- Continuum Robotics Laboratory, Department of Mathematical and Computational Sciences, University of Toronto Mississauga, Mississauga, ON, Canada

Tendon actuation is one of the most prominent actuation principles for continuum robots. To date, a wide variety of modelling approaches has been derived to describe the deformations of tendon-driven continuum robots. Motivated by the need for a comprehensive overview of existing methodologies, this work summarizes and outlines state-of-the-art modelling approaches. In particular, the most relevant models are classified based on backbone representations and kinematic as well as static assumptions. Numerical case studies are conducted to compare the performance of representative modelling approaches from the current state-of-the-art, considering varying robot parameters and scenarios. The approaches show different performances in terms of accuracy and computation time. Guidelines for the selection of the most suitable approach for given designs of tendon-driven continuum robots and applications are deduced from these results.

1 Introduction

Continuum robots are slender and soft manipulators that are mainly characterized by their compliance and high dexterity. These properties together with their ability to follow non-linear trajectories and easy miniaturization enables applications in areas such as minimal-invasive surgery (Burgner-Kahrs et al., 2015) or inspection as well as assembly in confined spaces. Due to their inherent compliance, the deformation of continuum robots is highly affected by the presence of external forces. Such forces generally occur at the robot’s tip when interacting with the environment during deployment using different tools fixed at the end-effector. While in theory they offer an infinite number of degrees of freedom, only a subset of those can be actuated in practice. There exist several different actuation principles for continuum robots including both extrinsic and intrinsic methods. An overview of different actuation strategies for continuum robots is reviewed in Burgner-Kahrs et al. (2015).

One commonly employed actuation principle is based on the use of tendons and these robots are called as tendon-driven continuum robots (TDCR, see Figure 1). Several tendons are routed along the robot’s flexible backbone. Actuation of the continuum robot is realized by pulling the tendons which results in bending motions. Tendon actuation is an extrinsic actuation principle, as no actuators are located inside the robot’s structure. The paper by (Hemami, 1985) is one of the first publications concerned with TDCR. This work proposes a flexible lightweight robot arm, which is composed of multiple flexible segments. The bending of each segment can be controlled using three tendons. As a result, the robot can adopt highly non-linear shapes which allows manipulation in confined spaces. A similar design was introduced by Immega and Antonelli (1995), who proposed a robotic manipulator to mimic the characteristic motions of an octopuses’ tentacle, profiting from their inherent compliance and dexterity. In comparison to the robot introduced by Hemami (1985), this manipulator can also extend and retract. The first tendon-driven mechanisms in the context of medical applications are introduced by Webster (1988) and Peirs et al. (2003).

FIGURE 2. The modelling framework of a TDCR that considers the tendon actuation to calculate the resulting configuration space parameters. The configuration space parameters can then be used to obtain the corresponding backbone shape in 3D space.

Over the recent years, many more similar TDCR designs were introduced. In order to design, analyze and control such robotic manipulators, analytic models are required. They allow to calculate the resulting deformed shape of the robot given specific actuation inputs. The actuator space, that describes the actuation of the robot’s tendons, is mapped to a configuration space, which parameterizes the robot’s shape. The configuration space parameters are then mapped to the resulting position and orientation of the shape in task space.

While the configuration space representation theoretically requires an infinite number of parameters due to the continuous nature of their backbones, a reduced set of parameters can be chosen to represent the robot’s backbone. Furthermore, different assumptions of increasing complexity regarding the kinematics and statics of the robot’s backbone and tendons can be included in the mapping between actuation and configuration space. As a result, existing kinematic and static models are often tailored to a specific robot design and make trade-offs between accuracy and computation speed depending on the envisioned application. For instance, continuum robot design requires models which describe the robot behaviour accurately, without specific requirements on the computation time. Robot control is less demanding in terms of accuracy, since model errors can be compensated by sensor feedback, but requires fast computation time.

Although there are various dynamic models to address these challenges (Rucker and Webster, 2011a; Rone and Ben-Tzvi, 2013), we focus the scope of this paper to kineto-static models as these robots are generally operated operated in a quasi-static fashion (Burgner-Kahrs et al., 2015).

Thus, the major challenge when modelling TDCR is to select a viable kinematic and static modelling, choosing suitable kinematic and static assumptions in combination with a corresponding configuration space parameterization with respect to desired accuracy and computation time. We aim to address these challenges throughout this work.

While data-driven models (e.g. Giorelli et al. (2015); Xu et al. (2017)) have been proposed to bypass these challenges, they cannot be applied feasibly for design related tasks. Therefore, we focus the scope of our paper to cover analytical methods.

The contributions of this paper are twofold. First, an exhaustive review of existing kinematic and static analytic models for TDCR is presented. While there already exist a handful of modelling reviews for general continuum robots (Webster and Jones, 2010; Walker, 2013; Chirikjian, 2015; Walker et al., 2016), no review focuses on tendon-driven continuum robots and all their different possible modelling approaches yet. We organize and classify TDCR models based on their representation of the continuum robot’s flexible backbone as well as their kinematic and static assumptions. Second, guidelines for choosing a sufficient and feasible model w.r.t. different scenarios are generated through a numerical case study. In order to do so, the most relevant state-of-the-art kinematic models are implemented in both C++ and MATLAB, partially leveraging and extending their formulations to account for general robot structures and configurations. The code is made openly available to ease the process of developing such models. Based on the implementation, case studies are conducted to compare and benchmark the different model performances for different design parameters and assumptions with respect to their accuracy and computation times. Eventually, by introducing a common terminology and providing open source implementations of representative models, this work provides resources to evaluate any newly proposed modelling approach w.r.t. existing approaches in a straightforward manner.

2 Mechanical Structure of TDCR

As mentioned above, TDCR utilize tendons routed along their backbone that are fixed at predefined locations along the robot’s arc length. They can consist of multiple stacked segments, where each segment end is defined by the termination of one or multiple tendons. When pulling these tendons, a load will be applied to the compliant backbone and the corresponding segment will bend in the direction of the routed tendon.

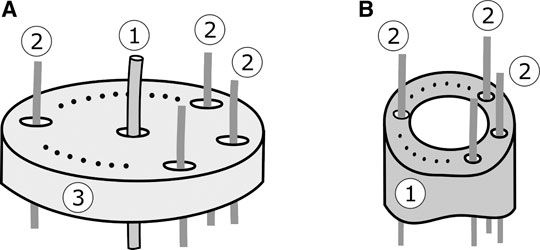

Analyzing the current state-of-the-art of TDCR manipulators, two distinct design structures can be identified as shown in Figure 3. The first structure (Figure 3A) consists of a primary flexible, slender backbone. A finite number of spacer disks is equally distributed along the whole length of the backbone. Guiding holes within the spacer disks are used to route the tendons along the robot backbone. For example, this structure is used in papers by (Rucker and Webster, 2011a) and (Simaan et al., 2004). This design realizes a partially constrained tendon path, in which the tendon path is straight within a subsegment (i.e. between two individual spacer disks), forming a series of line segments along the backbone.

FIGURE 3. Schematics of the two typical TDCR design structures: (A) A primary flexible, slender backbone (1) is employed, while equally distributed spacer disks (3) are used to route tendons along the backbone (2); (B) A larger diameter flexible backbone (1) is used that already features inner lumens to guide the tendons (2) without the need of additional spacer disks.

The second design, shown in Figure 3B, uses a backbone which usually has a larger diameter and already features inner lumens to guide the tendons without the need of separate spacer disks (Camarillo et al., 2008b; Kato et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015). In contrast to the first design, here a fully constrained tendon path is realized. It is assumed that the tendons follow a continuous curve, parallel to the backbone.

For both designs, several components have been considered for realizing the flexible backbone: Either as a single piece flexible tube or rod that has a uniform stiffness (Rucker and Webster, 2011a), multiple concentrically nested flexible tubes that lead to multiple segments each with a different uniform stiffness (Amanov et al., 2019), a flexible tube or rod with a cutting pattern to allow for non uniform stiffness (Camarillo et al., 2008b), or a discrete assembly of multiple stacked compliant joints (Kato et al., 2015). While Amanov et al. (2019) realizes a TDCR structure with segments of variable lengths, we will focus on segments with fixed lengths throughout this work. On top of that, different materials have been investigated for the robot’s backbone, ranging from steel to Nitinol and polymer, leading to vastly different stiffness properties. While special care can be taken when choosing the material of the tendons and the guiding channels to minimize friction and possible stretching of the tendons. However, these effects are often neglected, as their impact on the modelling accuracy is usually considered to be orders of magnitudes lower as the actuation. Therefore, throughout this work, both friction between tendons and the robot’s backbone or spacer disks as well as tendon elongation are not considered.

While in theory, the tendons can be employed using many different routing paths along the backbone, e.g. helical (Starke et al., 2017) or converging (Oliver-Butler et al., 2019) paths, we focus on generalising models for straight tendon routing throughout this work as the most common routing method employed. For each segment, any number of tendons can be employed and routed along the robot’s backbone, while at least two are needed to allow for bending in one degree of freedom (planar bending) and three for bending in two degrees of freedom (spatial bending), respectively.

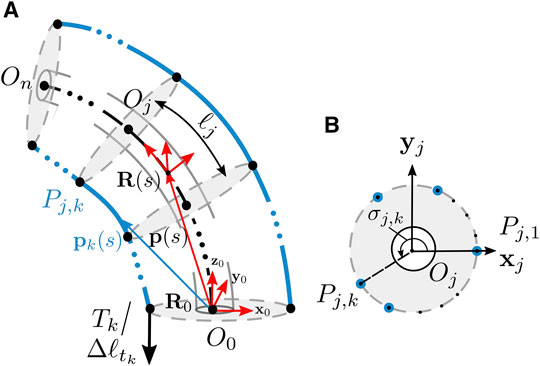

In order to mathematically describe the TDCR structure, we introduce a common nomenclature that is used throughout this work and can be applied to both designs discussed in this section. Figure 4A shows a typical TDCR considered in this review, with equidistant cross-sections. We note, that while the proposed nomenclature is described using one single bending segment, it can be extended to multi-segment robots in a straight-forward manner as described in the later sections. Tendons are routed along the backbone, at a distance

FIGURE 4. (A) Diagrammatic representation of one segment of a TDCR, actuated by tension

Each point on the backbone is parameterized along its arc length

The rotation frame attached at the base of subsegment j at

3 Continuum Backbone Parameterization

Several approaches have been proposed to represent the shape of continuum robots. These methods lead to different expressions of the backbone curvature, and therefore the resulting position and orientation. We classify the existing representations as distributed and lumped backbone parameterizations by adapting the categorization used in Rone and Ben-Tzvi (2014a). In distributed parameterization, the curve is represented as a continuous function of s. It’s state-space has been represented by

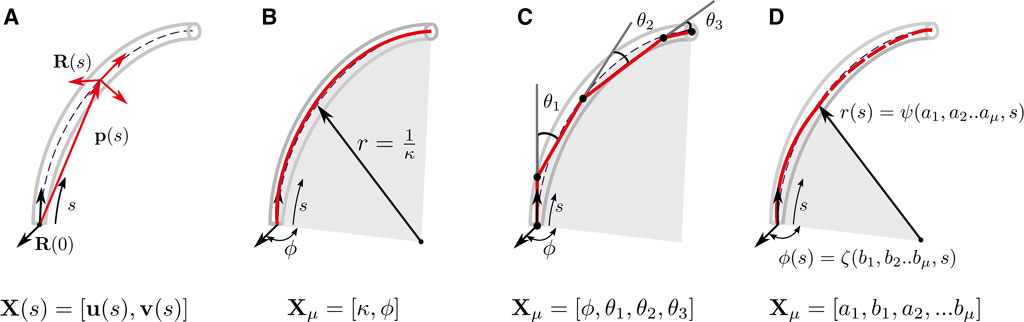

FIGURE 5. Diagrammatic representation of various kinematic frameworks used to describe the backbone. The backbone parameters required are denoted by

3.1 Distributed Backbone Parameterization

As the flexible backbone follows a continuous curve, an infinite number of parameters are theoretically required to describe it in task space. Doing so with state-space vectors that are a continuous function of the distance along the backbone is referred to as distributed parameter modelling. As it makes no assumptions on the backbone shape, it is a geometrically exact representation and can account for any arbitrary variations in curvature by differential equations. Therefore, it is referred to as the variable curvature representation.

The strain variables

When the backbone is assumed to be inextensible and shearless, there is no axial deformation and therefore,

The complete robot shape and orientation in 3D are obtained by integrating Eq. (2) and (3). It is not possible to perform the integration analytically for the entire backbone due to its nonlinear deformations. Therefore, it requires numerical integration (Jones et al., 2009; Dehghani and Moosavian, 2011; Dehghani and Moosavian, 2013a). For only the tip orientation matrix, a closed analytical solution has been derived by Hsiao and Mochiyama (2017). Computing the rotation matrix by integrating Eq. (2) does not ensure that the properties of so(3) are preserved. However, the numerical errors have been shown to be small for the small curvatures experienced by these robots (Rucker and Webster, 2011b). Moreover alternate representations of the orientation using quaternions (Rucker, 2018; Till et al., 2019) can be used to conserve the properties of the special orthogonal group.

3.2 Lumped Backbone Parameterization

In lumped parameter modelling, the backbone is discretized and represented with a finite set of parameters. The required infinite backbone parameters are reduced by making assumptions on the backbone shape using geometry. These assumptions lead to a trade-off between the complexity and accuracy because while they simplify the backbone description, there is an accompanying loss of information as interpolation is required to obtain each point on the backbone. By contrast, the distributed parameterization describes each point on the backbone without interpolation and does not lead to any such loss.

We refer to the finite set of backbone parameters by

3.2.1 Constant Curvature (CC) Assumption

This assumption forms the basis for a common approach to parameterizing the backbone. The backbone is assumed to be a series of mutually tangent sections, which are approximated as arcs with constant curvatures. This approach has also been referred to as the piecewise constant-curvature (PCC) approximation. The constant curvature assumption can be applied to either the entire segment or each subsegment. To distinguish between the two, we refer to them as CC and CCsub respectively. The term ’section’ has been used here to refer to the segment or subsegment, approximated as an arc.

If the effects of torsion are neglected, the section can be assumed to undergo planar deformations. As depicted in Figure 5B, its backbone parameters can be represented by

The above involves a rotation about the y axis by (

Equating ϕ to zero gives the resulting coordinates in the xz plane of the frame attached to the bast of the section. Depending on whether a segment (Hannan and Walker, 2003; Xu et al., 2015; Ouyang et al., 2016; Dalvand et al., 2018; Mishra et al., 2018) or a subsegment (Kutzer et al., 2011; Mahl et al., 2013; Kato et al., 2015; Kato et al., 2016) is being approximated as a circular arc, the backbone parameters are represented by

where

In case the backbone is subject to torsion, an additional parameter ϵ is introduced to account for the twist (Rone and Ben-Tzvi, 2014a; Yuan et al., 2019) in the arc in CCsub. The position vector of the section remains the same as given in equation Eq. (5). However, the rotation matrix includes an additional rotation about the current z axis by (

3.2.2 Pseudo-Rigid Body Representation (PRB)

In the PRB approach, the backbone along a subsegment is modelled as a series of rigid links connected by torsion springs. Roesthuis and Misra (2016) approximate the backbone as a series of rigid links connected by a single torsional spring. However, the optimal stiffness of the springs and length of each link are dependent on the values of force and moment experienced by the robot (Su, 2009). As continuum robots can experience large deformations due to applied load, the 3R model, proposed by (Su, 2009) has been used to model TDCRs as its parameters are load independent. It is applied to the planar case by Huang et al. (2018) and Khoshnam et al. (2015), and further extended to the 3D case by Huang et al. (2019). The subsegment is approximated by four rigid links, as shown in Figure 5D, with the first and last link tangent to the local z axis.

The length of each link

The value of

where

Ashwin and Ghosal (2019) and (2021) propose a backbone representation specific to TDCRs, where the backbone, along with the tendons, is modelled as a series of two adjoined perpendicular four-bar links. In a given subsegment, the backbone forms the crank with length

3.2.3 Modal Approach

In the modal approach, the backbone is expressed in terms of curve parameters, which are linear combinations of modal shape functions (MSFs). The MSFs are continuous functions, dependent on s and are used to describe a given curve parameter

where

Godage et al. (2011a) express the backbone coordinates as polynomial functions of the actuator lengths. Each MSF is derived using the Taylor series expansion of the curve parameters, expressed in terms of the input actuator lengths (Godage et al., 2011b; Godage et al., 2015). Polynomial approximation of curve parameters provides an alternative option for the shape functions. Santina and Rus (2020) approximate the curvature as a polynomial in terms of the parameter s.

4 Kinematic Modelling

Kinematic modelling involves mapping the tendon lengths to the corresponding backbone position and orientation. The tendon lengths (

4.1 Fully Constrained Tendon Path

When the constant curvature assumption is used, the arc parameters (

where

As the segment requires only two degrees of freedom, one of the tendons becomes redundant for three-tendon actuation, experiencing the following constraint

Using the above relations, a closed-form solution for the three-tendon actuation is given by (Hannan and Walker, 2003; Webster and Jones, 2010)

To avoid singularities arising in the position coordinates when

Using the PRB model described in 3.2.2, Ashwin and Ghosal (2021) propose the forward kinematics of a TDCR. A subsegment is approximated as a four-bar mechanism. It is proven that the configuration of the backbone in static equilibrium is one where the change in coupler angle from the straight configuration is minimized. In 3D, a series of two four-bar mechanisms, perpendicular to each other are considered. Numerical optimization is used to calculate the configuration that results in the minimum change in the coupler angle from the straight configuration.

4.2 Partially Constrained Tendon Path

For the constant curvature assumption, the same approach as detailed for the fully constrained tendon path can be applied. The relation between n subsegments having partially constrained tendon length

The tendon lengths calculated for a partially constrained design equals the length calculated for a fully constrained design when

An alternate representation is proposed by Allen et al. (2020) to avoid singularities in representing the straight configuration (when

4.3 Extending to Multiple Segments

When there are g segments stacked on top of one other, the behaviour of each segment can be considered independently. Then, the transformation matrices of each segment can be multiplied consecutively to obtain the forward kinematics of the robot. However, there is coupling between the segments due to multiple sets of tendons passing through them. Jones and Walker (2006a) propose a tangle/untangle algorithm that takes into account the effect of this coupling between segments to predict the behaviour of the multisegment robot.

5 Static Modelling

Static modelling involves the mapping of tendon tension and external forces to the robot backbone shape. We consider the tensions

5.1 Forces due to Constraints on the Tendon Path

Tendons apply two major types of forces on the backbone - termination forces at their point of attachment and distributed forces along the backbone. The magnitude and direction of these forces is determined the assumed tendon path.

5.1.1 Forces due to Fully Constrained Tendon Path

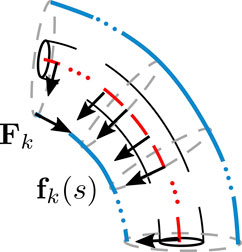

The kth tendon applies a force

where

FIGURE 6. Representation of uniformly distributed force

The net force and moment acting on the backbone at the end of a segment is calculated by the vector summation of all tendon termination forces and moments. The distributed force,

If the tendon is assumed to be an inextensible string with no friction acting on it, the tension acting along it remains constant. While describing friction models is out of the scope of this paper, there are models that account for friction (Do et al., 2015; Back et al., 2016) for fully constrained tendon paths. Being perfectly flexible, it can only support tensions that are tangent to the tendon path. The internal force in the tendon is then given by,

Substituting the above in equation Eq. (26), gives

These distributed forces also exert a distributed moment,

Similar to the tendon termination forces, the net distributed force acting on the backbone is given by summing the individual forces.

A simplified approach would be to assume that the tendons apply only a pure moment at the point of termination (Gravagne et al., 2003a; Jones et al., 2009) or a force at the point of tendon termination resulting in an additional force and moment acting on the backbone (Dehghani and Moosavian, 2013a; Dalvand et al., 2018). While pure moment models result in good accuracy for in-plane bending, they do not predict nonplanar deformations resulting from external tip forces well (Rucker and Webster, 2011a). In order to model out-of-plane bending, an additional uniformly distributed tendon force,

5.1.2 Forces due to Partially Constrained Tendon Path

At every disk, the tendon k applies a force

where

FIGURE 7. Diagrammatic representation of the forces

The net force and moment acting on the backbone at the jth (

When the friction between the tendons and disks can be neglected, the tendons passing through a disk can not transmit forces perpendicular to the disk. As a consequence, the component of the tendon force along this direction must be equal to zero.

However, in cases where friction cannot be ignored, an additional frictional force acting perpendicular to the disk needs to be included in the force balance equations. There are various tension propagation models (Jung et al., 2011; Kato et al., 2016; Gao et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2019) that can be adapted for use in such situations.

5.1.3 Extending to Multiple Segments

Actuating g segments results in more than one set of tendons passing through the first

5.2 Constitutive and Equilibrium Equations

As the robot backbone undergoes elastic deformations while experiencing small strains (Gravagne et al., 2003b), Hooke’s law is used to develop the corresponding static models. The backbone is modelled as a beam, undergoing linear elastic deformation where the stress experienced by the backbone is linearly proportional to the strain. In addition, we assume that the backbone and tendons are inextensible. In general, the undeformed reference position of the backbone can be represented using the variable curvature representation as

where

where A is the area of cross section as a function of s, G is the shear modulus,

5.2.1 Variable Curvature

The Cosserat theory of elastic rods (CRT) uses the variable curvature representation to assign six degrees of freedom to each point on the backbone (three translational and three rotational) (Altenbach et al., 2013). It can account for shear deformations as well. For a rod in static equilibrium, the internal force and moment vectors,

where

The tendon termination and external forces and moments are included in the boundary conditions. The resulting changes in internal force and moment due to these forces at the end of a segment is given by

where

5.2.2 Constant Curvature

For backbones assumed to be bending with constant curvature, Euler Bernoulli beam theory can be applied. It assumes that the effects of shear and twist are negligible (Bauchau and Craig, 2009). The bending moment along the beam is assumed to be proportional to its curvature. Hooke’s law reduces to a one-dimensional equation and is given by

It has been used to model both segments (Camarillo et al., 2008b; Ryu et al., 2019) and subsegments (Yuan and Li, 2018; Yuan et al., 2019; Rone and Ben-Tzvi, 2014a; Dehghani and Moosavian, 2013a; Dehghani and Moosavian, 2013b; Dehghani and Moosavian, 2014a; Dehghani and Moosavian, 2014b). To account for bending and twist with CCsub the components of curvature of a subsegment j along the three axis are used to represent the 3D circular arc. Expressed with respect to

where

where

where

5.2.3 Pseudo Rigid Body (PRB) Models

The 3 R PRB model proposed by Su (2009) has been used to propose a model that can account for twists in each subsegment. As detailed in Section 3, the backbone is approximated by 4 rigid links connected by 3 torsion springs. The bending components of the net moment

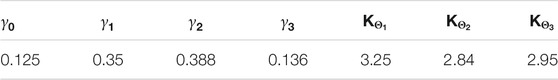

The values of the characteristic parameters, γ and

The static model is then obtained by writing the equilibrium conditions of the TDCR at each joint. The point at the center of joint q belonging to subsegment j is called

In order to compute the bending plane angle

To the best of our knowledge, this model has not been extended to TDCR with arbitrary number of segments or sub-segments and subject to twist, under the influence of an external force. In this case, the component

Second, we add an additional equilibrium equation to account for the twist, by calculating the net moment in with respect to the frame

where

6 Comparison of TDCR Models and Guidelines

6.1 Synthesis

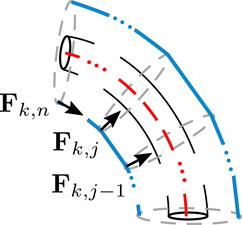

As reflected in the previous sections, modelling the kinematics or the statics of TDCR can be decomposed into two tasks: choosing between lumped or distributed parameters to represent the backbone and assuming the tendon path is either fully or partially constrained. We classify the modelling approaches accordingly. The classification is summarized in Figure 8. The kinematic models (left column) are used for modelling TDCRs, where the segment is assumed to obey the CC assumption. The robot shape can thus be described with a minimal number of parameters. The tendon tensions and external forces (right column) lead to a variation in the backbone curvature, and is represented with a higher number of parameters.

FIGURE 8. Proposed classification of different modelling approaches based on the backbone parameters required to define the backbone and assumed tendon path. The left column shows pure kinematic modelling, which maps the tendon lengths to the backbone pose while the statics modelling in the right column considers the backbone properties such as Young’s modulus (E), moment of inertia (I), shear modulus (G) as well as the effect of resulting tendon forces (

Choosing a suitable model for a desired TDCR design and application is not trivial. Distributed parameters can accurately describe the variation of curvature in the presence of external forces, but the resulting model is computationally demanding due to the required theoretically infinite number of parameters. The accuracy of lumped parameters depends on the deformation of the robot under external forces, which in turn depends on the magnitude of these forces, the robot length, and stiffness. In cases that require a large number of parameters to obtain sufficient accuracy, lumped parameterization can become more computationally expensive than distributed parameterization (Barrientos-Diez et al., 2021). Regarding the tendon path assumption, a naive strategy would be to consider partially and fully constrained tendons when they are guided using spacer disks and through a lumen in the backbone, respectively. However, a static model considering fully constrained tendons is proved to be accurate in predicting the shape of a TDCR composed of spacer disks in Rucker and Webster (2011a). Similarly, Norouzi-Ghazbi and Janabi-Sharifi (2020) use the partially constrained tendon path assumption to model a TDCR whose tendons are guided through lumen.

6.2 Scenario

To provide guidelines for choosing a suitable model of TDCR, we implement the most common backbone representations and tendon assumptions in the literature and compare their performances in terms of accuracy and computation speed. The corresponding models are listed in Table 2. We consider a purely kinematic model for the CC assumption which considers that the curvature of each segment of the robot is constant. It has been extensively used due to its simplicity and computational efficiency as explained by Webster and Jones (2010). While there have been closed form solutions using kinematic approaches (Gravagne and Walker, 2000c), they do not consider the backbone material properties and cannot be used for the case where an external force (e.g. gravity, weight of a tool placed at the tip, external contact) acts on the robot body, highlighting the need for consideration of other models.

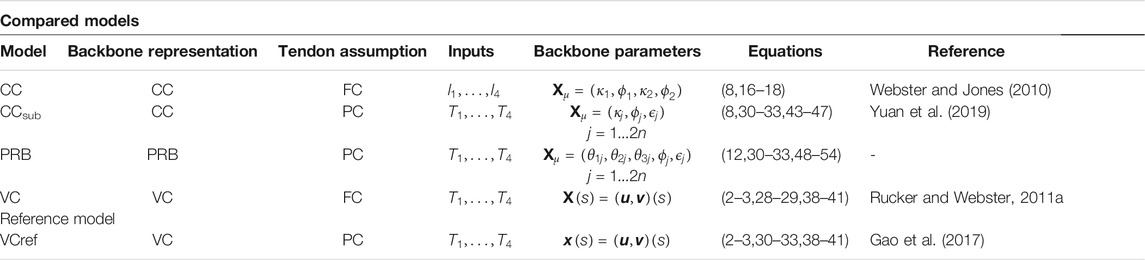

TABLE 2. Models of TDCR used in the case study. Backbone representations CC: Constant curvature, CCsub: Constant curvature assumption applied to each sub segment, PRB: Pseudo rigid body, VC: Variable curvature. Tendon assumptions FC: Fully constrained, PC: Partially constrained.

The CCsub model is a static model which considers the backbone curvature to be constant along each subsegment. The PRB and VC models are static models as well that consider pseudo rigid body and variable curvature representations respectively. We consider especially the extended PRB model including torsion. The static models have been used to model the impact of various loading conditions on the shape of TDCR (Rucker and Webster, 2011a; Huang et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2019). Their performances are compared for a relevant design of TDCR with different design parameters and in two relevant scenarios.

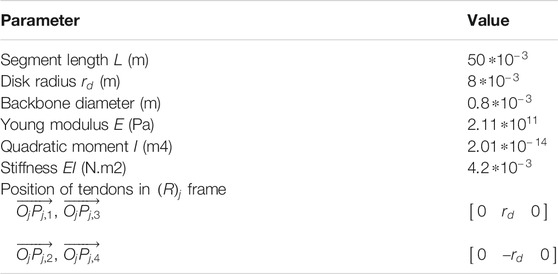

We consider a TDCR composed of two segments of length L, each segment being actuated by antagonistic pairs of tendons. We choose spacer disks to guide the tendons along the backbone, in order to reproduce the behaviour of both partially and fully constrained tendons. Indeed, the tendons are normally partially constrained along the robot backbone, and when the number of disks become large and tend to infinity, they can be assumed to be fully constrained. Each segment has n spacer disks. We assume that the weights of the disks and backbone are negligible and there are no frictional forces. The effects of the assumption on the tendon’s constraint and of the backbone representation are studied considering two scenarios, respectively. In the first, we consider that the robot is subject to tendon forces only and we vary the number of sub-segments n. For the sake of simplicity, we only consider configurations where the robot bends in a plane. Therefore, each segment is actuated with a single antagonistic pair of tendons, so that the robot bends in the

For assessing accuracy, we compare each model’s results with a reference model that is the most general in modelling a TDCR with spacer disks, making as little simplifying assumptions as possible. Thus, we employ a model that accounts for partially constrained tendons, does not make simplifying assumptions on the backbone geometry and uses the distributed parameterization. Consequently, the model uses variable curvature representation. We consider each subsegment as a rod experiencing tip forces and moments due to tendon interaction at each disk’s location, as done in Gao et al. (2017). Doing so allows us to model the behaviour of the partially constrained tendon path resulting from the use of spacer disks. As we use the VC backbone representation, we label this reference model as VCref. It uses CRT to obtain the equilibrium equations with boundary conditions at each disk given by Eq. (40), (41). The resulting forces and moments are calculated using Eq. (44) and (47). Its characteristics are listed in Table 2.

7 Method

The accuracy of a model is estimated for a given workspace of the robot. The workspace is defined here in terms of the angular displacement of the robot tip during tendon actuation. In the literature, angular displacements of up to

First, the actuation space required to achieve the desired workspace is calculated. The maximum tendon force

Therefore,

The different models are then solved for each set of actuation inputs. The CCsub, PRB, VC and VCref are solved using numerical solvers introduced in the Section 6.4. The CC model requires the tendon forces to be converted to the resulting tendon displacements for it to be solved. To do this conversion, the robot shape is computed with the VC model and the corresponding tendon length is deduced from the path followed by the tendons along the backbone (Oliver-Butler et al., 2019). The length of tendon k is written as

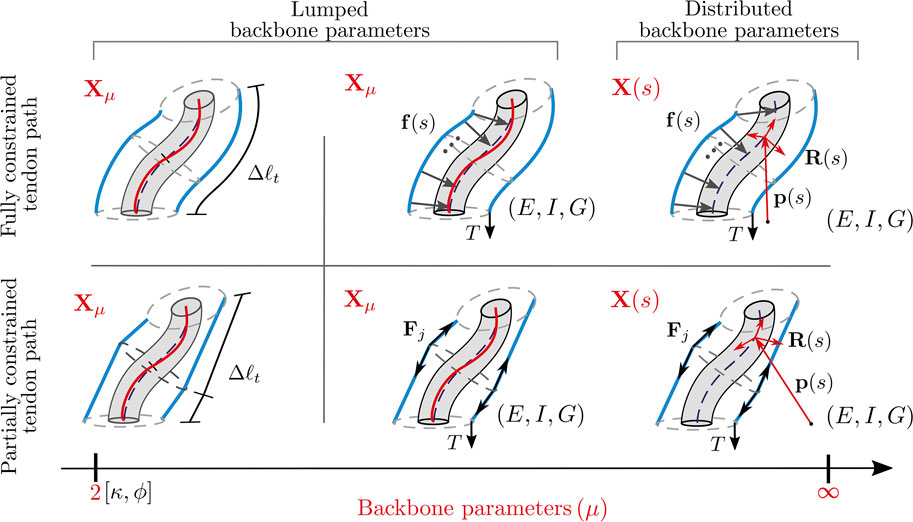

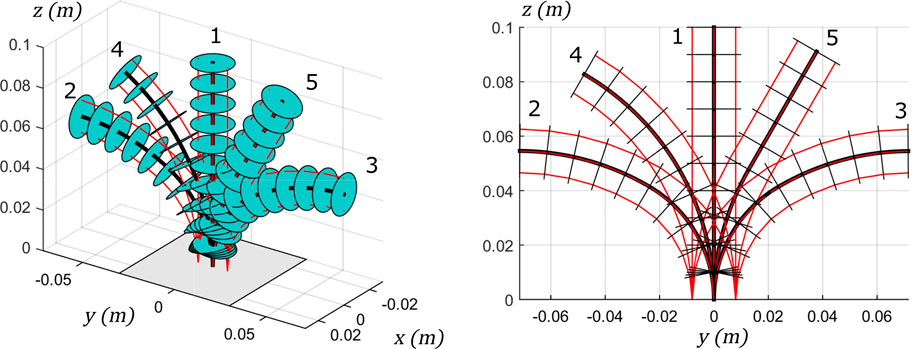

Solving the models results in 16 robot shapes per model, a subset of which is presented for the sake of clarity in Figure 9.

FIGURE 9. Subset of the TDCR configurations considered in the model comparison, for n = 5 and without external forces at the tip. Left: 3D view, Right: Planar view. Maximum or zero tendon tension is applied to each tendon for the two segments.

Finally, the robot shapes are compared to the results given by VCref. We propose the use of two metrics, denoted by

The metric

The computation time and the stability of the numerical solver are strongly dependant on the provided initial guess. Therefore, in order to perform a fair comparison in terms of computation time, similar initial guesses must be used. However, it is not possible to find a common initial guess which allows for all the models to converge for every picked configuration in the workspace. Consequently, we evaluate the computation time needed to compute one configuration only, which is configuration 2 in Figure 9. The initial guess for all the models is the robot shape without tendon or external forces, which is configuration 1 in the Figure. Each model is solved 100 times in order to filter eventual fluctuations of computation time. The values of computation time presented here are the mean values over the 100 solutions.

7.1 Implementation

We consider the modelling of a TDCR, composed of a flexible backbone and spacer disks. The robot parameters are provided in Table 3. Since we assume a frictionless system, we enforce the component of the tendon force perpendicular to the disk to be zero by computing the tendon force at each disk using the following relation

The models of TDCR and their resolution are implemented in C++ language as well as in Matlab 2015a (Mathworks Inc.). The source codes for each language are provided with this paper. In the C++ implementation, the non-linear equations composing the CCsub and PRB models are solved using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm implemented in the GNU GSL library. The resulting backbone shape is computed with Eq. (8) and (12) respectively. VC and VCref models consist in differential equations with initial and final boundary conditions and are therefore solved with a shooting method (Rucker and Webster, 2011a). In this method, the initial boundary conditions are guessed and the differential equations are integrated until the difference between the state at the robot tip and the desired final boundary condition vanishes. For the VC model, the final boundary conditions are expressed as the force and moment equilibrium at the tip of the robot, while the initial values of

In the MATLAB implementation, the CCsub, PRB and the shooting method are solved using the Trust-region-doggleg algorithm implemented in the function fsolve. The integration of the differential equations is performed using the 4th order Runge-Kutta method implemented in the ode45 solver.

8 Results and Guidelines

8.1 On the Number of Disks

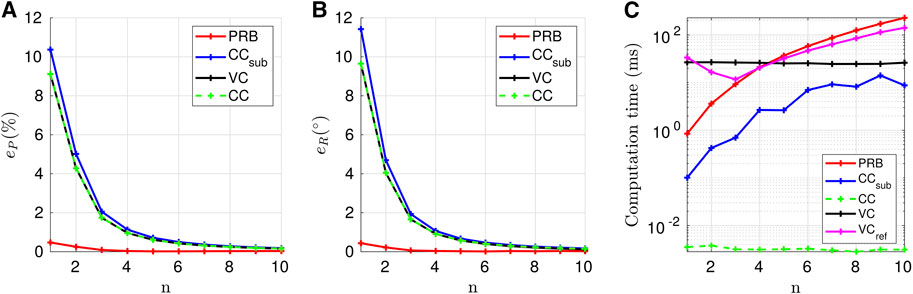

The model error values obtained for the first scenario are presented in Figures 10A,B. We observe that the number of disks has a significant effect on the robot. The tip error between the VC models with fully and partially constrained tendon reaches 9.12% with respect to the robot length for

FIGURE 10. Evolution of the models accuracy according to the number of disks per segment. The metrics

The CCsub shows a similar pattern, even though it considers the partially constrained tendons of the considered TDCR. This can be explained by the fact that the robot is deformed by moments due to the distance between the tendons and the backbone, but also by tendon forces. The lower number of disks results in longer subsegments that experience the same magnitude of tendon forces, resulting in subsegments with non-constant curvature that are not accounted for by the model. The PRB model is the most accurate in the present case study, with its error being at most 0.47% and 0.43° for

The evolution of the computation time with respect to n is presented in Figure 10C. The CC model is the fastest as it requires the lowest number of backbone parameters to compute and has an analytical solution. Its computation time is constant and equals 2.7 µs. The PRB and CCsub models present a similar tendency in terms of speed. As the number of disks increases and, consequently, the number of subsegments, the number of unknowns increases as well, resulting in higher computation times. For

From these results, we deduce the following guidelines. When considering a TDCR with spacer disks, the VCref and PRB model are the best choice due to their higher accuracy. They are particularly interesting for lower number of disks where they are also computationally efficient. For

It is as accurate as the other models for any number of disks, and is substantially faster. In cases where a static model is required due to the presence of external forces and for

8.2 On the Backbone Stiffness

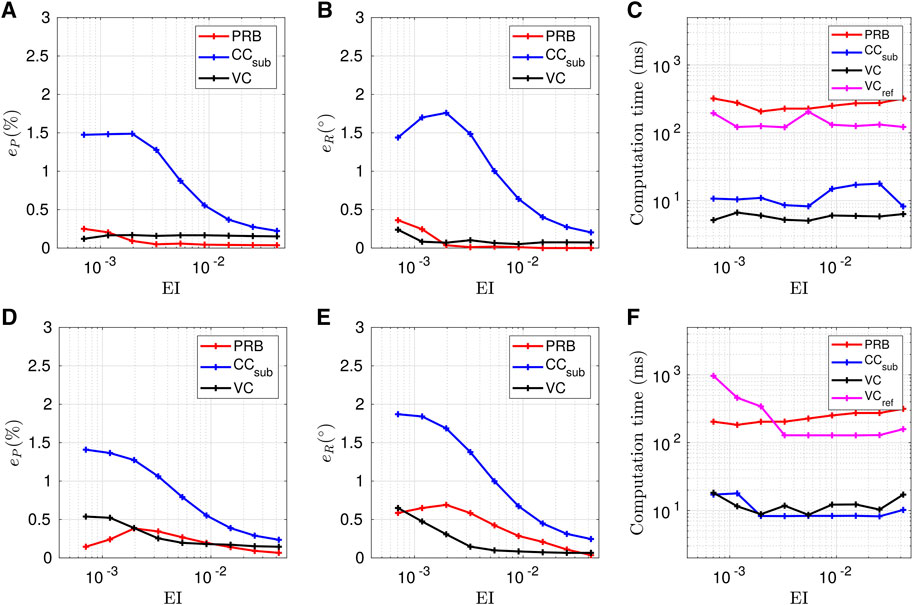

The model error values obtained for the second scenario as a function of the backbone stiffness are presented in Figure 11. The number of disks per segment is fixed at

FIGURE 11. Evolution of the models accuracy according to the backbone stiffness when considering a planar (A–C) and transverse (D–F) tip force for n = 10. The metrics

When an external tip force is applied on the TDCR, Figures 11A,B,D,E show that PRB and VC models provide results close to the reference and that the errors decrease globally as the backbone stiffness increases. For higher backbone stiffness, a larger magnitude of tendon force is required to maintain the same deflection angle. PRB and VC models give better accuracy than CCsub, especially for lower values of stiffness. In these cases, the tip force has a larger impact on the backbone shape than the bending moment due to the tendons. As a result, the curvature is not constant along the subsegments. This variation of curvature in the subsegment leads to errors up to 1.5% and 1.87°, as shown in Figures 11D,E.

The PRB model is particularly accurate for planar forces, with minimum position and orientation errors of 0.04% and 0.01° respectively, which is consistent since its parameters have been optimized for this scenario. On the other hand, it does not perform as well for non-planar deformations caused by transverse tip forces, especially in terms of tip orientation as shown in Figure 11E.

The evolution of the computation times for the two loading cases are presented in Figures 11C,F. Problems of convergence were encountered when considering the maximum tendon force

It is especially higher than the computation time of the VC model for planar tip forces, even though it was the opposite in the first scenario. This is attributed to the convergence of the CCsub and VC models which depends on the mixed tendon and external forces applied on the robot in a non-trivial manner.

From these results, we deduce the following guidelines for the case of a TDCR, subject to a tip force: In applications where model accuracy is the primary goal and planar forces are applied to the robot, the VCref and PRB models seem to be the best choice. In the case of transverse force, the VC and VCref models are the most accurate. If the computation time is also a concern, the VC model seems the most suitable in both cases. The CCsub model can also be used for stiffer backbones.

9 Discussion

In this paper, we present the existing models of TDCR using a common formalism and compare these models for the first time on a typical design of TDCR. Comparing the robot shape obtained with each model allows us to formulate guidelines for modelling a TDCR according to its design. However, finding a unified formalism poses challenges as different terminology is used in the literature to describe various models. Also, care must be taken while comparing and interpreting the results as each model is developed and evaluated for different applications and robot design. In this section, we discuss some of these difficulties to provide the reader with a better understanding of the results.

9.1 Expression of the Tendon Forces at the Disks

Writing the models with a common formalism raises two questions that have not been fully answered yet.

First, the tendon forces exerted on each disk in the case of partially constrained tendons are not expressed with the same equations in the literature. Two forces are considered to be applied at the point

Second, the question of the component of tendon forces transmitted to the backbone through the first

9.2 Comparison of TDCR Models

We discuss three major points regarding the results presented in the comparison of TDCR models.

First of all, the behaviour of obtained errors in the case study depends on the considered TDCR design. This paper considers a TDCR with spacer disks and provides guidelines according to the number of disk per segment and the backbone stiffness. While we do not consider the case of a TDCR with fully constrained tendons passing through lumens along the backbone, the provided case study can still be adapted to provide guidelines for the same. For a fully constrained tendon path, the VC model becomes the most general model and can be then be considered the reference. As a result, for the load-free scenario (see Figure 10), we can say that the robot shape can be obtained accurately and with low computation time with the CCsub and PRB model by dividing each segment into a minimum of

Second, the errors are computed with respect to a reference model, and each model is for the same set of robot parameters. The CC, CCsub, PRB and VC model can be made more accurate by individually calibrating each model’s parameters using experimental data. This calibration step is expected to give different robot parameters for each model, since they do not consider the same assumptions. Thus, we will obtain different design parameters that provide higher accuracy for a given prototype of TDCR. This calibration will allow us to account for modelling inaccuracies to some extent. For example, in Rucker and Webster, 2011a, a higher backbone stiffness than the nominal value provided by the manufacturer is obtained after calibration, which may be due to the assumption of fully constrained tendons or the presence of friction. This individual calibration has not been done in our case studies for a fair comparison and easy interpretability of results. Consequently, the reported errors can be viewed as upper bounds, with the possibility of reducing them through calibration.

Third, the values of computation time depends on the chosen method of implementation. We believe the C++ model implementations can be further optimized to increase computation speed. Moreover, the computation time also depends on the initial guess. The closer the initial guess from the desired solution, the faster the resolution of the model. In a practical scenario of deployment or trajectory tracking, where the robot tip must pass through several points

9.3 Relation Between TDCR Designs and Models

In summary, the comparative case studies show that a given design of TDCR can be modelled by considering different assumptions on the tendon path and backbone representations. The graphs not only compare the performances of some of the more common models for a TDCR design with spacer disks, but can also be used to study their performances for a design with lumen by comparing the results of each model to that of the VC model instead of VCref.

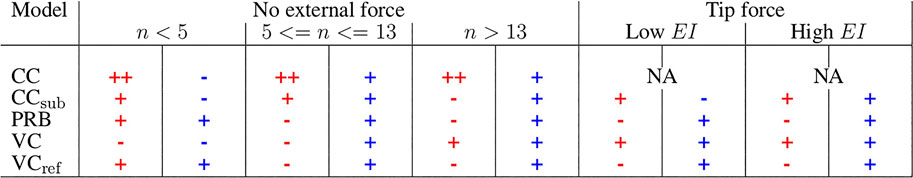

The forces and limitations of each model are summarized in Figure 12. The models have different performances in terms of accuracy and computation time depending on the loading scenarios and robot design. One interesting observation is that it is not necessary for the tendon path assumption to reflect the actual TDCR design, confirming what was already proposed by Rucker and Webster, 2011a; Norouzi-Ghazbi and Janabi-Sharifi (2020); Barrientos-Diez et al. (2021). Models assuming fully constrained tendons, such as the VC or CC models, can still accurately describe the shape of a TDCR with spacer disks when sufficient number disks is used. Similarly, models accounting for partially constrained tendons can be used for TDCR with lumen if the segments are discretized in a sufficient number of subsegments. As a result, there are various options to model a TDCR, that could potentially lead to interesting trade-off between accuracy and computation times.

FIGURE 12. Advantages (+) and limitations (−) of each model considered in the case study, in terms of accuracy (blue) and computation time (red), according to the design parameters of a TDCR composed of spacer disks. Forces and limitations for TDCR using lumen to guide the tendons can be obtained by considering the same table but reversing the accuracy ”+” and ”−” signs of the column n < 5. NA: Not applicable.

10 Conclusion and Future Research

In this paper, we aim at providing guidelines on choosing a model of TDCR according to the required tradeoff between accuracy and computation time for different design parameters. The existing modelling approaches are described in detail. They can be classified based on the parameterization of the robot backbone and the assumptions on the tendon path. They are then compared on a TDCR design composed of spacer disks, under different loading scenarios and varying design parameters.

A number of interesting results are obtained, including: 1) the superiority of PRB and VCref models for TDCR with spacer disks in terms of accuracy, 2) the superiority of the CC models in the absence of external forces, for sufficient number of disks 3) the trade-off between accuracy and computation time offered by the CCsub model.

These results inform the user about the suitable choice of model, which will be useful for future research work on TDCRs. In addition, we provide Matlab and C++ implementations of these models to allow the benchmarking of new TDCR models with respect to existing work in the literature.

Implementing and comparing these models raised a number of questions and perspectives that should be addressed in the future. The differences in tendon force expression proposed so far, discussed partly in Section 7.1, needs to be investigated. The concept of subsegment discretization needs to be further analyzed to provide the optimal number of subsegments and the associated geometrical assumptions for a given TDCR. The convergence of the modelling approaches needs also to be investigated to provide insight into selecting an initial guess that will ensure convergence and reduce the computation time. Finally, these models need to be compared to other designs of TDCRs, in particular designs with helical routing where the torsion experienced by the backbone has a significant impact on the robot shape.

Data Availability Statement

The open source implementations of all the models used in the case studies can be found on https://github.com/SvenLilge/tdcr-modeling.git.

Author Contributions

PR worked on a major part of paper writing, reviewing the current state-of-the-art and wrote the survey with uniform terminology and notation. She also helped develop the models in MATLAB. QP was responsible for writing parts of the paper, designing and evaluating the case studies, implementing and developing the MATLAB models SL worked on writing parts of the paper and implemented the models in C++. JB-K is the senior author on this paper. She conceptualized, advised, and regularly discussed research questions and results with all authors. She edited the paper. All the authors were concerned with conceptualizing and revising the paper through regular discussions on the theory and implementation details.

Funding

We acknowledge the support of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), (RGPIN-2019-04846).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Allen, T. F., Rupert, L., Duggan, T. R., Hein, G., and Albert, K. (2020). “Closed-Form Non-Singular Constant-Curvature Continuum Manipulator Kinematics,” in 3rd IEEE International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft), New Haven, CT, May 15–July 15, 2020. doi:10.1109/RoboSoft48309.2020.9116015

Altenbach, H., Bîrsan, M., and Eremeyev, V. A. (2013). “Cosserat-type rods,” in Generalized Continua from the Theory to Engineering Applications, New York: Springer Vienna, 179–248.

Amanov, E., Nguyen, T.-D., and Burgner-Kahrs, J. (2019). Tendon-driven continuum robots with extensible sections—a model-based evaluation of path-following motions. Int. J. Robot Res. doi:10.1177/0278364919886047

Ashwin, K. P., and Ghosal, A. (2021). “Forward kinematics of cable-driven continuum robot using optimization method,” in Mechanism and Machine Science, New York: Springer, 391–403. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-4477-4_27

Ashwin, K. P., and Ghosal, A. (2019). “Profile estimation of a cable-driven continuum robot with general cable routing,” in Mechanisms and Machine Science, New York: Springer, 73. 1879–1888.

Back, J., Lindenroth, L., Karim, R., Althoefer, K., Rhode, K., and Liu, H. (2016). “New kinematic multi-section model for catheter contact force estimation and steering,” in IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Daejeon, South Korea, October 9–14, 2016. doi:10.1109/IROS.2016.7759333

Barrientos-Diez, J., Dong, X., Axinte, D., and Kell, J. (2021). Real-time kinematics of continuum robots: modelling and validation. Robot. Comput. Integrated Manuf. 67, 102019. doi:10.1016/j.rcim.2020.102019

Burgner-Kahrs, J., Rucker, D. C., and Choset, H. (2015). Continuum robots for medical applications: a survey. IEEE Transactions on Robotics. 31, 1261–1280. doi:10.1109/TRO.2015.2489500

Camarillo, D. B., Loewke, K. E., Carlson, C. R., and Salisbury, J. K. (2008a). “Vision based 3-D shape sensing of flexible manipulators,” in Proceedings - IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Pasadena, CA, May 19–23, 2008. doi:10.1109/ROBOT.2008.4543656

Camarillo, D. B., Milne, C. F., Carlson, C. R., Zinn, M. R., and Salisbury, J. K. (2008b). Mechanics modeling of tendon-driven continuum manipulators. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 24, 1262–1273. doi:10.1109/TRO.2008.2002311

Chen, G., Xiong, B., and Huang, X. (2011). Finding the optimal characteristic parameters for 3R pseudo-rigid-body model using an improved particle swarm optimizer. Precis. Eng. 35, 505–511. doi:10.1016/j.precisioneng.2011.02.006

Chirikjian, G. S. (2015). Conformational modeling of continuum structures in robotics and structural biology: a review. Adv. Robot. 29, 817–829. doi:10.1080/01691864.2015.1052848 |

Dalvand, M. M., Nahavandi, S., and Howe, R. D. (2018). An analytical loading model for n-tendon continuum robots. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 34, 1215–1225. doi:10.1109/TRO.2018.2838548

Dehghani, M., and Moosavian, S. A. A. (2014a). “Finite circular elements for modeling of continuum robots,” in Second RSI/ISM International Conference on Robotics and Mechatronics, Tehran, Iran, October 15–17, 2014 (IEEE). doi:10.1109/ICRoM.2014.6990948

Dehghani, M., and Moosavian, S. A. A. (2014b). “Statics modeling of planar continuum robots using virtual energy method,” in Second RSI/ISM International Conference on Robotics and Mechatronics, (Tehran, IEEE). doi:10.1109/ICRoM.2014.6990947

Dehghani, M., and Moosavian, S. A. A. (2011). “Modeling and control of a planar continuum robot,” in IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent mechatronics, Budapest, Hungary, July 3–7, 2011, (IEEE). doi:10.1109/AIM.2011.6027137

Dehghani, M., and Moosavian, S. A. A. (2013a). “Modeling of continuum robots with twisted tendon actuation systems,” in First RSI/ISM International Conference on Robotics and mechatronics, Tehran, Iran, February 13–15, 2013, (IEEE), doi:10.1109/ICRoM.2013.6510074

Dehghani, M., and Moosavian, S. A. A. (2013b). “Static modeling of continuum robots by circular elements,” in 21st Iranian Conference on Electrical Engineering, Mashhad, Iran, May 14–16, 2013, (IEEE). doi:10.1109/IranianCEE.2013.6599741

Do, T., Tjahjowidodo, T., Lau, M., and Phee, S. (2015). A new approach of friction model for tendon-sheath actuated surgical systems: nonlinear modelling and parameter identification. Mech. Mach. Theor. 85, 14–24. doi:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2014.11.003

Gao, A., Zou, Y., Wang, Z., and Liu, H. (2017). A general friction model of discrete interactions for tendon actuated dexterous manipulators. J. Mech. Robot. 9, 4036719. doi:10.1115/1.4036719

Giorelli, M., Renda, F., Calisti, M., Arienti, A., Ferri, G., and Laschi, C. (2015). Neural network and jacobian method for solving the inverse statics of a cable-driven soft arm with nonconstant curvature. IEEE Transactions on Robotics. 31, 823–834. 10.1109/TRO.2015.2428511

Godage, I. S., Medrano-Cerda, G. A., Branson, D. T., Guglielmino, E., and Caldwell, D. G. (2015). Modal kinematics for multisection continuum arms. Bioinspir. Biomim. 10, 035002. doi:10.1088/1748-3190/10/3/035002 |

Godage, I. S., Medrano-Cerda, G. A., Branson, D. T., Guglielmino, E., and Caldwell, D. G. 2015). Modal kinematics for multisection continuum arms. In Bioinspir Biomim, 10. 035002–1422. doi:10.1088/1748-3190/10/3/035002 |

Godage, I. S., Branson, D. T., Guglielmino, E., Medrano-Cerda, G. A., and Caldwell, D. G. (2011a). “Shape function-based kinematics and dynamics for variable length continuum robotic arms, in IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom., Shanghai, China, May 9–13, 2011. doi:10.1109/ICRA.2011.5979607

Godage, I. S., Guglielmino, E., Branson, D. T., Medrano-Cerda, G. A., and Caldwell, D. G. (2011b). “Novel modal approach for kinematics of multisection continuum arms,” in IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and systems, San Francisco, CA, September 25–30, 2011. doi:10.1109/IROS.2011.6094477

Goldman, R. E., Bajo, A., and Simaan, N. (2014). Compliant motion control for multisegment continuum robots with actuation force sensing. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 30, 890–902. doi:10.1109/TRO.2014.2309835

Gravagne, I. A., and Walker, I. D. (2002). Manipulability, force, and compliance analysis for planar continuum manipulators. IEEE Trans. Rob. Autom. 18, 263–273. doi:10.1109/tra.2002.1019457 |

Gravagne, I., Rahn, C., and Walker, I. (2003a). Large deflection dynamics and control for planar continuum robots. IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatron. 8, 299–307. doi:10.1109/TMECH.2003.812829

Gravagne, I. A., Rahn, C. D., and Walker, I. D. (2003b). Large deflection dynamics and control for planar continuum robots. IEEE Trans. Rob. Autom. 8, 299–307. doi:10.1109/TMECH.2003.812829

Gravagne, I., and Walker, I. (2000a). Kinematic transformations for remotely-actuated planar continuum robots. in IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. San Francisco, CA, April 24–26, 2000. doi:10.1109/ROBOT.2000.844034

Gravagne, I., and Walker, I. D. (2000b). “Kinematics for constrained continuum robots using wavelet decomposition,” in Proceedings of the 4th International Conference and Exposition on Robotics for Challenging Situations and Environments, 299, 292–298. doi:10.1061/40476(299)38

Gravagne, I. A., and Walker, I. D. (2000c). “On the kinematics of remotely-actuated continuum robots,” in Proceedings - IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, San Francisco, CA, April 24–28, 2000c. doi:10.1109/ROBOT.2000.846411

Hannan, M. W., and Walker, I. D. (2003). Kinematics and the implementation of an elephant's trunk manipulator and other continuum style robots. J. Robot. Syst. 20, 45–63. doi:10.1002/rob.10070 |

Hemami, A. (1985). Studies on a light weight and flexible robot manipulator. Robotics 1, 27–36. doi:10.1016/S0167-8493(85)90306-7

Hsiao, K., and Mochiyama, H. (2017). “A wire-driven continuum manipulator model without assuming shape curvature constancy,” in IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Vancouver, BC, September 24–27, 2017. doi:10.1109/IROS.2017.8202190

Huang, S., Meng, D., She, Y., Wang, X., Liang, B., and Yuan, B. (2018). Statics of continuum space manipulators with nonconstant curvature via pseudorigid-body 3R model. IEEE Access. 6, 70854–70865. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2881261

Huang, S., and Meng, D., Wang, X., Liang, B., and Lu, W. (2019). “A 3D Static Modeling Method and Experimental Verification of Continuum Robots Based on Pseudo-Rigid Body Theory,” in IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Macau, China, November 3–8, 2019. doi:10.1109/IROS40897.2019.8968526

Immega, G., and Antonelli, K. (1995). The KSI tentacle manipulator. IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. 3, 3149–3154. doi:10.1109/ROBOT.1995.525733

Jones, B. A., and Walker, I. D. (2006a). Practical kinematics for real-time implementation of continuum robots. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 22, 1087–1099. doi:10.1109/TRO.2006.886268

Jones, B. A., and Walker, I. D. (2006b). Kinematics for multisection continuum robots. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 22, 43–55. doi:10.1109/TRO.2005.861458

Jones, B. A., Gray, R. L., and Turlapati, K. (2009). “Three dimensional statics for continuum robotics,” in IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, St. Louis, MO, October 10–15, 2009. doi:10.1109/IROS.2009.5354199

Jung, J., Penning, R. S., Ferrier, N. J., and Zinn, M. R. (2011). A modeling approach for continuum robotic manipulators: Effects of nonlinear internal device friction. in IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Francisco, CA, September 25–30, 2011. doi:10.1109/IROS.2011.6094941

Kato, T., Okumura, I., Kose, H., Takagi, K., and Hata, N. (2016). Tendon-driven continuum robot for neuroendoscopy: validation of extended kinematic mapping for hysteresis operation. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 11, 589–602. doi:10.1007/s11548-015-1310-2 |

Kato, T., Okumura, I., Song, S. E., Golby, A. J., and Hata, N. (2015). Tendon-driven continuum robot for endoscopic surgery: preclinical development and validation of a tension propagation model. IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatron. 20, 2252–2263. doi:10.1109/TMECH.2014.2372635 |

Khoshnam, M., Khalaji, I., and Patel, R. V. (2015). “A robotics-assisted catheter manipulation system for cardiac ablation with real-time force estimation,” in IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and systems (IROS), Hamburg, Germany, September 28–October 2, 2015 (IEEE). doi:10.1109/IROS.2015.7353821

Kutzer, M. D., Segreti, S. M., Brown, C. Y., Taylor, R. H., Mears, S. C., and Armand, M. (2011). Design of a new cable-driven manipulator with a large open lumen: Preliminary applications in the minimally-invasive removal of osteolysis. in Proceedings - IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, May 9–13, 2011. doi:10.1109/ICRA.2011.5980285

Li, C., and Rahn, C. D. (2002). Design of continuous backbone, cable-driven robots. J. Mech. Des. 124, 265–271. doi:10.1115/1.1447546

Mahl, T., Mayer, A. E., and Hildebrandt, A., and Sawodny, O. (2013). “A variable curvature modeling approach for kinematic control of continuum manipulators,” in Proceedings of the American Control Conference, Washington, DC, June 17–19, 2013. doi:10.1109/ACC.2013.6580605

Mishra, A., Mondini, A., Del Dottore, E., Sadeghi, A., Tramacere, F., and Mazzolai, B. (2018). Modular continuum manipulator: analysis and characterization of its basic module. Biomimetics 3, 3. doi:10.3390/biomimetics3010003

Norouzi-Ghazbi, S., and Janabi-Sharifi, F. (2020). Dynamic modeling and system identification of internally actuated, small-sized continuum robots. Mech. Mach. Theor. 154, 104043. doi:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2020.104043

Oliver-Butler, K., Till, J., and Rucker, C. (2019). Continuum robot stiffness under external loads and prescribed tendon displacements. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 35, 403–419. doi:10.1109/TRO.2018.2885923

Ouyang, B., Liu, Y., and Sun, D. (2016). Design of a three-segment continuum robot for minimally invasive surgery. Robotics Biomim. 3, 2. doi:10.1186/s40638-016-0035-1 |

Peirs, J., Reynaerts, D., Van Brussel, H., De Gersem, G., and Tang, H.-W. (2003). “Design of an advanced tool guiding system for robotic surgery, in IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Taipei, Taiwan, September 14–19, 2003. doi:10.1109/ROBOT.2003.1241993

Renda, F., and Laschi, C. (2012). “A general mechanical model for tendon-driven continuum manipulators,” in Proceedings - IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Saint Paul, MN, May 14–18, 2012. doi:10.1109/ICRA.2012.6224703

Roesthuis, R. J., and Misra, S. (2016). Steering of multisegment continuum manipulators using rigid-link modeling and FBG-based shape sensing. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 32, 372–382. 10.1109/TRO.2016.2527047

Rone, W. S., and Ben-Tzvi, P. (2014a). Continuum robot dynamics utilizing the principle of virtual power. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 30, 275–287. doi:10.1109/TRO.2013.2281564

Rone, W. S., and Ben-Tzvi, P. (2014b). Mechanics modeling of multisegment rod-driven continuum robots. J. Mech. Robot. 6, 4027235. doi:10.1115/1.4027235

Rone, W. S., and Ben-Tzvi, P. (2013). “Multi-segment continuum robot shape estimation using passive cable displacement,” in IEEE International Symposium on Robotic and Sensors Environments (ROSE). Washington, DC, October 21–23, 2013. doi:10.1109/ROSE.2013.6698415

Rucker, C. (2018). Integrating rotations using nonunit quaternions. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 3, 2979–2986. doi:10.1109/LRA.2018.2849557

Rucker, D. C., and Webster, R. J. (2011a). Statics and dynamics of continuum robots with general tendon routing and external loading. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 27, 1033–1044. doi:10.1109/TRO.2011.2160469

Rucker, D. C., and Webster, R. J. (2011b). “Deflection-based force sensing for continuum robots: A probabilistic approach,” in IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Francisco, CA, September 25–30, 2011. doi:10.1109/IROS.2011.6094526

Ryu, J., Ahn, H. Y., Kim, H. Y., and Ahn, J. H. (2019). Analysis and simulation of large deflection of a multi-segmented catheter tube under wire tension. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 33, 1305–1310. doi:10.1007/s12206-019-0231-3

Santina, C. D., and Rus, D. (2020). Control oriented modeling of soft robots: the polynomial curvature case. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 5, 290–298. doi:10.1109/LRA.2019.2955936

Simaan, N., Xu, K., Kapoor, A., Wei, W., Kazanzides, P., Flint, P., et al. (2009). Design and integration of a telerobotic system for minimally invasive surgery of the throat. Int. J. Rob. Res. 28, 1134–1153. doi:10.1177/0278364908104278 |

Simaan, N., Taylor, R., and Flint, P. (2004). “A dexterous system for laryngeal surgery,” in IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, New Orleans, LA, April 26–May 1, 2004. doi:10.1109/ROBOT.2004.1307175

Starke, J., Amanov, E., Chikhaoui, M. T., and Burgner-Kahrs, J. (2017). On the merits of helical tendon routing in continuum robots. in IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems., Vancouver, BC, September 24–28, 2017. doi:10.1109/IROS.2017.8206554

Su, H. J. (2009). A pseudorigid-body 3r model for determining large deflection of cantilever beams subject to tip loads. J. Mech. Robot. 1, 1–9. 10.1115/1.3046148

Till, J., Aloi, V., and Rucker, C. (2019). Real-time dynamics of soft and continuum robots based on Cosserat rod models. Int. J. Robot. Res. 38, 723–746. doi:10.1177/0278364919842269

Walker, I. D., Choset, H., and Chirikjian, G. S. (2016). Snake-like and continuum robots. in Springer Handbook of Robotics Cham: Springer International Publishing. 481–498.

Walker, I. D. (2013). Continuous backbone “continuum” robot manipulators. ISRN Robotics. 2013, 1. doi:10.5402/2013/726506

Webster, R. J., and Jones, B. A. (2010). Design and kinematic modeling of constant curvature continuum robots: a review. Int. J. Robot. Res. 29, 1661–1683. doi:10.1177/0278364910368147

Xu, K., Zhao, J., and Fu, M. (2015). Development of the SJTU unfoldable robotic system (SURS) for single port laparoscopy. IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatron. 20, 2133–2145. doi:10.1109/TMECH.2014.2364625

Xu, W., Chen, J., Lau, H. Y. K., and Ren, H. (2017). Data-driven methods towards learning the highly nonlinear inverse kinematics of tendon-driven surgical manipulators. Int. J. Med. Robot. 13, e1774. doi:10.1002/rcs.1774

Yuan, H., and Li, Z. (2018). Workspace analysis of cable-driven continuum manipulators based on static model. Robot. Comput. Integrated Manuf. 49, 240–252. doi:10.1016/j.rcim.2017.07.002

Keywords: soft manipulator, soft arm, tendon actuation, modelling, soft robot

Citation: Rao P, Peyron Q, Lilge S and Burgner-Kahrs J (2021) How to Model Tendon-Driven Continuum Robots and Benchmark Modelling Performance. Front. Robot. AI 7:630245. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2020.630245

Received: 17 November 2020; Accepted: 22 December 2020;

Published: 02 February 2021.

Edited by:

Matteo Cianchetti, Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies, ItalyReviewed by:

Ashwin K. P., FeatherDyn Pvt Ltd., IndiaKristin M. De Payrebrune, University of Kaiserslautern, Germany

Copyright © 2021 Rao, Peyron, Lilge and Burgner-Kahrs. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Priyanka Rao, cHJpeWFua2FwcmFrYXNoLnJhb0BtYWlsLnV0b3JvbnRvLmNh

Priyanka Rao

Priyanka Rao Quentin Peyron

Quentin Peyron Sven Lilge

Sven Lilge Jessica Burgner-Kahrs

Jessica Burgner-Kahrs