993) 16:329–34. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.1.329

8. Khader YS, Dauod AS, El-Qaderi SS, Alkafajei A, Batayha WQ. Periodontal status of diabetics compared with nondiabetics: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes Complicat. (2006) 20:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2005.05.006

9. Khumaedi AI, Purnamasari D, Wijaya IP, Soeroso Y. The relationship of diabetes, periodontitis and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. (2019) 13:1675–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.03.023

10. Genco RJ, Graziani F, Hasturk H. Effects of periodontal disease on glycemic control, complications, and incidence of diabetes mellitus. Periodontol. (2020) 83:59–65. doi: 10.1111/prd.12271

11. Retamal I, Hernández R, Velarde V, Oyarzún A, Martínez C, Julieta González M, et al. Diabetes alters the involvement of myofibroblasts during periodontal wound healing. Oral Dis. (2020) 26:1062–71. doi: 10.1111/odi.13325

12. Engebretson S, Kocher T. Evidence that periodontal treatment improves diabetes outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. (2013) 40:S153–63. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12084

13. Grossi SG, Skrepcinski FB, DeCaro T, Robertson DC, Ho AW, Dunford RG, et al. Treatment of periodontal disease in diabetics reduces glycated hemoglobin. J Periodontol. (1997) 68:713–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.8.713

14. Peña Sisto M, Calzado de Silva M, Suárez Avalo W, Peña Sisto L, González Heredia E. Efectividad del tratamiento periodontal en el control metabólico de pacientes con diabetes mellitus. MEDISAN. (2018) 22:240–7.

15. Quintero AJ, Chaparro A, Quirynen M, Ramirez V, Prieto D, Morales H, et al. Effect of two periodontal treatment modalities in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. (2018) 45:1098–106. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12991

16. Betancourt Garzon K. Protocolo de manejo del paciente diabético en odontología. Duazary. (2005) 2:124–9.

17. Simpson TC, Weldon JC, Worthington HV, Needleman I, Wild SH, Moles DR, et al. Treatment of periodontal disease for glycaemic control in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) 2015:CD004714. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004714.pub3

18. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Estrategia Nacional de Salud para el Cumplimiento de los Objetivos Sanitarios de la Década 2011–2020. (2011). Available online at: http://www.bibliotecaminsal.cl/wp/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Metas-2011-2020.pdf (accessed January 17, 2021).

19. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Orientación Técnica Programa de Salud Cardiovascular. (2017). Available online at: http://www.repositoriodigital.minsal.cl/bitstream/handle/2015/862/OT-PROGRAMA-DE-SALUD-CARDIOVASCULAR_05.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed February 19, 2020).

20. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Orientaciones Técnico Administrativas Para la Ejecución del Programa GES Odontológico 2019. (2019). Available online at: https://www.ssbiobio.cl/public/docs/Orientacion_Tecnica_Programa_Odontologico_Integral_2020.pdf (accessed January 17, 2021).

21. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Orientaciones Técnico Administrativas para la Ejecución del Programa Odontológico Integral 2020. Santiago (2019).

22. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Orientaciones Técnico Administrativas para la Ejecución del Programa Mejoramiento al Acceso 2019. (2019). Available online at: https://diprece.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Orientación-Técnica-Programa-Mejoramiento-del-Acceso-2019.pdf (accessed January 17, 2021).

23. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Orientaciones Técnicas Para la Prevención y Tratamiento de las Enfermedades Gingivales y Periodontales. (2017). Available online at: https://diprece.minsal.cl/wrdprss_minsal/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/2018.01.23_OT-enfermedades-gingivales-y-periodontales.pdf (accessed January 17, 2021).

24. Preshaw P. Diabetes and periodontitis: what's it all about? Pract Diabetes. (2013) 30:9–10. doi: 10.1002/pdi.1732

25. Teeuw WJ, Gerdes VEA, Loos BG. Effect of periodontal treatment on glycemic control of diabetic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. (2010) 33:421–7. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1378

26. Corbella S, Francetti L, Taschieri S, De Siena F, Fabbro M. Effect of periodontal treatment on glycemic control of patients with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. (2013) 4:502–9. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12088

27. Liew A, Punnanithinont N, Lee YC, Yang J. Effect of non-surgical periodontal treatment on HbA1c: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aust Dent J. (2013) 58:350–7. doi: 10.1111/adj.12091

28. Sgolastra F, Severino M, Pietropaoli D, Gatto R, Monaco A. Effectiveness of periodontal treatment to improve metabolic control in patients with chronic periodontitis and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Periodontol. (2013) 84:958–73. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.120377

29. Wang TF, Jen IA, Chou C, Lei P. Effects of periodontal therapy on metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease. Medicine. (2014) 93:e292. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000292

30. Li Q, Hao S, Fang J, Xie J, Kong XH, Yang JX. Effect of non-surgical periodontal treatment on glycemic control of patients with diabetes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Trials. (2015) 16:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0810-2

31. Mauri-Obradors E, Jané-Salas E, Sabater-Recolons M, del M, Vinas M, López-López J. Effect of nonsurgical periodontal treatment on glycosylated hemoglobin in diabetic patients: a systematic review. Odontology. (2015) 103:301–13. doi: 10.1007/s10266-014-0165-2

32. Teshome A, Yitayeh A. The effect of periodontal therapy on glycemic control and fasting plasma glucose level in type 2 diabetic patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. (2016) 17:31. doi: 10.1186/s12903-016-0249-1

33. Cao R, Li Q, Wu Q, Yao M, Chen Y, Zhou H. Effect of non-surgical periodontal therapy on glycemic control of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. (2019) 19:176. doi: 10.1186/s12903-019-0829-y

34. Jain A, Gupta J, Bansal D, Sood S, Gupta S, Jain A. Effect of scaling and root planing as monotherapy on glycemic control in patients of Type 2 diabetes with chronic periodontitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. (2019) 23:303. doi: 10.4103/jisp.jisp_417_18

35. Baeza M, Morales A, Cisterna C, Cavalla F, Jara G, Isamitt Y, et al. Effect of periodontal treatment in patients with periodontitis and diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Appl Oral Sci. (2020) 28:e20190248. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757-2019-0248

36. Rollins KE, Varadhan KK, Dhatariya K, Lobo DN. Systematic review of the impact of HbA1c on outcomes following surgery in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Nutr. (2016) 35:308–16. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.03.007

37. Rada G, Pérez D, Capurro D. Epistemonikos: a free, relational, collaborative, multilingual database of health evidence. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2013) 192:486–90. doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-289-9-486

38. Santos CMML, Lira-Junior R, Fischer RG, Santos APP, Oliveira BH. Systemic antibiotics in periodontal treatment of diabetic patients: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0145262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145262

39. Selvin E, Steffes MW, Zhu H, Matsushita K, Wagenknecht L, Pankow J, et al. Glycated hemoglobin, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in nondiabetic adults. N Engl J Med. (2010) 362:800–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908359

40. Sanz M, Ceriello A, Buysschaert M, Chapple I, Demmer RT, Graziani F, et al. Scientific evidence on the links between periodontal diseases and diabetes: Consensus report and guidelines of the joint workshop on periodontal diseases and diabetes by the International Diabetes Federation and the European Federation of Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. (2018) 45:138–49. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12808

41. Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. (2011) 64:401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015

42. Kaur PK, Narula SC, Rajput R, Sharma RK, Tewari S. Periodontal and glycemic effects of nonsurgical periodontal therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes stratified by baseline HbA1c. J Oral Sci. (2015) 57:201–11. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.57.201

Keywords: periodontitis, diabetes mellitus, periodontal therapy, protocol, glycated (glycosylated) hemoglobin

Citation: Dallaserra M, Morales A, Hussein N, Rivera M, Cavalla F, Baeza M, Strauss FJ, Yoma Y, Suazo C, Jara G, Contreras J, Villanueva J, Valenzuela-Villarroel F and Gamonal J (2021) Periodontal Treatment Protocol for Decompensated Diabetes Patients. Front. Oral. Health 2:666713. doi: 10.3389/froh.2021.666713

Received: 10 February 2021; Accepted: 22 March 2021;

Published: 16 April 2021.

Edited by:

Fahim Vohra, King Saud University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Darshan Devang Divakar, King Saud University, Saudi ArabiaCopyright © 2021 Dallaserra, Morales, Hussein, Rivera, Cavalla, Baeza, Strauss, Yoma, Suazo, Jara, Contreras, Villanueva, Valenzuela-Villarroel and Gamonal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alicia Morales, YW1vcmFsZXNAb2RvbnRvbG9naWEudWNoaWxlLmNs; Jorge Gamonal, amdhbW9uYWxAb2RvbnRvbG9naWEudWNoaWxlLmNs

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.