- 1Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence and Impact (HEI), McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 2Waypoint Research Institute, Waypoint Centre for Mental Health Care, Penetanguishene, ON, Canada

- 3DeGroote School of Business, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

Introduction: The implementation of evidence-informed policies and practices across systems is a complex, multifaceted endeavor, often requiring the mobilization of multiple organizations from a range of contexts. In order to facilitate this process, policy makers, innovation developers and service deliverers are increasingly calling upon intermediaries to support implementation, yet relatively little is known about precisely how they contribute to implementation. This study examines the role of intermediaries supporting the implementation of evidence-informed policies and practices in the mental health and addictions systems of New Zealand, Ontario, Canada and Sweden.

Methods: Using a comparative case study methodology and taking an integrated knowledge translation approach, we drew from established explanatory frameworks and implementation theory to address three questions: (1) Why were the intermediaries established? (2) How are intermediaries structured and what strategies do they use in systems to support the implementation of policy directions? and (3) What explains the lack of use of particular strategies? Data collection included three site visits, 49 key informant interviews and document analysis.

Results: In each jurisdiction, a unique set of problems (e.g., negative events involving people with mental illness), policies (e.g., feedback on effectiveness of existing policies) and political events (e.g., changes in government) were coupled by a policy entrepreneur to bring intermediaries onto the decision agenda. While intermediaries varied greatly in their structure and characteristics, both the strategies they used and the strategies they didn't use were surprisingly similar. Specifically it was notable that none of the intermediaries used strategies that directly targeted the public, nor used audit and feedback. This emerged as the principle policy puzzle. Our analysis identified five reasons for these strategies not being employed: (1) their need to build/maintain healthy relationships with policy actors; (2) their need to build/maintain healthy relationships with service delivery system actors; (3) role differentiation with other system actors; (4) perceived lack of “fit” with the role of policy intermediaries; and (5) resource limitations that preclude intensive distributed (program-level) work.

Conclusion: Policy makers and implementers must consider capacity to support implementation, and our study identifies how intermediaries can be developed and harnessed to support the implementation process.

Introduction

The implementation of evidence-informed policies and practices (EIPPs) at scale across whole systems is a complex, multifaceted endeavor. Yet an effective implementation process is critical in bridging the gap between the promise of EIPPs and positive outcomes for citizens and society. This is particularly true when the EIPP is psycho-social in nature requiring the mobilization of multiple organizations, often multiple roles within organizations, a need to respond to the diversity of individuals or families receiving the EIPP, and a need to take into account a range of contexts. It is this complexity that may account for the continued lack of access to psycho-social EIPPs for both adults and children. For example, in the US, researchers found that the overall penetration rates for six behavioural evidence-based treatments was only 1%–3% and adoption rates were static or declining across the states who had invested in them (1). This is despite an increased understanding of the burden of mental illness and addictions (2) and increased momentum by policy makers around the globe to address the issue (3).

In response to these challenges, policy makers, innovation developers and service deliverers are increasingly looking toward organizations or programs that can facilitate the implementation process. These organizations are often referred to as intermediaries. Intermediaries act as “translators” for EIPPs and provide technical assistance to organizations and providers that deliver services for citizens, while informing policy and systems (4–7). In general, intermediaries fall under the broader implementation construct of facilitation (8, 9) or change agency (10) with the recognition that complex change processes, such as implementing a new EIPP, do not on their own reach a high enough rate of penetration and fidelity in systems to produce their intended benefits. In order for this to happen, external supports are typically required and intermediaries are one way through which facilitation can take place.

Limited research exists on this type of intermediary and there is not yet a consensus on what precisely defines them and how they contribute to implementation. One reason for this is that the scholarship that exists comes from different fields (e.g., public management, social sciences or implementation science), which naturally draw from different theories, methods and ways of reporting. Added to this is a great deal of heterogeneity in terms of topics such as: child, youth and family services (5, 11), education (12, 13), environment (14), mental health and addictions (15, 16), occupational health and safety (17) and technology (18), where the contexts surrounding the intermediaries vary, limiting the comparability across them. Finally, there are a diversity of terms in use, with some of the more common including: intermediary (organization), purveyor, technical assistance center, knowledge brokering organization, centre of excellence, implementation team and backbone organization (19–26). This lack of precision means that different terms may be used to describe similar constructs and the same term may also be used to describe two quite different constructs, leading to further conceptual fuzziness.

The strategies employed by intermediaries vary but the existing literature does point to some common strategies and approaches. A survey of 68 intermediaries found support for seven core functions of intermediaries, including: consultation activities; best practice model development; purveyor of evidence-based practices; quality assurance and continuous quality improvement; outcome evaluation; training, public awareness and education; and policy and systems development (27). More recently, a web scan and survey of child behavioral health intermediaries found that they used an average of 32 distinct strategies to implement evidence-based interventions, with common strategies including educational, planning and quality improvement strategies (15). They found little consensus, however, on which strategies intermediaries perceived as the most effective.

Some authors frame the strategies of intermediaries in different terms. For example, they describe the approaches of intermediaries and other “support system infrastructure” as including both general capacity-building approaches as well as those that are innovation-specific (28), while others identify strategies targeting different levels in the system (e.g., federal, province/state, local) (7). Still others have described intermediaries in economic terms, suggesting intermediaries can address research supply-side issues (supporting the production, translation and consumption of research) as well as the demand-side issues (such as improving service delivery readiness for a particular EIPP, support for implementation, etc.) (13). To our knowledge, the literature has not distinguished intermediaries based on their public vs. private sector placement.

We identified three sub-types of intermediaries in the literature that specifically address the knowledge production-to-implementation continuum: (1) those whose focus is mainly on translation and dissemination of research evidence to inform policy and practice (knowledge translation-focused, or “KT intermediaries”) (11, 12, 14, 29, 30); (2) those whose focus is mainly on the implementation of pre-packaged research evidence to service providers in the form of evidence-based practices (practice-focused, or “practice intermediaries”) (15, 16, 31); and (3) those whose focus is mainly on assisting policy makers or other system leaders in getting EIPPs embedded at scale in systems (policy-focused, or “policy intermediaries”) (13, 32–34). Of course, many intermediaries will engage in activities across all three types, but this characterization may help to clarify the starting point, goals and theories of change related to each.

Given the focus here on policy and supporting implementation at scale in mental health and addictions systems, our study targets the policy intermediary sub-type. We adopted a definition that we first forwarded by Bullock & Lavis (2019): Intermediaries are organizations or programs that have an explicit and recognized role to support the implementation of government mental health and addictions policy goals and employ specific methods of implementation support. In order to achieve these goals, other actors in the system must understand and accept this role, including those in government, service delivering organizations and other stakeholders.

This study examines the role of policy intermediaries supporting the implementation of evidence-informed policies and practices in the mental health and addictions systems of high-income countries. Guided by implementation theory and drawing from established explanatory frameworks, we address three questions: (1) Why were the intermediaries established? (2) How are intermediaries structured and what strategies do they use in systems to support the implementation of policy directions? and (3) What explains their lack of use of particular strategies?

Methods

Integrated KT approach

This study was designed and conducted in collaboration with the International Initiative for Mental Health Leadership (IIMHL)—an international collaborative that focuses on improving mental health and addictions services in eight countries: Australia, Canada, England, Ireland, New Zealand, Scotland, Sweden, and USA (a ninth country, the Netherlands, joined after data collection began). Prior to initiating the study, one of the authors (HB) had been participating with a sub-group of individuals from IIMHL countries who were either working in intermediaries or interested in harnessing the capacity of intermediaries to support systems change. With those relationships in mind, we asked the IIMHL if they would like to partner on this research in an integrated knowledge translation capacity. Integrated knowledge translation (IKT) is an approach to research where those who produce research and those who may use it, partner on a study with the goal on enhancing relevance and facilitating use (35). In this case, our IIMHL partners have thus far participated in three study phases: (1) providing input into the conceptualization and planning of the study, (2) assisting with recruitment and data collection by offering to host the research team during site visits and identifying potential key informants to be interviewed, and (3) assisting with the interpretation of findings and identifying next steps.

Study design

We used the holistic multiple case study approach outlined by Yin (36). A multiple case study approach is often considered more compelling and robust than single case designs because of the replicative nature and the ability to make predictions from theory that can be tested across cases leading to higher explanatory power. It is a suitable methodology for our questions as it allows for an examination of intermediaries in their context. We brought a realist-postpositivist philosophical approach to this research, considering it a form of empirical inquiry and focusing on maintaining objectivity through the use of techniques like triangulation to minimize errors and get as close as possible to the “truth” (37).

Ethics approval for this study was granted by McMaster University through the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board and informed consent was sought and provided by all participants. The study was conducted in two phases: (1) case selection, and (2) comparative case study. For brevity, we refer to mental health and addictions as “mental health”.

Phase 1—case selection

Qualitative description was selected as the analytic approach for this phase, which has, as its goal, a comprehensive summary of events in everyday terms (38). The “case” or unit of analysis in this study is defined as: a political jurisdiction with a governing authority that has the ability to develop, implement and evaluate mental health policy and the organizations or programs within them that support policy implementation. This definition means the units may be at different policy levels in systems (e.g., national, provincial/state or municipal). The “population” of potential jurisdictions included countries that are members of the IIMHL. These countries all have well-established health systems and their participation in the IIMHL reflects a commitment to mental health systems improvement and advancement. They provide adequate variation in terms of health service structures, including how mental health services are designed, managed and delivered. They also vary in the factors that may impact successful implementation but have enough similarity to ensure the case study is sensitive to the variables of interest.

The research team worked with IIMHL partners to generate a purposive sample of potential interviewees from each jurisdiction. The list included a mix of leaders in government, agencies of government, non-governmental organizations and service providers who played a leadership role in implementation and could speak to the macro-context of their mental health system. From this list, the research team (HB) contacted one or two leaders from each jurisdiction requesting a brief semi-structured phone interview by telephone or Skype. The questions were targeted toward understanding the policy priorities currently being implemented and the structures in place supporting their implementation. A number of potential interviewees were known to HB through their mutual involvement in the IIMHL.

Interviews were recorded and reviewed by the study team. Using qualitative content analysis and following the qualitative description approach, analysis remained “close” to the data with minimal interpretation. Structured summary sheets of each interview outlining important characteristics and infrastructure were generated and a table was created to facilitate case selection.

Phase 2—comparative case study

Cases for the comparative case study were purposively sampled based on findings from Phase 1 using an approach that approximates the Most Different Systems design or Mill's Method of Similarity (39). Using this method, cases are selected based on a similar outcome or dependent variable but are diverse in other ways. In this study, cases were selected based on the presence of at least one organization or program that has an explicit role supporting mental health policy implementation (policy intermediary). Cases were also sampled for diversity in other domains such as the policy level (state/province vs. national); mental health system factors (e.g., a range of governance, financial and service delivery arrangements); and, political system characteristics (e.g., diversity in the institutional arrangements, interests and ideas at play) (Table 1). Using this approach, the cases selected include: New Zealand, the province of Ontario in Canada, and Sweden. Ontario included three embedded cases. The cases are bounded in two ways. First, by the political areas specified above that have policy authority over mental health and addictions. Second, they are bounded temporally, that is, this research only considers active implementation efforts and the current structures in place to support them and does not look explicitly at past policy efforts.

The methods used for this phase included an analysis of key documents, site visits and follow-up interviews. Field notes were also recorded throughout the site visit by the study team.

Review of key documents

We analyzed key documents collected as part of case selection and additional documents retrieved through web searches of government and stakeholder websites and a search of PubMed, Google Scholar and LexisNexis in October 2016 and again in June 2018 for relevant research articles and media accounts related to the intermediaries or implementation efforts. The types of documents analyzed include: annual reports, government reports, news articles, KT products produced by intermediaries and peer reviewed research. Documents were reviewed and data were extracted based on the following domains: health system and political system characteristics; intermediaries and other structures supporting implementation of mental health and addictions priorities; and implementation strategies being utilized.

We reviewed and analyzed a total of 73 sources: 24 policy documents, 13 reports or other documents generated by or on behalf of the intermediary, 22 websites and 14 scholarly publications. We also reviewed some grey literature on implementation infrastructure that referenced at least one of the cases (n = 3) and used news media articles as a source of triangulation to verify events that were mentioned by stakeholders during the interview (Appendix 1). We used each intermediary's website to review reports and publications, so many of those are not counted in the tally above.

Site visits

Our team created a matrix outlining the types of stakeholders we wanted to interview and shared it with the IIMHL IKT partners in each jurisdiction. Partners were instructed to identify at least two individuals for each category and provide contact details. Types of stakeholders included: (1) intermediary, (2) policy makers/government, (3) funder(s) of implementation/intermediary, (4) oversight of implementation/intermediary, (5) researchers familiar with the intermediary, (6) knowledge synthesizers & translators, (7) recipients of implementation supports, (8) partners of intermediary, and (9) others. One to two people from each category were then invited to participate. The consent form was translated into Swedish for the Swedish case, and while the interviews were conducted in English, an informal English/Swedish interpreter (someone who was familiar with the subject) was offered to potential participants.

Interview questions were tailored to the type of stakeholder but were focused on constructing a full picture of how policy implementation is structured and delivered in the system, including: (1) what policy priorities are currently being implemented; (2) who (organizations and individuals) are supporting their implementation; (3) what implementation strategies they use (e.g., training, audit and feedback, etc); (4) how the implementation supports are valued and meeting the identified goals; and (5) what factors were important in the creation of the intermediary (Appendix 1). The interview guide was revised as the analysis of earlier rounds of data proceeded and theoretically or substantively important insights were identified for exploration in later rounds. With consent, interviews were recorded for later transcription and lasted approximately 90 min each. Interviews were conducted until saturation was reached and no key perspectives were deemed missing. Throughout the site visit, the study team took field notes including descriptive (e.g., who, what, where, etc.) and interpretive information (e.g., personal reflections and questions arising from activities). Additional documents, such as presentations or reports, were requested from participants and reviewed. All site visits took place in 2017: New Zealand (February), Sweden (May) and Ontario (July–September). When appropriate based on the rules of the jurisdiction, ethics waivers were sought and acquired prior to the site visit.

Follow-up interviews

A final stage of data collection included interviews with key informants who were unable to participate during the site visits or agreed to a follow-up interview as analysis proceeded. These additional interviews took place in 2017 and 2018. This was done to ensure each case was as complete and as comparable as possible across jurisdictions.

A total of 49 initial interviews were conducted during the site visits or shortly thereafter (13 NZ, 23 ON, 13 SE). More interviews were conducted in Ontario because the three embedded cases meant that a larger sample of stakeholders were required to reach saturation. Three of the interviews in Sweden were supported by an interpreter. Stakeholders from all of the categories identified in the stakeholder matrix were interviewed for each case, providing us with a well-rounded perspective. Four follow-up interviews were also conducted to confirm details or fill small gaps in the analysis.

NVivo12 Qualitative Software was used to manage data, thereby serving to establish a comprehensive and easily accessible case study database.

Analysis

Transcripts and/or audio recordings were reviewed at least twice. Supporting documents were also reviewed and coded. Directed content analysis (40) was employed, which begins the coding process by drawing from existing research and theory as a guide. Within each case, sources were compared with one another to identify themes that emerge across them. The lead researcher (HB) led all stages of the analysis and JNL, GM and MW were involved in reviewing codes, themes and interpretation.

Analytic goals and frameworks

Goal 1

To explain why the intermediaries were originally established and endorsed by governments to support policy implementation, we used Kingdon's multiple streams agenda-setting framework (41). Kingdon's theory identifies activities in independent “streams” that have to come together during a brief “window of opportunity”. These include: heightened attention to a problem (problem stream), an available and feasible solution (policy stream), and the motive to select it (politics stream). The three streams must come together in order for a change to be made, and this usually happens through the work of a policy entrepreneur.

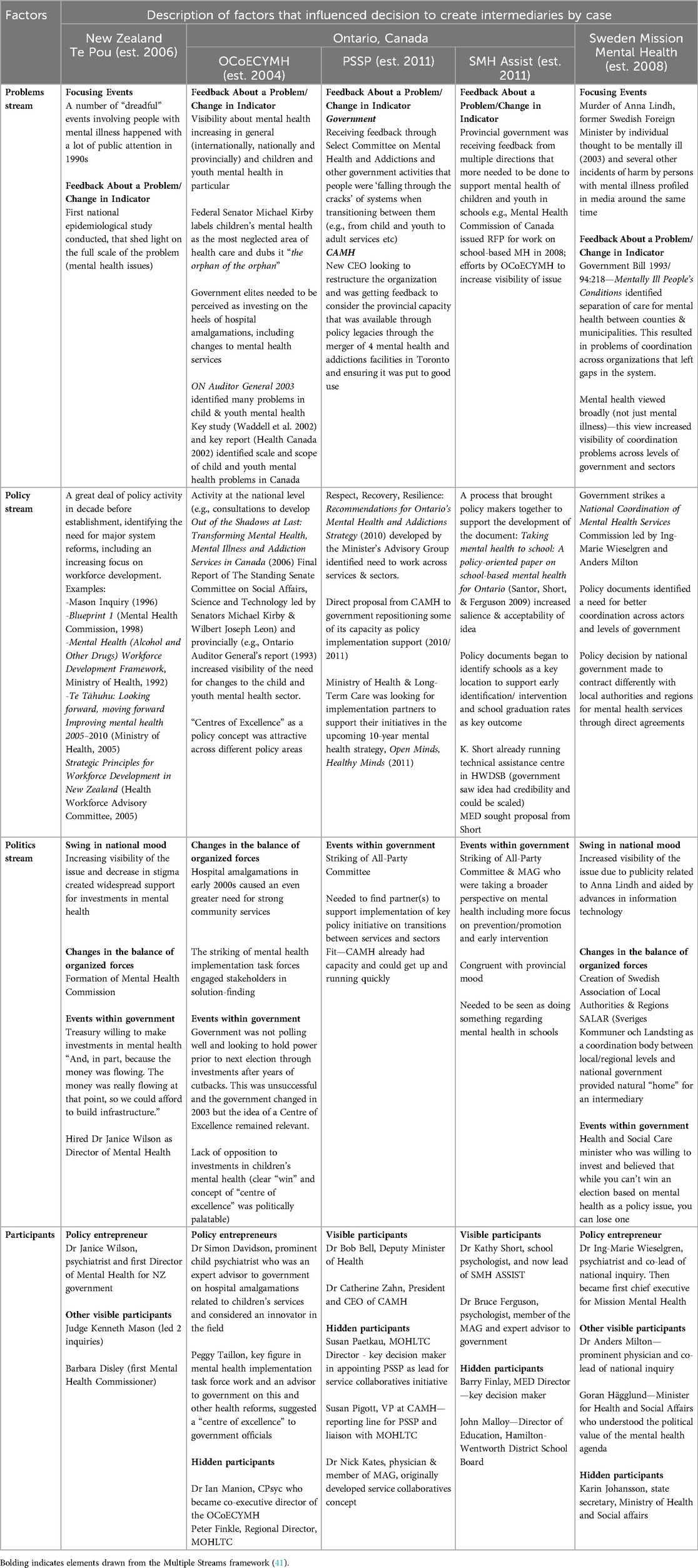

Using this framework, we identified the timelines of the relevant events and activities leading up to the establishment of the intermediary(ies) based on stakeholder accounts of what was relevant as well as our document review. Next, we developed a comparative table that highlighted: (1) aspects of the problems in each system that each intermediary was created to address, (2) policy proposals and ideas that were supportive of the need for implementation infrastructure in the form of an intermediary, (3) the political environment that made the intermediary(ies) as a policy solution feasible, and (4) the relevant actors, including policy entrepreneurs that were important for bringing the intermediary to the decision agenda.

Goal 2

To describe and compare the structures of the intermediaries, their organizational characteristics and the implementation strategies they use, we drew on a modified version of the Interactive Systems Framework for Dissemination and Implementation (ISF) as a descriptive framework. The ISF was originally developed by Wanderman and colleagues (28, 42) and is a heuristic that captures how new knowledge moves from research development to widespread use and the systems and processes supporting this movement. The ISF specifies the three systems needed to carry out dissemination and implementation functions: (i) Synthesis and Translation System; (ii) Delivery System; and (iii) Support System. In an effort to capture the important role of policy in implementation, we modified the ISF by adding a Policy System (links with the three other Systems and provides a variety of policy-related supports for dissemination and implementation) (Bullock. 2019).

We used the modified ISF to sort and classify the strategies used by intermediaries according to the “target” System. We then added some categories that we felt were important to highlight and did not necessarily fit well within one particular System: strategies targeting the public; strategies targeting individuals with lived experience & family members; and strategies focused on performance assessment and/or system-monitoring. Finally, we cross-referenced our strategies with the implementation strategies identified by Powell and colleagues (43) who used the sub-categories of “Plan”, “Educate”, “Finance”, “Re-structure” “Quality Management” and “Attend to Policy Context”. Next, we extracted examples of the strategies for each case from the interview data, and cross-referenced/supplemented these with the document and website data sources.

Goal 3

To explain the choice of implementation strategies we first drew on the 3I + E framework (44, 45). The 3I + E framework is used to explain how Institutions (e.g., government decision-making structures and processes), Interests (i.e., groups with a vested interest), Ideas (i.e., values and research-based knowledge) and External factors (i.e., events outside of the policy area of interest) affect the actions of those making decisions or implementing them.

Our original intent was to use this framework for a complete analysis, however, once we had results from the second question, we found we had a far more interesting policy puzzle related to the lack of use of particular strategies that warranted a slightly different analytic approach including a thematic analysis of salient features that fell under two elements of the 3I + E framework.

Context: intermediary case descriptions

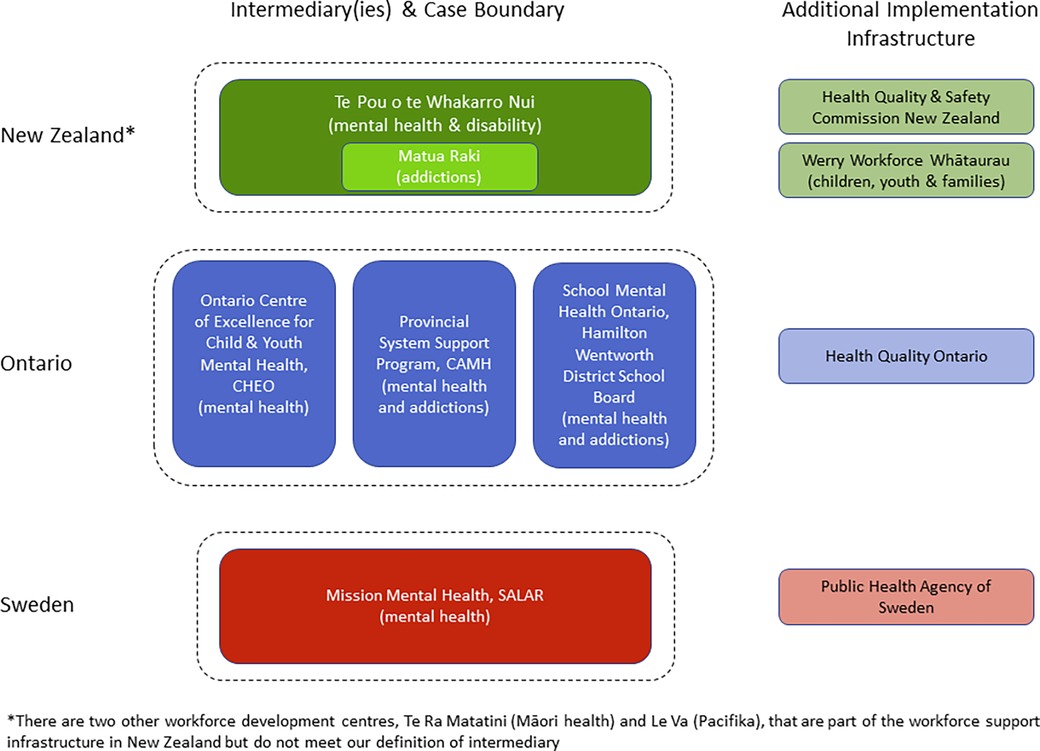

Figure 1 depicts the intermediary infrastructure in each case as well as the case boundaries.

New Zealand

The Ministry of Health, through Workforce New Zealand, funds a national infrastructure to support development of the mental health and addictions workforce, including 5 centres with different foci. Over time, Te Pou o te Whakaaru Nui (Te Pou, adult mental health and disability focus) and Matua Raki (addictions focus, housed at Te Pou), have developed into an intermediary that aligns with our definition and is the focus of the NZ case. Two other organizations that are increasingly contributing to the implementation infrastructure include the Werry Workforce Whāraurau (child and youth focus) and the Health Quality & Safety Commission New Zealand.

Ontario, Canada

In Ontario, we identified three intermediaries that fit our definition: (1) Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health (OCoECYMH) located at the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario and funded by the Ministry of Children and Youth Services (note: post-data collection, funding authority was transferred to the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, MOHLTC); (2) Provincial System Support Program (PSSP) located at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and funded by MOHLTC; and (3) School Mental Health ASSIST (SMH ASSIST) located at the Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board and funded by the Ministry of Education. These three intermediaries collectively comprise the Ontario case, however, other organizations, such as Health Quality Ontario, were also highlighted as increasingly playing an intermediary function in mental health.

Sweden

Uppdrag Psykisk Hälsa (Mission Mental Health) is the intermediary in Sweden that met our definition and is the focus of this case. Mission Mental Health is located at the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR), which is a peak body that acts as both an employers’ organization as well as one that represents the interest of the municipalities and regions to the national government. Mission Mental Health is funded through an agreement between SALAR and the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. The Public Health Agency of Sweden was also highlighted as an organization beginning to take on more of an intermediary function.

It should be noted that the lead researcher (HB) previously worked with PSSP and has pre-existing relationships with all three intermediaries in Ontario.

Results

Why were the intermediaries established?

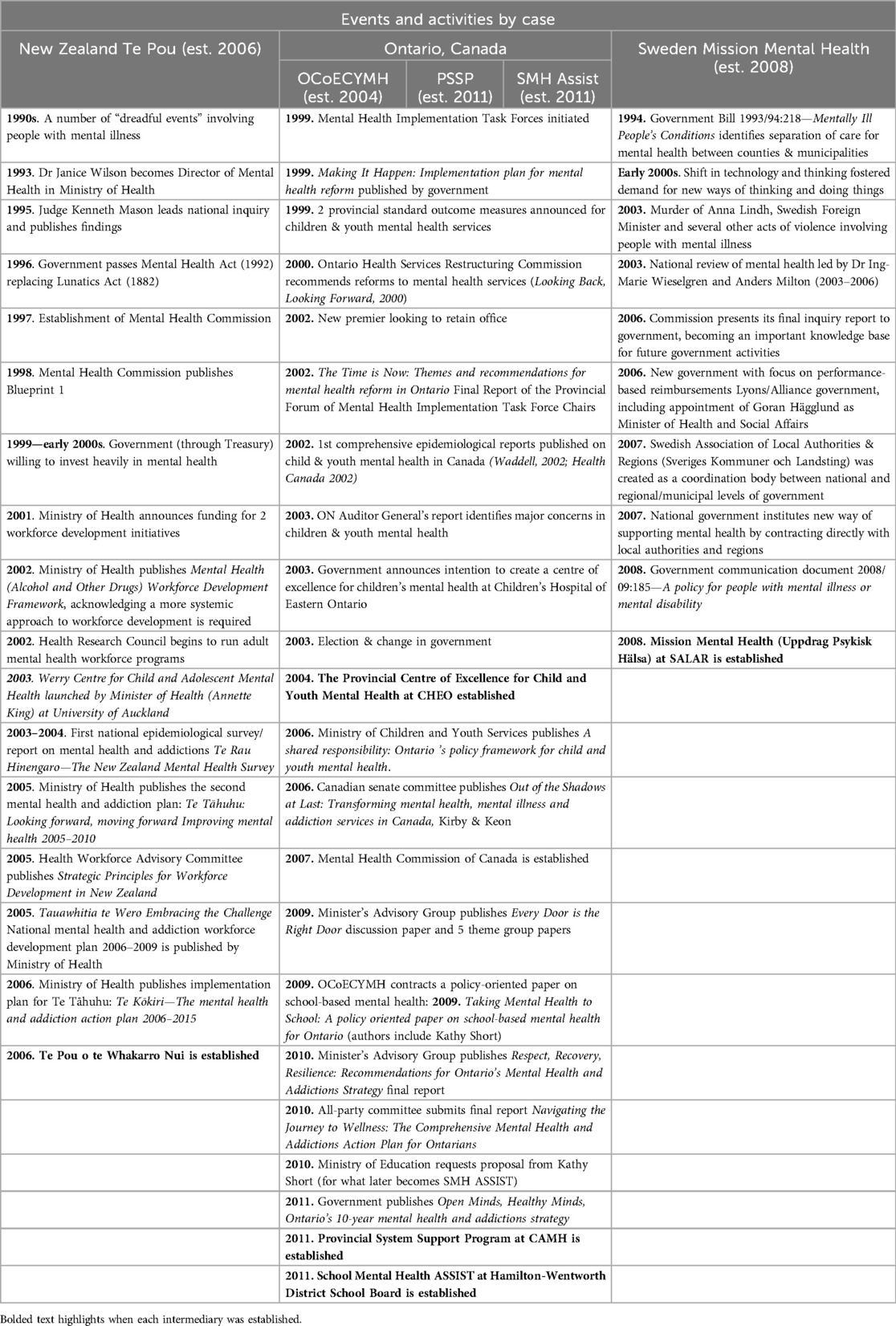

Table 2 identifies the timelines of the relevant events and activities leading up to the establishment of the intermediary(ies) based on stakeholder accounts and our document review. The results of the analysis of factors influencing the decision to establish the intermediaries is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Factors that influenced the decision to create intermediaries, drawing from the Multiple Streams framework (41).

In all three cases, the intermediary infrastructure came on the heels of a monumental shift in how mental health and addictions care was delivered—moving from a system of institutional-based care to one based largely in community. While the timelines and trajectories for deinstitutionalization varied across cases (46–51) the process was completed around the turn of the century—and it is in the decade that followed that these intermediaries were established.

The deinstitutionalization process left policies legacies that differed in each case due to the unique political terrain and health policy features of each jurisdiction. However, this shift in the model of care was largely cited by key informants as a factor that was influential in driving the need for new and different capacities in the system as a result of it becoming more complex and multi-faceted and spanning a new array of community and hospital environments. The type of new capacity required was framed differently across cases and is outlined as part of the analysis below.

New Zealand

During the years following deinstitutionalization, mental health became a much more visible policy issue due to several “dreadful events” involving people with mental illness and feedback about the scale and scope of the issue from the first national epidemiological study on mental health issues (problem stream). This increased visibility of the problem led to a flurry of a policy activity, including a government inquiry, at least seven policy documents and a major change in the law (policy stream). Also during this time was the formation of a Mental Health Commission and a government that was willing to invest heavily in mental health (politics stream). Over time, some of the challenges identified in the system were framed as a need to expand the workforce to include other roles that were not required in an institutionally-based care model and to simultaneously equip the existing workforce to function differently than they had been expected to in the past.

The policy entrepreneur (Janice Wilson) was recognized by almost all key informants as playing a pivotal role in getting the workforce infrastructure established. However, workforce centres in and of themselves, did not meet our definition of an intermediary. Since their establishment, TePou, Matua Raki and more recently, the Werry Centre, have evolved into the role of an intermediary. This broader role may have been bolstered by the government's decision in 2012 to eliminate the New Zealand Mental Health Commission and transfer only limited functions to the Office of the Health and Disability Commissioner, leaving additional gaps in the system now filled by these intermediaries.

Ontario, Canada

In Ontario, the first intermediary to be established was the Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child & Youth Mental Health (OCoECYMH)—almost seven years before the Provincial System Support Program (PSSP) and School Mental Health Assist (SMH ASSIST). Prior to OCoECYMH's creation, there was an increasing visibility of children and youth mental health as an issue that needed to be addressed at the national and provincial levels. For example, a Federal Senator, Michael Kirby, called children's mental health the “orphan of the orphan of health care”. In addition, feedback about the problem in the form of research identifying the true scope of the problem in Canada was developed (problem stream). On the political front, the sitting provincial government was not doing well in the polls and was seeking to gain some positive political momentum in an election year by announcing some investments after several years of cuts (politics stream). Children and youth mental health was identified by the provincial auditor general as an area in need of transformation and after a recent round of hospital amalgamations, mental health interest groups were seeking investment to bolster the community sector. From a policy perspective, certain government insiders had been advancing the concept of “centres of excellence” to address a wide variety of policy areas and a new ministry, Ministry of Child and Youth Services had just been created in 2003 (policy stream). The government then reached out to Simon Davidson and colleagues, inviting them to develop a proposal for a centre of excellence for children and youth mental health. Our analysis suggests that two people, Dr Davidson, a prominent child psychiatrist who had developed close relationships with government officials by participating in the hospital amalgamation decisions, and Peggy Taillon, who was an Advisor to the Premier at the time and was very involved in Ontario's Mental Health Implementation Task Force, acted as policy entrepreneurs.

Interestingly, OCoECYMH is also the sub-case that fits most clearly with the Kingdon framework. It is possible that once one intermediary is established in a system for a particular policy area, the concept of additional intermediary capacity is easier for policy makers to buy into based on the policy legacy established by the first. This may mean that the decisions to create PSSP and SMH ASSIST were less “visible” and political in nature and became more “technical” and bureaucratic. In the case of both PSSP and SMH ASSIST, their function was first proposed by those outside of government (CAMH for PSSP and Kathy Short and the OCoECYMH for SMH ASSIST) as a policy solution that could support the implementation of key policy decisions. These policy “solutions” were proposed at a time when the government was developing a new 10-year strategy for mental health and addictions. Bureaucrats in MOHLTC and MEd took advantage of these policy ideas as part of their ministerial commitment and actions related to the new strategy. In general, our analysis suggests for these later intermediaries, most of the activity leading to the decision was in the policies stream (the government was developing a new policy and needed resources that could be mobilized quickly and with a good likelihood of success) and that the decision to invest in this implementation infrastructure was facilitated by the policy legacy created by the establishment of the first.

Sweden

Prior to the establishment of Mission Mental Health, the mental health system in Sweden was in some turmoil due to a highly visible death of a politician by someone with a mental illness as well as some other negative events that were profiled in the media (problem stream). These events increased the visibility of mental health as a policy issue and the government at the time was receptive to further investments in the sector (politics stream). One of the outcomes of this was a national inquiry led by Anders Milton, a prominent politician and Ing-Marie Wieselgren,a prominent psychiatrist and who became the content lead for the inquiry. The inquiry made many recommendations including a need to focus on children and youth, which was seen as a large gap (policy stream). Dr. Wieselgren also acted as the policy entrepreneur, coupling the streams, and once the inquiry work was completed, she became the leader of Mission Mental Health.

Sweden is a good example of how the influence of the policy entrepreneur can continue beyond the decision to establish the intermediary itself. In this case, Dr. Wieselgren was intimately aware of the policy issues based on her work on the national inquiry as well as through her previous roles. She had also established a wide array of relationships with different actors across Sweden. This likely enabled the establishment of Mission Mental Health by increasing its acceptability and ensuring that its work aligned with the policy issues that surfaced during the inquiry.

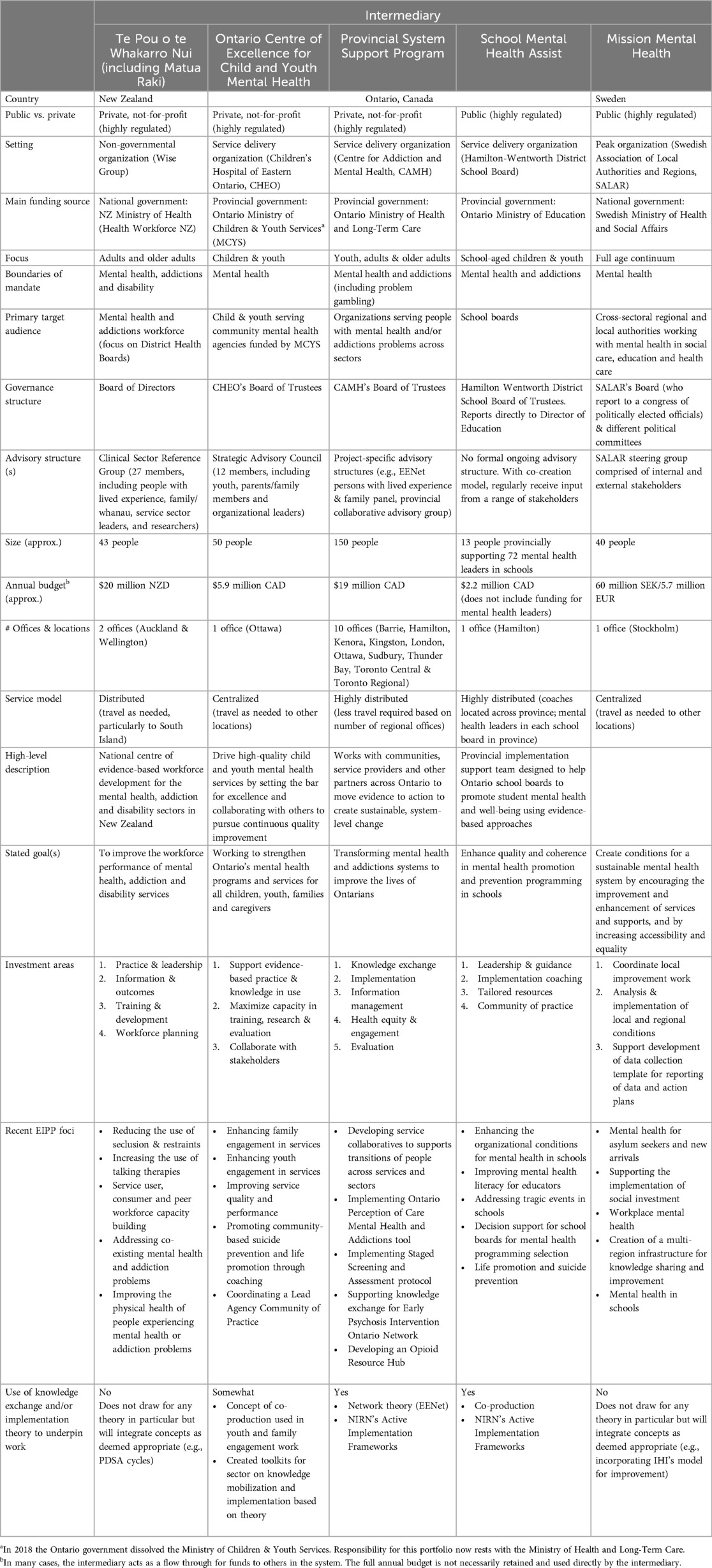

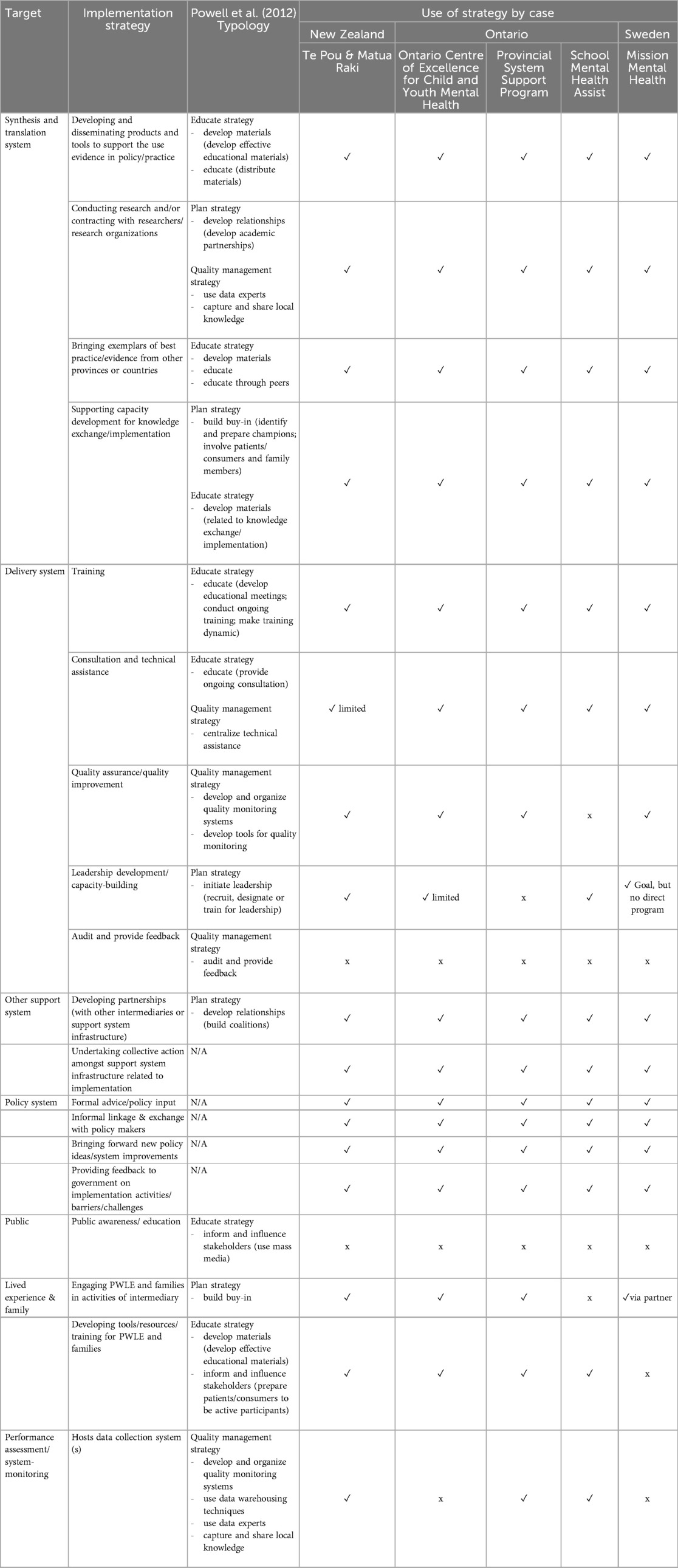

How are intermediaries structured and what strategies do they use to support the implementation of policy directions?

The structure and organizational characteristics of the intermediaries are summarized in Table 4. Generally, there is a great deal of variation in the structures and organizational characteristics of the intermediaries in our cases, with differences across most of the domains. Key differences include: the settings in which intermediaries are located (e.g., NGO, service delivery organization or peak organization), the age-related focus of the intermediary (e.g., children & youth, adult, full age continuum), the mandate and how far it extends beyond mental health (e.g., addictions, problem gambling, disability), the primary target audience of the intermediary (e.g., hospital, community, schools or cross-sectoral) and the service model (e.g., centralized or distributed). Each intermediary also has very different stated areas of investment and often focused on quite different EIPPs. They also varied around how closely they drew upon implementation or knowledge exchange models, theories or frameworks to guide their work.

In terms of similarities, three of the five intermediaries were around the same size (40–50 people), although PSSP was much larger (150 people) and SMH ASSIST was much smaller (13 core team members). All of the intermediaries also identified their respective government ministry as their primary funding source. On the whole, intermediaries differed more than they were similar with respect to their descriptive characteristics and this lack of commonality contributes to intermediaries continuing to be a “fuzzy” construct.

Interestingly, there was a high level of consistency in the strategies employed by the intermediaries, despite the large variation in intermediary structure and organizational characteristics stated above (Table 5). We did, however, observe a qualitative difference in where the emphasis of the activities was placed across implementation strategies. For example, Te Pou placed a relatively high emphasis on training compared to other activities. The OCoECYMH had a strong emphasis on lived experience and family-targeted activities. The PSSP had the most well-developed link to the synthesis and translation system through EENet and the number of researchers on staff. School Mental Health ASSIST had a strong emphasis on leadership development and capacity-building for mental health within schools and at the school board level. Finally, Mission Mental Health placed a great deal of emphasis on consultation and technical assistance, although not directed toward a particular EIPP, instead, responding to needs identified by the local authorities and regions. Te Pou also had the most well-developed information management strategy, by having national responsibility for managing two data collection systems on behalf of the Ministry of Health. They were followed closely by PSSP, that hosts an information management system for the addictions sector and has been expanding its functionality to support other EIPPs.

Despite these differences in emphasis, it is remarkable that there is so much similarity in terms of the implementation strategies employed by the intermediaries given the variation in the mandates and other structural and organizational features. It is also notable that none of the intermediaries used strategies that directly targeted the public (i.e., public awareness and education) or used audit and feedback as a Delivery system strategy. This emerged as the principal policy puzzle that needed to be explained. Specifically, why do these policy intermediaries consistently choose not to engage in these two implementation strategies?

What explains the lack of use of particular implementation strategies?

Our analysis indicates that there are five reasons why the implementation strategies targeting the public and audit and feedback are not employed by the policy intermediaries: (1) their need to build and maintain healthy relationships with policy actors (public strategies); (2) their need to build and maintain healthy relationships with service delivery system actors (audit & feedback strategy); (3) role differentiation with other system actors (public strategies); (4) lack of “fit” with the role of policy intermediaries (public and audit & feedback strategies); and (5) resource limitations that preclude intensive distributed (program-level) work (audit & feedback strategy).

The first three of these reasons are aspects of Interests using the 3I + E framework. In particular, the role of intermediaries necessarily means they must develop and manage effective relationships with other system actors and as such, they must be highly sensitized to actions that may have a compromising effect on these relationships. The power held by other system actors, and in particular, policy actors in government and service delivery system actors, is exerted indirectly on the intermediaries, what Lukes (52) calls the second dimension of power, causing them to anticipate what strategies would or would not be considered acceptable to those in power and to avoid strategies that could be damaging to these relationships.

For government and policy actors, publicly targeted strategies can sometimes be viewed as supporting advocacy, and advocacy in turn can be perceived by government actors as directly pressuring the government to make changes. Because policy intermediaries often depend on government in multiple ways (e.g., as a funding source, as an implementation partner, as a target of their activities, etc), they prefer to remain as neutral as possible, being perceived as an “honest broker” or a vehicle that enables implementation, rather than specifying what should be implemented. Thus, while the policy actors have not specifically limited the implementation activities of the intermediaries, these intermediaries have shaped their activities to avoid those public-facing strategies that could compromise their relationships with policy actors.

The “honest broker” framing extends to the relationships intermediaries must cultivate with service delivery actors. In order to facilitate implementation, intermediaries must become a trusted source of implementation support for organizations, programs and individual professionals who deliver mental health services to citizens. To build this trust, they prefer implementation strategies that are perceived as facilitative rather than those that may be perceived as more of a performance monitoring or a “watchdog” function. Audit and feedback, when used at the clinical level or at a systems level (e.g., public reporting) can be perceived as falling into the performance-monitoring category and thus, is not a preferred strategy of these intermediaries. Interestingly, some of these intermediaries still play a role in other performance monitoring strategies, by collecting data on behalf of the service delivery system. However, even when they are responsible for this strategy, their approach is often focused on enabling the service delivery sector to use its own data for improvement, or to provide policy makers with additional context for appropriate interpretation of the data and tend not to engage directly in public reporting.

The lack of “fit” of both public strategies and audit and feedback, falls under the Ideas element of the 3I + E framework. This relates to the normative assumptions held by intermediaries and their stakeholders about what policy-focused intermediaries “should” be doing and where there are seen as adding value (and conversely, where they aren't). Finally, past policies (including deinstitutionalization and decisions to offer mental health services across a continuously expanding range of service environments) makes the institutional landscape of mental health services in all three cases large in number and complex for implementation efforts at scale. All of the intermediaries face capacity constraints related to time and money. The strategy of audit and feedback can be cost and time intensive when applied at the individual program level and the intermediaries in our study did not feel they could accomplish this strategy effectively with their existing resources and scope of activity.

Discussion

Our study sheds further light on policy intermediaries supporting the implementation of EIPPs across mental health systems. These findings help to advance our understanding of the factors that lead to the development of intermediaries in terms of the problems (e.g., negative events involving people with mental illness), policies (e.g., feedback on effectiveness of existing policies) and political events (e.g., changes in government) that are salient in each case. It also presents an in-depth description of the similarities and differences in intermediary structure, organization and use of implementation strategies (e.g., the wide range of structures and organizational mandates contrasting with the striking similarities in terms of implementation strategies employed). Finally, our study provides five reasons why these intermediaries do not use audit and feedback or strategies targeting the public in their work, drawing from explanatory frameworks.

Beyond the contribution of further understanding of intermediaries and their role in facilitating implementation, this study contributes to the literature in two ways. First, our study answers the call made by Nilsen (53) and others to integrate the field of policy implementation with the field of implementation science. We did this by drawing on established theories from political science and through our focus on policy intermediaries. While we found that using these theories was not always a perfect “fit” with questions that relate to the implementation phase of the policy cycle, they were useful in generating unique insights that would not be available from implementation science. Second, we have noted that the vast majority of the literature on intermediaries, and those focusing on mental health and addictions in particular, come from the USA, which has health and social system arrangements that are fairly unique in the world. Our study expands the focus to policy intermediaries in three other countries that each have their own unique health and social system arrangements.

The pre-existing relationship that one author (HB) had with the intermediaries and other system leaders was both a source of strength in this study and a potential limitation. First, these relationships allowed for an IKT approach to the research and likely contributed to the strong response and participation in all three cases. However, her familiarity with the individuals, and her previous role in Ontario and internationally may have influenced how stakeholders responded in the interviews. For example, there were several instances when participants referenced previous conversations or knowledge that HB had and she was sometimes referenced as an influential actor in the development of the intermediaries. Conversely, this familiarity and being established as credible and knowledgeable, may have also meant that participants were more honest, or were likely to delve into issues with greater detail than with an unknown interviewer.

We faced two key challenges with our research. The first relates to the fact that there were no fluent Swedish speakers on the research team. We expect this could have affected the choice of words and phrases participants used in the interviews as well as limiting our ability to use triangulation of sources because many documents were not available in English. The second relates to conducting research in three constantly evolving systems. Since the data collection period, the research team has already noted some shifts in the intermediaries and their contexts making it difficult to be both precise and “current” in our analysis. The ability to adapt and change is likely an important trait for intermediaries and can offset the inherent instability that has been identified as problematic in existing literature (29) but presents a moving target for researchers.

Our study focused on a small number of intermediaries that best fit our definition, yet it was abundantly clear that the infrastructure needed for implementation efforts at a systems level is much more comprehensive. Many more organizations and programs were engaged in mental health policy implementation efforts in these jurisdictions. Some examples include the health quality bodies in New Zealand and Canada and the public health agency in Sweden. Future studies could examine the full complement of infrastructure and how different systems differentiate the implementation strategies among actors. An additional distinction that merits future exploration is the main funding sources and placement of intermediaries across settings (such as government, public sector and private sector), specifically, whether and how the proximity to legislative and regulatory restrictions affects intermediary functions.

Future studies could also use these findings as a foundation from which to build a quantitative study examining a larger number of intermediaries divided among the three sub-types (KT, practice and policy intermediaries) and explore whether and how the use of implementation strategies varies according to sub-type or which strategies are most closely tied to intended outcomes. For example, do policy intermediaries collectively rely on a different subset of implementation strategies than those focussed on implementation in practice settings? Furthermore, the role division and functions of individual team members within an intermediary organization requires further study. Working in a team environment may offset some of the challenges individuals face such as role conflict and ambiguity (29), but role distinction and specialization likely becomes more important (23). How can these roles be optimized in intermediary team settings?

Conclusions

Policy makers and other actors seeking to implement EIPPs must consider the capacity needed to do it effectively. Our study identifies how intermediaries can be developed and harnessed to support implementation and offers a number of transferrable lessons to those in other jurisdictions. When looking to build implementation infrastructure, policy makers and implementers should make explicit choices in terms of design, with appropriate consideration of the political system context and the health and social system context. They must also pay careful attention to the role of other actors in the system to ensure the intermediary(ies) add value and are optimized to work with those actors effectively. Finally, they should make active decisions about the implementation strategies they intend to employ and monitor their use and effectiveness. To date, much of the focus in implementation science has been at the intervention level, or on the implementation strategies and organizational contexts in which implementation occurs. We forward that it is equally important to consider the vehicles through which these strategies are delivered at scale in systems. This examination of policy intermediaries in mental health systems contributes to this gap in knowledge and increases our understanding of the role intermediaries play in implementation.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data were derived from qualitative interviews. Individual transcripts may be identifiable when viewed in whole. Requests to access the datasets should be directed toYnVsbG9jaGxAbWNtYXN0ZXIuY2E=.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval for this study was granted by McMaster University through the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board and informed consent was sought and provided by all participants.

Author contributions

HB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JL: Writing – review & editing. GM: Writing – review & editing. MW: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors disclose receipt of the following financial support for their research, authorship and/or publication of this article: Trudeau Foundation Doctoral Scholarship.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support of Andrea Dafel in preparing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

EIPPs, evidence-informed policies and practices; IIMHL, International Initiative for Mental Health Leadership; IKT, integrated knowledge translation; ISF, interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation; OCoECYMH, Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health; MOHLTC, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; PSSP, Provincial System Support Program; SMH ASSIST, School Mental Health ASSIST; SALAR, Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions; MCYS, Ministry of Children & Youth Services; CAMH, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

References

1. Bruns EJ, Kerns SE, Pullmann MD, Hensley SW, Lutterman T, Hoagwood KE. Research, data, and evidence-based treatment use in state behavioral health systems, 2001–2012. Psychiatr Serv. (2016) 67(5):496–503. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500014

2. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. (2013) 382(9904):1575–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6

3. World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2017 (Report No.: Licence: CC bY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO). Geneva: World Health Organization (2018).

4. Emshoff JG. Researchers, practitioners, and funders: using the framework to get US on the same page. Am J Community Psychol. (2008) 41(3-4):393–403. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9168-x

5. Franks RP. Role of the intermediary organization in promoting and disseminating mental health best practices for children and youth - the Connecticut center for effective practice. Emo Behav Dis Youth (Fall). (2010) 10(4):87–93.

6. Thigpen S, Puddy RW, Singer HH, Hall DM. Moving knowledge into action: developing the rapid synthesis and translation process within the interactive systems framework. Am J Community Psychol. (2012) 50(3-4):285–94. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9537-3

7. Brodowski ML, Counts JM, Gillam RJ, Baker L, Collins VS, Winkle E, et al. Translating evidence-based policy to practice: a multilevel partnership using the interactive systems framework. Fam Soc: J Contemp Soc Serv. (2013) 94(3):141–9. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.4303

8. Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence-based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care. (1998) 7:149–58.10185141

9. Harvey G, Kitson A. PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implement Sci. (2016) 11:33. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0398-2

10. Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Quarterly. (2004) 82(4):581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x

11. Anthony EK, Austin MJ. The role of an intermediary organization in promoting research in schools of social work: the case of the bay area social services consortium. Soc Work Res. (2008) 32(4):287–93. doi: 10.1093/swr/32.4.287

12. Cooper A. Knowledge Mobilization Intermediaries in Education: A Cross-Case Analysis of 44 Canadian Organizations. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto (2012).

13. Scott J, Jabbar H. The hub and the spokes: foundations, intermediary organizations, incentivist reforms, and the politics of research evidence. Educ Pol. (2014) 28(2):233–57. doi: 10.1177/0895904813515327

14. Hitchman KG. Organizational structure and functions within intermediary organizations: a comparative analysis. Waterloo, ON: Canadian Water Network (2010).

15. Proctor E, Hooley C, Morse A, McCrary S, Kim H, Kohl PL. Intermediary/purveyor organizations for evidence-based interventions in the US child mental health: characteristics and implementation strategies. Implement Sci. (2019) 14(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0845-3

16. Salyers MP, McKasson M, Bond GR, McGrew JH, Rollins AL, Boyle C. The role of technical assistance centers in implementing evidence-based practices: lessons learned. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. (2007) 10(2):85–101. doi: 10.1080/15487760701345968

17. Kramer DM, Wells RP, Bigelow PL, Carlan NA, Cole DC, Hepburn CG. Dancing the two-step: collaborating with intermediary organizations as research partners to help implement workplace health and safety interventions. Work. (2010) 36(3):321–32. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2010-1033

18. Suvinen N, Konttinen J, Nieminen M. How necessary are intermediary organizations in the commercialization of research? European Planning Studies. (2010) 18(9):1365–89. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2010.492584

19. Smits P, Denis JL, Couturier Y, Touati N, Roy D, Boucher G, et al. Implementing public policy in a non-directive manner: capacities from an intermediary organization. Can J Public Health. (2020) 111:72–9. doi: 10.17269/s41997-019-00257-6

20. Franks RP, Bory CT. Strategies for developing intermediary organizations: considerations for practice. Fam Soc. (2017) 98(1):27–34. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.2017.6

21. Davis L, Wong L, Bromley E. Brokering system change: a logic model of an intermediary-purveyor organization for behavioral health care. Psychiatr Serv. (2022) 73(8):933–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100425

22. Wandersman A, Scheier LM. Strengthening the science and practice of implementation support: evaluating the effectiveness of training and technical assistance centers. Eval Health Prof. (2024) 47(2):143–53. doi: 10.1177/01632787241248768

23. Ward V, House A, Hamer S. Knowledge brokering: the missing link in the evidence to action chain? Evid Policy. (2009) 5(3):267–79. 10.1332/174426409×46381121258626

24. Manyazewal T, Woldeamanuel Y, Oppenheim C, Hailu A, Giday M, Medhin G, et al. Conceptualizing centers of excellence: a global evidence. medRxiv. (2021) 12(2):1–9. doi: 10.1101/2021.03.20.2021-03

25. Higgins MC, Weiner J, Young L. Implementation teams: a new lever for organizational change. J Organ Behav. (2012) 33(3):366–88. doi: 10.1002/job.1773

26. DuBow W, Hug S, Serafini B, Litzler E. Expanding our understanding of backbone organizations in collective impact initiatives. Community Dev. (2018) 49(3):256–73. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2018.1458744

27. Franks RP, Bory CT. Who supports the successful implementation and sustainability of evidence-based practices? Defining and understanding the roles of intermediary and purveyor organizations. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. (2015) 2015(149):41–56. doi: 10.1002/cad.20112

28. Wandersman A, Chien VH, Katz J. Toward an evidence-based system for innovation support for implementing innovations with quality: tools, training, technical assistance, and quality assurance/quality improvement. Am J Community Psychol. (2012) 50(3-4):445–59. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9509-7

29. Chew S, Armstrong N, Martin G. Institutionalising knowledge brokering as a sustainable knowledge translation solution in healthcare: how can it work in practice? Evid Policy. (2013) 9(3):335–51. doi: 10.1332/174426413X662734

30. Meagher L, Lyall C. The invisible made visible: using impact evaluations to illuminate and inform the role of knowledge intermediaries. Ev Pol: J Res Deb Prac. (2013) 9:409–18. doi: 10.1332/174426422X16419160905358

31. Oosthuizen C, Louw J. Developing program theory for purveyor programs. Implement Sci. (2013) 8(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-23

32. Lopez ME, Kreider H, Coffman J. Intermediary organizations as capacity builders in family educational involvement. School Community J. (2005) 40(1):78–105.

33. Honig MI. The new middle management: intermediary organizations in education policy implementation. Educ Eval Policy Anal. (2004) 26(1):65–87. doi: 10.3102/01623737026001065

34. Shea J. Taking nonprofit intermediaries seriously: a middle-range theory for implementation research. Public Adm Rev. (2011) 71(1):57–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02306.x

35. Gagliardi AR, Berta W, Kothari A, Boyko J, Urquhart R. Integrated knowledge translation (IKT) in health care: a scoping review. Implement Sci. (2016) 11(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0399-1

37. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage (2011). p. 97–128.

38. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. (2000) 23(4):334–40. doi: 10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4%3C334::AID-NUR9%3E3.0.CO;2-G

39. Collier D. The comparative method. In: Finifter A, editor. Political Science: The State of the Discipline II. Washington DC: American Political Science Association (1993). p. 105–19.

40. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. (2005) 15(9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

41. Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies (Updated 2nd ed.). New York: HarperCollins College Publishers (1995).

42. Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, Noonan R, Lubell K, Stillman L, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: the interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. Am J Community Psychol. (2008) 41(3-4):171–81. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9174-z

43. Powell BJ, Proctor EK, Glass JE. A systematic review of strategies for implementing empirically supported mental health interventions. Res Soc Work Prac. (2013) 24(2):192–212.

44. Lavis JN, Ross SE, Hurley JE, Hohenadel JM, Stoddart GL, Woodward CA, et al. Examining the role of health services research in public policymaking. Milbank Q. (2002) 80:125–54. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00005

45. Lavis JN. Studying health-care reforms. In: Lazar H, Forest PG, Church J, Lavis JN, editors. Paradigm Freeze: Why it is so Hard to Reform Health Care in Canada. Kingston: McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP (2013). p. 21–35.

46. Brunton W. The origins of deinstitutionalisation in New Zealand. Health History. (2003) 5(2):75–103. doi: 10.2307/40111454

47. Williams MW, Haarhoff B, Vertongen R. Mental health in aotearoa New Zealand: rising to the challenge of the fourth wave? NZ J Psychol. (2017) 46(2):16–22.

48. Sealy P, Whitehead PC. Forty years of deinstitutionalization of psychiatric services in Canada: an empirical assessment. Can J Psychiatry. (2004) 49(4):249–57. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900405

49. Hartford K, Schrecker T, Wiktorowicz M, Hoch JS, Sharp C. Four decades of mental health policy in Ontario, Canada. Adm Policy Ment Health. (2003) 31(1):65–73. doi: 10.1023/A:1026000423918

50. Mulvale G, Abelson J, Goering P. Mental health service delivery in Ontario, Canada: how do policy legacies shape prospects for reform? Health Econ Policy Law. (2007) 2(Pt 4):363–89. doi: 10.1017/S1744133107004318

51. Silfverhielm H, Kamis-Gould E. The Swedish mental health system: past, present, and future. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2000) 23(3-4):293–307. doi: 10.1016/S0160-2527(00)00039-X

53. Nilsen P, Stahl C, Roback K, Cairney P. Never the twain shall meet? A comparison of implementation science and policy implementation research. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:63. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-63

APPENDIX

Interview guide for case study interviews

Ethical considerations

A description of the study will have been presented during the recruitment phase. A signed confirmation of commitment to participate will be obtained prior to engaging in the questions. Any ethical issues arising will be addressed prior to the first question and will be documented by the Interviewer.

Process

Interviews will be recorded on a digital audio device or computer, transcribed, and uploaded into a qualitative software program. Hand written notes will also be made by the interviewer into her field notebook.

✓ Denotes probes

Date:

Time:

Place:

Interviewer:

Interviewee:

Position of Interviewee:

Questions

Do you have any questions for me before proceeding to the interview?

Before we start, I wanted to mention that we will be using the term “mental health” to refer to fields of “mental illness”, “addictions”, “behavioural health” and “health promotion and prevention of mental illnesses and/or addictions” inclusively. It also refers to the health of individuals across the lifespan, not just at particular life stages. Feel free to point out particular or unique features of any of these depending on how your system is arranged, if you feel they are relevant.

A—current mental health policy priorities

• Can you tell me a little bit about the current policy priorities in [your jurisdiction] that are being implemented? (top 2–4)

✓ When were they identified as priorities?

✓ How is the implementation of these priorities governed?

✓ How are these priorities financed & funded (if at all)?

✓ How are they delivered?

▪ Consumer-targeted

▪ Provider-targeted

▪ Organization-targeted

✓ What system challenges are the policy priorities trying to address?

✓ What outcomes are they meant to achieve?

✓ What organizations/programs/people are responsible for implementing them?

B—structures supporting implementation of mental health priorities (support system & synthesis & translation system)

• I understand from the previous phase of my study that [organization or program] has a role in supporting the implementation of some of the mental health strategic directions/policies/ targets. Can you tell me a little more about them?

✓ Who gave them this responsibility?

✓ Can you describe [organization or program]’s role and how it functions?

✓ What is its size? (in terms of people and funding)

• Who do they provide these activities to? (recipients)

• Do organizations/programs/people from communities voluntarily come to [organization/program] to access implementation supports or does [organization/program] proactively approach the organizations/programs/people in the community? (push vs. pull)

• How are they perceived by other organizations/programs/people in your system?

• Are there other organizations or programs that also play a role supporting the implementation of mental health priorities?

✓ Do they differ from [organization or program]? How?

○ Generating guidelines

○ Generating research & synthesizing it (not just primary research)

○ Data systems

○ Continuing education

C—delivery methods and approaches to change being utilized

• What types of activities does [organization/program] engage in? (list from EBSIS, HSE, Franks & Bory & phase 1 of this study)

✓ General capacity building

✓ Knowledge translation/exchange/mobilization

✓ Specific implementation supports (e.g., for a particular Evidence Based Practice, also called technical assistance)

✓ Education and training

✓ Coaching

✓ Research & Evaluation

✓ Quality improvement

✓ Convening people (in-person/virtual)

✓ Consultation

✓ Policy & Systems Building

✓ Best practice model development

✓ Public awareness and education

✓ Opinion leaders

✓ Audit and feedback

✓ Train-the-trainer

✓ Other

• Are the activities targeted at the organizational level, the provider level or the consumer/patient level?

• What is the frequency with which they provide these activities?

• Are the people who deliver these activities from [organization/program] located in the communities in which they are delivered? If not, where are they from? (central vs. regional)

• Are there any particular over-arching methods or approaches the [organization or program] utilizes?

✓ Implementation science (IS) and the specific IS model

✓ Getting-To-Outcomes

✓ Quality improvement methods such as LEAN or the IHI model

✓ Any other specific methods or approaches that you haven’t already mentioned?

D—value, challenges & outcomes

• Do you have a sense of what the strengths of this structure and methods might be?

✓ Institutions (e.g., government structures, policy legacies, networks), interests (e.g., citizen groups, professional associations, etc), ideas (e.g., values, research, etc)

• Do you feel [organization or program] is valued by the system?

○ Who in the system values them?

○ Why?

• What are some of the barriers or challenges that are faced in this work?

✓ Institutions (e.g., government structures, policy legacies, networks), interests (e.g., citizen groups, professional associations, etc), ideas (e.g., values, research, etc)

• Is [organization/program] able to help achieve the identified policy goals?

• Are there evaluation or outcome data available?

Prompt for documents, presentations or other items that might address any of the topics discussed

Keywords: evidence-informed policy, implementation science, mental health, addiction, intermediary, case study, technical assistance, policy implementation

Citation: Bullock HL, Lavis JN, Mulvale G and Wilson MG (2024) An examination of mental health policy implementation efforts and the intermediaries that support them in New Zealand, Canada and Sweden: a comparative case study. Front. Health Serv. 4:1371207. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2024.1371207

Received: 16 January 2024; Accepted: 11 July 2024;

Published: 21 August 2024.

Edited by:

Reza Yousefi Nooraie, University of Rochester, United StatesReviewed by:

Molly McNulty, University of Rochester, United StatesPorooshat Dadgostar, University of Rochester, United States

Copyright: © 2024 Bullock, Lavis, Mulvale and Wilson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Heather L. Bullock, aGJ1bGxvY2tAd2F5cG9pbnRjZW50cmUuY2E=

Heather L. Bullock

Heather L. Bullock John N. Lavis1

John N. Lavis1