- 1Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States

- 2Impact Research and Development Organization, Kisumu, Kenya

- 3Duke Global Health Institute, Durham, NC, United States

- 4Department of Pediatrics, Infectious Diseases, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, United States

- 5Population Council, Lusaka, Zambia

- 6Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

- 7International Research Center of Excellence, Institute of Human Virology Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria

- 8Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, School of Medical Sciences, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana

- 9Global Pediatrics Program and Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN, United States

- 10Department of Internal Medicine & Makerere University Joint AIDS Program, College of Health Sciences Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

- 11Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Pediatrics, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 12Department of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 13Hubert Department of Global Health, Emory University Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA, United States

Background: The Fogarty International Center-led Adolescent HIV Implementation Science Alliance (AHISA) supports region-/country-specific implementation science (IS) alliances that build collaborations between research, policy, and program partners that respond to local implementation challenges. AHISA supported the development of seven locally-led IS alliances: five country-specific (i.e., Kenya, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia), one in Central and West Africa, and one with youth researchers. This article outlines the aims, activities, and outcomes of local alliances, demonstrating how they enhance sustainable IS activities to address local challenges.

Methods: We conducted a desk review of each alliance's funding applications, reports, and data from the initial findings of a larger AHISA evaluation. The review analyzes common approaches, highlights their local relevance, and summarizes initial outcomes.

Results: The local alliances have a common goal: to expand implementation of successful interventions to improve adolescent HIV. We identified four overarching themes across the local alliances’ activities: capacity building, priority setting, stakeholder engagement, and knowledge dissemination. Research capacity building activities include long-term mentorship between junior and senior researchers and short-term training for non-research partners. Setting priorities with members identifies local research needs and streamlines activities. Alliances incorporate substantial engagement between partners, particularly youth, who may serve as leaders and co-create activities. Dissemination shares activities and results broadly.

Conclusion: Local IS alliances play a key role in building sustainable IS learning and collaboration platforms, enabling improved uptake of evidence into policy and programs, increased IS research capacity, and shared approaches to addressing implementation challenges.

Introduction

Reducing the rates of adolescent HIV hinges on the successful implementation of effective interventions to decrease transmission and improve treatment outcomes. It calls for tailored, evidence-based approaches to address the unique needs of adolescents and responds to the specific context in which they live. Implementation science (IS) holds promises for addressing these challenges by improving the understanding of barriers to health programming, effective implementation strategies, and facilitators of adoption and uptake of interventions that work (1).

The Adolescent HIV Implementation Science Alliance (AHISA), a learning collaborative made up of a network of researchers, policymakers, program implementers, and youth that promotes the use of IS to enhance uptake of evidence and overcome implementation challenges related to the prevention and treatment of HIV among adolescents in Africa (2). AHISA is comprised of 26 teams of NIH-supported implementation researchers and their in-country partners working across 11 African countries. To bolster sustainability and local relevance, AHISA supports locally led projects aimed at decentralizing knowledge creation, building IS capacity, promoting equitable partnerships, and contributing to the sustainability of IS activities (3). The overall objective of supporting these projects is to develop a learning ecosystem for IS activities that link available IS research evidence to local practice and policy, thereby making the science and its outcomes more accessible, locally relevant, and potentially sustainable.

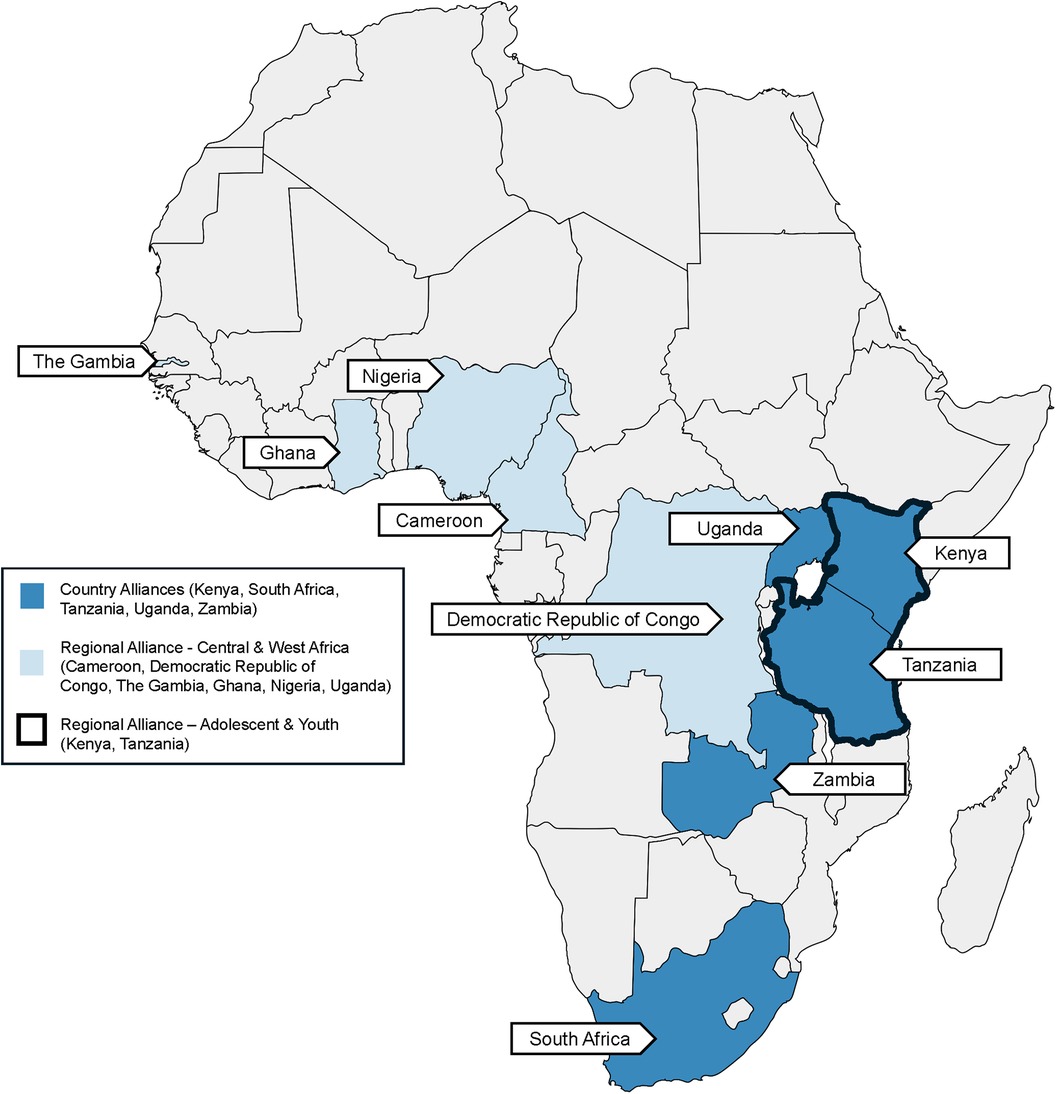

Since 2019, AHISA has supported the development of seven country- and region-specific IS alliances anchored in building collaboration between research, policy, and programs that are able to respond to local implementation and IS research challenges. Five are country specific- Kenya (KAHISA), South Africa [AHI(SA)2], Tanzania (TAHISA), Uganda (UAHISA), and Zambia (ZAHISA)- one focuses on the Central and West Africa region (CAWISA), and one is centered on youth researchers in East and Southern African (African Youth IS Alliance, AYISA). These alliances leverage the AHISA model and represent an investment aimed at building sustainability and responsiveness to local implementation and implementation science challenges and needs. These local alliances catalyze various activities that are aligned with local priorities, programmatic needs, and policy questions thereby creating unique opportunities to scale-up and sustain the implementation research evidence generated by network members.

This approach is modeled on the successful Nigeria Implementation Science Alliance (NISA), a collaborative IS consortium of 20 local organizations, universities, and government agencies in Nigeria (4). NISA was established in 2015 and was an outcome of the Fogarty-led NIH-PEPFAR Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) Implementation Science Alliance (5). NISA meets annually, with attendance at each meeting by the federal and state health personnel, including the Nigerian Minister of Health. NISA represents an important and self-sustaining extension of the work of the PMTCT Alliance and provides a platform for Nigerian researchers, program implementers, and policymakers to identify and/or generate evidence and implementation strategies that address critical local implementation challenges (6).

Adapting this model, each of the seven AHISA local alliances identifies country and regionally specific implementation issues and seeks innovative solutions through dynamic learning platforms that leverage IS methods. They convene partners to develop priorities, discuss successes and challenges in implementation, set agendas for alliance activities, and share research results. By encouraging a local focus, these alliances are more nimble and agile than the larger AHISA network in addressing local policies and priority health areas in their focus country/countries.

This article describes the aims, activities, outputs, and outcomes of the local alliances to illustrate how they enhance the potential for sustainable IS activities that address local implementation challenges. It explores their unique approaches and reflects on the role that country- and regional alliances can play in the future of IS.

Methods

Data was gathered from desk reviews of applications, final reports, and documents from April 2019 to January 2024, alongside a preliminary AHISA evaluation outlining local alliance deliverables, outcomes, and impacts. Two authors (SV, RS) coded the documents by hand in excel using a codebook developed based on discussions held at the AHISA annual meetings on the commonalities and themes across the alliances and in response to the key research questions (Appendix 1) to extract the relevant information related to their goals and activities, the role of IS, and their engagement practices. Discrepancies in the data were discussed until there was a consensus. One author (SV) did an initial analysis of the final data to create broad themes; these were shared and discussed by all authors to further refine and decide on key examples. The review provides an analysis of the commonalities between the alliance approaches, illustrates their relevance to the local context, and contributions to sustainable IS activities.

Findings

All seven AHISA local alliances have a common overarching goal: to expand the implementation of successful interventions focused on improving HIV prevention and care. A key principle of each of the alliances is to foster dialogue and learning between researchers, HIV program implementers, youth, and policymakers. Additional critical priorities of each alliance include building IS capacity, identifying evidence-based interventions to support response strategies, and enhancing translation of evidence into policy and practice. All the alliances are led by a leadership team comprised of AHISA members, IS experts, and other invested parties that meet regularly to ensure alliance activities continue to meet local needs and are achieving their intended outcomes.

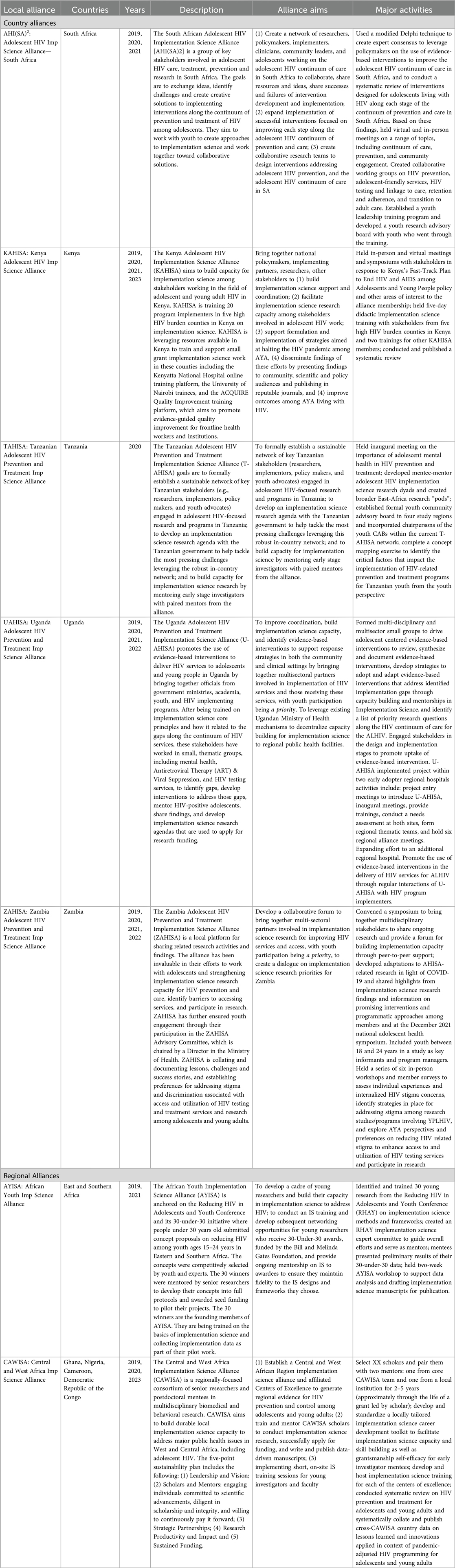

Though the overall goal is the same, their models and activities differ (Table 1. AHISA Local Alliances’ Goals and Activities; Figure 1. Map of Local Alliances). For instance, some are focused on responding to specific Ministry of Health policy questions (ZAHISA), while others are focused on creating a platform for learning and communication among IS researchers [AHI(SA)2] or prioritize supporting research independence and have created long-term mentorship for local researchers (CAWISA). All of the alliances are nimble and responsive to evolving local needs. This is illustrated in their evolving foci and activities over time as they, for example, push into new provinces or expand their alliance to include new partners. The following section describes the findings from a review of their activities and outcomes across four common categories: (1) capacity building; (2) priority setting; (3) dissemination; and (4) engagement practices.

Capacity building

Aligned with the overall AHISA goal of building IS capacity, five of the local alliances engage in robust capacity building activities. A key common component of these efforts is support for mentorship, pairing junior researchers with more established implementation scientists. For instance, AYISA partnered with members of the Fogarty-funded Improving the HIV Care Cascade in Kenya through Implementation Science Training (7) at Kenyatta National Hospital to provide training and mentorship to young research mentees from East and Southern Africa who were selected to join the Gates-supported 30-under-30 research program as part of the Reducing HIV in Adolescents and Youth (RHAY). AYISA and Kenyatta National Hospital offered stand-alone IS training to young people and also provided IS training as part of the 2022 RHAY conference. Each of the 30 winners meets regularly with a senior researcher who mentor them to develop full protocols, obtain approvals from ethics and other regulatory bodies in their respective countries, pilot their projects, and write up the results for peer-reviewed publications. As a result, the scholars added IS objectives to their study designs allowing them to collect implementation data that would inform policy considerations for projects that show impact.

Local alliances also commonly provide short-term training opportunities in IS. Many of the trainings included alliance members new to IS, including non-research partners from the Ministry of Health and program implementing organizations (KAHISA, UAHISA) and junior researchers (CAWISA), or trained youth as a lead up to developing a youth research advisory group [AHI(SA)2]. To ensure local relevance, several of the alliances develop and tailor training materials to the specific context by adapting existing trainings (KAHISA), developing new curriculum (UAHISA), and/or working with local partners on the content and delivery (CAWISA). The capacity building efforts sometimes lead to a specific outcome or an activity that allows the new members to apply their learning and advance the goals of the local alliance. For example, as part of a series of monthly trainings, UAHISA sub-groups developed a list of priority research questions through a process of identifying implementation gaps and potential evidence-based interventions related to their respective thematic areas along the HIV continuum of care for adolescents and young persons.

In many cases, training is paired with mentorship opportunities, enhancing the overall learning experience for participants. For instance, CAWISA pairs postdoctoral mentees in multidisciplinary biomedical and behavioral research with two senior research mentors. The CAWISA mentees are trained and mentored to conduct IS research, successfully apply for funding, and write and publish data-driven manuscripts. The CAWISA leadership team co-developed an IS curriculum content and learning objectives tailored to Central and West African country contexts and assembled an online, open-access ScholarIS toolkit that is pending release. As part of the training, mentees brainstorm small IS projects to work on with their mentors and are put into collaborative writing groups consisting of mentors and mentees to further learn from each other.

IS training fosters a common language that enables researchers and non-researchers to collaborate more effectively on challenges, understand the potential of IS to address those challenges, and leverage the evidence generated. For example, KAHISA led an online IS training for the Ministry of Health and HIV implementing partners from five counties with the highest HIV burden in Kenya, including Kisumu, Homabay, Siaya, Nairobi and Migori. With input from the University of Washington, the team adapted the training curriculum from one developed by the Department of Research and Program at the Kenyatta National Hospital. In total, 20 participants, identified by their respective county chief officers of health, took part in the training. After, they were paired with a local mentor to develop IS proposals that assessed the feasibility of proposed interventions and implementation strategies. Projects ranged from adherence counseling for adolescents with viral failure to quality improvement of Pre exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to a transition readiness assessment for adolescents moving to adult care. Along the way, trainees participated in KAHISA-led symposiums to share results. They also continued their learning through trainings on dissemination strategies including how to develop policy brief and engaging presentation at scientific and non-scientific forums.

Priority setting

A major part of the local alliance approaches has been identifying priority areas to utilize IS to answer pressing questions related to the implementation of proven interventions for adolescent HIV. This leverages the collective wisdom of the group and their multiple perspectives. Most of the priority setting is done in the lead up to deciding on alliance activities, and many have continued to reflect on key areas as the HIV context evolves. Some have also expanded these efforts to new locations (as UAHISA did when they grew from the capital city to new regional referral hospitals and program implementers) or additional health areas considering new developments. For example, ZAHISA held symposiums as part of national health research conferences and workshops on understanding trends in service utilization and access during COVID, as these needs and opportunities arose. It has also facilitated learning between partners and youth engaged in IS activities through national mapping of IS research and giving youth, including those living with HIV, a voice. Other alliances focused on specific topics within the larger adolescent HIV IS field, developing themes and leveraging the unique perspective and expertise of alliance members to address the themes. For example, UAHISA created thematic groups based on members’ interests and expertise that looked at challenges and opportunities to use IS across the HIV continuum of care specific to adolescents. These groups have met regularly for training and to identify evidence-based interventions and successful implementation strategies. In addition, they hold partnership meetings with USAID, CDC, and community health departments to consider how to integrate their findings into routine care.

Priority setting approaches have varied from the utilization of systematic DELPHI [AHI(SA)2] (8) and study mapping (KAHISA) to surveys and key informant interviews (ZAHISA) and to workshops that gather real time input from their multi-sector members (TAHISA). These activities involve substantial engagement with their members, providing opportunities to analyze gaps, identify existing evidence-based interventions, and develop implementation research questions. Given the nature of the alliances’ engagement with non-research partners, these identified priorities are often more locally grounded in policy and programmatic context.

Dissemination

There is recognition across the local alliances that disseminating alliance learning is key to ensuring that research evidence is used to inform policy and programs. Some alliances provided specific training on dissemination to non-research audiences including how to write a policy brief with practice presenting to Ministry of Health officials (KAHISA). Others meet with stakeholder groups beyond the alliance membership to ensure their engagement (UAHISA). Many share results and on-going activities among their members, both in-person and virtually, allowing them to learn from each other and ensure they are working towards the goals of the alliance. There is also a substantial emphasis on training early-stage investigators to write publishable manuscripts including CAWISA that developed writing groups to support each other's efforts and AYISA that is holding virtual meetings with the RHAY 30-U-30 awardees on manuscript writing.

Dissemination activities are often driven by priority setting efforts. For instance, TAHISA held an initial research priority setting workshop with researchers, implementers, policymakers, and youth advocates to identify local needs around adolescent mental health and HIV and the role research can play in addressing those issues. Along with developing alliance objectives, they highlighted the need to incorporate youth in the decision making around any activities that concern them. As a result, a youth advocate presented at the Tanzania Commission for AIDS sub-group on adolescent and gender in reproductive health and continues to represent the alliance at relevant meetings and conferences. Members of AYISA have also presented their pilot work at local and international conferences, with one published in a peer-reviewed journal (9) and others at various stages of development.

Engagement practices

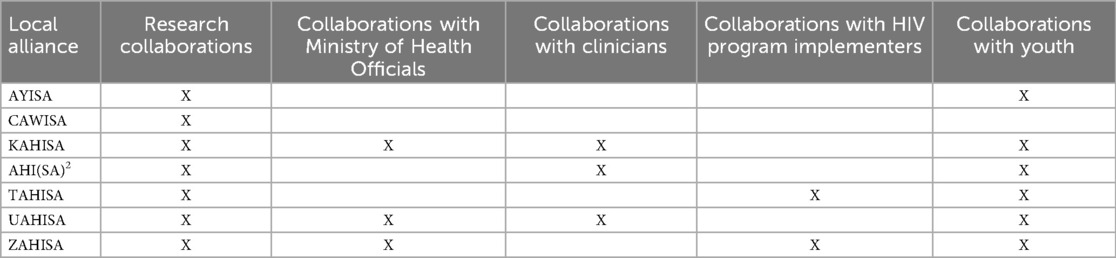

The alliance model is premised on the concept of catalyzing and supporting communication, collaboration, and learning between researchers and users of research evidence including youth, ministry officials, and program implementers, among others (Table 2. Engagement Efforts Across the Local AHISA Alliances). Some local alliances have integrated these groups into the leadership of the alliance while others started with researchers and have expanded engagement to include youth and policymakers not originally part of the group. Beyond leadership teams, diverse community groups have joined and actively participated in collaborative working groups.

Government ministries, particularly ministries of health, have played an active and sometimes leadership role in six of the alliances. For instance, the Ministry of Health Assistant Director in charge of Adolescent Health chairs the ZAHISA Technical Advisory Committee, which also includes a youth advisory panel, that identifies gaps and needs and reviews and provides guidance on the alliance's effort. The youth voices through this engagement have also helped to identify barriers to accessing services by youth, which helps to further shape IS research questions. The County Government of Kisumu's Ministry of Health helped plan for and offered outreach services during the initial RHAY Conference which AYISA was part of. Ministries, both federal and local, are also a key group that alliances have targeted for dissemination. This has included invitations to workshops and symposiums as well as special outreach specifically to these groups. For instance, TAHISA has sent members to participate in ongoing Ministry of Health groups and KAHISA had training to develop materials for stakeholder groups including Ministry of Health and local community. UAHISA has developed three regional groups of health care providers and a USAID-funded program implementing partners and paired them with IS mentors to conduct activities related to thematic areas identified by the regional alliance members.

Along with the policymakers, many of the alliances emphasize the importance of including youth throughout their efforts. Across many alliances, youth are active and fully engaged members. AHI(SA)2 first trained ten youth in research methodology, ethics, and IS. These youth now act as an advisory board to researchers, implementation scientists, and community programs as they develop new proposals or implementation of new programs. AHI(SA)2 members and their colleagues are encouraged to submit grant proposals, research protocols, or intervention manuals to the youth advisory board for input and feedback. AYISA also had youth serve as reviewers in their proposal selection process and engaged an all-youth secretariat to guide the awardees through all 30-U-30 processes, while TAHISA has engaged youth as equal partners in the alliance and invited youth collaborators to be part of the Tanzania commission for AIDS. TAHISA worked with their youth community advisory boards across four different Tanzanian regions to prioritize health challenges faced by young people and identify their recommended strategies and solutions. These findings were presented by youth to the Tanzania Ministry of Health and published in Frontiers of Public Health in 2024 (10).

The local alliances have also used the larger AHISA annual meetings and activities to learn from each other and further build relationships and collaboration. Each year at the annual AHISA forum, the local alliances share their aims and activities and have an opportunity to discuss challenges. They report that this forum has been key to exploring new possibilities and refining their work as well as developing new research projects. For example, a collaboration between UAHISA and KAHISA investigators resulted in the development of a new research proposal.

Outcomes

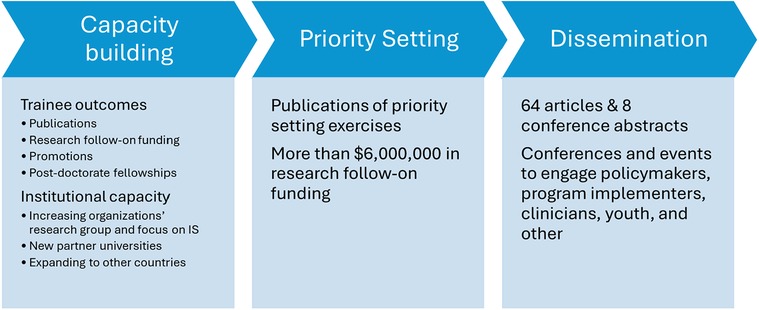

There are already several exciting outcomes from the local alliances demonstrating their value to building capacity for IS, using IS to address local challenges, and anchoring sustainable activities locally (Figure 2. Key Accomplishments of the Local HIV Implementation Science Alliances).

Capacity building outcomes

In total, the local alliances report training 134 people. Of those, over a third were youth (35.8%) and about a third were health policy administrators (29.9%). Over 70% of these were trained through the local alliances in short-term training in contrast to the long-term mentorship programs, like CAWISA, that included only eight trainees. One member of KAHISA conducted a quality improvement project under KAHISA mentorship that was recently accepted for a poster presentation and registration scholarship at the International AIDS Conference in 2024. All 30 of the AYISA trainees went on to conduct their pilot studies. While many are still analyzing data, one recently had their manuscript published in PLOS Global Public Health (9) and over 10 abstracts have been presented at international conferences. Another worked with their mentor to receive a research planning grant from the NIH National Cancer Institute on using electronic reminders for HPV vaccinations (11). Trainees have advanced their careers with one receiving a scholarship for a master's program after highlighting the research capacity they built through RHAY in their application, and another recently accepting a new position as the County adolescent youth program's HIV coordinator. CAWISA reports that their trainees have received promotions to become senior members of their organizations, including one who became senior project officer in charge of accountability at an NGO and another who was promoted to Associate Professor and Head of Department for the School of Public Health. One has continued their training, as he was recently accepted for a post-doctorate fellowship at Yale University.

For CAWISA, the mentoring junior investigators (doctoral students and postdoctoral fellows) approach is being adopted in their partner universities. In fact, CAWISA was recently invited to expand their efforts to the Gambia. The alliance is now creating short-term, tailored trainings in IS to further introduce the approach to others across West and Central Africa. The last half day of the training is devoted to brainstorming small IS projects with a group of motivated training participants that will seed further efforts. Through their capacity building efforts, AHI(SA)2 reports that the University of KwaZulu Natal has expanded the size of their research group from three to 13, including nurses and clinical trial supervisory personnel, and are beginning to conduct new collaborative pediatric clinical research studies using IS research methods.

Priority setting outcomes

All seven local alliances identified follow-on research stemming from their efforts, specifically successfully receiving over $6,250,000 in additional funding to support predominantly research proposals. Three of these awards were from the US National Institutes of Health. One is an investigator-initiated research grant, entitled “Interactive transition support for adolescents living with HIV comparing virtual and in-person delivery through a stepped-wedge cluster randomized clinical trial in South Africa” (8), that leverages the work of AHI(SA)2 to test mHealth interventions using a hybrid effectiveness- implementation design. In addition, as a result of AHI(SA)2 priority setting, the PIs successfully competed for a five-year, cooperative agreement “Evaluation of Long Acting Injectable and Teen Clubs in adolescents (ATTUNE)” (12). In addition, CAWISA PIs received a training grant to expand the pool of independent investigators in IS in Nigeria that builds off the CAWISA model (13). CAWISA also received funding to develop their IS career development toolkit to support researchers and practitioners in West and Central Africa in applying for implementation science funding. The other UAHISA members successfully applied for a grant from the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care to assess the effectiveness and outcomes of dispensing messages on adherence and viral suppression among children with an unsuppressed viral load in Uganda, a research gap identified by the alliance members. In addition, alliances received funds to pilot research studies conducted by trainees.

Dissemination efforts outcomes

The local alliances report publishing over 60 peer-reviewed journal manuscripts and were part of eight international and local conference presentations/posters as an outcome of their work. This includes a systematic review and DELPHI analysis on interventions addressing the adolescent HIV continuum of care in South Africa (14), a reflection on provider-led adaptations to mobile phone delivery of the Adolescent Transition Package in Kenya (15), and a look at health worker perceptions of stigma towards Zambian adolescent girls and young women (16). Many of these were the result of new collaborations developed by the alliance, including publications with mentees and alliance members as first authors with the local alliance PIs and other steering committee members as mentors. In addition, the alliances also published newsletters and presented at international conferences both with poster and podium presentations. These are outputs above and beyond the conferences or events hosted by the local alliances themselves. While many of these alliance efforts are too new to have demonstrated long-term health impacts, UAHISA reports that their thematic group working on tuberculosis prevention in HIV/AIDS patients has been included in Uganda's guidelines.

Discussion

In fostering sustainable, long-term collaborations among researchers, clinicians, policymakers, implementers, and youth, the local alliances have played a key role in building sustainable and nimble learning platforms. They have contributed to critical increases in IS capacity. Specifically, training allowed the alliances to build IS capacity and orient new members to what for many was a new field. These efforts establish a shared framework and understanding of IS among diverse partners. For the country alliances specifically, as their efforts progressed, they often provided additional training opportunities developed and tailored to the unique needs of their members. In contrast, the two regional alliances were focused almost exclusively on capacity building- investing much of their work in developing and maintaining long-term mentorship programs.

In addition, the learning spaces the alliances create provide unconventional but critical engagement of non-researchers that enhance dissemination, overall capacity, and enable a stronger response to critical challenges. Specifically, non-researchers are invited to not only learn about and provide input on alliance activities, but also lead efforts. While the approaches to engagement are unique to each alliance and its goals, the overarching engagement constructs, including partnership exchange, capacity building, and collaboration, are common across them (17).

This study has several limitations. First, this is a self-evaluation of the activities, themes, and outcomes of the local alliances, which presents a limited perspective and is inherently prone to bias. Second, this is not an exhaustive review of the full range of unique activities of each alliance but is rather intended to highlight key points. Finally, this work is limited to AHISA-supported local alliances focusing on adolescent HIV and does not address other collaboration models.

Additional broader limitations to this manuscript and analysis include an inability to assess how sustainable these alliances will be given how young they are. Future analyses should include metrics to assess sustainability. Moreover, the analysis was not framed around key gaps or challenges in implementation and how the local alliance helped to address these challenges and whether their efforts were successful, which future analyses could also include.

The AHISA local alliances lay the foundation for sustaining IS activities in high-burden HIV countries by anchoring research agendas in locally identified challenges and goals. By engaging policymakers, researchers, HIV practitioners, and youth from the community, the alliances ensure that research priorities and solutions are responsive to local needs. The AHISA local alliances epitomize a collaborative, community-driven learning ecosystem that offers invaluable insights and best practices for informing IS research-to-action endeavors worldwide.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because it is not possible to anonymize the qualitative data from such a small data set that is specific to each country or regional alliance. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Susan Vorkoper,c3VzYW4udm9ya29wZXJAbmloLmdvdg==.

Author contributions

SV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KA: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. DD: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. MM: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. CM: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. NS-A: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. FS: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. BZ: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. RS: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The Duke University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (5P30 AI064518).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their alliance members and partners, who have been instrumental in creating and developing the local IS alliances.

In memoriam

Since the submission of this publication, Dr. Kawango Agot has passed away. On behalf of the Adolescent HIV Implementation Science Alliance, we wanted to acknowledge her as a tireless mentor and advocate for youth. The impact of her work will be felt for years to come.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US Department of Health and Human Services and the National Institutes of Health.

References

1. Fogarty International Center. Implementation Science News, Resources and Funding for Global Health Research. Fogarty International Center (2023). Available online at: https://www.fic.nih.gov/ResearchTopics/Pages/ImplementationScience.aspx (Accessed May 14, 2024).

2. Sturke R, Vorkoper S, Bekker LG, Ameyan W, Luo C, Allison S, et al. Fostering successful and sustainable collaborations to advance implementation science: the adolescent HIV prevention and treatment implementation science alliance. J Int AIDS Soc. (2020) 23(Suppl 5):e25572. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25572

3. Fogarty Internatiomnal Center. Adolescent HIV Prevention and Treatment Implementation Science Alliance. Fogarty International Center (2024). Available online at: https://www.fic.nih.gov/About/center-global-health-studies/Pages/adolescent-hiv-prevention-treatment-implementation-science-alliance.aspx (Accessed May 14, 2024).

4. Healthy Sunrise Foundation. Nigerian Implementation Science Alliance. Health Sunrise Foundation (2023). Available online at: https://nisaresearch.org/ (Accessed May 14, 2024).

5. Sturke R, Siberry G, Mofenson L, Watts DH, McIntyre JA, Brouwers P, et al. Creating sustainable collaborations for implementation science: the case of the NIH-PEPFAR PMTCT implementation science alliance. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2016) 72(Suppl 2):S102–107. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000001065

6. Ezeanolue EE, Powell BJ, Patel D, Olutola A, Obiefune M, Dakum P, et al. Identifying and prioritizing implementation barriers, gaps, and strategies through the Nigeria implementation science alliance: getting to zero in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2016) 72(Suppl 2):S161–166. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000001066

7. Kinuthia J, Farquhar C. Improving the HIV Care Cascade in Kenya through Implementation Science Training (D43TW009580) (2018).

8. Zanoni B, Archary M. Interactive Transition Support for Adolescents Living with HIV Comparing Virtual and In-person delivery through a stepped-wedge cluster randomized clinical trial in South Africa (R01MH131434) (2022).

9. Kipkurui N, Owidi E, Ayieko J, Owuor G, Mugenya I, Agot K, et al. Navigating antiretroviral adherence in boarding secondary schools in Nairobi, Kenya: a qualitative study of adolescents living with HIV, their caregivers and school nurses. PLOS Glob Public Health. (2023) 3(9):e0002418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002418

10. Chow DWS, Goi A, Salm MF, Kupewa J, Mollel G, Mninda Y, et al. Through the looking glass: empowering youth community advisory boards in Tanzania as a sustainable youth engagement model to inform policy and practice. Front Public Health. (2024) 12:1348242. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1348242

11. Stockwell MS, Kitaka SB. SEARCH: SMS Electronic Adolescent Reminders for Completion of HPV Vaccination- Uganda (R21CA253604) (2020).

12. Archary M, Zanoni B. Evaluation of Long Acting Injectable (LAI) and Teen Clubs in adolescents (ATTUNE) (UG1MD019435) (2023).

13. Abimiku AL, Sam-Agudu N. Expanding the pool of Independent Investigators in Implementation Science in Nigeria through HIV research training (EXPAND) (D43TW012280) (2022).

14. Zanoni B, Archary M, Sibaya T, Ramos T, Donenberg G, Shahmanesh M, et al. Interventions addressing the adolescent HIV continuum of care in South Africa: a systematic review and modified delphi analysis. BMJ Open. (2022) 12(4):e057797. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057797

15. Mangale DI, Onyango A, Mugo C, Mburu C, Chhun N, Wamalwa D, et al. Characterizing provider-led adaptations to mobile phone delivery of the adolescent transition package (ATP) in Kenya using the framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based implementation strategies (FRAME-IS): a mixed methods approach. Implement Sci Commun. (2023) 4(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s43058-023-00446-y

16. Meek C, Mulenga DM, Edwards P, Inambwae S, Chelwa N, Mbizvo MT, et al. Health worker perceptions of stigma towards Zambian adolescent girls and young women: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. (2022) 22(1):1253. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08636-5

17. Pinto RM, Park SE, Miles R, Ong PN. Community engagement in dissemination and implementation models: a narrative review. Implement Res Pract. (2021) 2:2633489520985305. doi: 10.1177/2633489520985305

APPENDIX 1

Codebook for portfolio analysis of local implementation science alliances

Goal: to understand the unique and common approaches across the AHISA local alliances; to assess their approaches to building a local alliance, promoting IS, and engaging partners; and to note changes in the alliances over time,

Background

1. Alliance Name

2. Yrs

a. 2019

b. 2020

c. 2021

d. 2022

e. 2023

3. Types of documents included

a. Applications

b. Final reports

c. Other

Justification

4. Goals/objectives (already have this)

5. Why they wanted to do this

Activities

6. Capacity building (open text)

a. Activity: approach, objectives, target audience, presenters, etc.

b. Outcomes

7. Convenings (open text)

a. Activity: approach, objectives, how often, etc.

b. Outcomes:

8. Other Activities and Outcomes (open text)

Role of is

9. How IS was incorporated (open text)

a. How activities supported or promoted IS

b. Use of any TMF, outcomes, etc.

10. Where along the research continuum (open text)- development to dissemination

Engagement

11. Partners

a. List of partners

i. Youth (10–30 y.o.)

ii. Family members

iii. Clinicians/direct service providers

iv. Policymakers federal

v. Policymaker local

vi. Program implementers

vii. General Public

viii. Funder

ix. Other, please specify

b. How/why they were selected (open text)

12. Engagement practices

a. Engagement methods/strategies/activities (open text)

b. Type of engagement- Pinto constructs

i. Communication

ii. Partnership exchange

iii. Community capacity-building

iv. Leadership

v. Collaboration

c. Timing of engagement (Asuquo, 2021)

i. Pre-intervention phase referred to planning and readiness activities, including stakeholder advisory mechanisms, protocol development, ethical approval, field testing and related formative research activities.

ii. Intervention phase referred to activities during the actual implementation of the HIV prevention intervention studies.

iii. Post-intervention phase referred to dissemination, results reporting and related activities.

Changes over time

13. Note any shifts between applications (open text)

14. Note any shifts between application and final report (open text)

15. Sustainability efforts (open text)

Keywords: implementation science, capacity building, adolescent HIV, Africa, collaboration, alliance

Citation: Vorkoper S, Agot K, Dow DE, Mbizvo M, Mugo C, Sam-Agudu NA, Semitala FC, Zanoni BC and Sturke R (2024) Building locally anchored implementation science capacity: the case of the adolescent HIV implementation science alliance-supported local iS alliances. Front. Health Serv. 4:1439957. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2024.1439957

Received: 28 May 2024; Accepted: 23 September 2024;

Published: 14 October 2024.

Edited by:

Mithun Rudrapal, Vignan’s Foundation for Science, Technology and Research, IndiaReviewed by:

Samiksha Garse, DY Patil Deemed to be University, IndiaSridhar Vemulapalli, University of Nebraska Medical Center, United States

Copyright: © 2024 Vorkoper, Agot, Dow, Mbizvo, Mugo, Sam-Agudu, Semitala, Zanoni and Sturke. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Susan Vorkoper, U3VzYW4udm9ya29wZXJAbmloLmdvdg==

†Deceased

Susan Vorkoper

Susan Vorkoper Kawango Agot2,†

Kawango Agot2,† Dorothy E. Dow

Dorothy E. Dow Cyrus Mugo

Cyrus Mugo Nadia A. Sam-Agudu

Nadia A. Sam-Agudu Rachel Sturke

Rachel Sturke